Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Introduction

You’ve been assigned a literary analysis paper—what does that even mean? Is it like a book report that you used to write in high school? Well, not really.

A literary analysis essay asks you to make an original argument about a poem, play, or work of fiction and support that argument with research and evidence from your careful reading of the text.

It can take many forms, such as a close reading of a text, critiquing the text through a particular literary theory, comparing one text to another, or criticizing another critic’s interpretation of the text. While there are many ways to structure a literary essay, writing this kind of essay follows generally follows a similar process for everyone

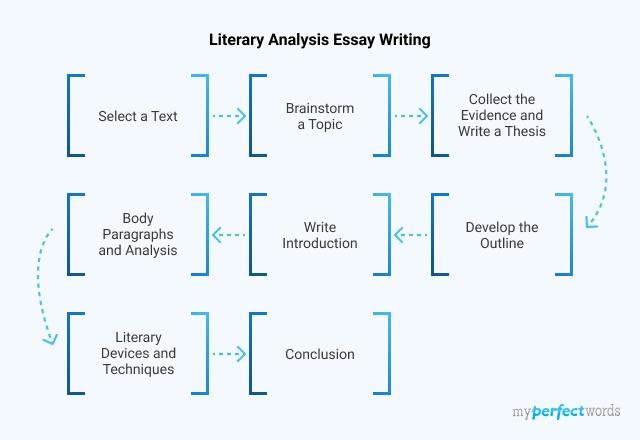

Crafting a good literary analysis essay begins with good close reading of the text, in which you have kept notes and observations as you read. This will help you with the first step, which is selecting a topic to write about—what jumped out as you read, what are you genuinely interested in? The next step is to focus your topic, developing it into an argument—why is this subject or observation important? Why should your reader care about it as much as you do? The third step is to gather evidence to support your argument, for literary analysis, support comes in the form of evidence from the text and from your research on what other literary critics have said about your topic. Only after you have performed these steps, are you ready to begin actually writing your essay.

Writing a Literary Analysis Essay

How to create a topic and conduct research:.

Writing an Analysis of a Poem, Story, or Play

If you are taking a literature course, it is important that you know how to write an analysis—sometimes called an interpretation or a literary analysis or a critical reading or a critical analysis—of a story, a poem, and a play. Your instructor will probably assign such an analysis as part of the course assessment. On your mid-term or final exam, you might have to write an analysis of one or more of the poems and/or stories on your reading list. Or the dreaded “sight poem or story” might appear on an exam, a work that is not on the reading list, that you have not read before, but one your instructor includes on the exam to examine your ability to apply the active reading skills you have learned in class to produce, independently, an effective literary analysis.You might be asked to write instead or, or in addition to an analysis of a literary work, a more sophisticated essay in which you compare and contrast the protagonists of two stories, or the use of form and metaphor in two poems, or the tragic heroes in two plays.

You might learn some literary theory in your course and be asked to apply theory—feminist, Marxist, reader-response, psychoanalytic, new historicist, for example—to one or more of the works on your reading list. But the seminal assignment in a literature course is the analysis of the single poem, story, novel, or play, and, even if you do not have to complete this assignment specifically, it will form the basis of most of the other writing assignments you will be required to undertake in your literature class. There are several ways of structuring a literary analysis, and your instructor might issue specific instructions on how he or she wants this assignment done. The method presented here might not be identical to the one your instructor wants you to follow, but it will be easy enough to modify, if your instructor expects something a bit different, and it is a good default method, if your instructor does not issue more specific guidelines.You want to begin your analysis with a paragraph that provides the context of the work you are analyzing and a brief account of what you believe to be the poem or story or play’s main theme. At a minimum, your account of the work’s context will include the name of the author, the title of the work, its genre, and the date and place of publication. If there is an important biographical or historical context to the work, you should include that, as well.Try to express the work’s theme in one or two sentences. Theme, you will recall, is that insight into human experience the author offers to readers, usually revealed as the content, the drama, the plot of the poem, story, or play unfolds and the characters interact. Assessing theme can be a complex task. Authors usually show the theme; they don’t tell it. They rarely say, at the end of the story, words to this effect: “and the moral of my story is…” They tell their story, develop their characters, provide some kind of conflict—and from all of this theme emerges. Because identifying theme can be challenging and subjective, it is often a good idea to work through the rest of the analysis, then return to the beginning and assess theme in light of your analysis of the work’s other literary elements.Here is a good example of an introductory paragraph from Ben’s analysis of William Butler Yeats’ poem, “Among School Children.”

“Among School Children” was published in Yeats’ 1928 collection of poems The Tower. It was inspired by a visit Yeats made in 1926 to school in Waterford, an official visit in his capacity as a senator of the Irish Free State. In the course of the tour, Yeats reflects upon his own youth and the experiences that shaped the “sixty-year old, smiling public man” (line 8) he has become. Through his reflection, the theme of the poem emerges: a life has meaning when connections among apparently disparate experiences are forged into a unified whole.

In the body of your literature analysis, you want to guide your readers through a tour of the poem, story, or play, pausing along the way to comment on, analyze, interpret, and explain key incidents, descriptions, dialogue, symbols, the writer’s use of figurative language—any of the elements of literature that are relevant to a sound analysis of this particular work. Your main goal is to explain how the elements of literature work to elucidate, augment, and develop the theme. The elements of literature are common across genres: a story, a narrative poem, and a play all have a plot and characters. But certain genres privilege certain literary elements. In a poem, for example, form, imagery and metaphor might be especially important; in a story, setting and point-of-view might be more important than they are in a poem; in a play, dialogue, stage directions, lighting serve functions rarely relevant in the analysis of a story or poem.

The length of the body of an analysis of a literary work will usually depend upon the length of work being analyzed—the longer the work, the longer the analysis—though your instructor will likely establish a word limit for this assignment. Make certain that you do not simply paraphrase the plot of the story or play or the content of the poem. This is a common weakness in student literary analyses, especially when the analysis is of a poem or a play.

Here is a good example of two body paragraphs from Amelia’s analysis of “Araby” by James Joyce.

Within the story’s first few paragraphs occur several religious references which will accumulate as the story progresses. The narrator is a student at the Christian Brothers’ School; the former tenant of his house was a priest; he left behind books called The Abbot and The Devout Communicant. Near the end of the story’s second paragraph the narrator describes a “central apple tree” in the garden, under which is “the late tenant’s rusty bicycle pump.” We may begin to suspect the tree symbolizes the apple tree in the Garden of Eden and the bicycle pump, the snake which corrupted Eve, a stretch, perhaps, until Joyce’s fall-of-innocence theme becomes more apparent.

The narrator must continue to help his aunt with her errands, but, even when he is so occupied, his mind is on Mangan’s sister, as he tries to sort out his feelings for her. Here Joyce provides vivid insight into the mind of an adolescent boy at once elated and bewildered by his first crush. He wants to tell her of his “confused adoration,” but he does not know if he will ever have the chance. Joyce’s description of the pleasant tension consuming the narrator is conveyed in a striking simile, which continues to develop the narrator’s character, while echoing the religious imagery, so important to the story’s theme: “But my body was like a harp, and her words and gestures were like fingers, running along the wires.”

The concluding paragraph of your analysis should realize two goals. First, it should present your own opinion on the quality of the poem or story or play about which you have been writing. And, second, it should comment on the current relevance of the work. You should certainly comment on the enduring social relevance of the work you are explicating. You may comment, though you should never be obliged to do so, on the personal relevance of the work. Here is the concluding paragraph from Dao-Ming’s analysis of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest.

First performed in 1895, The Importance of Being Earnest has been made into a film, as recently as 2002 and is regularly revived by professional and amateur theatre companies. It endures not only because of the comic brilliance of its characters and their dialogue, but also because its satire still resonates with contemporary audiences. I am still amazed that I see in my own Asian mother a shadow of Lady Bracknell, with her obsession with finding for her daughter a husband who will maintain, if not, ideally, increase the family’s social status. We might like to think we are more liberated and socially sophisticated than our Victorian ancestors, but the starlets and eligible bachelors who star in current reality television programs illustrate the extent to which superficial concerns still influence decisions about love and even marriage. Even now, we can turn to Oscar Wilde to help us understand and laugh at those who are earnest in name only.

Dao-Ming’s conclusion is brief, but she does manage to praise the play, reaffirm its main theme, and explain its enduring appeal. And note how her last sentence cleverly establishes that sense of closure that is also a feature of an effective analysis.

You may, of course, modify the template that is presented here. Your instructor might favour a somewhat different approach to literary analysis. Its essence, though, will be your understanding and interpretation of the theme of the poem, story, or play and the skill with which the author shapes the elements of literature—plot, character, form, diction, setting, point of view—to support the theme.

Academic Writing Tips : How to Write a Literary Analysis Paper. Authored by: eHow. Located at: https://youtu.be/8adKfLwIrVk. License: All Rights Reserved. License Terms: Standard YouTube license

BC Open Textbooks: English Literature Victorians and Moderns: https://opentextbc.ca/englishliterature/back-matter/appendix-5-writing-an-analysis-of-a-poem-story-and-play/

Literary Analysis

The challenges of writing about english literature.

Writing begins with the act of reading . While this statement is true for most college papers, strong English papers tend to be the product of highly attentive reading (and rereading). When your instructors ask you to do a “close reading,” they are asking you to read not only for content, but also for structures and patterns. When you perform a close reading, then, you observe how form and content interact. In some cases, form reinforces content: for example, in John Donne’s Holy Sonnet 14, where the speaker invites God’s “force” “to break, blow, burn and make [him] new.” Here, the stressed monosyllables of the verbs “break,” “blow” and “burn” evoke aurally the force that the speaker invites from God. In other cases, form raises questions about content: for example, a repeated denial of guilt will likely raise questions about the speaker’s professed innocence. When you close read, take an inductive approach. Start by observing particular details in the text, such as a repeated image or word, an unexpected development, or even a contradiction. Often, a detail–such as a repeated image–can help you to identify a question about the text that warrants further examination. So annotate details that strike you as you read. Some of those details will eventually help you to work towards a thesis. And don’t worry if a detail seems trivial. If you can make a case about how an apparently trivial detail reveals something significant about the text, then your paper will have a thought-provoking thesis to argue.

Common Types of English Papers Many assignments will ask you to analyze a single text. Others, however, will ask you to read two or more texts in relation to each other, or to consider a text in light of claims made by other scholars and critics. For most assignments, close reading will be central to your paper. While some assignment guidelines will suggest topics and spell out expectations in detail, others will offer little more than a page limit. Approaching the writing process in the absence of assigned topics can be daunting, but remember that you have resources: in section, you will probably have encountered some examples of close reading; in lecture, you will have encountered some of the course’s central questions and claims. The paper is a chance for you to extend a claim offered in lecture, or to analyze a passage neglected in lecture. In either case, your analysis should do more than recapitulate claims aired in lecture and section. Because different instructors have different goals for an assignment, you should always ask your professor or TF if you have questions. These general guidelines should apply in most cases:

- A close reading of a single text: Depending on the length of the text, you will need to be more or less selective about what you choose to consider. In the case of a sonnet, you will probably have enough room to analyze the text more thoroughly than you would in the case of a novel, for example, though even here you will probably not analyze every single detail. By contrast, in the case of a novel, you might analyze a repeated scene, image, or object (for example, scenes of train travel, images of decay, or objects such as or typewriters). Alternately, you might analyze a perplexing scene (such as a novel’s ending, albeit probably in relation to an earlier moment in the novel). But even when analyzing shorter works, you will need to be selective. Although you might notice numerous interesting details as you read, not all of those details will help you to organize a focused argument about the text. For example, if you are focusing on depictions of sensory experience in Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale,” you probably do not need to analyze the image of a homeless Ruth in stanza 7, unless this image helps you to develop your case about sensory experience in the poem.

- A theoretically-informed close reading. In some courses, you will be asked to analyze a poem, a play, or a novel by using a critical theory (psychoanalytic, postcolonial, gender, etc). For example, you might use Kristeva’s theory of abjection to analyze mother-daughter relations in Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved. Critical theories provide focus for your analysis; if “abjection” is the guiding concept for your paper, you should focus on the scenes in the novel that are most relevant to the concept.

- A historically-informed close reading. In courses with a historicist orientation, you might use less self-consciously literary documents, such as newspapers or devotional manuals, to develop your analysis of a literary work. For example, to analyze how Robinson Crusoe makes sense of his island experiences, you might use Puritan tracts that narrate events in terms of how God organizes them. The tracts could help you to show not only how Robinson Crusoe draws on Puritan narrative conventions, but also—more significantly—how the novel revises those conventions.

- A comparison of two texts When analyzing two texts, you might look for unexpected contrasts between apparently similar texts, or unexpected similarities between apparently dissimilar texts, or for how one text revises or transforms the other. Keep in mind that not all of the similarities, differences, and transformations you identify will be relevant to an argument about the relationship between the two texts. As you work towards a thesis, you will need to decide which of those similarities, differences, or transformations to focus on. Moreover, unless instructed otherwise, you do not need to allot equal space to each text (unless this 50/50 allocation serves your thesis well, of course). Often you will find that one text helps to develop your analysis of another text. For example, you might analyze the transformation of Ariel’s song from The Tempest in T. S. Eliot’s poem, The Waste Land. Insofar as this analysis is interested in the afterlife of Ariel’s song in a later poem, you would likely allot more space to analyzing allusions to Ariel’s song in The Waste Land (after initially establishing the song’s significance in Shakespeare’s play, of course).

- A response paper A response paper is a great opportunity to practice your close reading skills without having to develop an entire argument. In most cases, a solid approach is to select a rich passage that rewards analysis (for example, one that depicts an important scene or a recurring image) and close read it. While response papers are a flexible genre, they are not invitations for impressionistic accounts of whether you liked the work or a particular character. Instead, you might use your close reading to raise a question about the text—to open up further investigation, rather than to supply a solution.

- A research paper. In most cases, you will receive guidance from the professor on the scope of the research paper. It is likely that you will be expected to consult sources other than the assigned readings. Hollis is your best bet for book titles, and the MLA bibliography (available through e-resources) for articles. When reading articles, make sure that they have been peer reviewed; you might also ask your TF to recommend reputable journals in the field.

Harvard College Writing Program: https://writingproject.fas.harvard.edu/files/hwp/files/bg_writing_english.pdf

In the same way that we talk with our friends about the latest episode of Game of Thrones or newest Marvel movie, scholars communicate their ideas and interpretations of literature through written literary analysis essays. Literary analysis essays make us better readers of literature.

Only through careful reading and well-argued analysis can we reach new understandings and interpretations of texts that are sometimes hundreds of years old. Literary analysis brings new meaning and can shed new light on texts. Building from careful reading and selecting a topic that you are genuinely interested in, your argument supports how you read and understand a text. Using examples from the text you are discussing in the form of textual evidence further supports your reading. Well-researched literary analysis also includes information about what other scholars have written about a specific text or topic.

Literary analysis helps us to refine our ideas, question what we think we know, and often generates new knowledge about literature. Literary analysis essays allow you to discuss your own interpretation of a given text through careful examination of the choices the original author made in the text.

ENG134 – Literary Genres Copyright © by The American Women's College and Jessica Egan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Literary theory.

“Literary theory” is the body of ideas and methods we use in the practical reading of literature. By literary theory we refer not to the meaning of a work of literature but to the theories that reveal what literature can mean. Literary theory is a description of the underlying principles, one might say the tools, by which we attempt to understand literature. All literary interpretation draws on a basis in theory but can serve as a justification for very different kinds of critical activity. It is literary theory that formulates the relationship between author and work; literary theory develops the significance of race, class, and gender for literary study, both from the standpoint of the biography of the author and an analysis of their thematic presence within texts. Literary theory offers varying approaches for understanding the role of historical context in interpretation as well as the relevance of linguistic and unconscious elements of the text. Literary theorists trace the history and evolution of the different genres—narrative, dramatic, lyric—in addition to the more recent emergence of the novel and the short story, while also investigating the importance of formal elements of literary structure. Lastly, literary theory in recent years has sought to explain the degree to which the text is more the product of a culture than an individual author and in turn how those texts help to create the culture.

Table of Contents

- What Is Literary Theory?

- Traditional Literary Criticism

- Formalism and New Criticism

- Marxism and Critical Theory

- Structuralism and Poststructuralism

- New Historicism and Cultural Materialism

- Ethnic Studies and Postcolonial Criticism

- Gender Studies and Queer Theory

- Cultural Studies

- General Works on Theory

- Literary and Cultural Theory

1. What Is Literary Theory?

“Literary theory,” sometimes designated “critical theory,” or “theory,” and now undergoing a transformation into “cultural theory” within the discipline of literary studies, can be understood as the set of concepts and intellectual assumptions on which rests the work of explaining or interpreting literary texts. Literary theory refers to any principles derived from internal analysis of literary texts or from knowledge external to the text that can be applied in multiple interpretive situations. All critical practice regarding literature depends on an underlying structure of ideas in at least two ways: theory provides a rationale for what constitutes the subject matter of criticism—”the literary”—and the specific aims of critical practice—the act of interpretation itself. For example, to speak of the “unity” of Oedipus the King explicitly invokes Aristotle’s theoretical statements on poetics. To argue, as does Chinua Achebe, that Joseph Conrad’s The Heart of Darkness fails to grant full humanity to the Africans it depicts is a perspective informed by a postcolonial literary theory that presupposes a history of exploitation and racism. Critics that explain the climactic drowning of Edna Pontellier in The Awakening as a suicide generally call upon a supporting architecture of feminist and gender theory. The structure of ideas that enables criticism of a literary work may or may not be acknowledged by the critic, and the status of literary theory within the academic discipline of literary studies continues to evolve.

Literary theory and the formal practice of literary interpretation runs a parallel but less well known course with the history of philosophy and is evident in the historical record at least as far back as Plato. The Cratylus contains a Plato’s meditation on the relationship of words and the things to which they refer. Plato’s skepticism about signification, i.e., that words bear no etymological relationship to their meanings but are arbitrarily “imposed,” becomes a central concern in the twentieth century to both “Structuralism” and “Poststructuralism.” However, a persistent belief in “reference,” the notion that words and images refer to an objective reality, has provided epistemological (that is, having to do with theories of knowledge) support for theories of literary representation throughout most of Western history. Until the nineteenth century, Art, in Shakespeare’s phrase, held “a mirror up to nature” and faithfully recorded an objectively real world independent of the observer.

Modern literary theory gradually emerges in Europe during the nineteenth century. In one of the earliest developments of literary theory, German “higher criticism” subjected biblical texts to a radical historicizing that broke with traditional scriptural interpretation. “Higher,” or “source criticism,” analyzed biblical tales in light of comparable narratives from other cultures, an approach that anticipated some of the method and spirit of twentieth century theory, particularly “Structuralism” and “New Historicism.” In France, the eminent literary critic Charles Augustin Saint Beuve maintained that a work of literature could be explained entirely in terms of biography, while novelist Marcel Proust devoted his life to refuting Saint Beuve in a massive narrative in which he contended that the details of the life of the artist are utterly transformed in the work of art. (This dispute was taken up anew by the French theorist Roland Barthes in his famous declaration of the “Death of the Author.” See “Structuralism” and “Poststructuralism.”) Perhaps the greatest nineteenth century influence on literary theory came from the deep epistemological suspicion of Friedrich Nietzsche: that facts are not facts until they have been interpreted. Nietzsche’s critique of knowledge has had a profound impact on literary studies and helped usher in an era of intense literary theorizing that has yet to pass.

Attention to the etymology of the term “theory,” from the Greek “theoria,” alerts us to the partial nature of theoretical approaches to literature. “Theoria” indicates a view or perspective of the Greek stage. This is precisely what literary theory offers, though specific theories often claim to present a complete system for understanding literature. The current state of theory is such that there are many overlapping areas of influence, and older schools of theory, though no longer enjoying their previous eminence, continue to exert an influence on the whole. The once widely-held conviction (an implicit theory) that literature is a repository of all that is meaningful and ennobling in the human experience, a view championed by the Leavis School in Britain, may no longer be acknowledged by name but remains an essential justification for the current structure of American universities and liberal arts curricula. The moment of “Deconstruction” may have passed, but its emphasis on the indeterminacy of signs (that we are unable to establish exclusively what a word means when used in a given situation) and thus of texts, remains significant. Many critics may not embrace the label “feminist,” but the premise that gender is a social construct, one of theoretical feminisms distinguishing insights, is now axiomatic in a number of theoretical perspectives.

While literary theory has always implied or directly expressed a conception of the world outside the text, in the twentieth century three movements—”Marxist theory” of the Frankfurt School, “Feminism,” and “Postmodernism”—have opened the field of literary studies into a broader area of inquiry. Marxist approaches to literature require an understanding of the primary economic and social bases of culture since Marxist aesthetic theory sees the work of art as a product, directly or indirectly, of the base structure of society. Feminist thought and practice analyzes the production of literature and literary representation within the framework that includes all social and cultural formations as they pertain to the role of women in history. Postmodern thought consists of both aesthetic and epistemological strands. Postmodernism in art has included a move toward non-referential, non-linear, abstract forms; a heightened degree of self-referentiality; and the collapse of categories and conventions that had traditionally governed art. Postmodern thought has led to the serious questioning of the so-called metanarratives of history, science, philosophy, and economic and sexual reproduction. Under postmodernity, all knowledge comes to be seen as “constructed” within historical self-contained systems of understanding. Marxist, feminist, and postmodern thought have brought about the incorporation of all human discourses (that is, interlocking fields of language and knowledge) as a subject matter for analysis by the literary theorist. Using the various poststructuralist and postmodern theories that often draw on disciplines other than the literary—linguistic, anthropological, psychoanalytic, and philosophical—for their primary insights, literary theory has become an interdisciplinary body of cultural theory. Taking as its premise that human societies and knowledge consist of texts in one form or another, cultural theory (for better or worse) is now applied to the varieties of texts, ambitiously undertaking to become the preeminent model of inquiry into the human condition.

Literary theory is a site of theories: some theories, like “Queer Theory,” are “in;” other literary theories, like “Deconstruction,” are “out” but continue to exert an influence on the field. “Traditional literary criticism,” “New Criticism,” and “Structuralism” are alike in that they held to the view that the study of literature has an objective body of knowledge under its scrutiny. The other schools of literary theory, to varying degrees, embrace a postmodern view of language and reality that calls into serious question the objective referent of literary studies. The following categories are certainly not exhaustive, nor are they mutually exclusive, but they represent the major trends in literary theory of this century.

2. Traditional Literary Criticism

Academic literary criticism prior to the rise of “New Criticism” in the United States tended to practice traditional literary history: tracking influence, establishing the canon of major writers in the literary periods, and clarifying historical context and allusions within the text. Literary biography was and still is an important interpretive method in and out of the academy; versions of moral criticism, not unlike the Leavis School in Britain, and aesthetic (e.g. genre studies) criticism were also generally influential literary practices. Perhaps the key unifying feature of traditional literary criticism was the consensus within the academy as to the both the literary canon (that is, the books all educated persons should read) and the aims and purposes of literature. What literature was, and why we read literature, and what we read, were questions that subsequent movements in literary theory were to raise.

3. Formalism and New Criticism

“Formalism” is, as the name implies, an interpretive approach that emphasizes literary form and the study of literary devices within the text. The work of the Formalists had a general impact on later developments in “Structuralism” and other theories of narrative. “Formalism,” like “Structuralism,” sought to place the study of literature on a scientific basis through objective analysis of the motifs, devices, techniques, and other “functions” that comprise the literary work. The Formalists placed great importance on the literariness of texts, those qualities that distinguished the literary from other kinds of writing. Neither author nor context was essential for the Formalists; it was the narrative that spoke, the “hero-function,” for example, that had meaning. Form was the content. A plot device or narrative strategy was examined for how it functioned and compared to how it had functioned in other literary works. Of the Russian Formalist critics, Roman Jakobson and Viktor Shklovsky are probably the most well known.

The Formalist adage that the purpose of literature was “to make the stones stonier” nicely expresses their notion of literariness. “Formalism” is perhaps best known is Shklovsky’s concept of “defamiliarization.” The routine of ordinary experience, Shklovsky contended, rendered invisible the uniqueness and particularity of the objects of existence. Literary language, partly by calling attention to itself as language, estranged the reader from the familiar and made fresh the experience of daily life.

The “New Criticism,” so designated as to indicate a break with traditional methods, was a product of the American university in the 1930s and 40s. “New Criticism” stressed close reading of the text itself, much like the French pedagogical precept “explication du texte.” As a strategy of reading, “New Criticism” viewed the work of literature as an aesthetic object independent of historical context and as a unified whole that reflected the unified sensibility of the artist. T.S. Eliot, though not explicitly associated with the movement, expressed a similar critical-aesthetic philosophy in his essays on John Donne and the metaphysical poets, writers who Eliot believed experienced a complete integration of thought and feeling. New Critics like Cleanth Brooks, John Crowe Ransom, Robert Penn Warren and W.K. Wimsatt placed a similar focus on the metaphysical poets and poetry in general, a genre well suited to New Critical practice. “New Criticism” aimed at bringing a greater intellectual rigor to literary studies, confining itself to careful scrutiny of the text alone and the formal structures of paradox, ambiguity, irony, and metaphor, among others. “New Criticism” was fired by the conviction that their readings of poetry would yield a humanizing influence on readers and thus counter the alienating tendencies of modern, industrial life. “New Criticism” in this regard bears an affinity to the Southern Agrarian movement whose manifesto, I’ll Take My Stand , contained essays by two New Critics, Ransom and Warren. Perhaps the enduring legacy of “New Criticism” can be found in the college classroom, in which the verbal texture of the poem on the page remains a primary object of literary study.

4. Marxism and Critical Theory

Marxist literary theories tend to focus on the representation of class conflict as well as the reinforcement of class distinctions through the medium of literature. Marxist theorists use traditional techniques of literary analysis but subordinate aesthetic concerns to the final social and political meanings of literature. Marxist theorist often champion authors sympathetic to the working classes and authors whose work challenges economic equalities found in capitalist societies. In keeping with the totalizing spirit of Marxism, literary theories arising from the Marxist paradigm have not only sought new ways of understanding the relationship between economic production and literature, but all cultural production as well. Marxist analyses of society and history have had a profound effect on literary theory and practical criticism, most notably in the development of “New Historicism” and “Cultural Materialism.”

The Hungarian theorist Georg Lukacs contributed to an understanding of the relationship between historical materialism and literary form, in particular with realism and the historical novel. Walter Benjamin broke new ground in his work in his study of aesthetics and the reproduction of the work of art. The Frankfurt School of philosophers, including most notably Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, and Herbert Marcuse—after their emigration to the United States—played a key role in introducing Marxist assessments of culture into the mainstream of American academic life. These thinkers became associated with what is known as “Critical theory,” one of the constituent components of which was a critique of the instrumental use of reason in advanced capitalist culture. “Critical theory” held to a distinction between the high cultural heritage of Europe and the mass culture produced by capitalist societies as an instrument of domination. “Critical theory” sees in the structure of mass cultural forms—jazz, Hollywood film, advertising—a replication of the structure of the factory and the workplace. Creativity and cultural production in advanced capitalist societies were always already co-opted by the entertainment needs of an economic system that requires sensory stimulation and recognizable cliché and suppressed the tendency for sustained deliberation.

The major Marxist influences on literary theory since the Frankfurt School have been Raymond Williams and Terry Eagleton in Great Britain and Frank Lentricchia and Fredric Jameson in the United States. Williams is associated with the New Left political movement in Great Britain and the development of “Cultural Materialism” and the Cultural Studies Movement, originating in the 1960s at Birmingham University’s Center for Contemporary Cultural Studies. Eagleton is known both as a Marxist theorist and as a popularizer of theory by means of his widely read overview, Literary Theory . Lentricchia likewise became influential through his account of trends in theory, After the New Criticism . Jameson is a more diverse theorist, known both for his impact on Marxist theories of culture and for his position as one of the leading figures in theoretical postmodernism. Jameson’s work on consumer culture, architecture, film, literature and other areas, typifies the collapse of disciplinary boundaries taking place in the realm of Marxist and postmodern cultural theory. Jameson’s work investigates the way the structural features of late capitalism—particularly the transformation of all culture into commodity form—are now deeply embedded in all of our ways of communicating.

5. Structuralism and Poststructuralism

Like the “New Criticism,” “Structuralism” sought to bring to literary studies a set of objective criteria for analysis and a new intellectual rigor. “Structuralism” can be viewed as an extension of “Formalism” in that that both “Structuralism” and “Formalism” devoted their attention to matters of literary form (i.e. structure) rather than social or historical content; and that both bodies of thought were intended to put the study of literature on a scientific, objective basis. “Structuralism” relied initially on the ideas of the Swiss linguist, Ferdinand de Saussure. Like Plato, Saussure regarded the signifier (words, marks, symbols) as arbitrary and unrelated to the concept, the signified, to which it referred. Within the way a particular society uses language and signs, meaning was constituted by a system of “differences” between units of the language. Particular meanings were of less interest than the underlying structures of signification that made meaning itself possible, often expressed as an emphasis on “langue” rather than “parole.” “Structuralism” was to be a metalanguage, a language about languages, used to decode actual languages, or systems of signification. The work of the “Formalist” Roman Jakobson contributed to “Structuralist” thought, and the more prominent Structuralists included Claude Levi-Strauss in anthropology, Tzvetan Todorov, A.J. Greimas, Gerard Genette, and Barthes.

The philosopher Roland Barthes proved to be a key figure on the divide between “Structuralism” and “Poststructuralism.” “Poststructuralism” is less unified as a theoretical movement than its precursor; indeed, the work of its advocates known by the term “Deconstruction” calls into question the possibility of the coherence of discourse, or the capacity for language to communicate. “Deconstruction,” Semiotic theory (a study of signs with close connections to “Structuralism,” “Reader response theory” in America (“Reception theory” in Europe), and “Gender theory” informed by the psychoanalysts Jacques Lacan and Julia Kristeva are areas of inquiry that can be located under the banner of “Poststructuralism.” If signifier and signified are both cultural concepts, as they are in “Poststructuralism,” reference to an empirically certifiable reality is no longer guaranteed by language. “Deconstruction” argues that this loss of reference causes an endless deferral of meaning, a system of differences between units of language that has no resting place or final signifier that would enable the other signifiers to hold their meaning. The most important theorist of “Deconstruction,” Jacques Derrida, has asserted, “There is no getting outside text,” indicating a kind of free play of signification in which no fixed, stable meaning is possible. “Poststructuralism” in America was originally identified with a group of Yale academics, the Yale School of “Deconstruction:” J. Hillis Miller, Geoffrey Hartmann, and Paul de Man. Other tendencies in the moment after “Deconstruction” that share some of the intellectual tendencies of “Poststructuralism” would included the “Reader response” theories of Stanley Fish, Jane Tompkins, and Wolfgang Iser.

Lacanian psychoanalysis, an updating of the work of Sigmund Freud, extends “Postructuralism” to the human subject with further consequences for literary theory. According to Lacan, the fixed, stable self is a Romantic fiction; like the text in “Deconstruction,” the self is a decentered mass of traces left by our encounter with signs, visual symbols, language, etc. For Lacan, the self is constituted by language, a language that is never one’s own, always another’s, always already in use. Barthes applies these currents of thought in his famous declaration of the “death” of the Author: “writing is the destruction of every voice, of every point of origin” while also applying a similar “Poststructuralist” view to the Reader: “the reader is without history, biography, psychology; he is simply that someone who holds together in a single field all the traces by which the written text is constituted.”

Michel Foucault is another philosopher, like Barthes, whose ideas inform much of poststructuralist literary theory. Foucault played a critical role in the development of the postmodern perspective that knowledge is constructed in concrete historical situations in the form of discourse; knowledge is not communicated by discourse but is discourse itself, can only be encountered textually. Following Nietzsche, Foucault performs what he calls “genealogies,” attempts at deconstructing the unacknowledged operation of power and knowledge to reveal the ideologies that make domination of one group by another seem “natural.” Foucaldian investigations of discourse and power were to provide much of the intellectual impetus for a new way of looking at history and doing textual studies that came to be known as the “New Historicism.”

6. New Historicism and Cultural Materialism

“New Historicism,” a term coined by Stephen Greenblatt, designates a body of theoretical and interpretive practices that began largely with the study of early modern literature in the United States. “New Historicism” in America had been somewhat anticipated by the theorists of “Cultural Materialism” in Britain, which, in the words of their leading advocate, Raymond Williams describes “the analysis of all forms of signification, including quite centrally writing, within the actual means and conditions of their production.” Both “New Historicism” and “Cultural Materialism” seek to understand literary texts historically and reject the formalizing influence of previous literary studies, including “New Criticism,” “Structuralism” and “Deconstruction,” all of which in varying ways privilege the literary text and place only secondary emphasis on historical and social context. According to “New Historicism,” the circulation of literary and non-literary texts produces relations of social power within a culture. New Historicist thought differs from traditional historicism in literary studies in several crucial ways. Rejecting traditional historicism’s premise of neutral inquiry, “New Historicism” accepts the necessity of making historical value judgments. According to “New Historicism,” we can only know the textual history of the past because it is “embedded,” a key term, in the textuality of the present and its concerns. Text and context are less clearly distinct in New Historicist practice. Traditional separations of literary and non-literary texts, “great” literature and popular literature, are also fundamentally challenged. For the “New Historicist,” all acts of expression are embedded in the material conditions of a culture. Texts are examined with an eye for how they reveal the economic and social realities, especially as they produce ideology and represent power or subversion. Like much of the emergent European social history of the 1980s, “New Historicism” takes particular interest in representations of marginal/marginalized groups and non-normative behaviors—witchcraft, cross-dressing, peasant revolts, and exorcisms—as exemplary of the need for power to represent subversive alternatives, the Other, to legitimize itself.

Louis Montrose, another major innovator and exponent of “New Historicism,” describes a fundamental axiom of the movement as an intellectual belief in “the textuality of history and the historicity of texts.” “New Historicism” draws on the work of Levi-Strauss, in particular his notion of culture as a “self-regulating system.” The Foucaldian premise that power is ubiquitous and cannot be equated with state or economic power and Gramsci’s conception of “hegemony,” i.e., that domination is often achieved through culturally-orchestrated consent rather than force, are critical underpinnings to the “New Historicist” perspective. The translation of the work of Mikhail Bakhtin on carnival coincided with the rise of the “New Historicism” and “Cultural Materialism” and left a legacy in work of other theorists of influence like Peter Stallybrass and Jonathan Dollimore. In its period of ascendancy during the 1980s, “New Historicism” drew criticism from the political left for its depiction of counter-cultural expression as always co-opted by the dominant discourses. Equally, “New Historicism’s” lack of emphasis on “literariness” and formal literary concerns brought disdain from traditional literary scholars. However, “New Historicism” continues to exercise a major influence in the humanities and in the extended conception of literary studies.

7. Ethnic Studies and Postcolonial Criticism

“Ethnic Studies,” sometimes referred to as “Minority Studies,” has an obvious historical relationship with “Postcolonial Criticism” in that Euro-American imperialism and colonization in the last four centuries, whether external (empire) or internal (slavery) has been directed at recognizable ethnic groups: African and African-American, Chinese, the subaltern peoples of India, Irish, Latino, Native American, and Philipino, among others. “Ethnic Studies” concerns itself generally with art and literature produced by identifiable ethnic groups either marginalized or in a subordinate position to a dominant culture. “Postcolonial Criticism” investigates the relationships between colonizers and colonized in the period post-colonization. Though the two fields are increasingly finding points of intersection—the work of bell hooks, for example—and are both activist intellectual enterprises, “Ethnic Studies and “Postcolonial Criticism” have significant differences in their history and ideas.

“Ethnic Studies” has had a considerable impact on literary studies in the United States and Britain. In W.E.B. Dubois, we find an early attempt to theorize the position of African-Americans within dominant white culture through his concept of “double consciousness,” a dual identity including both “American” and “Negro.” Dubois and theorists after him seek an understanding of how that double experience both creates identity and reveals itself in culture. Afro-Caribbean and African writers—Aime Cesaire, Frantz Fanon, Chinua Achebe—have made significant early contributions to the theory and practice of ethnic criticism that explores the traditions, sometimes suppressed or underground, of ethnic literary activity while providing a critique of representations of ethnic identity as found within the majority culture. Ethnic and minority literary theory emphasizes the relationship of cultural identity to individual identity in historical circumstances of overt racial oppression. More recently, scholars and writers such as Henry Louis Gates, Toni Morrison, and Kwame Anthony Appiah have brought attention to the problems inherent in applying theoretical models derived from Euro-centric paradigms (that is, structures of thought) to minority works of literature while at the same time exploring new interpretive strategies for understanding the vernacular (common speech) traditions of racial groups that have been historically marginalized by dominant cultures.

Though not the first writer to explore the historical condition of postcolonialism, the Palestinian literary theorist Edward Said’s book Orientalism is generally regarded as having inaugurated the field of explicitly “Postcolonial Criticism” in the West. Said argues that the concept of “the Orient” was produced by the “imaginative geography” of Western scholarship and has been instrumental in the colonization and domination of non-Western societies. “Postcolonial” theory reverses the historical center/margin direction of cultural inquiry: critiques of the metropolis and capital now emanate from the former colonies. Moreover, theorists like Homi K. Bhabha have questioned the binary thought that produces the dichotomies—center/margin, white/black, and colonizer/colonized—by which colonial practices are justified. The work of Gayatri C. Spivak has focused attention on the question of who speaks for the colonial “Other” and the relation of the ownership of discourse and representation to the development of the postcolonial subjectivity. Like feminist and ethnic theory, “Postcolonial Criticism” pursues not merely the inclusion of the marginalized literature of colonial peoples into the dominant canon and discourse. “Postcolonial Criticism” offers a fundamental critique of the ideology of colonial domination and at the same time seeks to undo the “imaginative geography” of Orientalist thought that produced conceptual as well as economic divides between West and East, civilized and uncivilized, First and Third Worlds. In this respect, “Postcolonial Criticism” is activist and adversarial in its basic aims. Postcolonial theory has brought fresh perspectives to the role of colonial peoples—their wealth, labor, and culture—in the development of modern European nation states. While “Postcolonial Criticism” emerged in the historical moment following the collapse of the modern colonial empires, the increasing globalization of culture, including the neo-colonialism of multinational capitalism, suggests a continued relevance for this field of inquiry.

8. Gender Studies and Queer Theory

Gender theory came to the forefront of the theoretical scene first as feminist theory but has subsequently come to include the investigation of all gender and sexual categories and identities. Feminist gender theory followed slightly behind the reemergence of political feminism in the United States and Western Europe during the 1960s. Political feminism of the so-called “second wave” had as its emphasis practical concerns with the rights of women in contemporary societies, women’s identity, and the representation of women in media and culture. These causes converged with early literary feminist practice, characterized by Elaine Showalter as “gynocriticism,” which emphasized the study and canonical inclusion of works by female authors as well as the depiction of women in male-authored canonical texts.

Feminist gender theory is postmodern in that it challenges the paradigms and intellectual premises of western thought, but also takes an activist stance by proposing frequent interventions and alternative epistemological positions meant to change the social order. In the context of postmodernism, gender theorists, led by the work of Judith Butler, initially viewed the category of “gender” as a human construct enacted by a vast repetition of social performance. The biological distinction between man and woman eventually came under the same scrutiny by theorists who reached a similar conclusion: the sexual categories are products of culture and as such help create social reality rather than simply reflect it. Gender theory achieved a wide readership and acquired much its initial theoretical rigor through the work of a group of French feminist theorists that included Simone de Beauvoir, Luce Irigaray, Helene Cixous, and Julia Kristeva, who while Bulgarian rather than French, made her mark writing in French. French feminist thought is based on the assumption that the Western philosophical tradition represses the experience of women in the structure of its ideas. As an important consequence of this systematic intellectual repression and exclusion, women’s lives and bodies in historical societies are subject to repression as well. In the creative/critical work of Cixous, we find the history of Western thought depicted as binary oppositions: “speech/writing; Nature/Art, Nature/History, Nature/Mind, Passion/Action.” For Cixous, and for Irigaray as well, these binaries are less a function of any objective reality they describe than the male-dominated discourse of the Western tradition that produced them. Their work beyond the descriptive stage becomes an intervention in the history of theoretical discourse, an attempt to alter the existing categories and systems of thought that found Western rationality. French feminism, and perhaps all feminism after Beauvoir, has been in conversation with the psychoanalytic revision of Freud in the work of Jacques Lacan. Kristeva’s work draws heavily on Lacan. Two concepts from Kristeva—the “semiotic” and “abjection”—have had a significant influence on literary theory. Kristeva’s “semiotic” refers to the gaps, silences, spaces, and bodily presence within the language/symbol system of a culture in which there might be a space for a women’s language, different in kind as it would be from male-dominated discourse.

Masculine gender theory as a separate enterprise has focused largely on social, literary, and historical accounts of the construction of male gender identities. Such work generally lacks feminisms’ activist stance and tends to serve primarily as an indictment rather than a validation of male gender practices and masculinity. The so-called “Men’s Movement,” inspired by the work of Robert Bly among others, was more practical than theoretical and has had only limited impact on gender discourse. The impetus for the “Men’s Movement” came largely as a response to the critique of masculinity and male domination that runs throughout feminism and the upheaval of the 1960s, a period of crisis in American social ideology that has required a reconsideration of gender roles. Having long served as the de facto “subject” of Western thought, male identity and masculine gender theory awaits serious investigation as a particular, and no longer universally representative, field of inquiry.

Much of what theoretical energy of masculine gender theory currently possesses comes from its ambiguous relationship with the field of “Queer theory.” “Queer theory” is not synonymous with gender theory, nor even with the overlapping fields of gay and lesbian studies, but does share many of their concerns with normative definitions of man, woman, and sexuality. “Queer theory” questions the fixed categories of sexual identity and the cognitive paradigms generated by normative (that is, what is considered “normal”) sexual ideology. To “queer” becomes an act by which stable boundaries of sexual identity are transgressed, reversed, mimicked, or otherwise critiqued. “Queering” can be enacted on behalf of all non-normative sexualities and identities as well, all that is considered by the dominant paradigms of culture to be alien, strange, unfamiliar, transgressive, odd—in short, queer. Michel Foucault’s work on sexuality anticipates and informs the Queer theoretical movement in a role similar to the way his writing on power and discourse prepared the ground for “New Historicism.” Judith Butler contends that heterosexual identity long held to be a normative ground of sexuality is actually produced by the suppression of homoerotic possibility. Eve Sedgwick is another pioneering theorist of “Queer theory,” and like Butler, Sedgwick maintains that the dominance of heterosexual culture conceals the extensive presence of homosocial relations. For Sedgwick, the standard histories of western societies are presented in exclusively in terms of heterosexual identity: “Inheritance, Marriage, Dynasty, Family, Domesticity, Population,” and thus conceiving of homosexual identity within this framework is already problematic.

9. Cultural Studies

Much of the intellectual legacy of “New Historicism” and “Cultural Materialism” can now be felt in the “Cultural Studies” movement in departments of literature, a movement not identifiable in terms of a single theoretical school, but one that embraces a wide array of perspectives—media studies, social criticism, anthropology, and literary theory—as they apply to the general study of culture. “Cultural Studies” arose quite self-consciously in the 80s to provide a means of analysis of the rapidly expanding global culture industry that includes entertainment, advertising, publishing, television, film, computers and the Internet. “Cultural Studies” brings scrutiny not only to these varied categories of culture, and not only to the decreasing margins of difference between these realms of expression, but just as importantly to the politics and ideology that make contemporary culture possible. “Cultural Studies” became notorious in the 90s for its emphasis on pop music icons and music video in place of canonical literature, and extends the ideas of the Frankfurt School on the transition from a truly popular culture to mass culture in late capitalist societies, emphasizing the significance of the patterns of consumption of cultural artifacts. “Cultural Studies” has been interdisciplinary, even antidisciplinary, from its inception; indeed, “Cultural Studies” can be understood as a set of sometimes conflicting methods and approaches applied to a questioning of current cultural categories. Stuart Hall, Meaghan Morris, Tony Bennett and Simon During are some of the important advocates of a “Cultural Studies” that seeks to displace the traditional model of literary studies.

10. References and Further Reading

A. general works on theory.

- Culler, Jonathan. Literary Theory: A Very Short Introduction . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- During, Simon. Ed. The Cultural Studies Reader . London: Routledge, 1999.

- Eagleton, Terry. Literary Theory . Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

- Lentricchia, Frank. After the New Criticism . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980.

- Moore-Gilbert, Bart, Stanton, Gareth, and Maley, Willy. Eds. Postcolonial Criticism . New York: Addison, Wesley, Longman, 1997.

- Rice, Philip and Waugh, Patricia. Eds. Modern Literary Theory: A Reader . 4 th edition.

- Richter, David H. Ed. The Critical Tradition: Classic Texts and Contemporary Trends . 2 nd Ed. Bedford Books: Boston, 1998.

- Rivkin, Julie and Ryan, Michael. Eds. Literary Theory: An Anthology . Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell, 1998.

b. Literary and Cultural Theory

- Adorno, Theodor. The Culture Industry: Selected Essays on Mass Culture . Ed. J. M. Bernstein. London: Routledge, 2001.

- Althusser, Louis. Lenin and Philosophy: And Other Essays. Trans. Ben Brewster. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1971.

- Auerbach, Erich. Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature. Trans.

- Willard R. Trask. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1953.

- Bakhtin, Mikhail. The Dialogic Imagination. Trans. Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1981.

- Barthes, Roland. Image—Music—Text. Trans. Stephen Heath. New York: Hill and Wang, 1994.

- Barthes, Roland. The Pleasure of the Text . Trans. Richard Miller. New York: Hill and Wang, 1975.

- Beauvoir, Simone de. The Second Sex . Tr. H.M. Parshley. New York: Knopf, 1953.

- Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations. Ed. Hannah Arendt. Trans. Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken, 1988.

- Brooks, Cleanth. The Well-Wrought Urn: Studies in the Structure of Poetry. New York: Harcourt, 1947.

- Derrida, Jacques. Of Grammatology . Trans. Gayatri C. Spivak. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1976.

- Dubois, W.E.B. The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches. Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co., 1903.

- Fish, Stanley. Is There a Text in This Class? The Authority of Interpretive Communities. Harvard, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980.

- Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality. Volume 1. An Introduction. Trans. Robert Hurley. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin, 1981.

- Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. New York: Vintage, 1973.

- Gates, Henry Louis. The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism . New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- hooks, bell. Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism . Boston: South End Press, 1981.

- Horkheimer, Max and Adorno, Theodor. Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments . Ed. Gunzelin Schmid Noerr. Trans. Edmund Jephcott. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2002.

- Irigaray, Luce. This Sex Which Is Not One . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1985.

- Jameson, Frederic. Postmodernism: Or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999.

- Lacan, Jacques. Ecrits: A Selection. London: Routledge, 2001.

- Lemon Lee T. and Reis, Marion J. Eds. Russian Formalist Criticism: Four Essays. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1965.

- Lukacs, Georg. The Historical Novel . Trans. Hannah and Stanley Mitchell. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1962.

- Marcuse, Herbert. Eros and Civilization . Boston: Beacon Press, 1955.

- Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Genealogy of Morals . Trans. Walter Kaufmann. New York: Vintage, 1969.

- Plato. The Collected Dialogues. Ed. Edith Hamilton and Huntington Cairns. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1961.

- Proust, Marcel. Remembrance of Things Past. Trans. C.K. Scott Moncrieff and Terence Kilmartin. New York: Vintage, 1982.

- Said, Edward. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon, 1978.

- Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Between Men . Between Men: English literature and Male Homosocial Desire . New York: Columbia University Press, 1985.

- Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky Epistemology of the Closet . London: Penguin, 1994.

- Showalter, Elaine. Ed. The New Feminist Criticism: Essays on Women, Literature, and Theory . London: Virago, 1986.

- Tompkins, Jane. Sensational Designs : the Cultural Work of American Fiction, 1790- 1860. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986.

- Wellek, Rene and Warren, Austin. Theory of Literature . 3 rd ed. New York: Harcourt Brace, 1956.

- Williams, Raymond. The Country and the City . New York: Oxford University Press, 1973.

Author Information

Vince Brewton Email: [email protected] University of North Alabama U. S. A.

An encyclopedia of philosophy articles written by professional philosophers.

beginner's guide to literary analysis

Understanding literature & how to write literary analysis.

Literary analysis is the foundation of every college and high school English class. Once you can comprehend written work and respond to it, the next step is to learn how to think critically and complexly about a work of literature in order to analyze its elements and establish ideas about its meaning.

If that sounds daunting, it shouldn’t. Literary analysis is really just a way of thinking creatively about what you read. The practice takes you beyond the storyline and into the motives behind it.

While an author might have had a specific intention when they wrote their book, there’s still no right or wrong way to analyze a literary text—just your way. You can use literary theories, which act as “lenses” through which you can view a text. Or you can use your own creativity and critical thinking to identify a literary device or pattern in a text and weave that insight into your own argument about the text’s underlying meaning.

Now, if that sounds fun, it should , because it is. Here, we’ll lay the groundwork for performing literary analysis, including when writing analytical essays, to help you read books like a critic.

What Is Literary Analysis?

As the name suggests, literary analysis is an analysis of a work, whether that’s a novel, play, short story, or poem. Any analysis requires breaking the content into its component parts and then examining how those parts operate independently and as a whole. In literary analysis, those parts can be different devices and elements—such as plot, setting, themes, symbols, etcetera—as well as elements of style, like point of view or tone.

When performing analysis, you consider some of these different elements of the text and then form an argument for why the author chose to use them. You can do so while reading and during class discussion, but it’s particularly important when writing essays.

Literary analysis is notably distinct from summary. When you write a summary , you efficiently describe the work’s main ideas or plot points in order to establish an overview of the work. While you might use elements of summary when writing analysis, you should do so minimally. You can reference a plot line to make a point, but it should be done so quickly so you can focus on why that plot line matters . In summary (see what we did there?), a summary focuses on the “ what ” of a text, while analysis turns attention to the “ how ” and “ why .”

While literary analysis can be broad, covering themes across an entire work, it can also be very specific, and sometimes the best analysis is just that. Literary critics have written thousands of words about the meaning of an author’s single word choice; while you might not want to be quite that particular, there’s a lot to be said for digging deep in literary analysis, rather than wide.

Although you’re forming your own argument about the work, it’s not your opinion . You should avoid passing judgment on the piece and instead objectively consider what the author intended, how they went about executing it, and whether or not they were successful in doing so. Literary criticism is similar to literary analysis, but it is different in that it does pass judgement on the work. Criticism can also consider literature more broadly, without focusing on a singular work.

Once you understand what constitutes (and doesn’t constitute) literary analysis, it’s easy to identify it. Here are some examples of literary analysis and its oft-confused counterparts:

Summary: In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” the narrator visits his friend Roderick Usher and witnesses his sister escape a horrible fate.

Opinion: In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” Poe uses his great Gothic writing to establish a sense of spookiness that is enjoyable to read.

Literary Analysis: “Throughout ‘The Fall of the House of Usher,’ Poe foreshadows the fate of Madeline by creating a sense of claustrophobia for the reader through symbols, such as in the narrator’s inability to leave and the labyrinthine nature of the house.

In summary, literary analysis is:

- Breaking a work into its components

- Identifying what those components are and how they work in the text

- Developing an understanding of how they work together to achieve a goal

- Not an opinion, but subjective

- Not a summary, though summary can be used in passing

- Best when it deeply, rather than broadly, analyzes a literary element

Literary Analysis and Other Works

As discussed above, literary analysis is often performed upon a single work—but it doesn’t have to be. It can also be performed across works to consider the interplay of two or more texts. Regardless of whether or not the works were written about the same thing, or even within the same time period, they can have an influence on one another or a connection that’s worth exploring. And reading two or more texts side by side can help you to develop insights through comparison and contrast.

For example, Paradise Lost is an epic poem written in the 17th century, based largely on biblical narratives written some 700 years before and which later influenced 19th century poet John Keats. The interplay of works can be obvious, as here, or entirely the inspiration of the analyst. As an example of the latter, you could compare and contrast the writing styles of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Edgar Allan Poe who, while contemporaries in terms of time, were vastly different in their content.

Additionally, literary analysis can be performed between a work and its context. Authors are often speaking to the larger context of their times, be that social, political, religious, economic, or artistic. A valid and interesting form is to compare the author’s context to the work, which is done by identifying and analyzing elements that are used to make an argument about the writer’s time or experience.

For example, you could write an essay about how Hemingway’s struggles with mental health and paranoia influenced his later work, or how his involvement in the Spanish Civil War influenced his early work. One approach focuses more on his personal experience, while the other turns to the context of his times—both are valid.

Why Does Literary Analysis Matter?

Sometimes an author wrote a work of literature strictly for entertainment’s sake, but more often than not, they meant something more. Whether that was a missive on world peace, commentary about femininity, or an allusion to their experience as an only child, the author probably wrote their work for a reason, and understanding that reason—or the many reasons—can actually make reading a lot more meaningful.

Performing literary analysis as a form of study unquestionably makes you a better reader. It’s also likely that it will improve other skills, too, like critical thinking, creativity, debate, and reasoning.

At its grandest and most idealistic, literary analysis even has the ability to make the world a better place. By reading and analyzing works of literature, you are able to more fully comprehend the perspectives of others. Cumulatively, you’ll broaden your own perspectives and contribute more effectively to the things that matter to you.

Literary Terms to Know for Literary Analysis

There are hundreds of literary devices you could consider during your literary analysis, but there are some key tools most writers utilize to achieve their purpose—and therefore you need to know in order to understand that purpose. These common devices include:

- Characters: The people (or entities) who play roles in the work. The protagonist is the main character in the work.

- Conflict: The conflict is the driving force behind the plot, the event that causes action in the narrative, usually on the part of the protagonist

- Context : The broader circumstances surrounding the work political and social climate in which it was written or the experience of the author. It can also refer to internal context, and the details presented by the narrator

- Diction : The word choice used by the narrator or characters

- Genre: A category of literature characterized by agreed upon similarities in the works, such as subject matter and tone

- Imagery : The descriptive or figurative language used to paint a picture in the reader’s mind so they can picture the story’s plot, characters, and setting

- Metaphor: A figure of speech that uses comparison between two unlike objects for dramatic or poetic effect

- Narrator: The person who tells the story. Sometimes they are a character within the story, but sometimes they are omniscient and removed from the plot.

- Plot : The storyline of the work

- Point of view: The perspective taken by the narrator, which skews the perspective of the reader

- Setting : The time and place in which the story takes place. This can include elements like the time period, weather, time of year or day, and social or economic conditions

- Symbol : An object, person, or place that represents an abstract idea that is greater than its literal meaning

- Syntax : The structure of a sentence, either narration or dialogue, and the tone it implies

- Theme : A recurring subject or message within the work, often commentary on larger societal or cultural ideas

- Tone : The feeling, attitude, or mood the text presents

How to Perform Literary Analysis

Step 1: read the text thoroughly.

Literary analysis begins with the literature itself, which means performing a close reading of the text. As you read, you should focus on the work. That means putting away distractions (sorry, smartphone) and dedicating a period of time to the task at hand.

It’s also important that you don’t skim or speed read. While those are helpful skills, they don’t apply to literary analysis—or at least not this stage.

Step 2: Take Notes as You Read

As you read the work, take notes about different literary elements and devices that stand out to you. Whether you highlight or underline in text, use sticky note tabs to mark pages and passages, or handwrite your thoughts in a notebook, you should capture your thoughts and the parts of the text to which they correspond. This—the act of noticing things about a literary work—is literary analysis.

Step 3: Notice Patterns

As you read the work, you’ll begin to notice patterns in the way the author deploys language, themes, and symbols to build their plot and characters. As you read and these patterns take shape, begin to consider what they could mean and how they might fit together.

As you identify these patterns, as well as other elements that catch your interest, be sure to record them in your notes or text. Some examples include:

- Circle or underline words or terms that you notice the author uses frequently, whether those are nouns (like “eyes” or “road”) or adjectives (like “yellow” or “lush”).

- Highlight phrases that give you the same kind of feeling. For example, if the narrator describes an “overcast sky,” a “dreary morning,” and a “dark, quiet room,” the words aren’t the same, but the feeling they impart and setting they develop are similar.

- Underline quotes or prose that define a character’s personality or their role in the text.

- Use sticky tabs to color code different elements of the text, such as specific settings or a shift in the point of view.

By noting these patterns, comprehensive symbols, metaphors, and ideas will begin to come into focus.

Step 4: Consider the Work as a Whole, and Ask Questions

This is a step that you can do either as you read, or after you finish the text. The point is to begin to identify the aspects of the work that most interest you, and you could therefore analyze in writing or discussion.

Questions you could ask yourself include:

- What aspects of the text do I not understand?

- What parts of the narrative or writing struck me most?

- What patterns did I notice?

- What did the author accomplish really well?

- What did I find lacking?

- Did I notice any contradictions or anything that felt out of place?

- What was the purpose of the minor characters?

- What tone did the author choose, and why?

The answers to these and more questions will lead you to your arguments about the text.

Step 5: Return to Your Notes and the Text for Evidence

As you identify the argument you want to make (especially if you’re preparing for an essay), return to your notes to see if you already have supporting evidence for your argument. That’s why it’s so important to take notes or mark passages as you read—you’ll thank yourself later!

If you’re preparing to write an essay, you’ll use these passages and ideas to bolster your argument—aka, your thesis. There will likely be multiple different passages you can use to strengthen multiple different aspects of your argument. Just be sure to cite the text correctly!

If you’re preparing for class, your notes will also be invaluable. When your teacher or professor leads the conversation in the direction of your ideas or arguments, you’ll be able to not only proffer that idea but back it up with textual evidence. That’s an A+ in class participation.

Step 6: Connect These Ideas Across the Narrative

Whether you’re in class or writing an essay, literary analysis isn’t complete until you’ve considered the way these ideas interact and contribute to the work as a whole. You can find and present evidence, but you still have to explain how those elements work together and make up your argument.

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay

When conducting literary analysis while reading a text or discussing it in class, you can pivot easily from one argument to another (or even switch sides if a classmate or teacher makes a compelling enough argument).

But when writing literary analysis, your objective is to propose a specific, arguable thesis and convincingly defend it. In order to do so, you need to fortify your argument with evidence from the text (and perhaps secondary sources) and an authoritative tone.

A successful literary analysis essay depends equally on a thoughtful thesis, supportive analysis, and presenting these elements masterfully. We’ll review how to accomplish these objectives below.

Step 1: Read the Text. Maybe Read It Again.

Constructing an astute analytical essay requires a thorough knowledge of the text. As you read, be sure to note any passages, quotes, or ideas that stand out. These could serve as the future foundation of your thesis statement. Noting these sections now will help you when you need to gather evidence.

The more familiar you become with the text, the better (and easier!) your essay will be. Familiarity with the text allows you to speak (or in this case, write) to it confidently. If you only skim the book, your lack of rich understanding will be evident in your essay. Alternatively, if you read the text closely—especially if you read it more than once, or at least carefully revisit important passages—your own writing will be filled with insight that goes beyond a basic understanding of the storyline.

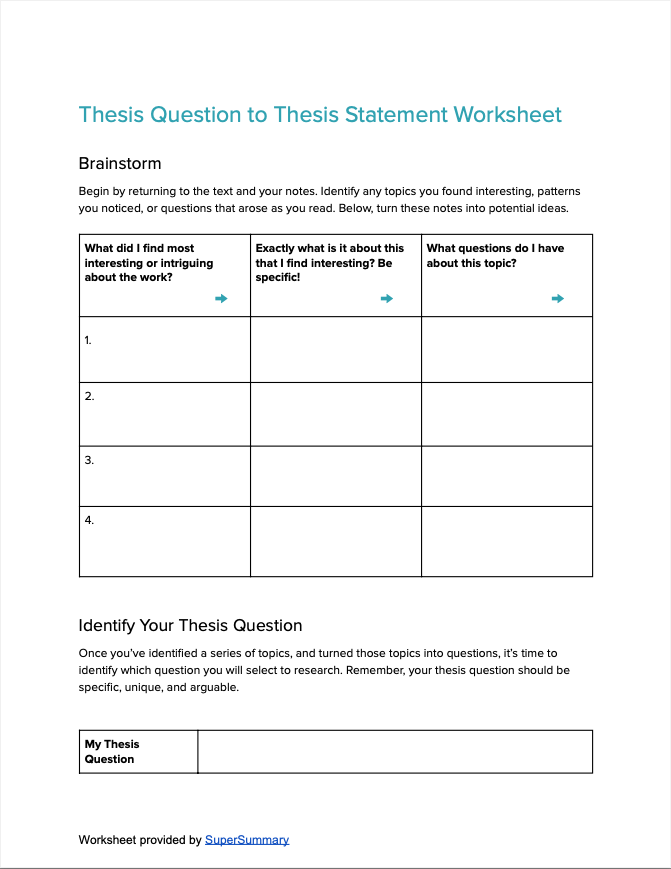

Step 2: Brainstorm Potential Topics

Because you took detailed notes while reading the text, you should have a list of potential topics at the ready. Take time to review your notes, highlighting any ideas or questions you had that feel interesting. You should also return to the text and look for any passages that stand out to you.