- Search Menu

- About OAH Magazine of History

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

The bigger picture, teaching the lesson, reflections and conclusions.

- < Previous

Interpreting John Brown: Infusing Historical Thinking into the Classroom

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Bruce A. Lesh, Interpreting John Brown: Infusing Historical Thinking into the Classroom, OAH Magazine of History , Volume 25, Issue 2, April 2011, Pages 46–50, https://doi.org/10.1093/oahmag/oar003

- Permissions Icon Permissions

John Brown has been subject to constant reinterpretation in the century and half since he led the 1859 attack on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry. In this photograph by John H. Tarbell, an unnamed African American man in Ashville, North Carolina is holding a copy of Joseph Barry's The Strange Story of Harper's Ferry , published a year earlier. Judging by the man's age, he was alive in 1859, and quite possibly enslaved. One can only wonder at his interpretation of John Brown. (Courtesy of Library of Congress)

On the cusp of his December 1859 execution for treason, murder, and inciting a slave rebellion, John Brown handed a note to his guard which read, “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land can never be purged away but with blood.” Although the institution of slavery was purged in the crucible of the American Civil War, John Brown's determination to expose and end chattel slavery still resonates. The multiple legacies of slavery and questions about the efficacy of violence as a tool for change in a democratic society continually bring historians and teachers back to the complicated life of John Brown. When students consider Brown's contributions to the American narrative, lines between advocacy and criminality, contrasts between intensity and obsession, and differences between democratic ideals and harsh reality are brought to the surface. To this day, artists, authors, historians, political activists, and creators of popular culture maintain a fascination with the antebellum rights-warrior and his death.

This continuing interest in John Brown presents a great teaching opportunity. Not only can we help to situate John Brown within the context of his era, but we can explore how historical interpretations of the man and his actions have changed over time. The lesson I describe in this article asks students to consider Brown's biography, multiple artistic representations of the abolitionist, as well as historical and contemporary viewpoints in order to develop an evidence-based interpretation of how this controversial historical figure should be commemorated. Students conduct an analysis of the diverse, and often conflicting, historical sources, and then apply their interpretations to the development of a historical marker that would be placed at the Harper's Ferry National Historical Park. In this sense, Brown provides a unique opportunity for students to examine a figure whose actions, and their attendant meanings, tell us as much about antebellum America and the origins of the Civil War as they do about our own time.

Challenging students to develop an interpretation of John Brown ties into my broader philosophy about history instruction. Research on history education, going back nearly a century, indicates that few students retain, understand, or enjoy their school experiences with history ( 1 ). This dismal track record stems from a teaching method that relies primarily on the memorization of names and dates. To limit the study and assessment of history to a student's ability to regurgitate these facts hides the true nature of the discipline. History, at its core, is the study of questions and the analysis of evidence in an effort to develop and defend thoughtful responses. For students to truly be engaged with the past, they must be taught thinking skills that mirror those employed by historians. Recent research suggests that students are more capable of evaluating historical sources, using them to develop an interpretation, and articulating their interpretations in a variety of formats. When doing so, students become powerful thinkers rather than consumers of a predetermined narrative path ( 2 ).

Asking questions about causality, chronology, continuity and change over time , multiple perspectives , contingency , empathy , significance, and motivation enable students to use the substantive information to address essential historical issues. In addition, students must be taught to approach historical sources with the understanding that they are repositories of information that reflect a particular temporal, geographic, and socio-economic perspective. Analyzing a variety of historical sources—be they diaries, artifacts, music, images, or monographs—enables students to scrutinize the remnants of the past and apply this evidence to the task at hand. Employing these historical thinking skills in a classroom setting empowers students to use the names, dates, and events to develop, revise, and defend evidence-based interpretations of the questions that drive the study of history ( 3 ).

Given the path illuminated in the scholarship and my own experiences with teaching history to high school students for eighteen years, I planned the John Brown lesson with an emphasis on source work and student development of evidence-based explanations focused on a key historical question. At the conclusion of the lesson, my students are asked to determine how John Brown and his life should be commemorated. Engaging in many, though not all, of the considerations involved in public history, my students set out to interpret Brown's life for a twenty-first century audience. To do so, they must get to know the individual, his actions, and how Brown was seen by both his contemporaries and historians from his time to the present.

Born in the first year of the nineteenth century to a devoutly Calvinist family, John Brown credits witnessing a slave being beaten with a shovel as the origin of his devotion to the anti-slavery cause. Unlike most of the abolitionists that arose in the 1830s, Brown was dedicated to both the abolition of chattel slavery and racial equality. This commitment was exemplified in his 1838 decision to escort a free black to sit in his family pew. This bold act led to his family's expulsion from the church. In a fruitless attempt to become economically solvent, Brown moved to Springfield, Massachusetts in 1846 to develop his wool business. In Springfield, Brown befriended, lived among, and attended church alongside African Americans. Brown's sincere empathy for the plight of the slave was reflected in a letter written by abolitionist Frederick Douglass after meeting Brown. Douglass, who made a trip to Springfield expressly to meet Brown, stated that Brown was “in sympathy, a black man, and as deeply interested in our cause, as though his own soul had been pierced with the iron of slavery.” During this meeting, Brown revealed what he called his “Subterranean Pass Way.” Using the Appalachian Mountains as a base, this plan envisioned a rebellion that would arm slaves, encourage their revolt, and direct people northward to freedom. It was in Springfield where Brown first revealed the elements of what would become the final act of his life: a raid on the South to promote a slave rebellion.

In 1849, Brown moved his family to North Elba, New York to live on a communal farm created by abolitionist Gerrit Smith ( Figure 2 ). Living with black families was a clear indication of Brown's commitment to a biracial society. In 1851, reacting to the Fugitive Slave provisions of the Compromise of 1850, Brown returned to Springfield and established the League of Gileadites. Dedicated to protecting escaped slaves from slave catchers, the League was a concrete expression of Brown's visceral distaste for federal complicity with the institution of slavery. Brown vehemently expressed his passion for equality in May of 1858, when he presented his “Provisional Constitution and Ordinances for the People of the United States” to an anti-slavery convention in Ontario, Canada. Essentially a new constitution for a slavery-free United States, the document stated that:

In 1848, John Brown learned of abolitionist Gerrit Smith's offer of free land to blacks in the Adirondacks. The next year, Brown moved his family to North Elba, New York to join this experiment. Though he soon left for “Bloody” Kansas, he considered North Elba his home and asked to be buried there. In 1935, the John Brown Memorial Association dedicated this statue, designed by Joseph P. Pollia, just north of the gravesite, now part of the John Brown Farm State Historic Site: < http://nysparks.state.ny.us/historic-sites/29/details.aspx > (Courtesy of photographer David Blakie, < http://davidblaikie.ca/ >)

Whereas slavery, throughout its entire existence in the United States, is none other than a most barbarous, unprovoked, and unjustifiable war of one portion of its citizens upon another portion-the only conditions of which are perpetual imprisonment and hopeless servitude or absolute extermination-in utter disregard and violation of those eternal and self-evident truths set forth in our Declaration of Independence:

Therefore, we, citizens of the United States, and the oppressed people who, by a recent decision of the Supreme Court, [The Dred Scott Decisions] are declared to have no rights which the white man is bound to respect, together with all other people degraded by the laws thereof, do, for the time being, ordain and establish for ourselves the following Provisional Constitution and Ordinances, the better to protect our persons, property, lives, and liberties, and to govern our actions ( 4 ).

This was a clear statement of Brown's opposition to slavery and his dedication to equality. Yet for Brown, it was not words, but actions, that seared his name into the pantheon of American history. Speaking to the community of former slaves in Canada, Brown announced his plan to invade the American South and foment a slave rebellion using the mountains of western Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Alabama to provide cover for his uprising. It would be this uprising that occupied much of his travel, speaking, and fundraising between 1858 and his death in 1859.

Brown's first overt public action took place in May of 1856. In Kansas, Brown led a group of men on a raid that killed five proslavery men along the Pottawatomie Creek. Though Brown claimed not to have participated in the actual murders, the brutality of the act has come to symbolize the violence that struck Kansas territory as a result of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Violence as a tool for change was again employed by Brown in 1858 in Missouri. Brown entered Vernon County, just across the Kansas border, and attacked several proslavery farmers, stole horses and wagons, and secured the freedom of eleven enslaved persons. His raid led to the deaths of several farmers, and consequently a bounty of $250 was placed on his head by President James Buchanan and his name was splashed over newspapers across the nation. After traveling more than a thousand miles over eighty-plus days, Brown delivered the newly liberated former-slaves into the hands of Canada and freedom.

Secretly funded by six abolitionists from Massachusetts, armed with thousands of pikes purchased in Connecticut, driven by his deep disdain for slavery, and supported by twenty-one other men, Brown headed to western Maryland to reconnoiter for his final attempt to foment a rebellion aimed at destroying the institution of slavery. The raid on the federal arsenal in Harper's Ferry, Virginia was initiated on the evening of October 16, 1859. In what quickly developed into a rout, more than half of Brown's followers were killed and the remaining eight, including Brown, were captured the following day. Indicted, found guilty, and sentenced to die, John Brown was hanged in Charlestown, Virginia on December 2, 1859 ( 5 ).

John Brown of Osawatomie spake on his dying day: ‘I will not have to shrive my soul a priest in Slavery's pay; But let some poor slave-mother whom I have striven to free, With her children, from the gallows-stair put up a prayer for me!’ John Brown of Ossawatomie, they led him out to die; And lo! a poor slave-mother with her little child pressed nigh: Then the bold, blue eye grew tender, and the old harsh face grew mild, As he stooped between the jeering ranks and kissed the negro's child! The shadows of his stormy life that moment fell apart, And they who blamed the bloody hand forgave the loving heart; That kiss from all its guilty means redeemed the good intent, And round the grisly fighter's hair the martyr's aureole bent! ( 6 )

The notion of Brown consecrating his sacrifice for slaves with a kiss to the cheek of a slave child found visual form in the 1860 painting, John Brown on His Way to Execution by Louis Ransom. It was further popularized by an 1863 Currier and Ives colored lithograph entitled John Brown , and subtitled Meeting the slave-mother and her child on the steps of Charlestown jail on his way to execution. Thomas Noble's John Brown's Blessing appeared in 1867, a redrawn Currier and Ives, John Brown—The Martyr debuted in 1870. Finally, in 1884, Thomas Hovenden painted his memorialization of the mythical kiss in his Last Moments of John Brown (See cover image) ( 7 ). This introductory element of the lesson fertilizes the pedagogical ground for growing a deep and meaningful investigation of Brown.

Based on an 1859 painting by Louis Ransom, this Currier & Ives lithograph is entitled John Brown. Meeting the slave-mother and her child on the steps of Charlestown jail on his way to execution . A precursor of Thomas Hovenden's 1884 painting on the cover of this issue, it offers a darker, more symbolic depiction of the mythical event. To Brown's left, we see his elderly jailer, a wealthy slaveholder, and a militia member dressed in an aristocratic uniform. To his right stands the embodied spirit of the American Revolution somberly assessing the scene and a soldier pushing back an enslaved woman who suckles her light-skinned child, perhaps the product of a rape by her master. Behind her stands a broken and neglected statue of Justice. (Courtesy of Library of Congress)

A one-page biographical reading, assigned for homework, is used to structure class discussion of Brown's upbringing, his early efforts to address slavery in Springfield, Massachusetts, and the events leading up to his attack on the federal arsenal in Harper's Ferry. Emphasis is drawn to Brown's religious beliefs, his role in “Bleeding Kansas,” his raid into Missouri, and finally the ill-fated Harper's Ferry Raid. To firmly place Brown's actions within the growing sectional mentality of the 1850s, I discuss with students the various sectional reactions to Brown's failed raid. With the contrasting images of Brown fresh in their minds, I inform students that it is their task to determine how Brown should be memorialized historically.

To deepen their analysis of Brown, students are assigned one of several readings. Selected to represent contrasting interpretations of the man and his actions, these readings are intended to complicate students’ investigation. I traditionally select six sources from the list of “Further Readings” located at the end of the article, but I have provided all of the potential sources on the online version of the lesson materials. Historiographically, the discussion of Brown has evolved from the hero-worship of James Redpath and Oswald Garrison Villard to critical analysis of his mental state as found in the work of Bruce Catton and James C. Malin.

Students are organized so that all of the six sources are represented within a group. Each student then presents the interpretation of John Brown expounded by their source. Next, to assist students in better understanding each perspective, I identify some relevant background information of the various authors and the time period in which they wrote. It is important to ensure that students consider authorship, context, and subtext as they derive information from a historical source. By confronting the milieu in which Malcolm X spoke about Brown, or how personal biography impacts Villard's telling of the Brown story, students are forced to consider the sources not as words, but as a perspective informed by and reflecting the social, cultural, economic, and political background of the author and the time period of its construction. Exposing the subtext of each source illuminates for students how John Brown has been interpreted differently and empowers them to develop their own evidence-based interpretations of the past.

Since I teach a forty-five minute class period, my lesson usually breaks in the midst of students sharing the evidence provided by their sources. At times, I will ask students, as homework between day one and two of the lesson, to consult one Northern and one Southern editorial found at < http://history.furman.edu/editorials/see.py >. These articles, and the context and subtext that influence their perspectives, help complicate, but also deepen, our final discussion on how to commemorate John Brown.

After sharing and taking notes, students are asked to consider how they feel John Brown and his actions should be commemorated. Small group discussions of the topic eventually become a large group debate. It is key to this phase of the lesson that students base their interpretations on the evidence they have confronted. Issues of authorship and context add to our discussion about what John Brown means to the telling of American history and how his efforts should be memorialized.

At the conclusion of the lesson, students are asked to apply the evidence they have examined to one of two assessments. The first option is to complete a historical marker that is to be placed at the entrance of the Harper's Ferry National Historic Park. The second is to select five items that would be displayed in the museum at the same park, explain why they were selected, and how these items help to describe John Brown and account for his actions. These assessments place students in a position where they must adhere to the basic historical facts in order to develop and defend an interpretation of the choice they made about commemorating John Brown. Either iteration of the assessment requires students to identify what historical sources informed their decisions and how these sources influenced their choices.

Students have a hard time wrapping their minds around John Brown. Go figure, so do historians. Brown has been the subject of hundreds of books, articles, documentaries, and other forms of historical interpretation. My students, just as historians, are drawn into the complexities of Brown's personality and the actions he takes over the course of his life.

When crafting their interpretations for the historical marker, students tend to run in one of three directions. A large number take a middle of the road approach. After examining the multiple images and textual viewpoints of Brown, they stick to what they see as the pertinent facts. Gone are incendiary adjectives or overt ideological typecasting of Brown and his actions. In many ways, their markers are reminiscent of those produced by the National Park Service for many historical figures and events. The second third stress Brown's actions in both Missouri and Harper's Ferry, but do not address his beliefs. They reflect in their analysis that they are unwilling or unable to determine if he was crazy, obsessively focused, or simply devoted to his cause. The final third interpret and represent Brown as a madman whose actions intentionally set the nation barreling towards civil discord.

What strikes me about this lesson is that students come to see history as alive and interpretive, rather than inert and handed down from some central authoritative body. Most instruments that measure student achievement in history would simply ask students to select the response in a multiple choice question that correctly identifies the impact of Brown's actions. This is achieved within the first five minutes of my lesson. Instead, it is the pastness of Brown that captures their interest and generates in-depth analysis, far beyond a discussion that establishes the basis for an answer to a multiple-choice question. The power and depth of the discussion generated about Brown has been the impetus for me to apply this structure to other historical figures and events. Individuals such as Nat Turner, Daniel Shays, or Eugene Debs and events such as the Haymarket Affair, Busing in Boston, or the Tet Offensive become ripe for deep historical investigation once I realized that my students could do so. The depth of connection my students make with these watershed events and transitional figures far outweighs the time it takes to plan or execute such investigations.

At the same time, the power of images to quickly connect students to a topic is also readily evident when I teach this lesson. The images empower students to become more critical in their analysis of the textual sources they are asked to read. Because the images are so stark, both in contrast to one another as well as individually, students look for similar differences within the text. This transfer of critical reading from the more comfortable image analysis to the more difficult text is a key ingredient for students as they evolve their abilities to think historically. When students are taught to be aware that historical sources are not simply repositories of information, but instead vehicles for communicating an author's perspective on an individual, event, or historical idea, they are enabled to begin crossing the bridge from the “unnatural act of thinking historically” towards a mindset more parallel to that employed by historians.

Ultimately, what my students enjoy is the opportunity to examine the past rather than having it examined for them. The occasion to apply historical thinking skills to determine how to commemorate the life and actions of one of the most divisive figures in American History empowers students to examine multiple sources of historical evidence, develop, revise, and defend evidence-based interpretations, and grapple with key questions of the past. Just as John Brown taught us that challenging the norms of American society is a difficult endeavor, so too is challenging the manner in which we approach teaching history.

J. Carelton Bell and David F. McCollum, “A Study of the Attainments of Pupils in United States History,” Journal of Educational Psychology 8 (1917): 257–74; James P. Shaver, O.L. Davis, Jr., and Suzanne Helburn, “The Status of Social Studies Education: Impressions from Three NSF Studies,” Social Education (February 1979): 150–53; James B. Schick, “What do Students Really Think of History?” The History Teacher , 24 (May 1991): 331–42; T he Nation's Report Card: U.S. History 2006. National Assessment of Educational Progress at grades 4, 8, and 12 (Washington, D.C.: National Center for Education Statistics, United States Department of Education, 2006); Anne Neal and Jerry Martin, Losing America's Memory: Historical Illiteracy in the 21st Century (Washington, D.C.: American Council of Trustees and Alumni, 2000); Dale Whittington, “What Have 17-Year Olds Known in the Past?” American Educational Research Journal 28 (Winter 1991): 759–80.

Bruce VanSledright. The Challenge of Rethinking History Education: On Practices, Theories, and Policy (New York: Routledge, 2010); Nikki Mandell and Bobbie Malone. Thinking Like a Historian: Rethinking History Instruction, A Framework to Enhance and Improve Teaching and Learning (Madison: Wisconsin Historical Society Press, 2007); Keith Barton. “Research on Students’ Historical Thinking and Learning.” AHA Perspectives Magazine , October 2004, 19–21.

Sam Wineburg, Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts: Charting the Future of Teaching the Past (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001); Bruce VanSledright, I n Search of America's Past: Learning to Read History in Elementary School (New York: Teacher's College Press, 2002); Suzanne M. Donovan and John D. Bransford, eds. How Students Learn: History in the Classroom (Washington DC: The National Academies Press, 2005); Lendol Calder, “Uncoverage: Toward a Signature Pedagogy for the History Survey.” Journal of American History , March 2006, 1358–1370.

“John Brown's Provisional Constitution,” University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law, < http://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/johnbrown/brownconstitution.html .>.

David Reynolds, John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights (New York: Vintage Books, 2005). Jonathan Earle, John Brown's Raid on Harper's Ferry: A Brief History with Documents (New York: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2008).

John Greenleaf Whittier, “Brown of Ossawatomie,” The Lost Museum, < http://chnm.gmu.edu/lostmuseum/lm/144/ .>.

James C. Malin, “ The John Brown Legend in Pictures, Kissing the Negro Baby,” Kansas Historical Quarterly 8 (1939): 339–441, < www.kancoll.org/khq/1939/39_4_malin.htm .>.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Email alerts

Citing articles via, affiliations.

- Online ISSN 1938-2340

- Print ISSN 0882-228X

- Copyright © 2024 Organization of American Historians

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

John Brown and Harpers Ferry

Written by: Bill of Rights Institute

By the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain how regional differences related to slavery caused tension in the years leading up to the Civil War

- Explain the political causes of the Civil War

Suggested Sequencing

Use this Narrative alongside the John Brown: Hero or Villain? DBQ Lesson plan to allow students to fully evaluate John Brown’s approach to abolitionism.

During his lifetime John Brown was greatly admired as a hero by some and fiercely hated by others. Abolitionists who supported the end of slavery generally praised his actions as necessary to destroy the institution; southerners were usually horrified by the violence he used to achieve his ends. Others, such as politician Abraham Lincoln, questioned the means even if they agreed with the end of abolishing slavery. Even today, John Brown provokes a variety of responses among historians and biographers. Judgments of his characterize him as everything from a self-righteous, fundamentalist terrorist to a crusading abolitionist for freedom.

The 1830s and 1840s witnessed increasing radicalism on the slavery issue with the rise of abolitionism. In 1831, abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison launched his newspaper, The Liberator , with the principled, uncompromising words about eradicating slavery: “I will not equivocate – I will not excuse – I will not retreat a single inch – AND I WILL BE HEARD.” Brown was swept up by such unbending abolitionist thinking, which was consistent with his Calvinist Puritan faith. He asserted that he had an “ eternal war with slavery” and dedicated himself to the cause when abolitionist editor Elijah Lovejoy was killed by a mob in 1837. “Here before God, in the presence of these witnesses, in this church, [I] consecrate [my] life to the destruction of slavery,” Brown pledged during a church meeting.

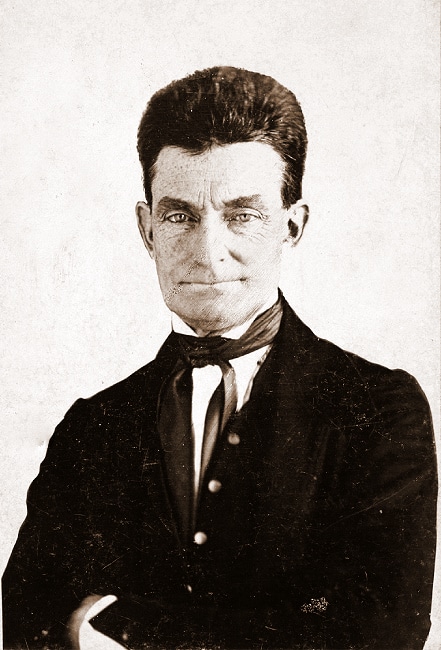

This daguerreotype of John Brown was taken in 1846 or 1847 by an African American portraitist named Augustus Washington. Brown’s intensity is evident in his determined gaze and his raised right hand, as if taking an oath.

Over the next few decades, Brown failed in several business ventures and moved frequently, but he remained devoted to the cause of freeing slaves from bondage. He thought the Underground Railroad was inadequate and studied guerrilla warfare tactics. He settled near Lake Placid, New York, to manage a colony of free blacks and there organized a secret society to prevent slavecatchers from capturing their quarry in the North. Outraged by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, he urged violent opposition to the law and the immoral slave system generally.

In 1854, the Kansas-Nebraska Act allowed the residents of those territories to decide whether to enter the Union as a free or slave state, according to the doctrine of popular sovereignty, and overturned the Missouri Compromise. Brown thought a southern Slave Power had conspired to destroy republican institutions, and he followed several of his sons who had moved to the newly created Kansas Territory. Southerners and northerners alike were flooding the territory to decide the issue. Deeply divided over slavery, they set up rival territorial governments in different towns. Tension was rife and erupted into sporadic violence, threatening to cause civil war. Brown had raised money from northern abolitionists and purchased firearms, swords, and knives to fight in the impending war. He and his sons joined the Liberty Guards militia and the Pottawatomie Rifles militia company to fight proslavery forces.

On the night of May 24, 1856, a frenzied Brown unleashed his righteous vengeance against on nearby southerners he presumed were complicit in the evil slave system. He and his sons knocked on the doors of nearby cabins of several proslavery families who were too poor to own slaves. Armed with his pistols, hunting knives, and swords, Brown and his sons took five adult males prisoner at gunpoint and led them outside into the darkness while their wives and children cowered inside. They hacked the hostages to death and shot a wounded prisoner in the head. The mutilated bodies were discovered the following day.

When asked about the deeds, Brown said, “I did not do it, but I approved of it.” He proclaimed his godly righteousness in murdering proslavery advocates: “God is my judge. We were justified under the circumstances.” He went into hiding in the woods and soon returned to the Northeast to raise money, weapons, and recruits for another scheme against southern slavery, believing murder was morally permissible if done in the name of what was right.

Brown traveled around New England, speaking to wealthy, prominent abolitionists, including Theodore Parker, William Lloyd Garrison, Julia Ward Howe, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Frederick Douglass, Charles Sumner, Henry David Thoreau, and Ralph Waldo Emerson, among others. He received some encouragement and funding, but many were skeptical of his violent means and remarks, such as that it would be better if a whole generation should die a violent death than that a word of the Bible or Declaration of Independence be violated. Brown was incredulous that others did not share his zeal or commitment, especially in the wake of the 1857 Supreme Court decision in Dred Scott declaring blacks incapable of citizenship and the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional. Meanwhile, he used the donations he collected to order hundreds of pikes and firearms to launch his war to liberate the slaves.

As he informed a few confidants, Brown intended to lead an army to raid the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry in what then was Virginia. He planned to seize the weapons there and distribute them to liberated slaves to start a violent race war in which enslaved persons killed their masters and fled to a revolutionary state in the Appalachian Mountains. In the summer of 1859, he assumed a false identity and moved to a farmhouse near Harpers Ferry. Only 21 recruits (16 whites and five African Americans) joined Brown to initiate his slave revolt. As months ebbed away in hiding, he wrote a political manifesto modeled on the Declaration of Independence and entitled “A Declaration of Liberty by the Representatives of the Slave Population of the United States of America,” and a new constitution guaranteeing equal rights to all races.

On the night of October 16, the small, but righteous band finally moved out in the dark to begin the war. Three men were assigned to hide a cache of weapons at a schoolhouse as a staging point for the slave rebellion. The rest marched on Harpers Ferry and easily took prisoner a night watchman and an arsenal guard when they broke into the armory. Brown dispatched a handful of men in a wagon loaded with weapons to break into nearby homes, liberate their slaves, and take hostages. The rebels wounded a watchman and accidentally shot and killed a free black railroad worker. As the town’s population was roused, church bells warning of a slave insurrection pealed throughout the countryside and telegraph messages spread word of the raid across the nation. Brown’s men had taken prisoner some 40 townspeople who had been going to work and taken cover in a firehouse.

Daylight brought nothing but disaster for the ill-conceived raid. Brown’s rebels engaged in a shootout with the townspeople and lost one of the band to a sniper. Armed militia arrived and cut off any escape. When Brown sent three emissaries to negotiate a cease-fire, they were gunned down. When five of his men tried to retreat to the Shenandoah River, two were shot and killed, one drowned, and two (one free black and one enslaved man) were captured and nearly hanged. The raiders shot and killed the mayor of the town, only fueling the anger of the citizens of Harpers Ferry. In the chaos, some 30 of Brown’s prisoners had escaped, and by nightfall he only had four or five healthy men left. One of his sons died of his wounds and another barely clung to life, but Brown resolved to fight to the end to achieve his goal of liberating the slaves.

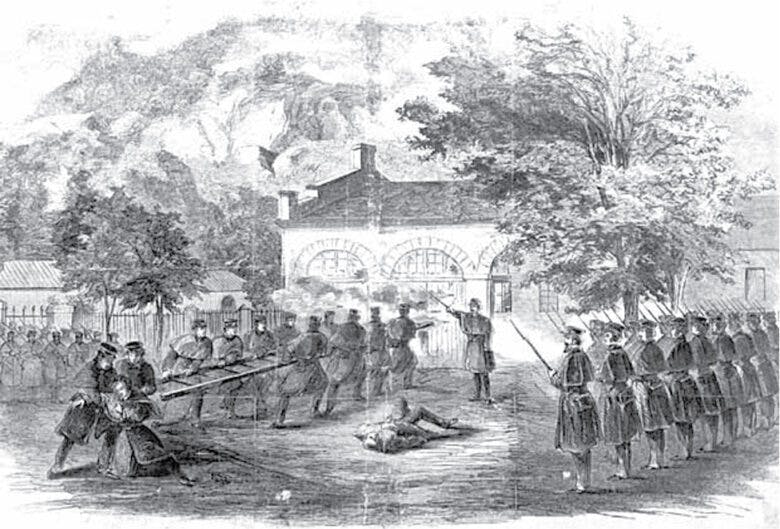

In this depiction, published in Harpers Weekly in November 1859, U.S. Marines are shown attacking John Brown’s improvised fortifications at Harpers Ferry.

The following day, Colonel Robert E. Lee arrived with Lieutenant J.E.B. Stuart and 90 Marines. Stuart tried to negotiate a surrender, but Brown refused. The Marines battered down the heavy door and stormed into the building where Brown and his men were amid gunfire and thrusting swords and bayonets. After his other men had all gone down in the mêlée, Brown was slashed by a saber before being knocked unconscious.

A few days later, Brown was tried for murder, inciting slave insurrection, and treason against the state of Virginia and was convicted on all charges. Predictably, many antislavery activists praised his actions, while southern defenders of slavery were horrified. Transcendentalist author Henry David Thoreau delivered an oration praising Brown for breaking an unjust law. “Are laws to be enforced simply because they are made?” Thoreau asked.

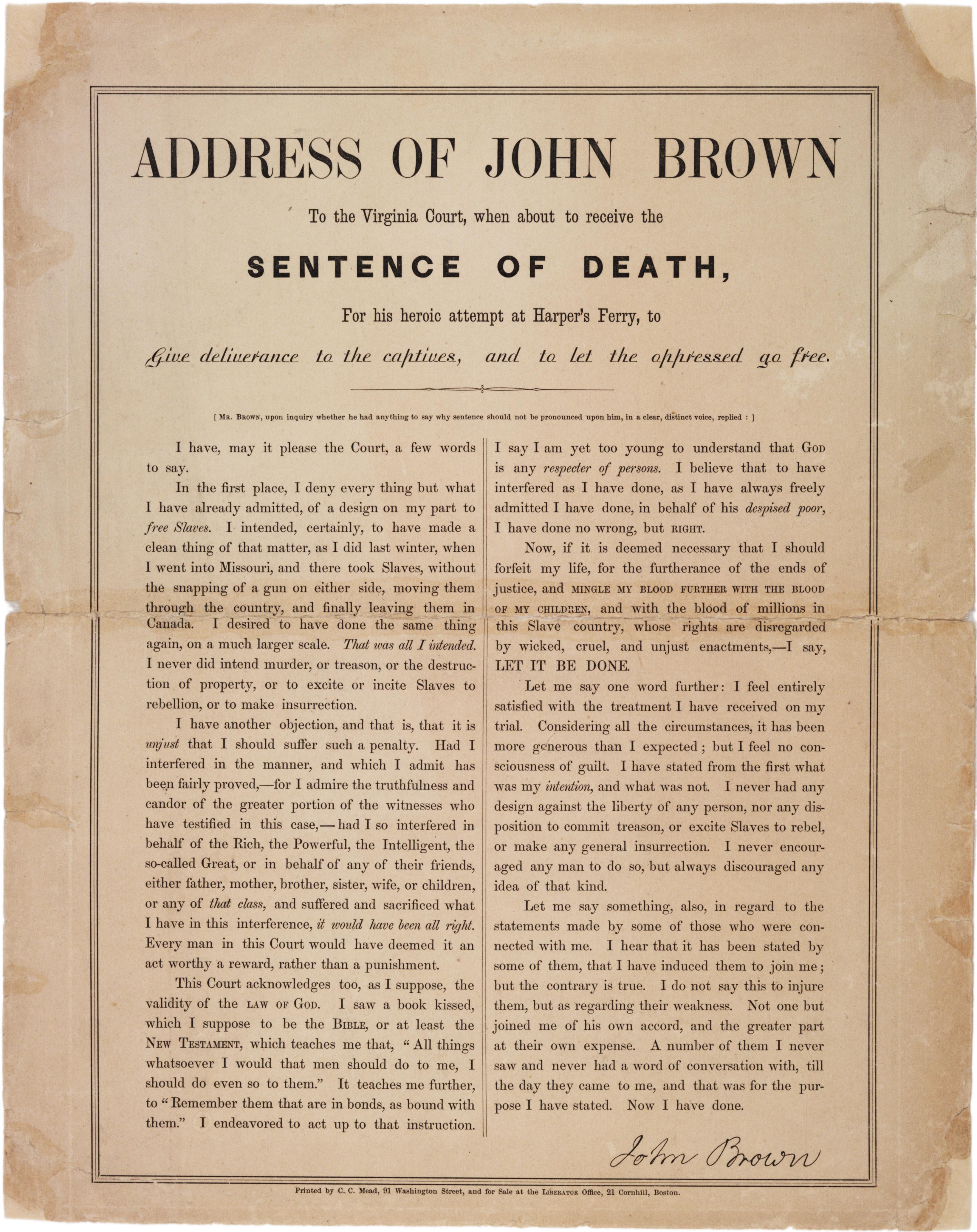

This broadside was published in November 1859, after John Brown was convicted of murder and treason. Brown’s deeds at Harpers Ferry horrified some, but others supported his extreme actions.

During his sentencing, Brown was allowed to make a statement, which he concluded by saying, “If it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country, whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments, I submit. So let it be done!”

On December 2, a wagon brought him to a gallows on a cornfield surrounded by 1,500 militiamen to guard against any rescue attempt. There Brown was bound, hanged, and placed in a coffin. That morning, he had handed one of the guards a scrap of paper with a prophetic warning: “I, John Brown am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with Blood.” Brown’s raid helped fuel the sectionalism that led to the bloody Civil War between North and South and claimed the lives of more than 600,000 Americans.

Review Questions

1. Why did John Brown oppose the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854)?

- He did not want the territories to enter the Union as free states.

- He thought a southern Slave Power was attempting to spread slavery in the western territories.

- He wanted the settlement of Kansas and the decision for statehood to be peaceful.

- He was mostly concerned with preserving the integrity of the Missouri Compromise.

2. What was John Brown’s method of freeing the enslaved persons held in bondage in the United States?

- He supported compensated emancipation and resettlement in Africa.

- He preferred disunion with slaveholders because of the institution of slavery.

- He supported the nonviolent emancipation of enslaved persons by the outlawing of slavery across the country.

- He advocated arming enslaved persons to fight a violent racial war for their liberation.

3. By 1859, John Brown was viewed as a hero by

- moderate Republicans

- Abraham Lincoln

- radical abolitionists

4. In his tactics and beliefs regarding slavery, John Brown most resembled

- Harriet Tubman

- Harriet Beecher Stowe

5. Which event triggered a response by John Brown that foreshadowed his actions in Harpers Ferry in 1859?

- Compromise of 1850

- “Bleeding Kansas”

- Dred Scott decision

- Election of Abraham Lincoln

This image from 1863 depicts John Brown meeting an enslaved woman on the steps of the Charlestown courthouse. He is on his way to execution after being convicted of treason. The drawing was originally captioned: “Regarding with a look of compassion a Slave-mother and Child who obstructed the passage on his way to the Scaffold. –Capt. Brown stooped and kissed the Child–then met his fate.”

By the time this illustration was made, the popular view of John Brown

- had not changed because most Americans considered him mentally unstable

- had moderated because most Americans viewed him as a flawed human being

- had declined as people came to realize the horrors of the Civil War

- had become more positive because many viewed Brown as a hero for the abolitionist cause

Free Response Questions

- John Brown espoused violence, including guerrilla warfare tactics, in his fight against slavery. Compare his actions with those of other abolitionists such as Harriet Tubman, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and William Lloyd Garrison.

- Analyze the impact of John Brown’s raid on the start of the Civil War.

AP Practice Questions

“We ask not that the slave should lie, As lies his master, at his ease, Beneath a silken canopy, Or in the shade of blooming trees. We ask not “eye for eye,” that all Who forge the chain and ply the whip Should feel their torture, while the thrall Should wield the scourge of mastership. We mourn not that the man should toil. ‘Tis nature’s need. ‘Tis God’s decree. But let the hand that tills the soil Be, like the wind that fans it, free. Melody to “Old Hundred’ Hymn” The Abolitionist Hymn (Author unknown, circa 1850s)

1. A historian might use this song as evidence to support

- the way a lack of copyright and patent precedent led to widespread violations

- the role religious affiliation played in the spread of abolitionist sentiment

- the popular appeal of Stephen Douglas in the 1860 presidential election

- the impact of Irish immigration on the Free Soil movement

2. Which group would most likely support the song’s point of view?

- Radical abolitionists such as John Brown

- Advocates of free black repatriation to the African state of Liberia

- Members of the Free Soil party

- Antislavery advocates such as Harriet Beecher Stowe

3. The song most directly resulted from what earlier movement?

- The Republican view of motherhood

- The Market Revolution

- The Second Great Awakening

- The Seneca Falls Convention

Primary Sources

Benjamin S. Jones, Editor. “John Brown’s Speech from the Scaffold,” Anti-slavery Bugle, December 03, 1859: “https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83035487/1859-12-03/ed-1/seq-1/

Francis Smith Report: The Execution of John Brown, January 16, 1860: https://www.vmi.edu/archives/civil-war-and-new-market/john-brown-execution/

John Brown’s Speech to the Court at his Trial, by John Brown (1800-59), November 2, 1859: https://nationalcenter.org/JohnBrown’sSpeech.html

Speech of Senator Stephen A. Douglas, Delivered in the U.S. Senate, January 28, 1860: http://www.wvculture.org/history/jbexhibit/bbspr02-0012.html

Virginia Legislature, Title Report of the Joint Committee on the Harpers Ferry Outrages, January 26, 1860: http://www.wvculture.org/history/jbexhibit/vajointcommitteereport.html

Suggested Resources

Carton, Evan. Patriotic Treason . Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2006.

Earle, Johnathan. John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry: A Brief History with Documents . Boston: Bedford Books, 2008.

Holt, Michael F. The Fate of Their Country: Politicians, Slavery Extension, and the Coming of the Civil War . New York: Hill and Wang, 2005.

Horwitz, Tony. Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid that Sparked the Civil War . New York: Henry Holt, 2011.

Oates, Stephen B. To Purge This Land with Blood: A Biography of John Brown . Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1970.

Peterson, Merrill D. John Brown: The Legend Revisited . Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2002.

Potter, David M. The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861 . New York: Harper, 2011.

Reynolds, David. John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights . New York: Knopf, 2005.

John Brown: APUSH Topics to Study for Test Day

John Brown was a radical abolitionist who believed that the only way to abolish slavery was to arm slaves and to spur their insurrection. To successfully respond to John Brown APUSH questions, it is important to know the effects John Brown’s actions had on pro and antislavery voices, and to look especially at his raid on Harpers Ferry.

Who is John Brown?

John Brown was a northern abolitionist who moved about the country supporting antislavery causes, which included giving land to fugitive slaves and participating in the Underground Railroad. He was unsatisfied with the results of the peaceful protests of the mainstream abolitionist movement and became a violent radical for the cause. In 1855, Brown and his sons moved to Kansas where they took part in guerrilla warfare during the Bleeding Kansas crisis, murdering five pro-slavery settlers.

John Brown’s actions in Kansas brought him national attention. He moved to Virginia and began hatching an elaborate plot to fund an army that would raid Harpers Ferry , arm slaves, and begin an uprising. Brown led 21 men on his raid, where they attacked and occupied the federal armory for two days. Brown’s army was surrounded and many of his men were killed. Brown himself was eventually captured, charged of murder, conspiring, and treason, and hanged.

Important years to note for John Brown:

- 1856: John Brown murders five proslavery settlers in Kansas during the Bleeding Kansas crisis

- 1859: John Brown raids Harpers Ferry

Why is John Brown so important?

John Brown was a divisive figure. His ideas attracted many abolitionists who were no longer content with the institution of slavery and grew impatient for emancipation. He remained, however, a radical figure, and his methods, especially after the Harpers Ferry attack, were condemned by mainstream abolitionists. Southern Democrats and other pro-slavery Americans, however, were convinced that Brown was acting on the behest of Republicans, and that his Harpers Ferry raid was just the beginning of an advanced abolitionist plot to overthrow the system of slavery. John Brown’s actions likely hastened the coming of war, as they emboldened northern abolitionists and convinced those with an interest in slavery that if republicans took control of the government slavery in the South would be ended.

What are some historical people and events related to John Brown?

- Bleeding Kansas: The crisis that followed the passing of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Fighting ensued as Kansas citizens fought over whether or not the territory would be a free or slave state.

- Robert E. Lee: Led the military forces that captured Brown at Harpers Ferry.

What example question about John Brown might come up on the APUSH exam?

“The newspapers seem to ignore, or perhaps are really ignorant of the fact, that there are at least as many as two or three individuals to a town throughout the North who think much as the present speaker does about him and his enterprise. I do not hesitate to say that they are an important and growing party. We aspire to be something more than stupid and timid chattels, pretending to read history and our Bibles, but desecrating every house and every day we breathe in. Perhaps anxious politicians may prove that only seventeen white men and five Negroes were concerned in the late [raid on Harpers Ferry]; but their very anxiety to prove this might suggest to themselves that all is not told. Why do they still dodge the truth? They are so anxious because of a dim consciousness of the fact, which they do not distinctly face, that at least a million of the free inhabitants of the United States would have rejoiced if it had succeeded. They at most only criticize the tactics.” -“A Plea for Captain John Brown” by Henry David Thoreau, 1859 ( Source ) Thoreau’s assessment of Harpers Ferry seems to support A) the Democrats’ assertion that slavery should be a matter of popular sovereignty. B) the Republicans’ conviction that John Brown’s actions were fair and just. C) the South’s fears that the North aimed not to contain slavery, but to end it. D) the North’s concern that the South would secede over John Brown’s actions.

The correct answer is (C). After John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, Southern Democrats and others with a stake in the institution of slavery feared that it was a sign of the insurrection to come. Republicans insisted that they did not condone Brown’s actions, but abolitionists like Thoreau came out in support of Brown and stoked the South’s fears that, should the northern Republicans win Congress and the White House, slavery would be ended.

Sarah is an educator and writer with a Master’s degree in education from Syracuse University who has helped students succeed on standardized tests since 2008. She loves reading, theater, and chasing around her two kids.

View all posts

More from Magoosh

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Home — Essay Samples — History — Historical Figures — John Brown

Essays on John Brown

John brown essay topics for college students.

As a college student, choosing the right essay topic is crucial. It not only sets the tone for your entire paper but also allows you to explore your creativity and personal interests. This page aims to provide you with a variety of essay topics related to John Brown, ensuring that you find the perfect topic for your next assignment.

Essay Types and Topics

Argumentative essay topics.

- The impact of John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry

- The role of violence in John Brown's abolitionist activities

- John Brown's legacy and its relevance in modern society

Paragraph Example:

An argumentative essay on John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry must carefully examine the historical context and the impact of this event on the abolitionist movement. As such, it is important to consider the various perspectives and debates surrounding this pivotal moment in American history. This essay seeks to provide a balanced analysis of the raid and its implications.

It is evident that John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry ignited intense debates about the moral and ethical implications of using violence to achieve social change. While opinions on Brown's actions remain divided, it is undeniable that his legacy continues to inspire discussions about the nature of activism and the pursuit of justice.

Compare and Contrast Essay Topics

- John Brown and Frederick Douglass: A comparative analysis

- The impact of John Brown's actions compared to other abolitionists

- John Brown's ideology versus other prominent figures in the abolitionist movement

Descriptive Essay Topics

- A day in the life of John Brown

- The landscapes and settings associated with John Brown's activities

- The emotional impact of John Brown's legacy on local communities

Persuasive Essay Topics

- Why John Brown should be celebrated as a hero

- The relevance of John Brown's principles in contemporary social justice movements

- Challenging misconceptions about John Brown's character and motivations

Narrative Essay Topics

- An eyewitness account of John Brown's raid on Harper's Ferry

- A fictional retelling of John Brown's life from the perspective of a supporter

- The impact of John Brown's legacy on future generations

Engagement and Creativity

When selecting an essay topic, consider your personal interests and the aspects of John Brown's life and impact that intrigue you the most. By choosing a topic that resonates with you, you can engage more deeply with the subject matter and produce a more compelling essay.

Educational Value

Each essay type offers unique opportunities for developing critical thinking and writing skills. Argumentative essays encourage you to analyze historical events and engage in persuasive writing, while descriptive essays allow you to hone your descriptive abilities. Compare and contrast essays help you develop analytical thinking, and narrative essays enable you to explore storytelling techniques and personal reflection.

John Brown Hero

John brown: a terrorist and a patriot, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Discussion on Whether John Brown Was a Terrorist

The life of john brown and his role in the anti-slavery movement, john brown – a slavery abolitionist with terrorist methods, john brown: the battle between martyr and madman, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Review of a Plea for John Brown by Henry David Thoreau

The life of john brown and his impact on civil rights movement, john brown's life and fight against slavery.

May 9, 1800

December 2, 1859 (aged 59)

Involvement in Bleeding Kansas; Raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia

Abolitionism

Brown was born on May 9, 1800, in Torrington, Connecticut. At young age, Brown witnessed an enslaved African American boy being beaten, that moment created his own abolitionism. Brown experienced great financial difficulties from the 1820s to the 1850s.

Brown established the League of Gileadites, a group for protecting Black citizens from slave hunters. Brown believed in using violent means to end slavery. In 1856, became involved in the conflict, known as Pottawatomie massacre.

In 1858, Brown liberated a group of enslaved people from a Missouri. By early 1859, Brown was leading raids to free enslaved people. In 1859, Brown led 21 men on a raid of the federal armory of Harpers Ferry in Virginia, but they were defeated by military forces led by Robert E. Lee. Brown was captured, and on November 2 he was sentenced to death.

Brown was hanged on December 2, 1859, at the age of 59.

Six years after Brown’s death, slavery ultimately came to an end in the United States in 1865. Brown’s action helped to hasten the war that would bring emancipation.

Relevant topics

- Frederick Douglass

- Alexander Hamilton

- Katherine Johnson

- Mahatma Gandhi

- John Proctor

- Robert E Lee

- Florence Nightingale

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

John Brown’s final speech, 1859

A spotlight on a primary source by john brown.

Brown’s plan soon went awry. Angry townspeople and local militia companies trapped his men in the armory. About twenty-four hours later, US troops commanded by Colonel Robert E. Lee arrived and stormed the engine house. Five of Brown’s party escaped, ten were killed, and seven, including Brown himself, were taken prisoner. Brown was tried in a Virginia court, although he had attacked federal property.

The trial’s high point came at its end when Brown was permitted to make a speech, which appears on this broadside printed in December 1859 by the abolitionist newspaper, the Liberator . In his address, Brown asserted that he "never did intend murder, or treason, or the destruction of property, or to excite or incite Slaves to rebellion, or to make insurrection," but rather wanted only to "free Slaves." He defended his actions as righteous and just, saying that "to have interfered as I have done—In behalf of His despised poor, was not wrong but right."

Brown also told the court that he was at peace with his actions and their consequences, proclaiming: “Now if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice and MINGLE MY BLOOD FURTHER WITH THE BLOOD OF MY CHILDREN, and with the blood of millions in this slave country whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel, and unjust enactments—I submit; so LET IT BE DONE.”

Brown’s speech convinced many northerners that this grizzled man of fifty-nine was not an extremist but rather a martyr to the cause of freedom.

The Virginia court, however, found him guilty of treason, conspiracy, and murder, and he was sentenced to die. Brown was hanged on December 2, 1859, and his body was buried on his family farm at North Elba, New York.

A full transcript is available.

In the first place, I deny every thing but what I have already admitted, of a design on my part to free Slaves. I intended, certainly, to have made a clean thing of that matter, as I did last winter, when I went into Missouri, and there took Slaves, without the snapping of a gun on either side, moving them through the country, and finally leaving them in Canada. I desired to have done the same thing again, on a much larger scale. That was all I intended. I never did intend murder, or treason, or the destruction of property, or to excite or incite Slaves to rebellion, or to make insurrection.

Questions for Discussion

Read the document introduction, examine the transcript, and the image, and apply your knowledge of American history in order to answer the questions that follow.

- Illustrations and descriptions of John Brown published in magazines and newspapers during his lifetime and following his execution frequently describe a fiery, violent, wild-eyed radical. How closely do those descriptions match the words in his speech?

- How did John Brown use Biblical scripture to explain and justify his actions?

- Why was it particularly appropriate that John Brown’s final statement to the court was reprinted in the Liberator ?

- Imagine that you are the prosecuting attorney for Virginia. Create a short final statement to the jury summarizing your reasons for bringing the case against John Brown.

- John Brown has been referred to by some as an honorable man and true patriot and by others as a radical terrorist. Which is most appropriate? Defend your answer using historical facts.

A printer-friendly version is available here .

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter..

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

Undergraduate Admission

How to apply.

Applications to Brown are submitted online via the Common Application. The online system will guide you through the process of providing the supporting credentials appropriate to your status as a first-year or transfer applicant.

- Applying to Brown

Common Application

Begin by creating an account on the Common Application website. Once registered, you will need to add Brown University to your list of colleges by the College Search tab.

The Common Application is divided into three sections:

- Information common to all the schools to which you are applying

- Brown University specific questions

- School forms submitted by your school counselor and academic instructors

Apply Now with the Common Application

Brown University Specific Questions

Questions specific to Brown, including our essays for the 2023-2024 application cycle, are found in the section labeled "Questions." If you are applying to the eight-year Program in Liberal Medical Education (PLME) or the five-year Brown-Rhode Island School of Design Dual Degree Program (BRDD), you must also complete the special program essays.

Three essays are required for all first year and transfer applicants:

- Brown's Open Curriculum allows students to explore broadly while also diving deeply into their academic pursuits. Tell us about any academic interests that excite you, and how you might pursue them at Brown. (200-250 words)

- Students entering Brown often find that making their home on College Hill naturally invites reflection on where they came from. Share how an aspect of your growing up has inspired or challenged you, and what unique contributions this might allow you to make to the Brown community. (200-250 words)

- Brown students care deeply about their work and the world around them. Students find contentment, satisfaction, and meaning in daily interactions and major discoveries. Whether big or small, mundane or spectacular, tell us about something that brings you joy. (200-250 words)

First year applicants are also asked to reflect briefly on each of the very short answer questions below. We expect that answers will range from a few words to a few sentences at most.

What three words best describe you? (3 words)

What is your most meaningful extracurricular commitment, and what would you like us to know about it? (100 words)

If you could teach a class on any one thing, whether academic or otherwise, what would it be? (100 words)

In one sentence, Why Brown? (50 words)

Transfer students are also asked to complete the following very short answer question:

Three essays are required for applicants to the PLME in addition to the three essays required of all first year applicants:

- Committing to a future career as a physician while in high school requires careful consideration and self-reflection. Explain your personal motivation to pursue a career in medicine. (250 word limit)

- Healthcare is constantly changing as it is affected by racial and social inequities, economics, politics, technology and more. Imagine that you are a physician and describe one way in which you would seek to make a positive impact in today’s healthcare environment. (250 word limit)

- How do you envision the Program in Liberal Medical Education (PLME) helping to meet your academic, personal and professional goals as a person and future physician? (250 word limit)

One essay is required for applicants to the Brown|RISD Dual Degree Program in addition to the three essays required of all first year applicants:

- The Brown|RISD Dual Degree Program draws on the complementary strengths of Brown University and Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) to provide students with the opportunity to explore and engage with diverse spheres of academic and creative inquiry. The culmination of students’ five-year program is a capstone project that relates and integrates content, approaches, and methods from two distinct learning experiences. Considering your understanding of the academic programs at Brown and RISD, describe how and why the specific blend of RISD's experimental, immersive combined studio and liberal arts program and Brown's wide-ranging courses and curricula could constitute an optimal undergraduate education for you. Additionally, how might your academic, artistic and personal experiences contribute to the Dual Degree community and its commitment to interdisciplinary work? (650 word limit)

Submitting Material

Within the Common Application, you will be presented with either online or paper methods of inviting appropriate school officials and teachers to supply records and recommendations. We suggest that you begin the process early to give them plenty of time to respond before the deadline.

We recommend having all official documents, including transcripts and recommendations, sent through the Common Application. Brown has also partnered with slate.org , through which counselors may upload materials directly for applicants. If this is not an option, please arrange to have your materials sent by email to [email protected] . In the absence of other electronic submission options, items may be faxed to 401-863-9300. Please do not mail duplicate hard copies of items that have been sent to Brown, as this can slow processing times.

Application Fee

To apply to Brown you must submit a $75 non-refundable application fee, or a fee waiver. As part of our commitment to make a Brown University education accessible to students from all income backgrounds, Brown is making automatic application fee waivers available to more students.

Brown will automatically waive the application fee for any student who is enrolled in or eligible for the Federal Free or Reduced Price Lunch program (FRPL), as well as students who are enrolled in federal, state or local programs that aid students from low-income families (for example, TRIO Programs). Additionally, Brown will automatically waive the application fee for any student who belongs to a community-based organization or college access organization that promotes educational opportunity for low-income students.

Applicants to Brown who meet any of these requirements should select the "Brown Specific Fee Waiver" in the "Brown Questions" section of the Common Application. Applicants who do not meet these specific requirements but believe they may qualify for a fee waiver may select the same options in the Common Application supplemented by a fee waiver request. We will accept fee waiver request forms from College Board or NACAC , or school counselors may email a letter of support directly to [email protected] .

Criminal History

We do not consider information on criminal history during our initial round of admission application review. Only upon selecting a pool of admitted candidates do we learn whether you have reported a criminal history, at which point we will offer you an opportunity to explain the circumstances. With this approach, information on misdemeanor or felony convictions can inform, but not determine, admission decisions. This ensures that applicants are evaluated based on their academic profile, extracurricular pursuits and potential fit - not criminal history - and enables us to continue to review this potentially important information.

Deadlines and Notifications

Complete the Common Application by:

- November 1 for Early Decision

- January 3 for Regular Decision

You will receive a confirmation email from the Office of College Admission confirming receipt of your Common Application. It is best to ensure that all application materials are sent by the deadline. However, if your application and application payment/fee waiver are submitted by the deadline, it is acceptable to have some of your supporting materials (transcripts, letters of recommendation, etc.) arrive within the following week.

Q for Questions

John brown questions and answers isc class 11 and class 12, short questions, part – 1.

(a) In what way does John Brown become a victim of so-called glorious war? Discuss with close reference to the text.

Answer : There are many persons who regard war as something glorious and those who fight it as heroes. They believe that war may be destructive but it is essential to finish the enemy. Wars, in their eyes, are never obsolete.

In the poem ‘John Brown’ the poet shows how young soldiers like John Brown are nurtured on the illusion of heroism in fighting the war. John Brown’s mother takes pride in false sense of heroism and encourages her son to join the army, fight bravely and win medals. So John Brown is soon enamoured of military glory. He joins the army leaves for the battlefield. His mother, seeing him in the uniform, enflames his fervour for heroism.

Oh, son , you look so fine, I’m glad you’re a son of mine You make me proud to know you hold a gun Do what the captain says, lots of medals you will get…….

Thus, John Brown inspired by heroic ideals goes to the front. He obeys his mother and tries to fulfil her ambition. When he returns home, his mother goes to the railway station to receive her son. She fails to recognise him. How can he be his son? In place of a young, dashing handsome young man, he is a cripple with badly disfigured face. Brown is now a totally helpless creature. He has lost his eyes and one of his hands. He wears a metal brace which provides him support to stand erect. He can hardly open his jaw. What he speaks is so low that it is mostly incomprehensible.

In this way, the poet shows how John Brown becomes a victim of the so-called glorious war.

(b) What do you think of John Brown’s mother?

Answer : John Brown’s mother is quite ignorant about the horrors of war. Like many other people, she is under the illusion that wars are glorious and soldiers are real heroes. That is why, she wants her son to become a soldier. She wants him to be a good soldier who fights for the sake of his country. Her desire is to see his medals of victory won by him during the war. She is oblivious of the horrible side of war.

Never does she ever think that her son may have to lose his life or precious limbs. When her son is about to leave for the battle front, she makes it a point to make her neighbours know that her son has become a soldier and is going to war. Her over-enthusiasm is vivid. However, when her son returns as a hopeless cripple she is shocked. She is far from happy on seeing the medals dropped on her hand by her disgruntled son. Thus, she is shown as the representative of all those who falsely glorify war.

(c) What experience of war does John Brown relate to his mother?

Answer : On returning from the war front in pathetic condition, John Brown tells his mother is a low voice his experience of war. He reminds his mother how she thought that the best thing that had happened was his going to the war. He says she felt proud of him as he was fighting. He wishes she should have been in his place.

The son continues to speak. He says that he wondered what he was doing in the war, trying to kill someone or die doing so. What frightened him the most was when the enemy soldier stood in front of him. He saw that his face resembled his .There was no difference at all.

In the midst of explosive sounds of shells bursting and stink from the dead bodies he realized that he was just a puppet in a play. He had no will of his own. Through the roaring sound and smoke a cannonball took his eyes away.

The son, while turning to go away, calls his mother to come close. As she comes nearer he quietly drops the medals he has won into her hand. It is the most pathetic moment in the poem.

Part – 2

(a) ‘John Brown’ underlies the idea that soldiers are mere puppets in the horrible show of any war. Discuss.

Answer : John Brown is a young soldier. He is encouraged by his mother to become a soldier and go the the battle field. She wants him to prove his heroism and win medals. She believes that soldiers are true heroes. Sadly, she in unaware of the horrors of war. She comes to realise the destructive side of war only when her soldier-son returns home in a miserable condition. He has lost his eyes and one of his hands. He has to wear a metal brace around his waist to support himself. His jaws do not open easily. When he speaks he speaks so low that it becomes difficult to understand what he speaks.

On being being asked by his mother what happened to him in the war, John Brown remind her that when he was going to the war it was she who thought that it was the best thing that he could do. He was fighting while she was at home, pretending to be proud of the fact since she was not in his place. On the battlefield, he soon realized the meaninglessness of war. He called upon God and asked himself what he was doing there. He was trying to kill someone. When an enemy soldier came face to face before him, he was shocked and puzzled. The enemy soldier had clear resemblance with him. His face looked like his. He could not think of killing him. At that time he could not help thinking in the midst of continuous gun-roar and stink that he was just a puppet in the show. He was being manipulated by others. He was fighting without knowing any reason. This realisation was quite saddening. Thus the poem ‘John Brown’ reveals that ordinary soldiers are just pawns in the hands of others. They are made to fight in the name of patriotism, nationalism, democracy, so and so forth. Sometimes they wonder what they are fighting for.

(b) In what way does the poem reveal irony of life?

Answer : Irony refers to the gap between what we assume and what happens in reality. This is the great irony of life that what happens is often contradictory to our expectations . In the poem ‘John Brown’ the young soldier John Brown’s mother has high hopes of her son’s heroic capabilities She wants him to join the army, fight for the glory of the country and win medals for heroism on the battlefront. When her son is about to go to war she tells every neighbour that her son is going to the battlefield. When her son is fighting, she continues to brag about his valorous acts.

However, she is stunned when her son returns as a cripple. He has lot his eyes and one of his hands. His jaws hardly open. What he speaks is in whispers. As he turns away, he drops his medals on the palm of his mother. This act is ironic and pathetic. The irony of fate is that he has won a lot of medals but has to pay a heavy price for them.

(c) ‘John Brown’ is a modern ballad. Comment.

Answer : ‘John Brown’ is a ballad and embodies many features of the traditional ballad, but in its construction it is modern. It is episodic and is set in no specific time and place. It has twelve verses. Each verse has a quatrain, but there is no set rhyme scheme which makes it modern in style. In some stanzas rhyming words are used, as in stanza 8 (‘way’: ‘away’), stanza 11(‘play’ : ‘away’) and stanza 12 (‘stand’ : ‘hand’). The rhyme varies with the mood, as in stanza 11:

“And I couldn’t help but think, through the thunder rolling and stink That I was just a puppet in a play And through the roar and smoke , this string is finally broke And a cannonball blew my eyes way.”

The subject matter of ‘John Brown’ is war, but its anti-war stance is against the spirit of the traditional ballad which often eulogies heroism related to war. Here a young man, John Brown, joins the army to the pride of his mother. He goes off to war to fight. But he soon loses his fervour. He realizes that war is futile. Even then he fights. His encounter with the enemy-soldier makes him realize the common bond of humanity with him. When he returns home, he is a changed man. His face is disfigured. He has lost his eyes and one of his hands. He wears a metal brae which enables him to stand erect. He cannot open his jaws. So his speech is incomprehensible. Thus, war turns a healthy, energetic young man into a cripple.

The ballad ends on an ironic note. John Brown puts his medals in the hand of his mother who is already in a shock. There medals are the sign of John Brown’s valour, but we wonder if they are any worth.

Long Questions

Question 1 : ‘John Brown’ by Bob Dylan debunks the belief in heroism surrounding war. Discuss with close reference to the text.

Answer : Most of the people have romantic notions about war. They believe that wars must be fought. It is during the war that ones proves one’s valour and heroic spirits which get the approval of everyone. It is thought that a war hero is an honoured and revered person. Such views have been challenged by many writers. G.B.Shaw shatters the allusion about heroism in his play ‘Arms and the Man’.

‘John Brown’ by Dylan shows how the notion of romanticism surrounding war is false and hypocritical . John Brown is a handsome young man. It is his mother who wants to see her son in the military uniform. Like other young men of his age, Brown too is enamoured of military glory. So he joins the army and goes to the battlefield. His mother only enflames his fervour for heorism:

“Oh, son , you look fine, I’m glad you’re a son of mine You make me proud to know you hold a gun Do what the captain says, lots of medals you will get……”

John Brown’s experience of war, however, dampens his heroic spirits. He soon realizes that he is used as a mere puppet for someone to fight for them. His control is in somebody else’s hand. Even he is unaware of the purpose behind the war. When he finds an enemy before him he finds his face like his own. He must have pictured in his mind the horrible picture of enemy soldiers. He is puzzled as to why he should kill a man who seems to be very much like him.

At last, when John Brown returns home, his mother goes to the railway station to receive his son. When she sees him, she fails to recognise his face. His face is badly disfigured. He has lost his eyes and one of his hands. He wears a metal brace which enables him to stand erect . He can hardly open his jaw. What he speaks is so low that it is mostly incomprehensible.

John Brown puts the medal he has won into the hand of his shocked mother. Thus, the poet seems to shatter the romantic illusion of heroism and machismo surrounding war.

Question 2 : ‘John Brown’ is a modern ballad. Discuss it with close reference to the text.

Answer : A ballad is a story in verse. It was originally intended to be sung to an audience. Its subjects have mostly been deeds of the simplest kind – a memorable feud, a thrilling adventure, a family disaster, love, war, and the like. The traditional ballad was written in the Ballad Measure using quatrains with a variable metre. A ballad opens in a dramatic way, introduces the subject and builds up the suspense which is kept towards the end. The end often provides a message, either directly or indirectly. Or it enriches us with a novel experience.

‘John Brown’ is a ballad and embodies many features of the traditional ballad, but in its construction it is modern. It is episodic and is set in no specific time and place. It has twelve verses. Each verse has a quatrain, but there is no set rhyme scheme which makes it modern in style. In some stanzas rhyming words are used, as in stanza 8 (‘way’ : ‘away’), stanza 11 (‘play’ : ‘away’) and stanza 12 (‘stand’ : ‘hand’). They rhythm varies with the mood, as in stanza 11:

“And I couldn’t help but think, through the thunder rolling and stink That I was just a puppet in a play And through the roar and smoke, this string is finally broke And a cannonball blew my eyes away.”