- Program Finder

- Admissions Services

- Course Directory

- Academic Calendar

- Hybrid Campus

- Lecture Series

- Convocation

- Strategy and Development

- Implementation and Impact

- Integrity and Oversight

- In the School

- In the Field

- In Baltimore

- Resources for Practitioners

- Articles & News Releases

- In The News

- Statements & Announcements

- At a Glance

- Student Life

- Strategic Priorities

- Inclusion, Diversity, Anti-Racism, and Equity (IDARE)

- What is Public Health?

Is the Hygiene Hypothesis True?

Did Covid shutdowns stunt kids' immune systems?

Caitlin Rivers

The hygiene hypothesis is the idea that kids need to be exposed to germs in order to develop healthy immune systems. We know that many common viruses did not circulate as widely during the pandemic, thanks to social distancing, masking, and other COVID mitigation measures. Are there downsides to those missed infections?

In this Q&A, Caitlin Rivers speaks with Marsha Wills-Karp, PhD, MHS , professor and chair of Environmental Health and Engineering , about the role of household microbiomes, birth, and vaccines in the development of kids’ immune systems—and whether early exposure really is the best medicine.

This Q&A is adapted from Rivers’ Substack blog, Force of Infection .

I think there’s some concern among parents who have heard about the hygiene hypothesis that there is a downside to all those stuffy noses that didn’t happen [during the COVID-19 pandemic]. Are there any upsides to viral infections? Do they help the immune system in some meaningful way?

I don’t think so.

You mentioned the hygiene hypothesis, which was postulated back in the ‘80s. German scientists noticed that families with fewer children tended to have more allergic disease. This was interpreted [to mean] that allergic disease was linked to experiencing fewer infections. I have explored this idea in my research for a couple of decades now.

This phenomenon has helped us to understand the immune system, but our interpretation of it has grown and expanded—particularly with respect to viruses. Almost no virus is protective against allergic disease or other immune diseases. In fact, infections with viruses mostly either contribute to the development of those diseases or worsen them.

The opposite is true of bacteria. There are good bacteria and there are bad bacteria. The good bacteria we call commensals . Our bodies actually have more bacterial cells than human cells. What we’ve learned over the years is that the association with family life and the environment probably has more to do with the microbiome. So one thing I would say is sanitizing every surface in your home to an extreme is probably not a good thing. Our research team showed in animals that sterile environments don’t allow the immune system to develop at all. We don’t want that.

What does contribute to the development of the immune system, if not exposure to viruses?

There are a number of factors that we’ve associated with the hygiene hypothesis over the last 20 years, and these exposures start very early in life. Cesarean sections, which do not allow the baby to travel through the birth canal and get exposed to the mother’s really healthy bacterial content, is a risk factor for many different immune diseases. Getting that early seeding with good bacteria is critical for setting up the child going forward. Breastfeeding also contributes to the development of a healthy immune system.

There are other factors. Our diets have changed dramatically over the years. We eat a lot of processed food that doesn’t have the normal components of a healthy microbiome, like fiber. These healthy bacteria in our gut need that fiber to maintain themselves. They not only are important for our immune system but they’re absolutely critical to us deriving calories and nutrients from our food. All these things contribute to a healthy child.

We’ve also noticed that people who live on farms have fewer of these diseases because they’re exposed to—for lack of a better term—the fecal material of animals. And what we have found is that it’s due to these commensal bacteria. That is one of the components that help us keep a healthy immune system. Most of us will probably not adopt farm life. But we can have a pet, we can have a dog.

I think all the pet lovers out there will be pleased to hear that.

There’s a lot of evidence that owning a pet in early childhood is very protective.

What about the idea that you need to be exposed to viruses in early life because if you get them as an adult, you’ll get more severely ill? We know that’s true for chickenpox, for example. Do you have any concerns about that?

We should rely on vaccines for those exposures because we can never predict who is going to be susceptible to severe illness, even in early childhood. If we look back before vaccines, children under 4 often succumbed to infections. I don’t think we want to return to that time in history.

Let me just give you one example. There’s a virus called RSV, it’s a respiratory virus. Almost all infants are positive for it by the age of 2. But those who get severe disease are more likely to develop allergic disease and other problems. So this idea that we must become infected with a pathogenic virus to be healthy is not a good one.

Even rhinovirus, which is the common cold, most people recover fine. But there’s a lot of evidence that for somebody who is allergic, rhinovirus exposures make them much worse. In fact, most allergic or asthmatic kids suffer through the winter months when these viruses are more common.

And that’s particularly salient because there is a lot of rhinovirus and enterovirus circulating right now.

From my point of view, right now, avoiding flu and COVID-19 is a priority. Those are not going to help you develop a healthy immune response, and in fact, they can do a lot of damage to the lungs during that critical developmental time. Data [show] that children that have more infections in the first 6 months to a year of life go on to have more problems.

It’s always surprising to me when I look at the data of the fraction of time that young children spend with these common colds—and this is pre-pandemic—it’s not uncommon for kids to be sick 50% of the time. That feels right as a parent, but it’s startling.

The other thing people don’t know is that the GI tract is where you get tolerized to all of your foods, allergens and things. Without those healthy bacteria in your gut, you can’t tolerate common allergens.

How does that relate to the guidance that’s changed over the years—that you should withhold peanuts in early life and now you’re supposed to offer them in early life?

The guidance to delay exposure to peanuts didn’t consider the fact that oral exposure to peanuts was not the only exposure kids were getting. There were peanut oils in all kinds of skin creams and other things. So kids got exposed through their skin, but they had no gut protection—and the GI tract is important for a tolerant system. If you have a healthy immune response, you get tolerized in early life.

This concept is a little bit different for those families who may already have a predisposition to allergies. But for the general public, exposure is key to protecting them in early life.

I think some parents look at the guidance that you should now offer peanuts in early life and say, “Are we not doing that with rhinovirus by masking kids or improving ventilation?” How should people think about the development of the immune system for food allergies compared to infections?

The thing about rhinoviruses is that after recovering, you’re not protected from the next infection. There is no real immune protection there. Most of us suffer from colds throughout our whole life. Like I said, bacterial exposure is what’s key to priming the immune response.

Also, we forget that a lot of kids die from the flu. Unlike COVID-19, where younger kids are not quite as susceptible to severe illness, that’s not true for flu. RSV, too, can be quite severe in young children and older adults.

Caitlin Rivers, PhD, MPH , is a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security and an assistant professor in Environmental Health and Engineering at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

- Study Finds That Children’s Antibody Responses to COVID-19 Are Stronger Than Adults’

- Back to School: COVID, CDC Guidance, Monkeypox, and More

- A New Shot Prevents Serious Illness from RSV

Related Content

Outbreak Preparedness for All

The Public Health Strategy Behind Baltimore’s Record-Low Infant Mortality Rate

What’s Happening With Dairy Cows and Bird Flu

Decisive Action Needed to Stop Cervical Cancer Deaths

How Dangerous is Dengue?

What Is the Hygiene Hypothesis?

Many parents believe that their children must be kept in an environment that is as clean as possible, but some research suggests that being exposed to what many would call unclean conditions is good for a child's immune system. Research has indicated that children who are kept in very clean environments have a higher rate of hay fever, asthma and a wide range of other conditions. This is what is called the hygiene hypothesis.

The hygiene hypothesis was first introduced in the late 1980s by David P. Strachan, a professor of epidemiology, in the British Medical Journal. Strachan found that children in larger households had fewer instances of hay fever because they are exposed to germs by older siblings. This finding led to further research that suggests a lack of early childhood exposure to less than pristine conditions can increase the individual's susceptibility to disease.

For example, in the late 1990s, Dr. Erika von Mutius, a health researcher, compared the rates of allergies and asthma in East Germany and West Germany, which unified in 1999. Her initial hypothesis was that East German children, who grew up in dirtier and generally less healthful conditions, would have more allergies and suffer more from asthma than their Western counterparts. However, her research found the opposite: children in the polluted areas of East Germany had lower allergic reactions and fewer cases of asthma than children in West Germany.

Further research has found that children in developing areas of the world are less likely to develop allergies and asthma compared with children in the developed world.

Building the immune system

The idea is simple. When babies are inside the womb they have a very weak immune system because they are given protection by their mother's antibodies. When they exit the womb, though, the immune system must start working for itself. For the immune system to work properly, it is thought that the child must be exposed to germs so that it has a chance to strengthen, according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

The idea is similar to the training of a body builder. For a body builder to be able to lift heavy objects, the muscles must be trained by lifting heavier and heavier objects. If the body builder never trains, then he will be unable to lift a heavy object when asked. The same is thought to be true for the immune system. In able to fight off infection, the immune system must train by fighting off contaminants found in everyday life. Systems that aren't exposed to contaminants have trouble with the heavy lifting of fighting off infections.

Mutius hypothesized that the reason children who are not exposed to germs and bacteria are sicklier is due to how the human immune system evolved. She thinks there are two types of biological defenses. If one of the defense systems isn't trained or practiced enough to fight off illness, the other system overcompensates and creates an allergic reaction to harmless substances like pollen.

Research by other scientists has found similar results. Exposure to germs triggered an internal inflammatory response in children who were raised in cleaner environments, leading to ailments such as asthma, according to a 2002 article in Science magazine.

One researcher has personal experience has leads him to back the hygiene hypothesis. "I believe that there is a role in the development of a child's immunity exposure to various germs and a vast microbiome diversity," said Dr. Niket Sonpal, an assistant professor of clinical medicine at Touro College of Osteopathic Medicine, Harlem Campus. "I was born in India but moved to the U.S. and went to college in Virginia and medical school in Europe. I am sure that the vast change in environment has played a role in my immunity. How has it? I don't think we know just yet."

In 1997, some began to question if there is a correlation between the hygiene hypothesis and vaccinations. The number of children getting vaccinations was going up, but so were the number of children afflicted with allergies, eczema and other problems. Could depriving the developing immune system of infections using vaccines cause the immune system to eventually attack itself and cause autoimmune diseases like asthma and diabetes? This is a highly contested issue.

Three studies conducted in the 1990s showed that vaccines had no correlation with children developing allergies and other ailments later in life. In fact, vaccinations may help prevent asthma and other health problems other than the diseases they were intended to prevent, according to The National Center for Immunization Research and Surveillance . The idea that vaccinations can cause health problems does not consider the fact that children, whether vaccinated or not, are still exposed to pathogens that help build the immune system. These pathogens also have no relation to the diseases that the vaccines prevent.

The conflict between cleanliness and exposure can leave parents feeling confused. There are many microbes that can make children very sick, such as such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), E.coli and salmonella. So cleaning the home is still very important. What should children be exposed to and what should they be protected from?

The CDC recommends regularly cleaning and disinfecting surfaces in the home, especially when surfaces have been contaminated by fecal matter or meat or have come in contact with those who have a virus. Children are also encouraged, though, to play outside , even if they may get dirty in the process. This balancing act may prove to help children stay healthy while still developing a healthy immune system.

Sonpal thinks that the healthy growth of the immune system isn't just about coming in contact with dirt. It also has to do with what foods are consumed, what kind of environments the person grows up in and intrinsic genetics coupled with physical activity levels. Harvard Medical School noted that getting plenty of sleep, avoiding cigarette smoke, drinking in moderation and controlling blood pressure also all play a part in a healthy immune system.

Additional Resources

- Clinical & Experimental Immunology: The 'Hygiene Hypothesis' for Autoimmune and Allergic Diseases: An Update

- Mayo Clinic: Early germ exposure prevents asthma?

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: The Hygiene Hypothesis and home hygiene

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

'Vampire' bacteria thirst for human blood — and cause deadly infections as they feed

Scientists uncover the cells that save you when water goes down the wrong pipe

'Unprecedented' discovery of mysterious circular monument near 2 necropolises found in France

Most Popular

- 2 'Gambling with your life': Experts weigh in on dangers of the Wim Hof method

- 3 'Exceptional' prosthesis of gold, silver and wool helped 18th-century man live with cleft palate

- 4 NASA spacecraft snaps mysterious 'surfboard' orbiting the moon. What is it?

- 5 AI pinpoints where psychosis originates in the brain

- 2 2,500-year-old skeletons with legs chopped off may be elites who received 'cruel' punishment in ancient China

- 3 Modern Japanese people arose from 3 ancestral groups, 1 of them unknown, DNA study suggests

- 4 Giant, 82-foot lizard fish discovered on UK beach could be largest marine reptile ever found

- 5 The universe may be dominated by particles that break causality and move faster than light, new paper suggests

- Skip to main content

- Skip to FDA Search

- Skip to in this section menu

- Skip to footer links

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- Search

- Menu

- Vaccines, Blood & Biologics

- Resources for You (Biologics)

- Consumers (Biologics)

Asthma: The Hygiene Hypothesis

What do clean houses have in common with childhood infections.

One of the many explanations for asthma being the most common chronic disease in the developed world is the “hygiene hypothesis.” This hypothesis suggests that the critical post-natal period of immune response is derailed by the extremely clean household environments often found in the developed world. In other words, the young child’s environment can be “too clean” to pose an effective challenge to a maturing immune system.

According to the “hygiene hypothesis,” the problem with extremely clean environments is that they fail to provide the necessary exposure to germs required to “educate” the immune system so it can learn to launch its defense responses to infectious organisms. Instead, its defense responses end up being so inadequate that they actually contribute to the development of asthma.

Scientists based this hypothesis in part on the observation that, before birth, the fetal immune system’s “default setting” is suppressed to prevent it from rejecting maternal tissue. Such a low default setting is necessary before birth—when the mother is providing the fetus with her own antibodies. But in the period immediately after birth the child’s own immune system must take over and learn how to fend for itself.

The “hygiene hypothesis” is supported by epidemiologic studies demonstrating that allergic diseases and asthma are more likely to occur when the incidence and levels of endotoxin (bacterial lipopolysaccharide, or LPS) in the home are low. LPS is a bacterial molecule that stimulates and educates the immune system by triggering signals through a molecular “switch” called TLR4, which is found on certain immune system cells.

The science behind the hygiene hypothesis

The Inflammatory Mechanisms Section of the Laboratory of Immunobiochemistry is working to better understand the hygiene hypothesis, by looking at the relationship between respiratory viruses and allergic diseases and asthma, and by studying the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in particular.

What does RSV have to do with the hygiene hypothesis?

- RSV is often the first viral pathogen encountered by infants.

- RSV pneumonia puts infants at higher risk for developing childhood asthma. (Although children may outgrow this type of asthma, it can account for clinic visits and missed school days.)

- RSV carries a molecule on its surface called the F protein, which flips the same immune system “switch” (TLR4) as do bacterial endotoxins.

It may seem obvious that, since both the RSV F protein and LPS signal through the same TLR4 “switch,” they both would educate the infant’s immune system in the same beneficial way. But that may not be the case.

The large population of bacteria that normally lives inside humans educates the growing immune system to respond using the TLR4 switch. When this education is lacking or weak, the response to RSV by some critical cells in the immune system’s defense against infections—called “T-cells”—might inadvertently trigger asthma instead of protecting the infant and clearing the infection. How this happens is a mystery that we are trying to solve.

In order to determine RSV’s role in triggering asthma, our laboratory studied how RSV blocks T-cell proliferation.

Studying the effect of RSV on T-cells in the laboratory, however, has been very difficult. That’s because when RSV is put into the same culture as T-cells, it blocks them from multiplying as they would naturally do when they are stimulated. To get past this problem, most researchers kill RSV with ultraviolet light before adding the virus to T-cell cultures. However we did not have the option of killing the RSV because that would have prevented us from determining the virus’s role in triggering asthma.

Our first major discovery was that RSV causes the release from certain immune system cells of signaling molecules called Type I and Type III interferons that can suppress T-cell proliferation (Journal of Virology 80:5032-5040; 2006).

The hygiene hypothesis suggests that a newborn baby’s immune system must be educated so it will function properly during infancy and the rest of life. One of the key elements of this education is a switch on T cells called TLR4. The bacterial protein LPS normally plays a key role by flipping that switch into the “on” position.

Prior research suggested that since RSV flips the TLR4 switch, RSV should “educate” the child’s immune system to defend against infections just like LPS does.

But it turns out that RSV does not flip the TLR switch in the same way as LPS. This difference in switching on TLR, combined with other characteristics of RSV, can prevent proper education of the immune system.

One difference in the way that RSV flips the TLR4 switch may be through the release of interferons, which suppresses the proliferation of T-cells. We still do not know whether these interferons are part of the reason the immune system is not properly educated or simply an indicator of the problem. Therefore, we plan to continue our studies about how RSV can contribute to the development of asthma according to the hygiene hypothesis.

Further research

This finding that Type I and Type III interferons can mediate the suppression of T-cells caused by RSV generated two significant questions that our laboratory is now addressing:

- Interferons are important molecules that enhance inflammation, so why--in the context of RSV--do they suppress T-cells?

- Interferons are clearly not the only way RSV suppresses T-cells. What are the other mechanisms that may depend upon T-cells coming in direct contact and communicating with other immune cells?

Related Research

- Assessing the Mechanism of Immunotherapy for Allergy and Allergic Asthma: Effect of Viral Respiratory Infections on Pathogenesis and Clinical Course of Asthma and Allergy Ronald Rabin, MD

MINI REVIEW article

The hygiene hypothesis and new perspectives—current challenges meeting an old postulate.

- 1 Translational Inflammation Research Division & Core Facility for Single Cell Multiomics, Medical Faculty, Biochemical Pharmacological Center (BPC), Philipps University of Marburg, Marburg, Germany

- 2 German Center for Lung Research (DZL), Marburg, Germany

- 3 Comprehensive Biobank Marburg (CBBMR), Medical Faculty, Philipps University of Marburg, Marburg, Germany

- 4 German Biobank Alliance (GBA), Marburg, Germany

During its 30 years history, the Hygiene Hypothesis has shown itself to be adaptable whenever it has been challenged by new scientific developments and this is a still a continuously ongoing process. In this regard, the mini review aims to discuss some selected new developments in relation to their impact on further fine-tuning and expansion of the Hygiene Hypothesis. This will include the role of recently discovered classes of innate and adaptive immune cells that challenges the old Th1/Th2 paradigm, the applicability of the Hygiene Hypothesis to newly identified allergy/asthma phenotypes with diverse underlying pathomechanistic endotypes, and the increasing knowledge derived from epigenetic studies that leads to better understanding of mechanisms involved in the translation of environmental impacts on biological systems. Further, we discuss in brief the expansion of the Hygiene Hypothesis to other disease areas like psychiatric disorders and cancer and conclude that the continuously developing Hygiene Hypothesis may provide a more generalized explanation for health burden in highly industrialized countries also relation to global changes.

Introduction

Throughout its history, the Hygiene Hypothesis has shown itself to be adaptable and flexible whenever it has been challenged by innovation in science ( 1 ). A number of new findings need to be considered in this ongoing revisiting process: The originally proposed Th1/Th2 paradigm is challenged by currently elucidated new classes of effector and regulating immune cells pointing out to a more complex immune network involved in allergy development ( 2 ). Studies on biomarkers and deep phenotyping techniques changed our understanding of asthma as a uniform disease in favor of distinct phenotypes that are driven by different causations ( 3 ). The emerging field of epigenetics enables us to fill the black box of “gene-by-environment interactions” with conveying mechanisms ( 4 ). Currently recognized epigenetic pathways overlapping between chronic inflammatory diseases and other disorders such as psychiatric conditions or cancer might extend the Hygiene Hypothesis toward a model explaining in a broader sense the rise of health burdens in westernized societies ( 5 ). Finally, the world-wide challenge caused by the climate changes will not leave the consequences of Hygiene Hypothesis unaffected. Changing life-styles are closely related to measures implemented to slow down CO 2 emissions and to stabilize the world climate ( 6 ).

Challenges From Immunology – The Immune System Becomes More Complex

Parallel to the revisions that Hygiene Hypothesis has undergone over time ( 7 ), our perception of the mechanisms underlying cellular and humoral immune responses has changed fundamentally over the last decades. High-resolution flow cytometry and cell sorting and, most recently, single cell multiomics-based analyses provided a deeper insight into the phenotypic characterization, function, and development of diverse classes of hematopoietic cell types. The dichotomous model of divergent Th1 and Th2 responses was significantly expanded by the discovery that T lymphocytes represent a branched network of subsets, characterized by a high level of plasticity and adaptability ( 8 ). Namely, Sakaguchi’s discovery of regulatory T-cell (Treg) subsets provided a significant new impetus to researchers investigating the immunological origin of allergic and autoimmune diseases and their prevention under healthy conditions and pointed out new strategies to combat those maladies ( 9 , 10 ). Moreover, the discovery of new classes of effector cells and their cellular interactions added relevant evidence to the field. As one example, innate lymphoid cells (ILC) became of main interest as they have been shown to be both directly and indirectly associated with and involved in the development of allergic responses ( 11 ). This unique class of effector cells lacks a clonally distributed antigen receptor which thus resemble innate immune cells characterized by (antigen) unspecific activation, however, they exert T helper (Th)-like effector cell activities ( 12 ). According to their expression of effector cytokines and transcription factors ILC have been classified into three groups: ILC1, ILC2, and ILC3 ( 13 ). While ILC1 produce interferon-gamma (IFNγ) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and, similarly to Th1 cells, express T-bet, ILC2 are able to produce Th2 cytokines such as IL-5 and IL-13, like Th2 cells under the control of the transcription factor GATA-3. ILC3 are similar to Th17 cells and release IL-17A and IL-22 as well as granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF). In animal models of allergic airway inflammation as well as in human allergic asthmatics ILC2 are present at elevated frequencies within the lung and airways epithelial compartments where they were found to produce high amounts of the type-2 cytokines IL-5 and IL-13 ( 14 ). Within the last years, ILC2 have been recognized as early promoters to establish and maintain allergic airway inflammatory responses but also as protectors promoting repair processes of the lung epithelium ( 15 , 16 ).

A potential link between the Hygiene Hypothesis and the function of ILC lineages comes from the gut. The symbiotic interaction between immune cells and the microbiota in the gut is principally decisive for the development of tolerance or pathogenicity. The ILC3 lineage is essential in the development of lymphoid follicles and Peyer’s patches in the gut and was shown to be crucial for the maintenance of a well-balanced symbiosis with the microbiota ( 17 ). The host microbiota itself might play an important role in determining ILC subsets specificity as indicated by results coming from experimental approaches. Sepahi et al. very recently reported that short chain fatty acids (SCFA) arising from dietary fibers by microbial fermentation in the intestine induced expansion of prevailing ILC subsets. By triggering ILC subset expansion via G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) those dietary metabolites contribute to the homeostasis in the local compartment ( 18 ). Another mechanism to induce repair and homeostatic conditions at epithelial surfaces is mediated via IL-22-producing ILC3 in response to the microbiota. In interaction with IL-18 produced by the epithelial cells, IL-22 is involved in the promotion of repair and remodeling processes as well as in the maintenance of the gut homeostasis ( 19 ). By acting as mediators between the microbiota and the host ILC are recognized as crucial in the early host response to microbial stimuli.

Challenges From Changing Environments – Can Epigenetics Provide the Missing Link to Explain “Gene-by-Environment Interactions”?

Very recently, damaging factors that jeopardize the normal development or disturb the balance of an established immune system have come into the focus of research on allergic diseases. Environmental changes caused by in- and outdoor pollution ( 20 , 21 ) and the global warming impact the atopic epidemic and some attempts were undertaken recently to integrate these scenarios into the concept of the Hygiene Hypothesis on the basis of epigenetic changes driven by gene-by-environment interactions ( 22 ).

In contrast to our ancestors who spent most of their life time outdoors and thus close to a natural environment, post-modern and mainly urban life-styles are characterized by a significantly higher proportion of indoor activities. These changing habits underline the potential importance of indoor air composition on the development of allergic diseases and further emphasize the role of the environmental microbiota ( 23 ). Indoor air in urban homes is often burdened with elevated levels of molds which are found to be harmful to the airways and favor the development of airway inflammation and asthma ( 24 ). Against the background of growing climate awareness and the resulting increased efforts to reduce energy consumption and CO 2 emissions, current research on these indoor exposures in homes with improved house insulation points out to an up-coming health problem. Enrichment of volatile organic compounds released from furniture or brought in by tobacco smoke as well perennial allergens and molds will jeopardize mainly infants as the developing immune system and the growing lung are highly susceptible to these damage factors ( 25 ). Already the fetus might become affected by these components ( 26 ). This was exemplarily shown for tobacco smoke in a transgenerational case control study conducted to assess the risk for asthma by prenatal smoking. Grandmothers and mothers of asthmatic and non-asthmatic children were asked about smoking habits during their own pregnancy. The study reported an odds ratio twice as high for children to develop asthma in families where grandmothers frequently smoked during the mother’s fetal period ( 27 ).

At that point the Hygiene Hypothesis was in line with an upcoming general idea that non-inherited/non communicable diseases like allergies and asthma develop on the background of an inappropriate interaction between environmental exposures and a given genotype to shape a specific (disease) phenotype. Though based on the concept of a so-called epigenetic landscape postulated by Waddington already in the 50ties of the last century, the underlying molecular mechanisms of epigenetic programming had still been the “missing link” in the scenario of gene-by-environment-interactions ( 28 ). By discovering mechanisms such as DNA methylation, diverse histone modifications and microRNA regulation as molecular mechanisms underlying epigenetic regulation of gene expression, an exciting new field of research was opened that currently has a strong impact on research aiming to unravel the still existing mysteries of allergy development and prevention ( 29 – 31 ).

Indeed, epigenetic mechanisms have meanwhile clearly been demonstrated to be involved in mediating the effects of environmental factors increasing or decreasing the risk of allergy development ( 4 ). Pro-allergic environmental influences can be exemplified by pollution. For instance, higher in utero exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) has been shown to be associated with increased cord blood leukocyte DNA methylation at the promoter of the IFNγ-encoding gene ( 32 , 33 ). Moreover, in Treg isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells, higher PAH exposure has been correlated with elevated DNA methylation at the promoter of the gene encoding FOXP3, a master regulator of Treg development and activities, with the effect being stronger in asthmatic than in non-asthmatic children ( 34 ).

After epidemiological studies had demonstrated an association between spending early life time in specific agricultural environments and protection against the development of allergies in childhood ( 35 , 36 ), functional investigations of various types started to clarify which elements of farming, such as contact with farm animals, consumption of raw cow’s milk, exposure to so-called farm-dust, and others, mechanistically underlie this observation. DNA demethylation at the FOXP3-encoding locus related to higher expression of the gene and activation of Treg ( 37 ) has been associated in cord blood with maternal consumption of raw cow’s milk ( 38 ) and in children’s whole blood with early-life ingestion of raw cow’s milk ( 39 ). Compared to processed shop milk, pretreatment with raw cow’s milk reduced features of the disease in mice subjected to a model of food allergy and this effect was mediated by changes in histone acetylation patterns at crucial T cell-related genes ( 40 , 41 ). Interestingly enough, unprocessed cow’s milk has been shown to contain miRNAs potentially affecting the expression of important allergy-related immune genes, which might contribute to its protective effects against asthma ( 42 ). Several bacteria have been isolated from the farming environment, for instance Acinetobacter lwoffii ( A. lwoffii ), which were demonstrated to diminish the development of allergic symptoms in murine models ( 43 ). A. lwoffii -mediated protection against allergic airway inflammation has been observed in mouse models also transmaternally and shown to be IFNγ−dependent, with this effect being at least partly mediated by preservation of histone H4 acetylation at the promoter of the IFNγ-encoding gene as observed in CD4 + T cells isolated from spleens of the offspring ( 44 , 45 ).

Challenges From the Clinics and Lessons From Animal Models – Asthma Phenotypes and the Hygiene Hypothesis

A recurrent debate flared up in the field of asthma research excellently summarized at the time being in a review by Wenzel in 2012 ( 46 ). Coming from clinical heterogeneity of asthma patients she highlighted that basic inflammation patterns differ in asthma patients which in turn determines the success of the applied therapeutic strategy. As an early diagnosis and adequate treatment may prevent the development of a severe asthma phenotype later on, novel strategies to discriminate children at risk from those who will not develop asthma are required ( 47 ). Following the clinical definition of a phenotype as a result of an interaction between a given genotype and the environment Wenzel and colleagues expressed the strong medical need for novel molecular and genetic biomarkers indicative for the characterization of such phenotypes and defining the specific requirements for stratified therapies. Based on differences between Th2-driven atopic asthma and non-atopic asthma a number of subtypes were defined that evolve and differ with age and respond differentially to standard drug treatment regimes. It quickly became clear that the search for a specific biomarker that clearly identifies a respective phenotype would not be successful. Rather, the synopsis of all data collected from a subject known as “deep phenotyping” may lead to better understanding of complex asthmatic conditions ( 48 ). Deep phenotyping in the era of OMICS goes along with a tremendous increase in data that needs to be analyzed. To handle these big data-sets new approaches become increasingly employed involving models of statistical data dimension reduction and machine-learning strategies ( 49 , 50 ). The idea behind these data-driven approaches is to mine data collections and classify them based on so far hidden patterns behind the data. The hypothesis-free latent class analysis (LCA) approach represent one of the most promising tools to identify new or verify proposed asthma (and other allergic disease) phenotypes. A first LCA approach was carried out in two cohorts of adult asthmatics. Based on clinical and personal characteristics Siroux et al. described two distinct phenotypes in two independent cohorts, a severe phenotype in which asthma is already established in childhood and a second type that starts in adulthood with milder outcomes ( 51 ). In line with the Hygiene Hypothesis, these results pointed out specific preconditions in infant age which pave the pathway to severe asthma later in life. LCA analyses in children substantiated the link between early onset and later disease since early clinical signs such as current unremitting wheezing episodes are ascribed to indicate a higher risk for asthma development later in life while transient wheezing seems to have no pathological consequences ( 52 ).

LCA approaches using data from patient studies elucidated that there might be phenotypic asthmatic manifestations that could be explained by the Hygiene Hypothesis while other phenotypes that might have different pathomechanistic origins failed to be covered by this supposition ( 53 ). Among others, this discrepancy led to new approaches in pre-clinical animal-based experimental set-ups as well as investigations based on human data. New animal models were employed to prove the postulate of such phenotypes that can be discriminated on the immunological and histological levels. By switching from the well-established Ovalbumin (OVA) model, where the sensitization was mainly achieved by a rather artificial intraperitoneal allergen sensitization in the presence of the type-2 driving adjuvant alum, to a more flexible administration of standardized house dust mite extracts (HDM) via the nasal route, it was feasible to induce a more natural and broader spectrum of inflammatory phenotypes ranging from typical allergic eosinophil-dominated respiratory inflammation to airway inflammatory conditions almost exclusively dominated by the influx of neutrophils ( 54 – 56 ). Such more flexible model systems allow deeper and more precise investigations of the mechanisms underlying the development of different phenotypes and a much better characterization of the orchestration of different regulatory and effector T cell subsets in dependence of allergen administration on a continuum between Th2 and Th1/Th17-driven inflammation. In addition, these mouse models mimic the natural situation more closely by using common allergens and a potential natural route of sensitization and thus became helpful for understanding the diverse clinical phenotypes of allergic and non-allergic as well as mild and severe asthma ( 57 , 58 ). By switching between different effector T cell responses in these experimental set-ups substantial knowledge is currently added to our understanding of clinical manifestations in asthma. In combination with LCA helping to elucidate clinical phenotypes these recent research developments strongly boosted a better discrimination between transient and persistent pediatric allergic conditions as well as allergic and non-allergic asthma later in life. This new evidence might lead us to the current limits of the Hygiene Hypothesis. While IgE-driven allergic asthma undoubtedly fits to the Hygiene Hypothesis, it is still unclear whether this holds true also for non-atopic asthma phenotypes the development of which is much more strongly determined by factors different from a missing (microbial) education of the immune system. Thus and to further fine-tune the Hygiene Hypothesis, continuous efforts are required to distinguish between environmental conditions (such as early life infection with pathogenic viruses) that are either associated with the induction of a disease phenotype and/or just contribute to a shift between distinct inflammatory manifestations of allergic disease phenotypes ( 59 , 60 ) and those that really result in a general or a phenotype/endotype-specific prevention of disease in line with the Hygiene Hypothesis ( 43 , 61 ).

Challenges From a View Over the Fence – The Hygiene Hypothesis in Psychiatric Disorders and Cancer

The French scientist Bach was the first who made the principal observation of a general inverse correlation in the prevalences of infectious versus non-communicable chronic inflammatory diseases within the last seven decades ( 62 ). Meanwhile we know that abundant exposure to a high diversity of infectious or even harmless microbes resulting in repeated, low-grade acute inflammatory episodes in early life, associates with lower prevalence of chronic inflammatory disorders accompanied by low levels of inflammatory markers in adulthood. Conversely, high levels of hygiene during perinatal and early childhood developmental periods characteristic for Western countries corresponds to higher levels of inflammatory markers correlating with a higher prevalence of chronic inflammatory disorders later in life. Based on these facts, it has been hypothesized that frequent episodes of low-grade, in most cases clinically symptom-free inflammation in infancy may balance responses to inflammatory stimuli and thus reduce the rate of continuation of chronic inflammation into adulthood, most probably by adequately shaping the adaptive immunity-dependent regulation ( 23 ).

Interestingly, this observation considers a broader spectrum of chronic inflammatory conditions beyond allergies that might fit under the umbrella of the Hygiene Hypothesis such as multiple sclerosis, irritable bowel disease or diabetes type 1 ( 63 ). Moreover, within the last years a similar approach emerged to explain the tremendous increase in psychiatric disorders in westernized countries. Mainly affective disorders such as major depression and bipolar disorder are increasingly diagnosed in the westernized world. Patients suffering from affective and anxiety disorders depict an array of features that mirror inflammatory conditions such as pro-inflammatory cytokines in the blood and the central nervous system accompanied by elevated levels of circulating C-reactive protein (CRP), activation of lymphocytes and inflammatory cellular signaling pathways (MAPK and NF-κB), with the question of causality remaining a chicken or egg problem ( 64 ). Nevertheless, based on genetic predispositions and epigenetic modifications in the brain (nervous system) and the periphery (immune system), both kinds of pathologies, mood and inflammatory disorders, might become established on the basis of a disturbed homeostasis of otherwise tightly balanced adaptive systems of the body. Interestingly but fitting to the hypothesis, the microbiota of the gut seems to play a critical role also in the development of psychiatric disorders as shown by recently conducted studies ( 65 ). Based on an interplay between the gut and the central nervous system, persistent stress and maltreatment modifies the nervous system and thereby the endocrine hypothalamic pituitary axis (HPA) which in turn alters gut microbiota by cortisol release ( 66 ). Dysbiosis in the gut might lead to a compromised cytokine balance in the blood followed by an activation of the microglia in the brain after transfer of inflammatory mediators/cytokines through the blood-brain barrier ( 67 ). Further, degradation of beneficial bacteria in the gut microbiota might result in a loss of microbiota-derived products such as butyrate which directly results in the downregulation of γ-aminobutyrate, serotonin and dopamine, all factors directly involved in the neurological regulation circuits and thus in the genesis of neuropsychiatric disorders when dysregulated ( 68 ).

Finally, to add another example to this collection, there is increasing evidence that similar mechanisms as involved in the protection from allergies might also play a role in the prevention of oncologic diseases ( 69 ). There is no doubt that preceding infections with certain pathogens may favor initiation and further development of several tumor disease entities. However, a variety of recent studies also demonstrated positive effects of pathogen-induced “benign” inflammatory processes on cancer development, even though the underlying mechanisms of this dichotomous influence of microbial exposure-mediated immune modulation on carcinogenesis are not well understood so far ( 70 ). As one example, the origins of childhood leukemia have long been discussed in the context of microbial stimuli in early childhood. Already at the end of 20 th century the question emerged whether early infections in childhood may act protectively against childhood acute leukemia by eliminating expanding aberrant leukocyte clones through well-trained and established immune mechanisms. In concordance with the Hygiene Hypothesis, Greaves propagated the “Delayed Infection Hypothesis” as an explanation for the development of childhood acute (lymphoblastic/myeloid) leukemia (ALL/AML) that peaks at the age of 2-5 years of life in affluent countries ( 71 , 72 ). In his two hit model, Greaves proposed that based on a prenatally occurred chromosomal translocation or hyperdiploidy a pre-leukemic clone is already established around birth (first hit). A second hit event beyond the toddler age then leads to gene deletion or mutation and subsequent transformation to ALL/AML. While children suffering from infections and/or exposed to a rich microbial environment early in life might be ready to prevent that second aberration, predisposed children with an insufficiently educated immune system due to missing “old friends” contacts in the early postnatal life might not be able to eliminate expanding malignant cell clones ( 72 ). A number of studies aimed to prove this hypothesis by exploiting “day care attendance” before the third year of life as a proxy for infection. This concept is still a matter of debate. While the vast majority of these studies could add evidence to the Greaves hypothesis, some well-conducted studies could not support his assumptions ( 73 , 74 ). Recently, a meta-analysis investigated the farm effect with regard to childhood leukemia and confirmed that contact to livestock provides protection not only against allergies but also against childhood leukemia ( 75 ). This study might point out to microbiota as a crucial player in both prevention of allergies and childhood cancer.

The challenges outlined in this mini review are intended to stimulate further exciting debates that might result in continuing revisions and adaptations of the Hygiene Hypothesis. We are aware that the examples reported in this review may only describe a limited subjective selection of the scientific topics currently discussed in context of the Hygiene Hypothesis. However, it is common to all topics that the explanations to unravel the underlying mechanisms refer to the close and beneficial relationship between man and microbes as established on the mucosal surfaces of our body. These interactions result in adequate shaping of adaptive systems of the body (mainly the immune system) that enables the whole organisms to appropriately handle diverse adverse influences. Without exaggeration, this finding might be considered one of the most fundamental insights of the life sciences within the last thirty years.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed by writing and editing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funded by the German Center for Lung Research (DZL). Open Access was funded by the Library of the Philipps University Marburg, Germany.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Haahtela T. A biodiversity hypothesis. Allergy (2019) 74:1445–56. doi: 10.1111/all.13763

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Gelfand EW, Joetham A, Wang M, Takeda K, Schedel M. Spectrum of T-lymphocyte activities regulating allergic lung inflammation. Immunol Rev (2017) 278:63–86. doi: 10.1111/imr.12561

3. Breiteneder H, Peng Y-Q, Agache I, Diamant Z, Eiwegger T, Fokkens WJ, et al. Biomarkers for diagnosis and prediction of therapy responses in allergic diseases and asthma. Allergy (2020) 75:3039–68. doi: 10.1111/all.14582

4. Alashkar Alhamwe B, Miethe S, Pogge von Strandmann E, Potaczek DP, Garn H. Epigenetic Regulation of Airway Epithelium Immune Functions in Asthma. Front Immunol (2020) 11:1747. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01747

5. Langie SA, Timms JA, de Boever P, McKay JA. DNA methylation and the hygiene hypothesis: connecting respiratory allergy and childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Epigenomics (2019) 11:1519–37. doi: 10.2217/epi-2019-0052

6. D’Amato G, Akdis CA. Global warming, climate change, air pollution and allergies. Allergy (2020) 75:2158–60. doi: 10.1111/all.14527

7. Liu AH. Revisiting the hygiene hypothesis for allergy and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2015) 136:860–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.08.012

8. Zhu J. T Helper Cell Differentiation, Heterogeneity, and Plasticity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (2018) 10:a030338. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a030338

9. Sakaguchi S, Toda M, Asano M, Itoh M, Morse SS, Sakaguchi N. T cell-mediated maintenance of natural self-tolerance: its breakdown as a possible cause of various autoimmune diseases. J Autoimmun (1996) 9:211–20. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1996.0026

10. Sakaguchi S, Mikami N, Wing JB, Tanaka A, Ichiyama K, Ohkura N. Regulatory T Cells and Human Disease. Annu Rev Immunol (2020) 38:541–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042718-041717

11. Gurram RK, Zhu J. Orchestration between ILC2s and Th2 cells in shaping type 2 immune responses. Cell Mol Immunol (2019) 16:225–35. doi: 10.1038/s41423-019-0210-8

12. Bal SM, Golebski K, Spits H. Plasticity of innate lymphoid cell subsets. Nat Rev Immunol (2020) 20:552–65. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0282-9

13. Borger JG, Le Gros G, Kirman JR. Editorial: The Role of Innate Lymphoid Cells in Mucosal Immunity. Front Immunol (2020) 11:1233. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01233

14. Martinez-Gonzalez I, Steer CA, Takei F. Lung ILC2s link innate and adaptive responses in allergic inflammation. Trends Immunol (2015) 36:189–95. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.01.005

15. Messing M, Jan-Abu SC, McNagny K. Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cells: Central Players in a Recurring Theme of Repair and Regeneration. Int J Mol Sci (2020) 21:1350. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041350

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Ealey KN, Moro K, Koyasu S. Are ILC2s Jekyll and Hyde in airway inflammation? Immunol Rev (2017) 278:207–18. doi: 10.1111/imr.12547

17. Sawa S, Lochner M, Satoh-Takayama N, Dulauroy S, Bérard M, Kleinschek M, et al. RORγt+ innate lymphoid cells regulate intestinal homeostasis by integrating negative signals from the symbiotic microbiota. Nat Immunol (2011) 12:320–6. doi: 10.1038/ni.2002

18. Sepahi A, Liu Q, Friesen L, Kim CH. Dietary fiber metabolites regulate innate lymphoid cell responses. Mucosal Immunol (2020) 4:317–30. doi: 10.1038/s41385-020-0312-8

19. Gonçalves P, Di Santo JP. An Intestinal Inflammasome - The ILC3-Cytokine Tango. Trends Mol Med (2016) 22:269–71. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.02.008

20. Jendrossek M, Standl M, Koletzko S, Lehmann I, Bauer C-P, Schikowski T, et al. Residential Air Pollution, Road Traffic, Greenness and Maternal Hypertension: Results from GINIplus and LISAplus. Int J Occup Environ Med (2017) 8:131–42. doi: 10.15171/ijoem.2017.1073

21. Burte E, Leynaert B, Marcon A, Bousquet J, Benmerad M, Bono R, et al. Long-term air pollution exposure is associated with increased severity of rhinitis in 2 European cohorts. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2020) 145:834–42.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.11.040

22. Eguiluz-Gracia I, Mathioudakis AG, Bartel S, Vijverberg SJ, Fuertes E, Comberiati P, et al. The need for clean air: The way air pollution and climate change affect allergic rhinitis and asthma. Allergy (2020) 75:2170–84. doi: 10.1111/all.14177

23. McDade TW. Early environments and the ecology of inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2012) 109(Suppl 2):17281–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202244109

24. Caillaud D, Leynaert B, Keirsbulck M, Nadif R. Indoor mould exposure, asthma and rhinitis: findings from systematic reviews and recent longitudinal studies. Eur Respir Rev (2018) 27:170137. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0137-2017

25. Kwon J-W, Park H-W, Kim WJ, Kim M-G, Lee S-J. Exposure to volatile organic compounds and airway inflammation. Environ Health (2018) 17:65. doi: 10.1186/s12940-018-0410-1

26. Gallant MJ, Ellis AK. Prenatal and early-life exposure to indoor air-polluting factors and allergic sensitization at 2 years of age. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol (2020) 124:283–7. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.11.019

27. Li Y-F, Langholz B, Salam MT, Gilliland FD. Maternal and grandmaternal smoking patterns are associated with early childhood asthma. Chest (2005) 127:1232–41. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.4.1232

28. Waddington CH. The strategies of the genes; a dsicussion of some aspects of theoretical biology . London: Allen & Unwin (1957).

Google Scholar

29. Holliday R, Pugh JE. DNA modification mechanisms and gene activity during development. Science (1975) 187:226–32.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

30. Compere SJ, Palmiter RD. DNA methylation controls the inducibility of the mouse metallothionein-I gene lymphoid cells. Cell (1981) 25:233–40. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90248-8

31. Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science (2001) 294:853–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1064921

32. Tang W-y, Levin L, Talaska G, Cheung YY, Herbstman J, Tang D, et al. Maternal Exposure to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and 5’-CpG Methylation of Interferon-γ in Cord White Blood Cells. Environ Health Perspect (2012) 120:1195–200. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103744

33. Potaczek DP, Miethe S, Schindler V, Alhamdan F, Garn H. Role of airway epithelial cells in the development of different asthma phenotypes. Cell Signal (2020) 69:109523. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2019.109523

34. Hew KM, Walker AI, Kohli A, Garcia M, Syed A, McDonald-Hyman C, et al. Childhood exposure to ambient polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons is linked to epigenetic modifications and impaired systemic immunity in T cells. Clin Exp Allergy (2015) 45:238–48. doi: 10.1111/cea.12377

35. Renz H, Conrad M, Brand S, Teich R, Garn H, Pfefferle PI. Allergic diseases, gene-environment interactions. Allergy (2011) 66 Suppl 95:10–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02622.x

36. Smits HH, Hiemstra PS, Da Prazeres Costa C, Ege M, Edwards M, Garn H, et al. Microbes and asthma: Opportunities for intervention. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2016) 137:690–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.01.004

37. Potaczek DP, Harb H, Michel S, Alhamwe BA, Renz H, Tost J. Epigenetics and allergy: from basic mechanisms to clinical applications. Epigenomics (2017) 9:539–71. doi: 10.2217/epi-2016-0162

38. Schaub B, Liu J, Höppler S, Schleich I, Huehn J, Olek S, et al. Maternal farm exposure modulates neonatal immune mechanisms through regulatory T cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2009) 123:774–82.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.01.056

39. Lluis A, Depner M, Gaugler B, Saas P, Casaca VI, Raedler D, et al. Increased regulatory T-cell numbers are associated with farm milk exposure and lower atopic sensitization and asthma in childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2014) 133:551–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.06.034

40. Abbring S, Ryan JT, Diks MA, Hols G, Garssen J, van Esch BC. Suppression of Food Allergic Symptoms by Raw Cow’s Milk in Mice is Retained after Skimming but Abolished after Heating the Milk-A Promising Contribution of Alkaline Phosphatase. Nutrients (2019) 11:1499. doi: 10.3390/nu11071499

41. Abbring S, Wolf J, Ayechu-Muruzabal V, Diks MAP, Alashkar Alhamwe B, Alhamdan F, et al. Raw Cow’s Milk Reduces Allergic Symptoms in a Murine Model for Food Allergy—A Potential Role for Epigenetic Modifications. Nutrients (2019) 11:1721. doi: 10.3390/nu11081721

42. Kirchner B, Pfaffl MW, Dumpler J, von Mutius E, Ege MJ. microRNA in native and processed cow’s milk and its implication for the farm milk effect on asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2016) 137:1893–95.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.10.028

43. Debarry J, Garn H, Hanuszkiewicz A, Dickgreber N, Blümer N, von Mutius E, et al. Acinetobacter lwoffii and Lactococcus lactis strains isolated from farm cowsheds possess strong allergy-protective properties. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2007) 119:1514–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.03.023

44. Brand S, Teich R, Dicke T, Harb H, Yildirim AÖ, Tost J, et al. Epigenetic regulation in murine offspring as a novel mechanism for transmaternal asthma protection induced by microbes. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2011) 128:618–25.e1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.035

45. Conrad ML, Ferstl R, Teich R, Brand S, Blümer N, Yildirim AÖ, et al. Maternal TLR signaling is required for prenatal asthma protection by the nonpathogenic microbe Acinetobacter lwoffii F78. J Exp Med (2009) 206:2869–77. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090845

46. Wenzel SE. Asthma phenotypes: the evolution from clinical to molecular approaches. Nat Med (2012) 18:716–25. doi: 10.1038/nm.2678

47. Ray A, Oriss TB, Wenzel SE. Emerging molecular phenotypes of asthma. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol (2015) 308:L130–40. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00070.2014

48. Szefler SJ, Wenzel S, Brown R, Erzurum SC, Fahy JV, Hamilton RG, et al. Asthma outcomes: biomarkers. J Allergy Clin Immunol (2012) 129:S9–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.12.979

49. Oksel C, Haider S, Fontanella S, Frainay C, Custovic A. Classification of Pediatric Asthma: From Phenotype Discovery to Clinical Practice. Front Pediatr (2018) 6:258. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00258

50. Saglani S, Custovic A. Childhood Asthma: Advances Using Machine Learning and Mechanistic Studies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2019) 199:414–22. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201810-1956CI

51. Siroux V, Basagaña X, Boudier A, Pin I, Garcia-Aymerich J, Vesin A, et al. Identifying adult asthma phenotypes using a clustering approach. Eur Respir J (2011) 38:310–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00120810

52. Depner M, Fuchs O, Genuneit J, Karvonen AM, Hyvärinen A, Kaulek V, et al. Clinical and epidemiologic phenotypes of childhood asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med (2014) 189:129–38. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201307-1198OC

53. Ajdacic-Gross V, Mutsch M, Rodgers S, Tesic A, Müller M, Seifritz E, et al. A step beyond the hygiene hypothesis-immune-mediated classes determined in a population-based study. BMC Med (2019) 17:75. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1311-z

54. Debeuf N, Haspeslagh E, van Helden M, Hammad H, Lambrecht BN. Mouse Models of Asthma. Curr Protoc Mouse Biol (2016) 6:169–84. doi: 10.1002/cpmo.4

55. Tan H-TT, Hagner S, Ruchti F, Radzikowska U, Tan G, Altunbulakli C, et al. Tight junction, mucin, and inflammasome-related molecules are differentially expressed in eosinophilic, mixed, and neutrophilic experimental asthma in mice. Allergy (2019) 74:294–307. doi: 10.1111/all.13619

56. Hagner S, Keller M, Raifer H, Tan H-TT, Akdis CA, Buch T, et al. T cell requirement and phenotype stability of house dust mite-induced neutrophil airway inflammation in mice. Allergy (2020) 75:2970–3. doi: 10.1111/all.14424

57. Marqués-García F, Marcos-Vadillo E. Review of Mouse Models Applied to the Study of Asthma. Methods Mol Biol (2016) 1434:213–22. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3652-6_15

58. Maltby S, Tay HL, Yang M, Foster PS. Mouse models of severe asthma: Understanding the mechanisms of steroid resistance, tissue remodelling and disease exacerbation. Respirology (2017) 22:874–85. doi: 10.1111/resp.13052

59. McCann JR, Mason SN, Auten RL, St Geme JW, Seed PC. Early-Life Intranasal Colonization with Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae Exacerbates Juvenile Airway Disease in Mice. Infect Immun (2016) 84:2022–30. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01539-15

60. Malinczak C-A, Fonseca W, Rasky AJ, Ptaschinski C, Morris S, Ziegler SF, et al. Sex-associated TSLP-induced immune alterations following early-life RSV infection leads to enhanced allergic disease. Mucosal Immunol (2019) 12:969–79. doi: 10.1038/s41385-019-0171-3

61. Wickens K, Barthow C, Mitchell EA, Kang J, van Zyl N, Purdie G, et al. Effects of Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 in early life on the cumulative prevalence of allergic disease to 11 years. Pediatr Allergy Immunol (2018) 29:808–14. doi: 10.1111/pai.12982

62. Bach J-F. The effect of infections on susceptibility to autoimmune and allergic diseases. N Engl J Med (2002) 347:911–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020100

63. Bach J-F. The hygiene hypothesis in autoimmunity: the role of pathogens and commensals. Nat Rev Immunol (2018) 18:105–20. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.111

64. Bauer ME, Teixeira AL. Inflammation in psychiatric disorders: what comes first? Ann N Y Acad Sci (2019) 1437:57–67. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13712

65. Petra AI, Panagiotidou S, Hatziagelaki E, Stewart JM, Conti P, Theoharides TC. Gut-Microbiota-Brain Axis and Its Effect on Neuropsychiatric Disorders With Suspected Immune Dysregulation. Clin Ther (2015) 37:984–95. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.04.002

66. Langgartner D, Lowry CA, Reber SO. Old Friends, immunoregulation, and stress resilience. Pflugers Arch (2019) 471:237–69. doi: 10.1007/s00424-018-2228-7

67. Willyard C. How gut microbes could drive brain disorders. Nature (2021) 590:22–5. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-00260-3

68. Cenit MC, Sanz Y, Codoñer-Franch P. Influence of gut microbiota on neuropsychiatric disorders. World J Gastroenterol (2017) 23:5486–98. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i30.5486

69. Untersmayr E, Bax HJ, Bergmann C, Bianchini R, Cozen W, Gould HJ, et al. AllergoOncology: Microbiota in allergy and cancer-A European Academy for Allergy and Clinical Immunology position paper. Allergy (2019) 74:1037–51. doi: 10.1111/all.13718

70. Oikonomopoulou K, Brinc D, Kyriacou K, Diamandis EP. Infection and cancer: revaluation of the hygiene hypothesis. Clin Cancer Res (2013) 19:2834–41. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3661

71. Greaves M. Infection, immune responses and the aetiology of childhood leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer (2006) 6:193–203. doi: 10.1038/nrc1816

72. Greaves M. A causal mechanism for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer (2018) 18:471–84. doi: 10.1038/s41568-018-0015-6

73. Cardwell CR, McKinney PA, Patterson CC, Murray LJ. Infections in early life and childhood leukaemia risk: a UK case-control study of general practitioner records. Br J Cancer (2008) 99:1529–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604696

74. Simpson J, Smith A, Ansell P, Roman E. Childhood leukaemia and infectious exposure: a report from the United Kingdom Childhood Cancer Study (UKCCS). Eur J Cancer (2007) 43:2396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.07.027

75. Orsi L, Magnani C, Petridou ET, Dockerty JD, Metayer C, Milne E, et al. Living on a farm, contact with farm animals and pets, and childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: pooled and meta-analyses from the Childhood Leukemia International Consortium. Cancer Med (2018) 7:2665–81. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1466

Keywords: hygiene hypothesis, allergy, asthma, non-communicable inflammatory diseases, chronic inflammation

Citation: Garn H, Potaczek DP and Pfefferle PI (2021) The Hygiene Hypothesis and New Perspectives—Current Challenges Meeting an Old Postulate. Front. Immunol. 12:637087. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.637087

Received: 02 December 2020; Accepted: 04 March 2021; Published: 18 March 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Garn, Potaczek and Pfefferle. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Holger Garn, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Hygiene Hypothesis - Learning From but Not Living in the Past

Affiliations.

- 1 Comprehensive Biobank Marburg, Medical Faculty, Philipps University of Marburg, Comprehensive Biobank Marburg, Marburg, Germany.

- 2 German Center for Lung Research (DZL), Marburg, Germany.

- 3 German Biobank Alliance, Marburg, Germany.

- 4 Institute for Pathology, Medical Faculty, Institute for Pathology, Philipps University of Marburg, Marburg, Germany.

- 5 Translational Inflammation Research Division & Core Facility for Single Cell Multiomics, Medical Faculty, Biochemical Pharmacological Center, Philipps University of Marburg, Marburg, Germany.

- PMID: 33796103

- PMCID: PMC8007786

- DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.635935

Postulated by Strachan more than 30 years ago, the Hygiene Hypothesis has undergone many revisions and adaptations. This review journeys back to the beginnings of the Hygiene Hypothesis and describes the most important landmarks in its development considering the many aspects that have refined and generalized the Hygiene Hypothesis over time. From an epidemiological perspective, the Hygiene Hypothesis advanced to a comprehensive concept expanding beyond the initial focus on allergies. The Hygiene Hypothesis comprise immunological, microbiological and evolutionary aspects. Thus, the original postulate developed into a holistic model that explains the impact of post-modern life-style on humans, who initially evolved in close proximity to a more natural environment. Focusing on diet and the microbiome as the most prominent exogenous influences we describe these discrepancies and the resulting health outcomes and point to potential solutions to reestablish the immunological homeostasis that frequently have been lost in people living in developed societies.

Keywords: T cell-response; allergy; asthma; hygiene hypothesis; immune tolerance; microbiome.

Copyright © 2021 Pfefferle, Keber, Cohen and Garn.

Publication types

- Historical Article

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Adaptive Immunity*

- Asthma / immunology

- Asthma / microbiology

- Bacteria / immunology*

- Bacteria / pathogenicity

- Diet / adverse effects

- Evolution, Molecular

- Gastrointestinal Microbiome / immunology*

- History, 20th Century

- History, 21st Century

- Host-Pathogen Interactions

- Hygiene Hypothesis* / history

- Immune Tolerance

- Immunity, Innate*

- T-Lymphocytes / immunology*

- T-Lymphocytes / metabolism

- T-Lymphocytes / microbiology

Is Being Too Clean Bad for Your Health?

From taking a shower to brushing your teeth to washing your hands, you practice good personal hygiene on the daily. And it’s not just because you like the way your new shampoo smells, either. You know these habits keep you clean and, in some cases, can even help prevent you from getting sick.

But after all that lathering, rinsing and scrubbing, can you actually be too clean for your own good?

That’s what supporters of the so-called hygiene hypothesis think, saying that the rising rates of allergies, asthma and other autoimmune disorders in children is linked to our increasingly hygienic surroundings. And while statistics appear to back this up, experts in the fields of immunology and infectious disease say, not so fast.

“To say that being clean means you’re at a higher risk of allergies or asthma is not quite right,” agrees Dr. John Lynch , an associate microbiology professor at the University of Washington School of Medicine and medical director of Harborview Medical Center’s Infection Control, Antibiotic Stewardship and Employee Health programs.

The problem, he says, is that the hygiene hypothesis doesn’t tell the full story.

What is the hygiene hypothesis?

Largely popularized by British epidemiologist David Strachan in 1989, the hygiene hypothesis theorizes that because modern parents are able to clean their children and households more effectively, kids these days just aren’t exposed to the same level of germs as previous generations.

That excessively sterile upbringing — hand sanitizer, anyone? — means children’s immune systems aren’t able to develop properly and, as a result, malfunction.

When you look at the statistics, they seem to support this idea. In developed countries, the number of kids who have asthma and allergies has been going up.

Washington state has some of the highest incidences of asthma in the nation, and it’s only increasing. More than 600,000 Washingtonians have asthma, and nearly 120,000 of them are children.

Research from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows that the same trend applies to kids who have food allergies. Now 1 in 13 children in the United States has a food allergy, a 50% increase between 1997 and 2011. To put it in perspective, that means in every American classroom, there are two kids who may have a food-related allergic reaction.

Is the hygiene hypothesis true?

Don’t toss out your hand soap or quit bathing your kids just yet. Remember, while data appears to back up the hygiene hypothesis, it’s not a complete picture.

“There was no randomized control study to determine the hygiene hypothesis,” Lynch explains. “It ends up being observations of populations, biased by our ability to detect diseases. You have less likelihood of being diagnosed with asthma or even diabetes in a developing country versus a developed country.”

What Lynch means is that as the field of medicine has advanced in recent decades, so has our ability to detect and diagnose conditions like the aforementioned food allergies and asthma. And the reason why much of the evidence to support the hygiene hypothesis comes from industrialized countries is because these nations have greater medical infrastructure and resources to detect autoimmune dysfunctions than the developing world.

So while the number of children with asthma and food allergies is higher than in decades past, there’s no way to know if that’s because more kids actually have those conditions or if it’s because doctors are more able to recognize and diagnose those conditions.

Another problem with the hygiene hypothesis, Lynch notes, is that while getting exposed to some germs does help build up your immune systems, other types of bacteria and viruses can actually cause asthma or serious diseases.

That’s why researchers and medical professionals in Lynch’s field of infectious disease and immunology cringe at the name “hygiene hypothesis,” he says. It implies that good personal hygiene is related to higher rates of disease when, in fact, it’s the opposite.

Think about it this way: If the hygiene hypothesis is really accurate and being overly clean makes our immune systems malfunction, children who don’t wash their hands, are exposed to pathogens on a regular basis and live in unclean conditions would be the healthiest.

“Unfortunately, we know that people who live in places that lack access to hygiene die more frequently,” Lynch says.

How do you build up a child’s immune system?

It’s not that the hygiene hypothesis gets it all wrong. Children do need to be exposed to certain microorganisms in order to influence the right immune response and develop a robust immune system. And having a too-clean environment can hinder that in some ways.

“We don’t need to sterilize things with antibacterial products or create an incredibly hygienic environment,” Lynch says. “You don’t want to put any extra chemicals or agents in anything because that’s how you create antibiotic-resistant bacteria.”

In fact, your body is full of trillions of bacteria, fungi and viruses — an entire community called your microbiota — which are critical to your immune response and overall health.

Now here’s where glimmers of the hygiene hypothesis come in: Children develop a healthy microbiota by acquiring bacteria in a variety of ways, from vaginal birth and breastfeeding to getting kissed by their parents and sticking their fingers in their mouths as babies.

“That’s all normal,” Lynch says. “We don’t want women washing their breasts before breastfeeding or parents washing their lips before kissing their children.”

What also matters for immune development, though, is what you’re exposed to and how that affects your body. Getting a common cold virus is a totally normal part of childhood. But being exposed to an antibiotic-resistant superbug is a much more serious issue.

“When you’re talking about the hygiene hypothesis, the point of contention is that the focus should be less about hygiene and more about access to the right microbiota,” Lynch explains.

What’s the takeaway from the hygiene hypothesis controversy?

So while the hygiene hypothesis isn’t totally correct, going in the opposite direction to an overly sterilized childhood isn’t exactly healthy either. It can feel like the balance between exposing children to good bacteria and keeping them safe from the bad stuff is pretty much out of your control.

Just try to keep everything in perspective, Lynch says. Use common sense — and maybe go easy on the hand sanitizer.

“I like to think of it like this: Hand washing is important if you’re around someone who’s sick or if your kid is rolling around on the floor at a restaurant, but maybe not so much if they’re just playing outside at the park,” he says.

Recommended for you

Plus, what to do, where to go and who to call if you have an exposure.

- Load more stories

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 16 October 2017

The hygiene hypothesis in autoimmunity: the role of pathogens and commensals

- Jean-François Bach 1 , 2 , 3

Nature Reviews Immunology volume 18 , pages 105–120 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

19k Accesses

298 Citations

264 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Autoimmune diseases

- Toll-like receptors

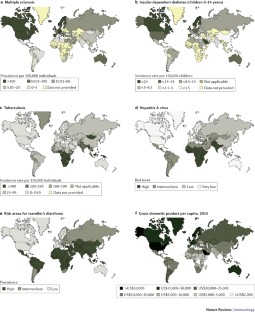

The initial application of the hygiene hypothesis for autoimmune diseases proposed in the early 2000s has been confirmed and consolidated by a wealth of published data in both animal models and human autoimmune conditions.

The hygiene hypothesis probably explains the uneven geographical distribution of autoimmune diseases in the world. Individuals migrating from countries with low incidence of autoimmune diseases to countries with high incidence develop the disease with the frequency of the host country, provided that migration occurred at a young age and under a threshold that varies according to the disease.

Pathogenic bacteria, viruses and parasites are often endowed with strong protective effects on autoimmunity even when infection occurs late after birth.

Gut commensal bacteria may also have a protective role in autoimmunity when administered early in life.

Pathogens, parasites and commensals essentially act by stimulating immune regulatory pathways, implicating the innate and the adaptive immune system. Importantly, the effect is seen with both living organisms and their derivatives or purified extracts.

Both pathogens and commensals stimulate pattern recognition receptors, including Toll-like receptors (TLRs) to protect against autoimmunity. This effect may be mimicked by TLR agonists acting through pharmacological stimulation or desensitization of the target receptor.