Can Money Really Buy Happiness?

Money and happiness are related—but not in the way you think..

Updated November 10, 2023 | Reviewed by Chloe Williams

- More money is linked to increased happiness, some research shows.

- People who won the lottery have greater life satisfaction, even years later.

- Wealth is not associated with happiness globally; non-material things are more likely to predict wellbeing.

- Money, in and of itself, cannot buy happiness, but it can provide a means to the things we value in life.

Money is a big part of our lives, our identities, and perhaps our well-being. Sometimes, it can feel like your happiness hinges on how much cash is in your bank account. Have you ever thought to yourself, “If only I could increase my salary by 12 percent, I’d feel better”? How about, “I wish I had an inheritance. How easier life would be!” I don’t blame you — I’ve had the same thoughts many times.

But what does psychological research say about the age-old question: Can money really buy happiness? Let’s take a brutally honest exploration of how money and happiness are (and aren’t) related. (Spoiler alert: I’ve got bad news, good news, and lots of caveats.)

Higher earners are generally happier

Over 10 years ago, a study based on Gallup Poll data on 1,000 people made a big headline in the news. It found that people with higher incomes report being happier... but only up to an annual income of $75,000 (equivalent to about $90,000 today). After this point, a high emotional well-being wasn’t directly correlated to more money. This seemed to show that once a persons’ basic (and some “advanced”) needs are comfortably met, more money isn’t necessary for well-being.

But a new 2021 study of over one million participants found that there’s no such thing as an inflection point where more money doesn’t equal more happiness, at least not up to an annual salary of $500,000. In this study, participants’ well-being was measured in more detail. Instead of being asked to remember how well they felt in the past week, month, or year, they were asked how they felt right now in the moment. And based on this real-time assessment, very high earners were feeling great.

Similarly, a Swedish study on lottery winners found that even after years, people who won the lottery had greater life satisfaction, mental health, and were more prepared to face misfortune like divorce , illness, and being alone than regular folks who didn’t win the lottery. It’s almost as if having a pile of money made those things less difficult to cope with for the winners.

Evaluative vs. experienced well-being

At this point, it's important to suss out what researchers actually mean by "happiness." There are two major types of well-being psychologists measure: evaluative and experienced. Evaluative well-being refers to your answer to, “How do you think your life is going?” It’s what you think about your life. Experienced well-being, however, is your answer to, “What emotions are you feeling from day to day, and in what proportions?” It is your actual experience of positive and negative emotions.

In both of these studies — the one that found the happiness curve to flatten after $75,000 and the one that didn't — the researchers were focusing on experienced well-being. That means there's a disagreement in the research about whether day-to-day experiences of positive emotions really increase with higher and higher incomes, without limit. Which study is more accurate? Well, the 2021 study surveyed many more people, so it has the advantage of being more representative. However, there is a big caveat...

Material wealth is not associated with happiness everywhere in the world

If you’re not a very high earner, you may be feeling a bit irritated right now. How unfair that the rest of us can’t even comfort ourselves with the idea that millionaires must be sad in their giant mansions!

But not so fast.

Yes, in the large million-person study, experienced well-being (aka, happiness) did continually increase with higher income. But this study only included people in the United States. It wouldn't be a stretch to say that our culture is quite materialistic, more so than other countries, and income level plays a huge role in our lifestyle.

Another study of Mayan people in a poor, rural region of Yucatan, Mexico, did not find the level of wealth to be related to happiness, which the participants had high levels of overall. Separately, a Gallup World Poll study of people from many countries and cultures also found that, although higher income was associated with higher life evaluation, it was non-material things that predicted experienced well-being (e.g., learning, autonomy, respect, social support).

Earned wealth generates more happiness than inherited wealth

More good news: For those of us with really big dreams of “making it” and striking it rich through talent and hard work, know that the actual process of reaching your dream will not only bring you cash but also happiness. A study of ultra-rich millionaires (net worth of at least $8,000,000) found that those who earned their wealth through work and effort got more of a happiness boost from their money than those who inherited it. So keep dreaming big and reaching for your entrepreneurial goals … as long as you’re not sacrificing your actual well-being in the pursuit.

There are different types of happiness, and wealth is better for some than others

We’ve been talking about “happiness” as if it’s one big thing. But happiness actually has many different components and flavors. Think about all the positive emotions you’ve felt — can we break them down into more specifics? How about:

- Contentment

- Gratefulness

...and that's just a short list.

It turns out that wealth may be associated with some of these categories of “happiness,” specifically self-focused positive emotions such as pride and contentment, whereas less wealthy people have more other-focused positive emotions like love and compassion.

In fact, in the Swedish lottery winners study, people’s feelings about their social well-being (with friends, family, neighbors, and society) were no different between lottery winners and regular people.

Money is a means to the things we value, not happiness itself

One major difference between lottery winners and non-winners, it turns out, is that lottery winners have more spare time. This is the thing that really makes me envious , and I would hypothesize that this is the main reason why lottery winners are more satisfied with their life.

Consider this simply: If we had the financial security to spend time on things we enjoy and value, instead of feeling pressured to generate income all the time, why wouldn’t we be happier?

This is good news. It’s a reminder that money, in and of itself, cannot literally buy happiness. It can buy time and peace of mind. It can buy security and aesthetic experiences, and the ability to be generous to your family and friends. It makes room for other things that are important in life.

In fact, the researchers in that lottery winner study used statistical approaches to benchmark how much happiness winning $100,000 brings in the short-term (less than one year) and long-term (more than five years) compared to other major life events. For better or worse, getting married and having a baby each give a bigger short-term happiness boost than winning money, but in the long run, all three of these events have the same impact.

What does this mean? We make of our wealth and our life what we will. This is especially true for the vast majority of the world made up of people struggling to meet basic needs and to rise out of insecurity. We’ve learned that being rich can boost your life satisfaction and make it easier to have positive emotions, so it’s certainly worth your effort to set goals, work hard, and move towards financial health.

But getting rich is not the only way to be happy. You can still earn health, compassion, community, love, pride, connectedness, and so much more, even if you don’t have a lot of zeros in your bank account. After all, the original definition of “wealth” referred to a person’s holistic wellness in life, which means we all have the potential to be wealthy... in body, mind, and soul.

Kahneman, D., & Deaton, A.. High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. . Proceedings of the national academy of sciences. 2010.

Killingsworth, M. A. . Experienced well-being rises with income, even above $75,000 per year .. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2021.

Lindqvist, E., Östling, R., & Cesarini, D. . Long-run effects of lottery wealth on psychological well-being. . The Review of Economic Studies. 2020.

Guardiola, J., González‐Gómez, F., García‐Rubio, M. A., & Lendechy‐Grajales, Á.. Does higher income equal higher levels of happiness in every society? The case of the Mayan people. . International Journal of Social Welfare. 2013.

Diener, E., Ng, W., Harter, J., & Arora, R. . Wealth and happiness across the world: material prosperity predicts life evaluation, whereas psychosocial prosperity predicts positive feeling. . Journal of personality and social psychology. 2010.

Donnelly, G. E., Zheng, T., Haisley, E., & Norton, M. I.. The amount and source of millionaires’ wealth (moderately) predict their happiness . . Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2018.

Piff, P. K., & Moskowitz, J. P. . Wealth, poverty, and happiness: Social class is differentially associated with positive emotions.. Emotion. 2018.

Jade Wu, Ph.D., is a clinical health psychologist and host of the Savvy Psychologist podcast. She specializes in helping those with sleep problems and anxiety disorders.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Does More Money Really Make Us More Happy?

- Elizabeth Dunn

- Chris Courtney

A big paycheck won’t necessarily bring you joy

Although some studies show that wealthier people tend to be happier, prioritizing money over time can actually have the opposite effect.

- But even having just a little bit of extra cash in your savings account ($500), can increase your life satisfaction. So how can you keep more cash on hand?

- Ask yourself: What do I buy that isn’t essential for my survival? Is the expense genuinely contributing to my happiness? If the answer to the second question is no, try taking a break from those expenses.

- Other research shows there are specific ways to spend your money to promote happiness, such as spending on experiences, buying time, and investing in others.

- Spending choices that promote happiness are also dependent on individual personalities, and future research may provide more individualized advice to help you get the most happiness from your money.

Where your work meets your life. See more from Ascend here .

How often have you willingly sacrificed your free time to make more money? You’re not alone. But new research suggests that prioritizing money over time may actually undermine our happiness.

- ED Elizabeth Dunn is a professor of psychology at the University of British Columbia and Chief Science Officer of Happy Money, a financial technology company with a mission to help borrowers become savers. She is also co-author of “ Happy Money: The Science of Happier Spending ” with Dr. Michael Norton. Her TED2019 talk on money and happiness was selected as one of the top 10 talks of the year by TED.

- CC Chris Courtney is the VP of Science at Happy Money. He utilizes his background in cognitive neuroscience, human-computer interaction, and machine learning to drive personalization and engagement in products designed to empower people to take control of their financial lives. His team is focused on creating innovative ways to provide more inclusionary financial services, while building tools to promote financial and psychological well-being and success.

Partner Center

Happiness Economics: Can Money Buy Happiness?

It only costs a small amount, a slight risk, with the possibility of a substantial reward.

But will it make you happy? Will it give you long-lasting happiness?

Undoubtedly, there will be a temporary peak in happiness, but will all your troubles finally fade away?

That is what we will investigate today. We explore the economics of happiness and whether money can buy happiness. In this post, we will start by broadly exploring the topic and then look at theories and substantive research findings. We’ll even have a look at previous lottery winners.

For interested readers, we will list interesting books and podcasts for further enjoyment and share a few of our own happiness resources.

Ka-ching: Let’s get rolling!

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Happiness & Subjective Wellbeing Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients identify sources of authentic happiness and strategies to boost wellbeing.

This Article Contains

What is happiness economics, theory of the economics of happiness, can money buy happiness 5 research findings, 6 fascinating books and podcasts on the topic, resources from positivepsychology.com, a take-home message.

Happiness economics is a field of economics that recognizes happiness and wellbeing as important outcome measures, alongside measures typically used, such as employment, education, and health care.

Economics emphasizes how specific economic/financial characteristics affect our wellbeing (Easterlin, 2004).

For example, does employment result in better health and longer lifespan, among other metrics? Do people in wealthier countries have access to better education and longer life spans?

In the last few decades, there has been a shift in economics, where researchers have recognized the importance of the subjective rating of happiness as a valuable and desirable outcome that is significantly correlated with other important outcomes, such as health (Steptoe, 2019) and productivity (DiMaria et al., 2020).

Broadly, happiness is a psychological state of being, typically researched and defined using psychological methods. We often measure it using self-report measures rather than objective measures that are less vulnerable to misinterpretation and error.

Including happiness in economics has opened up an entirely new avenue of research to explore the relationship between happiness and money.

Andrew Clark (2018) illustrates the variability in the term happiness economics with the following examples:

- Happiness can be a predictor variable, influencing our decisions and behaviors.

- Happiness might be the desired outcome, so understanding how and why some people are happier than others is essential.

However, the connection between our behavior and happiness must be better understood. Even though “being happy” is a desired outcome, people still make decisions that prevent them from becoming happier. For example, why do we choose to work more if our work does not make us happier? Why are we unhappy even if our basic needs are met?

An example of how happiness can influence decision-making

Sometimes, we might choose not to maximize a monetary or financial gain but place importance on other, more subjective outcomes.

To illustrate: If faced with two jobs — one that pays well but will bring no joy and another that pays less but will bring much joy — some people would prefer to maximize their happiness over financial gain.

If this decision were evaluated using a utility framework where the only valued outcomes were practical, then the decision would seem irrational. However, this scenario suggests that psychological outcomes, such as the experience of happiness, are as crucial as other socio-economic outcomes.

Economists recognize that subjective wellbeing , or happiness, is an essential characteristic and sometimes a desirable outcome that can motivate our decision-making.

In the last few decades, economics has shifted to include happiness as a measurable and vital part of general wellbeing (Graham, 2005).

The consequence is that typical economic questions now also look at the impact of employment, finances, and other economic metrics on the subjective rating and experience of happiness at individual and country levels.

Happiness is such a vital outcome in society and economic activity that it must be involved in policy making. The subjective measure of happiness is as important as other typical measures used in economics.

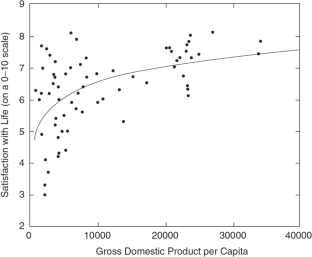

Many factors can contribute to happiness. In this post, we consider the role of money. The relationship between happiness, or subjective wellbeing, and money is assumed to be positive: More money means greater happiness.

However, the relationship between money and happiness is paradoxical: More money does not guarantee happiness (for an excellent review, see Graham, 2005).

Specifically, low levels of income are correlated with unhappiness. However, as our individual wealth increases and our basic needs are met, our needs change and differ in their importance.

Initially, our happiness is affected by absolute levels of income, but at a certain threshold, we place importance on relative levels of income. Knowing how we rank and compare to other people, in terms of wealth and material possession, influences our happiness.

The relationship between wealth and happiness continues to increase, but only to a certain point; at this stage, more wealth does not guarantee more happiness (Easterlin, 1974; Diener et al., 1993).

This may be at odds with our everyday lived experience. Most of us choose to work longer hours or multiple jobs so that we make more money. However, what is the point of doing this if money does not increase our happiness? Why do we seem to think that more money will make us happier?

History of the economics of happiness

The relationship between economics and happiness originated in the early 1970s. Brickman and Campbell (1971, as cited in Brickman et al., 1978) first argued that the typical outcomes of a successful life, such as wealth or income, had no impact on individual wellbeing.

Easterlin (1974) expanded these results and showed that although wealthier people tend to be happier than poor people in the same country, the average happiness levels within a country remained unchanged even as the country’s overall wealth increased.

The inconsistent relationship between happiness and income and its sensitivity to critical income thresholds make this topic so interesting.

There is some evidence that wealthier countries are happier than others, but only when comparing the wealthy with the poor (Easterlin, 1974; Graham, 2005).

As countries become wealthier, citizens report higher happiness, but this relationship is strongest when the starting point is poverty. Above a certain income threshold, happiness no longer increases (Diener et al., 1993).

Interestingly, people tend to agree on the amount of money needed to make them happy; but beyond a certain value, there is little increase in happiness (Haesevoets et al., 2022).

Measurement challenges

Measuring happiness accurately and reliably is challenging. Researchers disagree on what happiness means.

It is not the norm in economics to measure happiness by directly asking a participant how happy they are; instead, happiness is inferred through:

- Subjective wellbeing (Clark, 2018; Easterlin, 2004)

- A combination of happiness and life satisfaction (Bruni, 2007)

Furthermore, happiness can refer to an acute psychological state, such as feeling happy after a nice meal, or a lasting state similar to contentment (Nettle, 2005).

Researchers might use different definitions of happiness and ways to measure it, thus leading to contradictory results. For example, happiness might be used synonymously with subjective wellbeing and can refer to several things, including life satisfaction and financial satisfaction (Diener & Oishi, 2000).

It seems contradictory that wealthier nations are not happier overall than poorer nations and that increasing the wealth of poorer nations does not guarantee that their happiness will increase too. What could then be done to increase happiness?

Download 3 Free Happiness Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients with tools to discover authentic happiness and cultivate subjective well-being.

Download 3 Free Happiness Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

What is the relationship between income/wealth and happiness? To answer that question, we looked at studies to see where and how money improves happiness, but we’ll also consider the limitations to the positive effect of income.

Money buys access; jobs boost happiness

Overwhelming evidence shows that wealth is correlated with measures of wellbeing.

Wealthier people have access to better healthcare, education, and employment, which in turn results in higher life satisfaction (Helliwell et al., 2012). A certain amount of wealth is needed to meet basic needs, and satisfying these needs improves happiness (Veenhoven & Ehrhardt, 1995).

Increasing happiness through improved quality of life is highest for poor households, but this is explained by the starting point. Access to essential services improves the quality of life, and in turn, this improves measures of wellbeing.

Most people gain wealth through employment; however, it is not just wealth that improves happiness; instead, employment itself has an important association with happiness. Happiness and employment are also significantly correlated with each other (Helliwell et al., 2021).

Lockdown on happiness

The World Happiness Report (Helliwell et al., 2021) reports that unemployment increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, and this was accompanied by a marked decline in happiness and optimism.

The pandemic also changed how we evaluated certain aspects of our lives; for example, the relationship between income and happiness declined. After all, what is the use of money if you can’t spend it? In contrast, the association between happiness and having a partner increased (Helliwell et al., 2021).

Wealthier states smile more, but is it real?

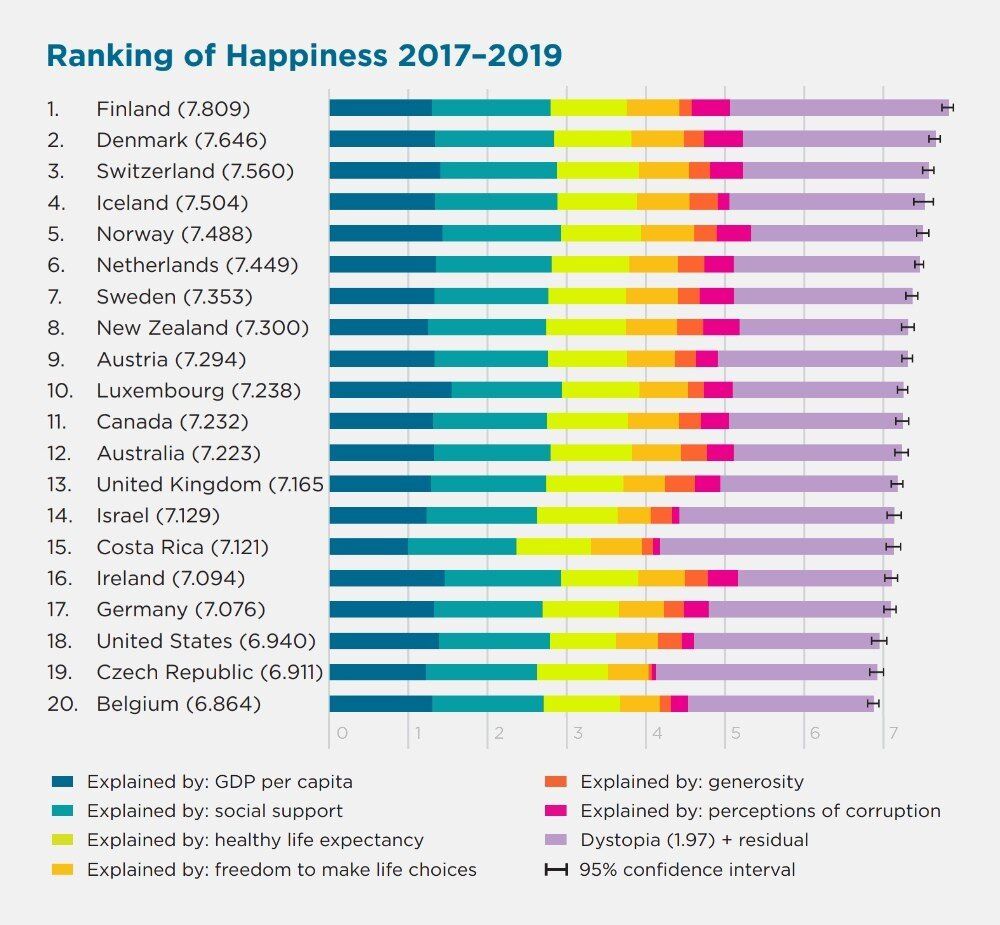

If we took a snapshot of happiness and a country’s wealth, we would find that richer countries tend to have happier populations than poorer countries.

For example, based on the 2021 World Happiness Report, the top five happiest countries — which are also wealthy countries — are Finland, Iceland, Denmark, Switzerland, and the Netherlands (Helliwell et al., 2021).

In contrast, the unhappiest countries are those that tend to be emerging markets or have a lower gross domestic product (GDP), e.g., Zimbabwe, Tanzania, and India (Graham, 2005; Helliwell et al., 2021).

At face value, this makes sense: Poorer countries most likely have other factors associated with them, e.g., higher unemployment, more crime, and less political stability. So, based on this cross-sectional data, a country’s wealth and happiness levels appear to be correlated. However, over a more extended period, the relationship between happiness and GDP is nil (Easterlin, 2004).

That is, the subjective wellbeing of a population does not increase as a country becomes richer. Even though the wealth of various countries worldwide has increased over time, the overall happiness levels have not increased similarly or have remained static (Kahneman et al., 2006). This is known as a happiness–income paradox.

Easterlin (2004) posits four explanations for this finding:

- Societal and individual gains associated with increased wealth are concentrated among the extremely wealthy.

- Our degree of happiness is informed by how we compare to other people, and this relative comparison does not change as country-wide wealth increases.

- Happiness is not limited to only wealth and financial status, but is affected by other societal and political factors, such as crime, education, and trust in the government.

- Long-term satisfaction and contentment differ from short-term, acute happiness.

Kahneman et al. (2006) provide an alternative explanation centered on the method typically used by researchers. Specifically, they argue that the order of the questions asked to measure happiness and how these questions are worded have a focusing effect. Through the question, the participant’s attention to their happiness is sharpened — like a lens in a camera — and their happiness needs to be over- or underestimated.

Kahneman et al. (2006) also point out that job advancements like a raise or a promotion are often accompanied by an increase in salary and work hours. Consequently, high-paying jobs often result in less leisure time available to spend with family or on hobbies and can cause more unhappiness.

Not all that glitters is gold

Extensive research explored whether a sudden financial windfall was associated with a spike in happiness (e.g., Sherman et al., 2020). The findings were mixed. Sometimes, having more money is associated with increased life satisfaction and improved physical and mental health.

This boost in happiness, however, is not guaranteed, nor is it long. Sometimes, individuals even wish it had never happened (Brickman et al., 1978; Sherman et al., 2020).

Consider lottery winners. These people win sizable sums of money — typically more extensive than a salary increase — large enough to impact their lives significantly. Despite this, research has consistently shown that although lottery winners report higher immediate, short-term happiness, they do not experience higher long-term happiness (Sherman et al., 2020).

Here are some reasons for this:

- Previous everyday activities and experiences become less enjoyable when compared to a unique, unusual experience like winning the lottery.

- People habituate to their new lifestyle.

- A sudden increase in wealth can disrupt social relationships among friends and family members.

- Work and hobbies typically give us small nuggets of joy over a more extended period (Csikszentmihalyi et al., 2005). These activities can lose their meaning over a longer period, resulting in more unhappiness (Sherman et al., 2020; Brickman et al., 1978).

Sherman et al. (2020) further argue that lottery winners who decide to quit their job after winning, but do not fill this newly available time with some type of meaningful hobby or interest, are also more likely to become unhappy.

Passive activities do not provide the same happiness as work or hobbies. Instead, if lottery winners continue to take part in activities that give them meaning and require active engagement, then they can avoid further unhappiness.

Happiness: Is it temperature or climate?

Like most psychological research, part of the challenge is clearly defining the topic of investigation — a task made more daunting when the topic falls within two very different fields.

Nettle (2005) describes happiness as a three-tiered concept, ranging from short-lived but intense on one end of the spectrum to more abstract and deep on the other.

The first tier refers to transitory feelings of joy, like when one opens up a birthday present.

The second tier describes judgments about feelings, such as feeling satisfied with your job. The third tier is more complex and refers to life satisfaction.

Across research, different definitions are used: Participants are asked about feelings of (immediate) joy, overall life satisfaction, moments of happiness or satisfaction, and mental wellbeing . The concepts are similar but not identical, thus influencing the results.

Most books on happiness economics are textbooks. Although no doubt very interesting, they’re not the easy-reading books we prefer to recommend.

Instead, below you will find a range of books written by economists that explore happiness. These should provide a good springboard on the overall topic of happiness and what influences it, in case any of our readers want to pick up a more in-depth textbook afterward.

If you have a happiness book you would recommend, please let us know in the comments section.

1. Happiness: Lessons from a New Science – Richard Layard

Richard Layard, a lead economist based in London, explores in his book if and how money can affect happiness.

Layard does an excellent job of introducing topics from various fields and framing them appropriately for the reader.

The book is aimed at readers from varying academic and professional backgrounds, so no experience is needed to enjoy it.

Find the book on Amazon .

2. Happiness by Design: Change What You Do, Not How You Think – Paul Dolan

This book has a more practical spin. The author explains how we can use existing research and theories to make small changes to increase our happiness.

Paul Dolan’s primary thesis is that practical things will have a bigger effect than abstract methods, and we should change our behavior rather than our thinking.

The book is a quick read (airport-perfect!), and Daniel Kahneman penned the foreword.

3. The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed and Happiness – Morgan Housel

This book is not necessarily about happiness economics, but it is close enough to the overall theme that it is worth mentioning.

Since most people are concerned with making more money, this book helps teach the reader why we make the decisions we do and how we make better decisions about our money.

This book is a worthwhile addition to any bookcase if you are interested in the relationship between finances and psychology in general.

4. Happiness: The Science Behind Your Smile – Daniel Nettle

If you are interested in happiness overall, then we recommend Happiness: The Science Behind Your Smile by Daniel Nettle, a professor of behavioral science at Newcastle University.

In this book, he takes a scientific approach to explaining happiness, starting with an in-depth exploration of the definition of happiness and some of its challenges.

The research that he presents comes from various fields, including social sciences, medicine, neurobiology, and economics.

Because of its small size, this book is perfect for a weekend away or to read on a plane.

5 & 6. Prefer to listen rather than read?

One of our favorite podcasts is Intelligence2, where leading experts in a particular field gather to debate a particular topic.

This show’s host, Dr. Laurie Santos, argues that we can increase our happiness by not hoarding our money for ourselves but by giving it to others instead. If you are interested in this episode , or any of the other episodes in the Happiness Lab podcast series, then head on over to their page.

There are several resources available at PositivePsychology.com for our readers to use in their professional and personal development.

In this section, you’ll find a few that should supplement any work on happiness and economics. Since the undercurrent of the topic is whether happiness can be improved through wealth, a few resources look at happiness overall.

Valued Living Masterclass

Although knowledge is power, knowing that money does not guarantee happiness does not mean that clients will suddenly feel fulfilled and satisfied with their lives.

For this reason, we recommend the Valued Living Masterclass , for professionals to help their clients find meaning in their lives. Rather than keeping up with the Joneses or chasing a high-paying job, professionals can help their clients connect with their inner meaning (i.e., their why ) as a way to find meaning and gain happiness.

Three free exercises

If you want to try it out before committing, look at the Meaning & Valued Living exercise pack , which includes three exercises for free.

Recommended reading

Read our post on Success Versus Happiness for further information on balancing happiness with success, in any domain . This topic is poignant for readers who conflate happiness and success, and will guide readers to better understand their relationship and how the two terms influence each other.

For readers who wonder about altruism , you would find it interesting that rather than hoarding, you can increase your happiness through volunteering and donating. In this post, the author, Dr. Jeremy Sutton, does a fabulous job of approaching altruism from various fields and provides excellent resources for further reading and real-life application.

Our last recommendation is for readers who want to know more about measuring subjective wellbeing and happiness . The post lists various tests and apps that can measure happiness and the overall history of how happiness was measured and defined. This is a good starting point for researchers or clinicians who want to explore happiness economics professionally.

17 Happines Exercises

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others develop strategies to boost their wellbeing, this collection contains 17 validated happiness and wellbeing exercises . Use them to help others pursue authentic happiness and work toward a life filled with purpose and meaning

17 Exercises To Increase Happiness and Wellbeing

Add these 17 Happiness & Subjective Well-Being Exercises [PDF] to your toolkit and help others experience greater purpose, meaning, and positive emotions.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

As you’ve seen in our article, the evidence overwhelmingly clarifies that money does not guarantee more happiness … well, long-term happiness.

Our happiness is relative since we compare ourselves to other people, and over time, as we become accustomed to our wealth, we lose all the happiness gains we made.

Money can ease financial and social difficulties; consequently, it can drastically improve people’s living conditions, life expectancy, and education.

Improvements in these outcomes have a knock-on effect on the overall experience of one’s life and the opportunities for one’s family and children. Nevertheless, better opportunities do not guarantee happiness.

Our intention with this post was to illustrate some complexities surrounding the relationship between money and happiness.

Knowing that money does not guarantee happiness, we recommend less expensive methods to improve one’s happiness:

- Spend time with friends.

- Cultivate hobbies and interests.

- Stay active and eat healthy.

- Try to live a meaningful life.

- Give some love (go smooch your partner or tickle your dog’s belly).

Diamonds might be a girl’s best friend, but money is a fair weather one, at best.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Happiness Exercises for free .

- Brickman, P., Coates, D., & Janoff-Bulman, R. (1978). Lottery winners and accident victims: Is happiness relative? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 36 (8), 917.

- Bruni, L. (2007). Handbook on the economics of happiness . Edward Elgar.

- Clark, A. E. (2018). Four decades of the economics of happiness: Where next? Review of Income and Wealth , 64 (2), 245–269.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M., Abuhamdeh, S., & Nakamura, J. (2005). Flow. In A. J. Elliot & C. S. Dweck (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 598–608). Guilford Publications.

- Diener, E., Sandvik, E., Seidlitz, L., & Diener, M. (1993). The relationship between income and subjective well-being: Relative or absolute? Social Indicators Research , 28 , 195–223.

- Diener, E., & Oishi, S. (2000). Money and happiness: Income and subjective well-being across nations. Culture and Subjective Well-Being , 185 , 218.

- DiMaria, C. H., Peroni, C., & Sarracino, F. (2020). Happiness matters: Productivity gains from subjective well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies , 21 (1), 139–160.

- Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In P. A. David & M. W. Reder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in honor of Moses Abramovitz (pp. 89–125). Academic Press.

- Easterlin, R. A. (2004). The economics of happiness. Daedalus , 133 (2), 26–33.

- Graham, C. (2005). The economics of happiness. World Economics , 6 (3), 41–55.

- Haesevoets, T., Dierckx, K., & Van Hiel, A. (2022). Do people believe that you can have too much money? The relationship between hypothetical lottery wins and expected happiness. Judgment and Decision Making , 17 (6), 1229–1254.

- Helliwell, J., Layard, R., & Sachs, J. (Eds.) (2012). World happiness report . The Earth Institute, Columbia University.

- Helliwell, J. F., Layard, R., Sachs, J. D., & Neve, J. E. D. (2021). World happiness report 2021 .

- Kahneman, D., Krueger, A. B., Schkade, D., Schwarz, N., & Stone, A. A. (2006). Would you be happier if you were richer? A focusing illusion. Science , 312 (5782), 1908–1910.

- Nettle, D. (2005). Happiness: The science behind your smile . Oxford University Press.

- Sherman, A., Shavit, T., & Barokas, G. (2020). A dynamic model on happiness and exogenous wealth shock: The case of lottery winners. Journal of Happiness Studies , 21 , 117–137.

- Steptoe, A. (2019). Happiness and health. Annual Review of Public Health , 40 , 339–359.

- Veenhoven, R., & Ehrhardt, J. (1995). The cross-national pattern of happiness: Test of predictions implied in three theories of happiness. Social Indicators Research , 34 , 33–68.

Share this article:

Article feedback

Let us know your thoughts cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Embracing JOMO: Finding Joy in Missing Out

We’ve probably all heard of FOMO, or ‘the fear of missing out’. FOMO is the currency of social media platforms, eager to encourage us to [...]

The True Meaning of Hedonism: A Philosophical Perspective

“If it feels good, do it, you only live once”. Hedonists are always up for a good time and believe the pursuit of pleasure and [...]

Hedonic vs. Eudaimonic Wellbeing: How to Reach Happiness

Have you ever toyed with the idea of writing your own obituary? As you are now, young or old, would you say you enjoyed a [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (48)

- Coaching & Application (57)

- Compassion (26)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (24)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (45)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (28)

- Positive Communication (20)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (17)

- Positive Parenting (3)

- Positive Psychology (33)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (16)

- Relationships (46)

- Resilience & Coping (36)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (37)

- Strengths & Virtues (31)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

3 Happiness Exercises Pack [PDF]

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

The Nobel Winner Who Liked to Collaborate With His Adversaries

By Cass R. Sunstein

Mr. Sunstein is a law professor at Harvard and an author of “Noise,” with Daniel Kahneman and Olivier Sibony.

Our all-American belief that money really does buy happiness is roughly correct for about 85 percent of us. We know this thanks to the latest and perhaps final work of Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel Prize winner who insisted on the value of working with those with whom we disagree.

Professor Kahneman, who died last week at the age of 90, is best known for his pathbreaking explorations of human judgment and decision making and of how people deviate from perfect rationality. He should also be remembered for a living and working philosophy that has never been more relevant: his enthusiasm for collaborating with his intellectual adversaries. This enthusiasm was deeply personal. He experienced real joy working with others to discover the truth, even if he learned that he was wrong (something that often delighted him).

Back to that finding, published last year , that for a strong majority of us, more is better when it comes to money. In 2010, Professor Kahneman and the Princeton economist Angus Deaton (also a Nobel Prize winner) published a highly influential essay that found that, on average, higher-income groups show higher levels of happiness — but only to a point. Beyond a threshold at or below $90,000, Professor Kahneman and Professor Deaton found, there is no further progress in average happiness as income increases.

Eleven years later, Matthew Killingsworth, a senior fellow at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, found exactly the opposite : People with higher income reported higher levels of average happiness. Period. The more money people have, the happier they are likely to be.

What gives? You could imagine some furious exchange in which Professor Kahneman and Professor Deaton made sharp objections to Dr. Killingsworth’s paper, to which Dr. Killingsworth answered equally sharply, leaving readers confused and exhausted.

Professor Kahneman saw such a dynamic as “angry science,” which he described as a “nasty world of critiques, replies and rejoinders” and “as a contest, where the aim is to embarrass.” As Professor Kahneman put it, those who live in that nasty world offer “a summary caricature of the target position, refute the weakest argument in that caricature and declare the total destruction of the adversary’s position.” In his account, angry science is “a demeaning experience.” That dynamic might sound familiar, particularly in our politics.

Instead, Professor Kahneman favored an alternative that he termed “adversarial collaboration.” When people who disagree work together to test a hypothesis, they are involved in a common endeavor. They are trying not to win but to figure out what’s true. They might even become friends.

In that spirit, Professor Kahneman, well into his 80s, asked Dr. Killingsworth to collaborate, with the help of a friendly arbiter, Prof. Barbara Mellers, an influential and widely admired psychologist. Their task was to look closely at Dr. Killingsworth’s data to see whether he had analyzed it properly and to understand what, if anything, had been missed by Professor Kahneman and Professor Deaton.

Their central conclusion was simple. Dr. Killingsworth missed a threshold effect in his data that affected only one group: the least happy 15 percent. For these largely unhappy people, average happiness does grow with rising income, up to a level of around $100,000, but it stops growing after that. For a majority of us, by contrast, average happiness keeps growing with increases in income.

Both sides were partly right and partly wrong. Their adversarial collaboration showed that the real story is more interesting and more complicated than anyone saw individually.

Professor Kahneman engaged in a number of adversarial collaborations, with varying degrees of success. His first (and funniest) try was with his wife, the distinguished psychologist Anne Treisman. Their disagreement never did get resolved. (Dr. Treisman died in 2018.) Both of them were able to explain away the results of their experiments — a tribute to what he called “the stubborn persistence of challenged beliefs.” Still, adversarial collaborations sometimes produce both agreement and truth, and he said that “a common feature of all my experiences has been that the adversaries ended up on friendlier terms than they started.”

Professor Kahneman meant both to encourage better science and to strengthen the better angels of our nature. In academic life, adversarial collaborations hold great value . We could easily imagine a situation in which adversaries routinely collaborated to see if they could resolve disputes about the health effects of air pollutants, the consequences of increases in the minimum wage, the harms of climate change or the deterrent effects of the death penalty.

And the idea can be understood more broadly. In fact, the U.S. Constitution should be seen as an effort to create the conditions for adversarial collaboration. Before the founding, it was often thought that republics could work only if people were relatively homogeneous — if they were broadly in agreement with one another. Objecting to the proposed Constitution, the pseudonymous antifederalist Brutus emphasized this point: “In a republic, the manners, sentiments and interests of the people should be similar. If this be not the case, there will be a constant clashing of opinions, and the representatives of one part will be continually striving against those of the other.”

Those who favored the Constitution thought that Brutus had it exactly backward. In their view, the constant clashing of opinions was something not to fear but to welcome, at least if people collaborate — if they act as if they are engaged in a common endeavor. Sounding a lot like Professor Kahneman, Alexander Hamilton put it this way : “The differences of opinion, and the jarrings of parties” in the legislative department of the government “often promote deliberation and circumspection and serve to check excesses in the majority.”

Angry science is paralleled by angry democracy, a “nasty world of critiques, replies and rejoinders,” whose “aim is to embarrass,” Professor Kahneman said. That’s especially true, of course, in the midst of political campaigns, when the whole point is to win.

Still, the idea of adversarial collaboration has never been more important. Within organizations of all kinds — including corporations, nonprofits, think tanks and government agencies — sustained efforts should be made to lower the volume by isolating the points of disagreement and specifying tests to establish what’s right. Asking how a disagreement might actually be resolved tends to turn enemies, focused on winning and losing, into teammates, focused on truth.

As usual, Professor Kahneman was right. We could use a lot more of that.

Cass R. Sunstein is a law professor at Harvard and an author of “Noise,” with Daniel Kahneman and Olivier Sibony.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Instagram , TikTok , WhatsApp , X and Threads .

More Proof That Money Can Buy Happiness (or a Life with Less Stress)

When we wonder whether money can buy happiness, we may consider the luxuries it provides, like expensive dinners and lavish vacations. But cash is key in another important way: It helps people avoid many of the day-to-day hassles that cause stress, new research shows.

Money can provide calm and control, allowing us to buy our way out of unforeseen bumps in the road, whether it’s a small nuisance, like dodging a rainstorm by ordering up an Uber, or a bigger worry, like handling an unexpected hospital bill, says Harvard Business School professor Jon Jachimowicz.

“If we only focus on the happiness that money can bring, I think we are missing something,” says Jachimowicz, an assistant professor of business administration in the Organizational Behavior Unit at HBS. “We also need to think about all of the worries that it can free us from.”

The idea that money can reduce stress in everyday life and make people happier impacts not only the poor, but also more affluent Americans living at the edge of their means in a bumpy economy. Indeed, in 2019, one in every four Americans faced financial scarcity, according to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. The findings are particularly important now, as inflation eats into the ability of many Americans to afford basic necessities like food and gas, and COVID-19 continues to disrupt the job market.

Buying less stress

The inspiration for researching how money alleviates hardships came from advice that Jachimowicz’s father gave him. After years of living as a struggling graduate student, Jachimowicz received his appointment at HBS and the financial stability that came with it.

“My father said to me, ‘You are going to have to learn how to spend money to fix problems.’” The idea stuck with Jachimowicz, causing him to think differently about even the everyday misfortunes that we all face.

To test the relationship between cash and life satisfaction, Jachimowicz and his colleagues from the University of Southern California, Groningen University, and Columbia Business School conducted a series of experiments, which are outlined in a forthcoming paper in the journal Social Psychological and Personality Science , The Sharp Spikes of Poverty: Financial Scarcity Is Related to Higher Levels of Distress Intensity in Daily Life .

Higher income amounts to lower stress

In one study, 522 participants kept a diary for 30 days, tracking daily events and their emotional responses to them. Participants’ incomes in the previous year ranged from less than $10,000 to $150,000 or more. They found:

- Money reduces intense stress: There was no significant difference in how often the participants experienced distressing events—no matter their income, they recorded a similar number of daily frustrations. But those with higher incomes experienced less negative intensity from those events.

- More money brings greater control : Those with higher incomes felt they had more control over negative events and that control reduced their stress. People with ample incomes felt more agency to deal with whatever hassles may arise.

- Higher incomes lead to higher life satisfaction: People with higher incomes were generally more satisfied with their lives.

“It’s not that rich people don’t have problems,” Jachimowicz says, “but having money allows you to fix problems and resolve them more quickly.”

Why cash matters

In another study, researchers presented about 400 participants with daily dilemmas, like finding time to cook meals, getting around in an area with poor public transportation, or working from home among children in tight spaces. They then asked how participants would solve the problem, either using cash to resolve it, or asking friends and family for assistance. The results showed:

- People lean on family and friends regardless of income: Jachimowicz and his colleagues found that there was no difference in how often people suggested turning to friends and family for help—for example, by asking a friend for a ride or asking a family member to help with childcare or dinner.

- Cash is the answer for people with money: The higher a person’s income, however, the more likely they were to suggest money as a solution to a hassle, for example, by calling an Uber or ordering takeout.

While such results might be expected, Jachimowicz says, people may not consider the extent to which the daily hassles we all face create more stress for cash-strapped individuals—or the way a lack of cash may tax social relationships if people are always asking family and friends for help, rather than using their own money to solve a problem.

“The question is, when problems come your way, to what extent do you feel like you can deal with them, that you can walk through life and know everything is going to be OK,” Jachimowicz says.

Breaking the ‘shame spiral’

In another recent paper , Jachimowicz and colleagues found that people experiencing financial difficulties experience shame, which leads them to avoid dealing with their problems and often makes them worse. Such “shame spirals” stem from a perception that people are to blame for their own lack of money, rather than external environmental and societal factors, the research team says.

“We have normalized this idea that when you are poor, it’s your fault and so you should be ashamed of it,” Jachimowicz says. “At the same time, we’ve structured society in a way that makes it really hard on people who are poor.”

For example, Jachimowicz says, public transportation is often inaccessible and expensive, which affects people who can’t afford cars, and tardy policies at work often penalize people on the lowest end of the pay scale. Changing those deeply-engrained structures—and the way many of us think about financial difficulties—is crucial.

After all, society as a whole may feel the ripple effects of the financial hardships some people face, since financial strain is linked with lower job performance, problems with long-term decision-making, and difficulty with meaningful relationships, the research says. Ultimately, Jachimowicz hopes his work can prompt thinking about systemic change.

“People who are poor should feel like they have some control over their lives, too. Why is that a luxury we only afford to rich people?” Jachimowicz says. “We have to structure organizations and institutions to empower everyone.”

[Image: iStockphoto/mihtiander]

Related reading from the Working Knowledge Archives

Selling Out The American Dream

- 24 Jan 2024

Why Boeing’s Problems with the 737 MAX Began More Than 25 Years Ago

- 25 Jan 2022

- Research & Ideas

- 02 Apr 2024

- What Do You Think?

What's Enough to Make Us Happy?

- 17 May 2017

Minorities Who 'Whiten' Job Resumes Get More Interviews

- 25 Feb 2019

How Gender Stereotypes Kill a Woman’s Self-Confidence

- Social Psychology

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Here’s How Money Really Can Buy You Happiness

The following story is excerpted from TIME’s special edition, The Science of Happiness , which is available at Amazon .

“Whoever said money can’t buy happiness isn’t spending it right.” You may remember those Lexus ads from years back, which hijacked this bumper-sticker-ready twist on the conventional wisdom to sell a car so fancy that no one would ever dream of affixing a bumper sticker to it.

What made the ads so intriguing, but also so infuriating, was that they seemed to offer a simple—if rather expensive—solution to a common question: How can you transform the money you work so hard to earn into something approaching the good life? You know that there must be some connection between money and happiness. If there weren’t, you’d be less likely to stay late at work (or even go in at all) or struggle to save money and invest it profitably. But then, why aren’t your lucrative promotion, five-bedroom house and fat 401(k) cheering you up? The relationship between money and happiness, it would appear, is more complicated than you can possibly imagine.

Fortunately, you don’t have to do the untangling yourself. Over the past quarter-century, economists and psychologists have banded together to sort out the hows, whys and why-nots of money and mood. Especially the why-nots. Why is it that the more money you have, the more you want? Why doesn’t buying the car, condo or cellphone of your dreams bring you more than momentary joy?

In attempting to answer these seemingly depressing questions, the new scholars of happiness have arrived at some insights that are, well, downright cheery. Money can help you find more happiness, so long as you know just what you can and can’t expect from it. And no, you don’t have to buy a Lexus to be happy. Much of the research suggests that seeking the good life at a store is an expensive exercise in futility. Before you can pursue happiness the right way, you need to recognize what you’ve been doing wrong.

Money misery

The new science of happiness starts with a simple insight: we’re never satisfied. “We always think if we just had a little bit more money, we’d be happier,” says Catherine Sanderson, a psychology professor at Amherst College, “but when we get there, we’re not.” Indeed, the more you make, the more you want. The more you have, the less effective it is at bringing you joy, and that seeming paradox has long bedeviled economists. “Once you get basic human needs met, a lot more money doesn’t make a lot more happiness,” notes Dan Gilbert, a psychology professor at Harvard University and the author of Stumbling on Happiness . Some research shows that going from earning less than $20,000 a year to making more than $50,000 makes you twice as likely to be happy, yet the payoff for then surpassing $90,000 is slight. And while the rich are happier than the poor, the enormous rise in living standards over the past 50 years hasn’t made Americans happier. Why? Three reasons:

You overestimate how much pleasure you’ll get from having more. Humans are adaptable creatures, which has been a plus during assorted ice ages, plagues and wars. But that’s also why you’re never all that satisfied for long when good fortune comes your way. While earning more makes you happy in the short term, you quickly adjust to your new wealth—and everything it buys you. Yes, you get a thrill at first from shiny new cars and TV screens the size of Picasso’s Guernica . But you soon get used to them, a state of running in place that economists call the “hedonic treadmill” or “hedonic adaptation.”

Even though stuff seldom brings you the satisfaction you expect, you keep returning to the mall and the car dealership in search of more. “When you imagine how much you’re going to enjoy a Porsche, what you’re imagining is the day you get it,” says Gilbert. When your new car loses its ability to make your heart go pitter-patter, he says, you tend to draw the wrong conclusions. Instead of questioning the notion that you can buy happiness on the car lot, you begin to question your choice of car. So you pin your hopes on a new BMW, only to be disappointed again.

More money can also lead to more stress. The big salary you pull in from your high-paying job may not buy you much in the way of happiness. But it can buy you a spacious house in the suburbs. Trouble is, that also means a long trip to and from work, and study after study confirms what you sense daily: even if you love your job, the little slice of everyday hell you call the commute can wear you down. You can adjust to most anything, but a stop-and-go drive or an overstuffed subway car will make you unhappy whether it’s your first day on the job or your last.

You endlessly compare yourself with the family next door. H.L. Mencken once quipped that the happy man is one who earns $100 more than his wife’s sister’s husband. He was right. Happiness scholars have found that how you stand relative to others makes a much bigger difference in your sense of well-being than how much you make in an absolute sense.

You may feel a touch of envy when you read about the glamorous lives of the absurdly wealthy, but the group you likely compare yourself with are folks Dartmouth economist Erzo Luttmer calls “similar others”—the people you work with, people you grew up with, old friends and old classmates. “You have to think, ‘I could have been that person,’ ” Luttmer says.

Matching census data on earnings with data on self-reported happiness from a national survey, Luttmer found that, sure enough, your happiness can depend a great deal on your neighbors’ paychecks. “If you compare two people with the same income, with one living in a richer area than the other,” Luttmer says, “the person in the richer area reports being less happy.”

Your penchant for comparing yourself with the guy next door, like your tendency to grow bored with the things that you acquire, seems to be a deeply rooted human trait. An inability to stay satisfied is arguably one of the key reasons prehistoric man moved out of his drafty cave and began building the civilization you now inhabit. But you’re not living in a cave, and you likely don’t have to worry about mere survival. You can afford to step off the hedonic treadmill. The question is, how do you do it?

Money bliss

If you want to know how to use the money you have to become happier, you need to understand just what it is that brings you happiness in the first place. And that’s where the newest happiness research comes in.

Friends and family are a mighty elixir. One secret of happiness? People. Innumerable studies suggest that having friends matters a great deal. Large-scale surveys by the University of Chicago’s National Opinion Research Center (NORC), for example, have found that those with five or more close friends are 50% more likely to describe themselves as “very happy” than those with smaller social circles. Compared with the happiness-increasing powers of human connection, the power of money looks feeble indeed. So throw a party, set up regular lunch dates—whatever it takes to invest in your friendships.

Even more important to your happiness is your relationship with your aptly named “significant other.” People in happy, stable, committed relationships tend to be far happier than those who aren’t. Among those surveyed by NORC from the 1970s through the 1990s, some 40% of married couples said they were “very happy”; among the never-married, only about a quarter were quite so exuberant. But there is good reason to choose wisely. Divorce brings misery to everyone involved, though those who stick it out in a terrible marriage are the unhappiest of all.

While a healthy marriage is a clear happiness booster, the kids who tend to follow are more of a mixed blessing. Studies of kids and happiness have come up with little more than a mess of conflicting data. “When you take moment-by-moment readouts of how people feel when they’re taking care of the kids, they actually aren’t very happy,” notes Cornell University psychologist Tom Gilovich. “But if you ask them, they say that having kids is one of the most enjoyable things they do with their lives.”

Doing things can bring us more joy than having things. Our preoccupation with stuff obscures an important truth: the things that don’t last create the most lasting happiness. That’s what Gilovich and Leaf Van Boven of the University of Colorado found when they asked students to compare the pleasure they got from the most recent things they bought with the experiences (a night out, a vacation) they spent money on.

One reason may be that experiences tend to blossom as you recall them, not diminish. “In your memory, you’re free to embellish and elaborate,” says Gilovich. Your trip to Mexico may have been an endless parade of hassles punctuated by a few exquisite moments. But looking back on it, your brain can edit out the surly cabdrivers, remembering only the glorious sunsets. So next time you think that arranging a vacation is more trouble than it’s worth—or a cost you’d rather not shoulder—factor in the delayed impact.

Of course, a lot of what you spend money on could be considered a thing, an experience or a bit of both. A book that sits unread on a bookshelf is a thing; a book you plunge into with gusto, savoring every plot twist, is an experience. Gilovich says that people define what is and isn’t an experience differently. Maybe that’s the key. He suspects that the people who are happiest are those who are best at wringing experiences out of everything they spend money on, whether it’s dancing lessons or hiking boots.

Applying yourself to something hard makes you happy. We’re addicted to challenges, and we’re often far happier while working toward a goal than after we reach it. Challenges help you attain what psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi calls a state of “flow”: total absorption in something that stretches you to the limits of your abilities, mental or physical. Buy the $1,000 golf clubs; pay for the $50-an-hour music lessons.

Most Popular from TIME

Flow takes work.

After all, you have to learn to play scales on a guitar before you can lose yourself in a Van Halen–esque solo—but the satisfaction you get in the end is greater than what you can get out of more passive pursuits. When people are asked what makes them happy on a moment-to-moment basis, watching TV ranks pretty high. But people who watch a lot of TV tend to be less happy than those who don’t. Settling down on the couch with the remote can help you recharge, but to be truly happy, you need more in your life than passive pleasures.

You need to find activities that help you get into the state of flow. You can find flow at work if you have a job that interests and challenges you and that gives you ample control over your daily assignments. Indeed, one study by two University of British Columbia researchers suggests that workers would be happy to forgo as much as a 20% raise if it meant having a job with more variety.

Not long ago, most researchers thought you had a happiness set point that you were largely stuck with for life. One famous paper said that “trying to be happier” may be “as futile as trying to be taller.” The author of those words has since recanted, and experts are increasingly coming to view happiness as a talent, not an inborn trait. Exceptionally happy people seem to have a set of skills—ones that you too can learn.

Sonja Lyubomirsky, a psychology professor at the University of California, Riverside, has found that happy people don’t waste time dwelling on unpleasant things. They tend to interpret ambiguous events in positive ways. And perhaps most tellingly, they aren’t bothered by the successes of others. Lyubomirsky says that when she asked less-happy people whom they compared themselves with, “they went on and on.” She adds, “The happy people didn’t know what we were talking about.” They dare not to compare, thus short-circuiting invidious social comparisons.

That’s not the only way to get yourself to spend less and appreciate what you have more. Try counting your blessings. Literally. In a series of studies, psychologists Robert Emmons of the University of California, Davis, and Michael McCullough of the University of Miami found that those who did exercises to cultivate feelings of gratitude, such as keeping weekly journals, ended up feeling happier, healthier, more energetic and more optimistic than those who didn’t.

And if you can’t change how you think, you can at least learn to resist. The act of shopping unleashes primal hunter-gatherer urges. When you’re in that hot state, you tend to be an extremely poor judge of what you’ll think of a product when you cool down later. Before giving in to your lust, give yourself a time-out. Over the next month, keep track of how many times you tell yourself: I wish I had a camera! If in the course of your life you almost never find yourself wanting a camera, forget about it and move on, happily.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Jane Fonda Champions Climate Action for Every Generation

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

You May Also Like

One More Time, Does Money Buy Happiness?

- Published: 19 September 2023

- Volume 18 , pages 3089–3110, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- James Fisher ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9201-4204 1 &

- Michael Frechette ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8193-6796 2

1110 Accesses

Explore all metrics

This paper integrates multiple positions on the relationship between money and well-being, commonly referred to as happiness. An aggregation of prior work appears to suggest that money does buy happiness, but not directly. Although many personal and situational characteristics do influence the relationship between money and happiness, most are moderating factors, which would not necessarily rule out a direct link. Here, we discuss the cognitive and affective elements within the formation of happiness, which we propose play a series of mediating roles, first cognition, then affect, between money and happiness. The paper concludes with a discussion about how this proposal influences academic research and society as a whole.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The Functional and Dysfunctional Aspects of Happiness: Cognitive, Physiological, Behavioral, and Health Considerations

Happiness, Economics of

What We Have Learnt About Happiness

Materials and/or code availability.

There are no materials or code related to this manuscript.

Data Availability

This conceptual study collected no original data. Citations are given to the original sources when referencing data or results from prior studies.

“As far as I am aware, in every representative national survey ever done a significant positive bivariate relationship between happiness and income has been found.” (Easterlin 2001 , 468). Easterlin supports this assertion with references to Andrews 1996 , xi; Argyle 1999 , 356–57; and Diener 1984 , 553.

A simple correlation of 0.2 is an oft-cited benchmark (cf. Easterlin 2001 , who labels it “highly significant”). At the same time, many researchers qualify the relationship, saying that income ultimately explains relatively little of the variance in self-reports of happiness: e.g., Ahuvia ( 2017 , 18) generalizes that “typically studies in developed economies indicate that income explains only about 3% of the difference in happiness.” Some twenty years prior to Ahuvia’s assessment, Frank ( 1997 ) offered a similar conclusion: the relationship between income and happiness is closer at lower levels of income than for middle- or upper-income households, where "variations in income explain less than 2% of variations in reported satisfaction levels” (citing Diener and Diener 1995 on 1835). Diener and Biswas-Diener ( 2002 , 123) summarize over a dozen correlations between income and subjective well-being, most ranging between 0.15 and 0.25. Kahneman and Deaton ( 2010 ) recommend that efforts to estimate the relationship between that subjective well-being and income should rely on a logarithmic transformation of income, providing a rationale based on Weber’s Law, having to do with the perception of change reflecting the percentage change and not the absolute change.

This literature review reflects the authors’ point-of-view that in answering the question of “how” money buys happiness economists have offered the highest-level, abstract answer (i.e., through a process of utility-maximization); psychologists and researchers into subjective well-being have sought a more precise accounting of what money buys vis-à-vis individual dispositions (e.g., personality) and motivations (e.g., materialism) as well as cultural or national determinants (e.g., individualism versus collectivism); and marketers and consumer researchers have inquired in the most detailed way as to how money delivers particular experiences and effects throughout the continuum of pre-purchase processes, the experience of consumption and post-purchase satisfaction.

Happiness data are a relative late-comers to economic analyses of this sort: “[T]he approach departs from a long tradition in economics that shies away from using what people say about their feelings. Instead, economists have built their trade by analyzing what people do and, from these observations and some theoretical assumptions about the structure of welfare, deducing the implied changes in happiness” (Di Tella and MacCulloch 2006 , 43). Kahneman and Krueger ( 2006 , 3) express a similar opinion: “[E]conomists have had a long-standing preference for studying peoples’ revealed preferences; that is, looking at individuals’ actual choices and decisions rather than their stated intentions or subjective reports of likes and dislikes.”.

An assertion strenuously challenged by Diener and Oishi 2000 and more modestly objected to by Frank ( 1997 , 1820), who interprets the data to say that there “is only slight evidence … that greater economic prosperity leads to more well-being in a nation.”.

Cummins ( 2000 ), in his review of personal income and subjective well-being, constructs a couple of straw men that reflect his estimation of how researchers into quality of life may view income ambivalently. At the outset of the review article, his abstract announces, "Conventional wisdom holds that money has little relevance to happiness." Later in the same review article, he identifies a bias "that can quite commonly be found within the QOL literature" (p. 139) that the rich are not as satisfied with their lot as commonly imagined. Chambers ( 1997 ) provides him with a suitable proof text in which "the link between wealth and well-being is weak or even negative" and therefore, "amassing wealth does not assure well-being and may diminish it” (at 1728 in Chambers). Cummins himself disavows this disciplinary tendency, ultimately labeling it “fanciful.”.

When it comes to terms like subjective well-being, life satisfaction, and happiness, there is some variation in the precision of the terminology. Thus, Kahneman and Krueger ( 2006 ) use life satisfaction and happiness as roughly synonymous in discussing the measurement of well-being and in emphasizing the measurement of emotional states. On the other hand, Diener may commonly use the term happiness as a convenient and widely used construct but will employ more precision in measuring or analyzing "types of well-being.".

E.g., basic needs met, psychological needs met, and satisfaction with living standards in Diener, Ng, Harter and Arora ( 2010 , 56).

E.g., pleasant affect, unpleasant affect, life satisfaction, and domain satisfaction in Diener, Suh, Lucas and Smith ( 1999 , 277).

Dunn et al. ( 2011 ) stake out this position with their article’s title “If money doesn’t make you happy, then you probably aren’t spending it right.”.

Thus, Scitovsky’s title, The Joyless Economy .

Actually, it is nice to be rich. (2023, March 24). The Week , 33.

Ahuvia, A. C. (2017). Consumption, Income and Happiness. In Alan Lewis (Ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of Psychology and Economic Behaviour, Cambridge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Google Scholar

Allcott, H., Braghieri, L., Eichmeyer, S., & Gentzkow, M. (2020). The welfare effects of social media. American Economic Review, 110 (3), 629–676.

Article Google Scholar

Andrews, F. (1996). Editor’s introduction. In F. Andrews (Ed.), Research on the Quality of Life (pp. ix–xiv). University of Michigan.

Argyle, M. (1999). 'Causes and correlates of happiness,' in (D. Kahneman, E. Diener, and N. Schwarz eds.), Well-Being: The Foundations of Hedonic Psychology , (pp. 353–73). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Auerbach, A. J., Kotlikoff, L. J., & Koehler, D. (2016). US Inequality and Fiscal Progressivity: An Intragenerational Accounting. Available at SSRN 2747187 .

Bradburn, N. M. (1969). The structure of psychological well-being . Aldine.

Bradburn, N. M., & Caplovitz, D. (1965). Reports on Happiness: A Pilot Study of Behavior Related to Mental Health . Aldine Publishing Company.

Bryson, A., & MacKerron, G. (2017). Are you happy while you work? The Economic Journal, 127 (599), 106–125.

Brzozowski, M., & Spotton Visano, B. (2020). Havin’ money’s not everything, not havin’ it is: The importance of financial satisfaction for life satisfaction in financially stressed households. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21 (2), 573–591.

Cantril, H. (1965). The pattern of human concerns . Rutgers University Press.

Chambers, R. (1997). Responsible well-being—A personal agenda for development. World Development, 25 (11), 1743–1754.

Clark, A. E., Frijters, P., & Shields, M. A. (2008). Relative income, happiness, and utility: An explanation for the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles. Journal of Economic literature , 46 (1), 95–144.

Coy, P. (2022, July 18) There’s a Better Way to Measure Economic Inequality: Differences in wealth or income are not good gauges. New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/07/18/opinion/economic-inequality-spending-power.html?searchResultPosition=39 .

Cummins, R. A. (2000). Personal income and subjective well-being: A review. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1 , 133–158.

Di Tella, R., & MacCulloch, R. (2006). Some uses of happiness data in economics. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20 (1), 25–46.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95 (3), 542–575.