An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Case study: 33-year-old female presents with chronic sob and cough.

Sandeep Sharma ; Muhammad F. Hashmi ; Deepa Rawat .

Affiliations

Last Update: February 20, 2023 .

- Case Presentation

History of Present Illness: A 33-year-old white female presents after admission to the general medical/surgical hospital ward with a chief complaint of shortness of breath on exertion. She reports that she was seen for similar symptoms previously at her primary care physician’s office six months ago. At that time, she was diagnosed with acute bronchitis and treated with bronchodilators, empiric antibiotics, and a short course oral steroid taper. This management did not improve her symptoms, and she has gradually worsened over six months. She reports a 20-pound (9 kg) intentional weight loss over the past year. She denies camping, spelunking, or hunting activities. She denies any sick contacts. A brief review of systems is negative for fever, night sweats, palpitations, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, abdominal pain, neural sensation changes, muscular changes, and increased bruising or bleeding. She admits a cough, shortness of breath, and shortness of breath on exertion.

Social History: Her tobacco use is 33 pack-years; however, she quit smoking shortly prior to the onset of symptoms, six months ago. She denies alcohol and illicit drug use. She is in a married, monogamous relationship and has three children aged 15 months to 5 years. She is employed in a cookie bakery. She has two pet doves. She traveled to Mexico for a one-week vacation one year ago.

Allergies: No known medicine, food, or environmental allergies.

Past Medical History: Hypertension

Past Surgical History: Cholecystectomy

Medications: Lisinopril 10 mg by mouth every day

Physical Exam:

Vitals: Temperature, 97.8 F; heart rate 88; respiratory rate, 22; blood pressure 130/86; body mass index, 28

General: She is well appearing but anxious, a pleasant female lying on a hospital stretcher. She is conversing freely, with respiratory distress causing her to stop mid-sentence.

Respiratory: She has diffuse rales and mild wheezing; tachypneic.

Cardiovascular: She has a regular rate and rhythm with no murmurs, rubs, or gallops.

Gastrointestinal: Bowel sounds X4. No bruits or pulsatile mass.

- Initial Evaluation

Laboratory Studies: Initial work-up from the emergency department revealed pancytopenia with a platelet count of 74,000 per mm3; hemoglobin, 8.3 g per and mild transaminase elevation, AST 90 and ALT 112. Blood cultures were drawn and currently negative for bacterial growth or Gram staining.

Chest X-ray

Impression: Mild interstitial pneumonitis

- Differential Diagnosis

- Aspiration pneumonitis and pneumonia

- Bacterial pneumonia

- Immunodeficiency state and Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia

- Carcinoid lung tumors

- Tuberculosis

- Viral pneumonia

- Chlamydial pneumonia

- Coccidioidomycosis and valley fever

- Recurrent Legionella pneumonia

- Mediastinal cysts

- Mediastinal lymphoma

- Recurrent mycoplasma infection

- Pancoast syndrome

- Pneumococcal infection

- Sarcoidosis

- Small cell lung cancer

- Aspergillosis

- Blastomycosis

- Histoplasmosis

- Actinomycosis

- Confirmatory Evaluation

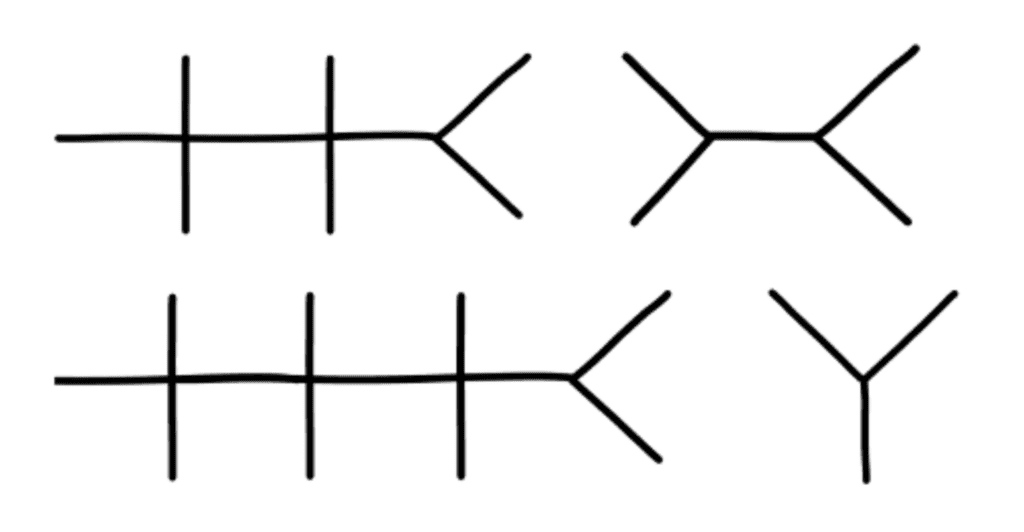

CT of the chest was performed to further the pulmonary diagnosis; it showed a diffuse centrilobular micronodular pattern without focal consolidation.

On finding pulmonary consolidation on the CT of the chest, a pulmonary consultation was obtained. Further history was taken, which revealed that she has two pet doves. As this was her third day of broad-spectrum antibiotics for a bacterial infection and she was not getting better, it was decided to perform diagnostic bronchoscopy of the lungs with bronchoalveolar lavage to look for any atypical or rare infections and to rule out malignancy (Image 1).

Bronchoalveolar lavage returned with a fluid that was cloudy and muddy in appearance. There was no bleeding. Cytology showed Histoplasma capsulatum .

Based on the bronchoscopic findings, a diagnosis of acute pulmonary histoplasmosis in an immunocompetent patient was made.

Pulmonary histoplasmosis in asymptomatic patients is self-resolving and requires no treatment. However, once symptoms develop, such as in our above patient, a decision to treat needs to be made. In mild, tolerable cases, no treatment other than close monitoring is necessary. However, once symptoms progress to moderate or severe, or if they are prolonged for greater than four weeks, treatment with itraconazole is indicated. The anticipated duration is 6 to 12 weeks total. The response should be monitored with a chest x-ray. Furthermore, observation for recurrence is necessary for several years following the diagnosis. If the illness is determined to be severe or does not respond to itraconazole, amphotericin B should be initiated for a minimum of 2 weeks, but up to 1 year. Cotreatment with methylprednisolone is indicated to improve pulmonary compliance and reduce inflammation, thus improving work of respiration. [1] [2] [3]

Histoplasmosis, also known as Darling disease, Ohio valley disease, reticuloendotheliosis, caver's disease, and spelunker's lung, is a disease caused by the dimorphic fungi Histoplasma capsulatum native to the Ohio, Missouri, and Mississippi River valleys of the United States. The two phases of Histoplasma are the mycelial phase and the yeast phase.

Etiology/Pathophysiology

Histoplasmosis is caused by inhaling the microconidia of Histoplasma spp. fungus into the lungs. The mycelial phase is present at ambient temperature in the environment, and upon exposure to 37 C, such as in a host’s lungs, it changes into budding yeast cells. This transition is an important determinant in the establishment of infection. Inhalation from soil is a major route of transmission leading to infection. Human-to-human transmission has not been reported. Infected individuals may harbor many yeast-forming colonies chronically, which remain viable for years after initial inoculation. The finding that individuals who have moved or traveled from endemic to non-endemic areas may exhibit a reactivated infection after many months to years supports this long-term viability. However, the precise mechanism of reactivation in chronic carriers remains unknown.

Infection ranges from an asymptomatic illness to a life-threatening disease, depending on the host’s immunological status, fungal inoculum size, and other factors. Histoplasma spp. have grown particularly well in organic matter enriched with bird or bat excrement, leading to the association that spelunking in bat-feces-rich caves increases the risk of infection. Likewise, ownership of pet birds increases the rate of inoculation. In our case, the patient did travel outside of Nebraska within the last year and owned two birds; these are her primary increased risk factors. [4]

Non-immunocompromised patients present with a self-limited respiratory infection. However, the infection in immunocompromised hosts disseminated histoplasmosis progresses very aggressively. Within a few days, histoplasmosis can reach a fatality rate of 100% if not treated aggressively and appropriately. Pulmonary histoplasmosis may progress to a systemic infection. Like its pulmonary counterpart, the disseminated infection is related to exposure to soil containing infectious yeast. The disseminated disease progresses more slowly in immunocompetent hosts compared to immunocompromised hosts. However, if the infection is not treated, fatality rates are similar. The pathophysiology for disseminated disease is that once inhaled, Histoplasma yeast are ingested by macrophages. The macrophages travel into the lymphatic system where the disease, if not contained, spreads to different organs in a linear fashion following the lymphatic system and ultimately into the systemic circulation. Once this occurs, a full spectrum of disease is possible. Inside the macrophage, this fungus is contained in a phagosome. It requires thiamine for continued development and growth and will consume systemic thiamine. In immunocompetent hosts, strong cellular immunity, including macrophages, epithelial, and lymphocytes, surround the yeast buds to keep infection localized. Eventually, it will become calcified as granulomatous tissue. In immunocompromised hosts, the organisms disseminate to the reticuloendothelial system, leading to progressive disseminated histoplasmosis. [5] [6]

Symptoms of infection typically begin to show within three to17 days. Immunocompetent individuals often have clinically silent manifestations with no apparent ill effects. The acute phase of infection presents as nonspecific respiratory symptoms, including cough and flu. A chest x-ray is read as normal in 40% to 70% of cases. Chronic infection can resemble tuberculosis with granulomatous changes or cavitation. The disseminated illness can lead to hepatosplenomegaly, adrenal enlargement, and lymphadenopathy. The infected sites usually calcify as they heal. Histoplasmosis is one of the most common causes of mediastinitis. Presentation of the disease may vary as any other organ in the body may be affected by the disseminated infection. [7]

The clinical presentation of the disease has a wide-spectrum presentation which makes diagnosis difficult. The mild pulmonary illness may appear as a flu-like illness. The severe form includes chronic pulmonary manifestation, which may occur in the presence of underlying lung disease. The disseminated form is characterized by the spread of the organism to extrapulmonary sites with proportional findings on imaging or laboratory studies. The Gold standard for establishing the diagnosis of histoplasmosis is through culturing the organism. However, diagnosis can be established by histological analysis of samples containing the organism taken from infected organs. It can be diagnosed by antigen detection in blood or urine, PCR, or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The diagnosis also can be made by testing for antibodies again the fungus. [8]

Pulmonary histoplasmosis in asymptomatic patients is self-resolving and requires no treatment. However, once symptoms develop, such as in our above patient, a decision to treat needs to be made. In mild, tolerable cases, no treatment other than close monitoring is necessary. However, once symptoms progress to moderate or severe or if they are prolonged for greater than four weeks, treatment with itraconazole is indicated. The anticipated duration is 6 to 12 weeks. The patient's response should be monitored with a chest x-ray. Furthermore, observation for recurrence is necessary for several years following the diagnosis. If the illness is determined to be severe or does not respond to itraconazole, amphotericin B should be initiated for a minimum of 2 weeks, but up to 1 year. Cotreatment with methylprednisolone is indicated to improve pulmonary compliance and reduce inflammation, thus improving the work of respiration.

The disseminated disease requires similar systemic antifungal therapy to pulmonary infection. Additionally, procedural intervention may be necessary, depending on the site of dissemination, to include thoracentesis, pericardiocentesis, or abdominocentesis. Ocular involvement requires steroid treatment additions and necessitates ophthalmology consultation. In pericarditis patients, antifungals are contraindicated because the subsequent inflammatory reaction from therapy would worsen pericarditis.

Patients may necessitate intensive care unit placement dependent on their respiratory status, as they may pose a risk for rapid decompensation. Should this occur, respiratory support is necessary, including non-invasive BiPAP or invasive mechanical intubation. Surgical interventions are rarely warranted; however, bronchoscopy is useful as both a diagnostic measure to collect sputum samples from the lung and therapeutic to clear excess secretions from the alveoli. Patients are at risk for developing a coexistent bacterial infection, and appropriate antibiotics should be considered after 2 to 4 months of known infection if symptoms are still present. [9]

Prognosis

If not treated appropriately and in a timely fashion, the disease can be fatal, and complications will arise, such as recurrent pneumonia leading to respiratory failure, superior vena cava syndrome, fibrosing mediastinitis, pulmonary vessel obstruction leading to pulmonary hypertension and right-sided heart failure, and progressive fibrosis of lymph nodes. Acute pulmonary histoplasmosis usually has a good outcome on symptomatic therapy alone, with 90% of patients being asymptomatic. Disseminated histoplasmosis, if untreated, results in death within 2 to 24 months. Overall, there is a relapse rate of 50% in acute disseminated histoplasmosis. In chronic treatment, however, this relapse rate decreases to 10% to 20%. Death is imminent without treatment.

- Pearls of Wisdom

While illnesses such as pneumonia are more prevalent, it is important to keep in mind that more rare diseases are always possible. Keeping in mind that every infiltrates on a chest X-ray or chest CT is not guaranteed to be simple pneumonia. Key information to remember is that if the patient is not improving under optimal therapy for a condition, the working diagnosis is either wrong or the treatment modality chosen by the physician is wrong and should be adjusted. When this occurs, it is essential to collect a more detailed history and refer the patient for appropriate consultation with a pulmonologist or infectious disease specialist. Doing so, in this case, yielded workup with bronchoalveolar lavage and microscopic evaluation. Microscopy is invaluable for definitively diagnosing a pulmonary consolidation as exemplified here where the results showed small, budding, intracellular yeast in tissue sized 2 to 5 microns that were readily apparent on hematoxylin and eosin staining and minimal, normal flora bacterial growth.

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

This case demonstrates how all interprofessional healthcare team members need to be involved in arriving at a correct diagnosis. Clinicians, specialists, nurses, pharmacists, laboratory technicians all bear responsibility for carrying out the duties pertaining to their particular discipline and sharing any findings with all team members. An incorrect diagnosis will almost inevitably lead to incorrect treatment, so coordinated activity, open communication, and empowerment to voice concerns are all part of the dynamic that needs to drive such cases so patients will attain the best possible outcomes.

- Review Questions

- Access free multiple choice questions on this topic.

- Comment on this article.

Histoplasma Contributed by Sandeep Sharma, MD

Disclosure: Sandeep Sharma declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Muhammad Hashmi declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

Disclosure: Deepa Rawat declares no relevant financial relationships with ineligible companies.

This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ), which permits others to distribute the work, provided that the article is not altered or used commercially. You are not required to obtain permission to distribute this article, provided that you credit the author and journal.

- Cite this Page Sharma S, Hashmi MF, Rawat D. Case Study: 33-Year-Old Female Presents with Chronic SOB and Cough. [Updated 2023 Feb 20]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

In this Page

Bulk download.

- Bulk download StatPearls data from FTP

Similar articles in PubMed

- Review Palliative Chemotherapy: Does It Only Provide False Hope? The Role of Palliative Care in a Young Patient With Newly Diagnosed Metastatic Adenocarcinoma. [J Adv Pract Oncol. 2017] Review Palliative Chemotherapy: Does It Only Provide False Hope? The Role of Palliative Care in a Young Patient With Newly Diagnosed Metastatic Adenocarcinoma. Doverspike L, Kurtz S, Selvaggi K. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2017 May-Jun; 8(4):382-386. Epub 2017 May 1.

- Review Breathlessness with pulmonary metastases: a multimodal approach. [J Adv Pract Oncol. 2013] Review Breathlessness with pulmonary metastases: a multimodal approach. Brant JM. J Adv Pract Oncol. 2013 Nov; 4(6):415-22.

- A 50-Year Old Woman With Recurrent Right-Sided Chest Pain. [Chest. 2022] A 50-Year Old Woman With Recurrent Right-Sided Chest Pain. Saha BK, Bonnier A, Chong WH, Chenna P. Chest. 2022 Feb; 161(2):e85-e89.

- Suicidal Ideation. [StatPearls. 2024] Suicidal Ideation. Harmer B, Lee S, Duong TVH, Saadabadi A. StatPearls. 2024 Jan

- Review Domperidone. [Drugs and Lactation Database (...] Review Domperidone. . Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006

Recent Activity

- Case Study: 33-Year-Old Female Presents with Chronic SOB and Cough - StatPearls Case Study: 33-Year-Old Female Presents with Chronic SOB and Cough - StatPearls

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to present patient...

How to present patient cases

- Related content

- Peer review

- Mary Ni Lochlainn , foundation year 2 doctor 1 ,

- Ibrahim Balogun , healthcare of older people/stroke medicine consultant 1

- 1 East Kent Foundation Trust, UK

A guide on how to structure a case presentation

This article contains...

-History of presenting problem

-Medical and surgical history

-Drugs, including allergies to drugs

-Family history

-Social history

-Review of systems

-Findings on examination, including vital signs and observations

-Differential diagnosis/impression

-Investigations

-Management

Presenting patient cases is a key part of everyday clinical practice. A well delivered presentation has the potential to facilitate patient care and improve efficiency on ward rounds, as well as a means of teaching and assessing clinical competence. 1

The purpose of a case presentation is to communicate your diagnostic reasoning to the listener, so that he or she has a clear picture of the patient’s condition and further management can be planned accordingly. 2 To give a high quality presentation you need to take a thorough history. Consultants make decisions about patient care based on information presented to them by junior members of the team, so the importance of accurately presenting your patient cannot be overemphasised.

As a medical student, you are likely to be asked to present in numerous settings. A formal case presentation may take place at a teaching session or even at a conference or scientific meeting. These presentations are usually thorough and have an accompanying PowerPoint presentation or poster. More often, case presentations take place on the wards or over the phone and tend to be brief, using only memory or short, handwritten notes as an aid.

Everyone has their own presenting style, and the context of the presentation will determine how much detail you need to put in. You should anticipate what information your senior colleagues will need to know about the patient’s history and the care he or she has received since admission, to enable them to make further management decisions. In this article, I use a fictitious case to show how you can structure case presentations, which can be adapted to different clinical and teaching settings (box 1).

Box 1: Structure for presenting patient cases

Presenting problem, history of presenting problem, medical and surgical history.

Drugs, including allergies to drugs

Family history

Social history, review of systems.

Findings on examination, including vital signs and observations

Differential diagnosis/impression

Investigations

Case: tom murphy.

You should start with a sentence that includes the patient’s name, sex (Mr/Ms), age, and presenting symptoms. In your presentation, you may want to include the patient’s main diagnosis if known—for example, “admitted with shortness of breath on a background of COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease].” You should include any additional information that might give the presentation of symptoms further context, such as the patient’s profession, ethnic origin, recent travel, or chronic conditions.

“ Mr Tom Murphy is a 56 year old ex-smoker admitted with sudden onset central crushing chest pain that radiated down his left arm.”

In this section you should expand on the presenting problem. Use the SOCRATES mnemonic to help describe the pain (see box 2). If the patient has multiple problems, describe each in turn, covering one system at a time.

Box 2: SOCRATES—mnemonic for pain

Associations

Time course

Exacerbating/relieving factors

“ The pain started suddenly at 1 pm, when Mr Murphy was at his desk. The pain was dull in nature, and radiated down his left arm. He experienced shortness of breath and felt sweaty and clammy. His colleague phoned an ambulance. He rated the pain 9/10 in severity. In the ambulance he was given GTN [glyceryl trinitrate] spray under the tongue, which relieved the pain to 5/10. The pain lasted 30 minutes in total. No exacerbating factors were noted. Of note: Mr Murphy is an ex-smoker with a 20 pack year history”

Some patients have multiple comorbidities, and the most life threatening conditions should be mentioned first. They can also be categorised by organ system—for example, “has a long history of cardiovascular disease, having had a stroke, two TIAs [transient ischaemic attacks], and previous ACS [acute coronary syndrome].” For some conditions it can be worth stating whether a general practitioner or a specialist manages it, as this gives an indication of its severity.

In a surgical case, colleagues will be interested in exercise tolerance and any comorbidity that could affect the patient’s fitness for surgery and anaesthesia. If the patient has had any previous surgical procedures, mention whether there were any complications or reactions to anaesthesia.

“Mr Murphy has a history of type 2 diabetes, well controlled on metformin. He also has hypertension, managed with ramipril, and gout. Of note: he has no history of ischaemic heart disease (relevant negative) (see box 3).”

Box 3: Relevant negatives

Mention any relevant negatives that will help narrow down the differential diagnosis or could be important in the management of the patient, 3 such as any risk factors you know for the condition and any associations that you are aware of. For example, if the differential diagnosis includes a condition that you know can be hereditary, a relevant negative could be the lack of a family history. If the differential diagnosis includes cardiovascular disease, mention the cardiovascular risk factors such as body mass index, smoking, and high cholesterol.

Highlight any recent changes to the patient’s drugs because these could be a factor in the presenting problem. Mention any allergies to drugs or the patient’s non-compliance to a previously prescribed drug regimen.

To link the medical history and the drugs you might comment on them together, either here or in the medical history. “Mrs Walsh’s drugs include regular azathioprine for her rheumatoid arthritis.”Or, “His regular drugs are ramipril 5 mg once a day, metformin 1g three times a day, and allopurinol 200 mg once a day. He has no known drug allergies.”

If the family history is unrelated to the presenting problem, it is sufficient to say “no relevant family history noted.” For hereditary conditions more detail is needed.

“ Mr Murphy’s father experienced a fatal myocardial infarction aged 50.”

Social history should include the patient’s occupation; their smoking, alcohol, and illicit drug status; who they live with; their relationship status; and their sexual history, baseline mobility, and travel history. In an older patient, more detail is usually required, including whether or not they have carers, how often the carers help, and if they need to use walking aids.

“He works as an accountant and is an ex-smoker since five years ago with a 20 pack year history. He drinks about 14 units of alcohol a week. He denies any illicit drug use. He lives with his wife in a two storey house and is independent in all activities of daily living.”

Do not dwell on this section. If something comes up that is relevant to the presenting problem, it should be mentioned in the history of the presenting problem rather than here.

“Systems review showed long standing occasional lower back pain, responsive to paracetamol.”

Findings on examination

Initially, it can be useful to practise presenting the full examination to make sure you don’t leave anything out, but it is rare that you would need to present all the normal findings. Instead, focus on the most important main findings and any abnormalities.

“On examination the patient was comfortable at rest, heart sounds one and two were heard with no additional murmurs, heaves, or thrills. Jugular venous pressure was not raised. No peripheral oedema was noted and calves were soft and non-tender. Chest was clear on auscultation. Abdomen was soft and non-tender and normal bowel sounds were heard. GCS [Glasgow coma scale] was 15, pupils were equal and reactive to light [PEARL], cranial nerves 1-12 were intact, and he was moving all four limbs. Observations showed an early warning score of 1 for a tachycardia of 105 beats/ min. Blood pressure was 150/90 mm Hg, respiratory rate 18 breaths/min, saturations were 98% on room air, and he was apyrexial with a temperature of 36.8 ºC.”

Differential diagnoses

Mentioning one or two of the most likely diagnoses is sufficient. A useful phrase you can use is, “I would like to rule out,” especially when you suspect a more serious cause is in the differential diagnosis. “History and examination were in keeping with diverticular disease; however, I would like to rule out colorectal cancer in this patient.”

Remember common things are common, so try not to mention rare conditions first. Sometimes it is acceptable to report investigations you would do first, and then base your differential diagnosis on what the history and investigation findings tell you.

“My impression is acute coronary syndrome. The differential diagnosis includes other cardiovascular causes such as acute pericarditis, myocarditis, aortic stenosis, aortic dissection, and pulmonary embolism. Possible respiratory causes include pneumonia or pneumothorax. Gastrointestinal causes include oesophageal spasm, oesophagitis, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, gastritis, cholecystitis, and acute pancreatitis. I would also consider a musculoskeletal cause for the pain.”

This section can include a summary of the investigations already performed and further investigations that you would like to request. “On the basis of these differentials, I would like to carry out the following investigations: 12 lead electrocardiography and blood tests, including full blood count, urea and electrolytes, clotting screen, troponin levels, lipid profile, and glycated haemoglobin levels. I would also book a chest radiograph and check the patient’s point of care blood glucose level.”

You should consider recommending investigations in a structured way, prioritising them by how long they take to perform and how easy it is to get them done and how long it takes for the results to come back. Put the quickest and easiest first: so bedside tests, electrocardiography, followed by blood tests, plain radiology, then special tests. You should always be able to explain why you would like to request a test. Mention the patient’s baseline test values if they are available, especially if the patient has a chronic condition—for example, give the patient’s creatinine levels if he or she has chronic kidney disease This shows the change over time and indicates the severity of the patient’s current condition.

“To further investigate these differentials, 12 lead electrocardiography was carried out, which showed ST segment depression in the anterior leads. Results of laboratory tests showed an initial troponin level of 85 µg/L, which increased to 1250 µg/L when repeated at six hours. Blood test results showed raised total cholesterol at 7.6 mmol /L and nil else. A chest radiograph showed clear lung fields. Blood glucose level was 6.3 mmol/L; a glycated haemoglobin test result is pending.”

Dependent on the case, you may need to describe the management plan so far or what further management you would recommend.“My management plan for this patient includes ACS [acute coronary syndrome] protocol, echocardiography, cardiology review, and treatment with high dose statins. If you are unsure what the management should be, you should say that you would discuss further with senior colleagues and the patient. At this point, check to see if there is a treatment escalation plan or a “do not attempt to resuscitate” order in place.

“Mr Murphy was given ACS protocol in the emergency department. An echocardiogram has been requested and he has been discussed with cardiology, who are going to come and see him. He has also been started on atorvastatin 80 mg nightly. Mr Murphy and his family are happy with this plan.”

The summary can be a concise recap of what you have presented beforehand or it can sometimes form a standalone presentation. Pick out salient points, such as positive findings—but also draw conclusions from what you highlight. Finish with a brief synopsis of the current situation (“currently pain free”) and next step (“awaiting cardiology review”). Do not trail off at the end, and state the diagnosis if you are confident you know what it is. If you are not sure what the diagnosis is then communicate this uncertainty and do not pretend to be more confident than you are. When possible, you should include the patient’s thoughts about the diagnosis, how they are feeling generally, and if they are happy with the management plan.

“In summary, Mr Murphy is a 56 year old man admitted with central crushing chest pain, radiating down his left arm, of 30 minutes’ duration. His cardiac risk factors include 20 pack year smoking history, positive family history, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension. Examination was normal other than tachycardia. However, 12 lead electrocardiography showed ST segment depression in the anterior leads and troponin rise from 85 to 250 µg/L. Acute coronary syndrome protocol was initiated and a diagnosis of NSTEMI [non-ST elevation myocardial infarction] was made. Mr Murphy is currently pain free and awaiting cardiology review.”

Originally published as: Student BMJ 2017;25:i4406

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed

- ↵ Green EH, Durning SJ, DeCherrie L, Fagan MJ, Sharpe B, Hershman W. Expectations for oral case presentations for clinical clerks: opinions of internal medicine clerkship directors. J Gen Intern Med 2009 ; 24 : 370 - 3 . doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0900-x pmid:19139965 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Olaitan A, Okunade O, Corne J. How to present clinical cases. Student BMJ 2010;18:c1539.

- ↵ Gaillard F. The secret art of relevant negatives, Radiopedia 2016; http://radiopaedia.org/blog/the-secret-art-of-relevant-negatives .

Effective case presentations--an important clinical skill for nurse practitioners

Affiliation.

- 1 Nurse Practitioner Program, Community Health Division, Emory School of Nursing, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

- PMID: 16681708

- DOI: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2006.00125.x

Effective case presentations are an important component of the nurse practitioner's skills, yet very little literature exists to guide the development of this skill, and frequently little priority is given to teaching this skill during the education of the nurse practitioner. This report discusses the importance of effective case presentations, describes the organization of the presentation, and outlines the appropriate information to be included. The main components of a case presentation-introduction, history of the present illness, physical examination, diagnostic studies, differential diagnosis, management, and summary of the case-are discussed in detail. Examples of a formal and an informal case presentation are presented and used to illustrate key points in the text.

- Clinical Competence*

- Communication*

- Diagnosis, Differential

- Medical History Taking

- Nurse Practitioners / education

- Nurse Practitioners / organization & administration*

- Nurse Practitioners / psychology

- Nurse's Role

- Nursing Assessment

- Nursing Records*

- Patient Care Planning

- Physical Examination

- Physician-Nurse Relations*

- Preceptorship

- Treatment Outcome

- Free Study Planner

- Residency Consulting

- Free Resources

- Med School Blog

- 1-888-427-7737

The Ultimate Patient Case Presentation Template for Med Students

- by Neelesh Bagrodia

- Apr 06, 2024

- Reviewed by: Amy Rontal, MD

Knowing how to deliver a patient presentation is one of the most important skills to learn on your journey to becoming a physician. After all, when you’re on a medical team, you’ll need to convey all the critical information about a patient in an organized manner without any gaps in knowledge transfer.

One big caveat: opinions about the correct way to present a patient are highly personal and everyone is slightly different. Additionally, there’s a lot of variation in presentations across specialties, and even for ICU vs floor patients.

My goal with this blog is to give you the most complete version of a patient presentation, so you can tailor your presentations to the preferences of your attending and team. So, think of what follows as a model for presenting any general patient.

Here’s a breakdown of what goes into the typical patient presentation.

7 Ingredients for a Patient Case Presentation Template

1. the one-liner.

The one-liner is a succinct sentence that primes your listeners to the patient.

A typical format is: “[Patient name] is a [age] year-old [gender] with past medical history of [X] presenting with [Y].

2. The Chief Complaint

This is a very brief statement of the patient’s complaint in their own words. A common pitfall is when medical students say that the patient had a chief complaint of some medical condition (like cholecystitis) and the attending asks if the patient really used that word!

An example might be, “Patient has chief complaint of difficulty breathing while walking.”

3. History of Present Illness (HPI)

The goal of the HPI is to illustrate the story of the patient’s complaint.

I remember when I first began medical school, I had a lot of trouble determining what was relevant and ended up giving a lot of extra details. Don’t worry if you have the same issue. With time, you’ll learn which details are important.

The OPQRST Framework

In the beginning of your clinical experience, a helpful framework to use is OPQRST:

Describe when the issue started, and if it occurs during certain environmental or personal exposures.

P rovocative

Report if there are any factors that make the pain better or worse. These can be broad, like noting their shortness of breath worsened when lying flat, or their symptoms resolved during rest.

Relay how the patient describes their pain or associated symptoms. For example, does the patient have a burning versus a pressure sensation? Are they feeling weakness, stiffness, or pain?

R egion/Location

Indicate where the pain is located and if it radiates anywhere.

Talk about how bad the pain is for the patient. Typically, a 0-10 pain scale is useful to provide some objective measure.

Discuss how long the pain lasts and how often it occurs.

A Case Study

While the OPQRST framework is great when starting out, it can be limiting.

Let’s take an example where the patient is not experiencing pain and comes in with altered mental status along with diffuse jaundice of the skin and a history of chronic liver disease. You will find that certain sections of OPQRST do not apply.

In this event, the HPI is still a story, but with a different framework. Try to go in chronological order. Include relevant details like if there have been any changes in medications, diet, or bowel movements.

Pertinent Positive and Negative Symptoms

Regardless of the framework you use, the name of the game is pertinent positive and negative symptoms the patient is experiencing.

I’d like to highlight the word “pertinent.” It’s less likely the patient’s chronic osteoarthritis and its management is related to their new onset shortness of breath, but it’s still important for knowing the patient’s complete medical picture. A better place to mention these details would be in the “Past Medical History” section, and reserve the HPI portion for more pertinent history.

As you become exposed to more illness scripts, experience will teach you which parts of the history are most helpful to state. Also, as you spend more time on the wards, you will pick up on which questions are relevant and important to ask during the patient interview.

By painting a clear picture with pertinent positives and negatives during your presentation, the history will guide what may be higher or lower on the differential diagnosis.

Some other important components to add are the patient’s additional past medical/surgical history, family history, social history, medications, allergies, and immunizations.

The HEADSSS Method

Particularly, the social history is an important time to describe the patient as a complete person and understand how their life story may affect their present condition.

One way of organizing the social history is the HEADSSS method:

– H ome living situation and relationships – E ducation and employment – A ctivities and hobbies – D rug use (alcohol, tobacco, cocaine, etc.) Note frequency of use, and if applicable, be sure to add which types of alcohol consumption (like beer versus hard liquor) and forms of drug use. – S exual history (partners, STI history, pregnancy plans) – S uicidality and depression – S piritual and religious history

Again, there’s a lot of variation in presenting social history, so just follow the lead of your team. For example, it’s not always necessary/relevant to obtain a sexual history, so use your judgment of the situation.

4. Review of Symptoms

Oftentimes, most elements of this section are embedded within the HPI. If there are any additional symptoms not mentioned in the HPI, it’s appropriate to state them here.

5. Objective

Vital signs.

Some attendings love to hear all five vital signs: temperature, blood pressure (mean arterial pressure if applicable), heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation. Others are happy with “afebrile and vital signs stable.” Just find out their preference and stick to that.

Physical Exam

This is one of the most important parts of the patient presentation for any specialty. It paints a picture of how the patient looks and can guide acute management like in the case of a rigid abdomen. As discussed in the HPI section, typically you should report pertinent positives and negatives. When you’re starting out, your attending and team may prefer for you to report all findings as part of your learning.

For example, pulmonary exam findings can be reported as: “Regular chest appearance. No abnormalities on palpation. Lungs resonant to percussion. Clear to auscultation bilaterally without crackles, rhonchi, or wheezing.”

Typically, you want to report the physical exams in a head to toe format: General Appearance, Mental Status, Neurologic, Eyes/Ears/Nose/Mouth/Neck, Cardiovascular, Pulmonary, Breast, Abdominal, Genitourinary, Musculoskeletal, and Skin. Depending on the situation, additional exams can be incorporated as applicable.

Now comes reporting pertinent positive and negative labs. Several labs are often drawn upon admission. It’s easy to fall into the trap of reading off all the labs and losing everyone’s attention. Here are some pieces of advice:

You normally can’t go wrong sticking to abnormal lab values.

One qualification is that for a patient with concern for acute coronary syndrome, reporting a normal troponin is essential. Also, stating the normalization of previously abnormal lab values like liver enzymes is important.

Demonstrate trends in lab values.

A lab value is just a single point in time and does not paint the full picture. For example, a hemoglobin of 10g/dL in a patient at 15g/dL the previous day is a lot more concerning than a patient who has been stable at 10g/dL for a week.

Try to avoid editorializing in this section.

Save your analysis of the labs for the assessment section. Again, this can be a point of personal preference. In my experience, the team typically wants the raw objective data in this section.

This is also a good place to state the ins and outs of your patient (if applicable). In some patients, these metrics are strictly recorded and are typically reported as total fluid in and out over the past day followed by the net fluid balance. For example, “1L in, 2L out, net -1L over the past 24 hours.”

6. Diagnostics/Imaging

Next, you’ll want to review any important diagnostic tests and imaging. For example, describe how the EKG and echo look in a patient presenting with chest pain or the abdominal CT scan in a patient with right lower quadrant abdominal pain.

Try to provide your own interpretation to develop your skills and then include the final impression. Also, report if a diagnostic test is still pending.

7. Assessment/Plan

This is the fun part where you get to use your critical thinking (aka doctor) skills! For the scope of this blog, we’ll review a problem-based plan.

It’s helpful to begin with a summary statement that incorporates the one-liner, presenting issue(s)/diagnosis(es), and patient stability.

Then, go through all the problems relevant to the admission. You can impress your audience by casting a wide differential diagnosis and going through the elements of your patient presentation that support one diagnosis over another.

Following your assessment, try to suggest a management plan. In a patient with congestive heart failure exacerbation, initiating a diuresis regimen and measuring strict ins/outs are good starting points.

You may even suggest a follow-up on their latest ejection fraction with an echo and check if they’re on guideline-directed medical therapy. Again, with more time on the clinical wards you’ll start to pick up on what management plan to suggest.

One pointer is to talk about all relevant problems, not just the presenting issue. For example, a patient with diabetes may need to be put on a sliding scale insulin regimen or another patient may require physical/occupational therapy. Just try to stay organized and be comprehensive.

A Note About Patient Presentation Skills

When you’re doing your first patient presentations, it’s common to feel nervous. There may be a lot of “uhs” and “ums.”

Here’s the good news: you don’t have to be perfect! You just need to make a good faith attempt and keep on going with the presentation.

With time, your confidence will build. Practice your fluency in the mirror when you have a chance. No one was born knowing medicine and everyone has gone through the same stages of learning you are!

Practice your presentation a couple times before you present to the team if you have time. Pull a resident aside if they have the bandwidth to make sure you have all the information you need.

One big piece of advice: NEVER LIE. If you don’t know a specific detail, it’s okay to say, “I’m not sure, but I can look that up.” Someone on your team can usually retrieve the information while you continue on with your presentation.

Example Patient Case Presentation Template

Here’s a blank patient case presentation template that may come in handy. You can adapt it to best fit your needs.

Chief Complaint:

History of Present Illness:

Past Medical History:

Past Surgical History:

Family History:

Social History:

Medications:

Immunizations:

Vital Signs : Temp ___ BP ___ /___ HR ___ RR ___ O2 sat ___

Physical Exam:

General Appearance:

Mental Status:

Neurological:

Eyes, Ears, Nose, Mouth, and Neck:

Cardiovascular:

Genitourinary:

Musculoskeletal:

Most Recent Labs:

Previous Labs:

Diagnostics/Imaging:

Impression/Interpretation:

Assessment/Plan:

One-line summary:

#Problem 1:

Assessment:

#Problem 2:

Final Thoughts on Patient Presentations

I hope this post demystified the patient presentation for you. Be sure to stay organized in your delivery and be flexible with the specifications your team may provide.

Something I’d like to highlight is that you may need to tailor the presentation to the specialty you’re on. For example, on OB/GYN, it’s important to include a pregnancy history. Nonetheless, the aforementioned template should set you up for success from a broad overview perspective.

Stay tuned for my next post on how to give an ICU patient presentation. And if you’d like me to address any other topics in a blog, write to me at [email protected] !

Looking for more (free!) content to help you through clinical rotations? Check out these other posts from Blueprint tutors on the Med School blog:

- How I Balanced My Clinical Rotations with Shelf Exam Studying

- How (and Why) to Use a Qbank to Prepare for USMLE Step 2

- How to Study For Shelf Exams: A Tutor’s Guide

About the Author

Hailing from Phoenix, AZ, Neelesh is an enthusiastic, cheerful, and patient tutor. He is a fourth year medical student at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California and serves as president for the Class of 2024. He is applying to surgery programs for residency. He also graduated as valedictorian of his high school and the USC Viterbi School of Engineering, obtaining a B.S. in Biomedical Engineering in 2020. He discovered his penchant for teaching when he began tutoring his friends for the SAT and ACT in the summer of 2015 out of his living room. Outside of the academic sphere, Neelesh enjoys surfing at San Onofre Beach and hiking in the Santa Monica Mountains. Twitter: @NeeleshBagrodia LinkedIn: http://www.linkedin.com/in/neelesh-bagrodia

Related Posts

The Most Competitive Medical Specialties & How to Prepare

My Journey to Medicine: Charmian’s Story

Meet ResidencyCAS, the New OB/GYN Residency Application System

Search the blog, try blueprint med school study planner.

Create a personalized study schedule in minutes for your upcoming USMLE, COMLEX, or Shelf exam. Try it out for FREE, forever!

Could You Benefit from Tutoring?

Sign up for a free consultation to get matched with an expert tutor who fits your board prep needs

Find Your Path in Medicine

A side by side comparison of specialties created by practicing physicians, for you!

Popular Posts

Need a personalized USMLE/COMLEX study plan?

Myocardial Infarction (MI) Case Study (45 min)

Watch More! Unlock the full videos with a FREE trial

Included In This Lesson

Study tools.

Access More! View the full outline and transcript with a FREE trial

Definition of Myocardial Infarction (MI)

Myocardial infarction, commonly known as a heart attack, is a critical medical event that occurs when the blood supply to the heart muscle is severely reduced or completely blocked. It is a leading cause of death worldwide and a significant public health concern.

Introduction to Myocardial Infarction (MI)

This nursing case study aims to provide a comprehensive understanding of myocardial infarction by delving into its various aspects, including its pathophysiology, risk factors, clinical presentation, diagnostic methods, and management strategies. Through the exploration of a fictional patient’s journey, we will shed light on the intricate nature of this life-threatening condition and highlight the importance of early recognition and intervention.

Background and Significance of Myocardial Infarction

Myocardial infarction is a sudden and often catastrophic event that can have profound consequences on an individual’s health and well-being. Understanding its underlying mechanisms and risk factors is essential for healthcare professionals, as timely intervention can be life-saving. This case study not only serves as a learning tool but also emphasizes the critical role of medical practitioners in identifying and managing myocardial infarctions promptly.

Pathophysiology of Myocardial Infarction

A crucial aspect of comprehending myocardial infarction is exploring its pathophysiology. We will delve into the intricate details of how atherosclerosis, the buildup of plaque in coronary arteries, leads to the formation of blood clots and the subsequent interruption of blood flow to the heart muscle. This disruption in blood supply triggers a cascade of events, ultimately resulting in the death of cardiac cells.

Risk Factors of Myocardial Infarction

Understanding the risk factors associated with myocardial infarction is vital for prevention and early detection. This case study will examine both modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors, including age, gender, family history, smoking, high blood pressure, diabetes, and high cholesterol levels. Recognizing these risk factors is instrumental in developing effective strategies for prevention and risk reduction.

Clinical Presentation Myocardial Infarction

Recognizing the signs and symptoms of myocardial infarction is crucial for timely intervention. We will present a fictional patient’s experience, illustrating the typical clinical presentation, which often includes chest pain or discomfort, shortness of breath, nausea, lightheadedness, and diaphoresis. Through this patient’s journey, we will highlight the importance of accurate symptom assessment and prompt medical attention.

Diagnostic Methods for Myocardial Infarction

Modern medicine offers various diagnostic tools to confirm a myocardial infarction swiftly and accurately. This case study will explore these diagnostic methods, such as electrocardiography (ECG), cardiac biomarkers, and imaging techniques like coronary angiography. By understanding these diagnostic modalities, healthcare professionals can make informed decisions and initiate appropriate treatments promptly.

Management Strategies for Myocardial Infarction

The management of myocardial infarction involves a multidisciplinary approach, including medication, revascularization procedures, and lifestyle modifications. We will discuss the fictional patient’s treatment plan, emphasizing the importance of reestablishing blood flow to the affected heart muscle and preventing further complications.

Nursing Case Study for Myocardial Infarction (MI)

Having established a foundational understanding of myocardial infarction, we will now delve deeper into Mr. Salazar’s case, tracing his journey through diagnosis, treatment, and recovery. This in-depth examination will shed light on the real-world application of the principles discussed in the introduction, providing valuable insights into the clinical management of myocardial infarction and its impact on patient outcomes.

Mr. Salazar, a 57-year-old male, arrives at the Emergency Department (ED) with complaints of chest pain that began approximately one hour after dinner while he was working. He characterizes the discomfort as an intense “crushing pressure” located centrally in his chest, extending down his left arm and towards his back. He rates the pain’s severity as 4/10. Upon examination, Mr. Salazar exhibits diaphoresis and pallor, accompanied by shortness of breath (SOB).

What further nursing assessments need to be performed for Mr. Salazar?

- Heart Rate (HR): The number of heartbeats per minute.

- Blood Pressure (BP): The force of blood against the walls of the arteries, typically measured as systolic (during heartbeats) and diastolic (between heartbeats) pressure.

- Respiratory Rate (RR): The number of breaths a patient takes per minute.

- Body Temperature (Temp): The measurement of a patient’s internal body heat.

- Oxygen Saturation (SpO2): The percentage of oxygen in the blood.

- S1: The first heart sound, often described as “lub,” is caused by the closure of the mitral and tricuspid valves.

- S2: The second heart sound, known as “dub,” results from the closure of the aortic and pulmonic valves.

- These sounds provide important diagnostic information about the condition of the heart.

- Clear: Normal, healthy lung sounds with no added sounds.

- Crackles (Rales): Discontinuous, often high-pitched sounds are heard with conditions like pneumonia or heart failure.

- Wheezes: Whistling, musical sounds often associated with conditions like asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

- Pulses refer to the rhythmic expansion and contraction of arteries with each heartbeat. Common pulse points for assessment include the radial artery (wrist), carotid artery (neck), and femoral artery (groin). Evaluating pulses helps assess the strength, regularity, and rate of blood flow.

- Edema is the abnormal accumulation of fluid in body tissues, leading to swelling. It can occur in various body parts and may indicate underlying conditions such as heart failure, kidney disease, or localized injury. Edema assessment involves evaluating the degree of swelling and its location.

- Skin condition (temperature, color, etc.)

What interventions do you anticipate being ordered by the provider?

- Oxygen therapy involves administering oxygen to a patient to increase the level of oxygen in their blood. It is used to treat conditions such as respiratory distress, and hypoxia (low oxygen levels), and to support patients with breathing difficulties.

- Nitroglycerin is a medication used to treat angina (chest pain) and to relieve symptoms of heart-related conditions. It works by relaxing and widening blood vessels, which improves blood flow to the heart, reducing chest pain.

- Aspirin is a common over-the-counter medication and antiplatelet drug. In the context of myocardial infarction (heart attack), it is often administered to reduce blood clot formation, potentially preventing further blockage in coronary arteries.

- A 12-lead EKG is a diagnostic test that records the electrical activity of the heart from 12 different angles. It provides information about the heart’s rhythm, rate, and any abnormalities, helping diagnose conditions like arrhythmias, heart attacks, and ischemia.

- Cardiac enzymes are proteins released into the bloodstream when heart muscle cells are damaged or die, typically during a heart attack. Measuring these enzymes, such as troponin and creatine kinase-MB (CK-MB), helps confirm a heart attack diagnosis and assess its severity.

- A chest X-ray is a diagnostic imaging procedure that creates images of the chest and its internal structures, including the heart and lungs. It is used to identify issues like lung infections, heart enlargement, fluid accumulation, or fractures in the chest area.

- Possibly an Echocardiogram

Upon conducting a comprehensive assessment, it was observed that the patient exhibited no signs of jugular vein distention (JVD) or edema. Auscultation revealed normal heart sounds with both S1 and S2 present, while the lungs remained clear, albeit with scattered wheezes. The patient’s vital signs were recorded as follows:

- BP 140/90 mmHg SpO 2 90% on Room Air

- HR 92 bpm and regular Ht 173 cm

- RR 32 bpm Wt 104 kg

- Temp 36.9°C

The 12-lead EKG repor t indicated the presence of “Normal sinus rhythm (NSR) with frequent premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) and three- to four-beat runs of ventricular tachycardia (VT).” Additionally, there was ST-segment elevation in leads I, aVL, and V2 through V6 (3-4mm), accompanied by ST-segment depression in leads III and aVF.

Cardiac enzyme levels were collected but were awaiting results at the time of assessment. A chest x-ray was also ordered to provide further diagnostic insights.

In response to the patient’s condition, the healthcare provider prescribed the following interventions:

- Aspirin: 324 mg administered orally once.

- Nitroglycerin: 0.4 mg administered sublingually (SL), with the option of repeating the dose every five minutes for a maximum of three doses.

- Morphine: 4 mg to be administered intravenously (IVP) as needed for unrelieved chest pain.

- Oxygen: To maintain oxygen saturation (SpO2) levels above 92%.

These interventions were implemented to address the patient’s myocardial infarction (heart attack) and alleviate associated symptoms, with a focus on relieving chest pain, improving oxygenation, and closely monitoring vital signs pending further diagnostic results.

What intervention should you, as the nurse, perform right away? Why?

- Apply oxygen – this can be done quickly and easily and can help to prevent further complications from low oxygenation.

- Oxygen helps to improve oxygenation as well as to decrease myocardial oxygen demands.

- Often it takes a few minutes or more for medications to be available from the pharmacy, so it makes sense to take care of this intervention first.

- ABC’s – breathing/O 2 .

What medication should be the first one administered to this patient? Why? How often?

- Nitroglycerin 0.4mg SL – it is a vasodilator and works on the coronary arteries. The goal is to increase blood flow to the myocardium. If this is effective, the patient merely has angina. However, if it is not effective, the patient may have a myocardial infarction.

- Aspirin should also be given, but it is to decrease platelet aggregation and reduce mortality. While it can somewhat help prevent the worsening of the blockage, it does little for the current pain experienced by the patient.

- Morphine should only be given if the nitroglycerin and aspirin do not relieve the patient’s chest pain.

What is the significance of the ST-segment changes on Mr. Salazar's 12-lead EKG?

- ST-segment changes on a 12-lead EKG indicate ischemia (lack of oxygen/blood flow) or infarction (death of the muscle tissue) of the myocardium (heart muscle).

- This indicates an emergent situation. The patient’s coronary arteries are blocked and need to be reopened by pharmacological (thrombolytic) or surgical (PCI) intervention.

- Time is tissue – the longer the coronary arteries stay blocked, the more of the patient’s myocardium that will die. Dead heart tissue doesn’t beat.

Mr. Salazar’s chest pain was unrelieved after three (3) doses of sublingual nitroglycerin (NTG). Morphine 5 mg intravenous push (IVP) was administered, as well as 324 mg chewable baby aspirin. His pain was still unrelieved at this point

Mr. Salazar’s cardiac enzyme results were as follows:

Troponin I 3.5 ng/mL

Based on the results of Mr. Salazar's labs and his response to medications, what is the next intervention you anticipate? Why?

- Mr. Salazar needs intervention. He will either receive thrombolytics or a heart catheterization (PCI).

- Based on the EKG changes, elevated Troponin level, and the fact that his symptoms are not subsiding, it’s possible the patient has a significant blockage in one or more of his coronary arteries.

- It seems as though it may be an Anterior-Lateral MI because ST elevation is occurring in I, aVL, and V 2 -V 6 .

Mr. Salazar was taken immediately to the cath lab for a Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI). The cardiologist found a 90% blockage in his left anterior descending (LAD) artery. A stent was inserted to keep the vessel open.

What is the purpose of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI), also known as a heart catheterization?

- A PCI serves to open up any coronary arteries that are blocked. First, they use contrast dye to determine where the blockage is, then they use a special balloon catheter to open the blocked vessels.

- If that doesn’t work, they will place a cardiac stent in the vessel to keep it open.[ /faq]

[faq lesson="true" blooms="Application" question="What is the expected outcome of a PCI? What do you expect to see in your patient after they receive a heart catheterization?"]

- Blood flow will be restored to the myocardium with minimal residual damage.

- The patient should have baseline vital signs, relief of chest pain, normal oxygenation status, and absence of heart failure symptoms (above baseline).

- The patient should be able to ambulate without significant chest pain or SOB.

- The patient should be free from bleeding or hematoma at the site of catheterization (often femoral, but can also be radial or (rarely) carotid.

Mr. Salazar tolerated the PCI well and was admitted to the cardiac telemetry unit for observation overnight. Four (4) hours after the procedure, Mr. Salazar reports no chest pain. His vital signs are now as follows:

- BP 128/82 mmHg SpO 2 96% on 2L NC

- HR 76 bpm and regular RR 18 bpm

- Temp 37.1°C

Mr. Salazar will be discharged home 24 hours after his arrival to the ED and will follow up with his cardiologist next week.

What patient education topics would need to be covered with Mr. Salazar?

- He should be taught any dietary and lifestyle changes that should be made.

- Diet – low sodium, low cholesterol, avoid sugar/soda, avoid fried/processed foods.

- Exercise – 30-45 minutes of moderate activity 5-7 days a week, u nless instructed otherwise by a cardiologist. This will be determined by the patient’s activity tolerance – how much can they do and still be able to breathe and be pain-free?

- Stop smoking and avoid caffeine and alcohol.

- Medication Instructions

- Nitroglycerin – take one SL tab at the onset of chest pain. If the pain does not subside after 5 minutes, call 911 and take a second dose. You can take a 3rd dose 5 minutes after the second if the pain does not subside. Do NOT take if you have taken Viagra in the last 24 hours.

- Aspirin – take 81 mg of baby aspirin daily

- Anticoagulant – the patient may be prescribed an anticoagulant if they had a stent placed. They should be taught about bleeding risks.

- When to call the provider – CP unrelieved by nitroglycerin after 5 minutes. Syncope. Evidence of bleeding in stool or urine (if on anticoagulant). Palpitations, shortness of breath, or difficulty tolerating activities of daily living.

Linchpins for Myocardial Infarction Nursing Case Study

In summary, Mr. Salazar’s case highlights the urgency of recognizing and responding to myocardial infarction promptly. The application of vital signs, EKG, cardiac enzymes, and medications like aspirin, nitroglycerin, and morphine played a pivotal role in his care. Diagnostic tools like echocardiography and chest X-rays contributed to a comprehensive evaluation.

Nurses must remain vigilant and compassionate in such emergencies. This case study emphasizes the importance of adhering to best practices in the assessment, diagnosis, and management of myocardial infarction, with the ultimate goal of achieving favorable patient outcomes.

View the FULL Outline

When you start a FREE trial you gain access to the full outline as well as:

- SIMCLEX (NCLEX Simulator)

- 6,500+ Practice NCLEX Questions

- 2,000+ HD Videos

- 300+ Nursing Cheatsheets

“Would suggest to all nursing students . . . Guaranteed to ease the stress!”

Nursing Case Studies

This nursing case study course is designed to help nursing students build critical thinking. Each case study was written by experienced nurses with first hand knowledge of the “real-world” disease process. To help you increase your nursing clinical judgement (critical thinking), each unfolding nursing case study includes answers laid out by Blooms Taxonomy to help you see that you are progressing to clinical analysis.We encourage you to read the case study and really through the “critical thinking checks” as this is where the real learning occurs. If you get tripped up by a specific question, no worries, just dig into an associated lesson on the topic and reinforce your understanding. In the end, that is what nursing case studies are all about – growing in your clinical judgement.

Nursing Case Studies Introduction

Cardiac nursing case studies.

- 6 Questions

- 7 Questions

- 5 Questions

- 4 Questions

GI/GU Nursing Case Studies

- 2 Questions

- 8 Questions

Obstetrics Nursing Case Studies

Respiratory nursing case studies.

- 10 Questions

Pediatrics Nursing Case Studies

- 3 Questions

- 12 Questions

Neuro Nursing Case Studies

Mental health nursing case studies.

- 9 Questions

Metabolic/Endocrine Nursing Case Studies

Other nursing case studies.

How to make an oral case presentation to healthcare colleagues

The content and delivery of a patient case for education and evidence-based care discussions in clinical practice.

BSIP SA / Alamy Stock Photo

A case presentation is a detailed narrative describing a specific problem experienced by one or more patients. Pharmacists usually focus on the medicines aspect , for example, where there is potential harm to a patient or proven benefit to the patient from medication, or where a medication error has occurred. Case presentations can be used as a pedagogical tool, as a method of appraising the presenter’s knowledge and as an opportunity for presenters to reflect on their clinical practice [1] .

The aim of an oral presentation is to disseminate information about a patient for the purpose of education, to update other members of the healthcare team on a patient’s progress, and to ensure the best, evidence-based care is being considered for their management.

Within a hospital, pharmacists are likely to present patients on a teaching or daily ward round or to a senior pharmacist or colleague for the purpose of asking advice on, for example, treatment options or complex drug-drug interactions, or for referral.

Content of a case presentation

As a general structure, an oral case presentation may be divided into three phases [2] :

- Reporting important patient information and clinical data;

- Analysing and synthesising identified issues (this is likely to include producing a list of these issues, generally termed a problem list);

- Managing the case by developing a therapeutic plan.

Specifically, the following information should be included [3] :

Patient and complaint details

Patient details: name, sex, age, ethnicity.

Presenting complaint: the reason the patient presented to the hospital (symptom/event).

History of presenting complaint: highlighting relevant events in chronological order, often presented as how many days ago they occurred. This should include prior admission to hospital for the same complaint.

Review of organ systems: listing positive or negative findings found from the doctor’s assessment that are relevant to the presenting complaint.

Past medical and surgical history

Social history: including occupation, exposures, smoking and alcohol history, and any recreational drug use.

Medication history, including any drug allergies: this should include any prescribed medicines, medicines purchased over-the-counter, any topical preparations used (including eye drops, nose drops, inhalers and nasal sprays) and any herbal or traditional remedies taken.

Sexual history: if this is relevant to the presenting complaint.

Details from a physical examination: this includes any relevant findings to the presenting complaint and should include relevant observations.

Laboratory investigation and imaging results: abnormal findings are presented.

Assessment: including differential diagnosis.

Plan: including any pharmaceutical care issues raised and how these should be resolved, ongoing management and discharge planning.

Any discrepancies between the current management of the patient’s conditions and evidence-based recommendations should be highlighted and reasons given for not adhering to evidence-based medicine ( see ‘Locating the evidence’ ).

Locating the evidence

The evidence base for the therapeutic options available should always be considered. There may be local guidance available within the hospital trust directing the management of the patient’s presenting condition. Pharmacists often contribute to the development of such guidelines, especially if medication is involved. If no local guidelines are available, the next step is to refer to national guidance. This is developed by a steering group of experts, for example, the British HIV Association or the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . If the presenting condition is unusual or rare, for example, acute porphyria, and there are no local or national guidelines available, a literature search may help locate articles or case studies similar to the case.

Giving a case presentation

Currently, there are no available acknowledged guidelines or systematic descriptions of the structure, language and function of the oral case presentation [4] and therefore there is no standard on how the skills required to prepare or present a case are taught. Most individuals are introduced to this concept at undergraduate level and then build on their skills through practice-based learning.

A case presentation is a narrative of a patient’s care, so it is vital the presenter has familiarity with the patient, the case and its progression. The preparation for the presentation will depend on what information is to be included.

Generally, oral case presentations are brief and should be limited to 5–10 minutes. This may be extended if the case is being presented as part of an assessment compared with routine everyday working ( see ‘Case-based discussion’ ). The audience should be interested in what is being said so the presenter should maintain this engagement through eye contact, clear speech and enthusiasm for the case.

It is important to stick to the facts by presenting the case as a factual timeline and not describing how things should have happened instead. Importantly, the case should always be concluded and should include an outcome of the patient’s care [5] .

An example of an oral case presentation, given by a pharmacist to a doctor, is available here .

A successful oral case presentation allows the audience to garner the right amount of patient information in the most efficient way, enabling a clinically appropriate plan to be developed. The challenge lies with the fact that the content and delivery of this will vary depending on the service, and clinical and audience setting [3] . A practitioner with less experience may find understanding the balance between sufficient information and efficiency of communication difficult, but regular use of the oral case presentation tool will improve this skill.

Tailoring case presentations to your audience

Most case presentations are not tailored to a specific audience because the same type of information will usually need to be conveyed in each case.

However, case presentations can be adapted to meet the identified learning needs of the target audience, if required for training purposes. This method involves varying the content of the presentation or choosing specific cases to present that will help achieve a set of objectives [6] . For example, if a requirement to learn about the management of acute myocardial infarction has been identified by the target audience, then the presenter may identify a case from the cardiology ward to present to the group, as opposed to presenting a patient reviewed by that person during their normal working practice.

Alternatively, a presenter could focus on a particular condition within a case, which will dictate what information is included. For example, if a case on asthma is being presented, the focus may be on recent use of bronchodilator therapy, respiratory function tests (including peak expiratory flow rate), symptoms related to exacerbation of airways disease, anxiety levels, ability to talk in full sentences, triggers to worsening of symptoms, and recent exposure to allergens. These may not be considered relevant if presenting the case on an unrelated condition that the same patient has, for example, if this patient was admitted with a hip fracture and their asthma was well controlled.

Case-based discussion

The oral case presentation may also act as the basis of workplace-based assessment in the form of a case-based discussion. In the UK, this forms part of many healthcare professional bodies’ assessment of clinical practice, for example, medical professional colleges.

For pharmacists, a case-based discussion forms part of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) Foundation and Advanced Practice assessments . Mastery of the oral case presentation skill could provide useful preparation for this assessment process.

A case-based discussion would include a pharmaceutical needs assessment, which involves identifying and prioritising pharmaceutical problems for a particular patient. Evidence-based guidelines relevant to the specific medical condition should be used to make treatment recommendations, and a plan to monitor the patient once therapy has started should be developed. Professionalism is an important aspect of case-based discussion — issues must be prioritised appropriately and ethical and legal frameworks must be referred to [7] . A case-based discussion would include broadly similar content to the oral case presentation, but would involve further questioning of the presenter by the assessor to determine the extent of the presenter’s knowledge of the specific case, condition and therapeutic strategies. The criteria used for assessment would depend on the level of practice of the presenter but, for pharmacists, this may include assessment against the RPS Foundation or Pharmacy Frameworks .

Acknowledgement

With thanks to Aamer Safdar for providing the script for the audio case presentation.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal . You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

[1] Onishi H. The role of case presentation for teaching and learning activities. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2008;24:356–360. doi: 10.1016/s1607-551x(08)70132–3

[2] Edwards JC, Brannan JR, Burgess L et al . Case presentation format and clinical reasoning: a strategy for teaching medical students. Medical Teacher 1987;9:285–292. doi: 10.3109/01421598709034790

[3] Goldberg C. A practical guide to clinical medicine: overview and general information about oral presentation. 2009. University of California, San Diego. Available from: https://meded.ecsd.edu/clinicalmed.oral.htm (accessed 5 December 2015)

[4] Chan MY. The oral case presentation: toward a performance-based rhetorical model for teaching and learning. Medical Education Online 2015;20. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.28565

[5] McGee S. Medicine student programs: oral presentation guidelines. Learning & Scholarly Technologies, University of Washington. Available from: https://catalyst.uw.edu/workspace/medsp/30311/202905 (accessed 7 December 2015)

[6] Hays R. Teaching and Learning in Clinical Settings. 2006;425. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing Ltd.

[7] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Tips for assessors for completing case-based discussions. 2015. Available from: http://www.rpharms.com/help/case_based_discussion.htm (accessed 30 December 2015)

You might also be interested in…

How to demonstrate empathy and compassion in a pharmacy setting

Be more proactive to convince medics, pharmacists urged

How pharmacists can encourage patient adherence to medicines

Got any suggestions?