Essay on Mahatma Gandhi – Contributions and Legacy of Mahatma Gandhi

500+ words essay on mahatma gandhi.

Essay on Mahatma Gandhi – Mahatma Gandhi was a great patriotic Indian, if not the greatest. He was a man of an unbelievably great personality. He certainly does not need anyone like me praising him. Furthermore, his efforts for Indian independence are unparalleled. Most noteworthy, there would have been a significant delay in independence without him. Consequently, the British because of his pressure left India in 1947. In this essay on Mahatma Gandhi, we will see his contribution and legacy.

Contributions of Mahatma Gandhi

First of all, Mahatma Gandhi was a notable public figure. His role in social and political reform was instrumental. Above all, he rid the society of these social evils. Hence, many oppressed people felt great relief because of his efforts. Gandhi became a famous international figure because of these efforts. Furthermore, he became the topic of discussion in many international media outlets.

Mahatma Gandhi made significant contributions to environmental sustainability. Most noteworthy, he said that each person should consume according to his needs. The main question that he raised was “How much should a person consume?”. Gandhi certainly put forward this question.

Furthermore, this model of sustainability by Gandhi holds huge relevance in current India. This is because currently, India has a very high population . There has been the promotion of renewable energy and small-scale irrigation systems. This was due to Gandhiji’s campaigns against excessive industrial development.

Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy of non-violence is probably his most important contribution. This philosophy of non-violence is known as Ahimsa. Most noteworthy, Gandhiji’s aim was to seek independence without violence. He decided to quit the Non-cooperation movement after the Chauri-Chaura incident . This was due to the violence at the Chauri Chaura incident. Consequently, many became upset at this decision. However, Gandhi was relentless in his philosophy of Ahimsa.

Secularism is yet another contribution of Gandhi. His belief was that no religion should have a monopoly on the truth. Mahatma Gandhi certainly encouraged friendship between different religions.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Legacy of Mahatma Gandhi

Mahatma Gandhi has influenced many international leaders around the world. His struggle certainly became an inspiration for leaders. Such leaders are Martin Luther King Jr., James Beve, and James Lawson. Furthermore, Gandhi influenced Nelson Mandela for his freedom struggle. Also, Lanza del Vasto came to India to live with Gandhi.

The awards given to Mahatma Gandhi are too many to discuss. Probably only a few nations remain which have not awarded Mahatma Gandhi.

In conclusion, Mahatma Gandhi was one of the greatest political icons ever. Most noteworthy, Indians revere by describing him as the “father of the nation”. His name will certainly remain immortal for all generations.

Essay Topics on Famous Leaders

- Mahatma Gandhi

- APJ Abdul Kalam

- Jawaharlal Nehru

- Swami Vivekananda

- Mother Teresa

- Rabindranath Tagore

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel

- Subhash Chandra Bose

- Abraham Lincoln

- Martin Luther King

FAQs on Mahatma Gandhi

Q.1 Why Mahatma Gandhi decided to stop Non-cooperation movement?

A.1 Mahatma Gandhi decided to stop the Non-cooperation movement. This was due to the infamous Chauri-Chaura incident. There was significant violence at this incident. Furthermore, Gandhiji was strictly against any kind of violence.

Q.2 Name any two leaders influenced by Mahatma Gandhi?

A.2 Two leaders influenced by Mahatma Gandhi are Martin Luther King Jr and Nelson Mandela.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

- Home /

- Reports /

Two Indias: Gandhi and Modern India by Prof Johan Galtung

Gandhian Perspectives on Conflict and Peace – Hindu University, FL USA

Gandhi was born 2 October 1869, was killed 30 January 1948 by a Pune brahmin, Godse. I was a 17 years old boy in Norway who cried when hearing the news. Something unheard of had happened.

But I did not know why I cried, and wanted to know more. Who was Gandhi? So I became a Gandhi scholar as assistant and co-author to the late Arne Næss in his seminal work of extracting from Gandhi’s works and words his Gandhi’s Political Ethics as a norm-system. Note [i]

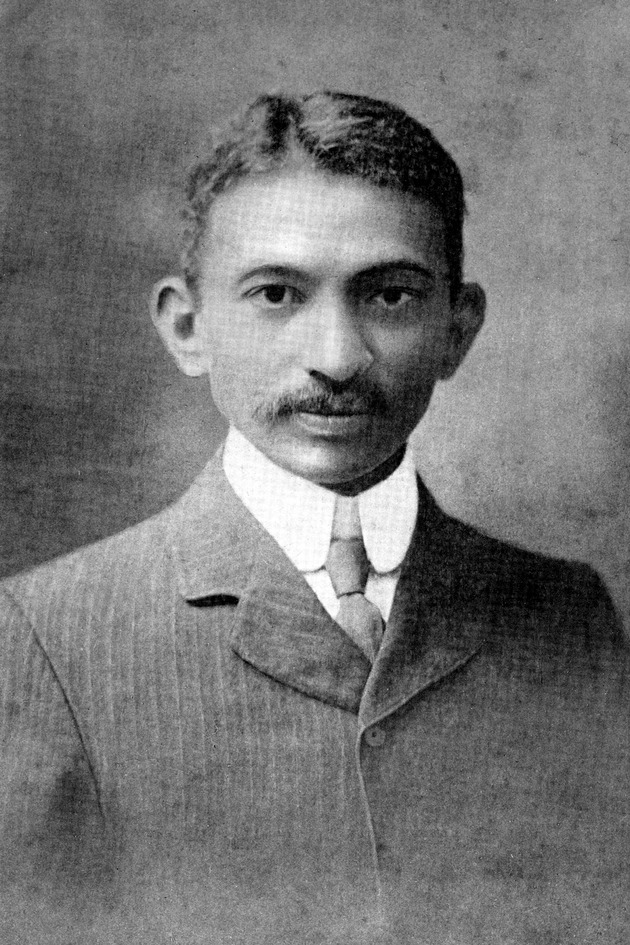

Mahatma Gandhi

The image of the India I love is the image of Gandhi. I know perfectly well that there are other Indias. And Ashis Nandy sensitized me to why the court proceedings against Godse were kept secret: because his arguments were that Gandhi stood in the way of the modern India the government wanted, with industrialization, booming cities, growth, trade, a strong army; the whole package.

Very different from Gandhi’s self-sufficient sarvodaya villages, linked by “oceanic circles”, focused on spiritual rather than material growth. Very similar to the Buddhist image of the small sangha community. And in line with Gandhi’s idea that he may actually have been a Buddhist; without any vertical ranking of occupations.

Gandhi’s link to Buddhism and rejection of caste may have been on top of Godse’s motivation, adding to modernity. Nehru’s India was also a modern India, with a socialist LSE-Harold Laski, Soviet touch. Nehru and Gandhi shared anti-colonialism but differed in their images of independent India. Modernity, and even more so, Soviet top-down socialism, were very remote from Gandhi’s bottom-up world.

Gandhi was instrumentalized by Congress to get rid of Britons preaching against caste. India became independent, after a disastrous partition mainly caused by Lord Mountbatten; free to enter modernity, and to keep caste. The Congress Party got the cake and ate it too. So, I see two Indias, Gandhi and modernity, knowing there are more.

Two Indian civilizations, with much clash and little dialogue. And some dwarfs rejecting India’s greatest son. Some time ago there were books on and by Gandhi at New Delhi airport; today we find books on business administration. A non-dialogue of two civilizations within one country. This essay opens for that missing dialogue, for the millions touched by the genius of the Gandhi that modern India expelled, like traditional India did to another genius coming out of roughly the same land, the Buddha. The image of India abroad is still shaped by both.

Gandhi, a vaisya prime minister’s son, a lawyer trained in England, struggling with the drives of sex and food, finding his brahmacharya . Indian themes with as much or more claim on India as the present growth machine serving the upper castes and classes at the expense of growing inequality and the suffering of the 1/3 of the world’s starving, living in one country, India. An India linked to a falling global empire, USA; and a regional declining empire, Israel.

An India with direct violence by acts of commission; structural violence producing more suffering than direct violence upheld by acts of omission; and cultural violence legitimizing either or both. And Indo-European class structure, with brahmin specialists on cultural violence, kshatriyas on direct violence, and vaisyas on structural violence; unleashing all three on common people and women.

That tradition of direct violence + steep pyramids of structural violence + legitimacy from a divine mandate also predict well the four most belligerent countries over the last 1,000 years: USA, Israel, UK and Turkey. Watch for the dangers of guilt by cooperation and association with those four.

Gandhi will survive this perverted Indian modernity. Gandhi’s four S’s, satyagraha-swaraj-swadeshi-sarvodaya , are better approaches to the three UN goals sustainable peace, development and environment.

Satyagraha : holding on to Satya, a Truth-Love-God trinity, his unity-of-human beings. As factual truth, as togetherness-compassion-love, and as embodying the divine. The word ahimsa , nonviolence, reflects this badly. More than 100 years ago Gandhi coined satyagraha drawing on vasudaiva kuttumbakam-the world is my family . Very Indian.

But not practiced by 700,000 Hindu soldiers in Kashmir ruling over the Muslims, and in even more misery and inequality by driving tribals and casteless off the land and killing Naxalites with drones.

Swaraj : self-rule, swa , the Self of identity, with Raj, rule. Gandhi praised openness refusing to be blown off his feet. Be rooted, deepen the rootedness, develop your self, your spirit, be in command of your identity; concepts beyond an independence ceremony with flags lowered and raised. Gandhi even did not attend; he fought the Lord Mountbatten-twisted partition with its devastating consequences.

Swadeshi : meeting needs for food, shelter, clothing, self-made . No to English textiles-Yes to khadi . Gandhi even collected money for Bombay textile merchants; the textiles, not they, were the problem.

Sarvodaya : the uplift of the poor, inspired by Gandhi’s dictum, there is enough for everybody’s need, but not for everybody’s greed.

Gandhi was for need, modernity for greed; Gandhi for local self-reliance, modernity for unlimited trade; Gandhi for building on own identity, modernity for americanization as neo-nirvana; Gandhi for nonviolent conflict resolution, modernity for police, military, war.

India’s modernity suffers a crash landing, with revolts from Orissa to Kerala. Even worse: massive suicide by desperate, indebted farmers being driven off the land, even selling their daughters.

Both Delhi and the Naxalites would be better off with Gandhi’s Four S’s than with New Delhi state terrorism-torturism and Naxalite terrorism. A blessing to have Gandhi on the reserve shelf; but it is needed in reality, not on any shelf, and backed by political power.

APPENDIX: The Gandhi Conflict Norms

- GOALS AND CONFLICT

N 11 Act in conflicts!

N 111 Act now!

N 112 Act here!

N 113 Act for your own group!

N 114 Act out of identity!

N 115 Act out of conviction!

N 12 Define the conflict well!

N 121 State your own goal clearly!

N 122 Try to understand your opponent’s goal!

N 123 Emphasize common and compatible goals!

N 124 State the conflict relevant facts objectively!

N 13 Have a positive approach to conflict!

N 131 Give the conflict a positive emphasis!

N 132 See conflict as opportunity to meet the opponent!

N 133 See conflict as opportunity to transform society!

N 134 See conflict as opportunity to transform yourself!

- CONFLICT STRUGGLE

N 21 Act non-violently in conflicts!

N 211 Do not hurt or harm with deeds!

N 212 Do not hurt or harm with words!

N 213 Do not hurt or harm with thoughts!

N 214 Do not harm the opponent’s property!

N 215 Prefer violence to cowardice!

N 216 Do good even to the evil‑doer!

N 22 Act in a goal‑consistent manner!

N 221 Always include a constructive element!

N 222 Use goal‑revealing forms of struggle!

N 223 Act openly, not secretly!

N 224 Aim the struggle at the correct point!

N 23 Do not cooperate with evil!

N 231 Non‑cooperation with evil structure!

N 232 Non‑cooperation with evil status!

N 233 Non‑cooperation with evil action!

N 234 Non‑cooperation with those who cooperate with evil!

N 24 Be willing to sacrifice!

N 241 Do not escape from punishment!

N 242 Be willing to die if necessary!

N 25 Do not polarize!

N 251 Distinguish between antagonism and antagonist!

N 252 Distinguish between person and status!

N 253 Maintain contact!

N 254 Empathy with your opponent’s position!

N 255 Be flexible in defining parties and positions!

N 26 Do not escalate!

N 261 Remain as loyal as possible!

N 262 Do not provoke or let yourself be provoked!

N 263 Do no humiliate or let yourself be humiliated!

N 264 Do no expand the goals for the conflict!

N 265 Use the mildest possible forms of conflict behavior!

- CONFLICT RESOLUTION

N 31 Solve conflict!

N 311 Do not continue conflict struggle forever!

N 312 Always seek negotiation with the opponent!

N 313 Seek positive social transformations!

N 314 Seek human transformation!

‑ of yourself

‑ of the opponent

N 32 Insist on the essentials, not on non‑essentials!

N 321 Do not trade with essentials!

N 322 Be willing to compromise on non‑essentials!

N 33 See yourself as fallible!

N 331 Remember that you may be wrong!

N 332 Admit your mistakes openly!

N 333 Consistency over time not very important!

N 34 Be generous in your view of the opponent!

N 341 Do not exploit the opponent’s weaknesses!

N 342 Do not judge the opponent harder than yourself!

N 343 Trust your opponent!

N 35 Conversion, not coercion!

N 351 Always seek solutions that are accepted!

‑ by yourself

‑ by the opponent!

N 352 Never coerce your opponent!

N 353 Convert your opponent into a believer in the cause!

[i] . For my own version of that system please see the Appendix, taken from my The Way is the Goal , Ahmdavad: Navajivan, 1995 (also reprinted on the back of the cover-pages of A Theory of Conflict, TRANSCEND University Press, 2010 ).

credits: TMS: Two Indias: Gandhi and Modern India

Related Posts

Aapi plans india’s 75th independence day anniversary celebrations on capitol hill, aapi collaborates in boosting the tb notification (btn) campaign to help make india free of tuberculosis, art-literature for social change – annabhau’s struggles: contributions —— prof ram puniyani, book —— corona virus: india’s experience, prof. v.s. mallar memorial legal aid competition 2022 —— by ceera-nlsiu and the department of justice, ministry of law and justice, goi, aapi-tn raises $75,000 to fight human trafficking in india —— ajay ghosh, resisting the gatekeepers of hell: gandhi, ‘vaccine passports’ and the great reset —— dr robert j. burrowes, international conference on relevance of sri aurobindo and the grand visions of the ancient indian wisdom, sri aurobindo conference – hindu university usa, edward carpenter and the healing of nations —— rene wadlow.

Leave a comment:

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Latest posts

बाबा साहेब का धम्म का मार्ग स्वतंत्र भारत की सबसे बड़ी अहिंसक क्रांति है —— vidya bhushan rawat, दलितों की भागीदारी और सम्मान के बिना द्रवीडियन मोडेल सफल नहीं हो सकता —— vidya bhushan rawat, the queen is dead, long live the king −− by vidya bhushan rawat, गरीबों का आरक्षण —— vidya bhushan rawat, tigray: after the calm, a possible storm —— rené wadlow, digitizing your identity is the fast-track to slavery: how can you defend your freedom —— robert j. burrowes, सामंती जातिवाद से आजादी —— vidya bhushan rawat.

Who was Mahatma Gandhi and what impact did he have on India?

Mahatma Ghandi is revered by many people all over the world as a symbol of unity and peace. Image: REUTERS/Lunae Parracho (BRAZIL - Tags: SOCIETY TPX IMAGES OF THE DAY) - GM1E92B0PS401

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Sean Fleming

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} India is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

He’s one of the most instantly recognizable figures of the 20th century – Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, better known to many as Mahatma Gandhi or Great Soul.

The 2nd of October marks the anniversary of Gandhi’s birth and the start of a life of struggle in the fight for Indian independence from British colonial rule.

It’s an occasion being marked all over the world, particularly in India.

But who was Mahatma Gandhi and how did he end up championing Indian independence? Here’s a brief timeline of his life.

Mahatma Gandhi - Legal leanings

He was born in 1869 in the princely state of Porbandar, in modern-day Gujarat , where his father served as a government official. At the age of just 18, Gandhi sailed for London to study law, where he eventually passed the bar exam and qualified as a barrister.

But any hopes he may have had of a glorious legal career soon began to crumble. After losing his first case back home in India, he left India again, this time for South Africa. It was there he became so nervous advocating on behalf of a client in court that he couldn’t speak properly. He ended up reimbursing his client and fleeing the courthouse.

Under the theme, Innovating for India: Strengthening South Asia, Impacting the World , the World Economic Forum's India Economic Summit 2019 will convene key leaders from government, the private sector, academia and civil society on 3-4 October to accelerate the adoption of Fourth Industrial Revolution technologies and boost the region’s dynamism.

Hosted in collaboration with the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), the aim of the Summit is to enhance global growth by promoting collaboration among South Asian countries and the ASEAN economic bloc.

The meeting will address strategic issues of regional significance under four thematic pillars:

• The New Geopolitical Reality – Geopolitical shifts and the complexity of our global system

• The New Social System – Inequality, inclusive growth, health and nutrition

• The New Ecological System – Environment, pollution and climate change

• The New Technological System – The Fourth Industrial Revolution, science, innovation and entrepreneurship

Discover a few ways the Forum is creating impact across India.

Read our guide to how to follow #ies19 across our digital channels. We encourage followers to post, share, and retweet by tagging our accounts and by using our official hashtag.

Become a Member or Partner to participate in the Forum's year-round annual and regional events. Contact us now .

But it was another incident in South Africa that set Mahatma Gandhi on a new path. While travelling first class on a train, he was ejected from his carriage after a white passenger complained . The experience would help to solidify some of the ideas he had already started to form around equality for all people.

A tax on your roots

Indian immigrants in South Africa were subject to punitive laws and restrictions on freedoms. There was even a tax levied on them simply because they were Indian immigrants. Mahatma Gandhi set about tackling segregation and founded the Indian Congress in the Natal region of South Africa. This was also the point at which he began dressing in the traditional white Indian dhoti, which became his trademark attire.

His first target was the £3 ($3.69) tax on people of Indian origin. Preaching a strategy of satyagraha , or nonviolent protest, Gandhi organized a strike and led a march of more than 2,000 people to call for the tax to be scrapped. He was arrested and sent to prison for nine months. But his actions brought about the end of the tax and catapulted him to international attention.

Back in India, in 1915, Mahatma Gandhi founded an ashram , or spiritual monastery, open to all castes of people. He wore just a simple loincloth and shawl, and dedicated himself to prayer and fasting.

In 1919, when the British implemented laws that allowed for the arrest and imprisonment of anyone suspected of sedition, Gandhi rose up calling for a wave of nonviolent disobedience. Tragedy followed.

A massacre and a wave of boycotts

In the city of Amritsar, British Indian Army soldiers were ordered to open fire on a crowd of 20,000 or so protestors that had begun to grow unruly. Around 400 people were killed, with more than 1,000 injured . From that point on, Mahatma Gandhi’s goal was clear – Indian independence. He soon became a leading figure in the home-rule movement.

The movement called for mass boycotts of British goods and institutions. Gandhi implored civil servants to stop working for the British, for students to quit government schools, for soldiers to abandon their posts and for the citizenry to withhold their taxes and avoid buying British goods.

In 1922, he was arrested by the British authorities and pleaded guilty to three counts of sedition, which resulted in a six-year prison sentence, although that was commuted after just two years.

Britain’s strong grip on India was also evident in the Salt Act, which made it illegal for Indians to collect, produce or sell salt. Official sales of salt were also subject to tax. It was legislation that hit the poorest hardest. And so, in 1930, Mahatma Gandhi took on the Salt Act. The most well-known part of his campaign was the 390 kilometre Salt March to the shores of the Arabian Sea, where he collected salt in symbolic and open defiance of the government monopoly.

He wrote to the British viceroy, Lord Irwin, saying: “My ambition is no less than to convert the British people through non-violence and thus make them see the wrong they have done to India.”

The Salt Act protests gathered momentum and around 60,000 were imprisoned, including Gandhi.

Time magazine named him Man of the Year in 1930.

Real change

The following year, Mahatma Gandhi was invited to London on behalf of the Indian National Congress. He met King George V, and visited mill workers in Lancashire, gaining publicity and sympathy for his cause in the UK. But there was little in the way of progress and relations with Britain remained strained.

At the height of World War II, Mahatma Gandhi stepped up his Quit India campaign, urging the British to get out of the country altogether, while arguing that the war was none of India’s concern. Once again, he was arrested and jailed - this time along with fellow leaders of the Indian National Congress and his wife.

A change of government in Britain after the end of the war saw more willingness to discuss independence for India. But the negotiations that followed led to the partition of the country into India and Pakistan. On August 15, 1947, India gained its independence, Pakistan was born and millions of people were displaced and relocated, leading to waves of violence and killings.

The following year, on 30 January, 1948, Mahatma Gandhi was shot three times and killed by a Hindu extremist. Gandhi's dedication to nonviolent, anti-colonial protest has made him an inspirational figure for millions of people to this day.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on India .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Explainer: What is the European Free Trade Association?

Victoria Masterson

March 20, 2024

India is opening its space sector to foreign investment

February 28, 2024

Health tech: this is how we harness its potential to transform healthcare

Shakthi Nagappan

February 13, 2024

Buses are key to fuelling Indian women's economic success. Here's why

Priya Singh

February 8, 2024

India is making strides on climate policy that others could follow

Thomas Kerr

February 5, 2024

How collaborative action on smog could cast new light on India-Pakistan relations

Anurit Kanti, Muhammad Hassan Dajana and Syeda Hamna Shujat

January 29, 2024

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Mahatma Gandhi

By: History.com Editors

Updated: June 6, 2019 | Original: July 30, 2010

Revered the world over for his nonviolent philosophy of passive resistance, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was known to his many followers as Mahatma, or “the great-souled one.” He began his activism as an Indian immigrant in South Africa in the early 1900s, and in the years following World War I became the leading figure in India’s struggle to gain independence from Great Britain. Known for his ascetic lifestyle–he often dressed only in a loincloth and shawl–and devout Hindu faith, Gandhi was imprisoned several times during his pursuit of non-cooperation, and undertook a number of hunger strikes to protest the oppression of India’s poorest classes, among other injustices. After Partition in 1947, he continued to work toward peace between Hindus and Muslims. Gandhi was shot to death in Delhi in January 1948 by a Hindu fundamentalist.

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869, at Porbandar, in the present-day Indian state of Gujarat. His father was the dewan (chief minister) of Porbandar; his deeply religious mother was a devoted practitioner of Vaishnavism (worship of the Hindu god Vishnu), influenced by Jainism, an ascetic religion governed by tenets of self-discipline and nonviolence. At the age of 19, Mohandas left home to study law in London at the Inner Temple, one of the city’s four law colleges. Upon returning to India in mid-1891, he set up a law practice in Bombay, but met with little success. He soon accepted a position with an Indian firm that sent him to its office in South Africa. Along with his wife, Kasturbai, and their children, Gandhi remained in South Africa for nearly 20 years.

Did you know? In the famous Salt March of April-May 1930, thousands of Indians followed Gandhi from Ahmadabad to the Arabian Sea. The march resulted in the arrest of nearly 60,000 people, including Gandhi himself.

Gandhi was appalled by the discrimination he experienced as an Indian immigrant in South Africa. When a European magistrate in Durban asked him to take off his turban, he refused and left the courtroom. On a train voyage to Pretoria, he was thrown out of a first-class railway compartment and beaten up by a white stagecoach driver after refusing to give up his seat for a European passenger. That train journey served as a turning point for Gandhi, and he soon began developing and teaching the concept of satyagraha (“truth and firmness”), or passive resistance, as a way of non-cooperation with authorities.

The Birth of Passive Resistance

In 1906, after the Transvaal government passed an ordinance regarding the registration of its Indian population, Gandhi led a campaign of civil disobedience that would last for the next eight years. During its final phase in 1913, hundreds of Indians living in South Africa, including women, went to jail, and thousands of striking Indian miners were imprisoned, flogged and even shot. Finally, under pressure from the British and Indian governments, the government of South Africa accepted a compromise negotiated by Gandhi and General Jan Christian Smuts, which included important concessions such as the recognition of Indian marriages and the abolition of the existing poll tax for Indians.

In July 1914, Gandhi left South Africa to return to India. He supported the British war effort in World War I but remained critical of colonial authorities for measures he felt were unjust. In 1919, Gandhi launched an organized campaign of passive resistance in response to Parliament’s passage of the Rowlatt Acts, which gave colonial authorities emergency powers to suppress subversive activities. He backed off after violence broke out–including the massacre by British-led soldiers of some 400 Indians attending a meeting at Amritsar–but only temporarily, and by 1920 he was the most visible figure in the movement for Indian independence.

Leader of a Movement

As part of his nonviolent non-cooperation campaign for home rule, Gandhi stressed the importance of economic independence for India. He particularly advocated the manufacture of khaddar, or homespun cloth, in order to replace imported textiles from Britain. Gandhi’s eloquence and embrace of an ascetic lifestyle based on prayer, fasting and meditation earned him the reverence of his followers, who called him Mahatma (Sanskrit for “the great-souled one”). Invested with all the authority of the Indian National Congress (INC or Congress Party), Gandhi turned the independence movement into a massive organization, leading boycotts of British manufacturers and institutions representing British influence in India, including legislatures and schools.

After sporadic violence broke out, Gandhi announced the end of the resistance movement, to the dismay of his followers. British authorities arrested Gandhi in March 1922 and tried him for sedition; he was sentenced to six years in prison but was released in 1924 after undergoing an operation for appendicitis. He refrained from active participation in politics for the next several years, but in 1930 launched a new civil disobedience campaign against the colonial government’s tax on salt, which greatly affected Indian’s poorest citizens.

A Divided Movement

In 1931, after British authorities made some concessions, Gandhi again called off the resistance movement and agreed to represent the Congress Party at the Round Table Conference in London. Meanwhile, some of his party colleagues–particularly Mohammed Ali Jinnah, a leading voice for India’s Muslim minority–grew frustrated with Gandhi’s methods, and what they saw as a lack of concrete gains. Arrested upon his return by a newly aggressive colonial government, Gandhi began a series of hunger strikes in protest of the treatment of India’s so-called “untouchables” (the poorer classes), whom he renamed Harijans, or “children of God.” The fasting caused an uproar among his followers and resulted in swift reforms by the Hindu community and the government.

In 1934, Gandhi announced his retirement from politics in, as well as his resignation from the Congress Party, in order to concentrate his efforts on working within rural communities. Drawn back into the political fray by the outbreak of World War II , Gandhi again took control of the INC, demanding a British withdrawal from India in return for Indian cooperation with the war effort. Instead, British forces imprisoned the entire Congress leadership, bringing Anglo-Indian relations to a new low point.

Partition and Death of Gandhi

After the Labor Party took power in Britain in 1947, negotiations over Indian home rule began between the British, the Congress Party and the Muslim League (now led by Jinnah). Later that year, Britain granted India its independence but split the country into two dominions: India and Pakistan. Gandhi strongly opposed Partition, but he agreed to it in hopes that after independence Hindus and Muslims could achieve peace internally. Amid the massive riots that followed Partition, Gandhi urged Hindus and Muslims to live peacefully together, and undertook a hunger strike until riots in Calcutta ceased.

In January 1948, Gandhi carried out yet another fast, this time to bring about peace in the city of Delhi. On January 30, 12 days after that fast ended, Gandhi was on his way to an evening prayer meeting in Delhi when he was shot to death by Nathuram Godse, a Hindu fanatic enraged by Mahatma’s efforts to negotiate with Jinnah and other Muslims. The next day, roughly 1 million people followed the procession as Gandhi’s body was carried in state through the streets of the city and cremated on the banks of the holy Jumna River.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Indian J Med Res

- v.149(Suppl 1); 2019 Jan

LIFE OF M.K. GANDHI: A Message to Youth of Modern India

K.k. ganguly.

Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India

“Your beliefs become your thoughts. Your thoughts become your words. Your words become your actions. Your actions become your habits. Your habits become your values. Your values become your destiny.” – M.K. Gandhi

Today, the Indian youth is facing a hard time. After seven decades of independence the youth has become more morally, ethically, socially and spiritually adrift. The lack of sense of purpose is waning in comparison to what it was during pre-independence days. They feel alienated and frustrated. There are many reasons (both internal and external) for frustration and purposelessness.

Modernization combined with globalization has changed life in general and the lifestyle of youth in particular in the last few decades leading to change in social institutions and structures as well. Besides substantive demographic change in terms of population, political decadence, rising unemployment, and eroding value system combined with excessive market-oriented economy have made life very complicated for the new generation.

The changes affect the youth the most as the young mind is like a clean slate. If the youth is falling prey to a rapidly changing value system on one hand, they can also be molded by inculcating good thoughts, actions, habits and values on the other. The contemporary social milieu needs to be responsive to these expectations of the young mind so as to make them partner to over-all development and nation building.

In order to make the youth of modern India more actively engaged in nation-building, a force that has lot of zeal and purpose to do something, the present system needs to be all-encompassing to be able to move with the young and old with the right perspective. To achieve harmony among the young and old and seamlessly function as a vibrant society, the youth of our country need to become the engine of change.

In the same context, it is all the more essential that Gandhian values are inculcated among the youth in earnest so as to make them more vivacious and active for nation-building.

It will be prudent to understand the problems faced by ‘gen next’ before any steps can be taken to inculcate good values in youth and make them healthy partners in nation-building.

Mahatma Gandhi and grandson Kahandas (Kanaa, Kanu) watching an exercise of volunteers, 1937.

To address these issues, Gandhian philosophy is best suited for the present day situation and needs to be epitomized among the youth. The Gandhian perspective of a healthy and pious lifestyle may apparently look very mundane but in reality it is very effective and lasting in the long run. The young may instinctively be repulsive to such values but elders, teachers and, above all, parents need to help the youth to imbibe these values.

SUBSTANCE ABUSE AND ITS ILL EFFECT

To lead a life free of addiction, Gandhi suggested means and ways to youth in a very simple but effective manner.

Mostly young people depend on their peer groups and sometimes are led astray. They take to drugs, alcohol and watch adult content to spend their free time and negotiate their hurt feelings. As per WHO's latest report, per capita alcohol consumption has doubled in India from 2.4 litres in 2005 to 5.7 litres in 2016. Many of them are in a fix to distinguish between right and wrong deeds. The preoccupied adult most often cannot guide them at the right time and opportune moment, making it difficult for them to make the right choice and decision. Once the youth is in the vortex of addiction it becomes very difficult to get out of it.

Young people also get affected by the values of opulence and lifestyles of splurge in modern society and they try to adopt short cuts to attain material gains; failure to achieve pushes them into the world of drugs or crime.

Youths also get addicted to excessive digital usage. The technology provides immense help to the majority of our population but over-usage of cyber utilities has grown out of proportion and excess usage at times has proved fatal as well. Over-use of smart phones has not only physically harmed the youth to a large extent, it has also affected the mental ability and psychological status of youth. Some of them are indulging in cyber crimes. As cyber utilities are very handy and able to give desired outcomes without much effort, the young use it more frequently than it should be.

ISSUES WITH PRESENT DAY YOUTH WITH MODERN LIFESTYLE

- Substance abuse as self-deceiving eudemonia among most of the youth

- Early physical maturity causing various psycho-social ramifications

- Intolerance leading to violence in schools and colleges

- Materialism leading to hedonistic lifestyle

- Obesity mainly caused by irregular food habits combined with minimal to no physical exercise

- Education disparity

- Inadequate to no employment opportunities

*Consumed at least 60 grams or more of pure alcohol on at least one occasion in the past 30 days.

Source : WHO Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health, 2018.

As such, it is clear that both types of addictions help the youth to achieve desired ends without caring for means. The present generation feels that means are no longer important, it is the end that matters.

The Gandhian maxim of “means are more important than the end” implies that one needs to focus on the means, not merely the achievement of an end at any cost. To reiterate the practice of honest means for the desired end, we need to reinforce the fact that the use of drug or alcohol destroys the very core of our social institution and does not help to lead a successful life. A short cut to achieve pleasure and material gain and escape from the vagaries of life by use of addictives (both addictive substances or digital gadgets) cannot be good means for achieving good ends. To address the malady, Gandhiji suggested, the youth should take into consideration various dimensions of their conduct such as the social, cultural, and religious and they should also make sure that they are meaningfully engaged with the welfare of society. The youth is very vibrant and energetic, dynamic and capable of achieving, provided that they remain on the right track. Hence it is essential for them to use their energies in a positive manner to attain long-term happiness in their life and also contribute to the overall well-being of society.

EARLY PHYSICAL MATURITY

Attainment of puberty and adolescence brings different types of problems among the young, be it physiological, social or cultural. There are various environmental, biological and other factors promoting early onset of biological maturity. Biological maturity of youth needs to be harnessed for the good of the society. The absence of proper engagement with and guidance for such maturity among the young is worrisome and detrimental on many accounts. To address such changes in youth and active engagement thereof, the Gandhian tenet for them, ‘ satwik lifestyle’, can be of great help, where inward happiness is development, i.e. , it emphasizes the inclusion of basic human values. Right conduct refers to right practices accepted by society on the basis of righteous behavior by practicing obedience, etiquettes, fulfillment of social obligations, cooperation, sympathy, etc.

The youth of today is a victim of intolerance, impatience and of their own misjudged convictions as well. The traits of intolerance and impatience lead most of them on to a path of violence. A fast-moving society with compelling commitments often pushes them to a point of no return, thereby stoking destructive violent actions within themselves. The situation deteriorates further when the expectation bar of lifestyle attainments is raised and they are not able to deliver accordingly.

INTOLERANCE AND VIOLENCE

Gandhiji's belief and conviction regarding pacifying the element of impatience and intolerance of an individual is as true and effective today as it was during his time. Intolerance and violence are the two sides of the same coin. Gandhiji was a strong proponent of non-violence; he preached and practised non-violence against the British colonial power to get freedom for India. The trait of intolerance develops among the youth due to multifactorial disappointment, disenchantment and decadency in our system. The virtue of self-atonement as practised by Gandhiji on many occasions can be emulated by violent youth for solace. The practice of self-atonement needs to be encouraged by the elderly to set an example for today's intolerant youth.

In a recent report, India State Level Disease Burden on Suicides, it has been reported that 63 per cent of suicide deaths have been reported in the 15–39 age group and it constitutes the leading cause of deaths in this age group. However, suicide death rate has decreased significantly from 1990 to 2016 for women in the age group of 10–34 years.

MATERIALISM AND HEDONIST LIFE STYLE

Today's material world is encouraging good and bad among the youth. The brighter side of materialism is that the youth are encouraged to work hard to earn and thereby fulfill their wish list. But the negative side is a craving for material achievement, and it is spiraling up among today's youth with a rapid pace besides a tendency to be a go-getter without caring about the means of achievement. The concept of materialism drives the youth in all spheres, who mostly keeps eye on his western counterpart and their achievement. And in many cases it has become a blind aping of the west.

Endless craving for the accumulation of different items without any check or balance may enrich the individual momentarily. But the irony is that a materialistic tendency also compels the individual to get satiated soon with the possession and look for more and more new items of the material world. This attitude leads to hedonism. A hedonist does not go by any logic, rationale or need-based accrual of items. He is obsessed with procuring more and more and splurging is their way of living. More and more youth are slipping into such a quagmire.

Gandhiji has not only forewarned about the consequences of the phenomenon, he has also given alternatives to take care of such a situation. He pleaded for the voluntary reduction of our wants to a genuine level. He said that we should set a limit to our indulgence. According to Gandhiji, material wants dehumanize the individual, who puts a premium on body comforts to acquire all luxuries of life that money can buy and fails miserably in doing so. This is due to man's insatiable greed for earthly material possessions.

Gandhiji often said that one has to renounce his cravings and desire the contentment from within. It is said to be Samthistha or Sthitiprajana that can only help one to dissociate from materialism or hedonism; according to Gandhiji, to accumulate more than is required would be a sort of theft. The youth need to be endowed with values of Samthistha .

OBESITY AND JUNK FOOD

Everyone knows the old maxim ‘health is wealth’, and even then people in general and the youth at large seem to be indifferent to the saying. The culture of instant and fast food has been all-pervasive both in rural and urban areas. Most of the people want to take polished grains instead of non-polished ones. High fat and sugary diets are the in-thing for the present generation. The young generation wants to follow the path of least effort, i.e. , readymade wheat flour bags, half-baked package food (ready to eat) and so forth. Their minimal consumption of green leafy vegetables causes various digestive problems. The generation growing in such a kind of atmosphere tends to develop various diseases.

Gandhiji has talked at length regarding satwik food, which definitely takes care of obesity and allied maladies among youth. Though sometimes Gandhiji ate goat meat when he was young, he did not relish it at all and left it for good. He was also averse to cow or buffalo milk so he started goat milk with doctor's advice. Frugal eating behaviour was illustrated throughout his writings and discourses. It was not that he could not afford it, but his purposeful self-denial of a non-vegetarian diet, different hard and soft beverages, was to keep him morally clean and upright. Though the youth of today's generation may not be as austere as Gandhiji used to be, they can definitely emulate him on many counts regarding habits. Inculcation of Gandhian food habits can protect them from obesity and related ailments. It can keep them away from the craving of junk food. The elders need to walk the talk and set examples.

Age specific suicide death rates (SDR) and the percentage of total suicide death in each group. Source : Gender differentials and state variations in suicide deaths in India: the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2016. The Lancet (2018).

ICMR launched a diabetes registry in 2006 to map the pattern of youth-onset diabetes with relevance to geographical locations. Towards the end of the first phase in 2011, it was found that Type I diabetes was more prevalent than Type II diabetes.

EDUCATIONAL DISPARITY

The young generation of today is a victim of an education that gives a scroll certifying him to be worthy of the market and fending for himself. But the paradox of such a calibration of a student's intellect is questionable in itself. The simple reason for such confusion is a disparity in the process of teaching. Issues like disparity in education and unemployment among the youth are a matter of real concern. A nation of our stature cannot remain a mute spectator of the abysmal status of our academic system. Gandhiji dreamt of an academic system that would make the youth self-reliant and not dependent on their employer. The current education system segregates between public and private schooling. It is universally known that students educated from private schools are mostly comfortably placed (much costlier education) in all spheres of life in comparison to those who have been educated in government schools. In most of the cases, public school education cannot instill self-confidence in their wards. The disparity becomes glaring between the two types of youth while both are contesting for a common goal.

Greyville Cricket Club, Durban. Seated fourth from left: Parsee Rustomjee next to Mahatma Gandhi, 1913.

Healthy competition is always a good option but the present system of education is churning out competitors of uneven academic prowess. The Gandhian principle of education may help resolve this kind of disparity, maybe not fully, but to a large extent. Gandhiji believed education should be value-based and mass-oriented.

He insisted on imparting vocational training to youth so that they can become self-reliant with such training, with education linked with practical experience. Probably the disparity reflects upon our inability to make education truly national in nature and spirit. Gandhiji always advocated for a true, national education. True education develops a balanced intellect and, according to Gandhiji, a balanced intellect presupposes a harmonious growth of body, mind and soul.

An educated youth is the heart and soul of a nation. To make them truly educated, the curriculum needs reorientation at this juncture. The Gandhian spirit of overall development of the youth comprises education that stresses on mental, physical spiritual, social and economic values of life. And today's education is bereft of many of the said values.

Gandhiji used to say: “Education should not end with childhood as adult education plays an equally vital role in the development of an individual.” And a regular learning habit not only helps a man to negotiate with the ups and downs of life but also makes him an able navigator in the sea of life.

EMPLOYMENT SCARCITY

One of the most serious concerns is major unemployment among the youth in our country. It does not matter much whether the youth is formally educated or not. The employment market is unable to keep pace with ever growing job-seekers. However, a miniscule number of appropriately trained job-seekers still get jobs. The major factors for such kinds of anomalies are many but one of the key factors is a market-naive education system. The training imparted to the youth in their academic career is mostly archetypical and is not commensurate with the requirements of national or international job markets. The current situation warrants a considerable reorientation exercise in the education system, and also demands entrepreneurs to be hoisted to take care of job requirements both at the national and local level.

Gandhiji always did advocacy for sound vocational training for boys and girls. He felt that a large section of our country lives in villages and that there are various jobs that need skills of village youths (best suited for a village situation). If the youth of rural India develop different sorts of skills, they will not only generate employment for themselves, but they will be able to employ their fellow villagers as well. The irony of the current employment market is a systematic waning of rural-based employment. Hence the introduction of modern skills like digitization (it is good technology – if launched in right earnest, in consonance with local needs) of most of the sectors. Thus a major section of our youth and master of those (rural crafts) skills are in oblivion as they have not been trained with modern technology-based rural jobs.

The next generation needs to be savvy with modern science and technology to keep pace with modern-day development on one hand and on the other they need to acquire those social values for which Gandhiji fought throughout his life. The youth of the nation need to inculcate the values they should have for respect and regard for the elderly and truth, and retain the values of existing social institutions as institutions are the scaffolding of any culture. They should not get into the traps of caste or creed, neither allow anyone to exploit such issues for petty gains.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT & SPONSORSHIP:

Conflicts of interest:.

notes on art in a global context

Gandhi’s Buildings and the Search for a Spiritual Modernity

Riyaz Tayyibji

January 9, 2019

Riyaz Tayyibji considers the little-known architectural collaborations of Mahatma Gandhi, charismatic leader of the Indian freedom movement, in light of discourses of modern architecture. Weaving in discussions of phenomenology, material, and a discipline of privacy, the essay explores aspects of Gandhi’s philosophical and political thinking that propose a notion of the modern with an ethical and spiritual underpinning for 20th century architectural practice.

There are many things that Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (1869–1948), the “Mahatma” or more fondly “Bapu,” is known for, but architecture is not part of the standard mythos. Gandhi, however, did consider building to be an extension of his engagement with different materials, which he began at an early age. His first experiments were with food, and later, he taught himself carpentry and to work with leather. He was particularly interested in materiality, the relationship between material, its processing and production with labor and the human body. He taught himself to spin cotton, an activity that he personally undertook daily, and then promoted societally, which had large economic and political implications during the Indian independence movement. Gandhi sitting at his spinning wheel is an iconic portrait. His engagement with materials and how they are processed was not a casual one. 1 Gandhi referred to all his praxes as “experiments.” The English title of his autobiography, An Autobiography or The Story of My Experiments with Truth , gives insight into the depth and breadth of the manner in which he considered these engagements. Though sceptical of the scientific worldview of the Enlightenment for separating the subjective and the objective, he nevertheless borrowed from this paradigm, appropriating the method of the experiment and following it meticulously: setting up hypotheses, undertaking experiments, and searching for verification. Gandhi carried out experiments in his inner world (in his search for truth) and in the outer world (through his engagement with material). For him, the human body is the instrument that mediates between these two worlds, allowing for the inner to be verified by the outer, and vice versa. For this epistemological machine to work, Gandhi knew that a complete transparency between one’s inner and the outer worlds was necessary. M. K. Gandhi, An Autobiography or The Story of My Experiments with Truth , trans. Mahadev Desai (Ahmedabad: Navajivan Press), https://gandhiheritageportal.org/mahatma-gandhi-books/the-story-of-my-experiments-with-truth#page/1/mode/2up ). He mastered leatherwork and carpentry and even made highly technical innovations to the spinning wheel. 2 Gandhi developed a twelve-spindle charkha (spinning wheel), and a portable “Yerawada” charkha that allowed him to spin while traveling. He also made changes to improve the aerodynamics of the wheel. One should expect, then, an equally careful examination of architectural praxes in his experiments with built forms.

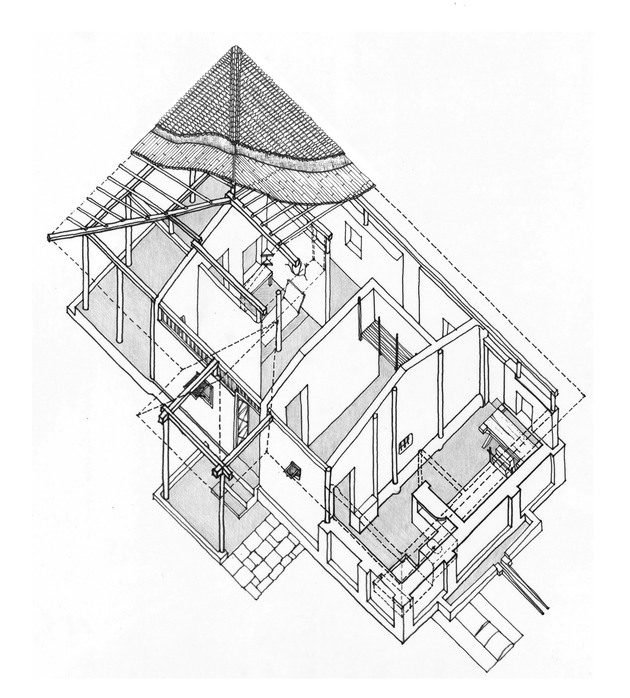

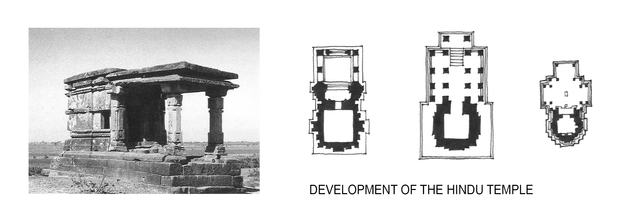

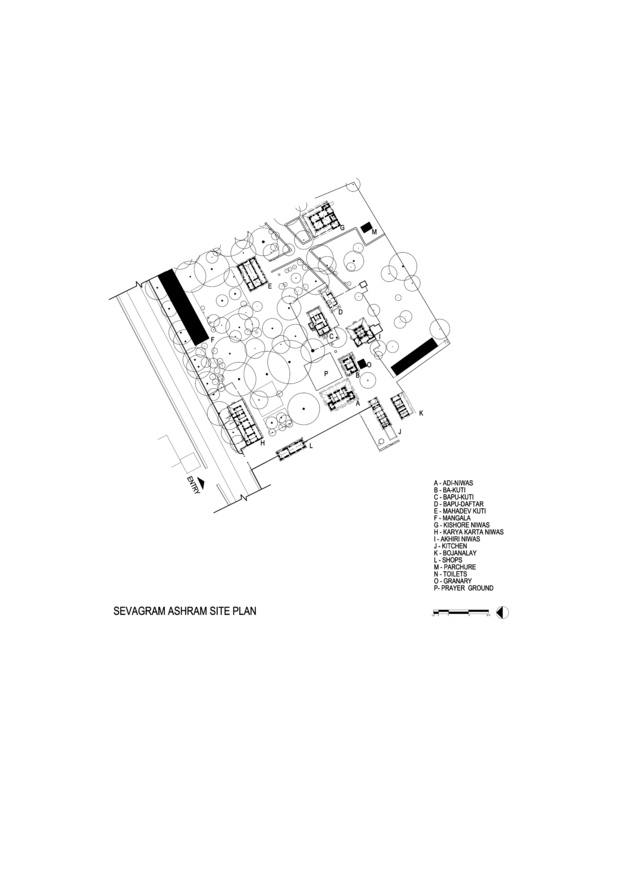

Though Gandhi is unequivocally among the greatest modern thinkers, his buildings have largely been looked upon as conservative, rural, and vernacular. Ironically, it is their materiality that has perpetuated this reading. 3 The manner in which the discourse on modern architecture itself has been historically constructed foregrounds material technology and its production (industry). Given that more than 80 percent of India was rural and agricultural at the time, Gandhi saw no virtue in premising modern interventions into these contexts on such ideas. He did, however, see value in the ideas of the individual, health and hygiene, education, and dialogue. Gandhi, though critical of the European secular, scientific Enlightenment as a whole, felt no hesitation in borrowing ideas and practices from it that he thought were useful—or in discarding those that he considered destructive. He, in fact, categorically states that nothing he has thought or done is original, and he is completely transparent in crediting antecedents. M. K. Gandhi, An Autobiography or The Story of My Experiments with Truth , trans. Mahadev Desai (Ahmedabad: Navajivan Press, https://gandhiheritageportal.org/mahatma-gandhi-books/the-story-of-my-experiments-with-truth#page/1/mode/2up ). A Gandhian modernity encourages a mix and match of ideas, on the assumption that these ideas arise in response to an internal inquiry and conversation with oneself. He then vehemently opposes the notion that any one fixed set of ideas (i.e., ideology) is inherently superior to any other. Gandhi’s buildings then question the hegemony of the idea of material technology in determining modern architecture. Quite simply, Gandhi’s buildings are modern in spite of the materials from which they are made, though the nature of their modernity may not be obvious. Given Gandhi’s criticism of industrial production processes, modern materials such as concrete and steel are, not surprisingly, absent from his architecture. With his economic and political thinking centered on the village and rural agricultural environments, the idea of the modern city was immaterial. 4 For Gandhi, the city is a place of violence. He proposed the “ashram” as a form of settlement pattern. This is not the ashram of antiquity but rather a community of satyagrahis, or searchers of truth, living together and “experimenting” toward a nonviolent existence. This form of ashram consists of a residential area, a communal kitchen and dining hall, an open-to-sky prayer space, along with an institutional area housing schools and other training sites. Areas are demarcated for agriculture, animal husbandry, dairy, and food processing. A separate area is allotted for international ashramites, volunteers, and visiting guests. Gandhi’s buildings lie outside the matrix of material technology and urbanity that defines modern Euro-American architecture. And yet they are considerable departures from the traditional structures they appear to resemble. This break is rooted in the ideas that shaped Indian modernity in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and that matured through Gandhi’s experimentations. These ideas relate to individuality, hygiene, movement, locality, and, among other things, a reconfiguration of the domestic that constitutes an “opening up.” 5 In this essay, I use the term “opening up” to describe both an internal, mental, and psychological reconfiguration arising from systematic inquiry, experimentation, and verification, and a material one—referring to the increased porosity of an architectural configuration. Buildings using mud and masonry are load bearing by nature, where the configuration of the walls defines the structure. These are unlike the frame structures built with modern materials, such as reinforced cement concrete (RCC) and steel, which free the walls from the logic of gravity and, therefore, allow for “free” compositioning. Compositioning allows for transparency, whereas configurations of load-bearing walls allow for varying porosity. I have called an increase in porosity an “opening up.” For Gandhi, this external, material opening up can only follow an internal one. A societal opening up would follow the same logic: A society can only move away from dogmatisms and the darkness of a blind following of unverified ritual and habit through a wilful internal transformation within each individual member of that society. For it to happen any other way would involve the false or the violent, both of which Gandhi considered immoral. In this essay, I concentrate on the implications of opening up and the idea of the individual particular to Gandhi’s thinking. Considering the scope of this essay, other ideas, including those surrounding hygiene, domesticity, and movement are referred to in passing, however, they are not discussed in detail. Given the inherent contradiction in architectural discourse between the categories of “vernacular” and “modern,” particularly in political and economic terms, it becomes important to observe Gandhi’s as an architecture that is simultaneously both. It follows to inquire about the implications of his architecture and the nature of its modernity.

Gandhi proposed a modernity premised on inward inquiry, or a form of inquiry directed toward the self, rather than the outward-looking trajectory of phenomenal observation that so fueled the Enlightenment project. 6 By ‘modernity’, I mean the conditions and qualities necessary for being modern. Gandhi refuted the possibility that a universal set of conditions could be considered modern. He felt that the European conditions of being modern had limited significance in the Indian cultural context. Others, most notably Ashis Nandy, have attempted to construct the outlines of what a Gandhian modernity could be. Such a modernity, Gandhi believed, could only come from scrutinizing one’s own experiences, the particularities of one’s own circumstances, and their reality as lived experience with a significant openness between one’s private and public selves. 7 Gandhi seems to have recognized that, in a world where there are no existential boundaries, the only reality that one can consider “firm” is that which is closest to us, i.e., that which is experienced directly. In this world of an atomized, individuated society, the onus to find an ethical and moral framework lies with the individual, and thus one must find this for oneself in the scientific manner of inquiry, i.e., through “experiments.” In his autobiography, he provides a careful account of his youth, namely of the people and events that were the substance on which his physical, intellectual, philosophical, and spiritual development is based. 8 Gandhi, An Autobiography or The Story of My Experiments with Truth, 11–51. For Gandhi, this development is driven by the internal conversation one has with oneself. To have this conversation, one must first be able to listen to the “small, still voice” within. 9 For a discussion of Gandhi’s relationship with his “small, still voice,” see Tridip Suhrud, introduction to An Autobiography or The Story of My Experiments with Truth : Critical Edition, by M. K. Gandhi, trans. Mahadev Desai (New Delhi: Penguin Random House, 2018), 1–35, esp. 16, 22. Indeed, it is the ability to hear this voice, to have this conversation, that allows one to emerge as an individual—and thus to be modern. Gandhi understood the purpose of this internal conversation to be the search for integrity and truth, for self-knowledge and self-awareness. Self-recognition, for him, is the basis of self-control. As the cultural historian and Gandhian scholar Tridip Suhrud writes, “His [Gandhi’s] idea of civilization is based on this possibility of rule over the self.” 10 Ibid., 6. Open dialogue first with oneself and then with the other is the keystone of his praxis of nonviolence, or ahimsa . For to Gandhi, a disintegrated self is amoral and unethical and leads to ignorance of the self, which in turn paves the way to violence. This is also Gandhi’s most scathing critique of the Western secular-scientific worldview, which he believed led directly to violence through a consciousness that isolates cognition from feelings and ethics, and partitions man from the subjects of inquiry emotionally. 11 Ashis Nandy, “From Outside the Imperium: Gandhi’s Cultural Critique of the West,” in Traditions, Tyranny and Utopias: Essays in the Politics of Awareness (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1987), 130–31. This is the state of the technologist, whose individuality is robbed of the possibility of salvation through personal searching. For Gandhi, a modernity without the possibility of transcendence is an amoral modernity. The possibility of transcendence is embedded in the correct enactment of daily practices toward spiritual liberation and not in a longed-for utopia. 12 Gandhi’s daily practices included eating, bathing, reading, writing, spinning, visiting the sick (those stricken with leprosy), and praying. He thought carefully about these activities, and sought the spiritual possibilities within each one. With this understanding, he elevated everyday activities to the level of rituals that would aid him along his path to moksha , or self-realization. He did not feel the need for any extraneous activity. See Mahadev Desai, “A Morning with Gandhiji,” November 13, 1924, in Young India, 1924–1926 , by Mahatma Gandhi (Madras: S. Ganesan, 1927), 1025: “There are two aspects of things,—the outward and the inward. It is purely a matter of emphasis with me. The outward has no meaning except in so far as it helps the inward.” Gandhi argued that there are moments, however rare, when one’s communion with oneself is so complete that one feels no need for any outward expression, including art. Tridip Suhrud, “Towards a Gandhian Aesthetics: The Poetics of Surrender and the Art of Brahmacharya,” in The Bloomsbury Research Handbook of Indian Aesthetics and the Philosophy of Art , ed. Arindam Chakrabarti (New York: Bloomsbury, 2016), 374. It follows that Gandhi considers inner transformation at the individual scale as the engine for political revolution at the societal scale.

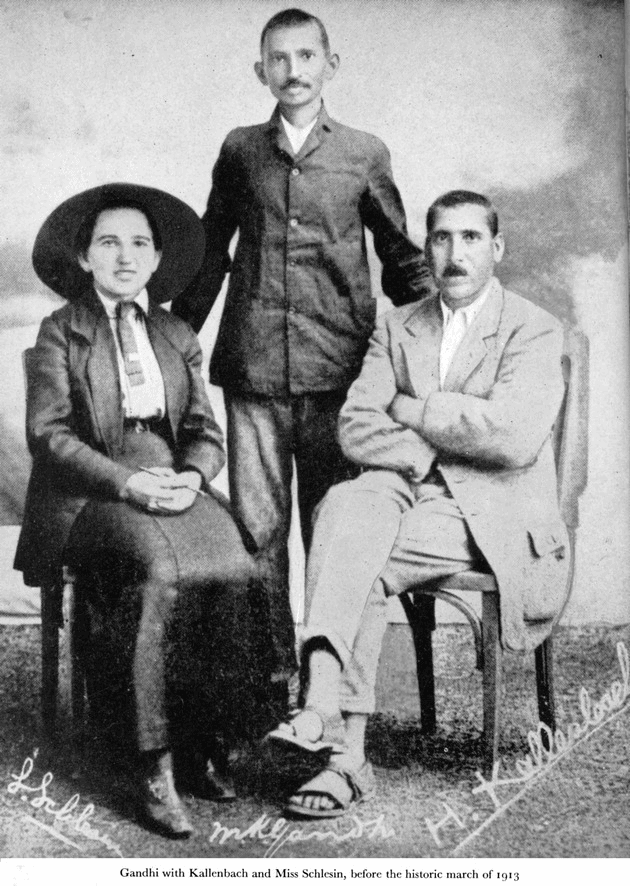

Gandhi’s first experience of working with building materials was in South Africa, where he constructed the shed to house the printing press for the Indian Opinion at Phoenix settlement. 13 By 1903, a core group of people of varied races and religious dispositions rallied around Gandhi, supporting him in his agitations against racial discrimination in South Africa. This led to the founding of the Natal Indian Congress, which Gandhi would soon lead. In the same year, he started the Indian Opinion , the journal that became the voice of the Indian community in South Africa. Gandhi had been thinking about communal living for several years up to then. In 1904, with the journal’s financial struggles and his serendipitous reading of John Ruskin’s Unto This Last , he was inspired to act on his thoughts of communal living and to buy a farm near the station of Phoenix, on the north coastline fourteen miles from Johannesburg. Both the printing press and operating staff were housed on the farm, “where the workers could live a more simple and natural life and the ideas of Ruskin and Tolstoy combined with strict business principles.” Ramachandra Guha, Gandhi Before India (New Delhi: Penguin Random House, 2013), 175. Needless to say, the production costs of the journal were reduced considerably. In addition, Gandhi would use the farm to articulate and sharpen his ideas about communal living, and satyagraha. It was at Phoenix settlement in 1906 that Gandhi would take his pledge of brahmacharya , or voluntary celibacy. The inhabitants of the settlement had built their own houses, and though Gandhi only moved there in 1913, his family lived there and he visited them regularly. A few years later, Gandhi moved into “The Kraal,” a house designed and built by his lifelong friend, ”soulmate,” and patron, the architect Hermann Kallenbach. 14 See Shimon Lev, Soulmates: The Story of Mahatma Gandhi and Hermann Kallenbach (New Delhi: Orient Black Swan, 2012), which discusses the relationship between Gandhi and Kallenbach in detail. This house had a thatched roof and was based on a configuration of vernacular African building elements. It was unusual for a European to live in such a house at the time. 15 Before living with Kallenbach, Gandhi and his wife had lived with Millie and Henry Polak. It was unusual for mixed-race couples to live together in a city such as London in any case; however, in South Africa, it was downright revolutionary. Moreover, for two men to live together could not have been looked upon as anything but heretical. As the Indian historian Ramachandra Guha writes, “For Gandhi to befriend Polak, Kallenbach, West and company was an act of bravery; for them to befriend Gandhi was an act of defiance.” Guha, Gandhi Before India , 188. Gandhi and Kallenbach lived together for five years: first at The Kraal, then in canvas tents at Fairview, and finally at Tolstoy Farm, where once again Gandhi was involved in building. 16 Gandhi was involved in both the conceptualization and the construction of the buildings at Tolstoy Farm. His direct involvement in the construction was reduced after his time in South Africa. The buildings of the ashrams in India were built by important people at each ashram. Gandhi directed them by setting material and budget constraints, and the buildings were constructed under his supervision. His house Bapu Kutir at the Sevagram Ashram at Wardha was built by the British-born activist Mirabehn (Madeleine Slade) originally for herself. However, Gandhi did insist that it cost no more than Rs. 500 to build and that the sky be visible from within. Given his own experimentation with materials and the pair’s close friendship, Gandhi likely picked up a great deal about construction from the architect. Kallenbach was a partner in a successful Johannesburg practice and designed sophisticated buildings across the town. 17 Hermann Kallenbach (1871–1945) was an architect who studied in both Stuttgart and Munich. He was a master craftsman, having trained and practiced as a carpenter. He arrived in South Africa at the behest of his uncles, who were in the construction industry. Initially, he formed a practice with A. Stanley Reynolds (1911–1971), with whom he built The Kraal. He then set up the firm Kallenbach, Kennedy & Furner, which was enormously influential in the development of Johannesburg up to 1945. He has been described by the South African architectural researcher Kathy Munro as a “property tycoon. See Kathy Munro, “Review of ‘Soulmates—The Story of Mahatma Gandhi and Hermann Kallenbach,’” Heritage Portal , July 3, 2017, http://www.theheritageportal.co.za/review/review-soulmates-story-mahatma-gandhi-and-hermann-kallenbach . He generously used his wealth to finance Gandhi’s antiracism activities, which resonated with him, most notably donating more than a thousand acres of land for Tolstoy Farm. After Gandhi’s departure from South Africa, Kallenbach was involved in supporting the Zionist movement. Nonetheless, Gandhi did not find it difficult to convince the tall, sports-loving, hedonistic Lithuanian to give himself over to a life of simplicity. The buildings at Tolstoy Farm consisted of three simple sheds: two about fifty-three feet in length and a third larger one, which, close to seventy-seven feet, housed a school. Each shed had a veranda running along its length, with the interior spaces enclosed by donated corrugated sheets of iron. 18 Tolstoy Farm was established in 1910, when Hermann Kallenbach acquired a farm at Lawley near Johannesburg and donated it to the satyagraha movement, then in its final stage. It was Kallenbach who named the farm after Leo Tolstoy. Gandhi wrote in a letter to Tolstoy, dated August 15, 1910, “No writings have so deeply touched Mr. Kallenbach as yours and, as a spur to further effort in living up to the ideals held before the world by you, he has taken the liberty, after consultation with me, of naming his farm after you.” M. K. Gandhi to Count Leo Tolstoy, 15 August 1910, in Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi , vol. 10, November 1909–March 1911 (New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India), 306-7, https://gandhiheritageportal.org/cwmg_volume_thumbview/MTA=#page/346/mode/2up . See also Eric Itzkin, Gandhi’s Johannesburg: Birthplace of Satyagraha , Frank Connock Publication no. 4 (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 2000), 78. The farm was 1100 acres. It was covered with 1000 fruit trees and included two wells and a small spring. At its height, the farm supported a community of eighty people: fifty adults as well as thirty children, who studied at its school. The farm, as Gandhi would write in 1914, was of great use in the training of the thousands of passive resisters who participated in the last phase of the struggle. Shriman Narayan, ed., Selected Works of Mahatma Gandhi, vol. 3, Satyagraha in South Africa (Ahmedabad: Navajivan Publishing House, 1968), 352. See also https://www.mkgandhi.org/museum/phoenix-settlement-tolstoy-farm.html . At both the Phoenix settlement and Tolstoy Farm, Gandhi had wanted to build with mud and thatch. However, resistance from other community members prevented him from doing so. 19 Though by 1904 Gandhi was a successful lawyer able to donate £3500 to the running of his press and Tolstoy Farm, he himself lived a frugal life and expected those associated with him to do the same. He was hardest on the people closest to him, particularly his family. The Polaks, with whom he stayed, were also subject to his austerity. Millie Polak wanted to make the bare little house they shared a home by giving it a touch of warmth with the use of carpets and curtains. Gandhi was unconvinced of such expenditure, which he felt would be better focused on the cause they were fighting for. Once when she suggested that a painting might do well to hide the ugliness of the yellow washed walls, he suggested she look out of the window at the sunset, which is more beautiful than anything that could be drawn by the hand of man. Guha, Gandhi Before India , 199–200. See also Itzkin, Gandhi’s Johannesburg , 69. Though he did give in to Millie Polak on this occasion, such differences about comfort were constant between Gandhi and those working with him at both the Phoenix settlement and Tolstoy Farm. At both places, Gandhi had wanted the residential buildings to be Spartan, made of the most rudimentary and basic materials, which the other community members refused to do. They finally built their homes in a more modern and comfortable manner, using commonly available timber frames. As Millie Polak recalled, “His bent was naturally towards the ascetic and not towards the aesthetic.” 20 Millie Graham Polak, Mr. Gandhi: The Man (Bombay: Vora & Co., 1949), 67.

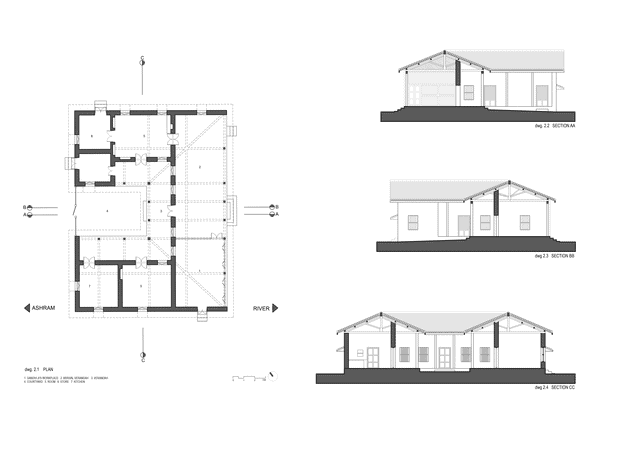

Gandhi’s ideas with respect to building materials would find fruition upon his return to India in the construction of his ashrams. The buildings of the Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, a state in western India, were made from burnt brick, sawn timber, and handmade country tiles, and are referred to, in local terminology, as pucca , or proper/permanent buildings. 21 Gandhi established his first ashram in Ahmedabad at Kochrab using an existing building and property gifted to him by his close friend, the barrister Jivanlal Desai. However, the need for more space to accommodate all of the agricultural activities of the ashram pushed Gandhi to relocate. This time, he chose a place on the banks of the Sabarmati River, from which the second ashram gets its name (it was originally called the Satyagraha Ashram). Gandhi stayed at the Sabarmati Ashram from 1917 to 1930, when it was one of the main centers of the independence movement. It was from there that he set out on his famous Salt March to Dandi and vowed not to return till India had gained its independence. The terms pucca and kachcha originally related to food. Cooked food is considered pucca , while that which is eaten raw—such as a fruit—or a vegetable that hasn’t matured is considered kachcha . It is common parlance to apply these words beyond the realm of food, however. For example, an asphalt road is considered pucca while an unpaved country track would be called kachcha . Pucca implies the application of artificial energy to process material, i.e., the more pucca or permanent, the more energy has been used for the material’s stability and durability and hence perceived permanence. It is interesting to note here that in Gandhi’s experiments with his diet, he had moved to a diet of largely kachcha food. According to Indian historian Ramachandra Guha, “One of his [Gandhi’s] favorite authors, the anti-vivisectionist doctor Anna Kingsford, claimed that a fruit-based diet was man’s genetic inheritance.” Guha, Gandhi Before India , 189–90. However, Gandhi found Hriday Kunj, his own house at the ashram, excessive. He thought it too big and unnecessarily complex. At his second ashram, Sevagram Ashram at Wardha, near Nagpur in central India, the buildings are much simpler and made from materials found within a fifty-mile radius. Consequently, the buildings there have stone plinths, and the walls are made of a local mud called “ garhi mitti ” mixed with water, cow dung, wheat husk, and hay, the latter serving as a binder and insulation. Columns of un-sawn sagwan wood hold up the roof structure, which is covered with bamboo matting and clay country tiles. These buildings were self-built—unlike the pucca buildings at the Sabarmati Ashram—and are, in contrast, considered kachcha , or raw.