Earthquake Essay for Students and Children

500+ Words Essay on Earthquake

Simply speaking, Earthquake means the shaking of the Earth’s surface. It is a sudden trembling of the surface of the Earth. Earthquakes certainly are a terrible natural disaster. Furthermore, Earthquakes can cause huge damage to life and property. Some Earthquakes are weak in nature and probably go unnoticed. In contrast, some Earthquakes are major and violent. The major Earthquakes are almost always devastating in nature. Most noteworthy, the occurrence of an Earthquake is quite unpredictable. This is what makes them so dangerous.

Types of Earthquake

Tectonic Earthquake: The Earth’s crust comprises of the slab of rocks of uneven shapes. These slab of rocks are tectonic plates. Furthermore, there is energy stored here. This energy causes tectonic plates to push away from each other or towards each other. As time passes, the energy and movement build up pressure between two plates.

Therefore, this enormous pressure causes the fault line to form. Also, the center point of this disturbance is the focus of the Earthquake. Consequently, waves of energy travel from focus to the surface. This results in shaking of the surface.

Volcanic Earthquake: This Earthquake is related to volcanic activity. Above all, the magnitude of such Earthquakes is weak. These Earthquakes are of two types. The first type is Volcano-tectonic earthquake. Here tremors occur due to injection or withdrawal of Magma. In contrast, the second type is Long-period earthquake. Here Earthquake occurs due to the pressure changes among the Earth’s layers.

Collapse Earthquake: These Earthquakes occur in the caverns and mines. Furthermore, these Earthquakes are of weak magnitude. Undergrounds blasts are probably the cause of collapsing of mines. Above all, this collapsing of mines causes seismic waves. Consequently, these seismic waves cause an Earthquake.

Explosive Earthquake: These Earthquakes almost always occur due to the testing of nuclear weapons. When a nuclear weapon detonates, a big blast occurs. This results in the release of a huge amount of energy. This probably results in Earthquakes.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Effects of Earthquakes

First of all, the shaking of the ground is the most notable effect of the Earthquake. Furthermore, ground rupture also occurs along with shaking. This results in severe damage to infrastructure facilities. The severity of the Earthquake depends upon the magnitude and distance from the epicenter. Also, the local geographical conditions play a role in determining the severity. Ground rupture refers to the visible breaking of the Earth’s surface.

Another significant effect of Earthquake is landslides. Landslides occur due to slope instability. This slope instability happens because of Earthquake.

Earthquakes can cause soil liquefaction. This happens when water-saturated granular material loses its strength. Therefore, it transforms from solid to a liquid. Consequently, rigid structures sink into the liquefied deposits.

Earthquakes can result in fires. This happens because Earthquake damages the electric power and gas lines. Above all, it becomes extremely difficult to stop a fire once it begins.

Earthquakes can also create the infamous Tsunamis. Tsunamis are long-wavelength sea waves. These sea waves are caused by the sudden or abrupt movement of large volumes of water. This is because of an Earthquake in the ocean. Above all, Tsunamis can travel at a speed of 600-800 kilometers per hour. These tsunamis can cause massive destruction when they hit the sea coast.

In conclusion, an Earthquake is a great and terrifying phenomenon of Earth. It shows the frailty of humans against nature. It is a tremendous occurrence that certainly shocks everyone. Above all, Earthquake lasts only for a few seconds but can cause unimaginable damage.

FAQs on Earthquake

Q1 Why does an explosive Earthquake occurs?

A1 An explosive Earthquake occurs due to the testing of nuclear weapons.

Q2 Why do landslides occur because of Earthquake?

A2 Landslides happen due to slope instability. Most noteworthy, this slope instability is caused by an Earthquake.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

- CBSE Class 10th

- CBSE Class 12th

- UP Board 10th

- UP Board 12th

- Bihar Board 10th

- Bihar Board 12th

- Top Schools in India

- Top Schools in Delhi

- Top Schools in Mumbai

- Top Schools in Chennai

- Top Schools in Hyderabad

- Top Schools in Kolkata

- Top Schools in Pune

- Top Schools in Bangalore

Products & Resources

- JEE Main Knockout April

- Free Sample Papers

- Free Ebooks

- NCERT Notes

- NCERT Syllabus

- NCERT Books

- RD Sharma Solutions

- Navodaya Vidyalaya Admission 2024-25

- NCERT Solutions

- NCERT Solutions for Class 12

- NCERT Solutions for Class 11

- NCERT solutions for Class 10

- NCERT solutions for Class 9

- NCERT solutions for Class 8

- NCERT Solutions for Class 7

- JEE Main 2024

- MHT CET 2024

- JEE Advanced 2024

- BITSAT 2024

- View All Engineering Exams

- Colleges Accepting B.Tech Applications

- Top Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in India

- Engineering Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Engineering Colleges Accepting JEE Main

- Top IITs in India

- Top NITs in India

- Top IIITs in India

- JEE Main College Predictor

- JEE Main Rank Predictor

- MHT CET College Predictor

- AP EAMCET College Predictor

- GATE College Predictor

- KCET College Predictor

- JEE Advanced College Predictor

- View All College Predictors

- JEE Main Question Paper

- JEE Main Cutoff

- JEE Main Advanced Admit Card

- AP EAPCET Hall Ticket

- Download E-Books and Sample Papers

- Compare Colleges

- B.Tech College Applications

- KCET Result

- MAH MBA CET Exam

- View All Management Exams

Colleges & Courses

- MBA College Admissions

- MBA Colleges in India

- Top IIMs Colleges in India

- Top Online MBA Colleges in India

- MBA Colleges Accepting XAT Score

- BBA Colleges in India

- XAT College Predictor 2024

- SNAP College Predictor

- NMAT College Predictor

- MAT College Predictor 2024

- CMAT College Predictor 2024

- CAT Percentile Predictor 2023

- CAT 2023 College Predictor

- CMAT 2024 Admit Card

- TS ICET 2024 Hall Ticket

- CMAT Result 2024

- MAH MBA CET Cutoff 2024

- Download Helpful Ebooks

- List of Popular Branches

- QnA - Get answers to your doubts

- IIM Fees Structure

- AIIMS Nursing

- Top Medical Colleges in India

- Top Medical Colleges in India accepting NEET Score

- Medical Colleges accepting NEET

- List of Medical Colleges in India

- List of AIIMS Colleges In India

- Medical Colleges in Maharashtra

- Medical Colleges in India Accepting NEET PG

- NEET College Predictor

- NEET PG College Predictor

- NEET MDS College Predictor

- NEET Rank Predictor

- DNB PDCET College Predictor

- NEET Admit Card 2024

- NEET PG Application Form 2024

- NEET Cut off

- NEET Online Preparation

- Download Helpful E-books

- LSAT India 2024

- Colleges Accepting Admissions

- Top Law Colleges in India

- Law College Accepting CLAT Score

- List of Law Colleges in India

- Top Law Colleges in Delhi

- Top Law Collages in Indore

- Top Law Colleges in Chandigarh

- Top Law Collages in Lucknow

Predictors & E-Books

- CLAT College Predictor

- MHCET Law ( 5 Year L.L.B) College Predictor

- AILET College Predictor

- Sample Papers

- Compare Law Collages

- Careers360 Youtube Channel

- CLAT Syllabus 2025

- CLAT Previous Year Question Paper

- AIBE 18 Result 2023

- NID DAT Exam

- Pearl Academy Exam

Predictors & Articles

- NIFT College Predictor

- UCEED College Predictor

- NID DAT College Predictor

- NID DAT Syllabus 2025

- NID DAT 2025

- Design Colleges in India

- Fashion Design Colleges in India

- Top Interior Design Colleges in India

- Top Graphic Designing Colleges in India

- Fashion Design Colleges in Delhi

- Fashion Design Colleges in Mumbai

- Fashion Design Colleges in Bangalore

- Top Interior Design Colleges in Bangalore

- NIFT Result 2024

- NIFT Fees Structure

- NIFT Syllabus 2025

- Free Design E-books

- List of Branches

- Careers360 Youtube channel

- IPU CET BJMC

- JMI Mass Communication Entrance Exam

- IIMC Entrance Exam

- Media & Journalism colleges in Delhi

- Media & Journalism colleges in Bangalore

- Media & Journalism colleges in Mumbai

- List of Media & Journalism Colleges in India

- CA Intermediate

- CA Foundation

- CS Executive

- CS Professional

- Difference between CA and CS

- Difference between CA and CMA

- CA Full form

- CMA Full form

- CS Full form

- CA Salary In India

Top Courses & Careers

- Bachelor of Commerce (B.Com)

- Master of Commerce (M.Com)

- Company Secretary

- Cost Accountant

- Charted Accountant

- Credit Manager

- Financial Advisor

- Top Commerce Colleges in India

- Top Government Commerce Colleges in India

- Top Private Commerce Colleges in India

- Top M.Com Colleges in Mumbai

- Top B.Com Colleges in India

- IT Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- IT Colleges in Uttar Pradesh

- MCA Colleges in India

- BCA Colleges in India

Quick Links

- Information Technology Courses

- Programming Courses

- Web Development Courses

- Data Analytics Courses

- Big Data Analytics Courses

- RUHS Pharmacy Admission Test

- Top Pharmacy Colleges in India

- Pharmacy Colleges in Pune

- Pharmacy Colleges in Mumbai

- Colleges Accepting GPAT Score

- Pharmacy Colleges in Lucknow

- List of Pharmacy Colleges in Nagpur

- GPAT Result

- GPAT 2024 Admit Card

- GPAT Question Papers

- NCHMCT JEE 2024

- Mah BHMCT CET

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Delhi

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Hyderabad

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Mumbai

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Tamil Nadu

- Top Hotel Management Colleges in Maharashtra

- B.Sc Hotel Management

- Hotel Management

- Diploma in Hotel Management and Catering Technology

Diploma Colleges

- Top Diploma Colleges in Maharashtra

- UPSC IAS 2024

- SSC CGL 2024

- IBPS RRB 2024

- Previous Year Sample Papers

- Free Competition E-books

- Sarkari Result

- QnA- Get your doubts answered

- UPSC Previous Year Sample Papers

- CTET Previous Year Sample Papers

- SBI Clerk Previous Year Sample Papers

- NDA Previous Year Sample Papers

Upcoming Events

- NDA Application Form 2024

- UPSC IAS Application Form 2024

- CDS Application Form 2024

- CTET Admit card 2024

- HP TET Result 2023

- SSC GD Constable Admit Card 2024

- UPTET Notification 2024

- SBI Clerk Result 2024

Other Exams

- SSC CHSL 2024

- UP PCS 2024

- UGC NET 2024

- RRB NTPC 2024

- IBPS PO 2024

- IBPS Clerk 2024

- IBPS SO 2024

- Top University in USA

- Top University in Canada

- Top University in Ireland

- Top Universities in UK

- Top Universities in Australia

- Best MBA Colleges in Abroad

- Business Management Studies Colleges

Top Countries

- Study in USA

- Study in UK

- Study in Canada

- Study in Australia

- Study in Ireland

- Study in Germany

- Study in China

- Study in Europe

Student Visas

- Student Visa Canada

- Student Visa UK

- Student Visa USA

- Student Visa Australia

- Student Visa Germany

- Student Visa New Zealand

- Student Visa Ireland

- CUET PG 2024

- IGNOU B.Ed Admission 2024

- DU Admission 2024

- UP B.Ed JEE 2024

- LPU NEST 2024

- IIT JAM 2024

- IGNOU Online Admission 2024

- Universities in India

- Top Universities in India 2024

- Top Colleges in India

- Top Universities in Uttar Pradesh 2024

- Top Universities in Bihar

- Top Universities in Madhya Pradesh 2024

- Top Universities in Tamil Nadu 2024

- Central Universities in India

- CUET Exam City Intimation Slip 2024

- IGNOU Date Sheet

- CUET Mock Test 2024

- CUET Admit card 2024

- CUET PG Syllabus 2024

- CUET Participating Universities 2024

- CUET Previous Year Question Paper

- CUET Syllabus 2024 for Science Students

- E-Books and Sample Papers

- CUET Exam Pattern 2024

- CUET Exam Date 2024

- CUET Syllabus 2024

- IGNOU Exam Form 2024

- IGNOU Result

- CUET City Intimation Slip 2024 Live

Engineering Preparation

- Knockout JEE Main 2024

- Test Series JEE Main 2024

- JEE Main 2024 Rank Booster

Medical Preparation

- Knockout NEET 2024

- Test Series NEET 2024

- Rank Booster NEET 2024

Online Courses

- JEE Main One Month Course

- NEET One Month Course

- IBSAT Free Mock Tests

- IIT JEE Foundation Course

- Knockout BITSAT 2024

- Career Guidance Tool

Top Streams

- IT & Software Certification Courses

- Engineering and Architecture Certification Courses

- Programming And Development Certification Courses

- Business and Management Certification Courses

- Marketing Certification Courses

- Health and Fitness Certification Courses

- Design Certification Courses

Specializations

- Digital Marketing Certification Courses

- Cyber Security Certification Courses

- Artificial Intelligence Certification Courses

- Business Analytics Certification Courses

- Data Science Certification Courses

- Cloud Computing Certification Courses

- Machine Learning Certification Courses

- View All Certification Courses

- UG Degree Courses

- PG Degree Courses

- Short Term Courses

- Free Courses

- Online Degrees and Diplomas

- Compare Courses

Top Providers

- Coursera Courses

- Udemy Courses

- Edx Courses

- Swayam Courses

- upGrad Courses

- Simplilearn Courses

- Great Learning Courses

Earthquake Essay

Essay on Earthquake - An earthquake is a natural disaster that occurs when two tectonic plates collide. The force of the collision creates seismic waves that travel through the earth's crust, causing the ground to shake and buildings to collapse. Here are some sample essays on earthquakes.

- 100 Words Essay on Earthquake

Earthquakes can happen anywhere in the world, and although their occurrence is not predictable, there are some things you can do to make yourself more prepared in case one does strike. This includes having an earthquake kit ready to go, knowing how to drop, cover and hold on, and staying informed about any potential risks in your area. Make sure you have an emergency kit stocked with food, water, and other supplies, and know what to do when an earthquake hits. If you're not sure what to do, it's best to stay away from windows and other objects that could fall on you, and head to a safe place.

200 Words Essay on Earthquake

500 words essay on earthquake.

Earthquakes are a natural disaster that come with a lot of dangers. The shaking and movement of the earth can cause buildings to fall down, trapping people inside. The shaking caused by such a sudden change is usually very minor, but large earthquakes sometimes cause very large shaking of the land. The shaking waves spread from the spot at which rock begins breaking for the first time; this spot is called the center, or hypocenter, of an earthquake.

If you're inside when an earthquake starts, drop to the ground and cover your head. The earthquake's magnitude is related to the amount of earthquake energy released in a seismic event.

Different Types of Earthquakes

There are three types of earthquakes:

Shallow | A shallow earthquake is when the earthquake's focus is close to the surface of the Earth. These earthquakes are usually less powerful than the other two types, but can still cause a lot of damage.

Intermediate | Intermediate earthquakes have a focus that's located between the surface and the Earth's mantle, and are usually more powerful than shallow earthquakes.

Deep | Deep earthquakes have a focus that's located in the mantle, which is the layer of the Earth below the crust. They're the most powerful type of earthquake, and can even cause damage on the surface.

An earthquake can cause damage to buildings and bridges; interrupt gas, electrical, and telephone services; and occasionally trigger landslides, avalanches, flash flooding, wildfires, and massive, destructive waves of water over oceans (tsunamis).

The Dangers Associated With Earthquakes

The shaking of the ground can cause objects to fall off shelves and injure people. If you're outside when an earthquake starts, move away from tall buildings, streetlights and power lines.

An earthquake can also cause a tsunami, or a large wave, to form and crash onto the shore. Tsunamis can be very dangerous and can reach heights of over 100 feet.

How to Prepare for an Earthquake

When an earthquake is imminent, your first step should be to find a safe spot. The most ideal spots are under sturdy furniture or inside door frames. It is best to stay away from windows and anything that can fall over.

Once you've found the safest place, it's time to prepare for the shaking. Grab some blankets, pillows and helmets if possible – all of which can provide extra cushioning against falling objects.

Additionally, you should always keep an eye out for debris that could cause injuries, such as broken glass and sharp objects.

Finally, stay calm until the shaking stops, and monitor local news reports for additional information on how best to handle the situation.

What to do During an Earthquake

The moment an earthquake hits, it is important to stay as calm and collected as possible. Safety is the first priority so you must stay away from windows and furniture that can fall on you, and protect your head with your arms if needed.

If an earthquake occurs while you are indoors, stay away from anything that could fall or break such as windows, mirrors, or furniture. Do not run outdoors as shaking can cause glass and other materials to fall from the building structure. Instead, seek shelter under sturdy tables or desks. If there is no furniture available, move to a corner of the room and crouch down protectively with your arms over your head and neck.

It's also important to take note of any gas lines that could be affected during an earthquake and shut them off if necessary in order to prevent fires from breaking out due to exposed pipes.

After the Earthquake: Recovery and Assistance

When the shaking stops, there will be a period of recovery.

Don't enter any building if it has visible damage due to the earthquake - it's better to be safe than sorry.

You should contact local aid organisations like the Red Cross for additional help with sheltering, water, food and other essentials.

Stay in touch with local officials about any services provided for those affected by the earthquake.

Make sure you also have a plan for what to do if you're stuck in an earthquake, and know how to get in touch with loved ones in case of an emergency.

By being prepared and knowing what to do, you can help ensure that you and your loved ones are safe in the event of an earthquake.

Applications for Admissions are open.

JEE Main Important Physics formulas

As per latest 2024 syllabus. Physics formulas, equations, & laws of class 11 & 12th chapters

Aakash iACST Scholarship Test 2024

Get up to 90% scholarship on NEET, JEE & Foundation courses

JEE Main Important Chemistry formulas

As per latest 2024 syllabus. Chemistry formulas, equations, & laws of class 11 & 12th chapters

PACE IIT & Medical, Financial District, Hyd

Enrol in PACE IIT & Medical, Financial District, Hyd for JEE/NEET preparation

ALLEN JEE Exam Prep

Start your JEE preparation with ALLEN

ALLEN NEET Coaching

Ace your NEET preparation with ALLEN Online Programs

Download Careers360 App's

Regular exam updates, QnA, Predictors, College Applications & E-books now on your Mobile

Certifications

We Appeared in

My earthquake experience

This article was published more than 14 years ago. Some information may no longer be current.

I awaken to the bed swaying, gently at first, and because I'm half asleep and not from here, I think, "Cool, a tremor." I'm just that naive.

Sitting up, I switch on the bedside lamp. It's 3:34 a.m. The floor is shaking harder now, and I try to stand. A surge throws me backward.

Suddenly my 14th-floor Santiago hotel room comes alive, like an angry animal shaking a smaller one in its teeth. It lurches one way and then the other, and the air fills with the building's inhuman noises: rumbles and groans, the screeching of metal. Around me, pictures thud against walls; drawers open and bang shut; window curtains shriek on their rods.

Then the lights go out.

Panic squeezes the breath from me. The cacophony is more unholy in the dark. Trying to cross the rolling floor toward my suitcase at the foot of the bed, I curse myself for having slept naked. I am tossed against the corner of the desk and then to the ground. Lying on my back I yank on pants, then T-shirt and sandals, even as I think, "Just get out!" Something heavy crashes near my head.

I shouldn't even be here now. After three idyllic weeks as instructor at a writers' retreat outside Santiago, my flight home from Chile the previous evening, Feb. 26, had been cancelled because of engine trouble. I'd considered myself lucky to be put up at a luxury hotel.

As I pull myself to standing, sensations and images swarm my mind. I realize I'm whimpering. I don't consciously think that I won't see my husband and sons again. I just sense this, profoundly.

I careen my way to the bathroom and steady myself under the door frame. Isn't this what one is supposed to do? But the building is writhing and this doesn't feel safe.

Hauling open the door of my room, I expect to find people. The lights have burst on and it's blinding in the still-quaking hallway. Incredibly, there's no one about. My mind is screaming, but I don't even call for help.

Follow Facts & Arguments on Twitter

My room is at the end of the corridor. I brace my door open with one leg so it doesn't lock behind me, and push the stairwell door. Beyond it I see chunks of ceiling plaster pelting down, white dust clouding the air and coating the steps. Someone tell me what to do.

I go back into my room. Now the quake is subsiding. Furniture is askew, and the floor is littered with objects. Two large lamps have fallen, one just inches from where I pulled on my clothes. I realize nothing I'm doing makes sense, but grabbing my backpack containing passport and wallet, I run out again.

A middle-aged man is approaching, his face impassive. He says, "We should go down." I say, "Okay," and follow him to the stairs, but I lose sight of him. I take the landings too fast, feeling light-headed, sandals skidding on plaster.

On a lower floor I merge with a river of people in various stages of undress. We wend our way outside to the tennis courts, where a crowd of several hundred are gathering, comforting one another. Some are crying; all are dazed. A woman looks like she is about to faint and I steady her. Seeing frightened children in parents' arms, my selfish thought is thank God my kids aren't here.

Join the Facts & Arguments Facebook group

Soon hotel staff are setting up chairs and passing around bottled water. They offer us tablecloths to wrap around ourselves against the night chill, and slippers for those who are barefoot. They seem remarkably calm. They too must be afraid.

We drift about in tablecloths like ghosts in a school play. A kind man finds me a chair and we talk. My expression feels blank, but my heart is hammering. The staff order us to move away from the building - what do they know? - and 20 minutes after the big quake, we feel the first of many aftershocks. I have to remind myself to breathe.

I wander, and after a while there's a tap on my shoulder and I turn to feel arms wrapping around me. It's Mary, a warm Chilean-Canadian woman I'd met last night. She and her husband, who live in Toronto, would have been on my flight. She kisses my cheek and I kiss her back.

"Thank goodness," she says. "I told Victor, 'We have to find her. She's all alone.' " She rubs my arms.

"Are you okay?" I ask, and she nods. It's all I can do not to cry.

We all feel lucky to be alive, but our relief is tinged with survivor's guilt. Farther south, we soon learn, the 8.8-magnitude earthquake has left many dead and others homeless, and tsunamis may be on the way.

Subscribe to the Facts & Arguments podcast on iTunes

In some hotel rooms ceilings collapsed; TVs and mirrors and glassware shattered; water pipes burst. But at least we have electricity, water, food. Outside the hotel, many do not. Some of us suffer cuts and bruises, but none are seriously injured. Still, dozens refuse to return to their rooms for the next few nights, turning the hotel grounds into a refugee camp. Why I return to mine, I'll never know.

For four anxious days we await news of when and how we'll be transported home. I e-mail my family and friends, and two writers I met at the retreat visit - but here, Mary and Victor, who stay by me, are my lifelines.

A minute and a half. That's how long the quake lasted, they say. But those who experienced it will never forget that eternity of adrenalin-charged panic. And that soul-deep, if fleeting, sense of finality.

Five sleepless nights later, a rescue flight carries us home.

Allyson Latta lives in Toronto.

Report an editorial error

Report a technical issue

Editorial code of conduct

Interact with The Globe

- Website Inauguration Function.

- Vocational Placement Cell Inauguration

- Media Coverage.

- Certificate & Recommendations

- Privacy Policy

- Science Project Metric

- Social Studies 8 Class

- Computer Fundamentals

- Introduction to C++

- Programming Methodology

- Programming in C++

- Data structures

- Boolean Algebra

- Object Oriented Concepts

- Database Management Systems

- Open Source Software

- Operating System

- PHP Tutorials

- Earth Science

- Physical Science

- Sets & Functions

- Coordinate Geometry

- Mathematical Reasoning

- Statics and Probability

- Accountancy

- Business Studies

- Political Science

- English (Sr. Secondary)

Hindi (Sr. Secondary)

- Punjab (Sr. Secondary)

- Accountancy and Auditing

- Air Conditioning and Refrigeration Technology

- Automobile Technology

- Electrical Technology

- Electronics Technology

- Hotel Management and Catering Technology

- IT Application

- Marketing and Salesmanship

- Office Secretaryship

- Stenography

- Hindi Essays

- English Essays

Letter Writing

- Shorthand Dictation

Essay on “I Experience an Earthquake” Complete Essay for Class 10, Class 12 and Graduation and other classes.

I Experience an Earthquake

Outline: Introduction – my strange experience – we rushed out – the havoc caused by the earthquake – man’s control over nature is incomplete.

Who can forget what happened in the small hours of the 30th September 1993? On the previous day I had gone to bed, expecting tomorrow to be like the so many tomorrows that had followed one another in weary succession. But the day, which dawned on 30th September 1993 proved to be different and brought to me a new and horrible experience. I was suddenly awakened at about 4 a.m. by a strange experience which I did not understand at first. I was aware that its main ingredients were a peculiar movement and a peculiar sound. I was rocked for a few seconds. as though I was in a cradle. I heard strange sounds in which I could identify the tinkling of pots, the rattling of windows, and certain muffled rumbling noise issuing from the earth. After a few moments I realized, to my horror, that it was the earthquake.

Others too in my house and locality must have realized it at the same time or a little earlier, as we all sprang up from our beds in a trice and rushed out of our houses, carrying sleeping babes and flabbergasted children. The tremor of the earth had ceased; yet we stood in the open for an hour, dreading another tremor. There was nip in the air that early morning, and the electric lights had gone off. People stood in darkness, talking about the earthquake and praying to God that it might not be repeated.

The tremors of the earth caused no damage in Mumbai. For several hours next morning we thought, with gratitude to Nature, that it had been, on the whole, harmless. But at about noon, news came that the earthquake had played havoc in Latur. All the houses in parts of Latur had been razed to the ground and hundreds of human lives lost.

The destruction wrought by the earthquake at Latur proved the helplessness of man in the face of an unexpected natural calamity. It shows how incomplete is man’s vaunted control over the forces of Nature. He has much to achieve yet in this respect. Is it not a pity that he is frittering away his resources and energies in petty animosities, squabbles and wars?

Difficult Words:Small hours -early hours. ingredients -elements. muffled -subdued, low. flabbergasted – bewildered, amazed. tremor – trembling. razed -destroyed, leveled to the ground. wrought – worked, caused. vaunted – boasted. frittering – wasting.

About evirtualguru_ajaygour

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Quick Links

Popular Tags

Visitors question & answer.

- Bhavika on Essay on “A Model Village” Complete Essay for Class 10, Class 12 and Graduation and other classes.

- slide on 10 Comprehension Passages Practice examples with Question and Answers for Class 9, 10, 12 and Bachelors Classes

- अभिषेक राय on Hindi Essay on “Yadi mein Shikshak Hota” , ”यदि मैं शिक्षक होता” Complete Hindi Essay for Class 10, Class 12 and Graduation and other classes.

- Gangadhar Singh on Essay on “A Journey in a Crowded Train” Complete Essay for Class 10, Class 12 and Graduation and other classes.

Download Our Educational Android Apps

Latest Desk

- Television – Shiksha aur Manoranjan ke Sadhan ke roop mein “टेलीविजन – शिक्षा और मनोरंजन के साधन के रूप में” Hindi Essay 600 Words for Class 10, 12.

- Vigyan evm Nishastrikaran “विज्ञान एवं नीतिशास्त्र” Hindi Essay 1000 Words for Class 10, 12 and Higher Classes Students.

- Vigyan Ek Accha Sewak Ya Krur Swami “विज्ञान एक अच्छा सेवक या क्रूर स्वामी” Hindi Essay 1000 Words.

- Dainik Jeevan mein Vigyan “दैनिक जीवन में विज्ञान” Hindi Essay 800 Words for Class 10, 12 and Higher Classes Students.

- Example Letter regarding election victory.

- Example Letter regarding the award of a Ph.D.

- Example Letter regarding the birth of a child.

- Example Letter regarding going abroad.

- Letter regarding the publishing of a Novel.

Vocational Edu.

- English Shorthand Dictation “East and Dwellings” 80 and 100 wpm Legal Matters Dictation 500 Words with Outlines.

- English Shorthand Dictation “Haryana General Sales Tax Act” 80 and 100 wpm Legal Matters Dictation 500 Words with Outlines meaning.

- English Shorthand Dictation “Deal with Export of Goods” 80 and 100 wpm Legal Matters Dictation 500 Words with Outlines meaning.

- English Shorthand Dictation “Interpreting a State Law” 80 and 100 wpm Legal Matters Dictation 500 Words with Outlines meaning.

Talk to our experts

1800-120-456-456

- Earthquake Essay

Download the Earthquake Essay Available on Vedantu’s Website.

Earthquakes are some of the most devastating natural disasters. Millions of dollars worth of property are damaged and a hundred die every time a big magnitude of eater quake strikes. It is in this regard that everyone must read and know about earthquakes and be prepared to mitigate the damage. Furthermore, the topic of earthquakes is quite often asked in exams. Preparing for this topic will enable them to have an edge and score more marks in the English paper.

To serve the above-mentioned purpose, Vedantu has come up with the Earthquake essay. This essay is prepared by the experts who know what exactly is required to know and weeding out points that are not important. The essay is very precise and would surely allow students to successfully claim marks in the essay question and even stay prepared when an earthquake actually strikes.

What is an Earthquake?

When the earth’s surface shakes, the phenomenon is referred to as an earthquake. Precisely, the sudden trembling of the earth’s surface is the cause of an earthquake. Earthquakes are regarded as one of the deadliest natural disasters. Huge damage and loss of property are caused by earthquakes. There are various types of earthquakes. Some of them are severe in nature. The most dangerous thing about an earthquake is that it is quite unpredictable. It can cause several damages without any previous indication. The intensity of an earthquake is measured by the Richter’s scale. Generally, earthquakes occur due to the movement of tectonic plates under the earth’s surface.

Types of Earthquake

There are four kinds of earthquakes namely

Tectonic Earthquake,

Volcanic Earthquake,

Collapse Earthquake and

Explosive Earthquake.

Tectonic Earthquake

It is caused due to the movement of the slab of rocks of uneven shapes that lie underneath the earth’s crust. Apart from that, energy is stored in the earth’s crust. Tectonic plates are pushed away from each other or towards each other due to the energy. A pressure is formed because of the energy and movement as time passes. A fault line is formed due to severe pressure. The center point of this dispersion is the epicenter of the earthquake. Subsequently, traveling of the waves of energy from focus to the surface causes the tremor.

Volcanic Earthquake

The earthquake caused by volcanic activity is called a volcanic earthquake. These kinds of earthquakes are of weaker magnitudes. Volcanic earthquakes are categorized into two types. In the first type, which is called volcano-tectonic, shaking happens due to input or withdrawal of Magma. In the second type, which is termed as Long-period earthquake, tremors occur due to changing of pressure among the earth’s layers.

Collapse Earthquake

Collapse Earthquake is the third type of earthquake that occurs in the caverns and mines. This is another example of a weak magnitude earthquake. Mines collapsed due to underground blasts. Consequently, seismic waves are formed due to this collapsing. Earthquakes occur because of these seismic waves.

Explosive Earthquake

The fourth type of earthquake is called an explosive earthquake. This is caused due to the testing of nuclear weapons.

Effects of Earthquake

The effects of earthquakes are very severe and deadly.

It can cause irreparable damage to property and loss of human lives. The lethality of an earthquake depends on its distance from the epicentre.

Damage to establishments is the direct impact of an earthquake. In the hilly areas, several landslides are caused due to earthquakes.

Another major impact of an earthquake is soil liquefaction. Losing the strength of water-saturated granular material is the cause behind this. The rigidity of soil is totally lost due to this.

Since the earthquake affects the electric power and gas lines, it can cause a fire to break out.

Deadly Tsunamis are caused due to earthquakes. Gigantic sea waves are caused by the sudden or abnormal movement of huge volumes of water. This is called an earthquake in the ocean. When tsunamis hit the sea coasts, they cause a massive loss of lives and properties.

Earthquake is termed as one of the most huge and lethal natural disasters in the world. It proves the fact that human beings are just nothing in front of nature. The sudden occurrence of earthquakes shocks everyone. Scientists are working rigorously to prevent the damage of earthquakes, but nothing fruitful has been achieved yet.

Examples of Devastating Earthquake

The city of Kobe in Japan witnessed a devastating earthquake on January 17, 1995, killing more than 6,000 and making more than 45,000 people homeless. The magnitude of the quake was 6.9 at the moment which caused damage of around 100 million dollars. The governor of Kobe spent years on reconstruction and made efforts to bring back fifty thousand people who had left home. Japan geologically is a highly active country. It lies upon four major tectonic plates namely, Eurasian, Philippine, Pacific, and North American which frequently meet and interact.

The second incident is in Nepal where an earthquake struck on April 25, 2015. About 9000 people were killed and almost 600,000 structures were destroyed. The magnitude of the quake was 7.9 and the repels were felt by neighbouring countries like Bangladesh, China and India. The disaster caused severe damage of millions of dollars. All the countries across the world including India garnered to help Nepal by sending monetary aid, medical supplies, transport helicopters and others.

FAQs on Earthquake Essay

1. How to download the Earthquake Essay?

The Earthquake essay is available on Vedantu's website in PDF format. The PDF could be downloaded on any device, be it android, apple or windows. One just has to log on to www.vedantu.com and download the document. The document is totally free of cost and a student does not need to pay any prior registration fee.

2. How to protect oneself during an earthquake?

Earthquakes could be very disastrous and can cause a lot of collateral damage. During an earthquake you can look for the corners to hide. Another safe place to hide is under the table or under the bed. If one is sitting in a multistory building, avoid taking a lift and only use the stairs. In this kind of situation, one should never panic and stay calm. Let the earthquake pass until then keep hiding in the safe spot. Once over, come out to evaluate the situation and take appropriate actions.

3. How to mitigate the effects of an earthquake?

Prevention is better than cure. It is always a better idea to take necessary actions before an earthquake has struck. In the first place, send a copy of all your documents to someone reliable. In case of an earthquake that destroys your important documents, there would always remain a facility to retrieve them. Research and know if your city is in a seismic zone. One should also take note of earthquakes during the construction of a house and lay emphasis on a seismic-proof house.

4. How can one teach people about the effects of an earthquake?

There are many ways one can raise awareness about the effects of earthquakes. There is Youtube and Instagram which could be used to disseminate all the knowledge about the earthquake and its impact on humans. You can also go to schools and colleges to conduct a seminar whereby the students could be told about the mitigation and steps to take when an earthquake strikes. However before that, one must thoroughly research the topic. For this, visit www.vedntu.com and download the earthquake essay for free.

5. Who has written the Earthquake essay?

The earthquake essay provided by Vedantu is prepared by expert teachers who invest a good amount of time and effort to come up with an essay that is highly useful for the students in their personal lives as well as for their academic performance. The students can use this essay to maximize their abilities to cope with the questions on earthquakes and the earthquake itself. The essay is totally reliable and one mustn’t doubt its credibility at all.

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, the effects of earthquake experience on intentions to respond to earthquake early warnings.

- 1 Joint Centre for Disaster Research, Massey University, Wellington, New Zealand

- 2 United States Geological Survey, Menlo Park, CA, United States

- 3 Faculty of Psychology, Doshisha University, Kyotanabe-shi, Japan

- 4 GNS Science, Lower Hutt, New Zealand

- 5 Daniel J. Evans School of Public Policy and Governance, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, United States

Warning systems are essential for providing people with information so they can take protective action in response to perils. Systems need to be human-centered, which requires an understanding of the context within which humans operate. Therefore, our research sought to understand the human context for Earthquake Early Warning (EEW) in Aotearoa New Zealand, a location where no comprehensive EEW system existed in 2019 when we did this study. We undertook a survey of people's previous experiences of earthquakes, their perceptions of the usefulness of a hypothetical EEW system, and their intended responses to a potential warning (for example, Drop, Cover, Hold (DCH), staying still, performing safety actions). Results showed little difference in perceived usefulness of an EEW system between those with and without earthquake experience, except for a weak relationship between perceived usefulness and if a respondent's family or friends had previously experienced injury, damage or loss from an earthquake. Previous earthquake experience was, however, associated with various intended responses to a warning. The more direct, or personally relevant a person's experiences were, the more likely they were to intend to take a useful action on receipt of an EEW. Again, the type of experience which showed the largest difference was having had a family member or friend experience injury, damage or loss. Experience of participation in training, exercises or drills did not seem to prompt the correct intended actions for earthquake warnings; however, given the hypothetical nature of the study, it is possible people did not associate their participation in drills, for example, with a potential action that could be taken on receipt of an EEW. Our analysis of regional differences highlighted that intentions to mentally prepare on receipt of a warning were significantly higher for Canterbury region participants, most likely related to strong shaking and subsequent impacts experienced during the 2010–11 Canterbury Earthquake Sequence. Our research reinforces that previous experience can influence earthquake-related perceptions and behaviors, but in different ways depending on the context. Public communication and interventions for EEW could take into consideration different levels and types of experiences of the audience for greater success in response.

Introduction

Warning systems represent a critical element of the communication landscape and are aimed at providing information so people can take protective responses to various perils. While many warning systems tend to focus on the technical capabilities of providing warning information, warning systems in fact comprise a number of elements, all of which are needed for effective responses to occur. Kelman and Glantz (2014) summarize these aspects as risk knowledge, monitoring and warning, dissemination and communication and response capability. Basher (2006) and Harrison et al. (2020) argue that given effective responses are a key outcome of a warning system, a people-centered approach should be taken to warnings. This is reflected in the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) 1 definition of an early warning system which states it is: “The set of capacities needed to generate and disseminate timely and meaningful warning information to enable individuals, communities and organizations threatened by a hazard to prepare and to act appropriately and in sufficient time to reduce the possibility of harm or loss” ( United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), 2009 , p. 12). Consequently, in developing an effective warning system it is important to understand the environmental, social and experiential context in which humans are located, to be able to identify how they might best receive, interpret, and respond to warnings, and then utilize that in warning system development ( McBride et al., 2022 ).

Warnings can be disseminated and received for a wide range of perils, including natural hazards such as severe weather, flooding, volcanoes, tsunami and landslides. With the progression of science and technology, earthquake early warnings (EEW) are now also delivered to citizens in a number of countries including Japan, Taiwan, Mexico, South Korea, the West Coast of the United States of America (USA), Sichuan China and Peru ( Allen and Melgar, 2019 ; Fallou et al., 2022 ; McBride et al., 2022 ), among others. An EEW comprises advanced notification of earthquake shaking, delivered by a device such as a mobile phone or stand-alone alerting device, or via channels such as the media. The ability to send such a notification is dependent upon detecting an earthquake that has already occurred (e.g., by detecting the earthquake with sensors at its source or via P-waves) and sending out a warning in advance of the arrival of shaking from S-waves ( Given et al., 2018 ).

Most warnings are usually only issued for locations anticipated to receive strong shaking, as this is where damage, injury, and potentially death may occur ( Allen et al., 2018 ; Allen and Melgar, 2019 ; Allen and Stogaitis, 2022 ). Notification may be received anywhere from a few seconds to minutes before shaking ensues; however, most warnings will be in the range of seconds to tens of seconds, rather than minutes ( Minson et al., 2018 ). In some instances, if a person is located very close to the epicenter of an earthquake, there may not be time for a warning and the notification might arrive after shaking has started. In addition, delays to delivery of alerts including technological latencies in alerting channels, like cell broadcast or similar systems, will further delay when an alert can be delivered ( Prasanna et al., 2022 ).

Upon receipt of a warning notification, citizens have the opportunity to take action to protect themselves from the incoming shaking. The actions that people might take vary from country to country. In the United States of America, for example, people are usually advised to protect themselves by performing Drop, Cover and Hold On (DCHO) when shaking occurs ( Jones and Benthien, 2011 ; McBride et al., 2022 ), with additional advice provided on other protective actions for specific circumstances such as when driving ( Washington State Emergency Management Division, 2017 ). Similar advice is promoted in places like Japan and Aotearoa New Zealand, where the message has been simplified to Drop, Cover, Hold (DCH) ( McBride et al., 2019 ; Vinnell et al., 2020 ). This advice is relevant because most buildings in such countries are expected to perform adequately in an earthquake. However, in other countries where construction is not as sound (e.g., Mexico) advice focusses on evacuating buildings on receipt of an EEW ( Santos-Reyes, 2020 ; McBride et al., 2022 ). Japan, which has had an official EEW system operating since 2007 ( Fujinawa and Noda, 2013 ), also provides advice on a variety of other safety actions to take on receipt of a warning (e.g., stopping elevators and getting off at the nearest floor; Japan Meteorological Agency, 2019 ).

Influences on People's Ability to Respond to EEWs

People's ability to respond to EEWs may be confounded by a range of factors. In the first instance, timing can be an issue. Where the time between a warning and the commencement of shaking is very short (i.e., a few seconds) citizens might only be able to stop and stay still or DCH ( Nakayachi et al., 2019 ; Becker et al., 2020a ). As warning timeframes increase, the opportunity for taking further safety actions or evacuating a building is possible. However, this opportunity also creates the added possibility of injuries if people are still moving as shaking commences ( Shoaf et al., 1998 ; Johnston et al., 2014 ; Horspool et al., 2020 ). Given EEW timeframes are often so short (e.g., see Becker et al., 2020b for Aotearoa New Zealand modeling), consideration about what actions to take needs to occur well in advance of an earthquake, and is best achieved through education programmes and practice of drills ( Vinnell et al., 2020 ). Arguably, EEW struggles to meet the definition from the United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) (2009 ), with “sufficient time to reduce the possibility of harm or loss” being at issue here, as EEW may not provide this given its technological and physical limitations. Even with faster alerting channels and improved technology, there may always be some physical limitations to the system, such as a late alert zone, where the earthquake's epicenter is too close to an area for it to be categorized and calculated by algorithms, let alone sent out via various alerting channels before shaking arrives ( Minson et al., 2019 ; McBride et al., 2020 ).

Second, citizens' desire and ability to act upon an EEW is influenced by a range of cognitive, social, and affective factors. Some of these aspects can directly influence people's responses to warnings, while others have a more indirect influence on the process. People's previous experiences of earthquakes are a part of this mix. Experience can be described in many different ways, an issue that has been highlighted and which makes it difficult to draw comparisons between studies ( Becker et al., 2017 ). For this paper, we use the terms direct, indirect, vicarious, and life experience as defined by Becker et al. (2017) . In terms of earthquakes, direct experience includes physically feeling strong shaking, or being impacted through injury or loss. Even direct earthquake experiences are highly variable, by frequency, intensity and context. Indirect experience includes being exposed indirectly to an event (e.g., having travel or employment disrupted) or observing a local event. Vicarious experience includes occasions where one might interact with friends and family with regard to a disaster, or observe a disaster in the media, rather than a disaster having a direct or indirect impact upon themselves. Vicarious experience can also extend to educational efforts including drills and exercises, which develop procedural knowledge as to what protective actions to take ( Johnson et al., 2014 ; McBride et al., 2019 ), or when people are exposed to disaster scenarios but do not live through those disasters directly. Life experience is a fourth type of relevant experience where people might refer back to other adverse events or situations in their lives (e.g., experiencing a health issue, a car or work accident, power outages, crime, war) in understanding how they might respond to an earthquake ( Norris, 1997 ; Paton et al., 2000 ; Becker et al., 2017 ).

The Influence of Previous Experience on Responses to Earthquake Threats

Previous research highlights the diverse ways in which experience can affect people's responses to earthquakes. Given the relatively recent emergence of technology that has made EEW more accessible for use, most research has been completed in an earthquake preparedness context, as opposed to a warnings context. Some researchers have found that earthquake experience can be a driver of preparedness activity (e.g., Kiecolt and Nigg, 1982 ; Lehman and Taylor, 1987 ; Mileti and Fitzpatrick, 1992 ; Mileti and Darlington, 1997 ; Lindell and Perry, 2000 ; Tanaka, 2005 ; Dunn et al., 2016 ; Becker et al., 2017 ; Vinnell et al., 2017 ; Doyle et al., 2018 ), while others have found the opposite (e.g., Mulilis et al., 1990 ; Farley, 1998 ; Lindell and Prater, 2002 ; Basolo et al., 2009 ; Bourque et al., 2012 ; Lindell, 2013 ; Shapira et al., 2018 ).

The nature of people's experience appears to be key to whether previous experience will enhance preparedness or not. Experiences such as being directly impacted by an earthquake (e.g., experiencing damage, loss or injury; Jackson, 1981 ; Turner et al., 1986 ; Blanchard-Boehm, 1998 ; Lindell and Prater, 2000 ; Nguyen et al., 2006 ); being indirectly impacted (e.g., evacuating following an earthquake, participating in rescues; Becker et al., 2017 ; Doyle et al., 2018 ), or being vicariously affected in a more personal way (e.g., experience of loss by a family member; Turner et al., 1986 ) have been identified as influential in motivating people to prepare for future earthquakes. However, as Lindell (2013) highlights, even these types of experiences have their own unique nuances which influence decisions about whether to prepare or not, and how to prepare.

Additionally, researchers have found various mediating factors that influence the experience-preparedness process. These include such aspects as risk perception ( Solberg et al., 2010 ; Bourque et al., 2012 ; Bourque, 2013 ; McClure et al., 2015 ; Dunn et al., 2016 ), biases stemming from certain perceptions such as optimism and normalization biases ( Weinstein, 1989a ; Mileti and O'Brien, 1992 ; Helweg-Larsen, 1999 ; Spittal et al., 2005 ; Shapira et al., 2018 ), levels of concern, fear or anxiety ( Dooley et al., 1992 ; Rüstemli and Karanci, 1999 ; Karanci and Aksit, 2000 ; Siegel et al., 2003 ; Heller et al., 2005 ; Dunn et al., 2016 ; Paton and Buergelt, 2019 ) and people's ability for personal control ( Rüstemli and Karanci, 1999 ). Research in Aotearoa New Zealand particularly has shown that potential barriers to preparation behavior such as cost or logistics are less influential than cognitive barriers ( McClure et al., 2015 ; Vinnell et al., 2021 ).

Many of the factors and biases outlined above are evolved protective mechanisms to help individuals cope in response to an overwhelming number of risks that we encounter in our daily lives. Such risks can range from the lower likelihood high impact events such as an earthquake through to higher likelihood less widely impacting events such as car accidents. Biases work to reduce feelings of fear about risks; for example, optimism biases involve an individual believing they are less likely to suffer negative consequences than other people like them ( Weinstein, 1989b ), despite this being probabilistically flawed. Normalization bias involves the individual believing that all future events (e.g., earthquakes) will be similar to all past events that they have experienced ( Mileti and O'Brien, 1992 ; Mileti and DeRouen Darlington, 1995 ; Johnston et al., 1999 ). Therefore, if a person feels a previous earthquake was not bad in terms of shaking or impacts, they might consider future earthquake risk to be low and optimistically not bother preparing, or not intend responding to an EEW. These psychological mechanisms are useful as they allow individuals to function in the face of a multitude of risks but pose a challenge which must be overcome when trying to motivate preparedness. Our understanding of how these factors operate is therefore important to unpacking how experience might influence preparedness, and potentially future responses to EEW.

Several theories have been developed to explain and predict people's behavior in hazard contexts, including in response to warnings, including the Protective Action Decision Model (PADM) ( Lindell and Perry, 2012 ); Protection Motivation Theory (PMT) ( Tanner et al., 1989 ), and Community Engagement Theory (CET) ( Paton, 2013 ). Theories from other areas of behavioral sciences have also been applied in the hazard context, including Emergent Norm Theory (ENT) ( Wood et al., 2017 ) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) ( Vinnell et al., 2021 ). These models propose a large number of factors which can influence both people's preparation behavior and response behavior, including environmental and social cues; information about the peril/warning itself; exposure to that information; perceptions about the threat, actions, and what others think; and factors related to the current situation. Such inputs will determine an eventual response such as undertaking protective action, conducting an information search, or an emotional response. Sometimes people will also reach a conclusion that they will do nothing.

While much research has focussed on warnings in the context of other perils (e.g., tornadoes, hurricanes, volcanoes), there has been very limited work on responses to earthquake early warning, likely due to the relatively recent nature of emerging technologies to support widespread warning responses across different countries. Studies that have been conducted have focussed on perceptions of EEW and either intended or actual responses to earthquake warnings. The following outlines these studies.

Prior Studies on EEW Perceptions, Experiences and Responses

First, it has been important to understand how useful people perceive EEWs to be. We know from the PADM model and from other studies, that perceptions about preparedness (in this case a warning system) and protective actions are influential in people's decision-making about whether to undertake actions or not ( Lindell and Perry, 2012 ; Johnston et al., 2013 ; Becker et al., 2015 ; Vinnell et al., 2017 ). If an EEW system is perceived as useful, and the warnings actionable, then citizens may be more likely to use it. Results from research on the perceptions of EEW usefulness have been mixed, however, depending on the context. For hypothetical EEW scenarios, citizens have expressed strong support for EEW utility ( Dunn et al., 2016 ; Becker et al., 2020a , b ). In real warning situations, some researchers have found that people do consider warnings useful, even when issues arise with warning systems, such as receiving false alerts or late alerts after shaking has occurred ( Nakayachi et al., 2019 ; Fallou et al., 2022 ). However, other research by Santos-Reyes (2020) has found that perceptions of warning systems' usefulness can fall following a devastating earthquake (i.e., a Magnitude 7.1 earthquake in Mexico on 10 Sept 2017 when warnings were not provided in enough time before shaking for people to act). Given the 2017 earthquake in Mexico caused damage, injury and deaths, it was perhaps the severe impacts from this experience that influenced people's subsequent perceptions about EEW's utility, and possibly also recalibrated people's understanding of its true effectiveness.

Second, research on citizens' actual and intended responses to alerts have also had mixed conclusions. Studies from Japan suggest citizens are more likely to mentally prepare and stop and stay still on receipt of a warning, rather than take a specific protective action ( Nakayachi et al., 2019 ). Reasons for the Japanese population not taking specific protective actions on receipt of an alert appear to relate to previous experience, where prior warnings have not resulted in strong shaking, leading to lower risk perception and optimism that strong shaking will not follow warnings in future. Data from a Peru survey highlight a similar lack of protective action, whereby participants reported that on receipt of an alert, they more often warned people nearby or waited for shaking to begin ( Fallou et al., 2022 ). These studies show that having previous experience of EEWs does not necessarily translate into people taking protective action for alerts, for various reasons. However, when surveying intended responses of citizens from other countries without operational EEW systems (e.g., United States of America prior to EEW roll-out on the West Coast, and Aotearoa New Zealand), people were more likely to intend to take protective actions such as DCH ( Dunn et al., 2016 ; Becker et al., 2020a ), in comparison with Japan and Peru. Whether these intentions are accurate or not is questionable ( Becker et al., 2020a ). As an example, Dunn et al. (2016) found in their survey that 53% suggested they would DCHO, while only 20% had actually done so for an earthquake. Only future research will help us understand whether intentions predict actions in an EEW context.

Additionally, from an experience perspective, Dunn et al. (2016) looked at citizens' prior experiences of earthquakes and perceptions of EEW in a “willingness to pay” for warnings context (i.e., willingness to pay for an earthquake early alert app.). In their survey, respondents with previous earthquake experience had a higher familiarity with the concept of EEW, and were slightly more likely to consider EEW effective, in that they believed they could better protect themselves from earthquake risks. However, respondents with experience of an actual earthquake also had less willingness to pay for an EEW app., possibly due to the fact that most of their previous experiences only related to moderate shaking levels which were of limited concern. People who had vicarious experience of watching the “San Andreas” movie expressed more willingness to pay. The Dunn et al. (2016) survey highlighted some of the influences of previous earthquake experience on EEW, namely people's perception that EEW could provide them with a better outcome (i.e., positive outcome expectancy), and that different types of experience can be influential on the process (i.e., in this case, direct vs. vicarious experience), but in different ways.

The influence of previous experience is difficult to understand in the context of earthquake preparedness, let alone in a warning context. Given limited behavioral research on EEW, the effects of experience on earthquake warning response behavior is untested. Therefore, we undertook research to attempt to advance our understanding on this topic. Particularly, we were interested in understanding whether previous earthquake experience might influence both people's perceptions of EEW and their responses upon receiving an alert.

To do this we undertook a survey in 2019 in Aotearoa New Zealand. Given Aotearoa New Zealand had no comprehensive EEW system in 2019 ( Prasanna et al., 2022 ), the survey focussed on a hypothetical EEW context. Within the survey, we asked a range of questions about preferred EEW system attributes and anticipated responses to EEW, of which the general findings are reported in Becker et al. (2020a) . We also asked about people's experiences of previous earthquakes from a direct, indirect and vicarious experience perspective. We were interested in finding out what effect such experiences had on perceived usefulness of EEW and intended responses to warnings. This paper discusses key findings from the survey in relation to earthquake experience and EEW.

Materials and Methods

Our survey contained 20 questions, most of which were quantitative single response, multiple response and Likert or Likert-type scale questions ( Joshi et al., 2015 ) (18 questions), with the others being qualitative free response questions (2 questions). The survey covered aspects of previous earthquake experience, anticipated responses to a hypothetical EEW scenario, perceived usefulness of EEWs, preferred attributes of an EEW system, earthquake preparedness [including participation in workplace or volunteer training, emergency management exercises in general, and targeted drills such as the ShakeOut earthquake drill ( Jones and Benthien, 2011 )] and demographics. Aside from the provision of the hypothetical scenario, no additional information was given about EEWs, and people's responses to the questions were unprompted. More information about the survey is available in Becker et al. (2020a) . Only the questions relevant to the analyses reported in this paper are presented here. Under Massey University human ethics procedures, the survey was deemed low risk, and received an Ethics Notification Number of 4000019302.

The survey was uploaded online into the SurveyMonkey software programme ( SurveyMonkey, 1999–2022 ) and was promoted to Aotearoa New Zealand citizens via a press release that resulted in press articles in the online newspaper “Stuff” and a radio interview with Newstalk ZB. Additionally the survey was promoted on social media though Facebook and Twitter via the following sources: GeoNet, QuakeCoRE, Resilience to Nature's Challenges National Science Challenge, East Coast Life at the Boundary, Alpine Fault 8, and the Joint Center for Disaster Research. We opened the survey for participation on 22 March 2019 and closed it on 30 April 2019. During this time period no significant earthquake events occurred. A total of 3,084 self-selected responses were received from citizens across Aotearoa New Zealand as per a convenience sample. Participants were of average age distribution (when compared to New Zealand census data ( StatsNZ, 2018 ; sample range 18–80+, 47% between 30 and 49 years old), but more likely than average to be female (65%) and consider themselves of New Zealand (40%)/New Zealand European (46%) ethnicity. Males (33%) and other ethnicities such as Māori (4%) were under-represented in the data. Nearly 60% of participants reported that they already knew what Earthquake Early Warning was, prior to undertaking the survey. Further details about the survey method are presented in Becker et al. (2020a) , along with frequency results and the Supplementary Data set for the full survey.

Previous Earthquake Experience

Participants were asked to indicate which, if any, previous experiences they had with earthquakes out of the following options:

1. I have personally felt an earthquake before.

2. I have felt strong shaking (i.e., MM6—where people and animals are alarmed, and many run outside. Walking steadily is difficult. Furniture and appliances may move on smooth surfaces, and objects fall from walls and shelves. Glassware and crockery break. Slight non-structural damage to buildings may occur).

3. I have experienced personal injury, damage or loss from an earthquake.

4. I have had family or friends injured, or experience damage or loss from an earthquake.

5. I have observed local earthquake damage or loss (e.g., in my neighborhood or city).

6. I have observed earthquake damage or loss via the media (e.g., television, internet).

Participants reported how likely they would be to take particular actions after receiving a warning for a hypothetical scenario. The scenario was developed to be as similar as possible to real alerts experienced in Japan following the Gunma and Chiba earthquakes in 2018 (see Nakayachi et al., 2019 ). The hypothetical scenario involved participants' receipt of a mobile phone alert at 8.30 pm on a Saturday evening which said, “Earthquake Early Warning. Strong shaking expected soon”. Participants indicated whether, on receipt of this alert, they would on a 5-point scale be “Extremely unlikely” to “Extremely likely” to:

1. Do nothing/undertake no actions.

2. Look for further earthquake information about the warning (e.g., check GeoNet, TV, radio or mobile phone or talk to other people).

3. Tell other people the earthquake is coming.

4. Stop, and stay still, awaiting the shaking on the spot.

5. Mentally prepare myself for the shaking.

6. Take specific behaviors to protect myself on the spot (e.g., Drop, Cover, Hold; hold on to something; protect head; take cover under the table etc.).

7. Move nearby to where I think it is safe.

8. Go outside.

9. Undertake safety actions (e.g., secure furniture, secure a potentially dangerous piece of equipment, turn something off (e.g., gas fire), open the door to secure the way out, put on clothes or shoes).

10. Help others, or act to protect others (e.g., children, other family, friends, workmates).

11. Slow down, pull over and stop car.

Perceptions of Usefulness

Participants responded to the question “How useful do you think an EEW would be for you?” with a 4-point scale from “Useless” to “Useful”.

Previous Earthquake-Related Behavior

Participants indicated which behaviors they had undertaken to prepare for an earthquake. Of interest in this paper were the following two behaviors:

1. I have participated in training or exercises, so I can better respond to emergencies.

2. I have practiced responding to an earthquake drill (e.g., Drop, Cover, Hold as part of ShakeOut or self-organized drills).

Research Questions

To understand how previous earthquake experience might influence responses to EEW we developed three primary research questions and undertook statistical tests on the specific questions from the survey described above. We describe each below.

Research Question 1: Do EEW Perceptions and Intentions Differ Between Those With and Without Prior Earthquake Experience?

RQ1a: We tested whether perceptions of the usefulness of EEW differed between those with and without prior earthquake experience using a series of six independent samples t -tests. In all tests the dependent variable was perceived usefulness of EEW. Participants were split into groups depending on whether they indicated they had or did not have a particular type of earthquake experience.

RQ1b: Similarly, we tested whether the actions participants intended to take differed between those with and without prior experience using independent samples t -tests. Mean intentions to undertake a particular action (dependent variable) were compared between those participants with and without each specific type of experience (grouping variable).

Research Question 2: Is Preparedness, Particularly Participation in Training, Exercises or Drills, Related to People's Intended Actions for an EEW?

RQ2a: We tested whether mean intentions to undertake each action in response to an EEW (dependent variable) differed between those who had participated in training or practiced emergency management exercises and those who had not (grouping variable) using a series of independent samples t -tests.

RQ2b: Similar to RQ2b, we tested whether mean intentions to undertake each action differed between those who had practiced earthquake drills and those who had not using a series of independent samples t -tests.

Research Question 3: Do Intentions to Undertake Particular Actions in Response to an EEW Differ Between Regions of Aotearoa New Zealand Which Have Experienced More Earthquakes?

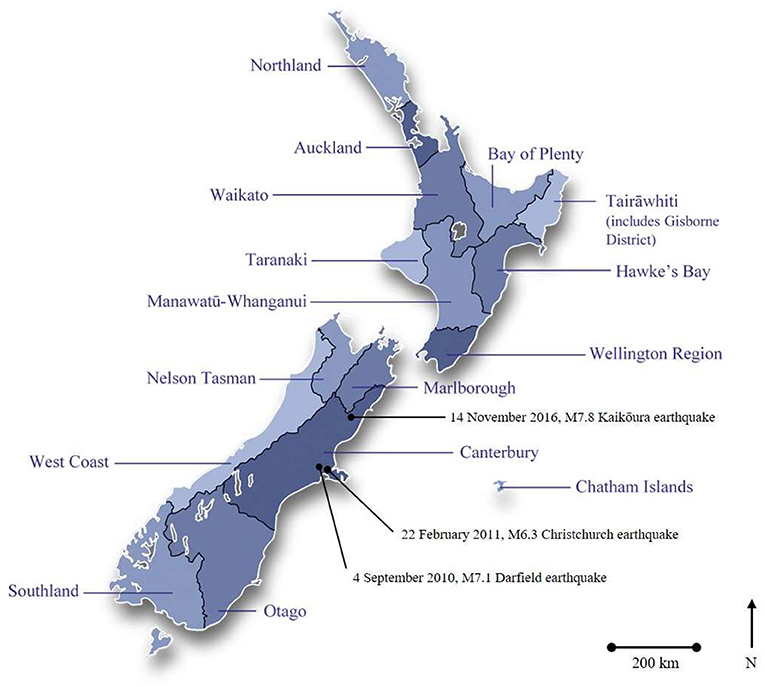

For the purposes of locational analysis, we grouped responses from certain regional areas together into Auckland ( n = 223), Canterbury ( n = 729), Hawke's Bay/Gisborne (Tairāwhiti) combined ( n = 147); Wellington ( n = 799); and Otago/Southland combined ( n = 157). Location in this way acts as a proxy for earthquake experience, as only two regions had experienced strong shaking from earthquakes in the previous 10 years; notably, the Canterbury earthquakes in 2010–11 that affected wider Canterbury and the 2016 Kaikoura earthquake for which the Canterbury and Wellington regions experienced strong shaking ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1 . Map of Aotearoa New Zealand showing regional areas as defined by Civil Defence Emergency Management boundaries ( National Emergency Management Agency, 2013 ), the locations of the Darfield and Christchurch earthquakes (from the 2010–11 Canterbury Earthquake Sequence) and the location of the 2016 Kaikoura earthquake ( GNS Science, 2016 ).

RQ3: Mean intention scores for each particular action were compared between the five locations using a series of one-way Analyses of Variance (ANOVAs).

Limitations

Some types of earthquake experience were quite widely reported; for example, 93% of participants had felt an earthquake before and 87% had observed earthquake damage or loss through the media. However, the large sample size of this study means that even in these instances there were at least 200 participants without this experience, making group comparisons relatively robust. A further limitation of this study is the use of hypothetical situations and the measurement of intentions rather than behavior. While intentions do not perfectly predict actual behavior, they are seen as one of the best factors to approximate behavior when behavior cannot be measured ( Armitage et al., 2013 ). Additionally people's ability to assess the usefulness of a system might vary in the context of having no system, vs. their experiences with an actual operating system. Given the unpredictability of earthquakes, and the fact that this research was part of a project to scope the viability and enthusiasm for an EEW system in Aotearoa New Zealand, assessing actual responses was not feasible. Finally, this study examined direct associations between specific types of earthquake experience and intentions to respond to an EEW rather than considering the interactive nature of disaster experience ( Becker et al., 2017 ).

RQ1a: Does Prior Experience of Earthquakes Influence Perceptions of Usefulness of EEW?

Those who have had family or friends injured, or experienced damage or loss from an earthquake, saw EEW as significantly more useful (Mean [ M ] = 1.25, Standard Deviation [ SD ] = 0.53) than those who have not ( M = 1.29, SD = 0.57), independent samples t- test result: t (2451.45) = 1.99, significance level p < 0.05, Cohen's effect size d = 0.08. This is a weak effect (indicated by the relatively small d value), and all other tests for difference in means in perceived usefulness between groups with different types of experience and those without were non-significant ( p- values from 0.36 to 0.92). Overall, these findings suggest that prior earthquake experience does not influence perceptions of the usefulness of EEW.

RQ1b: Does Prior Experience of Earthquakes Influence Intended Actions?

Those who have personally felt an earthquake before had marginally weaker intentions to do nothing ( M = 2.10, SD = 1.42) than those who had not felt an earthquake ( M = 2.30, SD = 1.53), t (206.34) = 1.72, p = 0.09, d = 0.24. Participants were also less likely to go outside if they had personally felt an earthquake before ( M = 2.67, SD = 1.36) than if they had not ( M = 2.30, SD = 1.34), t (2615) = 2.70, p < 0.01, d = 0.11. Finally, participants were less likely to slow down, pull over, and stop their car if they had felt an earthquake before ( M = 3.92, SD = 1.19) than if they had not ( M = 4.08, SD = 1.07), t (210.36) = 2.00, p < 0.05, d = 0.28. There was no significant difference in intentions for any other actions between those who had and those who had not personally felt an earthquake ( p- values from 0.14 to 0.96).

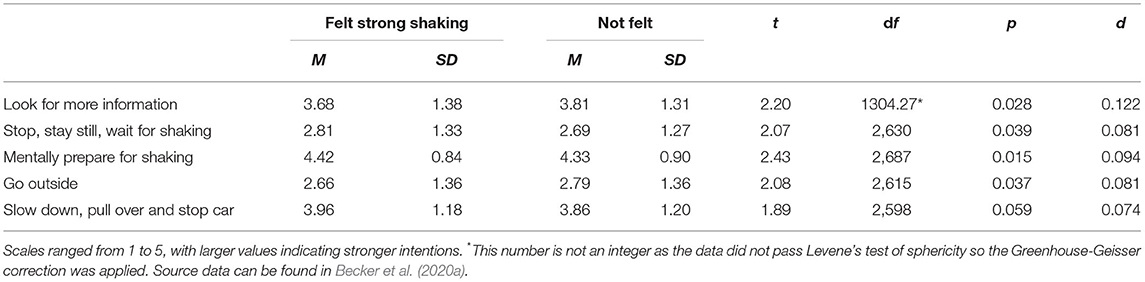

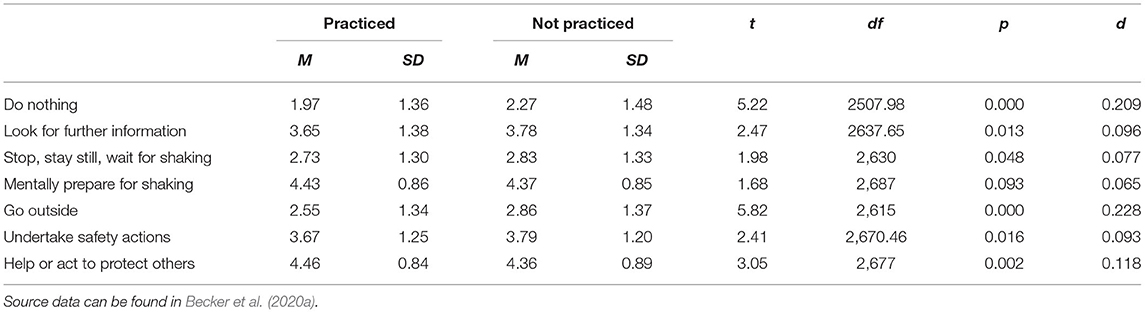

Those who had felt strong shaking were less likely to intend to look for further information and marginally less likely to slow down, pull over and stop their car than those who had not felt strong shaking ( Table 1 ). Further, those who had felt strong shaking were more likely to intend to stop, stay still and wait for shaking and to mentally prepare themselves than those who did not have prior experience of strong shaking. There were no other significant differences in intentions for the remaining actions ( p- values from 0.314 to 0.944).

Table 1 . Results of independent samples t -tests comparing mean intentions scores for a range of actions between those who have and have not felt strong shaking.

Similar to the previous findings, participants who had experienced personal injury, damage, or loss from an earthquake were more likely to intend to mentally prepare themselves for shaking ( M = 4.46, SD = 0.82) than those who had not ( M = 4.37, SD = 0.87), t (2, 687) = 2.64, p < 0.01, d = 0.10 and to slow down, pull over and stop their car ( M = 4.06, SD = 1.15) than those who had not ( M = 3.87, SD = 1.19), t (1560.69) = 3.77, p < 0.01, d = 0.19. Further, those who had personally experienced injury, loss, or damage had stronger intentions to help or act to protect others ( M = 4.47, SD = 0.86) than those who had not ( M = 4.39, SD = 0.86), t (2, 677) = 2.39, p < 0.05, d = 0.09.

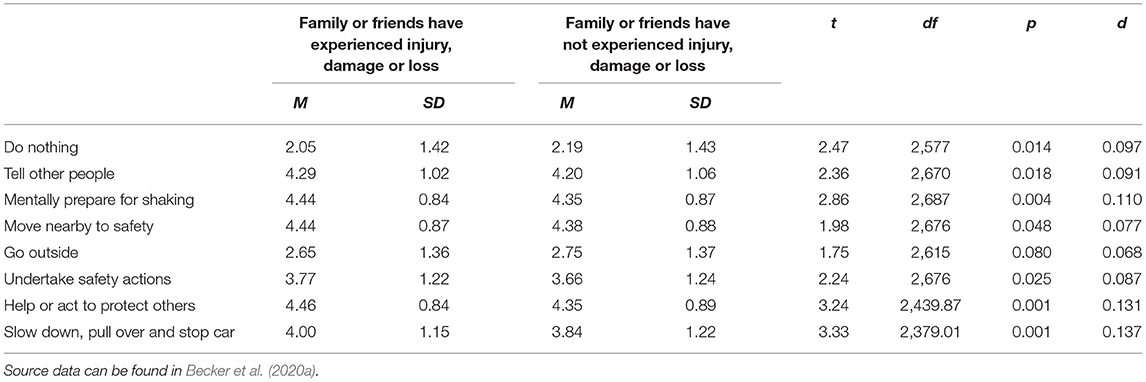

Interestingly, having a family member or friend experience injury, damage, or loss in an earthquake seemed to have more of an effect on intentions to act when given a warning than personal experience. Those who have had a family member or friend suffer injury, damage, or loss were more likely to intend to tell other people, mentally prepare, move nearby to somewhere safe, undertake safety actions such as turning off gas, help or act to protect others, and to slow down and pull their car over if driving ( Table 2 ). Further, participants with this type of experience were less likely to intend to do nothing and marginally less likely to intend to go outside than those without this experience. However, there was no difference between the two groups on intentions to look for further information ( p = 0.862), to stop and wait for the shaking ( p = 0.126), or to take specific actions such as Drop, Cover, and Hold ( p = 0.502).

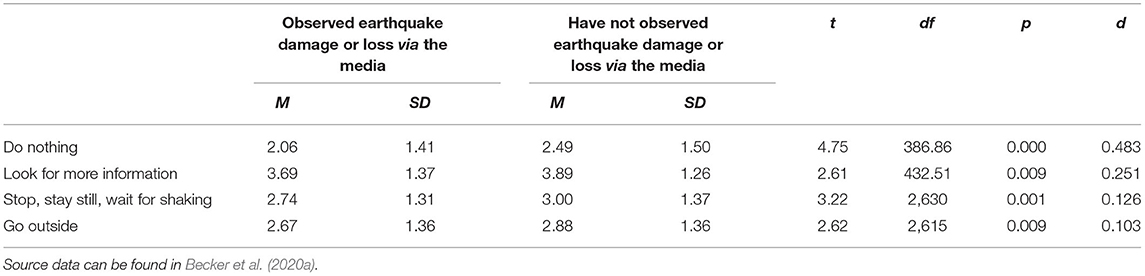

Table 2 . Results of independent samples t -tests comparing mean intentions scores for a range of actions between those who have and have not had family or friends injured, or experienced damage or loss from an earthquake.