Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

The discussion section contains the results and outcomes of a study. An effective discussion informs readers what can be learned from your experiment and provides context for the results.

What makes an effective discussion?

When you’re ready to write your discussion, you’ve already introduced the purpose of your study and provided an in-depth description of the methodology. The discussion informs readers about the larger implications of your study based on the results. Highlighting these implications while not overstating the findings can be challenging, especially when you’re submitting to a journal that selects articles based on novelty or potential impact. Regardless of what journal you are submitting to, the discussion section always serves the same purpose: concluding what your study results actually mean.

A successful discussion section puts your findings in context. It should include:

- the results of your research,

- a discussion of related research, and

- a comparison between your results and initial hypothesis.

Tip: Not all journals share the same naming conventions.

You can apply the advice in this article to the conclusion, results or discussion sections of your manuscript.

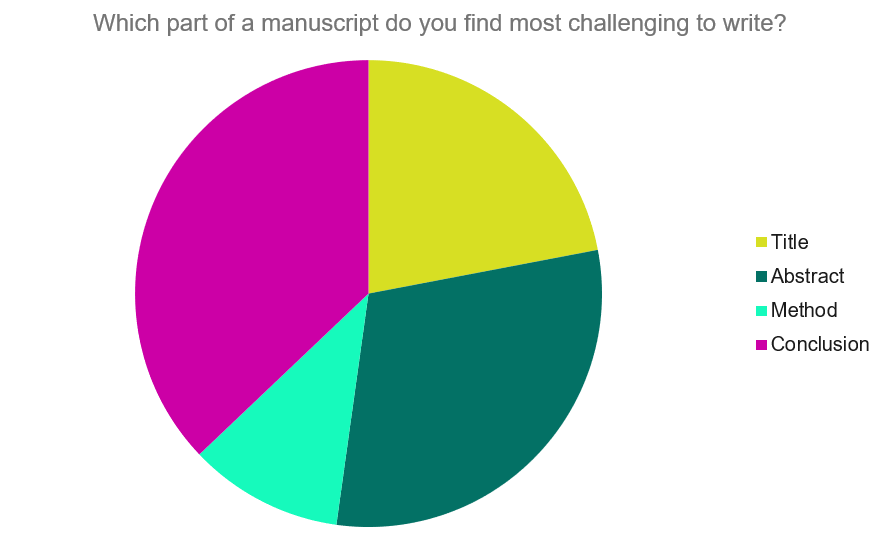

Our Early Career Researcher community tells us that the conclusion is often considered the most difficult aspect of a manuscript to write. To help, this guide provides questions to ask yourself, a basic structure to model your discussion off of and examples from published manuscripts.

Questions to ask yourself:

- Was my hypothesis correct?

- If my hypothesis is partially correct or entirely different, what can be learned from the results?

- How do the conclusions reshape or add onto the existing knowledge in the field? What does previous research say about the topic?

- Why are the results important or relevant to your audience? Do they add further evidence to a scientific consensus or disprove prior studies?

- How can future research build on these observations? What are the key experiments that must be done?

- What is the “take-home” message you want your reader to leave with?

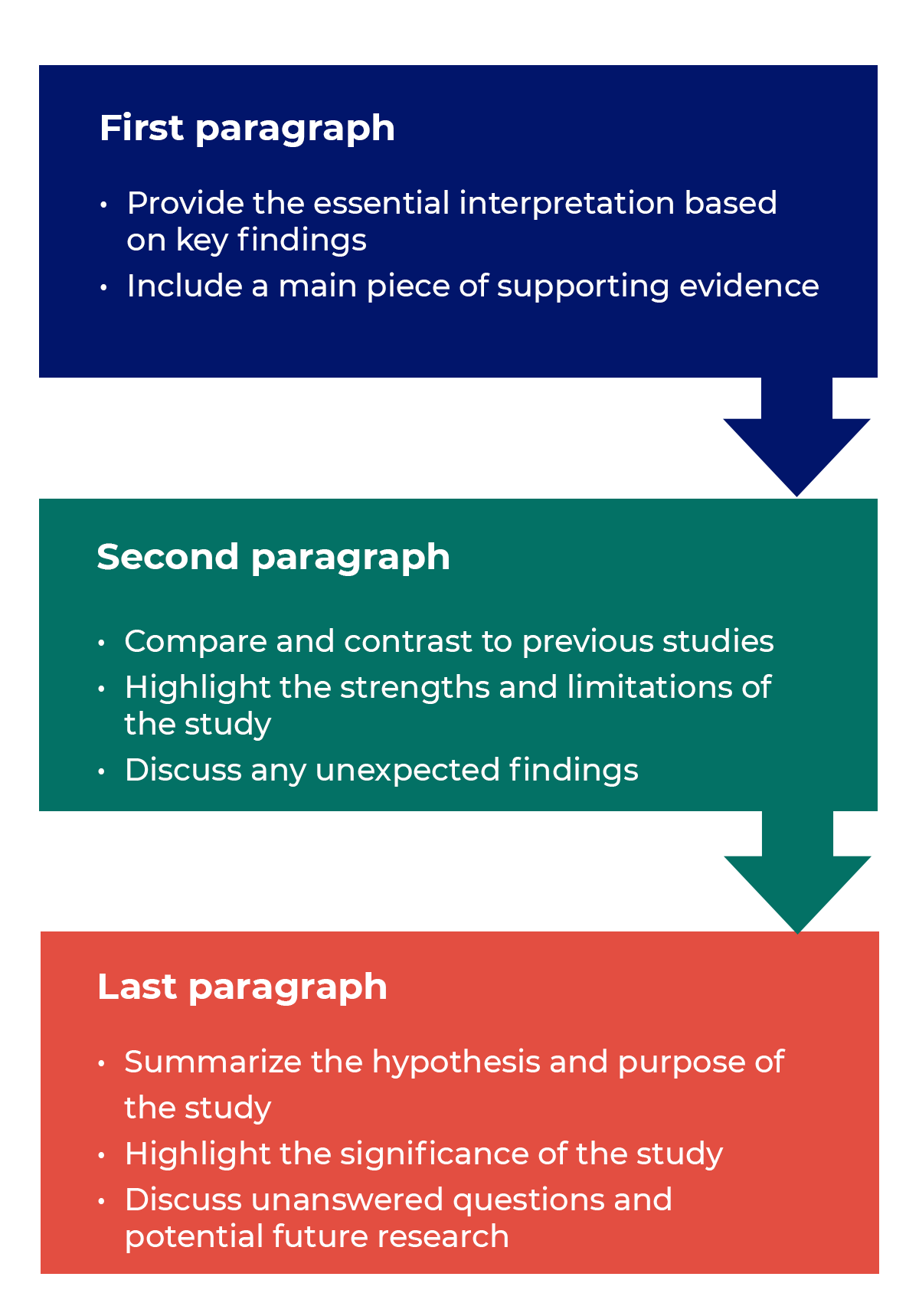

How to structure a discussion

Trying to fit a complete discussion into a single paragraph can add unnecessary stress to the writing process. If possible, you’ll want to give yourself two or three paragraphs to give the reader a comprehensive understanding of your study as a whole. Here’s one way to structure an effective discussion:

Writing Tips

While the above sections can help you brainstorm and structure your discussion, there are many common mistakes that writers revert to when having difficulties with their paper. Writing a discussion can be a delicate balance between summarizing your results, providing proper context for your research and avoiding introducing new information. Remember that your paper should be both confident and honest about the results!

- Read the journal’s guidelines on the discussion and conclusion sections. If possible, learn about the guidelines before writing the discussion to ensure you’re writing to meet their expectations.

- Begin with a clear statement of the principal findings. This will reinforce the main take-away for the reader and set up the rest of the discussion.

- Explain why the outcomes of your study are important to the reader. Discuss the implications of your findings realistically based on previous literature, highlighting both the strengths and limitations of the research.

- State whether the results prove or disprove your hypothesis. If your hypothesis was disproved, what might be the reasons?

- Introduce new or expanded ways to think about the research question. Indicate what next steps can be taken to further pursue any unresolved questions.

- If dealing with a contemporary or ongoing problem, such as climate change, discuss possible consequences if the problem is avoided.

- Be concise. Adding unnecessary detail can distract from the main findings.

Don’t

- Rewrite your abstract. Statements with “we investigated” or “we studied” generally do not belong in the discussion.

- Include new arguments or evidence not previously discussed. Necessary information and evidence should be introduced in the main body of the paper.

- Apologize. Even if your research contains significant limitations, don’t undermine your authority by including statements that doubt your methodology or execution.

- Shy away from speaking on limitations or negative results. Including limitations and negative results will give readers a complete understanding of the presented research. Potential limitations include sources of potential bias, threats to internal or external validity, barriers to implementing an intervention and other issues inherent to the study design.

- Overstate the importance of your findings. Making grand statements about how a study will fully resolve large questions can lead readers to doubt the success of the research.

Snippets of Effective Discussions:

Consumer-based actions to reduce plastic pollution in rivers: A multi-criteria decision analysis approach

Identifying reliable indicators of fitness in polar bears

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write an Abstract

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Case Study?

Weighing the pros and cons of this method of research

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

Verywell / Colleen Tighe

- Pros and Cons

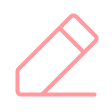

What Types of Case Studies Are Out There?

Where do you find data for a case study, how do i write a psychology case study.

A case study is an in-depth study of one person, group, or event. In a case study, nearly every aspect of the subject's life and history is analyzed to seek patterns and causes of behavior. Case studies can be used in many different fields, including psychology, medicine, education, anthropology, political science, and social work.

The point of a case study is to learn as much as possible about an individual or group so that the information can be generalized to many others. Unfortunately, case studies tend to be highly subjective, and it is sometimes difficult to generalize results to a larger population.

While case studies focus on a single individual or group, they follow a format similar to other types of psychology writing. If you are writing a case study, we got you—here are some rules of APA format to reference.

At a Glance

A case study, or an in-depth study of a person, group, or event, can be a useful research tool when used wisely. In many cases, case studies are best used in situations where it would be difficult or impossible for you to conduct an experiment. They are helpful for looking at unique situations and allow researchers to gather a lot of˜ information about a specific individual or group of people. However, it's important to be cautious of any bias we draw from them as they are highly subjective.

What Are the Benefits and Limitations of Case Studies?

A case study can have its strengths and weaknesses. Researchers must consider these pros and cons before deciding if this type of study is appropriate for their needs.

One of the greatest advantages of a case study is that it allows researchers to investigate things that are often difficult or impossible to replicate in a lab. Some other benefits of a case study:

- Allows researchers to capture information on the 'how,' 'what,' and 'why,' of something that's implemented

- Gives researchers the chance to collect information on why one strategy might be chosen over another

- Permits researchers to develop hypotheses that can be explored in experimental research

On the other hand, a case study can have some drawbacks:

- It cannot necessarily be generalized to the larger population

- Cannot demonstrate cause and effect

- It may not be scientifically rigorous

- It can lead to bias

Researchers may choose to perform a case study if they want to explore a unique or recently discovered phenomenon. Through their insights, researchers develop additional ideas and study questions that might be explored in future studies.

It's important to remember that the insights from case studies cannot be used to determine cause-and-effect relationships between variables. However, case studies may be used to develop hypotheses that can then be addressed in experimental research.

Case Study Examples

There have been a number of notable case studies in the history of psychology. Much of Freud's work and theories were developed through individual case studies. Some great examples of case studies in psychology include:

- Anna O : Anna O. was a pseudonym of a woman named Bertha Pappenheim, a patient of a physician named Josef Breuer. While she was never a patient of Freud's, Freud and Breuer discussed her case extensively. The woman was experiencing symptoms of a condition that was then known as hysteria and found that talking about her problems helped relieve her symptoms. Her case played an important part in the development of talk therapy as an approach to mental health treatment.

- Phineas Gage : Phineas Gage was a railroad employee who experienced a terrible accident in which an explosion sent a metal rod through his skull, damaging important portions of his brain. Gage recovered from his accident but was left with serious changes in both personality and behavior.

- Genie : Genie was a young girl subjected to horrific abuse and isolation. The case study of Genie allowed researchers to study whether language learning was possible, even after missing critical periods for language development. Her case also served as an example of how scientific research may interfere with treatment and lead to further abuse of vulnerable individuals.

Such cases demonstrate how case research can be used to study things that researchers could not replicate in experimental settings. In Genie's case, her horrific abuse denied her the opportunity to learn a language at critical points in her development.

This is clearly not something researchers could ethically replicate, but conducting a case study on Genie allowed researchers to study phenomena that are otherwise impossible to reproduce.

There are a few different types of case studies that psychologists and other researchers might use:

- Collective case studies : These involve studying a group of individuals. Researchers might study a group of people in a certain setting or look at an entire community. For example, psychologists might explore how access to resources in a community has affected the collective mental well-being of those who live there.

- Descriptive case studies : These involve starting with a descriptive theory. The subjects are then observed, and the information gathered is compared to the pre-existing theory.

- Explanatory case studies : These are often used to do causal investigations. In other words, researchers are interested in looking at factors that may have caused certain things to occur.

- Exploratory case studies : These are sometimes used as a prelude to further, more in-depth research. This allows researchers to gather more information before developing their research questions and hypotheses .

- Instrumental case studies : These occur when the individual or group allows researchers to understand more than what is initially obvious to observers.

- Intrinsic case studies : This type of case study is when the researcher has a personal interest in the case. Jean Piaget's observations of his own children are good examples of how an intrinsic case study can contribute to the development of a psychological theory.

The three main case study types often used are intrinsic, instrumental, and collective. Intrinsic case studies are useful for learning about unique cases. Instrumental case studies help look at an individual to learn more about a broader issue. A collective case study can be useful for looking at several cases simultaneously.

The type of case study that psychology researchers use depends on the unique characteristics of the situation and the case itself.

There are a number of different sources and methods that researchers can use to gather information about an individual or group. Six major sources that have been identified by researchers are:

- Archival records : Census records, survey records, and name lists are examples of archival records.

- Direct observation : This strategy involves observing the subject, often in a natural setting . While an individual observer is sometimes used, it is more common to utilize a group of observers.

- Documents : Letters, newspaper articles, administrative records, etc., are the types of documents often used as sources.

- Interviews : Interviews are one of the most important methods for gathering information in case studies. An interview can involve structured survey questions or more open-ended questions.

- Participant observation : When the researcher serves as a participant in events and observes the actions and outcomes, it is called participant observation.

- Physical artifacts : Tools, objects, instruments, and other artifacts are often observed during a direct observation of the subject.

If you have been directed to write a case study for a psychology course, be sure to check with your instructor for any specific guidelines you need to follow. If you are writing your case study for a professional publication, check with the publisher for their specific guidelines for submitting a case study.

Here is a general outline of what should be included in a case study.

Section 1: A Case History

This section will have the following structure and content:

Background information : The first section of your paper will present your client's background. Include factors such as age, gender, work, health status, family mental health history, family and social relationships, drug and alcohol history, life difficulties, goals, and coping skills and weaknesses.

Description of the presenting problem : In the next section of your case study, you will describe the problem or symptoms that the client presented with.

Describe any physical, emotional, or sensory symptoms reported by the client. Thoughts, feelings, and perceptions related to the symptoms should also be noted. Any screening or diagnostic assessments that are used should also be described in detail and all scores reported.

Your diagnosis : Provide your diagnosis and give the appropriate Diagnostic and Statistical Manual code. Explain how you reached your diagnosis, how the client's symptoms fit the diagnostic criteria for the disorder(s), or any possible difficulties in reaching a diagnosis.

Section 2: Treatment Plan

This portion of the paper will address the chosen treatment for the condition. This might also include the theoretical basis for the chosen treatment or any other evidence that might exist to support why this approach was chosen.

- Cognitive behavioral approach : Explain how a cognitive behavioral therapist would approach treatment. Offer background information on cognitive behavioral therapy and describe the treatment sessions, client response, and outcome of this type of treatment. Make note of any difficulties or successes encountered by your client during treatment.

- Humanistic approach : Describe a humanistic approach that could be used to treat your client, such as client-centered therapy . Provide information on the type of treatment you chose, the client's reaction to the treatment, and the end result of this approach. Explain why the treatment was successful or unsuccessful.

- Psychoanalytic approach : Describe how a psychoanalytic therapist would view the client's problem. Provide some background on the psychoanalytic approach and cite relevant references. Explain how psychoanalytic therapy would be used to treat the client, how the client would respond to therapy, and the effectiveness of this treatment approach.

- Pharmacological approach : If treatment primarily involves the use of medications, explain which medications were used and why. Provide background on the effectiveness of these medications and how monotherapy may compare with an approach that combines medications with therapy or other treatments.

This section of a case study should also include information about the treatment goals, process, and outcomes.

When you are writing a case study, you should also include a section where you discuss the case study itself, including the strengths and limitiations of the study. You should note how the findings of your case study might support previous research.

In your discussion section, you should also describe some of the implications of your case study. What ideas or findings might require further exploration? How might researchers go about exploring some of these questions in additional studies?

Need More Tips?

Here are a few additional pointers to keep in mind when formatting your case study:

- Never refer to the subject of your case study as "the client." Instead, use their name or a pseudonym.

- Read examples of case studies to gain an idea about the style and format.

- Remember to use APA format when citing references .

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011;11:100.

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011 Jun 27;11:100. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Gagnon, Yves-Chantal. The Case Study as Research Method: A Practical Handbook . Canada, Chicago Review Press Incorporated DBA Independent Pub Group, 2010.

Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . United States, SAGE Publications, 2017.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

We use essential cookies to make Venngage work. By clicking “Accept All Cookies”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts.

Manage Cookies

Cookies and similar technologies collect certain information about how you’re using our website. Some of them are essential, and without them you wouldn’t be able to use Venngage. But others are optional, and you get to choose whether we use them or not.

Strictly Necessary Cookies

These cookies are always on, as they’re essential for making Venngage work, and making it safe. Without these cookies, services you’ve asked for can’t be provided.

Show cookie providers

- Google Login

Functionality Cookies

These cookies help us provide enhanced functionality and personalisation, and remember your settings. They may be set by us or by third party providers.

Performance Cookies

These cookies help us analyze how many people are using Venngage, where they come from and how they're using it. If you opt out of these cookies, we can’t get feedback to make Venngage better for you and all our users.

- Google Analytics

Targeting Cookies

These cookies are set by our advertising partners to track your activity and show you relevant Venngage ads on other sites as you browse the internet.

- Google Tag Manager

- Infographics

- Daily Infographics

- Graphic Design

- Graphs and Charts

- Data Visualization

- Human Resources

- Training and Development

- Beginner Guides

Blog Case Study

How to Present a Case Study like a Pro (With Examples)

By Danesh Ramuthi , Sep 07, 2023

In today’s world, where data is king and persuasion is queen, a killer case study can change the game. Think high-powered meetings at fancy companies or even nailing that college presentation: a rock-solid case study could be the magic weapon you need.

Okay, let’s get real: case studies can be kinda snooze-worthy. But guess what? They don’t have to be!

In this article, you’ll learn all about crafting and presenting powerful case studies. From selecting the right metrics to using persuasive narrative techniques, I will cover every element that transforms a mere report into a compelling case study.

And if you’re feeling a little lost, don’t worry! There are cool tools like Venngage’s Case Study Creator to help you whip up something awesome, even if you’re short on time. Plus, the pre-designed case study templates are like instant polish because let’s be honest, everyone loves a shortcut.

Click to jump ahead:

What is a case study presentation?

Purpose of presenting a case study, how to structure a case study presentation, how long should a case study presentation be, 5 case study presentation templates, tips for delivering an effective case study presentation, common mistakes to avoid in a case study presentation, how to present a case study faqs.

A case study presentation involves a comprehensive examination of a specific subject, which could range from an individual, group, location, event, organization or phenomenon.

They’re like puzzles you get to solve with the audience, all while making you think outside the box.

Unlike a basic report or whitepaper, the purpose of a case study presentation is to stimulate critical thinking among the viewers.

The primary objective of a case study is to provide an extensive and profound comprehension of the chosen topic. You don’t just throw numbers at your audience. You use examples and real-life cases to make you think and see things from different angles.

The primary purpose of presenting a case study is to offer a comprehensive, evidence-based argument that informs, persuades and engages your audience.

Here’s the juicy part: presenting that case study can be your secret weapon. Whether you’re pitching a groundbreaking idea to a room full of suits or trying to impress your professor with your A-game, a well-crafted case study can be the magic dust that sprinkles brilliance over your words.

Think of it like digging into a puzzle you can’t quite crack . A case study lets you explore every piece, turn it over and see how it fits together. This close-up look helps you understand the whole picture, not just a blurry snapshot.

It’s also your chance to showcase how you analyze things, step by step, until you reach a conclusion. It’s all about being open and honest about how you got there.

Besides, presenting a case study gives you an opportunity to connect data and real-world scenarios in a compelling narrative. It helps to make your argument more relatable and accessible, increasing its impact on your audience.

One of the contexts where case studies can be very helpful is during the job interview. In some job interviews, you as candidates may be asked to present a case study as part of the selection process.

Having a case study presentation prepared allows the candidate to demonstrate their ability to understand complex issues, formulate strategies and communicate their ideas effectively.

The way you present a case study can make all the difference in how it’s received. A well-structured presentation not only holds the attention of your audience but also ensures that your key points are communicated clearly and effectively.

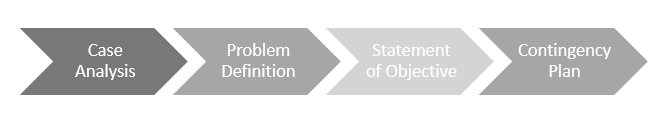

In this section, let’s go through the key steps that’ll help you structure your case study presentation for maximum impact.

Let’s get into it.

Open with an introductory overview

Start by introducing the subject of your case study and its relevance. Explain why this case study is important and who would benefit from the insights gained. This is your opportunity to grab your audience’s attention.

Explain the problem in question

Dive into the problem or challenge that the case study focuses on. Provide enough background information for the audience to understand the issue. If possible, quantify the problem using data or metrics to show the magnitude or severity.

Detail the solutions to solve the problem

After outlining the problem, describe the steps taken to find a solution. This could include the methodology, any experiments or tests performed and the options that were considered. Make sure to elaborate on why the final solution was chosen over the others.

Key stakeholders Involved

Talk about the individuals, groups or organizations that were directly impacted by or involved in the problem and its solution.

Stakeholders may experience a range of outcomes—some may benefit, while others could face setbacks.

For example, in a business transformation case study, employees could face job relocations or changes in work culture, while shareholders might be looking at potential gains or losses.

Discuss the key results & outcomes

Discuss the results of implementing the solution. Use data and metrics to back up your statements. Did the solution meet its objectives? What impact did it have on the stakeholders? Be honest about any setbacks or areas for improvement as well.

Include visuals to support your analysis

Visual aids can be incredibly effective in helping your audience grasp complex issues. Utilize charts, graphs, images or video clips to supplement your points. Make sure to explain each visual and how it contributes to your overall argument.

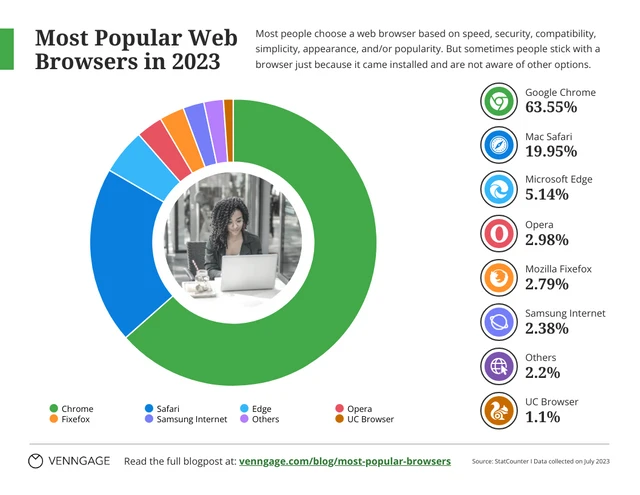

Pie charts illustrate the proportion of different components within a whole, useful for visualizing market share, budget allocation or user demographics.

This is particularly useful especially if you’re displaying survey results in your case study presentation.

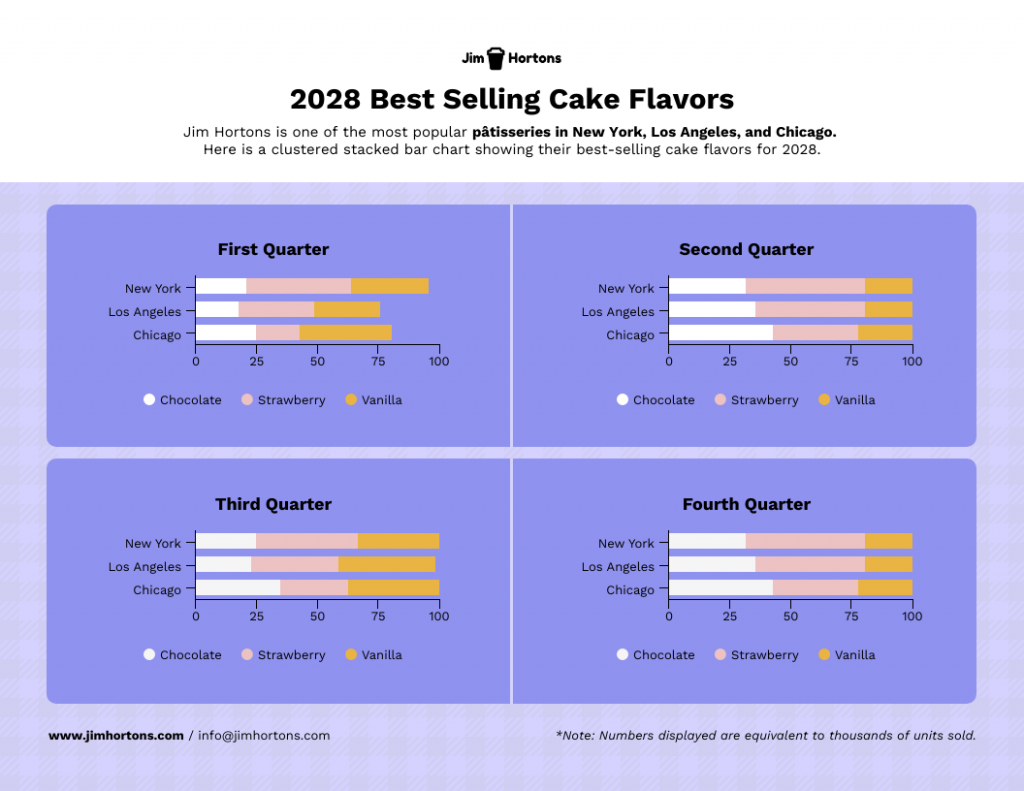

Stacked charts on the other hand are perfect for visualizing composition and trends. This is great for analyzing things like customer demographics, product breakdowns or budget allocation in your case study.

Consider this example of a stacked bar chart template. It provides a straightforward summary of the top-selling cake flavors across various locations, offering a quick and comprehensive view of the data.

Not the chart you’re looking for? Browse Venngage’s gallery of chart templates to find the perfect one that’ll captivate your audience and level up your data storytelling.

Recommendations and next steps

Wrap up by providing recommendations based on the case study findings. Outline the next steps that stakeholders should take to either expand on the success of the project or address any remaining challenges.

Acknowledgments and references

Thank the people who contributed to the case study and helped in the problem-solving process. Cite any external resources, reports or data sets that contributed to your analysis.

Feedback & Q&A session

Open the floor for questions and feedback from your audience. This allows for further discussion and can provide additional insights that may not have been considered previously.

Closing remarks

Conclude the presentation by summarizing the key points and emphasizing the takeaways. Thank your audience for their time and participation and express your willingness to engage in further discussions or collaborations on the subject.

Well, the length of a case study presentation can vary depending on the complexity of the topic and the needs of your audience. However, a typical business or academic presentation often lasts between 15 to 30 minutes.

This time frame usually allows for a thorough explanation of the case while maintaining audience engagement. However, always consider leaving a few minutes at the end for a Q&A session to address any questions or clarify points made during the presentation.

When it comes to presenting a compelling case study, having a well-structured template can be a game-changer.

It helps you organize your thoughts, data and findings in a coherent and visually pleasing manner.

Not all case studies are created equal and different scenarios require distinct approaches for maximum impact.

To save you time and effort, I have curated a list of 5 versatile case study presentation templates, each designed for specific needs and audiences.

Here are some best case study presentation examples that showcase effective strategies for engaging your audience and conveying complex information clearly.

1) Lab report case study template

Ever feel like your research gets lost in a world of endless numbers and jargon? Lab case studies are your way out!

Think of it as building a bridge between your cool experiment and everyone else. It’s more than just reporting results – it’s explaining the “why” and “how” in a way that grabs attention and makes sense.

This lap report template acts as a blueprint for your report, guiding you through each essential section (introduction, methods, results, etc.) in a logical order.

2) Product case study template

It’s time you ditch those boring slideshows and bullet points because I’ve got a better way to win over clients: product case study templates.

Instead of just listing features and benefits, you get to create a clear and concise story that shows potential clients exactly what your product can do for them. It’s like painting a picture they can easily visualize, helping them understand the value your product brings to the table.

Grab the template below, fill in the details, and watch as your product’s impact comes to life!

3) Content marketing case study template

In digital marketing, showcasing your accomplishments is as vital as achieving them.

A well-crafted case study not only acts as a testament to your successes but can also serve as an instructional tool for others.

With this coral content marketing case study template—a perfect blend of vibrant design and structured documentation, you can narrate your marketing triumphs effectively.

4) Case study psychology template

Understanding how people tick is one of psychology’s biggest quests and case studies are like magnifying glasses for the mind. They offer in-depth looks at real-life behaviors, emotions and thought processes, revealing fascinating insights into what makes us human.

Writing a top-notch case study, though, can be a challenge. It requires careful organization, clear presentation and meticulous attention to detail. That’s where a good case study psychology template comes in handy.

Think of it as a helpful guide, taking care of formatting and structure while you focus on the juicy content. No more wrestling with layouts or margins – just pour your research magic into crafting a compelling narrative.

5) Lead generation case study template

Lead generation can be a real head-scratcher. But here’s a little help: a lead generation case study.

Think of it like a friendly handshake and a confident resume all rolled into one. It’s your chance to showcase your expertise, share real-world successes and offer valuable insights. Potential clients get to see your track record, understand your approach and decide if you’re the right fit.

No need to start from scratch, though. This lead generation case study template guides you step-by-step through crafting a clear, compelling narrative that highlights your wins and offers actionable tips for others. Fill in the gaps with your specific data and strategies, and voilà! You’ve got a powerful tool to attract new customers.

Related: 15+ Professional Case Study Examples [Design Tips + Templates]

So, you’ve spent hours crafting the perfect case study and are now tasked with presenting it. Crafting the case study is only half the battle; delivering it effectively is equally important.

Whether you’re facing a room of executives, academics or potential clients, how you present your findings can make a significant difference in how your work is received.

Forget boring reports and snooze-inducing presentations! Let’s make your case study sing. Here are some key pointers to turn information into an engaging and persuasive performance:

- Know your audience : Tailor your presentation to the knowledge level and interests of your audience. Remember to use language and examples that resonate with them.

- Rehearse : Rehearsing your case study presentation is the key to a smooth delivery and for ensuring that you stay within the allotted time. Practice helps you fine-tune your pacing, hone your speaking skills with good word pronunciations and become comfortable with the material, leading to a more confident, conversational and effective presentation.

- Start strong : Open with a compelling introduction that grabs your audience’s attention. You might want to use an interesting statistic, a provocative question or a brief story that sets the stage for your case study.

- Be clear and concise : Avoid jargon and overly complex sentences. Get to the point quickly and stay focused on your objectives.

- Use visual aids : Incorporate slides with graphics, charts or videos to supplement your verbal presentation. Make sure they are easy to read and understand.

- Tell a story : Use storytelling techniques to make the case study more engaging. A well-told narrative can help you make complex data more relatable and easier to digest.

Ditching the dry reports and slide decks? Venngage’s case study templates let you wow customers with your solutions and gain insights to improve your business plan. Pre-built templates, visual magic and customer captivation – all just a click away. Go tell your story and watch them say “wow!”

Crafting and presenting a case study is a skillful task that requires careful planning and execution. While a well-prepared case study can be a powerful tool for showcasing your successes, educating your audience or encouraging discussion, there are several pitfalls you should avoid to make your presentation as effective as possible. Here are some common mistakes to watch out for:

Overloading with information

A case study is not an encyclopedia. Overloading your presentation with excessive data, text or jargon can make it cumbersome and difficult for the audience to digest the key points. Stick to what’s essential and impactful.

Lack of structure

Jumping haphazardly between points or topics can confuse your audience. A well-structured presentation, with a logical flow from introduction to conclusion, is crucial for effective communication.

Ignoring the audience

Different audiences have different needs and levels of understanding. Failing to adapt your presentation to your audience can result in a disconnect and a less impactful presentation.

Poor visual elements

While content is king, poor design or lack of visual elements can make your case study dull or hard to follow. Make sure you use high-quality images, graphs and other visual aids to support your narrative.

Not focusing on results

A case study aims to showcase a problem and its solution, but what most people care about are the results. Failing to highlight or adequately explain the outcomes can make your presentation fall flat.

How to start a case study presentation?

Starting a case study presentation effectively involves a few key steps:

- Grab attention : Open with a hook—an intriguing statistic, a provocative question or a compelling visual—to engage your audience from the get-go.

- Set the stage : Briefly introduce the subject, context and relevance of the case study to give your audience an idea of what to expect.

- Outline objectives : Clearly state what the case study aims to achieve. Are you solving a problem, proving a point or showcasing a success?

- Agenda : Give a quick outline of the key sections or topics you’ll cover to help the audience follow along.

- Set expectations : Let your audience know what you want them to take away from the presentation, whether it’s knowledge, inspiration or a call to action.

How to present a case study on PowerPoint and on Google Slides?

Presenting a case study on PowerPoint and Google Slides involves a structured approach for clarity and impact using presentation slides:

- Title slide : Start with a title slide that includes the name of the case study, your name and any relevant institutional affiliations.

- Introduction : Follow with a slide that outlines the problem or situation your case study addresses. Include a hook to engage the audience.

- Objectives : Clearly state the goals of the case study in a dedicated slide.

- Findings : Use charts, graphs and bullet points to present your findings succinctly.

- Analysis : Discuss what the findings mean, drawing on supporting data or secondary research as necessary.

- Conclusion : Summarize key takeaways and results.

- Q&A : End with a slide inviting questions from the audience.

What’s the role of analysis in a case study presentation?

The role of analysis in a case study presentation is to interpret the data and findings, providing context and meaning to them.

It helps your audience understand the implications of the case study, connects the dots between the problem and the solution and may offer recommendations for future action.

Is it important to include real data and results in the presentation?

Yes, including real data and results in a case study presentation is crucial to show experience, credibility and impact. Authentic data lends weight to your findings and conclusions, enabling the audience to trust your analysis and take your recommendations more seriously

How do I conclude a case study presentation effectively?

To conclude a case study presentation effectively, summarize the key findings, insights and recommendations in a clear and concise manner.

End with a strong call-to-action or a thought-provoking question to leave a lasting impression on your audience.

What’s the best way to showcase data in a case study presentation ?

The best way to showcase data in a case study presentation is through visual aids like charts, graphs and infographics which make complex information easily digestible, engaging and creative.

Don’t just report results, visualize them! This template for example lets you transform your social media case study into a captivating infographic that sparks conversation.

Choose the type of visual that best represents the data you’re showing; for example, use bar charts for comparisons or pie charts for parts of a whole.

Ensure that the visuals are high-quality and clearly labeled, so the audience can quickly grasp the key points.

Keep the design consistent and simple, avoiding clutter or overly complex visuals that could distract from the message.

Choose a template that perfectly suits your case study where you can utilize different visual aids for maximum impact.

Need more inspiration on how to turn numbers into impact with the help of infographics? Our ready-to-use infographic templates take the guesswork out of creating visual impact for your case studies with just a few clicks.

Related: 10+ Case Study Infographic Templates That Convert

Congrats on mastering the art of compelling case study presentations! This guide has equipped you with all the essentials, from structure and nuances to avoiding common pitfalls. You’re ready to impress any audience, whether in the boardroom, the classroom or beyond.

And remember, you’re not alone in this journey. Venngage’s Case Study Creator is your trusty companion, ready to elevate your presentations from ordinary to extraordinary. So, let your confidence shine, leverage your newly acquired skills and prepare to deliver presentations that truly resonate.

Go forth and make a lasting impact!

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Table of Contents

A case study is a research method that involves an in-depth examination and analysis of a particular phenomenon or case, such as an individual, organization, community, event, or situation.

It is a qualitative research approach that aims to provide a detailed and comprehensive understanding of the case being studied. Case studies typically involve multiple sources of data, including interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, which are analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, and grounded theory. The findings of a case study are often used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Types of Case Study

Types and Methods of Case Study are as follows:

Single-Case Study

A single-case study is an in-depth analysis of a single case. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand a specific phenomenon in detail.

For Example , A researcher might conduct a single-case study on a particular individual to understand their experiences with a particular health condition or a specific organization to explore their management practices. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a single-case study are often used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Multiple-Case Study

A multiple-case study involves the analysis of several cases that are similar in nature. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to identify similarities and differences between the cases.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a multiple-case study on several companies to explore the factors that contribute to their success or failure. The researcher collects data from each case, compares and contrasts the findings, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as comparative analysis or pattern-matching. The findings of a multiple-case study can be used to develop theories, inform policy or practice, or generate new research questions.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is used to explore a new or understudied phenomenon. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to generate hypotheses or theories about the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an exploratory case study on a new technology to understand its potential impact on society. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as grounded theory or content analysis. The findings of an exploratory case study can be used to generate new research questions, develop theories, or inform policy or practice.

Descriptive Case Study

A descriptive case study is used to describe a particular phenomenon in detail. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon.

For Example, a researcher might conduct a descriptive case study on a particular community to understand its social and economic characteristics. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of a descriptive case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Instrumental Case Study

An instrumental case study is used to understand a particular phenomenon that is instrumental in achieving a particular goal. This type of case study is useful when the researcher wants to understand the role of the phenomenon in achieving the goal.

For Example, a researcher might conduct an instrumental case study on a particular policy to understand its impact on achieving a particular goal, such as reducing poverty. The researcher collects data from multiple sources, such as interviews, observations, and documents, and uses various techniques to analyze the data, such as content analysis or thematic analysis. The findings of an instrumental case study can be used to inform policy or practice or generate new research questions.

Case Study Data Collection Methods

Here are some common data collection methods for case studies:

Interviews involve asking questions to individuals who have knowledge or experience relevant to the case study. Interviews can be structured (where the same questions are asked to all participants) or unstructured (where the interviewer follows up on the responses with further questions). Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

Observations

Observations involve watching and recording the behavior and activities of individuals or groups relevant to the case study. Observations can be participant (where the researcher actively participates in the activities) or non-participant (where the researcher observes from a distance). Observations can be recorded using notes, audio or video recordings, or photographs.

Documents can be used as a source of information for case studies. Documents can include reports, memos, emails, letters, and other written materials related to the case study. Documents can be collected from the case study participants or from public sources.

Surveys involve asking a set of questions to a sample of individuals relevant to the case study. Surveys can be administered in person, over the phone, through mail or email, or online. Surveys can be used to gather information on attitudes, opinions, or behaviors related to the case study.

Artifacts are physical objects relevant to the case study. Artifacts can include tools, equipment, products, or other objects that provide insights into the case study phenomenon.

How to conduct Case Study Research

Conducting a case study research involves several steps that need to be followed to ensure the quality and rigor of the study. Here are the steps to conduct case study research:

- Define the research questions: The first step in conducting a case study research is to define the research questions. The research questions should be specific, measurable, and relevant to the case study phenomenon under investigation.

- Select the case: The next step is to select the case or cases to be studied. The case should be relevant to the research questions and should provide rich and diverse data that can be used to answer the research questions.

- Collect data: Data can be collected using various methods, such as interviews, observations, documents, surveys, and artifacts. The data collection method should be selected based on the research questions and the nature of the case study phenomenon.

- Analyze the data: The data collected from the case study should be analyzed using various techniques, such as content analysis, thematic analysis, or grounded theory. The analysis should be guided by the research questions and should aim to provide insights and conclusions relevant to the research questions.

- Draw conclusions: The conclusions drawn from the case study should be based on the data analysis and should be relevant to the research questions. The conclusions should be supported by evidence and should be clearly stated.

- Validate the findings: The findings of the case study should be validated by reviewing the data and the analysis with participants or other experts in the field. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Write the report: The final step is to write the report of the case study research. The report should provide a clear description of the case study phenomenon, the research questions, the data collection methods, the data analysis, the findings, and the conclusions. The report should be written in a clear and concise manner and should follow the guidelines for academic writing.

Examples of Case Study

Here are some examples of case study research:

- The Hawthorne Studies : Conducted between 1924 and 1932, the Hawthorne Studies were a series of case studies conducted by Elton Mayo and his colleagues to examine the impact of work environment on employee productivity. The studies were conducted at the Hawthorne Works plant of the Western Electric Company in Chicago and included interviews, observations, and experiments.

- The Stanford Prison Experiment: Conducted in 1971, the Stanford Prison Experiment was a case study conducted by Philip Zimbardo to examine the psychological effects of power and authority. The study involved simulating a prison environment and assigning participants to the role of guards or prisoners. The study was controversial due to the ethical issues it raised.

- The Challenger Disaster: The Challenger Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Space Shuttle Challenger explosion in 1986. The study included interviews, observations, and analysis of data to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

- The Enron Scandal: The Enron Scandal was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the Enron Corporation’s bankruptcy in 2001. The study included interviews, analysis of financial data, and review of documents to identify the accounting practices, corporate culture, and ethical issues that led to the company’s downfall.

- The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster : The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster was a case study conducted to examine the causes of the nuclear accident that occurred at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant in Japan in 2011. The study included interviews, analysis of data, and review of documents to identify the technical, organizational, and cultural factors that contributed to the disaster.

Application of Case Study

Case studies have a wide range of applications across various fields and industries. Here are some examples:

Business and Management

Case studies are widely used in business and management to examine real-life situations and develop problem-solving skills. Case studies can help students and professionals to develop a deep understanding of business concepts, theories, and best practices.

Case studies are used in healthcare to examine patient care, treatment options, and outcomes. Case studies can help healthcare professionals to develop critical thinking skills, diagnose complex medical conditions, and develop effective treatment plans.

Case studies are used in education to examine teaching and learning practices. Case studies can help educators to develop effective teaching strategies, evaluate student progress, and identify areas for improvement.

Social Sciences

Case studies are widely used in social sciences to examine human behavior, social phenomena, and cultural practices. Case studies can help researchers to develop theories, test hypotheses, and gain insights into complex social issues.

Law and Ethics

Case studies are used in law and ethics to examine legal and ethical dilemmas. Case studies can help lawyers, policymakers, and ethical professionals to develop critical thinking skills, analyze complex cases, and make informed decisions.

Purpose of Case Study

The purpose of a case study is to provide a detailed analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. A case study is a qualitative research method that involves the in-depth exploration and analysis of a particular case, which can be an individual, group, organization, event, or community.

The primary purpose of a case study is to generate a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the case, including its history, context, and dynamics. Case studies can help researchers to identify and examine the underlying factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and detailed understanding of the case, which can inform future research, practice, or policy.

Case studies can also serve other purposes, including:

- Illustrating a theory or concept: Case studies can be used to illustrate and explain theoretical concepts and frameworks, providing concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Developing hypotheses: Case studies can help to generate hypotheses about the causal relationships between different factors and outcomes, which can be tested through further research.

- Providing insight into complex issues: Case studies can provide insights into complex and multifaceted issues, which may be difficult to understand through other research methods.

- Informing practice or policy: Case studies can be used to inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

Advantages of Case Study Research

There are several advantages of case study research, including:

- In-depth exploration: Case study research allows for a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific phenomenon, issue, or problem in its real-life context. This can provide a comprehensive understanding of the case and its dynamics, which may not be possible through other research methods.

- Rich data: Case study research can generate rich and detailed data, including qualitative data such as interviews, observations, and documents. This can provide a nuanced understanding of the case and its complexity.

- Holistic perspective: Case study research allows for a holistic perspective of the case, taking into account the various factors, processes, and mechanisms that contribute to the case and its outcomes. This can help to develop a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of the case.

- Theory development: Case study research can help to develop and refine theories and concepts by providing empirical evidence and concrete examples of how they can be applied in real-life situations.

- Practical application: Case study research can inform practice or policy by identifying best practices, lessons learned, or areas for improvement.

- Contextualization: Case study research takes into account the specific context in which the case is situated, which can help to understand how the case is influenced by the social, cultural, and historical factors of its environment.

Limitations of Case Study Research

There are several limitations of case study research, including:

- Limited generalizability : Case studies are typically focused on a single case or a small number of cases, which limits the generalizability of the findings. The unique characteristics of the case may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, which may limit the external validity of the research.

- Biased sampling: Case studies may rely on purposive or convenience sampling, which can introduce bias into the sample selection process. This may limit the representativeness of the sample and the generalizability of the findings.

- Subjectivity: Case studies rely on the interpretation of the researcher, which can introduce subjectivity into the analysis. The researcher’s own biases, assumptions, and perspectives may influence the findings, which may limit the objectivity of the research.

- Limited control: Case studies are typically conducted in naturalistic settings, which limits the control that the researcher has over the environment and the variables being studied. This may limit the ability to establish causal relationships between variables.

- Time-consuming: Case studies can be time-consuming to conduct, as they typically involve a detailed exploration and analysis of a specific case. This may limit the feasibility of conducting multiple case studies or conducting case studies in a timely manner.

- Resource-intensive: Case studies may require significant resources, including time, funding, and expertise. This may limit the ability of researchers to conduct case studies in resource-constrained settings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Survey Research – Types, Methods, Examples

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What the Case Study Method Really Teaches

- Nitin Nohria

Seven meta-skills that stick even if the cases fade from memory.

It’s been 100 years since Harvard Business School began using the case study method. Beyond teaching specific subject matter, the case study method excels in instilling meta-skills in students. This article explains the importance of seven such skills: preparation, discernment, bias recognition, judgement, collaboration, curiosity, and self-confidence.

During my decade as dean of Harvard Business School, I spent hundreds of hours talking with our alumni. To enliven these conversations, I relied on a favorite question: “What was the most important thing you learned from your time in our MBA program?”

- Nitin Nohria is the George F. Baker Jr. Professor at Harvard Business School and the former dean of HBS.

Partner Center

How to write a case study — examples, templates, and tools

It’s a marketer’s job to communicate the effectiveness of a product or service to potential and current customers to convince them to buy and keep business moving. One of the best methods for doing this is to share success stories that are relatable to prospects and customers based on their pain points, experiences, and overall needs.

That’s where case studies come in. Case studies are an essential part of a content marketing plan. These in-depth stories of customer experiences are some of the most effective at demonstrating the value of a product or service. Yet many marketers don’t use them, whether because of their regimented formats or the process of customer involvement and approval.

A case study is a powerful tool for showcasing your hard work and the success your customer achieved. But writing a great case study can be difficult if you’ve never done it before or if it’s been a while. This guide will show you how to write an effective case study and provide real-world examples and templates that will keep readers engaged and support your business.

In this article, you’ll learn:

What is a case study?

How to write a case study, case study templates, case study examples, case study tools.

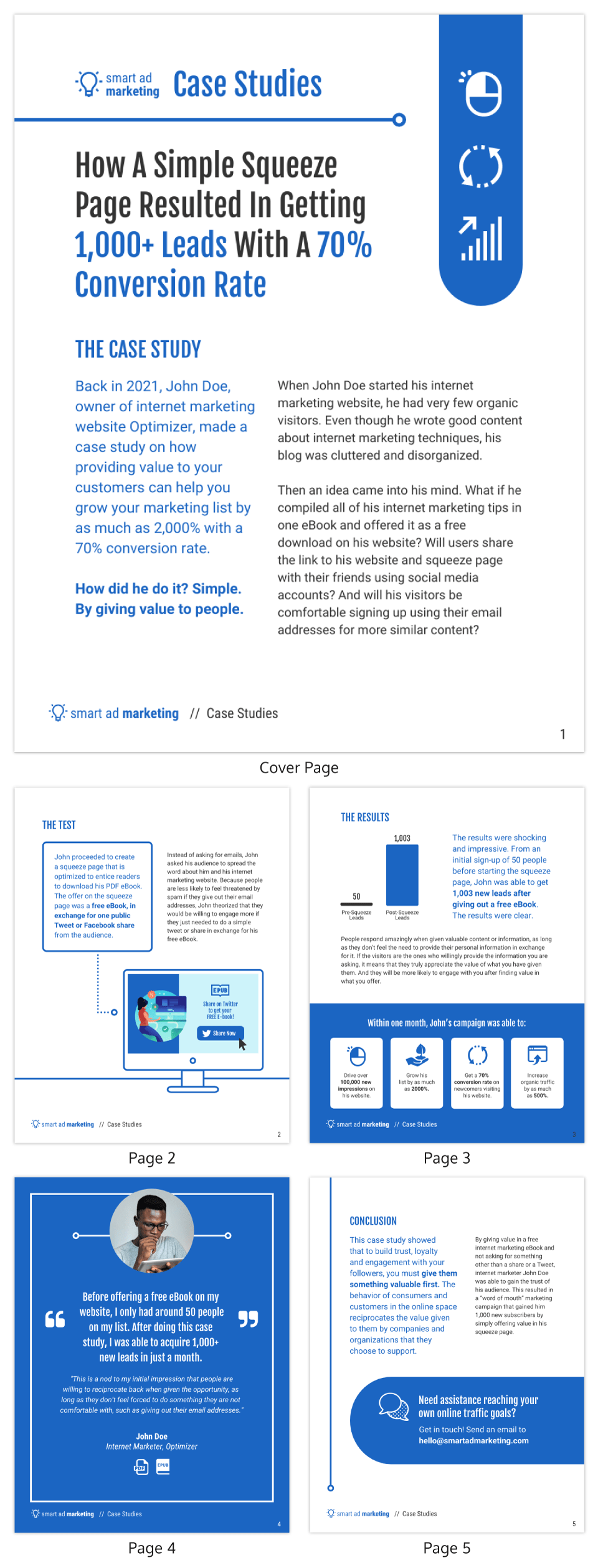

A case study is the detailed story of a customer’s experience with a product or service that demonstrates their success and often includes measurable outcomes. Case studies are used in a range of fields and for various reasons, from business to academic research. They’re especially impactful in marketing as brands work to convince and convert consumers with relatable, real-world stories of actual customer experiences.

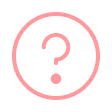

The best case studies tell the story of a customer’s success, including the steps they took, the results they achieved, and the support they received from a brand along the way. To write a great case study, you need to:

- Celebrate the customer and make them — not a product or service — the star of the story.

- Craft the story with specific audiences or target segments in mind so that the story of one customer will be viewed as relatable and actionable for another customer.

- Write copy that is easy to read and engaging so that readers will gain the insights and messages intended.

- Follow a standardized format that includes all of the essentials a potential customer would find interesting and useful.

- Support all of the claims for success made in the story with data in the forms of hard numbers and customer statements.

Case studies are a type of review but more in depth, aiming to show — rather than just tell — the positive experiences that customers have with a brand. Notably, 89% of consumers read reviews before deciding to buy, and 79% view case study content as part of their purchasing process. When it comes to B2B sales, 52% of buyers rank case studies as an important part of their evaluation process.

Telling a brand story through the experience of a tried-and-true customer matters. The story is relatable to potential new customers as they imagine themselves in the shoes of the company or individual featured in the case study. Showcasing previous customers can help new ones see themselves engaging with your brand in the ways that are most meaningful to them.

Besides sharing the perspective of another customer, case studies stand out from other content marketing forms because they are based on evidence. Whether pulling from client testimonials or data-driven results, case studies tend to have more impact on new business because the story contains information that is both objective (data) and subjective (customer experience) — and the brand doesn’t sound too self-promotional.

Case studies are unique in that there’s a fairly standardized format for telling a customer’s story. But that doesn’t mean there isn’t room for creativity. It’s all about making sure that teams are clear on the goals for the case study — along with strategies for supporting content and channels — and understanding how the story fits within the framework of the company’s overall marketing goals.

Here are the basic steps to writing a good case study.

1. Identify your goal

Start by defining exactly who your case study will be designed to help. Case studies are about specific instances where a company works with a customer to achieve a goal. Identify which customers are likely to have these goals, as well as other needs the story should cover to appeal to them.

The answer is often found in one of the buyer personas that have been constructed as part of your larger marketing strategy. This can include anything from new leads generated by the marketing team to long-term customers that are being pressed for cross-sell opportunities. In all of these cases, demonstrating value through a relatable customer success story can be part of the solution to conversion.

2. Choose your client or subject

Who you highlight matters. Case studies tie brands together that might otherwise not cross paths. A writer will want to ensure that the highlighted customer aligns with their own company’s brand identity and offerings. Look for a customer with positive name recognition who has had great success with a product or service and is willing to be an advocate.

The client should also match up with the identified target audience. Whichever company or individual is selected should be a reflection of other potential customers who can see themselves in similar circumstances, having the same problems and possible solutions.

Some of the most compelling case studies feature customers who:

- Switch from one product or service to another while naming competitors that missed the mark.

- Experience measurable results that are relatable to others in a specific industry.

- Represent well-known brands and recognizable names that are likely to compel action.

- Advocate for a product or service as a champion and are well-versed in its advantages.

Whoever or whatever customer is selected, marketers must ensure they have the permission of the company involved before getting started. Some brands have strict review and approval procedures for any official marketing or promotional materials that include their name. Acquiring those approvals in advance will prevent any miscommunication or wasted effort if there is an issue with their legal or compliance teams.

3. Conduct research and compile data

Substantiating the claims made in a case study — either by the marketing team or customers themselves — adds validity to the story. To do this, include data and feedback from the client that defines what success looks like. This can be anything from demonstrating return on investment (ROI) to a specific metric the customer was striving to improve. Case studies should prove how an outcome was achieved and show tangible results that indicate to the customer that your solution is the right one.

This step could also include customer interviews. Make sure that the people being interviewed are key stakeholders in the purchase decision or deployment and use of the product or service that is being highlighted. Content writers should work off a set list of questions prepared in advance. It can be helpful to share these with the interviewees beforehand so they have time to consider and craft their responses. One of the best interview tactics to keep in mind is to ask questions where yes and no are not natural answers. This way, your subject will provide more open-ended responses that produce more meaningful content.

4. Choose the right format

There are a number of different ways to format a case study. Depending on what you hope to achieve, one style will be better than another. However, there are some common elements to include, such as:

- An engaging headline

- A subject and customer introduction

- The unique challenge or challenges the customer faced

- The solution the customer used to solve the problem

- The results achieved

- Data and statistics to back up claims of success

- A strong call to action (CTA) to engage with the vendor

It’s also important to note that while case studies are traditionally written as stories, they don’t have to be in a written format. Some companies choose to get more creative with their case studies and produce multimedia content, depending on their audience and objectives. Case study formats can include traditional print stories, interactive web or social content, data-heavy infographics, professionally shot videos, podcasts, and more.

5. Write your case study

We’ll go into more detail later about how exactly to write a case study, including templates and examples. Generally speaking, though, there are a few things to keep in mind when writing your case study.

- Be clear and concise. Readers want to get to the point of the story quickly and easily, and they’ll be looking to see themselves reflected in the story right from the start.

- Provide a big picture. Always make sure to explain who the client is, their goals, and how they achieved success in a short introduction to engage the reader.

- Construct a clear narrative. Stick to the story from the perspective of the customer and what they needed to solve instead of just listing product features or benefits.

- Leverage graphics. Incorporating infographics, charts, and sidebars can be a more engaging and eye-catching way to share key statistics and data in readable ways.

- Offer the right amount of detail. Most case studies are one or two pages with clear sections that a reader can skim to find the information most important to them.

- Include data to support claims. Show real results — both facts and figures and customer quotes — to demonstrate credibility and prove the solution works.

6. Promote your story

Marketers have a number of options for distribution of a freshly minted case study. Many brands choose to publish case studies on their website and post them on social media. This can help support SEO and organic content strategies while also boosting company credibility and trust as visitors see that other businesses have used the product or service.

Marketers are always looking for quality content they can use for lead generation. Consider offering a case study as gated content behind a form on a landing page or as an offer in an email message. One great way to do this is to summarize the content and tease the full story available for download after the user takes an action.

Sales teams can also leverage case studies, so be sure they are aware that the assets exist once they’re published. Especially when it comes to larger B2B sales, companies often ask for examples of similar customer challenges that have been solved.

Now that you’ve learned a bit about case studies and what they should include, you may be wondering how to start creating great customer story content. Here are a couple of templates you can use to structure your case study.

Template 1 — Challenge-solution-result format

- Start with an engaging title. This should be fewer than 70 characters long for SEO best practices. One of the best ways to approach the title is to include the customer’s name and a hint at the challenge they overcame in the end.

- Create an introduction. Lead with an explanation as to who the customer is, the need they had, and the opportunity they found with a specific product or solution. Writers can also suggest the success the customer experienced with the solution they chose.

- Present the challenge. This should be several paragraphs long and explain the problem the customer faced and the issues they were trying to solve. Details should tie into the company’s products and services naturally. This section needs to be the most relatable to the reader so they can picture themselves in a similar situation.