Home Blog Design Understanding Data Presentations (Guide + Examples)

Understanding Data Presentations (Guide + Examples)

In this age of overwhelming information, the skill to effectively convey data has become extremely valuable. Initiating a discussion on data presentation types involves thoughtful consideration of the nature of your data and the message you aim to convey. Different types of visualizations serve distinct purposes. Whether you’re dealing with how to develop a report or simply trying to communicate complex information, how you present data influences how well your audience understands and engages with it. This extensive guide leads you through the different ways of data presentation.

Table of Contents

What is a Data Presentation?

What should a data presentation include, line graphs, treemap chart, scatter plot, how to choose a data presentation type, recommended data presentation templates, common mistakes done in data presentation.

A data presentation is a slide deck that aims to disclose quantitative information to an audience through the use of visual formats and narrative techniques derived from data analysis, making complex data understandable and actionable. This process requires a series of tools, such as charts, graphs, tables, infographics, dashboards, and so on, supported by concise textual explanations to improve understanding and boost retention rate.

Data presentations require us to cull data in a format that allows the presenter to highlight trends, patterns, and insights so that the audience can act upon the shared information. In a few words, the goal of data presentations is to enable viewers to grasp complicated concepts or trends quickly, facilitating informed decision-making or deeper analysis.

Data presentations go beyond the mere usage of graphical elements. Seasoned presenters encompass visuals with the art of data storytelling , so the speech skillfully connects the points through a narrative that resonates with the audience. Depending on the purpose – inspire, persuade, inform, support decision-making processes, etc. – is the data presentation format that is better suited to help us in this journey.

To nail your upcoming data presentation, ensure to count with the following elements:

- Clear Objectives: Understand the intent of your presentation before selecting the graphical layout and metaphors to make content easier to grasp.

- Engaging introduction: Use a powerful hook from the get-go. For instance, you can ask a big question or present a problem that your data will answer. Take a look at our guide on how to start a presentation for tips & insights.

- Structured Narrative: Your data presentation must tell a coherent story. This means a beginning where you present the context, a middle section in which you present the data, and an ending that uses a call-to-action. Check our guide on presentation structure for further information.

- Visual Elements: These are the charts, graphs, and other elements of visual communication we ought to use to present data. This article will cover one by one the different types of data representation methods we can use, and provide further guidance on choosing between them.

- Insights and Analysis: This is not just showcasing a graph and letting people get an idea about it. A proper data presentation includes the interpretation of that data, the reason why it’s included, and why it matters to your research.

- Conclusion & CTA: Ending your presentation with a call to action is necessary. Whether you intend to wow your audience into acquiring your services, inspire them to change the world, or whatever the purpose of your presentation, there must be a stage in which you convey all that you shared and show the path to staying in touch. Plan ahead whether you want to use a thank-you slide, a video presentation, or which method is apt and tailored to the kind of presentation you deliver.

- Q&A Session: After your speech is concluded, allocate 3-5 minutes for the audience to raise any questions about the information you disclosed. This is an extra chance to establish your authority on the topic. Check our guide on questions and answer sessions in presentations here.

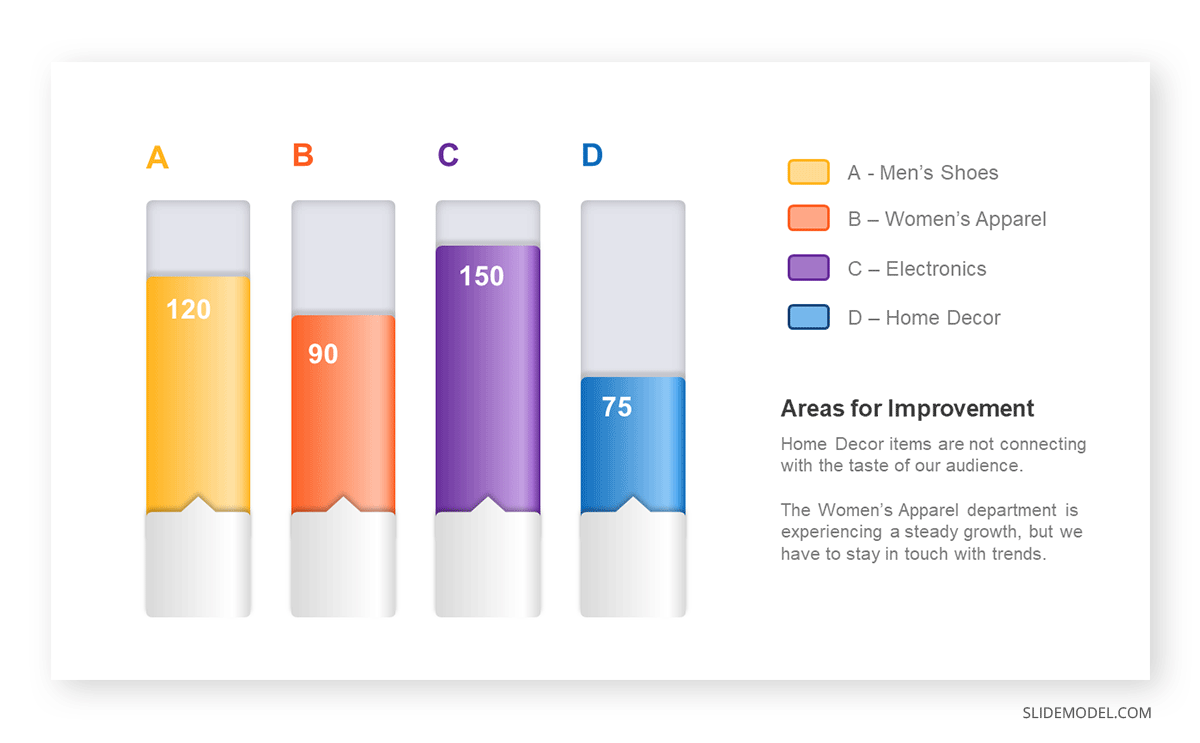

Bar charts are a graphical representation of data using rectangular bars to show quantities or frequencies in an established category. They make it easy for readers to spot patterns or trends. Bar charts can be horizontal or vertical, although the vertical format is commonly known as a column chart. They display categorical, discrete, or continuous variables grouped in class intervals [1] . They include an axis and a set of labeled bars horizontally or vertically. These bars represent the frequencies of variable values or the values themselves. Numbers on the y-axis of a vertical bar chart or the x-axis of a horizontal bar chart are called the scale.

Real-Life Application of Bar Charts

Let’s say a sales manager is presenting sales to their audience. Using a bar chart, he follows these steps.

Step 1: Selecting Data

The first step is to identify the specific data you will present to your audience.

The sales manager has highlighted these products for the presentation.

- Product A: Men’s Shoes

- Product B: Women’s Apparel

- Product C: Electronics

- Product D: Home Decor

Step 2: Choosing Orientation

Opt for a vertical layout for simplicity. Vertical bar charts help compare different categories in case there are not too many categories [1] . They can also help show different trends. A vertical bar chart is used where each bar represents one of the four chosen products. After plotting the data, it is seen that the height of each bar directly represents the sales performance of the respective product.

It is visible that the tallest bar (Electronics – Product C) is showing the highest sales. However, the shorter bars (Women’s Apparel – Product B and Home Decor – Product D) need attention. It indicates areas that require further analysis or strategies for improvement.

Step 3: Colorful Insights

Different colors are used to differentiate each product. It is essential to show a color-coded chart where the audience can distinguish between products.

- Men’s Shoes (Product A): Yellow

- Women’s Apparel (Product B): Orange

- Electronics (Product C): Violet

- Home Decor (Product D): Blue

Bar charts are straightforward and easily understandable for presenting data. They are versatile when comparing products or any categorical data [2] . Bar charts adapt seamlessly to retail scenarios. Despite that, bar charts have a few shortcomings. They cannot illustrate data trends over time. Besides, overloading the chart with numerous products can lead to visual clutter, diminishing its effectiveness.

For more information, check our collection of bar chart templates for PowerPoint .

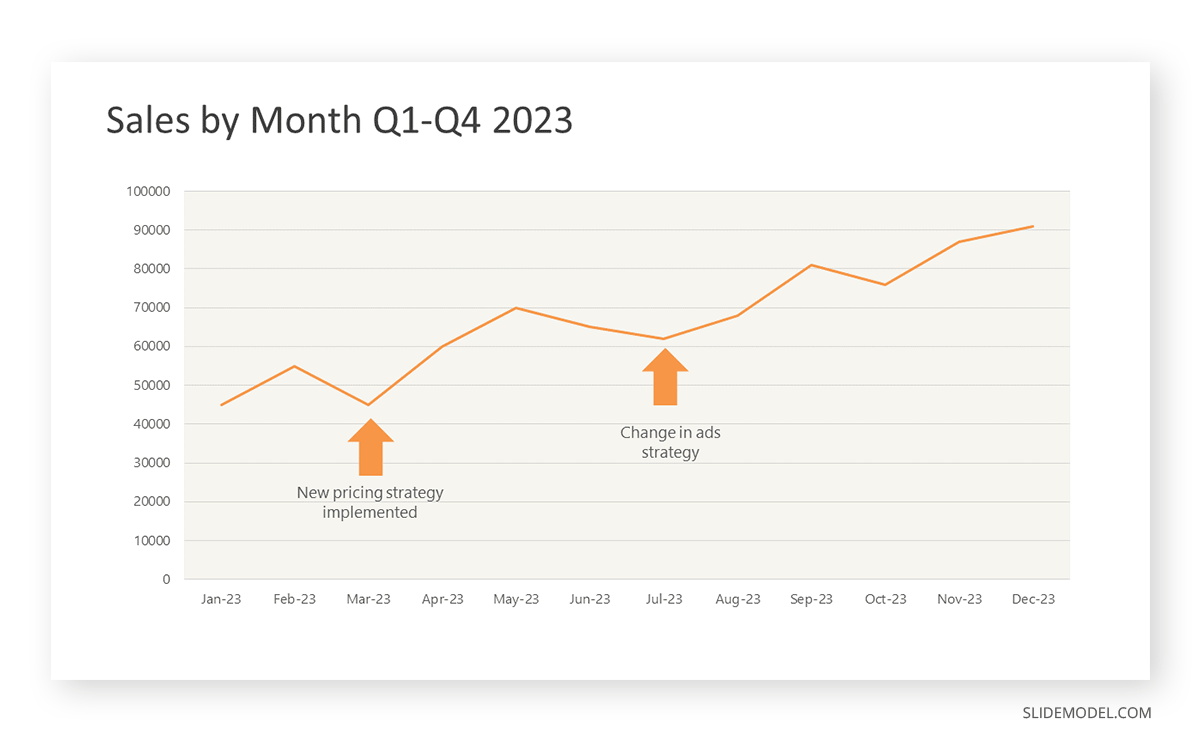

Line graphs help illustrate data trends, progressions, or fluctuations by connecting a series of data points called ‘markers’ with straight line segments. This provides a straightforward representation of how values change [5] . Their versatility makes them invaluable for scenarios requiring a visual understanding of continuous data. In addition, line graphs are also useful for comparing multiple datasets over the same timeline. Using multiple line graphs allows us to compare more than one data set. They simplify complex information so the audience can quickly grasp the ups and downs of values. From tracking stock prices to analyzing experimental results, you can use line graphs to show how data changes over a continuous timeline. They show trends with simplicity and clarity.

Real-life Application of Line Graphs

To understand line graphs thoroughly, we will use a real case. Imagine you’re a financial analyst presenting a tech company’s monthly sales for a licensed product over the past year. Investors want insights into sales behavior by month, how market trends may have influenced sales performance and reception to the new pricing strategy. To present data via a line graph, you will complete these steps.

First, you need to gather the data. In this case, your data will be the sales numbers. For example:

- January: $45,000

- February: $55,000

- March: $45,000

- April: $60,000

- May: $ 70,000

- June: $65,000

- July: $62,000

- August: $68,000

- September: $81,000

- October: $76,000

- November: $87,000

- December: $91,000

After choosing the data, the next step is to select the orientation. Like bar charts, you can use vertical or horizontal line graphs. However, we want to keep this simple, so we will keep the timeline (x-axis) horizontal while the sales numbers (y-axis) vertical.

Step 3: Connecting Trends

After adding the data to your preferred software, you will plot a line graph. In the graph, each month’s sales are represented by data points connected by a line.

Step 4: Adding Clarity with Color

If there are multiple lines, you can also add colors to highlight each one, making it easier to follow.

Line graphs excel at visually presenting trends over time. These presentation aids identify patterns, like upward or downward trends. However, too many data points can clutter the graph, making it harder to interpret. Line graphs work best with continuous data but are not suitable for categories.

For more information, check our collection of line chart templates for PowerPoint and our article about how to make a presentation graph .

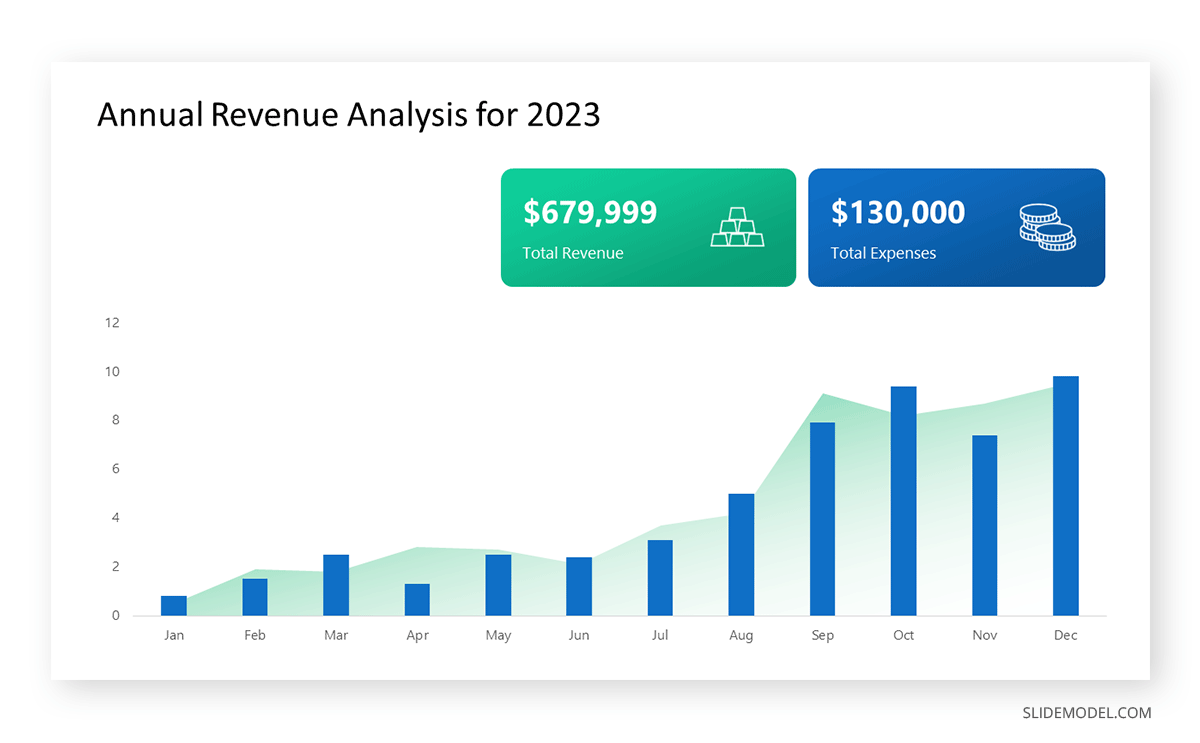

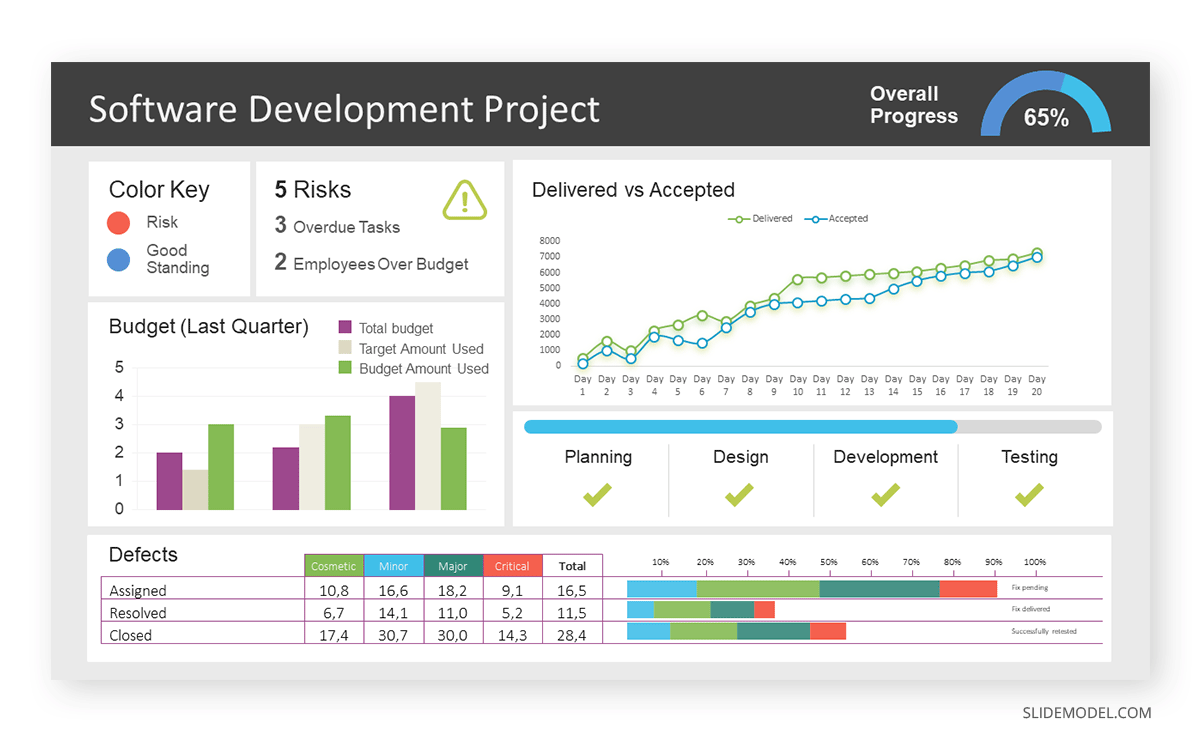

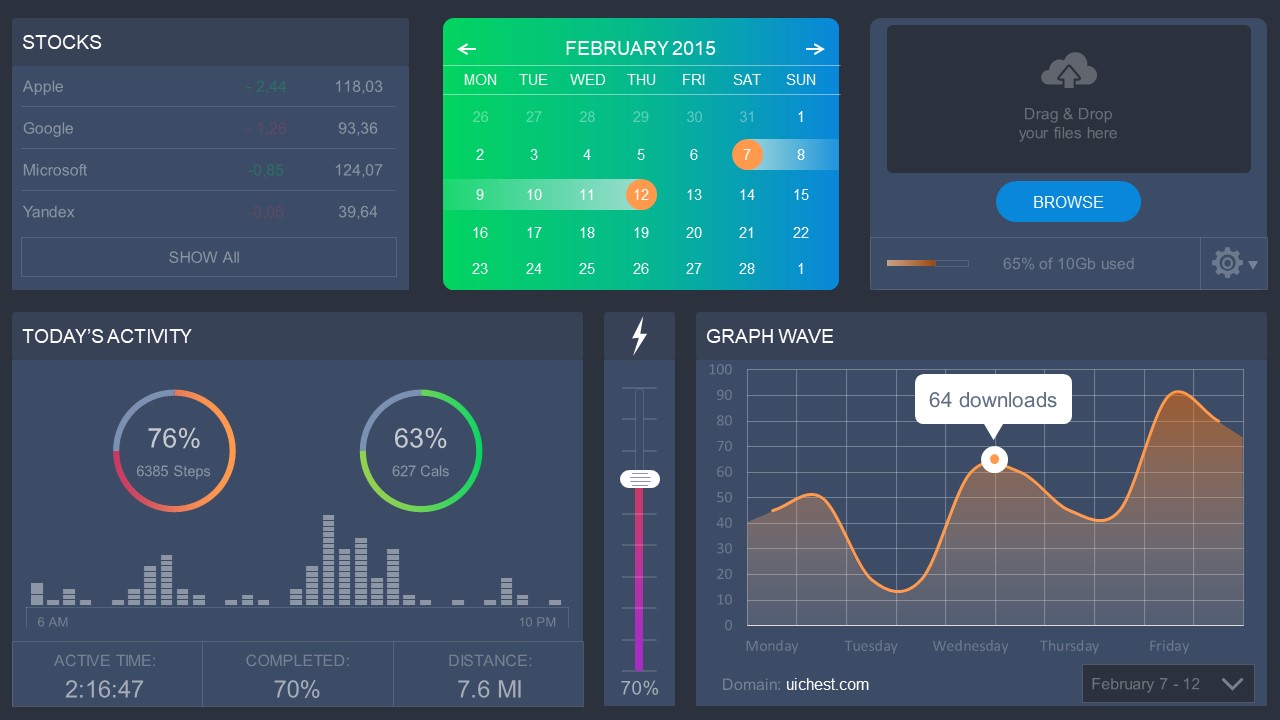

A data dashboard is a visual tool for analyzing information. Different graphs, charts, and tables are consolidated in a layout to showcase the information required to achieve one or more objectives. Dashboards help quickly see Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). You don’t make new visuals in the dashboard; instead, you use it to display visuals you’ve already made in worksheets [3] .

Keeping the number of visuals on a dashboard to three or four is recommended. Adding too many can make it hard to see the main points [4]. Dashboards can be used for business analytics to analyze sales, revenue, and marketing metrics at a time. They are also used in the manufacturing industry, as they allow users to grasp the entire production scenario at the moment while tracking the core KPIs for each line.

Real-Life Application of a Dashboard

Consider a project manager presenting a software development project’s progress to a tech company’s leadership team. He follows the following steps.

Step 1: Defining Key Metrics

To effectively communicate the project’s status, identify key metrics such as completion status, budget, and bug resolution rates. Then, choose measurable metrics aligned with project objectives.

Step 2: Choosing Visualization Widgets

After finalizing the data, presentation aids that align with each metric are selected. For this project, the project manager chooses a progress bar for the completion status and uses bar charts for budget allocation. Likewise, he implements line charts for bug resolution rates.

Step 3: Dashboard Layout

Key metrics are prominently placed in the dashboard for easy visibility, and the manager ensures that it appears clean and organized.

Dashboards provide a comprehensive view of key project metrics. Users can interact with data, customize views, and drill down for detailed analysis. However, creating an effective dashboard requires careful planning to avoid clutter. Besides, dashboards rely on the availability and accuracy of underlying data sources.

For more information, check our article on how to design a dashboard presentation , and discover our collection of dashboard PowerPoint templates .

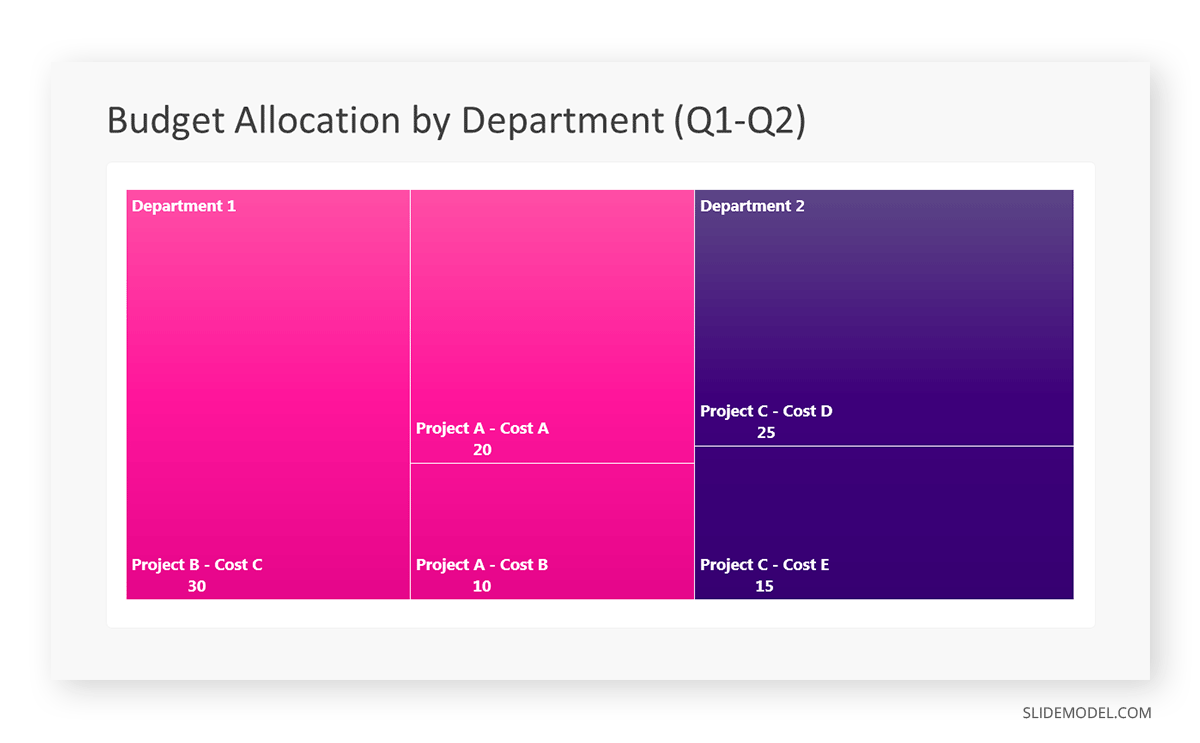

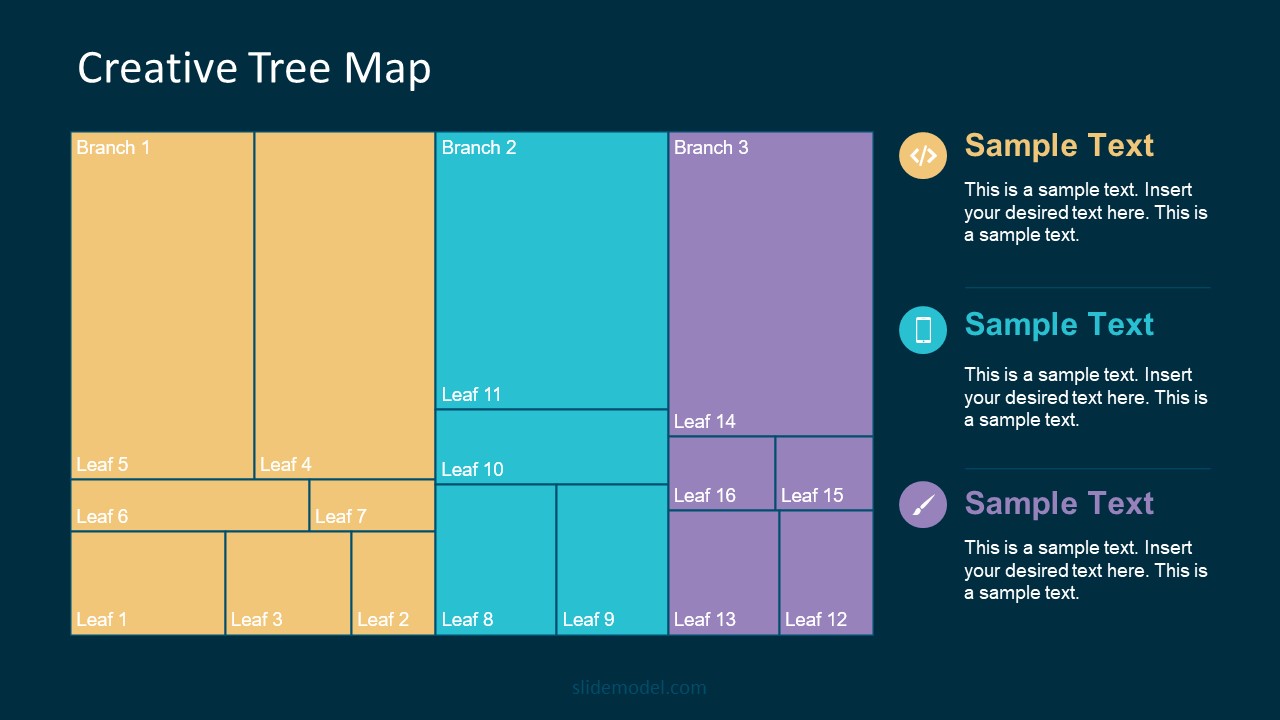

Treemap charts represent hierarchical data structured in a series of nested rectangles [6] . As each branch of the ‘tree’ is given a rectangle, smaller tiles can be seen representing sub-branches, meaning elements on a lower hierarchical level than the parent rectangle. Each one of those rectangular nodes is built by representing an area proportional to the specified data dimension.

Treemaps are useful for visualizing large datasets in compact space. It is easy to identify patterns, such as which categories are dominant. Common applications of the treemap chart are seen in the IT industry, such as resource allocation, disk space management, website analytics, etc. Also, they can be used in multiple industries like healthcare data analysis, market share across different product categories, or even in finance to visualize portfolios.

Real-Life Application of a Treemap Chart

Let’s consider a financial scenario where a financial team wants to represent the budget allocation of a company. There is a hierarchy in the process, so it is helpful to use a treemap chart. In the chart, the top-level rectangle could represent the total budget, and it would be subdivided into smaller rectangles, each denoting a specific department. Further subdivisions within these smaller rectangles might represent individual projects or cost categories.

Step 1: Define Your Data Hierarchy

While presenting data on the budget allocation, start by outlining the hierarchical structure. The sequence will be like the overall budget at the top, followed by departments, projects within each department, and finally, individual cost categories for each project.

- Top-level rectangle: Total Budget

- Second-level rectangles: Departments (Engineering, Marketing, Sales)

- Third-level rectangles: Projects within each department

- Fourth-level rectangles: Cost categories for each project (Personnel, Marketing Expenses, Equipment)

Step 2: Choose a Suitable Tool

It’s time to select a data visualization tool supporting Treemaps. Popular choices include Tableau, Microsoft Power BI, PowerPoint, or even coding with libraries like D3.js. It is vital to ensure that the chosen tool provides customization options for colors, labels, and hierarchical structures.

Here, the team uses PowerPoint for this guide because of its user-friendly interface and robust Treemap capabilities.

Step 3: Make a Treemap Chart with PowerPoint

After opening the PowerPoint presentation, they chose “SmartArt” to form the chart. The SmartArt Graphic window has a “Hierarchy” category on the left. Here, you will see multiple options. You can choose any layout that resembles a Treemap. The “Table Hierarchy” or “Organization Chart” options can be adapted. The team selects the Table Hierarchy as it looks close to a Treemap.

Step 5: Input Your Data

After that, a new window will open with a basic structure. They add the data one by one by clicking on the text boxes. They start with the top-level rectangle, representing the total budget.

Step 6: Customize the Treemap

By clicking on each shape, they customize its color, size, and label. At the same time, they can adjust the font size, style, and color of labels by using the options in the “Format” tab in PowerPoint. Using different colors for each level enhances the visual difference.

Treemaps excel at illustrating hierarchical structures. These charts make it easy to understand relationships and dependencies. They efficiently use space, compactly displaying a large amount of data, reducing the need for excessive scrolling or navigation. Additionally, using colors enhances the understanding of data by representing different variables or categories.

In some cases, treemaps might become complex, especially with deep hierarchies. It becomes challenging for some users to interpret the chart. At the same time, displaying detailed information within each rectangle might be constrained by space. It potentially limits the amount of data that can be shown clearly. Without proper labeling and color coding, there’s a risk of misinterpretation.

A heatmap is a data visualization tool that uses color coding to represent values across a two-dimensional surface. In these, colors replace numbers to indicate the magnitude of each cell. This color-shaded matrix display is valuable for summarizing and understanding data sets with a glance [7] . The intensity of the color corresponds to the value it represents, making it easy to identify patterns, trends, and variations in the data.

As a tool, heatmaps help businesses analyze website interactions, revealing user behavior patterns and preferences to enhance overall user experience. In addition, companies use heatmaps to assess content engagement, identifying popular sections and areas of improvement for more effective communication. They excel at highlighting patterns and trends in large datasets, making it easy to identify areas of interest.

We can implement heatmaps to express multiple data types, such as numerical values, percentages, or even categorical data. Heatmaps help us easily spot areas with lots of activity, making them helpful in figuring out clusters [8] . When making these maps, it is important to pick colors carefully. The colors need to show the differences between groups or levels of something. And it is good to use colors that people with colorblindness can easily see.

Check our detailed guide on how to create a heatmap here. Also discover our collection of heatmap PowerPoint templates .

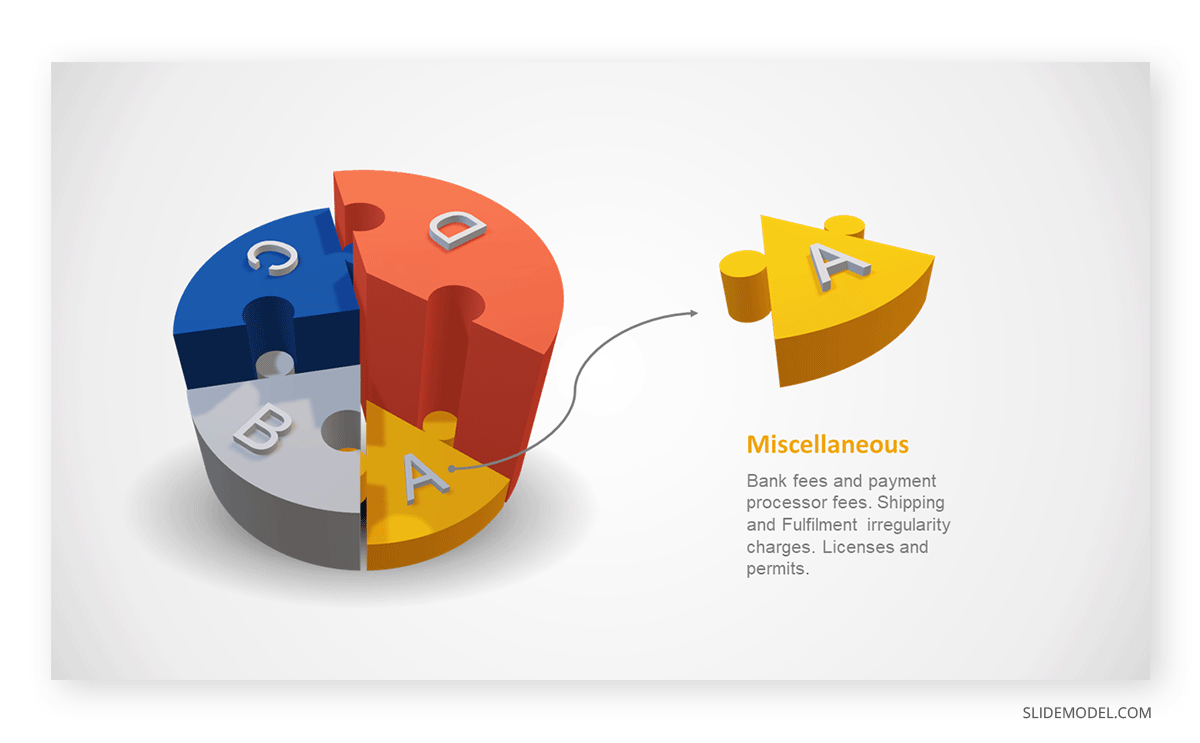

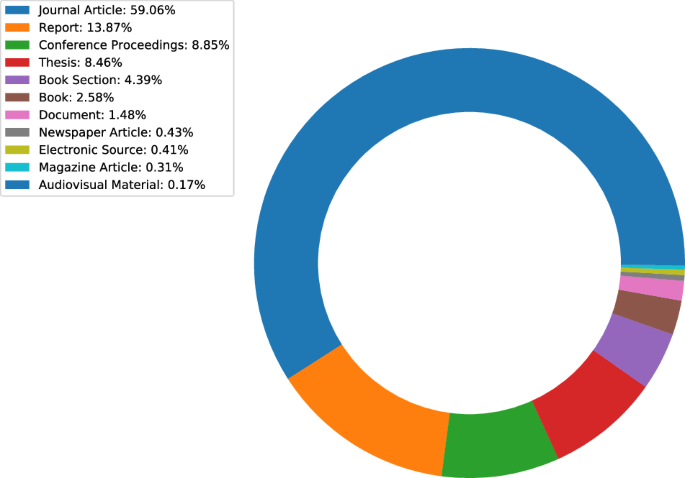

Pie charts are circular statistical graphics divided into slices to illustrate numerical proportions. Each slice represents a proportionate part of the whole, making it easy to visualize the contribution of each component to the total.

The size of the pie charts is influenced by the value of data points within each pie. The total of all data points in a pie determines its size. The pie with the highest data points appears as the largest, whereas the others are proportionally smaller. However, you can present all pies of the same size if proportional representation is not required [9] . Sometimes, pie charts are difficult to read, or additional information is required. A variation of this tool can be used instead, known as the donut chart , which has the same structure but a blank center, creating a ring shape. Presenters can add extra information, and the ring shape helps to declutter the graph.

Pie charts are used in business to show percentage distribution, compare relative sizes of categories, or present straightforward data sets where visualizing ratios is essential.

Real-Life Application of Pie Charts

Consider a scenario where you want to represent the distribution of the data. Each slice of the pie chart would represent a different category, and the size of each slice would indicate the percentage of the total portion allocated to that category.

Step 1: Define Your Data Structure

Imagine you are presenting the distribution of a project budget among different expense categories.

- Column A: Expense Categories (Personnel, Equipment, Marketing, Miscellaneous)

- Column B: Budget Amounts ($40,000, $30,000, $20,000, $10,000) Column B represents the values of your categories in Column A.

Step 2: Insert a Pie Chart

Using any of the accessible tools, you can create a pie chart. The most convenient tools for forming a pie chart in a presentation are presentation tools such as PowerPoint or Google Slides. You will notice that the pie chart assigns each expense category a percentage of the total budget by dividing it by the total budget.

For instance:

- Personnel: $40,000 / ($40,000 + $30,000 + $20,000 + $10,000) = 40%

- Equipment: $30,000 / ($40,000 + $30,000 + $20,000 + $10,000) = 30%

- Marketing: $20,000 / ($40,000 + $30,000 + $20,000 + $10,000) = 20%

- Miscellaneous: $10,000 / ($40,000 + $30,000 + $20,000 + $10,000) = 10%

You can make a chart out of this or just pull out the pie chart from the data.

3D pie charts and 3D donut charts are quite popular among the audience. They stand out as visual elements in any presentation slide, so let’s take a look at how our pie chart example would look in 3D pie chart format.

Step 03: Results Interpretation

The pie chart visually illustrates the distribution of the project budget among different expense categories. Personnel constitutes the largest portion at 40%, followed by equipment at 30%, marketing at 20%, and miscellaneous at 10%. This breakdown provides a clear overview of where the project funds are allocated, which helps in informed decision-making and resource management. It is evident that personnel are a significant investment, emphasizing their importance in the overall project budget.

Pie charts provide a straightforward way to represent proportions and percentages. They are easy to understand, even for individuals with limited data analysis experience. These charts work well for small datasets with a limited number of categories.

However, a pie chart can become cluttered and less effective in situations with many categories. Accurate interpretation may be challenging, especially when dealing with slight differences in slice sizes. In addition, these charts are static and do not effectively convey trends over time.

For more information, check our collection of pie chart templates for PowerPoint .

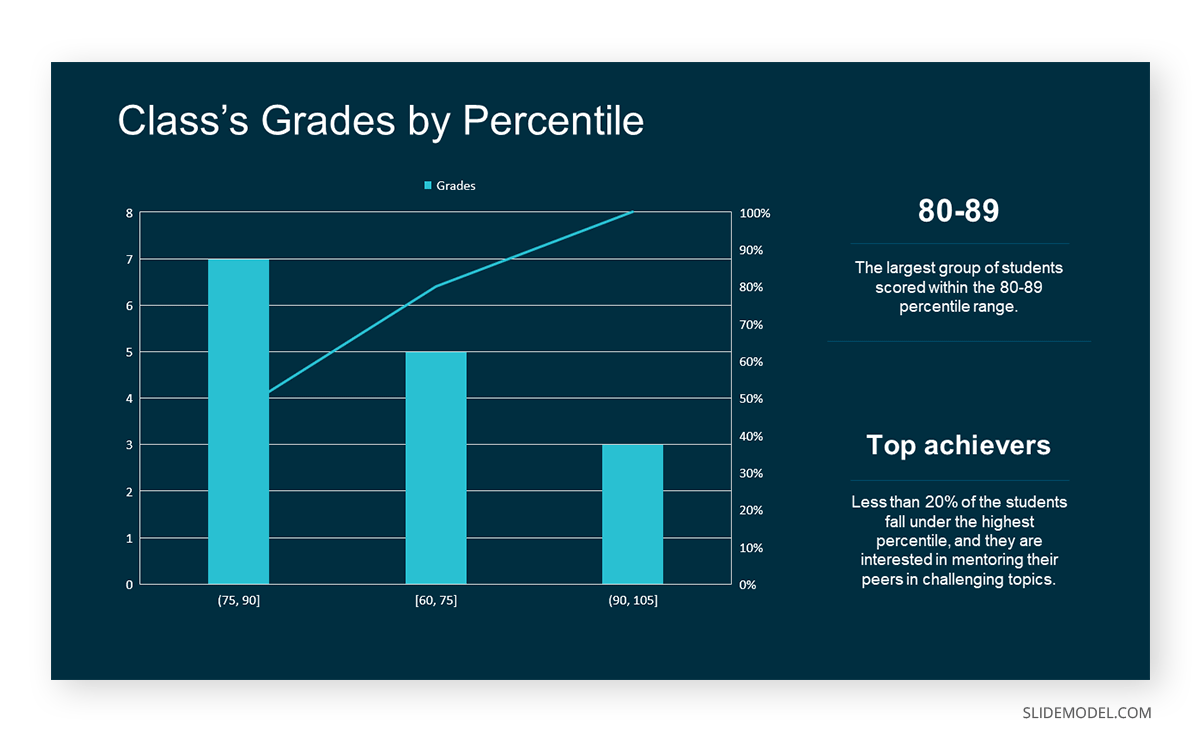

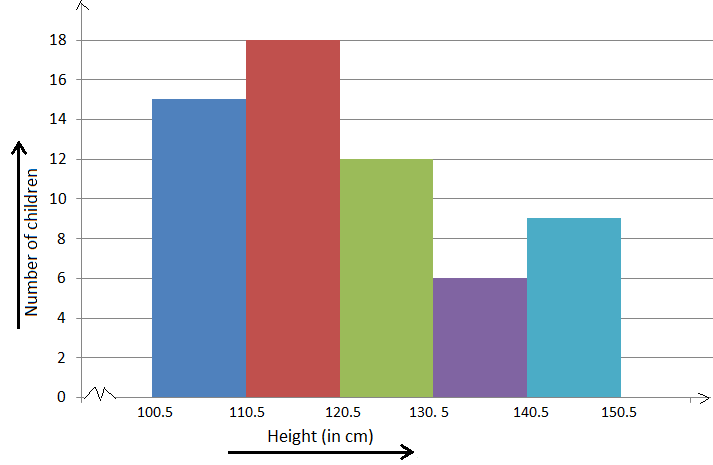

Histograms present the distribution of numerical variables. Unlike a bar chart that records each unique response separately, histograms organize numeric responses into bins and show the frequency of reactions within each bin [10] . The x-axis of a histogram shows the range of values for a numeric variable. At the same time, the y-axis indicates the relative frequencies (percentage of the total counts) for that range of values.

Whenever you want to understand the distribution of your data, check which values are more common, or identify outliers, histograms are your go-to. Think of them as a spotlight on the story your data is telling. A histogram can provide a quick and insightful overview if you’re curious about exam scores, sales figures, or any numerical data distribution.

Real-Life Application of a Histogram

In the histogram data analysis presentation example, imagine an instructor analyzing a class’s grades to identify the most common score range. A histogram could effectively display the distribution. It will show whether most students scored in the average range or if there are significant outliers.

Step 1: Gather Data

He begins by gathering the data. The scores of each student in class are gathered to analyze exam scores.

After arranging the scores in ascending order, bin ranges are set.

Step 2: Define Bins

Bins are like categories that group similar values. Think of them as buckets that organize your data. The presenter decides how wide each bin should be based on the range of the values. For instance, the instructor sets the bin ranges based on score intervals: 60-69, 70-79, 80-89, and 90-100.

Step 3: Count Frequency

Now, he counts how many data points fall into each bin. This step is crucial because it tells you how often specific ranges of values occur. The result is the frequency distribution, showing the occurrences of each group.

Here, the instructor counts the number of students in each category.

- 60-69: 1 student (Kate)

- 70-79: 4 students (David, Emma, Grace, Jack)

- 80-89: 7 students (Alice, Bob, Frank, Isabel, Liam, Mia, Noah)

- 90-100: 3 students (Clara, Henry, Olivia)

Step 4: Create the Histogram

It’s time to turn the data into a visual representation. Draw a bar for each bin on a graph. The width of the bar should correspond to the range of the bin, and the height should correspond to the frequency. To make your histogram understandable, label the X and Y axes.

In this case, the X-axis should represent the bins (e.g., test score ranges), and the Y-axis represents the frequency.

The histogram of the class grades reveals insightful patterns in the distribution. Most students, with seven students, fall within the 80-89 score range. The histogram provides a clear visualization of the class’s performance. It showcases a concentration of grades in the upper-middle range with few outliers at both ends. This analysis helps in understanding the overall academic standing of the class. It also identifies the areas for potential improvement or recognition.

Thus, histograms provide a clear visual representation of data distribution. They are easy to interpret, even for those without a statistical background. They apply to various types of data, including continuous and discrete variables. One weak point is that histograms do not capture detailed patterns in students’ data, with seven compared to other visualization methods.

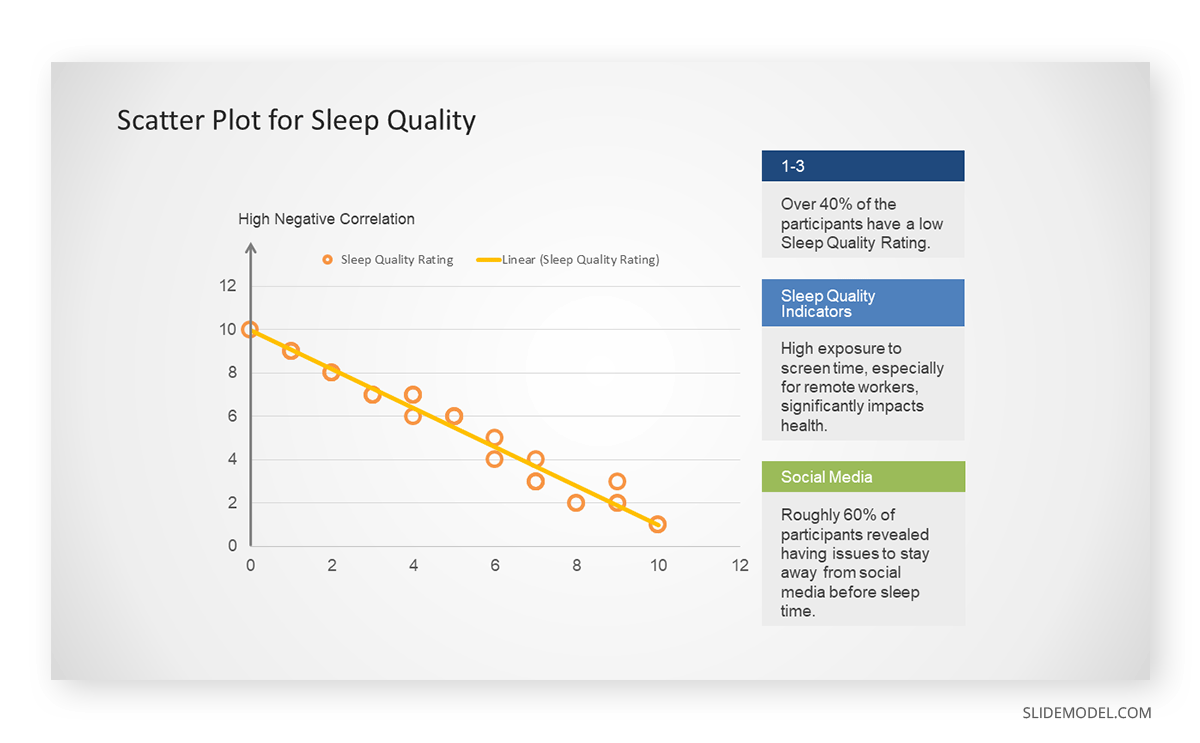

A scatter plot is a graphical representation of the relationship between two variables. It consists of individual data points on a two-dimensional plane. This plane plots one variable on the x-axis and the other on the y-axis. Each point represents a unique observation. It visualizes patterns, trends, or correlations between the two variables.

Scatter plots are also effective in revealing the strength and direction of relationships. They identify outliers and assess the overall distribution of data points. The points’ dispersion and clustering reflect the relationship’s nature, whether it is positive, negative, or lacks a discernible pattern. In business, scatter plots assess relationships between variables such as marketing cost and sales revenue. They help present data correlations and decision-making.

Real-Life Application of Scatter Plot

A group of scientists is conducting a study on the relationship between daily hours of screen time and sleep quality. After reviewing the data, they managed to create this table to help them build a scatter plot graph:

In the provided example, the x-axis represents Daily Hours of Screen Time, and the y-axis represents the Sleep Quality Rating.

The scientists observe a negative correlation between the amount of screen time and the quality of sleep. This is consistent with their hypothesis that blue light, especially before bedtime, has a significant impact on sleep quality and metabolic processes.

There are a few things to remember when using a scatter plot. Even when a scatter diagram indicates a relationship, it doesn’t mean one variable affects the other. A third factor can influence both variables. The more the plot resembles a straight line, the stronger the relationship is perceived [11] . If it suggests no ties, the observed pattern might be due to random fluctuations in data. When the scatter diagram depicts no correlation, whether the data might be stratified is worth considering.

Choosing the appropriate data presentation type is crucial when making a presentation . Understanding the nature of your data and the message you intend to convey will guide this selection process. For instance, when showcasing quantitative relationships, scatter plots become instrumental in revealing correlations between variables. If the focus is on emphasizing parts of a whole, pie charts offer a concise display of proportions. Histograms, on the other hand, prove valuable for illustrating distributions and frequency patterns.

Bar charts provide a clear visual comparison of different categories. Likewise, line charts excel in showcasing trends over time, while tables are ideal for detailed data examination. Starting a presentation on data presentation types involves evaluating the specific information you want to communicate and selecting the format that aligns with your message. This ensures clarity and resonance with your audience from the beginning of your presentation.

1. Fact Sheet Dashboard for Data Presentation

Convey all the data you need to present in this one-pager format, an ideal solution tailored for users looking for presentation aids. Global maps, donut chats, column graphs, and text neatly arranged in a clean layout presented in light and dark themes.

Use This Template

2. 3D Column Chart Infographic PPT Template

Represent column charts in a highly visual 3D format with this PPT template. A creative way to present data, this template is entirely editable, and we can craft either a one-page infographic or a series of slides explaining what we intend to disclose point by point.

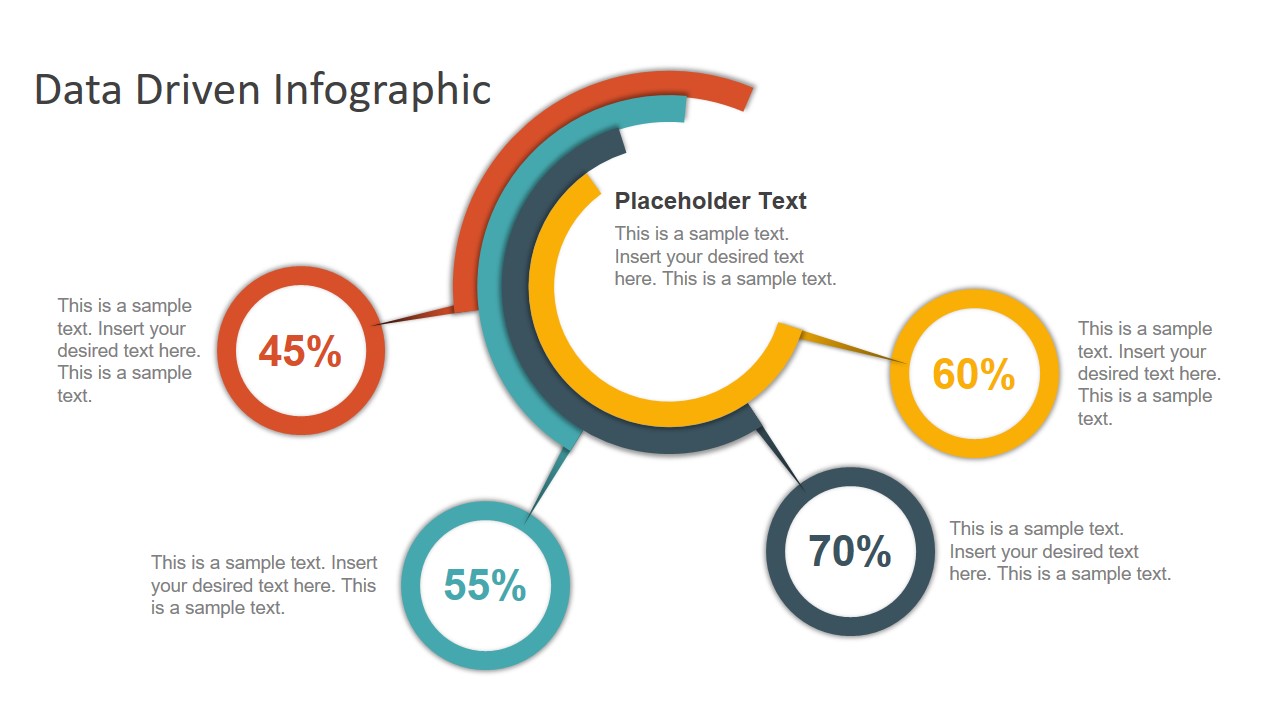

3. Data Circles Infographic PowerPoint Template

An alternative to the pie chart and donut chart diagrams, this template features a series of curved shapes with bubble callouts as ways of presenting data. Expand the information for each arch in the text placeholder areas.

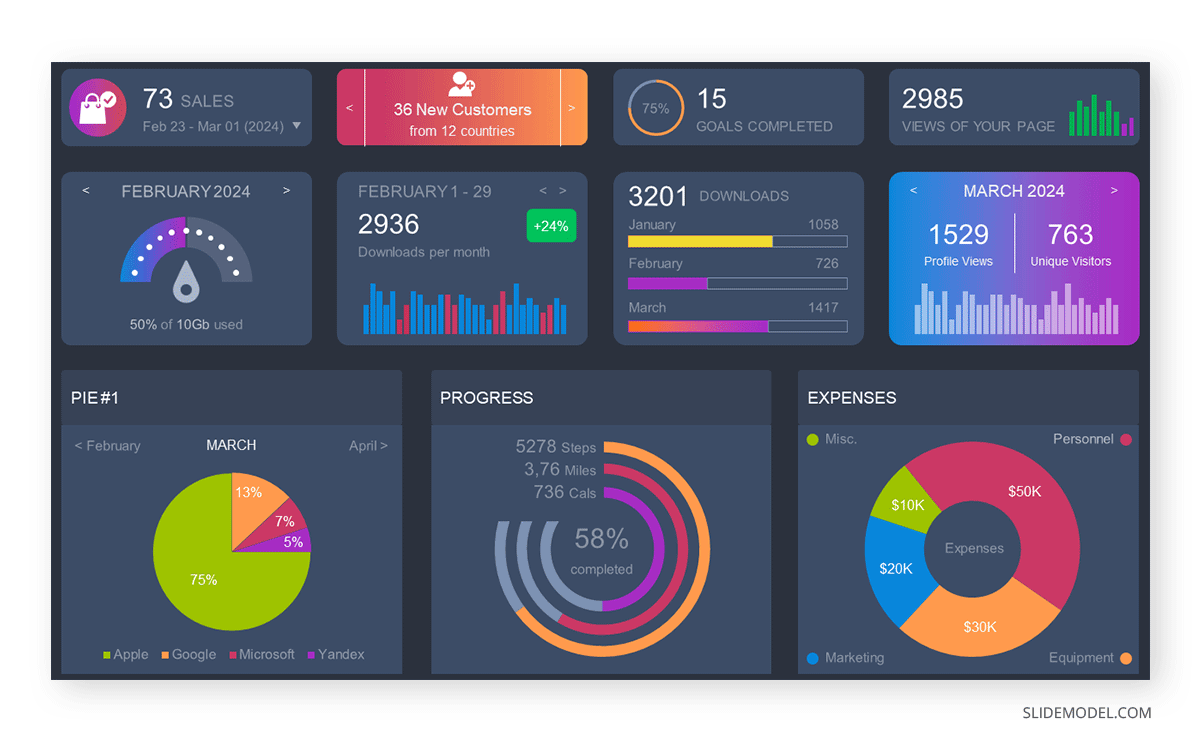

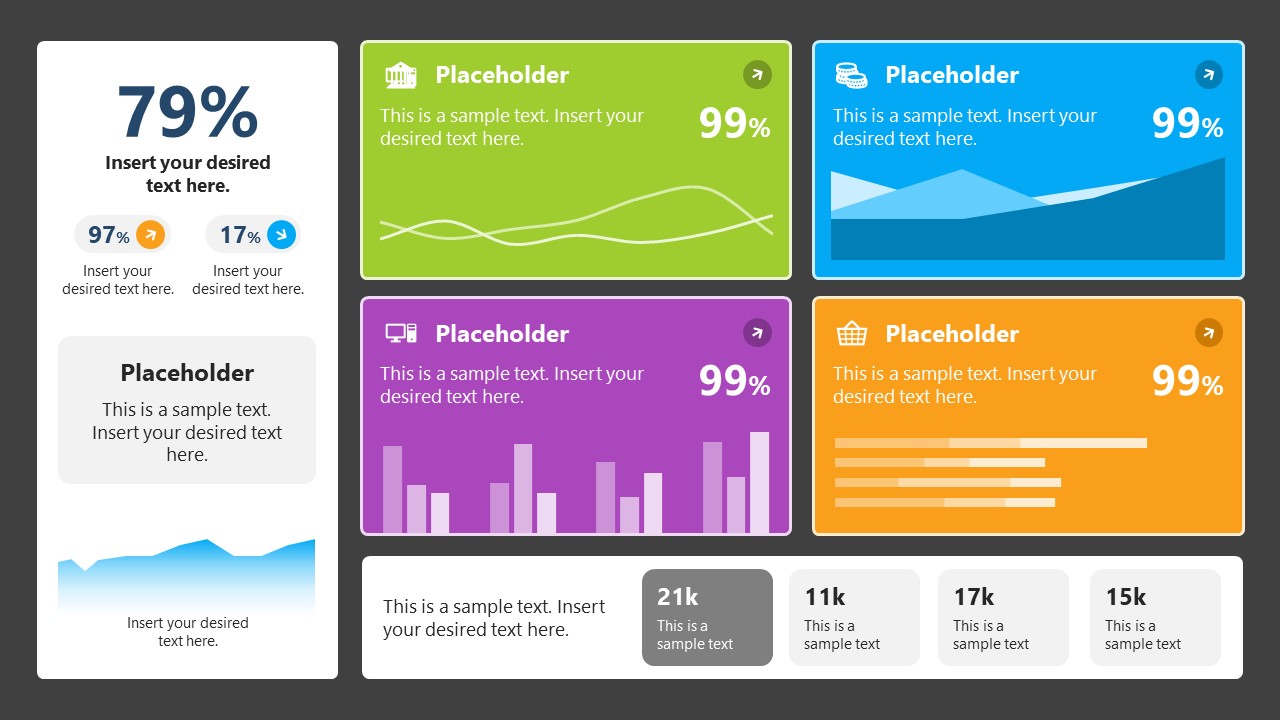

4. Colorful Metrics Dashboard for Data Presentation

This versatile dashboard template helps us in the presentation of the data by offering several graphs and methods to convert numbers into graphics. Implement it for e-commerce projects, financial projections, project development, and more.

5. Animated Data Presentation Tools for PowerPoint & Google Slides

A slide deck filled with most of the tools mentioned in this article, from bar charts, column charts, treemap graphs, pie charts, histogram, etc. Animated effects make each slide look dynamic when sharing data with stakeholders.

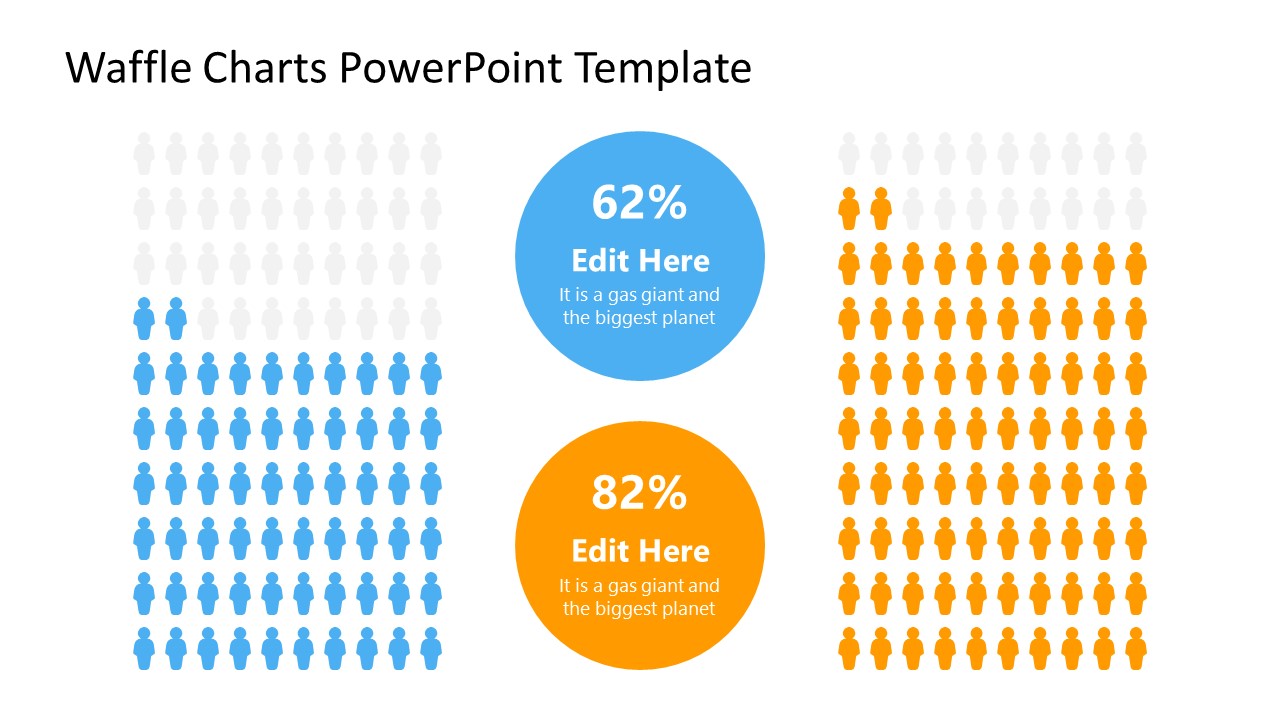

6. Statistics Waffle Charts PPT Template for Data Presentations

This PPT template helps us how to present data beyond the typical pie chart representation. It is widely used for demographics, so it’s a great fit for marketing teams, data science professionals, HR personnel, and more.

7. Data Presentation Dashboard Template for Google Slides

A compendium of tools in dashboard format featuring line graphs, bar charts, column charts, and neatly arranged placeholder text areas.

8. Weather Dashboard for Data Presentation

Share weather data for agricultural presentation topics, environmental studies, or any kind of presentation that requires a highly visual layout for weather forecasting on a single day. Two color themes are available.

9. Social Media Marketing Dashboard Data Presentation Template

Intended for marketing professionals, this dashboard template for data presentation is a tool for presenting data analytics from social media channels. Two slide layouts featuring line graphs and column charts.

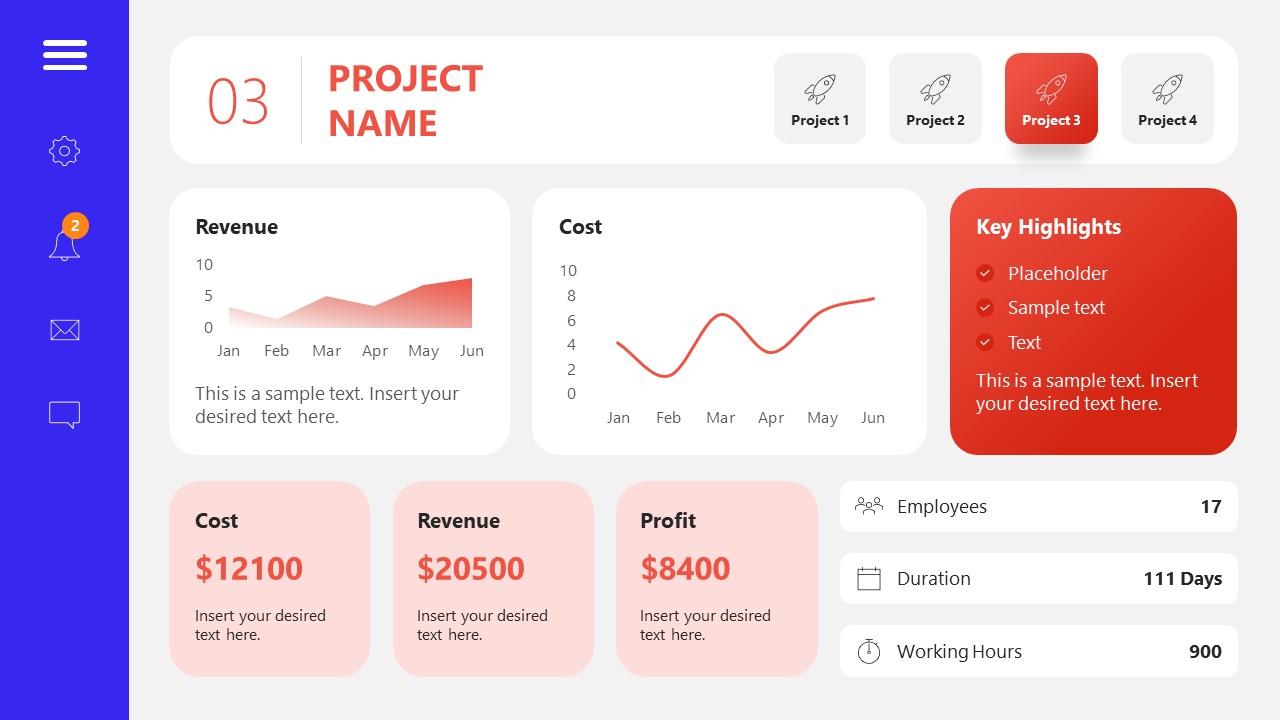

10. Project Management Summary Dashboard Template

A tool crafted for project managers to deliver highly visual reports on a project’s completion, the profits it delivered for the company, and expenses/time required to execute it. 4 different color layouts are available.

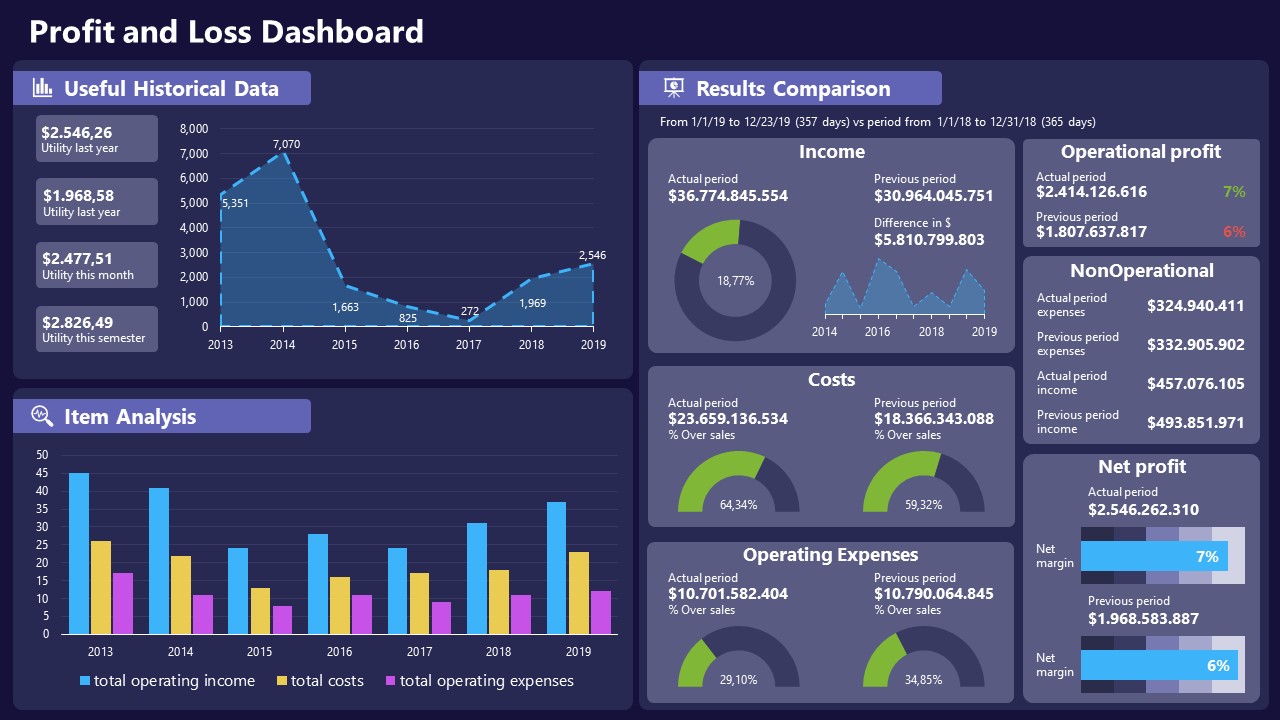

11. Profit & Loss Dashboard for PowerPoint and Google Slides

A must-have for finance professionals. This typical profit & loss dashboard includes progress bars, donut charts, column charts, line graphs, and everything that’s required to deliver a comprehensive report about a company’s financial situation.

Overwhelming visuals

One of the mistakes related to using data-presenting methods is including too much data or using overly complex visualizations. They can confuse the audience and dilute the key message.

Inappropriate chart types

Choosing the wrong type of chart for the data at hand can lead to misinterpretation. For example, using a pie chart for data that doesn’t represent parts of a whole is not right.

Lack of context

Failing to provide context or sufficient labeling can make it challenging for the audience to understand the significance of the presented data.

Inconsistency in design

Using inconsistent design elements and color schemes across different visualizations can create confusion and visual disarray.

Failure to provide details

Simply presenting raw data without offering clear insights or takeaways can leave the audience without a meaningful conclusion.

Lack of focus

Not having a clear focus on the key message or main takeaway can result in a presentation that lacks a central theme.

Visual accessibility issues

Overlooking the visual accessibility of charts and graphs can exclude certain audience members who may have difficulty interpreting visual information.

In order to avoid these mistakes in data presentation, presenters can benefit from using presentation templates . These templates provide a structured framework. They ensure consistency, clarity, and an aesthetically pleasing design, enhancing data communication’s overall impact.

Understanding and choosing data presentation types are pivotal in effective communication. Each method serves a unique purpose, so selecting the appropriate one depends on the nature of the data and the message to be conveyed. The diverse array of presentation types offers versatility in visually representing information, from bar charts showing values to pie charts illustrating proportions.

Using the proper method enhances clarity, engages the audience, and ensures that data sets are not just presented but comprehensively understood. By appreciating the strengths and limitations of different presentation types, communicators can tailor their approach to convey information accurately, developing a deeper connection between data and audience understanding.

[1] Government of Canada, S.C. (2021) 5 Data Visualization 5.2 Bar Chart , 5.2 Bar chart . https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/edu/power-pouvoir/ch9/bargraph-diagrammeabarres/5214818-eng.htm

[2] Kosslyn, S.M., 1989. Understanding charts and graphs. Applied cognitive psychology, 3(3), pp.185-225. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADA183409.pdf

[3] Creating a Dashboard . https://it.tufts.edu/book/export/html/1870

[4] https://www.goldenwestcollege.edu/research/data-and-more/data-dashboards/index.html

[5] https://www.mit.edu/course/21/21.guide/grf-line.htm

[6] Jadeja, M. and Shah, K., 2015, January. Tree-Map: A Visualization Tool for Large Data. In GSB@ SIGIR (pp. 9-13). https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-1393/gsb15proceedings.pdf#page=15

[7] Heat Maps and Quilt Plots. https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/research/population-health-methods/heat-maps-and-quilt-plots

[8] EIU QGIS WORKSHOP. https://www.eiu.edu/qgisworkshop/heatmaps.php

[9] About Pie Charts. https://www.mit.edu/~mbarker/formula1/f1help/11-ch-c8.htm

[10] Histograms. https://sites.utexas.edu/sos/guided/descriptive/numericaldd/descriptiven2/histogram/ [11] https://asq.org/quality-resources/scatter-diagram

Like this article? Please share

Data Analysis, Data Science, Data Visualization Filed under Design

Related Articles

Filed under Design • March 27th, 2024

How to Make a Presentation Graph

Detailed step-by-step instructions to master the art of how to make a presentation graph in PowerPoint and Google Slides. Check it out!

Filed under Presentation Ideas • January 6th, 2024

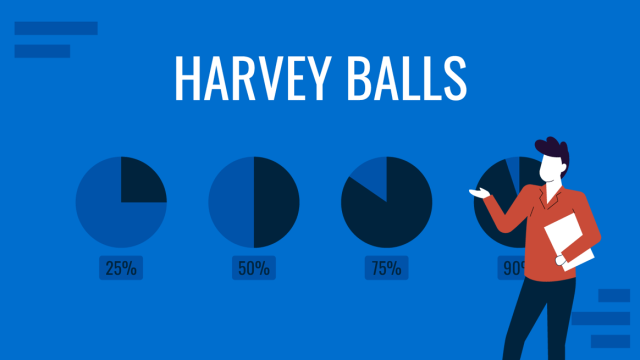

All About Using Harvey Balls

Among the many tools in the arsenal of the modern presenter, Harvey Balls have a special place. In this article we will tell you all about using Harvey Balls.

Filed under Business • December 8th, 2023

How to Design a Dashboard Presentation: A Step-by-Step Guide

Take a step further in your professional presentation skills by learning what a dashboard presentation is and how to properly design one in PowerPoint. A detailed step-by-step guide is here!

Leave a Reply

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Present Your Data Like a Pro

- Joel Schwartzberg

Demystify the numbers. Your audience will thank you.

While a good presentation has data, data alone doesn’t guarantee a good presentation. It’s all about how that data is presented. The quickest way to confuse your audience is by sharing too many details at once. The only data points you should share are those that significantly support your point — and ideally, one point per chart. To avoid the debacle of sheepishly translating hard-to-see numbers and labels, rehearse your presentation with colleagues sitting as far away as the actual audience would. While you’ve been working with the same chart for weeks or months, your audience will be exposed to it for mere seconds. Give them the best chance of comprehending your data by using simple, clear, and complete language to identify X and Y axes, pie pieces, bars, and other diagrammatic elements. Try to avoid abbreviations that aren’t obvious, and don’t assume labeled components on one slide will be remembered on subsequent slides. Every valuable chart or pie graph has an “Aha!” zone — a number or range of data that reveals something crucial to your point. Make sure you visually highlight the “Aha!” zone, reinforcing the moment by explaining it to your audience.

With so many ways to spin and distort information these days, a presentation needs to do more than simply share great ideas — it needs to support those ideas with credible data. That’s true whether you’re an executive pitching new business clients, a vendor selling her services, or a CEO making a case for change.

- JS Joel Schwartzberg oversees executive communications for a major national nonprofit, is a professional presentation coach, and is the author of Get to the Point! Sharpen Your Message and Make Your Words Matter and The Language of Leadership: How to Engage and Inspire Your Team . You can find him on LinkedIn and X. TheJoelTruth

Partner Center

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

4 Presenting Data

- Published: July 2009

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Data presentation can greatly influence audiences. This chapter reviews principles and approaches for presenting data, focusing on whether data needs to be used. Data can presented using words alone (e.g., metaphors or narratives), numbers (e.g., tables), symbols (e.g., bar charts or line graphs), or some combination that integrates these methods. Although new software packages and advanced techniques are available, visual symbols that can most readily and effectively communicate public health data are pie charts, bar charts, line graphs, icons/icon arrays, visual scales, and maps. Perceptual cues, especially proximity, continuation, and closure, influence how people process information. Contextual cues help enhance meaning by providing sufficient context to help audiences better understand data. Effective data presentation depends upon articulating the purpose for communicating, understanding audiences and context, and developing storylines to be communicated, taking into account the need to present data ethically and in a manner easily understood.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Data Presentation

Josée Dupuis, PhD, Professor of Biostatistics, Boston University School of Public Health

Wayne LaMorte, MD, PhD, MPH, Professor of Epidemiology, Boston University School of Public Health

Introduction

While graphical summaries of data can certainly be powerful ways of communicating results clearly and unambiguously in a way that facilitates our ability to think about the information, poorly designed graphical displays can be ambiguous, confusing, and downright misleading. The keys to excellence in graphical design and communication are much like the keys to good writing. Adhere to fundamental principles of style and communicate as logically, accurately, and clearly as possible. Excellence in writing is generally achieved by avoiding unnecessary words and paragraphs; it is efficient. In a similar fashion, excellence in graphical presentation is generally achieved by efficient designs that avoid unnecessary ink.

Excellence in graphical presentation depends on:

- Choosing the best medium for presenting the information

- Designing the components of the graph in a way that communicates the information as clearly and accurately as possible.

Table or Graph?

- Tables are generally best if you want to be able to look up specific information or if the values must be reported precisely.

- Graphics are best for illustrating trends and making comparisons

The side by side illustrations below show the same information, first in table form and then in graphical form. While the information in the table is precise, the real goal is to compare a series of clinical outcomes in subjects taking either a drug or a placebo. The graphical presentation on the right makes it possible to quickly see that for each of the outcomes evaluated, the drug produced relief in a great proportion of subjects. Moreover, the viewer gets a clear sense of the magnitude of improvement, and the error bars provided a sense of the uncertainty in the data.

Principles for Table Display

- Sort table rows in a meaningful way

- Avoid alphabetical listing!

- Use rates, proportions or ratios in addition (or instead of) totals

- Show more than two time points if available

- Multiple time points may be better presented in a Figure

- Similar data should go down columns

- Highlight important comparisons

- Show the source of the data

Consider the data in the table below from http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/commoncancers

Our ability to quickly understand the relative frequency of these cancers is hampered by presenting them in alphabetical order. It is much easier for the reader to grasp the relative frequency by listing them from most frequent to least frequent as in the next table.

However, the same information might be presented more effectively with a dot plot, as shown below.

Data from http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/types/commoncancers

Principles of Graphical Excellence from E.R. Tufte

Pattern perception.

Pattern perception is done by

- Detection: recognition of geometry encoding physical values

- Assembly: grouping of detected symbol elements; discerning overall patterns in data

- Estimation: assessment of relative magnitudes of two physical values

Geographic Variation in Cancer

As an example, Tufte offers a series of maps that summarize the age-adjusted mortality rates for various types of cancer in the 3,056 counties in the United States. The maps showing the geographic variation in stomach cancer are shown below.

These maps summarize an enormous amount of information and present it efficiently, coherently, and effectively.in a way that invites the viewer to make comparisons and to think about the substance of the findings. Consider, for example, that the region to the west of the Great Lakes was settled largely by immigrants from Germany and Scand anavia, where traditional methods of preserving food included pickling and curing of fish by smoking. Could these methods be associated with an increased risk of stomach cancer?

John Snow's Spot Map of Cholera Cases

Consider also the spot map that John Snow presented after the cholera outbreak in the Broad Street section of London in September 1854. Snow ascertained the place of residence or work of the victims and represented them on a map of the area using a small black disk to represent each victim and stacking them when more than one occurred at a particular location. Snow reasoned that cholera was probably caused by something that was ingested, because of the intense diarrhea and vomiting of the victims, and he noted that the vast majority of cholera deaths occurred in people who lived or worked in the immediate vicinity of the broad street pump (shown with a red dot that we added for clarity). He further ascertained that most of the victims drank water from the Broad Street pump, and it was this evidence that persuaded the authorities to remove the handle from the pump in order to prevent more deaths.

Humans can readily perceive differences like this when presented effectively as in the two previous examples. However, humans are not good at estimating differences without directly seeing them (especially for steep curves), and we are particularly bad at perceiving relative angles (the principal perception task used in a pie chart).

The use of pie charts is generally discouraged. Consider the pie chart on the left below. It is difficult to accurately assess the relative size of the components in the pie chart, because the human eye has difficulty judging angles. The dot plot on the right shows the same data, but it is much easier to quickly assess the relative size of the components and how they changed from Fiscal Year 2000 to Fiscal Year 2007.

Consider the information in the two pie charts below (showing the same information).The 3-dimensional pie chart on the left distorts the relative proportions. In contrast the 2-dimensional pie chart on the right makes it much easier to compare the relative size of the varies components..

More Principles of Graphical Excellence

Exclude unneeded dimensions.

These 3-dimensional techniques distort the data and actually interfere with our ability to make accurate comparisons. The distortion caused by 3-dimensional elements can be particularly severe when the graphic is slanted at an angle or when the viewer tends to compare ends up unwittingly comparing the areas of the ink rather than the heights of the bars.

It is much easier to make comparisons with a chart like the one below.

Source: Huang, C, Guo C, Nichols C, Chen S, Martorell R. Elevated levels of protein in urine in adulthood after exposure to

the Chinese famine of 1959–61 during gestation and the early postnatal period. Int. J. Epidemiol. (2014) 43 (6): 1806-1814 .

Omit "Chart Junk"

Consider these two examples.

Here is a simple enumeration of the number of pets in a neighborhood. There is absolutely no reason to connect these counts with lines. This is, in fact, confusing and inappropriate and nothing more than "chart junk."

Source: http://www.go-education.com/free-graph-maker.html

Moiré Vibration

Moiré effects are sometimes used in modern art to produce the appearance of vibration and movement. However, when these effects are applied to statistical presentations, they are distracting and add clutter because the visual noise interferes with the interpretation of the data.

Tufte presents the example shown below from Instituto de Expansao Commercial, Brasil, Graphicos Estatisticas (Rio de Janeiro, 1929, p. 15).

While the intention is to present quantitative information about the textile industry, the moiré effects do not add anything, and they are distracting, if not visually annoying.

Present Data to Facilitate Comparisons

Here is an attempt to compare catches of cod fish and crab across regions and to relate the variation to changes in water temperature. The problem here is that the Y-axes are vastly different, making it hard to sort out what's really going on. Even the Y-axes for temperature are vastly different.

http://seananderson.ca/courses/11-multipanel/multipanel.pdf1

The ability to make comparisons is greatly facilitated by using the same scales for axes, as illustrated below.

Data source: Dawber TR, Meadors GF, Moore FE Jr. Epidemiological approaches to heart disease:

the Framingham Study. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1951;41(3):279-81. PMID: 14819398

It is also important to avoid distorting the X-axis. Note in the example below that the space between 0.05 to 0.1 is the same as space between 0.1 and 0.2.

Source: Park JH, Gail MH, Weinberg CR, et al. Distribution of allele frequencies and effect sizes and

their interrelationships for common genetic susceptibility variants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011; 108:18026-31.

Consider the range of the Y-axis. In the examples below there is no relevant information below $40,000, so it is not necessary to begin the Y-axis at 0. The graph on the right makes more sense.

Also, consider using a log scale. this can be particularly useful when presenting ratios as in the example below.

Source: Broman KW, Murray JC, Sheffield VC, White RL, Weber JL (1998) Comprehensive human genetic maps:

Individual and sex-specific variation in recombination. American Journal of Human Genetics 63:861-869, Figure 1

We noted earlier that pie charts make it difficult to see differences within a single pie chart, but this is particularly difficult when data is presented with multiple pie charts, as in the example below.

Source: Bell ML, et al. (2007) Spatial and temporal variation in PM2.5 chemical composition in the United States

for health effects studies. Environmental Health Perspectives 115:989-995, Figure 3

When multiple comparisons are being made, it is essential to use colors and symbols in a consistent way, as in this example.

Source: Manning AK, LaValley M, Liu CT, et al. Meta-Analysis of Gene-Environment Interaction:

Joint Estimation of SNP and SNP x Environment Regression Coefficients. Genet Epidemiol 2011, 35(1):11-8.

Avoid putting too many lines on the same chart. In the example below, the only thing that is readily apparent is that 1980 was a very hot summer.

Data from National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office at

http://www.srh.noaa.gov/tsa/?n=climo_tulyeartemp

Make Efficient Use of Space

Reduce the ratio of ink to information.

This isn't efficient, because this graphic is totally uninformative.

Source: Mykland P, Tierney L, Yu B (1995) Regeneration in Markov chain samplers. Journal of the American Statistical Association 90:233-241, Figure 1

Bar graphs add ink without conveying any additional information, and they are distracting. The graph below on the left inappropriately uses bars which clutter the graph without adding anything. The graph on the right displays the same data, by does so more clearly and with less clutter.

Multiple Types of Information on the Same Figure

Choosing the best graph type, bar charts, error bars and dot plots.

As noted previously, bar charts can be problematic. Here is another one presenting means and error bars, but the error bars are misleading because they only extend in one direction. A better alternative would have been to to use full error bars with a scatter plot, as illustrated previously (right).

Consider the four graphs below presenting the incidence of cancer by type. The upper left graph unnecessary uses bars, which take up a lot of ink. This layout also ends up making the fonts for the types of cancer too small. Small font is also a problem for the dot plot at the upper right, and this one also has unnecessary grid lines across the entire width.