- Business & Money

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: $48.98

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Museum Education for Today's Audiences: Meeting Expectations with New Models (American Alliance of Museums)

Purchase options and add-ons.

Today’s museum educators are tackling urgent social issues, addressing historic inequalities of museum collections, innovating for accessibility, leveraging technology for new in-person and virtual learning experiences, and cultivating partnerships with schools, businesses, elders, scientists, and other social services to build relationships and be of service to their communities. Despite the physical distance the pandemic placed between museums and their visitors, museum educators have remained essential -- sustaining connections with the public through virtual or modified programming, content development, and conversations that they are uniquely qualified to execute. Educators require updated resources to guide their efforts in navigating these new challenges and building upon the opportunities presented by current events and changing audiences.

This book and its accompanying on-line resource share lessons from innovators in the field to support ongoing professional development efforts with essays about current issues. Additionally, it provides new models and tools to guide individual or group reflection on how today’s museum educators can adapt and thrive in a dynamic and ever-changing cultural sector. The additional resources include discussion prompts and adaptable templates to allow readers to customize the content based on current events, institutional discipline, size, budget, and staffing scenario of their organization.

The book’s essays are divided into three sections:

- Changing expectations of visitors - inclusion, participation, and technology

- Training and preparation for responsive, resourceful educators

- Models for the future

- ISBN-10 1538148609

- ISBN-13 978-1538148600

- Publisher American Alliance Of Museums

- Publication date February 15, 2022

- Part of series American Alliance of Museums

- Language English

- Dimensions 7 x 0.81 x 9.59 inches

- Print length 314 pages

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Editorial Reviews

One of the powerful things about Museum Education for Today’s Audiences: it feels as though it is written by friends and colleagues, by people you know well and who really understand what our work is like, by those who you would ask for advice from as you tackle some thorny issues. In being so, it works to uplift the reader and their practice through not just providing access to tools, but also giving us the opportunities to explore how best we might use them in our own settings and contexts.

Amidst an intense moment of crisis and upheaval, Porter and Cunningham have brought together a practical and hope-filled collection of writings that can guide museum educators—and the entire museum field—into a new future. All of the contributors to this important book make clear the vital role of museum education in leading the transformation needed right now within our institutions.

This book lands at a critical moment in the history of museums in the United States. It is equal parts manifesto on the power and potential of museums who center community needs and interests, and handbook for the education staff who have championed and led this work for decades, and are now uniquely equipped to help reshape their organizations’ relationship and value to communities.

Museum Education for Today’s Audience is more than just a book. It is an incredible tool that goes beyond program ideas to provide insight on lessons learned by practitioners in the field that are decentering systemic exclusion. More importantly, this book provides the spark for reflective practice to support continued innovation to meet the needs of all learners and increased self-awareness for museum educators.

About the Author

Jason L. Porter is the Kayla Skinner Deputy Director for Education and Public Engagement at Seattle Art Museum. Previously, he served as the director of education + Programs at MoPOP (Museum of Pop Culture) in Seattle, as director of education and public engagement at the San Diego Museum of Man (now Museum of Us) and associate director of education at the Skirball Cultural Center in Los Angeles. His work focuses on experiential education and public programs that serve community, school, family, and teacher audiences and on using the arts as a vehicle for personal transformation and social change. Prior to entering the museum field, he was a public school teacher. He received a B.A. in English from Tufts University, an M.A. in Education from Seattle University, and an Ed.D from UCLA. His dissertation examined charter schools meeting the needs of special education students. Professional development activities have included presentations at conferences including AAM, CAM, and WMA, serving as a mentor to emerging museum professionals and teaching as a guest lecturer in a number of museum studies programs. He has been a board member of AAM’s Education Professional Network (EdCom) from 2014 through 2016, a jurist with the Excellence in Exhibitions competition in 2017 and 2018, a grants reviewer for IMLS in 2018, and a member of the peer review board of the Journal of Museum Education (JME) since 2016.

In the last 25+ years, Mary Kay Cunningham has served over 35 different cultural institutions or attractions in the diverse roles of consultant, manager, museum educator, volunteer coordinator, and docent. She founded Dialogue Consulting in 2001 to support institutions improving their visitor experience through inclusive and collaborative interpretive planning, programming, and professional development. Her passion for facilitating group learning that brings together staff, volunteers, and communities to navigate institutional change is the hallmark of her work.

Mary Kay is the author of The Interpreters Training Manual for Museums that guides front line staff in facilitating meaningful learning conversations with visitors. As a professed learning addict, she pursues and support professional development in the field by serving on the editorial board of The Journal of Museum Education since 2010, creating and instructing a graduate-level course on Visitor Experience design at the University of Victoria, B.C. since 2013, and presenting over 45 sessions or workshops in the last 20 years for professional meetings including AAM, APGA, ASTC, CAM, NAI, and WMA.

Product details

- Publisher : American Alliance Of Museums (February 15, 2022)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 314 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1538148609

- ISBN-13 : 978-1538148600

- Item Weight : 1.45 pounds

- Dimensions : 7 x 0.81 x 9.59 inches

- #172 in Museum Industry

- #477 in Museum Studies & Museology (Books)

- #50,683 in Unknown

About the author

Mary kay cunningham.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

No customer reviews

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- Browse by Subjects

- New Releases

- Coming Soon

- Chases's Calendar

- Browse by Course

- Instructor's Copies

- Monographs & Research

- Intelligence & Security

- Library Services

- Business & Leadership

- Museum Studies

- Pastoral Resources

- Psychotherapy

Museum Education for Today's Audiences

Meeting expectations with new models, edited by jason l. porter and mary kay cunningham.

Today’s museum educators are tackling urgent social issues, addressing historic inequalities of museum collections, innovating for accessibility, leveraging technology for new in-person and virtual learning experiences, and cultivating partnerships with schools, businesses, elders, scientists, and other social services to build relationships and be of service to their communities. Despite the physical distance the pandemic placed between museums and their visitors, museum educators have remained essential -- sustaining connections with the public through virtual or modified programming, content development, and conversations that they are uniquely qualified to execute. Educators require updated resources to guide their efforts in navigating these new challenges and building upon the opportunities presented by current events and changing audiences.

This book and its accompanying on-line resource share lessons from innovators in the field to support ongoing professional development efforts with essays about current issues. Additionally, it provides new models and tools to guide individual or group reflection on how today’s museum educators can adapt and thrive in a dynamic and ever-changing cultural sector. The additional resources include discussion prompts and adaptable templates to allow readers to customize the content based on current events, institutional discipline, size, budget, and staffing scenario of their organization.

The book’s essays are divided into three sections:

- Changing expectations of visitors - inclusion, participation, and technology

- Training and preparation for responsive, resourceful educators

- Models for the future

While a book can share ideas in the hope of inspiring change, the accompanying online resource ( www.EvolveMuseumEd.com ) provides a more flexible and responsive forum for sharing ongoing and evolving resources to encourage professional development for museum educators as they respond to the changing needs of today’s audiences.

ALSO AVAILABLE

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Museums, Education, and Curriculum

Introduction, general overviews.

- National Reports and White Papers

- Associations

- Museum Field Trips—Structure and Management

- Learning from Museum Field Trips

- Museum-School Relationships and Teacher Training

- Museum Schools

- Planning for Education in the Museum

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Curriculum Design

- Integrating Art across the Curriculum

- Science Education

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- English as an International Language for Academic Publishing

- Girls' Education in the Developing World

- History of Education in Europe

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Museums, Education, and Curriculum by Elee Wood LAST REVIEWED: 25 September 2018 LAST MODIFIED: 25 September 2018 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756810-0205

The relationship between museums, education, and curricula is complex. Many early museums—established in order to study, showcase, and preserve collections of art, artifacts, and specimens—typically had narrowly defined educational goals or purposes. Over time and particularly by the 20th century, museums reframed their focus as locations for informal and lifelong or life wide learning and catered to a range of audiences including school groups. The educational role of museums reflects an intentional approach in planning for learning through a variety of strategies including exhibitions, “live” and informal interpretation experiences, formal programming, field trip experiences and written lesson plans or study guides. The unique nature of museum environments as locations for learning provides ample opportunities to study the role of museums in formal education through field trips, study collections, partnerships and outreach; training of teachers and teachers in training; the learning structures and strategies employed in exhibitions, programs, and curricular resources; and the establishment of formal schools within the museum setting.

The educational goals of museums have a long history grounded in their basic missions and museums have expanded the strategies and intensity of educational practice throughout the 20th century. Hooper-Greenhill 1999 is an edited volume providing an overview of museum education practices; it draws on a range of philosophies and practices that span multiple disciplines. Hein 1998 outlines educational philosophies contributing to the basic practices of museum education and offers discussion on the role and value of museum learning. Notably, the discussion on the relationship between the practices of museum education and curriculum have expanded in the past several decades as the field of curriculum studies became more established as in Lindauer 2015 . Considering the role of curriculum in the museum has become important discourse among museum educators, beginning with Beer 1987 examining whether museums have defined curricular goals to the more contemporary application of curriculum practices of knowledge production in Rose 2006 and the broader implications of intentionally designed experiences in Roberts 2006 . Both Vallance 2004 and Burchenal and Grohe 2007 explore the curricular role of museums stemming from the stance of art and art education, and Stocklmayer, et al. 2010 outlines the relationship between science education curriculum and schools. Garcia 2012 brings discussion on broader school learning outcomes to museum goals.

Beer, Valorie. 1987. Do museums have “curriculum”? The Journal of Museum Education 12.3: 10–13.

Example of the emerging discussions in the museum field on the role of curriculum as a function of museum spaces. Describes key ideas in broadening the idea of curriculum beyond formal education and into “nonschool” settings. Available online with subscription.

Burchenal, Margaret, and Michelle Grohe. 2007. Thinking through art: Transforming museum curriculum. Journal of Museum Education 32.2: 111–122.

DOI: 10.1080/10598650.2007.11510563

Develops a connection between needs of school children and the specific programming opportunities offered by art museums.

Garcia, Ben. 2012. What we do best. Journal of Museum Education 37.2: 47–55.

DOI: 10.1080/10598650.2012.11510730

Defines museum learning in contrast to formal educational systems and argues for new ways to ascribe learning in the museum setting.

Hein, George. 1998. Learning in the museum . London: Routledge.

Application of educational philosophies in the museum experience. Includes an examination of research methods in museums as well as strategies for developing exhibitions and learning experiences.

Hooper-Greenhill, Eilean. 1999. The educational role of the museum . 2d ed. London: Routledge.

Edited volume geared toward museum professionals that incorporates a broad view of educational theory and practice as it plays out in the museum setting. Includes discussion on different museum audiences and approaches to learning.

Lindauer, Margaret A. 2015. Looking at museum education through the lens of curriculum theory. Journal of Museum Education 31.2: 79–80.

DOI: 10.1080/10598650.2006.11510534

Short overview of the concept of curriculum studies as it applies to museum education practices.

Roberts, Patrick. 2006. Am I the public I think I am?: Understanding the public curriculum of museums as “complicated conversation.” Journal of Museum Education 31.2: 105–112.

DOI: 10.1080/10598650.2006.11510537

Case study on a museum exhibition and the role of curriculum theory in museum education.

Rose, Julia. 2006. Shared journeys curriculum theory and museum education. Journal of Museum Education 31.2: 81–93.

DOI: 10.1080/10598650.2006.11510535

Explores the relationships between curriculum theory and museum education practices. Focuses on the role of knowledge production, democratization of the museum, and the role of museum interpretation in shaping knowledge.

Stocklmayer, Susan M., Léonie J. Rennie, and John K. Gilbert. 2010. The roles of the formal and informal sectors in the provision of effective science education. Studies in Science Education 46.1: 1–44.

DOI: 10.1080/03057260903562284

Article on the role of collaboration between museums and science education in formal education settings and how it can better support student learning. Examines critiques of formal science education and the role of informal learning approaches to augment learning.

Vallance, Elizabeth. 2004. Museum education as curriculum: Four models, leading to a fifth. Studies in Art Education 45.4: 343–358.

Describes classic curricular models in relation to art education practices in museums. Proposes a new model that integrates art museum practice with traditional curriculum theory.

Villeneuve, P., ed. 2007. From periphery to center: Art museum education in the 21st century . Reston, VA: National Art Education Association.

Edited volume that provides insight into the changing nature of education within art museums. Addresses theory and practice as well as current issues and emphasizes the role of art museum educators and approaching new audiences.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Education »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Academic Achievement

- Academic Audit for Universities

- Academic Freedom and Tenure in the United States

- Action Research in Education

- Adjuncts in Higher Education in the United States

- Administrator Preparation

- Adolescence

- Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate Courses

- Advocacy and Activism in Early Childhood

- African American Racial Identity and Learning

- Alaska Native Education

- Alternative Certification Programs for Educators

- Alternative Schools

- American Indian Education

- Animals in Environmental Education

- Art Education

- Artificial Intelligence and Learning

- Assessing School Leader Effectiveness

- Assessment, Behavioral

- Assessment, Educational

- Assessment in Early Childhood Education

- Assistive Technology

- Augmented Reality in Education

- Beginning-Teacher Induction

- Bilingual Education and Bilingualism

- Black Undergraduate Women: Critical Race and Gender Perspe...

- Blended Learning

- Case Study in Education Research

- Changing Professional and Academic Identities

- Character Education

- Children’s and Young Adult Literature

- Children's Beliefs about Intelligence

- Children's Rights in Early Childhood Education

- Citizenship Education

- Civic and Social Engagement of Higher Education

- Classroom Learning Environments: Assessing and Investigati...

- Classroom Management

- Coherent Instructional Systems at the School and School Sy...

- College Admissions in the United States

- College Athletics in the United States

- Community Relations

- Comparative Education

- Computer-Assisted Language Learning

- Computer-Based Testing

- Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Evaluating Improvement Net...

- Continuous Improvement and "High Leverage" Educational Pro...

- Counseling in Schools

- Critical Approaches to Gender in Higher Education

- Critical Perspectives on Educational Innovation and Improv...

- Critical Race Theory

- Crossborder and Transnational Higher Education

- Cross-National Research on Continuous Improvement

- Cross-Sector Research on Continuous Learning and Improveme...

- Cultural Diversity in Early Childhood Education

- Culturally Responsive Leadership

- Culturally Responsive Pedagogies

- Culturally Responsive Teacher Education in the United Stat...

- Data Collection in Educational Research

- Data-driven Decision Making in the United States

- Deaf Education

- Desegregation and Integration

- Design Thinking and the Learning Sciences: Theoretical, Pr...

- Development, Moral

- Dialogic Pedagogy

- Digital Age Teacher, The

- Digital Citizenship

- Digital Divides

- Disabilities

- Distance Learning

- Distributed Leadership

- Doctoral Education and Training

- Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) in Denmark

- Early Childhood Education and Development in Mexico

- Early Childhood Education in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Childhood Education in Australia

- Early Childhood Education in China

- Early Childhood Education in Europe

- Early Childhood Education in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Early Childhood Education in Sweden

- Early Childhood Education Pedagogy

- Early Childhood Education Policy

- Early Childhood Education, The Arts in

- Early Childhood Mathematics

- Early Childhood Science

- Early Childhood Teacher Education

- Early Childhood Teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Years Professionalism and Professionalization Polici...

- Economics of Education

- Education For Children with Autism

- Education for Sustainable Development

- Education Leadership, Empirical Perspectives in

- Education of Native Hawaiian Students

- Education Reform and School Change

- Educational Statistics for Longitudinal Research

- Educator Partnerships with Parents and Families with a Foc...

- Emotional and Affective Issues in Environmental and Sustai...

- Emotional and Behavioral Disorders

- Environmental and Science Education: Overlaps and Issues

- Environmental Education

- Environmental Education in Brazil

- Epistemic Beliefs

- Equity and Improvement: Engaging Communities in Educationa...

- Equity, Ethnicity, Diversity, and Excellence in Education

- Ethical Research with Young Children

- Ethics and Education

- Ethics of Teaching

- Ethnic Studies

- Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention

- Family and Community Partnerships in Education

- Family Day Care

- Federal Government Programs and Issues

- Feminization of Labor in Academia

- Finance, Education

- Financial Aid

- Formative Assessment

- Future-Focused Education

- Gender and Achievement

- Gender and Alternative Education

- Gender, Power and Politics in the Academy

- Gender-Based Violence on University Campuses

- Gifted Education

- Global Mindedness and Global Citizenship Education

- Global University Rankings

- Governance, Education

- Grounded Theory

- Growth of Effective Mental Health Services in Schools in t...

- Higher Education and Globalization

- Higher Education and the Developing World

- Higher Education Faculty Characteristics and Trends in the...

- Higher Education Finance

- Higher Education Governance

- Higher Education Graduate Outcomes and Destinations

- Higher Education in Africa

- Higher Education in China

- Higher Education in Latin America

- Higher Education in the United States, Historical Evolutio...

- Higher Education, International Issues in

- Higher Education Management

- Higher Education Policy

- Higher Education Research

- Higher Education Student Assessment

- High-stakes Testing

- History of Early Childhood Education in the United States

- History of Education in the United States

- History of Technology Integration in Education

- Homeschooling

- Inclusion in Early Childhood: Difference, Disability, and ...

- Inclusive Education

- Indigenous Education in a Global Context

- Indigenous Learning Environments

- Indigenous Students in Higher Education in the United Stat...

- Infant and Toddler Pedagogy

- Inservice Teacher Education

- Intelligence

- Intensive Interventions for Children and Adolescents with ...

- International Perspectives on Academic Freedom

- Intersectionality and Education

- Knowledge Development in Early Childhood

- Leadership Development, Coaching and Feedback for

- Leadership in Early Childhood Education

- Leadership Training with an Emphasis on the United States

- Learning Analytics in Higher Education

- Learning Difficulties

- Learning, Lifelong

- Learning, Multimedia

- Learning Strategies

- Legal Matters and Education Law

- LGBT Youth in Schools

- Linguistic Diversity

- Linguistically Inclusive Pedagogy

- Literacy Development and Language Acquisition

- Literature Reviews

- Mathematics Identity

- Mathematics Instruction and Interventions for Students wit...

- Mathematics Teacher Education

- Measurement for Improvement in Education

- Measurement in Education in the United States

- Meta-Analysis and Research Synthesis in Education

- Methodological Approaches for Impact Evaluation in Educati...

- Methodologies for Conducting Education Research

- Mindfulness, Learning, and Education

- Mixed Methods Research

- Motherscholars

- Multiliteracies in Early Childhood Education

- Multiple Documents Literacy: Theory, Research, and Applica...

- Multivariate Research Methodology

- Museums, Education, and Curriculum

- Music Education

- Narrative Research in Education

- Native American Studies

- Nonformal and Informal Environmental Education

- Note-Taking

- Numeracy Education

- One-to-One Technology in the K-12 Classroom

- Online Education

- Open Education

- Organizing for Continuous Improvement in Education

- Organizing Schools for the Inclusion of Students with Disa...

- Outdoor Play and Learning

- Outdoor Play and Learning in Early Childhood Education

- Pedagogical Leadership

- Pedagogy of Teacher Education, A

- Performance Objectives and Measurement

- Performance-based Research Assessment in Higher Education

- Performance-based Research Funding

- Phenomenology in Educational Research

- Philosophy of Education

- Physical Education

- Podcasts in Education

- Policy Context of United States Educational Innovation and...

- Politics of Education

- Portable Technology Use in Special Education Programs and ...

- Post-humanism and Environmental Education

- Pre-Service Teacher Education

- Problem Solving

- Productivity and Higher Education

- Professional Development

- Professional Learning Communities

- Program Evaluation

- Programs and Services for Students with Emotional or Behav...

- Psychology Learning and Teaching

- Psychometric Issues in the Assessment of English Language ...

- Qualitative Data Analysis Techniques

- Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Research Samp...

- Qualitative Research Design

- Quantitative Research Designs in Educational Research

- Queering the English Language Arts (ELA) Writing Classroom

- Race and Affirmative Action in Higher Education

- Reading Education

- Refugee and New Immigrant Learners

- Relational and Developmental Trauma and Schools

- Relational Pedagogies in Early Childhood Education

- Reliability in Educational Assessments

- Religion in Elementary and Secondary Education in the Unit...

- Researcher Development and Skills Training within the Cont...

- Research-Practice Partnerships in Education within the Uni...

- Response to Intervention

- Restorative Practices

- Risky Play in Early Childhood Education

- Scale and Sustainability of Education Innovation and Impro...

- Scaling Up Research-based Educational Practices

- School Accreditation

- School Choice

- School Culture

- School District Budgeting and Financial Management in the ...

- School Improvement through Inclusive Education

- School Reform

- Schools, Private and Independent

- School-Wide Positive Behavior Support

- Secondary to Postsecondary Transition Issues

- Self-Regulated Learning

- Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices

- Service-Learning

- Severe Disabilities

- Single Salary Schedule

- Single-sex Education

- Single-Subject Research Design

- Social Context of Education

- Social Justice

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Pedagogy

- Social Science and Education Research

- Social Studies Education

- Sociology of Education

- Standards-Based Education

- Statistical Assumptions

- Student Access, Equity, and Diversity in Higher Education

- Student Assignment Policy

- Student Engagement in Tertiary Education

- Student Learning, Development, Engagement, and Motivation ...

- Student Participation

- Student Voice in Teacher Development

- Sustainability Education in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Higher Education

- Teacher Beliefs and Epistemologies

- Teacher Collaboration in School Improvement

- Teacher Evaluation and Teacher Effectiveness

- Teacher Preparation

- Teacher Training and Development

- Teacher Unions and Associations

- Teacher-Student Relationships

- Teaching Critical Thinking

- Technologies, Teaching, and Learning in Higher Education

- Technology Education in Early Childhood

- Technology, Educational

- Technology-based Assessment

- The Bologna Process

- The Regulation of Standards in Higher Education

- Theories of Educational Leadership

- Three Conceptions of Literacy: Media, Narrative, and Gamin...

- Tracking and Detracking

- Traditions of Quality Improvement in Education

- Transformative Learning

- Transitions in Early Childhood Education

- Tribally Controlled Colleges and Universities in the Unite...

- Understanding the Psycho-Social Dimensions of Schools and ...

- University Faculty Roles and Responsibilities in the Unite...

- Using Ethnography in Educational Research

- Value of Higher Education for Students and Other Stakehold...

- Virtual Learning Environments

- Vocational and Technical Education

- Wellness and Well-Being in Education

- Women's and Gender Studies

- Young Children and Spirituality

- Young Children's Learning Dispositions

- Young Children's Working Theories

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.194.105.172]

- 185.194.105.172

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Original Language Spotlight

- Alternative and Non-formal Education

- Cognition, Emotion, and Learning

- Curriculum and Pedagogy

- Education and Society

- Education, Change, and Development

- Education, Cultures, and Ethnicities

- Education, Gender, and Sexualities

- Education, Health, and Social Services

- Educational Administration and Leadership

- Educational History

- Educational Politics and Policy

- Educational Purposes and Ideals

- Educational Systems

- Educational Theories and Philosophies

- Globalization, Economics, and Education

- Languages and Literacies

- Professional Learning and Development

- Research and Assessment Methods

- Technology and Education

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Teaching and learning in the art museum.

- Emily Pringle Emily Pringle Tate Gallery

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.399

- Published online: 20 November 2018

Activities that actively and deliberately support museum visitors’ engagement with art and promote learning occupy a distinct, though contested, place in the history and current framing of the art museum across the globe. Despite its many benefits, educational work in art museums has grown erratically, frequently without formal structures, systems, or strategies, and it has been critiqued in the past for lacking a robust theoretical framework and consistent methodological principles. It remains the case that the field is broad, diverse, and continually evolving; in the early 21st century, the boundaries are shifting, for example, between what constitutes curatorial practice and learning practice in contemporary art museums. This fluidity and heterogeneity has enabled the emergence of creative and responsive practice that encourages visitors to learn with, through, and about art, but it poses challenges when the goal is to present a coherent overview. Therefore any summary of this complex domain will necessarily be selective. Nonetheless, taking the practice as it has been developed in the United Kingdom and the United States, where this work has been theorized and communicated to the greatest extent (and with reference to the practice in Europe, Canada, and Australia), it is possible to identify common historical developments, shared philosophical and pedagogical principles, and collective challenges and opportunities that contribute to a comprehensible picture, albeit one that is replete with contradictions. As a field, art-museum education continues to define itself. And although valuable research and theorization have been undertaken, in part by practitioners drawing on their own experiences, further work is required, not least to broaden the understanding of the practice as it is manifest globally and to make explicit the increasingly important role of art education within the art museum.

- art education

- museum education

- art practice

- socially engaged art practice

Introduction and Terms of Reference

The 21st century has presented museums with extraordinary opportunities for growth, yet this has been coupled with significant challenges in maintaining their positions as authoritative yet accessible cultural institutions. Art museums are being expanded, renovated, and constructed across the world; attendance figures in the West rose from 22 million in 1962 to over 100 million in 2000 (McClellan, 2008 , p. 2). At the same time, in Europe and North America at least, museums exist in a climate of reduced public funding and intense competition for corporate sponsorship. This is coupled with global expectations of greater cultural participation and co-production, generated by new technology and social media. Moreover, as highly visible manifestations of sanctioned culture, art museums are implicated in the reality of a more divisive and polarized society, where gender and race politics are at the forefront of public debate. There is an urgent need for museums to address issues of social and cultural discrimination, as well as to attract new audiences and offer cultural experiences that are relevant and engaging.

The urgency to “grasp the opportunities presented by our changing society or lose relevance within a generation” (Black, 2012b , p. 7) finds form in the museum mission statements and statements by gallery directors that declare their ambitions to reach out, become more inclusive, and prioritize the visitor. No longer circumscribed exclusively by the accumulation and preservation of its collection, the 21st-century art museum is ostensibly defined by its social role as a public-oriented civic site, whose purpose is to stimulate debate, foster active participation, and work collaboratively with its audiences. The drive of art museums to reach out has fueled an expansion in education programming as a means to achieve these ambitions. However, teaching and learning activities have occupied an uneasy place in the history of the art museum, challenging those institutions from within, yet simultaneously offering innovative pedagogy and creative forms of artistic engagement with collections. At times overlooked or misunderstood, art-museum education would benefit from sustained and detailed analysis to more fully understand the contribution it has made and the value it brings to museums and their visitors across the globe.

This article begins by clarifying key terms and making the specific opportunities presented by the art museum clear, before outlining the historical development of art-museum education from the late 19th century onward. It then spells out the diverse agendas and ambitions for museum education, to help rationalize the diversity of practice found in the art museum in the 21st century (see the section “ Clarifying Terminology ”). Art-museum education is informed by a variety of disciplines and intellectual traditions, theories, and practices. The section “ Art Museum Epistemology and Pedagogy ” details these, drawing attention to the central role art practice plays in shaping the forms of teaching and learning taking place in the museum. The article concludes by drawing attention to the challenges facing art-museum education and the outstanding questions that would profit from further research.

Clarifying Terminology

To understand the field of learning in art museums it is necessary to clarify various terms, not least the descriptors “museum” and “gallery,” which tend to be employed interchangeably but are applied differently in the United Kingdom and the United States. A commonly accepted worldwide understanding of the museum is as a “non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development, open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education study and enjoyment” (International Council of Museums, 2007 ). Museums are thus characterized both by their social and educational responsibilities and by the curation of their collections (as suggested by the Latin origin of the term: curare , “to take care of”). These responsibilities are not commonly ascribed to galleries, particularly in North America, where the name “gallery” implies a commercial enterprise. However, in the United Kingdom, “gallery” can refer to public institutions with permanent collections (the National Gallery in London being one example). And increasingly, education activities are programmed in galleries, art biennales, and temporary art spaces. These practices adhere to and inform the principles and pedagogy of education work in the art museum, and at times work indivisibly with art museum education. Yet further confusion arises because the term gallery is also applied to art-exhibition spaces within museums, arts centers, and artists’ studios. For ease and clarity, the term art museum is employed here to refer broadly to collection-based art institutions in which education activities take place, recognizing, however, that teaching and learning occurs in art spaces more widely.

The terms learning and education are similarly used interchangeably in relation to pedagogic practices in art museums, and require contextualization. Although in the United Kingdom and parts of mainland Europe, the professional field is known as “gallery education,” since the early 2000s there has been a shift toward using the term “learning” to reinforce the process-driven and creative activity of gaining new or revised knowledge, skills, and values through engagement with art. This is in preference to “education,” which has come to be associated with structures, systems, and processes that are allied to formal instruction (Cutler, 2010 ). The term ‘teaching’ is rarely applied as a descriptor for art museum education, despite being evident in the gallery, in part because of the focus on constructivist pedagogy (see section “ Art Museum Epistemology and Pedagogy ”). This trend is most visibly manifest in the renaming of departments in individual museums from “education” to “learning” departments. In German-speaking countries, the term Kulturvermittlung covers a wide range of practices that broadly encompass the exchange of knowledge and ideas about the arts (Morsch, 2013 ); in the museum context, Kulturvermittlung embraces curatorial concepts and exhibition design, in addition to education (Richter, 2013 ). A similarly broad term— médiation culturelle —is gaining popularity in France. This refers less to the pedagogic practices of knowledge transmission and more to “the act of forming relationships of mutual exchange among publics, works, artists and institutions” (p. 7). Neither term has an exact English equivalent, although the term “cultural mediation” is most commonly substituted for both.

A third designation that requires qualification concerns learning in the art museum, rather than in museums generally. The former shares many of the epistemological, pedagogical, philosophical, and practical characteristics of learning in science, natural history, and ethnographic and historical museums, yet there are some fundamental differences, which are not always recognized in the museological literature. Hooper-Greenhill, for example, differentiates between “museum” education and “gallery” education in the title of her widely cited 1991 text, yet outlines a common educational philosophy and methodology to be applied across both (Hooper-Greenhill, 1991 ). This generalization owes partly to the lack of writing on art-museum education specifically; however, perceived variations in the approaches taken by artists and educators, the nature of the learning experience, and the expected outcomes of the learning process have been identified (see, e.g., Allen & Clive, 1995 ; Burnham & Kai-Kee, 2011 ; Xanthoudaki, Tickle, & Sekules, 2004 ).

Historic formalist conceptualizations of the art object positioned it as uniquely capable of facilitating transcendent contemplation in the form of an “aesthetic experience” that, as described by Clive Bell in 1914 , is visceral and embodied ( 1993 ). This experience instills in the viewer an appreciation of beauty and a love of “art,” and it sets the art object apart from all other material artefacts. This view has subsequently been challenged by, among other concepts, the view that looking at art is essentially a cognitive activity, analogous to deciphering a text (Barthes, 1977 ). Although the notion that the art object can and should be appreciated in and of itself without reference to its historical and social context has also been critiqued (for an introduction to this “new art history,” see Harris, 2001 ), the specificity of the art work, its relationship to its maker (the artist), and the theoretical discourses surrounding it continue to shape the distinctive pedagogic practices and content knowledge employed in the art museum.

Even in art museums, ontological differences exist between the modern and contemporary art work and the historic object that play out in the forms of teaching and learning that are adopted. A number of contemporary art galleries in the United Kingdom and internationally adopt a pedagogic model that draws on concepts associated with what has been described as “conceptual art,” in that it asks questions, not only of the art object—“Why is this art? Who is the artist? What is the context?”—but also of the viewer, “Who are you? What do you represent? It draws viewers’ attention to themselves” (Godfrey, 1998 , p. 15). Conceptual art by its very nature proposes a complex relationship between form and content, and the meaning of a work is not always easily accessible through viewing alone. Furthermore, the inevitable instability of meaning and the “shifting consensual process of determination” of contemporary art allow, if not require, diverse narratives to be held simultaneously (Sitzia, 2017 ). Teaching and learning in relation to these works is thus characterized by criticality and self-consciousness; it seeks to actively interrogate the ontology of the art object and the viewers’ relationship to it in ways that are not necessarily foregrounded in the study of historic art (Pringle, 2006 ).

Historical Development

Early formulations.

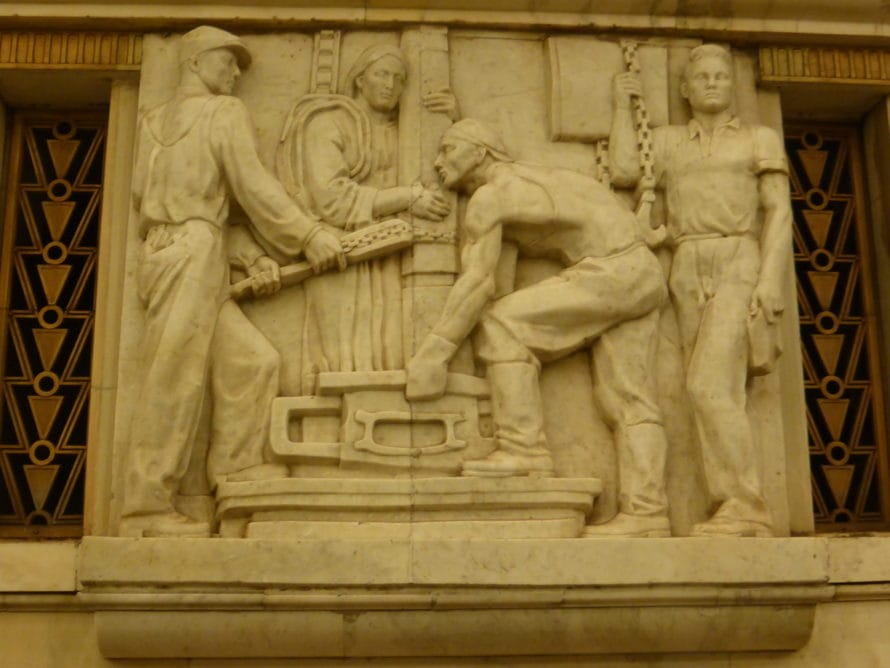

Learning in art museums has its roots in the 19th-century philanthropic drive, coupled with a belief in the power of art and culture to improve the individual and society at large. Ideas originating in the 18th-century Enlightenment shaped the perception held by early museum founders that the arts could enable the individual to transcend everyday concerns and emotions (Hooper-Greenhill, 1991 ). Visual art was considered to be intellectually, emotionally, and ethically beneficial, elevating the tastes of the working man, the museum providing an ideal space for self-improvement (Newson & Silver, 1978 ). In their early formulation, art museums, including the Metropolitan Museum, Smithsonian Institution, and Museum of Modern Art in the United States and the Victoria and Albert Museum and Tate Gallery in London, were understood to be intrinsically educational; their function being to enable individuals to “improve” themselves through access to art. Educators were employed in U.K. museums, first at Tate, in 1914 (Charman, 2005 ); and the first “docents” (trained volunteers) made their appearance in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston in 1907 , their function being to act as “intermediaries” in the galleries, guiding and assisting visitors (Kai-Kee, 2011 ).

However, in the early 20th century , competing understandings existed as to whether visitors benefited most from learning how to appreciate the finer qualities of art through visual engagement with the art work alone or from being informed of its history and the processes of creation. This dialectic between aesthetic pleasure and education continues in art museum teaching and learning, manifest in debates ranging from whether there should be interpretation labels in the gallery (Roberts, 2012 ) to the content of talks and workshops in the gallery (Rice, 2003 ) to the role of the museum in society (Dewdney, Dibosa, & Walsh, 2013 ).

Mid-20th-Century Tensions

Despite the educative ambitions ascribed to museums at their inception, from the early 20th century onward curators, which as Cameron noted in 1971 were drawn largely from a middle-class academic elite ( 2012 ) tended to focus on the development and preservation of collections, occupying themselves with scholarly research instead of engaging with a visiting public. Education activities grew erratically and were increasingly centered on support for a wide range of schools provided by specialist educators, commonly in the form of lectures and guided tours through the galleries. In the United Kingdom, some museums even housed schools providing general education during the First World War (Hooper-Greenhill, 1991 ). In the United States, there was a growth in museum-based practical art classes that were extracurricular to school provision for children in the 1920s and 1930s. Influenced by the work of John Dewey, museum educators allied themselves with the ideals of progressive education and sought to instigate nonauthoritarian, cooperative, and informal learning and greater active participation on the part of the learner (see, further, Kai-Kee, 2011 ). It was during this period that key individuals, including Arthur Lismer , who worked at the Art Gallery of Ontario, in Canada, from 1927 to 1938 , were instrumental in establishing education programs in art museums in North America. Basing his work on democratic principles, Lismer saw art as a form of vision and understanding, and education as a fundamental responsibility of the museum. Likewise, over a long career ( 1937–1969 ) at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, Victor D’Amico implemented wide-ranging programs for adults and children at the museum and exerted a profound influence on the emerging professional field of art-museum education. Yet notwithstanding these innovations at key institutions, education provision for adult visitors declined in both the United Kingdom and America during the mid- 20th century .

Overall, this period saw a repositioning and relegation of education programming, which museum directors and curators perceived to be secondary to the collection and preservation of art works (Charman, 2005 ), despite the robust arguments being made at the time for the value of education (Low, 2012 ). Although the status of learning departments has improved since the 1960s, this hierarchical dilemma, arguably, remains in place for education professionals working in art museums today, and it plays out in institutional systems, structures, and funding allocations that locate education as a subsidiary function (Ebitz, 2008 ; Morsch, 2011 ). This is despite the popular discourse of greater museum inclusivity (Serota, 2016 ) and growing calls for museums to be more relevant (Black, 2012b ) and participatory (Simon, 2012 ).

Late 1960s Onward

During the period of social and political unrest in the 1960s, art museums came under pressure from both artists and the broader public, who actively critiqued institutional exclusivity and elitist structures, policies, and practices (Cameron, 2012 ). Shaped by the discourses of the civil rights movement, postcolonialism, feminism, and gay liberation, artists sought to interrogate and reveal the dominant exclusionary practices within cultural organizations (Marstine, 2017 ). Art museums in Europe and the United States, concerned about their social relevance, responded in part by reaching out to artists, inviting them into the institutions to make explicit the hidden hegemonies, a practice that became known as “institutional critique” (Fraser, 2005 ). Simultaneously, yet not always symbiotically, art museums expanded their education programs, introducing or foregrounding teaching methods intended to attract and engage audiences new to the institution.

It is during this period that a split can be identified between two strands of practice that operated concurrently in the United Kingdom and United States. One response to the critiques of museum exclusivity was to focus on expanding education provision and widening audiences, drawing on pedagogic methods devised to encourage participation, creative expression, and skillful looking (Kai-Kee, 2011 ). However, particularly in the United Kingdom (although also in North and South America), educators aligned themselves with the mid-century discourses of liberation (Allen, 2008 ) and developed pedagogic practices informed by critical pedagogy, most notably, the writings of Paulo Freire and Augusto Boal. In Britain, these practices were, in turn, informed by the burgeoning community arts movement, which was itself driven by an ambition to democratize art practices and address issues, challenge societal structures, and bring about change (Dickson, 1995 ). In the United States, the Works Program Administration in the 1930s—in particular, the Federal Arts Project, which employed artists as teachers—provided a historic legacy for artists to draw on in reframing the social and political role of art-museum education.

Informed by artists including Joseph Beuys, Alan Kaprow, Judy Chicago, Mary Kelly and Jo Spence, this more radical and democratic strand of gallery education developed in the 1970s and 1980s in the United Kingdom and the United States and, subsequently, in mainland Europe (see Morsch, 2011 ). Art museum education became a means by which artists and educators sought to agitate with and advocate on behalf of those members of the public who were unrepresented in mainstream art institutions by surfacing hidden histories and lobbying for change. Led by practicing artists working in the museum, teaching and learning was characterized by a belief in the cultural potential of everyone and empowerment through participation in a democratic creative and critical process (Pringle, 2006 ). Thus, though the general motivations for the practice, on both sides of the Atlantic, came from a desire to demystify the art museum as an institution and enable broader audiences to learn from art and generate new meanings and understanding, one strand of the discourse was more overtly concerned with using art for critical and emancipatory purposes.

During this period, the ambition to open up the cultural institution and democratize art and culture was realized outside the museum, notably through television programs. These included John Berger’s 1972 series Ways of Seeing , which broadcast initially in the United Kingdom on BBC2, went on to be shown around the world, and then was reformulated as a book (Berger, 1972 ). Informed by Marxism, the program was intended in part to be a response to the BBC’s earlier and more traditional series Civilization that had set out to present a canonical view of art history. As such, Ways of Seeing adopted a critical perspective toward art and aesthetics, in dialogue with the field of visual culture and what was being called the “new art history” (Harris, 2001 ). Its impact was felt in the art-museum sector, where it helped shape, for example, the structure and philosophy of workshop programs for schools at Tate (Charman, Rose, & Wilson, 2006 ) and provided the visiting public with critical tools for deconstructing the visual image.

The relationship with television has continued, and the one with digital technology has become increasingly reciprocal. Museums, operating much as broadcast media, have exploited television and the Internet to raise the profile of their collections and communicate with their audiences. Not all of these activities are necessarily designed or implemented by education departments in museums, but they are among the strategies museums employ to connect with, engage, and, to some degree, educate their visitors.

Pedagogic Agendas and Ambitions

Over the last 100 years teaching and learning in the art museum has embraced a plethora of agendas, each of which continues to shape contemporary practice. On one level, the history of art-museum education can be understood as a dialogue between collection-centered pedagogy, where the remit is to help the public understand the curated displays, and exhibitions and learner-centered practices, where the responsibility is to enable visitors to generate their own meanings of the art works. Yet within this dialectic exist multiple more-nuanced ambitions, including, on the one hand, the desire to invoke a largely unmediated aesthetic experience centered on the formal qualities of the art, contrasted with, on the other hand, the ambition to transmit predetermined art historical information.

Morsch ( 2011 ) attempted a categorization of the four dominant discourses of art museum education, based on how it fulfills various institutional “functions.” In the first of these, museum education is identified as “affirmative” when it services the museum’s mission in terms of promoting cultural heritage to an already informed and interested audience. It functions in a “reproductive” capacity when it brings in children, young people, and others unfamiliar with the institution, replicating the skills and knowledge the museum specialists consider necessary for understanding the exhibits and engendering a broad interest in art. Morsch and others are critical of both approaches for their perceived lack of self-reflexivity, for reinforcing existing relationships of power, and for entrenching art museums as social and “political” institutions carrying out ideological functions (Duncan, 1995 ). In the context of the art museum, education is thus cast as a means of inculcating the other into a middle-class habitus (Bourdieu, 1979 ). Pedagogy amounts to no more than enabling individuals to “make the correct (posh) noises . . . a kind of etiquette which will allow us not to make fools of ourselves in the appropriate social circumstances” (Harrison, 1984 , p. 10). This process, in which the scope for challenging the institution and dominant discourses is limited, can be seen as coercive, akin to Bourdieu’s ( 1979 ) concept of “symbolic violence,” which describes the nonviolent imposition by a dominant class of its systems of meaning, or culture, onto a subordinated group, who, by perceiving the dominant class’s actions as legitimate, become complicit in their own subordination (Pringle, 2011 ).

An alternate formulation frames these competing ambitions as a tension between “democratizing culture,” the art museum’s drive to communicate its knowledge and values in forms that neither expect nor invite debate, and “cultural democracy,” which sees the museum as seeking to enable individuals to develop creative and critical skills and articulate their own cultural expressions in ways that may not align with those sanctioned by the cultural institution (Kelly, 1985 ). In practice, museum educators negotiate between the institution and the collection and simultaneously respond to the needs of audiences by drawing on a range of methodologies and disciplines. For example, with audiences very new to art, the focus might be on teaching skills that build confidence and can be applied beyond the context of the gallery, such as visual awareness and critical thinking. Yet this arguably more culturally democratic approach would not preclude the same educator from communicating the sociocultural and art historical specificity of art works as embodiments of aesthetic, historical, and cultural values should the pedagogic context require it.

Cultural democracy can be allied with the third of Morsch’s “functions” for gallery education. “Deconstructive” museum-education practices work to enable participants to question embedded and frequently invisible assumptions in art and art museums (Morsch, 2011 ). Associated with critical museological practice, in that it is characterized by a critique of objects and institutional practices (Vergo, 1989 ), and with critical pedagogy, in that it fosters a self-reflective understanding of education, teaching and learning practice, this scenario includes a reflexive examination of power relations to promote critique and self-empowerment. In this, it seeks to transform the institution into a space in which those who are not at the center of the art world can generate their own meanings and representations of art.

This critical practice has itself been subject to criticism, in part by art-museum-education professionals who are conscious of the extent to which the cultural institution is genuinely open to critical deconstruction, given that it sets the agenda for these practices (Morsch, 2011 ; Pringle & De Witt, 2014 ). Further criticism has addressed the question of who benefits from the processes of institutional critique. Ebitz ( 2008 ) and Cutler ( 2013 ), for example, recognize that critical practice can help reveal institutional hierarchies and enable education to define itself within the institution. Cutler, however, warns that a focus on discourses of power can overwhelm a discourse of learning and does little to provide meaningful and more productive alternatives. Critical practice in her view also firmly locates education at the margins of the institution, thereby limiting its scope to bring about “the possibility for new and different articulations” (Cutler, 2013 ).

Despite the obvious contradictions that are present in these agendas, underlying them all is the awareness that art museums have a responsibility to support everyone (from the art novice to the expert) to learn with, from and about art, and that this learning brings about positive intellectual and emotional changes in individuals that can also benefit society. This idea was originally manifested in the paternalistic view that art “improves” people, both morally and intellectually. Arguably, the residue of this questionable discourse of “improvement” remained throughout the 20th and continues into the 21st century . It is apparent in the language used by programs that seek to address issues of social exclusion or to transform “problem” young people through access to art (see Buckingham & Jones, 2001 ). This is despite efforts on the part of art-museum-education professionals and academics to challenge language and practices that reinforce traditional relations between the museum and “others” (Sandell, 2002 ).

At the same time, this “transformational” discourse, which equates to the fourth and final of Morsch’s “functions,” can be seen to inform critical and liberatory education programs that seek to address inequalities and bring about social and institutional change. Education departments have a strong history as agents of change and sites of debate and experimental practice in art museums, underpinned by research. Tate Exchange, for example, is a three-year initiative, instigated at Tate in 2016 under the auspices of a learning department, that seeks to examine the role of art in relation to broader societal systems and structures, and specifically, to better understand how art makes a difference in people’s lives and, through that, to society more widely (see https://www.tate.org.uk/visit/tate-modern/tate-exchange ). Likewise, the MASS Action (Museum as Site for Social Action) initiative convened by learning staff at the Minneapolis Institute of Art asks how the museum can be used as a site for social action. And programs including the Edgeware Road project, instigated by the education department at the Serpentine Gallery in London are challenging institutional modes of knowledge production. These initiatives raise questions about whether it is the responsibility of the education department alone or of the art museum as a whole to effect social change (Black, 2012b ). And though the shift toward art museums becoming more community centered, “representing multiple perspectives, and exploring the relevance of the past to people’s lives today” (Black, 2012a , p. 267), has, in theory, positive implications for the role of education, the question arises, if the museum is framed in its entirety as a learning organization, should education departments be disbanded (Cutler, 2010 )? Art-museum educators, and their colleagues in the institution and beyond, need to further investigate how pedagogy working alongside curatorial programming and interpretation can contribute to a culture of dialogue and debate. How can learning departments act as drivers for ethical change in the museum and beyond? What role should education play in a 21st-century art museum committed to inclusivity and toleration?

Contemporary Practice

Shaped by these agendas, and frequently manifesting more than one of them concurrently, contemporary teaching and learning practice in the art museum takes a multitude of forms. These include informal visits to galleries by schools, families, and community groups, supported by learning resources that range from in-gallery interpretation wall texts, paper-based worksheets, and bespoke objects that can be handled in the gallery to audio guides and digital interventions and materials.

The offer to school groups includes professional development programs for teachers that take shape as lectures, workshops, and courses, some of which provide academic accreditation. However, the most common provision for schools involves one-off structured teaching sessions in the gallery led by an educator or, frequently in the United States, a docent. In the United Kingdom, participatory, artist-led workshops in the gallery have been a staple of gallery education practice for the last 40 years. Longer-term projects with schools may involve a combination of gallery and classroom-based programs. These focus on developing specific learning skills and include the VTS (Visual Thinking Strategies) program in the United States and creative learning initiatives in the United Kingdom that nurture ways of thinking and working that encourage imagination, independence, tolerance of ambiguity and risk, openness, and the raising of aspirations (Pringle, 2012 ). A strong tradition of schools-focused programs that directly address issues of racism or bullying, for example, also exist. And notably, given the current radically conservative sociopolitical climate in the United States and the United Kingdom, there are increasing calls from the art-museum-education sector for the profession to redouble its efforts to counter discrimination by working alongside individuals, schools, and communities. For example the Journal of Museum Education devoted an entire issue in June 2017 to ‘identifying and transforming racism in museum education’ ( Identifying and Transforming Racism in Museum Education, Journal of Museum Education ).

Structured programs for adults commonly range from lectures, conferences, and in-gallery talks designed with the specialist art audience in mind to courses and informal programming intended to attract a more-diverse public. Longer-term projects, in which artists work in and beyond the gallery with communities, frequently to address specific social issues, are common in the United Kingdom (Marstine, 2017 ), the United States (Finkelpearl, 2013 ), and across Europe, South America, and Australia. However, this practice appears to be relatively under-researched, particularly as it exists beyond the familiar art-world centers, and would benefit from a comprehensive survey. Recognition that the art museum can engender improvements in health and well-being (see the Engage , 39 : Visual Arts and Wellbeing , Spring 2017 ) has prompted the instigation of programs such as those for adults with dementia, a well-known example being the Meet Me at MoMA program. Moreover, the research-led imperative of art-museum education is evident in such projects as The Center for Empathy and the Visual Arts that has been established at the Minneapolis Institute of Art . These include a five-year study that researches practices that foster compassion and enhance related emotional skills, with the goal to inform the design of leaning and engagement programs.

Overlaps can be seen between what has become defined as “socially engaged practice” (see, further, Bishop, 2012 ; Finkelpearl, 2013 ; Kester, 2004 ) and artists working under the auspices of museum education, not least in a shared commitment to engagement through creative dialogue. Similarly, the so-called educational turn in art and curatorial practice has drawn attention to the pedagogic potential in both (O’Neill & Wilson, 2010 ). Yet it is noticeable that art-museum education has been conspicuously absent from these discursive fields, which to some educators is evidence of long-standing prejudices, misconceptions, and entrenched hierarchies (Mahlknecht, 2017 ).

The conflation of different museum-based practices, often to the detriment of education, reinforces the importance of articulating the histories, ambitions, and practices of teaching and learning and acknowledging the specificity of pedagogy in the art museum. Understanding whom it is for, how the pedagogic relationships are structured, and what constitutes success is essential for the development of the field. For example, programs targeted at young people or “teens,” aged usually between 15 and 25, are growing in popularity. Varying in scope and ambition, these initiatives range from those aiming for audience diversification and professional development and training to programs seeking to engender cultural empowerment and critical practice in their young participants. And while research has been undertaken on the nature of participation and the impact of teenage engagement with art museums (see, e.g., Hirzy, 2015 ; Sayers, 2011 ), further work is required.

Art museums are becoming increasingly adept at using digital media for education purposes. Social media platforms provide opportunities to break down formal communication barriers and share information. Podcasts of gallery talks are now a regular offering, and the larger institutions have gone further, in some cases providing online courses for the general public and professional development programs for teachers (Armstrong, Howes, & Woon, 2013 ). Designated spaces, such as the Taylor Digital Studio at Tate Britain in London, allow for targeted programming and the facilitation of courses and events utilizing digital technology in the gallery. Yet research has indicated that art museums are struggling to move beyond the one-to-many broadcast model and take full advantage of the many-to-many model of networked and distributed digital communication, whereby knowledge is generated and shared through less hierarchical channels (Walsh, Dewdney, & Pringle, 2016 ). This suggests that further research interrogating the specific affordances of the digital in the context of art-museum education would be of value.

Art Museum Epistemology and Pedagogy

Considering the range of activities and ambitions for learning in the art museum, it comes as no surprise that that the practice today is informed by a variety of disciplines and intellectual traditions, most notably sociology, cognitive and developmental psychology, critical pedagogy, progressive education, critical theory, art history, philosophy, and anthropology. Indeed, one characteristic of the art-museum educator is the ability to shift among disciplinary persona (being at certain points a philosopher, artist, art historian, or critic) in response to the needs of the learner (Rice, 1988 ). Art-museum educators draw on the work of a range of key thinkers and writers, adapting ideas and pedagogic techniques to work effectively in the gallery context. For example, John Dewey’s writings on the experience of art continue to inspire museum educators seeking to engender for visitors the intense and engaged encounter he described (Burnham & Kai-Kee, 2011 ). Dewey’s framing of education as experiential, social, and learner centered, driven by problem-solving and critical thinking to prepare the student for engagement in civic life (Dewey, 1897 ) also underpins education activity in museums today.

In the United States, research with practitioners has identified that museum educators reference psychological theories of learning, including Howard Gardner’s work on multiple intelligences and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s theory of flow (Ebitz, 2008 ). Also influential is the work of developmental psychologists Jean Piaget and Lev Vygotsky, whose work in particular informed the widely used visual thinking strategies (VTS) model developed by psychologist Abigail Housen and former museum educator Philip Yenawine. VTS’s recognition of the centrality of the learner is allied to constructivist learning theory, wherein learners are identified as active and learning is constructed as a process of individual sense-making in which learners build on their existing knowledge and experiences to generate new understandings (Watkins, 2003 ). Constructivism locates the museum object as devoid of inherent meaning; instead, the meaning is generated through the visitor’s engagement with the artefact (Hein, 1998 ). Teachers are positioned as expert facilitators, whose role is to ask questions and facilitate the learner’s connection to art. In the VTS model, teachers refrain from sharing their own knowledge and experiences, so as not to disempower the learner. The emphasis in VTS on developing critical thinking skills through attentive looking seeks to enable visitors to develop the skills necessary to generate their own understandings. The model has, however, been criticized for failing to draw viewers’ attention to the historical or social conditions of a work and for denying the expertise of the curators and educators, thereby promoting a sense that every interpretation is of equal value (Rice & Yenawine, 2002 ). Further criticism centers on the need to acknowledge the social and cultural frameworks that shape individual interpretations, instead of focusing exclusively on the individual (see Kai-Kee, 2011 ; Hooper-Greenhill, 1999 ; Rice & Yenawine, 2002 ). Nonetheless, the VTS model is perceived to be particularly effective in supporting younger students and those who have less familiarity with art to engage with art and develop confidence in connecting with the art museum.

Notwithstanding a focus in recent years on constructivist teaching and learning, “traditional” (Hein, 1998 ) or transmissive models of teaching and learning can be found in art museums across the world. In the traditional scenario, learners are identified as passive and are given knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values by an expert (Watkins, 2003 ). The content of learning exists independently of the learner and is transferred to him or her through a process of assimilating facts, information, and experience, most commonly in the art museum in the form of talks or lectures, or through texts, such as exhibition catalogues. In practice, educator-led sessions in the gallery frequently combine both constructivist and transmissive elements. Educators guide learners using a combination of questioning to support individual meaning making and deploying their knowledge at key moments to enrich the overall learning experience (Burnham & Kai-Kee, 2011 ; Pringle & De Witt, 2014 ; Rice, 1988 ; Thomson, 2014 ).

In the United Kingdom, art practice is perceived to be central to teaching and learning, particularly in the modern and contemporary art museum. Art practice (instead of constituting a particular pedagogic model) is where artists, participants, and issues meet; and though it is not widely documented, there is evidence that the principles of the community-arts movement remain at the center of much education work today (Allen, 2008 ; Pringle, 2006 ). Community artists located artistic practice as a means to enter into productive dialogue with nonartistic constituents. However, this is not artistic practice as espoused under a particular understanding of modernism, wherein art is perceived as synonymous with the rebellious antagonist existing in “romantic exile” (Gablik, 1995 , p. 5). Rather, community arts promoted communication, interaction, and engagement to enable participation in the creation of culture, characteristics that are still central to the art-museum learning experience.