To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, research on capital structure determinants: a review and future directions.

International Journal of Managerial Finance

ISSN : 1743-9132

Article publication date: 3 April 2017

The purpose of this paper is to study the status of studies on capital structure determinants in the past 40 years. This paper highlights the major gaps in the literature on determinants of capital structure and also aims to raise specific questions for future research.

Design/methodology/approach

The prominence of research is assessed by studying the year of publication and region, level of economic development, firm size, data collection methods, data analysis techniques and theoretical models of capital structure from the selected papers. The review is based on 167 papers published from 1972 to 2013 in various peer-reviewed journals. The relationship of determinants of capital structure is analyzed with the help of meta-analysis.

Major findings show an increase of interest in research on determinants of capital structure of the firms located in emerging markets. However, it is observed that these regions are still under-examined which provides more scope for research both empirical and survey-based studies. Majority of research studies are conducted on large-sized firms by using secondary data and regression-based models for the analysis, whereas studies on small-sized firms are very meager. As majority of the research papers are written only at the organizational level, the impact of leverage on various industries is yet to be examined. The review highlights the major determinants of capital structure and their relationship with leverage. It also reveals the dominance of pecking order theory in explaining capital structure of firms theoretically as well as statistically.

Originality/value

The paper covers a considerable period of time (1972-2013). Among very few review papers on capital structure research, to the best of authors’ knowledge; this is the first review to identify what is missing in the literature on the determinants of capital structure while offering recommendations for future studies. It also synthesize the findings of empirical studies on determinants of capital structure statistically.

- Literature review

- Meta-analysis

- Capital structure

- Pecking order

Kumar, S. , Colombage, S. and Rao, P. (2017), "Research on capital structure determinants: a review and future directions", International Journal of Managerial Finance , Vol. 13 No. 2, pp. 106-132. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMF-09-2014-0135

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2017, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Determinants of capital structure: a panel regression analysis of Indian auto manufacturing companies

- Research Paper

- Published: 07 August 2021

- Volume 23 , pages 338–356, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- S. Santhosh Kumar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6108-4744 1 &

- C. Bindu 2

600 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Capital Structure denotes the proportion of equities, preference share capital, long-term loans, debentures, retained earnings and other long-term sources of funds for business. The cost of these sources of funds, their tax advantages and legal implications are varied. The impact of these sources of funds on the value of the business is also different. Thus, the decision regarding the mix of different sources of funds in the capital structure is a challenging one for the practicing financial managers. The conventional theories of capital structure factored in some unrealistic assumptions to prove their propositions. But, in practice, there are a number of firm specific factors along with other quantifiable and non-quantifiable factors are influencing the capital structure decision of companies. This is an attempt to identify the firm specific factors influencing the capital structure decision of automobile manufacturing companies in India. The study employed panel regression analysis to identify the firm specific factors. Two variants of capital structure ratio such as Long-term Debt to Total Assets and Long-term Debt to Equity are tried in the panel data. It is found that firm size, profitability, tangibility, growth in assets and interest coverage are jointly influencing the capital structure decision of the auto companies.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The impact of corporate governance on financial performance: a cross-sector study

Wajdi Affes & Anis Jarboui

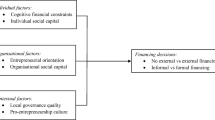

Formal and informal financing decisions of small businesses

Bach Nguyen & Nguyen Phuc Canh

ESG Disclosure, REIT Debt Financing and Firm Value

Zifeng Feng & Zhonghua Wu

Ahmeti F (2015) A critical review of modigliani and miller’s theorem of capital structure. Int J Econ Commer Manag 3(6):47–52

Google Scholar

Ahmed R (2012) Determinants of capital structure: a case study of automobile manufacturing companies listed in NSE. Int J Financ Serv Manag 1(4):47–52

Ai-Ajmi J, Hussain HA, Al-Saheh N (2009) Decisions on capital structure in a Zakat environment with prohibition of riba: the case of Saudi Arabia. J Risk Finance 10(5):460–476

Article Google Scholar

Amsaveni R, Gomathi S (2010) A study of pharmaceutical industry in India. Indian J Finance 6(3):1–13

Ashraf T, Rasool S (2013) Determinants of leverage of automobile sector firms listed in karachi stock exchange by testing packing order theory. J Bus Stud Q 4(3):73–83

Awan TN, Rashid M, Zia-ur-Rehman M (2011) Analysis of the determinants of Capital Structure in sugar and allied industry. Int J Bus Soc Sci 2(1):221–229

Babu N, Chalam GV (2016) Capital structure and its determinants of automobile companies in India: an empirical analysis. EPRA Int J Econ Bus Rev 4(7):2349–3187

Basu K, Rajeev M (2013) Determinants of capital structure of indian corporate sector: evidence of regulatory impact. Working Paper 306. The Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore. http://isec.ac.in/WP%20306%20-%20Kaushik%20Basu%20and%20Meenakshi%20Rajeev.pdf . Accessed 10 April 2021

Bhaduri SN (2002) Determinants of corporate borrowing: some evidence from the Indian corporate structure. J Econ Finance 26(2):200–215

Bhole LM, Mahakud J (2004) Trends and determinants of corporate capital structure in India: a panel data analysis. Finance India 18(1):37–55

Booth L, Aivazian V, Demrguc-Kunt A, Maksimovic V (2001) Capital structures in developing countries. J Financ 27(4):539–560

Brigham EF, Daves PR (2007) Intermediate financial management. Thomson South-Western, Mason

Cekrezi A (2013) Impact of firm specific factors on capital structure decision: an empirical study of albanian firms. Eur J Sustain Dev 2(4):135–148

Chen S-Y, Chen L-J (2011) Capital structure determinants: an empirical study in Taiwan. Afr J Bus Manage 5(27):10974–10983

Das S, Roy M (2007) Inter-industry differences in capital structure: evidence from India. Finance India 21:517

Demirguc-Kunt A, Maksimovic V (1999) Institutions, financial markets, and firm debt maturity. J Financ Econ 54(3):295–336

Dogra B, Gupta S (2009) An empirical study on capital structure of SMEs in Punjab. Icfai J Appl Finance 15(3):60–80

Durand D (1952) The cost of debt and equity fund for business. In: Solomon E (ed) Management of corporate capital. The Free Press, New York, pp 91–116

Eldhose KV, Kumar S (2019) Determinants of financial leverage: an empirical analysis of manufacturing companies in India. Indian J Finance 13(7):41–49

Eriotis N, Vasiliou D, Ventoura-Neokosmidi Z (2007) How firm characteristics affect capital structure: an empirical study. Manag Financ 33(5):321–331

Frank MZ, Goyal VK (2009) Capital structure decisions: which factors are reliably important? Financ Manage 38(1):1–37

Gifford D (1998) After the revolution: forty years ago, the Modigliani-Miller propositions started anew era in corporate finance. How does M&M hold up today? CFO Publishing Corporation: http://pages.stern.nyu.edu/~adamodar/New_Home_Page/articles/MM40yearslater.htm . Accessed 2020

Hackbarth D, Hennessy CA, Leland HE (2007) Can the trade-off theory explain debt structure? Rev Financ Stud 20(5):1389–1428

Harris M, Raviv A (1991) The theory of capital structure. J Finance 46(1):297–355. https://doi.org/10.7763/IJIMT.2010.V1.24

Hanousek J (2011) A stubborn persistence: Is the stability of leverage ratios determined by the stability of the economy? J Corp Finan 17(5):1360–1376

IBEF (2019) Automobile industry in India. www.ibef.org . Accessed 2019

Indi R (2015) Determinants of capital structure in Indian automobile companies: a case of Tata motors and Ashok leyland. J Contemp Res Manag 3:8–14

JagannathanSuresh UKN (2017) The nature and determinants of capital structure in Indian service firms. Indian J Finance 11(11):3–043

Jensen MC, Meckling WH (1976) Theory of the firm: managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J Financ Econ 3(4):305–360

Juniarti R, Utami S (2017) The determinants of capital structure of manufacturing companies listed in LQ45 index in indonesia stock exchange period 2010–2014. Int J Adv Res Manag Soc Sci 6(1):29–48

Kester WC (1986) Capital and ownership structure: a comparison of united states and japanese manufacturing corporations. Financ Manage 15(1):5–16

Khan MY, Jain PK (2019) Financial management, 8th edn. McGraw Hill Education (India) Pvt Ltd

Korajczyk RA, Levy A (2003) Capital structure choice: macroeconomic conditions and financial constraints. J Finan Econ 68(1):75–109

Kraus A, Litzenberger RH (1973) A State-preference model of optimal financial leverage. J Financ 28(4):911–922

Kumar SS, Bindu C (2018) Determinants of capital structure: an exclusive study of passenger car companies in India. Indian J Finance 12(5):43–53

Luigi P, Sorin V (2009) A review of the capital structure theories. Ann Fac Econ 3(1):315–320

Madan K (2007) An analysis of the debt-equity structure of leading hotel chains in India. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 19(5):397–414

Mittal S, Kumari L (2015) Effect of determinants of capital structure on financial leverage: A study of selected indian automobile companies. J Commer Account Res 4(3 and 5):70–75

Modigliani F, Miller M (1963) Taxes and the cost of capital: a correction. Am Econ Rev 53:433–443

Modigliani F, Miller MH (1958) The cost of capital, corporate finance and the theory of investment. Am Econ Rev 48:261–296

Modugu KP (2013) Capital structure decision: an overview. J Finance Bank Manag 1(1):14–27

Muller S (2015) Determinants of capital structure: evidence from the German market. Netherlands: University of Twente. http://essay.utwente.nl/67410/1/M%C3%BCller_BA_MB.pdf

Myers SC (1977) Determinants of capital borrowing. J Finance Econ 5:5147–5175

Myers SC (1984) The capital structure puzzle. J Financ 39(3):574–592

Myers SC, Majluf NM (1984) Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have Information that Investors do not have. J Financ Econ 13(2):187–221

Nenu EA, Vintila G, Gherghina SC (2018) The impact of capital structure on risk and firm performance: empirical evidence for the bucharest stock exchange listed companies. Int J Financ Stud 6(41):1–9

Ozkan A (2001) Determinants of capital structure and adjustment to long run target: evidence from UK company panel data. J Bus Financ Acc 28(1–2):175–198

Pandey IM (2005) Capital structure, profitability and market structure: evidence from Malaysia. Asia Pacific J Econ Bus 8(2):78–91

Pandey IM (2010) Financial management, 10th edn. Vikas Publishing Pvt Ltd

Pinkova P (2012) Determinants of capital structure: evidence from the Czech automotive industry. ACTA Universitatis Agriculturae Et Silviculturae Mendeliane Brunensis, LX 7:217–224

Poddar N, Mittal M (2014) Capital structure determinants of steel companies in India: a panel data analysis. Int Interdiscip Res J 2(1):144–158

Rajan RG, Zingales L (1995) What do we know about capital structure? Some evidence from international data. J Financ 50(5):1421–1460

Ross SA (1977) The determination of financial structure: the incentive-signalling approach. Bell J Econ 8:23–40

Sahoo SM, Omkarnath G (2005) Capital structure of Indian private corporate sector: an empirical analysis. IUP J Appl Finance 11:40–56

SESEI (2018) Indian automobile industry. www.sesei.eu . Accessed April 2020

Sheikh NA, Wang Z (2010) Financing behavior of textile firms in Pakistan. Int J Innov Manag Technol 1(2):130–135

Sofat R, Singh S (2017) Determinants of capital structure: an empirical study of manufacturing firms in India. Int J Law Manag 59(6):1029–1045

Suhaila MK, Mahmood WM (2008) Capital structure and firm characteristics: some evidence from Malaysian Companies. (Paper No. 14616). Munich Personal RePEc Archive

Talberg M, Winge C, Frydenberg S, Westgaard S (2008) Capital structure across industries. Int J Econ Bus Stud 15:181–200

Titman S, Wessels R (1988) The determinants of capital structure choice. J Financ 43(1):1–19

Yadav CS (2014) Determinants of capital structure and financial leverage: evidence of select Indian companies. Asia Pacific J Res 1(12):121–130

Download references

No funding is provided for the preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Management Studies, Cochin University of Science and Technology, Kochi, Kerala, 682 022, India

S. Santhosh Kumar

Sree Narayana College, Cherthala, Kerala, India

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to S. Santhosh Kumar .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Santhosh Kumar, S., Bindu, C. Determinants of capital structure: a panel regression analysis of Indian auto manufacturing companies. J. Soc. Econ. Dev. 23 , 338–356 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-021-00159-9

Download citation

Accepted : 21 June 2021

Published : 07 August 2021

Issue Date : December 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40847-021-00159-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Capital structure

- Automobile industry

- Panel regression

- Debt-equity ratio

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Browse content in A - General Economics and Teaching

- Browse content in A1 - General Economics

- A12 - Relation of Economics to Other Disciplines

- A13 - Relation of Economics to Social Values

- A14 - Sociology of Economics

- Browse content in B - History of Economic Thought, Methodology, and Heterodox Approaches

- Browse content in B2 - History of Economic Thought since 1925

- B26 - Financial Economics

- Browse content in C - Mathematical and Quantitative Methods

- Browse content in C1 - Econometric and Statistical Methods and Methodology: General

- C11 - Bayesian Analysis: General

- C12 - Hypothesis Testing: General

- C13 - Estimation: General

- C15 - Statistical Simulation Methods: General

- Browse content in C2 - Single Equation Models; Single Variables

- C21 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions

- C22 - Time-Series Models; Dynamic Quantile Regressions; Dynamic Treatment Effect Models; Diffusion Processes

- C24 - Truncated and Censored Models; Switching Regression Models; Threshold Regression Models

- Browse content in C3 - Multiple or Simultaneous Equation Models; Multiple Variables

- C32 - Time-Series Models; Dynamic Quantile Regressions; Dynamic Treatment Effect Models; Diffusion Processes; State Space Models

- C35 - Discrete Regression and Qualitative Choice Models; Discrete Regressors; Proportions

- Browse content in C4 - Econometric and Statistical Methods: Special Topics

- C40 - General

- C43 - Index Numbers and Aggregation

- C44 - Operations Research; Statistical Decision Theory

- Browse content in C5 - Econometric Modeling

- C51 - Model Construction and Estimation

- C52 - Model Evaluation, Validation, and Selection

- C53 - Forecasting and Prediction Methods; Simulation Methods

- C58 - Financial Econometrics

- Browse content in C6 - Mathematical Methods; Programming Models; Mathematical and Simulation Modeling

- C61 - Optimization Techniques; Programming Models; Dynamic Analysis

- C62 - Existence and Stability Conditions of Equilibrium

- C63 - Computational Techniques; Simulation Modeling

- Browse content in C7 - Game Theory and Bargaining Theory

- C71 - Cooperative Games

- C72 - Noncooperative Games

- C78 - Bargaining Theory; Matching Theory

- Browse content in C9 - Design of Experiments

- C91 - Laboratory, Individual Behavior

- C92 - Laboratory, Group Behavior

- Browse content in D - Microeconomics

- Browse content in D0 - General

- D01 - Microeconomic Behavior: Underlying Principles

- D02 - Institutions: Design, Formation, Operations, and Impact

- D03 - Behavioral Microeconomics: Underlying Principles

- Browse content in D1 - Household Behavior and Family Economics

- D10 - General

- D12 - Consumer Economics: Empirical Analysis

- D14 - Household Saving; Personal Finance

- D15 - Intertemporal Household Choice: Life Cycle Models and Saving

- Browse content in D2 - Production and Organizations

- D21 - Firm Behavior: Theory

- D22 - Firm Behavior: Empirical Analysis

- D24 - Production; Cost; Capital; Capital, Total Factor, and Multifactor Productivity; Capacity

- Browse content in D3 - Distribution

- D31 - Personal Income, Wealth, and Their Distributions

- Browse content in D4 - Market Structure, Pricing, and Design

- D40 - General

- D43 - Oligopoly and Other Forms of Market Imperfection

- D44 - Auctions

- D46 - Value Theory

- D49 - Other

- Browse content in D5 - General Equilibrium and Disequilibrium

- D50 - General

- D51 - Exchange and Production Economies

- D52 - Incomplete Markets

- D53 - Financial Markets

- Browse content in D6 - Welfare Economics

- D61 - Allocative Efficiency; Cost-Benefit Analysis

- D62 - Externalities

- D64 - Altruism; Philanthropy

- Browse content in D7 - Analysis of Collective Decision-Making

- D72 - Political Processes: Rent-seeking, Lobbying, Elections, Legislatures, and Voting Behavior

- D73 - Bureaucracy; Administrative Processes in Public Organizations; Corruption

- D74 - Conflict; Conflict Resolution; Alliances; Revolutions

- Browse content in D8 - Information, Knowledge, and Uncertainty

- D80 - General

- D81 - Criteria for Decision-Making under Risk and Uncertainty

- D82 - Asymmetric and Private Information; Mechanism Design

- D83 - Search; Learning; Information and Knowledge; Communication; Belief; Unawareness

- D84 - Expectations; Speculations

- D85 - Network Formation and Analysis: Theory

- D86 - Economics of Contract: Theory

- D87 - Neuroeconomics

- Browse content in D9 - Micro-Based Behavioral Economics

- D91 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making

- D92 - Intertemporal Firm Choice, Investment, Capacity, and Financing

- Browse content in E - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Browse content in E1 - General Aggregative Models

- E12 - Keynes; Keynesian; Post-Keynesian

- E13 - Neoclassical

- E17 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E2 - Consumption, Saving, Production, Investment, Labor Markets, and Informal Economy

- E21 - Consumption; Saving; Wealth

- E22 - Investment; Capital; Intangible Capital; Capacity

- E23 - Production

- E24 - Employment; Unemployment; Wages; Intergenerational Income Distribution; Aggregate Human Capital; Aggregate Labor Productivity

- Browse content in E3 - Prices, Business Fluctuations, and Cycles

- E31 - Price Level; Inflation; Deflation

- E32 - Business Fluctuations; Cycles

- E37 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E4 - Money and Interest Rates

- E41 - Demand for Money

- E42 - Monetary Systems; Standards; Regimes; Government and the Monetary System; Payment Systems

- E43 - Interest Rates: Determination, Term Structure, and Effects

- E44 - Financial Markets and the Macroeconomy

- E47 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E5 - Monetary Policy, Central Banking, and the Supply of Money and Credit

- E51 - Money Supply; Credit; Money Multipliers

- E52 - Monetary Policy

- E58 - Central Banks and Their Policies

- Browse content in E6 - Macroeconomic Policy, Macroeconomic Aspects of Public Finance, and General Outlook

- E60 - General

- E61 - Policy Objectives; Policy Designs and Consistency; Policy Coordination

- E62 - Fiscal Policy

- E64 - Incomes Policy; Price Policy

- E65 - Studies of Particular Policy Episodes

- Browse content in F - International Economics

- Browse content in F0 - General

- F02 - International Economic Order and Integration

- Browse content in F1 - Trade

- F11 - Neoclassical Models of Trade

- F15 - Economic Integration

- Browse content in F2 - International Factor Movements and International Business

- F21 - International Investment; Long-Term Capital Movements

- F22 - International Migration

- F23 - Multinational Firms; International Business

- Browse content in F3 - International Finance

- F30 - General

- F31 - Foreign Exchange

- F33 - International Monetary Arrangements and Institutions

- F34 - International Lending and Debt Problems

- F36 - Financial Aspects of Economic Integration

- F37 - International Finance Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- F38 - International Financial Policy: Financial Transactions Tax; Capital Controls

- F39 - Other

- Browse content in F4 - Macroeconomic Aspects of International Trade and Finance

- F41 - Open Economy Macroeconomics

- F42 - International Policy Coordination and Transmission

- F44 - International Business Cycles

- Browse content in F6 - Economic Impacts of Globalization

- F65 - Finance

- Browse content in G - Financial Economics

- Browse content in G0 - General

- G00 - General

- G01 - Financial Crises

- G02 - Behavioral Finance: Underlying Principles

- Browse content in G1 - General Financial Markets

- G10 - General

- G11 - Portfolio Choice; Investment Decisions

- G12 - Asset Pricing; Trading volume; Bond Interest Rates

- G13 - Contingent Pricing; Futures Pricing

- G14 - Information and Market Efficiency; Event Studies; Insider Trading

- G15 - International Financial Markets

- G17 - Financial Forecasting and Simulation

- G18 - Government Policy and Regulation

- G19 - Other

- Browse content in G2 - Financial Institutions and Services

- G20 - General

- G21 - Banks; Depository Institutions; Micro Finance Institutions; Mortgages

- G22 - Insurance; Insurance Companies; Actuarial Studies

- G23 - Non-bank Financial Institutions; Financial Instruments; Institutional Investors

- G24 - Investment Banking; Venture Capital; Brokerage; Ratings and Ratings Agencies

- G28 - Government Policy and Regulation

- G29 - Other

- Browse content in G3 - Corporate Finance and Governance

- G30 - General

- G31 - Capital Budgeting; Fixed Investment and Inventory Studies; Capacity

- G32 - Financing Policy; Financial Risk and Risk Management; Capital and Ownership Structure; Value of Firms; Goodwill

- G33 - Bankruptcy; Liquidation

- G34 - Mergers; Acquisitions; Restructuring; Corporate Governance

- G35 - Payout Policy

- G38 - Government Policy and Regulation

- G39 - Other

- Browse content in G4 - Behavioral Finance

- G40 - General

- G41 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making in Financial Markets

- Browse content in G5 - Household Finance

- G50 - General

- G51 - Household Saving, Borrowing, Debt, and Wealth

- Browse content in H - Public Economics

- Browse content in H1 - Structure and Scope of Government

- H11 - Structure, Scope, and Performance of Government

- Browse content in H2 - Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H22 - Incidence

- H23 - Externalities; Redistributive Effects; Environmental Taxes and Subsidies

- H24 - Personal Income and Other Nonbusiness Taxes and Subsidies; includes inheritance and gift taxes

- H25 - Business Taxes and Subsidies

- H26 - Tax Evasion and Avoidance

- Browse content in H3 - Fiscal Policies and Behavior of Economic Agents

- H31 - Household

- Browse content in H4 - Publicly Provided Goods

- H41 - Public Goods

- Browse content in H5 - National Government Expenditures and Related Policies

- H54 - Infrastructures; Other Public Investment and Capital Stock

- Browse content in H6 - National Budget, Deficit, and Debt

- H63 - Debt; Debt Management; Sovereign Debt

- Browse content in H7 - State and Local Government; Intergovernmental Relations

- H74 - State and Local Borrowing

- Browse content in H8 - Miscellaneous Issues

- H81 - Governmental Loans; Loan Guarantees; Credits; Grants; Bailouts

- Browse content in I - Health, Education, and Welfare

- I1 - Health

- Browse content in I2 - Education and Research Institutions

- I26 - Returns to Education

- Browse content in J - Labor and Demographic Economics

- Browse content in J0 - General

- J01 - Labor Economics: General

- Browse content in J1 - Demographic Economics

- J16 - Economics of Gender; Non-labor Discrimination

- Browse content in J2 - Demand and Supply of Labor

- J21 - Labor Force and Employment, Size, and Structure

- J22 - Time Allocation and Labor Supply

- J23 - Labor Demand

- J24 - Human Capital; Skills; Occupational Choice; Labor Productivity

- Browse content in J3 - Wages, Compensation, and Labor Costs

- J31 - Wage Level and Structure; Wage Differentials

- J33 - Compensation Packages; Payment Methods

- Browse content in J4 - Particular Labor Markets

- J41 - Labor Contracts

- Browse content in J5 - Labor-Management Relations, Trade Unions, and Collective Bargaining

- J58 - Public Policy

- J59 - Other

- Browse content in J6 - Mobility, Unemployment, Vacancies, and Immigrant Workers

- J63 - Turnover; Vacancies; Layoffs

- J64 - Unemployment: Models, Duration, Incidence, and Job Search

- J69 - Other

- Browse content in K - Law and Economics

- Browse content in K0 - General

- K00 - General

- Browse content in K1 - Basic Areas of Law

- K12 - Contract Law

- K13 - Tort Law and Product Liability; Forensic Economics

- Browse content in K2 - Regulation and Business Law

- K20 - General

- K21 - Antitrust Law

- K22 - Business and Securities Law

- Browse content in K4 - Legal Procedure, the Legal System, and Illegal Behavior

- K41 - Litigation Process

- K42 - Illegal Behavior and the Enforcement of Law

- Browse content in L - Industrial Organization

- Browse content in L1 - Market Structure, Firm Strategy, and Market Performance

- L11 - Production, Pricing, and Market Structure; Size Distribution of Firms

- L12 - Monopoly; Monopolization Strategies

- L13 - Oligopoly and Other Imperfect Markets

- L14 - Transactional Relationships; Contracts and Reputation; Networks

- L15 - Information and Product Quality; Standardization and Compatibility

- L16 - Industrial Organization and Macroeconomics: Industrial Structure and Structural Change; Industrial Price Indices

- Browse content in L2 - Firm Objectives, Organization, and Behavior

- L20 - General

- L21 - Business Objectives of the Firm

- L22 - Firm Organization and Market Structure

- L23 - Organization of Production

- L25 - Firm Performance: Size, Diversification, and Scope

- L26 - Entrepreneurship

- Browse content in L3 - Nonprofit Organizations and Public Enterprise

- L30 - General

- L31 - Nonprofit Institutions; NGOs; Social Entrepreneurship

- L33 - Comparison of Public and Private Enterprises and Nonprofit Institutions; Privatization; Contracting Out

- Browse content in L4 - Antitrust Issues and Policies

- L41 - Monopolization; Horizontal Anticompetitive Practices

- Browse content in L5 - Regulation and Industrial Policy

- L50 - General

- L51 - Economics of Regulation

- Browse content in L6 - Industry Studies: Manufacturing

- L60 - General

- L8 - Industry Studies: Services

- Browse content in M - Business Administration and Business Economics; Marketing; Accounting; Personnel Economics

- Browse content in M1 - Business Administration

- M12 - Personnel Management; Executives; Executive Compensation

- M13 - New Firms; Startups

- M14 - Corporate Culture; Social Responsibility

- Browse content in M3 - Marketing and Advertising

- M37 - Advertising

- Browse content in M4 - Accounting and Auditing

- M40 - General

- M41 - Accounting

- M48 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in M5 - Personnel Economics

- M52 - Compensation and Compensation Methods and Their Effects

- M55 - Labor Contracting Devices

- Browse content in N - Economic History

- Browse content in N2 - Financial Markets and Institutions

- N20 - General, International, or Comparative

- N22 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- N23 - Europe: Pre-1913

- Browse content in O - Economic Development, Innovation, Technological Change, and Growth

- Browse content in O1 - Economic Development

- O12 - Microeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O15 - Human Resources; Human Development; Income Distribution; Migration

- O16 - Financial Markets; Saving and Capital Investment; Corporate Finance and Governance

- O18 - Urban, Rural, Regional, and Transportation Analysis; Housing; Infrastructure

- Browse content in O2 - Development Planning and Policy

- O23 - Fiscal and Monetary Policy in Development

- O25 - Industrial Policy

- Browse content in O3 - Innovation; Research and Development; Technological Change; Intellectual Property Rights

- O30 - General

- O31 - Innovation and Invention: Processes and Incentives

- O38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in O4 - Economic Growth and Aggregate Productivity

- O40 - General

- Browse content in P - Economic Systems

- Browse content in P1 - Capitalist Systems

- P13 - Cooperative Enterprises

- P16 - Political Economy

- P17 - Performance and Prospects

- Browse content in P2 - Socialist Systems and Transitional Economies

- P22 - Prices

- P24 - National Income, Product, and Expenditure; Money; Inflation

- P26 - Political Economy; Property Rights

- Browse content in P3 - Socialist Institutions and Their Transitions

- P34 - Financial Economics

- Browse content in P4 - Other Economic Systems

- P46 - Consumer Economics; Health; Education and Training; Welfare, Income, Wealth, and Poverty

- Browse content in Q - Agricultural and Natural Resource Economics; Environmental and Ecological Economics

- Browse content in Q4 - Energy

- Q43 - Energy and the Macroeconomy

- Browse content in Q5 - Environmental Economics

- Q51 - Valuation of Environmental Effects

- Q53 - Air Pollution; Water Pollution; Noise; Hazardous Waste; Solid Waste; Recycling

- Browse content in R - Urban, Rural, Regional, Real Estate, and Transportation Economics

- Browse content in R0 - General

- R00 - General

- Browse content in R1 - General Regional Economics

- R11 - Regional Economic Activity: Growth, Development, Environmental Issues, and Changes

- R12 - Size and Spatial Distributions of Regional Economic Activity

- Browse content in R2 - Household Analysis

- R21 - Housing Demand

- R23 - Regional Migration; Regional Labor Markets; Population; Neighborhood Characteristics

- Browse content in R3 - Real Estate Markets, Spatial Production Analysis, and Firm Location

- R30 - General

- R31 - Housing Supply and Markets

- R33 - Nonagricultural and Nonresidential Real Estate Markets

- R38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R4 - Transportation Economics

- R42 - Government and Private Investment Analysis; Road Maintenance; Transportation Planning

- Browse content in Z - Other Special Topics

- Browse content in Z1 - Cultural Economics; Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology

- Z10 - General

- Z12 - Religion

- Z13 - Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology; Social and Economic Stratification

- Behavioral Asset Pricing

- Behavioral Corporate Finance

- Capital Structure and Dividend Policy

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Derivatives

- Emerging Markets

- Empirical Banking

- Entrepreneurship

- Exchange Rates

- Executive Compensation

- Experimental Finance

- Financial Econometrics

- Financial Stability and Systemic Risk

- Fixed Income and Credit Risk

- Household Finance

- International Banking

- International Asset Pricing

- Investment Banking

- Investment and Innovation

- Investment Strategies and Anomalies

- Labor and Finance

- Law and Finance

- Macro Finance

- Market Microstructure

- Mergers, Acquisitions, Restructurings, and Divestitures

- Mutual Funds and Institutional Investors

- Portfolio Choice

- Real Estate

- Real Options

- Real Effects of Financial Markets

- Risk Management

- Security Design

- The Eurozone

- Theoretical Banking

- Theoretical Asset Pricing

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About Review of Finance

- About the European Finance Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1 introduction, 2 data and descriptive statistics, 3 corporate finance style regressions, 4 decomposing leverage, 5 bank fixed effects and the speed of adjustment, 6 regulation and bank capital structure, 7 discussion and future research, 8 conclusion, appendix i: definition of variables, appendix ii. macroeconomic controls and u.s.-eu differences.

- < Previous

The Determinants of Bank Capital Structure *

We are grateful to Markus Baltzer for excellent research assistance. Earlier drafts of the paper were circulated under the title “What can corporate finance say about banks’ capital structures?” We would like to thank Franklin Allen, Allan Berger, Bruno Biais, Arnoud Boot, Charles Calomiris, Mark Carey, Murray Frank, Itay Goldstein, Vasso Ioannidou, Luc Laeven, Mike Lemmon, Vojislav Maksimovic, Steven Ongena (the editor), Elias Papaioannou, Bruno Parigi, Joshua Rauh, Joao Santos, Christian Schlag, an anonymous referee, participants and discussants at the University of Frankfurt, Maastricht University, EMST Berlin, American University, the IMF, the ECB, the ESSFM in Gerzensee, the Conference “Information in bank asset prices: theory and empirics” in Ghent, the 2007 Tor Vergata Conference on Banking and Finance, the Federal Reserve Board of Governors, the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, the European Winter Finance Conference, the Financial Intermediation Research Society conference and the Banca d’Italia for helpful comments and discussions. This paper reflects the authors’ personal opinions and does not necessarily reflect the views of the European Central Bank or the Eurosystem.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Reint Gropp, Florian Heider, The Determinants of Bank Capital Structure, Review of Finance , Volume 14, Issue 4, October 2010, Pages 587–622, https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfp030

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The paper shows that mispriced deposit insurance and capital regulation were of second-order importance in determining the capital structure of large U.S. and European banks during 1991 to 2004. Instead, standard cross-sectional determinants of non-financial firms’ leverage carry over to banks, except for banks whose capital ratio is close to the regulatory minimum. Consistent with a reduced role of deposit insurance, we document a shift in banks’ liability structure away from deposits towards non-deposit liabilities. We find that unobserved time-invariant bank fixed-effects are ultimately the most important determinant of banks’ capital structures and that banks’ leverage converges to bank specific, time-invariant targets.

This paper borrows from the empirical literature on non-financial firms to explain the capital structure of large, publicly traded banks. It uncovers empirical regularities that are inconsistent with a first-order effect of capital regulation on banks’ capital structure. Instead, the paper suggests that there are considerable similarities between banks’ and non-financial firms’ capital structures.

Because of the high costs of holding capital […], bank managers often want to hold less bank capital than is required by the regulatory authorities. In this case, the amount of bank capital is determined by the bank capital requirements (Mishkin, 2000 , p.227).

Taken literally, this suggests that there should be little cross-sectional variation in the leverage ratio of those banks falling under the Basel I regulatory regime, since it prescribes a uniform capital ratio. Figure 1 shows the distribution of the ratio of book equity to assets for a sample of the 200 largest publicly traded banks in the United States and 15 EU countries from 1991 to 2004 (we describe our data in more detail below). There is a large variation in banks’ capital ratios. 1 Figure 1 indicates that bank capital structure deserves further investigation.

Distribution of book capital ratios

The figure shows the distribution of banks’ book capital ratio (book equity divided by book assets) for the 2,415 bank-year observations in our sample of the 200 largest publicly traded banks in the U.S. and the EU from the Bankscope database from 1991 to 2004.

The objective of this paper is to examine whether capital requirements are indeed a first-order determinant of banks’ capital structure using the cross-section and time-series variation in our sample of large, publicly traded banks spanning 16 countries (the United States and the EU-15) from 1991 until 2004. To answer the question, we borrow extensively from the empirical corporate finance literature that has at length examined the capital structure of non-financial firms. 2 The literature on firms’ leverage i) has converged on a number of standard variables that are reliably related to the capital structure of non-financial firms (for example, Titman and Wessels, 1988 ; Harris and Raviv, 1991 ; Rajan and Zingales, 1995 ; Frank and Goyal, 2004 ) and ii) has examined the transitory and permanent components of leverage (for example, Flannery and Rangan, 2006 ; Lemmon et al., 2008 ).

The evidence in this paper documents that the similarities between banks’ and non-financial firms’ capital structure may be greater than previously thought. Specifically, this paper establishes five novel and interrelated empirical facts.

First, standard cross-sectional determinants of firms’ capital structures also apply to large, publicly traded banks in the US and Europe, except for banks close to the minimum capital requirement. The sign and significance of the effect of most variables on bank leverage are identical when compared to the results found in Frank and Goyal (2004) for US firms and Rajan and Zingales (1995) for firms in G-7 countries. This is true for both book and market leverage, Tier 1 capital, when controlling for risk and macro factors, for US and EU banks examined separately, as well as when examining a series of cross-sectional regressions over time.

Second, the high levels of banks’ discretionary capital observed do not appear to be explained by buffers that banks hold to insure against falling below the minimum capital requirement. Banks that would face a lower cost of raising equity at short notice (profitable, dividend paying banks with high market to book ratios) tend to hold significantly more capital.

Third, the consistency between non-financial firms and banks does not extend to the components of leverage (deposit and non-deposit liabilities). Over time, banks have financed their balance sheet growth entirely with non-deposit liabilities, which implies that the composition of banks’ total liabilities has shifted away from deposits.

Fourth, unobserved time-invariant bank fixed-effects are important in explaining the variation of banks’ capital structures. Banks appear to have stable capital structures at levels that are specific to each individual bank. Moreover, in a dynamic framework, banks’ target leverage is time-invariant and bank-specific. Both of these findings confirm Lemmon et al.'s (2008) results on the transitory and permanent components of non-financial firms’ capital structure for banks.

Fifth, controlling for banks’ characteristics, we do not find a significant effect of deposit insurance on the capital structure of banks. This is in contrast to the view that banks increase their leverage in order to maximise the subsidy arising from incorrectly priced deposit insurance.

Together, the empirical facts established in this paper suggest that capital regulation and buffers may only be of second-order importance in determining the capital structure of most banks. Hence, our paper sheds new light on the debate whether regulation or market forces determine banks’ capital structures. Barth et al. (2005) , Berger et al. (2008) and Brewer et al. (2008) observe that the levels of bank capital are much higher than the regulatory minimum. This could be explained by banks holding capital buffers in excess of the regulatory minimum. Raising equity on short notice in order to avoid violating the capital requirement is costly. Banks may therefore hold discretionary capital to reduce the probability that they have to incur this cost. 3

Alternatively, banks may be optimising their capital structure, possibly much like non-financial firms, which would relegate capital requirements to second-order importance. Flannery (1994) , Myers and Rajan (1998) , Diamond and Rajan (2000) and Allen et al. (2009) develop theories of optimal bank capital structure, in which capital requirements are not necessarily binding. Non-binding capital requirements are also explored in the market discipline literature. 4 While the literature on bank market discipline is primarily concerned with banks’ risk-taking, it also has implications for banks’ capital structures. Based on the market view, banks’ capital structures are the outcome of pressures emanating from shareholders, debt holders and depositors (Flannery and Sorescu, 1996 ; Morgan and Stiroh, 2001 ; Martinez Peria and Schmuckler, 2001 ; Calomiris and Wilson, 2004 ; Ashcraft, 2008 ; Flannery and Rangan, 2008 ). Regulatory intervention may then be non-binding and of secondary importance.

The debate is also reflected in the efforts to reform the regulatory environment in response to the current financial crisis. Brunnermeier et al. (2009) , much like this paper, conceptually distinguish between a regulatory and a market-based notion of bank capital. When examining the roots of the crisis, Greenlaw et al. (2008) argue that banks’ active management of their capital structures in relation to internal value-at-risk, rather than regulatory constraints, was a key destabilising factor.

Finally, since the patterns of banks’ capital structure line up with those uncovered for firms, our results reflect back on corporate finance findings. Banks generally are excluded from empirical investigations of capital structure. However, large publicly listed banks are a homogenous group of firms operating internationally with a comparable production technology. Hence, they constitute a natural hold-out sample. We thus confirm the robustness of these findings outside the environment in which they were originally uncovered. 5

The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 describes our sample and explains how we address the survivorship bias in the Bankscope database. Section 3 presents the baseline corporate finance style regressions for our sample of large banks and bank-holding companies. Section 4 decomposes banks’ liabilities into deposit and non-deposit liabilities. Section 5 examines the permanent and transitory components of banks’ leverage. Section 6 analyzes the effect of deposit insurance on banks’ capital structures, including the role of deposit insurance coverage in defining banks’ leverage targets. The section also considers Tier 1 capital and banks that are close to the regulatory minimum level of capital. In Section 7 we offer a number of conjectures about theories of bank capital structure that are not based on binding capital regulation and that are consistent with our evidence. Section 8 concludes.

Our data come from four sources. We obtain information about banks’ consolidated balance sheets and income statements from the Bankscope database of the Bureau van Dijk, information about banks’ stock prices and dividends from Thompson Financial's Datastream database, information about country level economic data from the World Economic Outlook database of the IMF and data on deposit insurance schemes from the Worldbank. Our sample starts in 1991 and ends in 2004. The starting point of our sample is determined by data availability in Bankscope. We decided on 2004 as the end point in order to avoid the confounding effects of i) banks anticipating the implementation of the Basle II regulatory framework and ii) banks extensive use of off-balance sheet activities in the run-up of the subprime bubble leading to the 2007–09 financial crisis. We focus only on the 100 largest publicly traded commercial banks and bank-holding companies in the United States and the 100 largest publicly traded commercial banks and bank-holding companies in 15 countries of the European Union. Our sample consists of 2,415 bank-year observations. 6 Table I shows the number of unique banks and bank-years across countries in our sample.

Unique banks and bank-years across countries

The sample consists of the 200 largest publicly traded banks in the U.S. and the EU from the Bankscope database from 1991 to 2004.

Special care has been taken to eliminate the survivorship bias inherent in the Bankscope database. Bureau van Dijk deletes historical information on banks that no longer exist in the latest release of this database. For example, the 2004 release of Bankscope does not contain information on banks that no longer exist in 2004 but did exist in previous years. 7 We address the survivorship bias in Bankscope by reassembling the panel data set by hand from individual cross-sections using historical, archived releases of the database. Bureau Van Dijk provides monthly releases of the Bankscope database. We used the last release of every year from 1991 to 2004 to provide information about banks in that year only. For example, information about banks in 1999 in our sample comes from the December 1999 release of Bankscope. This procedure also allows us to quantify the magnitude of the survivorship bias: 12% of the banks present in 1994 no longer appear in the 2004 release of the Bankscope dataset.

Table II provides descriptive statistics for the variables we use. 8 Mean total book assets are $64 billion and the median is $15 billion. Even though we selected only the largest publicly traded banks, the sample exhibits considerable heterogeneity in the cross-section. The largest bank in the sample is almost 3,000 times the size of the smallest. In light of the objective of this paper, it is useful to compare the descriptive statistics to those for a typical sample of listed non-financial firms used in the literature. We use Frank and Goyal ( 2004 , Table 3 ) for this comparison. 9 For both banks and firms the median market-to-book ratio is close to one. The assets of firms are typically three times as volatile as the assets of banks (12% versus 3.6%). The median profitability of banks is 5.1% of assets, which is a little less than half of firms’ profitability (12% of assets). Banks hold much less collateral than non-financial firms: 27% versus 56% of book assets, respectively. Our definition of collateral for banks includes liquid securities that can be used as collateral when borrowing from central banks. Nearly 95% of publicly traded banks pay dividends, while only 43% of firms do so.

Descriptive statistics

The sample consists of the 200 largest publicly traded banks in the U.S. and the EU from the Bankscope database from 1991 to 2004. See Appendix I for the definition of variables.

Correlations

The sample consists of the 200 largest publicly traded banks in the U.S. and the EU from the Bankscope database from 1991 to 2004. See Appendix I for the definition of variables. Numbers in italics indicate p -values.

Based on these simple descriptive statistics, banking appears to have been a relatively safe and, correspondingly, low return industry during our sample period. This matches the earlier finding by Flannery et al. (2004) that banks may simply be “boring”. Banks’ leverage is, however, substantially different from that of firms. Banks’ median book leverage is 92.7% and median market leverage is 88.8% while median book and market leverage of non-financial companies in Frank and Goyal (2004) is 24% and 23%, respectively. While banking is an industry with on average high leverage, there are also a substantial number of non-financial firms no less levered than banks. Welch (2007) lists the 30 most levered firms in the S&P 500 stock market index. Ten of them are financial firms. The remaining 20 are non-financial firms from various sectors including consumer goods, IT, industrials and utilities. Most of them have investment grade credit ratings and are thus not close to bankruptcy. Moreover, the S&P 500 contains 93 financial firms, which implies that 83 do not make the list of the 30 most levered firms.

Table III presents the correlations among the main variables at the bank level. Larger banks tend to have lower profits and more leverage. A bank's market-to-book ratio correlates positively with asset risk, profits and negatively with leverage. Banks with more asset risk, and more profits have less leverage. These correlations correspond to those typically found for non-financial firms.

Beginning with Titman and Wessels (1988) , then Rajan and Zingales (1995) and more recently Frank and Goyal (2004) , the empirical corporate finance literature has converged to a limited set of variables that are reliably related to the leverage of non-financial firms. Leverage is positively correlated with size and collateral, and is negatively correlated with profits, market-to-book ratio and dividends. The variables and their relation to leverage can be traced to various corporate finance theories on departures from the Modigliani-Miller irrelevance proposition (see Harris and Raviv, 1991 and Frank and Goyal, 2008 , for surveys).

Regarding banks’ capital structures, the standard view is that capital regulation constitutes an additional, overriding departure from the Modigliani-Miller irrelevance proposition (see for example Berger et al., 1995 ; Miller, 1995 ; or Santos, 2001 ). Commercial banks have deposits that are insured to protect depositors and to ensure financial stability. In order to mitigate the moral-hazard of this insurance, commercial banks must be required to hold a minimum amount of capital. Our sample consists of large, systemically relevant commercial banks in countries with explicit deposit insurance during a period in which the uniform capital regulation of Basle I is in place. In the limit, the standard corporate finance determinants should therefore have little or no explanatory power relative to regulation for the capital structure of the banks in our sample.

An alternative, less stark view of the impact of regulation has banks holding capital buffers, or discretionary capital, above the regulatory minimum in order to avoid the costs associated with having to issue fresh equity at short notice (Ayuso et al., 2004 ; Peura and Keppo, 2006 ). It follows that banks facing a higher cost of issuing equity should be less levered. According to the buffer view, the cost of issuing equity is caused by asymmetric information (as in Myers and Majluf, 1984 ). Dividend paying banks, banks with higher profits or higher market-to-book ratios can therefore be expected to face lower costs of issuing equity because they either are better known to outsiders, have more financial slack or can obtain a better price. The effect of bank size on the extent of buffers is ambiguous ex ante. Larger banks may hold smaller buffers if they are better known to the market. Alternatively, large banks may hold larger buffers if they are more complex and, hence, asymmetric information is more important. The size of buffers should also depend on the probability of falling below the regulatory threshold. If buffers are an important determinant of banks’ capital structure, we expect the level of banks’ leverage to be positively related to risk. Finally, there is no clear prediction on how collateral affects leverage.

Table IV summarizes the predicted effects of the explanatory variables on leverage for both the market and the buffer view. The signs differ substantially across the two views. To the extent that the estimated coefficients are significantly different from zero, and hence the pure regulatory view of banks’ capital structure does not apply, we can exploit the difference in the sign of the estimated coefficients to differentiate between the market and the buffer views of bank capital structure.

Predicted effects of explanatory variables on leverage: market/corporate finance view vs. buffer view

The explanatory variables are the market-to-book ratio ( MTB ), profitability ( Prof ), the natural logarithm of total assets ( Size ), collateral ( Coll ) (all lagged by one year) and a dummy for dividend payers ( Div ) for bank i in country c in year t (see the appendix for the definition of variables). The regression includes time and country fixed effects ( c t and c c ) to account for unobserved heterogeneity at the country level and across time that may be correlated with the explanatory variables. Standard errors are clustered at the bank level to account for heteroscedasticity and serial correlation of errors (Petersen, 2009 ).

The dependent variable is one minus the ratio of equity over assets in market values. It therefore includes both debt and non-debt liabilities such as deposits. The argument for using leverage rather than debt as the dependent variable is that leverage, unlike debt, is well defined (see Welch, 2007 ). Leverage is a structure that increases the sensitivity of equity to the underlying performance of the (financial) firm. When referring to theory for an interpretation of the basic capital structure regression, the corporate finance literature typically does not explicitly distinguish between debt and non-debt liabilities (exceptions are the theoretical contribution by Diamond ( 1993 ), and empirical work by Barclay and Smith ( 1995 ) and Rauh and Sufi ( 2008 )). Moreover, since leverage is one minus the equity ratio, the dependent variable can be directly linked to the regulatory view of banks’ capital structure. 10 But a bank's capital structure is different from non-financial firms’ capital structure since it includes deposits. We therefore decompose banks’ leverage into deposits and non-deposit liabilities in Section 4.

Table V shows the results of estimating Equation ( 1 ). We also report the coefficient elasticities and confront them with the results of comparable regressions for non-financial firms as reported for example in Rajan and Zingales (1995) and Frank and Goyal (2004) . When making a comparison to these standard results, it is important to bear in mind that these studies i) use long-term debt as the dependent variable (see the preceding paragraph) and ii) use much more heterogeneous samples (in size, sector and other characteristics, Frank and Goyal 2004 , Table 1). In order to further facilitate comparisons with non-financial firms, we also report the result of estimating Equation ( 1 ) (using leverage as the dependent variable) in a sample of firms that are comparable in size with the banks in our sample. 11

Bank characteristics and market leverage

All coefficients are statistically significant at the one percent level, except collateral, which is significant at the 10 percent level. All coefficients have the same sign as in the standard regressions of Rajan and Zingales (1995) , Frank and Goyal (2004) and as in our leverage regression using a sample of the largest firms (except the market-to-book ratio, which is insignificant for the market leverage of those firms). Banks’ leverage depends positively on size and collateral, and negatively on the market-to-book ratio, profits and dividends. The model also fits the data very well: the R 2 is 0.72 for banks and 0.55 for the largest non-financial firms.

We find that the elasticity of bank leverage to some explanatory variables (e.g. profits) is larger than the corresponding elasticity for firms reported in Frank and Goyal (2004) . 12 However, when we compare the elasticities of bank leverage to firms that are more comparable in size, we tend to get smaller magnitudes. The elasticity of leverage to profits is −0.018 for banks. This means that a one percent increase in median profits, $7.3m, decreases median liabilities by $2.5m. For the largest non-financial firms the elasticity of leverage to profits is −0.296, which means that an increase of profits of $6.5m (1% at the median) translates into a reduction of leverage by $10m.

The similarity in sign and significance of the estimated coefficients for banks’ leverage to the standard corporate finance regression suggests that a pure regulatory view does not apply to banks’ capital structure. But can the results be explained by banks holding buffers of discretionary capital in order to avoid violating regulatory thresholds? Recall from Table IV that banks with higher market-to-book ratios, higher profits and that pay dividends should hold less discretionary capital since they can be expected to face lower costs of issuing equity. However, these banks hold more discretionary capital. Moreover, collateral matters for the banks in our sample. Only the coefficient on bank size is in line with the regulatory view if one argues that larger banks are better known to the market and find it easier to issue equity.

Leverage can be measured in both book and market values. Both definitions have been used interchangeably in the corporate finance literature and yield similar results. 13 But the difference between book and market values is more important in the case of banks, since capital regulation is imposed on book but not on market values. We therefore re-estimate Equation ( 1 ) with book leverage as the dependent variable.

Table VI shows that the results for book leverage are similar to those for market leverage in Table V, as well as to the results in Rajan and Zingales (1995) , Frank and Goyal (2004) and the sample of the largest non-financial firms. Regressing book leverage on the standard corporate finance determinants of capital structure produces estimated coefficients that are all significant at the 1% level. Again all coefficients have the same sign as in studies of non-financial firms and as the largest non-financial firms reported in the last column. 14

Bank characteristics and book leverage

We are unable to detect significant differences between the results for the book and the market leverage of banks, as in standard corporate finance regressions using firms. This does not support the view that regulatory concerns are the main driver of banks’ capital structure since they should create a wedge between the determinants of book and market values. Like for market leverage, we do not find that the signs of the coefficients are consistent with the buffer view of banks’ capital structure (see Table IV).

Despite its prominent role in corporate finance theory, risk sometimes fails to show up as a reliable factor in the empirical literature on firms’ leverage (as for example in Titman and Wessels, 1988 ; Rajan and Zingales, 1995 ; and Frank and Goyal, 2004 ). In Welch (2004) and Lemmon et al. (2008) , risk, however, significantly reduces leverage. We therefore add risk as an explanatory variable to our empirical specification. Columns 1 and 3 of Table VII report the results.

Adding risk and examining explanatory power of bank characteristics

The negative coefficient of risk on leverage, both in market and book values, is in line with standard corporate finance arguments, but it is also consistent with the regulatory view. In its pure form, in which regulation constitutes the overriding departure from the Modigliani and Miller irrelevance proposition, a regulator could force riskier banks to hold more book equity. In that regard, omitting risk from the standard leverage regression (1) would result in a spurious significance of the remaining variables. The results in Table VII show this is not the case. Risk does not drive out the other variables. An F-test on the joint insignificance of all non-risk coefficients is rejected. All coefficients from Tables IV and V remain significant at the 1% level, except i) the coefficient of the market-to-book ratio on book leverage, which is no longer significant, and ii) the coefficient of collateral on market leverage, which becomes significant at the 5% level (from being marginally significant at the 10% level before). 15

Since capital requirements under Basel I, the relevant regulation during our sample period, are generally risk insensitive, riskier banks cannot be formally required to hold more capital. Regulators may, however, discretionally ask banks to do so. In the US, for example, regulators have modified Basel I to increase its risk sensitivity and the results could reflect these modifications (FDICIA). However, the coefficient on risk is twice as large for market leverage as for book leverage (Table VII). Since regulation pertains to book and not market capital, it is unlikely that regulation drives the negative relationship between leverage and risk in our sample. There is also complementary evidence in the literature on this point. For example, Flannery and Rangan (2008) conclude that regulatory pressures cannot explain the relationship between risk and capital in the US during the 1990s. 16 Calomiris and Wilson (2004) find a negative relationship between risk and leverage using a sample of large publicly traded US banks in the 1920s and 1930s when there was no capital regulation.

It is instructive to examine the individual contribution of each explanatory variable to the fit of the regression. In columns 2 and 4 of Table VII, we present the increase in R 2 of adding one variable at a time to a baseline specification with time and country fixed-effects only. The market-to-book ratio accounts for an extra 45 percentage points of the variation in market leverage but only for an extra 8 percentage points of the variation in book leverage. This is not surprising given that the market-to-book ratio and the market leverage ratio both contain the market value of assets. Risk is the second most important variable for market leverage and the most important variable for book leverage. Risk alone explains an extra 28 percentage points of the variation in market leverage and an extra 12 percentage points of the variation in book leverage. Size and profits together explain an extra 10 percentage points. Collateral and dividend paying status hardly affect the fit of the leverage regressions. 17

Finally, we ask whether the high R 2 obtained when regressing banks’ leverage on the standard set of corporate finance variables (Tables V to VII) is partly due to including time and country fixed-effects. The results of dropping either or both fixed-effects from the regression are reported in Table VIII . Without either country or time fixed effects, the R 2 drops from 0.80 to 0.74 in market leverage regressions and from 0.58 to 0.46 in book leverage regressions. While country and time fixed effects seem to be useful in controlling for heterogeneity across time and countries, the fit of our regressions is only to a limited extent driven by country or time fixed effects. 18

Time and country fixed effects

In Appendix II, we show that the stable relationship between standard determinants of capital structure and bank leverage is robust to including macroeconomic variables, and holds up if we estimate the model separately for U.S. and EU banks. The consistency of results across the U.S. and the EU is further evidence that regulation is unlikely to be the main driver of the capital structure of banks in our sample. Even in Europe, where regulators have much less discretion to modify the risk insensitivity of Basel I (see also the discussion of Table VII above), we find a significant relationship between risk and leverage.

Banks’ capital structure fundamentally differs from the one of non-financial firms since it includes deposits, a source of financing generally not available to firms. 19 Moreover, much of the empirical research for firms was performed using long term debt divided by assets rather than total liabilities divided by assets. This section therefore decomposes bank liabilities into deposit and non-deposit liabilities. Non-deposit liabilities can be viewed as being closely related to long term debt for firms. They consist of senior long term debt, subordinated debt and other debenture notes. The overall correlation between deposits and non-deposit liabilities is between −0.839 and −0.975 (depending on whether market or book values are used). 20 Figure 2 reports the median composition of banks’ liabilities over time and shows that banks have substituted non-deposit debt for deposits during our sample period. The share of non-deposit liabilities in total book assets increases from around 20% in the early 90s to 29% in 2004. The share of deposits declines correspondingly from 73% in the early 90s to 64% in 2004. Book equity remains almost unchanged at around 7% of total assets. There is a slight upward trend in equity until 2001 (to 8.4% of total assets), but the trend reverses in the later years of the sample. In nominal terms, the balance sheet of the median bank increased by 12% from 1991 to 2004. Nominal deposits remained unchanged but nominal non-deposit liabilities grew by 60%. Banks seem to have financed their growth entirely via non-deposit liabilities.

Composition of banks’ liabilities over time

The figure shows the evolution of banks’ median deposit and non-deposit liabilities (in book values), as well as book equity as a percentage of the book value of banks for 2,408 bank-year observations in our sample of the 200 largest publicly traded banks in the U.S. and the EU from the Bankscope database from 1991 to 2004.

The effective substitution between deposits and non-deposit liabilities is also visible in Table IX , which reports the results of estimating Equation ( 1 ) (with risk) separately for deposits and non-deposit liabilities. Whenever an estimated coefficient is significant, it has the opposite sign for deposits and for non-deposit liabilities (except the market-to-book ratio for market leverage).

Decomposing bank leverage

The signs of the coefficients in the regression using non-deposit liabilities are the same as in the previous leverage regressions, except for profits. 21 Larger banks and banks with more collateral have fewer deposits and more non-deposit liabilities, which is consistent with these banks having better access to debt markets. More profitable banks substituting away from deposits may be an indication of a larger debt capacity as they are less likely to default. Risk and dividend payout status, however, are no longer significant for either deposits or non-deposit liabilities.

In sum, the standard corporate finance style regression works less well for the components of leverage than for leverage itself. This is also borne out by a drop in the R 2 from 58% and 80% in book and market leverage regressions, respectively, to around 30–40% in regressions with deposits and non-deposit liabilities as the dependent variables. Except for profits, the signs of the estimated coefficients when the dependent variable is non-deposit liabilities are as before for total leverage. But the signs are the opposite when the dependent variable is deposits. Moreover, risk is no longer a significant explanatory variable for either component of leverage. The failure of the model for deposits is consistent with regulation as a driver of deposits, but standard corporate finance variables retain their importance for non-deposit liabilities, which is consistent with the findings for long term debt for non-financial firms. Moreover, the shift away from deposits towards non-deposit liabilities as a source of financing further supports a much reduced role of regulation as a determinant of banks’ capital structure. Since total leverage is not driven by regulation, one must distinguish between the capital and the liability structure of large publicly traded banks (see also the discussion in Section 7).

Recently, Lemmon et al. (2008) show that adding firm fixed effects to the typical corporate finance leverage regression (1) has important consequences for thinking about capital structure. They find that the fixed effects explain most of the variation in leverage. That is, firms’ capital structure is mostly driven by an unobserved time-invariant firm-specific factor.

We want to know whether this finding also extends to banks. Table X reports the results from estimating Equation ( 1 ) (with risk) where country fixed effects are replaced by bank fixed effects. The table shows that as in Lemmon et al. (2008) for firms, most of the variation in banks’ leverage is driven by bank fixed effects. The fixed effect accounts for 92% of book leverage and for 76% of market leverage. Comparable figures for non-financial firms are 92% for book leverage and 85% for market leverage (Lemmon et al., 2008 , Table 3). The coefficients of the explanatory variables keep the same sign as in Table VII (except for the market-to-book ratio when using book leverage) but their magnitude and significance reduces since they are now identified from the time-series variation within banks only.

Bank fixed effects and the speed of adjustment

The importance of bank fixed effects casts further doubt on regulation as a main driver of banks’ capital structure. The Basel 1 capital requirements and their implementation apply to all relevant banks in the same way and they are of course irrelevant for non-financial firms. Yet, banks’ leverage appears to be stable for long periods around levels specific to each individual bank and this stability is comparable to the one documented for non-financial firms.

Next, we examine the speed of adjustment to target capital ratios. The objective is twofold. First, a similarity of the speed of adjustment for non-financial and financial firms would again be evidence that banks’ capital structures are driven by forces that are comparable to those driving firms’ capital structures. Second, we can further investigate the relative importance of regulatory factors, which are common to all banks, and bank specific factors.

Following Flannery and Rangan (2006) and Lemmon et al. (2008) , we estimate a standard partial adjustment model. We limit the analysis to book leverage since the effect of regulation should be most visible there. 22 Table X present results for pooled OLS estimates (Columns 3 and 4) and fixed effects estimates (Columns 5 and 6). 23 Flannery and Rangan (2006) show that pooled OLS estimates understate the speed of adjustment as the model assumes that there is no unobserved heterogeneity at the firm level that affects their target leverage. Adding firm fixed effects therefore increases the speed of adjustment significantly.

This finding applies to banks, too. Using pooled OLS estimates we find a speed of adjustment of 9%, which is low and similar to the 13% for non-financial firms in Flannery and Rangan (2006) and Lemmon et al. (2008) . Adding bank fixed effects, the speed of adjustment increases to 45% ( Flannery and Rangan (2006) and Lemmon et al. (2008) : 38% and 36%, respectively). Hence, we confirm that it is important to control for unobserved bank-specific effects on banks’ target leverage. This is evidence against the regulatory view of banks that banks should converge to a common target, namely the minimum requirement set under Basel I.

Lemmon et al. (2008) add that, as in the case of static regressions, the fixed effects and not the observed explanatory variables are the most important factor for identifying firms’ target leverage. Adding standard determinants of leverage to firm fixed effects increases the speed of adjustment only by 3 percentage points (i.e. from 36% to 39%, see Lemmon et al. (2008) , Table 6). The same holds for banks. Adding the standard determinants of leverage increases the speed of adjustment by 1.8 percentage points to 46.8%. Banks, like non-financial firms, converge to time-invariant bank-specific targets. The standard time-varying corporate finance variables do not help much in determining the target capitals structures of banks. It suggests that buffers are unlikely to be able to explain banks’ capital structures. Contrary to what is usually argued, these buffers would have to be independent of the cost of issuing equity on short notice since the estimated speed of adjustment is invariant to banks’ market-to-book ratios, profitability or dividend paying status.

The implications of these results are twofold. First, it suggests that capital regulation and deposit insurance are not the overriding departures from the Modigliani and Miller irrelevance proposition for banks. Second, our results, obtained in a hold-out sample of banks, reflect back on the findings for non-financial firms. It narrows down the list of candidate explanations of what drives capital structure. For example, confirming the finding of Lemmon et al. (2008) on the transitory and permanent components of firms’ leverage in our hold-out sample makes it unlikely that unobserved heterogeneity across industries can explain why capital structures tend to be stable for long periods. The banks in our sample form a fairly homogenous, global, single industry that operates under different institutional and technological circumstances than non-financial firms.

This section exploits the cross-country nature of our dataset to explicitly identify a potential effect of regulation on capital structure. The argument that capital regu- lation constitutes the overriding departure for banks from the Modigliani and Miller benchmark depends on (incorrectly priced) deposits insurance providing banks with incentives to maximise leverage up to the regulatory minimum. 24 We therefore exploit the variation in deposit insurance schemes across time and countries in our sample and include deposit insurance coverage in the country of residence of the bank in our regressions. 25 This section also seeks to uncover an effect of regulation by considering regulatory Tier 1 capital as an alternative dependent variable and by examining the situation of banks that are close to violating their capital requirement.