How To Write A Research Paper

Step-By-Step Tutorial With Examples + FREE Template

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | March 2024

For many students, crafting a strong research paper from scratch can feel like a daunting task – and rightly so! In this post, we’ll unpack what a research paper is, what it needs to do , and how to write one – in three easy steps. 🙂

Overview: Writing A Research Paper

What (exactly) is a research paper.

- How to write a research paper

- Stage 1 : Topic & literature search

- Stage 2 : Structure & outline

- Stage 3 : Iterative writing

- Key takeaways

Let’s start by asking the most important question, “ What is a research paper? ”.

Simply put, a research paper is a scholarly written work where the writer (that’s you!) answers a specific question (this is called a research question ) through evidence-based arguments . Evidence-based is the keyword here. In other words, a research paper is different from an essay or other writing assignments that draw from the writer’s personal opinions or experiences. With a research paper, it’s all about building your arguments based on evidence (we’ll talk more about that evidence a little later).

Now, it’s worth noting that there are many different types of research papers , including analytical papers (the type I just described), argumentative papers, and interpretative papers. Here, we’ll focus on analytical papers , as these are some of the most common – but if you’re keen to learn about other types of research papers, be sure to check out the rest of the blog .

With that basic foundation laid, let’s get down to business and look at how to write a research paper .

Overview: The 3-Stage Process

While there are, of course, many potential approaches you can take to write a research paper, there are typically three stages to the writing process. So, in this tutorial, we’ll present a straightforward three-step process that we use when working with students at Grad Coach.

These three steps are:

- Finding a research topic and reviewing the existing literature

- Developing a provisional structure and outline for your paper, and

- Writing up your initial draft and then refining it iteratively

Let’s dig into each of these.

Need a helping hand?

Step 1: Find a topic and review the literature

As we mentioned earlier, in a research paper, you, as the researcher, will try to answer a question . More specifically, that’s called a research question , and it sets the direction of your entire paper. What’s important to understand though is that you’ll need to answer that research question with the help of high-quality sources – for example, journal articles, government reports, case studies, and so on. We’ll circle back to this in a minute.

The first stage of the research process is deciding on what your research question will be and then reviewing the existing literature (in other words, past studies and papers) to see what they say about that specific research question. In some cases, your professor may provide you with a predetermined research question (or set of questions). However, in many cases, you’ll need to find your own research question within a certain topic area.

Finding a strong research question hinges on identifying a meaningful research gap – in other words, an area that’s lacking in existing research. There’s a lot to unpack here, so if you wanna learn more, check out the plain-language explainer video below.

Once you’ve figured out which question (or questions) you’ll attempt to answer in your research paper, you’ll need to do a deep dive into the existing literature – this is called a “ literature search ”. Again, there are many ways to go about this, but your most likely starting point will be Google Scholar .

If you’re new to Google Scholar, think of it as Google for the academic world. You can start by simply entering a few different keywords that are relevant to your research question and it will then present a host of articles for you to review. What you want to pay close attention to here is the number of citations for each paper – the more citations a paper has, the more credible it is (generally speaking – there are some exceptions, of course).

Ideally, what you’re looking for are well-cited papers that are highly relevant to your topic. That said, keep in mind that citations are a cumulative metric , so older papers will often have more citations than newer papers – just because they’ve been around for longer. So, don’t fixate on this metric in isolation – relevance and recency are also very important.

Beyond Google Scholar, you’ll also definitely want to check out academic databases and aggregators such as Science Direct, PubMed, JStor and so on. These will often overlap with the results that you find in Google Scholar, but they can also reveal some hidden gems – so, be sure to check them out.

Once you’ve worked your way through all the literature, you’ll want to catalogue all this information in some sort of spreadsheet so that you can easily recall who said what, when and within what context. If you’d like, we’ve got a free literature spreadsheet that helps you do exactly that.

Step 2: Develop a structure and outline

With your research question pinned down and your literature digested and catalogued, it’s time to move on to planning your actual research paper .

It might sound obvious, but it’s really important to have some sort of rough outline in place before you start writing your paper. So often, we see students eagerly rushing into the writing phase, only to land up with a disjointed research paper that rambles on in multiple

Now, the secret here is to not get caught up in the fine details . Realistically, all you need at this stage is a bullet-point list that describes (in broad strokes) what you’ll discuss and in what order. It’s also useful to remember that you’re not glued to this outline – in all likelihood, you’ll chop and change some sections once you start writing, and that’s perfectly okay. What’s important is that you have some sort of roadmap in place from the start.

At this stage you might be wondering, “ But how should I structure my research paper? ”. Well, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution here, but in general, a research paper will consist of a few relatively standardised components:

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Methodology

Let’s take a look at each of these.

First up is the introduction section . As the name suggests, the purpose of the introduction is to set the scene for your research paper. There are usually (at least) four ingredients that go into this section – these are the background to the topic, the research problem and resultant research question , and the justification or rationale. If you’re interested, the video below unpacks the introduction section in more detail.

The next section of your research paper will typically be your literature review . Remember all that literature you worked through earlier? Well, this is where you’ll present your interpretation of all that content . You’ll do this by writing about recent trends, developments, and arguments within the literature – but more specifically, those that are relevant to your research question . The literature review can oftentimes seem a little daunting, even to seasoned researchers, so be sure to check out our extensive collection of literature review content here .

With the introduction and lit review out of the way, the next section of your paper is the research methodology . In a nutshell, the methodology section should describe to your reader what you did (beyond just reviewing the existing literature) to answer your research question. For example, what data did you collect, how did you collect that data, how did you analyse that data and so on? For each choice, you’ll also need to justify why you chose to do it that way, and what the strengths and weaknesses of your approach were.

Now, it’s worth mentioning that for some research papers, this aspect of the project may be a lot simpler . For example, you may only need to draw on secondary sources (in other words, existing data sets). In some cases, you may just be asked to draw your conclusions from the literature search itself (in other words, there may be no data analysis at all). But, if you are required to collect and analyse data, you’ll need to pay a lot of attention to the methodology section. The video below provides an example of what the methodology section might look like.

By this stage of your paper, you will have explained what your research question is, what the existing literature has to say about that question, and how you analysed additional data to try to answer your question. So, the natural next step is to present your analysis of that data . This section is usually called the “results” or “analysis” section and this is where you’ll showcase your findings.

Depending on your school’s requirements, you may need to present and interpret the data in one section – or you might split the presentation and the interpretation into two sections. In the latter case, your “results” section will just describe the data, and the “discussion” is where you’ll interpret that data and explicitly link your analysis back to your research question. If you’re not sure which approach to take, check in with your professor or take a look at past papers to see what the norms are for your programme.

Alright – once you’ve presented and discussed your results, it’s time to wrap it up . This usually takes the form of the “ conclusion ” section. In the conclusion, you’ll need to highlight the key takeaways from your study and close the loop by explicitly answering your research question. Again, the exact requirements here will vary depending on your programme (and you may not even need a conclusion section at all) – so be sure to check with your professor if you’re unsure.

Step 3: Write and refine

Finally, it’s time to get writing. All too often though, students hit a brick wall right about here… So, how do you avoid this happening to you?

Well, there’s a lot to be said when it comes to writing a research paper (or any sort of academic piece), but we’ll share three practical tips to help you get started.

First and foremost , it’s essential to approach your writing as an iterative process. In other words, you need to start with a really messy first draft and then polish it over multiple rounds of editing. Don’t waste your time trying to write a perfect research paper in one go. Instead, take the pressure off yourself by adopting an iterative approach.

Secondly , it’s important to always lean towards critical writing , rather than descriptive writing. What does this mean? Well, at the simplest level, descriptive writing focuses on the “ what ”, while critical writing digs into the “ so what ” – in other words, the implications. If you’re not familiar with these two types of writing, don’t worry! You can find a plain-language explanation here.

Last but not least, you’ll need to get your referencing right. Specifically, you’ll need to provide credible, correctly formatted citations for the statements you make. We see students making referencing mistakes all the time and it costs them dearly. The good news is that you can easily avoid this by using a simple reference manager . If you don’t have one, check out our video about Mendeley, an easy (and free) reference management tool that you can start using today.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. To recap, the three steps to writing a high-quality research paper are:

- To choose a research question and review the literature

- To plan your paper structure and draft an outline

- To take an iterative approach to writing, focusing on critical writing and strong referencing

Remember, this is just a b ig-picture overview of the research paper development process and there’s a lot more nuance to unpack. So, be sure to grab a copy of our free research paper template to learn more about how to write a research paper.

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- French Abstracts

- Portuguese Abstracts

- Spanish Abstracts

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About International Journal for Quality in Health Care

- About the International Society for Quality in Health Care

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Contact ISQua

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Primacy of the research question, structure of the paper, writing a research article: advice to beginners.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Thomas V. Perneger, Patricia M. Hudelson, Writing a research article: advice to beginners, International Journal for Quality in Health Care , Volume 16, Issue 3, June 2004, Pages 191–192, https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzh053

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Writing research papers does not come naturally to most of us. The typical research paper is a highly codified rhetorical form [ 1 , 2 ]. Knowledge of the rules—some explicit, others implied—goes a long way toward writing a paper that will get accepted in a peer-reviewed journal.

A good research paper addresses a specific research question. The research question—or study objective or main research hypothesis—is the central organizing principle of the paper. Whatever relates to the research question belongs in the paper; the rest doesn’t. This is perhaps obvious when the paper reports on a well planned research project. However, in applied domains such as quality improvement, some papers are written based on projects that were undertaken for operational reasons, and not with the primary aim of producing new knowledge. In such cases, authors should define the main research question a posteriori and design the paper around it.

Generally, only one main research question should be addressed in a paper (secondary but related questions are allowed). If a project allows you to explore several distinct research questions, write several papers. For instance, if you measured the impact of obtaining written consent on patient satisfaction at a specialized clinic using a newly developed questionnaire, you may want to write one paper on the questionnaire development and validation, and another on the impact of the intervention. The idea is not to split results into ‘least publishable units’, a practice that is rightly decried, but rather into ‘optimally publishable units’.

What is a good research question? The key attributes are: (i) specificity; (ii) originality or novelty; and (iii) general relevance to a broad scientific community. The research question should be precise and not merely identify a general area of inquiry. It can often (but not always) be expressed in terms of a possible association between X and Y in a population Z, for example ‘we examined whether providing patients about to be discharged from the hospital with written information about their medications would improve their compliance with the treatment 1 month later’. A study does not necessarily have to break completely new ground, but it should extend previous knowledge in a useful way, or alternatively refute existing knowledge. Finally, the question should be of interest to others who work in the same scientific area. The latter requirement is more challenging for those who work in applied science than for basic scientists. While it may safely be assumed that the human genome is the same worldwide, whether the results of a local quality improvement project have wider relevance requires careful consideration and argument.

Once the research question is clearly defined, writing the paper becomes considerably easier. The paper will ask the question, then answer it. The key to successful scientific writing is getting the structure of the paper right. The basic structure of a typical research paper is the sequence of Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion (sometimes abbreviated as IMRAD). Each section addresses a different objective. The authors state: (i) the problem they intend to address—in other terms, the research question—in the Introduction; (ii) what they did to answer the question in the Methods section; (iii) what they observed in the Results section; and (iv) what they think the results mean in the Discussion.

In turn, each basic section addresses several topics, and may be divided into subsections (Table 1 ). In the Introduction, the authors should explain the rationale and background to the study. What is the research question, and why is it important to ask it? While it is neither necessary nor desirable to provide a full-blown review of the literature as a prelude to the study, it is helpful to situate the study within some larger field of enquiry. The research question should always be spelled out, and not merely left for the reader to guess.

Typical structure of a research paper

The Methods section should provide the readers with sufficient detail about the study methods to be able to reproduce the study if so desired. Thus, this section should be specific, concrete, technical, and fairly detailed. The study setting, the sampling strategy used, instruments, data collection methods, and analysis strategies should be described. In the case of qualitative research studies, it is also useful to tell the reader which research tradition the study utilizes and to link the choice of methodological strategies with the research goals [ 3 ].

The Results section is typically fairly straightforward and factual. All results that relate to the research question should be given in detail, including simple counts and percentages. Resist the temptation to demonstrate analytic ability and the richness of the dataset by providing numerous tables of non-essential results.

The Discussion section allows the most freedom. This is why the Discussion is the most difficult to write, and is often the weakest part of a paper. Structured Discussion sections have been proposed by some journal editors [ 4 ]. While strict adherence to such rules may not be necessary, following a plan such as that proposed in Table 1 may help the novice writer stay on track.

References should be used wisely. Key assertions should be referenced, as well as the methods and instruments used. However, unless the paper is a comprehensive review of a topic, there is no need to be exhaustive. Also, references to unpublished work, to documents in the grey literature (technical reports), or to any source that the reader will have difficulty finding or understanding should be avoided.

Having the structure of the paper in place is a good start. However, there are many details that have to be attended to while writing. An obvious recommendation is to read, and follow, the instructions to authors published by the journal (typically found on the journal’s website). Another concerns non-native writers of English: do have a native speaker edit the manuscript. A paper usually goes through several drafts before it is submitted. When revising a paper, it is useful to keep an eye out for the most common mistakes (Table 2 ). If you avoid all those, your paper should be in good shape.

Common mistakes seen in manuscripts submitted to this journal

Huth EJ . How to Write and Publish Papers in the Medical Sciences , 2nd edition. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins, 1990 .

Browner WS . Publishing and Presenting Clinical Research . Baltimore, MD: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 1999 .

Devers KJ , Frankel RM. Getting qualitative research published. Educ Health 2001 ; 14 : 109 –117.

Docherty M , Smith R. The case for structuring the discussion of scientific papers. Br Med J 1999 ; 318 : 1224 –1225.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1464-3677

- Print ISSN 1353-4505

- Copyright © 2024 International Society for Quality in Health Care and Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 16 April 2021

How to approach academic writing

- Fiona Ellwood 1

BDJ Team volume 8 , pages 20–21 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

1518 Accesses

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Fiona Ellwood says that writing at a higher level is an art and a craft and comes with practice and experience.

©Rawpixel / iStock / Getty Images Plus

One of the greatest challenges in academic writing is knowing where to start and what is expected. This can be particularly challenging if you have perhaps not written or been part of writing academic pieces. Those who have undertaken university level education may find this less challenging, but this is not always the case. There is certainly an art to writing at a higher level and whilst it may be a gift to some, more often, it is an art, a craft and comes with practice and experience.

The purpose of this article is to shed some light on many of the unknowns of academic writing and to take away some of the myths and untruths. Primarily the article will focus upon academic writing at university, but once this is mastered it must be noted that it is a skill that will prove invaluable in article and paper writing and is likely to help in preparation of reports and responses to consultations and so much more.

With the focus upon an academic paper, one of the first tips is to ensure the module handbook and task in hand is understood and the expectations are clear. It may be that at first there is a whole new meaning to words and an element of confusion. As noted earlier, academic writing is an art and a craft and when writing for the purpose of addressing a university module there are clearly defined components that must be met. So, whilst you have the autonomy to select the focus, there are almost always defined parameters and requirements that must be adhered to, to at least receive a satisfactory mark. 1

Before doing this, it is perhaps pertinent to discover how you best learn, how you intend to gather and store relevant information and how to establish a best way of working. One of the most useful tips is to plan and structure the paper, design an outline and a timeline. This will help you manage your time well and help you to focus.

Almost always a module will have a subject focus for example, in an evidence-based practice module, designed to help you prepare for the writing of a final dissertation. You may be faced with the following assessment task:

Report: 3,500 words (+/- 10%)1

A critical report, which provides evidence of the acquisition of the knowledge, skills and understanding required to devise, plan, implement, analyse, critically evaluate, and synthesise a small-scale piece of educational research at level 7.

So, to avoid 'writer's block' 2 when faced with such a task, it is important to break the task down. The important features are:

Produce a 'critical report' - this determines the format that is expected

Number of words 3,500 give or take 10% - this allows you to divide the paper into sections and get a feel for how many pages will be required.

Looking closely at the assessment task there are other important words of meaning:

Evidence of

Acquisition of knowledge, skills and understanding

Devise, plan, implement

Analyse, critically evaluate and synthesise

Small-scale piece of educational research.

Look for the concept words, the function words, and the scope of the task. It is so important to break the task down and equally to look at the task against the learning outcomes. In this instance the learning outcomes were:

Evidence a critical understanding of educational research planning and design

Critically analyse and evaluate a range of research methods and approaches used in educational research.

This now sets the scene to read and write... but does it, if you have never undertaken this type of task before?

The fundamentals of academic writing

The fundamentals of producing a paper begins very early on and can inevitably be determined by your engagement with the module. Every module provides a suggested reading list; some of those on the list are core reading and others are additional suggestions, but the reading does not stop there. 3 This could be referred to as a deep dive into the topic, but even the reading needs to be planned. There is no need to read everything you can find on the central topic, in fact the setting of your reading parameters will serve you well; 4 , 5 , 6 this is something discussed further on in the article.

Developing academic writing skills

No one style of writing fits all eventualities or all university conventions; academic English is more formal than much of the spoken language itself. There may be a need to become familiar with new technical terms and extend your vocabulary. 7

Academic writing can be:

Descriptive

Argumentative

The type of academic writing when addressing a university module is most likely to be pre-determined within the task, as is the structure. It can be useful to outline the sections and identify the word count per section. On average a paper of 2,500 words would have an introduction of approximately 200 words and a conclusion of 300 words, leaving 2,000 words for the body of the paper. Always confirm what is and what is not included in the word count.

Top tips for writing: 8 , 9 , 10

Make use of technology

Check the guidance on font size and style and line spacing

Read well; set parameters - consider the currency of the information, the source, the type of information, is it evidence-based, is there any bias. Consider counter arguments, differing perspectives. Build a scaffold and develop your own understanding. This will in turn inform your writing

If using numbers confirm that they can be trusted

Confirm if tables and pictures are allowed in the body of the text

Be aware of the required referencing style 11

Avoid plagiarism and reference as you go along

Develop a note-making style 12

Plan and structure the paper, identifying key milestones and timelines

Write your introduction last

Write words in full; avoid shorthand and acronyms

Be impersonal - avoid personal pronouns such as I/we/you; check if the third person is a requirement of the writing

Consider the sentence construction

Be objective

Write a first draft

Engage with module lead and act upon feedback

Write a final draft

Proofread before submitting and do not leave submitting the paper to the last minute.

Making broader use of these newfound skills can bring new and different opportunities and has the potential to arm you with the confidence to write in different spheres and contribute to debates and discussions. When it comes to writing for established journals you are likely to find that academic writing will have prepared you well.

Author information

Fiona is the President and Executive Director of the Society of British Dental Nurses and a member of the Dental Professional Alliance (DPA). She has received a British Empire Medal (BEM) and acts as a key opinion leader and advisor for oral health and preventative practice, infection prevention and professional practice. She has a strong interest in population level health matters and inequalities in health. Fiona is heavily involved in education across the sector and invests a great deal of time on programme design and development with a strong focus on quality assurance and assessment.

Fernsten L A, Reda M. Helping students meet the challenges of academic writing. Teaching Higher Educ 2013; 16: 171-182.

Horwitz E B, Stenfors C, Osika W. Contemporary inquiry in movement: Managing writer's block in academic writing. Int J Transpersonal Studies 2013; 32: 16-23.

Aveyard H. Doing a literature review in health and social care: a practical guide (3 rd edition). Berkshire: Open University Press, 2014.

Cottrell S. Study skills handbook (4th edition). Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2013.

Burton N, Brundette M, Jones M. Doing your education research project . London: Sage, 2008.

Bell J. Doing your research project: a guide for first-time researchers in education, health and social science (5 th edition). Berkshire: Open University Press, 2010.

Day T. Success in academic writing (2 nd edition). Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2018.

Patton M Q. Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3 rd edition). London: Sage Publications, 2002.

Cohen L, Manion L, Morrison K. Research methods in education (6th edition). London: Routledge, 2008.

Newby P. Research methods for education . Essex: Routledge, 2009.

Pears R, Shields G. Cite them right: the essential reference guide . London: Red Globe Press, 2019.

Hart C. Doing your Masters dissertation. London: SAGE Essential Study Skills, 2005.

Download references

Editor's note: DCP research issue

In September BDJ Team will be publishing a themed issue focusing on DCP research. If you are a DCP, either in practice or studying at university, have been involved with research and would like to present your findings to the readers of BDJ Team , please contact the Editor via [email protected], or submit your article online at https://go.nature.com/31xft0w .

The deadline for submissions will be early July 2021.

Authors and Affiliations

East Midlands, UK

Fiona Ellwood

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ellwood, F. How to approach academic writing. BDJ Team 8 , 20–21 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41407-021-0586-z

Download citation

Published : 16 April 2021

Issue Date : April 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41407-021-0586-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Writing Worksheets and Other Writing Resources

- The Writing Process

A Process Approach to Writing Research Papers

About the slc.

- Our Mission and Core Values

(adapted from Research Paper Guide, Point Loma Nazarene University, 2010)

Step 1: Be a Strategic Reader and Scholar

Even before your paper is assigned, use the tools you have been given by your instructor and GSI, and create tools you can use later.

See the handout “Be a Strategic Reader and Scholar” for more information.

Step 2: Understand the Assignment

- Free topic choice or assigned?

- Type of paper: Informative? Persuasive? Other?

- Any terminology in assignment not clear?

- Library research needed or required? How much?

- What style of citation is required?

- Can you break the assignment into parts?

- When will you do each part?

- Are you required or allowed to collaborate with other members of the class?

- Other special directions or requirements?

Step 3: Select a Topic

- interests you

- you know something about

- you can research easily

- Write out topic and brainstorm.

- Select your paper’s specific topic from this brainstorming list.

- In a sentence or short paragraph, describe what you think your paper is about.

Step 4: Initial Planning, Investigation, and Outlining

- the nature of your audience

- ideas & information you already possess

- sources you can consult

- background reading you should do

Make a rough outline, a guide for your research to keep you on the subject while you work.

Step 5: Accumulate Research Materials

- Use cards, Word, Post-its, or Excel to organize.

- Organize your bibliography records first.

- Organize notes next (one idea per document— direct quotations, paraphrases, your own ideas).

- Arrange your notes under the main headings of your tentative outline. If necessary, print out documents and literally cut and paste (scissors and tape) them together by heading.

Step 6: Make a Final Outline to Guide Writing

- Reorganize and fill in tentative outline.

- Organize notes to correspond to outline.

- As you decide where you will use outside resources in your paper, make notes in your outline to refer to your numbered notecards, attach post-its to your printed outline, or note the use of outside resources in a different font or text color from the rest of your outline.

- In both Steps 6 and 7, it is important to maintain a clear distinction between your own words and ideas and those of others.

Step 7: Write the Paper

- Use your outline to guide you.

- Write quickly—capture flow of ideas—deal with proofreading later.

- Put aside overnight or longer, if possible.

Step 8: Revise and Proofread

- Check organization—reorganize paragraphs and add transitions where necessary.

- Make sure all researched information is documented.

- Rework introduction and conclusion.

- Work on sentences—check spelling, punctuation, word choice, etc.

- Read out loud to check for flow.

Carolyn Swalina, Writing Program Coordinator Student Learning Center, University of California, Berkeley ©2011 UC Regents

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Writing Survey Questions

Perhaps the most important part of the survey process is the creation of questions that accurately measure the opinions, experiences and behaviors of the public. Accurate random sampling will be wasted if the information gathered is built on a shaky foundation of ambiguous or biased questions. Creating good measures involves both writing good questions and organizing them to form the questionnaire.

Questionnaire design is a multistage process that requires attention to many details at once. Designing the questionnaire is complicated because surveys can ask about topics in varying degrees of detail, questions can be asked in different ways, and questions asked earlier in a survey may influence how people respond to later questions. Researchers are also often interested in measuring change over time and therefore must be attentive to how opinions or behaviors have been measured in prior surveys.

Surveyors may conduct pilot tests or focus groups in the early stages of questionnaire development in order to better understand how people think about an issue or comprehend a question. Pretesting a survey is an essential step in the questionnaire design process to evaluate how people respond to the overall questionnaire and specific questions, especially when questions are being introduced for the first time.

For many years, surveyors approached questionnaire design as an art, but substantial research over the past forty years has demonstrated that there is a lot of science involved in crafting a good survey questionnaire. Here, we discuss the pitfalls and best practices of designing questionnaires.

Question development

There are several steps involved in developing a survey questionnaire. The first is identifying what topics will be covered in the survey. For Pew Research Center surveys, this involves thinking about what is happening in our nation and the world and what will be relevant to the public, policymakers and the media. We also track opinion on a variety of issues over time so we often ensure that we update these trends on a regular basis to better understand whether people’s opinions are changing.

At Pew Research Center, questionnaire development is a collaborative and iterative process where staff meet to discuss drafts of the questionnaire several times over the course of its development. We frequently test new survey questions ahead of time through qualitative research methods such as focus groups , cognitive interviews, pretesting (often using an online, opt-in sample ), or a combination of these approaches. Researchers use insights from this testing to refine questions before they are asked in a production survey, such as on the ATP.

Measuring change over time

Many surveyors want to track changes over time in people’s attitudes, opinions and behaviors. To measure change, questions are asked at two or more points in time. A cross-sectional design surveys different people in the same population at multiple points in time. A panel, such as the ATP, surveys the same people over time. However, it is common for the set of people in survey panels to change over time as new panelists are added and some prior panelists drop out. Many of the questions in Pew Research Center surveys have been asked in prior polls. Asking the same questions at different points in time allows us to report on changes in the overall views of the general public (or a subset of the public, such as registered voters, men or Black Americans), or what we call “trending the data”.

When measuring change over time, it is important to use the same question wording and to be sensitive to where the question is asked in the questionnaire to maintain a similar context as when the question was asked previously (see question wording and question order for further information). All of our survey reports include a topline questionnaire that provides the exact question wording and sequencing, along with results from the current survey and previous surveys in which we asked the question.

The Center’s transition from conducting U.S. surveys by live telephone interviewing to an online panel (around 2014 to 2020) complicated some opinion trends, but not others. Opinion trends that ask about sensitive topics (e.g., personal finances or attending religious services ) or that elicited volunteered answers (e.g., “neither” or “don’t know”) over the phone tended to show larger differences than other trends when shifting from phone polls to the online ATP. The Center adopted several strategies for coping with changes to data trends that may be related to this change in methodology. If there is evidence suggesting that a change in a trend stems from switching from phone to online measurement, Center reports flag that possibility for readers to try to head off confusion or erroneous conclusions.

Open- and closed-ended questions

One of the most significant decisions that can affect how people answer questions is whether the question is posed as an open-ended question, where respondents provide a response in their own words, or a closed-ended question, where they are asked to choose from a list of answer choices.

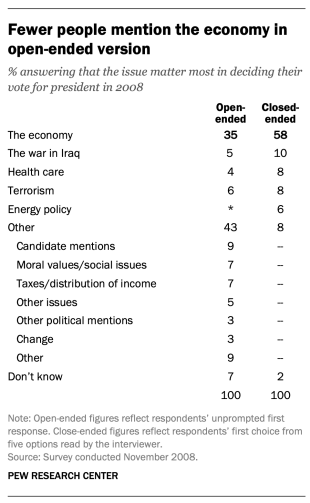

For example, in a poll conducted after the 2008 presidential election, people responded very differently to two versions of the question: “What one issue mattered most to you in deciding how you voted for president?” One was closed-ended and the other open-ended. In the closed-ended version, respondents were provided five options and could volunteer an option not on the list.

When explicitly offered the economy as a response, more than half of respondents (58%) chose this answer; only 35% of those who responded to the open-ended version volunteered the economy. Moreover, among those asked the closed-ended version, fewer than one-in-ten (8%) provided a response other than the five they were read. By contrast, fully 43% of those asked the open-ended version provided a response not listed in the closed-ended version of the question. All of the other issues were chosen at least slightly more often when explicitly offered in the closed-ended version than in the open-ended version. (Also see “High Marks for the Campaign, a High Bar for Obama” for more information.)

Researchers will sometimes conduct a pilot study using open-ended questions to discover which answers are most common. They will then develop closed-ended questions based off that pilot study that include the most common responses as answer choices. In this way, the questions may better reflect what the public is thinking, how they view a particular issue, or bring certain issues to light that the researchers may not have been aware of.

When asking closed-ended questions, the choice of options provided, how each option is described, the number of response options offered, and the order in which options are read can all influence how people respond. One example of the impact of how categories are defined can be found in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in January 2002. When half of the sample was asked whether it was “more important for President Bush to focus on domestic policy or foreign policy,” 52% chose domestic policy while only 34% said foreign policy. When the category “foreign policy” was narrowed to a specific aspect – “the war on terrorism” – far more people chose it; only 33% chose domestic policy while 52% chose the war on terrorism.

In most circumstances, the number of answer choices should be kept to a relatively small number – just four or perhaps five at most – especially in telephone surveys. Psychological research indicates that people have a hard time keeping more than this number of choices in mind at one time. When the question is asking about an objective fact and/or demographics, such as the religious affiliation of the respondent, more categories can be used. In fact, they are encouraged to ensure inclusivity. For example, Pew Research Center’s standard religion questions include more than 12 different categories, beginning with the most common affiliations (Protestant and Catholic). Most respondents have no trouble with this question because they can expect to see their religious group within that list in a self-administered survey.

In addition to the number and choice of response options offered, the order of answer categories can influence how people respond to closed-ended questions. Research suggests that in telephone surveys respondents more frequently choose items heard later in a list (a “recency effect”), and in self-administered surveys, they tend to choose items at the top of the list (a “primacy” effect).

Because of concerns about the effects of category order on responses to closed-ended questions, many sets of response options in Pew Research Center’s surveys are programmed to be randomized to ensure that the options are not asked in the same order for each respondent. Rotating or randomizing means that questions or items in a list are not asked in the same order to each respondent. Answers to questions are sometimes affected by questions that precede them. By presenting questions in a different order to each respondent, we ensure that each question gets asked in the same context as every other question the same number of times (e.g., first, last or any position in between). This does not eliminate the potential impact of previous questions on the current question, but it does ensure that this bias is spread randomly across all of the questions or items in the list. For instance, in the example discussed above about what issue mattered most in people’s vote, the order of the five issues in the closed-ended version of the question was randomized so that no one issue appeared early or late in the list for all respondents. Randomization of response items does not eliminate order effects, but it does ensure that this type of bias is spread randomly.

Questions with ordinal response categories – those with an underlying order (e.g., excellent, good, only fair, poor OR very favorable, mostly favorable, mostly unfavorable, very unfavorable) – are generally not randomized because the order of the categories conveys important information to help respondents answer the question. Generally, these types of scales should be presented in order so respondents can easily place their responses along the continuum, but the order can be reversed for some respondents. For example, in one of Pew Research Center’s questions about abortion, half of the sample is asked whether abortion should be “legal in all cases, legal in most cases, illegal in most cases, illegal in all cases,” while the other half of the sample is asked the same question with the response categories read in reverse order, starting with “illegal in all cases.” Again, reversing the order does not eliminate the recency effect but distributes it randomly across the population.

Question wording

The choice of words and phrases in a question is critical in expressing the meaning and intent of the question to the respondent and ensuring that all respondents interpret the question the same way. Even small wording differences can substantially affect the answers people provide.

[View more Methods 101 Videos ]

An example of a wording difference that had a significant impact on responses comes from a January 2003 Pew Research Center survey. When people were asked whether they would “favor or oppose taking military action in Iraq to end Saddam Hussein’s rule,” 68% said they favored military action while 25% said they opposed military action. However, when asked whether they would “favor or oppose taking military action in Iraq to end Saddam Hussein’s rule even if it meant that U.S. forces might suffer thousands of casualties, ” responses were dramatically different; only 43% said they favored military action, while 48% said they opposed it. The introduction of U.S. casualties altered the context of the question and influenced whether people favored or opposed military action in Iraq.

There has been a substantial amount of research to gauge the impact of different ways of asking questions and how to minimize differences in the way respondents interpret what is being asked. The issues related to question wording are more numerous than can be treated adequately in this short space, but below are a few of the important things to consider:

First, it is important to ask questions that are clear and specific and that each respondent will be able to answer. If a question is open-ended, it should be evident to respondents that they can answer in their own words and what type of response they should provide (an issue or problem, a month, number of days, etc.). Closed-ended questions should include all reasonable responses (i.e., the list of options is exhaustive) and the response categories should not overlap (i.e., response options should be mutually exclusive). Further, it is important to discern when it is best to use forced-choice close-ended questions (often denoted with a radio button in online surveys) versus “select-all-that-apply” lists (or check-all boxes). A 2019 Center study found that forced-choice questions tend to yield more accurate responses, especially for sensitive questions. Based on that research, the Center generally avoids using select-all-that-apply questions.

It is also important to ask only one question at a time. Questions that ask respondents to evaluate more than one concept (known as double-barreled questions) – such as “How much confidence do you have in President Obama to handle domestic and foreign policy?” – are difficult for respondents to answer and often lead to responses that are difficult to interpret. In this example, it would be more effective to ask two separate questions, one about domestic policy and another about foreign policy.

In general, questions that use simple and concrete language are more easily understood by respondents. It is especially important to consider the education level of the survey population when thinking about how easy it will be for respondents to interpret and answer a question. Double negatives (e.g., do you favor or oppose not allowing gays and lesbians to legally marry) or unfamiliar abbreviations or jargon (e.g., ANWR instead of Arctic National Wildlife Refuge) can result in respondent confusion and should be avoided.

Similarly, it is important to consider whether certain words may be viewed as biased or potentially offensive to some respondents, as well as the emotional reaction that some words may provoke. For example, in a 2005 Pew Research Center survey, 51% of respondents said they favored “making it legal for doctors to give terminally ill patients the means to end their lives,” but only 44% said they favored “making it legal for doctors to assist terminally ill patients in committing suicide.” Although both versions of the question are asking about the same thing, the reaction of respondents was different. In another example, respondents have reacted differently to questions using the word “welfare” as opposed to the more generic “assistance to the poor.” Several experiments have shown that there is much greater public support for expanding “assistance to the poor” than for expanding “welfare.”

We often write two versions of a question and ask half of the survey sample one version of the question and the other half the second version. Thus, we say we have two forms of the questionnaire. Respondents are assigned randomly to receive either form, so we can assume that the two groups of respondents are essentially identical. On questions where two versions are used, significant differences in the answers between the two forms tell us that the difference is a result of the way we worded the two versions.

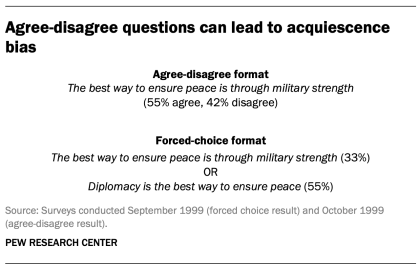

One of the most common formats used in survey questions is the “agree-disagree” format. In this type of question, respondents are asked whether they agree or disagree with a particular statement. Research has shown that, compared with the better educated and better informed, less educated and less informed respondents have a greater tendency to agree with such statements. This is sometimes called an “acquiescence bias” (since some kinds of respondents are more likely to acquiesce to the assertion than are others). This behavior is even more pronounced when there’s an interviewer present, rather than when the survey is self-administered. A better practice is to offer respondents a choice between alternative statements. A Pew Research Center experiment with one of its routinely asked values questions illustrates the difference that question format can make. Not only does the forced choice format yield a very different result overall from the agree-disagree format, but the pattern of answers between respondents with more or less formal education also tends to be very different.

One other challenge in developing questionnaires is what is called “social desirability bias.” People have a natural tendency to want to be accepted and liked, and this may lead people to provide inaccurate answers to questions that deal with sensitive subjects. Research has shown that respondents understate alcohol and drug use, tax evasion and racial bias. They also may overstate church attendance, charitable contributions and the likelihood that they will vote in an election. Researchers attempt to account for this potential bias in crafting questions about these topics. For instance, when Pew Research Center surveys ask about past voting behavior, it is important to note that circumstances may have prevented the respondent from voting: “In the 2012 presidential election between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney, did things come up that kept you from voting, or did you happen to vote?” The choice of response options can also make it easier for people to be honest. For example, a question about church attendance might include three of six response options that indicate infrequent attendance. Research has also shown that social desirability bias can be greater when an interviewer is present (e.g., telephone and face-to-face surveys) than when respondents complete the survey themselves (e.g., paper and web surveys).

Lastly, because slight modifications in question wording can affect responses, identical question wording should be used when the intention is to compare results to those from earlier surveys. Similarly, because question wording and responses can vary based on the mode used to survey respondents, researchers should carefully evaluate the likely effects on trend measurements if a different survey mode will be used to assess change in opinion over time.

Question order

Once the survey questions are developed, particular attention should be paid to how they are ordered in the questionnaire. Surveyors must be attentive to how questions early in a questionnaire may have unintended effects on how respondents answer subsequent questions. Researchers have demonstrated that the order in which questions are asked can influence how people respond; earlier questions can unintentionally provide context for the questions that follow (these effects are called “order effects”).

One kind of order effect can be seen in responses to open-ended questions. Pew Research Center surveys generally ask open-ended questions about national problems, opinions about leaders and similar topics near the beginning of the questionnaire. If closed-ended questions that relate to the topic are placed before the open-ended question, respondents are much more likely to mention concepts or considerations raised in those earlier questions when responding to the open-ended question.

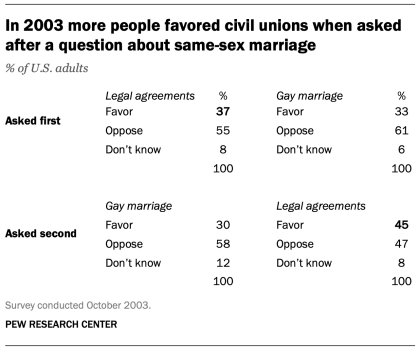

For closed-ended opinion questions, there are two main types of order effects: contrast effects ( where the order results in greater differences in responses), and assimilation effects (where responses are more similar as a result of their order).

An example of a contrast effect can be seen in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in October 2003, a dozen years before same-sex marriage was legalized in the U.S. That poll found that people were more likely to favor allowing gays and lesbians to enter into legal agreements that give them the same rights as married couples when this question was asked after one about whether they favored or opposed allowing gays and lesbians to marry (45% favored legal agreements when asked after the marriage question, but 37% favored legal agreements without the immediate preceding context of a question about same-sex marriage). Responses to the question about same-sex marriage, meanwhile, were not significantly affected by its placement before or after the legal agreements question.

Another experiment embedded in a December 2008 Pew Research Center poll also resulted in a contrast effect. When people were asked “All in all, are you satisfied or dissatisfied with the way things are going in this country today?” immediately after having been asked “Do you approve or disapprove of the way George W. Bush is handling his job as president?”; 88% said they were dissatisfied, compared with only 78% without the context of the prior question.

Responses to presidential approval remained relatively unchanged whether national satisfaction was asked before or after it. A similar finding occurred in December 2004 when both satisfaction and presidential approval were much higher (57% were dissatisfied when Bush approval was asked first vs. 51% when general satisfaction was asked first).

Several studies also have shown that asking a more specific question before a more general question (e.g., asking about happiness with one’s marriage before asking about one’s overall happiness) can result in a contrast effect. Although some exceptions have been found, people tend to avoid redundancy by excluding the more specific question from the general rating.

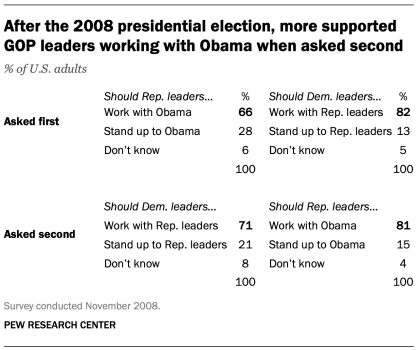

Assimilation effects occur when responses to two questions are more consistent or closer together because of their placement in the questionnaire. We found an example of an assimilation effect in a Pew Research Center poll conducted in November 2008 when we asked whether Republican leaders should work with Obama or stand up to him on important issues and whether Democratic leaders should work with Republican leaders or stand up to them on important issues. People were more likely to say that Republican leaders should work with Obama when the question was preceded by the one asking what Democratic leaders should do in working with Republican leaders (81% vs. 66%). However, when people were first asked about Republican leaders working with Obama, fewer said that Democratic leaders should work with Republican leaders (71% vs. 82%).

The order questions are asked is of particular importance when tracking trends over time. As a result, care should be taken to ensure that the context is similar each time a question is asked. Modifying the context of the question could call into question any observed changes over time (see measuring change over time for more information).

A questionnaire, like a conversation, should be grouped by topic and unfold in a logical order. It is often helpful to begin the survey with simple questions that respondents will find interesting and engaging. Throughout the survey, an effort should be made to keep the survey interesting and not overburden respondents with several difficult questions right after one another. Demographic questions such as income, education or age should not be asked near the beginning of a survey unless they are needed to determine eligibility for the survey or for routing respondents through particular sections of the questionnaire. Even then, it is best to precede such items with more interesting and engaging questions. One virtue of survey panels like the ATP is that demographic questions usually only need to be asked once a year, not in each survey.

U.S. Surveys

Other research methods, sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

Effective writing instruction for students in grades 6 to 12: a best evidence meta-analysis

- Published: 24 April 2024

Cite this article

- Steve Graham ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6702-5865 1 ,

- Yucheng Cao 2 ,

- Young-Suk Grace Kim 3 ,

- Joongwon Lee 4 ,

- Tamara Tate 3 ,

- Penelope Collins 3 ,

- Minkyung Cho 3 ,

- Youngsun Moon 3 ,

- Huy Quoc Chung 3 &

- Carol Booth Olson 3

13 Accesses

Explore all metrics

The current best evidence meta-analysis reanalyzed the data from a meta-analysis by Graham et al. (J Educ Psychol 115:1004–1027, 2023). This meta-analysis and the prior one examined if teaching writing improved the writing of students in Grades 6 to 12, examining effects from writing intervention studies employing experimental and quasi-experimental designs (with pretests). In contrast to the prior meta-analysis, we eliminated all N of 1 treatment/control comparisons, studies with an attrition rate over 20%, studies that did not control for teacher effects, and studies that did not contain at least one reliable writing measure (0.70 or greater). Any writing outcome that was not reliable was also eliminated. Across 148 independent treatment/control comparisons, yielding 1,076 writing effect sizes (ESs) involving 22,838 students, teaching writing resulted in a positive and statistically detectable impact on students’ writing (ES = 0.38). Further, six of the 10 writing treatments tested in four or more independent comparisons improved students’ performance. This included the process approach to writing (0.75), strategy instruction (0.59), transcription instruction (0.54), feedback (0.30), pre-writing activities (0.32), and peer assistance (0.59). In addition, the Self-Regulated Strategy Development model for teaching writing strategies yielded a statistically significant ES of 0.84, whereas other approaches to teaching writing strategies resulted in a statistically significant ES of 0.51. The findings from this meta-analysis and the Graham et al. (2023) review which included studies that were methodologically weaker were compared. Implications for practice, research, and theory are presented.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Improving Writing Skills of Students in Turkey: a Meta-analysis of Writing Interventions

Best Practices in Writing Instruction for Students with Learning Disabilities

The effectiveness of self-regulated strategy development on improving English writing: Evidence from the last decade

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis.

*Adams, V., (1971). A study of the effects of two methods of teaching composition to twelfth Graders [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Aiken, L., West, S., Schwalm, D., Carroll, J., & Hsiung, S. (1998). Comparison of a randomized and two quasi-experimental designs in a single outcome evaluation. Evaluation Review, 22 , 207–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X9802200203

Article Google Scholar

*Al Shaheb, M. N. A. (n.d.). The effect of self-regulated strategy development on persuasive writing, self-efficacy, and attitude: A mixed-methods, quasi-experimental study in Grade 6 in Lebanon [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Université Saint-Joseph, Beirut, Lebanon.

Applebee, A., & Langer, J. (2011). A snapshot of writing instruction in middle schools and high schools. English Journal, 100 , 14–27.

Bangert-Drowns, R. (1993). The word processor as an instructional tool: A meta-analysis of word processing in writing instruction. Review of Educational Research, 63 , 69–93. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543063001069

Bangert-Drowns, R., Hurley, M., & Wilkinson, B. (2004). The effects of school-based writing to-learn interventions on academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 74 (1), 29–58. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001029

*Barrot, J. S. (2018). Using the sociocognitive-transformative approach in writing classrooms: Effects on L2 learners’ writing performance. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 34 (2), 187–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2017.1387631

*Barton, H. (2018). Writing, collaborating, and cultivating: Building writing self-efficacy and skills through a student-centric, student-led writing center . Doctor of Education in Secondary Education Dissertations. 13 . https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/seceddoc_etd/13

*Benson, N. L. (1979). The effects of peer feedback during the writing process on writing performance, revision behavior, and attitude toward writing [Unpublished doctoral dissertation] University of Colorado.

*Berman, R. (1994). Learners’ transfer of writing skills between languages. TESL Canada Journal, 12 (1), 29–46.

*Black, J. G. (1995). Teaching elements of written composition through use of classical music and art: the effects on high school students' writing [Unpublished doctoral dissertation] University of California, Riverside.

Bloom, B., Engelhart, M., Furst, E., Hill, W., & Krathwohl, D. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive domain . David McKay Company.

*Braaksma, M. (2002). Observational learning in argumentative writing [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam.

*Braaksma, M., Rijlaarsdam, G. C. W., & van den Bergh, H. H. (2018). Effects of hypertext writing and observational learning on content knowledge acquisition, self-efficacy, and text quality: Two experimental studies exploring aptitude treatment interactions. Journal of Writing Research, 9 (3), 259–300. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2018.09.03.02

*Brantley, H., & Small, D. (1991). Effects of self evaluation on written composition skill in learning disabled children . U.S. Department of Education.

Google Scholar

*Brewer, D. (2002). Teaching writing in science through the use of a writing rubric [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Michigan-Flint.

Cheung, A., & Slavin, R. (2016). How methodological features affect effect sizes in education. Educational Researcher, 45 , 283–292. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X16656615

*Christensen, C. A. (2004). Relationship between orthographic-motor integration and computer use for the production of creative and well-structured written text. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74 (4), 551–564. https://doi.org/10.1348/0007099042376373

*Chung, H. Q., Chen, V., & Olson, C. B. (2021). The impact of self-assessment, planning and goal setting, and reflection before and after revision on student self-efficacy and writing performance. Reading and Writing, 34 , 1885–1913. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-021-10186-x

*Combs, W. E. (1976). Further effects of sentence-combining practice on writing ability. Research in the Teaching of English, 10 (2), 137–149.

*Combs, W. E. (1977). Sentence-combining practice: Do gains in judgments of writing “quality” persist? The Journal of Educational Research, 70 (6), 318–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1977.10885014

*Conklin, E. (2007). Concept mapping: Impact on content and organization of technical writing in science [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Walden University.

*Corey, D. R. (1990). The effects of concurrent instruction in composition and speech upon the composition writing holistic scores and sense of audience of a ninth-grade student population [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. The Union for Experimenting Colleges and Universities.

Cortina, J., & Nouri, H. (2000). Effect size for ANOVA design . Sage.

Book Google Scholar

*Couzijn, M., & Rijlaarsdam, G. (2004). Learning to read and write argumentative text by observation of peer learners. In Rijlaarsdam, G. (Series Ed.) & Rijlaarsdam, G., van den Bergh, H., & Couzijn, M. (Vol. 14 Eds.), Effective learning and teaching of writing , (pp. 241–258). Springer.

Couzijn, M., & Rijlaarsdam, G. (2005). Learning to write instructive texts by reader observation and written feedback. In G. Rijlaarsdam, H. van den Bergh, & M. Couzijn (Eds.), Effective learning and teaching of writing (pp. 209–240). Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

*Covill, A. E. (1996). Students' revision practices and attitudes in response to surface-related feedback as compared to content-related feedback on their writing [Unpublished doctoral dissertation] University of Washington.

*Cremin, T., Myhill, D., Eyres, I., Nash, T., Wilson, A., & Oliver, L. (2020). Teachers as writers: Learning together with others. Literacy, 54 (2), 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12201

*Crook, J. D. (1985). Effects of computer-assisted instruction upon seventh-grade students’ growth in writing performance [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Nebraska.

*Crossley, S. A., Roscoe, R., & McNamara, D. S. (2013). Using automated scoring models to detect changes in student writing in an intelligent tutoring system. Paper presented at Proceedings of the Twenty-sixth International Florida Artificial Intelligence Research Society Conference, Florida.

*Crossley, S. A., Varner, L. K., Roscoe, R. D., & McNamara, D. S. (2013). Using automated indices of cohesion to evaluate an intelligent tutoring system and an automated writing evaluation system. In Artificial intelligence in education: 16th international conference, AIED 2013 , Memphis, TN, USA, July 9–13, 2013. Proceedings 16 (pp. 269-278). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

*Dailey, E. M. (1992). The relative efficacy of cooperative learning versus individualized learning on the written performance of adolescent students with writing problems [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. The Johns Hopkins University.

*Daiute, C., & Kruidenier, J. (1985). A self-questioning strategy to increase young writers’ revising processes. Applied Psycholinguistics, 6 , 307–318. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716400006226

*de la Paz, S., & Graham, S. (2002). Explicitly teaching strategies, skills, and knowledge: Writing instruction in middle school classrooms. Journal of Educational Psychology, 94 (4), 687. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-0663.94.4.687

*de la Paz, S., & Wissinger, D. R. (2017). Improving the historical knowledge and writing of students with or at risk for LD. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 50 (6), 658–671. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219416659444

*de la Paz, S., Wissinger, D. R., Gross, M., & Butler, C. (in press). Strategies that promote historical reasoning and contextualization: A pilot intervention with urban high school students. Reading and Writing .

*de Ment, L. (2008). The Relationship of self-evaluation, writing ability, and attitudes toward writing among gifted grade 7 language arts students [Unpublished master’s thesis] Walden University.

*de Smedt, F., & van Keer, H. (2018). Fostering writing in upper primary grades: A study into the distinct and combined impact of explicit instruction and peer assistance. Reading and Writing, 31 , 325–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-017-9787-4

*de Smedt, F., Graham, S., & van Keer, H. (2019). The bright and dark side of writing motivation: Effects of explicit instruction and peer assistance. The Journal of Educational Research, 112 (2), 152–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2018.1461598

*de Smedt, F., Graham, S., & Van Keer, H. (2020). “It takes two” : The added value of structured peer-assisted writing in explicit writing instruction. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 60 , 101835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.101835

Drew, S., Olinghouse, N., Luby-Faggella, M., & Welsh, M. (2017). Framework for disciplinary writing in science Grades 6–12: A national survey. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109 , 935–955. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000186

Dunnagan, K. L. (1990). Seventh grade students’ audience awareness in writing produced within and without the dramatic mode [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. The Ohio State University.

*Eliason, R. G. (1994). The effect of selected word processing adjunct programs on the writing of high school students (Publication No. 0426055) [Doctoral dissertation]. University of South Florida.

*Erickson, D. K. (2009). The effects of blogs versus dialogue journals on open-response writing scores and attitudes of grade eight science students (Publication No. 3393920) [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Massachusetts, Lowell. ProQuest LLC.

*Espinoza, S. F. (1992). The effects of using a word processor containing grammar and spell checkers on the composition writing of sixth graders [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Texas Tech University.

*Festas, I., Oliveira, A. L., Rebelo, J. A., Damião, M. H., Harris, K., & Graham, S. (2015). Professional development in self-regulated strategy development: Effects on the writing performance of eighth grade Portuguese students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 40 , 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.05.004

Fisher, Z., Tipton, E., & Zhipeng, H. (2017). Package ' robumeta'. Retrieved from http://cran.uni-muenster.de/web/packages/robumeta/robumeta.pdf

*Frank, A. R. (2008). The effect of instruction in orthographic conventions and morphological features on the reading fluency and comprehension skills of high-school freshmen [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. The University of San Francisco.

*Franzke, M., Kintsch, E., Caccamise, D., Johnson, N., & Dooley, S. (2005). Summary Street®: Computer support for comprehension and writing. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 33 (1), 53–80. https://doi.org/10.2190/DH8F-QJWM-J457-FQVB

*Frost, K. L. (2008). The effects of automated essay scoring as a high school classroom intervention (Publication No. 3352171) [Doctoral dissertation], University of Nevada, Las Vegas. ProQuest LLC.

*Galbraith, J. (2014). The effect of self-regulation writing strategies and gender on writing self-efficacy and persuasive writing achievement for secondary students [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Western Connecticut State University.

*Ganong, F. L. (1974). Teaching writing through the use of a program based on the work of Donald M. Murray [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Boston University.

Goldberg, A., Russell, M., & Cook, A. (2003). The effect of computers on student writing: A meta-analysis of studies from 1992 to 2002. The Journal of Technology, Learning, and Assessment 2 (1). Retrived from https://ejournals.bc.edu/index.php/jtla/article/view/1661

*González-Lamas, J., Cuevas, I., & Mateos, M. (2016). Arguing from sources: Design and evaluation of a programme to improve written argumentation and its impact according to students’ writing beliefs. Journal for the Study of Education and Development, 39 (1), 49–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/02103702.2015.111160

*Grejda, G. F. (1988). The effects of word processing and revision patterns on the writing quality of sixth-grade students (Publication No. 8909998) [Doctoral dissertation], Pennsylvania State University.

Graham, S. (2019). Changing how writing is taught. Review of Research in Education, 43 , 277–303. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X18821125

Graham, S. (2018). A revised writer(s)-within-community model of writing. Educational Psychologist, 53 , 258–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2018.1481406

Graham, S. (2015). Inaugural editorial for the journal of educational psychology. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107 , 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000007

Graham, S., & Harris, K. R. (2018). Evidence-based writing practices: A meta-analysis of existing meta-analyses. In R. Fidalgo, K. R. Harris, & M. Braaksma (Eds.). Design principles for teaching effective writing: Theoretical and empirical grounded principles (pp. 13–37). Hershey, PA: Brill Editions.

Graham, S., & Harris, K. R. (1997). It can be taught, but it does not develop naturally: Myths and realities in writing instruction. School Psychology Review, 26 , 414–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.1997.12085875

Graham, S., & Harris, K. R. (2014). Conducting high quality writing intervention research: Twelve recommendations. Journal of Writing Research 6, 89–123. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2014.06.02.1

Graham, S., & Hebert, M. (2011). Writing-to-read: A meta-analysis of the impact of writing and writing instruction on reading. Harvard Educational Review, 81, 710–744. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.81.4.t2k0m13756113566

Graham, S., Hebert, M., & Harris, K. R. (2015). Formative assessment and writing: A meta-analysis. Elementary School Journal, 115 , 524–547. https://doi.org/10.1086/681947

Graham, S., Kim, Y., Cao, Y., Lee, W., Tate, T., Collins, T., Cho, M., Moon, Y., Chung, H., & Olson, C. (2023). A meta-analysis of writing treatments for students in Grades 6 to 12. Journal of Educational Psychology, 115 , 1004–1027. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000819

Graham, S., Kiuhara, S., & MacKay, M. (2020). The effects of writing on learning in science, social studies, and mathematics: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 90 , 179–226. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654320914744

Graham, S., Kiuhara, S., McKeown, D., & Harris, K. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of writing instruction for students in the elementary grades. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104 , 879–896. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029185

Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). A meta-analysis of writing instruction for adolescent students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99 , 445–476. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.3.445