Research Process Guide

- Step 1 - Identifying and Developing a Topic

- Step 2 - Narrowing Your Topic

- Step 3 - Developing Research Questions

- Step 4 - Conducting a Literature Review

- Step 5 - Choosing a Conceptual or Theoretical Framework

- Step 6 - Determining Research Methodology

- Step 6a - Determining Research Methodology - Quantitative Research Methods

- Step 6b - Determining Research Methodology - Qualitative Design

- Step 7 - Considering Ethical Issues in Research with Human Subjects - Institutional Review Board (IRB)

- Step 8 - Collecting Data

- Step 9 - Analyzing Data

- Step 10 - Interpreting Results

- Step 11 - Writing Up Results

Step 1: Identifying and Developing a Topic

Whatever your field or discipline, the best advice to give on identifying a research topic is to choose something that you find really interesting. You will be spending an enormous amount of time with your topic, you need to be invested. Over the course of your research design, proposal and actually conducting your study, you may feel like you are really tired of your topic, however, your interest and investment in the topic will help you persist through dissertation defense. Identifying a research topic can be challenging. Most of the research that has been completed on the process of conducting research fails to examine the preliminary stages of the interactive and self-reflective process of identifying a research topic (Wintersberger & Saunders, 2020). You may choose a topic at the beginning of the process, and through exploring the research that has already been done, one’s own interests that are narrowed or expanded in scope, the topic will change over time (Dwarkadas & Lin, 2019). Where do I begin? According to the research, there are generally two paths to exploring your research topic, creative path and the rational path (Saunders et al., 2019). The rational path takes a linear path and deals with questions we need to ask ourselves like: what are some timely topics in my field in the media right now?; what strengths do I bring to the research?; what are the gaps in the research about the area of research interest? (Saunders et al., 2019; Wintersberger & Saunders, 2020).The creative path is less linear in that it may include keeping a notebook of ideas based on discussion in coursework or with your peers in the field. Whichever path you take, you will inevitably have to narrow your more generalized ideas down. A great way to do that is to continue reading the literature about and around your topic looking for gaps that could be explored. Also, try engaging in meaningful discussions with experts in your field to get their take on your research ideas (Saunders et al., 2019; Wintersberger & Saunders, 2020). It is important to remember that a research topic should be (Dwarkadas & Lin, 2019; Saunders et al., 2019; Wintersberger & Saunders, 2020):

- Interesting to you.

- Realistic in that it can be completed in an appropriate amount of time.

- Relevant to your program or field of study.

- Not widely researched.

Dwarkadas, S., & Lin, M. C. (2019, August 04). Finding a research topic. Computing Research Association for Women, Portland State University. https://cra.org/cra-wp/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/04/FindingResearchTopic/2019.pdf

Saunders, M. N. K., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2019). Research methods for business students (8th ed.). Pearson.

Wintersberger, D., & Saunders, M. (2020). Formulating and clarifying the research topic: Insights and a guide for the production management research community. Production, 30 . https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-6513.20200059

- Last Updated: Jun 29, 2023 1:35 PM

- URL: https://libguides.kean.edu/ResearchProcessGuide

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, frequently asked questions.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities – start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships, while descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends, and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analysing the data.

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study – plants, animals, organisations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region, or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalise your results to the population as a whole.

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study, your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalise to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question.

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviours, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews.

Observation methods

Observations allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviours, or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected – for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are reliable and valid.

Operationalisation

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalisation means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in – for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced , while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method, you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample – by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method, it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method, how will you avoid bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organising and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymise and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well organised will save time when it comes to analysing them. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings.

On their own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyse the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarise your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarise your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

There are many other ways of analysing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, March 20). Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 29 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

How friends helped fuel the rise of a relentless enemy

Alcohol is dangerous. So is ‘alcoholic.’

How old is too old to run?

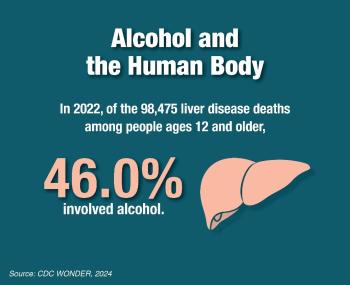

Getting ahead of liver cancer.

Researchers hope identifying blood proteins may lead to earlier prediction of risk, increase treatment options

Rachel Troy

Mass General Brigham Communications

A new study suggests that proteins detectable in the blood could improve predictions about risk of liver cancer, which is typically diagnosed at later stages when survival rates are lower.

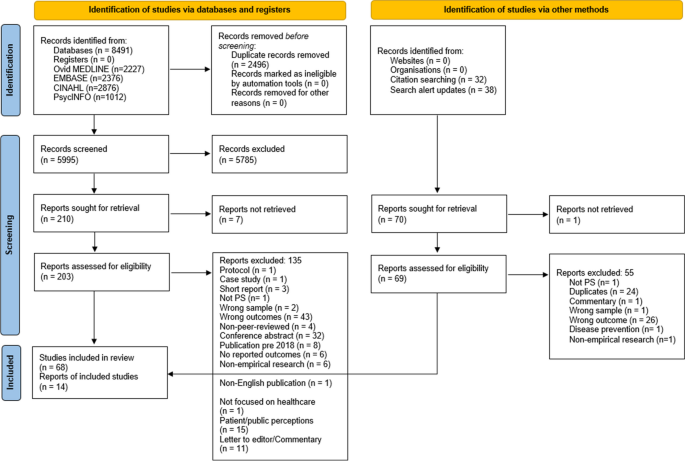

Led by investigators at Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Mass General Brigham, the team’s results are published in JNCI.

Liver cancer, or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), ranks as the third leading cause of cancer worldwide and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally, with its incidence rate steadily increasing. Detection of liver cancers often occurs at advanced stages, when life expectancy typically spans less than 12 months. Currently, there is a notable deficiency in accurate, sensitive, and specific tools for the early detection of liver cancer. Many existing methods are relatively expensive, invasive, or limited in accessibility, primarily confined to major hospitals.

“Liver cancer rates are rapidly increasing, and liver cancer has a high mortality rate, but if we can diagnose it early, therapeutic interventions can be potentially curative.” Xinyuan Zhang, BWH

The team used proteomics, the study and profiling of proteins, to develop a minimally invasive model for diagnosing or screening for liver cancer at an earlier, more treatable stage. Using the SomaScan Assay Kit — a high-throughput proteomics platform that measures protein levels in biological samples, available through BIDMC’s Genomics, Proteomics, Bioinformatics and Systems Biology Center — the investigators detected 1,305 biologically relevant proteins that may be present in the blood at early stage of disease.

“Liver cancer rates are rapidly increasing, and liver cancer has a high mortality rate, but if we can diagnose it early, therapeutic interventions can be potentially curative,” said lead author Xinyuan (Cindy) Zhang of the Channing Division of Network Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. “We need to have a way to detect this form of cancer early enough to intervene with surgery or liver transplantation to treat the disease before it becomes metastatic.”

The study team used SomaScan to analyze plasma samples from participants in both the Nurses’ Health Study and the Health Professional Follow-Up Study, two longitudinal, ongoing, prospective cohorts in the U.S. Notably, they examined blood samples obtained from patients an average of 12 years before their liver cancer diagnosis to pinpoint protein biomarker signals. After examination, the researchers cross-referenced medical records to confirm whether these patients ultimately developed liver cancer.

From the blood samples, the researchers identified 56 plasma proteins that showed significantly elevated levels in patients with liver cancer compared to matched control samples without HCC. The team selected four of these proteins to create a predictive model, which they tested on the U.K. Biobank Pharma Proteomics dataset, comprised of 50,000 individuals, 45 of whom were diagnosed with liver cancer. Their model had greater accuracy in predicting liver cancer compared to traditional risk factors.

The authors caution that their study included a limited number of liver cancer cases and further validation in larger, more diverse patient populations and in high-risk populations is needed.

“It’s always been challenging to identify highly specific disease biomarkers in the blood using traditional tools, but new technology allows us to detect a broad and dynamic range of both high and low abundant proteins,” said co-senior author Towia A. Libermann of the division of Interdisciplinary Medicine and Biotechnology at BIDMC. “New insights into the biological mechanisms underlying liver cancer development emerge from our data that may lead to identification of novel therapeutic targets. Most importantly, we were able to validate these early detection biomarkers using alternative protein analysis techniques and in an independent population cohort from the U.K.”

The study team aims to extend their methodology to uncover additional plasma protein biomarkers, explore biomarkers linked with different cancer types, and gain deeper insights into the role of HCC risk factors across specific patient populations. With further progress, the protein biomarkers investigated in the study could potentially hold clinical significance as a non-invasive test for assessing liver cancer risk.

“Even though further investigation in additional populations is needed, our results reveal a robust circulating protein profile associated with liver cancer years before diagnosis, which is truly remarkable,” said co-senior author Xuehong Zhang, who conducted work on this study while at the Channing Division of Network Medicine at the Brigham. Zhang is now at Yale

Additional authors include Long H. Ngo, Simon T. Dillon, Xuesong Gu and Michelle Lai, of BIDMC; Longgang Zhao of BWH; Tracey G. Simon and Andrew T. Chan of MGH; and Edward L. Giovannucci of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Cancer Institute (NCI) through grants R21 CA238651. Andrew T. Chan served as a consultant for Bayer Pharma AG, Pfizer Inc., and Boehringer Ingelheim for work unrelated to this topic. He has also received grant support from Pfizer Inc., Zoe Ltd, and Freenome for work unrelated to this topic.

Share this article

You might like.

Economists imagine an alternate universe where the opioid crisis peaked in ’06, and then explain why it didn’t

Researcher explains the human toll of language that makes addiction feel worse

No such thing, specialist says — but when your body is trying to tell you something, listen

Seem like Lyme disease risk is getting worse? It is.

The risk of Lyme disease has increased due to climate change and warmer temperature. A rheumatologist offers advice on how to best avoid ticks while going outdoors.

- 我的GMAT 我的班课 我的1V1 练习记录 活动中心

应版权方要求,不支持在线看题功能,感谢您的理解。

讨论题目 或 发起提问

- PREP07 Test 1

- PREP07 Test 2

- PREP08 Test 1

- PREP08 Test 2

题目来源7:OG2022

- Peterborough

The Research Plan

Where to start with scholarly research, expectations for research, scholarly vs. popular sources, grey literature, primary vs. secondary sources, preliminary research.

- Create a Plan

A good essay is grounded in good research, which requires clear direction, patience and persistence.

Research helps you to focus your topic, formulate and refine your thesis, and discover details, opinions, and facts to support your overall argument. You are better equipped to search for and sort sources when you have made decisions about your topic and developed a working thesis.

It is important that your research be accurate, reliable, relevant, and, for many disciplines, recent. The quality of your research determines the efficacy of your argument and your instructor’s assessment of your work.

Maintaining your academic integrity is an important factor that is assessed by your professors. The sources you use must be properly documented, accurately communicated, and clearly explained in relation to your topic and thesis. You are less likely to copy the text word for word or paraphrase too closely if you have spent some time thinking about how the research will inform your thesis and if you think carefully about your research process

Types of Sources

Many assignments will require you to focus primarily on scholarly, peer-reviewed sources. Check with your professor or the assignment instructions for guidance on using popular sources.

Scholarly sources are supported by the peer review process, which means they are sources that have been evaluated by other experts in the same field.

Scholarly sources:

- Are written by and for academics

- Ensure that data is thoroughly checked

- Cite all evidence

- Make arguments which are supported by research

- Meet conventions of scholarship in the discipline

- Are written in formal, academic language

Popular sources are written for a wider, general audience and are more informal in tone. Sources like newspaper articles, documentaries and corporate websites are not scholarly, but they can offer useful information that you can include in your analysis alongside evidence presented by scholarly sources.

Grey literature is produced by entities whose main task is NOT publishing. Industry, think tanks, government departments, scholarly societies and associations can all produce grey literature. Grey literature can include reports, working papers, newsletters, government documents, speeches, white papers, and urban plans. Grey literature also includes newsletters, emails, blogs and other social networking sites. In addition to scholarly sources, grey literature can offer valuable evidence to your essay, but be sure to consider whether its use is appropriate for the discipline, the course, or the assignment.

In some disciplines, such as history, philosophy, or English literature, it is important to distinguish between primary and secondary sources.

Primary sources are original, first-hand materials. A primary source may be a government document, census data, a short story, old letters, or a piece of art.

Secondary source s are articles, editorials, textbooks, books, and other published materials that may interpret data, works of literature, ideas or events.

You may need to do preliminary research to find or refine a topic. Some early reading can help you narrow your focus, establish research questions, and avoid the frustration of directionless research.

Places to Start

- Begin with course materials. The syllabus, required or recommended readings, textbooks and lecture notes will often provide ideas for a topic, while focusing on the major themes of your course.

- During the early stages of research, you can use reference works, such as discipline-specific textbooks, encyclopedias and dictionaries, or Wikipedia, for an introduction to your topic. Use the library subject guide to find useful reference works in your subject. Be sure that only material from your scholarly research, not Wikipedia , is used and cited in your paper.

The materials found during the preliminary research stage can help you to identify main concepts, key terminology, and important literature on the topic.

Planning your Research

A plan establishes research goals and clarifies direction.

A clear direction and plan for research helps you assess the quality and relevance of sources.

Creating a Research Plan

In advance of beginning a search for evidence, take time to make a plan.

- Develop specific questions about your topic: what do you want to know and how does it relate to your thesis?

- Create a list of key words and synonyms for your search. Include specific and more general terms; establish parameters for your search (place, time, theory, field, species) but be open to related materials.

- Identify types of evidence you are required to use (research requirements of the assignment) and you will find informative for your topic. Think about where you can find these types of sources.

Look to your course content to identify the types of sources commonly used in the discipline; here are some examples:

- Peer-Reviewed scholarship: Argumentative articles, clinical trials, empirical articles (use library databases, google scholar)

- Numerical and financial data: export data, quality of life measures (see library subject guides

- Visual records (maps, old photographs, film)

- NGO documents: Stakeholder reports, Best practice documents

- Government documents: laws, legislation, reports

Research Plan worksheet - Accessible version (Word doc)

FLEET LIBRARY | Research Guides

Rhode island school of design, create a research plan: research plan.

- Research Plan

- Literature Review

- Ulrich's Global Serials Directory

- Related Guides

A research plan is a framework that shows how you intend to approach your topic. The plan can take many forms: a written outline, a narrative, a visual/concept map or timeline. It's a document that will change and develop as you conduct your research. Components of a research plan

1. Research conceptualization - introduces your research question

2. Research methodology - describes your approach to the research question

3. Literature review, critical evaluation and synthesis - systematic approach to locating,

reviewing and evaluating the work (text, exhibitions, critiques, etc) relating to your topic

4. Communication - geared toward an intended audience, shows evidence of your inquiry

Research conceptualization refers to the ability to identify specific research questions, problems or opportunities that are worthy of inquiry. Research conceptualization also includes the skills and discipline that go beyond the initial moment of conception, and which enable the researcher to formulate and develop an idea into something researchable ( Newbury 373).

Research methodology refers to the knowledge and skills required to select and apply appropriate methods to carry through the research project ( Newbury 374) .

Method describes a single mode of proceeding; methodology describes the overall process.

Method - a way of doing anything especially according to a defined and regular plan; a mode of procedure in any activity

Methodology - the study of the direction and implications of empirical research, or the sustainability of techniques employed in it; a method or body of methods used in a particular field of study or activity *Browse a list of research methodology books or this guide on Art & Design Research

Literature Review, critical evaluation & synthesis

A literature review is a systematic approach to locating, reviewing, and evaluating the published work and work in progress of scholars, researchers, and practitioners on a given topic.

Critical evaluation and synthesis is the ability to handle (or process) existing sources. It includes knowledge of the sources of literature and contextual research field within which the person is working ( Newbury 373).

Literature reviews are done for many reasons and situations. Here's a short list:

Sources to consult while conducting a literature review:

Online catalogs of local, regional, national, and special libraries

meta-catalogs such as worldcat , Art Discovery Group , europeana , world digital library or RIBA

subject-specific online article databases (such as the Avery Index, JSTOR, Project Muse)

digital institutional repositories such as Digital Commons @RISD ; see Registry of Open Access Repositories

Open Access Resources recommended by RISD Research LIbrarians

works cited in scholarly books and articles

print bibliographies

the internet-locate major nonprofit, research institutes, museum, university, and government websites

search google scholar to locate grey literature & referenced citations

trade and scholarly publishers

fellow scholars and peers

Communication

Communication refers to the ability to

- structure a coherent line of inquiry

- communicate your findings to your intended audience

- make skilled use of visual material to express ideas for presentations, writing, and the creation of exhibitions ( Newbury 374)

Research plan framework: Newbury, Darren. "Research Training in the Creative Arts and Design." The Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts . Ed. Michael Biggs and Henrik Karlsson. New York: Routledge, 2010. 368-87. Print.

About the author

Except where otherwise noted, this guide is subject to a Creative Commons Attribution license

source document

Routledge Companion to Research in the Arts

- Next: Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Sep 20, 2023 5:05 PM

- URL: https://risd.libguides.com/researchplan

GMAT Problem Solving (PS) Questions

Customized for You

Track Your Progress

Practice Pays

Practice thousands of GMAT questions with top expert solutions.

Identify and improve upon mistakes efficiently using our Error Log.

Get the latest tips and news from our top GMAT professionals.

- it’s free and easy!

Thank you for using the timer! We noticed you are actually not timing your practice. Click the START button first next time you use the timer. There are many benefits to timing your practice , including:

We’ll give you an estimate of your score

We’ll provide personalized question recommendations

Your score will improve and your results will be more realistic

Conquer Algebra on the GMAT Focus Edition

GMAT Online Course at $159 | 2X more Comprehensive Content for GMAT Focus Edition

How to score 655+ on the GMAT in 4 months

GMAT Day: Strategies, Experts, Deals

11:00 AM IST

01:00 PM IST

01:30 PM IST

12:00 PM PDT

11:00 PM PDT

06:45 AM PDT

A researcher plans to identify each participant in a certain medical

Difficulty:

Question Stats:

- GMAT Prep Courses

- MBA Programs

- Build Your Study Plan

- Best GMAT Books

- All the GMAT Tests

- GMAT Focus Tests

- GMAT Verbal

- Error Log Templates

- GMAT Official Guide

- Manhattan Prep

- Target Test Prep

- Experts' Global

- Full Time MBA Rankings

- Part Time MBA Rankings

- Executive MBA Rankings

- International MBA Rankings

- Best App Tips

- Best MBA Books

- Application Reference

- Free Profile Evaluation

Copyright © 2024 GMAT Club

GMAT ® is a registered trademark of the Graduate Management Admission Council ® (GMAC ®). GMAT Club's website has not been reviewed or endorsed by GMAC.

The post is bookmarked successfully

Developing a Research Plan

- First Online: 20 September 2022

Cite this chapter

- Habeeb Adewale Ajimotokan 2

Part of the book series: SpringerBriefs in Applied Sciences and Technology ((BRIEFSAPPLSCIENCES))

967 Accesses

The objectives of this chapter are to

Describe the terms research proposal and research protocol;

Specify and discuss the elements of research proposal;

Specify the goals of research protocol;

Outline preferable sequence for the different section headings of a research protocol and discuss their contents; and

Discuss the basic engineering research tools and techniques.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

5StarEssays. (2020). Writing a research proposal—Outline, format and examples. In Complete guide to writing a research paper . Retrieved from https://www.5staressays.com/blog/writing-research-proposal

Walliman, N. (2011). Research methods: The basics . Routledge—Taylor and Francis Group.

Google Scholar

Olujide, J. O. (2004). Writing a research proposal. In H. A. Saliu & J. O. Oyebanji (Eds.), A guide on research proposal and report writing (Ch. 7, pp. 67–79). Faculty of Business and Social Sciences, Unilorin.

Thiel, D. V. (2014). Research methods for engineers . University Printing House, University of Cambridge.

Book Google Scholar

Mouton, J. (2001). How to succeed in your master’s and doctoral studies. Van Schaik.

Lues, L., & Lategan, L. O. K. (2006). RE: Search ABC (1st ed.). Sun Press.

Bak, N. (2004). Completing your thesis: A practical guide . Van Schaik.

Sadiku, M. N. O. (2000). Numerical techniques in electromagnetics . CRC Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria

Habeeb Adewale Ajimotokan

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Ajimotokan, H.A. (2023). Developing a Research Plan. In: Research Techniques. SpringerBriefs in Applied Sciences and Technology. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13109-7_4

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-13109-7_4

Published : 20 September 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-13108-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-13109-7

eBook Packages : Engineering Engineering (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

How to write a research plan: Step-by-step guide

Last updated

30 January 2024

Reviewed by

Today’s businesses and institutions rely on data and analytics to inform their product and service decisions. These metrics influence how organizations stay competitive and inspire innovation. However, gathering data and insights requires carefully constructed research, and every research project needs a roadmap. This is where a research plan comes into play.

There’s general research planning; then there’s an official, well-executed research plan. Whatever data-driven research project you’re gearing up for, the research plan will be your framework for execution. The plan should also be detailed and thorough, with a diligent set of criteria to formulate your research efforts. Not including these key elements in your plan can be just as harmful as having no plan at all.

Read this step-by-step guide for writing a detailed research plan that can apply to any project, whether it’s scientific, educational, or business-related.

- What is a research plan?

A research plan is a documented overview of a project in its entirety, from end to end. It details the research efforts, participants, and methods needed, along with any anticipated results. It also outlines the project’s goals and mission, creating layers of steps to achieve those goals within a specified timeline.

Without a research plan, you and your team are flying blind, potentially wasting time and resources to pursue research without structured guidance.

The principal investigator, or PI, is responsible for facilitating the research oversight. They will create the research plan and inform team members and stakeholders of every detail relating to the project. The PI will also use the research plan to inform decision-making throughout the project.

- Why do you need a research plan?

Create a research plan before starting any official research to maximize every effort in pursuing and collecting the research data. Crucially, the plan will model the activities needed at each phase of the research project.

Like any roadmap, a research plan serves as a valuable tool providing direction for those involved in the project—both internally and externally. It will keep you and your immediate team organized and task-focused while also providing necessary definitions and timelines so you can execute your project initiatives with full understanding and transparency.

External stakeholders appreciate a working research plan because it’s a great communication tool, documenting progress and changing dynamics as they arise. Any participants of your planned research sessions will be informed about the purpose of your study, while the exercises will be based on the key messaging outlined in the official plan.

Here are some of the benefits of creating a research plan document for every project:

Project organization and structure

Well-informed participants

All stakeholders and teams align in support of the project

Clearly defined project definitions and purposes

Distractions are eliminated, prioritizing task focus

Timely management of individual task schedules and roles

Costly reworks are avoided

- What should a research plan include?

The different aspects of your research plan will depend on the nature of the project. However, most official research plan documents will include the core elements below. Each aims to define the problem statement, devising an official plan for seeking a solution.

Specific project goals and individual objectives

Ideal strategies or methods for reaching those goals

Required resources

Descriptions of the target audience, sample sizes, demographics, and scopes

Key performance indicators (KPIs)

Project background

Research and testing support

Preliminary studies and progress reporting mechanisms

Cost estimates and change order processes

Depending on the research project’s size and scope, your research plan could be brief—perhaps only a few pages of documented plans. Alternatively, it could be a fully comprehensive report. Either way, it’s an essential first step in dictating your project’s facilitation in the most efficient and effective way.

- How to write a research plan for your project

When you start writing your research plan, aim to be detailed about each step, requirement, and idea. The more time you spend curating your research plan, the more precise your research execution efforts will be.

Account for every potential scenario, and be sure to address each and every aspect of the research.

Consider following this flow to develop a great research plan for your project:

Define your project’s purpose

Start by defining your project’s purpose. Identify what your project aims to accomplish and what you are researching. Remember to use clear language.

Thinking about the project’s purpose will help you set realistic goals and inform how you divide tasks and assign responsibilities. These individual tasks will be your stepping stones to reach your overarching goal.

Additionally, you’ll want to identify the specific problem, the usability metrics needed, and the intended solutions.

Know the following three things about your project’s purpose before you outline anything else:

What you’re doing

Why you’re doing it

What you expect from it

Identify individual objectives

With your overarching project objectives in place, you can identify any individual goals or steps needed to reach those objectives. Break them down into phases or steps. You can work backward from the project goal and identify every process required to facilitate it.

Be mindful to identify each unique task so that you can assign responsibilities to various team members. At this point in your research plan development, you’ll also want to assign priority to those smaller, more manageable steps and phases that require more immediate or dedicated attention.

Select research methods

Research methods might include any of the following:

User interviews: this is a qualitative research method where researchers engage with participants in one-on-one or group conversations. The aim is to gather insights into their experiences, preferences, and opinions to uncover patterns, trends, and data.

Field studies: this approach allows for a contextual understanding of behaviors, interactions, and processes in real-world settings. It involves the researcher immersing themselves in the field, conducting observations, interviews, or experiments to gather in-depth insights.

Card sorting: participants categorize information by sorting content cards into groups based on their perceived similarities. You might use this process to gain insights into participants’ mental models and preferences when navigating or organizing information on websites, apps, or other systems.

Focus groups: use organized discussions among select groups of participants to provide relevant views and experiences about a particular topic.

Diary studies: ask participants to record their experiences, thoughts, and activities in a diary over a specified period. This method provides a deeper understanding of user experiences, uncovers patterns, and identifies areas for improvement.

Five-second testing: participants are shown a design, such as a web page or interface, for just five seconds. They then answer questions about their initial impressions and recall, allowing you to evaluate the design’s effectiveness.

Surveys: get feedback from participant groups with structured surveys. You can use online forms, telephone interviews, or paper questionnaires to reveal trends, patterns, and correlations.

Tree testing: tree testing involves researching web assets through the lens of findability and navigability. Participants are given a textual representation of the site’s hierarchy (the “tree”) and asked to locate specific information or complete tasks by selecting paths.

Usability testing: ask participants to interact with a product, website, or application to evaluate its ease of use. This method enables you to uncover areas for improvement in digital key feature functionality by observing participants using the product.

Live website testing: research and collect analytics that outlines the design, usability, and performance efficiencies of a website in real time.

There are no limits to the number of research methods you could use within your project. Just make sure your research methods help you determine the following:

What do you plan to do with the research findings?

What decisions will this research inform? How can your stakeholders leverage the research data and results?

Recruit participants and allocate tasks

Next, identify the participants needed to complete the research and the resources required to complete the tasks. Different people will be proficient at different tasks, and having a task allocation plan will allow everything to run smoothly.

Prepare a thorough project summary

Every well-designed research plan will feature a project summary. This official summary will guide your research alongside its communications or messaging. You’ll use the summary while recruiting participants and during stakeholder meetings. It can also be useful when conducting field studies.

Ensure this summary includes all the elements of your research project. Separate the steps into an easily explainable piece of text that includes the following:

An introduction: the message you’ll deliver to participants about the interview, pre-planned questioning, and testing tasks.

Interview questions: prepare questions you intend to ask participants as part of your research study, guiding the sessions from start to finish.

An exit message: draft messaging your teams will use to conclude testing or survey sessions. These should include the next steps and express gratitude for the participant’s time.

Create a realistic timeline

While your project might already have a deadline or a results timeline in place, you’ll need to consider the time needed to execute it effectively.

Realistically outline the time needed to properly execute each supporting phase of research and implementation. And, as you evaluate the necessary schedules, be sure to include additional time for achieving each milestone in case any changes or unexpected delays arise.

For this part of your research plan, you might find it helpful to create visuals to ensure your research team and stakeholders fully understand the information.

Determine how to present your results

A research plan must also describe how you intend to present your results. Depending on the nature of your project and its goals, you might dedicate one team member (the PI) or assume responsibility for communicating the findings yourself.

In this part of the research plan, you’ll articulate how you’ll share the results. Detail any materials you’ll use, such as:

Presentations and slides

A project report booklet

A project findings pamphlet

Documents with key takeaways and statistics

Graphic visuals to support your findings

- Format your research plan

As you create your research plan, you can enjoy a little creative freedom. A plan can assume many forms, so format it how you see fit. Determine the best layout based on your specific project, intended communications, and the preferences of your teams and stakeholders.

Find format inspiration among the following layouts:

Written outlines

Narrative storytelling

Visual mapping

Graphic timelines

Remember, the research plan format you choose will be subject to change and adaptation as your research and findings unfold. However, your final format should ideally outline questions, problems, opportunities, and expectations.

- Research plan example

Imagine you’ve been tasked with finding out how to get more customers to order takeout from an online food delivery platform. The goal is to improve satisfaction and retain existing customers. You set out to discover why more people aren’t ordering and what it is they do want to order or experience.

You identify the need for a research project that helps you understand what drives customer loyalty. But before you jump in and start calling past customers, you need to develop a research plan—the roadmap that provides focus, clarity, and realistic details to the project.

Here’s an example outline of a research plan you might put together:

Project title

Project members involved in the research plan

Purpose of the project (provide a summary of the research plan’s intent)

Objective 1 (provide a short description for each objective)

Objective 2

Objective 3

Proposed timeline

Audience (detail the group you want to research, such as customers or non-customers)

Budget (how much you think it might cost to do the research)

Risk factors/contingencies (any potential risk factors that may impact the project’s success)

Remember, your research plan doesn’t have to reinvent the wheel—it just needs to fit your project’s unique needs and aims.

Customizing a research plan template

Some companies offer research plan templates to help get you started. However, it may make more sense to develop your own customized plan template. Be sure to include the core elements of a great research plan with your template layout, including the following:

Introductions to participants and stakeholders

Background problems and needs statement

Significance, ethics, and purpose

Research methods, questions, and designs

Preliminary beliefs and expectations

Implications and intended outcomes

Realistic timelines for each phase

Conclusion and presentations

How many pages should a research plan be?

Generally, a research plan can vary in length between 500 to 1,500 words. This is roughly three pages of content. More substantial projects will be 2,000 to 3,500 words, taking up four to seven pages of planning documents.

What is the difference between a research plan and a research proposal?

A research plan is a roadmap to success for research teams. A research proposal, on the other hand, is a dissertation aimed at convincing or earning the support of others. Both are relevant in creating a guide to follow to complete a project goal.

What are the seven steps to developing a research plan?

While each research project is different, it’s best to follow these seven general steps to create your research plan:

Defining the problem

Identifying goals

Choosing research methods

Recruiting participants

Preparing the brief or summary

Establishing task timelines

Defining how you will present the findings

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 12 May 2023

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 18 May 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

Illustration by James Round

How to plan a research project

Whether for a paper or a thesis, define your question, review the work of others – and leave yourself open to discovery.

by Brooke Harrington + BIO

is professor of sociology at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. Her research has won international awards both for scholarly quality and impact on public life. She has published dozens of articles and three books, most recently the bestseller Capital without Borders (2016), now translated into five languages.

Edited by Sam Haselby

Need to know

‘When curiosity turns to serious matters, it’s called research.’ – From Aphorisms (1880-1905) by Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach

Planning research projects is a time-honoured intellectual exercise: one that requires both creativity and sharp analytical skills. The purpose of this Guide is to make the process systematic and easy to understand. While there is a great deal of freedom and discovery involved – from the topics you choose, to the data and methods you apply – there are also some norms and constraints that obtain, no matter what your academic level or field of study. For those in high school through to doctoral students, and from art history to archaeology, research planning involves broadly similar steps, including: formulating a question, developing an argument or predictions based on previous research, then selecting the information needed to answer your question.

Some of this might sound self-evident but, as you’ll find, research requires a different way of approaching and using information than most of us are accustomed to in everyday life. That is why I include orienting yourself to knowledge-creation as an initial step in the process. This is a crucial and underappreciated phase in education, akin to making the transition from salaried employment to entrepreneurship: suddenly, you’re on your own, and that requires a new way of thinking about your work.

What follows is a distillation of what I’ve learned about this process over 27 years as a professional social scientist. It reflects the skills that my own professors imparted in the sociology doctoral programme at Harvard, as well as what I learned later on as a research supervisor for Ivy League PhD and MA students, and then as the author of award-winning scholarly books and articles. It can be adapted to the demands of both short projects (such as course term papers) and long ones, such as a thesis.

At its simplest, research planning involves the four distinct steps outlined below: orienting yourself to knowledge-creation; defining your research question; reviewing previous research on your question; and then choosing relevant data to formulate your own answers. Because the focus of this Guide is on planning a research project, as opposed to conducting a research project, this section won’t delve into the details of data-collection or analysis; those steps happen after you plan the project. In addition, the topic is vast: year-long doctoral courses are devoted to data and analysis. Instead, the fourth part of this section will outline some basic strategies you could use in planning a data-selection and analysis process appropriate to your research question.

Step 1: Orient yourself

Planning and conducting research requires you to make a transition, from thinking like a consumer of information to thinking like a producer of information. That sounds simple, but it’s actually a complex task. As a practical matter, this means putting aside the mindset of a student, which treats knowledge as something created by other people. As students, we are often passive receivers of knowledge: asked to do a specified set of readings, then graded on how well we reproduce what we’ve read.

Researchers, however, must take on an active role as knowledge producers . Doing research requires more of you than reading and absorbing what other people have written: you have to engage in a dialogue with it. That includes arguing with previous knowledge and perhaps trying to show that ideas we have accepted as given are actually wrong or incomplete. For example, rather than simply taking in the claims of an author you read, you’ll need to draw out the implications of those claims: if what the author is saying is true, what else does that suggest must be true? What predictions could you make based on the author’s claims?

In other words, rather than treating a reading as a source of truth – even if it comes from a revered source, such as Plato or Marie Curie – this orientation step asks you to treat the claims you read as provisional and subject to interrogation. That is one of the great pieces of wisdom that science and philosophy can teach us: that the biggest advances in human understanding have been made not by being correct about trivial things, but by being wrong in an interesting way . For example, Albert Einstein was wrong about quantum mechanics, but his arguments about it with his fellow physicist Niels Bohr have led to some of the biggest breakthroughs in science, even a century later.

Step 2: Define your research question

Students often give this step cursory attention, but experienced researchers know that formulating a good question is sometimes the most difficult part of the research planning process. That is because the precise language of the question frames the rest of the project. It’s therefore important to pose the question carefully, in a way that’s both possible to answer and likely to yield interesting results. Of course, you must choose a question that interests you, but that’s only the beginning of what’s likely to be an iterative process: most researchers come back to this step repeatedly, modifying their questions in light of previous research, resource limitations and other considerations.

Researchers face limits in terms of time and money. They, like everyone else, have to pose research questions that they can plausibly answer given the constraints they face. For example, it would be inadvisable to frame a project around the question ‘What are the roots of the Arab-Israeli conflict?’ if you have only a week to develop an answer and no background on that topic. That’s not to limit your imagination: you can come up with any question you’d like. But it typically does require some creativity to frame a question that you can answer well – that is, by investigating thoroughly and providing new insights – within the limits you face.

In addition to being interesting to you, and feasible within your resource constraints, the third and most important characteristic of a ‘good’ research topic is whether it allows you to create new knowledge. It might turn out that your question has already been asked and answered to your satisfaction: if so, you’ll find out in the next step of this process. On the other hand, you might come up with a research question that hasn’t been addressed previously. Before you get too excited about breaking uncharted ground, consider this: a lot of potentially researchable questions haven’t been studied for good reason ; they might have answers that are trivial or of very limited interest. This could include questions such as ‘Why does the area of a circle equal π r²?’ or ‘Did winter conditions affect Napoleon’s plans to invade Russia?’ Of course, you might be able to make the argument that a seemingly trivial question is actually vitally important, but you must be prepared to back that up with convincing evidence. The exercise in the ‘Learn More’ section below will help you think through some of these issues.

Finally, scholarly research questions must in some way lead to new and distinctive insights. For example, lots of people have studied gender roles in sports teams; what can you ask that hasn’t been asked before? Reinventing the wheel is the number-one no-no in this endeavour. That’s why the next step is so important: reviewing previous research on your topic. Depending on what you find in that step, you might need to revise your research question; iterating between your question and the existing literature is a normal process. But don’t worry: it doesn’t go on forever. In fact, the iterations taper off – and your research question stabilises – as you develop a firm grasp of the current state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 3: Review previous research

In academic research, from articles to books, it’s common to find a section called a ‘literature review’. The purpose of that section is to describe the state of the art in knowledge on the research question that a project has posed. It demonstrates that researchers have thoroughly and systematically reviewed the relevant findings of previous studies on their topic, and that they have something novel to contribute.

Your own research project should include something like this, even if it’s a high-school term paper. In the research planning process, you’ll want to list at least half a dozen bullet points stating the major findings on your topic by other people. In relation to those findings, you should be able to specify where your project could provide new and necessary insights. There are two basic rhetorical positions one can take in framing the novelty-plus-importance argument required of academic research:

- Position 1 requires you to build on or extend a set of existing ideas; that means saying something like: ‘Person A has argued that X is true about gender; this implies Y, which has not yet been tested. My project will test Y, and if I find evidence to support it, that will change the way we understand gender.’

- Position 2 is to argue that there is a gap in existing knowledge, either because previous research has reached conflicting conclusions or has failed to consider something important. For example, one could say that research on middle schoolers and gender has been limited by being conducted primarily in coeducational environments, and that findings might differ dramatically if research were conducted in more schools where the student body was all-male or all-female.

Your overall goal in this step of the process is to show that your research will be part of a larger conversation: that is, how your project flows from what’s already known, and how it advances, extends or challenges that existing body of knowledge. That will be the contribution of your project, and it constitutes the motivation for your research.

Two things are worth mentioning about your search for sources of relevant previous research. First, you needn’t look only at studies on your precise topic. For example, if you want to study gender-identity formation in schools, you shouldn’t restrict yourself to studies of schools; the empirical setting (schools) is secondary to the larger social process that interests you (how people form gender identity). That process occurs in many different settings, so cast a wide net. Second, be sure to use legitimate sources – meaning publications that have been through some sort of vetting process, whether that involves peer review (as with academic journal articles you might find via Google Scholar) or editorial review (as you’d find in well-known mass media publications, such as The Economist or The Washington Post ). What you’ll want to avoid is using unvetted sources such as personal blogs or Wikipedia. Why? Because anybody can write anything in those forums, and there is no way to know – unless you’re already an expert – if the claims you find there are accurate. Often, they’re not.

Step 4: Choose your data and methods

Whatever your research question is, eventually you’ll need to consider which data source and analytical strategy are most likely to provide the answers you’re seeking. One starting point is to consider whether your question would be best addressed by qualitative data (such as interviews, observations or historical records), quantitative data (such as surveys or census records) or some combination of both. Your ideas about data sources will, in turn, suggest options for analytical methods.

You might need to collect your own data, or you might find everything you need readily available in an existing dataset someone else has created. A great place to start is with a research librarian: university libraries always have them and, at public universities, those librarians can work with the public, including people who aren’t affiliated with the university. If you don’t happen to have a public university and its library close at hand, an ordinary public library can still be a good place to start: the librarians are often well versed in accessing data sources that might be relevant to your study, such as the census, or historical archives, or the Survey of Consumer Finances.

Because your task at this point is to plan research, rather than conduct it, the purpose of this step is not to commit you irrevocably to a course of action. Instead, your goal here is to think through a feasible approach to answering your research question. You’ll need to find out, for example, whether the data you want exist; if not, do you have a realistic chance of gathering the data yourself, or would it be better to modify your research question? In terms of analysis, would your strategy require you to apply statistical methods? If so, do you have those skills? If not, do you have time to learn them, or money to hire a research assistant to run the analysis for you?

Please be aware that qualitative methods in particular are not the casual undertaking they might appear to be. Many people make the mistake of thinking that only quantitative data and methods are scientific and systematic, while qualitative methods are just a fancy way of saying: ‘I talked to some people, read some old newspapers, and drew my own conclusions.’ Nothing could be further from the truth. In the final section of this guide, you’ll find some links to resources that will provide more insight on standards and procedures governing qualitative research, but suffice it to say: there are rules about what constitutes legitimate evidence and valid analytical procedure for qualitative data, just as there are for quantitative data.

Circle back and consider revising your initial plans

As you work through these four steps in planning your project, it’s perfectly normal to circle back and revise. Research planning is rarely a linear process. It’s also common for new and unexpected avenues to suggest themselves. As the sociologist Thorstein Veblen wrote in 1908 : ‘The outcome of any serious research can only be to make two questions grow where only one grew before.’ That’s as true of research planning as it is of a completed project. Try to enjoy the horizons that open up for you in this process, rather than becoming overwhelmed; the four steps, along with the two exercises that follow, will help you focus your plan and make it manageable.

Key points – How to plan a research project

- Planning a research project is essential no matter your academic level or field of study. There is no one ‘best’ way to design research, but there are certain guidelines that can be helpfully applied across disciplines.

- Orient yourself to knowledge-creation. Make the shift from being a consumer of information to being a producer of information.

- Define your research question. Your question frames the rest of your project, sets the scope, and determines the kinds of answers you can find.

- Review previous research on your question. Survey the existing body of relevant knowledge to ensure that your research will be part of a larger conversation.

- Choose your data and methods. For instance, will you be collecting qualitative data, via interviews, or numerical data, via surveys?

- Circle back and consider revising your initial plans. Expect your research question in particular to undergo multiple rounds of refinement as you learn more about your topic.

Good research questions tend to beget more questions. This can be frustrating for those who want to get down to business right away. Try to make room for the unexpected: this is usually how knowledge advances. Many of the most significant discoveries in human history have been made by people who were looking for something else entirely. There are ways to structure your research planning process without over-constraining yourself; the two exercises below are a start, and you can find further methods in the Links and Books section.

The following exercise provides a structured process for advancing your research project planning. After completing it, you’ll be able to do the following:

- describe clearly and concisely the question you’ve chosen to study

- summarise the state of the art in knowledge about the question, and where your project could contribute new insight

- identify the best strategy for gathering and analysing relevant data

In other words, the following provides a systematic means to establish the building blocks of your research project.

Exercise 1: Definition of research question and sources

This exercise prompts you to select and clarify your general interest area, develop a research question, and investigate sources of information. The annotated bibliography will also help you refine your research question so that you can begin the second assignment, a description of the phenomenon you wish to study.

Jot down a few bullet points in response to these two questions, with the understanding that you’ll probably go back and modify your answers as you begin reading other studies relevant to your topic:

- What will be the general topic of your paper?

- What will be the specific topic of your paper?

b) Research question(s)

Use the following guidelines to frame a research question – or questions – that will drive your analysis. As with Part 1 above, you’ll probably find it necessary to change or refine your research question(s) as you complete future assignments.

- Your question should be phrased so that it can’t be answered with a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

- Your question should have more than one plausible answer.

- Your question should draw relationships between two or more concepts; framing the question in terms of How? or What? often works better than asking Why ?

c) Annotated bibliography

Most or all of your background information should come from two sources: scholarly books and journals, or reputable mass media sources. You might be able to access journal articles electronically through your library, using search engines such as JSTOR and Google Scholar. This can save you a great deal of time compared with going to the library in person to search periodicals. General news sources, such as those accessible through LexisNexis, are acceptable, but should be cited sparingly, since they don’t carry the same level of credibility as scholarly sources. As discussed above, unvetted sources such as blogs and Wikipedia should be avoided, because the quality of the information they provide is unreliable and often misleading.

To create an annotated bibliography, provide the following information for at least 10 sources relevant to your specific topic, using the format suggested below.

Name of author(s):

Publication date:

Title of book, chapter, or article:

If a chapter or article, title of journal or book where they appear:

Brief description of this work, including main findings and methods ( c 75 words):

Summary of how this work contributes to your project ( c 75 words):

Brief description of the implications of this work ( c 25 words):

Identify any gap or controversy in knowledge this work points up, and how your project could address those problems ( c 50 words):

Exercise 2: Towards an analysis

Develop a short statement ( c 250 words) about the kind of data that would be useful to address your research question, and how you’d analyse it. Some questions to consider in writing this statement include:

- What are the central concepts or variables in your project? Offer a brief definition of each.

- Do any data sources exist on those concepts or variables, or would you need to collect data?

- Of the analytical strategies you could apply to that data, which would be the most appropriate to answer your question? Which would be the most feasible for you? Consider at least two methods, noting their advantages or disadvantages for your project.

Links & books

One of the best texts ever written about planning and executing research comes from a source that might be unexpected: a 60-year-old work on urban planning by a self-trained scholar. The classic book The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961) by Jane Jacobs (available complete and free of charge via this link ) is worth reading in its entirety just for the pleasure of it. But the final 20 pages – a concluding chapter titled ‘The Kind of Problem a City Is’ – are really about the process of thinking through and investigating a problem. Highly recommended as a window into the craft of research.