Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Women rarely die from heart problems, right? Ask Paula.

When will patients see personalized cancer vaccines?

A molecular ‘warhead’ against disease

“When my son was diagnosed [with Type 1], I knew nothing about diabetes. I changed my research focus, thinking, as any parent would, ‘What am I going to do about this?’” says Douglas Melton.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Breakthrough within reach for diabetes scientist and patients nearest to his heart

Harvard Correspondent

100 years after discovery of insulin, replacement therapy represents ‘a new kind of medicine,’ says Stem Cell Institute co-director Douglas Melton, whose children inspired his research

When Vertex Pharmaceuticals announced last month that its investigational stem-cell-derived replacement therapy was, in conjunction with immunosuppressive therapy, helping the first patient in a Phase 1/2 clinical trial robustly reproduce his or her own fully differentiated pancreatic islet cells, the cells that produce insulin, the news was hailed as a potential breakthrough for the treatment of Type 1 diabetes. For Harvard Stem Cell Institute Co-Director and Xander University Professor Douglas Melton, whose lab pioneered the science behind the therapy, the trial marked the most recent turning point in a decades-long effort to understand and treat the disease. In a conversation with the Gazette, Melton discussed the science behind the advance, the challenges ahead, and the personal side of his research. The interview was edited for clarity and length.

Douglas Melton

GAZETTE: What is the significance of the Vertex trial?

MELTON: The first major change in the treatment of Type 1 diabetes was probably the discovery of insulin in 1920. Now it’s 100 years later and if this works, it’s going to change the medical treatment for people with diabetes. Instead of injecting insulin, patients will get cells that will be their own insulin factories. It’s a new kind of medicine.

GAZETTE: Would you walk us through the approach?

MELTON: Nearly two decades ago we had the idea that we could use embryonic stem cells to make functional pancreatic islets for diabetics. When we first started, we had to try to figure out how the islets in a person’s pancreas replenished. Blood, for example, is replenished routinely by a blood stem cell. So, if you go give blood at a blood drive, your body makes more blood. But we showed in mice that that is not true for the pancreatic islets. Once they’re removed or killed, the adult body has no capacity to make new ones.

So the first important “a-ha” moment was to demonstrate that there was no capacity in an adult to make new islets. That moved us to another source of new material: stem cells. The next important thing, after we overcame the political issues surrounding the use of embryonic stem cells, was to ask: Can we direct the differentiation of stem cells and make them become beta cells? That problem took much longer than I expected — I told my wife it would take five years, but it took closer to 15. The project benefited enormously from undergraduates, graduate students, and postdocs. None of them were here for 15 years of course, but they all worked on different steps.

GAZETTE: What role did the Harvard Stem Cell Institute play?

MELTON: This work absolutely could not have been done using conventional support from the National Institutes of Health. First of all, NIH grants came with severe restrictions and secondly, a long-term project like this doesn’t easily map to the initial grant support they give for a one- to three-year project. I am forever grateful and feel fortunate to have been at a private institution where philanthropy, through the HSCI, wasn’t just helpful, it made all the difference.

I am exceptionally grateful as well to former Harvard President Larry Summers and Steve Hyman, director of the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research at the Broad Institute, who supported the creation of the HSCI, which was formed specifically with the idea to explore the potential of pluripotency stem cells for discovering questions about how development works, how cells are made in our body, and hopefully for finding new treatments or cures for disease. This may be one of the first examples where it’s come to fruition. At the time, the use of embryonic stem cells was quite controversial, and Steve and Larry said that this was precisely the kind of science they wanted to support.

GAZETTE: You were fundamental in starting the Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology. Can you tell us about that?

MELTON: David Scadden and I helped start the department, which lives in two Schools: Harvard Medical School and the Faculty of Arts and Science. This speaks to the unusual formation and intention of the department. I’ve talked a lot about diabetes and islets, but think about all the other tissues and diseases that people suffer from. There are faculty and students in the department working on the heart, nerves, muscle, brain, and other tissues — on all aspects of how the development of a cell and a tissue affects who we are and the course of disease. The department is an exciting one because it’s exploring experimental questions such as: How do you regenerate a limb? The department was founded with the idea that not only should you ask and answer questions about nature, but that one can do so with the intention that the results lead to new treatments for disease. It is a kind of applied biology department.

GAZETTE: This pancreatic islet work was patented by Harvard and then licensed to your biotech company, Semma, which was acquired by Vertex. Can you explain how this reflects your personal connection to the research?

MELTON: Semma is named for my two children, Sam and Emma. Both are now adults, and both have Type 1 diabetes. My son was 6 months old when he was diagnosed. And that’s when I changed my research plan. And my daughter, who’s four years older than my son, became diabetic about 10 years later, when she was 14.

When my son was diagnosed, I knew nothing about diabetes and had been working on how frogs develop. I changed my research focus, thinking, as any parent would, “What am I going to do about this?” Again, I come back to the flexibility of Harvard. Nobody said, “Why are you changing your research plan?”

GAZETTE: What’s next?

MELTON: The stem-cell-derived replacement therapy cells that have been put into this first patient were provided with a class of drugs called immunosuppressants, which depress the patient’s immune system. They have to do this because these cells were not taken from that patient, and so they are not recognized as “self.” Without immunosuppressants, they would be rejected. We want to find a way to make cells by genetic engineering that are not recognized as foreign.

I think this is a solvable problem. Why? When a woman has a baby, that baby has two sets of genes. It has genes from the egg, from the mother, which would be recognized as “self,” but it also has genes from the father, which would be “non-self.” Why does the mother’s body not reject the fetus? If we can figure that out, it will help inform our thinking about what genes to change in our stem cell-derived islets so that they could go into any person. This would be relevant not just to diabetes, but to any cells you wanted to transplant for liver or even heart transplants. It could mean no longer having to worry about immunosuppression.

Share this article

You might like.

New book traces how medical establishment’s sexism, focus on men over centuries continues to endanger women’s health, lives

Sooner than you may think, says researcher who recently won Sjöberg Prize for pioneering work in field

Approach attacks errant proteins at their roots

Harvard announces return to required testing

Leading researchers cite strong evidence that testing expands opportunity

Yes, it’s exciting. Just don’t look at the sun.

Lab, telescope specialist details Harvard eclipse-viewing party, offers safety tips

For all the other Willie Jacks

‘Reservation Dogs’ star Paulina Alexis offers behind-the-scenes glimpse of hit show, details value of Native representation

- April 11, 2024 | Double Trouble: Decoding the Pain-Depression Feedback Loop

- April 11, 2024 | Elemental Surprise: Physicists Discover a New Quantum State

- April 11, 2024 | A Real Life Eye of Sauron? New Technology To Detect Airborne Threats Instantly

- April 11, 2024 | This Math Problem Stumped Scientists for Almost a Century – Two Mathematicians Have Finally Solved It

- April 11, 2024 | Galactic Genesis Unveiled: JWST Witnesses the Dawn of Starlight

Beyond Blood Sugar Control: New Target for Curing Diabetes Unveiled

By Helmholtz Munich March 22, 2024

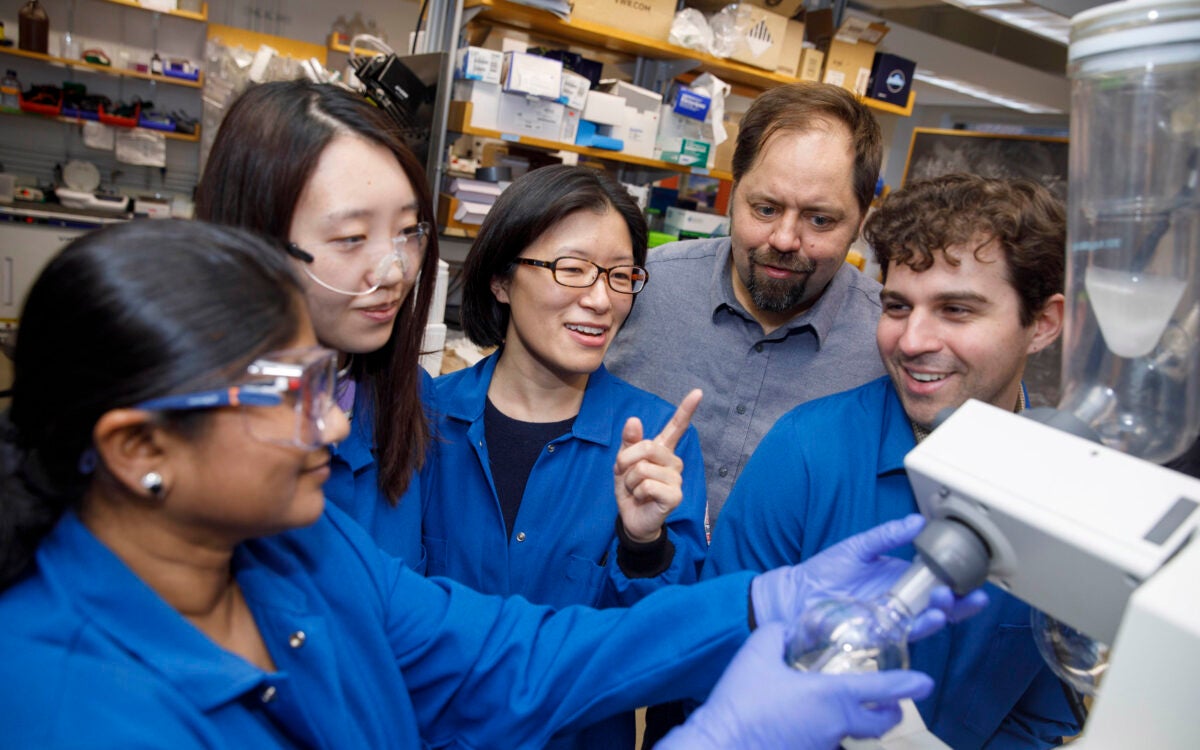

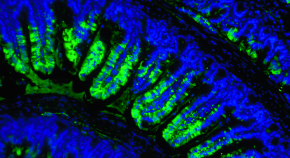

Targeting the inceptor receptor could lead to breakthrough treatments for diabetes by protecting beta cells and improving blood sugar control, with German research institutions leading this promising discovery. Insulin-producing beta cells in the islet of Langerhans. Credit: Helmholtz Munich | Erik Bader

Research focusing on the insulin -inhibitory receptor, known as inceptor, has revealed promising paths for protecting beta cells, providing optimism for therapy that directly addresses diabetes. A groundbreaking study involving mice with obesity caused by diet shows that eliminating inceptor improves glucose management. This finding encourages further investigation into inceptor as a potential therapeutic target for treating type 2 diabetes.

These findings, led by Helmholtz Munich in collaboration with the German Center for Diabetes Research, the Technical University of Munich, and the Ludwig-Maximilians-University Munich, drive advancements in diabetes research.

Targeting Inceptor to Combat Insulin Resistance in Beta Cells

Insulin resistance, often linked to abdominal obesity, presents a significant healthcare dilemma in our era. More importantly, the insulin resistance of beta cells contributes to their dysfunction and the transition from obesity to overt type 2 diabetes. Currently, all pharmacotherapies, including insulin supplementation, focus on managing high blood sugar levels rather than addressing the underlying cause of diabetes: beta cell failure or loss. Therefore, research into beta cell protection and regeneration is crucial and holds promising prospects for addressing the root cause of diabetes, offering potential avenues for causal treatment.

With the recent discovery of inceptor, the research group of beta cell expert Prof. Heiko Lickert has uncovered an interesting molecular target. Upregulated in diabetes, the insulin-inhibitory receptor inceptor may contribute to insulin resistance by acting as a negative regulator of this signaling pathway. Conversely, inhibiting the function of the inceptor could enhance insulin signaling – which in turn is required for overall beta cell function, survival, and compensation upon stress.

In collaboration with Prof. Timo Müller, an expert in molecular pharmacology in obesity and diabetes, the researchers explored the effects of inceptor knock-out in diet-induced obese mice. Their study aimed to determine whether inhibiting inceptor function could also enhance glucose tolerance in diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance, both critical pre-clinical stages in the progression toward diabetes. The results were now published in Nature Metabolism .

Removing Inceptor Improves Blood Sugar Levels in Obese Mice

The researchers delved into the effects of removing inceptor from all body cells in diet-induced obese mice. Interestingly, they found that mice lacking inceptor exhibited improved glucose regulation without experiencing weight loss, which was linked to increased insulin secretion in response to glucose. Next, they investigated the distribution of inceptor in the central nervous system and discovered its widespread presence in neurons. Deleting inceptor from neuronal cells also improved glucose regulation in obese mice. Ultimately, the researchers selectively removed the inceptor from the mice’s beta cells, resulting in enhanced glucose control and a slight increase in beta cell mass.

Research for Inceptor-Blocking Drugs

“Our findings support the idea that enhancing insulin sensitivity through targeting inceptor shows promise as a pharmacological intervention, especially concerning the health and function of beta cells,” says Timo Müller. Unlike intensive early-onset insulin treatments, utilizing inceptor to enhance beta cell function offers promise in alleviating the detrimental effects on blood sugar and metabolism induced by diet-induced obesity. This approach avoids the associated risks of hypoglycemia-associated unawareness and unwanted weight gain typically observed with intensive insulin therapy.

“Since inceptor is expressed on the surface of pancreatic beta cells, it becomes an accessible drug target. Currently, our laboratory is actively researching the potential of several inceptor-blocking drug classes to enhance beta cell health in pre-diabetic and diabetic mice. Looking forward, inceptor emerges as a novel and intriguing molecular target for enhancing beta cell health, not only in prediabetic obese individuals but also in patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes,” explains Heiko Lickert.

Reference: “Global, neuronal or β cell-specific deletion of inceptor improves glucose homeostasis in male mice with diet-induced obesity” by Gerald Grandl, Gustav Collden, Jin Feng, Sreya Bhattacharya, Felix Klingelhuber, Leopold Schomann, Sara Bilekova, Ansarullah, Weiwei Xu, Fataneh Fathi Far, Monica Tost, Tim Gruber, Aimée Bastidas-Ponce, Qian Zhang, Aaron Novikoff, Arkadiusz Liskiewicz, Daniela Liskiewicz, Cristina Garcia-Caceres, Annette Feuchtinger, Matthias H. Tschöp, Natalie Krahmer, Heiko Lickert and Timo D. Müller, 28 February 2024, Nature Metabolism . DOI: 10.1038/s42255-024-00991-3

More on SciTechDaily

Quantum Breakthrough Reveals Superconductor’s Hidden Nature

Novel Molecules Discovered to Combat Asthma and COVID-Related Lung Diseases

Orbital Engineering, Yale Engineers Change Electron Trajectories

Finding and Erasing Quantum Computing Errors in Real-Time

“Glow-in-the-Dark” Proteins: The Future of Viral Disease Detection?

A black hole – a million times as bright as our sun – offers potential clue to reionization of universe.

Risk Factors for Falls in Older Americans Identified – A Growing Public Health Concern

Common Fireworks Emit Toxic Metals Into the Air – Damage Human Cells and Animal Lungs

1 comment on "beyond blood sugar control: new target for curing diabetes unveiled".

Interesting study and hopefully another tool which will apply to diabetic patients.

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Email address is optional. If provided, your email will not be published or shared.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Experimental Treatments for Type 2 Diabetes

- Drug Treatments

- Diet and Nutrition

Artificial Pancreas

Pancreas transplant, frequently asked questions.

Lifestyle changes such as eating a diabetes-friendly diet , exercising more, and maintaining a healthy body weight combined with existing treatment options are the best way to prevent or manage type 2 diabetes .

However, for people with type 2 diabetes who have trouble controlling their blood sugar by making healthier lifestyle choices or taking medications, experimental treatments could help.

This article provides an overview of type 2 diabetes experimental treatments and explains how the latest type 2 diabetes research has led to new Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved pharmacological treatments and devices like the "artificial pancreas."

Read on to learn more about other experimental treatments for type 2 diabetes that show promise but haven't been approved by the FDA yet.

fotograzia / Getty Images

Pharmacological Treatments

Only about half of all U.S. adults with type 2 diabetes achieve good blood sugar level targets based on the A1c test , a simple blood test measuring blood sugar levels averaged over the past three months.

Fortunately, advances in type 2 diabetes research have led to some groundbreaking experimental treatments and drug combinations that show promise in preliminary studies.

Mounjaro (Tirzepatide)

The latest pharmacological treatment approved by the FDA for type 2 diabetes combines glucagon-like peptide-1 ( GLP-1 ) agonists and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptides (GIP).

In May 2022, the FDA approved the novel type 2 diabetes injectable medication called Mounjaro (tirzepatide). Mounjaro is the first and only FDA-approved dual GIP and GLP-1 agonist medication for type 2 diabetes.

Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, also known as a glifozins , are another state-of-the-art class of drugs approved by the FDA to lower blood sugar in adults with type 2 diabetes. SGLT2 inhibitors are prescribed along with lifestyle changes like diet and exercise. Glifozins are not FDA-approved for patients with type 1 diabetes.

Accumulating evidence suggests that SGLT2 inhibitors have other health benefits such as promoting weight loss and improving cardiac functions. A meta-analysis (a formal assessment of previous research) of 10 clinical trials found that the use of SGLT2 inhibitors was associated with a 33% lower risk of life-threatening cardiovascular disease.

Wegovy (Semaglutide)

In June 2021, the FDA approved Wegovy, a weight-loss prescription drug, for people diagnosed with obesity and a weight-related condition such as high blood pressure or high cholesterol . In September 2022, researchers announced that weekly injections of this drug may reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes risk by 61%.

Tesaglitazar

Tesaglitazar is an experimental drug that showed promise as a treatment for type 2 diabetes in early studies. However, its development was put on hold by AstraZeneca in May 2006 before all of the phase 3 trials were completed. But this experimental treatment might be making a comeback.

In August 2022, a study in mice showed that combining tesaglitazar with GLP-1 agonists reduced the drug's adverse effects while increasing its positive effects on sugar metabolism. Still, human studies are needed.

Special Dietary and Nutritional Treatments

Eating a diet to help type 2 diabetes is one of the most effective ways for people with type 2 diabetes to control blood sugar. If you have diabetes, it's important to educate yourself about different types of carbohydrates and to monitor your blood sugar levels using a glucometer .

Research on supplements for type 2 diabetes has had mixed results. After years of research, a study of 2,423 people concluded that vitamin D supplements don't prevent type 2 diabetes and may not have long-term benefits. That said, a 2019 meta-analysis of other peer-reviewed studies concluded that vitamin D supplements may help people with type 2 diabetes control their blood sugar levels in the short term.

Over-the-counter (OTC) nutritional supplements that lower blood sugar can carry potential risks and are not intended to replace diabetes medications . Always use common sense and speak with a healthcare provider before making dietary changes or using nutritional supplements.

The "artificial pancreas" is a portable external device that controls blood glucose levels using a closed-loop insulin pump system. A 2021 study found that closed-loop artificial pancreas therapy helped people with type 2 diabetes safely manage their blood sugar levels and reduced the risk of severe hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) events.

Bariatric Surgery for Type 2 Diabetes

Bariatric weight-loss surgery is an effective treatment for many people with type 2 diabetes. Among bariatric procedures, a 2019 randomized trial found that gastric bypass surgery (creating and attaching a small pouch directly to the small intestine, bypassing the stomach) is superior to gastric sleeve surgery (removing a portion of the stomach) for remission of type 2 diabetes.

Although a pancreas transplant can benefit people with type 1 diabetes by restoring insulin production and improving blood sugar control, it's an extreme measure and isn't typically a treatment option for those with type 2 diabetes.

However, in certain patients with type 2 diabetes who have both a low production of insulin (hormone created by your pancreas that controls the sugar in your bloodstream) and insulin resistance (when cells stop responding to the insulin you make), a pancreas transplant may be considered.

However, the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) eligibility criteria strictly limit access to pancreas transplantation in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Islet Transplant Surgery for Diabetics

Islet cell transplantation is a treatment option for some patients with type 1 diabetes but isn't currently an FDA-approved option for those with type 2 diabetes.

Diabetes research has led to some groundbreaking new treatment options. In May 2022, the FDA approved a potentially game-changing new drug called Mounjaro (tirzepatide) that targets both GLP-1 and GIP. In September 2022, researchers announced that another experimental drug, tesaglitazar, which didn't initially succeed in clinical trials, shows renewed promise when combined with a GLP-1 antagonist.

Other new treatments, like SGLT2 inhibitors, are effective for type 2 diabetes when combined with lifestyle changes related to diet and exercise. For people who have trouble losing weight, bariatric surgery and weight-loss drugs like Wegovy (semaglutide) can help people maintain a healthy weight and lower their risk of type 2 diabetes.

Experimental treatments for type 2 diabetes carry risks. Always speak to a healthcare provider before making changes to your diet or taking nutritional supplements.

No. There is no cure for type 2 diabetes. Losing weight, eating healthier, and exercising more can help to prevent and manage this type 2 diabetes. If diet, exercise, and weight loss fail to control blood sugar, antidiabetic medications or insulin therapy can help achieve glycemic targets.

If you have diabetes and want to take something other than metformin , speak to a healthcare provider about your options. Some alternatives to metformin that people with type 2 diabetes can use to control high blood sugar include, Farxiga (dapagliflozin), Invokana (canagliflozin), Jardiance (empagliflozin), and Nesina (alogliptin).

There's little to no evidence-based research showing that specific vitamins are helpful to people with diabetes in the long term. Vitamin D may help people with diabetes in the short term, but a yearslong National Institutes of Health–funded trial ultimately found that vitamin D supplements do not prevent type 2 diabetes.

ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 5. Facilitating positive health behaviors and well-being to improve health outcomes: Standards of care in diabetes—2023 . Diabetes Care . 2023;46(Suppl 1):S68-S96. doi:10.2337/dc23-S005

Carls G, Huynh J, Tuttle E, Yee J, Edelman SV. Achievement of glycated hemoglobin goals in the us remains unchanged through 2014. Diabetes Ther . 2017;8(4):863-873. doi:10.1007/s13300-017-0280-5

ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 9. Pharmacologic approaches to glycemic treatment: Standards of care in diabetes—2023 . Diabetes Care . 2023;46(Suppl 1):S140-S157. doi:10.2337/dc23-S009

Gasbjerg LS, Gabe MBN, Hartmann B, et al. Glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) receptor antagonists as anti-diabetic agents. Peptides . 2018;100:173-181. doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2017.11.021

Food and Drug Administration. MOUNJAROTM (tirzepatide) injection, for subcutaneous use [drug label].

FDA. Sodium-glucose Cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) Inhibitors.

Pharmacy Practice News. Evidence mounts for benefits of SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 RAs .

Bhattarai M, Salih M, Regmi M, et al. Association of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors with cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and other risk factors for cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open . 2022;5(1):e2142078. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.42078

FDA. FDA Approves New Drug Treatment for Chronic Weight Management, First Since 2014.

UAB News. Who will benefit from new ‘game-changing’ weight-loss drug semaglutide?

Hellmold H, Zhang H, Andersson U, et al. Tesaglitazar, a pparα/γ agonist, induces interstitial mesenchymal cell dna synthesis and fibrosarcomas in subcutaneous tissues in rats . Toxicological Sciences . 2007;98(1):63-74. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfm094

Quarta C, Stemmer K, Novikoff A, et al. GLP-1-mediated delivery of tesaglitazar improves obesity and glucose metabolism in male mice . Nat Metab . 2022;4(8):1071-1083. doi:10.1038/s42255-022-00617-6

Tufts Medical Center. D2d (Vitamin D and Type 2 Diabetes) results .

Hu Z, Chen J, Sun X, Wang L, Wang A. Efficacy of vitamin D supplementation on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes patients: A meta-analysis of interventional studies . Medicine . 2019;98(14):e14970. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000014970

Zhou K, Isaacs D. Closed-loop artificial pancreas therapy for type 1 diabetes . Curr Cardiol Rep . 2022;24(9):1159-1167. doi:10.1007/s11886-022-01733-1

Boughton CK, Tripyla A, Hartnell S, et al. Fully automated closed-loop glucose control compared with standard insulin therapy in adults with type 2 diabetes requiring dialysis: An open-label, randomized crossover trial . Nat Med . 2021;27(8):1471-1476. doi:0.1038/s41591-021-01453-z

ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, et al. 8. Obesity and weight management for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes: Standards of care in diabetes—2023 . Diabetes Care . 2023;46(Suppl 1):S128-S139. doi:10.2337/dc23-S008

Hofsø D, Fatima F, Borgeraas H, et al. Gastric bypass versus sleeve gastrectomy in patients with type 2 diabetes (Oseberg): A single-centre, triple-blind, randomised controlled trial . The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology . 2019;7(12):912-924. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30344-4

Kandaswamy R, Stock PG, Gustafson SK, et al. Optn/srtr 2016 annual data report: Pancreas . Am J Transplant . 2018;18:114-171. doi:10.1111/ajt.14558

Bleskestad KB, Nordheim E, Lindahl JP, et al. Insulin secretion and action after pancreas transplantation. A retrospective single-center study . Scandinavian Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Investigation . 2021;81(5):365-370. doi:10.1080/00365513.2021.1926535

Stratta RJ, Farney AC, Fridell JA. Analyzing outcomes following pancreas transplantation: Definition of a failure or failure of a definition . American J Transplantation . 2022;22(6):1523-1526. doi:10.1111/ajt.17003

Pullen LC. Islet cell transplantation hits a milestone . Am J Transplant . 2021;21(8):2625-2626. doi:10.1111/ajt.16039

diaTribe Learn. What are my choices for metformin alternatives?

NIH. NIH-funded trial finds vitamin D does not prevent type 2 diabetes in people at high risk .

By Christopher Bergland Christopher Bergland is a retired ultra-endurance athlete turned medical writer and science reporter.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Pharmacological Reviews

New Aspects of Diabetes Research and Therapeutic Development

Both type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus are advancing at exponential rates, placing significant burdens on health care networks worldwide. Although traditional pharmacologic therapies such as insulin and oral antidiabetic stalwarts like metformin and the sulfonylureas continue to be used, newer drugs are now on the market targeting novel blood glucose–lowering pathways. Furthermore, exciting new developments in the understanding of beta cell and islet biology are driving the potential for treatments targeting incretin action, islet transplantation with new methods for immunologic protection, and the generation of functional beta cells from stem cells. Here we discuss the mechanistic details underlying past, present, and future diabetes therapies and evaluate their potential to treat and possibly reverse type 1 and 2 diabetes in humans.

Significance Statement

Diabetes mellitus has reached epidemic proportions in the developed and developing world alike. As the last several years have seen many new developments in the field, a new and up to date review of these advances and their careful evaluation will help both clinical and research diabetologists to better understand where the field is currently heading.

I. Introduction

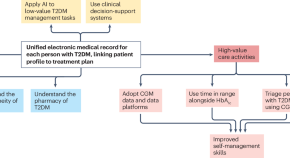

Diabetes mellitus, a metabolic disease defined by elevated fasting blood glucose levels due to insufficient insulin production, has reached epidemic proportions worldwide (World Health Organization, 2020 ). Type 1 and type 2 diabetes (T1D and T2D, respectively) make up the majority of diabetes cases with T1D characterized by autoimmune destruction of the insulin-producing pancreatic beta cells. The much more prevalent T2D arises in conjunction with peripheral tissue insulin resistance and beta cell failure and is estimated to increase to 21%–33% of the US population by the year 2050 (Boyle et al., 2010 ). To combat this growing health threat and its cardiac, renal, and neurologic comorbidities, new and more effective diabetes drugs and treatments are essential. As the last several years have seen many new developments in the field of diabetes pharmacology and therapy, we determined that a new and up to date review of these advances was in order. Our aim is to provide a careful evaluation of both old and new therapies ( Fig. 1 ) in a manner that we hope will be of interest to both clinical and bench diabetologists. Instead of the usual encyclopedic approach to this topic, we provide here a targeted and selective consideration of the underlying issues, promising new treatments, and a re-examination of more traditional approaches. Thus, we do not discuss less frequently used diabetes agents, such as alpha-glucosidase inhibitors; these were discussed in other recent reviews (Hedrington and Davis, 2019 ; Lebovitz, 2019 ).

Pharmacologic targeting of numerous organ systems for the treatment of diabetes. Treatment of diabetes involves targeting of various organ systems, including the kidney by SGLT2 inhibitors; the liver, gut, and adipose tissue by metformin; and direct actions upon the pancreatic beta cell. Beta cell compounds aim to increase secretion or mass and/or to protect from autoimmunity destruction. Ultimately, insulin therapy remains the final line of diabetes treatment with new technologies under development to more tightly regulate blood glucose levels similar to healthy beta cells. hESC, human embryonic stem cell.

II. Diabetes Therapies

A. metformin.

Metformin is a biguanide originally based on the natural product galegine, which was extracted from the French lilac (Bailey, 1992 ; Rojas and Gomes, 2013 ; Witters, 2001 ). A closely related biguanide, phenformin, was also used initially for its hypoglycemic actions. Based on its successful track record as a safe, effective, and inexpensive oral medication, metformin has become the most widely prescribed oral agent in the world in treating T2D (Rojas and Gomes, 2013 ; He and Wondisford, 2015 ; Witters, 2001 ), whereas phenformin has been largely bypassed due to its unacceptably high association with lactic acidosis (Misbin, 2004 ). Unlike sulfonylureas, metformin lowers blood glucose without provoking hypoglycemia and improves insulin sensitivity (Bailey, 1992 ). Despite these well known beneficial metabolic actions, metformin’s mechanism of action and even its main target organ remain controversial. In fact, metformin has multiple mechanisms of action at the organ as well as the cellular level, which has hindered our understanding of its most important molecular effects on glucose metabolism (Witters, 2001 ). Adding to this, a specific receptor for metformin has never been identified. Metformin has actions on several tissues, although the primary foci of most studies have been the liver, skeletal muscle, and the intestine (Foretz et al., 2014 ; Rena et al., 2017 ). Metformin and phenformin clearly suppress hepatic glucose production and gluconeogenesis, and they improve insulin sensitivity in the liver and elsewhere (Bailey, 1992 ). The hepatic actions of metformin have been the most exhaustively studied to date, and there is little doubt that these actions are of some importance. However, several of the studies remain highly controversial, and there are still open questions.

One of the first reported specific molecular targets of metformin was mitochondrial complex I of the electron transport chain. Inhibition of this complex results in reduced oxidative phosphorylation and consequently decreased hepatic ATP production (El-Mir et al., 2008 ; Evans et al., 2005 ; Owen et al., 2000 ). As is the case in many other studies of metformin, however, high concentrations of the drug were found to be necessary to depress metabolism at this site (El-Mir et al., 2000 ; He and Wondisford, 2015 ; Owen et al., 2000 ). Also controversial is whether metformin works by activating 5′ AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a molecular energy sensor that is known to be a major metabolic sensor in cells, or if not AMPK directly, then one of its upstream regulators such as liver kinase B2 (Zhou et al., 2001 ). Although metformin was shown to activate AMPK in several excellent studies, other studies directly contradicted the AMPK hypothesis. Most dramatic were studies showing that metformin’s actions to suppress hepatic gluconeogenesis persisted despite genetic deletion of the AMPK’s catalytic domain (Foretz et al., 2010 ). More recent studies identified additional or alternative targets, such as cAMP signaling in the liver (Miller et al., 2013 ) or glycogen synthase kinase-3 (Link, 2003 ). Other work showed that the phosphorylation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase and acetyl-CoA carboxylase 2 are involved in regulating lipid homeostasis and improving insulin sensitivity after exposure to metformin (Fullerton et al., 2013 ).

Although there are strong data to support each of these pathways, it is not entirely clear which signaling pathway(s) is most essential to the actions of metformin in hepatocytes. Metformin clearly inhibits complex I and concomitantly decreases ATP and increases AMP. The latter results in AMPK activation, reduced fatty acid synthesis, and improved insulin receptor activation, and increased AMP has been shown to inhibit adenylate cyclase to reduce cAMP and thus protein kinase A activation. Downstream, this reduces the expression of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and glucose 6-phosphatase via decreased cAMP response element-binding protein, the cAMP-sensitive transcription factor. Decreased PKA also promotes ATP-dependent 6-phosphofructokinase, liver type activity via fructose 2,6-bisphosphate and reduces gluconeogenesis, as fructose-bisphosphatase 1 is inhibited by fructose 2,6-bisphosphate, along with other mechanisms (Rena et al., 2017 ; Pernicova and Korbonits, 2014 ).

More recent work has shown that metformin at pharmacological rather than suprapharmacological doses increases mitochondrial respiration and complex 1 activity and also increases mitochondrial fission, now thought to be critical for maintaining proper mitochondrial density in hepatocytes and other cells. This improvement in respiratory activity occurs via AMPK activation (Wang et al., 2019 ).

Although the liver has historically been the major suspected site of metformin action, recent studies have suggested that the gut instead of the liver is a major target, a concept supported by the increased efficacy of extended-release formulations of metformin that reside for a longer duration in the gut after their administration (Buse et al., 2016 ). An older, but in our view an important observation, is that the intravenous administration of metformin has little or no effect on blood glucose, whereas, in contrast, orally administered metformin is much more effective (Bonora et al., 1984 ). Recent imaging studies using labeled glucose have shown directly that metformin stimulates glucose uptake by the gut in patients with T2D to reduce plasma glucose concentrations (Koffert et al., 2017 ; Massollo et al., 2013 ). Additionally, it is possible that metformin may exert its effect in the gut by inducing intestinal glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) release (Mulherin et al., 2011 ; Preiss et al., 2017) to potentiate beta cell insulin secretion and by stimulating the central nervous system (CNS) to exert control over both blood glucose and liver function. Indeed, CNS effects produced by metformin have been proposed to occur via the local release of GLP-1 to activate intestinal nerve endings of ascending nerve pathways that are involved in CNS glucose regulation (Duca et al., 2015 ). Lastly, several papers have now implicated that metformin may act by altering the gut microbiome, suggesting that changes in gut flora may be critical for metformin’s actions (McCreight et al., 2016 ; Wu et al., 2017 ; Devaraj et al., 2016 ). A new study proposed that activation of the intestinal farnesoid X receptor may be the means by which microbiota alter hyperglycemia (Sun et al., 2018 ). However, these studies will require more mechanistic detail and confirmation before they can be fully accepted by the field. In addition to the action of metformin on gut flora, the production of imidazole propionate by gut microbes in turn has been shown to interfere with metformin action through a p38-dependent mechanism and AMPK inhibition. Levels of imidazole propionate are especially higher in patients with T2D who are treated with metformin (Koh et al., 2020 ).

In summary, the combined contribution of these various effects of metformin on multiple cellular targets residing in many tissues may be key to the benefits of metformin treatment on lowering blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes (Foretz et al., 2019 ). In contrast, exciting new work showing metformin leads to weight loss by increasing circulating levels of the peptide hormone growth differentiation factor 15 and activation of brainstem glial cell-derived neurotropic factor family receptor alpha like receptors to reduce food intake and energy expenditure works independently of metformin’s glucose-lowering effect (Coll et al., 2020 ).

B. Sulfonylureas and Beta Cell Burnout

The class of compounds known as sulfonylureas includes one of the oldest oral antidiabetic drugs in the pharmacopoeia: tolbutamide. Tolbutamide is a “first generation” oral sulfonylurea secretagogue whose clinical usefulness is due to its prompt stimulation of insulin release from pancreatic beta cells. “Second generation” sulfonylureas include drugs such as glyburide, gliclazide, and glipizide. Sulfonylureas act by binding to a high affinity sulfonylurea binding site, the sulfonylurea receptor 1 subunit of the K(ATP) channel, which closes the channel. These drugs mimic the physiologic effects of glucose, which closes the K(ATP) channel by raising cytosolic ATP/ADP. This in turn provokes beta cell depolarization, resulting in increased Ca 2+ influx into the beta cell (Ozanne et al., 1995 ; Ashcroft and Rorsman, 1989 ; Nichols, 2006 ). Importantly, sulfonylureas, and all drugs that directly increase insulin secretion, are associated with hypoglycemia, which can be severe, and which limits their widespread use in the clinic (Yu et al., 2018 ). Meglitinides are another class of oral insulin secretagogues that, like the sulfonylureas, bind to sulfonylurea receptor 1 and inhibit K(ATP) channel activity (although at a different site of action). The rapid kinetics of the meglitinides enable them to effectively blunt the postprandial glycemic excursions that are a hallmark (along with elevated fasting glucose) of T2D (Rosenstock et al., 2004). However, the need for their frequent dosing (e.g., administration before each meal) has limited their appeal to patients.

The efficacy of sulfonylureas is known to decrease over time, leading to failure of the class for effective long-term treatment of T2D (Harrower, 1991 ). More broadly, it is now widely accepted that the number of functional beta cells in humans declines during the progression of T2D. Thus, one would expect that due to this decline, all manner of oral agents intended to target the beta cell and increase its cell function (and especially insulin secretion) will fail over time (RISE Consortium, 2019 ), a process referred to as “beta cell failure” (Prentki and Nolan, 2006 ). Currently, treatments that can expand beta cell mass or improve beta cell function or survival over time are not yet available for use in the clinic. As a result, treatments that may be able to help patients cope with beta cell burnout such as islet cell transplantation, insulin pumps, or stem cell therapy are alternatives that will be discussed below.

C. Ca 2+ Channel Blockers and Type 1 Diabetes

Strategies to treat and prevent T1D have historically focused on ameliorating the toxic consequences of immune dysregulation resulting in autoimmune destruction of pancreatic beta cells. More recently, a concerted focus on alleviating the intrinsic beta cell defects (Sims et al., 2020 ; Soleimanpour and Stoffers, 2013 ) that also contribute to T1D pathogenesis have been gaining traction at both the bench and the bedside. Several recent preclinical studies suggest that Ca 2+ -induced metabolic overload induces beta cell failure (Osipovich et al., 2020 ; Stancill et al., 2017 ; Xu et al., 2012 ), with the potential that excitotoxicity contributes to beta cell demise in both T1D and T2D, similar to the well known connection between excitotoxicity and, concomitantly, increased Ca 2+ loading of the cells and neuronal dysfunction. Indeed, the use of the phenylalkylamine Ca 2+ channel blocker verapamil has been successful in ameliorating beta cell dysfunction in preclinical models of both T1D and T2D (Stancill et al., 2017 ; Xu et al., 2012 ). Verapamil is a well known blocker of L-type Ca 2+ channels, and, in normally activated beta cells, it limits Ca 2+ entry into the beta cell (Ohnishi and Endo, 1981 ; Vasseur et al., 1987 ). This would be expected to, in turn, alter the expression of many Ca 2+ influx–dependent beta cell genes (Stancill et al., 2017 ), and the evidence to date suggests it is likely that verapamil preserves beta cell function in diabetes models by repressing thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP) expression and thus protecting the beta cell. This is somewhat surprising given the physiologic role of Ca 2+ is to acutely trigger insulin secretion; this process would be expected to be inhibited by L-type Ca 2+ channel blockers (Ashcroft and Rorsman, 1989 ; Satin et al., 1995 ).

Hyperglycemia is a well known inducer of TXNIP expression, and a lack of TXNIP has been shown to protect against beta cell apoptosis after inflammatory stress (Chen et al., 2008a ; Shalev et al., 2002 ; Chen et al., 2008b ). Excitingly, the use of verapamil in patients with recent-onset T1D improved beta cell function and improved glycemic control for up to 12 months after the initiation of therapy, suggesting there is indeed promise for targeting calcium and TXNIP activation in T1D. Use of verapamil for a repurposed indication in the preservation of beta cell function in T1D is attractive due its well known safety profile as well as its cardiac benefits (Chen et al., 2009 ). Although the long-term efficacy of verapamil to maintain beta cell function in vivo is unclear, a recently described TXNIP inhibitor may also show promise in suppressing the hyperglucagonemia that also contributes to glucose intolerance in T2D (Thielen et al., 2020 ). As there is a clear need for increased Ca 2+ influx into the beta cell to trigger and maintain glucose-dependent insulin secretion (Ashcroft and Rorsman, 1990 ; Satin et al., 1995 ), it remains to be seen how well regulated insulin secretion is preserved in the presence of L-type Ca 2+ channel blockers like verapamil in the system. One might speculate that reducing but not fully eliminating beta cell Ca 2+ influx might reduce TXNIP levels while preserving enough influx to maintain glucose-stimulated insulin release. Alternatively, these two phenomena may operate on entirely different time scales. At present, these issues clearly will require further investigation.

D. GLP-1 and the Incretins

Studies dating back to the 1960s revealed that administering glucose in equal amounts via the peripheral circulation versus the gastrointestinal tract led to dramatically different amounts of glucose-induced insulin secretion (Elrick et al., 1964 ; McIntyre et al., 1964 ; Perley and Kipnis, 1967 ). Gastrointestinal glucose administration greatly increased insulin secretion versus intravenous glucose, and this came to be known as the “incretin effect” (Nauck et al., 1986a ; Nauck et al., 1986b ). Subsequent work showed that release of the gut hormone GLP-1 mediated this effect such that food ingestion induced intestinal cell hormone secretion. GLP-1 so released would then circulate to the pancreas via the blood to prime beta cells to secrete more insulin when glucose became elevated because these hormones stimulated beta cell cAMP formation (Drucker et al., 1987 ). The discovery that a natural peptide corresponding to GLP-1 could be found in the saliva of the Gila monster, a desert lizard, hastened progress in the field, and ample in vitro studies subsequently confirmed that GLP-1 potentiated insulin secretion in a glucose-dependent manner. GLP-1 has little or no significant action on insulin secretion in the absence of elevated glucose (such as might typically correspond to the postprandial case or during fasting), thus minimizing the likelihood of hypoglycemia provoked by GLP-1 in treated patients (Kreymann et al., 1987 ). Although not completely understood, the glucose dependence of GLP-1 likely reflects the requirement for adenine nucleotides to close glucose-inhibited K(ATP) channels and thus subsequently activate Ca 2+ influx–dependent insulin exocytosis. Besides potentiating GSIS at the level of the beta cell, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R) agonists also decrease glucagon secretion from pancreatic islet alpha cells, reduce gastric emptying, and may also increase beta cell proliferation, among other cellular actions (reviewed in Drucker, 2018 ; Muller et al., 2019).

Intense interest in the incretins by basic scientists, clinicians, and the pharma community led to the rapid development of new drugs for treating primarily T2D. These drugs include a range of GLP-1R agonists and inhibitors of the incretin hormone degrading enzyme dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP4), whose targeting increases the half-lives of GLP-1 and gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) and thereby increases protein hormone levels in plasma. GLP-1R agonists have been associated with not only a lowering of plasma glucose but also weight loss, decreased appetite, reduced risk of cardiovascular events, and other favorable outcomes (Gerstein et al., 2019; Hernandez et al., 2018; Husain et al., 2019; Marso et al., 2016a; Marso et al., 2016b ; Buse et al., 2004). Regarding their untoward actions, although hypoglycemia is not a major concern, there have been reports of pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer from use of GLP-1R agonists. However, a recent meta-analysis covering four large-scale clinical trials and over 33,000 participants noted no significantly increased risk for pancreatitis/pancreatic cancer in patients using GLP-1R agonists (Bethel et al., 2018).

Ongoing and future developments in the use of proglucagon-derived peptides such as GLP-1 and glucagon include the use of combined GLP-1/GIP, glucagon/GLP-1, and agents targeting all three peptides in combination (reviewed in Alexiadou and Tan, 2020 ). Although short-term infusions of GLP-1 with GIP failed to yield metabolic benefits beyond those seen with GLP-1 alone (Bergmann et al., 2019 ), several GLP-1/GIP dual agonists are currently in development and have shown promising metabolic results in clinical trials (Frias et al., 2017 ; Frias et al., 2020 ; Frias et al., 2018 ). At the level of the pancreatic islet, beneficial effects of dual GLP-1/GIP agonists may be related to imbalanced and biased preferences of these agonists for the gastric inhibitory polypeptide receptor over the GLP-1R (Willard et al., 2020 ) and possibly were not simply to dual hormone agonism in parallel. Dual glucagon/GLP-1 agonist therapy has also been shown to have promising metabolic effects in humans (Ambery et al., 2018 ; Tillner et al., 2019 ). Oxyntomodulin is a natural dual glucagon/GLP-1 receptor agonist and proglucagon cleavage product that is also secreted from intestinal enteroendocrine cells, which has beneficial effects on insulin secretion, appetite regulation, and body weight in both humans and rodents (Cohen et al., 2003 ; Dakin et al., 2001 ; Dakin et al., 2002 ; Shankar et al., 2018 ; Wynne et al., 2005 ). Interestingly, alpha cell crosstalk to beta cells through the combined effects of glucagon and GLP-1 is necessary to obtain optimal glycemic control, suggesting a potential pathway for therapeutic dual glucagon/GLP-1 agonism within the islets of patients with T2D (Capozzi et al., 2019a ; Capozzi et al., 2019b ). Although the early results appear promising, more studies will be necessary to better understand the mechanistic and clinical impacts of these multiagonist agents.

E. DPP4 Inhibitors

Inhibition of DPP4, the incretin hormone degrading enzyme, is one of the most common T2D treatments to increase GLP-1 and GIP plasma hormone levels. These DPP4 inhibitors or “gliptins” are generally used in conjunction with other T2D drugs such as metformin or sulfonylureas to obtain the positive benefits discussed above (Lambeir et al., 2008 ). DPP4 is a primarily membrane-bound peptidase belonging to the serine peptidase/prolyl oligopeptidase gene family, which cleaves a large number of substrates in addition to the incretin hormones (Makrilakis, 2019 ). DPP4 inhibitors provide glucose-lowering benefits while being generally well tolerated, and the variety of available drugs (including sitagliptin, saxagliptin, vildagliptin, alogliptin, and linagliptin) with slightly different dosing frequency, half-life, and mode of excretion/metabolism allows for use in multiple patient populations (Makrilakis, 2019 ). This includes the elderly and individuals with renal or hepatic insufficiency (Makrilakis, 2019 ).

Although hypoglycemia is not a concern for DPP4 inhibitor use, other considerations should be made. DPP4 inhibitors tend to be more expensive than metformin or other second-line oral drugs in addition to having more modest glycemic effects than GLP-1R agonists (Munir and Lamos, 2017 ). Finally, meta-analysis of randomized and observational studies concluded that heart failure in patients with T2D was not associated with use of DPP4 inhibitors; however, this study was limited by the short follow-up and lack of high-quality data (Li et al., 2016 ). Thus, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) did recommend assessing risk of heart failure hospitalization in patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease, prior heart failure, and chronic kidney disease when using saxagliptin and alogliptin (Munir and Lamos, 2017 ).

F. Sodium Glucose Cotransporter 2 Inhibitors

A recent development in the field of T2D drugs are sodium glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, which have an interesting and very different mechanism of action. Within the proximal tubule of the nephron, SGLT2 transports ingested glucose into the lumen of the proximal tubule between the epithelial layers, thereby reclaiming glucose by this reabsorption process (reviewed in Vallon, 2015 ). SGLT2 inhibitors target this transporter and increase glucose in the tubular fluid and ultimately increase it in the urine. In patients with diabetes, SGLT2 inhibition results in a lowering of plasma glucose with urine glucose content rising substantially (Adachi et al., 2000 ; Vallon, 2015 ). These drugs, although they are relatively new, have become an area of great interest for not only patients with T2D (Grempler et al., 2012 ; Imamura et al., 2012 ; Meng et al., 2008 ; Nomura et al., 2010 ) but also for patients with T1D (Luippold et al., 2012 ; Mudaliar et al., 2012 ). Part of their appeal also rests on reports that their use can lead to a statistically significant decline in cardiac events that are known to occur secondarily to diabetes, possibly independently of plasma glucose regulation (reviewed in Kurosaki and Ogasawara, 2013 ). Although the long-term consequences of their clinical use cannot yet be determined, raising the glucose content of the urogenital tract leads to an increased risk of urinary tract infections and other related infections in some patients (Kurosaki and Ogasawara, 2013 ).

Another recent concern about the use of SGLT2 inhibitors has been the development of normoglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). Despite the efficacy of SGLT2 inhibitors, observations of hyperglucagonemia in patients with euglycemic DKA has led to a number of recent studies focused on SGLT2 actions on pancreatic islets. Initial studies of isolated human islets treated with small interfering RNA directed against SGLT2 and/or SGLT2 inhibitors demonstrated increased glucagon release. These studies were complemented by the finding of elevations in glucagon release in mice that were administered SGLT2 inhibitors in vivo (Bonner et al., 2015 ). Insights into the possible mechanistic links between SGLT2 inhibition, DKA frequency, and glucagon secretion in humans may relate to the observation of heterogeneity in SGLT2 expression, as SGLT2 expression appears to have a high frequency of interdonor and intradonor variability (Saponaro et al., 2020 ). More recently, both insulin and GLP-1 have been demonstrated to modulate SGLT2-dependent glucagon release through effects on somatostatin release from delta cells (Vergari et al., 2019 ; Saponaro et al., 2019 ), suggesting potentially complex paracrine effects that may affect the efficacy of these compounds.

On the other hand, several recent studies question that the development of euglycemic DKA after SGLT2 inhibitor therapy may be through alpha cell–dependent mechanisms. Three recent studies found no effect of SGLT2 inhibitors to promote glucagon secretion in mouse and/or rat models and could not detect SGLT2 expression in human alpha cells (Chae et al., 2020 ; Kuhre et al., 2019 ; Suga et al., 2019 ). A fourth study demonstrated only a brief transient effect of SGLT2 inhibition to raise circulating glucagon concentrations in immunodeficient mice transplanted with human islets, which returned to baseline levels after longer exposures to SGLT2 inhibitors (Dai et al., 2020 ). Furthermore, SGLT2 protein levels were again undetectable in human islets (Dai et al., 2020 ). These results could suggest alternative islet-independent mechanisms by which patients develop DKA, including alterations in ketone generation and/or clearance, which underscore the additional need for further studies both in molecular models and at the bedside. Nevertheless, SGLT2 inhibitors continue to hold promise as a valuable therapy for T2D, especially in the large segment of patients who also have superimposed cardiovascular risk (McMurray et al., 2019; Wiviott et al., 2019; Zinman et al., 2015).

G. Thiazolidinediones

Once among the most commonly used oral agents in the armamentarium to treat T2D, thiazolidinediones (TZDs) were clinically popular in their utilization to act specifically as insulin sensitizers. TZDs improve peripheral insulin sensitivity through their action as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) γ agonists, but their clinical use fell sharply after studies suggested a connection between cardiovascular toxicity with rosiglitazone and bladder cancer risk with pioglitazone (Lebovitz, 2019 ). Importantly, an FDA panel eventually removed restrictions related to cardiovascular risk with rosiglitazone in 2013 (Hiatt et al., 2013 ). Similarly, concerns regarding use of bladder cancer risk with pioglitazone were later abated after a series of large clinical studies found that pioglitazone did not increase bladder cancer (Lewis et al., 2015 ; Schwartz et al., 2015 ). However, usage of TZDs had already substantially decreased and has not since recovered.

Although concerns regarding edema, congestive heart failure, and fractures persist with TZD use, there have been several studies suggesting that TZDs protect beta cell function. In the ADOPT study, use of rosiglitazone monotherapy in patients newly diagnosed with T2D led to improved glycemic control compared with metformin or sulfonylureas (Kahn et al., 2006). Later analyses revealed that TZD-treated subjects had a slower deterioration of beta cell function than metformin- or sulfonylurea-treated subjects (Kahn et al., 2011). Furthermore, pioglitazone use improved beta cell function in the prevention of T2D in the ACT NOW study (Defronzo et al., 2013; Kahn et al., 2011). Mechanistically, it is unclear if TZDs lead to beneficial beta cell function through direct effects or through indirect effects of reduced beta cell demand due to enhanced peripheral insulin sensitivity. Indeed, a beta cell–specific knockout of PPAR γ did not impair glucose homeostasis, nor did it impair the antidiabetic effects of TZD use in mice (Rosen et al., 2003 ). However, other reports demonstrated PPAR-responsive elements within the promoters of both glucose transporter 2 and glucokinase that enhance beta cell glucose sensing and function, which could explain beta cell–specific benefits for TZDs (Kim et al., 2002 ; Kim et al., 2000 ). Furthermore, TZDs have been shown to improve beta cell function by upregulating cholesterol transport (Brunham et al., 2007 ; Sturek et al., 2010 ). Additionally, use of TZDs in the nonobese diabetic (NOD) mouse model of T1D augmented the beta cell unfolded protein response and prevented beta cell death, suggesting potential benefits for TZDs in both T1D and T2D (Evans-Molina et al., 2009 ; Maganti et al., 2016 ). With a now refined knowledge of demographics in which to avoid TZD treatment due to adverse effects, together with genetic approaches to identify candidates more likely to respond effectively to TZD therapy (Hu et al., 2019 ; Soccio et al., 2015 ), it remains to be seen if TZD therapy will return to more prominent use in the treatment of diabetes.

H. Insulin and Beyond: The Use of “Smart” Insulin and Closed Loop Systems in Diabetes Treatment

Due to recombinant DNA technology, numerous insulin analogs are now available in various forms ranging from fast acting crystalline insulin to insulin glargine; all of these analogs exhibit equally effective insulin receptor binding. Most are generated by altering amino acids in the B26–B30 region of the molecule (Kurtzhals et al., 2000 ). The American Diabetes Association delineates these insulins by their 1) onset or time before insulin reaches the blood stream, 2) peak time or duration of maximum blood glucose–lowering efficacy, and 3) the duration of blood glucose–lowering time. Insulin administration is independent of the residuum of surviving and/or functioning beta cells in the patient and remains the principal pharmacological treatment of both T1D and T2D. The availability of multiple types of delivery methods, i.e., insulin pens, syringes, pumps, and inhalants, provides clinicians with a solid and varied tool kit with which to treat diabetes. The downsides, however, are that 1) hypoglycemia is a constant threat, 2) proper insulin doses are not trivial to calculate, 3) compliance can vary especially in children and young adults, and 4) there can be side effects of a variety of types. Nonetheless, insulin therapy remains a mainstay treatment of diabetes.

To eliminate the downsides of insulin therapy, research in the past several decades has worked toward generating glucose-sensitive or “smart” insulin molecules. These molecules change insulin bioavailability and become active only upon high blood glucose using glucose-binding proteins such as concanavalin A, glucose oxidase to alter pH sensitivity, and phenylboronic acid (PBA), which forms reversible ester linkages with diol-containing molecules including glucose itself (reviewed in Rege et al., 2017 ). Indeed, promising recent studies included various PBA moieties covalently bonded to an acylated insulin analog (insulin detemir, which contains myristic acid coupled to Lys B29 ). The detemir allows for binding to serum albumin to prolong insulin’s half-life in the circulation, and PBA provided reversible glucose binding (Chou et al., 2015 ). The most promising of the PBA-modified conjugates showed higher potency and responsiveness in lowering blood glucose levels compared with native insulin in diabetic mouse models and decreased hypoglycemia in healthy mice, although the molecular mechanisms have not yet been determined (Chou et al., 2015 ).

An additional active area of research includes structurally defining the interaction between insulin and the insulin receptor ectodomain. Importantly, a major conformational change was discovered that may be exploited to impair insulin receptor binding under hypoglycemic conditions (Menting et al., 2013 ; Rege et al., 2017 ). Challenges in the design, testing, and execution of glucose-responsive insulins may be overcome by the adaptation of novel modeling approaches (Yang et al., 2020 ), which may allow for more rapid screening of candidate compounds.

Technologies have also progressed in the field of artificial pancreas design and development. Currently two “closed loop” systems are now available: Minimed 670G from Medtronic and Control-IQ from Tandem Diabetes Care. Both systems use a continuous glucose monitor, insulin pump, and computer algorithm to predict correct insulin doses and administer them in real time. Such algorithm systems also take into account insulin potency, the rate of blood glucose increase, and the patient’s heart rate and temperature to adjust insulin delivery levels during exercise and after a meal. In addition, so-called “artificial pancreas” systems have also been clinically tested, which use both insulin and glucagon and as such result in fewer reports of hypoglycemic episodes (El-Khatib et al., 2017 ). These types of systems will continue to become more popular as the development of room temperature–stable glucagon analogs continue, such as GVOKE by Xeris Pharmaceuticals (currently available in an injectable syringe) and Baqsimi, a nasally administered glucagon from Eli Lilly.

I. Present and Future Therapies: Beta Cell Transplantation, Replication, and Immune Protection

1. islet transplantation.

The idea to use pancreatic allo/xenografts to treat diabetes remarkably dates back to the late 1800s (Minkowski, 1892 ; Pybus, 1924 ; Williams, 1894 ). Before proceeding to the discovery of insulin (together with Best, MacLeod, and Collip), Frederick Banting also postulated the potential for transplantation of pancreatic tissue emulsions to treat diabetes in dog models in a notebook entry in 1921 (Bliss, 1982 ). Decades later, Paul Lacy, David Scharp, and colleagues successfully isolated intact functional pancreatic islets and transplanted them into rodent models (Kemp et al., 1973 ). These studies led to the initial proof of concept studies for humans, with the first successful islet transplant in a patient with T1D occurring in 1977 (Sutherland et al., 1978 ). A rapid expansion of islet transplantation, inspired by these original studies led to key observations of successfully prolonged islet engraftment by the “Edmonton protocol” whereby corticosteroid-sparing immunosuppression was applied, and islets from at least two allogeneic donors were used to achieve insulin independence (Shapiro et al., 2000 ). More recent work has focused on improving upon the efficiency and long-term engraftment of allogeneic transplants leading to more prolonged graft function (to the 5-year mark) and successful transplantation from a single islet donor (Hering et al., 2016; Hering et al., 2005 ; Rickels et al., 2013 ). Critical to these efforts to improve the success rate was the recognition that the earlier generation of immunosuppressive agents to counter tissue rejection was toxic to islets (Delaunay et al., 1997 ; Paty et al., 2002 ; Soleimanpour et al., 2010 ) and that more appropriate and less toxic agents were needed (Hirshberg et al., 2003 ; Soleimanpour et al., 2012 ).

Certainly, islet transplantation as a therapeutic approach for patients with T1D has been scrutinized due to several challenges, including (but not limited to) the lack of available donor supply to contend with demand, limited long-term functional efficacy of islet allografts, the potential for re-emergence of autoimmune islet destruction and/or metabolic overload-induced islet failure, and significant adverse effects of prolonged immunosuppression (Harlan, 2016 ). Furthermore, although islet transplantation is not currently available for individuals with T2D, simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation in T2D had similar favorable outcomes to simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation in T1D; therefore, islet-kidney transplantation may eventually be a feasible option to treat T2D, as patients will already be on immunosuppressors (Sampaio et al., 2011 ; Westerman et al., 1983 ). An additional significant obstacle is the tremendous expense associated with islet transplantation therapy. Indeed, the maintenance, operation, and utilization of an FDA-approved and Good Manufacturing Practice–compliant islet laboratory can lead to operating costs at nearly $150,000 per islet transplant, which is not cost effective for the vast majority of patients with T1D (Naftanel and Harlan, 2004 ; Wallner et al., 2016 ). At present, the focus has been to obtain FDA approval for islet allo-transplantation as a therapy for T1D to allow for insurance compensation (Hering et al., 2016; Rickels and Robertson, 2019 ). In the interim, the islet biology, stem cell, immunology, and bioengineering communities have continued the development of cell-based therapies for T1D by other approaches to overcome the challenges identified during the islet transplantation boom of the 1990s and 2000s.

2. Pharmacologic Induction of Beta Cell Replication

Besides transplantation, progress in islet cell biology and especially in developmental biology of beta cells over several decades raised the additional possibility that beta cell mass reduction in diabetes might be countered by increasing beta cell number through mitogenic means. A key method to expand pancreatic beta cell mass is through the enhancement of beta cell replication. Although the study of pancreatic beta cell replication has been an area of intense focus in the beta cell biology field for several decades, only recently has this seemed truly feasible. Seminal studies identified that human beta cells are essentially postmitotic, with a rapid phase of growth occurring in the prenatal period that dramatically tapers off shortly thereafter (Gregg et al., 2012 ; Meier et al., 2008 ). The plasticity of rodent beta cells is considerably higher than that of human beta cells (Dai et al., 2016 ), which has led to a renewed focus on validation of pharmacologic agents to enhance rodent beta cell replication using isolated and/or engrafted human islets (Bernal-Mizrachi et al., 2014 ; Kulkarni et al., 2012 ; Stewart et al., 2015 ). Indeed, a large percentage of agents that were successful when applied to rodent systems were largely unsuccessful at inducing replication in human beta cells (Bernal-Mizrachi et al., 2014 ; Kulkarni et al., 2012 ; Stewart et al., 2015 ). However, several recent studies have begun to make significant progress on successfully pushing human beta cells to replicate.

Several groups have reported successful human beta cell proliferation, both in vitro and in vivo, in response to inhibitors of the dual specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1A (DYRK1A). These inhibitors include harmine, INDY, GNF4877, 5-iodotubericidin, leucettine-42, TG003, AZ191, CC-401, and more specific, recently developed DYRK1A inhibitors (Ackeifi et al., 2020 ). Although DYRK1A is conclusively established as the important mediator of human beta cell proliferation, comprehensively determining other cellular targets and if additional gene inhibition amplifies the proliferative response is still in process. New evidence from Wang and Stewart shows dual specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase 1B to be an additional mitogenic target and also describes variability in the range of activated kinases within cells and/or levels of inhibition for the many DYRK1A inhibitors listed above (Ackeifi et al., 2020 ). Interestingly, opposite to these human studies, earlier mouse studies from the Scharfmann group demonstrated that Dyrk1a haploinsufficiency leads to decreased proliferation and loss of beta cell mass (Rachdi et al., 2014b ). In addition, overexpression of Dyrk1a in mice led to beta cell mass expansion with increased glucose tolerance (Rachdi et al., 2014a ).

Although important differences in beta cell proliferative capacity have been shown between human and rodent species, there are also significant differences in the mitogenic capacity of beta cells from juvenile, adult, and pregnant individuals. This demonstrates that proliferative stimuli appear to act within the complex islet, pancreas, and whole-body environments unique to each time point. For example, the administration of the hormones platelet-derived growth factor alpha or GLP-1 result in enhanced proliferation in juvenile human beta cells yet are ineffective in adult human beta cells (Chen et al., 2011 ; Dai et al., 2017 ). This has been shown to be due to a loss of platelet-derived growth factor alpha receptor expression as beta cells age but appears to be unrelated to GLP-1 receptor expression levels (Chen et al., 2011 ). Indeed, the GLP-1 receptor is highly expressed in adult beta cells, and GLP-1 secretion increases insulin secretion, as detailed previously; however, the induction of proliferative factors such as nuclear factor of activated T cells, cytoplasmic 1; forkhead box protein 1; and cyclin A1 is only seen in juvenile islets (Dai et al., 2017 ). Human studies using cadaveric pancreata from pregnant donors also showed increased beta cell mass, yet lactogenic hormones from the pituitary or placenta (prolactin, placental lactogen, or growth hormone) are unable to stimulate proliferation in human beta cells despite their ability to produce robust proliferation in mouse beta cells (reviewed in Baeyens et al., 2016 ). Experiments overexpressing mouse versus human signal transducer and activator of transcription 5, the final signaling factor inducing beta cell adaptation, in human beta cells allows for prolactin-mediated proliferation revealing fundamental differences in prolactin pathway competency in human (Chen et al., 2015 ). Overcoming the barrier of recapitulating human pregnancy’s effect on beta cells through isolating placental cells or blood serum during pregnancy may result in the discovery of a factor(s) that facilitates the increase in beta cell mass observed during human pregnancy.

Mechanisms that stimulate beta cell proliferation have also been discovered from studying genetic mutations that result in insulinomas, spontaneous insulin-producing beta cell adenomas. The most common hereditary mutation occurs in the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) gene. Indeed, administration of a MEN1 inhibitor in addition to a GLP-1 agonist (which cannot induce proliferation alone) is able to increase beta cell proliferation in isolated human islets through synergistic activation of KRAS proto-oncogene, GTPase downstream signals (Chamberlain et al., 2014 ). Interestingly, MEN1 mutations are uncommon in sporadic insulinomas, yet assaying genomic and epigenetic changes in a large cohort of non-MEN1 insulinomas found alterations in trithorax and polycomb chromatin modifying genes that were functionally related to MEN1 (Wang et al., 2017 ). Stewart and colleagues hypothesized that changes in histone 3 lysine 27 and histone 3 lysine 4 methylation status led to increased enhancer of zeste homolog 2 and lysine demethylase 6A, decreased cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1C, and thereby increased beta cell proliferation, among other phenotypes. They also proposed that these findings help to explain why increased proliferation always occurs despite broad heterogeneity of mutations found between individual insulinomas (Wang et al., 2017 ).

Although factors that induce proliferation are continuing to be discovered, there are drawbacks that still limit their clinical application. Harmine and other DYRK1A inhibitors are not beta cell specific, nor have all their cellular targets been determined (Ackeifi et al., 2020 ). Targeting other pathways to induce human beta cell proliferation such as modulation of prostaglandin E2 receptors (i.e., inhibition of prostaglandin E receptor 3 alone or in combination with prostaglandin E receptor 4 activation) showed promising increases in proliferative rate yet suffers from the same lack of specificity (Carboneau et al., 2017 ). Induction of proliferation may also come at the expense of glucose sensing as in insulinomas, which have an increased expression of “disallowed genes” and alterations in glucose transporter and hexokinase expression (Wang et al., 2017 ). A further untoward consequence that must be avoided is the production of cancerous cells through unchecked proliferation. Finally, increasing beta cell mass through low rates of proliferation may increase the pool of functional insulin-secreting cells in T2D, but without additional measures, these beta cells will still ultimately be targeted for immune cell destruction in T1D.

3. Beta Cell Stress Relieving Therapies

Metabolic, inflammatory, and endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress contribute to beta cell dysfunction and failure in both T1D and T2D. Although reduction of metabolic overload of beta cells by early exogenous insulin therapy or insulin sensitizers can temporarily reduce loss of beta cell mass/function early in diabetes, a focus on relieving ER and inflammatory stress is also of interest to preserve beta cell health.

ER stress is a well known contributor to beta cell demise both in T1D and T2D (Laybutt et al., 2007 ; Marchetti et al., 2007 ; Marhfour et al., 2012 ; Tersey et al., 2012 ) and a target of interest in the prevention of beta cell loss in both diseases. Preclinical studies suggest that the use of chemical chaperones, including 4-phenylbutyric acid and tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA), to alleviate ER stress improves beta cell function and insulin sensitivity in mouse models of T2D (Cnop et al., 2017 ; Ozcan et al., 2006 ). Furthermore, TUDCA has been shown to preserve beta cell mass and reduce ER stress in mouse models of T1D (Engin et al., 2013 ). Interestingly, TUDCA has shown promise at improving insulin action in obese nondiabetic human subjects, yet beta cell function and insulin secretion were not assessed (Kars et al., 2010 ). A clinical trial regarding the use of TUDCA for humans with new-onset T1D is also ongoing ( {"type":"clinical-trial","attrs":{"text":"NCT02218619","term_id":"NCT02218619"}} NCT02218619 ). However, a note of caution regarding use of ER chaperones is that they may prevent low level ER stress necessary to potentiate beta cell replication during states of increased insulin demand (Sharma et al., 2015 ), suggesting that the broad use of ER chaperone therapies should be carefully considered.

The blockade of inflammatory stress has long been an area of interest for treatments of both T1D and T2D (Donath et al., 2019 ; Eguchi and Nagai, 2017 ). Indeed, use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which block cyclooxygenase, have been observed to improve metabolic control in patients with diabetes since the turn of the 20th century (Williamson, 1901 ). Salicylates have been shown to improve insulin secretion and beta cell function in both obese human subjects and those with T2D (Fernandez-Real et al., 2008; Giugliano et al., 1985 ). However, another NSAID, salsalate, has not been shown to improve beta cell function while improving other metabolic outcomes (Kim et al., 2014 ; Penesova et al., 2015 ), possibly suggesting distinct mechanisms of action for anti-inflammatory compounds. The regular use of NSAIDs to enhance metabolic outcomes is also often limited to the tolerability of long-term use of these agents due to adverse effects. Recently, golilumab, a monoclonal antibody against the proinflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor alpha, was demonstrated to improve beta cell function in new-onset T1D, suggesting that targeting the underlying inflammatory milieu may have benefits to preserve beta cell mass and function in T1D (Quattrin et al., 2020). Taken together, both new and old approaches to target beta cell stressors still remain of long-term interest to improve beta cell viability and function in both T1D and T2D.

3. New Players to Induce Islet Immune Protection