Music Thesis Statements

Music has been shown to have a profound effect on the human brain. It can alter our mood, relieve stress, and even boost our immune system. Music therapy is an increasingly popular treatment for a variety of conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease, autism, and depression.

While the exact mechanisms by which music exerts its effects on the brain are not fully understood, there is no doubt that it has a powerful impact. In some cases, music may even be more effective than medication. If you are struggling with a mental health issue, consider giving music therapy a try.

Music stimulates brain development and productive function. In humans, music is an instinctive desire to create and enjoy, it is not forgotten by diseases such as Parkinson’s or dementia, and it has been shown to assist kids with ADHD and ADD focus. Charles Darwin, together with other experts, believes that music was used to aid human evolution and bonding over time.

There are different types of music for different purposes, such as: for relaxation, concentration, to increase productivity or creativity, to improve sleep quality, to boost energy and mood, to reduce stress levels and anxiety. Music can also be used as a form of therapy to help treat various conditions such as: Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, depression, stroke recovery and more.

A study done at the University of Southern California found that when people with Alzheimer’s disease listened to personalized music, it activated regions of their brain that were otherwise inactive. The music helped the patients reconnect with lost memories and improved their verbal skills.

In another study done at Stanford University School of Medicine, it was found that music can help reduce stress hormones and inflammation in the body. The study was done on rats, but the findings can be translated to humans as well.

So, what is it about music that has such a powerful effect on the brain and body?

Music affects different areas of the brain, which in turn affects our emotions, behavior and physical state. When we listen to music, our brains release dopamine, which is a feel-good chemical that makes us happy and motivated. Dopamine also helps to improve memory, focus and concentration.

In addition to releasing dopamine, music also activates the autonomic nervous system, which controls things like heart rate and blood pressure. This is why music can have such a profound effect on our physical state – it can make us feel more relaxed or energized, depending on the type of music we’re listening to.

Music is a language that people can use to better communicate emotions, sentiments, thoughts, and motivation than words can. It has almost the same effect as our natural language; it seems to be our native tongue. There are many instances in this essay where music’s impact on our mental processes cannot be denied or overlooked. It is written into our DNA to be affected by music, powered on its emotional energy, and to stimulate our brains in order for us to acquire knowledge and enhance natural mental operations.

Studies have found that music:

– Aids in focus and concentration

– Reduces stress and anxiety

– Helps with memory recall

– Encourages creativity

– Increases productivity

– And even promotes healing.

Music therapy is an ever growing field which uses music as a form of treatment for physical, emotional, mental, and social needs. This type of therapy has been shown to be helpful for those suffering from:

– Alzheimer’s disease and dementia

– chronic pain

– depression

– heart disease

– posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

There is no denying the power of music. It is an integral part of our lives, capable of affecting us on a physical, mental, and emotional level. It has the ability to improve our focus and concentration, reduce stress and anxiety, help with memory recall, encourage creativity, increase productivity, and promote healing. With all of these benefits, it is clear that music is a powerful tool that should not be underestimated.

Music has long been a part of our family’s history, and we’ve employed it as a means of communication before there was even language. Darwin believed that humans first utilized music to attract mates because a peacock flaunts its feathers. Dean Falk of the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Ellen Dissanayake of the University of Washington at Seattle think that music was used to calm babies in addition.

The act of making music activates many different areas of the brain. The auditory cortex is responsible for processing sound, and the motor cortex controls movement. But music also engages the parts of the brain that control emotion, memory, and even social interaction.

Because it engages so many areas of the brain, music has a unique ability to affect our emotions. Studies have shown that music can lower anxiety levels and blood pressure, and it can also help to reduce symptoms of depression. Music therapy is now being used to treat a wide range of mental and physical health conditions, including Alzheimer’s disease, autism, and even cancer.

So there you have it, the power of music is undeniable! It has been part of our history since the beginning, and it continues to have a profound impact on us today. Whether you’re using it to relax, or you’re using it to treat a health condition, there’s no doubt that music can have a real and lasting effect on our lives.

The term “motheresing” refers to this natural process, which is exactly what it sounds like. Just as contemporary moms perform lullabies for their children, primordial humans sang quiet songs to calm them. The method by which mothers motherese are similar in all societies: a softly sung song with a higher than usual tone and tempo. These professionals believe that grown-ups began creating music for their own pleasure after the fundamental elements were established and understood.

In other words, music is older than language. While the date of the first musical performance is lost to history, we do know that music has been an integral part of human culture for tens of thousands of years. The power of music is far-reaching and undeniable. It has the ability to affect our emotions, physiology, and even our behavior.

Numerous studies have shown that music can have a positive effect on the human brain and body. For example, music can:

– Lower blood pressure

– Slow heart rate

– Decrease levels of stress hormones

– Increase production of feel-good chemicals in the brain

– Boost immunity

– Improve sleep quality

– Enhance cognitive functioning and memory

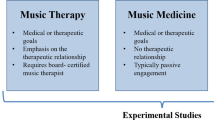

In addition, music therapy is an evidence-based clinical use of music interventions to accomplish individualized goals within a therapeutic relationship by a credentialed professional who has completed an approved music therapy program. Music therapy is an established mental health profession that uses music to address physical, emotional, cognitive, and social needs of individuals of all ages.

To export a reference to this essay please select a referencing style below:

Related essays:

- History of Mental Health by Mind

- Music has been around for thousands and thousands

- Expressive Art Therapy Paper

- Brief History of Art Therapy

- Music Therapy Essay

- Dance Therapy In Schools Essay

- Politcal Stress

- Cognitivebehavioral and Psychodynamic Models for College Counseling

- Overview Of Narrative Therapy Essay

- Emotions And The Self

- The Human Brain Essay Examples

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Preparing your manuscript

- COPE guidelines for peer review

- Fair Editing and Peer Review

- Promoting your article

- About Music Therapy Perspectives

- About the American Music Therapy Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

- Historical Review of Music and Emotion Theories

- Synthesis of Historical Theories

- Understanding Music and Emotions

- Conclusions and Future Directions

- < Previous

Understanding the Influence of Music on Emotions: A Historical Review

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Kimberly Sena Moore, Understanding the Influence of Music on Emotions: A Historical Review, Music Therapy Perspectives , Volume 35, Issue 2, October 2017, Pages 131–143, https://doi.org/10.1093/mtp/miw026

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Music has long been thought to influence human emotions. There is significant interest among researchers and the public in understanding music-induced emotions; in fact, a common motive for engaging with music is its emotion-inducing capabilities ( Juslin & Sloboda, 2010). Traditionally, the influence of music on emotions has been described as dichotomous. The Greeks viewed it as either mimesis , a representation of an external reality, or catharsis , a purification of the soul through an emotional experience ( Cook & Dibben, 2010). This type of dichotomous viewpoint has persisted under various labels, such as formalist versus absolutist, and referential versus expressionist ( Meyer, 1956). However, these perspectives all emerged from musicology. Outside musicology, the scientific study of emotions was intermittent and, until recently, references to music’s effect on emotions were rare ( Sloboda & Juslin, 2010). Since the 1990s, there has been increased interest in studying music-induced emotions, particularly in psychology ( Juslin & Sloboda, 2010). This interest extends to the music therapy profession as well. For example, a professional music therapist in the United States is required to be able to develop and implement music therapy experiences designed to focus on emotion-related treatment goals, such as the ability to empathize, and the client’s overall affect, mood, and emotions ( Certification Board for Music Therapists [CBMT], 2015), and must apply knowledge of music-based emotional responses ( American Music Therapy Association [AMTA], 2013). Given the increased interest in psychology and the clinical implications for the music therapist, it seems timely to analyze and reflect on how the understanding of music-induced emotions has evolved in order to support current and future research and clinical practice. As current understanding is built upon prior knowledge, a historical review can serve to examine previous directions and help inform future study ( Hanson-Abromeit & Davis, 2007). Thus, the purpose of this inquiry was to provide a historical overview of prominent theories of music and emotion and connect them to current understanding. More specifically, the objectives were:

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 2053-7387

- Copyright © 2024 American Music Therapy Association

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Guide on How to Write a Music Essay: Topics and Examples

Let's Understand What is Music Essay

You know how some school assignments are fun to write by default, right? When students see them on the course syllabus, they feel less like a burden and more like a guaranteed pleasure. They are about our interests and hobbies and therefore feel innate and intuitive to write. They are easy to navigate, and interesting topic ideas just pop into your head without much trouble.

Music essays belong to the category of fun essay writing. What is music essay? Anything from in-depth analysis to personal thoughts put into words and then to paper can fall into a music essay category. An essay about music can cover a wide range of topics, including music history, theory, social impact, significance, and musical review. It can be an analytical essay about any music genre, musical instruments, or today's music industry.

Don't get us wrong, you will still need to do extensive research to connect your opinions to a broader context, and you can't step out of academic writing standards, but the essay writing process will be fun.

In this article, our custom essay writing service is going to guide you through every step of writing an excellent music essay. You can draw inspiration from the list of music essay topics that our team prepared, and later on, you will learn what an outstanding essay on music is by an example of a music review essay.

What are Some Music Topics to Write About

There are so many exciting music topics to write about. We would have trouble choosing one. You can write about various music genres, be it country music or classical music; you can research music therapy or how music production happens.

Okay, forgive us for getting carried away; music makes us enthusiastic. Below you will find a list of various music essay topics prepared from our thesis writing service . Choose one and write a memorable essay about everyone's favorite art form.

Music Argumentative Essay Topics

Music essays can be written about an infinite number of themes. You can even write about performance or media comparison.

Here is a list of music argumentative essay topics. These edge-cutting topics will challenge your readers and get you an easy A+.

- Exploring the evolution of modern music styles of the 21st century

- Is it ethical to own and play rare musical instruments?

- Is music therapy an effective mental health treatment?

- Exploring the Intersection of Technology and Creativity in electronic music

- The Relevance of traditional music theory in modern music production

- The Role of musical pieces in the Transmission of cultural identity

- The value of historical analysis in understanding the significance of music in society

- How does exposing listeners to different genres of music break down barriers

- Exploring the cognitive effects of music on human brain development

- The therapeutic potential of music in treating mental disorders

Why is Music Important Essay Topics

Do you know which essay thrills our team the most? The importance of music in life essay. We put our minds together and came up with a list of topics about why music is so central to human life. Start writing why is music important essay, and we guarantee you that you will be surprised by how much fun you had crafting it.

- Popular Music and its Role in shaping cultural trends

- Music as a metaphorical language for expressing emotions and thoughts

- How music changes and influences social and political movements

- How the music of different countries translates their history to outsiders

- The innate connection between music and human beings

- How music helps us understand feelings we have never experienced

- Does music affect our everyday life and the way we think?

- Examining the cross-cultural significance of music in society

- How rock music influenced 70's political ideologies

- How rap music closes gaps between different racial groups in the US

Consider delegating your ' write my essay ' request to our expert writers for crafting a perfect paper on any music topic!

Why I Love Music Essay Topics

We want to know what is music to you, and the best way to tell us is to write a why I love music essay. Below you will find a list of music essay topics that will help you express your love for music.

- I love how certain songs and artists evoke Memories and Emotions

- I love the diversity of music genres and how different styles enrich my love for music

- I love how music connects me with people of different backgrounds

- How the music of Linkin Park helped me through life's toughest challenges

- What does my love for popular music say about me?

- How the unique sounds of string instruments fuel my love for music

- How music provides a temporary Release from the stresses of daily life

- How music motivates me to chase my dreams

- How the raw energy of rock music gets me through my daily life

- Why my favorite song is more than just music to me

Need a Music Essay ASAP?

Our expert team is quick to get you an A+ on all your assignments!

Music Therapy Essay Topics

One of the most interesting topics about music for an essay is music therapy. We are sure you have heard all the stories of how music cures not only mental but also physical pains. Below you can find a list of topics that will help you craft a compelling music therapy essay. And don't forget that you can always rely on our assistance for fulfilling your ' write my paper ' requests!

- The effectiveness of music therapy in reducing stress and pain for cancer patients

- Does pop music have the same effects on music therapy as classical music?

- Exploring the benefits of music therapy with other genres beyond classical music

- The potential of music therapy in aiding substance abuse treatment and recovery

- The Role of music therapy in Addressing PTSD and Trauma in military veterans

- The impact of music therapy on enhancing social interaction and emotional expression in individuals with developmental disabilities

- The use of music therapy in managing chronic pain

- Does musical therapy help depression?

- Does music reduce anxiety levels?

- Is music therapy better than traditional medicine?

History of Music Essay Topics

If you love analytical essays and prefer to see the bigger picture, you can always write a music description essay. Below you can find some of the most interesting topics for the history of music essay.

- The Significance of natural instruments in music production and performance

- Tracing the historical development of Western music theory

- How electronic music traces its roots back to classical music

- How the music industry evolved from sheet music to streaming services

- How modern producers relate to classical composers

- The Origins and Influence of Jazz Music

- How folk music saved the Stories of unnamed heroes

- Do we know what the music of ancient civilizations sounded like?

- Where does your favorite bandstand in the line of music evolve?

- The Influence of African American Music on modern pop culture

Benefits of Music Essay Topics

If you are someone who wonders what are some of the values that music brings to our daily life, you should write the benefits of music essay. The music essay titles below can inspire you to write a captivating essay:

- How music can be used to promote cultural awareness and understanding

- The benefits of music education in promoting creativity and innovation

- The social benefits of participating in music groups

- The Impact of Music on Memory and Learning

- The cognitive benefits of music education in early childhood development

- The effects of music on mood and behavior

- How learning to play an instrument improves cognitive functions.

- How music connects people distanced by thousands of miles

- The benefits of listening to music while exercising

- How music can express the feelings words fail to do so

Music Analysis Essay Example

Reading other people's papers is a great way to scale yours. There are many music essay examples, but the one crafted by our expert writers stands out in every possible way. You can learn what a great thesis statement looks like, how to write an engaging introduction, and what comprehensive body paragraphs should look like.

Click on the sample below to see the music analysis essay example.

How to Write a Music Essay with Steps

Writing music essays is definitely not rocket science, so don't be afraid. It's just like writing any other paper, and a music essay outline looks like any other essay structure.

- Start by choosing a music essay topic. You can use our list above to get inspired. Choose a topic about music that feels more relevant and less researched so you can add brand-new insights. As we discussed, your music essay can be just about anything; it can be a concert report or an analytical paper about the evolution of music.

- Continue by researching the topic. Gather all the relevant materials and information for your essay on music and start taking notes. You can use these notes as building blocks for the paper. Be prepared; even for short essays, you may need to read books and long articles.

- Once you have all the necessary information, the ideas in your head will start to take shape. The next step is to develop a thesis statement out of all the ideas you have in your head. A thesis statement is a must as it informs readers what the entire music essay is about. Don't be afraid to be bold in your statement; new outlooks are always appreciated.

- Next, you'll need a music essay introduction. Here you introduce the readers to the context and background information about the research topic. It should be clear, brief, and engaging. You should set the tone of your essay from the very beginning. Don't forget the introduction is where the thesis statement goes.

- One of the most important parts of essay writing is crafting a central body paragraph about music. This is where you elaborate on your thesis, make main points, and support them with the evidence you gathered beforehand. Remember, your music essay should be well structured and depict a clear picture of your ideas.

- Next, you will need to come up with an ideal closing paragraph. Here you will need to once again revisit the main points in your music essay, restate them in a logical manner and give the readers your final thoughts.

- Don't forget to proofread your college essay. Whether you write a long or short essay on music, there will be grammatical and factual errors. Revise and look through your writing with a critical mind. You may find that some parts need rewriting.

Key Takeaways

Music essays are a pleasure to write and read. There are so many topics and themes to choose from, and if you follow our How to Write a Music Essay guide, you are guaranteed to craft a top-notch essay every time.

Be bold when selecting a subject even when unsure what is research essay topic on music, take the writing process easy, follow the academic standards, and you are good to go. Use our music essay sample to challenge yourself and write a professional paper.

If you feel stuck and have no time our team of expert writers is always ready to give you help from all subject ( medical school personal statement school help ). Visit our website, submit your ' write my research paper ' request and a guaranteed A+ essay will be on your way in just one click.

Need Help in Writing an Impressive Paper?

Our expert writers are here to write a quality paper that will make you the star of your class!

FAQs on Writing a Music Essay

Though music essay writing is not the hardest job on the planet, there are still some questions that often pop up. Now that you have a writing guide and a list of essay topics about music, it's time to address the remaining inquiries. Keep reading to find the answers to the frequently asked questions.

Should Artists' Music be Used in Advertising?

What type of music is best for writing an essay, why do people love music, related articles.

.webp)

Understanding the Influence of Music on People’s Mental Health Through Dynamic Music Engagement Model

- Conference paper

- First Online: 10 March 2023

- Cite this conference paper

- Arpita Bhattacharya 14 ,

- Uba Backonja 14 ,

- Anh Le 14 ,

- Ria Antony 14 ,

- Yujia Si 14 &

- Jin Ha Lee 14

Part of the book series: Lecture Notes in Computer Science ((LNCS,volume 13971))

Included in the following conference series:

- International Conference on Information

1232 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Research shows that music helps people regulate and process emotions to positively impact their mental health, but there is limited research on how to build music systems or services to support this. We investigated how engagement with music can help the listener support their mental health through a case study of the BTS ARMY fandom. We conducted a survey with 1,190 BTS fans asking about the impact BTS’ music has on their mental health and wellbeing. Participants reported that certain songs are appropriate for specific types of mood regulations, attributed largely to lyrics. Reflection, connection, and comfort were the top three experiences listeners shared during and after listening to BTS’ music. External factors like knowledge about the context of a song’s creation or other fans’ reactions to a song also influenced people’s feelings toward the music. Our research suggests an expanded view of music’s impact on mental health beyond a single-modal experience to a dynamic, multi-factored experience that evolves over time within the interconnected ecosystem of the fandom. We present the Dynamic Music Engagement Model which represents the complex, multifaceted, context-dependent nature of how music influences people’s mental health, followed by design suggestions for music information systems and services.

- Music information systems and services

- Mental health

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-southkorea-ferry-idUSKBN0NJ07R20150428 .

https://doolsetbangtan.wordpress.com/2018/06/01/two-three/ .

https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/new-bts-song-2021-worlds-biggest-band-1166441/ .

Arditi, D.: Precarious labor in COVID times: the case of musicians. Fast Capitalism 18 (1), 13–25 (2021)

Article Google Scholar

ARMY Census. https://www.btsarmycensus.com/2022-results . Accessed 8 Sep 2022

Baker, F., Bor, W.: Can music preference indicate mental health status in young people? Australas. Psychiatry 16 (4), 284–288 (2008)

Baker, T.D.: The ghost of “emo:” searching for mental health themes in a popular music format. J. School Counseling 11 (8), 35 (2013)

Google Scholar

Batt-Rawden, K., Tellnes, G.: How music may promote healthy behaviour. Scandinavian J. Public Health 39 (2), 113–120 (2011)

Bennett, L.: Patterns of listening through social media: online fan engagement with the live music experience. Soc. Semiot. 22 (5), 545–557 (2012)

Blady, S.: Bulletproof to Stigma. Speak Up. https://www.speak-up.co/bulletproof-tostigma . Accessed 2 Sep 2022

Chanda, M.L., Levitin, D.J.: The neurochemistry of music. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17 (4), 179–193 (2013)

Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement: Principles of Community Engagement (2011). https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf . Accessed 7 Dec 2022

Davidson, D.: Cross-Media Communications: An Introduction to the Art of Creating Integrated Media Experiences. Carnegie Mellon University (2018). https://doi.org/10.1184/R1/6686735.v1

de la Rubia Ortí, J.E., et al.: Does music therapy improve anxiety and depression in alzheimer’s patients? The J. Alternative and Complementary Medicine 24 (1), 33–36 (2018)

Garringer, J.: How does music connect the artist and fans? Ray Browne Conference on Cultural and Critical Studies (2018). https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/rbc/2018conference/005/7/ . Accessed 8 Sep 2022

Grocke, D., Bloch, S., Castle, D.: Is there a role for music therapy in the care of the severely mentally ill? Australas. Psychiatry 16 , 442–445 (2008)

Gustavson, D.E., Coleman, P.L., Iversen, J.R., Maes, H.H., Gordon, R.L., Lense, M.D.: Mental health and music engagement: review, framework, and guidelines for future studies. Translational Psychiatry 11(1), 370 (2021). https://www.nature.com/articles/s41398-021-01483-8.pdf

Hagen, W.R.: Fandom: Participatory Music Behavior in the Age of Postmodern Media. University of Colorado at Boulder (2010). https://www.proquest.com/docview/507898725

Hill, C., Thompson, B., Williams, E.: A guide to conducting consensual qualitative research. Couns. Psychol. 25 (4), 517–572 (1997)

Hoffner, C.A., Bond, B.J.: Parasocial relationships, social media, & well-being. Current Opinion in Psychology 45 , 101306 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101306

Jenkins, H.: Fan Studies. Oxford Bibliographies (2012). https://doi.org/10.1093/obo/978019 9791286-0027

Jenkins, H.: Convergence Culture. Where Old and New Media Collide. New York University Press, New York, NY (2006)

Knight, W.E.J., Rickard, N.S.: Relaxing music prevents stress-induced increases in subjective anxiety, systolic blood pressure, and heart rate in healthy males and females. J. Music Ther. 38 (4), 254–272 (2008)

Kresovich, A.: The influence of pop songs referencing anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation on college students’ mental health empathy, stigma, and behavioral intentions. Health Commun. 37 (5), 617–627 (2022)

Kresovich, A., Collins, M.K.R., Riffe, D., Carpentier, F.R.D.: A content analysis of mental health discourse in popular rap music. JAMA Pediatr. 175 (3), 286–292 (2021)

Kusuma, A., Putri Purbantina, A., Nahdiyah, V., Khasanah, U.U.: A virtual ethnography study: fandom and social impact in digital era. ETNOSIA: Jurnal Etnografi Indonesia, pp. 238–251 (2020)

Laffan, D.A.: Positive psychosocial outcomes and fanship in K-pop fans: a social identity theory perspective. Psychol. Rep. 124 (5), 2272–2285 (2021)

Lee, J.: BTS and ARMY Culture. CommunicationBooks, Seoul, South Korea (2019)

Lee, J., Thyer, B.A.: Does music therapy improve mental health in adults? a review. J. Hum. Behav. Soc. Environ. 23 (5), 591–603 (2013)

Lee, J.H., Cho, H., Kim, Y.-S.: Users’ music information needs and behaviors: design implications for music information retrieval systems. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 67 (6), 1301–1330 (2016)

Lee, J.H., Nguyen, A.T.: How music fans shape commercial music services: a case study of BTS and ARMY. In: Proceedings of the International Society for Music Information Conference, ISMIR, Montréal, Canada, pp. 837845 (2020)

Lee, J.H., Bhattacharya, A., Antony, R., Santero, N.K., Le, A.: Finding home: understanding how music supports listener’s mental health through a case study of BTS. In: Proceedings of ISMIR, pp. 358–365 (2021)

Lim, D., Benson, A.R.: Expertise and dynamics within crowdsourced musical knowledge curation: a case study of the Genius platform. In: ICWSM, pp. 373–384 (2021)

Lin, S.-T., et al.: Mental health implications of music: insight from neuroscientific and clinical studies. Harv. Rev. Psychiatry 19 (1), 34–46 (2011)

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

MacDonald, R.A.R.: Music, health, and well-being: a review. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being 8 (1), 20635 (2013)

MacDonald, R., Kreutz, G., Mitchell, L.: Music, Health, and Wellbeing. Oxford University Press (2012)

McCaffrey, T., Edwards, J., Fannon, D.: Is there a role for music therapy in the recovery approach in mental health? Arts Psychother. 38 (3), 185–189 (2011)

McFerran, K.S., Garrido, S., Saarikallio, S.A.: Critical interpretive synthesis of the literature linking music and adolescent mental health. Youth & Society 48 (4), 521–538 (2016)

McFerran, K.S., Saarikallio, S.: Depending on music to feel better: being conscious of responsibility when appropriating the power of music. Arts Psychother. 41 (1), 89–97 (2013)

Nilsson, U.: The anxiety- and pain-reducing effects of music interventions: a systematic review. Aorn Journal 87 (4), 780–807 (2008)

Parc, J., Kim, Y.: Analyzing the reasons for the global popularity of BTS: a new approach from a business perspective. J. International Business and Economy 21 (1), 15–36 (2020)

Park, S.Y., Laplante, A., Lee, J.H., Kaneshiro, B.: Tunes together: Perception and experience of collaborative playlists. In: Proceedings of the International Society for Music Information Conference, ISMIR, Delft, The Netherlands (2019)

Park, S.Y., Santero, N., Kaneshiro, B., Lee, J.H.: Armed in ARMY: a case study of how BTS fans successfully collaborated to #MatchAMillion for Black Lives Matter. In: Proceedings of CHI 2021, ACM, New York, NY, USA (2021)

Pereira, C.S., Teixeira, J., Figueiredo, P., Xavier, J., Castro, S.L., Brattico, E.: Music and emotions in the brain: familiarity matters. Public Library of Science 6 (11), e27241 (2011)

Philip, J., Cherian, V.: Psychiatry and ‘pop’ culture: millennials for mental health – psychiatry in music. Br. J. Psychiatry 217 (6), 678 (2020)

Rendell, J.: Staying in, rocking out: online live music portal shows during the coronavirus pandemic. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 27 (4), 1092–1111 (2021)

Reysen, S., Plante, C., Chadborn, D.: Better together: social connections mediate the relationship between fandom and well-being. AASCIT Journal of Health 4 (6), 68–73 (2017)

Ringland, K.E., Bhattacharya, A., Weatherwax, K., Eagle, T., Wolf, C.T.: ARMY’s Magic Shop: understanding the collaborative construction of playful places in online communities. In: Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 1–19 (2022)

Rolvsjord, R., Stige, B.: Concepts of context in music therapy. Nord. J. Music. Ther. 24 (1), 44–66 (2015)

Rubin, S.: Strong experiences with music (SEMs) as experienced by ARMY. https://sydneyrubin.com/2021/03/23/strong-experiences-with-bts-music/ . Accessed 2 Sep 2022

Ruud, E.: Music in therapy: increasing possibilities for action. Music and Arts in Action 1 (1), 46–60 (2008)

Saarikallio, S., Erkkilä, J.: The role of music in adolescents’ mood regulation. Psychol. Music 35 (1), 88–109 (2007)

Scolari, C.: Transmedia storytelling: new ways of communicating in the digital age. AC/E Digital Culture Annual Report. https://www.dosdoce.com/upload/ficheros/noticias/201404/digital_culture_report__english_version.pdf . Accessed 2 Sep 2022

Schedl, M., Flexer, A.: Putting the user in the center of music information retrieval. In: Proceedings of ISMIR pp. 385–390 (2012)

Shutsko, A.: User-generated short video content in social media. a case study of TikTok. In: International Conference on Human Computer-Interaction, pp. 108–125 (2020)

Stratton, V.N., Zalanowski, A.H.: Affective impact of music vs lyrics. Empir. Stud. Arts 12 (2), 173–184 (1994)

Thayer, R.E., Newman, R., McClain, T.M.: Self-regulation of mood: strategies for changing a bad mood, raising energy, and reducing tension. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 67 (5), 910–925 (1994)

Vizcaíno-verdú, A., Abidin, C.: Music challenge memes on TikTok: understanding in-group storytelling videos. Int. J. Commun. 16 , 883–908 (2022)

Yin, R.K.: Case Study Research, Design and Methods. 3rd ed. SAGE (2003)

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 98195, USA

Arpita Bhattacharya, Uba Backonja, Anh Le, Ria Antony, Yujia Si & Jin Ha Lee

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jin Ha Lee .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

iSchool Organization, Berlin, Germany

Isaac Sserwanga

Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand

Anne Goulding

University of Missouri, Chicago, IL, USA

Heather Moulaison-Sandy

University of South Australia, Adelaide, SA, Australia

Jia Tina Du

University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

António Lucas Soares

Monash University, Clayton, VIC, Australia

Viviane Hessami

University of Tennessee at Knoxville, Knoxville, TN, USA

Rebecca D. Frank

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper.

Bhattacharya, A., Backonja, U., Le, A., Antony, R., Si, Y., Lee, J.H. (2023). Understanding the Influence of Music on People’s Mental Health Through Dynamic Music Engagement Model. In: Sserwanga, I., et al. Information for a Better World: Normality, Virtuality, Physicality, Inclusivity. iConference 2023. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 13971. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-28035-1_8

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-28035-1_8

Published : 10 March 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-28034-4

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-28035-1

eBook Packages : Computer Science Computer Science (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Collins Memorial Library

Music 222: music of the world's peoples.

- Getting Started

- Research Questions

- Developing a Thesis

- Writing & Citing

Argumentative Paper Thesis

- Proposed answer to a research question

- Should make a claim and argue it

- Thesis = Topic + a claim (attitude or opinion) + major points (specifics about the points you will use to explain your claim)

- A good thesis has a definable, debatable claim

- Your thesis statement should be specific—it should cover only what you will discuss in your paper and should be supported with specific evidence.

- Your topic may change as you write, so you may need to revise your thesis statement to reflect exactly what you have discussed in the paper.

How to Write a Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is not a statement of fact. It is an assertive statement that states your claims and that you can prove with evidence. It should be the product of research and your own critical thinking. There are different ways and different approaches to write a thesis statement. Here are some steps you can try to create a thesis statement:

1. Start out with the main topic and focus of your essay.

Example: youth gangs + prevention and intervention programs

2. Make a claim or argument in one sentence.

Example: Prevention and intervention programs can stop youth gang activities.

3. Revise the sentence by using specific terms.

Example: Early prevention programs in schools are the most effective way to prevent youth gang involvement.

4. Further revise the sentence to cover the scope of your essay and make a strong statement.

Example: Among various prevention and intervention efforts that have been made to deal with the rapid growth of youth gangs, early school-based prevention programs are the most effective way to prevent youth gang involvement.

Thesis Examples from Published Research

Take a look at the following articles and identify the thesis statement. Why is it an effective or not effective thesis?

1. White, Theresa Renee. “Missy ‘Misdemeanor’ Elliott and Nicki Minaj: Fashionistin' Black Female Sexuality in Hip-Hop Culture—Girl Power or Overpowered?” Journal of Black Studies , vol. 44, no. 6, 2013, pp. 607–626. JSTOR , http://ezproxy.ups.edu/login?url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/24572858 . Accessed 30 Nov. 2020.

2. McNally, James. "Azealia Banks's "212": Black Female Identity and the White Gaze in Contemporary Hip-Hop." Journal of the Society for American Music 10.1 (2016): 54-81. ProQuest, http://ezproxy.ups.edu/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.ups.edu:2443/docview/1882381971?accountid=1627 . Accessed 30 Nov. 2020.

Thesis Statement Tutorial

Good Thesis Tips

- Ensure your thesis is provable. Do not come up with your thesis and then look it up later. The thesis is the end point of your research, not the beginning. You need to use a thesis you can actually back up with evidence.

- First, analyze your primary sources . Look for tension, interest, ambiguity, controversy, and/or complication. Ask questions about the sources.

- Anticipate the counterarguments. Every argument has a counterargument; if yours doesn't, it's not an argument (may be a fact or an opinion). If there are too many arguments against it, find another thesis.

- Communicate a single, overarching point rather than multiple points that may be too difficult or broad to support

Examples of Non-Debatable and Debatable Thesis Statements

Example of a non-debatable thesis statement:

Pollution is bad for the environment.

Example of a debatable thesis statement:

At least 25 percent of the federal budget should be spent on limiting pollution.

The North and South fought the Civil War for many reasons, some of which were the same and some different.

While both Northerners and Southerners believed they fought against tyranny and oppression, Northerners focused on the oppression of slaves while Southerners defended their own right to self-government.

- << Previous: Research Questions

- Next: Books >>

- Last Updated: Mar 15, 2024 11:06 AM

- URL: https://library.pugetsound.edu/music222

- QC Resources

- Music Library

- Open access

- Published: 21 March 2023

Changing positive and negative affects through music experiences: a study with university students

- José Salvador Blasco-Magraner 1 ,

- Gloria Bernabé-Valero 2 ,

- Pablo Marín-Liébana 1 &

- Ana María Botella-Nicolás 1

BMC Psychology volume 11 , Article number: 76 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

9319 Accesses

1 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

Currently, there are few empirical studies that demonstrate the effects of music on specific emotions, especially in the educational context. For this reason, this study was carried out to examine the impact of music to identify affective changes after exposure to three musical stimuli.

The participants were 71 university students engaged in a music education course and none of them were musicians. Changes in the affective state of non-musical student teachers were studied after listening to three pieces of music. An inter-subject repeated measures ANOVA test was carried out using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) to measure their affective state.

The results revealed that: (i) the three musical experiences were beneficial in increasing positive affects and reducing negative affects, with significant differences between the interaction of Music Experiences × Moment (pre-post); (ii) listening to Mahler’s sad fifth symphony reduced more negative affects than the other experimental conditions; (iii) performing the blues had the highest positive effects.

Conclusions

These findings provide applied keys aspects for music education and research, as they show empirical evidence on how music can modify specific affects of personal experience.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

The studies published on the benefits of music have been on the increase in the last two decades [ 1 , 2 , 3 ] and have branched out into different areas of research such as psychology [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ], education [ 1 , 9 , 10 ] and health [ 11 , 12 ] providing ways of using music as a resource for people’s improvement.

The publication in 1996 of the famous report “Education Hides a Treasure” submitted to the UNESCO by the International Commission was an important landmark in the educational field. This report pointed out the four basic pillars of twenty-first century education: learning to know, learning to do, learning to live together, and learning to be [ 13 ]. The two last ones clearly refer to emotional education. This document posed a challenge to Education in terms of both academically and emotionally development at all levels from kindergarten to university. In this regard, there has been a notable increase in the number of studies that have shown the strong impact of music on the emotions in the different stages of education and our lives. For example, from childhood to adolescence, involving primary, secondary and university education, music is especially relevant for its beneficial effects on developing students’ emotional intelligence and prosocial skills [ 1 , 14 ]. In adults, music benefits emotional self-regulation [ 15 ], while in old age it helps to maintain emotional welfare and to experience and express spirituality [ 16 ]. This underlines the importance of providing empirical evidence on the emotional influence of music.

Influence of music on positive affects

Numerous studies have used the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) to evaluate the emotional impact of music [ 17 ]. This scale is valid and effective for measuring the influence of positive and negative effects of music on listeners and performers [ 10 , 18 , 19 ]. Thus, for example, empirical evidence shows that exposure to a musical stimulus favours the increase of positive affects [ 20 , 21 ] found a significant increase in three positive affects in secondary school students after listening to music, and the same results has been found after listening to diverse musical styles. These results are consistent with Schubert [ 22 ], who demonstrated that music seems to improve or maintain well-being by means of positive valence emotions (e. g. happiness, joy and calm). Other research studied extreme metal fans aged between 18 and 34 years old and found statements of physiological excitement together with increased positive affects [ 21 ]. Positive outcomes after listening to sad music have also been found [ 23 ], who played Samuel Barbers’ Adagio for Strings , described by the BBC as the world’s saddest piece of classical music, to 20 advanced music students and 20 advanced psychology students with no musical background and subsequently found that the music only had positive affects on both groups.

Several experimental designs that used sad music on university students noticed that they experienced both sadness and positive affects [ 24 , 25 ] and also found that music labeled as “happy” increased positive affects while the one labeled as “sad” reduced both positive and negative affects [ 26 ]. For other authors the strongest and most pleasant responses to sad music are associated with empathy [ 27 ]. Moreover, listening to sad music had benefits since attributes of empathy were intensified [ 27 , 28 ]. In relation to musical performances, empirical evidence found a significant increase in positive affects [ 29 ]. Thus, music induces listeners to experience positive affects, which could turn music into an instrument for personal development.

Following on from Fredrickson’s ‘broaden‐and‐build’ framework of positive emotions [ 30 ], positive affects cause changes in cognitive activities which, in turn, can cause behaviour changes. They can also expand the possibilities for action and improve physical resources. According to Fredrickson [ 30 ], positive affects trigger three sequential effects: (1) amplification of the scope for thought and action; (2) construction of personal resources to deal with difficult simplifications; (3) personal transformation by making one more creative, with a better understanding of situations, better able to face up to difficulties and better socially integrated. This leads to an “upward spiral” in which even more positive affects are experienced. A resource such as music that can increase positive affects, can therefore be considered as a step forward in personal transformation. Thus, music teachers could have a powerful tool to help students enhance their personal development.

Influence of music on negative affects

There is a great deal of controversy as regards the influence of music on negative affects. Blasco and Calatrava [ 20 ] found a significant reduction of five negative affects in secondary school students after listening to Arturo Marquez’s typically happy Danzón N O 2. Different results were found in an experiment in which the change in participants ‘affects was assessed after listening the happy "Eye of the Tiger" by Survivor and the sad "Everybody Hurts" by REM [ 26 ]. They found that the happy piece only increased the positive affects but did not reduce the negative ones, while the sad piece reduced both positive and negative affects. However, neither of these findings agree with Miller and Au [ 31 ], who carried out an experiment to compare the influence of sad and happy music on undergraduates ‘mood arousal and found that listening to both types had no significant changes on negative affects. Shulte [ 32 ] conducted a study with 30 university students to examine the impact that nostalgic music has on affects, and found that after listening to different songs, negative affects decreased. Matsumoto [ 33 ] found that sad music reduced sad feelings in deeply sad university students, while Vuoskoski and Eerola [ 34 ] showed that sad music could produce changes in memory and emotional judgements related to emotions and that experiencing music-induced sadness is intrinsically more pleasant than sad memories. It therefore seems that reducing negative affects has mostly been studied with sad and nostalgic musical stimuli. In this way, if music can reduce negative affects, it can also be involved in educational and psychological interventions focused on improving the emotional-affective sphere. Thus, for example, one study examined the effects of a wide range of music activities and found that it would be necessary to specify exactly what types of music activity lead to what types of outcomes [ 2 ]. Moore [ 3 ] also found that certain music experiences and characteristics had both desirable and undesirable effects on the neural activation patterns involved in emotion regulation. Furthermore, recent research on university students shows that music could be used to assess mood congruence effects, since these effects are reactions to the emotions evoked by music [ 35 ].

These studies demonstrate that emotional experience can be actively driven by music. Moreover, they synthesize the efforts to find ways in which music can enhance affective emotional experience by increasing positive affects and reducing the negative ones (e. g. hostility, nervousness and irritability). Although negative emotions have a great value for personal development and are necessary for psychological adjustment, coping with them and self-regulation capacities are issues that have concerned psychology. For example, Emotional Intelligence [ 36 ], which has currently been established in the educational field, constitutes a fundamental conceptual framework to increase well-being when facing negative emotions, providing keys for greater control and management of emotional reactions. It also establishes how to decrease the intensity and frequency of negative emotional states [ 37 ], providing techniques such as mindfulness meditation that have proven their effectiveness in reducing negative emotional experiences and increasing the positive ones [ 38 ]. The purpose of this research is to find whether music can be part of the varied set of resources that can be used by a teacher to modify students’ emotional experience.

Thus, although empirical evidence of the effects of music on the emotional sphere is still incipient. It seems that they can increase positive effects, but it is not clear their impact on the negative ones, since diverse and contradictory results (no change and reduction of negative affects after listening to music) were found. In addition, the effects of the type of musical piece (e.g. happy or sad music) need further investigation as different effects were found. Moreover, previous studies do not compare between the effects of listening to versus performing music. Such an approach could provide keys to highlight the importance of performing within music education. Therefore, this study aims to contribute to this scientific field, providing experimental evidence on the effects of listening to music as compared to performing music, as well as determining the effects of different types of music on positive and negative affects.

To this end, the effects of three different types of music experiences were compared: (1) listening to a sad piece, (2) listening to an epic and solemn piece, and (3) performing of a rhythm and a blues piece, to determine whether positive and negative affects were modified after exposure to these experimental situations. In particular, two hypotheses guided this study: (1) After exposure to each musical experience (listening to a sad piece; listening to a solemn piece and playing a blues), all participants will improve their emotional experience, increasing their positive affects and reducing their negative ones; and (2) the music performance will induce a greater change as compared to the listening conditions.

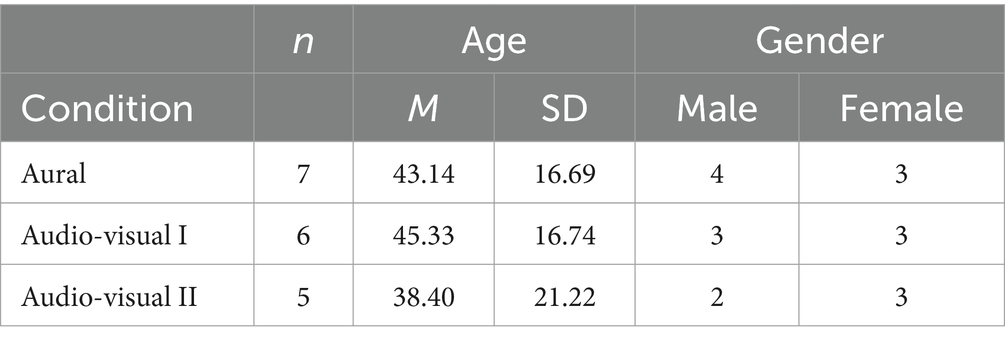

Participants

A total of 71 students were involved in this study, 6 men and 65 women between the ages of 20 and 40, who were studying a Teaching Grade. These students were enrolled in the "Music Education" program as part of their university degree’s syllabus. None of them had special music studies from conservatories, academies or were self-taught; thus, all had similar musical knowledge. None of them had previously listened to music in an instructional context nor had performed music with their fellow students. In addition, none of them had listening before to the musical pieces selected for this experiment.

All signed an informed consent form before participating and no payment was given for taking part in the study. As the experiment was carried out in the context of a university course, they were assured that their participation and responses would be anonymous and would have no impact on their qualifications. The research was approved by the ethical committee at the Universidad Católica de Valencia San Vicente Mártir: UCV2017- 18-28 code.

Questionnaire

To assess emotional states, the Positive and Negative Affective States scales (PANAS), was administered [ 39 ]. In particular, the Spanish version of the scale [ 17 ], whose study shows a high degree of internal consistency; in males 0.89 in positive affects and 0.91 in negative affects; in women 0.87 in positive affects and 0.89 in negative affects. In this study, good reliability level in each experimental condition was obtained (0.836–0.913 for positive affects and 0.805–0.917 for negative affects (see Table 1 for more information on Cronbach’s α for each experimental condition).

The PANAS consists of 20 items which describe different dimensions of emotional experience. Participants must answer them regarding to their current affective state. The scale is composed of 20 items; 10 positive affects (PA) and 10 negative affects (NA). Answers are graded in a 5-options (Likert scale), with reversed items, ranging from extremely (1) to very slightly or not at all (5).

Musical pieces

The musical pieces choice stemmed from the analysis of some of the music elements that most influence the perception of emotions: mode, melody and intervals. Within the melody, range and melodic direction were distinguished. The range or amplitude of the melodic line is commonly divided into wide or narrow, while the melodic direction is often classified as ascending or descending. Chang and Hoffman [ 10 ] associated narrow amplitude melodies with sadness, while Schimmark and Grob [ 40 ] related melodic amplitude with highly activated emotions. Regarding the melodic direction, Gerardi and Gerken [ 41 ] found a relationship between ascending direction and happiness and heroism, and between descending direction and sadness.

In relation to the mode, Tizón [ 42 ] stated that the major one is completely happy, while the minor one represents sadness. Thompson and Robitaille [ 43 ] considered that, in order to cause emotions such as happiness, solemnity or joy, composers use tonal melodies, while to obtain negative emotions, they use atonality and chromaticism.

In this research, the selected pieces (“Adagietto” from Gustav Mahler's Fifth Symphony, MML; and “Titans” from Alexander The Great from Vangelis, VML) are representative examples of the melodic, intervallic and modal characteristics previously exposed. Mahler's and Vangelis's pieces completely differ in modes and melodic amplitude (sad vs. heroism). Likewise, Mahler's piece is much more chromatic than Vangelis' one, which has a broader melody made up of third, fourth and fifth intervals, often representative of heroism. Those features justify the fact that they have been used as soundtracks in two films belonging to the epic genre (Alexander The Great, 2004) and drama (Death in Venice, 1971).

The musical piece that was performed by the students was chosen in order to be easy to learn in a few sessions, since they were not musicians. So, three musical pieces were used for the experimental conditions, the first two musical pieces were recordings in a CD, while the third one was performed by the subjects.

The three chosen pieces are described below:

Condition 1 (MML): “Adagietto” from Gustav Mahler’s Fifth Symphony (9:01 min), performed by the Berlin Philharmonic conducted by Claudio Abbado [ 44 ]. This is a sad, melancholic and dramatic piece that Luchino Visconti used in the film Death in Venice, made in 1971 and based on the book by Thomas Mann.

Condition 2 (VML): “Titans Theme” from Alexander the Great (3:59 min), directed by Oliver Stone and premiered in 2004, whose music was composed, produced and performed by Vangelis [ 45 ]. It has a markedly epic character with large doses of heroism and solemnity.

Condition 3 (BP): “Rhythm’s Blues” composed and played by Ana Bort (4:00 min). This is a popular African-American piece of music with an insistent rhythm and harmonically sustained by tonal degrees. This piece was performed by the participants using percussion instruments (carillons and a range of xylophones and metallophones).

The sample was divided into two groups (N 1 = 36 and N 2 = 35) that participated separately in all the phases of the study. The first two conditions (MML and VML) were carried out in each group's classroom, while the performance (BP) was developed in the musical instruments room. This room had 52 percussion instruments, including different types of chimes, xylophones and metallophones (soprano, alto and bass). It is a large space where there are only chairs and musical instruments and stands. The first group was distributed as follows: 6 chimes (3 soprano and 3 alto), 5 soprano xylophones, 5 alto xylophones, 5 bass xylophones, 5 soprano metallophones, 5 alto metallophones and 5 bass metallophones. The distribution of the second group was similar, but with one less alto metallophone.

Prior to the experiment, participants received two practical lessons in order to learn how to collectively perform the music score (third experimental condition). After the two practical lessons, during the next three sessions (leaving two weeks between each session), the experiment was carried out. In each session, an experimental condition was applied and PANAS was on-line administered online beforehand and afterwards (Pre-Post design). All participants were exposed to the three experimental conditions and completed the scale before and after listening to music.

In each of these three sessions, a different music condition was applied: MML in the first one, VML in the second one and BP in the third one.

As conditions VML and MML were listening to pieces of music, the instructions received by the subjects were: “You are going to listen to a musical piece, you ought to listen actively, avoiding distractions. You can close your eyes if you feel like to”. For the BP condition, they were said to play the musical sheet all together.

The aim of the study was to examine the effect of the music experience variable (with three levels: MML, VML and BP) in the Positive and Negative Affects subscales from the PANAS scale. The variable Moment was also studied to control biases and to analyze differences between the Pre and Post conditions.

The experiment was designed as a two-way repeated measure (RM) ANOVA with two dependent variables: Positive Affects and Negative Affects, one for each PANAS’ subscales.

The two repeated measures used in the experiment were the variables Musical Experience (ME), with three levels (MML, VML and BP) and the variable Moment, with two levels (PRE and POST). All participants were exposed to the three experimental conditions.

The design did not include a control group, similar to many other studies in the field of music psychology [ 27 , 30 ]. The control was carried out from the intra-subject pre-post measurement of all the participants. The rationale for this design lies in the complexity of the control condition (or placebo) design in psychology [ 46 ]. While placebos in pharmacological trials are sugar pills, in psychology it is difficult to establish an equivalent period of time similar to the musical pieces (e. g. 9 min) without activity, so that cognitive activity occurred during this period of time (e. g. daydreaming, reading a story, etc.) could bias and limit the generalization of results.

Additionally, one of the goals of this study was to compare the effects of listening to music compared to performance on affects. For this reason, two music listening experiences (MML and VML) and a musical performance experience (BP) were designed. In order to control potential biases, participants did not know the musical pieces in the experimental conditions and they had a low level of musical performance competence (musicians were excluded).

It was used SPSS statistics v.26 for the statistical analyzes.

Two ANOVA were performed. The first one, analyzed two dependent variables at the same time: Positive Affects (PA) and Negative Affects (NA).

In the second ANOVA, the 20 items of the PANAS scale were taken as dependent variables. The rest of the experimental design was similar to the first one, a two-way RM ANOVA with variables Musical Experience (ME) and Moment as repeated measures.

Examination of frequency distributions, histograms, and tests of homogeneity of variance and normality for the criterion measures indicated that the assumptions for the use of parametric statistics were met. Normality was met in all tests except for one, but the ANOVA is robust against this assumption violation. All the analyses presented were performed with the significance level (alpha) set at 0.05, two-tailed tests. Means and standard deviations for the 6 experimental conditions for both subscales, Positive Affects and Negative Affects, are presented in Table 1 .

Mauchly’s test of sphericity was statistically significant for Musical Experience and Musical Experience*Moment focusing on NA as the dependent variable ( p < 0.05). The test only was significant for Musical Experience for PA as dependent variable ( p < 0.05). The rest of the W’s Mauchly were not significant ( p > 0.05), so we assumed sphericity for the non-mentioned variables and worked with the assumed sphericity univariate solution. For the variables which the W’s Mauchly was significant, the univariate solution was also taken, but choosing the corrected Greenhouse–Geisser epsilon approximation due to its conservativeness.

A significant principal effect of the Musical Experience variable F(1.710,119.691) = 22.505, p < 0.05, η 2 = 0.243; the Moment variable F(1,70) = 45.291, p < 0.05, η 2 = 0.393; and the Musical Experience*Moment interaction F(2,140) = 32.502, p < 0.05, η 2 = 0.317 were found for PA.

Statistically significance was found for Moment F(1, 70) = 70.729, p < 0.05, η 2 = 0.503 and Musical Experience*Moment interaction F(1.822, 127.555) = 8.594, p < 0.05, η 2 = 0.109, but not for Musical Experience F(1.593, 111.540) = 2.713, p < 0.05, η 2 = 0.037, for the other dependent variable, NA.

Table 2 shows pairwise comparisons between Musical Experience levels. Bonferroni’s correction was applied in order to control type I error. We only interpret the results for the Positive Affects because the Musical Experience effect was not statistically significant for Negative Affects. Results show that condition VML presents a significant higher punctuation in Positive Affects than the other two conditions ( p < 0.05). It also shows that the musical condition MML is significantly above BP in Positive Affects ( p < 0.05).

As regards Moment variable (Table 3 ), all but one Pre-Post differences were statistically significant ( p < 0.05) for all the three conditions for both Positive and Negative Affects dependent variables. The Pre-Post difference found in Positive Affects for the VML Musical Experience did not reach the statistical level ( p = 0.319).

Focusing on these statistically significant differences, we observe that conditions MML and BP, for PA, decreased from Pre to Post condition, indicating that positive emotions increased significantly between pre and post measures. On the other hand, for NA, all conditions increased from Pre to Post conditions, indicating that negative affects were decreased between pre and post conditions. Once again, one should bear in mind that items were reversed, thus, a higher scores in NA means a decrease in affects.

In order to measure the interaction effect, significant differences between simple effects were analysed.

The simple effect of Moment (level2-level1) in the first Music Experience condition (MML) in PA was compared with the simple effect of Moment (level2-level1) in the second Musical Experience condition (VML). Music Experience conditions 2–3 (VML-BP) and 1–3 (MML-BP) were compared in the same way. Thus, taking into account PA and NA variables, a total of 6 comparisons, 3 per dependent variable, were made.

The results of these comparisons are shown in Table 4 . Comparisons for PA range from T1 to T3 and comparisons for NA range from T4 to T6. All of them are significant ( p < 0.05) which means that there are statistically significant differences between all the Musical Experience conditions when comparing the Moment (pre/post) simple effects.

In Table 5 , we can look at the differences’ values. As we said before the differences between Pre and Post conditions are significant when comparing the three musical conditions. The biggest difference for positive affects is between MML and BP (T3 = 8.443), and between VML and MML (T4 = − 6.887) for negative affects.

In this second part, the results obtained from the second two-way RM ANOVA with the 20 items as dependent variables are considered. Results of the descriptive analysis of each item: Interested, Excited, Strong, Enthusiastic, Proud, Alert, Inspired, Determined, Attentive, Active, Distressed, Upset, Guilty, Afraid, Hostile, Irritable, Ashamed, Nervous, Jittery, Scared ; in each musical condition: MML, VML and BP; and for the PRE and POST measurements, can be found in the Additional file 1 (Appendix A).

As regards the ANOVA test that compares the three experimental conditions in each mood, Mauchly’s Sphericity Test indicates that sphericity cannot be assumed for the musical experience in most of the variables of the items of effects, except for Interested, Alert, Inspired, Active and Irritable . For these items, the highest observed power index among Greenhouse–Geisser, Huynh–Feldt and Lower-bound epsilon corrections was taken for each variable. For the interaction Musical Experience*Moment, sphericity was not assumed for Distressed, Guilty, Hostile and Scared . For these items, the same above-cited criterion was followed.

Musical experience has a principal effect on all the positive affects, but only has it for 5 negative affects ( Nervous, Jittery, Scared, Hostile and Upset ) ( p < 0.05). For more detail see Table S1 from Additional file 1 : Appendix B.

The principal effect of Moment is also statistically significant ( p < 0.05) for all (positive and negative), but two items: Guilty ( p = 0.073) and Hostile ( p = 0.123). All the differences between Pre and Post for positive affects are positive, which means that scores in conditions Pre were significantly higher than in condition Post. The other way around occurs for negative affects, all the differences Pre-Post are negative, meaning that the Post condition is significantly higher than the Pre condition. For more detail, see Table S2 from Additional file 1 : Appendix B. In this way, Pre-post changes (Moment) improve affective states; the positive affects increase while the negative are reduced, except for Guilty ( p = 0.073) and Hostile ( p = 0.123).

Comparing the proportion of variance explained by the musical experienced and Moment (Tables s1 and s2 from the Additional file 1 : Appendix B), it is observed that most of the η 2 scores in musical experience are below 0.170, except Active and Alert , which are higher. On the other hand, the η 2 scores for Moment are close to 0.300. From these results we can state that, taking only one of the variables at a time, the proportion of the dependent variable’s variance explained by Moment is higher than the proportion of the dependent variable’s variance explained by Musical Experience.

The effect of interaction, shown in Table S3 from the Additional file 1 : Appendix B is significant in 7 positive moods ( Interested, Excited, Enthusiastic, Alert, Determined, Active and Proud ) and 4 negative moods ( Hostile , Irritable, Nervous , and Jittery ).

The pairwise comparisons of Musical Experience’s levels show a wide variety of patterns. Looking at Positive Affects, there is only one item ( Active ) which present significant differences between the three musical conditions. Items Concentrated and Decided do not present any significant difference between any musical conditions. The rest of the Positive items show at least one significant difference between conditions VML and BP. All differences are positive when comparing VML-MML, VML-BP MML-BP, except for Alert and Proud. So, in general, scores are higher for the first two conditions in relation to the third one, meaning that third musical condition presents the biggest increase for Positive Affects (remember items where reversed). For more detail see Additional file 1 : Appendix C.

As regard pairwise comparisons of Musical Experience’s for negative affects, only the items which had a significant principal effect of the variable Musical Experience are shown here. There is a significant difference between conditions VML and MML in item Nervous ; between VML and BP for Scared ( p < 0.05). For Jittery ; all three conditions differed significantly from each other ( p < 0.05). Conditions MML and BP differed significantly for Hostile ( p < 0.05) and conditions VML and BP almost differed significantly for Upset item, but null hypothesis cannot be rejected as p = 0.056. For more detail see Additional file 1 : Appendix C. All differences were negative when comparing VML-MML, VML-BP MML-BP, except for Nervous and Jittery . So, in general, scores are lower for the first and second condition in relation to the third one.

Positive effects increased significantly during the post phase of all the music experiences, showing that exposure to any of the three music stimuli improved positive affectivity. There were also significant differences between the three experiences in this phase, according to the following order of improvements in positive affectivity: (1) the rhythm and blues performance (BP), (2) listening to Mahler (MML) and (3) listening to Vangelis (VML). As regards the effects of the musical experience x Moment interaction , all the comparisons were significant, with bigger differences in the interpretation of the blues (BP) than in listening to Mahler (MML) and Vangelis (VML). However, the comparison between both experiences, although significant, was smaller. These results indicate that performing music is significantly effective in increasing positive effects. We will explain these results in greater detail below as regards the specific affective states.

As regards Negative Affects, the comparison of the simple effects showed that these decreased after the musical experiences, although in this first analysis the VML musical experience did not differ from the other two. However, the results of the effects of the interaction between musical experiencie x Moment showed that all the comparisons were significant, with a larger difference between MML and VML than the one between BP and each of the other experiences. Listening to Mahler (MML) was more effective in reducing negative affects, compared to both listening to Vangelis and interpreting the blues (BP). These results agree with previous studies [ 26 , 32 ], in which listening to sad music helped to reduce negative affectivity. In this study, it was the most effective condition, although exposure to all three musical experiences reduced negative affects.

The analysis of the specific affective states shows that most items that belong to Positive Affect scale are the most sensitive ones to the PRE-POST change, the different musical conditions and the interpretation of both effects. However, some items of the Negative Affect scale did not differ in the different music conditions or in the music experience × Moment interaction . For example, there were two items (Guilty and Hostile) that did not obtain significance. These results are consistent with the fact that music has certain limits as regards its impact on people’s affects and does not influence all equally. For example, Guilty has profound psychological implications that cannot be affected by simple exposure to certain musical experiences. This means we should be cautious in inferring that music alone can have therapeutical effects on complex emotional states whose treatment should include empirically validated methods. Also, emotional experiences are widely diverse so that any instrument used to measure them is limited as regards the affective/emotional state under study. These results suggest the importance of reviewing the items that compose the PANAS scale in musical studies to adapt it in order to include affective states more sensitive to musical experiences and eliminate the least relevant items.

The analysis of the results in the specific affective states, allows us to delve deeper into each experimental condition. Thus, regarding the results obtained in the complete scale of PANAS, listening to Mahler (MML), causes desirable changes by raising two positive affects ( Inspired and Attentive ) and reducing 10 negative affects ( Distressed, Upset, Afraid, Hostile, Irritable, Ashamed, Nervous, Jittery, and Scared ). This shows that this music condition had a greater effect on the negative affects than the other ones. These results agree with previous studies [ 26 , 32 ], which found that sad music could effectively reduce negative affects, although other studies came to the opposite conclusion. For instance, Miller and Au [ 31 ] found that sad music did not significantly change negative affects. Some authors [ 47 , 48 ] have argued that adults prefer to listen to sad music to regulate their feelings after a negative psychological experience in order to feel better. Taruffi and Koelsch [ 49 ] concluded that sad music could induce listeners to a wide range of positive effects, after a study with 772 participants. In order to contribute to this debate. It would be interesting to control personality variables that might explain these differences on the specific emotions evoked by sad music. In this study, it has been shown that a sad piece of music can be more effective in reducing negative affects than in increasing positive ones. Although the results come from undergraduate students, similar outcomes could be obtained from children and adolescents, although further research is required. In fact, Borella et al. [ 50 ] studied the influence of age on the effects of music and found that the emotional effects influenced cognitive performance (working memory) in such a way that the type of music (Mozart vs. Albinoni) had a stronger influence on young people than on adults. Kawakami and Hatahira [ 28 ], in a study on 84 primary schoolchildren, also found that exposure to sad music pleased them and their level of empathy correlated with their taste for sad music.

Listening to Vangelis (VML) increased 3 positive affects ( Excited, Inspired and Attentive ) and reduced 8 negative affects ( Distressed, Upset, Afraid, Irritable, Ashamed, Nervous, Jittery , and Scared ). Surprisingly, two positive affects were reduced in this experimental condition ( Alert and Attentive ). It could be explained due to the characteristic ostinato rhythm of this piece of music. It was found a similar effect in the study by Campbell et al., [ 26 ] in which sad music reduced both positive and negative affects. This musical condition also managed to modify negative affects more than positive ones.