Importance of Ethics in Communication Essay

Introduction, what is communication ethics, how can one observe ethics in communication, unethical communication, importance of ethics in communication.

In any organization, the workplace needs to be run in such a way that every person feels part of the organization. On many occasions, decisions are made by the leaders and supervisors, leaving the subordinates as mere observers. Self-initiative is crucial in solving some of the problems that arise and as such, every employee is expected to possess self initiative.

Communication ethics is an integral part of the decision making process in an organization. Employees need to be trained on the importance of ethics in decision making so as to get rid of the blame game factor when wrong choices are made. The working place has changed and the employees have become more independent in the decision making process.

The issue that arises is whether employees make the right decision that would benefit the company or they make the wrong choices that call for the downfall of the company. Some organizations have called for the establishment of an ethics program that can aid and empower employees so that unethical actions would be intolerable. This is because occasionally, bad decisions destroy organizations making the whole decision making process unethical.

Some programs on good ethics can help in guiding the employees in the process of decision making. This would ensure the smooth running of organizations and instances of unethical decision making would be null. An ethical decision making process is important in ensuring that the decisions made by the employees are beneficial to organization welfare and operations.

Ethical communication is prudent in both the society and the organizations. The society can remain functional if every person acted in a way that defines and satisfies who they are. However, this could be short lived because of the high probability of making unethical decisions and consequently, a chaotic society. For this reason, it would be of essence to make ethical rules based on a set guidelines and principles.

Ethical communications is defined by ethical behavioral principles that include honesty, concern on counterparts, fairness, and integrity. This cannot be achieved if everyone acted in isolation. The action would not be of any good to most people. Adler and Elmhorst (12) note that actions should be based on the professional ethics where other professionals have to agree that the actions in question are ethical and standard. If a behavior is standard there is nothing to fear if exposed to the media.

However, unethical behavior can taint the reputation of an organization. An action needs to do good to most people in the long run. Adler and Elmhorst (12) note that this golden rule needs to be applicable in organizations. Failure to do this, it becomes an obstacle to this principle.

In achieving the ideals, several obstacles are bound to arise in the process of decision making. Rationalizations often distract individuals involved in making tough decisions. According to the Josephson Institute of ethics (2002) the false assumption that people hold on to that necessity leads to propriety can be judgmental that unethical tasks are part of the moral imperative.

For example, assuming that a particular action is necessary and it lies in the ethical domain is a mere assumption that can be suicidal to an organization. This necessity assumption often leads to a false necessity trap that prompts individuals to take actions without putting into account the cost of doing or failing to do the right thing (Josephson Institute of ethics, Para 5). As part of a routine job, it is likely to be an obstacle in the sense that an individual is doing what he/she got to do.

For example, morality of professional behavior is often neglected at the workplace and on most occasions, people do what they feel is justifiable although it is morally wrong even if not in that context. Individuals often assume that if everyone is doing a certain action, then it is ethical. However, this is not the right way to go as the accountability of individuals and their behaviors should not be treated as a norm in the organization. For example, we could assume that everyone tells lies in an organization.

This assumption is uncertain because lying is unethical and can hinder the achievement of certain goals in an organizational. It may not bring harm at the given time but in the long run it may be chaotic. An observation by the Josephson Institute of Ethics (para 9) is that false rationalization is just an excuse to commit unethical conduct. Basically, the assumption that an action would not harm somebody or the organization does not give the limelight to committing unethical deeds.

The management of an organization should make the ethics of their employees their concern and business. The assumption that employees can make ethical decisions without advising them on what is ethical and then blaming the employees in case the plan backfires is unethical. In ensuring that the actions carried by employees are ethical, the human resource management should set up ethical programs within the organization.

As noted by Flynn (30) the principles of ethical behavior are bound to develop if an organization itself practices acts of ethics. For example, honesty, fairness, concern for others, morality and truthfulness can be achieved if code of ethical conduct is practiced in organization. In achieving an ethical decision some steps need to be followed. Decisions making should be ethical and objective to the organization and its components.

According to Flynn (37) the rules of the Texas instrument company noted that the legality of an action is of imperative importance. If for example an action is illegal then the law should not be broken because an action has to be taken. Instead, the executioner of the action needs to stop right away. Actions need to comply with the values of an organization. If the actions cannot comply with the set organizational values then the action may not fit well.

An action carried should not make someone feel bad or the actions carried should not be harmful to the executioner. The public image of an action in the newspaper or media should be considerate. An action should be within a given timeframe and be done even if its appearance will affect it. For an action that one is not sure, they are obligated to ask and if not satisfied they continue asking until an answer is got (Flynn 37).

Communication ethics is important in the operation of an organization. The way in which decision making is carried in an organization determines the outcome. Ethical decision making process is necessary in an organization. Some of the obstacles that restrict rationalization are merely based on assumptions. They lead to downfall or negative ramifications that affect the organizations. Organizational managers are advised to take decision making of employees as their own concern.

Legitimacy of actions is important and so are the values, because some actions maybe illegal or values fail to meet the organizational values. This may have negative impact if they are not illegal or in line with organizational goals. In general, ethical decision making process is important as it saves a company from the problems it would face for its unethical actions

Works Cited

Adler, Ronald B. and Jeanne Marquardt Elmhorst. Communicating at Work . 9 th ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2008. Print.

Flynn, Gillian. “Make Employee Ethics Your Business.” Personnel Journal ( 1995) 74.6: 30-37. Web.

Josephson Institute of Ethics. “Making Ethical Decisions—Part Five: Obstacles to Ethical Decision Making.” Accounting Web (2002 ). Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, October 28). Importance of Ethics in Communication Essay. https://ivypanda.com/essays/communication-ethics/

"Importance of Ethics in Communication Essay." IvyPanda , 28 Oct. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/communication-ethics/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Importance of Ethics in Communication Essay'. 28 October.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Importance of Ethics in Communication Essay." October 28, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/communication-ethics/.

1. IvyPanda . "Importance of Ethics in Communication Essay." October 28, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/communication-ethics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Importance of Ethics in Communication Essay." October 28, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/communication-ethics/.

- Unethical Workplace Behavior: How to Address It

- Business Ethics of Negotiation

- Business Ethics Theories and Unethical Actions Punishment

- Extreme Working Conditions

- Business Ethics: Reflective Essay

- Ethics Program: Hyatt Hotels Corporation Code of Ethics

- Corporate Ethical Challenges

- Value and Ethics in Organizations

Together, We Succeed.

The importance of communication ethics.

Brown University describes ethics as “a set of standards for behavior that helps us decide how we ought to act in a range of situations.” But it’s more than just right and wrong, because hard decisions are not always so clear, and knowing how to make them is an important next step. The communication professional must carry both the understanding of ethical principles and the strict adherence to these values, as well as the ability to adhere to them through media literacy, research, fact-checking, and analytical skills. It’s two-fold: they must have both understanding and ability.

Building ethical understanding for communication professionals

Communication professionals who have thought about potential decisions they might have to make and hold true to their own codes of ethics are more likely to know what to do when faced with these decisions. Courses in Communication ethics, like the one all Communication students take at Saint Vincent, are crucial to help future communication professionals, journalists, PR professionals, and more navigate complex situations with these principles in mind.

Professional communicators are often faced with complicated decisions surrounding the ethics of their work. Decisions surrounding the credibility of sources. Decisions surrounding divulging certain names, or the language used in speaking about people. In business communication, communicators must achieve their company’s financial goals without sacrificing truth, accuracy, others’ privacy, and other obligations. These are just a few of the many examples.

The Society of Professional Journalists’ Code of Ethics declares four principles as the “foundation of ethical journalism and encourages their use in its practice by all people in all media.”

- First, Seek Truth and Report it.

- Second, Minimize harm

- Third, Act Independently

- Be Accountable and Transparent

Because of the fast-paced nature of communication today, and its ability to spread quickly to places outside of one’s control, it is crucial that professional communicators adhere to these specific rules around accuracy, truth, respect, and more. Ethical communication is delivering your message in a way that is “clear, concise, truthful and responsible.”

Developing the concrete skills to becoming an ethical communicator

The reality is that it is easy to become a published communicator, but it is a challenge to do so with a strong tie to these principles. How do you truly adhere to principles of accuracy and clarity? You learn how to become a strong writer, you learn how to tell the difference between solid research and accurate sources and something less reliable, and how to check every fact. That is why, in addition to understanding the ethical principles surrounding ethical decision-making, communication professionals must truly understand the work that goes into accurate reporting. Courses like CA 201 Communication Research Methods and CA 230 Writing for Media among others at Saint Vincent work to build these skills so that communication graduates become responsible professionals able to take on the challenges this field faces every day.

No related posts.

Categories:

- Media, Communications & Publishing

Recent Posts

- Introducing Saint Vincent College’s new birdfeeder webcam: what’s its purpose?

- How business data analytics is transforming healthcare

- Saint Vincent’s Participation in the 2022 Great Backyard Bird Count

- 4 Pre-med tips for staying on track

- Rounding out communication skills with animation, graphics, and media

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- February 2021

- September 2020

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- February 2017

- January 2017

- Benedictine Leadership

- Criminology & Forensic Studies

- Data Science & Analytics

- Early Childhood Education

- Engineering

- Integrated STEM

- Medicine & Biotechnology

- Ornithology

- Study Abroad

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Communication and Culture

- Communication and Social Change

- Communication and Technology

- Communication Theory

- Critical/Cultural Studies

- Gender (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Studies)

- Health and Risk Communication

- Intergroup Communication

- International/Global Communication

- Interpersonal Communication

- Journalism Studies

- Language and Social Interaction

- Mass Communication

- Media and Communication Policy

- Organizational Communication

- Political Communication

- Rhetorical Theory

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Communication ethics.

- Lisbeth A. Lipari Lisbeth A. Lipari Department of Communication, Denison University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.58

- Published online: 27 February 2017

Communication ethics concerns the creation and evaluation of goodness in all aspects and manifestations of communicative interaction. Because both communication and ethics are tacitly or explicitly inherent in all human interactions, everyday life is fraught with intentional and unintentional ethical questions—from reaching for a cup of coffee to speaking critically in a public meeting. Thus ethical questions infuse all areas of the discipline, including rhetoric, media studies, intercultural/international communication, relational and organization communication, as well as other iterations of the field.

- moral reasoning

- normativity

- communication and critical studies

Introduction

Broadly conceived, ethics concerns the creation and evaluation of goodness, or “the good,” by responding to the general question: How shall we live ? What makes any given decision good or right or wrong? Is it ethically good for governments to persuade poor people to fight, and perhaps die, in wars that disproportionately benefit the wealthy? Is it an ethical good for society to provide access to free and quality education to all children? Are politicians obligated to tell the truth to their constituents regardless of the consequence? By wrestling with the ancient human question of what is good , ethicists disclose the inherently social and political nature of communicative phenomenon—whether they are linked to laws, morals, values, and customs and whether they vary from region to region or culture to culture. The word ethics itself comes from the Greek word ethikos , which means habit or custom, whereas the word moral comes from the Latin translation of the Greek word ethikos . Ethics govern and yet are distinct from law. That is, while laws encode values and customs that will be enforced by the power of the state, more generally ethics concern those values and beliefs (whether enforced by law or not) that a society or group or individual believe will most likely create goodness. But as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and others have famously said, one has a moral obligation to disobey unjust laws. And the questions of what makes a law or action just or unjust, who gets to deliberate, and how we decide are some of the central questions of communication ethics.

In the field of communication ethics , scholars draw upon a variety of ethical theories to address questions pertaining to goodness involving all manifestations of communicative interaction. And because both communication and ethics are tacitly or explicitly inherent in all human interactions, everyday life is fraught with intentional and unintentional ethical questions—from reaching for a cup of coffee to speaking up in a public meeting. Thus, ethical questions infuse all areas of the discipline of communication, including rhetoric, media studies, intercultural/international communication, relational and organization communication, and all other iterations of the discipline. Some scholars specialize in communication ethics as a subfield of communication studies with applications to all aspects of the field, while others work more theoretically in search of philosophical inquiry and understanding. After a brief introduction to the history of the field, this article sketches three central characteristics that shape contours of communication ethics scholarship—heterogeneity, interconnectivity, and historicity—and then goes on to follow three central concerns of communication ethics scholarship—integrity, power, and alterity. A brief overview of five modes of ethical reasoning will close the article.

Brief History of the Discipline

Some scholars trace the origins of communication ethics to American public education in the early 1900s, when questions about “speech hygiene” drove researchers to examine the role of education in fostering qualities of moral character and “mental health” in students (Arnett, 1987 ; Gehrke, 2009 ). Scholarship in subsequent decades came to emphasize speech education as a means to prepare citizens for participation, as both speakers and listeners, in democracy, and particularly as a way to resist fascist oratory. Developed at a time when access to education and the democratic process was shifting from elites to the masses, these scholars focused on speech education as a means to develop moral excellence in psychological, cognitive, and communicative terms they traced to the classical canon of rhetoric, such as the great Roman teacher/scholar Quintilian’s definition of rhetoric as “the good man speaking well” (Quintilian, 2006 ). Postwar decades in the United States brought increasing attention to questions of communication ethics involving demagoguery, persuasion, propaganda, and human rights (Lomas, 1961 ; Nilsen, 1960 ; Parker, 1972 ). Central to these studies were concern for accuracy and truthfulness such that “in each persuasive situation there is an ethical obligation to provide listeners with such information as it is possible to provide in the time available and with the medium used” (Nilsen, 1960 , p. 201).

In the 1980s and 1990s, communication scholars affiliated with what was then the Speech Communication Association (now the National Communication Association) inaugurated the first communication ethics commission and, subsequently, the first national conference on ethics (Arnett, Bell, & Fritz, 2010 ). These early scholars, such as Ken Anderson, James A. Jaksa, Richard Johannesen, Clifford Christians, and Ron Arnett, seeded what was to become a fertile field of scholarship connecting all areas of the discipline in ways that bridged philosophical and applied approaches. Also in the latter half of the 20th century , scholars in communication ethics began to wrestle with the problematics of power and truth in order to interrogate ethical questions regarding the relationship between social standpoint and social justice. Influenced by continental theorists such as Jacques Derrida, Jean-Francoise Lyotard, and Michel Foucault, communication ethics were sometimes characterized by the struggle between objectivist, absolutist questions of truth versus subjective, relativist conceptions of truth. Scholars critical of objectivist perspectives drew upon insights from critical, critical race, feminist, postcolonial and postmodernist theories that challenged prevailing orthodoxies about the nature of identity, the status of the subject, and the role of power in constructing models of “the good.” Scholars such as Molefi Asante, Larry Gross, and Janice Hocker Rushing undertook examinations of the relationship of ethics to racism, sexuality, and sexism (Asante, 1992 ; Gross, 1991 ; Rushing, 1993 ).

Influenced in part by Alasdair MacIntyre’s neo-Aristotlean work, “After Virtue,” as well as Jürgen Habermas’s discourse ethics, public sphere theory, and theory of communicative action, scholars in the last part of the 20th and first part of the 21st century became increasingly interested in ethical questions pertaining to truth conditions in political discourse, such as journalism, political rhetoric, and discourse in the public sphere (Baynes, 1994 ; Ettema & Glasser, 1988 ). At roughly the same time, an increasing number of communication scholars began to draw on the existentialist and hermeneutic continental scholarship of philosophers such as Martin Buber, Martin Heidegger, and Emmanuel Levinas to explore questions of alterity and otherness as it pertained to relational, rhetorical, and mediated communication (Hyde, 2001 ; Pinchevski, 2005 ).

Over the last 100 years, communication ethics has engaged questions about how to create ethical worlds with our communication processes, be they individual, face-to-face, mediated, or institutional. The area of corporate ethics, for example, concerns not “green-leafing” public relations, but institutional practices that create goodness—such as transparency, accountability, and profit-sharing—not just for owners or shareholders, but for all stakeholders including workers, the earth, the animals, and so forth (Groom & Fritz, 2012 ). Some ethicists, such as Zygmunt Bauman, would likely argue that the concept of corporate ethics is itself oxymoronic: “No moral impulse can survive, let alone emerge unscathed from, the acid test of usefulness or profit. All immorality begins with demanding such a test” (Bauman, 1993 ). In short, communication ethics concerns the discernment of the good, seeking to balance the competing values, needs, and wants of multiple constituencies inhabiting pluralistic democracies.

General Characteristics: Heterogeneity, Interconnectivity, and Historicity

At this point in time, communication ethics scholarship can be described by three central characteristics: heterogeneity, interconnectivity, and historicity. Communication ethics is marked by heterogeneity through the sheer multiplicity of ethical concerns, disciplinary contexts, theoretical perspectives, and modes of reasoning it can pursue. A question about deception, for example, could be examined in any number of communication contexts (e.g., social media, political campaigns, workplace organization, family relations), from any of a number of theoretical perspectives or concerns (e.g., ideological, dialogic, rhetorical, universalist), employing any number of modes of ethical reasoning (e.g., virtue, deontological, teleological, care) and any combination within and between these categories. Often ethical perspectives and values bump into one another, and the ethicist may employ multiple modes of thought to weigh the priorities of ethical value against another—questions about harassment for example, concerns the values of freedom of speech balanced against freedom from intimidation and harassment.

But heterogeneity should not be mistaken for relativism (Brummett, 1981 ). 1 Because ethical questions are embedded both tacitly and explicitly in all human interactions, communication scholars look at both covert as well as overt questions of ethics. Mission statements, for example, may set an overt frame for ethical values and ideals that a given organization aspires toward, but they may not facilitate the recognition of more hidden ethical questions that play out in daily operations. Similarly, ethical codes and credos that stipulate their norms and values are often written at the level of the individual and therefore obscure how institutions, organizations, and groups also function as (un)ethical agents. Codes and credos can also interfere with individual ethical agency and decision-making by removing from conscious awareness the need for vigilant attention to ethical issues that may be hidden. Other forms of overt ethics involve public argument, laws, policies, principals, guidelines, and so forth. In contrast, tacit ethics are implicit patterns of communicative interaction institutions that have ethical implications. That is, communication ethics looks not merely at individual agency and intersubjective processes but also at institutional norms, structural arrangements, and systematic patterns. In communication ethics, ethical questions are a question of not (only) individual agency but of shared implicit and explicit habits, norms, and patterns of communicative action. Communication ethics is therefore quite deliberate in examining both overt and covert contexts.

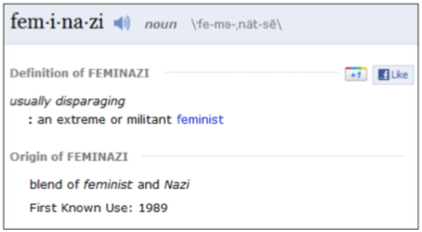

Heterogeneity also arises through the sheer number of values that may come into conflict in any given situation. In the case of hate speech, for example, the values of free speech bump up against the values of freedom from intimidation, harassment, and violation. Similarly, from the purview of communication ethics, context can mean nearly, if not fully, everything. The question of what makes a convincing ethical argument changes from setting to setting. In the context of a religious setting, for example, reasoning based on tradition and authority might take precedence over reasoning based on compassion and care. Within any given religious community, people wrestle with questions about how much they shall be governed by intelligence, compassion, and outcome and how much by faith. When intelligence tells us one thing and compassion another, which should we trust? Similarly, tensions between local and state or federal control can also shape what values or modes of reasoning take precedence. The communication ethicist must face this nearly endlessly multiplicitous diversity in her inquiry into questions of the good.

Because communication ethics is an immanent subfield that, like the myriad processes of communication itself, is inextricable from the deeply interconnected manifestations of all human interaction, our communicative interactions are inevitably intertwined. Interdependency manifests in the recognition that humans are socially embedded beings and therefore that no self exists completely independent of the social conditions (e.g., language, customs, narratives, hierarchies) from which that self emerged. But it is not simply the self that may or may not consciously choose a given action; communication ethicists also look at how actions choose persons. A worker in a health insurance industry is given an incentive to deny health claims knowing not only that if she does not do it someone else will, but that if she refuses she will be fired and her family will lose its insurance, upon which her disabled child depends. How much ethical agency and “freedom” can such a worker exert? Similarly, the financial managers of this company know that without such incentives, the company will lose money leading to layoffs of workers and possibly denial of even more claims. Thus, not only can there be a kind of independent ethical agency that stands apart from the set of relations it inhabits, there is little possibility of any ethical agent perceiving or anticipating all these ethical interconnections. I may serve my family a healthy dinner of quinoa not knowing that, as an indirect result, thousands of peasants high in the Andes can no longer afford to feed their families the very grain they grow.

Communication ethics is also deeply responsive to the historical events, conditions, and conventions that give rise to every communicative interaction. This can be seen in work on public memory, an area fraught with ethical questions—which historical events are commemorated or memorialized, and which are forgotten (Bruner, 2006 ; Vivian, 2010 )? What events rise to the level of national concern—that is, which events are remembered so as to reflect a shared national or cultural identity? Why is there a Holocaust museum but not a Native American genocide museum? Why have there been no reparations for centuries of American slavery? History relates to ethics via other questions of narrative, public and private. What stories are told, from whose point of view? When or how are these stories punctuated, and who speaks and who is ignored? When communication ethics examines concerns of power, it also explores how struggles over meaning and meaning making are always in dialogue with past and present discourses and regimes of power. How do the historical tensions between the differing goals of public education (i.e., serving to foster public goods such as democracy, liberty and citizenship vs. imposing social control through social stratification, compulsory subordination, and coerced conformity) continue to play out in today’s public debates about education policy, from questions of No Child Left Behind to the neoliberal moves to privatization? And what are the implications of education policy for class position, labor conditions, and increasing economic inequality? What has led public discourses about public goods to be subsumed so readily under neoliberal discourses emphasizing self-sufficiency and individual autonomy (Oh & Banjo, 2012 ; Saunders, 2010 )?

Integrity: Truth, Truthfulness, and Trust

Questions of truth and trust have long been at the center of communication ethics inquiry. As she noted in her classic treatise On Lying , Sissela Bok argues that few if any human groups, organizations, institutions, or states could succeed without the background assumptions of truthfulness (Bok, 1979 ). Distinguishing between truth and truthfulness, Bok puts the burden upon an individual’s active intention—intentionally misleading others differs, to Bok, from unknowingly uttering a falsehood. This distinction between conscious intention and unintentional distortion has been central to studies of journalism ethics, where questions of staged, falsified, and censored news are central (Wilcox, 1961 ; Wulfemeyer, 1985 ; Zelizer, 2007 ). Other questions involve the role of objectivity in news, its epistemic (im)possibility, and the ethical implications distinguishing between impartiality and objectivity (Carey, 1989 ; Malcolm, 2011 ; Ward, 2004 ). The role of the press as a watchdog of democracy has also been of central concern to journalist ethicists, principally through its imagined role as the fourth estate (or branch) of American government and the ethical implications of increasingly concentrated corporate ownership (Bagdikian, 2004 ; Huff & Roth, 2013 ; McChesney, 2014 ). A host of other issues, such as censorship, omission, bias, confidentiality, deception, libel, misrepresentation, slander, and witness, have long been central to ethical concerns in journalism. And some scholars, such as Stephen Ward ( 2005 ), have argued for a new philosophical basis for journalism ethics.

But issues of integrity are not just central to journalism—other modes of mediated communication also give rise to ethical questions about appropriation, colonization, and misrepresentation in addition to the kinds of human interactions these media call forth (D’Arcy, 2012 ; Munshi, Broadfoot, & Smith, 2011 ). Jaron Lanier ( 2010 ), for example, has written extensively about ethical questions related to social media, including what he calls “Hive Mind” that induces mob behavior, an overall lack of independence, groupthink, and depersonalization. Lanier also finds fault with social media’s alienation of information from experience and the drive for anonymity that induces violation, reductionism, insincerity, and a general lack of intellectual modesty. Similarly, in an examination of fearless speech, Foucault ( 2001 ) looks into a series of questions about the philosophical foundations of parrhesia: “Who is able to tell the truth? What are the moral, the ethical, and the spiritual conditions which entitle someone to present himself as a truth-teller? About what topics is it important to tell the truth? What are the consequences of telling the truth?”

Ethical questions about truth and truth telling also show up in rhetorical studies, especially those involving regarding history and politics (Johnstone, 1980 ; Newman, 1995 ). Whistleblowing is another communicative phenomenon where issues of integrity meet ethics. Ostensibly, “whistleblowing happens when ethical discourse becomes impossible, when acting ethically is tantamount to becoming a scapegoat” (Alford, 2001 , p. 36). Yet, according to Alford, the common narrative of the whistleblower as a martyr to truth who is seeking institutional redemption is not played out in the lived experiences of whistleblowers. In fact, the whistleblower is by definition only constituted by processes of institutional retaliation wherein the whistleblower is punished and the institution merely carries on. Even laws supposedly aimed to protect whistleblowers function merely at the level of procedure, which work in turn to reinforce institutional power leaving questions of morality as purely private, not public, affairs. “To act politically in this depoliticized public space is to be a scapegoat” (Alford, 2001 , p. 130). Other areas involving integrity in a wide variety of communication ethics contexts include questions of authenticity, betrayal, cynicism, demagoguery, denial, disclosure, distortion, erasure, exposure, falsification, mystification, obfuscation, omission, secrecy, selectivity, silence, surveillance, suspicion, and transparency (Herrscher, 2002 ; Ivie, 1980 ).

Power: Justice, Normativity, and Force

Power is another central thread in communication ethics scholarship that reveals the extent to which politics and ethics are deeply interconnected. Power is here understood to describe the capacity to impose, maintain, repair, and transform particular modes of social structuring that explicitly and implicitly condition our ideas about the good. When ethical values rise to the level of social/cultural importance, they become laws and not merely customs. But all laws and questions of justice are inherently ethical questions insofar as they inherently shape the contours of what any given community conceives of as the good. As Reinhold Niebuhr put it, “Politics will, to the end of history, be an area where conscience and power meet, where the ethical and the coercive factors of human life will interpenetrate and work out tentative and uneasy compromises” ( 2013 , p. 4). The relationships between ethics and power can be understood in terms of three dimensions—justice, normativity, and force.

Normativity is a form of power with wide-ranging ethical implications. Not only do social norms become a framework within which all forms of the good (and by extension, the bad) may be produced, they also invisibly become part of the interconnected embeddedness of the social that make subjectivity itself possible. Gender, for example, is a form of social normativity with far-ranging ethical implications. Not only do gender conventions govern nearly every conceivable variation of human interaction (from the professions to child raising), violations of gender norms are soundly punished, often violently. Similarly, because every binary includes a hierarchy, in the case of gender male standards are not only normative but unmarked as such even while they serve to set the standard of what is “good” in many situations. Thus evaluations of performance of many communicative actions such as oratory, argument, debate, writing, turn-taking, holding the floor, delivering instruction, and so forth, may appear to be gender neutral when in fact the very standards of quality and merit may be deeply embedded in normatively masculine gender conventions. Thus, because of its relation to ideology as a means of legitimating existing social relations and differences of power, status quo, and common sense, normativity can exert tremendous and often invisible power that inevitable engender ethical questions. Who dictates the terms of what is normative, correct, standard, common sense?

At the same time, however, normativity fuels the very machinery of everyday communicative action. Without predetermined conventions, such as those that govern traffic (street, commerce, or Internet), human interactions would be fraught with peril or even simply impossible. Similarly, what some consider to be the social contract—the implicit moral obligations we have by virtue of being part of society—make everyday life in the shared social world possible. But at the same time, norms and conventions by necessity make some things possible and others impossible. A good example of the role of normativity in ethical questions of power relates to the questions of national and world languages. Language plays a significant role in the production, maintenance, and change in relations of power. For example, although to many native English speakers the United States appears to be a monolinguistic society, the truth is quite the contrary. Some tens of millions of American speak more than 25 languages other than English (not including the more than 175 native American languages now spoken in the United States) with 17.5 million Spanish speakers (Schmid, 2001 ). The implications of exclusive usage and public acceptance of English-only policies and laws involve a constellation of ethical questions ranging from access to recognition (in terms of citizenship, voting, education, courts, medical care, etc.).

Similarly, there are enormous political and ethical implications of so-called world English wherein there are 1.5 billion English speakers in the world, where English is designated as an official language of 62 nations, and where English serves of the dominant language of science, academic publishing, and international organizations (Tsuda, 2008 ). From a global perspective, world English can serve as problem of linguistic hegemony, whereby English dominates as a form of linguistic imperialism with ethical consequences ranging from linguistic and communicative inequality, to discrimination, and colonization of the consciousness (Tsuda, 2008 ). Thus, issues of communicative competence are not ethically neutral but can in fact become political means of social stratification employing linguistic, discursive, and social norms. Because discourses are ways of displaying membership in particular social groups, communicative norms can also serve to include as well as exclude, to mark as insider or outsider, and as a means to regulate other forms of behavior. Other issues of normativity that touch on communication ethics therefore include belonging, civility, codes, community, common sense, conformity, consensus, identity, homogeneity, legitimation, locality, loyalty, mimesis, narrativity, political correctness, precepts, principals, propriety, prudence, ratification, representation, rules, standards, uniformity, unity, and universalism (Lozano-Reich & Cloud, 2009 ).

The area of justice provides yet another means by which power interrelates with communication ethics. Typically, justice revolves around questions of rights, fairness, due process, discrimination, equality, equity, impartiality, participation, privilege, recognition, sovereignty, and so forth. The American political philosopher John Rawls maintained that justice was equivalent to fairness, and he designed a thought experiment called the veil of ignorance as a means to determine principles of justice (as fairness) in a given community. Rawls’s veil was intended to conceal the social position of each participant in the deliberation of justice. In other words, people would deem principles of fairness without knowing where in society they would end up at the end of the day. In Rawls’s view, meritocracy cannot be just unless everyone begins at the same starting line with the same resources, experiences, endowments, etc. So what principles would those behind the veil choose? Rawls says we would choose equal basic liberties for everyone, with social and economic inequalities existing only if they worked to the advantage of the least well off members of society. To Rawls, the facts of inequitable distribution of economic or other success or failure are, to a large degree, outside of our control and thus neither just nor unjust . What is just and unjust is the way that public and political institutions deal with these facts. Some communication ethicists, however, have challenged these Rawlsian ideals of the capacity for neutral imagination (Couldry, Gray, & Gillespie, 2013 ; Munshi, Broadfoot, & Smith, 2011 ).

Explicit and overt questions of communication ethics often involve the values of justice. Ethical credos, honor codes, moral principles, and ethical guidelines often stipulate “right vs. wrong” scenarios as a means to get at the good. When questions of justice need to be arbitrated, deliberative methods that weigh first principles, outcomes, and precedent are often employed. But these themselves often beg the ethical question of who deliberates, under what conditions, and with what resources (Fraser, 1994 ; Habermas, 1989 ). A community dialogue meant to empower citizens largely disenfranchised from the halls of power must contend with questions of access, competence, and convention that underlie the very possibilities of deliberation. For example, when knowledge and communication skills leading to social power are made available to advantaged social groups but are withheld from less advantaged groups in society, a community “dialogue” can inadvertently become an instrument of injustice (Gastil, Lingle, & Deess, 2010 ; Jovanovic, 2012 ). Similarly, inequitable access to the resources of symbolic capital—the prestige, privilege, and education needed to constitute arguments—cannot be just if the allocation of those resources is unequal and available only to a few.

Questions of force are often directly related to justice in that they present manifestations of state and social power that can violently silence, repress, or simply rule “out of order” questions of justice. Force creates situations in which people are not able to speak for themselves, where those in power do not listen, and when the very language needed to articulate claims to justice is not understood. An example of the ethical dimensions of force can be seen in Scott’s ( 1990 ) idea of the “hidden transcript,” a form of hidden public discourse produced by and witnessed only by those without the power to set norms and the claims of justice. As Scott writes, even the most violent political oppression never completely silences the voices of the oppressed—the unspeakable is spoken clandestinely through discourse hidden from those in power: “Most of the political life of subordinate groups is to be found neither in overt collective defiance of power holders nor in complete hegemonic compliance, but in the vast territory between these two polar opposites” ( 1990 , p. 136). Similarly, Squires ( 2002 ) draws on this concept to examine how subordinated groups voice political resistance in disguise, hidden between the lines of the official or public transcript in a multiplicity of coded forms: “In the history of Black public spheres, the pressures of living in a racist society, the ongoing fight for equality, and the rich cultural reserves have necessitated” the use of hidden transcripts (Squires, 2002 , p. 457). Thus explicit force such as prohibitions of speaking and listening are met with implicit and explicit modes of force involving rumor, gossip, disguises, linguistic tricks, metaphors, euphemisms, folktales, and ritual gestures: “For good reason, nothing is entirely straightforward here; the realities of power for subordinate groups mean that much of their political action requires interpretation precisely because it is intended to be cryptic and opaque” (Scott, 1990 , p. 137).

Other forms of the power of force can be seen in the selective aggregation of “big data” by media and Internet conglomerates, or the everyday silencing, censorship, coercion, compulsion, confession, diagnosis, interrogation, negation, marginalization, repression, and prohibition that occur in workplaces, schools, governments, and other organizations where force overtly and covertly serves power (Fairfield & Shtein, 2014 ; Nunan & Di Domenico, 2013 ). But force also resists power in forms such as (re)appropriation, critique, extortion, framing, mobility, negation, networks, parrhesia, speaking truth to power, subversion, and even violence. For example, during the height of state violence in response to the American civil rights movement, a group of Quakers began pamphleteering, witnessing, and organizing in search for forceful responses to violence. In their 1955 pamphlet, “Speak truth to Power,” the Quakers wrote, “if ever truth reaches power, if ever it speaks to the individual citizen, it will not be the argument that convinces. Rather it will be his own inner sense of integrity that impels him to say, ‘Here I stand. Regardless of relevance or consequence, I can do no other’” (Rustin, 1955 , p. 68).

Relation: Alterity and Compassion

Another central thread of communication ethics is the idea of the relation as ontologically basic, meaning that no self can exist outside of the myriad relationships that make up the social matrix of communication. As Martin Buber wrote, “man did not exist before having a fellow being, before he lived over against him, toward him, and that means before he had dealings with him. Language never existed before address” ( 1998 , p. 105). The relational thread of communication ethics calls upon us to never lose sight of the radical alterity, or otherness, of the other. That is, we are asked to never mistake our understanding of the other for the other herself , never to impose our meaning and understanding upon him, never to attempt to absorb/assimilate/appropriate the other into ourselves. We are enjoined to avoid absorbing the other’s difference into my own same .

One of the central concerns of communication ethics pertains to our relation to others and, in particular, to the radical otherness , or alterity, of others. Postmodern and post-colonial literatures have clearly identified and lucidly critiqued the many ways in which political hegemons cast the other in the role of feared and threatening stranger where the other is depicted as without humanity or legitimacy, resulting in patterns of annihilation, oppression, and alienation or of appropriation, assimilation, and absorption. In contrast, the ethical relation to alterity approaches the other as welcomed—as “the stranger, the widow, the orphan” (Levinas, 1969 , p. 77). To Levinas, the other is a moral center to whom one owes everything, and the other must always come first, not last: “To recognize the Other is to recognize a hunger. To recognize the Other is to give. But it is to give to the master, to the lord, to him whom one approaches as ‘Vous’ in a dimension of height” ( 1969 , p. 75).

In writing about this second, ethical sense of alterity, Levinas observes how the other is always more than she appears: “The face of the Other at each moment destroys and overflows the plastic image it leaves me” ( 1969 , p. 51). The acknowledgment of alterity enables speakers to acknowledge, if not honor, radical differences in thought, belief, political and social location, communicative, symbolic and social capital, and so forth. Other aspects of alterity that arise in communication ethics involve relations of alienation, ambiguity, asymmetry, contradiction, cosmopolitanism, discord, diversity, incongruity, interruption, intersectionality, and ostracism (Arneson, 2014 ; Hyde, 2012 ; Pinchevski, 2005 ).

Thus, unlike a Habermasian discourse ethics of the ideal speech situation, where interlocutors are instructed to “bracket status differentials and deliberate as if they were social equals,” (Fraser, 1994 , p. 117), or a Rawlsian theory of justice, which asks interlocutors to deliberate behind a “veil of ignorance,” alterity deliberately invites and acknowledges difference, acknowledging that each of us arrive “on the scene” of communication with different histories, traditions, values, and experiences. The acknowledgment of alterity gives rise to a sense of ethical responsibility—the ability to respond to the other—which leads to compassion. To Buber, therefore, “Genuine responsibility exists only when there is real responding” ( 1975 , p. 16). Ethical compassion arises not because one identifies with the others’ suffering but because one recognizes the other’s alterity, and therefore, her suffering. As Noddings writes, “I do not ‘put myself in the other's shoes,’ so to speak, by analyzing his reality as objective data and then asking, ‘How would I feel in such a situation?’ On the contrary, I set aside my temptation to analyze and plan. I do not project; I receive the other into myself, and I see and feel with the other” ( 1984 , p. 30).

Noddings illustrates the idea of empathic engrossment as our response to an infant crying. We know something is wrong, and the infant’s feeling becomes ours. This is not a problem-solving state, but a feeling-with state. Thus ethical compassion is not vulnerable to ideological ideas about worthy and unworthy suffering but simply feels with the other because she is suffering. Therefore, relational compassion is open to transformation of the self wherein “we are not attempting to transform the world, but we are allowing ourselves to be transformed” (Noddings, 1984 , p. 34). The relational dimension of communication ethics are also important in feminist care-based ethics, focusing less on the rights of individuals and more upon caring responsibilities in relationships (Tronto, 1993 ). Other dimensions of compassion that arise in communication ethics involve acknowledgment, advocacy, affirmation, amnesty, atonement, attunement, embodiment, forgiveness, generosity, gratitude, humility, kindness, leisure, precarity, reconciliation, and sharing (Arnett, 2013 ; Holba, 2014 ).

Discussion of the Literature: Five Modes of Ethical Reasoning

As a branch of philosophy, ethics concerns questions about what makes some actions right and some wrong in a given context. Throughout history all cultures have developed particular doctrines or philosophies of the good, many of which are classified in the West along four primary lines: virtue ethics , which locate the good in the virtuous character and qualities of actions or individuals; deontological ethics , which locate the good in an act or an individual’s adherence to duties or principles; teleological ethics , which locate the good in the consequences of actions and choices; and dialogic ethics , which locate the good in the relations between persons. During the 20th century , postmodern ethics has called these prior ethical theories into question by challenging not merely the value of rules, procedures, systems, and fixed categories for understanding or theorizing ethics, but the humanist ideas of persons as autonomous agents who can act independently as ethical agents. Below are described five such modes of ethical reasoning.

Most commonly associated with the 5th-century bce Greek philosopher Aristotle, virtue ethics focus on the choice, cultivation, and enactment of “virtuous” qualities, such as courage, temperance, truthfulness, and justice, in both the individual and in civic life. In his foundational Nicomachean Ethics , Aristotle ( 1998 ) describes how virtue is an expression of character in which we become temperate by doing temperate acts. In the Aristotelian sense, then, ethics are a human activity rather than a creed, principle, or goal. Most religious traditions articulate a number of overlapping virtues, many of which derive in turn from even earlier traditions and cultures. For example, the so-called cardinal virtues of 12th-century Roman Christianity emphasize courage, prudence, temperance, and justice; these were derived from the earlier Greek philosophies of Plato and Aristotle that in turn derive from far earlier Egyptian wisdom literature (ca. 3000 bce ). Similarly, the 5th-century bce Paramitas of Indian Buddhism stress generosity, patience, honesty, and compassion and are derived in part from virtues articulated in Hindu scriptures that originated around 1000 bce . Further east in 5th-century bce China, both Confusianism and Taoism identified virtues such as empathy, reciprocity, and harmony for the cultivation of an ethical personal and civic life. Even the 18th-century American political virtues of Jeffersonian democracy (inscribed in the Declaration of Independence as life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness) derive in part from the Aristotelian idea of eudaimonia , the happiness caused by living a virtuous life. Outside of religious traditions, contemporary Euro-American theorists of ethical virtue, sometimes called neo-Aristotelians, locate virtue variously, for example, in the enactment of intentions and motives (Phillipa Foot, Michael Slote), in practical action or phronesis (Alasdair MacIntyre), and in the civic value of emotions, especially compassion (Martha Nussbaum).

Deontological ethics (derived from the Greek word for duty ) are most commonly associated with the 18th-century Prussian philosopher Immanuel Kant, who constructed a theory of moral reasoning based not on virtues, outcomes, or emotions but on duties and obligations. In his book Foundations for a Metaphysics of Morals , Kant proposes that ethics are based on a universal law that he calls the categorical imperative . Sometimes mistakenly confused with the golden rule (i.e., do unto others as you would have them do unto you ), the categorical imperative holds that a person should only act on the principles that she or he would want everyone else to always act upon. Kant’s universal law is categorical because there are absolutely no exceptions under any conditions, and it is imperative because it is a necessary duty to which everyone must adhere. But the imperative is dictated not by goods in and of themselves, but by logical reasoning. For example, Kant argues that the ethical prohibition against lying is a categorical imperative because if lying were universalized, no one would believe lies, which depend for themselves on public trust. Bok’s work on lying builds upon this logical contradiction inherent in lying. Similarly, the second formulation of Kant’s categorical imperative—which states that we should never treat people as means to our ends, but always as ends in and of themselves—is readily understood as a universalizable, prohibitive law. Other deontological ethical theories include religious and monastic approaches (such as adhering to divine commands, doctrinal principles, and the fulfillment of monastic vows) and social-contract theories based on the philosophers Thomas Hobbes and Jeans-Jacques Rousseau. In contemporary Euro-American contexts, deontologists, also called neo-Kantians, have developed rights-based approaches (e.g., John Rawls’s theory of justice ), discourse-based approaches (e.g., Jürgen Habermas’s discourse ethics ), and contract-based approaches (e.g., Thomas Scanlon’s contractualism ). Significantly for communication, both Habermas’s and Rawls’s theories center on processes of communication from which ethical norms and principles are derived. For example, Habermas’s discourse ethics prescribes the development and acceptance of rationally grounded validity claims and nontranscendable norms that are produced in democratic argumentation, whereas Rawls’s theory of justice relies upon the discursive achievement of overlapping consensus and public reason . Both approaches have been critiqued on a number of grounds from differing theoretical perspectives, including feminist, postmodernist, Marxist, communitarian, libertarian, and noncognitivist. For example, Chantal Mouffe critiques both Habermas’s and Rawls’s theories because they rely upon idealized, conceptually impossible, and hyper-rational models of deliberative democracy.

Sometimes considered the foil of deontological ethics, teleologica l (from the Greek word for goal ) ethical theories (also known as consequentialist ) exercise moral judgments based on the outcomes and consequences of actions rather than on principles, duties, or virtues. Among the most common ethical theories are utilitarianism and ethical egoism . Utilitarianism, associated with the 18th-century British philosophies of John Stuart Mill and Jeremy Bentham, theorizes that we are ethically bound to do what is best for the most people. According to Mill, for example, actions are good when they promote the greatest happiness for the greatest number . In the contemporary Euro-American context, consequentialist theorists include Peter Singer, who extends utilitarianism to include the good of animals and other beings on the planet; Shelly Kagan, who defends consequentialism from critiques by contemporary deontological ethicists; and Amartya Sen, who applies utilitarian ethics to economics, democracy, and public health. Another form of teleological ethics— ethical egoism (which is sometimes called rational self-interest theory)—theorizes that all ethical actions are ultimately self-serving, even those that appear to be self-sacrificing. Some contemporary theorists argue an ethical egoist position from a psychological point of view that stresses the emotional and social benefits of ethical actions to self, whereas others argue ethical egoism from an evolutionary point of view that stresses the genetic and biological benefits to self. Still others argue ethical egoism from a rational point of view, positing that both individuals and society benefit when each individual benefits. Teleological ethics have been critiqued on a number of grounds from a number of perspectives, especially the deontological and virtue-based approaches. Martha Nussbaum, for example, argues that consequentialist reasoning all too easily leads to a kind of heartless cost-benefit calculation that excludes the full expanses of the ethical.

Associated largely with late 20th-century Euro-American philosophers, such as Zygmunt Bauman, Joseph Caputo, and Michel Foucault, but also with feminist ethicists such as Carol Gilligan, Joan Tronto, and Nel Noddings, postmodern ethicists critique so-called modernist and enlightenment ethical philosophies such as virtue, deontological, and teleological ethics. Rather than conceptualizing human beings as free, autonomous, independent, and rational agents, as do the modernist theorists, postmodernists view human beings as inter-related, interdependent, contradictory, emotional, and, occasionally at least, irrational social beings. Drawing in part on the 19th-century philosopher Frederick Nietzsche, who crafted a brilliant challenge to traditional religion, philosophy, and morality, postmodern ethicists further reject modernist ideals of certainty, universalism, and essentialism, as well as rules, codifications, and systems. In place of ethical rules or precepts, for example, Zygmunt Bauman posits the idea of moral responsibility in which each person must stretch out towards others in pursuit of the good in all situations, even, or perhaps most especially, when what is the good is most uncertain. Thus, Bauman cautions against certainty, calculation, and precept, arguing that reason alone is an insufficient basis for ethical action. Similarly, feminist ethicists from a range of perspectives, such as Annette Baier’s virtue-oriented ethics to Chantal Mouffe’s Marxist-oriented ethics, critique deontological perspectives such as Rawls’s idea of the priority of the right over the good because it categorically privileges individualistic and abstract rights over collective goods and values. From a somewhat different postmodern perspective, Michel Foucault posits ethics as caring for the self through what he calls a practice of freedom . Joseph Caputo, in contrast, argues against ethics itself and in its place posits the affirmation of the other, the singularity of each ethical situation, and the centrality of the unqualified, unconditional gift that requires precisely those things that are not required.

Rather than theorizing an ethics based in individual character, duty, outcome, or interest, dialogic ethics locates the ethical in the intersubjective sphere of communicative relationships between and among persons. The issues of response and responsibility are woven into the center of dialogic ethics. Associated largely with the work of two 20th-century Jewish European philosophers, Martin Buber and Emmanuel Levinas, dialogic ethics posits ethics as first philosophy wherein the ethical relation with the other, rather than the ontology of the self, is understood to be foundational to human experience. To Buber, the person becomes a person by saying Thou and thereby entering into relation with other persons. The Thou , in Buber’s understanding, is not a monadic subjectivity but a relation of intersubjectivity , or development of mutual meaning, that arises from people cohabiting communication exchanges in which understanding arises from what happens in between the subjectivity of persons. To Levinas, one’s personal subjectivity can only arise through one’s own responsibility to the other , who is utterly different from oneself and to whom one owes everything. Dialogic ethics thus requires a healthy respect for the irreducible alerity , or otherness, of persons with whom one has dialogue, wherein the self never mistakes its own understanding of the other for the other herself. In the context of communication studies, dialogic ethics has generated a rich body of research by contemporary scholars such as Kenneth Anderson, Ronald Arnett, Rob Cissna, Michael Hyde, and Jeffrey Murray, wherein the ultimate issues in communication ethics pertain not so much to words themselves but rather to the ethical realm in which communication is constitutive of persons, cultures, publics, and relationships. For example, to Cissna and Anderson, dialogic ethics involve an awakening of other-awareness that occurs in and through a moment of meeting.

In the field of communication, ethicists make use of all of the above theories in approaching questions of ethics in interpersonal, intercultural, mediated, institutional, organizational, rhetorical, political, and public communication contexts. Clifford Christians and Michael Traber, for example, take a deontological approach in searching for ethical universals and protonorms across cultures. In contrast, Josina Makau and Ronald Arnett take a more dialogic approach in a volume on communication ethics and diversity. In contrast, Fred Casmir takes a multi-perspectival approach to intercultural and international communication ethics. More recently, Michael Hyde has drawn on the dialogic ethics of Emmanuel Levinas to explore ethical rhetorical action in personal and public life, and Sharon Bracci and Clifford Christians have brought a wide range of ethical perspectives to bear on a range of communication questions.

In the classroom, communication ethicists emphasize the importance of cultivating attunement to silences, erasures, and misrecognitions that occur when one voice speaks in place of another or when another is silenced. By asking questions such as who speaks, who is heard, or whose voice is rendered unintelligible, students are encouraged to more fully recognize both tacit and overt ethical questions in all manner of communicative interactions. While most communication ethics textbooks tend to include some combination of theory, disciplinary context, and applied context, each tends to principally emphasize one or two of these areas. Some communication ethics textbooks are organized principally around modes of moral reasoning, while others address ethics as it is understood in different areas of the field. Some textbooks are embedded in specific applied contexts such as the workplace or the media, and some attempt to combine theory, disciplinary context, and value.

Addendum: Some Key Themes of Communication Ethics

Websites/other information.

Communication Ethics Division of NCA: http://commethics.org/news/

Institute of Communication Ethics: http://www.communicationethics.net/sales/index.php?nav=book .

Quintilian’s Institutes of Oratory: http://rhetoric.eserver.org/quintilian/

Further Reading

- Anderson, K. E. , & Tompkins, P. S. (2015). Practicing communication ethics: Development, discernment, and decision-making . New York, NY: Routledge.

- Arnett, R. C. (1986). Communication and community: Implications of Martin Buber’s dialogue . Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Casmir, F. L. (1997). Ethics in intercultural and international communication . Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Cheney, G. , Lair, D. J. , Ritz, D. , & Kendall, B. E. (2009). Just a job? : Communication, ethics, and professional life . New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Cheney, G. , May, S. , & Munshi, D . (Eds.). (2011). The handbook of communication ethics . New York, NY: Routledge.

- Chesebro, J. W. (1973). Cultures in conflict—a generic and axiological view. Today’s Speech , 21 (2), 11–20.

- Christians, C. , & Traber, M. (1997). Communication ethics and universal values . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Cissna, K. N. , & Anderson, R. (2002). Moments of meeting: Buber, Rogers, and the potential for public dialogue . Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Couldry, N. , Madianou, M. , & Pinchevski, A . (Eds.). (2013). Ethics of media . Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Etieyibo, E. (2011). The ethics of government privatisation in Nigeria. Thought and Practice , 3 (1), 87–112.

- Foucault, M. (1997). Ethics: Subjectivity and truth ( P. Rabinow , Ed., R. Hurley et al., Trans.). New York, NY: The New Press.

- Habermas, J. (1990). Moral consciousness and communicative action . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Hardwig, J. (1973). The achievement of moral rationality. Philosophy and Rhetoric , 6 (3), 171–185.

- Harker, M. (2007). The ethics of argument: Rereading Kairos and making sense in a timely fashion. CCC , 59 (1), 77–97.

- Hyde, M. J. (2001). The call of conscience: Heidegger and Levinas . Columbia: University of South Carolina Press.

- Johannesen, R. L. (2002). Ethics in human communication (5th ed.). Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press.

- Johnstone, C. L. (1983). Dewey, ethics, and rhetoric: Toward a contemporary conception of practical wisdom. Philosophy and Rhetoric , 16 (3), 185–207.

- Levinas, E. (1998). Otherwise than being . ( Alphonso Lingis , Trans.). Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

- Lipari, L. (2014). Listening, thinking, being: Toward an ethics of attunement . State College: Penn sylvania State University Press.

- Makau, J. M. (1997). Communication ethics in an age of diversity . Urbana: University of Illiinois.

- Mumby, D. K. (1987). The political function of narrative in organizations. Communication Monographs , 54 (2), 113–127.

- Nussbaum, M. (1995). Poetic justice: The literary imagination and public life . Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Parker, D. H. (1972). Rhetoric, ethics and manipulation. Philosophy and Rhetoric , 5 (2), 69–87.

- Prellwitz, J. H. (2011). Nietzschean genealogy and communication ethics. Review of Communication , 11 (1), 1–19.

- Roberts, K. G. , & Arnett, R. C . (Eds.). (2008). Communication ethics: Between cosmopolitanism and provinciality. Critical Intercultural Communication Studies, Vol. 12 . New York, NY: P. Lang.

- Singer, P. (1995). How are we to live? Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

- Alford, C. F. (2001). Whistleblowers: Broken lives and organizational power . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Aristotle . (1998). The Nichomachean ethics ( David Ross , Trans.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Arneson, P. (2014). Communicative engagement and social liberation: Justice will be made . Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

- Arnett, R. (1987). The status of communication ethics scholarship in speech communication journals from 1915 to 1985. Central States Speech Journal , 38 (1), 44–61.

- Arnett, R. (2013). Communication ethics in dark times: Hannah Arendt’s rhetoric of warning and hope . Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Arnett, R. C. , Bell, L. M. , & Fritz, J. M. H. (2010). Dialogic learning as first principle in communication ethics. Atlantic Journal of Communication , 18 (3), 111–126.

- Asante, M. K. (1992). The escape into hyperbole: Communication and political correctness. Journal of Communication , 42 (2), 141–147.

- Bagdikian, B. H. , & Bagdikian, B. H. (2004). The new media monopoly . Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Bauman, Z. Postmodern Ethics . (1993). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Baynes, K. (1994). Communicative ethics, the public sphere and communication media. Critical Studies in Mass Communication , 11 (4), 315–326.

- Bok, S. (1979). Lying: Moral choice in public and private life . New York, NY: Vintage Books.

- Brummett, B. (1981). A defense of ethical relativism as rhetorically grounded. Western Journal of Speech Communication: WJSC , 45 (4), 286–298.

- Bruner, M. L. (2006). (e)merging rhetorical histories. Advances in the History of Rhetoric , 9 , 171–185.

- Buber, M. (1975). Between man and man . New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Buber, M. (1998). The knowledge of man: Selected essays . Amherst, NY: Humanity Books.

- Carey, J. W. (1989). Communication as culture: Essays on media and society . Boston, MA: Unwin Press.

- Couldry, N. , Gray, M. L. , & Gillespie, T. (2013). Culture digitally: Digital in/justice. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media , 57 (4), 608–617.

- D’Arcy, A. , & Young, T. M. (2012). Ethics and social media: Implications for sociolinguistics in the networked public. Journal of Sociolinguistics , 16 (4), 532–546.

- Ettema, J. S. , & Glasser, T. L. (1988). Narrative form and moral force: The realization of innocence and guilt through investigative journalism. Journal of Communication , 38 (3), 8–26.

- Fairfield, J. , & Shtein, H. (2014). Big data, big problems: Emerging issues in the ethics of data science and journalism. Journal of Mass Media Ethics , 29 (1), 38–51.

- Foucault, M. (2001). Fearless speech . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Fraser, N. (1994). Rethinking the public sphere: A contribution to the critique of actually existing democracy. In C. Calhoun (Ed.), Habermas and the public sphere (pp. 109–142). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Gastil, J. , Lingle, C. J. , & Deess, E. P. (2010). Deliberation and global criminal justice: Juries in the International Criminal Court. Ethics and International Affairs , 24(1), 69–90.

- Gehrke, P. J. (2009). The ethics and politics of speech: Communication and rhetoric in the twentieth century . Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Groom, S. A. , & Fritz, J. M. H . (Eds.). (2012). Communication ethics and crisis: Negotiating differences in public and private spheres . Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

- Gross, L. (1991). The contested closet: The ethics and politics of outing. Critical Studies in Mass Communication , 8 (3), 352–388.

- Habermas, J. (1989). The structural transformation of the public sphere: An inquiry into a category of bourgeois society . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Herrscher, R. (2002). A universal code of journalism ethics: Problems, limitations, and proposals. Journal of Mass Media Ethics , 17 (4), 277–289.

- Holba, A. M. (2014). In defense of leisure. Communication Quarterly , 62 (2), 179–192.

- Huff, M. , Roth, A. L. , & Project Censored . (2013). Censored 2014: Fearless speech in fateful times; the top censored stories and media analysis of 2012–13 . New York, NY: Seven Stories Press.

- Hyde, M. J. (2012). Openings: Acknowledging essential moments in human communication . Waco, TX: Baylor University Press.

- Ivie, R. L. (1980). Images of savagery in American justifications for war. Communication Monographs , 47 (4), 279–294.

- Johnstone, C. L. (1980). An Aristotelian trilogy: Ethics, rhetoric, politics, and the search for moral truth. Philosophy and Rhetoric , 13 (1), 1–24.

- Jovanovic, S. (2012). Democracy, dialogue, and community action: Truth and reconciliation in Greensboro . Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press.

- Lanier, J. (2010). You are not a gadget: A manifesto . New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Levinas, E. (1969). Totality and infinity: An essay on exteriority ( A. Lingis , Trans.). Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

- Lomas, C. W. (1961). The rhetoric of demagoguery. Western Speech , 25 (3), 160–168.

- Lozano-Reich, N. M. , & Cloud, D. L. (2009). The uncivil tongue: Invitational rhetoric and the problem of inequality. Western Journal of Communication , 73 (2), 220–226.

- Malcolm, J. (2011). The journalist and the murderer . New York, NY: Knopf.

- McChesney, R. W. (2014). Blowing the roof off the twenty-first century: Media, politics, and the struggle for post-capitalist democracy . New York, NY: Monthly Review Press.

- Munshi, D. , Broadfoot, K. J. , & Smith, L. T. (2011). Decolonizing communication ethics: A framework for communicating otherwise. In G. Cheney (Ed.), The handbook of communication ethics (pp. 119–132). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Newman, R. P. (1995). Truman and the Hiroshima cult . East Lansing: Michigan State University Press.

- Niebuhr, R. (2013). Moral man and immoral society: A study in ethics and politics (2nd ed.). Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press.

- Nilsen, T. R. (1960). Persuasion and human rights. Western Speech , 24 (4), 201–205.

- Noddings, N. (1984). Caring: A feminine approach to ethics and moral education . Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Nunan, D. , & Di Domenico, M. (2013). Market research and the ethics of big data. International Journal of Market Research , 55 (4), 2–13.

- Oh, D. , & Banjo, O. O. (2012). Outsourcing postracialism: Voicing neoliberal multiculturalism in Outsourced . Communication Theory , 22 (4), 449–470.

- Pinchevski, A. (2005). By way of interruption: Levinas and the ethics of communication . Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University Press.

- Quintilian . (2006). Institutes of oratory ( L. Honeycutt , Ed, J. S. Watson , Trans.). Retrieved from http://rhetoric.eserver.org/quintilian/

- Rushing, J. H. (1993). Power, other, and spirit in cultural texts. Western Journal of Communication , 57 (2), 159–168.

- Rustin, B. , Cary, S. G. , Bristol, J. E. , Chakravarty, A. , Chalmers, A. B. , Edgerton, W. B. , et al. (1955). The American Friends Service Committee. Speak truth to power: A Quaker search for an alternative to violence . A Study of International Conflict Prepared for the American Friends Service Committee. Approved for publication March 2, 1955.

- Saunders, D. B. (2010). Neoliberal ideology and public higher education in the United States. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies , 8 (1), 42–77.

- Schmid, C. L. (2001). Politics of language: Conflict, identity, and cultural pluralism in comparative perspective . Cary, NC: Oxford University Press.

- Scott, J. C. (1990). Domination and the arts of resistance. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Squires, C. R. (2002). Rethinking the black public sphere. Communication Theory , 12 (4), 446–468.

- Tronto, J. (1993). Moral boundaries: A political argument for an ethic of care . New York, NY: Routledge.

- Tsuda, Y. (2008). English hegemony and English divide. China Media Research , 4 (1), 47–55.

- Vivian, B. (2010). Public forgetting: The rhetoric and politics of beginning again . State College: Pennsylvania State Press.

- Ward, S. J. A. (2005). Philosophical foundations for global journalism ethics. Journal of Mass Media Ethics , 20 (1), 3–21.

- Ward, S. J. A. (2004). The invention of journalism ethics: The path to objectivity and beyond . Montreal, Canada: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Wilcox, W. (1961). The staged news photograph and professional ethics. Journalism Quarterly , 38 , 497–504.

- Wulfemeyer, K. T. (1985). How and why anonymous attribution is used by Time and Newsweek . Journalism Quarterly , 6 2(1), 81–126.

- Zelizer, B. (2007). On “having been there”: “Eyewitnessing” as a journalistic key word. Critical Studies in Media Communication , 24 (5), 408–428.

1. And some scholars have made the case for ethical relativism in certain contexts of communication. See, for example, Barry Brummett , A Defense of Ethical Relativism as Rhetorically Grounded, Western Journal of Speech Communication: WJSC , 45 (4) (Fall 1981), 286–298.

Related Articles

- Rehabilitation Groups

- Communication Privacy Management Theory and Health and Risk Messaging

- Dialogue, Listening, and Ethics

- Global Media Ethics

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Communication. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 15 May 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.39.149.46]

- 185.39.149.46

Character limit 500 /500

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies