- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

Can You Use First-Person Pronouns (I/we) in a Research Paper?

Research writers frequently wonder whether the first person can be used in academic and scientific writing. In truth, for generations, we’ve been discouraged from using “I” and “we” in academic writing simply due to old habits. That’s right—there’s no reason why you can’t use these words! In fact, the academic community used first-person pronouns until the 1920s, when the third person and passive-voice constructions (that is, “boring” writing) were adopted–prominently expressed, for example, in Strunk and White’s classic writing manual “Elements of Style” first published in 1918, that advised writers to place themselves “in the background” and not draw attention to themselves.

In recent decades, however, changing attitudes about the first person in academic writing has led to a paradigm shift, and we have, however, we’ve shifted back to producing active and engaging prose that incorporates the first person.

Can You Use “I” in a Research Paper?

However, “I” and “we” still have some generally accepted pronoun rules writers should follow. For example, the first person is more likely used in the abstract , Introduction section , Discussion section , and Conclusion section of an academic paper while the third person and passive constructions are found in the Methods section and Results section .

In this article, we discuss when you should avoid personal pronouns and when they may enhance your writing.

It’s Okay to Use First-Person Pronouns to:

- clarify meaning by eliminating passive voice constructions;

- establish authority and credibility (e.g., assert ethos, the Aristotelian rhetorical term referring to the personal character);

- express interest in a subject matter (typically found in rapid correspondence);

- establish personal connections with readers, particularly regarding anecdotal or hypothetical situations (common in philosophy, religion, and similar fields, particularly to explore how certain concepts might impact personal life. Additionally, artistic disciplines may also encourage personal perspectives more than other subjects);

- to emphasize or distinguish your perspective while discussing existing literature; and

- to create a conversational tone (rare in academic writing).

The First Person Should Be Avoided When:

- doing so would remove objectivity and give the impression that results or observations are unique to your perspective;

- you wish to maintain an objective tone that would suggest your study minimized biases as best as possible; and

- expressing your thoughts generally (phrases like “I think” are unnecessary because any statement that isn’t cited should be yours).

Usage Examples

The following examples compare the impact of using and avoiding first-person pronouns.

Example 1 (First Person Preferred):

To understand the effects of global warming on coastal regions, changes in sea levels, storm surge occurrences and precipitation amounts were examined .

[Note: When a long phrase acts as the subject of a passive-voice construction, the sentence becomes difficult to digest. Additionally, since the author(s) conducted the research, it would be clearer to specifically mention them when discussing the focus of a project.]

We examined changes in sea levels, storm surge occurrences, and precipitation amounts to understand how global warming impacts coastal regions.

[Note: When describing the focus of a research project, authors often replace “we” with phrases such as “this study” or “this paper.” “We,” however, is acceptable in this context, including for scientific disciplines. In fact, papers published the vast majority of scientific journals these days use “we” to establish an active voice. Be careful when using “this study” or “this paper” with verbs that clearly couldn’t have performed the action. For example, “we attempt to demonstrate” works, but “the study attempts to demonstrate” does not; the study is not a person.]

Example 2 (First Person Discouraged):

From the various data points we have received , we observed that higher frequencies of runoffs from heavy rainfall have occurred in coastal regions where temperatures have increased by at least 0.9°C.

[Note: Introducing personal pronouns when discussing results raises questions regarding the reproducibility of a study. However, mathematics fields generally tolerate phrases such as “in X example, we see…”]

Coastal regions with temperature increases averaging more than 0.9°C experienced higher frequencies of runoffs from heavy rainfall.

[Note: We removed the passive voice and maintained objectivity and assertiveness by specifically identifying the cause-and-effect elements as the actor and recipient of the main action verb. Additionally, in this version, the results appear independent of any person’s perspective.]

Example 3 (First Person Preferred):

In contrast to the study by Jones et al. (2001), which suggests that milk consumption is safe for adults, the Miller study (2005) revealed the potential hazards of ingesting milk. The authors confirm this latter finding.

[Note: “Authors” in the last sentence above is unclear. Does the term refer to Jones et al., Miller, or the authors of the current paper?]

In contrast to the study by Jones et al. (2001), which suggests that milk consumption is safe for adults, the Miller study (2005) revealed the potential hazards of ingesting milk. We confirm this latter finding.

[Note: By using “we,” this sentence clarifies the actor and emphasizes the significance of the recent findings reported in this paper. Indeed, “I” and “we” are acceptable in most scientific fields to compare an author’s works with other researchers’ publications. The APA encourages using personal pronouns for this context. The social sciences broaden this scope to allow discussion of personal perspectives, irrespective of comparisons to other literature.]

Other Tips about Using Personal Pronouns

- Avoid starting a sentence with personal pronouns. The beginning of a sentence is a noticeable position that draws readers’ attention. Thus, using personal pronouns as the first one or two words of a sentence will draw unnecessary attention to them (unless, of course, that was your intent).

- Be careful how you define “we.” It should only refer to the authors and never the audience unless your intention is to write a conversational piece rather than a scholarly document! After all, the readers were not involved in analyzing or formulating the conclusions presented in your paper (although, we note that the point of your paper is to persuade readers to reach the same conclusions you did). While this is not a hard-and-fast rule, if you do want to use “we” to refer to a larger class of people, clearly define the term “we” in the sentence. For example, “As researchers, we frequently question…”

- First-person writing is becoming more acceptable under Modern English usage standards; however, the second-person pronoun “you” is still generally unacceptable because it is too casual for academic writing.

- Take all of the above notes with a grain of salt. That is, double-check your institution or target journal’s author guidelines . Some organizations may prohibit the use of personal pronouns.

- As an extra tip, before submission, you should always read through the most recent issues of a journal to get a better sense of the editors’ preferred writing styles and conventions.

Wordvice Resources

For more general advice on how to use active and passive voice in research papers, on how to paraphrase , or for a list of useful phrases for academic writing , head over to the Wordvice Academic Resources pages . And for more professional proofreading services , visit our Academic Editing and P aper Editing Services pages.

- How it works

Use of Pronouns in Academic Writing

Published by Alvin Nicolas at August 17th, 2021 , Revised On August 24, 2023

Pronouns are words that make reference to both specific and nonspecific things and people. They are used in place of nouns.

First-person pronouns (I, We) are rarely used in academic writing. They are primarily used in a reflective piece, such as a reflective essay or personal statement. You should avoid using second-person pronouns such as “you” and “yours”. The use of third-person pronouns (He, She, They) is allowed, but it is still recommended to consider gender bias when using them in academic writing.

The antecedent of a pronoun is the noun that the pronoun represents. In English, you will see the antecedent appear both before and after the pronoun, even though it is usually mentioned in the text before the pronoun. The students could not complete the work on time because they procrastinated for too long. Before he devoured a big burger, Michael looked a bit nervous.

The Antecedent of a Pronoun

Make sure the antecedent is evident and explicit whenever you use a pronoun in a sentence. You may want to replace the pronoun with the noun to eliminate any vagueness.

- After the production and the car’s mechanical inspection were complete, it was delivered to the owner.

In the above sentence, it is unclear what the pronoun “it” is referring to.

- After the production and the car’s mechanical inspection was complete, the car was delivered to the owner.

Use of First Person Pronouns (I, We) in Academic Writing

The use of first-person pronouns, such as “I” and “We”, is a widely debated topic in academic writing.

While some style guides, such as ‘APA” and “Harvard”, encourage first-person pronouns when describing the author’s actions, many other style guides discourage their use in academic writing to keep the attention to the information presented within rather than who describes it.

Similarly, you will find some leniency towards the use of first-person pronouns in some academic disciplines, while others strictly prohibit using them to maintain an impartial and neutral tone.

It will be fair to say that first-person pronouns are increasingly regular in many forms of academic writing. If ever in doubt whether or not you should use first-person pronouns in your essay or assignment, speak with your tutor to be entirely sure.

Avoid overusing first-person pronouns in academic papers regardless of the style guide used. It is recommended to use them only where required for improving the clarity of the text.

If you are writing about a situation involving only yourself or if you are the sole author of the paper, then use the singular pronouns (I, my). Use plural pronouns (We, They, Our) when there are coauthors to work.

| Use the first person | Examples |

|---|---|

| To signal your position on the topic or make a claim different to what the opposition says. | In this research study, I have argued that First, I have provided the essay outline We conclude that |

| To report steps, procedures, and methods undertaken. | I conducted research We performed the statistical analysis. |

| To organise and guide the reader through the text. | Our findings suggest that A is more significant than B, contrary to the claims made in the literature. However, I argue that. |

Avoiding First Person Pronouns

You can avoid first-person pronouns by employing any of the following three methods.

| Sentences including first-person pronouns | Improvement | Improved sentence |

|---|---|---|

| We conducted in-depth research. | Use the third person pronoun | The researchers conducted in-depth research. |

| I argue that the experimental results justify the hypothesis. | Change the subject | This study argues that the experimental results justify the hypothesis. |

| I performed statistical analysis of the dataset in SPSS. | Switch to passive voice | The dataset was statistically analysed in SPSS. |

There are advantages and disadvantages of each of these three strategies. For example, passive voice introduces dangling modifiers, which can make your text unclear and ambiguous. Therefore, it would be best to keep first-person pronouns in the text if you can use them.

In some forms of academic writing, such as a personal statement and reflective essay, it is completely acceptable to use first-person pronouns.

The Problem with the Editorial We

Avoid using the first person plural to refer to people in academic text, known as the “editorial we”. The use of the “editorial we” is quite common in newspapers when the author speaks on behalf of the people to express a shared experience or view.

Refrain from using broad generalizations in academic text. You have to be crystal clear and very specific about who you are making reference to. Use nouns in place of pronouns where possible.

- When we tested the data, we found that the hypothesis to be incorrect.

- When the researchers tested the data, they found the hypothesis to be incorrect.

- As we started to work on the project, we realized how complex the requirements were.

- As the students started to work on the project, they realized how complex the requirements were.

If you are talking on behalf of a specific group you belong to, then the use of “we” is acceptable.

- It is essential to be aware of our own

- It is essential for essayists to be aware of their own weaknesses.

- Essayists need to be aware of their own

Use of Second Person Pronouns (You) in Academic Writing

It is strictly prohibited to use the second-person pronoun “you” to address the audience in any form of academic writing. You can rephrase the sentence or introduce the impersonal pronoun “one” to avoid second-person pronouns in the text.

- To achieve the highest academic grade, you must avoid procrastination.

- To achieve the highest academic grade, one must avoid procrastination.

- As you can notice in below Table 2.1, all participants selected the first option.

- As shown in below Table 2.1, all participants selected the first option.

Use of Third Person Pronouns (He, She, They) in Academic Writing

Third-person pronouns in the English language are usually gendered (She/Her, He/Him). Educational institutes worldwide are increasingly advocating for gender-neutral language, so you should avoid using third-person pronouns in academic text.

In the older academic text, you will see gender-based nouns (Fishermen, Traitor) and pronouns (him, her, he, she) being commonly used. However, this style of writing is outdated and warned against in the present times.

You may also see some authors using both masculine and feminine pronouns, such as “he” or “she”, in the same text, but this generally results in unclear and inappropriate sentences.

Considering using gender-neutral pronouns, such as “they”, ‘there”, “them” for unknown people and undetermined people. The use of “they” in academic writing is highly encouraged. Many style guides, including Harvard, MLA, and APA, now endorse gender natural pronouns in academic writing.

On the other hand, you can also choose to avoid using pronouns altogether by either revising the sentence structure or pluralizing the sentence’s subject.

- When a student is asked to write an essay, he can take a specific position on the topic.

- When a student is asked to write an essay, they can take a specific position on the topic.

- When students are asked to write an essay, they are expected to take a specific position on the topic.

- Students are expected to take a specific position on the essay topic.

- The writer submitted his work for approval

- The writer submitted their work for approval.

- The writers submitted their work for approval.

- The writers’ work was submitted for approval.

Make sure it is clear who you are referring to with the singular “they” pronoun. You may want to rewrite the sentence or name the subject directly if the pronoun makes the sentence ambiguous.

For example, in the following example, you can see it is unclear who the plural pronoun “they” is referring to. To avoid confusion, the subject is named directly, and the context approves that “their paper” addresses the writer.

- If the writer doesn’t complete the client’s paper in time, they will be frustrated.

- The client will be frustrated if the writer doesn’t complete their paper in due time.

If you need to make reference to a specific person, it would be better to address them using self-identified pronouns. For example, in the following sentence, you can see that each person is referred to using a different possessive pronoun.

The students described their experience with different academic projects: Mike talked about his essay, James talked about their poster presentation, and Sara talked about her dissertation paper.

Ensure Consistency Throughout the Text

Avoid switching back and forth between first-person pronouns (I, We, Our) and third-person pronouns (The writers, the students) in a single piece. It is vitally important to maintain consistency throughout the text.

For example, The writers completed the work in due time, and our content quality is well above the standard expected. We completed the work in due time, and our content quality is well above the standard expected. The writers completed the work in due time, and the content quality is well above the standard expected.“

How to Use Demonstrative Pronouns (This, That, Those, These) in Academic Writing

Make sure it is clear who you are referring to when using demonstrative pronouns. Consider placing a descriptive word or phrase after the demonstrative pronouns to give more clarity to the sentence.

For example, The political relationship between Israel and Arab states has continued to worsen over the last few decades, contrary to the expectations of enthusiasts in the regional political sphere. This shows that a lot more needs to be done to tackle this. The political relationship between Israel and Arab states has continued to worsen over the last few decades, contrary to the expectations of enthusiasts in the regional political sphere. This situation shows that a lot more needs to be done to tackle this issue.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the 8 types of pronouns.

The 8 types of pronouns are:

- Personal: Refers to specific persons.

- Demonstrative: Points to specific things.

- Interrogative: Used for questioning.

- Possessive: Shows ownership.

- Reflexive: Reflects the subject.

- Reciprocal: Indicates mutual action.

- Relative: Introduces relative clauses.

- Indefinite: Refers vaguely or generally.

You May Also Like

Parentheses enclose additional information in a sentence that is not necessary for the sentence to make sense. This article explains the rules of parentheses with examples.

This article describes misplaced modifiers and how to fix them, and also provides an insight into ambiguous modifiers and adverb placement.

This articles provides information on the order of adjectives in a string of adjectives that feels intuitive to native English speakers, but not to the non-native English speakers.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Nouns and pronouns

- First-Person Pronouns | List, Examples & Explanation

First-Person Pronouns | List, Examples & Explanation

Published on October 17, 2022 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 4, 2023.

First-person pronouns are words such as “I” and “us” that refer either to the person who said or wrote them (singular), or to a group including the speaker or writer (plural). Like second- and third-person pronouns , they are a type of personal pronoun .

They’re used without any issue in everyday speech and writing, but there’s an ongoing debate about whether they should be used in academic writing .

There are four types of first-person pronouns—subject, object, possessive, and reflexive—each of which has a singular and a plural form. They’re shown in the table below and explained in more detail in the following sections.

| I | me | mine | myself | |

| we | us | ours | ourselves |

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

First-person subject pronouns (“i” and “we”), first-person object pronouns (“me” and “us”), first-person possessive pronouns (“mine” and “ours”), first-person reflexive pronouns (“myself” and “ourselves”), first-person pronouns in academic writing, other interesting language articles, frequently asked questions.

Used as the subject of a verb , the first-person subject pronoun takes the form I (singular) or we (plural). Note that unlike all other pronouns, “I” is invariably capitalized .

A subject is the person or thing that performs the action described by the verb. In most sentences, it appears at the start or after an introductory phrase, just before the verb it is the subject of.

To be honest, we haven’t made much progress.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Used as the object of a verb or preposition , the first-person object pronoun takes the form me (singular) or us (plural). Objects can be direct or indirect, but the object pronoun should be used in both cases.

- A direct object is the person or thing that is acted upon (e.g., “she threatened us ”).

- An indirect object is the person or thing that benefits from that action (e.g., “Jane gave me a gift”).

- An object pronoun should also be used after a preposition (e.g., “come with me ”).

It makes no difference to me .

Will they tell us where to go?

First-person possessive pronouns are used to represent something that belongs to you. They are mine (singular) and ours (plural).

They are closely related to the first-person possessive determiners my (singular) and our (plural). The difference is that determiners must modify a noun (e.g., “ my book”), while pronouns stand on their own (e.g., “that one is mine ”).

It was a close game, but in the end, victory was ours .

A reflexive pronoun is used instead of an object pronoun when the object of the sentence is the same as the subject. The first-person reflexive pronouns are myself (singular) and ourselves (plural). They occur with reflexive verbs, which describe someone acting upon themselves (e.g., “I wash myself ”).

The same words can also be used as intensive pronouns , in which case they place greater emphasis on the person carrying out the action (e.g., “I’ll do it myself ”).

Check for common mistakes

Use the best grammar checker available to check for common mistakes in your text.

Fix mistakes for free

While first-person pronouns are used without any problem in most contexts, there’s an ongoing debate about their use in academic writing . They have traditionally been avoided in many academic disciplines for two main reasons:

- To maintain an objective tone

- To keep the focus on the material and not the author

However, the first person is increasingly standard in many types of academic writing. Some style guides, such as APA , require the use of first-person pronouns (and determiners) when referring to your own actions and opinions. The tendency varies based on your field of study:

- The natural sciences and other STEM fields (e.g., medicine, biology, engineering) tend to avoid first-person pronouns, although they accept them more than they used to.

- The social sciences and humanities fields (e.g., sociology, philosophy, literary studies) tend to allow first-person pronouns.

Avoiding first-person pronouns

If you do need to avoid using first-person pronouns (and determiners ) in your writing, there are three main techniques for doing so.

| First-person sentence | Technique | Revised sentence |

|---|---|---|

| We 12 participants. | Use the third person | The researchers interviewed 12 participants. |

| I argue that the theory needs to be refined further. | Use a different subject | This paper argues that the theory needs to be refined further. |

| I checked the dataset for and . | Use the | The dataset was checked for missing data and outliers. |

Each technique has different advantages and disadvantages. For example, the passive voice can sometimes result in dangling modifiers that make your text less clear. If you are allowed to use first-person pronouns, retaining them is the best choice.

Using first-person pronouns appropriately

If you’re allowed to use the first person, you still shouldn’t overuse it. First-person pronouns (and determiners ) are used for specific purposes in academic writing.

| Use the first person … | Examples |

|---|---|

| To organize the text and guide the reader through your argument | argue that … outline the development of … conclude that … |

| To report methods, procedures, and steps undertaken | analyzed … interviewed … |

| To signal your position in a debate or contrast your claims with another source | findings suggest that … contend that … |

Avoid arbitrarily inserting your own thoughts and feelings in a way that seems overly subjective and adds nothing to your argument:

- In my opinion, …

- I think that …

- I dislike …

Pronoun consistency

Whether you may or may not refer to yourself in the first person, it’s important to maintain a consistent point of view throughout your text. Don’t shift between the first person (“I,” “we”) and the third person (“the author,” “the researchers”) within your text.

- The researchers interviewed 12 participants, and our results show that all were in agreement.

- We interviewed 12 participants, and our results show that all were in agreement.

- The researchers interviewed 12 participants, and the results show that all were in agreement.

The editorial “we”

Regardless of whether you’re allowed to use the first person in your writing, you should avoid the editorial “we.” This is the use of plural first-person pronouns (or determiners) such as “we” to make a generalization about people. This usage is regarded as overly vague and informal.

Broad generalizations should be avoided, and any generalizations you do need to make should be expressed in a different way, usually with third-person plural pronouns (or occasionally the impersonal pronoun “one”). You also shouldn’t use the second-person pronoun “you” for generalizations.

- When we are given more freedom, we can work more effectively.

- When employees are given more freedom, they can work more effectively.

- As we age, we tend to become less concerned with others’ opinions of us .

- As people age, they tend to become less concerned with others’ opinions of them .

If you want to know more about nouns , pronouns , verbs , and other parts of speech , make sure to check out some of our other language articles with explanations and examples.

Nouns & pronouns

- Common nouns

- Collective nouns

- Personal pronouns

- Proper nouns

- Second-person pronouns

- Verb tenses

- Phrasal verbs

- Types of verbs

- Active vs passive voice

- Subject-verb agreement

- Interjections

- Conjunctions

- Prepositions

Yes, the personal pronoun we and the related pronouns us , ours , and ourselves are all first-person. These are the first-person plural pronouns (and our is the first-person plural possessive determiner ).

If you’ve been told not to refer to yourself in the first person in your academic writing , this means you should also avoid the first-person plural terms above . Switching from “I” to “we” is not a way of avoiding the first person, and it’s illogical if you’re writing alone.

If you need to avoid first-person pronouns , you can instead use the passive voice or refer to yourself in the third person as “the author” or “the researcher.”

Personal pronouns are words like “he,” “me,” and “yourselves” that refer to the person you’re addressing, to other people or things, or to yourself. Like other pronouns, they usually stand in for previously mentioned nouns (antecedents).

They are called “personal” not because they always refer to people (e.g., “it” doesn’t) but because they indicate grammatical person ( first , second , or third person). Personal pronouns also change their forms based on number, gender, and grammatical role in a sentence.

In grammar, person is how we distinguish between the speaker or writer (first person), the person being addressed (second person), and any other people, objects, ideas, etc. referred to (third person).

Person is expressed through the different personal pronouns , such as “I” ( first-person pronoun ), “you” ( second-person pronoun ), and “they” (third-person pronoun). It also affects how verbs are conjugated, due to subject-verb agreement (e.g., “I am” vs. “you are”).

In fiction, a first-person narrative is one written directly from the perspective of the protagonist . A third-person narrative describes the protagonist from the perspective of a separate narrator. A second-person narrative (very rare) addresses the reader as if they were the protagonist.

Sources in this article

We strongly encourage students to use sources in their work. You can cite our article (APA Style) or take a deep dive into the articles below.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 04). First-Person Pronouns | List, Examples & Explanation. Scribbr. Retrieved October 8, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-writing/first-person-pronouns/

Aarts, B. (2011). Oxford modern English grammar . Oxford University Press.

Butterfield, J. (Ed.). (2015). Fowler’s dictionary of modern English usage (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Garner, B. A. (2016). Garner’s modern English usage (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, what is a pronoun | definition, types & examples, active vs. passive constructions | when to use the passive voice, second-person pronouns | list, examples & explanation, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

First-Person Pronouns

Use first-person pronouns in APA Style to describe your work as well as your personal reactions.

- If you are writing a paper by yourself, use the pronoun “I” to refer to yourself.

- If you are writing a paper with coauthors, use the pronoun “we” to refer yourself and your coauthors together.

Referring to yourself in the third person

Do not use the third person to refer to yourself. Writers are often tempted to do this as a way to sound more formal or scholarly; however, it can create ambiguity for readers about whether you or someone else performed an action.

Correct: I explored treatments for social anxiety.

Incorrect: The author explored treatments for social anxiety.

First-person pronouns are covered in the seventh edition APA Style manuals in the Publication Manual Section 4.16 and the Concise Guide Section 2.16

Editorial “we”

Also avoid the editorial “we” to refer to people in general.

Incorrect: We often worry about what other people think of us.

Instead, specify the meaning of “we”—do you mean other people in general, other people of your age, other students, other psychologists, other nurses, or some other group? The previous sentence can be clarified as follows:

Correct: As young adults, we often worry about what other people think of us. I explored my own experience of social anxiety...

When you use the first person to describe your own actions, readers clearly understand when you are writing about your own work and reactions versus those of other researchers.

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

Can You Use I or We in a Research Paper?

4-minute read

- 11th July 2023

Writing in the first person, or using I and we pronouns, has traditionally been frowned upon in academic writing . But despite this long-standing norm, writing in the first person isn’t actually prohibited. In fact, it’s becoming more acceptable – even in research papers.

If you’re wondering whether you can use I (or we ) in your research paper, you should check with your institution first and foremost. Many schools have rules regarding first-person use. If it’s up to you, though, we still recommend some guidelines. Check out our tips below!

When Is It Most Acceptable to Write in the First Person?

Certain sections of your paper are more conducive to writing in the first person. Typically, the first person makes sense in the abstract, introduction, discussion, and conclusion sections. You should still limit your use of I and we , though, or your essay may start to sound like a personal narrative .

Using first-person pronouns is most useful and acceptable in the following circumstances.

When doing so removes the passive voice and adds flow

Sometimes, writers have to bend over backward just to avoid using the first person, often producing clunky sentences and a lot of passive voice constructions. The first person can remedy this. For example:

Both sentences are fine, but the second one flows better and is easier to read.

When doing so differentiates between your research and other literature

When discussing literature from other researchers and authors, you might be comparing it with your own findings or hypotheses . Using the first person can help clarify that you are engaging in such a comparison. For example:

In the first sentence, using “the author” to avoid the first person creates ambiguity. The second sentence prevents misinterpretation.

When doing so allows you to express your interest in the subject

In some instances, you may need to provide background for why you’re researching your topic. This information may include your personal interest in or experience with the subject, both of which are easier to express using first-person pronouns. For example:

Expressing personal experiences and viewpoints isn’t always a good idea in research papers. When it’s appropriate to do so, though, just make sure you don’t overuse the first person.

When to Avoid Writing in the First Person

It’s usually a good idea to stick to the third person in the methods and results sections of your research paper. Additionally, be careful not to use the first person when:

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

● It makes your findings seem like personal observations rather than factual results.

● It removes objectivity and implies that the writing may be biased .

● It appears in phrases such as I think or I believe , which can weaken your writing.

Keeping Your Writing Formal and Objective

Using the first person while maintaining a formal tone can be tricky, but keeping a few tips in mind can help you strike a balance. The important thing is to make sure the tone isn’t too conversational.

To achieve this, avoid referring to the readers, such as with the second-person you . Use we and us only when referring to yourself and the other authors/researchers involved in the paper, not the audience.

It’s becoming more acceptable in the academic world to use first-person pronouns such as we and I in research papers. But make sure you check with your instructor or institution first because they may have strict rules regarding this practice.

If you do decide to use the first person, make sure you do so effectively by following the tips we’ve laid out in this guide. And once you’ve written a draft, send us a copy! Our expert proofreaders and editors will be happy to check your grammar, spelling, word choice, references, tone, and more. Submit a 500-word sample today!

Is it ever acceptable to use I or we in a research paper?

In some instances, using first-person pronouns can help you to establish credibility, add clarity, and make the writing easier to read.

How can I avoid using I in my writing?

Writing in the passive voice can help you to avoid using the first person.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

5-minute read

Free Email Newsletter Template

Promoting a brand means sharing valuable insights to connect more deeply with your audience, and...

6-minute read

How to Write a Nonprofit Grant Proposal

If you’re seeking funding to support your charitable endeavors as a nonprofit organization, you’ll need...

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Using “I” in Academic Writing

Traditionally, some fields have frowned on the use of the first-person singular in an academic essay and others have encouraged that use, and both the frowning and the encouraging persist today—and there are good reasons for both positions (see “Should I”).

I recommend that you not look on the question of using “I” in an academic paper as a matter of a rule to follow, as part of a political agenda (see webb), or even as the need to create a strategy to avoid falling into Scylla-or-Charybdis error. Let the first-person singular be, instead, a tool that you take out when you think it’s needed and that you leave in the toolbox when you think it’s not.

Examples of When “I” May Be Needed

- You are narrating how you made a discovery, and the process of your discovering is important or at the very least entertaining.

- You are describing how you teach something and how your students have responded or respond.

- You disagree with another scholar and want to stress that you are not waving the banner of absolute truth.

- You need “I” for rhetorical effect, to be clear, simple, or direct.

Examples of When “I” Should Be Given a Rest

- It’s off-putting to readers, generally, when “I” appears too often. You may not feel one bit modest, but remember the advice of Benjamin Franklin, still excellent, on the wisdom of preserving the semblance of modesty when your purpose is to convince others.

- You are the author of your paper, so if an opinion is expressed in it, it is usually clear that this opinion is yours. You don’t have to add a phrase like, “I believe” or “it seems to me.”

Works Cited

Franklin, Benjamin. The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin . Project Gutenberg , 28 Dec. 2006, www.gutenberg.org/app/uploads/sites/3/20203/20203-h/20203-h.htm#I.

“Should I Use “I”?” The Writing Center at UNC—Chapel Hill , writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/should-i-use-i/.

webb, Christine. “The Use of the First Person in Academic Writing: Objectivity, Language, and Gatekeeping.” ResearchGate , July 1992, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1992.tb01974.x.

J.S.Beniwal 05 August 2017 AT 09:08 AM

I have borrowed MLA only yesterday, did my MAEnglish in May 2017.MLA is of immense help for scholars.An overview of the book really enlightened me.I should have read it at bachelor's degree level.

Your e-mail address will not be published

Dr. Raymond Harter 25 September 2017 AT 02:09 PM

I discourage the use of "I" in essays for undergraduates to reinforce a conversational tone and to "self-recognize" the writer as an authority or at least a thorough researcher. Writing a play is different than an essay with a purpose.

Osayimwense Osa 22 March 2023 AT 05:03 PM

When a student or writer is strongly and passionately interested in his or her stance and argument to persuade his or her audience, the use of personal pronoun srenghtens his or her passion for the subject. This passion should be clear in his/her expression. However, I encourage the use of the first-person, I, sparingly -- only when and where absolutely necessary.

Eleanor 25 March 2023 AT 04:03 PM

I once had a student use the word "eye" when writing about how to use pronouns. Her peers did not catch it. I made comments, but I think she never understood what eye was saying!

Join the Conversation

We invite you to comment on this post and exchange ideas with other site visitors. Comments are moderated and subject to terms of service.

If you have a question for the MLA's editors, submit it to Ask the MLA!

Should I Use “I”?

What this handout is about.

This handout is about determining when to use first person pronouns (“I”, “we,” “me,” “us,” “my,” and “our”) and personal experience in academic writing. “First person” and “personal experience” might sound like two ways of saying the same thing, but first person and personal experience can work in very different ways in your writing. You might choose to use “I” but not make any reference to your individual experiences in a particular paper. Or you might include a brief description of an experience that could help illustrate a point you’re making without ever using the word “I.” So whether or not you should use first person and personal experience are really two separate questions, both of which this handout addresses. It also offers some alternatives if you decide that either “I” or personal experience isn’t appropriate for your project. If you’ve decided that you do want to use one of them, this handout offers some ideas about how to do so effectively, because in many cases using one or the other might strengthen your writing.

Expectations about academic writing

Students often arrive at college with strict lists of writing rules in mind. Often these are rather strict lists of absolutes, including rules both stated and unstated:

- Each essay should have exactly five paragraphs.

- Don’t begin a sentence with “and” or “because.”

- Never include personal opinion.

- Never use “I” in essays.

We get these ideas primarily from teachers and other students. Often these ideas are derived from good advice but have been turned into unnecessarily strict rules in our minds. The problem is that overly strict rules about writing can prevent us, as writers, from being flexible enough to learn to adapt to the writing styles of different fields, ranging from the sciences to the humanities, and different kinds of writing projects, ranging from reviews to research.

So when it suits your purpose as a scholar, you will probably need to break some of the old rules, particularly the rules that prohibit first person pronouns and personal experience. Although there are certainly some instructors who think that these rules should be followed (so it is a good idea to ask directly), many instructors in all kinds of fields are finding reason to depart from these rules. Avoiding “I” can lead to awkwardness and vagueness, whereas using it in your writing can improve style and clarity. Using personal experience, when relevant, can add concreteness and even authority to writing that might otherwise be vague and impersonal. Because college writing situations vary widely in terms of stylistic conventions, tone, audience, and purpose, the trick is deciphering the conventions of your writing context and determining how your purpose and audience affect the way you write. The rest of this handout is devoted to strategies for figuring out when to use “I” and personal experience.

Effective uses of “I”:

In many cases, using the first person pronoun can improve your writing, by offering the following benefits:

- Assertiveness: In some cases you might wish to emphasize agency (who is doing what), as for instance if you need to point out how valuable your particular project is to an academic discipline or to claim your unique perspective or argument.

- Clarity: Because trying to avoid the first person can lead to awkward constructions and vagueness, using the first person can improve your writing style.

- Positioning yourself in the essay: In some projects, you need to explain how your research or ideas build on or depart from the work of others, in which case you’ll need to say “I,” “we,” “my,” or “our”; if you wish to claim some kind of authority on the topic, first person may help you do so.

Deciding whether “I” will help your style

Here is an example of how using the first person can make the writing clearer and more assertive:

Original example:

In studying American popular culture of the 1980s, the question of to what degree materialism was a major characteristic of the cultural milieu was explored.

Better example using first person:

In our study of American popular culture of the 1980s, we explored the degree to which materialism characterized the cultural milieu.

The original example sounds less emphatic and direct than the revised version; using “I” allows the writers to avoid the convoluted construction of the original and clarifies who did what.

Here is an example in which alternatives to the first person would be more appropriate:

As I observed the communication styles of first-year Carolina women, I noticed frequent use of non-verbal cues.

Better example:

A study of the communication styles of first-year Carolina women revealed frequent use of non-verbal cues.

In the original example, using the first person grounds the experience heavily in the writer’s subjective, individual perspective, but the writer’s purpose is to describe a phenomenon that is in fact objective or independent of that perspective. Avoiding the first person here creates the desired impression of an observed phenomenon that could be reproduced and also creates a stronger, clearer statement.

Here’s another example in which an alternative to first person works better:

As I was reading this study of medieval village life, I noticed that social class tended to be clearly defined.

This study of medieval village life reveals that social class tended to be clearly defined.

Although you may run across instructors who find the casual style of the original example refreshing, they are probably rare. The revised version sounds more academic and renders the statement more assertive and direct.

Here’s a final example:

I think that Aristotle’s ethical arguments are logical and readily applicable to contemporary cases, or at least it seems that way to me.

Better example

Aristotle’s ethical arguments are logical and readily applicable to contemporary cases.

In this example, there is no real need to announce that that statement about Aristotle is your thought; this is your paper, so readers will assume that the ideas in it are yours.

Determining whether to use “I” according to the conventions of the academic field

Which fields allow “I”?

The rules for this are changing, so it’s always best to ask your instructor if you’re not sure about using first person. But here are some general guidelines.

Sciences: In the past, scientific writers avoided the use of “I” because scientists often view the first person as interfering with the impression of objectivity and impersonality they are seeking to create. But conventions seem to be changing in some cases—for instance, when a scientific writer is describing a project she is working on or positioning that project within the existing research on the topic. Check with your science instructor to find out whether it’s o.k. to use “I” in their class.

Social Sciences: Some social scientists try to avoid “I” for the same reasons that other scientists do. But first person is becoming more commonly accepted, especially when the writer is describing their project or perspective.

Humanities: Ask your instructor whether you should use “I.” The purpose of writing in the humanities is generally to offer your own analysis of language, ideas, or a work of art. Writers in these fields tend to value assertiveness and to emphasize agency (who’s doing what), so the first person is often—but not always—appropriate. Sometimes writers use the first person in a less effective way, preceding an assertion with “I think,” “I feel,” or “I believe” as if such a phrase could replace a real defense of an argument. While your audience is generally interested in your perspective in the humanities fields, readers do expect you to fully argue, support, and illustrate your assertions. Personal belief or opinion is generally not sufficient in itself; you will need evidence of some kind to convince your reader.

Other writing situations: If you’re writing a speech, use of the first and even the second person (“you”) is generally encouraged because these personal pronouns can create a desirable sense of connection between speaker and listener and can contribute to the sense that the speaker is sincere and involved in the issue. If you’re writing a resume, though, avoid the first person; describe your experience, education, and skills without using a personal pronoun (for example, under “Experience” you might write “Volunteered as a peer counselor”).

A note on the second person “you”:

In situations where your intention is to sound conversational and friendly because it suits your purpose, as it does in this handout intended to offer helpful advice, or in a letter or speech, “you” might help to create just the sense of familiarity you’re after. But in most academic writing situations, “you” sounds overly conversational, as for instance in a claim like “when you read the poem ‘The Wasteland,’ you feel a sense of emptiness.” In this case, the “you” sounds overly conversational. The statement would read better as “The poem ‘The Wasteland’ creates a sense of emptiness.” Academic writers almost always use alternatives to the second person pronoun, such as “one,” “the reader,” or “people.”

Personal experience in academic writing

The question of whether personal experience has a place in academic writing depends on context and purpose. In papers that seek to analyze an objective principle or data as in science papers, or in papers for a field that explicitly tries to minimize the effect of the researcher’s presence such as anthropology, personal experience would probably distract from your purpose. But sometimes you might need to explicitly situate your position as researcher in relation to your subject of study. Or if your purpose is to present your individual response to a work of art, to offer examples of how an idea or theory might apply to life, or to use experience as evidence or a demonstration of an abstract principle, personal experience might have a legitimate role to play in your academic writing. Using personal experience effectively usually means keeping it in the service of your argument, as opposed to letting it become an end in itself or take over the paper.

It’s also usually best to keep your real or hypothetical stories brief, but they can strengthen arguments in need of concrete illustrations or even just a little more vitality.

Here are some examples of effective ways to incorporate personal experience in academic writing:

- Anecdotes: In some cases, brief examples of experiences you’ve had or witnessed may serve as useful illustrations of a point you’re arguing or a theory you’re evaluating. For instance, in philosophical arguments, writers often use a real or hypothetical situation to illustrate abstract ideas and principles.

- References to your own experience can explain your interest in an issue or even help to establish your authority on a topic.

- Some specific writing situations, such as application essays, explicitly call for discussion of personal experience.

Here are some suggestions about including personal experience in writing for specific fields:

Philosophy: In philosophical writing, your purpose is generally to reconstruct or evaluate an existing argument, and/or to generate your own. Sometimes, doing this effectively may involve offering a hypothetical example or an illustration. In these cases, you might find that inventing or recounting a scenario that you’ve experienced or witnessed could help demonstrate your point. Personal experience can play a very useful role in your philosophy papers, as long as you always explain to the reader how the experience is related to your argument. (See our handout on writing in philosophy for more information.)

Religion: Religion courses might seem like a place where personal experience would be welcomed. But most religion courses take a cultural, historical, or textual approach, and these generally require objectivity and impersonality. So although you probably have very strong beliefs or powerful experiences in this area that might motivate your interest in the field, they shouldn’t supplant scholarly analysis. But ask your instructor, as it is possible that they are interested in your personal experiences with religion, especially in less formal assignments such as response papers. (See our handout on writing in religious studies for more information.)

Literature, Music, Fine Arts, and Film: Writing projects in these fields can sometimes benefit from the inclusion of personal experience, as long as it isn’t tangential. For instance, your annoyance over your roommate’s habits might not add much to an analysis of “Citizen Kane.” However, if you’re writing about Ridley Scott’s treatment of relationships between women in the movie “Thelma and Louise,” some reference your own observations about these relationships might be relevant if it adds to your analysis of the film. Personal experience can be especially appropriate in a response paper, or in any kind of assignment that asks about your experience of the work as a reader or viewer. Some film and literature scholars are interested in how a film or literary text is received by different audiences, so a discussion of how a particular viewer or reader experiences or identifies with the piece would probably be appropriate. (See our handouts on writing about fiction , art history , and drama for more information.)

Women’s Studies: Women’s Studies classes tend to be taught from a feminist perspective, a perspective which is generally interested in the ways in which individuals experience gender roles. So personal experience can often serve as evidence for your analytical and argumentative papers in this field. This field is also one in which you might be asked to keep a journal, a kind of writing that requires you to apply theoretical concepts to your experiences.

History: If you’re analyzing a historical period or issue, personal experience is less likely to advance your purpose of objectivity. However, some kinds of historical scholarship do involve the exploration of personal histories. So although you might not be referencing your own experience, you might very well be discussing other people’s experiences as illustrations of their historical contexts. (See our handout on writing in history for more information.)

Sciences: Because the primary purpose is to study data and fixed principles in an objective way, personal experience is less likely to have a place in this kind of writing. Often, as in a lab report, your goal is to describe observations in such a way that a reader could duplicate the experiment, so the less extra information, the better. Of course, if you’re working in the social sciences, case studies—accounts of the personal experiences of other people—are a crucial part of your scholarship. (See our handout on writing in the sciences for more information.)

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

APA Style: Writing & Citation

- Voice and Tense

- Clarity of Language

First vs Third Person Pronouns

Editorial "we", singular "they".

- Avoiding Bias

- Periods, Commas, and Semicolons

- APA Citation Examples

- Using Generative AI in Papers & Projects

Need Help? Virtual Chat with a Librarian

You Can Also:

Research Help Appointments are one-on-one sessions with a librarian.

APA recommends avoiding the use of the third person when referring to your self as the primary investigator or author. Use the personal pronoun I or we when referring to steps in an experiment. (see page 120, 4.16 in the APA 7th Edition Manual)

Correct: We assessed the vality of the experiment design with a literature review.

Incorrect: The authors assessed the vality of the experiment with a literature review.

Avoid the use of the editorial or universal we. The use of we can be confusing because it is not clear to the reader who you are referring to in your research. Substitute the word we with a noun, such as researchers, nurses, or students. Limit the use of the word we to refer to yourself and your coauthors. (See page 120 4.17 in the APA 7th edition manual)

Correct: Humans experience the world as a spectrum of sights, sounds, and smells.

Incorrect: We experience the world as a spectrum of sights, sounds, and smells .

The Singular "They" refers to a generic third-person singular pronoun. APA is promoting the use of the singular "they" as a way of being more inclusive and to avoid assumptions about gender. Many advocacy groups and publishers are now supporting it.

Observe the following guidelines when addressing issues surrounding third-person pronouns:

- Always use a person's self identified pronoun.

- Use "they" to refer to a person whose gender is not known.

- Do not use a combination forms, such as "(s)he" and "s/he."

- Reword a sentence to avoid using a pronoun, if the gender is not known.

- You can use the forms of THEY such as them, their, theirs, and themselves.

- << Previous: Clarity of Language

- Next: Numbers >>

- Last Updated: Sep 23, 2024 8:11 AM

- URL: https://libguides.gvltec.edu/apawriting

We Vs. They: Using the First & Third Person in Research Papers

Writing in the first , second , or third person is referred to as the author’s point of view . When we write, our tendency is to personalize the text by writing in the first person . That is, we use pronouns such as “I” and “we”. This is acceptable when writing personal information, a journal, or a book. However, it is not common in academic writing.

Some writers find the use of first , second , or third person point of view a bit confusing while writing research papers. Since second person is avoided while writing in academic or scientific papers, the main confusion remains within first or third person.

In the following sections, we will discuss the usage and examples of the first , second , and third person point of view.

First Person Pronouns

The first person point of view simply means that we use the pronouns that refer to ourselves in the text. These are as follows:

Can we use I or We In the Scientific Paper?

Using these, we present the information based on what “we” found. In science and mathematics, this point of view is rarely used. It is often considered to be somewhat self-serving and arrogant . It is important to remember that when writing your research results, the focus of the communication is the research and not the persons who conducted the research. When you want to persuade the reader, it is best to avoid personal pronouns in academic writing even when it is personal opinion from the authors of the study. In addition to sounding somewhat arrogant, the strength of your findings might be underestimated.

For example:

Based on my results, I concluded that A and B did not equal to C.

In this example, the entire meaning of the research could be misconstrued. The results discussed are not those of the author ; they are generated from the experiment. To refer to the results in this context is incorrect and should be avoided. To make it more appropriate, the above sentence can be revised as follows:

Based on the results of the assay, A and B did not equal to C.

Second Person Pronouns

The second person point of view uses pronouns that refer to the reader. These are as follows:

This point of view is usually used in the context of providing instructions or advice , such as in “how to” manuals or recipe books. The reason behind using the second person is to engage the reader.

You will want to buy a turkey that is large enough to feed your extended family. Before cooking it, you must wash it first thoroughly with cold water.

Although this is a good technique for giving instructions, it is not appropriate in academic or scientific writing.

Third Person Pronouns

The third person point of view uses both proper nouns, such as a person’s name, and pronouns that refer to individuals or groups (e.g., doctors, researchers) but not directly to the reader. The ones that refer to individuals are as follows:

- Hers (possessive form)

- His (possessive form)

- Its (possessive form)

- One’s (possessive form)

The third person point of view that refers to groups include the following:

- Their (possessive form)

- Theirs (plural possessive form)

Everyone at the convention was interested in what Dr. Johnson presented. The instructors decided that the students should help pay for lab supplies. The researchers determined that there was not enough sample material to conduct the assay.

The third person point of view is generally used in scientific papers but, at times, the format can be difficult. We use indefinite pronouns to refer back to the subject but must avoid using masculine or feminine terminology. For example:

A researcher must ensure that he has enough material for his experiment. The nurse must ensure that she has a large enough blood sample for her assay.

Many authors attempt to resolve this issue by using “he or she” or “him or her,” but this gets cumbersome and too many of these can distract the reader. For example:

A researcher must ensure that he or she has enough material for his or her experiment. The nurse must ensure that he or she has a large enough blood sample for his or her assay.

These issues can easily be resolved by making the subjects plural as follows:

Researchers must ensure that they have enough material for their experiment. Nurses must ensure that they have large enough blood samples for their assay.

Exceptions to the Rules

As mentioned earlier, the third person is generally used in scientific writing, but the rules are not quite as stringent anymore. It is now acceptable to use both the first and third person pronouns in some contexts, but this is still under controversy.

In a February 2011 blog on Eloquent Science , Professor David M. Schultz presented several opinions on whether the author viewpoints differed. However, there appeared to be no consensus. Some believed that the old rules should stand to avoid subjectivity, while others believed that if the facts were valid, it didn’t matter which point of view was used.

First or Third Person: What Do The Journals Say

In general, it is acceptable in to use the first person point of view in abstracts, introductions, discussions, and conclusions, in some journals. Even then, avoid using “I” in these sections. Instead, use “we” to refer to the group of researchers that were part of the study. The third person point of view is used for writing methods and results sections. Consistency is the key and switching from one point of view to another within sections of a manuscript can be distracting and is discouraged. It is best to always check your author guidelines for that particular journal. Once that is done, make sure your manuscript is free from the above-mentioned or any other grammatical error.

You are the only researcher involved in your thesis project. You want to avoid using the first person point of view throughout, but there are no other researchers on the project so the pronoun “we” would not be appropriate. What do you do and why? Please let us know your thoughts in the comments section below.

I am writing the history of an engineering company for which I worked. How do I relate a significant incident that involved me?

Hi Roger, Thank you for your question. If you are narrating the history for the company that you worked at, you would have to refer to it from an employee’s perspective (third person). If you are writing the history as an account of your experiences with the company (including the significant incident), you could refer to yourself as ”I” or ”My.” (first person) You could go through other articles related to language and grammar on Enago Academy’s website https://enago.com/academy/ to help you with your document drafting. Did you get a chance to install our free Mobile App? https://www.enago.com/academy/mobile-app/ . Make sure you subscribe to our weekly newsletter: https://www.enago.com/academy/subscribe-now/ .

Good day , i am writing a research paper and m y setting is a company . is it ethical to put the name of the company in the research paper . i the management has allowed me to conduct my research in thir company .

thanks docarlene diaz

Generally authors do not mention the names of the organization separately within the research paper. The name of the educational institution the researcher or the PhD student is working in needs to be mentioned along with the name in the list of authors. However, if the research has been carried out in a company, it might not be mandatory to mention the name after the name in the list of authors. You can check with the author guidelines of your target journal and if needed confirm with the editor of the journal. Also check with the mangement of the company whether they want the name of the company to be mentioned in the research paper.

Finishing up my dissertation the information is clear and concise.

How to write the right first person pronoun if there is a single researcher? Thanks

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

- Reporting Research

- Industry News

- Publishing Research

- AI in Academia

- Promoting Research

- Career Corner

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Infographics

- Expert Video Library

- Other Resources

- Enago Learn

- Upcoming & On-Demand Webinars

- Peer Review Week 2024

- Open Access Week 2023

- Conference Videos

- Enago Report

- Journal Finder

- Enago Plagiarism & AI Grammar Check

- Editing Services

- Publication Support Services

- Research Impact

- Translation Services

- Publication solutions

- AI-Based Solutions

- Thought Leadership

- Call for Articles

- Call for Speakers

- Author Training

- Edit Profile

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

Which among these features would you prefer the most in a peer review assistant?

Welcome to the new OASIS website! We have academic skills, library skills, math and statistics support, and writing resources all together in one new home.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Scholarly Voice: Point of View

Personal pronouns are used to indicate point of view in most types of writing. Here are some common points of view:

- A paper using first-person point of view uses pronouns such as "I," "me," "we," and "us."

- A paper using second-person point of view uses the pronoun "you."

- A paper using third-person point of view uses pronouns such as "he," "she," "it," "they," "him," "her," "his," and "them."

In scholarly writing, first-person and third-person point of view are common, but second-person point of view is not. Read more about appropriate points of view on the following pages:

- First-Person Point of View

- Second-Person Point of View

Pronouns Video

- APA Formatting & Style: Pronouns (video transcript)

Related Resource

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Varying Sentence Structure

- Next Page: First-Person Point of View

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Cost of Attendance

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

How to Use Pronouns Effectively While Writing Research Papers?

Usage of Pronouns in an Article

- Smooth: For the smooth flow of writing, pronouns are a necessary tool. Any article, book, or academic paper needs pronouns. If pronouns are replaced by nouns everywhere in a piece of writing, its readability would decrease, making it clumsy for the reader. However, the correct usage of pronouns is also required for the proper understanding of a subject.

- Simple to Read: In academic writing, it is important to use the accurate pronoun with the correct noun in the correct place of the sentence. If the pronouns make an article complicated instead of simple to read, they have not been used effectively.

- Singular/Plural, Person: When the pronoun that substitutes a noun agrees with the number and person of that noun, the writing becomes more meaningful. Here, the number implies whether the noun is singular or plural, and person implies whether the noun is in the first, second, or third person.

- Gender-Specific: Gender-specific pronouns bring clarity to the writing. If it is a feminine noun, the pronoun should be ‘she’, and for a masculine noun, it should be ‘he’. If the gender is not specified, both ‘he’ and ‘she’ should be used. In the case of plural nouns, ‘they’ should be used.

- Exceptions: Terms like ‘everyone’ and ‘everybody’ seem to be plural, but they carry singular pronouns. Singular pronouns are used for terms like ‘anybody’, ‘anyone’, ‘nobody’, ‘each’, and ‘someone’. These pronouns are also needed in academic writing.

Which Pronoun Should be Used Where?

- Personal Pronoun: If the author is writing from the first-person singular or plural point of view, then pronouns like ‘I’, ‘me’, ‘mine’, ‘my’, ‘we’, ‘our’, ‘ours’, and ‘us’ can be used. Academic writing considers these as personal pronouns. They make the author’s point of view and the results of the research immodest and opinionated. These pronouns should be avoided in academic writing as they understate the research findings. Authors must remember that their research and results should the focus, not themselves.

- First Person Plural Pronoun: Though sometimes ‘I’ can be used in the abstract, introduction, discussion, and conclusion sections, it should be avoided. It is advisable to use ‘we’ instead.

- Second Person Pronoun: The use of pronouns such as ‘you’, ‘your’, and ‘yours’ is also not appropriate in academic writing. They can be used to give instructions. It is better to use impersonal pronouns instead.

- Gender-Neutral Pronoun: Publications and study guides demand the writing to be gender-neutral which is why, either ‘s/he’ or ‘they’ is used.

- Demonstrative Pronoun: While using demonstrative pronouns such as this, that, these, or those, it should be clear who is being referred to.

Did the blog interest you? Would you like to read more blogs on services related to Manuscript editing? Visit our website https://www.manuscriptedit.com/scholar-hangout/ for more information. You can reach us at [email protected] . We will be waiting for your email!!!!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 02 January 2024

Behavioral consequences of second-person pronouns in written communications between authors and reviewers of scientific papers

- Zhuanlan Sun 1 na1 ,

- C. Clark Cao ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4908-9240 2 na1 ,

- Sheng Liu 2 na1 ,

- Yiwei Li ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5358-9320 2 &

- Chao Ma ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0078-6755 3

Nature Communications volume 15 , Article number: 152 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

27k Accesses

4 Citations

157 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

- Social sciences

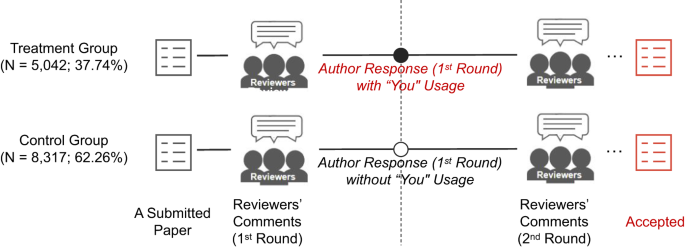

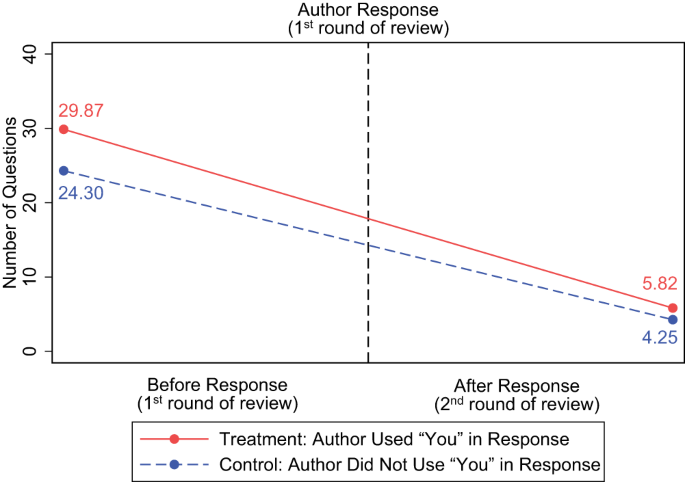

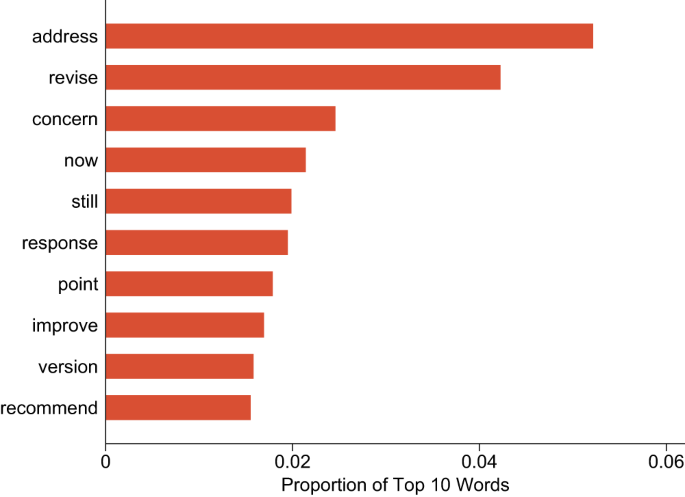

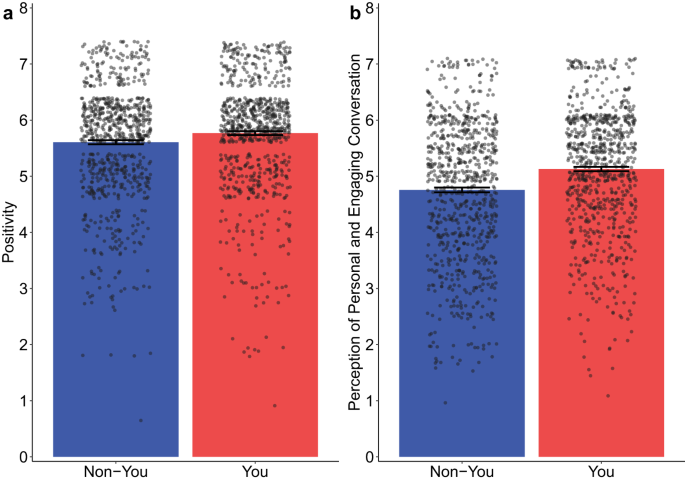

Pronoun usage’s psychological underpinning and behavioral consequence have fascinated researchers, with much research attention paid to second-person pronouns like “you,” “your,” and “yours.” While these pronouns’ effects are understood in many contexts, their role in bilateral, dynamic conversations (especially those outside of close relationships) remains less explored. This research attempts to bridge this gap by examining 25,679 instances of peer review correspondence with Nature Communications using the difference-in-differences method. Here we show that authors addressing reviewers using second-person pronouns receive fewer questions, shorter responses, and more positive feedback. Further analyses suggest that this shift in the review process occurs because “you” (vs. non-“you”) usage creates a more personal and engaging conversation. Employing the peer review process of scientific papers as a backdrop, this research reveals the behavioral and psychological effects that second-person pronouns have in interactive written communications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Demystifying the process of scholarly peer-review: an autoethnographic investigation of feedback literacy of two award-winning peer reviewers

A desire for distraction: uncovering the rates of media multitasking during online research studies

Cognitive reflection correlates with behavior on Twitter

Introduction.