Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Community Articles & More

Seven ways to find your purpose in life, having a meaningful, long-term goal is good for your well-being. here’s how to find one..

Many of the people I know seem to have a deep sense of purpose. Whether working for racial justice, teaching children to read, making inspiring art, or collecting donations of masks and face shields for hospitals during the pandemic, they’ve found ways to blend their passion, talents, and care for the world in a way that infuses their lives with meaning.

Luckily for them, having a purpose in life is associated with all kinds of benefits. Research suggests that purpose is tied to having better health , longevity , and even economic success . It feels good to have a sense of purpose, knowing that you are using your skills to help others in a way that matters to you.

But how do you go about finding your purpose if it’s not obvious to you? Is it something you develop naturally over the course of a lifetime ? Or are there steps you can take to encourage more purpose in your life?

Likely both, says Kendall Bronk , a researcher who directs the Adolescent Moral Development Lab at Claremont Graduate University. People can find a sense of purpose organically—or through deliberate exercises and self-reflection. Sometimes, just having someone talk to you about what matters to you makes you think more intentionally about your life and your purpose, says Bronk.

In her work with adolescents, she’s found that some teens find purpose after experiencing hardship. Maybe a kid who has experienced racism decides to become a civil rights advocate. Or one who’s suffered severe illness decides to study medicine. Of course, experiences like poverty and illness are extremely hard to overcome without help from others. But Bronk’s research suggests that having a supportive social network—caring family members, like-minded friends, or mentors, for example—helps youth to reframe hardship as a challenge they can play a role in changing for the better. That might be true of adults, too.

While hardship can lead to purpose, most people probably find purpose in a more meandering way, says Bronk—through a combination of education, experience, and self-reflection, often helped along by encouragement from others . But finding your purpose can be jump-started, too, given the right tools. She and her colleagues have found that exercises aimed at uncovering your values, interests, and skills, as well as practicing positive emotions like gratitude, can help point you toward your purpose in life.

Here are some of her recommendations based on her research on purpose.

1. Identify the things you care about

Purpose is all about applying your skills toward contributing to the greater good in a way that matters to you. So, identifying what you care about is an important first step.

In Greater Good’s Purpose Challenge , designed by Bronk and her team, high school seniors were asked to think about the world around them—their homes, communities, the world at large—and visualize what they would do if they had a magic wand and could change anything they wanted to change (and why). Afterward, they could use that reflection to consider more concrete steps they might take to contribute toward moving the world a little closer to that ideal.

A similar process is recommended for older adults by Jim Emerman of Encore.org, an organization that helps seniors find new purpose in life. Instead of envisioning an ideal future world, though, he suggests posing three questions to yourself:

- What are you good at?

- What have you done that gave you a skill that can be used for a cause?

- What do you care about in your community?

By reflecting on these questions, he says, older adults can brainstorm ideas for repurposing skills and pursuing interests developed over a lifetime toward helping the world.

2. Reflect on what matters most

Sometimes it can be hard to single out one or two things that matter most to you because your circle of care and concern is far-ranging. Understanding what you value most may help you narrow down your purpose in life to something manageable that also truly resonates with you.

There are several good values surveys to choose from, including these three recommended by PositivePsychology.com: the Valued Living Questionnaire , the Portrait Values Questionnaire , and the Personal Values Questionnaire . All have been used in research studies and may be helpful to those who feel overwhelmed by all they want to change.

Bronk found that helping people prioritize their values is useful for finding purpose. The survey used in Greater Good’s purpose challenge—where students were asked to look at common values and rank which were most important, least important, and in between—has been shown to be effective in helping people clarify their purpose.

Once you’re clearer on your deepest values, Bronk recommends asking yourself: What do these values say about you as a person? How do these values influence your daily life? How might they relate to what you want to do with the rest of your life? Doing this exercise can help you discover how you can put your values to use.

3. Recognize your strengths and talents

We all have strengths and skills that we’ve developed over our lifetimes, which help make up our unique personalities. Yet some of us may be unsure of what we have to offer.

If we need help, a survey like the VIA Character Strengths Survey can be useful in identifying our personal strengths and embracing them more fully. Then, you can take the results and think about how you can apply them toward something you really care about.

But it can also be helpful to ask others—teachers, friends, family, colleagues, mentors—for input. In the Purpose Challenge, students were asked to send emails to five people who knew them well and to pose questions like:

- What do you think I’m particularly good at?

- What do you think I really enjoy?

- How do you think I’ll leave my mark on the world?

Adults can do this if they need feedback, too—either formally or informally in conversation with trusted others. People who know you well may be able to see things in you that you don’t recognize in yourself, which can point you in unexpected directions. On the other hand, there is no need to overly rely on that feedback if it doesn’t resonate. Getting input is useful if it clarifies your strengths—not if it’s way off base.

4. Try volunteering

Finding purpose involves more than just self-reflection. According to Bronk, it’s also about trying out new things and seeing how those activities enable you to use your skills to make a meaningful difference in the world. Volunteering in a community organization focused on something of interest to you could provide you with some experience and do good at the same time.

Working with an organization serving others can put you in touch with people who share your passions and inspire you. In fact, it’s easier to find and sustain purpose with others’ support —and a do-gooder network can introduce you to opportunities and a community that shares your concern. Volunteering has the added benefit of improving our health and longevity, at least for some people.

However, not all volunteer activities will lead to a sense of purpose. “Sometimes volunteering can be deadening,” warns Stanford University researcher Anne Colby. “It needs to be engaging. You have to feel you’re accomplishing something.” When you find a good match for you, volunteering will likely “feel right” in some way—not draining, but invigorating.

5. Imagine your best possible self

This exercise if particularly useful in conjunction with the magic-wand exercise described above. In Greater Good’s Purpose Challenge, high school students were asked to imagine themselves at 40 years of age if everything had gone as well as it could have in their lives. Then, they answered questions, like:

- What are you doing?

- What is important to you?

- What do you really care about, and why?

The why part is particularly important, because purposes usually emerges from our reasons for caring, says Bronk.

Of course, those of us who are a bit older can still find these questions valuable. However, says Bronk, older folks may want to reflect back rather than look ahead. She suggests we think about what we’ve always wanted to do but maybe couldn’t because of other obligations (like raising kids or pursuing a career). There seems to be something about seeing what you truly want for yourself and the world that can help bring you closer to achieving it, perhaps by focusing your attention on the people and experiences you encounter that may help you get there.

6. Cultivate positive emotions like gratitude and awe

To find purpose, it helps to foster positive emotions , like awe and gratitude. That’s because each of these emotions is tied to well-being, caring about others, and finding meaning in life, which all help us focus on how we can contribute to the world.

More on Purpose

Discover how purpose changes across your lifetime .

Read how one millennial is finding purpose and connection in a pandemic.

Learn how to find your purpose in life .

Explore what purpose looks like for fathers.

In her study with young adults, Bronk found that practicing gratitude was particularly helpful in pointing students toward purpose. Reflecting on the blessings of their lives often leads young people to “ pay it forward ” in some way, which is how gratitude can lead to purpose.

There are many ways to cultivate awe and gratitude. Awe can be inspired by seeing the beauty in nature or recalling an inspirational moment . Gratitude can be practiced by keeping a gratitude journal or writing a gratitude letter to someone who helped you in life. Whatever tools you use, developing gratitude and awe has the added benefit of being good for your emotional well-being, which can give you the energy and motivation you need to carry out your purposeful goals.

7. Look to the people you admire

Sometimes the people we admire most in life give us a clue to how we might want to contribute to a better world ourselves. Reading about the work of civil rights leaders or climate activists can give us a moral uplift that can serve as motivation for working toward the greater good.

However, sometimes looking at these larger-than-life examples can be too intimidating , says Bronk. If so, you can look for everyday people who are doing good in smaller ways. Maybe you have a friend who volunteers to collect food for the homeless or a colleague whose work in promoting social justice inspires you.

You don’t need fame to fulfill your purpose in life. You just need to look to your inner compass—and start taking small steps in the direction that means the most to you.

This article is part of a GGSC initiative on “ Finding Purpose Across the Lifespan ,” supported by the John Templeton Foundation. In a series of articles, podcast episodes, and other resources, we’ll be exploring why and how to deepen your sense of purpose at different stages of life.

About the Author

Jill Suttie

Jill Suttie, Psy.D. , is Greater Good ’s former book review editor and now serves as a staff writer and contributing editor for the magazine. She received her doctorate of psychology from the University of San Francisco in 1998 and was a psychologist in private practice before coming to Greater Good .

You May Also Enjoy

This article — and everything on this site — is funded by readers like you.

Become a subscribing member today. Help us continue to bring “the science of a meaningful life” to you and to millions around the globe.

Advertisement

Purpose in Life: A Reconceptualization for Very Late Life

- Research Paper

- Published: 14 February 2022

- Volume 23 , pages 2337–2348, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Keith A. Anderson 1 ,

- Noelle L. Fields 1 ,

- Jessica Cassidy 1 &

- Lisa Peters-Beumer 2

668 Accesses

4 Citations

14 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

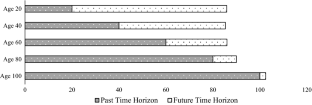

Purpose in life has been defined as having goals, aims, objectives, and a sense of directedness that give meaning to one’s life and existence. Scales that measure purpose in life reflect this future-oriented conceptualization and research using these measures has consistently found that purpose in life tends to be lower for older adults than for those in earlier stages of life. In this article, we use an illustrative case study to explore the concept of purpose in life in very late life and critically challenge existing conceptualizations and measures of purpose in life. We examine the two most commonly used measures of purpose in life, the Purpose in Life Test and the Ryff Purpose Subscale and identify specific items that should be reconsidered for use with older adults in very late life. Guided by Socioemotional Selectivity Theory, we then reconceptualize purpose in life in very late life and posit that it consists of three domains—the retrospective past, the near present, and the transcendental post-mortem. We conclude with suggestions on the development of new measures of purpose in life in very late life that are reflective of this shift in time horizons and the specific characteristics of this unique time in life.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price excludes VAT (USA) Tax calculation will be finalised during checkout.

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Health, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Quality of Life: What is the Difference?

Gratitude and subjective wellbeing: a proposal of two causal frameworks.

Application of the PERMA Model of Well-being in Undergraduate Students

Data availability.

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Ardelt, M. (2007). Wisdom, religiosity, purpose in life, and death attitudes of aging adults. In A. Tomer, G. T. Eliason, & T. P. Wong (Eds.), Existential and spiritual issues in death attitudes (pp. 139–158). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Google Scholar

Amaral, A. S., Afonso, R. M., Brandao, D., Teixeira, L., & Ribeiro, O. (2021). Resilience in very advanced ages: A study with Centenarians. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 93 (1), 601–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415020926839

Article Google Scholar

Araujo, L., Ribeiro, O., & Paul, C. (2017). The role of existential beliefs within the relation of centenarians’ health and well-being. Journal of Religion and Health, 56 , 1111–1122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-016-0297-5

Arosio, B., Ostan, R., Mari, D., Damanti, S., Ronchetti, F., Arcudi, S., Scurti, M., Franeschi, C., & Monti, D. (2017). Cognitive status in the oldest old and centenarians: A condition crucial for quality of life methodologically difficult to assess. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development, 165 , 185–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mad.2017.02.010

Baltes, P. B., Lindenberger, U., & Staudinger, U.M. (2006). Life-span theory in developmental psychology. In R.M. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology. Vol. 1: Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 569–664). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0111

Beker, N., Sikkes, S. A. M., Hulsman, M., Tesi, N., van der Lee, S. J., Scheltens, P., & Holstege, H. (2020). Longitudinal maintenance of cognitive health in centenarians in the 100-plus study. JAMA Network Open, 3 (2), e200094. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.0094

Bishop, A. (2011). Spirituality and religiosity connections to mental and physical health among the oldest old. In L. Poon & J. Cohen-Mansfield (Eds.), Understanding well-being in the oldest old (pp. 227–239). Cambridge University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Boyle, P. A., Barnes, L. L., Buchman, A. S., & Bennett, D. A. (2009). Purpose in life is associated with mortality among community-dwelling older persons. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71 (5), 574–579.

Boyle, P. A., Buchman, A. S., Barnes, L. L., & Bennett, D. A. (2010). Effect of a purpose in life on risk of incident Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older persons. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67 (3), 304–310.

Butler, R. N. (1963). The life review: An interpretation of reminiscence in the aged. Psychiatry, 26 (1), 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1963.11023339

Carstensen, L. L. (1991). Selectivity theory: Social activity in lifer-span context. In K. W. Schaie (Ed.), Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics (Vol. 11, pp. 195–217). Springer.

Carstensen, L. L. (1995). Evidence for a lifespan theory of socioemotional selectivity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 4 , 151–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep11512261

Carstensen, L. L. (2006). The influence of sense of time on human development. Science, 312 , 1913–1915. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1127488

Charles, S. T., Mather, M., & Carstensen, L. L. (2003). Aging and emotional memory: The forgettable nature of negative images for older adults. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 132 (2), 310–324. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.132.2.310

Cheng, A., Leung, Y., & Brodaty, H. (2021). A systematic review of the associations, mediators and moderators of life satisfaction, positive affect and happiness in near-centenarians and centenarians. Aging & Mental Health . https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1891197

Cheng, A., Leung, Y., Harrison, F., & Brodaty, H. (2019). The prevalence and predictors of anxiety and depression in near-centenarians and centenarians: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, 31 (11), 1539–1558. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610219000802

Chu, Q., Gruhn, D., & Holland, A. M. (2018). Before I die: The impact of time horizon and age on bucket-list goals. GeroPsych, 31 (3), 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1024/1662-9647/a000190

Crumbaugh, J. C., & Maholick, L. T. (1964). An experimental study in existentialism: The psychometric approach to Frankl’s concept of noogenic neurosis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 20 (2), 200–207. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679

Crumbaugh, J. C., & Maholick, L. T. (1969). Manual of instructions for the Purpose in Life Test . Viktor Frankl Institute of Logotherapy.

Damon, W., Menon, J., & Bronk, K. C. (2003). The development of purpose during adolescence. Applied Developmental Science, 7 , 119–128. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532480XADS0703_2

Duarte, N., Teixeira, L., Ribeiro, O., & Paul, C. (2014). Frailty phenotype criteria in centenarians: Findings from the Oporto Centenarian Study. European Geriatric Medicine, 5 (6), 371–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurger.2014.09.015

Erikson, E. H. (1982). The life cycle completed . W.W. Norton & Company.

Frankl, V. E. (1959). Man’s search for meaning . Pocket Books.

Hedberg, P., Brulin, C., & Aléx, L. (2009). Experiences of purpose in life when becoming and being a very old woman. Journal of Women and Aging, 21 (2), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952840902837145

Hedberg, P., Brulin, C., Aléx, L., & Gustafson, Y. (2011). Purpose in life over a five- year period: A longitudinal study among a very old population. International Psychogeriatrics, 23 (5), 806–813. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610210002279

Hedberg, P., Gustafson, Y., Aléx, L., & Brulin, C. (2010). Depression in relation to purpose in life among a very old population. A five-year follow-up study. Aging & Mental Health, 14 (6), 757–763. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607861003713216

Hedberg, P., Gustafson, Y., Brulin, C., & Aléx, L. (2013). Purpose in life among very old men. Advances in Aging Research, 2 (3), 100–105. https://doi.org/10.4236/aar.2013.23014

Herr, M., Jeune, B., Fors, S., Andersen-Ranberg, K., Ankri, J., Arai, Y., et al. (2018). Frailty and associated factors among centenarians in the 5-COOP countries. Gerontology, 64 (6), 521–531.

Hill, P. L., & Turiano, N. A. (2014). Purpose in life as a predictor of mortality across adulthood. Psychological Science, 25 (7), 1482–1486.

Irving, J., Davis, S., & Collier, A. (2017). Aging with purpose: Systematic search and review of literature pertaining to older adults and purpose. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 85 (4), 403–437. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415017702908

Jopp, D. S., Boerner, K., Ribeiro, O., & Rott, C. (2016a). Life at age 100: An international research agenda for centenarian studies. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 28 (3), 133–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2016.1161693

Jopp, D. S., Park, M.-K.S., Lehrfeld, J., & Paggi, M. E. (2016b). Physical, cognitive, social and mental health in near-centenarians and centenarians living in New York City: Findings from the Fordham Centenarian Study. BMC Geriatrics, 16 (1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0167-0

Kastbom, L., Milberg, A., & Karlsson, M. (2017). A good death from the perspective of palliative cancer patients. Journal of Supportive Care in Cancer, 25 , 933–939. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-016-3483-9

Kim, H., Theyer, B., & Munn, J. C. (2019). The relationship between perceived ageism and depressive symptoms in later life: Understanding the mediating effects of self-perception of aging and purpose in life using structural equation modeling. Educational Gerontology, 45 (2), 105–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2019.1583403

Kitayama, S., Berg, M. K., & Chopik, W. J. (2020). Culture and well-being in late adulthood: Theory and evidence. American Psychologist, 75 (4), 567. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000614

Krok, D. (2015). The role of meaning in life within the relations of religious coping and psychological well-being. Journal of Religion and Health, 54 , 2292–2308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-014-9983-3

Lewis, N. A., Turiano, N. A., Payne, B. R., & Hill, P. L. (2017). Purpose in life and cognitive functioning in adulthood. Neuropsychology, Development, and Cognition: Section b, Aging, Neuropsychology and Cognition, 24 (6), 662–671.

Martinson, M., & Berridge, C. (2015). Successful aging and its discontents: A systematic review of the social gerontology literature. The Gerontologist, 255 (1), 58–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu037

McKee, P. (2008). Plato’s theory of late life reminiscence. Journal of Aging, Humanities, and the Arts, 2 (3–4), 266–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/19325610802370720

Moreman, C. M. (2018). Beyond the threshold: Afterlife beliefs and experiences in the world religions . Rowman & Littlefield.

Musich, S., Wang, S. S., Kraemer, S., Hawkins, K., & Wicker, E. (2018). Purpose in life and positive health outcomes among older adults. Population Health Management, 21 (2), 139–147. https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2017.0063

Pew Research Center. (2014). Religious Landscape Study: Belief in heaven . https://www.pewforum.org/religious-landscape-study/belief-in-heaven/

Pinquart, M. (2002). Creating and maintaining purpose in life in old age: A meta-analysis. Ageing International, 27 (2), 90–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-002-1004-2

Reker, G. T., Peacock, E. J., & Wong, P. T. P. (1987). Meaning and purpose in life and well-being: A life span perspective. Journal of Gerontology, 42 (1), 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/42.1.44

Ribeiro, C. C., Yassuda, M. S., & Neri, A. L. (2020). Purpose in life in adulthood and older adulthood: Integrative review. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 25 (6), 2127–2142. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232020256.20602018

Rowe, J. W., & Kahn, R. L. (1997). Successful aging. The Gerontologist, 37 , 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/37.4.433

Ryff, C. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57 , 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Ryff, C. D. (2014). Psychological well-being revisited: Advances in science and practice. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83 (1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1159/000353263

Ryff, C., & Keyes, C. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69 , 719–727. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719

Schulenberg, S. E., Schnetzer, L. W., & Buchanan, E. M. (2011). The purpose in life test-short form: Development and psychometric support. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12 , 861–876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9231-9

Shaffer, J. (2021). Centenarians, supercentenarians: We must develop new measurements suitable for our oldest old. Frontiers in Psychology, 12 , 655497. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.655497

Social Security Administration. (2021). Retirement & survivors’ benefits: Life expectancy calculator. https://www.ssa.gov/oact/population/longevity.html

Tam, W., Poon, S. N., Mahendran, R., Kua, E. H., & Wu, X. V. (2021). The effectiveness of reminiscence-based intervention on improving psychological well-being in cognitively intact older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103847

Tornstam, L. (1989). Gero-transcendence: A reformation of the disengagement theory. Aging, 1 (1), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03323876

Windsor, T. D., Curtis, R. G., & Luszcz, M. A. (2015). Sense of purpose as a psychological resource for aging well. Developmental Psychology, 51 (7), 975–986.

Xu, X., Zhao, Y., Xia, S., Cui, P., Tang, W., Hu, X., & Wu, B. (2020). Quality of life and its influencing factors among centenarians in Nanjing, China: A cross sectional study. Social Indication Research . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02399-4

Yalom, I. (2008). Staring at the sun: Overcoming the terror of death. Humanistic Psychologist, 36 , 283–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2018.1432735

Yang, J. A., Wilhelmi, B. L., & McGlynn, K. (2018). Enhancing meaning when facing later life losses. Clinical Gerontologist, 41 (5), 498–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2018.1432735

Download references

This study did not receive funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Social Work, University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, TX, USA

Keith A. Anderson, Noelle L. Fields & Jessica Cassidy

Center for Gerontology, Concordia University Chicago, River Forest, IL, USA

Lisa Peters-Beumer

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization and writing of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Keith A. Anderson .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest or competing interests.

Ethical Approval

Consent to participate, consent for publication, additional information, publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Anderson, K.A., Fields, N.L., Cassidy, J. et al. Purpose in Life: A Reconceptualization for Very Late Life. J Happiness Stud 23 , 2337–2348 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00512-7

Download citation

Accepted : 08 February 2022

Published : 14 February 2022

Issue Date : June 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00512-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Purpose in life

- Very late life

- Socioemotional selectivity theory

- Centenarians

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Hello, you are using a very old browser that's not supported. Please, consider updating your browser to a newer version.

Templeton.org is in English. Only a few pages are translated into other languages.

Usted está viendo Templeton.org en español. Tenga en cuenta que solamente hemos traducido algunas páginas a su idioma. El resto permanecen en inglés.

Você está vendo Templeton.org em Português. Apenas algumas páginas do site são traduzidas para o seu idioma. As páginas restantes são apenas em Inglês.

أنت تشاهد Templeton.org باللغة العربية. تتم ترجمة بعض صفحات الموقع فقط إلى لغتك. الصفحات المتبقية هي باللغة الإنجليزية فقط.

Templeton Prize

- Learn About Sir John Templeton

- Our Mission

- Explore Funding Areas

- Character Virtue Development

- Individual Freedom & Free Markets

- Life Sciences

- Mathematical & Physical Sciences

- Public Engagement

- Religion, Science, and Society

- Apply for Grant

- About Our Grants

- Grant Calendar

- Grant Database

- Templeton Ideas

Affiliated Programs

Templeton Press

Humble Approach Initiative

Reviewing six decades of research into the meaning, development, and benefits of purpose in life

Modern scientific research on human purpose has its origins in, of all places, a Holocaust survivor’s experiences in a series of Nazi concentration camps. While a prisoner at Theresienstadt, Auschwitz and two satellite camps of Dachau, Viennese psychologist Viktor Frankl noticed that fellow prisoners who had a sense of purpose showed greater resilience to the torture, slave labor, and starvation rations to which they were subjected. Writing of his experience later, he found a partial explanation in a quote from Friedrich Nietzsche, “Those who have a ‘why’ to live, can bear almost any ‘how.’” Frankl’s 1959 book Man’s Search for Meaning , a book which proved to be seminal in the field, crystallized his convictions about the crucial role of meaning and purpose. A decade later, Frankl would assist in the development of the first and most widely used standardized survey of purpose, the 21-item “Purpose in Life” test.

As part of its ongoing interest in increasing understanding of character and virtue, the John Templeton Foundation commissioned a review of more than six decades of the literature surrounding the nature of human purpose. Covering more than 120 publications tracing back to Frankl’s work, the review examines six core questions relating to the definition, measurement, benefits, and development of purpose.

Psychology of Purpose: What Is Purpose and How Do You Measure It?

In psychological terms, a consensus definition for purpose has emerged in the literature according to which purpose is a stable and generalized intention to accomplish something that is at once personally meaningful and at the same time leads to productive engagement with some aspect of the world beyond the self. Not all goals or personally meaningful experiences contribute to purpose, but in the intersection of goal orientation, personal meaningfulness, and a focus beyond the self, a distinct conception of purpose emerges.

Studies and surveys investigating individual sources of purpose in life cite examples ranging from personal experience (being inspired by a caring teacher) to concerns affairs far removed from our current circumstance (becoming an activist after learning about sweatshop conditions in another country). Most world religions, as well as many secular systems of thought, also offer their adherents well-developed guidelines for developing purpose in life. Love of friends and family, and desire for meaningful work are common sources of purpose.

Over the past few decades, psychologists and sociologists have developed a host of assessments that touch on people’s senses of purpose including the Life Regard Index, the Purpose in Life subscale of the Psychological Scales of Well-being, the Meaning in Life questionnaire, the Existence Subscale of the Purpose in Life Test, the Revised Youth Purpose Survey, the Claremont Purpose Scale and the Life Purpose Questionnaire, among others.

The conclusion that emerges from work these tests and surveys, interviews, definitions, and meta-analyses is, roughly, that Frankl’s observation was correct — having a purpose in life is associated with a tremendous number of benefits, ranging from a subjective sense of happiness to lower levels of stress hormones. A 2004 study found that highly purposeful older women had lower cholesterol, were less likely to be overweight, and had lower levels of inflammatory response, while another from 2010 found that individuals who reported higher purpose scores were less likely to be diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment and even Alzheimer’s Disease. The vast majority of those noted benefits, however, are currently only correlations — in many cases it is not clear whether having a strong sense of purpose in life causes the benefits or whether people experiencing the benefits are simply better positioned to develop a sense of purpose.

Psychology of Purpose: Interventions

Potential interventions to increase purpose and its benefits have focused on the formative years of late youth, where studies have looked at the benefits of supportive mentors and of practices such as gratitude journaling on purpose in life. A 2009 study followed 89 children and adolescents who were assigned to write and deliver gratitude letters to people they felt had blessed them. Participants who had lower initial levels of positive affect and gratitude, compared to a control group, had significantly higher gratitude and positive affect after delivering the letter for as long as two months later.

This result becomes even more promising in light of a series of four studies in 2014 which concluded that even inducing a temporary purpose-mindset improved academic outcomes, including self-regulation, persistence, grade point average, and the amount of time students were willing to spend studying for tests and completing homework.

Psychology of Purpose: The Arc of Purpose

About one in five high school students and one in three college students report having a clear purpose in life. Those rates drop slightly into midlife and more precipitously into later adulthood. Some of these changes make sense in light of the future-oriented nature of purpose. For young people from late childhood onward, a sense of searching for a purpose is associated with a sense of life satisfaction — but only until middle age, when unending purpose-seeking may carry connotations of immaturity. One study, however, explored an interesting exception to the general decline of purpose-seeking: compared to other adults, “9-enders” (individuals ending a decade of life, at ages 29, 39, 49, etc.) tend to focus more on aging and meaning, and consequently, they are more likely to report searching for purpose or experiencing a crisis of meaning.

In mid-life, parenting and other forms of caregiving become a clear source of purpose and meaning for many. Interestingly, studies in 2006 and 1989 showed that, although parents had a stronger sense of meaning in their lives than non-parents, they reported feeling less happy — a reflection of the ways that pursuing one’s purpose, especially in highly demanding seasons, can still be difficult, discouraging, and stressful.

A sense of purpose in one’s career is correlated with both greater satisfaction at work as well as better work-related outputs. In a 2001 study of service workers, researchers indicated that some hospital cleaning staff considered themselves “mere janitors” while others thought of themselves as part of the overall team that brought healing to patients. These groups of individuals performed the same basic tasks, but they thought very differently about their sense of purpose in the organizations where they worked. Not surprisingly, the workers who viewed their role as having a healing function were more satisfied with their jobs, spent more time with patients, worked more closely with doctors and nurses, and found more meaning in their jobs.

In the later stages of life, common adult sources of purpose like fulfillment in one’s career or caregiving for others are less accessible — but maintaining a strong sense of purpose is associated with a host of positive attributes at these ages. Compared to others, older adults with purpose are more likely to be employed, have better health, have a higher level of education, and be married.

Psychology of Purpose Around the Globe

Although the majority of sociological work on purpose in life has focused on people in western, affluent societies, the literature contains a few interesting cross-cultural results that hint at how approaches to and benefits from purpose in life might differ around the world. In Korea, for instance, youth were shown to view purpose as less an individual pursuit and more as a collective matter, while explorations of Chinese concepts of purpose indicates that one’s sense of purpose is divided into senses of professional, moral, and social purpose.

Research in the psychology of purpose among people of different socioeconomic backgrounds suggests that those in challenging circumstances are likely to have a difficult time discovering and pursuing personally meaningful aims. This finding fit well with psychologist A.H. Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs, which suggests that people must meet basic needs for things like food, shelter, and safety before they are easily motivated to pursue aims like self-actualization.

However several studies also suggest that purpose can emerge in difficult circumstances and that it may serve as an important form of protection, as in a study that showed that having a sense of life purpose buffered African-American youth from the negative experiences associated with growing up in more challenging environments.

Indeed, as Viktor Frankl argued — based in part on what he had observed first-hand — experiencing adversity might actually contribute to the development of a purpose in life.

STILL CURIOUS?

Download the full research review on the psychology of purpose.

Discover our other research papers on discoveries. Explore topics such as:

- intellectual humility

- positive neuroscience

- benefits of forgiveness

- science of free will

- science of generosity

Q&A with Samuel Wilkinson, author of Purpose: What Evolution and Human Nature Imply About the Meaning of our Existence

The pursuit of meaningful work, happiness at half moon bay.

Cookies enable our site to work correctly. By accepting these cookies, you help us ensure that we deliver a secure, functioning and accessible website. Some areas of our site may not function correctly without cookies. Cookie policy

Accept All Accept All

Share on Mastodon

Colorado State University

Vice president for research.

The psychology of purpose in life

- July 13, 2021

My mama always told me that miracles happen every day. Some people don’t think so, but they do.

—Forrest Gump

The human mind is one of the most fascinating things in the universe; it can understand its environment, it can solve the toughest problems, and it can create its own reality. However, there are a few age-old questions that the majority of people have grappled with at some point in their lives: Why am I here? What is the meaning of life? What is my purpose? These questions have been explored through a variety of avenues such as religion, music, art, and philosophy. But does meaning in life always have to be about the grand questions, or can it be something else? First, what is “meaning in life?”

Meaning in life can be difficult to define as it may be a highly personal experience. Researchers have defined meaning in life as a feeling that one’s life is significant, purposeful, and coherent; in other words, having a direction that makes sense and has a feeling of worth. From where one derives meaning is directly tied to values. Your values are beliefs of what is important, and they serve as guiding principles to your actions. Understanding how your individual values fit into your life and the world around you provides a sense of meaning.

An individual may find meaning in various domains of life, including work, relationships, hobbies, and interests. Researchers actually consider meaning in life as a core component to living a successful and happy life. Having meaning in life has been associated with a wide range of benefits . For example, people who consider themselves to have higher levels of meaning in life are much happier in general. Living a meaningful life is associated with better health, greater achievement in life, and stronger personal relationships . Meaning in life is also associated with higher income . Overall, having meaning in life is a great thing! However, for those who are struggling to find meaning, we have some suggestions that could be helpful.

Ultimately, man should not ask what the meaning of his life is, but rather must recognize that it is he who is asked. In a word, each man is questioned by life; and he can only answer to life by answering for his own life; to life he can only respond by being responsible. —Viktor Frankl

Finding meaning is as subjective as can be, which can be a great thing! We can all derive meaning from very different places. For instance, some people may find a great deal of purpose by giving back to their community and volunteering for a greater cause . Others may find purpose by challenging themselves to do something they haven’t ever done, such as cooking new recipes or attempting a fitness goal. One of the best ways to find meaning is to spend quality time with your family, so invite them over for a delicious dinner! Even just writing down your thoughts in a journal and reflecting on your day can help you attain a strong sense of meaning. Whatever is important to you and aligns with your personal values can bring a deep sense of meaning. Remember, finding meaning does not have to be a complicated process, you can find it in the simplest of life’s joys.

The purpose of life is not to be happy. It is to be useful, to be honorable, to be compassionate, to have it make some difference that you have lived and lived well. —Ralph Waldo Emerson

Get Email Updates

Want to receive the Center for Healthy Aging newsletter?

Click the icon to subscribe and receive CHA updates.

Recent Posts:

The argument for prioritizing mental health as you age

Enhancing healthcare communication for LGBT+ inclusivity

Alcohol and medication: Safeguarding older adults’ health

About the authors.

Wenceslao (Wen) Martinez is a master’s student in the Translational Research on Aging and Chronic Disease Laboratory in CSU’s Department of Health and Exercise Science — and he finds a lot of purpose in doing science.

Allie Alayan is a Ph.D. student in Counseling Psychology at CSU. She finds purpose in researching how people find purpose in their lives.

Something is always happening at #CSUResearch

Located in the CSU Health and Medical Center 151 W. Lake Street 8021 Campus Delivery Fort Collins, CO 80523-8021 (970) 495-2528 Email: [email protected]

Apply to CSU | Contact CSU | Disclaimer | Equal Opportunity | Privacy Statement

© 2021 Colorado State University

10 Powerful Benefits of Living With Purpose

Wealth, health, longevity, and more..

Posted August 23, 2021 | Reviewed by Davia Sills

- What Is Motivation?

- Find a therapist near me

- Having a purpose in life could promote your physical health, mental health, and happiness.

- "Purpose" offers a variety of other benefits as well, including better sleep.

- A sense that your activities are worthwhile could be a key to healthy aging.

Do you have a purpose in life? The answer to that question might be a key to your health and happiness , according to an ever-increasing body of research.

The concept of "purpose in life" is sometimes abbreviated PIL by researchers. "PIL" is not at all a bitter pill, despite the negative connotations of "pill." In fact, the more I read about the many benefits of “purpose,” the more convinced I am of its importance to health and happiness as well as to a sense of your own unique identity . This blog will summarize recent key studies on the relationship between purpose and flourishing.

But what is “purpose in life,” exactly? To put it simply, “purpose” can mean a feeling that the things you do in life are worthwhile. When you have a sense of purpose, you feel that you’ve made a deliberate choice to act in accordance with your values and goals. It can work the other way around, too. Your PIL can lead to further goal-setting . Either way, your purpose gives you a sense of being in charge of your own life.

Your purpose does not need to be grandiose; it only needs to be something meaningful to you (and, obviously, not anti-social). Work. A hobby that you love. Devotion to someone you care about. Creative expression. Travel. Treating everyone you meet with kindness. Keeping up your house. Writing a video or book. Starting or expanding a business. Connecting with friends, colleagues, children, and grandchildren.

Whatever your purpose, you can reap a harvest of benefits.

Here, in brief, are 10 benefits that are highly correlated to having a purpose in life, according to recent research. Most studies cited in this blog involve people over 50; other studies suggest that identifying your purpose contributes to life satisfaction for younger people, too.

The first five benefits come from a 2019 survey by British researchers Andrew Steptoe and Daisy Fancourt of over 7,300 men and women aged 50 and older living in the United Kingdom. The average age of participants was 67, with an age range from 50 to 90.

1. Happiness

The researchers found that a sense of purpose promoted happiness and well-being among adults 50-90. “Happiness” included a range of positive feelings from pleasure to life satisfaction to the sense of contribution to a larger purpose.

2. Healthy habits

Older adults with a sense of purpose were more likely to practice healthy habits, according to the study. For example, participants with high rankings on PIL were more likely to exercise regularly, eat healthy foods, watch less TV, participate in the arts, and avoid sedentary behaviors. Along the same lines, a recent survey of more than 500 adult participants showed that those with a strong sense of purpose were more likely to engage in protective health behaviors during COVID isolation.

3. Stronger personal relationships

Higher ratings for the belief that life is worthwhile were correlated to the likelihood of having a life partner, less risk of divorce , more contact with friends, membership in various organizations, volunteering, and a greater number of close relationships. Not surprisingly, those with strong PIL also experienced less loneliness .

In addition to a wealth of benefits of purpose in life, PIL also brought wealth itself. Sense of purpose was associated with greater prosperity, including income, paid employment, and assets, even after taking baseline wealth into account.

High “Life is worthwhile” rankings were correlated with better self-rated health, a lower incidence of chronic illness , less chronic pain , lower incidence of depression , and higher functional fitness.

As if that weren’t enough, other studies have heaped more onto the already full plate of purpose benefits, including these:

6. Longevity

A study of almost 7,000 U.S. adults over 50 published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2019 concluded that individuals with stronger purpose in life had lower all-cause mortality. Having a purpose also decreased the chance of premature death. Even after controlling for such factors as depression and chronic illness, those with a low score on sense-of-purpose rankings were almost twice as likely to die during the four years of the study (2006-2010).

7. Better sleep

In a study of older adults, 428 Black and 397 White, researchers discovered that those with a higher level of meaning and purpose in life had better sleep quality. Moreover, they had fewer problems with sleep apnea and restless legs syndrome.

8. Reduced risk of Alzheimer's disease

In a seven-year study of more than 900 residents in senior housing facilities, researchers discovered that greater purpose in life was associated with a substantially lower rate of incidence of Alzheimer's disease (AD). Even when some study participants were afflicted with AD, higher levels of purpose in life seemed to have a protective effect on cognition , according to this follow-up study .

9. Better mental health

A small study of 77 people in treatment for addictions found that those who had a sense of existential purpose and meaning in life had fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety , as described here . This result jibes with the U.K. study above, which also discovered that PIL was correlated with fewer depressive symptoms.

10. Better heart health

Reviewing the data on heart health and purpose in life from 10 studies of 136,000 people, cardiologist Randy Cohen concluded that "people with a low sense of purpose... were more likely to have a stroke, heart attack, or coronary artery disease requiring a stent or bypass surgery." By contrast, those with a strong PIL had a 19 percent reduction in cardiovascular events. The research is described by Dr. Sanjay Gupta in this article .

The Power of Purpose: The "Why"

Why does a sense of purpose have so many benefits? I'd speculate that if you feel you have a mission in life, you will take better care of your health so you can accomplish that mission. But the positive effects of a sense of purpose may go deeper than that, even to the cellular level.

A stronger sense of purpose may counter the negative effects of the stress hormone cortisol, a hormone that can wreak havoc on numerous body systems. "Purpose" may undo the negative effects of stress, repairing the immune system, calming the heart rate, and lowering blood sugar.

Finding Purpose as You Age

"Purpose in life" may be even more important as we age. According to British researchers Steptoe and Fancourt, “Maintaining a sense that life is worthwhile may be particularly important at older ages when social and emotional ties often fragment, social engagement is reduced, and health problems may limit personal options.”

Defining your unique purpose can be a challenge. One simple way to help yourself is to write down a tentative statement of your purpose; try it on and revise it as you evolve. Other options: Construct a purpose from these six building blocks of self-knowledge here , or follow one of these nine paths to purpose here . Seeing a career counselor or therapist can also be extremely helpful.

Knowing your purpose strengthens your sense of self; it gives you a way to explain who you are both to other people and to yourself.

(c) Meg Selig, 2021. All rights reserved.

LinkedIn image: Krakenimages.com/Shutterstock. Facebook image: Tomoharu photography/Shutterstock

Steptoe, A. and Fancourt, D. "Leading a meaningful life at older ages and its relationship with social engagement, prosperity, health, biology, and time use." PNAS, January 22, 2019 116 (4) 1207-1212.

Alimujiang, A. et al. "Association Between Life Purpose and Mortality Among US Adults Older Than 50 Years." JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e194270. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.4270.

Gupta, S. "Purpose in Life is Good for Your Health." Dec. 7, 2015, Everyday Health .

Meg Selig is the author of Changepower! 37 Secrets to Habit Change Success .

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

7 Tips for Finding Your Purpose in Life

Discover What Brings You Fullfillment

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Carly Snyder, MD is a reproductive and perinatal psychiatrist who combines traditional psychiatry with integrative medicine-based treatments.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/carly-935717a415724b9b9c849c26fd0450ea.jpg)

Why Do You Need a Sense of Purpose?

Donate time, money, or talent, listen to feedback, surround yourself with positive people, start conversations with new people, explore your interests, consider injustices that bother you, discover what you love to do.

- How Do You Know You've Found Your Purpose?

A Word From Verywell

Finding your purpose in living is more than a cliché: Learning how to live your life with purpose can lead to a sense of control, satisfaction, and general contentment. Feeling like what you do is worthwhile is, arguably, a significant key to a happy life. But what this means is different for each person. This article touches on a few helpful strategies for finding and steering your rudder in a sometimes turbulent sea.

Only around 25% of American adults say they have a clear sense of what makes their lives meaningful, according to one analysis in The New York Times . Another 40% either claim neutrality on the subject or say they don't.

A 2010 study published in Applied Psychology found that individuals with high levels of eudemonic well-being—a sense of purpose and control control and a feeling like what you do is worthwhile—tend to live longer. Other researchers found that well-being might be protective for health maintenance. In that research, people with the strongest well-being were 30% less likely to die during the eight-and-a-half-year follow-up period.

There’s also research that links feeling as if you have a sense of purpose to positive health outcomes such as fewer strokes and heart attacks, better sleep, and a lower risk of dementia and disabilities.

A 2016 study published in the Journal of Research and Personality found that individuals who feel a sense of purpose make more money than individuals who feel as though their work lacks meaning .

So the good news is, you don’t have to choose between having wealth and living a meaningful life. You might find that the more purpose you feel, the more money you’ll earn.

With all of those benefits, finding purpose and meaning in your life is clearly central to fulfillment--but it's likely to take time and patience.

Press Play for Advice On Self-Advocacy

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast , featuring activist Erin Brockovich, shares tips on standing up for what’s right, taking care of yourself, and tackling things that seem impossible. Click below to listen now.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

The process requires plenty of self-reflection, listening to others, and finding where your passions lie. These seven strategies can help you reveal or find your purpose so you can begin living a more meaningful life.

Hero Images / Getty Images

If you can cultivate just one helpful habit in your search for purpose, it would be helping others.

Researchers at Florida State University and Stanford found that happiness and meaningfulness overlapped somewhat but were different: Happiness was linked to the person being a taker before a giver, whereas meaningfulness went along with being more of a giver than a taker. The givers in relationships reported having a purposeful life more often than takers did.

Altruistic behaviors could include volunteering for a nonprofit organization, donating money to causes you care about, or simply helping out the people around you on a day-to-day basis.

Whether you decide to spend two Saturdays a month serving meals in a soup kitchen, or you volunteer to drive your elderly neighbor to the grocery store once a week, doing something kind for others can make you feel as though your life has meaning.

It can be hard to recognize the things you feel passionate about sometimes. After all, you probably like to do many different things and the things you love to do may have become so ingrained in your life that you don’t realize how important those things are.

Fortunately, other people might be able to give you some insight. There’s a good chance you’re already displaying your passion and purpose to those around you without even realizing it.

You might choose to reach out to people and ask what reminds them of you or what they think of when you enter their mind. Or you might take note when someone pays you a compliment or makes an observation about you. Write those observations down and look for patterns.

Whether people think of you as “a great entertainer” or they say “you have a passion for helping the elderly,” hearing others say what they notice about you might reinforce some of the passions you’ve already been engaging in.

As the saying goes, you are the company you keep. What do you have in common with the people who you choose to be around?

Don’t think about co-workers or family members you feel obligated to see. Think about the people you choose to spend time with outside of work and outside of family functions.

The people you surround yourself with say something about you. If you’re surrounded by people who are making positive change, you might draw from their inspiration.

On the other hand, if the people around you are negative individuals who drag you down, you might want to make some changes. It’s hard to feel passionate and purposeful when you’re surrounded by people who aren’t interested in making positive contributions.

It’s easy to browse social media while you’re alone on the subway or sitting at a bar waiting for a friend. Resist that urge. Instead, take the time to talk to the people around you.

Ask them if they are working on any projects or what they like to do for fun. Talk to them about organizations with which they are involved or if they like to donate to any particular cause.

Even though striking up conversations with strangers may feel awkward at first , talking to people outside of your immediate social circle can open your eyes to activities, causes or career opportunities that you never even knew existed.

You might discover new activities to explore or different places to visit. And those activities might be key to helping you find your purpose.

Is there a topic that you are regularly talking about in a Facebook status update or in a Tweet? Are you regularly sharing articles about climate change or refugees?

Are there pictures on Instagram of you engaging in a particular activity over and over, such as gardening or performing?

Consider the conversations you enjoy holding with people the most when you’re meeting face-to-face. Do you like talking about history? Or do you prefer sharing the latest money-saving tips you discovered?

The things you like to talk about and the things you enjoy sharing on social media may reveal the things that give you purpose in life.

Many people have their pet causes or passion projects that surround an injustice in the world. Is there anything that makes you so deeply unhappy to think about that it bothers you to the core?

It might be animal welfare, a particular civil rights issue or childhood obesity organizations. Perhaps the idea of senior citizens spending the holidays alone makes you weepy or you think that substance abusers need more rehabilitation opportunities—the organizations are out there, and they need your help.

You don’t necessarily have to engage in your purpose full-time. You might find your career gives you the ability to afford to help a cause you feel passionate about. Or, you might find that you are able to donate time—as opposed to money—to give to a cause that you believe in.

On the other end of the spectrum, simply thinking about what you truly love to do can help you find your purpose as well.

Do you absolutely love musical theater? Your skills might be best put to use in a way that brings live performances to children who can benefit from exposure to the arts.

Is analyzing data something that you actually find fun? Any number of groups could find that skill to be an invaluable asset.

Consider what type of skills, talents, and passions you bring to the table. Then, brainstorm how you might turn your passion into something meaningful to you.

How Do You Know You've Found Your Purpose?

Like the notion of purpose itself, the answer to that is subjective--and there are as many signs that someone's found their purpose as there are people.

Perhaps you feel fully connected to the universe and that you know your place in it. Maybe you've found your meaning in religion. Or you sense a strong connection with others. The feeling might arise from activities that benefit others, such as volunteering.

Ultimately, you've likely found your purpose if you've stopped asking whether you have.

Finding your purpose isn’t something you can do in a few days, weeks, or months. It can be a lifelong journey , and you must do it only one step at a time.

You also might find that your purpose changes over time. Perhaps you liked working with animals in your youth, but now you want to join forces with a cause that fights human trafficking. Or, maybe you want to do both, being among the lucky who find more than one purpose to drive their lives.

Keep in mind your purpose doesn’t necessarily mean you have to change what you’re doing already. If you cut hair, you might decide your purpose in life is to help others feel beautiful.

If you work as a school custodian, you might find your purpose is creating an environment that helps children learn.

Occasionally, consider pausing what you’re doing to reflect on your path: Is it taking you in the direction you want to go? If not, you can change course. Sometimes, that road to finding your purpose has a few curves, forks, and stop lights.

Khullar D. Finding Purpose for a Good Life. But Also a Healthy One. The New York Times. The Upshot. Jan. 1, 2018:1. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/01/01/upshot/finding-purpose-for-a-good-life-but-also-a-healthy-one.html

Kobau, R, Sniezek, J, Zack, M M, Lucas, RE, Burns, A. Well‐Being Assessment: An Evaluation of Well‐Being Scales for Public Health and Population Estimates of Well‐Being among US Adults . Applied Psychology : 2010: 2: 272-297. doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2010.01035.x

Steptoe A, Deaton A, Stone AA. Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. Lancet . 2015;385(9968):640–648. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61489-0

Musich S, Wang SS, Kraemer S, Hawkins K, Wicker E. Purpose in Life and Positive Health Outcomes Among Older Adults. Popul Health Manag . 2018;21(2):139–147. doi:10.1089/pop.2017.0063

Schippers MC, Ziegler N. Life Crafting as a Way to Find Purpose and Meaning in Life. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2778. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02778

Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, Aaker JL, Garbinsky EN. Some key differences between a happy life and a meaningful life . The Journal of Positive Psychology . 2013;8(6):505-516. doi:10.1080/17439760.2013.830764

Son J. Wilson J. Volunteer Work and Hedonic, Eudemonic, and Social Well-Being. Sociological Forum. 2012;27(3):658-681. doi:10.1111/j.1573-7861.2012.01340.x

Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, Aaker JL, Garbinsky EN. Some key differences between a happy life and a meaningful life. Journal of Positive Psychology 2013;8(6):505-516. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.830764

- Hill PL, Turiano NA, Mroczek DK, Burrow AL. The value of a purposeful life: Sense of purpose predicts greater income and net worth . Journal of Research in Personality . 2016:65:38-42. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2016.07.003.

By Amy Morin, LCSW Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Your Health

- Treatments & Tests

- Health Inc.

- Public Health

What's Your Purpose? Finding A Sense Of Meaning In Life Is Linked To Health

Mara Gordon

Having a purpose in life, whether building guitars or swimming or volunteer work, affects your health, researchers found. It even appeared to be more important for decreasing risk of death than exercising regularly. Dean Mitchell/Getty Images hide caption

Having a purpose in life, whether building guitars or swimming or volunteer work, affects your health, researchers found. It even appeared to be more important for decreasing risk of death than exercising regularly.

Having a purpose in life may decrease your risk of dying early, according to a study published Friday.

Researchers analyzed data from nearly 7,000 American adults between the ages of 51 and 61 who filled out psychological questionnaires on the relationship between mortality and life purpose.

What they found shocked them, according to Celeste Leigh Pearce, one of the authors of the study published in JAMA Current Open .

People who didn't have a strong life purpose — which was defined as "a self-organizing life aim that stimulates goals" — were more likely to die than those who did, and specifically more likely to die of cardiovascular diseases.

"I approached this with a very skeptical eye," says Pearce , an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of Michigan. "I just find it so convincing that I'm developing a whole research program around it."

People without a strong life purpose were more than twice as likely to die between the study years of 2006 and 2010, compared with those who had one.

This association between a low level of purpose in life and death remained true despite how rich or poor participants were, and regardless of gender, race, or education level. The researchers also found the association to be so powerful that having a life purpose appeared to be more important for decreasing risk of death than drinking, smoking or exercising regularly.

"Just like people have basic physical needs, like to sleep and eat and drink, they have basic psychological needs," says Alan Rozanski , a professor at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai who was not involved in this research but has studied the relationship between life purpose and physical health.

"The need for meaning and purpose is No. 1," Rozanski adds. "It's the deepest driver of well-being there is."

The new study adds to a small but growing body of literature on the relationship between life purpose and physical health. Rozanski published a 2016 paper in the journal Psychosomatic Medicine , for example, that used data from 10 studies to show that strong life purpose was associated with reduced risk of mortality and cardiovascular events, such as heart attacks or stroke.

Study authors for the new JAMA Current Open study pulled data from a large survey of older American adults called the Health and Retirement Study . Participants were asked a variety of questions on topics such as finances, physical health and family life.

A subset of participants filled out psychological questionnaires, including a survey called the Psychological Wellbeing Scale , in 2006. This includes questions designed to understand how strong a person's sense of life purpose is. For example, it asks them to rate their responses to questions like, "Some people wander aimlessly through life, but I am not one of them."

The study authors used people's answers to these questions to quantify how powerful their degree of life purpose was. The researchers then compared that information to data on participants' physical health up until 2010, including whether or not participants died and what they died from.

The survey didn't ask participants to define how they find meaning in life. What matters, according to the researchers, is not exactly what a person's life purpose is, but that they have one.

"For some, it might be raising children. For others, it might be doing volunteer work," Pearce says. "Where your life fulfillment comes from can be very individual."

The study's lead author, Aliya Alimujiang , who is a doctoral student in epidemiology at the University of Michigan, says she got involved in the project because of a personal interest in mindfulness and wellness.

Before she started graduate school, Alimujiang worked as a volunteer in a breast cancer clinic and says she was struck by how the patients who could articulate how they found meaning in life seemed to do better.

That experience helped her define part of her own life purpose: researching the phenomenon.

"I had a really close relationship with the breast cancer patients. I saw the fear and anxiety and depression they had," Alimujiang says. "That helped me to apply for [graduate] school. That's how I started my career."

Pearce says that while the link between life purpose and physical well-being seems strong, more research is needed to explore the physiological connection between the two, like whether having a low life purpose is connected to high levels of stress hormones. She also hopes to study public health strategies — like types of therapy or educational tools — that might help people develop a strong sense of their life's work.

"What I'm really struck by is the strength of our findings, as well as the consistency in the literature overall," Pearce says. "It seems quite convincing."

- life purpose

15 Ways to Find Your Purpose of Life & Realize Your Meaning

“ You don’t find meaning; you create it ,” was my answer to the question, what is meaning?

Drawn in by the unforgiving directness of the existentialist philosophers, I was (perhaps naively) attempting to respond to the question that Albert Camus said must be answered before all others: Is there meaning in life ? Or, to state it more clearly: Is a life worth living? (Camus, 1975).

This article explores a few of the questions central to the vast and complex topic of meaning and purpose in life and introduces techniques and tools to help clients find answers.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Meaning and Valued Living Exercises for free . These creative, science-based exercises will help you learn more about your values, motivations, and goals and will give you the tools to inspire a sense of meaning in the lives of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

What is the purpose of life a philosophical and psychological take, how to find the purpose of your life, 10 techniques to help yourself and others, 4 useful worksheets, a note on finding meaning after trauma, divorce, and others, positivepsychology.com’s resources, a take-home message.

In The Myth of Sisyphus , Albert Camus (1975), when faced with what he saw as the meaninglessness of existence, suggested we live life to its fullest rather than attempt an escape.

For Camus, as with his contemporary Jean-Paul Sartre, existentialism concerns itself with the uniqueness of the human condition (Sartre, 1964). According to the existentialist formula, life has no inherent meaning. We have free choice and, therefore, choose our values and purpose.

But where did existentialism come from?

The sense of freedom that existentialism offers is crucial – jolting us out of a comfortable malaise. It builds on Friedrich Nietzsche’s thinking that there are no universal facts and that man is isolated. He is born, lives, and dies – alone (Nietzsche, 1911; Kaufmann, 1976).

Rather than dictating how the reader should live, Nietzsche tells us we should create our values and our sense of purpose.

And yet, if cast free, how do we create meaning and purpose?

Existentialism is indebted to Edmund Husserl’s work on perception to answer this and other questions. Writing in 1900, Husserl regards meaning, along with perception, as the creation of the individual. Meaning is not objective – to be found in the external world – but built up from our mental states (Warnock, 1970).

Martin Heidegger – often described as the first true existentialist – picks up on this idea in the heavy-weight Being and Time , written in 1927. For us to be authentic – following a state of anxiety born out of a realization that we are free – we must take responsibility for our actions, our purpose, and our meaning (Heidegger, 1927/2013).

Existentialism and the struggle for meaning

Sartre continues this line of thinking in Being and Nothingness (1964):

“…every man, without any support or help whatever, is condemned at every instant to invent man.”

Separate from the world, we must realize the horror that we are free to do and create meaning . And yet, to avoid bad faith (or inauthenticity), we must accept that we are responsible not only for ourselves but also for all people.

To the existentialist, our sense of meaning and purpose comes from what we do.

But can science and psychology help us find either? Yes, probably .

Meaning and psychology

Increasingly, psychologists have begun to realize the importance of meaning to our wellbeing and happiness.

Recent research suggests that people with increased meaning are better off – they appear happier, exhibit increased life satisfaction, and report lowered depression (Huo et al., 2019; Ivtzan, Lomas, Hefferon, & Worth, 2016; Steger, 2009).

Nevertheless, meaning is a complex construct that can be approached from multiple angles; for example, cognitively, appraising situations for meaning, and motivationally to pursue worthwhile goals (Eysenck & Keane, 2015; Ryan & Deci, 2018).

While there are many definitions of meaning in psychology, Laura King, a psychologist at the University of Missouri, provides us with the following useful description (Heintzelman & King, 2015):

Meaning in life “may be defined as the extent to which a person experiences his or her life as having purpose, significance, and coherence.”

Whether meaning is derived from thoughtful reflection or only as a byproduct of cognitive processing, it is vital for healthy mental functioning. After all, we only attach importance to an experience and see it as significant if it has meaning. Similarly, a sense of meaning and purpose is crucial to create an environment for pursuing personal goals.

A fascinating study in 2010 took a very different perspective, bringing us closer to our initial, philosophical discussion. The realization that there is only one certainty in life – death – can cause great anxiety for many.

The Terror Management Theory (TMT) suggests that features that remind us of our mortality are likely to heighten fear around death (Routledge & Juhl, 2010). However, TMT also suggests that a life “ imbued with meaning and purpose ” can help stave off such angst.

Philosophically and psychologically, it is clear that meaning is a fundamental component of our human existence.

Meaning refers to how we “ make sense of life and our roles in it ,” while purpose refers to the “ aspirations that motivate our activities ” (Ivtzan et al., 2016).

The terms are sufficiently close to saying that in the absence of either, our life lacks a story. As humans, we need something to strive for and a sense of connectedness between the important moments that make up our existence (Steger, 2009).

Sometimes, seeing the bigger picture or recognizing our place in the broader scheme can bring great insights and even play a role in our experience of meaning in life (Hicks & King, 2007).

Share the following ideas and insights with your clients:

Mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam

In 1990, astronomer Carl Sagan convinced NASA to spin the Voyager 1 Space Probe around to take one last look at Earth as the probe left the solar system. The picture it took was unlike any other before or since. Roughly 3.7 billion miles away and traveling at 40,000 miles per hour, it captured Earth as a small pale blue dot against a band of sunlight.

The image either leaves you with a sense of deep horror at our insignificance in a vast, uncaring universe or a sense of wonder at how we came into being in such a “ vast cosmic arena .”

This realization is captured beautifully in Carl Sagan’s words and this stunning computer simulation.

Broadening the mind