- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Table of Contents

Research Process

Definition:

Research Process is a systematic and structured approach that involves the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data or information to answer a specific research question or solve a particular problem.

Research Process Steps

Research Process Steps are as follows:

Identify the Research Question or Problem

This is the first step in the research process. It involves identifying a problem or question that needs to be addressed. The research question should be specific, relevant, and focused on a particular area of interest.

Conduct a Literature Review

Once the research question has been identified, the next step is to conduct a literature review. This involves reviewing existing research and literature on the topic to identify any gaps in knowledge or areas where further research is needed. A literature review helps to provide a theoretical framework for the research and also ensures that the research is not duplicating previous work.

Formulate a Hypothesis or Research Objectives

Based on the research question and literature review, the researcher can formulate a hypothesis or research objectives. A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested to determine its validity, while research objectives are specific goals that the researcher aims to achieve through the research.

Design a Research Plan and Methodology

This step involves designing a research plan and methodology that will enable the researcher to collect and analyze data to test the hypothesis or achieve the research objectives. The research plan should include details on the sample size, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques that will be used.

Collect and Analyze Data

This step involves collecting and analyzing data according to the research plan and methodology. Data can be collected through various methods, including surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. The data analysis process involves cleaning and organizing the data, applying statistical and analytical techniques to the data, and interpreting the results.

Interpret the Findings and Draw Conclusions

After analyzing the data, the researcher must interpret the findings and draw conclusions. This involves assessing the validity and reliability of the results and determining whether the hypothesis was supported or not. The researcher must also consider any limitations of the research and discuss the implications of the findings.

Communicate the Results

Finally, the researcher must communicate the results of the research through a research report, presentation, or publication. The research report should provide a detailed account of the research process, including the research question, literature review, research methodology, data analysis, findings, and conclusions. The report should also include recommendations for further research in the area.

Review and Revise

The research process is an iterative one, and it is important to review and revise the research plan and methodology as necessary. Researchers should assess the quality of their data and methods, reflect on their findings, and consider areas for improvement.

Ethical Considerations

Throughout the research process, ethical considerations must be taken into account. This includes ensuring that the research design protects the welfare of research participants, obtaining informed consent, maintaining confidentiality and privacy, and avoiding any potential harm to participants or their communities.

Dissemination and Application

The final step in the research process is to disseminate the findings and apply the research to real-world settings. Researchers can share their findings through academic publications, presentations at conferences, or media coverage. The research can be used to inform policy decisions, develop interventions, or improve practice in the relevant field.

Research Process Example

Following is a Research Process Example:

Research Question : What are the effects of a plant-based diet on athletic performance in high school athletes?

Step 1: Background Research Conduct a literature review to gain a better understanding of the existing research on the topic. Read academic articles and research studies related to plant-based diets, athletic performance, and high school athletes.

Step 2: Develop a Hypothesis Based on the literature review, develop a hypothesis that a plant-based diet positively affects athletic performance in high school athletes.

Step 3: Design the Study Design a study to test the hypothesis. Decide on the study population, sample size, and research methods. For this study, you could use a survey to collect data on dietary habits and athletic performance from a sample of high school athletes who follow a plant-based diet and a sample of high school athletes who do not follow a plant-based diet.

Step 4: Collect Data Distribute the survey to the selected sample and collect data on dietary habits and athletic performance.

Step 5: Analyze Data Use statistical analysis to compare the data from the two samples and determine if there is a significant difference in athletic performance between those who follow a plant-based diet and those who do not.

Step 6 : Interpret Results Interpret the results of the analysis in the context of the research question and hypothesis. Discuss any limitations or potential biases in the study design.

Step 7: Draw Conclusions Based on the results, draw conclusions about whether a plant-based diet has a significant effect on athletic performance in high school athletes. If the hypothesis is supported by the data, discuss potential implications and future research directions.

Step 8: Communicate Findings Communicate the findings of the study in a clear and concise manner. Use appropriate language, visuals, and formats to ensure that the findings are understood and valued.

Applications of Research Process

The research process has numerous applications across a wide range of fields and industries. Some examples of applications of the research process include:

- Scientific research: The research process is widely used in scientific research to investigate phenomena in the natural world and develop new theories or technologies. This includes fields such as biology, chemistry, physics, and environmental science.

- Social sciences : The research process is commonly used in social sciences to study human behavior, social structures, and institutions. This includes fields such as sociology, psychology, anthropology, and economics.

- Education: The research process is used in education to study learning processes, curriculum design, and teaching methodologies. This includes research on student achievement, teacher effectiveness, and educational policy.

- Healthcare: The research process is used in healthcare to investigate medical conditions, develop new treatments, and evaluate healthcare interventions. This includes fields such as medicine, nursing, and public health.

- Business and industry : The research process is used in business and industry to study consumer behavior, market trends, and develop new products or services. This includes market research, product development, and customer satisfaction research.

- Government and policy : The research process is used in government and policy to evaluate the effectiveness of policies and programs, and to inform policy decisions. This includes research on social welfare, crime prevention, and environmental policy.

Purpose of Research Process

The purpose of the research process is to systematically and scientifically investigate a problem or question in order to generate new knowledge or solve a problem. The research process enables researchers to:

- Identify gaps in existing knowledge: By conducting a thorough literature review, researchers can identify gaps in existing knowledge and develop research questions that address these gaps.

- Collect and analyze data : The research process provides a structured approach to collecting and analyzing data. Researchers can use a variety of research methods, including surveys, experiments, and interviews, to collect data that is valid and reliable.

- Test hypotheses : The research process allows researchers to test hypotheses and make evidence-based conclusions. Through the systematic analysis of data, researchers can draw conclusions about the relationships between variables and develop new theories or models.

- Solve problems: The research process can be used to solve practical problems and improve real-world outcomes. For example, researchers can develop interventions to address health or social problems, evaluate the effectiveness of policies or programs, and improve organizational processes.

- Generate new knowledge : The research process is a key way to generate new knowledge and advance understanding in a given field. By conducting rigorous and well-designed research, researchers can make significant contributions to their field and help to shape future research.

Tips for Research Process

Here are some tips for the research process:

- Start with a clear research question : A well-defined research question is the foundation of a successful research project. It should be specific, relevant, and achievable within the given time frame and resources.

- Conduct a thorough literature review: A comprehensive literature review will help you to identify gaps in existing knowledge, build on previous research, and avoid duplication. It will also provide a theoretical framework for your research.

- Choose appropriate research methods: Select research methods that are appropriate for your research question, objectives, and sample size. Ensure that your methods are valid, reliable, and ethical.

- Be organized and systematic: Keep detailed notes throughout the research process, including your research plan, methodology, data collection, and analysis. This will help you to stay organized and ensure that you don’t miss any important details.

- Analyze data rigorously: Use appropriate statistical and analytical techniques to analyze your data. Ensure that your analysis is valid, reliable, and transparent.

- I nterpret results carefully : Interpret your results in the context of your research question and objectives. Consider any limitations or potential biases in your research design, and be cautious in drawing conclusions.

- Communicate effectively: Communicate your research findings clearly and effectively to your target audience. Use appropriate language, visuals, and formats to ensure that your findings are understood and valued.

- Collaborate and seek feedback : Collaborate with other researchers, experts, or stakeholders in your field. Seek feedback on your research design, methods, and findings to ensure that they are relevant, meaningful, and impactful.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Recommendations – Examples and Writing...

Ethical Considerations – Types, Examples and...

Table of Contents – Types, Formats, Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Problem Statement – Writing Guide, Examples and...

Theoretical Framework – Types, Examples and...

Overview of the Research Process

- First Online: 01 January 2012

Cite this chapter

- Phyllis G. Supino EdD 3

6480 Accesses

2 Citations

1 Altmetric

Research is a rigorous problem-solving process whose ultimate goal is the discovery of new knowledge. Research may include the description of a new phenomenon, definition of a new relationship, development of a new model, or application of an existing principle or procedure to a new context. Research is systematic, logical, empirical, reductive, replicable and transmittable, and generalizable. Research can be classified according to a variety of dimensions: basic, applied, or translational; hypothesis generating or hypothesis testing; retrospective or prospective; longitudinal or cross-sectional; observational or experimental; and quantitative or qualitative. The ultimate success of a research project is heavily dependent on adequate planning.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Research: Meaning and Purpose

The Roadmap to Research: Fundamentals of a Multifaceted Research Process

Research Questions and Research Design

Calvert J, Martin BR (2001) Changing conceptions of basic research? Brighton, England: Background document for the Workshop on Policy Relevance and Measurement of Basic Research, Oslo, 29–30 Oct 2001. Brighton, England: SPRU.

Google Scholar

Leedy PD. Practical research. Planning and design. 6th ed. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall; 1997.

Tuckman BW. Conducting educational research. 3rd ed. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich; 1972.

Tanenbaum SJ. Knowing and acting in medical practice. The epistemological policies of outcomes research. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1994;19:27–44.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Richardson WS. We should overcome the barriers to evidence-based clinical diagnosis! J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:217–27.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

MacCorquodale K, Meehl PE. On a distinction between hypothetical constructs and intervening variables. Psych Rev. 1948;55:95–107.

Article CAS Google Scholar

The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research: The Belmont Report: Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. Washington: DHEW Publication No. (OS) 78–0012, Appendix I, DHEW Publication No. (OS) 78–0013, Appendix II, DHEW Publication (OS) 780014; 1978.

Coryn CLS. The fundamental characteristics of research. J Multidisciplinary Eval. 2006;3:124–33.

Smith NL, Brandon PR. Fundamental issues in evaluation. New York: Guilford; 2008.

Committee on Criteria for Federal Support of Research and Development, National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, Institute of Medicine, National Research Council. Allocating federal funds for science and technology. Washington, DC: The National Academies; 1995.

Busse R, Fleming I. A critical look at cardiovascular translational research. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1999;277:H1655–60.

CAS Google Scholar

Schuster DP, Powers WJ. Translational and experimental clinical research. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Williams; 2005.

Woolf SH. The meaning of translational research and why it matters. JAMA. 2008;299:211–21.

Robertson D, Williams GH. Clinical and translational science: principles of human research. London: Elsevier; 2009.

Goldblatt EM, Lee WH. From bench to bedside: the growing use of translational research in cancer medicine. Am J Transl Res. 2010;2:1–18.

PubMed Google Scholar

Milloy SJ. Science without sense: the risky business of public health research. In: Chapter 5, Mining for statistical associations. Cato Institute. 2009. http://www.junkscience.com/news/sws/sws-chapter5.html . Retrieved 29 Oct 2009.

Gawande A. The cancer-cluster myth. The New Yorker, 8 Feb 1999, p. 34–37.

Kerlinger F. [Chapter 2: problems and hypotheses]. In: Foundations of behavioral research 3rd edn. Orlando: Harcourt, Brace; 1986.

Ioannidis JP. Why most published research findings are false. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e124. Epub 2005 Aug 30.

Andersen B. Methodological errors in medical research. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1990.

DeAngelis C. An introduction to clinical research. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990.

Hennekens CH, Buring JE. Epidemiology in medicine. 1st ed. Boston: Little Brown; 1987.

Jekel JF. Epidemiology, biostatistics, and preventive medicine. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007.

Hess DR. Retrospective studies and chart reviews. Respir Care. 2004;49:1171–4.

Wissow L, Pascoe J. Types of research models and methods (chapter four). In: An introduction to clinical research. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990.

Bacchieri A, Della Cioppa G. Fundamentals of clinical research: bridging medicine, statistics and operations. Milan: Springer; 2007.

Wood MJ, Ross-Kerr JC. Basic steps in planning nursing research. From question to proposal. 6th ed. Boston: Jones and Barlett; 2005.

DeVita VT, Lawrence TS, Rosenberg SA, Weinberg RA, DePinho RA. Cancer. Principles and practice of oncology, vol. 1. Philadelphia: Wolters Klewer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of clinical research. Applications to practice. 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall Health; 2000.

Marks RG. Designing a research project. The basics of biomedical research methodology. Belmont: Lifetime Learning Publications: A division of Wadsworth; 1982.

Easterbrook PJ, Berlin JA, Gopalan R, Matthews DR. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet. 1991;337:867–72.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, 450 Clarkson Avenue, 1199, Brooklyn, NY, 11203, USA

Phyllis G. Supino EdD

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Phyllis G. Supino EdD .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

, Cardiovascular Medicine, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Clarkson Avenue, box 1199 450, Brooklyn, 11203, USA

Phyllis G. Supino

, Cardiovascualr Medicine, SUNY Downstate Medical Center, Clarkson Avenue 450, Brooklyn, 11203, USA

Jeffrey S. Borer

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2012 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

About this chapter

Supino, P.G. (2012). Overview of the Research Process. In: Supino, P., Borer, J. (eds) Principles of Research Methodology. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3360-6_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3360-6_1

Published : 18 April 2012

Publisher Name : Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-1-4614-3359-0

Online ISBN : 978-1-4614-3360-6

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Meta-Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Research Methodology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

21 Problem Solving

Miriam Bassok, Department of Psychology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Overview of the Problem-Solving Mental Process

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Rachel Goldman, PhD FTOS, is a licensed psychologist, clinical assistant professor, speaker, wellness expert specializing in eating behaviors, stress management, and health behavior change.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Rachel-Goldman-1000-a42451caacb6423abecbe6b74e628042.jpg)

- Identify the Problem

- Define the Problem

- Form a Strategy

- Organize Information

- Allocate Resources

- Monitor Progress

- Evaluate the Results

Frequently Asked Questions

Problem-solving is a mental process that involves discovering, analyzing, and solving problems. The ultimate goal of problem-solving is to overcome obstacles and find a solution that best resolves the issue.

The best strategy for solving a problem depends largely on the unique situation. In some cases, people are better off learning everything they can about the issue and then using factual knowledge to come up with a solution. In other instances, creativity and insight are the best options.

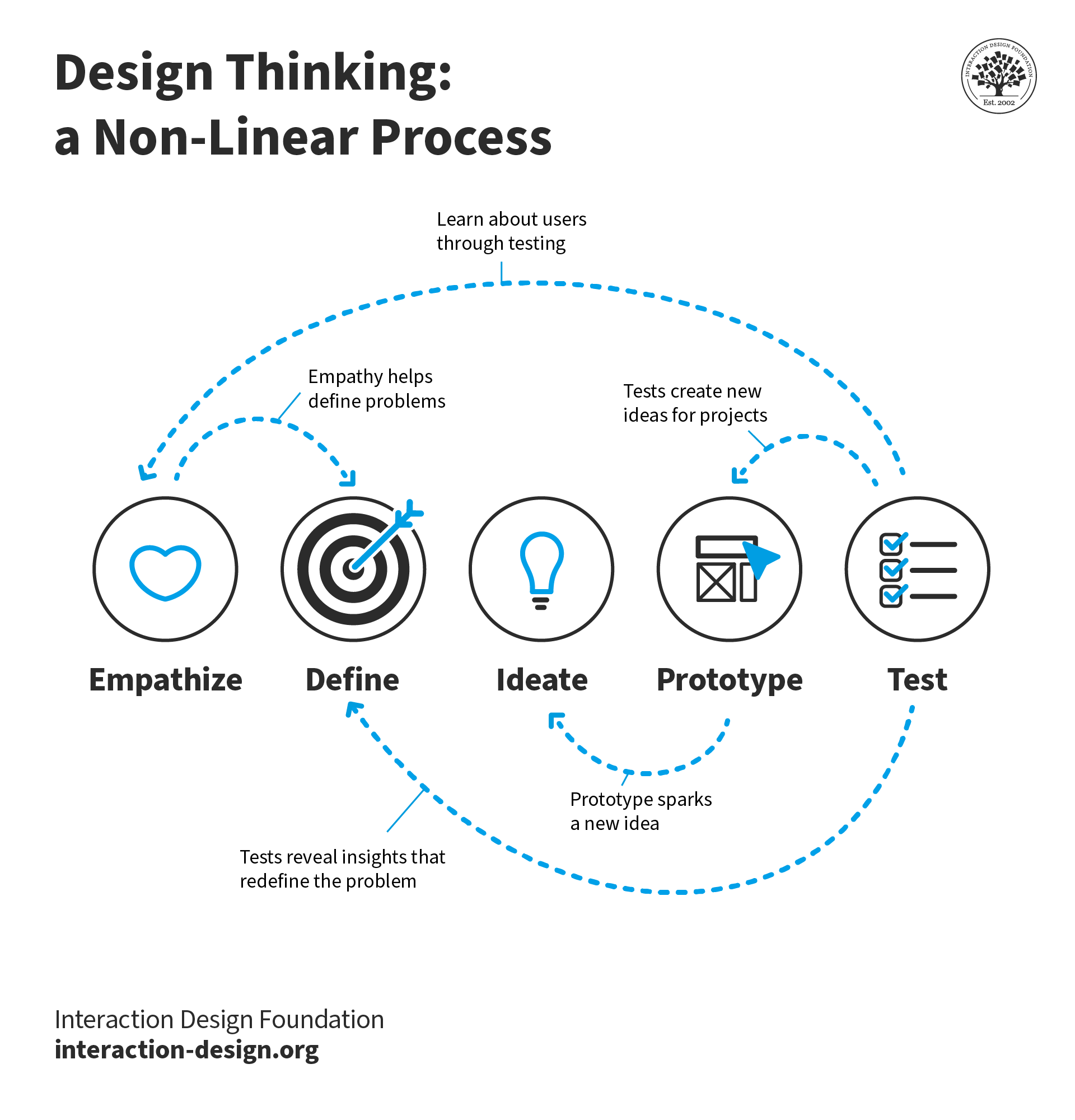

It is not necessary to follow problem-solving steps sequentially, It is common to skip steps or even go back through steps multiple times until the desired solution is reached.

In order to correctly solve a problem, it is often important to follow a series of steps. Researchers sometimes refer to this as the problem-solving cycle. While this cycle is portrayed sequentially, people rarely follow a rigid series of steps to find a solution.

The following steps include developing strategies and organizing knowledge.

1. Identifying the Problem

While it may seem like an obvious step, identifying the problem is not always as simple as it sounds. In some cases, people might mistakenly identify the wrong source of a problem, which will make attempts to solve it inefficient or even useless.

Some strategies that you might use to figure out the source of a problem include :

- Asking questions about the problem

- Breaking the problem down into smaller pieces

- Looking at the problem from different perspectives

- Conducting research to figure out what relationships exist between different variables

2. Defining the Problem

After the problem has been identified, it is important to fully define the problem so that it can be solved. You can define a problem by operationally defining each aspect of the problem and setting goals for what aspects of the problem you will address

At this point, you should focus on figuring out which aspects of the problems are facts and which are opinions. State the problem clearly and identify the scope of the solution.

3. Forming a Strategy

After the problem has been identified, it is time to start brainstorming potential solutions. This step usually involves generating as many ideas as possible without judging their quality. Once several possibilities have been generated, they can be evaluated and narrowed down.

The next step is to develop a strategy to solve the problem. The approach used will vary depending upon the situation and the individual's unique preferences. Common problem-solving strategies include heuristics and algorithms.

- Heuristics are mental shortcuts that are often based on solutions that have worked in the past. They can work well if the problem is similar to something you have encountered before and are often the best choice if you need a fast solution.

- Algorithms are step-by-step strategies that are guaranteed to produce a correct result. While this approach is great for accuracy, it can also consume time and resources.

Heuristics are often best used when time is of the essence, while algorithms are a better choice when a decision needs to be as accurate as possible.

4. Organizing Information

Before coming up with a solution, you need to first organize the available information. What do you know about the problem? What do you not know? The more information that is available the better prepared you will be to come up with an accurate solution.

When approaching a problem, it is important to make sure that you have all the data you need. Making a decision without adequate information can lead to biased or inaccurate results.

5. Allocating Resources

Of course, we don't always have unlimited money, time, and other resources to solve a problem. Before you begin to solve a problem, you need to determine how high priority it is.

If it is an important problem, it is probably worth allocating more resources to solving it. If, however, it is a fairly unimportant problem, then you do not want to spend too much of your available resources on coming up with a solution.

At this stage, it is important to consider all of the factors that might affect the problem at hand. This includes looking at the available resources, deadlines that need to be met, and any possible risks involved in each solution. After careful evaluation, a decision can be made about which solution to pursue.

6. Monitoring Progress

After selecting a problem-solving strategy, it is time to put the plan into action and see if it works. This step might involve trying out different solutions to see which one is the most effective.

It is also important to monitor the situation after implementing a solution to ensure that the problem has been solved and that no new problems have arisen as a result of the proposed solution.

Effective problem-solvers tend to monitor their progress as they work towards a solution. If they are not making good progress toward reaching their goal, they will reevaluate their approach or look for new strategies .

7. Evaluating the Results

After a solution has been reached, it is important to evaluate the results to determine if it is the best possible solution to the problem. This evaluation might be immediate, such as checking the results of a math problem to ensure the answer is correct, or it can be delayed, such as evaluating the success of a therapy program after several months of treatment.

Once a problem has been solved, it is important to take some time to reflect on the process that was used and evaluate the results. This will help you to improve your problem-solving skills and become more efficient at solving future problems.

A Word From Verywell

It is important to remember that there are many different problem-solving processes with different steps, and this is just one example. Problem-solving in real-world situations requires a great deal of resourcefulness, flexibility, resilience, and continuous interaction with the environment.

Get Advice From The Verywell Mind Podcast

Hosted by therapist Amy Morin, LCSW, this episode of The Verywell Mind Podcast shares how you can stop dwelling in a negative mindset.

Follow Now : Apple Podcasts / Spotify / Google Podcasts

You can become a better problem solving by:

- Practicing brainstorming and coming up with multiple potential solutions to problems

- Being open-minded and considering all possible options before making a decision

- Breaking down problems into smaller, more manageable pieces

- Asking for help when needed

- Researching different problem-solving techniques and trying out new ones

- Learning from mistakes and using them as opportunities to grow

It's important to communicate openly and honestly with your partner about what's going on. Try to see things from their perspective as well as your own. Work together to find a resolution that works for both of you. Be willing to compromise and accept that there may not be a perfect solution.

Take breaks if things are getting too heated, and come back to the problem when you feel calm and collected. Don't try to fix every problem on your own—consider asking a therapist or counselor for help and insight.

If you've tried everything and there doesn't seem to be a way to fix the problem, you may have to learn to accept it. This can be difficult, but try to focus on the positive aspects of your life and remember that every situation is temporary. Don't dwell on what's going wrong—instead, think about what's going right. Find support by talking to friends or family. Seek professional help if you're having trouble coping.

Davidson JE, Sternberg RJ, editors. The Psychology of Problem Solving . Cambridge University Press; 2003. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511615771

Sarathy V. Real world problem-solving . Front Hum Neurosci . 2018;12:261. Published 2018 Jun 26. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2018.00261

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Encyclopedia for Writers

Writing with ai.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - Founder, Writing Commons

Research refers to a systematic investigation carried out to discover new knowledge , test existing knowledge claims, solve practical problems , and develop new products, apps, and services. This article explores why different research communities have different ideas about what research is and how to conduct it. Learn about the different epistemological assumptions that undergird informal , qualitative , quantitative , textual , and mixed research methods .

Table of Contents

What is Research?

Research may refer to

- For most researchers, the first step in any research project involves strategic searching to learn what the current and best research, theory, and scholarship is on a topic .

- scholars create knowledge by engaging in textual research , interpretation , and hermeneutics .

- scientists create knowledge by engaging in observation and systematic experimentation.

- Ethnography

- Participant Observation

- Survey Research

- “a systematic application of knowledge toward the production of useful materials, devices, and systems or methods, including design, development, and improvement of prototypes and new processes” (NSF n.d.)

- a process, a research methodology , that follows the principles of lean design .

Key Words: Research Community ; Research Methodology ; Research Methods ; Epistemology

Why Does Research Matter?

Overall, research is essential for advancing knowledge, solving problems, informing decision-making, fostering innovation, and promoting critical thinking. It plays a crucial role in shaping the world we live in and the future we create.

- Research allows us to better understand the world around us, from the fundamental workings of the universe to the intricacies of human behavior. By conducting research, scholars can uncover new information, develop new theories and models, and identify gaps in existing knowledge that need to be filled. This knowledge can help students and teachers to better understand the world around them and develop new solutions to the problems facing society.

- Research helps us identify and solve problems. It can help us find ways to improve our health, protect the environment, reduce poverty, and develop new technologies.

- Research provides important information that can inform policy decisions, business strategies, and individual choices. By studying trends, analyzing data, and conducting experiments, researchers can help us make better-informed decisions.

- Research often leads to new technologies, products, and services. By pushing the boundaries of what is currently possible, researchers can inspire and fuel innovation.

- Research teaches us to question assumptions, evaluate evidence, and think critically. These skills are important for students to develop because they enable them to become more informed and engaged citizens, able to make more informed decisions and contribute to society in meaningful ways.

- Research experience can be an asset in many career fields, including academia, business, government, and nonprofit organizations. By conducting research as an undergraduate student, students can develop valuable skills and experience that can help them to succeed in their future careers.

Types of Research

The choice of research methods depends on the epistemological assumptions of the researchers and the practices of a particular methodological community , the research question , the type of data needed, and the resources available.

Epistemology and Research Communities

Investigators across academic disciplines — the humanities, social sciences, sciences, and the arts — share some common methods and values. For instance, in both workplace writing and academic writing , investigators are careful

- to cite sources , particularly sources that have changed the conversation on a topic

- to provide evidence for claims (as opposed to opinion or other forms of anecdotal knowledge .

Yet it is also important to note that different research communities also develop unique approaches to exploring and solving problems in their knowledge domains. Research communities develop different ways of conducting research because they face different problems and because they may have different epistemological assumptions about what knowledge is and how to measure it. For example, if a researcher believes that knowledge can only be gained through observation and empirical evidence , they may choose to use quantitative research methods such as experiments or surveys . Conversely, if a researcher believes that knowledge can also be gained through subjective experience and interpretation , they may choose to use qualitative research methods such as case study , ethnography or participant observation

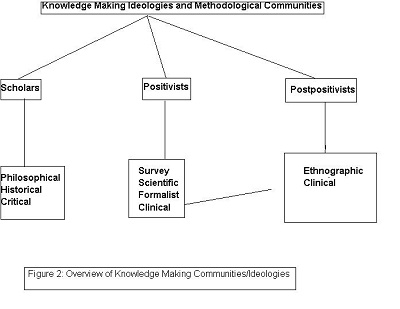

While there are many nuanced definitions of epistemology , scholars have identified three major epistemological perspectives that inform the works of three research communities

- The Scholars – aka Scholarship

- The Positivists – aka Positivism

- The Postpositivists – aka Postpositivism

Research & Mindset

Researchers are curious about the world. They embrace openness , a growth mindset , and collaboration . They undertake research projects in order to review existing knowledge and generate original knowledge claims about the topic , thesis, research question they are investigating. Research finds evidence.

Research Ethics

Researchers and consumers of research are wise to view research claims and research plans from an ethical perspective. Given human nature — such as the tendency to look for confirming evidence and ignore disconfirming evidence and to allow emotions to cloud reasoning — it’s foolhardy to disregard critical literacy practices when consuming the research of others.

Ethics are important to undergraduate students as researchers because ethics provide a framework for conducting research that is responsible, respectful, and accountable :

- Ethics ensure that participants in research are treated with respect and dignity, and that their rights and well-being are protected. As a student researcher, it is important to obtain informed consent from participants, ensure their confidentiality, and minimize any potential harm or discomfort.

- Ethics ensure that research is conducted with integrity and honesty. This means that data is collected and analyzed accurately, and that findings are reported truthfully and transparently.

- Ethics help to build trust between researchers and the public. When research is conducted ethically, participants and the wider community are more likely to trust the findings and the researchers themselves.

- Adhering to ethical standards in research can help students to develop important professional skills, such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and communication . These skills can be useful in a wide range of career fields, including academia, healthcare, and government.

- Ethical research is a professional obligation. By conducting research ethically, students are fulfilling their obligations to the wider research community.

Research as an Iterative, Recursive, Chaotic Process

Research is commonly depicted on websites and textbooks on research methods as systematic work (see, e.g., Wikipedia’s Research page).

Depicting research as systematic work is certainly valid, especially in natural and social science research. For instance, scientists in the lab working with a virus like COVID-19 or Ebola aren’t going to play around. Their professionalism and safety is tied to rigorously following research protocols.

That said, it’s an oversimplification to suggest research processes are invariably systematic. Discoveries have emerged from basic research that have been wildly popular and useful real-world applications . (See, for example, 24 Unintended Scientific Discoveries — the video below). Scientists may begin researching hypothesis A but rewrite that hypothesis multiple times until they find hypothesis Z — something that explains the data. Then they go back and repackage their investigation, following ethical standards, for a wider audience.

Ultimately, because research is such an iterative process, the thesis or hypothesis a researcher began with may not be the one the researcher ends up with. The takeaway here is that research is a learning process. Research efforts can lead to unpredictable applications and insights. Research finds evidence. Ultimately, research is about curiosity and openness. The question that initiates a research effort may morph into other questions as researchers

- dig deeper into the literature on the topic and become more conversant

- endeavor to make sense of the data/information they have gathered during the conduct of the study.

Related Concepts

Research methods.

Research results— knowledge claims -—are important. But, how researchers claim to know what they know—their research methods and research methodology —are equally important.

Information Literacy

During the early stages of a writing project, you can identify research questions worth asking by engaging in Information Literacy practices.

Using Evidence

Learn to summarize, paraphrase , and cite sources . Weave others’ ideas and words into your texts in ways that support your thesis/research question , information , rhetorical stance .

Hale, J. (2018). Understanding research methodology 5: Applied and basic research, PsychCentral . https://psychcentral.com/blog/understanding-research-methodology-5-applied-and-basic-research/

Related Articles

Applied Research, Basic Research

Epistemology - theories of knowledge.

Research Methodology

Scholarship - The Scholars - Textual Research Methods

Recommended.

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Structured Revision – How to Revise Your Work

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Authority & Credibility – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Research, Speech & Writing

Citation Guide – Learn How to Cite Sources in Academic and Professional Writing

Page Design – How to Design Messages for Maximum Impact

Suggested edits.

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Related Articles:

- Joseph M. Moxley

Understand the difference between Applied Research and Basic Research.

As an investigator be sure to protect your research subjects and follow ethical standards. As a consumer of research, be mindful of when investigators may be exaggerating results, making claims...

Not all research methods are equal or produce the same kind of knowledge. Learn about the philosophies, the epistemologies, that inform qualitative, quantitative, mixed, and textual research methods.

Understand how to identify appropriate research methods for particular methodological communities, rhetorical situations, and research questions.

Scholarship is not just about memorizing facts or regurgitating information. It’s about developing a deep understanding of a subject, making connections across disciplines, and contributing to the ongoing conversation about...

Featured Articles

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- The Research Problem/Question

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A research problem is a definite, clear expression [statement] about an area of concern, a condition to be improved upon, a difficulty to be eliminated, or a troubling question that exists in scholarly literature, in theory, or within existing practice that points to a need for meaningful understanding and deliberate investigation. A research problem does not state how to do something, offer a vague or broad proposition, or present a value question. In the social and behavioral sciences, studies are most often framed around examining a problem that needs to be understood and resolved in order to improve society and the human condition.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Guba, Egon G., and Yvonna S. Lincoln. “Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research . Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, editors. (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1994), pp. 105-117; Pardede, Parlindungan. “Identifying and Formulating the Research Problem." Research in ELT: Module 4 (October 2018): 1-13; Li, Yanmei, and Sumei Zhang. "Identifying the Research Problem." In Applied Research Methods in Urban and Regional Planning . (Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2022), pp. 13-21.

Importance of...

The purpose of a problem statement is to:

- Introduces the reader to the importance of the topic being studied . The reader is oriented to the significance of the study.

- Anchors the research questions, hypotheses, or assumptions to follow . It offers a concise statement about the purpose of your paper.

- Places the topic into a particular context . It defines the parameters of what is to be investigated.

- Provides the framework for reporting the results. It indicates what is probably necessary to conduct the study and explain how the findings will present this information.

In the social and behavioral sciences, the research problem establishes the means by which you must answer the "So What?" question. This declarative question refers to a research problem surviving the relevancy test [the quality of a measurement procedure that provides repeatability and accuracy]. Note that answering the "So What?" question requires a commitment on your part to not only show that you have reviewed the literature, but that you have thoroughly considered the significance of the research problem and its implications applied to creating new knowledge and understanding or informing practice in a meaningful way.

To survive the "So What" question, problem statements should possess the following attributes:

- Clarity and precision [a well-written statement does not make sweeping generalizations and irresponsible pronouncements; it also does include unspecific determinates like "very" or "giant"],

- Demonstrate a researchable topic or issue [i.e., feasibility of conducting the study is based upon access to information that can be effectively acquired, gathered, interpreted, synthesized, understood, and accurately reported],

- Identification of what would be studied, while avoiding the use of value-laden words and terms,

- Identification of an overarching question or small set of questions accompanied by key factors or variables,

- Identification of key concepts and terms,

- Articulation of the study's conceptual boundaries or parameters or limitations,

- Some generalizability in regards to applicability and bringing results into general use,

- Conveyance of the study's importance, benefits, and justification [i.e., regardless of the type of research, it is important to demonstrate that the research is not trivial],

- Does not have unnecessary jargon or overly complex sentence constructions; and,

- Conveyance of more than the mere gathering of descriptive data providing only a snapshot of the issue or phenomenon under investigation.

Bryman, Alan. “The Research Question in Social Research: What is its Role?” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 10 (2007): 5-20; Brown, Perry J., Allen Dyer, and Ross S. Whaley. "Recreation Research—So What?" Journal of Leisure Research 5 (1973): 16-24; Castellanos, Susie. Critical Writing and Thinking. The Writing Center. Dean of the College. Brown University; Ellis, Timothy J. and Yair Levy Nova. "Framework of Problem-Based Research: A Guide for Novice Researchers on the Development of a Research-Worthy Problem." Informing Science: the International Journal of an Emerging Transdiscipline 11 (2008); Thesis and Purpose Statements. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Thesis Statements. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Selwyn, Neil. "‘So What?’…A Question that Every Journal Article Needs to Answer." Learning, Media, and Technology 39 (2014): 1-5; Shoket, Mohd. "Research Problem: Identification and Formulation." International Journal of Research 1 (May 2014): 512-518.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Types and Content

There are four general conceptualizations of a research problem in the social and behavioral sciences:

- Casuist Research Problem -- this type of problem relates to the determination of right and wrong in questions of conduct or conscience by analyzing moral dilemmas through the application of general rules and the careful distinction of special cases.

- Difference Research Problem -- typically asks the question, “Is there a difference between two or more groups or treatments?” This type of problem statement is used when the researcher compares or contrasts two or more phenomena. This a common approach to defining a problem in the clinical social sciences or behavioral sciences.

- Descriptive Research Problem -- typically asks the question, "what is...?" with the underlying purpose to describe the significance of a situation, state, or existence of a specific phenomenon. This problem is often associated with revealing hidden or understudied issues.

- Relational Research Problem -- suggests a relationship of some sort between two or more variables to be investigated. The underlying purpose is to investigate specific qualities or characteristics that may be connected in some way.

A problem statement in the social sciences should contain :

- A lead-in that helps ensure the reader will maintain interest over the study,

- A declaration of originality [e.g., mentioning a knowledge void or a lack of clarity about a topic that will be revealed in the literature review of prior research],

- An indication of the central focus of the study [establishing the boundaries of analysis], and

- An explanation of the study's significance or the benefits to be derived from investigating the research problem.

NOTE: A statement describing the research problem of your paper should not be viewed as a thesis statement that you may be familiar with from high school. Given the content listed above, a description of the research problem is usually a short paragraph in length.

II. Sources of Problems for Investigation

The identification of a problem to study can be challenging, not because there's a lack of issues that could be investigated, but due to the challenge of formulating an academically relevant and researchable problem which is unique and does not simply duplicate the work of others. To facilitate how you might select a problem from which to build a research study, consider these sources of inspiration:

Deductions from Theory This relates to deductions made from social philosophy or generalizations embodied in life and in society that the researcher is familiar with. These deductions from human behavior are then be placed within an empirical frame of reference through research. From a theory, the researcher can formulate a research problem or hypothesis stating the expected findings in certain empirical situations. The research asks the question: “What relationship between variables will be observed if theory aptly summarizes the state of affairs?” One can then design and carry out a systematic investigation to assess whether empirical data confirm or reject the hypothesis, and hence, the theory.

Interdisciplinary Perspectives Identifying a problem that forms the basis for a research study can come from academic movements and scholarship originating in disciplines outside of your primary area of study. This can be an intellectually stimulating exercise. A review of pertinent literature should include examining research from related disciplines that can reveal new avenues of exploration and analysis. An interdisciplinary approach to selecting a research problem offers an opportunity to construct a more comprehensive understanding of a very complex issue that any single discipline may be able to provide.

Interviewing Practitioners The identification of research problems about particular topics can arise from formal interviews or informal discussions with practitioners who provide insight into new directions for future research and how to make research findings more relevant to practice. Discussions with experts in the field, such as, teachers, social workers, health care providers, lawyers, business leaders, etc., offers the chance to identify practical, “real world” problems that may be understudied or ignored within academic circles. This approach also provides some practical knowledge which may help in the process of designing and conducting your study.

Personal Experience Don't undervalue your everyday experiences or encounters as worthwhile problems for investigation. Think critically about your own experiences and/or frustrations with an issue facing society or related to your community, your neighborhood, your family, or your personal life. This can be derived, for example, from deliberate observations of certain relationships for which there is no clear explanation or witnessing an event that appears harmful to a person or group or that is out of the ordinary. From this, assume the position of a researcher to explore how a personal experience could be examined as a topic of investigation with outcomes [findings] applicable to others.

Relevant Literature The selection of a research problem can be derived from a thorough review of pertinent research associated with your overall area of interest. This may reveal where a lack of evidence exists in understanding a topic or where an issue has been understudied. Research may be conducted to: 1) fill such gaps in knowledge; 2) evaluate if the methodologies employed in prior studies can be adapted to solve other problems; or, 3) determine if a similar study could be conducted in a different subject area or applied in a different context or to different study sample [i.e., different setting or different group of people].

NOTE: Authors frequently conclude their studies by noting implications for further research; read the conclusion of pertinent studies because statements about further research can be a valuable source for identifying new problems to investigate. The fact that a researcher has identified a topic worthy of further exploration validates the fact it is worth pursuing.

III. What Makes a Good Research Statement?

A good problem statement begins by introducing the broad area in which your research is centered, gradually leading the reader to the more specific issues you are investigating. The statement need not be lengthy, but a good research problem should incorporate the following features: