- Thesis Statement Generator

- Online Summarizer

- Rewording Tool

- Topic Generator

- Essay Title Page Maker

- Conclusion Writer

- Academic Paraphraser

- Essay Writing Help

- Topic Ideas

- Writing Guides

- Useful Information

How to Write a Reaction Paper: Format, Template, & Reaction Paper Examples

A reaction paper is one of the assignments you can get in college. It may seem easy at first glance, similar to a diary entry requiring your reaction to an article, a literature piece, or a movie. However, writing a high-quality paper often turns into a challenge. Here is a handy guide on how to write a reaction paper, with examples and topic suggestions.

- ❓ What Is a Reaction Paper?

✍️ Reaction Paper Format

- 🤔 How to Write a Reaction Paper

💭 Reaction Paper Questions

- 📋 Transitional Words

🔍 Reaction Paper Examples

- ⁉️ Questions and Answers

🔗 References

❓ what is a reaction paper assignment.

A reaction paper (or response paper) is an academic assignment urging students to explain what they feel about something . When crafting a good reaction piece, the student should aim to clarify what they think, agree or disagree with, and how they would identify with the object regarding their life experiences. The object of your response may be a painting, a book, an academic publication, or a documentary.

This task is not a simple summary of the text or film you’re assigned to. Neither is it a research paper; you don’t need to use external sources in a reaction paper. Thus, the writing process may seem confusing to newbies. Let’s clarify its main elements and features to help you out.

Every academic assignment has a specific structure and requirements to follow. Here we discuss the major elements of the response paper format to guide you through its components and the composition algorithm. As soon as you capture the structure, you can write stellar texts without a problem.

Reaction Paper Template

Every critical reaction paper follows the standard essay outline, with the introduction, the main body, and the conclusion as to its main parts. Here is a more detailed breakdown of each component:

- Introduction . You present the subject and set the context for the readers.

- Body . This part is a detailed analysis of your response to the subject. You should list the main points and analyze them, relating to your feelings and experiences.

- Wrap-up . Here you recap all major points and restate your opinion about the subject, giving it a conclusive evaluation.

Reaction Paper: APA Format

Depending on your teacher’s preferences and the academic subject, you may be given a reaction paper assignment in various referencing styles. The APA format is one of the possible variants. So, please don’t get confused about the writing approach; it only means that you should format your reaction paper according to APA conventions . These are:

- A standard APA title page

- One-inch margins on all sides

- Double spacing between the lines

- An author-date format of referencing external sources (if you use any supporting evidence)

The rest of the requirements are identical for reaction papers in all referencing formats, allowing you to choose.

🤔 How to Write a Good Reaction Paper Step-by-Step

Now, it’s time to clarify how to begin a reaction paper, what steps to take before writing, and how you will compose the entire assignment. Use our universal step-by-step guide fitting any reaction paper topic.

- Study the prompt inside out . You should understand the prompt to craft a relevant paper that your professor will grade highly.

- Clarify all instructions . A grave mistake that students often make is assuming they have understood everything in one go. Still, asking questions never killed anybody. So, we recommend inquiring your tutor about everything to be 100% sure you’re on the right path.

- Study the subject of your paper . Watch a movie, look at the painting, or read the text – do everything you can to get to the depths of the author’s message and intention.

- Make notes . Your reactions matter, as they will become the main content of your written text. So, annotate all feelings and ideas you have when studying the subject. You’ll be able to use them as writing prompts later.

- Make a reaction essay outline . The outline is the backbone of your content, which will serve as your compass during the actual writing process.

- Compose the draft . Use the outline as a structure and add details, evidence, and facts to support your claims. Then add an introduction and a conclusion to the final draft.

- Edit and revise . To err is human; to edit is divine. Follow this golden rule to submit a polished, revised paper without errors and typos.

How to Write a Reaction Paper About a Movie?

When the subject of your reaction paper assignment is a movie, you should consider the context in which it was given. It’s probably a supporting material for your study course dedicated to a specific learning concept or theory. Thus, it would be best to look for those links when watching the assigned movie – “ Women’s Rights and Changes over the 20 th Century ” is an excellent example of this technique. It will help you draw the connections in your reaction paper, showing your professor that you understand the material and can relate theory and practice.

The steps you need to take are as follows:

- Watch the film . It’s better to do it 2-3 times to capture all the tiny details.

- Take notes . Record the film’s central themes, messages, character traits, and relationships.

- Focus on a relevant element of the film in your response . If it’s a Film Studies class, you may write about the stylistic means and shooting techniques that the director used. If it’s a psychology class, you may write about characters and their relationships. If you need to compose a Sociology or Politics reaction paper, you may focus on the context of the film’s events.

- Revise the draft . Careful editing can save your grade, helping you locate minor errors, typos, and inconsistencies. Always reserve some time for a final look at your text.

How to Write a Reaction Paper to a Documentary?

Documentaries are also frequently chosen as subjects for reaction papers. They present valid, objective data about a specific event, person, or phenomenon and serve as informative, educational material for students. Here’s what you need to do if you get such a task:

- Watch the documentary several times . Watch it several times to understand everything nicely. It’s usually a much more data-rich video piece than a fiction film is, so you’ll need to take many notes.

- Present your documentary in the background of your reaction paper . Set the context for further discussion by naming the author, explaining its topic and content, and presenting its central claim.

- Talk about the documentary’s purpose at length . Please focus on the details and major claims made by the director; present relevant facts you’ve learned from it.

- React to the documentary’s content and explain how you felt about it . State what points you agree with and what ideas seem controversial; explain why you agree or disagree with the director’s position.

A vital aspect of a response to a documentary is comparing what you knew and thought about the subject before and after watching it. It’s a significant learning experience you should share, showing whether you have managed to progress through the studies and acquire new information. Look through the “ Alive Inside: A Story of Music and Memory ” reaction paper to get a clear idea of how it works.

How to Write a Reaction Paper to an Article?

Once you get a home task to write a reaction paper to an article, you should follow this algorithm:

- Read the article several times to understand it well . Make notes every time you read; new shades of meaning and details will emerge.

- Explain the key claims and terms of the article in your own words, as simply as possible . Then respond to them by evaluating the strength of those claims and their relevance.

- Assess the author’s stand and state whether you agree with it . Always give details about why you do or don’t support the author’s position.

- Question the evidence provided by the author and analyze it with additional sources, if necessary.

Please don’t forget about the following writing conventions:

An excellent example of a response paper to an article is “ Gay Marriage: Disputes and the Ethical Dilemma .”

Tips for Writing a Psychology Reaction Paper

If you were tasked with writing a reaction paper for a Psychology class, use the following tips to excel in this assignment.

- Identify the subject you need to react to . It may be a psychological theory, a book or article on psychology, or a video of a psychologist’s performance.

- Study the subject in detail . You need to understand it to form specific reactions, give informed commentary, and evaluate the presented claims effectively.

- Think about the topic’s relevance to modern times . Is the theory/book/article consistent with the ideas people hold today? Has there been any criticism of these ideas published recently? Did later research overturn the theory?

- Form a subjective response to the assigned subject . Do you agree with that position? Do you consider it relevant to your life experience? What feelings does it arouse in you?

By approaching a psychology piece with all these questions, you can create a high-quality response based on valid data, reflecting your reactions and opinions. Look through “ Peer Interaction in Mergers: Evidence of Collective Rumination ” to see how it can be done.

Reaction essay writing is a process that you can start only after answering essential questions about the content and your feelings. Here are some examples to ask yourself when preparing for the writing stage.

- What is the author’s key message or problem addressed in the piece?

- What purpose did the author pursue when creating this text/movie/sculpture/painting? Did the author fulfill it successfully?

- What point does the author intend to make with their work of art/literature?

- What assumptions can I trace throughout the subject, and how do they shape its content/look?

- What supporting facts, arguments, and opinion does the author use to substantiate their claims? Are they of high quality? What is their persuasive power?

- What counterarguments can I formulate to the claims made by the author?

- Is the raised issue relevant/interesting/significant?

- What are the author’s primary symbols or figurative means to pass their message across?

- Do I like or dislike the piece overall? What elements contribute to a positive/negative impression?

- How does this piece/subject correlate with my life experience and context?

- How can the reflections derived from this subject inform my life and studies?

- What lesson can I learn from this subject?

📋 Transitional Words for Reaction Paper

When you write a reaction paper, you express a personal opinion about a subject you have studied (a visual artwork or a text). However, the subjective nature of this assignment doesn’t mean that you should speak blatantly without caring about other people’s emotions and reactions. It’s critical to sound polite and use inclusive language.

Besides, you need to substantiate your points instead of simply stating that something is good or bad. Here are some linguistic means to help you develop a coherent reaction text:

- I think/feel/believe that

- It seems that

- In my opinion

- For example / as an illustration / as a case in point

- In contrast

- I think / I strongly believe / from my point of view

- I am confident that

- For all these reasons

- Finally / in conclusion

It’s not mandatory to squeeze all these phrases into your text. Choose some of them sparingly depending on the context; they will make your essay flow better.

Here is a short reaction paper example you can use as practical guidance. It is dedicated to the famous movie “Memento” by Christopher Nolan.

Memento is a movie about a man with a rare neurological condition – anterograde amnesia – seeking revenge for the rape and murder of his wife. He struggles to remember the recent events and creates various hints in notes and tattoos to keep the focus on his mission. Throughout the film, he meets different people who play weird roles in his life, contributing to the puzzle set by the director in the reverse scene presentation.

My first impression of the movie was confusing, as it took me half of the film to realize that the scenes were organized in the reverse order. Once the plot structure became more apparent, I opened many themes in the movie and enjoyed it until the end. Because of the severe brain damage, Leonard could not determine whether the story of his wife’s rape and murder was real, whether he had already been revenged for her death, and whether he was a hero or a villain. Thus, for me, the film was about a painful effort to restore one’s identity and seek life meaning amid the ruining memory and lost self.

The overall approach of Christopher Nolan deserves a separate mention. A unique design of shots’ sequence and the mix of chronological black-and-white and reverse chronological colored scenes is a puzzle that a viewer needs to solve. Thus, it becomes a separate thrilling adventure from the film’s storyline. My overall impression was positive, as I love Christopher Nolan’s auteur approach to filmmaking and the unique set of themes and characters he chooses for artistic portrayal.

Another example of a reaction paper we’ve prepared for you presents a reaction to “Night” by Elie Wiesel.

The horrors of World War II and concentration camps arranged by Nazis come to life when one reads Elie Wiesel’s Night. It is a literary piece composed by a person who lived in a concentration camp and went through the inhumane struggles and tortures of the Nazi regime . Though Wiesel survived, he portrayed that life-changing experience in much detail, reflecting upon the changes the threat of death makes to people’s character, relationships, and morality.

One of the passages that stroke me most was people’s cruelty toward their dearest relatives in the face of death. The son of Rabbi Eliahou decided to abandon his father because of his age and weakness, considering him a burden. This episode showed that some people adopt animal-like behavior to save their lives, forgetting about the cherished bonds with their parents. Such changes could not help but leave a scar on Elie’s soul, contributing to his loss of faith because of the cruelty around him.

However, amid the horror and cruelty that Elie Wiesel depicted in his book, the central message for me was the strength of the human spirit and the ability to withstand the darkness of evil. Wiesel was a living witness to human resilience. He witnessed numerous deaths and lost faith in God, but his survival symbolizes hope for a positive resolution of the darkest, unfairest times. Though reading “Night” left me with a heavy, pessimistic impression, I still believe that only such works can teach people peace and friendship, hoping that night will never come again.

The third sample reaction paper prepared by our pros deals with the article of David Dobbs titled “The Science of Success.”

The article “ The Science of Success ,” written by David Dobbs in 2009, presents an innovative theory of behavioral genetics. The author lays out the findings of a longitudinal study held by Marian Bakermans-Kranenbug and her team related to the evolution of children with externalizing behaviors. Their study presents a new perspective on the unique combination of genetics, environment, parenting approaches, and its impact on children’s mental health in adulthood.

The claim of Dobbs I found extremely convincing was the impact of mothers’ constructive parenting techniques on the intensity of externalizing behaviors. Though most children learn self-control with age and become calmer and more cooperative as they grow up, waiting for that moment is unhealthy for the child’s psyche. I agree that parents can help their children overcome externalizing behaviors with calm activities they all enjoy, such as reading books. Thus, the reading intervention can make a difference in children’s psychological health, teaching them self-control and giving their parents a break.

However, the second part of the article about “dandelion” and “orchid” children and their vulnerability caused more questions in me. I did not find the evidence convincing, as the claims about behavioral genetics seemed generic and self-obvious. Children raised in high-risk environments often develop depression, substance abuse, and proneness to criminality. However, Dobbs presented that trend as a groundbreaking discovery, which is debatable. Thus, I found this piece of evidence not convincing.

As you can see, reaction paper writing is an art in itself. You can compose such assignments better by mastering the techniques and valuable phrases we’ve discussed. Still, even if you lack time or motivation for independent writing, our team is on standby 24/7. Turn to us for help, and you’ll get a stellar reaction paper in no time.

⁉️ Reaction Paper Questions and Answers

What words do you use to start a reaction paper.

First, you need to introduce the subject of your paper. Name the author and the type of work you’re responding to; clarify whether it’s a film, a text, or a work of art. Next, you need to voice your opinion and evaluate the assigned subject. You can use phrases like, “I think… In my opinion… My first reaction was… I was touched by…”.

What Is the Difference Between Reflection and Reaction Paper?

The main distinction between reflection and reaction essays is their focus on the subject. A reaction paper approaches it from the viewpoint of your evaluation of the content and message of the assigned topic. It deals with how you felt about it, whether you liked it, and what thoughts it evoked in you. A reflection, in its turn, deals with your perceptions and beliefs. It focuses on the transformational experiences of either changing or reinforcing one’s views upon seeing or reading something.

What Is the Purpose of Reaction Paper?

The primary purpose of writing a reaction paper is to communicate your experience of reading, watching, or to see a subject (e.g., a movie, a book, or a sculpture). You should explain how you captured the author’s message, what you felt when exposed to that subject, and what message you derived. You can cite details and discuss your reactions to them before forming the general evaluation.

Can You Use “I” in a Reaction Paper?

Students can use the first-person “I” when writing reaction pieces. The use of the first person is generally banned in academic research and writing, but reflections and response papers are exceptions to this rule. It’s hard to compose a personal, subjective evaluation of an assigned subject without referring to your thoughts, ideas, and opinions. In this academic assignment, you can use phrases like “I believe… I think… I feel…”.

- Reaction vs. Reflection Paper: What’s the Difference? Indeed Editorial Team .

- Response Paper, Thompson Writing Program, Duke University . Guidelines for Reaction Papers, ETH Zürich .

- Film Reaction Papers, Laulima .

- How to Make a Reaction Paper Paragraph, Classroom, Nadine Smith .

- How to Write a Response Paper, ThoughtCo, Grace Fleming .

- Reviews and Reaction papers, UMGC .

- Reaction Paper, University of Arkansas .

- How to Write a Reaction Paper, WikiHow, Rachel Scoggins .

- How to Write a Reaction (Steps Plus Helpful Tips), Indeed Editorial Team .

- Response Paper, Lund University .

- How to Write a Reaction Paper in 4 Easy Steps, Cornell CS .

- Response Papers, Fred Meijer Center for Writing & Michigan Authors, Grand Valley State University .

How to Write a Reaction Paper: Guide Full of Tips

Imagine being a writer or an artist and receiving feedback on your work. What words would you cherish most? 'Amazing'? 'Wonderful'? Or perhaps 'Captivating'? While these compliments are nice, they tend to blend into the background noise of everyday praise.

But there's one accolade that truly stands out: 'Thought-provoking.' It's the kind of response every creator dreams of evoking. Thought-provoking pieces don't just passively entertain; they stir something inside us, lingering in our minds long after we've encountered them. In academic circles, a work isn't truly impactful unless it prompts a reaction.

In this article, our research paper writing services will delve into the concept of reaction papers: what they are, how to craft a stellar one, and everything in between. So, let's explore the art of provoking thought together.

What is Reaction Paper

Ever found yourself deeply engrossed in a book, movie, or perhaps an article, only to emerge with a flurry of thoughts and emotions swirling within? That's where a reaction paper comes into play. It helps you articulate those musings to dissect the themes, characters, and nuances of the work that stirred something within you.

A reaction paper is a written response to a book, article, movie, or other media form. It give you an opportunity to critically evaluate what you've experienced and to share your insights with others. Whether you're captivated by a novel's narrative, moved by a film's message, or intrigued by an academic article's argument, it allows you to explore the depths of your reaction.

Don't Enjoy Writing College Essays?

Don't break a sweat. Let our expert writers do the heavy lifting.

How to Write a Reaction Paper with 8 Easy Tips

When learning how to write a reaction paper, it's important to keep an open mind. That means being willing to consider different ideas and perspectives. It's also a good idea to really get into whatever you're reacting to—take notes, highlight important parts, and think about how it makes you feel.

Unlike some other school assignments, like essays or reports, a reaction paper is all about what you think and feel. So, it's kind of easy in that way! You just have to really understand what it's about and how to put it together.

Now, we're going to share some tips to help you write a great paper. And if you're running out of time, don't worry! You can always get some extra help from our essay writing service online .

.webp)

Understand the Point

When you're sharing your thoughts, whether in school or outside of it, it's important to have a good grasp of what you're talking about. So, before you start writing your paper, make sure you understand its goals and purpose. This way, you can give readers what they're looking for—a thoughtful, balanced analysis.

Knowing the purpose of your paper helps you stay on track. It keeps you from wandering off into unrelated subjects and lets you focus on the most important parts of the text. So, when you share your thoughts, they come across as clear and logical.

Read the Text Right After It Has Been Assigned

When you're asked to write a reaction paper, remember that your first reaction might not be your final one. Our initial thoughts can be a bit all over the place—biased, maybe even wrong! So, give yourself some time to really think things through.

Start diving into the material as soon as you get the assignment. Take your time to understand it inside and out. Read it over and over, and do some research if you need to until you've got a handle on everything—from what the author was trying to do to how they did it. Take notes along the way and try to see things from different angles.

When it comes to writing your paper, aim for a thoughtful response, not just a knee-jerk reaction. Back up your points with solid evidence and organize them well. Think of it more like writing a review than leaving a quick comment on a movie website.

Speaking of movies, we've got an example of a movie reaction paper below. Plus, if you're interested, we've got an article on discursive essay format you might find helpful.

Make a Note of Your Early Reactions

When you're diving into a topic, jotting down your initial thoughts is key. These first reactions are like capturing lightning in a bottle—they're raw, honest, and give you a real glimpse into how you're feeling.

Your paper should be like a mirror, reflecting your own experiences and insights. Your instructor wants to see the real you on the page.

Understanding why something makes you feel a certain way is crucial. By keeping track of your reactions, you can spot any biases or assumptions you might have. It's like shining a light in a dark room—you can see things more clearly. And by acknowledging these biases, you can write a paper that's fair and balanced. Plus, it can point you in the direction of further research, like following breadcrumbs through the forest.

Select a Perspective

Your perspective shapes how you see things, and it's like a roadmap for your reaction paper. It keeps you focused and organized and helps you share thoughtful insights.

Before you start writing, think about different angles to approach the topic. Figure out which perspective resonates with you the most. Consider what it does well and where it might fall short.

Putting yourself in the author's shoes can be really helpful. Try to understand why they wrote what they did and how they put it all together. It's like stepping into their world and seeing things from their point of view. This helps you analyze things more clearly and craft a solid paper.

Before we jump into the nitty-gritty of reaction paper templates, there are a few more tips to share. So, keep reading. Or if you're feeling overwhelmed, you can always ask our professional writers - ' do my homework for me ' - to lend a hand with your coursework.

Define Your Thesis

Defining your thesis might feel like trying to untangle a knot at first. Start by gathering all your ideas and main points. Think about which one resonates with you the most. Consider its strengths and weaknesses—does it really capture the essence of what you want to say?

Then, try to distill all those thoughts into a single sentence. It's like taking a handful of puzzle pieces and fitting them together to reveal the big picture. This sentence becomes the heart of your response essay, guiding your reader along with your analysis.

Organize Your Sections

When you're writing a response paper, it's important to organize your thoughts neatly. Papers that are all over the place can confuse readers and make them lose interest.

To avoid this, make sure you plan out your paper first. Create an outline with all the main sections and sub-sections you want to cover. Arrange them in a logical order that makes sense. Then, for each section, start with a clear topic sentence. Back it up with evidence like quotes or examples. After that, share your own opinion and analyze it thoroughly. Keep doing this for each section until your paper is complete. This way, your readers will be able to follow along easily and understand your argument better.

Write the Final Version

Writing a reaction paper isn't a one-shot deal. It takes several tries to get it just right. Your final version should be polished, with a strong thesis and a well-structured layout.

Before calling it done, give your paper a thorough once-over. Make sure it ticks all the boxes for your assignment and meets your readers' expectations. Check that your perspective is crystal clear, your arguments make sense and are backed up with evidence, and your paper flows smoothly from start to finish.

Keep an eye out for any slip-ups. If you catch yourself just summarizing the text instead of offering your own take, go back and rework that section. Your essay should be original but also fair and balanced. So, give it that final polish until it shines.

Check Your Paper for Spelling and Grammar

No matter what type of essay you're writing—whether it's argumentative or a reaction piece—grammar matters. Even if you've got a strong reaction statement and unique opinions, they won't shine if your sentences are hard to read.

Before you hit that submit button, take a moment to check for grammar and spelling mistakes. These little errors might seem minor, but they can really drag down the quality of your work. Plus, they signal a lack of attention to detail, which could hurt how seriously your paper is taken.

Remember, good grammar isn't just about following rules—it's about clarity. If your paper is riddled with mistakes, it'll be harder for readers to grasp your ideas. On the flip side, clean, error-free writing boosts your credibility and ensures that your thoughts come across loud and clear. So, give your paper that final polish—it's worth it.

Reaction Paper Reaction Paper Outline

Now that you've got all those handy tips and tricks under your belt let's talk about the big picture: the outline. It typically consists of three main parts: the introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion. Each section has its own job to do and is equally crucial to the overall piece. Each part needs to meet the basic requirements of a written assignment, make clear points, and properly credit any direct quotes using the appropriate citation style, like APA format.

.webp)

Introduction

Getting started with writing can feel like trying to climb a mountain. But fear not! It doesn't have to be daunting if you know how to start a reaction paper.

The introduction is your chance to make a strong first impression. It sets the stage for what's to come and gives readers a glimpse of what they can expect. But keep it snappy—nobody likes a long-winded intro!

To craft an effective introduction:

- Provide some context to get readers up to speed.

- Give a brief summary of relevant background information.

- Clearly state the purpose of your paper.

- Explain what you're hoping to achieve and why it matters.

- Wrap it up with a thesis statement that sums up your personal take and outlines the main points you'll be covering.

After your attention-grabbing introduction, it's time to keep the momentum going in the body paragraphs. This is where you really dive into your thoughts and opinions on the key points of the text.

Remember our top tip: divide your ideas into different sections. Each paragraph should kick off with a topic sentence that sums up the main idea you're tackling. Then, give a quick rundown of the specific aspect of the book or article you're discussing. After that, it's your turn to share your honest feelings about it and explain why you feel that way. Back up your ideas with quotes from trustworthy sources, and make sure to cite them correctly. And don't forget to tie your reactions back to the bigger picture.

Wrap up each paragraph by summarizing your thoughts and feelings and linking them back to the main theme of your paper. With this approach, your body paragraphs will flow smoothly and keep your readers engaged every step of the way.

As you wrap up your reaction paper format, don't overlook the importance of a strong conclusion. This is your chance to bring all your thoughts and feelings together in a neat package and leave a lasting impression on your reader.

Kick things off by revisiting your reaction statement. Remind your reader of the main points you've covered in the body paragraphs, and share any fresh insights you've gained along the way. Just remember—keep it focused on what you've already discussed. Your conclusion shouldn't introduce any new information.

Finish off your paper with a memorable closing statement that ties everything together. This is your chance to leave your reader with a final thought that resonates long after they've finished reading. With a well-crafted conclusion, you'll send your paper off on a high note and leave your reader feeling satisfied.

Reaction Paper Example

Sometimes, seeing is believing. That's why we've prepared a reaction paper example to show you exactly what a stellar paper looks like and how paying attention to small details can elevate your essay. While you're at it, you can also check out our pestle analysis example .

Final Words

Our tips and tricks on how to write a compelling reaction paper will get you an A+. Reflect on your thoughts and feelings, be clear, support your ideas with evidence, and remain objective. Review our reaction paper sample and learn how to write a high-quality academic paper.

Get professional research paper writing services from our experienced writers to ensure high grades. We offer a wide range of aid, including nursing essay writing services . Contact us today for reliable and high-quality essay writing services.

Do You Find Writing College Essays Difficult?

Join the ranks of A+ students with our essay writing services!

What Is a Reaction Paper?

How to make an outline for a reaction paper, how do you write a reaction paper, related articles.

.webp)

Skip to content. | Skip to navigation

Masterlinks

- About Hunter

- One Stop for Students

- Make a Gift

- Access the Student Guide

- Apply to Become a Peer Tutor

- Access the Faculty Guide

- Request a Classroom Visit

- Refer a Student to the Center

- Request a Classroom Workshop

- The Writing Process

- The Documented Essay/Research Paper

- Writing for English Courses

- Writing Across the Curriculum

- Grammar and Mechanics

- Business and Professional Writing

- CUNY TESTING

- | Workshops

- Research Information and Resources

- Evaluating Information Sources

- Writing Tools and References

- Reading Room

- Literary Resources

- ESL Resources for Students

- ESL Resources for Faculty

- Teaching and Learning

- | Contact Us

Each semester, you will probably be asked by at least one instructor to read a book or an article (or watch a TV show or a film) and to write a paper recording your response or reaction to the material. In these reports—often referred to as response or reaction papers—your instructor will most likely expect you to do two things: summarize the material and detail your reaction to it. The following pages explain both parts of a report.

PART 1: A SUMMARY OF THE WORK

To develop the first part of a report, do the following:

- Identify the author and title of the work and include in parentheses the publisher and publication date. For magazines, give the date of publication.

- Write an informative summary of the material.

- Condense the content of the work by highlighting its main points and key supporting points.

- Use direct quotations from the work to illustrate important ideas.

- Summarize the material so that the reader gets a general sense of all key aspects of the original work.

- Do not discuss in great detail any single aspect of the work, and do not neglect to mention other equally important points.

- Also, keep the summary objective and factual. Do not include in the first part of the paper your personal reaction to the work; your subjective impression will form the basis of the second part of your paper.

PART 2: YOUR REACTION TO THE WORK

To develop the second part of a report, do the following:

- Focus on any or all of the following questions. Check with your instructor to see if s/he wants you to emphasize specific points.

- How is the assigned work related to ideas and concerns discussed in the course for which you are preparing the paper? For example, what points made in the course textbook, class discussions, or lectures are treated more fully in the work?

- How is the work related to problems in our present-day world?

- How is the material related to your life, experiences, feelings and ideas? For instance, what emotions did the work arouse in you?

- Did the work increase your understanding of a particular issue? Did it change your perspective in any way?

- Evaluate the merit of the work: the importance of its points, its accuracy, completeness, organization, and so on.

- You should also indicate here whether or not you would recommend the work to others, and why.

POINTS OF CONSIDERATION WHEN WRITING THE REPORT

Here are some important elements to consider as you prepare a report:

- Apply the four basic standards of effective writing (unity, support, coherence, and clear, error-free sentences) when writing the report.

- Make sure each major paragraph presents and then develops a single main point. For example, in the sample report that follows, the first paragraph summarizes the book, and the three paragraphs that follow detail three separate reactions of the student writer to the book. The student then closes the report with a short concluding paragraph.

- Support any general points you make or attitudes you express with specific reasons and details. Statements such as "I agree with many ideas in this article" or "I found the book very interesting" are meaningless without specific evidence that shows why you feel as you do. Look at the sample report closely to see how the main point or topic sentence of each paragraph is developed by specific supporting evidence.

- Organize your material. Follow the basic plan of organization explained above: a summary of one or more paragraphs, a reaction of two or more paragraphs, and a conclusion. Also, use transitions to make the relationships among ideas in the paper clear.

- Edit the paper carefully for errors in grammar, mechanics, punctuation, word use, and spelling.

- Cite paraphrased or quoted material from the book or article you are writing about, or from any other works, by using the appropriate documentation style. If you are unsure what documentation style is required or recommended, ask you instructor.

- You may use quotations in the summary and reaction parts of the paper, but do not rely on them too much. Use them only to emphasize key ideas.

- Publishing information can be incorporated parenthetically or at the bottom of the page in a footnote. Consult with your instructor to determine what publishing information is necessary and where it should be placed.

A SAMPLE RESPONSE OR REACTION PAPER

Here is a report written by a student in an introductory psychology course. Look at the paper closely to see how it follows the guidelines for report writing described above.

Part 1: Summary

Document Actions

- Public Safety

- Website Feedback

- Privacy Policy

- CUNY Tobacco Policy

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- Presentations

How to Write a Seminar Paper

Last Updated: October 17, 2023 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Christopher Taylor, PhD . Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014. There are 16 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 619,572 times.

A seminar paper is a work of original research that presents a specific thesis and is presented to a group of interested peers, usually in an academic setting. For example, it might serve as your cumulative assignment in a university course. Although seminar papers have specific purposes and guidelines in some places, such as law school, the general process and format is the same. The steps below will guide you through the research and writing process of how to write a seminar paper and provide tips for developing a well-received paper.

Getting Started

- an argument that makes an original contribution to the existing scholarship on your subject

- extensive research that supports your argument

- extensive footnotes or endnotes (depending on the documentation style you are using)

- Make sure that you understand how to cite your sources for the paper and how to use the documentation style your professor prefers, such as APA , MLA , or Chicago Style .

- Don’t feel bad if you have questions. It is better to ask and make sure that you understand than to do the assignment wrong and get a bad grade.

- Since it's best to break down a seminar paper into individual steps, creating a schedule is a good idea. You can adjust your schedule as needed.

- Do not attempt to research and write a seminar in just a few days. This type of paper requires extensive research, so you will need to plan ahead. Get started as early as possible. [3] X Research source

- Listing List all of the ideas that you have for your essay (good or bad) and then look over the list you have made and group similar ideas together. Expand those lists by adding more ideas or by using another prewriting activity. [5] X Research source

- Freewriting Write nonstop for about 10 minutes. Write whatever comes to mind and don’t edit yourself. When you are done, review what you have written and highlight or underline the most useful information. Repeat the freewriting exercise using the passages you underlined as a starting point. You can repeat this exercise multiple times to continue to refine and develop your ideas. [6] X Research source

- Clustering Write a brief explanation (phrase or short sentence) of the subject of your seminar paper on the center of a piece of paper and circle it. Then draw three or more lines extending from the circle. Write a corresponding idea at the end of each of these lines. Continue developing your cluster until you have explored as many connections as you can. [7] X Research source

- Questioning On a piece of paper, write out “Who? What? When? Where? Why? How?” Space the questions about two or three lines apart on the paper so that you can write your answers on these lines. Respond to each question in as much detail as you can. [8] X Research source

- For example, if you wanted to know more about the uses of religious relics in medieval England, you might start with something like “How were relics used in medieval England?” The information that you gather on this subject might lead you to develop a thesis about the role or importance of relics in medieval England.

- Keep your research question simple and focused. Use your research question to narrow your research. Once you start to gather information, it's okay to revise or tweak your research question to match the information you find. Similarly, you can always narrow your question a bit if you are turning up too much information.

Conducting Research

- Use your library’s databases, such as EBSCO or JSTOR, rather than a general internet search. University libraries subscribe to many databases. These databases provide you with free access to articles and other resources that you cannot usually gain access to by using a search engine. If you don't have access to these databases, you can try Google Scholar.

- Publication's credentials Consider the type of source, such as a peer-reviewed journal or book. Look for sources that are academically based and accepted by the research community. Additionally, your sources should be unbiased.

- Author's credentials Choose sources that include an author’s name and that provide credentials for that author. The credentials should indicate something about why this person is qualified to speak as an authority on the subject. For example, an article about a medical condition will be more trustworthy if the author is a medical doctor. If you find a source where no author is listed or the author does not have any credentials, then this source may not be trustworthy. [12] X Research source

- Citations Think about whether or not this author has adequately researched the topic. Check the author’s bibliography or works cited page. If the author has provided few or no sources, then this source may not be trustworthy. [13] X Research source

- Bias Think about whether or not this author has presented an objective, well-reasoned account of the topic. How often does the tone indicate a strong preference for one side of the argument? How often does the argument dismiss or disregard the opposition’s concerns or valid arguments? If these are regular occurrences in the source, then it may not be a good choice. [14] X Research source

- Publication date Think about whether or not this source presents the most up to date information on the subject. Noting the publication date is especially important for scientific subjects, since new technologies and techniques have made some earlier findings irrelevant. [15] X Research source

- Information provided in the source If you are still questioning the trustworthiness of this source, cross check some of the information provided against a trustworthy source. If the information that this author presents contradicts one of your trustworthy sources, then it might not be a good source to use in your paper.

- Give yourself plenty of time to read your sources and work to understand what they are saying. Ask your professor for clarification if something is unclear to you.

- Consider if it's easier for you to read and annotate your sources digitally or if you'd prefer to print them out and annotate by hand.

- Be careful to properly cite your sources when taking notes. Even accidental plagiarism may result in a failing grade on a paper.

Drafting Your Paper

- Make sure that your thesis presents an original point of view. Since seminar papers are advanced writing projects, be certain that your thesis presents a perspective that is advanced and original. [18] X Research source

- For example, if you conducted your research on the uses of relics in medieval England, your thesis might be, “Medieval English religious relics were often used in ways that are more pagan than Christian.”

- Organize your outline by essay part and then break those parts into subsections. For example, part 1 might be your introduction, which could then be broken into three sub-parts: a)opening sentence, b)context/background information c)thesis statement.

- For example, in a paper about medieval relics, you might open with a surprising example of how relics were used or a vivid description of an unusual relic.

- Keep in mind that your introduction should identify the main idea of your seminar paper and act as a preview to the rest of your paper.

- For example, in a paper about relics in medieval England, you might want to offer your readers examples of the types of relics and how they were used. What purpose did they serve? Where were they kept? Who was allowed to have relics? Why did people value relics?

- Keep in mind that your background information should be used to help your readers understand your point of view.

- Remember to use topic sentences to structure your paragraphs. Provide a claim at the beginning of each paragraph. Then, support your claim with at least one example from one of your sources. Remember to discuss each piece of evidence in detail so that your readers will understand the point that you are trying to make.

- For example, in a paper on medieval relics, you might include a heading titled “Uses of Relics” and subheadings titled “Religious Uses”, “Domestic Uses”, “Medical Uses”, etc.

- Synthesize what you have discussed . Put everything together for your readers and explain what other lessons might be gained from your argument. How might this discussion change the way others view your subject?

- Explain why your topic matters . Help your readers to see why this topic deserve their attention. How does this topic affect your readers? What are the broader implications of this topic? Why does your topic matter?

- Return to your opening discussion. If you offered an anecdote or a quote early in your paper, it might be helpful to revisit that opening discussion and explore how the information you have gathered implicates that discussion.

- Ask your professor what documentation style he or she prefers that you use if you are not sure.

- Visit your school’s writing center for additional help with your works cited page and in-text citations.

Revising Your Paper

- What is your main point? How might you clarify your main point?

- Who is your audience? Have you considered their needs and expectations?

- What is your purpose? Have you accomplished your purpose with this paper?

- How effective is your evidence? How might your strengthen your evidence?

- Does every part of your paper relate back to your thesis? How might you improve these connections?

- Is anything confusing about your language or organization? How might your clarify your language or organization?

- Have you made any errors with grammar, punctuation, or spelling? How can you correct these errors?

- What might someone who disagrees with you say about your paper? How can you address these opposing arguments in your paper? [26] X Research source

Features of Seminar Papers and Sample Thesis Statements

Community Q&A

- Keep in mind that seminar papers differ by discipline. Although most seminar papers share certain features, your discipline may have some requirements or features that are unique. For example, a seminar paper written for a Chemistry course may require you to include original data from your experiments, whereas a seminar paper for an English course may require you to include a literature review. Check with your student handbook or check with your advisor to find out about special features for seminar papers in your program. Make sure that you ask your professor about his/her expectations before you get started as well. [27] X Research source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- When coming up with a specific thesis, begin by arguing something broad and then gradually grow more specific in the points you want to argue. Thanks Helpful 23 Not Helpful 11

- Choose a topic that interests you, rather than something that seems like it will interest others. It is much easier and more enjoyable to write about something you care about. Thanks Helpful 6 Not Helpful 1

- Do not be afraid to admit any shortcomings or difficulties with your argument. Your thesis will be made stronger if you openly identify unresolved or problematic areas rather than glossing over them. Thanks Helpful 13 Not Helpful 6

- Plagiarism is a serious offense in the academic world. If you plagiarize your paper you may fail the assignment and even the course altogether. Make sure that you fully understand what is and is not considered plagiarism before you write your paper. Ask your teacher if you have any concerns or questions about your school’s plagiarism policy. Thanks Helpful 7 Not Helpful 2

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://umweltoekonomie.uni-hohenheim.de/fileadmin/einrichtungen/umweltoekonomie/1-Studium_Lehre/Materialien_und_Informationen/Guidelines_Seminar_Paper_NEW_14.10.15.pdf

- ↑ https://www.bestcolleges.com/blog/how-to-ask-professor-feedback/

- ↑ http://www.law.georgetown.edu/library/research/guides/seminar_papers.cfm

- ↑ https://www.stcloudstate.edu/writeplace/_files/documents/writing%20process/choosing-and-narrowing-an-essay-topic.pdf

- ↑ http://writing.ku.edu/prewriting-strategies

- ↑ http://www.kuwi.europa-uni.de/en/lehrstuhl/vs/politik3/Hinweise_Seminararbeiten/haenglish.html

- ↑ https://guides.lib.uw.edu/research/faq/reliable

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/673/1/

- ↑ http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/thesis-statements/

- ↑ https://www.irsc.edu/students/academicsupportcenter/researchpaper/researchpaper.aspx?id=4294967433

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/engagement/2/2/58/

- ↑ http://writingcenter.fas.harvard.edu/pages/beginning-academic-essay

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/589/02/

- ↑ https://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/561/05/

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/Handbook/ReverseOutlines.html

About This Article

To write a seminar paper, start by writing a clear and specific thesis that expresses your original point of view. Then, work on your introduction, which should give your readers relevant context about your topic and present your argument in a logical way. As you write, break up the body of your paper with headings and sub-headings that categorize each section of your paper. This will help readers follow your argument. Conclude your paper by synthesizing your argument and explaining why this topic matters. Be sure to cite all the sources you used in a bibliography. For advice on getting started on your seminar paper, keep reading. Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Mehammed A.

Dec 28, 2023

Did this article help you?

Patrick Topf

Jul 4, 2017

Flora Ballot

Oct 10, 2016

Igwe Uchenna

Jul 19, 2017

Saudiya Kassim Aliyu

Oct 11, 2018

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

How to Write a Reaction Paper

Published by gudwriter on February 1, 2021 February 1, 2021

If you hear about a reaction or response paper for the first time, you should read this piece to the very end. If this is new to you, then you might probably be wondering what a reaction paper entails. For many college students, this is no new thing. Reaction papers are quite common in college and even after.

Elevate Your Writing with Our Free Writing Tools!

Did you know that we provide a free essay and speech generator, plagiarism checker, summarizer, paraphraser, and other writing tools for free?

We often come across response papers daily, but we do not recognize them. An excellent example of a reaction paper can be found in newspaper sections that we read daily. In college, these types of essays are often given as assignments. In a reaction paper, one is expected to express what they feel or think about a particular subject or a specific occurrence.

How easy is it to write a reaction paper? Response papers, as they are also called, are by far the simplest literary materials to write. It is almost like a form of mental exercise except for the fact that you have to write your thoughts down. If you consider yourself a creative person, this should be relatively easy and straightforward, but if you are facing a hard time crafting a quality paper, Gudwriter has the best custom speech writing service with a pool of experts ready to help you at any time.

When writing a reaction paper, you write about your feelings, thoughts, and points of view. When writing such a paper, there are a few pointers to guide you on how exactly you ought to go about putting your thoughts in writing. However, the general idea is merely expressing your reaction to a given subject matter or about something you have watched or read about.

Why did you choose this topic?

- What are your feelings towards this topic?

- Do you agree or disagree with this topic?

- What are some of the contentious points you agree or disagree with?

- Is the topic relatable?

- Are there lessons you can learn from this topic? What are they?

Learn the following;

- How to write a killer 300 word essay

- How to write a graduation speech

- Demonstration speech ideas

Making a Reaction Paper Format Properly

The secret to success in any essay writing lies in its outline. A reaction essay is made up of three main parts; Introduction, body, and conclusion. The outline of a reaction paper requires you to start by writing a summary of your ideas. After this, you proceed to the body where you pen down your points in detail. The third step is to include your reactions. This can be based on a piece related to your experience or on a personal

Steps in Writing a Reaction Paper

The essential thing we are always taught is to first organize yourself before attempting to try anything out. Planning is vital in essay writing since it enables you to break down a seemingly complex assignment into more manageable units. Before embarking on writing an essay, it is essential first to develop your idea about how you want the essay to look like.

An outline gives you guidelines on how exactly you ought to go about arranging your ideas. Thorough research on your subject topic is vital since it reinforces your main points and arguments. It is essential to conduct adequate research beforehand so that you can easily pen down your thoughts. An outline serves to remind the author to remain relevant to the topic and arrange one’s thoughts in such a way that to total required word count of the essay is not exceeded.

A title is the first introductory part of your paper that readers come into contact with. Often, the secret behind a good and a bad reaction paper lies in the crafting of the title. For example, in a magazine, a catchy title determines whether a reader will take an interest in the contents of a reaction paper or not. The same is true for any other paper you write. You, therefore, ought to come up with a title that grabs the attention of the reader while simultaneously addressing the contents of your paper. How creative and catchy your title is, determines a reader’s next cause of action. Get creative titles generated by our free title generator .

For instance, ‘ Dynamics of a Management Seminar. ’

2. Introduction

An introduction comes immediately after your title. The primary purpose of an introduction is to compel your reader to delve more into your work. You ought to craft your work in such a way that it captures the attention of the reader further. Failure to do this means that you are giving your reader less motivation to continue reading. .The number one secret behind a catchy introduction is to keep your first sentences short and exciting. It cannot be emphasized enough just how important it is to make your sentences short and sweet.

Readers don’t like going through lengthy and complicated sentences when they start reading written material. Often, long and complex sentences lower the interest levels of readers who might have initially been interested in reading your work. It is, therefore, appropriate that you make your sentences punchy and easily digestible. For a 500 word paper , the introduction ought to take up roughly 100 words. The introduction should entail a title, copyright details of your information source, and a short description of your topic.

A reaction statement should be the last part of the introduction, and it ought to be clear and focused. It is usually just one statement, and therefore, it ought to be concise and on point.

Eye-capturing thesis statement: A management seminar entails dialogues and presentations where speakers have profound knowledge in their subject and share that knowledge effectively.

Other supportive sentences : For most people, hearing the word ‘seminar’ makes their mind drift towards a boring setting where a speaker is giving a presentation to a half attentive group of people. According to Wikipedia, seminars are types of academic events in a given institution where the main agenda is to gather groups of people for meetings on given subject matters.

The body is supposed to be the longest part of your paper for a reason. It is here that you get to support your arguments and main points. You ought to craft your body in such a way that it captivates readers. Each of your points in such a paper should be in its paragraph, and the paragraph should be balanced in terms of length.

For example

In a recent seminar, a top speaker spoke about how tourism company managers can do more to promote sustainability in tourism. In the tourism industry, the benefits of sustainability are wide-ranging, and there is a need for increased adoption of sustainability (kent, 2018). What makes the seminar interesting is not just the content you learn from the speaker but also the overall experience you get from it (Merccado, 2017). We ought to embrace seminars since that is one of the places where you can get incredible amounts of management content from the best minds

4. Conclusion

A conclusion is the final part of a reaction paper. In this part, you write a recap of the ideas you talked about in the body. In this section, you describe all the points that discuss in your body; you can then write the conclusion.

Example of a conclusion

Management seminars are diverse and cover a wide range of issues. The methods used in conveying information are also diverse. A speaker may choose to use PowerPoint to present or even regular lectures. What is often regarded as necessary is the level of satisfaction of all participants.

Tips and Pointers on Writing a Reaction Paper

1. proofread for errors.

Regardless of how careful we are, we are always bound to make mistakes. Even if you feel your work is faultless, it is prudent to double-check your work. It is essential since it helps you correct any errors you may have made. It takes less than 10 minutes to proofread your work. You should always make sure that you do this for all your papers.

2. Plagiarism

When you directly copy someone’s ideas or literary work, that action is referred to as Plagiarism. In essay writing, plagiarized work is deemed not credible and lacking in authenticity. People love original material that is free from any duplication. When writing a reaction paper, you must cite any form of information you use from an external source and further give a list of all the sources of information used.

You have often heard that what you say is never as important as how you say it. When it comes to writing these types of papers, the same is equally true. How you craft your work is so vital that it has the power to either keep a reader reading or making the reader less enthusiastic about reading your work. You ought to use a combination of both descriptive words and simple language that will keep a reader glued to your work.

To adequately capture your reader’s attention to the very end, your ideas should be free-flowing and exciting. In this type of paper, readers like work that flows smoothly towards a logical conclusion.

Explore some of the tips on becoming a successful content writer .

Mistakes to Avoid When Writing a Reaction Paper

Like in other writing types, people are bound to make mistakes when writing a reaction paper. However, versing yourself with some of the common mistakes made in these papers means that you don’t have to make them.

1. Summarizing the source

The objective of a reaction paper is not to summarize the source of your content. Having this in mind as you start your paper will be your saving grace. Instead, you should read the content and analyze it adequately, after which you should come up with your own opinion on the problem and suggest a probable solution.

2. Using irrelevant examples

As earlier indicated, reaction papers are intensive on examples. However, this does not mean that you can pick just any example and include it in your essay. Only relevant and reliable evidence should be used to support your opinion, or support the solutions you provide for a problem. Using examples is beneficial; however, using reliable ones will help you nail your paper.

3. Always supporting the author of your source

Reaction papers are written based on already existing work. However, you are not bound to supporting the ideas in a given content. Reaction papers allow you to be creative and give you the opportunity to develop your own opinions on a subject and argue them out.

The number one secret to writing a good research paper is first planning your work. It is as simple as that! When your work is planned well with introduction, body, and conclusion segments, ideas start to flow naturally, and before you know it, you have a masterpiece.

Special offer! Get 20% discount on your first order. Promo code: SAVE20

Related Posts

Free essay guides, how to write a graduation speech.

What is a Graduation Speech? A graduation speech is delivered at the graduation event to congratulate the graduates and provide them with advice and motivation. The speaker could be a student or professor. Your chance Read more…

Free TEAS Practice Test

Study and prepare for your TEAS exam with our free TEAS practice test. Free ATI TEAS practice tests are valuable resources for those hoping to do well on their TEAS exams. As we all know, Read more…

How to Write a Profile Essay

To learn how to write a profile essay, you must first master where to begin. Given that this is a profile essay, it will be much simpler for students who have previously read autobiographical articles Read more…

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Open access

- Published: 26 March 2024

Ecological countermeasures to prevent pathogen spillover and subsequent pandemics

- Raina K. Plowright ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3338-6590 1 ,

- Aliyu N. Ahmed ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6039-1101 2 ,

- Tim Coulson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9371-9003 3 ,

- Thomas W. Crowther ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5674-8913 4 ,

- Imran Ejotre 5 ,

- Christina L. Faust ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8824-7424 6 ,

- Winifred F. Frick ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9469-1839 7 , 8 ,

- Peter J. Hudson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0468-3403 9 ,

- Tigga Kingston ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3552-5352 10 ,

- P. O. Nameer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7110-6740 11 ,

- M. Teague O’Mara ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6951-1648 7 ,

- Alison J. Peel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3538-3550 12 ,

- Hugh Possingham ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7755-996X 13 ,

- Orly Razgour ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3186-0313 14 ,

- DeeAnn M. Reeder ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8651-2012 15 ,

- Manuel Ruiz-Aravena ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8463-7858 1 , 12 nAff26 ,

- Nancy B. Simmons ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8807-7499 16 ,

- Prashanth N. Srinivas ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0968-0826 17 ,

- Gary M. Tabor ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4711-1018 18 ,

- Iroro Tanshi 19 , 20 , 21 ,

- Ian G. Thompson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3445-8696 22 ,

- Abi T. Vanak ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2435-4260 23 , 24 ,

- Neil M. Vora ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4989-3108 25 ,

- Charley E. Willison ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7272-1080 1 &

- Annika T. H. Keeley ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7237-6259 18

Nature Communications volume 15 , Article number: 2577 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

7282 Accesses

751 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Epidemiology

- Policy and public health in microbiology

- Viral infection

Substantial global attention is focused on how to reduce the risk of future pandemics. Reducing this risk requires investment in prevention, preparedness, and response. Although preparedness and response have received significant focus, prevention, especially the prevention of zoonotic spillover, remains largely absent from global conversations. This oversight is due in part to the lack of a clear definition of prevention and lack of guidance on how to achieve it. To address this gap, we elucidate the mechanisms linking environmental change and zoonotic spillover using spillover of viruses from bats as a case study. We identify ecological interventions that can disrupt these spillover mechanisms and propose policy frameworks for their implementation. Recognizing that pandemics originate in ecological systems, we advocate for integrating ecological approaches alongside biomedical approaches in a comprehensive and balanced pandemic prevention strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

The role of environmental factors on transmission rates of the COVID-19 outbreak: an initial assessment in two spatial scales

Canelle Poirier, Wei Luo, … Mauricio Santillana

Pathogen spillover driven by rapid changes in bat ecology

Peggy Eby, Alison J. Peel, … Raina K. Plowright

A generalizable one health framework for the control of zoonotic diseases

Ria R. Ghai, Ryan M. Wallace, … Casey Barton Behravesh

Introduction

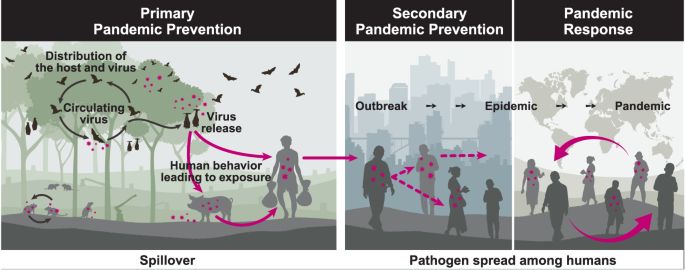

Reducing the risk of future pandemics requires investment in prevention, preparedness, and response. At present, most attention and funding is allocated to mitigation after a pathogen is already circulating in humans, prioritizing outbreak detection and medical countermeasures such as vaccines and therapeutics 1 . By contrast, primary pandemic prevention—defined as reducing the likelihood a pathogen transmits from its animal host into humans (zoonotic spillover; Fig. 1 ) 2 —has received less attention in global conversations, policy guidance, and practice 1 , 2 . Given the time delays in identifying and responding to outbreaks, and the inequity in treatment distributions, investing in pandemic prevention is essential to achieve efficient, equitable, and cost-effective protection from disease.

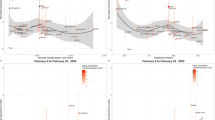

Primary pandemic prevention is the set of actions taken to reduce the risk of pathogen spillover from animals to humans, focusing on processes upstream of the spillover event (left panel). By contrast, secondary pandemic prevention (middle panel) focuses on limiting the spread of an outbreak to prevent its escalation into an epidemic or a pandemic. Pandemic response (right panel) involves actions taken to address a pandemic once one is underway. Although not illustrated here, pandemic preparedness involves developing capabilities to respond to a pandemic if one were to occur, and can be implemented concurrently with primary and secondary pandemic prevention. The nature of interventions varies across these phases: Primary pandemic prevention emphasizes ecological and behavioral interventions, but also encompasses biosafety practices in virological research 83 , whereas secondary pandemic prevention and response prioritize epidemiological and biomedical interventions. Definitions: an outbreak is “an increase, often sudden, in the number of cases of a disease in a particular area 84 ”; an epidemic is an outbreak extending over a wider geographic area 84 ; and a pandemic is “an epidemic occurring worldwide, or over a very wide area, crossing international boundaries and usually affecting a large number of people 84 ”.

To effectively prevent pandemics, we must recognize two key points: first that pandemics almost always start with a microbe infecting a wild animal in a natural environment and second that human-caused land-use change often triggers the events–whether through wildlife trade or other distal activities–that facilitate spillover of microbes from wild animals to humans 3 . As land-use change becomes more intense and extensive, the risk of zoonotic spillovers, and subsequent epidemics and pandemics, will increase. Designing land management and conservation strategies to explicitly limit spillover is central to meeting the challenge of pandemic prevention at a global scale.

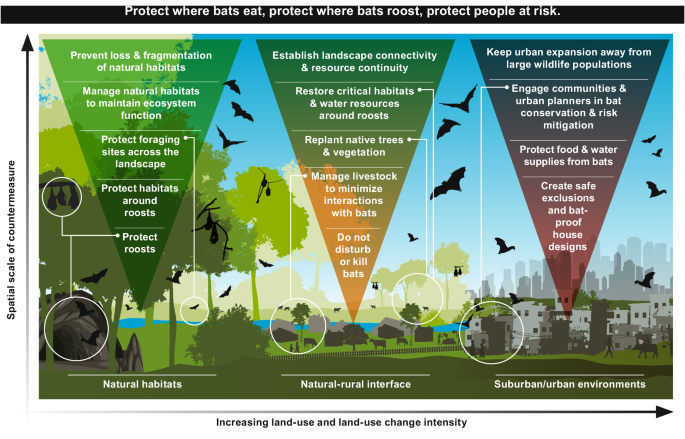

Herein, we present a roadmap for reducing pathogen transmission from wildlife to humans and other animals. We show how strategic conservation and restoration of nature for reservoir hosts, and mitigation of risks for humans most at risk—what we define as ecological countermeasures—can prevent spillover and protect human and animal health, while also addressing key drivers of climate change and biodiversity loss.

Mechanisms of spillover

Despite hundreds of thousands of potentially zoonotic microbes circulating in nature 4 , pandemics are rare. Microbes, termed pathogens if they cause disease, must overcome a series of barriers, simplified and described below, to transmit from a wild animal to a human. Crossing those barriers requires the alignment of specific conditions—including ecological, epidemiological, immunological, and behavioral conditions—that are often complex and dynamic 5 .

First, the distribution of the species that maintains the zoonotic pathogen in nature (the reservoir host) and the species that is infected (the recipient host) must be connected, usually through overlapping distributions. Once wildlife reservoir hosts and humans overlap, the second barrier is the immune functions within wildlife hosts that keep potential zoonotic pathogens at low levels. Particular stressors (e.g., habitat loss, lack of food) can increase host viral infection and shedding 6 . A pathogen that passes through this second barrier and is shed by the animal host encounters a third barrier: humans must be exposed to a pathogen for spillover to occur. That exposure depends on specific interactions or behaviors of humans and the virus-shedding host. Exposure to the pathogen may be through direct contact, such as a bite, or indirect contact with the reservoir host’s excreta or a non-vertebrate vector (e.g., blood-feeding parasite). Often a bridging host species, such as commercially traded wildlife or a domestic animal, is infected by the reservoir host and subsequently amplifies and transmits the pathogen to humans. The fourth barrier is human susceptibility. The pathogen must be able to establish an infection within humans by overcoming structural and immunological barriers (e.g., binding to a human cell). Those barriers are substantial–one reason pandemics are rare–protecting humans from a continuous rain of microbes from soils, plants, and animals 5 . Fifth, after establishing an infection within a single human, the pathogen must be able to amplify within this new host, be excreted (e.g., through respiration), and then transmitted onward and exponentially 7 . If any of these barriers is not overcome, a pandemic cannot occur 5 .

Land use-induced spillover

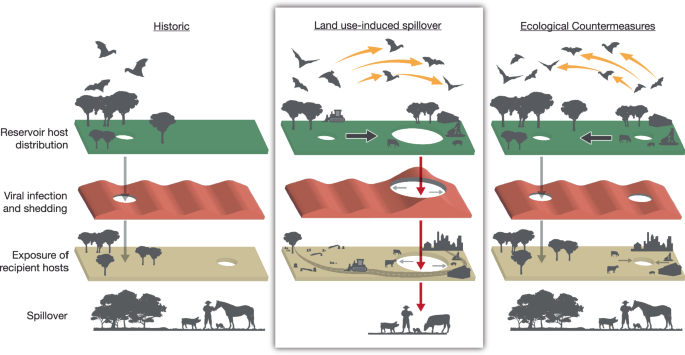

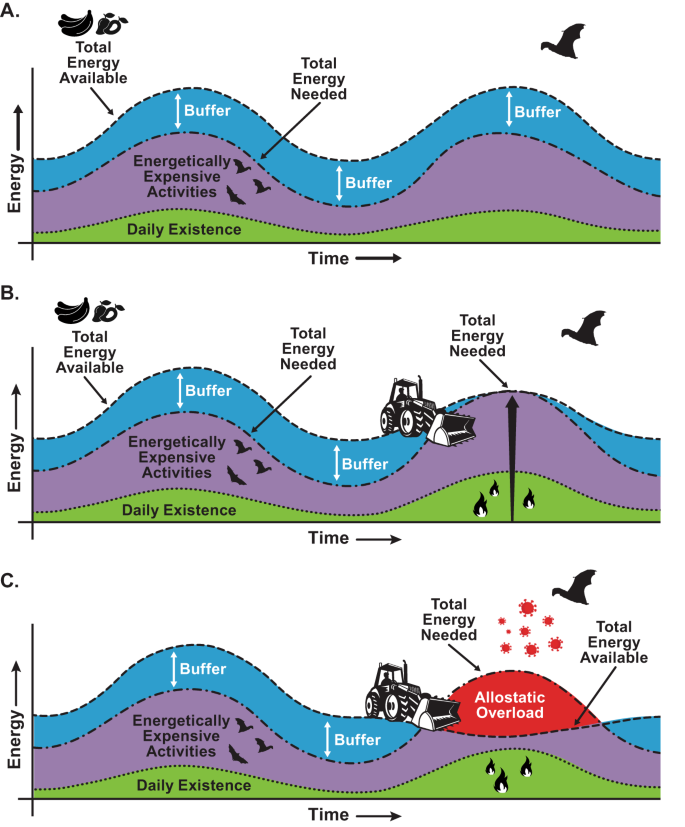

Intact ecosystems provide the first line of defense against new pandemics because they strengthen the first three barriers to spillover (minimizing distribution overlap, host stress, and human exposure) and hence decrease the likelihood that the conditions for spillover occur or align 3 . Conversely, land-use changes and other environmental disturbances erode those first three barriers to spillover by changing the reservoir hosts’ spatial behavior and allostatic load (energy and stress budget), as well as altering human behavior. In this context, we identify targeted ecological countermeasures designed to decrease these risks (Fig. 2 ).

Historic (left panel): Historically, reservoir hosts and large human populations (and their domestic animals) were more separated, viruses circulated at low levels with seasonal fluctuations in prevalence, and the holes in the barriers to spillover were small and did not align 5 . Land use-induced spillover (middle panel): Land-use change increases the risk of spillover by driving two phenotypic changes in reservoir hosts: changes in behavior that alter how they use space, and changes in reservoir host energy and stress levels (allostatic load) that influence viral infection and shedding. Land-use change can also lead to emergent human behaviors that increase exposure to pathogens. Land-use change generally increases the overlap of reservoir, human, and bridging hosts; increases the probability that reservoir hosts are shedding pathogens; and increases the probability that humans are exposed to those pathogens. In sum, these changes increase the size and alignment of the holes in the barrier to spillover. Ecological countermeasures (right panel): Ecological countermeasures can address all three issues. Retaining natural resources reduces the overlap of humans and domestic recipient hosts in space and time, reduces the probability of allostatic overload and reduces the likelihood of emergent human behaviors that facilitate exposure.