Our travel boxes are selling out! Grab your Shop TODAY Staycation box for 63% off before it's gone

- TODAY Plaza

- Share this —

- Watch Full Episodes

- Read With Jenna

- Inspirational

- Relationships

- TODAY Table

- Newsletters

- Start TODAY

- Shop TODAY Awards

- Citi Concert Series

- Listen All Day

Follow today

More Brands

- On The Show

I visited the classroom where my son was killed 5 years ago. It’s still there — for now

In 2018, a 19-year-old former student shot and killed 17 people inside Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, in under four minutes. Th e shooter pled guilty and was sentenced to multiple life sentences in prison . Now the site of the shooting, the 1200 building on the school's campus, is scheduled to be demolished, but not before survivors and victims' families have a chance to walk through t he building .

Warning: This post contains graphic descriptions of a school shooting.

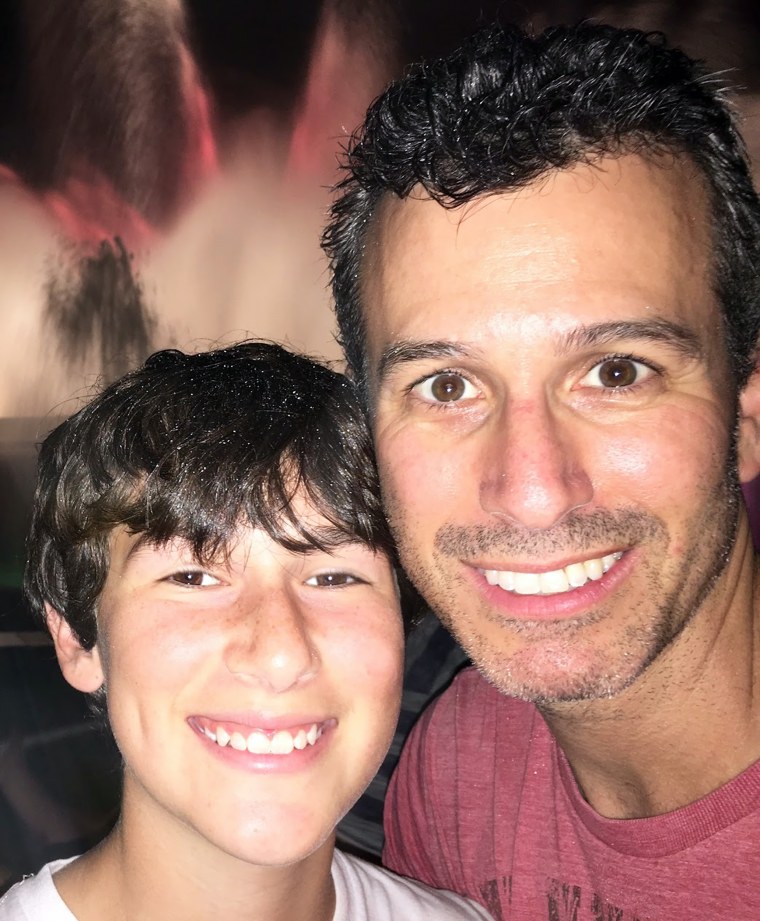

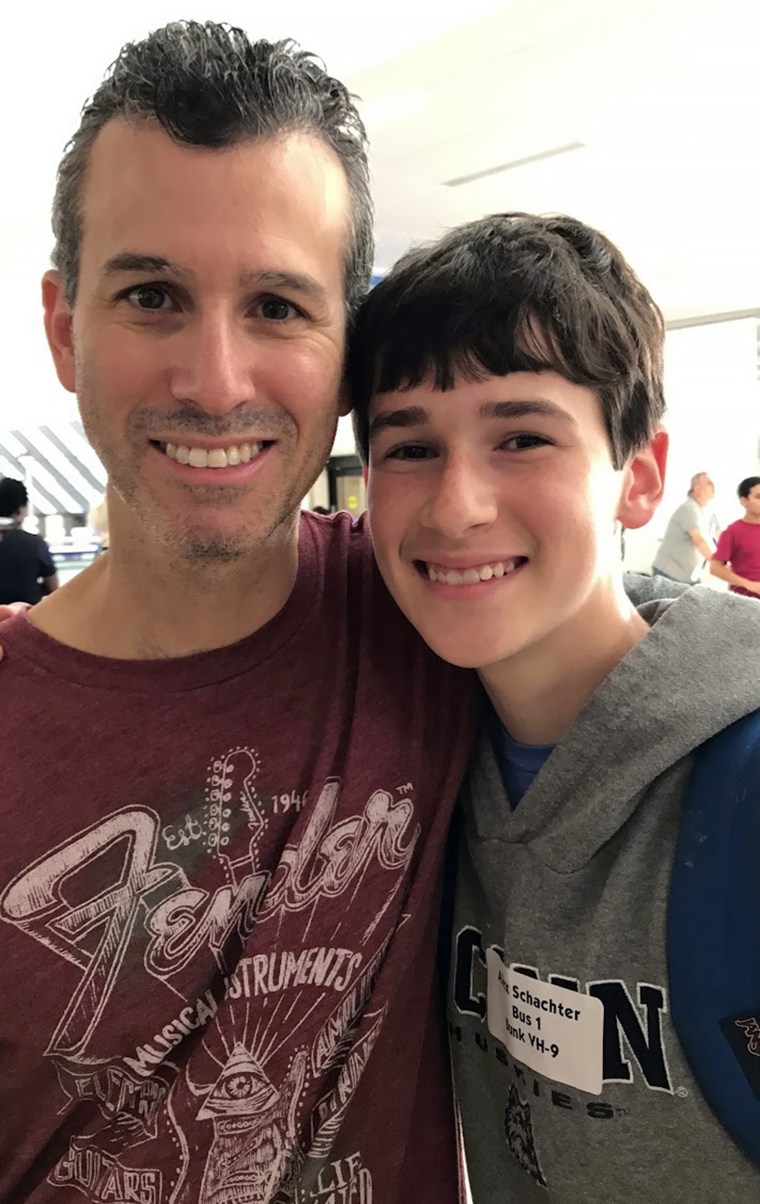

Feb. 14, 2018, was the last day I saw my son Alex Schachter alive.

"I love you, have a great day in school," were the last words I said to him.

It didn't occur to me that he could be murdered in his English class.

Later that day, a 19-year-old armed with an AR-15 entered my son's school, Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, and killed 17 people.

My forever 14-year-old Alex was one of them.

In the years since the shooting, the building was basically hermetically sealed off from the other buildings on campus — a perfectly preserved crime scene where only the bodies of the deceased were removed.

During the shooter's trial , the jury was led through the school — story by story, class by class — along the same route the shooter took as he hunted his victims.

At that time , I had never contemplated the possibility of one day visiting the school myself. Some of the surviving families wanted to know everything — to see the horrific crime scene photos and read the devastating autopsy reports.

In 2008, my then-wife passed away. I found her in bed one morning and couldn't wake her up. I thought that was the worst moment of my life, so after seeing her I promised myself I would never do that again.

I didn't identify Alex's body; I asked the kind people at the Star of David Funeral Home to do that for me. There were pictures I refused to see and places I would not let my brain go. It was just too painful.

Then I was given the opportunity to visit the school before it will be demolished , and something inside me shifted.

Something inside me shifted. I desperately needed to stand in the spot where my son took his last breath.

I desperately needed to stand in the spot where my son took his last breath.

I wanted to connect with Alex. I wanted to sit in the very chair he was sitting in when he was shot. I wanted to know exactly what happened, exactly how he died and to maybe, just maybe, have all my lingering questions answered.

The morning of Thursday, July 6, ahead of my visit, I re-watched the prosecution's closing arguments of the murder trial . Attorney Michael "Mike" Satz was methodical, taking us room by room and shot by shot.

I also re-watched the medical examiner's testimony of Alex's injuries. I had heard it that day, in the courtroom, but I couldn't process it. Instead, I was crying so uncontrollably that the defense tried to declare a mistrial.

After the videos, I put on my Alex T-shirt, my "Safe Schools For Alex" hat and my jacket — I knew my always thoughtful boy Alex would want me to wear a jacket — and drove to the school.

My family members and friends were concerned. I fielded phone calls from my wife, my three surviving children, my father and dear friends who volunteered to go with me.

I knew the visit was something I had to do, and I knew I had to do it alone. I simply did not want to burden anyone else with the horror I was about to see.

I parked at the school and walked into the gym. I was greeted by the victims advocates and the entire prosecutorial team, all sitting and waiting for me.

As I prepared to begin my walk-through, Debbie Hixon, who lost her husband Chris Hixon in the shooting , was finishing hers.

Debbie and I embraced, talked for a few minutes and then I went into the first hallway the shooter entered on that fateful day.

There was broken glass everywhere. Mike, the prosecutor, began describing the murderer's path, including where he took his first shots.

I saw the spot where Gina Montalto was shot and killed . She was sitting outside her classroom because she wanted a quiet space to work.

Luke Hoyer and Martin Duque were near her, returning to their class after running an errand. They were knocking on their classroom door when they were shot and killed — all described to me as it was during the murder trial.

Then Mike took me into Alex's room. I wasn't prepared for what I saw.

There was blood everywhere. Some part of my mind — the part, perhaps, that has been working so hard for the past five years to protect the shattered pieces of my heart — thought the blood would have evaporated somehow.

But Alex's chair was covered in his blood. In my baby's blood.

Mike then told me, step-by-step, what happened to Alex.

Alex must have heard the shots from the hallway. He had stood up from his desk when the murderer shot him through the classroom door window, striking my son twice in the chest. His spinal cord was severed and he died instantly.

My son had been sitting with three other kids. All four were shot.

The shooter returned to Alex's classroom after firing into the hallway. It was then that he shot and killed my son's classmates, Alaina Petty and Alyssa Alhadeff, while they were hiding.

An English paper Alex had been working on still laid on the floor near his desk. As I went down to pick it up someone asked if I wanted gloves because it had Alex's blood on it.

"No, I don't care," I responded. "It's my little boy's blood."

I then gathered the rest of my son's papers and his English book, still underneath his desk, to take home.

I couldn't bring myself to sit in Alex's chair. There was just too much blood on it. I have requested that I be allowed to take it home.

It's unbelievable, the carnage inflicted in a matter of minutes. As I walked through the rest of the school where 17 people were killed and 17 others wounded, I felt sick.

I was also angry.

Since my son's murder, I have dedicated my life to ensuring schools are safer for our children. Twenty-three days after the shooting, I helped pass the Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Act in Florida, and schools are safer as a result.

With Alex on my shoulder, I joined the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Commission. The Luke and Alex School Safety Act was included in the 2022 Bipartisan Safer Communities Act.

I helped create SchoolSafety.gov , the federal school safety clearinghouse working to make schools a safe place to learn nationwide.

I also created a charity, Safe Schools for Alex . I have no plan of slowing down.

After seeing the spot where my son was murdered, now more than ever I am convinced that every elected leader needs to walk through the crime scenes of mass shootings in their communities. Those in power must come down from their ivory towers to understand the implications of not prioritizing safety and security above all else.

And I must continue to explain to people that safety must come before education, because you can't teach dead kids.

My son was a funny kid who loved to watch football and basketball. He was a talented musician who loved music from the '70s — his favorite song was Chicago's "25 or 6 to 4."

Alex was also an adoring big brother, who would let his little sister comb his hair while he played video games, and who loved his older brother and sister so much.

He should be here. He should be a thriving 20-year-old.

I know he was scared. He stood up to try and escape the gunfire but he didn't have the time.

I hope and pray he didn't suffer.

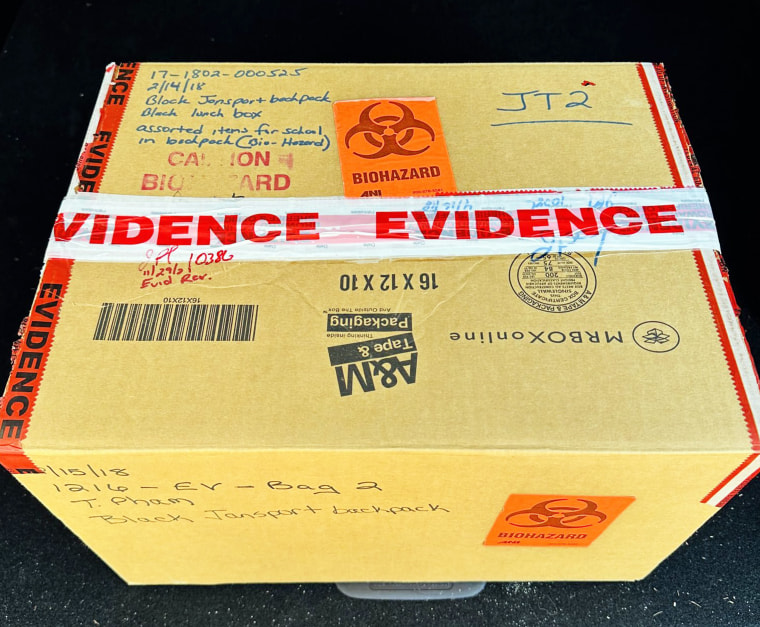

Days after I stood in the spot where my son took his last breath, I received two additional items that belonged to Alex . In a box labeled "evidence" and "biohazard" was Alex's book bag and lunch box. I was told it's a "biohazard" because it has my son's blood on it and potentially has bullet holes.

I can't bring myself to open it.

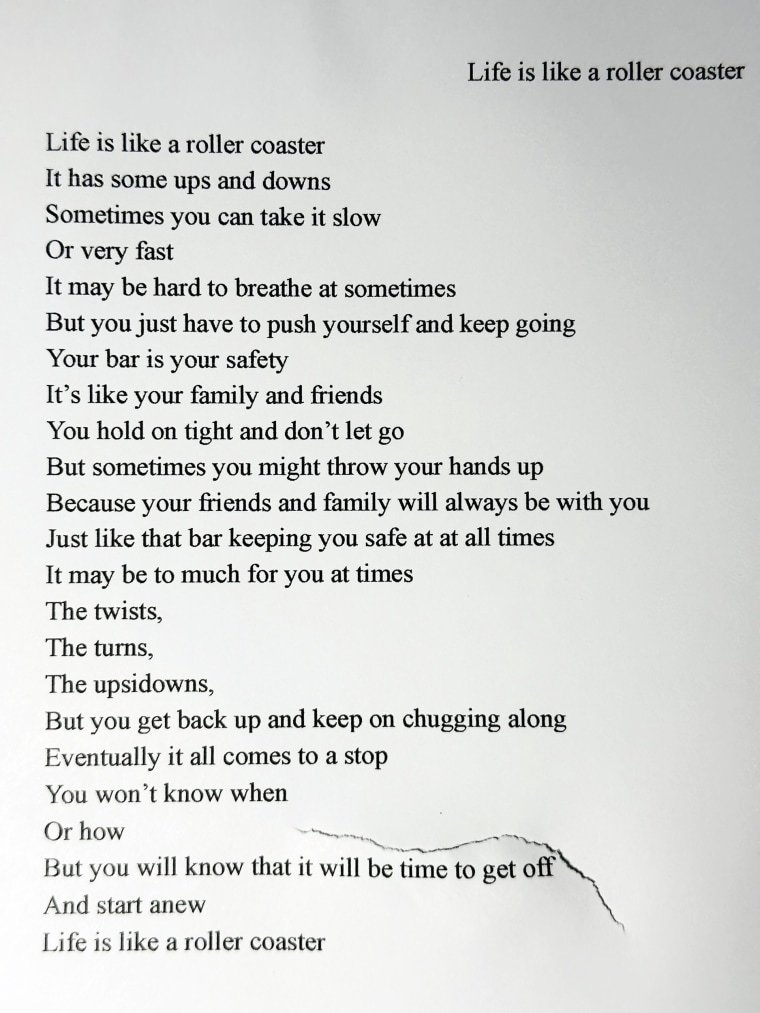

I also received the final draft of a poem Alex turned into his teacher before he was murdered. It's titled "Life is Like a Roller Coaster." My son, Ryan, found a crumpled up rough draft of the same poem in Alex's wastebasket the night before his funeral.

His final poem was pierced by a bullet.

As told to Danielle Campoamor

Max Schachter is an advocate for safe schools. His son Alex was killed in a 2018 school shooting in Parkland, Florida.

Watch CBS News

How the Parkland school shooter may have talked himself into a death sentence: "One of the state's best witnesses"

October 10, 2022 / 10:10 AM EDT / CBS/AP

It's possible the Florida school shooter who killed 17 people at Parkland 's Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School has talked himself into a death sentence.

Prosecutors played video last week at Nikolas Cruz's penalty trial of jailhouse interviews he did this year with two of their mental health experts. In frank and sometimes graphic detail, he answered their questions about his Feb. 14, 2018, massacre — his planning, his motivation, the shootings.

While it can't be known what the 12 jurors are thinking, if any are wavering between voting for death or life without parole, his statements to Dr. Charles Scott, a forensic psychiatrist, and Robert Denney, a neuropsychologist, did not help his cause.

"All of this made Cruz himself perhaps one of the state's best witnesses," said David S. Weinstein, a Miami defense attorney and former prosecutor who has been monitoring the trial.

The jury will likely decide his fate this week. For the 24-year-old to get a death sentence, the jury must be unanimous on at least one victim. But if all 17 counts come back with at least one vote in favor of life in prison, then that would be his sentence. Closing arguments are scheduled Tuesday, with deliberations beginning Wednesday.

The 12 jurors and 10 alternates who will decide whether he gets the death penalty or life in prison made a rare visit to the massacre scene in August, retracing his steps through the three-story freshman building, known as "Building 12." After they left, a group of journalists — including CBS Miami's Joan Murray — was allowed in for a much quicker first public view.

"It was really frozen in time," Murray said.

Because the defense is that his birth mother's heavy drinking during pregnancy left him brain-damaged, prosecutors could have experts examine him for their rebuttal case.

Scott and Denney interviewed him separately for several hours. In each, he sat across the table, handcuffed, a sweater draped over his chest. He sometimes asked for a pen and paper to add diagrams and drawings to his explanations.

"The question is: What will the jury take away from the interviews? Cold-blooded killer who was vengeful and excited about the murders, or a person so hopelessly deranged that he can't be anything but crazy?" said Bob Jarvis, a professor at Nova Southeastern University's law school.

Excerpts from those interviews, some of which are graphic:

How long had he been contemplating a school shooting?

"A very long time," the defendant told Scott, starting when he was 13 or 14, about five years before he did it.

"It was just a thought. I was reading books," he said. "It would come and go. It would pop up in my mind."

The thoughts would return when he watched violent videos, particularly documentaries about mass shootings at Colorado's Columbine High School, Virginia Tech and elsewhere, he said.

How did he plan the massacre?

"I did my own research," the defendant told Scott. "I studied mass murderers and how they did it, their plans, what they got and what they used."

He detailed the lessons he learned: Watch for would-be rescuers coming around corners, keep some distance from your targeted victims, attack as fast as possible - and "the police didn't do anything."

"I have a small opportunity to shoot people for maybe 20 minutes," he said.

How did he prepare?

He told Scott he put his AR-15-style semi-automatic rifle in a bag the night before and slipped its magazines into a shooting vest. He adjusted the gun's sights and imagined what the recoil would feel like.

"I didn't get any sleep," he said.

He donned the burgundy polo shirt he received when he was a member of the Stoneman Douglas Junior Reserve Officer Training Corps program so he could escape by mingling with fleeing students.

"If I had all my (shooting) gear on, they would have called the cops," he said.

When he set out at 2 p.m., he told the Uber driver he was in the school orchestra and the bag carried his instrument.

What did he do when he arrived?

"I walked through the gates. Hopefully, there would be no security guards, but I was wrong," he told Scott. "I was looking at the guy and he was watching me."

When he attended Stoneman Douglas, guards frequently checked him for weapons because of his erratic and sometimes violent behavior. When he was expelled a year before the shooting, a guard predicted he would eventually return and shoot people.

Fearing he'd been discovered, he sprinted into a three-story classroom building and quickly assembled his weapon. He told a student who happened upon him to flee because something bad was about to happen.

He then went floor to floor, shooting down hallways and into classrooms, firing 140 shots in all.

"I thought they would scream," he said about his first three victims. He shot them point-blank outside a locked classroom door. "It was more like they passed out and blood came pouring out of their head. It was really nasty and sad to see."

But he continued.

"I think I showed mercy to three girls. I was going to walk away, but they showed nasty faces and I went back," he said. "I thought they were going to attack me."

He shot several of his victims a second time after they fell, including his final one - a student writhing from a leg wound. He said the boy "gave me a nasty look. A look of anger."

"His head blew up like a water balloon," he said.

Why did he stop shooting?

Students and teachers fled the building or locked themselves in classrooms. The third-floor hallway was now empty except for victims.

"I couldn't find anyone to kill," he said. "I didn't want to do it anymore and I didn't think there was anyone else in the building."

He dropped his gun and vest on the stairwell and fled. He was captured an hour later - the police officer had been looking for a young male in a Stoneman Douglas ROTC polo.

His final say

As Denney was finishing the final interview, he asked the defendant if there was anything else he should know. He thought for 10 seconds before responding: "Why I chose Valentine's Day."

"Because I thought no one would love me," he explained. "I didn't like Valentine's Day and I wanted to ruin it for everyone."

"Do you mean for the family members of the kids that were killed?" Denney asked.

"No, for the school," he replied.

The holiday will never be celebrated there again, he said.

- Parkland School Shooting

- Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School

More from CBS News

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How the Survivors of Parkland Began the Never Again Movement

By Emily Witt

.jpg)

By Sunday, only four days after the school shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, in Parkland, Florida, the activist movement that emerged in its aftermath had a name (Never Again), a policy goal (stricter background checks for gun buyers), and a plan for a nationwide protest (a March for Our Lives, scheduled for March 24th). It also had a panel of luminary teens who were reminding America that the shooting was not a freak accident or a natural disaster but the result of actual human decisions.

The funerals continued in Parkland and surrounding cities—for the students Jaime Guttenberg and Joaquin Oliver and Alex Schachter and the geography teacher Scott Beigel—with attendance sometimes surpassing a thousand people. On a local level, at least, the activism did not overshadow the grieving. The tragedy affected this student body of more than three thousand people in different ways: some students lost their closest friends, others hallway acquaintances. And the student leaders knew, with the clarity of thought that had distinguished them from the beginning, that the headline-industrial complex granted only a very narrow window of attention. Had they waited even a week to start advocating for change, the reporters would have gone home.

Also, different people express grief in different ways. The activists are grieving, too, but it’s not a coincidence that a disproportionate number of the Never Again leaders are dedicated members of the drama club. Cameron Kasky is a theatre kid. Before he went on Anderson Cooper, he was best known as a class clown. “I’m a talker,” he told me. “The only thing I’ve had this whole time is the fact that I never shut up.” Kasky started writing Facebook posts in the car after he and his brother, who has special needs, were picked up after the shooting by their dad. “I’m safe,” he wrote in the first, posted two hours after the shooting. “Thank you to all the second amendment warriors who protected me.” For the rest of the day, in between posts about missing students and recalling the experience of hiding in a classroom with his brother, Kasky’s frustration grew: “Can’t sleep. Thinking about so many things. So angry that I’m not scared or nervous anymore . . . I’m just angry,” he wrote. “I just want people to understand what happened and understand that doing nothing will lead to nothing. Who’d have thought that concept was so difficult to grasp?”

The social-media posts led to an invitation from CNN to write an op-ed, which led to televised interviews in the course of the day. “People are listening and people care,” Kasky wrote. “They’re reporting the right things.” That night, Thursday, after the candlelight vigil ended, Kasky invited a few friends over to his house to try to start a movement. “Working on a central space that isn’t just my personal page for all of us to come together and change this,” he posted. “Stay alert. #NeverAgain.” He had thought of the name, he later told me, “while sitting on the toilet in my Ghostbuster pajamas.” In early interviews Kasky had criticized the Republican Party, but he and his friends had decided since that the movement should be nonpartisan. Surely everyone—gun owner or pacifist, conservative or liberal—could agree that school massacres should be stopped. The group stayed up all night creating social-media accounts and trying to figure out what needed to be said, “because the important thing here wasn’t talking about gore,” Kasky said on Sunday. “It was talking about change and it was talking about remembrance.” It was then that they decided to petition for more thorough background checks. As Alfonso Calderon, a co-founder of Never Again, who was there that night, told me, “Nikolas Cruz, the shooter at my school, was reported to the police thirty-nine times.” He added, “We have to vote people out who have been paid for by the N.R.A. They’re allowing this to happen. They’re making it easier for people like Nick Cruz to acquire an AR-15.”

New Yorker writers respond to the Parkland school shooting.

They launched their new Facebook page just before midnight on February 15th. “Thank you to everybody who has been so supportive of our community and please remember to keep the memory of those beloved people we’ve lost fresh in your minds,” Kasky wrote.

While Kasky, Calderon, and their other friends huddled among snack wrappers in a gated-community war room, another student was developing a different plan. Jaclyn Corin is the seventeen-year-old junior-class president at Marjory Stoneman Douglas. She woke up the morning after the attack to the confirmation that her missing friend, Joaquin Oliver, was among the dead. She cried so hard that her parents had to hold her down. She also started posting on social media. “ PLEASE contact your local and state representatives, as we must have stricter gun laws IMMEDIATELY ,” she wrote on Instagram. It was after she went to grief counselling, and after the candlelight vigil that evening, that Corin first talked to the Democratic Florida congresswoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz. Conversations with state representatives followed, and preliminary arrangements were made to bus a hundred Douglas students and fifteen chaperones to Tallahassee to address the state legislature. Yesterday, I asked Corin if she had been politically active before the shooting. “Not even a little bit,” she said. “It’s so personal now. I would feel, like, horrible if I didn’t do anything about it, and my coping mechanism is to distract myself with work and helping people.” Corin was also prepared to advocate for gun-law reform, having worked on a fifty-page project about gun control for her A.P. composition-and-rhetoric class a couple of months before. “We have grown up with this problem,” she said, when I asked how the students had been so ready to argue the issue. “We knew this stuff. It’s not like a new, fresh horrible thing that’s happening, it’s been preëxisting even before we entered the world.”

By Friday, Corin had accepted an invitation from Kasky to join forces under Never Again. By Saturday, other students who had been independently talking to the media about gun control had joined, too—names that are now becoming familiar to the American public: David Hogg, the reporter for the school paper who appeared on national news broadcasts the morning after the shooting demanding action from elected officials; Sarah Chadwick, whose profanity-laced tweet criticizing Trump went viral soon after the shooting; and Emma (“We Call B.S.”) González, whose speech became the defining moment of a gun-control rally in Fort Lauderdale on Saturday. González, a senior, gave her first CNN interview on the night of the vigil. The invitation to speak at the rally had followed, and she wrote her speech the day she gave it. She had not anticipated how widely it would be shared. (Her last experience of activism, she told me, had been last year’s underwhelming March for Science.) She had simply written down the thoughts she had been sharing with her friends. “This is how I’m dealing with my grief,” she said. “The thing that caused me grief, the thing that had no right to cause me grief, the thing that had no right to happen in the first place, I have to do something actively to prevent it from happening to somebody else.” Kasky recruited Hogg and González for Never Again at the rally, where he also spoke.

“We said, ‘We are the three voices of this.’ We’re strong, but together we’re unstoppable,” Kasky said. “Because David has an amazing composure, he’s incredibly politically intelligent; I have a little bit of composure; and Emma, beautifully, has no composure, because she’s not trying to hide anything from anybody.” “All these kids are drama kids, and I’m a dramatic kid, so it really meshes well,” González added.

Following the Fort Lauderdale rally, after more media interviews, Kasky invited everyone over for a slumber party. “We were just saying, ‘O.K., look, we need to have preparation and beauty sleep,’ ” he said. There was very little sleep.

On Sunday, having announced the March for Our Lives on the morning talk shows, the activists stood in the shade of a picnic pavilion in North Community Park, less than half a mile from the flower-bedecked fences of their cordoned-off high school. They had issued an open invitation to the media to come find them in the park later that afternoon. Until then, they fielded stray interviews, caught up on loose ends, and occasionally broke into tears. González, whose shaved head had inspired online imitators in recent days, was seated at a picnic table with her mother, looking for a profile photo for her new Twitter account. Corin spoke to a pregnant local-news anchor. I was greeted by Calderon, who wore a tomato-red shirt and a blue tie to make it easy for reporters to identify him.

At the very least, the students had prolonged the news cycle. Corin would be leading her delegation to Tallahassee to meet with state representatives on Wednesday. Hogg and Kasky would be travelling to Washington, D.C., and New York for media appearances and to begin preparations for the March for Our Lives. Chadwick would continue her relentless online criticisms, turning her attention next to Marco Rubio and Tomi Lahren. (“I’m never going to stop talking about this,” she told me. “I’m not going to let people forget about the seventeen who lost their lives.”)

Other students would maintain operations at home, in Parkland. A local march was being considered, and then there was the President’s “listening session” with Douglas students that had been announced by the White House. The President, who has a house forty minutes away, and who had been in town over the weekend, had not yet said the words “Never Again,” and had timed the meeting in Parkland to coincide with the exodus of activist students to Tallahassee. Still, many of them would be staying in Parkland, as they had funerals to attend. Corin was urging her friends to “prioritize the comfort aspect first, prioritize the funerals, prioritize the victims’ families, prioritize all of that first, and then focus on the politics.”

The activists are wary about what form the backlash against them will take. They have learned statistics and the names of proposed laws, but they know it might not be enough.

“Our generation just isn’t allowed to screw up in any way, shape, or form,” Calderon told me. “Even before this happened, we already knew all the facts. We already knew everything.” But, he continued, their margin of error was so slim. I asked what he meant by screwing up. “At least in my short lifetime, I know that politicians have always screwed up,” he explained. “They have always said the wrong thing at the wrong time, and they’re still taken seriously, time and time again, instead of being disavowed or disqualified for even holding an office after saying ridiculous statements. Meanwhile, my generation is—for example, Emma González, she’s an inspiration to us and she’s working for us, but, if she were to say something that was non-factual, you know she would be highly scrutinized by literally everybody, including the President. I wouldn’t be surprised if he tweeted about Emma González saying that she is a domestic terrorist. And I can tell you, Emma, because I know her personally, she’s just a young girl like us, she’s no different than any of us, she’s just getting more media attention and that’s about it. She just wants to make a difference, too. And even though we’re not aiming for the highest glass ceiling out there, we have to make the first step.”

Calderon told me that he once ran into Nikolas Cruz at a Walmart with a friend who knew him. This was after Cruz had been expelled from Stoneman Douglas. The two friends stood and listened as Cruz bragged about a shotgun he had just bought. The moment has been weighing on Calderon—he wishes he had told someone. As I talked to him, I wished that he didn’t have to carry such regrets. Other people had expressed fear of Cruz to law enforcement in the past, and none of it had kept Cruz from his guns. The first step of the Never Again movement was believing in an idea that the rest of America had grown too cynical to imagine: that Marjory Stoneman Douglas High really could be the last school shooting in America.

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Michelle Nijhuis

By Renata Adler

By Charles Bethea

- Ethics & Leadership

- Fact-Checking

- Media Literacy

- The Craig Newmark Center

- Reporting & Editing

- Ethics & Trust

- Tech & Tools

- Business & Work

- Educators & Students

- Training Catalog

- Custom Teaching

- For ACES Members

- All Categories

- Broadcast & Visual Journalism

- Fact-Checking & Media Literacy

- In-newsroom

- Memphis, Tenn.

- Minneapolis, Minn.

- St. Petersburg, Fla.

- Washington, D.C.

- Poynter ACES Introductory Certificate in Editing

- Poynter ACES Intermediate Certificate in Editing

- Ethics & Trust Articles

- Get Ethics Advice

- Fact-Checking Articles

- International Fact-Checking Day

- Teen Fact-Checking Network

- International

- Media Literacy Training

- MediaWise Resources

- Ambassadors

- MediaWise in the News

Support responsible news and fact-based information today!

What it was like to visit the scene of the Parkland school shooting

A group of journalists from various platforms harnessed their individual strengths to compose the "jury view" pool note.

An extraordinary day in American journalism and jurisprudence began with a dice roll in the Fort Lauderdale, Florida, courthouse where the Parkland school shooter’s trial played out this summer.

The object for the participating journalists wasn’t a cash prize but an assignment unlike any other. They were vying for one of five spots on a media walkthrough of the site of the Feb. 14, 2018, massacre, which was preserved as a crime scene for more than four years in anticipation of this day.

The members of the media pool would tour the scene — after as the jury had — and record their impressions in a pool note to be shared with the rest of the media to use in their stories on the so-called “jury view.”

As one of the five journalists who participated, it’s easy for me to understand why prosecutors wanted the jury view and the gunman’s lawyers fought it at every turn. We were among the last people to bear witness to a crime scene that has cast a long and painful shadow over the Parkland community and beyond.

It still astounds me to think about what we observed and how we pulled it off. We came from different backgrounds and mediums, yet the key to our success came from the unique strengths we each brought to this solemn task.

Why we were there

Jury views of crime scenes are rare, partly because preserving a crime scene for extended periods is difficult. Then there’s the risk of arousing the jury’s passions, in the legal sense, moving them to make a decision based on emotions rather than the facts of the case.

Nevertheless, Broward County preserved the bloodstained halls and classrooms of Marjory Stoneman Douglas’ 1200 building for a jury to see in the gunman’s eventual trial.

Former MSD student Nikolas Cruz pleaded guilty in November 2021, paving the way for a penalty phase where a jury would decide if he deserved life in prison or death. Cruz’s lawyers tried to convince the judge overseeing the case that the jury deliberating his punishment didn’t need to see the crime scene. Cruz didn’t dispute what happened or how he carried out the shooting, they argued, and the jury had seen enough disturbing photos and videos to drive home the depravity of his actions.

Judge Elizabeth Scherer sided with the prosecution’s claim that seeing the crime scene would help the jury understand the evidence and Cruz’s role in context. And so, as the jurors gathered at the courthouse the morning of August 4 to board a bus to the high school, members of the press convened in a second-floor hallway and rolled a die for the chance to follow in their footsteps.

My network, Court TV, was granted a spot for national media because we contributed staff and gear to the pool camera rotation, so I sat out the dice roll. The Associated Press’ Terry Spencer and South Florida Sun-Sentinel reporter Rafael Olmedia were also guaranteed spots, leaving two spots for local television stations, which were won by WPLG’s Christina Vazquez and Joan Murray of WFOR.

It’s hard to overstate how coveted these spots were for the local journalists who lived and breathed this story for years. Most of them had a personal connection to the tragedy through a friend, a neighbor or a loved one. The media pool coordinator, veteran NBC 6 reporter Tony Pipitone, could have chosen a different way to choose pool members – or even claimed a spot for himself for having put in countless hours liaising between the court and the media. But a dice roll was the only fair way to do it, he said. After some tears and cheers, we had our pool.

Preparing ourselves

While the dice roll was underway, I was at my hotel a short cab ride away, anxiously awaiting a Doordash order I placed the night before for a clipboard and extra pens.

Earlier in the week, the media pool coordinator graciously shared with us floor plans he created of the hallways and classroom. Not only would they aid in note-taking, but we could use them as visuals in our reporting. The clipboard would help me as I zipped through the hallways jotting down observations, I told myself. I now see it as a creative attempt to feel in control while facing a situation for which I had no playbook.

Those of us in the jury view pool knew what to expect in theory. All of us had participated in at some point the daily end-of-day viewing of surveillance videos, crime scene photos and autopsy pictures that were shown to the jury but restricted from the public eye. We were responsible for generating pool notes for those viewings as well. We fell into an effective routine of taking it all in and claiming portions to write up as we hurried out of the courtroom back to the media room.

The night before the jury view, I reviewed my notes on the gunman’s path, the condition of each classroom and who was found where, but I still felt unprepared. We didn’t know how much time we would have to roam the hallways and classrooms. We only knew that we could not bring in any form of electronics or recording devices, just pen and paper to document the grim scene. Given the unknowns, even more concerning to me was how we would consolidate our thoughts into a cogent document as quickly as possible after the walkthrough. The producer in me was freaking out.

My fellow pool reporters had their own ways of preparing.

“One of the first things I did, when it was clear that I would be participating in the walk-through, was to check my motives,” Rafael Olmeda later told me. “I had to make sure I wasn’t doing this out of morbid curiosity but out of a desire to make sure that the interests of journalism and justice were served. The state is trying to put someone to death and this is the evidence they’re using. It’s the same thing I did to prepare myself for viewing graphic photos, except on a larger scale.”

The AP’s Terry Spencer had quite the backstory when I asked him what he did to prepare:

“I began preparing for the trial and school visit in January. I realized late last year that between covering MSD, COVID, the Surfside condo collapse and some earlier work issues, I had allowed myself to get woefully out of shape – not good for a 62-year-old about to be covering the most mentally grueling story of his career. So on Jan. 1, I began a diet and fitness regimen that I have stuck to. I try to work out every day and watch what I eat and have mostly succeeded, losing 50 pounds and getting back to my college weight. This has also given me something personally positive to focus on during those days the trial gets particularly depressing – which was every day during the prosecution case.

“Then two days before the school visit, I got a text from my wife as we sat in the courtroom that she had tested positive for COVID. I was negative, but to stay that way I moved into a hotel until the visit was over. My assigned backup at AP has two young daughters just starting school and did not need to walk into that building.

“Going into it, I just tried to focus on the job at hand – like I do every day. There is a line in The Godfather II, ‘This is the business we’ve chosen,’ that I frequently quote and remember when doing particularly trying assignments. I am in this position because 40 years ago I chose to pursue a journalism career, a decision that has given me a life I couldn’t have imagined as a kid. My dad was a truck driver who had crappy knees and hips – if he could suck it up and do his job, so can I.

“I also gave myself a pep talk that morning that went something like this: There is no one in the world better prepared or more able to do this assignment. My 35 years in the business have given me skills I didn’t have when I started. I have been covering this tragedy since 10 minutes after it happened and built up a lot of knowledge. I owe it to myself, my mentors, my AP colleagues, the millions of AP readers, the other members of the pool and those others in the media room who will depend on our report to put those skills and knowledge to use and pull my weight. I especially owe it to the victim’s parents, spouses and families that, to the best of my ability, I bear true witness to what I see. And what we will see will be nothing compared to what the teachers, students and first responders saw and experienced.”

Court deputies lead jurors into the Stoneman Douglas “1200 building” on Aug. 4 to view the crime scene where 17 people were murdered in 2018. (Amy Beth Bennett/South Florida Sun Sentinel via AP)

The scene inside

I arrived at the courthouse a few minutes after the dice roll to meet the team. From there, we piled into a van with a Broward sheriff’s deputy at the wheel and joined the morning interstate rush on the way to the high school.

We made small talk about our experiences reporting on the shooting. We read aloud notes on the gunman’s path and compared them with our floorplans with the fervor of a crash college study session.

The streets of Parkland were closed to traffic as we got closer to the school. Deputies posted in front of squad cars waved us through the empty streets all the way to the school. The fenced-in 1200 building loomed large as we pulled into the west parking lot and waited for the jurors to show up. They arrived a few minutes later in two white vans accompanied by squad cars and other vehicles carrying the judge and the lawyers.

Per the agreement with the court, we would enter the building after the jury finished its visit. As we waited in our vehicle, my suggestion to assign people to certain rooms was voted down in favor of another plan: We would each take in as much as we could, then divide up the sections on the 30-minute drive back to the courthouse.

After nearly an hour inside, the jurors piled back into their vans and it was our turn. We were dropped off in front of the barricaded building where members of the prosecution team greeted us alongside sheriff’s deputies.

We were offered the same crime scene accessories as the jury, medical booties, gloves and masks. As some of us suited up, we were informed that we would only have 10 minutes to explore each floor. The prosecutors had to get back to the trial, after all. The producer in me was screaming inside.

We negotiated a workaround with the deputies: 10 minutes on the first floor, five minutes on the second floor – where no one was killed – 15 minutes on the third. We got to work by essentially leapfrogging over each other. If one of us was in a classroom, we went to the next one and did our best not to linger.

“I would walk into a classroom and hear their voices, the teachers and students who recounted for the jury what they saw and heard on that tragic day,” Christina Vazquez told me.

“Knowing I would not have enough time to handwrite all that I was observing, I made a conscious effort to first scan the room, and then zero in on details, taking visual screenshots if you will, to write from memory into the media pool report after the visit.”

Spencer used the deadline to his advantage.

“It was, see something, write it down, move along. See something, write it down, move along. And if I let my emotions get the best of me, that would have hurt my ability to accurately report what I saw. There were a few times that was tested. Looking at the alcoves where Gina Montalto, Luke Hoyer, Martin Duque Chris Hixon and Joaquin Oliver died, knowing they saw Cruz fire the fatal shots at them – that was hard. Also, looking at the unfinished chess game Peter Wang had been playing when the third floor was told to evacuate. The spot where he was shot and the spot where Jaime Guttenberg fell. But I had to keep going. It also helped that we were doing this as a team and, for me, writing is often therapy.”

I wasn’t about to let my clipboard or floorplans go to waste. I scribbled partial quotes from signs and posters hanging on the walls and what can best be described as pictograms of the remnants of the Valentine’s Day massacre – dusty gift bags, cards, candy boxes resting atop bullet-riddled desks.

Documenting what we saw

By the time we left, the jury had returned to the courthouse and the trial had resumed. People were waiting on us.

As we typed up our written notes on the ride back, we took stock of which areas each of us had the most details for and claimed them. When we returned to the courthouse, we began pouring our vignettes into the Google doc under section headers for each floor. When done, we all reviewed the completed draft and added missing details to other sections.

Two of us took a final pass over the whole document to copy edit, cut redundancies and add more classroom headers. This was a pool note intended to describe what others could not see, not a robust narrative. By 2 p.m., 90 minutes after we left the building, we hit send on our 2,148-word pool note. Then we got back to work.

After the state rested its case in chief that afternoon, each of us appeared on different networks to describe what we saw. I struggled to find the words to answer the first questions I would have asked someone in my position: What was it like? What will you remember most?

Surreal is the best single word I can come up with for what it was like. What has stuck in my mind’s eye is the sensation of shattered glass crunching underfoot, wedging into the soles of my shoes because I refused the booties.

What I’ll remember most is the professionalism, support and grace under pressure shown by my fellow pool reporters, who I now consider friends as well as colleagues.

I consider my work on the jury view one of my greatest public services as a journalist, but I question the necessity of it for all involved – the jurors, the journalists and the school community that has had to live in the building’s shadow all this time. Was it worth the lasting memories and trauma? Judging from the jury’s verdict of a life sentence for the gunman, I’m not so sure.

Opinion | A conversation with White House Correspondents’ Association president Kelly O’Donnell

Advocating for her press corps colleagues has become a second full-time job for NBC News' senior White House correspondent.

Hunter Biden was indicted twice. A claim that he and others have escaped criminal charges is wrong.

Donald Trump faces dozens of criminal charges, but it’s inaccurate to claim that others including Hunter Biden were never charged with any crimes.

Opinion | The case for funding environmental journalism right now

Philanthropy has an important role to play in supporting reporters, but funding must be transparent and clear to maintain credibility

How Poynter transformed a hands-on workshop into an email course

Lessons learned from an experiment in building a new journalism project

Opinion | Journalists at Columbia are leading the coverage of their campus

The Columbia Daily Spectator has expertly documented tense protests over the Israel-Hamas war inside and outside the campus.

Start your day informed and inspired.

Get the Poynter newsletter that's right for you.

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- Home Planet

- 2024 election

- Supreme Court

- TikTok’s fate

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

- Gun Violence

- Criminal Justice

How the Parkland shooting changed America’s gun debate

It led to stronger gun laws. But it also may have caused a longer-term shift in America’s gun politics.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: How the Parkland shooting changed America’s gun debate

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/62723033/937394596.jpg.0.jpg)

2018 may have been the year when Americans finally started getting really, genuinely fed up with mass shootings.

In February, the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida, led to a new movement — the March for Our Lives — advocating for stricter gun laws. But its work did not stop with a march and some protests around the country; the movement, along with other work by other gun control advocacy groups, managed to get major legislative and electoral victories throughout the rest of the year.

The victories could endure beyond 2018. Now that Democrats, who ran in part on gun control, have seized control not just of the US House but several state legislatures and governors’ mansions, they will have a chance to implement or at least push for stronger firearm laws.

What happens next depends on how engaged American voters remain on this issue in the years to come. While the aftermath of the Parkland shooting suggests that there may have been a shift in this debate, the permanence of that change is far from guaranteed.

Gun control has long suffered from an intensity gap: Opponents of stricter gun laws are willing to vote based on that one issue, while supporters of gun control usually aren’t. It’s possible that the effects of 2018 will fade away, and the nation will return to its usual combination of initial sorrow and ultimate inaction after mass shootings. But if the trends of 2018 hold and the gap really does narrow, it will mean that the aftermath of the Parkland shooting won’t just help gun control advocates win over the next couple years — it could be a longer-term change for America.

A lot of gun control legislation passed

After mass shootings, it’s easy to look at the aftermath in Congress and despair: How is it that no matter what happens nothing gets done?

But the federal government is not the only one making new gun laws in America. The states are busy doing their own thing as well. And at the state level, a lot happened in 2018.

According to the Giffords Law Center (which supports stricter gun laws), 26 states and Washington, DC, enacted a total of 67 new gun control laws this year — more than triple the number of stricter gun laws enacted in 2017. The 2018 measures include a higher minimum age to buy guns, restrictions for domestic abusers, “red flag” laws that let law enforcement take away guns from people deemed a risk, and new urban gun violence reduction programs.

Some of these passed in states with Republican leaders. In Florida, the GOP-controlled legislature and Republican Gov. Rick Scott approved legislation that raised the minimum age to buy guns and added a waiting period for firearm purchases, among other changes. In Vermont, Republican Gov. Phil Scott signed gun control laws that included expanded background checks and a “red flag” law.

At the same time, there was a decrease in the number of new laws loosening access to guns. So Parkland didn’t just apparently inspire more support for gun control; it also led to less support for new, less-restrictive gun laws.

Maggie Astor and Karl Russell reported for the New York Times that NRA data “shows a similar overall trend this year, with gun control measures passed overtaking pro-gun measures for the first time in at least six years, though to a lesser extent than the Giffords data shows.”

There are limitations to the state-level measures. As long as some states maintain weak gun laws, people can simply cross state lines and obtain firearms in those gun-friendly states. This is a big problem in places with stronger gun laws, including Chicago , Massachusetts , and New York . That’s why stronger federal laws are needed.

Still, the gun control laws are significant measures that are now on the books and, based on the research , will reduce gun deaths, even if federal laws would have a stronger effect. And the big reason for that is the activism surrounding Parkland.

The intensity gap on guns may be closing

Of course, no one believes that what happened in 2018 is anywhere near enough to solve America’s gun violence problem. The bigger question is whether the Parkland movement had a significant effect on longer-term trends, which may over time lead to stronger gun laws.

When it comes to overall support for stronger gun laws, there was a significant spike shortly after Parkland: Based on Gallup’s surveys , support for stricter gun laws in March 2018 hit 67 percent, up from 55 percent in October 2016 and 60 percent in October 2017 (after the Las Vegas mass shooting ). But that support dropped by October this year to 61 percent — still higher than it was previously, but not that far off historical levels.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13635720/gallup_gun_laws.png)

So Parkland may not have led to a big, permanent boost in support for gun control — at least, not levels of support that are historically anomalous.

But if you look at the chart above, it should become pretty clear that there’s almost always been majority support for stricter gun laws. If anything, Gallup’s findings understate levels of support for gun control: When people are asked about specific policies , support climbs to the 70s and 80s.

The problem, then, has never been whether a majority of Americans support gun control. The problem, instead, is what’s known as the intensity gap: Essentially, even though more Americans support gun control laws, those on the side opposing stricter measures have long been more passionate about the issue — more likely to make guns the one issue they vote on, more likely to call their representatives in Congress, and so on.

As Republican strategist Grover Norquist said in 2000, “The question is intensity versus preference. You can always get a certain percentage to say they are in favor of some gun controls. But are they going to vote on their ‘control’ position?” Probably not, he suggested, “but for that 4-5 percent who care about guns, they will vote on this.”

This is where gun control advocates need to make some movement. And there are signs that there really was some movement following Parkland.

For one, a lot of people turned out to protest during the March for Our Lives earlier this year. It’s notoriously difficult to gauge the effects of these kinds of demonstrations, but it’s notable that the protests around the country numbered in the hundreds of thousands and became one of the biggest youth-led protests in decades .

Americans also seem increasingly fed up with mass shootings. According to a poll by NBC News and the Wall Street Journal, US adults’ second-most common response for the most important event of the year, after the improving economy, was mass shootings. There were similar findings in 2017, which also had a lot of high-profile mass shootings. These tragedies are clearly getting a lot of Americans’ attention.

The other important indicator here is that politicians who backed gun control won big this year in the midterm elections. This was partly a result of a blue wave, since Democrats are simply more likely to support stricter gun laws. (Although some Democrats, particularly in more conservative areas , are still running gun-friendly campaigns.)

But it’s notable that some Democrats ran strongly on guns and won. Alex Yablon and Daniel Nass at the Trace pointed to Jason Crow, who won a House seat in Colorado, as “the poster boy for proudly pro-gun control Democrats in twin late-season articles in the New York Times (‘Bearing F’s From the NRA, Some Democrats Are Campaigning Openly on Guns’) and Washington Post (‘Suburban Democrats Campaign on Gun-Control Policies as NRA Spending Plummets’) summing up the new political dynamic in swing state suburbs.”

Equally important, Republicans who supported gun control also won. That includes Vermont Gov. Scott, who won reelection in a state that, despite its liberal reputation, has long been resistant to gun laws. And it includes Florida Gov. Scott, who beat Democratic incumbent Bill Nelson in the US Senate race.

In the past, NRA criticism may have ended both these candidates. But even though the NRA downgraded both of them in its candidate scorecards, they won their respective elections.

These midterm elections will have longer-term impacts. As Reid Wilson reported for the Hill , newly elected Democrats are planning to push for stricter gun laws at the state and federal levels in the next year.

Beyond 2019, the midterm elections showed that candidates can support stronger gun laws — and even focus a campaign on the issue — and still win elections, even in states that have been resistant to stronger gun laws in the past. This is a shift: Since 1994 , when stricter gun laws were partly blamed for electoral losses, Democrats have often shied away from the issue.

It remains to be seen whether the shift on guns will hold in the coming years. But if it does, it would amount to a significant change in America’s politics — one that can be pinpointed back to Parkland.

Will you support Vox today?

We believe that everyone deserves to understand the world that they live in. That kind of knowledge helps create better citizens, neighbors, friends, parents, and stewards of this planet. Producing deeply researched, explanatory journalism takes resources. You can support this mission by making a financial gift to Vox today. Will you join us?

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In Politics

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Mass graves at two hospitals are the latest horrors from Gaza

The wild past 24 hours of Trump legal news, explained

Vox podcasts tackle the Israel-Hamas war

Donald Trump had a fantastic day in the Supreme Court today

Bird flu in milk is alarming — but not for the reason you think

What the backlash to student protests over Gaza is really about

Articles on Parkland school shooting

Displaying 1 - 20 of 42 articles.

3 ways to prevent school shootings, based on research

Beverly Kingston , University of Colorado Boulder and Sarah Goodrum , University of Colorado Boulder

Five years after Parkland, school shootings haven’t stopped, and kill more people

David Riedman , University of Central Florida ; James Densley , Metropolitan State University , and Jillian Peterson , Hamline University

5 ways to reduce school shootings

Paul Boxer , Rutgers University - Newark

American exceptionalism: the poison that cannot protect its children from violent death

Emma Shortis , RMIT University

Arming teachers – an effective security measure or a false sense of security?

Aimee Dinnín Huff , Oregon State University and Michelle Barnhart , Oregon State University

What we know about mass school shootings in the US – and the gunmen who carry them out

James Densley , Metropolitan State University and Jillian Peterson , Hamline University

Knoxville school shooting serves as stark reminder of a familiar – but preventable – threat

Why do mass shootings spawn conspiracy theories?

Michael Rocque , Bates College and Stephanie Kelley-Romano , Bates College

Schools should heed calls to do lockdown drills without traumatizing kids instead of abolishing them

Jaclyn Schildkraut , State University of New York Oswego

Do lockdown drills do any good?

More mental health care won’t stop the gun epidemic, new study suggests

Tom Wickizer , The Ohio State University ; Evan V. Goldstein , The Ohio State University , and Laura Prater , The Ohio State University

How Columbine became a blueprint for school shooters

Jillian Peterson , Hamline University and James Densley , Metropolitan State University

What Parkland’s experience tells us about the limits of a ‘security’ response to Christchurch

Amanda Tattersall , University of Sydney

3 ways activist kids these days resemble their predecessors

David S. Meyer , University of California, Irvine

School shooters usually show these signs of distress long before they open fire, our database shows

School shootings prompted protests, debates about best ways to keep students safe: 5 essential reads

Jamaal Abdul-Alim , The Conversation

Forget lanes – we all need to head together toward preventing firearm injury

Michael Hirsh , UMass Chan Medical School

Generation Z voters could make waves in 2018 midterm elections

Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg , Tufts University

School safety commission should not worry about violence in entertainment media

Christopher J. Ferguson , Stetson University

5 things to know about mass shootings in America

Frederic Lemieux , Georgetown University

Related Topics

- Gun control

- Gun violence

- K-12 education

- Mass shootings

- School safety

- School shootings

- School violence

- US gun control

- US gun violence

Top contributors

Professor of Criminal Justice, Metropolitan State University

Professor of Criminal Justice, Hamline University

Associate Professor, Marketing, Oregon State University

Associate Professor of Criminal Justice, State University of New York Oswego

Assistant Professor of Comparative Human Development, University of Chicago

Associate Professor of Criminal Justice, Penn State

Professor of Psychology, Bridgewater State University

Director, Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement in the Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life, Tufts University

Associate Dean for Students and William R. Jacques Constitutional Law Scholar and Professor of Law, University of Missouri-Kansas City

Associate Professor of Sociology, Bates College

Associate Professor of Communication Studies, Pace University

Visiting Professor of Public Health and Community Medicine, Tufts University

Professor of Psychology, Stetson University

Adjunct Senior Fellow, School of Global, Urban and Social Studies, RMIT University

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

‘A Parkland every five days’: project tells stories of the children lost to gun violence

A gun violence nonprofit attempts to tell the stories of American children and teens killed with a gun since Parkland

The grim total includes more than 80 young musicians, 30 dancers, 40 community volunteers, at least 80 infants and toddlers and 40 college-bound seniors.

In the 12 months since the Parkland school shooting, nearly 1,200 American children and teenagers have been killed with guns.

The everyday killings of young Americans add up to “ a Parkland every five days, ” according to a new project from The Trace, a nonprofit that covers gun violence, in collaboration with McClatchy newspapers and the Miami Herald.

Fourteen high school students and three educators were murdered last Valentine’s Day at Marjory Stoneman Douglas high school in Parkland, Florida, a massacre that inspired a national youth protest movement for gun control.

SinceParkland.org , a new project from McClatchy and The Trace, attempts to tell the stories of every child and teenager, ages 18 and younger, killed with a gun since that shooting.

The profiles are simple and devastating. Peyton Nicole Hurt , 15, loved painting watercolors. She was shot to death by her ex-boyfriend at a house party in Kentucky. Sandra Parks , 13, who had just written an essay about preventing gun violence, was killed by a stray bullet in her bedroom in Wisconsin. Mikey Pacheco , 17, a varsity football player, was accidentally shot to death by one of his friends as they sat around his kitchen table in Massachusetts.

In Wilmington, Delaware, which has America’s highest rate of teen gun violence, two half-brothers were killed just blocks apart: Raquis Q Deburnure , 16, in May, Rashaad Izil Wisher , 18, in July.

In Chicago, James Garrett , 18, was shot to death at a vigil for a friend. He had been preparing to become a teacher. Two days later, 675 people came to a memorial service in his honor.

The project was designed as a response to young activists, including many Parkland students, who have criticized media outlets for not devoting enough attention to the toll of daily gun violence.

“Young people at the center of the movement really chided the press for only covering mass shootings and not going beyond that,” Akoto Ofori-Atta, managing editor at The Trace, and the project director of Since Parkland , said in an interview with MSNBC’s Stephanie Ruhle.

To write more than a thousand stories over the course of a year, The Trace recruited more than 200 teenage journalists from across the country.

“There’s no generation that has had to contend with this issue the way that young people today have had to contend with it,” Ofori-Atta said. “We felt it was their story to tell, and their perspective was needed.”

It was intense, emotional work. Some of the writers were the same age as the kids they were memorializing.

Trying to capture the life of King Thomas III , 15, who was killed during a home invasion in Texas, student journalist Kira Davis, also 15 at the time, listened to the music Thomas had posted on Soundcloud.

Joe Meyerson, a high school senior from Los Angeles, noted in a profile of the project that he was surprised and frustrated by how often news accounts of the shootings contained basic errors.

“These are young men, young women, and kids who have been gunned down,” Meyerson said. “How do you get their name wrong? How do you get where they lived wrong? How do you get their school wrong?”

Each obituary focuses on the lives and personalities of the kids lost, more than the circumstances of their deaths.

“These kids who died every day since Parkland, they were loved. They had full, complex lives,” Ofori-Atta said.

This count of 1,200 American kids killed with guns in the past year does not include gun suicides. An estimated 900 to 1,000 more children and teenagers killed themselves with guns in the past year, which would bring the total number of American youth gun deaths to more than 2,000 in a single year.

The majority of youth gun killings documented in the Since Parkland project are homicides. Only 154 of those killings were accidental, according to Caitlin Ostroff, a data reporter at McClatchy and the Miami Herald. The project relied on gun death data compiled by the Gun Violence Archive , a nonprofit that tracks shootings and gun deaths in real time using media reports. Journalists on the project also requested reports from hundreds of police agencies to verify the details of the incidents.

About 10% of the young people killed with guns were lost to domestic homicides. They were killed by their own relatives, their significant others, or their parents’ significant others. Many of the 133 domestic incidents were murder-suicides, including dozens of cases where mothers or fathers killed their children, and then killed themselves.

In one case, powerfully profiled in the Miami Herald, three young siblings were shot to death by their father, who then killed himself. Odin Tyler Painter , eight, was a Boy Scout. Cadence Nicole Painter , six, loved dancing. Drake Alexander Painter , four, preferred nature to screens, and liked to pick flowers for his mother, who was injured in the shooting, but survived.

- Parkland, Florida school shooting

- US gun control

- US school shootings

Most viewed

25 Years After Columbine, America Spends Billions to Prevent Shootings That Keep Happening

- Share article

The chain of events has become so predictable as to be mind-numbing.

A school shooting with multiple fatalities draws national attention to a community shattered by tragedy. Parents across the United States fear for the safety of their own children. They demand policy solutions that don’t materialize. And school leaders feel compelled to fill in the gaps, or at least show that they want to.

That cycle has played out dozens of times in the 25 years since the Columbine massacre, leaving a virtually incalculable financial toll in its wake.

Each day over the past quarter century, America’s schools have opened their doors to hundreds of thousands of students who have directly experienced gun violence at school, and millions more who fear they will, too.

With the goal of keeping them and the adults who serve them safe, billions in tax dollars fund personnel and technology tools designed to enhance security and ward off intruders. Billions more pay for academic and emotional support services that help students burdened by trauma and anxiety.

A massive and inconsistently regulated industry has sprung up to blanket schools with offers of high-tech tools and to advise them on practices that prepare adults and children for the unthinkable.

“Anytime anyone says ‘There is something you could do to prevent a school shooting, and if you don’t buy it, you’re responsible for what happens next,’ it’s very hard for them at that moment to say no,” said Samantha Viano, an assistant professor of education leadership at George Mason University who studies school security and technology .

An array of personnel and tools implemented with the goal of preventing future school shootings is one of the most visible outcomes of the era following the 1999 shooting at Columbine High School. School resource officers and security guards have been added to district budgets and payrolls, and schools have installed weapons detection systems, facial recognition software, bulletproof entrance vestibules, and metal detectors.

Yet school shootings have continued and remained a persistent threat for so long that some who survived high-profile school shootings now have school-aged children of their own.

The number of school shootings in the U.S. has increased significantly in recent years , from fewer than 20 per year in the early 2000s to well over 100 in each of the last four years, according to research analyzing federal data . The death toll of mass shootings has also risen over the comparable period.

These events are statistically rare, but many times more common than in other countries . This year alone, 11 school shootings that resulted in injuries or deaths have already taken place, according to Education Week’s tracker .

Sarah Woulfin was a 20-year-old college junior in 1999. She’s lived with the school shooting threat top of mind ever since.

Now she’s the parent of a 4th grader and a researcher at the University of Texas-Austin who characterizes the process of “hardening” schools as a form of “fortification” that exacerbates racial disparities and fails to meaningfully reduce the threat of violence.

“I don’t think we know enough about how much money is really being spent,” Woulfin said. “I don’t think people have done enough alternative modeling to figure out what might be the benefits of spending much less or much more, or the same as what we spend now but in slightly different ways.”

How Columbine kicked off a flurry of investment

On April 20, 1999, two seniors at Columbine High in Littleton, Colo., fatally shot 12 students and a teacher before killing themselves. The gunmen had planted propane tanks and pipe bombs, but those failed to explode.

It was far from the first such incident on American school grounds. As early as 1973, a school safety panel in New York City was making recommendations for new policies and personnel in response to violent incidents, The New York Times reported .

But Columbine gained widespread recognition with the help of emerging 24-hour cable news programs. The events of that day spurred calls for dramatic action that still reverberate.

The impact of the subsequent hundreds of violent incidents involving guns on school grounds can hardly be measured using monetary metrics alone.

But even an incomplete tally of the expenses that stem from school shootings offers a glimpse into the central role they’ve played in American society during the 21st century.

A 2011 study of Texas school finance data found that schools there overall spent three times more per pupil on school security than they did on social work; their budgets for security expenses amounted to nearly one-third of what they spent on instruction. Urban schools spent roughly the same amount on school security as they did on health services for students.

A 2021 study examining districts that experienced shootings between 1999 and 2018 found that the violence drove up per-pupil spending by $248 in the shootings’ aftermath. The researchers also found that those districts often lost higher-income students to other districts in the years after shootings.

The biggest and most obvious expense schools have incurred in the post-Columbine era is for security guards and school resource officers. America invests $2.5 billion annually in SROs and another $12 billion in security guards . The latter sum is larger than for any school position other than teachers.

Several prominent studies document the harms that the presence of school resource officers can cause in schools— particularly for students of color , who are disproportionate targets for discipline and surveillance. Some research shows the presence school resource officers contributes to a reduction in certain kinds of violent incidents , but not necessarily for school shootings . The overall body of research on SROs has been virtually non-existent until recent years, leaving many questions unanswered.

But the lack of a strong evidence base hasn’t stopped the profession from proliferating. Some school districts eliminated their budgets for school resource officers following protests for racial justice that swept the nation in 2020—but some of those districts have since brought those positions back .

School districts often hire additional security staff in the wake of a violent incident on their campuses or even elsewhere. Other school leaders see that happening and feel like they shouldn’t be left out.

“If they see one school has 10 security guards, then they want 10,” Viano said.

State mandates for increased security staffing often come without dedicated funding. In Texas, for instance, school districts have recently scrambled to meet a new requirement for armed guards at every campus . But they’ve had to dip into local funds to pay salaries and benefits for those new employees without new help from the state.

“We’re adding regulations, we’re adding requirements, but we’re not actually adding the funding that goes along with it,” Woulfin said.

Some spending decisions in response to school shootings stem from fear of litigation that can cost tens of millions of dollars to resolve —not to mention reputational damage that can deter families from keeping their children in the district or moving to the area.

“School districts see the potential cost of a shooting on any campus to be immeasurably large,” Viano said.

Still, some experts believe policymakers don’t adequately assess the long-term costs of their short-term efforts to curb violent shootings on school grounds. What seems like a prudent investment in the short term might become more expensive later on.

For instance, a push in recent years to permit school staff members to carry guns has spooked some insurers from offering coverage of any kind, said David Riedman, founder of the K-12 School Shooting Database , which catalogs hundreds of incidents from 1966 to the present.

“Who’s paying the cost of a wrongful shooting? Who’s paying the cost if there’s some sort of negligence or failure to act?” Riedman said. “People aren’t thinking about that.”

The long-term costs to students are steep

The reaction to the Columbine massacre set the stage for fatal school shooting events to come, in places like Newtown, Conn., and Parkland, Fla.

“It really draws attention to a particular type of gun violence incident that is large-scale, massively traumatic, and leads one to want to do things to prevent it from ever happening again,” said Maya Rossin-Slater, an economist and associate professor of health policy at Stanford University who has extensively studied the long-term effects of school shootings on children.

Most incidents involving gun violence on school grounds are different from the massacres that draw the most attention—a student brandishes a gun during a fight, a school resource officer accidentally fires a gun, a student or staff member dies by suicide.

“Those incidents are much more common, disproportionately affect less advantaged schools, and nevertheless have really lasting impacts,” Rossin-Slater said.

Her research found that students who had experienced gun violence on campus were likely to earn $115,500 less over their lifetimes than students who hadn’t. Students who witnessed guns on school grounds are also nearly 10 percent less likely than students who didn’t witness school violence to attend college and 15 percent less likely to have a bachelor’s degree by age 26, she found.

In a separate paper , she estimated that students witnessing gun violence at school were 21 percent more likely than students who didn’t to use antidepressants within the next two years.

“Even those who escape these events without any visible physical harm carry scars that could impair their lives for many years to come,” Rossin-Slater wrote.

These long-term challenges demand a different array of potential responses, from increased mental health counseling to expanded programming that encourages collaboration and camaraderie among students and staff, Rossin-Slater said.

Many researchers agree that a quarter-century of evidence points to the need for a new strategy to deal with the threat of gun violence—especially in the absence of broader federal policies that curb the widespread accessibility of guns.

Riedman thinks state lawmakers and school districts should have a more structured system for evaluating whether a proposed solution will make a meaningful difference.

He often peruses the incidents in his database to assess whether a particular proposal would have affected the outcome of those events. In many cases, it wouldn’t.

“That’s a roadmap to evaluate the things based on evidence rather than looking at a vendor’s video about how, in an imagined scenario, their product might work,” Riedman said.

Viano thinks the U.S. Department of Justice should tighten oversight of allowable uses of grant funds it provides to school districts for security tools and safety measures. In general, when districts have money available to them, they’re going to spend it, she said.

That money might be spent more productively on addressing core issues affecting students that may be a byproduct of a culture of violence on school campuses, Rossin-Slater said.

Students who experience shootings at school are more likely to be chronically absent, and teacher retention tends to drop in places where shootings occur. Investing in ways to address those problems is also an investment in safety, she said.

It’s impossible to separate the challenges schools face because of school shootings from the broader challenges they routinely encounter and need resources to address, Rossin-Slater said.

“The schools that already have less financing, the people who have less access to mental health care, the areas where those mental health services are less available, those are the places that suffer,” she said.

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

The Columbine-Killers Fan Club

A quarter century on, the school shooters’ mythology has propagated a sprawling subculture that idolizes murder and mayhem.

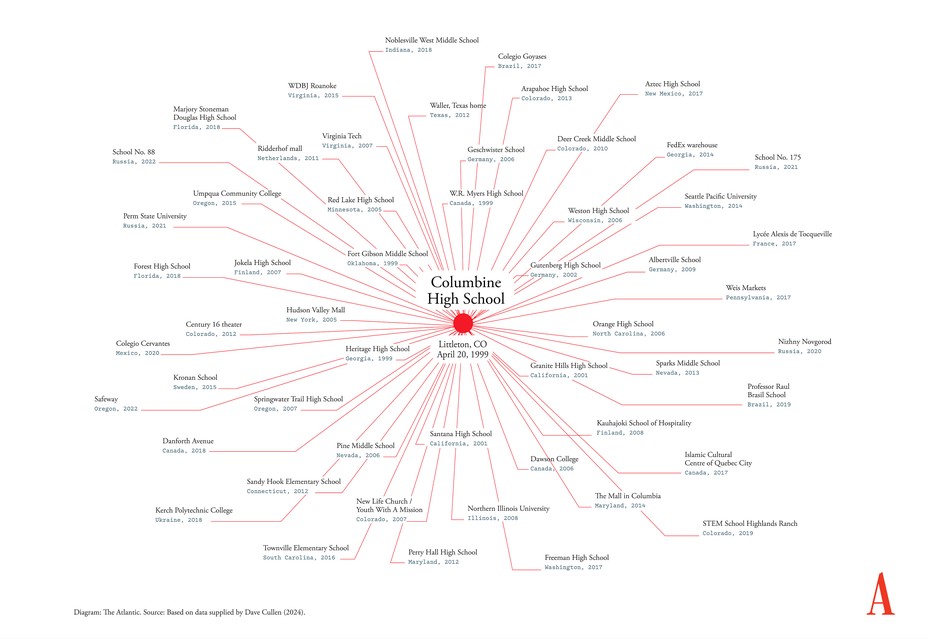

M ass shootings didn’t start at Columbine High, but the mass-shooter era did. Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold’s audacious plan and misread motives multiplied the stakes and inspired wave after wave of emulation. How could we know we were witnessing an origin story?

The legend of Columbine is fiction. There are two versions of the attack: what actually happened on April 20, 1999, and the story we all accepted back then. The mythical version explained it all so cleanly. A pair of outcast loners dubbed the “Trench Coat Mafia” targeted the jocks to avenge years of bullying. Dwayne Fuselier, the supervisory special agent who led the FBI’s Columbine investigation, is fond of quoting H. L. Mencken in response to the mythmaking: “There is always a well-known solution to every human problem—neat, plausible, and wrong.”

The legend hinges on bullying, but the killers never mentioned it in the huge trove of journals, online posts, and videos they left to explain themselves. The myth was so insidious because it cast the ruthless killers as heroes of misfits everywhere. Fuselier warned how appealing that myth would sound to anyone who felt ostracized. Within a few years, the fledgling fandom would find one another on social media, where they have operated ever since.