MINI REVIEW article

Childhood immunization and covid-19: an early narrative review.

- MPH Program, School of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, Fairleigh Dickinson University, Madison, NJ, United States

The COVID-19 pandemic has evolved into arguably the largest global public health crisis in recent history—especially in the absence of a safe and effective vaccine or an effective anti-viral treatment. As reported, the virus seems to less commonly infect children and causing less severe symptoms among infected children. This narrative review provides an inclusive view of scientific hypotheses, logical derivation, and early analyses that substantiate or refute such conjectures. At the completion of a relatively less restrictive search of this evolving topic, 13 articles—all published in 2020, were included in this early narrative review. Directional themes arising from the identified literature imply the potential relationship between childhood vaccination and COVID-19—either based on the potential genomic and immunological protective effects of heterologous immunity, or based on observational associations of cross-immunity among vaccines and other prior endemic diseases. Our review suggests that immune response to the SARS-CoV-2 virus in children is different than in adults, resulting in differences in the levels of severity of symptoms and outcomes of the disease in different age groups. Further clinical investigations are warranted of at least three childhood vaccines: BCG, MMR, and HEP-A for their potential protective role against the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Introduction

The novel Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has infected close to 9.5 million people and has claimed nearly 762,000 lives globally, as of August 16, 2020 ( 1 ). This pandemic has evolved into arguably the largest global public health crisis in recent history—especially in the absence of a safe and effective vaccine or an effective anti-viral treatment. This virus has demonstrated a high attack rate, a broad gamut of identifiable symptoms, and viability among a potentially massive number of infected silent carriers.

Unlike many infectious diseases, such as endemic malaria and common flu where children are known to have the highest mortality rates and to drive transmission in households and communities—it appears as it could be that SARS-CoV-2 just does not translate into severe disease as frequently in children, specifically for young children, below 10 years of age. Moreover, infected children suffer milder symptoms of COVID-19, with much lower case-fatality rates (CFR), and recover quickly from the infection ( 2 – 7 ). In an initial assessment from Wuhan, China, among 50 children identified with COVID-19, the severity varied between asymptomatic and mild in 96% of the patients ( 8 ). While diagnostic findings were similar to those of adults, fewer children developed severe pneumonia. Neonates, on the other hand, have developed symptomatic and more severe COVID-19 ( 2 , 7 ).

Data obtained from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention as of February 17, Spanish Ministry of Health as of March 24, Korea's Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as of March 24, and the Italian National Institute of Health as of March 17—suggests that the CFR for COVID-19 for children are disproportionately lower compared to any other age group ( 9 ). The CFR was 0% for all four countries for the age group “0–9 years.” Singh et al., suggest that milder symptomatology implies potential immunologic protective factors in children and the direction for a design of interventions for all age groups ( 2 ). While it is likely that early publication of reports from countries with generally more equipped healthcare systems may not be fully indicative of the long-term overall potential impact in less developed nations—current observations do not suggest such trends yet.

Propositions for such lower observed rate of fatality and symptomatic illness have included the potential protective effect of global active viral immunization of children from birth till 6 years of age ( 10 ). It is suggested that childhood vaccines for mumps, rubella, poliomyelitis, Hepatitis B, and varicella may impart transient immunity against SARS-CoV-2 that protects their lung cells from contracting COVID-19 ( 10 ). Subsequently, aging, immunosuppression, and co-morbid states reduce the adaptability of the immune system ( 5 ).

The rates of heterologous immunity have been studied in some of the common childhood vaccinations including measles and Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccines. African American girls who received the measles vaccine demonstrated 47% reduced mortality from other diseases. Similarly, the BCG vaccine has demonstrated a 25% reduction in mortality to other diseases ( 11 ). Previous research has supported that live vaccines have increased resistance to other vaccine unrelated diseases. Thus, they have specific effects by preventing the targeted disease but also non-specific effects on non-targeted infections as well. It is theorized that vaccines boost immune responses, offering additional resistance to viruses other than the ones they are intended to prevent ( 12 ). It should also be noted that research only suggests there is a correlation between vaccines and non-specific responses, not causation.

Such hypothesis of cross-immunogenicity of existing childhood vaccines with the novel coronavirus, if proven true, could have far reaching implications for public health immunization policies across the globe. However, no broad assessment of this topic has thus far been undertaken to the best of our knowledge at the time of this writing.

In this narrative review, we provide an inclusive view of scientific hypotheses, logical derivation, and early analyses that substantiate or refute such conjectures. The goal of this study is not to establish a comprehensive, systematic understanding of the link between childhood vaccination and COVID-19 outcomes. Instead we attempt to offer a robust starting point to facilitate further development of relevant hypotheses and designing of studies to test this promising public health opportunity.

Given the early stage in the evolving literature on this topic, our attempt at a systematic search of health sciences databases such as PubMed using keywords and search strategies such as: “coronavirus OR COVID-19 OR nCoV OR SARS-CoV-2) AND (child OR children OR childhood OR pediatric OR infant OR babies OR baby OR neonates) AND (immunization OR vaccination OR vaccine)” limited to English language articles published in between June 2019 and April 2020 did not yield sufficiently relevant publications. While there may have been articles that were published in other languages during the review period, those were not included unless an English translation was available. Given the importance of this topic, we believe that such non-English articles, if any, will be included in future assessments as there is broader presence of the data in global literature.

As such, given the broader base of sources accessed by its search function, we performed a plain language search using the same keywords listed above on Google Scholar, which includes journal and conference papers, theses and dissertations, academic books, pre-prints, abstracts, technical reports, and other scholarly literature from all broad areas of research ( 13 ). All types of study and countries of origin were eligible for inclusion. In addition, any relevant articles that were identified during and outside the formal search process were also included if their content were relevant to our study. Four reviewers extracted relevant data into a cloud-based spreadsheet. We recorded the country of origin, study design, type of data, results, and conclusions. As this was intended to be a rapid review, each article was reviewed by one reviewer.

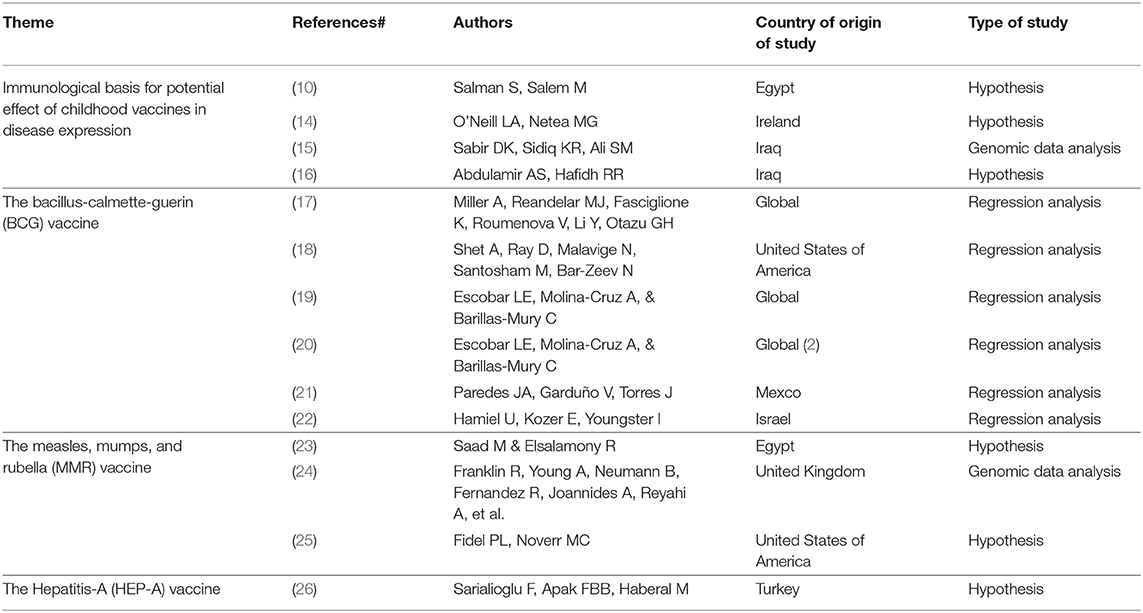

At the completion of the quick search and identification process, 14 out of 30 identified articles were included in this early narrative review ( Table 1 ). Included papers were all published in 2020 following the early release of data on COVID-19, presenting hypotheses about the potential relationship between childhood vaccination and COVID-19—either based on the protective effects of heterologous immunity, or based on observational associations of cross-immunity among vaccines and other prior endemic diseases.

Table 1 . Summary of studies included in the narrative review.

The Immunological Basis for Potential Effect of Childhood Vaccines in Disease Expression

In many countries, children are routinely vaccinated against a number of bacterial and viral diseases. Vaccines may have non-specific physiologic effects when they alter the immune response to unrelated organisms, called heterologous immunity. The non-specific effects of vaccines are usually more pronounced in girls and appear to be maximal in the first 6 months of life ( 11 )—when passed maternal immunity is further supplemented by newly introduced vaccines, starting at 2 months. There are several theories as to why heterologous immunity may occur.

Salman and Salem suggest that cross-immunogenicity of childhood vaccines for multiple viruses could potentially be a reason for the relatively milder infection and severity of COVID-19 among children ( 10 ). Most routine viral vaccines are either inactivated or killed viruses that stimulate T Helper 1 cells (CD4+) to secrete many different types of cytokines as interferon gamma, interleukin-2 (IL-2), and IL-12, improving the cytotoxicity of natural killer cells to recognize and destroy cells infected with new cross-reactive viruses. For example, warts that are caused by human papilloma virus (HPV) could be ameliorated using intralesional MMR vaccine ( 10 ).

Furthermore, neutralizing antibodies produced against the foregoing vaccine-preventable microbes might cross-react with the antigenic epitopes of the spike (S) and nucleocapsid (N) proteins and prevent COVID-19 in children ( 15 ). An investigation of this hypothesis, using the BLAST search tool, showed no significant sequence similarity between these proteins and those in the childhood vaccine-preventable microbes, inferring that memory T-cells, rather than vaccine neutralizing antibodies, may be involved in the protection of children against COVID-19 owing to them having a larger number of naive T-cells that can be programmed to protect them against the disease ( 27 ).

Potentially, the low immunity in children that doesn't exaggerate the immune response against the virus as in the case of adults, could explain the lesser severity of SARS-CoV-2 in this age group. Children have less adults-like memory cells specific to other circulating coronaviruses and therefore, are less capable to mount a devastating and vigorous cell-mediated attack on alveoli and interstitial tissue of the lung upon new infection ( 16 ).

The Bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) Vaccine

The Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine is given in infancy for prevention of severe forms of tuberculosis and has the widest use, and a strongest safety profile among all childhood vaccines ( 28 ). Epidemiological and randomized trial evidence suggest a protective effect of BCG on infant mortality via non-specific heterologous protection against other infections possibly through innate immune epigenetic mechanisms ( 29 ).

O'Neil and Netea suggest that induction of trained immunity by BCG vaccine could provide protection against COVID-19, and the use of oral polio vaccine and new recombinant BCG-based vaccine VPM1002 may be some of the approaches to induce resistance to SARS-CoV-2 ( 14 ). The authors hypothesize that induction of trained immunity is at least partly the mechanism through which BCG vaccination induces its beneficial effects and might protect against SARS-CoV-2.

A retrospective study compared countries that do not have BCG vaccination policies (Italy, USA, Lebanon, the Netherlands, and Belgium), to countries that have such policies ( 17 ). The results showed that while middle-high and high-income countries with current universal BCG policies had 0.78 COVID-19 deaths per million, those without such policies had 16.39 COVID-19 deaths per million people—and the difference was statistically significant. Further analysis of 28 countries found a positive significant correlation ( p = 0.02) between the year of the universal vaccination policy and mortality rate—suggesting that if the policy to vaccinate was adopted at an earlier year, more of the elderly population in these countries would have been vaccinated, thus potentially offering them more protection. In countries, such as Italy, where BCG vaccine was never given, the mortality rate was significantly higher compared to Japan where BCG vaccination has been implemented since 1947. In countries, such as Iran, with BCG vaccination starting in 1984, mortality was higher since today's elderly population did not receive the vaccination.

In order to mitigate the bias centered around the differential epidemic time curves experienced by different countries, Shet et al., calculated days from the 100th COVID-19-positive case to align countries on a more comparable time curve ( 18 ). A log-linear regression model was built with crude COVID-19-attributable mortality data per 1 million population for each country as outcome, BCG vaccine inclusion in the national immunization schedule as exposure, and adjusted for the effects of: country-specific GDP per capita, the percentage of population 65 years and above, and the relative position of each country on the epidemic timeline. COVID-19-attributable mortality among BCG-using countries was 5.8 times lower ( P = 0.006) than in non-BCG-using countries. Sensitivity analysis run excluding China as the majority case contributor from the model resulted in no appreciable change in the protective effect of BCG.

Escobar et al., in a study that carefully controlled for confounding variables found that there was an inverse correlation between countries/locations with a stronger BCG vaccination policy and COVID-19 related mortality ( 19 ). COVID-19 mortality rates in New York, Illinois, Alabama and Florida—states without BCG-vaccination policies in the US, were significantly higher than locations with BCG-vaccine policies, namely Pernambuco, Rio de Janeiro, and Sao Paulo in Brazil, or Mexico State and Mexico City in Mexico.

In a more recent study, the same authors demonstrate a strong correlation between the BCG index and COVID-19 mortality in different socially similar European countries ( r 2 = 0.88; P = 8 × 10–7), indicating that every 10% increase in the BCG index was associated with a 10.4% reduction in COVID-19 mortality ( 20 ).

However, evidence suggesting a protective effect of the BCG vaccine was not found to be universally consistent and only demonstrated association not causality. There indeed are a myriad of factors apart from the effect of a childhood vaccine that could impact the findings of association, and such caution in interpretation would be recommended—especially this early in our understanding of the COVID-19 disease.

Paredes et al., showed that when confounders such as under-reporting, SARS-CoV-2 capability testing and differing lockdown measures were considered, the differential impact of BCG vaccination on COVID-19 related mortality rate was not significant ( 21 ). Among high-income countries, the mean number of deaths per 1 million population for countries with no universal BCG vaccination (223.2 ± 166.1) was not statistically significant from countries with current or previous BCG vaccination programs (55 ± 82.5; P = 0.85). No statistically significant difference was noted in mean number of deaths at the 1,000th case in these three groups either.

Hamiel et al., compared infection rates and proportions with severe COVID-19 disease in 2 cohorts: individuals born during 3 years before and 3 years after cessation of the universal BCG vaccine program in Israel ( 22 ). There was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of positive reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction tests for SARS-CoV-2 in the BCG vaccinated group compared to the unvaccinated group (11.7 vs. 10.4%, p = 0.09). There also was no statistically significant difference in positivity rates per 100,000 (121 vs. 100, p = 0.15).

The Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR) Vaccine

Saad at al., suggested two potential mechanisms for higher COVID-19 cases per population ratio and higher death rate in Italy (no MMR vaccine) compared to China: ( 1 ) by generating bystander immunity the measles vaccine increases ability of immune system to combat non-measles pathogens, including coronaviruses, and ( 2 ) due to shared structural similarities between measles and coronavirus the cross-reactivity and immunity between the measles vaccine and coronavirus leads to partial protection against COVID-19 ( 23 ).

Franklin et al., identified that the macro domains of SARS-CoV-2 and rubella virus and the MMR vaccine, share 29% amino acid sequence identity ( 24 ). This finding suggests the viruses possess the same protein fold. Patients with high illness severity had high levels of rubella IgG (161.9 + 147.6 IU/ml) compared to patients with a moderate severity of disease (74.5 + 57.7 IU/ml). The authors suggest the MMR vaccine could result in potentially reduced severe outcomes with COVID-19.

In their commentary, Fidel and Noverr support the use of live attenuated MMR vaccine as a preventive measure against the pathological inflammation and sepsis associated with COVID-19 infection ( 25 ). While they emphasize the strictly preventive nature of the suggestion, the basis of such suggestion is the induction of non-specific effects by live attenuated vaccines that represent “trained innate immunity” delivered by leukocyte precursors in the bone marrow more effectively functioning against broader infectious attacks. On the basis of data from prior BCG trials in infants, the vaccine-induced trained innate cells are expected to remain in the circulation for roughly 1 year, which should see people through the most severe waves of COVID-19 infection.

The Hepatitis-A (HEP-A) Vaccine

Sarialioglu et al., reported on the differences in the rate in which COVID-19 had affected some countries such as China, US, Italy, Spain, France, England, the Netherlands, and Belgium more severely than some others such as India, Pakistan, countries of the African continent, and South America which had lower rates of infection and mortality at the time of their study ( 26 ). The authors hypothesize that routine vaccination for hepatitis A virus (HAV) causing high seroprevalence among populations in countries in the low COVID-19 prevalence group, while it is rather low in the industrialized countries.

In addition, the authors point to the COVID-19 experience in the Diamond Princess cruise ship, which after arriving in Yokohama, Japan on February 3rd 2020, was placed under quarantine for the disease based on another passenger who had disembarked in Hong Kong a couple of days earlier and has tested positive for the virus ( 30 ). A report ( 31 ) showed that by February 20th over 18% of the 700 infected among the 3,700 people showed no symptoms. The low frequency of symptomatic disease on the ship, may be explained by stimulated immunity before passengers started the cruise trip when HEP-A vaccine was recommended for international travel in areas with high HAV endemicity. However, no publicly available information on the HEP-A vaccination status of the passengers were found.

While there does not seem to be any objective evidence to support this yet, the authors further contemplate that the severity of COVID-19 and vulnerability of very young children, particularly infants <1 year of age, may be attributed to the eventual decrease of maternal anti-HAV antibodies toward age 1 year—as HEP-A vaccine is not administered until after 1 year of age.

The authors conclude that immune response caused by the hepatitis A vaccine may be protective against COVID-19 infection by a possible adaptive immune cross-reaction. Patients with asymptomatic COVID-19 disease could indirectly indicate those with protection from HAV seropositivity. The HEP-A vaccine may help to keep the COVID-19 infection at mucosal colonization levels and prevent lower respiratory tract involvement and fatality ( 26 ).

At the time of this writing, the pandemic of COVID-19 continues to be a global public health emergency, claiming the lives of hundreds, and infecting millions all over the world. While the trend thus far shows a relatively less severe morbidity and mortality profile of the disease among children, the reason behind such a trend is not yet well-understood. While several theories for such welcome relief have been proposed, we present available insights and hypotheses on the potential link between childhood vaccination and the less severe expression of COVID-19 in this early narrative review.

Although it is relatively early in the process of the scientific community's gaining full understanding of the SARS-CoV-2 virus and characterization of its infection, known virus-prevention strategies from past pandemics that could lead to potential attenuation of the currently ongoing disaster, are of high interest. Public health emergencies, by their nature, often do not have the luxury of time needed for well-researched remedies, and that is why hypotheses and theories are relevant—even if with the possibility of bridging current patients and populations to the time when treatment and vaccination for COVID-19 are available.

Our narrative review finds that there indeed is a potential scientifically-based possibility of heterologous immunity from common childhood vaccines to be imparting a protective effect on COVID-19 infections in children. While not unequivocal, population-level differences found in several studies in the rate of infection and severity of expression of COVID-19 between countries with and without certain common childhood vaccination policies suggest the need for deeper and more well-structured investigation, in the minimum. Although prevalence of some target diseases and organisms may have been eradicated in certain parts of the world, the reinstitution of relatively inexpensive vaccines for those diseases into the currently recommended childhood vaccination regimen may merit careful re-evaluation. Our review found suggestions from the medical community of such promise in at least three of the most common vaccines given to children—BCG, MMR, and HEP-A.

However, it is indeed not recommended that such practices be instituted without establishing a reasonable scientific evidence to validate some of these hypotheses—especially when children are involved. Pragmatic randomized controlled trials designed to time- and cost-efficiently test feasible primary endpoints of cross-immunogenicity with existing childhood vaccines should be initiated alongside focused global efforts to develop effective treatment for COVID-19, and a safe and effective SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. At least, rapid testing and eventual use of promising, non-COVID-19 vaccines could be explored for help with avoiding large patient casualties in the meantime, until adequate treatment and vaccines are developed.

Certainly, routine pediatric vaccination for other conditions needs to be maintained even in the face of parental fear of potential exposure to COVID-19 during well child visits. Parents need to be reminded of the increased risks for outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases that children and their communities may face upon lifting of social distancing guidelines—unless children are vaccinated appropriately.

Based on our review, it may be concluded that although controlled clinical trials may be time and resource intensive, those may be justificable in investigating further and confirming the value of at least three childhood vaccines: BCG, MMR, and HEP-A as possible explanations for lower incidence of COVID-19, and less severe expression of the disease in children. Currently hypothesized explanations for an evidently less severe impact of COVID-19 on children globally includes the protective cross-immunity provided by other common childhood vaccines. There is a strong basis to hypothesize that immune response to the SARS-CoV-2 virus in children is different than in adults, resulting in differences in the levels of severity of symptoms and outcomes of the disease in different age groups.

Author Contributions

Upon initial suggestion of the topic by the BB-S, JK-H, DR, and SR participated equally in generating the research question, conducting library search, and writing the manuscript and selected articles were divided equally for review and data entering into the common spread sheet. All authors participated in revising and editing the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Situation Report – 209 . (2020) Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200816-covid-19-sitrep-209.pdf?sfvrsn=5dde1ca2_2 (accessed August 31, 2020)

Google Scholar

2. Singh T, Hesto SM, Langel SN, Blasi M, Hurst JH, Fouda GG, et al. Lessons from COVID-19 in children: key hypotheses to guide preventative and therapeutic strategies. Clin Infect Dis. (2020) ciaa547. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa547

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Lee PI, Hu YL, Chen PY, Huang YC, Hsueh PR. Are children less susceptible to COVID-19? J Microbiol Immunol Infect. (2020) 53:371–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2020.02.011

4. Brodin P. Why is COVID-19 so mild in children? Acta Paediatrica. (2020) 109:1082–3. doi: 10.1111/apa.15271

5. Carsetti R, Quintarelli C, Quinti I, Mortari EP, Zumla A, Ippolito G Locatelli F. The immune system of children: the key to understanding SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility? Lancet Child Adolescent Health. (2020) 4:414–6. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30135-8

6. Mehta NS, Mytton OT, Mullins EWS, Fowler TA, Falconer CL, Murphy OB, et al. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19): what do we know about children? A systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. ciaa556. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa556. [Epub ahead of print].

7. Ludvigsson JF. Systematic review of COVID-19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatrica. (2020) 109:1088–95. doi: 10.1111/apa.15270

8. Ma H, Hu J, Tian J, Zhou X, Li H, Laws M et al. Visualizing the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) in children: what we learn from patients at wuhan children's hospital. SSRN Electron J. (2020). doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3556676

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Roser M, Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, Hasell J. Our World in Data: Mortality Risk of COVID-19 . Available online at: https://ourworldindata.org/mortality-risk-covid (accessed June 1, 2020)

10. Salman S, Salem M. Routine childhood immunization may protect against COVID-19. Med Hypotheses. (2020). doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109689. [Epub ahead of print].

11. Shann F. The non-specific effects of vaccines. Arch Dis Childhood. (2010) 95:662–7. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-310282

12. Aaby P, Benn CS, Flanagan KL, Klein SL, Kollmann TR, Lynn DJ, et al. The non-specific and sex-differential effects of vaccines. Nat Rev Immunol. (2020) 20:464–70. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0338-x

13. Google Scholar (2020). Available at: https://scholar.google.co.uk/intl/en/scholar/help.html#coverage (accessed June 1, 2020)

14. O'Neill LA, Netea MG. BCG-induced trained immunity: can it offer protection against COVID-19? Nat Rev Immunol. (2020) 20:335–7. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0337-y

15. Sabir DK, Sidiq KR, Ali SM. Current speculations on the low incidence rate of the COVID-19 among children. Int. J. School. Health. (2020) 7:61–2. doi: 10.30476/intjsh.2020.85997.1066

16. Abdulamir AS, Hafidh RR. The possible immunological pathways for the variable immunopathogenesis of covid-−19 infections among healthy adults, elderly and children. Electron J Gen Med. (2020) 17:em202. doi: 10.29333/ejgm/7850

17. Miller A, Reandelar MJ, Fasciglione K, Roumenova V, Li Y, Otazu GH. Correlation between universal BCG vaccination policy and reduced morbidity and mortality for COVID-19: an epidemiological study. medRxiv [Preprint]. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.03.24.20042937

18. Shet A, Ray D, Malavige N, Santosham M, Bar-Zeev N. Differential COVID-19-attributable mortality and BCG vaccine use in countries. medRxiv [Preprint]. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.04.01.20049478

19. Escobar LE, Molina-Cruz A, Barillas-Mury C. BCG vaccine-induced protection from COVID-19 infection, wishful thinking or a game changer? medRxiv [Preprint] . (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.05.05.20091975

20. Escobar LE, Molina-Cruz A, Barillas-Mury C. BCG vaccine protection from severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2020) 117:17720–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2008410117

21. Paredes JA, Garduño V, Torres J. COVID-19 related mortality: is the BCG vaccine truly effective? medRxiv [Preprint]. (2020). doi: 10.1101/2020.05.01.20087411

22. Hamiel U, Kozer E, Youngster I. SARS-CoV-2 rates in bCG-vaccinated and unvaccinated young adults. JAMA. (2020) 23:2340–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8189

23. Saad M, Elsalamony R. Measles vaccines may provide partial protection against COVID-19. Int J Cancer Biomed Res. (2020) 5:14-19. doi: 10.21608/jcbr.2020.26765.1024

24. Franklin R, Young A, Neumann B, Fernandez R, Joannides A, Reyahi A, et al. Homologous protein domains in SARS-CoV-2 and measles, mumps and rubella viruses: Preliminary evidence that MMR vaccine might provide protection against COVID-19. medRxiv [Preprint]. (2020) doi: 10.1101/2020.04.10.20053207

25. Fidel PL, Noverr MC. Could an unrelated live attenuated vaccine serve as a preventive measure to dampen septic inflammation associated with covid-19 infection? mBio. (2020) 11:e00907–20. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00907-20

26. Sarialioglu F, Apak FBB, Haberal M. Can hepatitis a vaccine provide protection against covid-19? Exp Clin Transpl. (2020) 2:141–3. doi: 10.6002/ect.2020.0109

27. Ahmadpoor PL, Rostaing L. Why the immune system fails to mount an adaptive immune response to a COVID-19 infection. Transpl Int. (2020) 33:824–5. doi: 10.1111/tri.13611

28. Revised BCG vaccination guidelines for infants at risk for HIV infection. Weekly Epidemiol Rec . (2007) 82:193–6.

29. Butkeviciute E, Jones CE, Smith SG. Heterologous effects of infant BCG vaccination: potential mechanisms of immunity. Future Microbiol. (2018) 13:1193–208. doi: 10.2217/fmb-2018-0026

30. Mallapaty S. What the cruise-ship outbreaks reveal about COVID-19. Nature. (2020) 580:18. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-00885-w

31. Mizumoto K, Kagaya K, Zarebski A, and Chowell G. Estimating the asymptomatic proportion of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases on board the Diamond Princess cruise ship, Yokohama, Japan, 2020. Eurosurveillance . (2020). 25:180. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.10.2000180

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text

Keywords: children, vaccines, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, immunization

Citation: Beric-Stojsic B, Kalabalik-Hoganson J, Rizzolo D and Roy S (2020) Childhood Immunization and COVID-19: An Early Narrative Review. Front. Public Health 8:587007. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.587007

Received: 24 July 2020; Accepted: 10 September 2020; Published: 28 October 2020.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2020 Beric-Stojsic, Kalabalik-Hoganson, Rizzolo and Roy. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bojana Beric-Stojsic, bstojsic@fdu.edu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Essay: Vaccination is key to beat COVID-19

Now that COVID-19 vaccines have been developed the question becomes, should I get the vaccine?

While most Rochesterians will get vaccinated , about 30% stated that they would not get the vaccine or were unsure that they would. Underlying diseases, allergies and lack of knowledge on long-term effects were some of the reasons why people were unsure or unwilling to get the vaccine.

More: NY expected to get 170,000 COVID-19 vaccine doses Dec. 15. What to know about who gets it

Here are answers to why getting vaccinated is key to beating COVID-19 and helping us move into a post-pandemic world:

What exactly are the COVID-19 candidate vaccines?

Both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccine candidates are messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines, and considered to be new technology. While mRNA vaccines have never been utilized before, a decade's worth of work and research has gone into this technology to make it efficient and safe for humans.

The AstraZeneca’s vaccine candidate is an adenovirus-based vaccine. The only other adenovirus-based vaccine that has gained FDA approval is the recent Ebola vaccine produced by Merck. Adenovirus was originally isolated from chimpanzees and modified so that it no longer could replicate within human cells, meaning that it could no longer cause a cold.

What is mRNA?

Most cells have an in depth, very detailed code book which is the DNA. The final product of this code book would be the physical products, proteins, made by the code book. mRNA in this case, would be the summary of the code book, where all the unnecessary words are taken out. In terms of an mRNA vaccine, the mRNA would be the very small, concise and specific code for a part of the virus that your cells would make.

Production of this small part of the virus would trigger an immune reaction, allowing for your body to create the antibodies needed against the virus without every introducing the virus itself into your body. Most importantly, your body would never create the entire COVID-19 virus because of the vaccine.

How do the vaccine candidates work?

Both the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccine candidates function the same. They introduce mRNA into your cells that produces a protein "spike" that is found on the surface of the virus. Your cells then read the code for this protein and produce it.

Once the “spike” proteins are produced, your immune system reacts to this foreign object and trains itself to remove the intruder by producing antibodies.

The AstraZeneca vaccine candidate also functions similarly. Instead of asking your cells to produce the spike protein, the adenovirus itself contains that protein. Once introduced to your system, the adenovirus containing the spike protein triggers the immune system to create antibodies so that it can fight against the slight insult to the immune system.

In both cases, once your immune system has made the antibody against the “spike” protein, it retains memory of this and can re-produce the same antibodies needed to fight the virus if you were ever exposed to the actual virus.

Isn’t it bad for your cells to do this long term though?

Long term, most likely. However, the beauty of mRNA that is introduced into your system is that it’s very fragile and has a one-time use typically. Your cells would make the protein “spike” and then the mRNA would be degraded, so your cells would never make the “spike” again.

What about long-term effects?

Long term effects and how long the vaccines will provide immunity are unknown at this point. However, initial data has shown that there are minimal initial effects to the vaccine thus far. The symptoms that were seen, such as a sore arm or feeling unwell for a few days, are typical reactions to vaccines when first given and is a response of your body cranking up productivity to fight against the intrusion.

Long-term effects of the vaccine will be made available once enough time has passed, but generally there is little to fear.

Should I get the vaccine even if I’m unsure or I don’t want to?

Yes, absolutely and emphatically yes.

The science behind the vaccines are sound and initial data suggest that there are no long-term effects to be majorly concerned about. Transparency in science is key and as long as vaccine producers are transparent there is nothing to fear.

Nazish Jeffery is a Rochester native who is pursuing her Ph.D. in biochemistry and molecular biology at the University of Rochester. She is president of the UR Science Policy Initiative.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- For authors

- Browse by collection

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 12, Issue 4

- Intervention studies to encourage vaccination using narrative: a systematic scoping review protocol

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6251-3587 Tsuyoshi Okuhara ,

- Hiroko Okada ,

- Eiko Goto ,

- Takahiro Kiuchi

- Department of Health Communication, School of Public Health , The University of Tokyo , Bunkyo-ku , Japan

- Correspondence to Dr Tsuyoshi Okuhara; okuhara-ctr{at}umin.ac.jp

Introduction Vaccine hesitancy is a global problem, impeding uptake of vaccines against measles, mumps, and rubella and those against human papillomavirus and COVID-19. Effective communication strategy is needed to address vaccine hesitancy. To guide the development of research in the field and the development of effective strategies for vaccine communication, this scoping review aims to analyse studies of interventions using narrative to encourage vaccination.

Methods and analysis We will search the following databases: MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO and PsycARTICLES. We will identify additional literature by searching the reference lists of eligible studies. Eligible studies will be those that quantitatively examined the persuasiveness of narrative to encourage vaccination. Two independent reviewers will screen the titles, abstracts and full texts of all studies identified. Two independent reviewers will share the responsibility for data extraction and verification. Discrepancies will be resolved through consensus. Data such as study characteristics, participant characteristics, methodology, main results and theoretical foundation will be extracted. The findings will be synthesised in a descriptive and a narrative review.

Ethics and dissemination This work does not warrant any ethical or safety concerns. This scoping review will be presented at a relevant conference and published in a peer-reviewed journal.

- INFECTIOUS DISEASES

- Infection control

- Public health

- PUBLIC HEALTH

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053870

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Strengths and limitations of this study

We use the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews checklist, the most current guidance on conducting scoping reviews, in order to ensure a systematic approach to searching, screening and reporting.

As this is a scoping review, formal quality assessment and risk of bias assessment will not be conducted.

This review may miss important literature published in languages other than English.

Introduction

Vaccines have long been lauded as one of the most important public health achievements of the past century. In the past decade, however, a growing number of individuals have begun to perceive vaccination as risky. Vaccine hesitancy, defined as ‘delay in acceptance or refusal of vaccines despite availability of vaccination service’, is a problem attracting growing attention and concern. 1 Vaccine hesitancy impeding uptake of vaccines against measles, mumps, and rubella and COVID-19 vaccines is a global problem. 2–5 Communication can be an effective tool, if used in a planned and integrated strategy, to counteract vaccine hesitancy and promote optimal vaccine uptake. 6

Using narrative to motivate health behaviour is an emerging form of persuasion in public health communication. 7 8 Narrative refers to the use of case stories or examples to support the argument offered by the communicator, 8 such as ‘I suffered greatly from the COVID-19. Therefore, I recommend you receive the COVID-19 vaccine to prevent severe illness due to infection’. Especially in vaccination promotion, using narrative is proposed to counter antivaccination messages in mass media and on the internet, which propagate doubt, fear and opposition to vaccination. 9 These antivaccination messages often use an emotional narrative of alleged victims of a vaccine’s side effects. 10 Scholars of vaccine communication have recently directed their interest to using narrative effectively as well, such as describing people feeling secure at recognising that they and their loved ones are protected by vaccination, or describing an experience of a person whose health suffered because of a preventable disease. 11 12

However, health-related narrative persuasion research is still emerging. Published studies remain relatively small in number, and few studies have measured health-behaviour outcomes in non-student participants. 13 To our knowledge, no study has reviewed previous studies of interventions aimed at encouraging vaccination using narrative to determine which vaccines have been targeted, what study designs have been adopted (eg, participant background, sample size, randomisation), and what outcomes have been measured (eg, vaccination behaviour, behavioural intentions, attitudes). Reviewing them will be important for developing the field of study to encourage vaccination using narrative, for critically examining the results of previous studies, and for applying them to vaccine communication practice.

Recent studies on vaccine communication have shown that narrative messages that recount personal experiences with disease increase an audience’s perception of the risk of developing disease, intention to vaccinate and likelihood of changing behaviour to prevent infectious disease, compared with didactic messages. 14 However, communication scholars have not yet reached consensus regarding the persuasiveness of narrative versus didactic messages, and the optimal usage thereof. 15 No studies have reviewed what form of intervention (eg, statistics) previous studies have adopted to quantify the persuasiveness of narrative to encourage vaccination, and what results those studies have shown.

Although theoretical developments in understanding the mechanisms and processes involved in narrative persuasion remain limited, 16 several theoretical perspectives have been proposed to explain how and why narrative communication may contribute to attitudinal and behavioural changes. The earliest studies applied models of behaviour change—the most representative being social cognitive theory. 17 Then, theories of persuasion in psychology—the most representative being the extended elaboration likelihood model 18 and the transportation-imagery model 19 —were proposed and evaluated. However, no studies have reviewed which theories and models formed the basis for previous intervention studies of encouraging vaccination using narrative.

The objective of this review is to create an overview of studies of interventions aimed at encouraging vaccination using narrative, and to identify the content and gaps in these studies. This scoping review will serve as a useful reference for researchers who plan future intervention studies on vaccine communication using narrative, speeding up their research and helping them to conduct better-designed intervention studies. This work will be useful in guiding the development of research in the field and the development of effective strategies for vaccine communication and addressing vaccine hesitancy. Our research questions will be as follows. These wide review objectives and questions will be best achieved and answered through a scoping review.

RQ1: What study designs have previous intervention studies adopted to examine the persuasiveness of narrative approaches in encouraging vaccination?

RQ2: What outcomes have previous intervention studies measured to examine the persuasiveness of narrative approaches in encouraging vaccination?

RQ3: What forms of intervention other than using narrative have previous intervention studies adopted to compare and combine with the persuasiveness of narrative in encouraging vaccination?

RQ4: What results have previous intervention studies shown about the persuasiveness of narrative approaches in encouraging vaccination including comparisons and combinations with other forms of intervention than using narrative?

RQ5: Which theories and models have been used in previous intervention studies to explain the persuasiveness of narrative in encouraging vaccination?

Methods and analysis

This systematic scoping review protocol is prepared according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews checklist (see online supplemental file 1 ). 20 The planned start date for the study is 1 April 2022, and the planned end date is 31 March 2023.

Supplemental material

Literature search.

Using the EBSCOhost Search Platform, we will search the following databases: MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES. We will search the abstracts using the combination of keywords: (vaccine OR vaccination OR immunization) AND (narrative OR story OR storytelling). We will search the reference lists of identified eligible studies to identify any additional potentially eligible literature.

Eligibility criteria

We seek to include all intervention studies in these databases that quantitatively examined the persuasiveness of narrative to encourage vaccination, both experimental (eg, randomised controlled trials, quasi-randomised controlled trials, non-randomised trials) and quasi-experimental research (eg, pretest–post-test design, post-test design). All comparators will be eligible (ie, any forms of intervention other than using narrative). Studies without a comparator will also be eligible. Grey literature (information produced outside of traditional publishing and distribution channels, such as conference proceedings) will be included if it provides enough information to assess its eligibility. Qualitative studies will be excluded.

Studies assessing any outcomes such as behaviour, behavioural intention and attitude will be eligible, as will studies of any kind of vaccination. Studies on participants of any age, gender, ethnicity and countries will be eligible, and we will not filter by year. Only papers written in English will be included; studies not published in full text will be excluded.

Study selection

Two independent reviewers including the first author (TO) will screen the titles and abstracts of all studies initially identified, according to the eligibility criteria. Disagreements will be resolved by consensus; the opinion of a third reviewer will be sought if necessary. The full text versions of potentially relevant studies will be retrieved and screened independently by two reviewers including the first author (TO). Consensus will be reached through discussion, and if no consensus can be reached on any study, a third reviewer will arbitrate. All studies not meeting the eligibility criteria will be excluded. The results will be displayed in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram.

Data extraction and reporting the results

A customised data extraction form will be created to extract all relevant data from each study. The data extraction form will be piloted in a sample of the eligible studies to assess its reliability in extracting the targeted study data. The first author (TO) will conduct data extraction, and another author will check the extracted data against the full texts of the studies to ensure that there are no omissions or errors. Consensus will be reached through discussion, and if no consensus can be reached on any study, a third reviewer will arbitrate. The following data will be extracted: study characteristics (author, year of publication, type of paper and country), participant characteristics (student or non-student, gender, age and other demographic information), methodology (study design, sample size and outcome), comparators and combinations (forms of intervention other than using narrative), main results of the intervention including comparison and combination with other forms of intervention than using narrative, and theoretical foundation of the intervention. The findings will be summarised in a concise table and synthesised in a descriptive and narrative review. We will discuss the findings and their implications for future research and practice as we answer each of the research questions.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Ethics and dissemination

This work does not warrant any ethical or safety concerns. We intend to present the results of this review at a relevant conference and publish them in a peer-reviewed journal.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank John Daniel from Edanz ( https://jp.edanz.com/ac ) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

- MacDonald NE , SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy

- Robinson E ,

- Lesser I , et al

- Bankamp B ,

- Hickman C ,

- Icenogle JP , et al

- Wilder-Smith AB ,

- Goldstein S ,

- MacDonald NE ,

- Guirguis S , et al

- Hinyard LJ ,

- Braddock K ,

- Brewer NT ,

- Brocard P , et al

- MacDonald NE

- de Graaf A ,

- Sanders J ,

- Pietrantoni L ,

- Winterbottom A ,

- Bekker HL ,

- Conner M , et al

- Moyer-Gusé E

- Slater MD ,

- Tricco AC ,

- Zarin W , et al

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data.

This web only file has been produced by the BMJ Publishing Group from an electronic file supplied by the author(s) and has not been edited for content.

- Data supplement 1

Contributors All authors have made substantive intellectual contributions to the development of this protocol. TO was involved in conceptualising this review and in writing this protocol. HO, EG and TK commented critically on several drafts of the manuscript.

Funding This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI (grant number 19K10615, 19K22743).

Competing interests None declared.

Patient and public involvement Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

A Narrative Review of COVID-19 Vaccines

Affiliation.

- 1 Sydney Pharmacy School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney 2006, Australia.

- PMID: 35062723

- PMCID: PMC8779282

- DOI: 10.3390/vaccines10010062

The COVID-19 pandemic has shaken the world since early 2020 and its health, social, economic, and societal negative impacts at the global scale have been catastrophic. Since the early days of the pandemic, development of safe and effective vaccines was judged to be the best possible tool to minimize the effects of this pandemic. Drastic public health measures were put into place to stop the spread of the virus, with the hope that vaccines would be available soon. Thanks to the extraordinary commitments of many organizations and individuals from around the globe and the collaborative effort of many international scientists, vaccines against COVID-19 received regulatory approval for emergency human use in many jurisdictions in less than a year after the identification of the viral sequence. Several of these vaccines have been in use for some time; however, the pandemic is still ongoing and likely to persist for the foreseeable future. This is due to many reasons including reduced compliance with public health restrictions, limited vaccine manufacturing/distribution capacity, high rates of vaccine hesitancy, and the emergence of new variants with the capacity to spread more easily and to evade current vaccines. Here we discuss the discovery and availability of COVID-19 vaccines and evolving issues around mass vaccination programs.

Keywords: COVID-19; COVID-19 vaccines; SARS-CoV-2; vaccination; vaccine hesitancy.

Publication types

- High contrast

- About UNICEF

- Children in South Asia

- Where we work

- Regional Director

- Goodwill ambassador

- Work with us

- Press centre

Search UNICEF

My covid-19 vaccination experience, interview with an educator.

Photo: (Left to right) Hasina pictured with her three daughters, Nafisa (19), Lamia (29) and Maliha (30).

Children in Bangladesh have faced some of the worst disruption to their education in the whole world.

Schools have been completely closed since March 2020 — shutting 42 million children off from their education and the support networks many rely on to stay safe and thrive, for over a year.

Hasina Saki is part of this support network for children in Chittagong, Bangladesh. She works as Head Assistant of Administration at a government high school.

Across the world, many educators, especially younger ones, are not being prioritized for COVID-19 vaccines — putting them, and the children who rely on them, at risk.

At fifty-seven-year-old, Hasina was prioritised for a COVID-19 vaccination in Bangladesh because of her age, and on March 1st she received her first dose of the vaccine.

Ahead of her second dose at the end of this month, she tells us about her vaccination, the impact it’s had so far on her work with children (and life with her own) — and why she won’t stop taking actions to protect herself and others now that she’s been vaccinated.

How do you feel about getting the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine?

It was definitely mixed feelings at first. It was relief with some hesitance.

But, as soon as the vaccination process started throughout the country all my questions vanished at once. The amazingly efficient and systematic vaccination procedure felt like a festival; a festival of life, a festival of hope.

So, the biggest emotion that I associate with being vaccinated is most definitely hope!

How has being vaccinated changed your daily life?

Schools have not reopened for children in Bangladesh, but I’m in the administrative department of the school, which is considered an office — and these are open. I need to go into school to complete administrative duties.

I am definitely feeling much more at peace after getting vaccinated.

But of course, we all have to be patient and strong until we all make it through this pandemic together.

As much as I hope that the vaccine protects me physically, I am still very much trying to abide by all the basic hygiene and safety measures that COVID taught us.

What does your vaccination mean to your family?

This means a lot to us. Being a working mother, COVID has been quite a challenge for me.

So, me getting vaccinated is hopefully providing my whole family with some reassurance.

What does your vaccination mean for your community?

Bangladesh is a heavily populated country, so COVID-19 makes for a very fragile and risky situation.

This smooth and fast vaccination program is vital for our country. We are very grateful to receive the vaccine now, when we really need it.

What does COVID-19 vaccination mean for the children at your school?

I’m optimistic that ongoing COVID-19 vaccinations will spell good news for the children of the school.

As more people get vaccinated, hopefully schools will reopen soon.

I hope that all the staff at work are able to get vaccinated as soon as possible.

What advice would you give to others about being vaccinated for COVID-19?

I suggest to everyone who gets the opportunity to be vaccinated, to keep a positive, hopeful and grateful attitude.

Surely the world will get through this stronger. We all have to do our part. Together, we’re stronger.

UNICEF South Asia would like to extend huge thanks to Hasina for taking the time to talk to us about COVID-19 vaccines.

We must do everything in our power to safeguard the future of the next generation. This begins by safeguarding those responsible for opening that future up for them — regardless of their age or institution.

The more educators, health workers and social workers who are vaccinated against COVID-19, the more opportunities and protection for the children who rely on them.

If you have an upcoming COVID-19 vaccination, read up on tips from our health experts on what to expect and how to prepare .

After being vaccinated, it’s important you continue the behaviours that protect yourself and others against COVID-19 by:

Washing your hands with soap and water for a minimum of 20 seconds, or hand sanitizer — as often as you can.

Keeping at least 1 metre distance between yourself and others.

Meeting people in well ventilated, or outdoor spaces

Wearing a mask when you can’t keep your distance from others, or are inside a public space.

This is because COVID-19 vaccines have proven effective at stopping people from developing the virus, but we don't yet know whether they prevent people from passing the infection onto others.

This is especially important until two weeks after your second dose of the vaccine. During this period, your body is still building protection against the virus — and while it is you could still get sick.

Related topics

More to explore, refrigerated trucks for vaccines handed over.

The trucks, which can carry four million vaccine doses each, will support the government’s efforts to strengthen its immunisation programme.

Poor Diets Damaging Children’s Health

Dr. naznin akter’s journey in safeguarding special girl chil.

n the battle against cervical cancer, a determined mother and doctor diligently works to protect girls against this deadly disease

Testing Fun Ways to Interest Children in Climate Change

Schools in Bangladesh are testing fun ways to interest children in climate change and nature issues from an early age

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

Defining the COVID-19 Narrative

The story we tell about this pandemic will shape our preparedness for the next..

Posted July 6, 2021 | Reviewed by Vanessa Lancaster

- The core narrative of the pandemic, and arguably the central one, is the presence of inequities.

- COVID-19 exposed inequities in morbidity and mortality, who bears the burden of steps we have taken to mitigate the virus, and vaccine uptake.

- The effects of these inequities will likely be with us for some time, shaping the story of the pandemic and the lives of those who lived it.

What story will we tell about COVID-19 ? The events of the past year and a half were more than just a story of the emergence and behavior of a virus. It was also a story of the social, economic, scientific, and political context into which the virus emerged and the intersection of these forces within complex, dynamic systems. Given this complexity, it can be challenging to predict which stories will rise to the surface of the overarching story of the pandemic. Yet, we need to try. The stories we tell about health shape how we engage with the present moment to support a better future—or how we fail to do so.

With this in mind, I suggest four critical narratives that emerged from the broader story of the pandemic and which can help define the overall COVID-19 narrative in the years to come. Next week, I will address the perhaps deeper issue of why we remember what we remember.

The first narrative which has come to define the COVID-19 moment is that of scientific excellence. The speed with which a COVID-19 vaccine was developed, supported by mRNA technology, reflects a new era in cutting -edge science. This narrative of scientific excellence is powerful for two key reasons.

First, because this latest vaccine technology is unique and impressive and has begun the long-awaited process of helping return us to our families, friends, colleagues, lives. Second, it is powerful because of how closely it aligns with how we already think about health. We often think about health in terms of treatment—doctors and medicines—which can cure us when we are sick, rather than in terms of the structural forces in society which shape whether or not we get sick, to begin with. We tend to confuse health (the state of not being sick) with healthcare (what we turn to once sickness strikes), which has led us to invest vast sums in healthcare at the expense of the core forces that shape health. The success of vaccines reflects that this investment is indeed core to supporting scientific excellence. Still, our story of health and COVID-19 is incomplete if it is confined to science and treatment alone.

This leads to the following core narrative of the pandemic and arguably the central one—the presence of inequities. These include, centrally, inequities in morbidity and mortality, who bears the burden of the steps we have taken to mitigate the virus and vaccine uptake. When COVID-19 struck, it quickly became apparent that certain groups—such as Black Americans, people over 65, and people with underlying health conditions—were more vulnerable to the virus than others. This vulnerability was shaped by longstanding health inequities informed by marginalization, social and economic injustice, and other foundational forces in our society. The story of COVID-19 is, in large part, the level of these forces.

These inequities have also come to define who has most felt the consequences of our efforts to mitigate the pandemic. COVID-19 caused us to embrace extraordinary measures, shut down society, and incur severe economic costs in the process. The pandemic led to significant job losses , which most affected low-income, minority workers. When the economy began to recover, with higher-wage workers bouncing back relatively quickly, lower-wage minority workers recovered at a far slower rate. The effects of this inequity will likely be with us for some time, shaping the story of the pandemic and the lives of those who lived it.

Third, the story of COVID-19 would be incomplete without an honest reckoning with widespread loss of trust in institutions and the consequences of this for public health. The most prominent example of this was how the inconsistent, often dishonest, words of former President Trump informed a lack of trust in guidance from the White House throughout the crisis. It is also true that seeming inconsistencies occasionally characterized public health efforts, perhaps most clearly in our field’s widespread embrace of civic protests last summer, in apparent contrast with our guidance on social distancing and masks. Given that COVID-19 emerged at a time when trust in institutions was already declining , the story of the pandemic may well be, in large part, a story of how this trend accelerated, making it harder for anyone to speak with a widely-heeded, authoritative voice on matters core to health.

Finally, a core narrative of the pandemic, one which could well characterize our future memory of this time, is that, as bad as COVID-19 was, it could have been far worse. I realize that this may seem strange, even unfeeling, in the context of mass death and suffering. But it is nevertheless true. COVID-19 has been a disaster. Yet, the virus itself, compared to past pandemics, is nowhere near as lethal as it might have been. A future pandemic could combine the high transmissibility of COVID-19 with the lethality of, say, SARS or even of the Black Death. While the latter may seem historically remote, there is no reason why we could not see something as deadly strike in our own time. The better we understand this, the more the story we tell about COVID-19 can help inform our efforts to build a world that is no longer vulnerable to contagion.

Each of these stories represents a vital part of the broader narrative of COVID-19. It is also the case that one or two of these narratives may rise even further to the top of our minds to conclusively define this era. Only time will tell for sure what will happen. However, I would argue several factors contribute to making stories stick when we think back on critical events, which increases the chance that the stories I have presented here will long outlast this moment. I will explore these factors and how we come to believe what we believe in our narratives next week.

This piece was also posted on Substack.

Sandro Galea, M.D., is the Robert A. Knox professor and dean of the Boston University School of Public Health

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Persuasive Essay Guide

Persuasive Essay About Covid19

How to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid19 | Examples & Tips

11 min read

People also read

A Comprehensive Guide to Writing an Effective Persuasive Essay

200+ Persuasive Essay Topics to Help You Out

Learn How to Create a Persuasive Essay Outline

30+ Free Persuasive Essay Examples To Get You Started

Read Excellent Examples of Persuasive Essay About Gun Control

Crafting a Convincing Persuasive Essay About Abortion

Learn to Write Persuasive Essay About Business With Examples and Tips

Check Out 12 Persuasive Essay About Online Education Examples

Persuasive Essay About Smoking - Making a Powerful Argument with Examples

Are you looking to write a persuasive essay about the Covid-19 pandemic?

Writing a compelling and informative essay about this global crisis can be challenging. It requires researching the latest information, understanding the facts, and presenting your argument persuasively.

But don’t worry! with some guidance from experts, you’ll be able to write an effective and persuasive essay about Covid-19.

In this blog post, we’ll outline the basics of writing a persuasive essay . We’ll provide clear examples, helpful tips, and essential information for crafting your own persuasive piece on Covid-19.

Read on to get started on your essay.

- 1. Steps to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

- 2. Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid19

- 3. Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Vaccine

- 4. Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Integration

- 5. Examples of Argumentative Essay About Covid 19

- 6. Examples of Persuasive Speeches About Covid-19

- 7. Tips to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

- 8. Common Topics for a Persuasive Essay on COVID-19

Steps to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

Here are the steps to help you write a persuasive essay on this topic, along with an example essay:

Step 1: Choose a Specific Thesis Statement

Your thesis statement should clearly state your position on a specific aspect of COVID-19. It should be debatable and clear. For example:

Step 2: Research and Gather Information

Collect reliable and up-to-date information from reputable sources to support your thesis statement. This may include statistics, expert opinions, and scientific studies. For instance:

- COVID-19 vaccination effectiveness data

- Information on vaccine mandates in different countries

- Expert statements from health organizations like the WHO or CDC

Step 3: Outline Your Essay

Create a clear and organized outline to structure your essay. A persuasive essay typically follows this structure:

- Introduction

- Background Information

- Body Paragraphs (with supporting evidence)

- Counterarguments (addressing opposing views)

Step 4: Write the Introduction

In the introduction, grab your reader's attention and present your thesis statement. For example:

Step 5: Provide Background Information

Offer context and background information to help your readers understand the issue better. For instance:

Step 6: Develop Body Paragraphs

Each body paragraph should present a single point or piece of evidence that supports your thesis statement. Use clear topic sentences, evidence, and analysis. Here's an example:

Step 7: Address Counterarguments

Acknowledge opposing viewpoints and refute them with strong counterarguments. This demonstrates that you've considered different perspectives. For example:

Step 8: Write the Conclusion

Summarize your main points and restate your thesis statement in the conclusion. End with a strong call to action or thought-provoking statement. For instance:

Step 9: Revise and Proofread

Edit your essay for clarity, coherence, grammar, and spelling errors. Ensure that your argument flows logically.

Step 10: Cite Your Sources

Include proper citations and a bibliography page to give credit to your sources.

Remember to adjust your approach and arguments based on your target audience and the specific angle you want to take in your persuasive essay about COVID-19.

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid19

When writing a persuasive essay about the Covid-19 pandemic, it’s important to consider how you want to present your argument. To help you get started, here are some example essays for you to read:

Check out some more PDF examples below:

Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Pandemic

Sample Of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 In The Philippines - Example

If you're in search of a compelling persuasive essay on business, don't miss out on our “ persuasive essay about business ” blog!

Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Vaccine

Covid19 vaccines are one of the ways to prevent the spread of Covid-19, but they have been a source of controversy. Different sides argue about the benefits or dangers of the new vaccines. Whatever your point of view is, writing a persuasive essay about it is a good way of organizing your thoughts and persuading others.

A persuasive essay about the Covid-19 vaccine could consider the benefits of getting vaccinated as well as the potential side effects.

Below are some examples of persuasive essays on getting vaccinated for Covid-19.

Covid19 Vaccine Persuasive Essay

Persuasive Essay on Covid Vaccines

Interested in thought-provoking discussions on abortion? Read our persuasive essay about abortion blog to eplore arguments!

Examples of Persuasive Essay About Covid-19 Integration

Covid19 has drastically changed the way people interact in schools, markets, and workplaces. In short, it has affected all aspects of life. However, people have started to learn to live with Covid19.

Writing a persuasive essay about it shouldn't be stressful. Read the sample essay below to get idea for your own essay about Covid19 integration.

Persuasive Essay About Working From Home During Covid19

Searching for the topic of Online Education? Our persuasive essay about online education is a must-read.

Examples of Argumentative Essay About Covid 19

Covid-19 has been an ever-evolving issue, with new developments and discoveries being made on a daily basis.

Writing an argumentative essay about such an issue is both interesting and challenging. It allows you to evaluate different aspects of the pandemic, as well as consider potential solutions.

Here are some examples of argumentative essays on Covid19.

Argumentative Essay About Covid19 Sample

Argumentative Essay About Covid19 With Introduction Body and Conclusion

Looking for a persuasive take on the topic of smoking? You'll find it all related arguments in out Persuasive Essay About Smoking blog!

Examples of Persuasive Speeches About Covid-19

Do you need to prepare a speech about Covid19 and need examples? We have them for you!

Persuasive speeches about Covid-19 can provide the audience with valuable insights on how to best handle the pandemic. They can be used to advocate for specific changes in policies or simply raise awareness about the virus.

Check out some examples of persuasive speeches on Covid-19:

Persuasive Speech About Covid-19 Example

Persuasive Speech About Vaccine For Covid-19

You can also read persuasive essay examples on other topics to master your persuasive techniques!

Tips to Write a Persuasive Essay About Covid-19

Writing a persuasive essay about COVID-19 requires a thoughtful approach to present your arguments effectively.

Here are some tips to help you craft a compelling persuasive essay on this topic:

Choose a Specific Angle

Start by narrowing down your focus. COVID-19 is a broad topic, so selecting a specific aspect or issue related to it will make your essay more persuasive and manageable. For example, you could focus on vaccination, public health measures, the economic impact, or misinformation.

Provide Credible Sources

Support your arguments with credible sources such as scientific studies, government reports, and reputable news outlets. Reliable sources enhance the credibility of your essay.

Use Persuasive Language

Employ persuasive techniques, such as ethos (establishing credibility), pathos (appealing to emotions), and logos (using logic and evidence). Use vivid examples and anecdotes to make your points relatable.

Organize Your Essay

Structure your essay involves creating a persuasive essay outline and establishing a logical flow from one point to the next. Each paragraph should focus on a single point, and transitions between paragraphs should be smooth and logical.

Emphasize Benefits

Highlight the benefits of your proposed actions or viewpoints. Explain how your suggestions can improve public health, safety, or well-being. Make it clear why your audience should support your position.

Use Visuals -H3

Incorporate graphs, charts, and statistics when applicable. Visual aids can reinforce your arguments and make complex data more accessible to your readers.

Call to Action

End your essay with a strong call to action. Encourage your readers to take a specific step or consider your viewpoint. Make it clear what you want them to do or think after reading your essay.

Revise and Edit

Proofread your essay for grammar, spelling, and clarity. Make sure your arguments are well-structured and that your writing flows smoothly.

Seek Feedback

Have someone else read your essay to get feedback. They may offer valuable insights and help you identify areas where your persuasive techniques can be improved.

Tough Essay Due? Hire Tough Writers!

Common Topics for a Persuasive Essay on COVID-19

Here are some persuasive essay topics on COVID-19:

- The Importance of Vaccination Mandates for COVID-19 Control

- Balancing Public Health and Personal Freedom During a Pandemic

- The Economic Impact of Lockdowns vs. Public Health Benefits

- The Role of Misinformation in Fueling Vaccine Hesitancy

- Remote Learning vs. In-Person Education: What's Best for Students?

- The Ethics of Vaccine Distribution: Prioritizing Vulnerable Populations

- The Mental Health Crisis Amidst the COVID-19 Pandemic