Italian Culture Essay

This Italy culture essay sample explores different aspects of Italian culture, including religion, art, language, and food. Check out our Italian culture essay to get some inspiration for your assignment!

Italian Culture Essay Introduction

Religion as an element of italian culture, italian beliefs and traditions, italian arts, italian language, italian food, politics of italy, italy culture essay conclusion.

Many scholars consider Italy to be the birthplace of human culture and the cradle of civilization as we know it. Lying under the bright hot sun of the southern part of Europe, Italy has been basking in scrutinizing public attention for as long as it has existed. It is one of the key players in the arena of world importance.

One can say without any exaggeration that, to a degree, the entire world has been affected by Italy’s cultural and belief systems. Of course, Western culture has benefited from Italian teachings the most: its art, science, education, philosophy, and religion all can be traced back to Italy.

Like any country out there, modern Italy and its population are different from those of ancient times. Today, Italian people carry a mixture of cultures and belief systems introduced by immigrants from all over the world. Economically, Italy has also had a far-reaching effect on the rest of the world.

Italy is probably best known for its being the originator of Catholicism practices. That is where the Catholic Church, the largest and most famous Christian branch, started to spread its word. The majority of Italians are Roman Catholics, and the common religious beliefs in the country are based on the teachings of Catholicism. Vatican City, the world-famous “country within a country,” aka “the smallest country in the world,” is the headquarters of the Roman Catholicism.

Although the Catholic Church has mostly separated its affairs from the state, it still has a vital cultural role to play. Catholicism is a natural part of Italian life that is to be taken for granted. It’s an inevitable cultural, social, and political force that Italians take “with the whole package.”

Of course, there are other religions present too: Islam and some other Christian churches occupy around 15% of the country’s religious beliefs. Generally, Italians believe in life after death, and that there will be appropriate consequences for good and bad people, which is an eternity in Heaven or Hell, accordingly.

Italians are famous for having very close family ties and regarding them very highly. Italian family values and connections are a crucial part of the Italian community, with both sides of the family getting equal attention and treatment. Traditionally, marriage used to be an arranged affair in Italian culture. Of course, nowadays, customs in Italy are not strict, and marriage is an exercise of free will.

Only recently, divorce has become possible in Italy. Before that, with the cult of family values and life-long commitment, it was forbidden. Also, it’s important to point out that, although most Italians marry, it’s customary for children to do it later in life and stay unmarried to take care of the family’s older members. As for inheritance, both male and female members of the family are regarded equally.

Traditionally, there was a strict gendered role division in Italian society, which has changed in modern times. Nevertheless, the family is still the basic unit of Italian society. In most cases, husbands are viewed to be the heads of their families.

The high importance of physical appearance for Italians needs to be acknowledged. Dressing style, body stature, and personal hygiene are usually taken great care of. Italians are very fashion conscious, and to them, to produce the right first impression is crucial.

Other than the Catholic Church, Italy is probably only more famous for its arts. Italian tradition is rich in all forms of it – architecture, painting, sculpture, poetry, opera, theater, and many others. Strictly speaking, it’s the arts to be thanked for bringing all of the annual millions of tourists to Italy. It’s not surprising that the arts in Italy get all the support from both the public and private sectors. This support has ensured the world’s undying interest in Italy to this date.

From ancient times, architecture and sculpture have dominated the Italians’ art world. The preserved relics of buildings and statues remain to be the highlights of Italian tourism. Many best-known pieces of sculpture were created in the middle ages and were mostly religious.

Until the 13th century, written literature in Italy was mostly done in Latin. Italian works in poetry, theology, and philosophy continue to shape the modern intellectual world. Music writing also started in Italy, which is why the Italian language is used by music teachers to explain how music should be played to this date.

A lot of people from all over the world share the opinion that Italian is the most musical language. Although it is a very subjective matter, drawing its judgment from personal tastes, there is a common belief that the Italian language is gentle, melodic, and sounds almost like a song. There is a scientific explanation to that – the Italian language enjoys using vowels a lot. For instance, almost all Italian words end with a vowel, and frequent use of double consonants is only adding to sample the musical factor.

Already in pre-Renaissance times, Italian was considered to be the language of the European culture. During this period, the greatest humanitarians and writers of the time flourished to contribute to the scientific world, traditionally writing them in Latin.

Italian was not just the language of science – its recognition as a noble language was achieved through its outstanding works in the musical sphere. The Italian language got its first praises from writers and scholars worldwide as early as the 17th century.

Voltaire, a well known French philosopher and writer, spoke with appreciation of the “beautiful Italian language, Latin’s firstborn sibling.” For James Howell, an English historian, and writer, Italian was “the best-composed language in terms of fluency and smoothness.”

Italian is the official language of the country and is spoken by the majority of citizens. Some dialects are recognized in a few regions, which are sometimes considered to be different languages.

Italian food has also gained worldwide fame – arguably more so than any other aspect of Italian culture. Who hasn’t tried pasta in their life? And pizza’s popularity is hard to argue about – ask any kid, and they will tell you how they love eating pizza most in the world.

Of course, there are specific differences in preparing the food in various regions, but spaghetti, pizza, bread, soup, meat, and vine are common in all areas.

The current Italian constitution came into effect on 1st January 1948. That’s when the people of Italy voted to have a Republic and not a monarchy. Italian parliament consists of the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate. The Italian government has three branches: executive, judiciary, and legislature.

The President is elected every seven years and must be less than 50 years old. The prime minister is appointed by the President, whose duty is to form a government. The President is the commander of armed forces, and it’s in their power to dissolve parliament and call for new elections. There is no Vice President in Italy, so, if the President dies, elections will have to be held.

Italy is a member of various organizations, including but not limited to North Atlantic Treaty Organization, European Union, and Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe.

Writing about Italy is relatively easy and certainly very pleasant. Whether you are writing an Italian culture research paper or a cultural analysis, there is enough material and ideas for Italian essay topics to cover almost any sphere you wish in your culture project. Italian heritage has its deep imprint on every part of the Western culture, including your essay example.

What is Italian culture known for?

The common associations with Italian culture are art, religion, and food. Italy is the inheritor of the Roman Empire and the homeland of the Catholic Church. It was also the center of the Renaissance, which gave new life to European culture. Italian culture has flourished for centuries, having a significant influence on all aspects of Western culture, politics, and religion.

What makes Italian culture unique?

Italy is widely considered to be the cradle of Western civilization. It’s impossible to deny the superpower of Italian culture, and it’s overwhelming influence on the rest of the world, Western culture in particular. Through the centuries, Italy and its cultural heritage have affected how science, arts, politics, and religion are practiced in the Western world.

Why is Italian food so popular?

One of the first things to associate with Italy and its culture is the famous Italian cuisine. Italian recipes are simple enough, yet they offer great flexibility in the level of intricacy of preparation. In other words, provided the good quality of products, anyone can make pizza or pasta, whether they are a chef or a 10-year-old.

How do Italian Renaissance artists participate in humanist culture?

Humanism defined the Italian Renaissance, emphasizing the individual worth as opposed to a religious figure or the state. Humanism was based on the study of classics, and its philosophy encouraged secular elements in the works of contemporary artists, writers, and philosophers. Human emotions and experiences are the centers of the intellectual and artistic accomplishments of the period.

How is Italian culture different from American?

One of the most noticeable cultural differences noted by travelers from or to America and Italy is the average pace. People usually note that the speed in Italian culture is far slower than in American one. Italians are also said to be not as punctual as Americans and are famous for taking food and leisure breaks seriously.

Italian Culture: Facts, Customs & Traditions (Live Science)

Italian Culture: Cultural Atlas

Italy – Language, Culture, Customs and Etiquette (Commisceo Global)

Italian cuisine: Takeaway.com

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2020, July 7). Italian Culture Essay. https://studycorgi.com/italian-culture-essay/

"Italian Culture Essay." StudyCorgi , 7 July 2020, studycorgi.com/italian-culture-essay/.

StudyCorgi . (2020) 'Italian Culture Essay'. 7 July.

1. StudyCorgi . "Italian Culture Essay." July 7, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/italian-culture-essay/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Italian Culture Essay." July 7, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/italian-culture-essay/.

StudyCorgi . 2020. "Italian Culture Essay." July 7, 2020. https://studycorgi.com/italian-culture-essay/.

This paper, “Italian Culture Essay”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: January 24, 2024 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

Italian Culture: Facts, customs & traditions

Italian culture traces its roots back to the ancient world and has influenced art, fashion and food around the world.

Population of Italy

Languages of italy, family life in italy, religion in italy, art and architecture in italy, italian food, italian fashion, doing business in italy, italian holidays, additional resources and reading, bibliography.

Italian culture is the amalgamation of thousands of years of heritage and tradition, tracing its roots back to the Ancient Roman Empire and beyond. Italian culture is steeped in the arts, family, architecture, music and food. Home of the Roman Empire and its legendary figures such as Julius Caesa r and Nero , it was also a major center of the Renaissance and the birthplace of fascism under Benito Mussolini. Culture on the Italian peninsula has flourished for centuries. Here is a brief overview of Italian customs and traditions as we know them today.

According to the Italian National Institute of Statistics , Italy is home to approximately 59.6 million individuals as of 1 January 2020. About 96 percent of the population of Italy are ethnic Italians according to Jen Green, author of " Focus On Italy " (Gareth Stevens Publishing, 2007), though there are many other ethnicities that live in this country. North African Arab, Italo-Albanian, Albanian, German, Austrian and some other European groups fill out the remainder of the population. Bordering countries of France, Switzerland, Austria, and Slovenia to the north have influenced Italian culture, as have the Mediterranean islands of Sardinia and Sicily and Sardinia.

Of the 59.6 million people living in Italy as of 1 January 2020, 48.7 percent are men, 51.3 percent are women. 13 percent are children aged up to 15, 63.8 percent are believed to be aged 15 – 64 and 23.2 percent are 65 or older. 14,804 are 100 years old or older. The largest percentage of the population, 26.8, lives in the North West of Italy. The largest city by population is Rome with over 2.8 million residents, while the smallest municipality is Morterone with a population of just 30 people.

The official language of the country is Italian. About 93 percent of the Italian population speaks Italian as native language, according to the BBC . There are a number of dialects of the language spoken in the country, including Sardinian, Friulian, Neapolitan, Sicilian, Ligurian, Piedmontese, Venetian and Calabrian. Milanese is also spoken in Milan. Other languages spoken by native Italians include Albanian, Bavarian, Catalan, Cimbrian, Corsican, Croatian, French, German, Greek, Slovenian and Walser.

"Family is an extremely important value within the Italian culture," Talia Wagner, a Los Angeles-based marriage and family therapist, told Live Science. Their family solidarity is focused on extended family rather than the West's idea of "the nuclear family," of just a mom, dad and kids, Wagner explained.

Italians have frequent family gatherings and enjoy spending time with those in their family. "Children are reared to remain close to the family upon adulthood and incorporate their future family into the larger network," said Wagner.

The family structure has changed somewhat over the last 60 years. Gian Carlo Blangiardo, professor of Statistics and Quantitative Methods at the University of Milano-Bicocca and Stefania Rimoldi, researcher in demography at the University of Milano-Bicocca, explained in " Portraits of the Italian Family: Past, Present and Future " for the "Journal of Comparative Family Studies Vol. 45" (University of Toronto Press, 2014)that the mean age of a marriage is now 31 for women and 34 for men, seven years older than it was in 1975. This has been linked to an increase in cohabitation before marriage and an overall decline in the number of marriages.

The major religion in Italy is Roman Catholicism. This is not surprising, as Vatican City, located in the heart of Rome, is the hub of Roman Catholicism and where the Pope resides. Roman Catholics and other Christians make up 80 percent of the population, though only one-third of those are practicing Catholics. The country also has a growing Muslim immigrant community, according to the University of Michigan . Muslim, agnostic and atheist make up the other 20 percent of the population, according to the Central Intelligence Agency .

The number of Italians who attend religious services at least once a week has declined substantially from 2006 to 2020, according to Statista . A little over 18 million Italians aged six and older attended weekly services in 2006, down to 12 million by 2020.

Italy has given rise to a number of architectural styles, including classical Roman, Renaissance, Baroque and Neoclassical. Italy is home to some of the most famous structures in the world, including the Colosseum and the Leaning Tower of Pisa . The concept of a basilica — which was originally used to describe an open public court building and evolved to mean a Catholic pilgrimage site — was born in Italy. The word, according to the Oxford Dictionary , is derived from Latin and meant "royal palace." The word is also from the Greek basilikē , which is the feminine of basilikos which means "royal" or basileus, which means "king."

Italy is also home to many castles, such as the Valle d'Aosta Fort Bard, the Verrès Castle and the Ussel Castle.

Florence, Venice and Rome are home to many museums, but art can be viewed in churches and public buildings. Most notable is the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel of the Vatican, painted by Michelangelo sometime between 1508 and 1512.

Italy has a "centuries-long operatic tradition," according to Carolyn Abbate and Roger Parker in " A History of Opera: The Last Four Hundred Years " (W. W. Norton & Company, 2015). Opera has its roots in Italy and many famous operas — including "Aida" and "La Traviata," both by Giuseppe Verdi, and "Pagliacci" by Ruggero Leoncavallo — were written in Italian and are still performed in the native language. More recently, Italian tenor Luciano Pavarotti made opera more accessible to the masses as a soloist and as part of the Three Tenors.

Italian cuisine has influenced food culture around the world and is viewed as a form of art by many. Wine, cheese and pasta are important parts of Italian meals. Pasta comes in a wide range of shapes, widths and lengths, including common forms such as penne, spaghetti, linguine, fusilli and lasagna.

For Italians, food isn't just nourishment, it is life. "Family gatherings are frequent and often centered around food and the extended networks of families," said Wagner.

"The etymologies of the Italian words for taste (sapore) and knowledge (sapere) suggest why we should, as scholars of Italy and Italian culture, attend to food," wrote Peter Naccarato, Zachary Nowak and Elgin K. Eckert in their book " Representing Italy Through Food " (Bloomsbury Academic, 2018)

No one area of Italy eats the same things as the next. Each region has its own spin on "Italian food," according to CNN . For example, most of the foods that Americans view as Italian, such pizza, come from central Italy. In the North of Italy, fish, potatoes, rice, sausages, pork and different types of cheeses are the most common ingredients. Pasta dishes with tomatoes are popular, as are many kinds of stuffed pasta, polenta and risotto. In the South, tomatoes dominate dishes, and they are either served fresh or cooked into sauce. Southern cuisine also includes capers, peppers, olives and olive oil, garlic, artichokes, eggplant and ricotta cheese.

Wine is also a big part of Italian culture, and the country is home to some of the world's most famous vineyards. The oldest traces of Italian wine were discovered in a cave near Sicily's southwest coast. "The archaeological implications of this new data are enormous, especially considering that the identification of wine [is] the first and earliest-attested presence of such a product in an archaeological context in Sicily," researchers wrote in the study, published online August 2017 in the Microchemical Journal .

Italy is home to a number of world-renowned fashion houses, including Armani, Gucci, Benetton, Versace and Prada and is a nation that takes dress very seriously. "In Sicily, they say 'Eat and drink according to your taste, dress according to other people’s tastes'," Emanuela Scarpellini, professor of modern history at the University of Milan wrote in her book " Italian Fashion since 1945 " (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

"As well-known as are the designers of Italian automobiles and household furnishings, they have not surpassed such designers of clothing and accessories as Gucci, Fendi, Kirzia, Ferragamo, Pucci, Valentino, Prada, Armani, Versace, Ferré, and Dolce and Gabbana," wrote Charles L. Killinger, author of " Culture and Customs of Italy " (Greenwood, 2005). He pinpointed the last decades of the 20th century as being the boom period for ready-to-wear fashion. This capped off a general trend of improvement for the fashion industry as it was bolstered by post-war funding from America.

Italy's official currency is the euro. Italians are known for their family-centric culture, and there are a number of small and mid-sized businesses. Even many of the larger companies such as Fiat and Benetton are still primarily controlled by single families. "Many families that immigrated from Italy are traditionalists by nature, with the parents holding traditional gender roles. This has become challenging for the younger generations, as gender roles have morphed in the American culture and today stand at odds with the father being the primary breadwinner and the undisputed head of the household and the mother being the primary caretaker of the home and children," said Wagner.

Meetings are typically less formal than in countries such as Germany and Russia, and the familial structure can give way to a bit of chaos and animated exchanges. Italian business people tend to view information from outsiders with a bit of wariness, and prefer verbal exchanges with people that they know well.

Italians celebrate most Christian holidays. The celebration of the Epiphany, celebrated on January 6, is much like Christmas. Belfana, an old lady who flies on her broomstick, delivers presents and goodies to good children, according to legend.

Pasquetta, on the Monday after Easter, typically involves family picnics to mark the beginning of springtime.

November 1 commemorates Saints Day , a religious holiday during which Italians typically decorate the graves of deceased relatives with flowers.

Many Italian towns and villages celebrate the feast day of their patron saint. September 19, for example, is the feast of San Gennaro, the patron saint of Napoli.

April 25 is the Liberation Day, marking the 1945 liberation ending World War II in Italy in 1945.

Additional reporting by Alina Bradford, Live Science Contributor

Before the Romans it was the Etruscans who appear to have dominated the Italian peninsula. Learn more by finding out how scientists solved the mystery of the Etruscans' origins .

More recently, Italy was at the forefront of the Covid-19 pandemic , but how early was the coronavirus really circulating in Italy? Find out in this report.

Italian Tourism Official Website

Discover Italy: The celebration of the Epiphany

Lonely Planet: Italy

Delish: Italian Food by Region

Italian National Institute of Statistics

" Focus On Italy " by Jen Green (Gareth Stevens Publishing, 2007)

"Languages Across Europe" BBC

" Portraits of the Italian Family: Past, Present and Future " by Gian Carlo Blangiardo and Stefania Rimoldi for the "Journal of Comparative Family Studies Vol. 45" (University of Toronto Press, 2014)

" A History of Opera: The Last Four Hundred Years " by Carolyn Abbate and Roger Parker (W. W. Norton & Company, 2015)

" Representing Italy Through Food " by Peter Naccarato, Zachary Nowak and Elgin K. Eckert (Bloomsbury Academic, 2018)

" Italian Fashion since 1945 " by Emanuela Scarpellini (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019)

" Culture and Customs of Italy " by Charles L. Killinger (Greenwood, 2005)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jonathan is the Editor of All About History magazine, running the day to day operations of the brand. He has a Bachelor's degree in History from the University of Leeds . He has previously worked as Editor of video game magazines games™ and X-ONE and tech magazines iCreate and Apps. He is currently based in Bournemouth, UK.

Why do babies rub their eyes when they're tired?

Why do people dissociate during traumatic events?

Immensely powerful 'magnetar' is emitting wobbly radio signals in our galaxy — and scientists can't explain them

Most Popular

By Anna Gora December 27, 2023

By Anna Gora December 26, 2023

By Anna Gora December 25, 2023

By Emily Cooke December 23, 2023

By Victoria Atkinson December 22, 2023

By Anna Gora December 16, 2023

By Anna Gora December 15, 2023

By Anna Gora November 09, 2023

By Donavyn Coffey November 06, 2023

By Anna Gora October 31, 2023

By Anna Gora October 26, 2023

- 2 Giant coyote killed in southern Michigan turns out to be a gray wolf — despite the species vanishing from region 100 years ago

- 3 When is the next total solar eclipse after 2024 in North America?

- 4 Neolithic women in Europe were tied up and buried alive in ritual sacrifices, study suggests

- 5 James Webb telescope confirms there is something seriously wrong with our understanding of the universe

- 2 No, you didn't see a solar flare during the total eclipse — but you may have seen something just as special

- 3 Pet fox with 'deep relationship with the hunter-gatherer society' buried 1,500 years ago in Argentina

- 4 Eclipse from space: See the moon's shadow race across North America at 1,500 mph in epic satellite footage

- 5 Superfast drone fitted with new 'rotating detonation rocket engine' approaches the speed of sound

Home — Essay Samples — Arts & Culture — Tradition — Overview Of The Main Features Of Italian Culture

Overview of The Main Features of Italian Culture

- Categories: Italy Tradition

About this sample

Words: 1008 |

Published: Jun 17, 2020

Words: 1008 | Pages: 2 | 6 min read

Works Cited

- Craveri, M. (2002). The culture of the Europeans. University of Chicago Press.

- Di Napoli, R., & Paparcone, M. (2017). The Italian Cultural Experience: A journey through the arts, humanities, and everyday life. Routledge.

- Gennari, D. J. (2019). The joy of writing about Italian-American food. In Pizza, Pasta, and Cannoli: Italian-American Food (pp. 3-22). Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

- Giuffrè, L. (2017). School education in Italy: An overview. Italian Journal of Sociology of Education, 9(2), 41-55.

- Ilardo, J. (2013). Culture and customs of Italy. ABC-CLIO.

- Leaman, O. (Ed.). (2010). The future of philosophy. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Lillich, M. (2019). How to eat like an Italian. National Geographic.

- Nava, M. (2017). L’Italia del made in Italy. Società e politica, (2), 117-124.

- Scuderi, A. (2018). Family ties and migration decisions: Italy in comparison with Europe. European Journal of Population, 34(4), 491-511.

- UNESCO. (2019). Festivals in Italy. Retrieved from https://ich.unesco.org/en/lists.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: Geography & Travel Arts & Culture

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1612 words

4 pages / 1747 words

2 pages / 826 words

1 pages / 435 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Tradition

Marriage has long been viewed as a cornerstone of society, embodying traditional values and serving as a sacred union between two individuals. Throughout history, the institution of marriage has been upheld as a symbol of [...]

Italy is a country with a rich cultural heritage and a long history of celebrating traditions and holidays. One of the most significant holidays in Italy is Easter, which holds immense religious and cultural significance for the [...]

Culture plays a crucial role in shaping our identities, beliefs, values, and behaviors. It is a powerful force that influences how we perceive the world around us and interact with others. In today's globalized world, where [...]

Taboos, often considered as social or cultural restrictions, play a significant role in shaping societies and individual behaviors. While taboos may vary across different cultures and contexts, their importance cannot be [...]

The Marrow of Tradition by Charles Waddell Chesnutt utilizes inequalities tied to the era of the American South where the Wellington Insurrection of 1898 occurred as a result of growing racial tensions coupled with the [...]

In Shirley Jackson's short story "The Lottery," the character of Old Man Warner is a fascinating study in tradition, superstition, and the fear of change. Old Man Warner serves as a symbol of the entrenched beliefs and customs [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

How Italy blends culture with cuisine - a photo essay

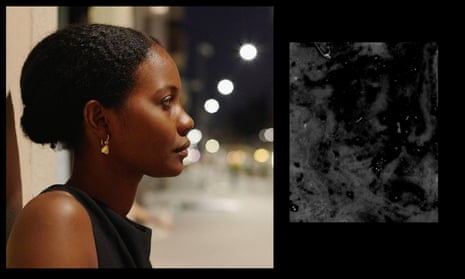

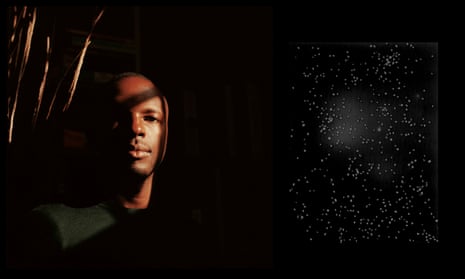

Photographer Harriet Zawedde was born in Rome but raised in the UK. Her series Nightshade, combines portraits with botanical images of the tomato plant and the subjects’ recipes

T he English word tomato derives from the Aztec word tomatl . It is believed the Aztecs and Incas were cultivating and eating the tomato from 700AD. Though the tomato originated from the Andean region, it eventually spread north to Mexico. The scientific name for the tomato is solanum lycoperscicum .

While the Spanish were responsible for bringing the tomato to Europe in the early 16th century, its first reference in Italy was in 1544 in Pietro Andrea Mattioli’s Herbal, who refers to the tomato as pomi d’oro meaning golden apple. The tomato was not used in cooking until the 18th century as it was often viewed with fear and suspicion as a member of the nightshade plant family, which had plants such as the mandrake among them.

Once the names the tomato were called were amended and confusion and ambiguity as to what it was subsided, it was able to illustrate its full potential. After its family ties became less relevant and it was allowed to exist for what it was, not how it looked, it thrived. This took an element of trust.

Below, Nightshade’s subjects discuss their favourite recipes.

I can tell you, lasagna is the first dish I learned to cook. I moved out from my parents’ house without knowing how to cook even a common pasta but since lasagna and pollo con patate, are my favourite dishes, I learned how to cook them first. Even though making the ragu isn’t so easy. I tried my best and my lasagna is one of the best in town, if you get in Brianza by any chance, you’ve got to taste it.

Evelyne’s lasagna Ingredients: Egg lasagna | Passata | Celery | Carrots | Onions | Mince | Parmesan | Olive oil | Homemade béchamel | Salt | Pepper | Basil Fry the onion until softened. Add the carrot and cook for five minutes, then add the celery and cook for another two minutes. Turn up the heat, add the chopped beef and cook until browned all over. Make a ragu over an afternoon, pour in the wine and passata, season with salt, pepper and a pinch of grated nutmeg, then bring to a simmer. Make your own béchamel. Place cooked ragu into an overproof dish and layer. Top with parmesan. Garnish with basil.

This is a classic Italian recipe. If you ever jump on a plane to Italy , don’t miss it.

Since I was a child, this has been my favourite recipe. I remember cooking it for every family party, even for my sister’s wedding. With this recipe you will never go too far wrong. Your guests will love Crostata. This recipe is a mix of authentic Italian flavours, in which lemon and marmellata (jam) are the main ingredients for a unique and refined taste.

Good luck and enjoy!

Claudia’s crostata alla marmellata Ingredients: 250g cold butter from the fridge | 200g of icing sugar | 500g of 00 flour | 2 eggs | The rind of an untreated lemon | 400g of jam | Enough milk to brush the surface | A pinch of salt Put the flour, butter and a pinch of salt in the mixer. Mix in order to obtain an uneven sandblasting. Add the eggs, icing sugar and lemon peel to flavour the pastry and allow the citric acid to make it crumbly. Knead the dough before putting it onto a work surface. Start working it with the fingertips, to create a nice compact dough. Wrap it in clingfilm and let it rest for 30 minutes in the fridge, or ideally overnight. After letting the dough rest, we heat it and flatten it. Aim for a thickness of 7/8mm. Transfer the dough into a 24cm diameter cake pan and pinch the bottom with a fork. Then we make our short pastry with jam, we distribute it on the edge. After that, prepare 3 or 4cm strips of dough and place on to the jam, applying pressure to the edges. Lay the strips diagonally creating a grid of pastry and diamond shapes of jam. To make the tart shiny, brush the milk on the pastry with a pastry brush. After that, we bake the tart in a pre-heated oven at 170C for 50 minutes.

Fiorentina is one of the most popular and biggest steak in Italian cuisine.

I have eaten this more than three times and its taste was undeniable. I think it is one of the best dishes that I often have because it reminds me of Tuscany’s fabulous and iconic lifestyle.

Simon’s fiorentina

Ingredients: T-bone steak | Salt | Pepper (coal fire) Use the highest quality steak, ideally Tuscan or Italian. Cook on an open fire if possible (on the embers of the grill). Rare or medium rare only. Garnish with salt and pepper.

Pizza has always been a reason to gather with my friends. Pizzerias were fancy enough for our student pockets. When my mum would make pizza at home, we were always very excited.

For me, it was nice to see the first generation of immigrants learning the Italian cooking as their way of integration.

Abigail’s pizza al prosciutto e funghi Ingredients: Semolina pizza dough | tablespoon olive oil | 2 cloves chopped garlic | 5 mushrooms thinly sliced | mozzarella cheese | 1 can tomatoes | chopped roma | 1 bell pepper| thinly sliced prosciutto | salt & pepper to taste | oregano | pepper flakes Preheat oven to its hottest setting for 45 minutes. With about 1 teaspoon olive oil, sauté the sliced mushrooms and a pinch of salt over medium heat for 5-10 minutes, until well browned. Set aside. Sprinkle semolina on your baking sheet. Place the dough on top of the semolina and roll out into a circular shape. Brush the outer edges with olive oil and chopped garlic. Spread chopped tomatoes from the centre out to the edge of the oiled crust. Evenly place your toppings (mushrooms, mozzarella, bell pepper, etc) on the dough. Sprinkle with salt, Italian seasoning and pepper flakes, to taste. Add Parmesan cheese if desired. Transfer the pizza onto your stone by sliding it off the baking sheet. Bake for 10+ minutes, or until the crust is nicely browned and the cheese is bubbly. Remove with tongs and let rest for five minutes.

I usually cook it during summer for lunch, after a long morning at the beach. It is easy, quick and everyone loves it, including my kids. The pepper is not that hot. It is a plate that I particularly love because I buy the shrimps fresh from the local fish store near the beach.

Nadege’s pasta con gamberoni, peperoncino e pangrattato Ingredients: Shrimps from Marsala Tomatoes from pachino | 300g spaghetti | Olive oil | Garlic | Hot pepper | Salt In a frying pan add some oil, garlic and hot pepper then mix all together until the mixture becomes a little golden. In the meantime, boil some water for the pasta. Add two or three tablespoons of the boiling water into the mixture. Then let it sit for a couple of minutes until the pasta is cooked. Add salt and pepper. Mix everything together.

Aubergines are my all-time favourite late summer/winter vegetable. This dish reminds me of childhood, having a family meal at a local tavola calda. It can be eaten as a standalone dish or as part of a secondo piatto. It’s one of the most unassuming yet deliciously hearty dishes. I’ve probably adulterated the dish to suit my palette but this is a firm favourite for me to prepare for my nearest and dearest. If you want a leaner version of this dish, try grilling the aubergines instead. An exceptionally tasty vegetarian treat.

Tiwonge’s melanzane alla parmigiana Ingredients: 3 large aubergines | 1 bottle of tomato passata | 2 cloves of garlic 2 balls of mozzarella | 1 cup of parmigiano reggiano (grated) | 1 cup of extra virgin olive oil | 1 cup flour | 1 cup vegetable oil | Black pepper to taste | Fresh basil to taste | Salt to taste Preheat oven to 180C (356F). Slice aubergines lengthways but leave skin on. Place in a bowl and sprinkle two tablespoons of salt over them and leave for an hour to remove the moisture. In the meantime prepare the sauce. Add two teaspoons of olive oil to a pan and finely chop garlic cloves. Fry until softened. Add passata and cook on medium heat on hob for 15 minutes. Tear and add fresh basil and black pepper and salt. Cook for a further 10 minutes. Chop mozzarella into small cubes. Place flour into a bowl. Take aubergines out of salt and coat each in the flour. Prepare a new pan with two tablespoons vegetable oil and fry off flour coated aubergines- about 1-2 minutes each side. Place on kitchen towel to absorb oil. Add more cooking oil to pan if required.Prepare an oven baking dish. Start by spoon- ing some of the passata onto the base. Then place a layer of aubergines on top, add some passata, parmesan and mozzarella. Repeat until all ingredients have been used. Bake for 25-30 minutes. Serve with a sprig of basil and enjoy this heart-warming beautiful dish.

This is a classic Italian antipasto. It is the perfect dish for when you invite your friend for dinner because it is easy to make and very tasty.

Bintou’s caprese Ingredients: Mozzarella | Tomato | Extra virgin olive oil | Oregano | Salt | Pepper Slice mozzarella and tomato and place on plate. Apply a generous amount of extra virgin olive oil. Season with salt, pepper and fresh oregano.

This dish reminds me of the long summers in my childhood, and I used to enjoy this on a picnic or by the beach. It brings memories of laughs, sun, water, running barefoot in the hot sand, beach games and the joy of eating all together.

Cinzia’s pomodori di riso alla romana Ingredients: 4-5 medium firm ripe round tomatoes seeded and hollowed out | 1 cup uncooked rice (I used long grain par boiled) 185 grams | 1 teaspoon oregano 1/2 gram | 1 teaspoon basil 1/2 gram | 1/2 teaspoon salt 2 1/2 grams | 1/2 gram *6 springs fresh chopped Italian parsley | 1 clove garlic chopped | 1/4 - 1/2 cup chopped tomato pulp 55-82 grams | 2-3 tablespoons olive oil Pre-heat oven to 180C (375F) and lightly oil a large baking pan. In a medium bowl add rice and cover with water, allowing it soak for one hour, then drain and rinse. Rinse and dry tomatoes, carefully cut off top of tomato and set aside. Remove seed and pulp from the tomatoes, set aside the pulp and discard the seeds. In a medium bowl mix chopped tomato pulp, oregano, salt, parsley, garlic, 2-3 tablespoons (45 grams) olive oil and rice. Fill hollowed out tomatoes with mixture. Place tops back on tomatoes, sprinkle tomatoes with a little salt and drizzle with olive oil. Add roasted potatoes with rosemary and bake for approximately 45- 60 minutes or until potatoes and rice are tender. Serve immediately. Enjoy.

This is my favourite dish for three reasons: though based on rather basic ingredients, it is unabashedly rich and indulgent; its reddish/orangey colours evoke those of my favourite team (AS Roma), and you can do an excellent version of it in under 30 minutes.

Joseph’s amatriciana

Ingredients: Guanciale (cured Italian pig cheek. Do not use pancetta in any circumstance) | Pecorino Romano (abundant) | Tomato passata Calabrian chili | Salt | Pepper | Rigatoni or bucatini | Wine Dice the guanciale into thin strips. Remember to remove the hard part of the skin, and to slice off a bit of fat if the ratio of meat to fat is less than 1:3. Add to a non-stick pan at medium heat and let it heat gently until the guanciale is crispy and the fat renders. Add a splash of dry white wine (like a frascati), to deglaze the pan. This step is optional. Once the alcohol has evaporated, add some flakes of chilli and a high-quality tomato passata (or blended chopped tomatoes). Add some seasoning (but not too much salt), and let it simmer on a medium heat. In the meantime, bring water to the boil, and add either rigatoni (short pasta) or bucatini, depending on your (and guests’) preference. Tip: growing up I was always told that the water of the pasta must be as salty as the Mediterranean. Few things are more upsetting than an under-salted pasta. So be generous when salting the boiling water for pasta. Two minutes before the pasta is ready, set aside some of the starchy boiling water, and then quickly decant and add to the sauce. Another tip: always toss pasta into sauce, not vice versa. The pasta is at its most absorbent in the 10 seconds after it has been drained, so don’t waste time in mixing it with the sauce. As you toss it in, add in generous heaps of grated pecorino cheese, which should gently melt. This renders the sauce less red but also thicker. Use the water set aside to regulate the consistency. A good amatriciana must have a touch of sleepiness to it. Plate - on a heated plate preferably, add some grated pecorino and buon appetito .

www.harrietfairbairn.com | @harrietoflondon

- The Guardian picture essay

- Italian food and drink

Italian academic cooks up controversy with claim carbonara is US dish

Tomato-free pizza on UK menus as chefs choke on the price of fruit and veg

The secret behind Britain’s top pasta chef’s winning dish? It’s gluten free and vegan

A local’s guide to Parma, Italy: city of cheese, ham and stunning baroque buildings

Italian researchers find new recipe to extend life of fresh pasta by a month

There’s more to spritz than Aperol

'Stop this madness': NYT angers Italians with 'smoky tomato carbonara' recipe

Italian or British? Writer solves riddle of spaghetti bolognese

Most viewed.

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Food and Language

Language of food activism in italy, slow food restaurant menu and dinner at officina gastronomica alle tamerici, conclusion: language and food activism, acknowledgments, food activism and language in a slow food italy restaurant menu.

Carole Counihan is professor emerita of anthropology at Millersville University and has been studying food, gender, culture, and activism in Italy and the United States for forty years. She has published several book chapters and journal articles and the following books: Italian Food Activism in Urban Sardinia (Bloomsbury 2019; Italian edition Rosenberg and Sellier 2020), A Tortilla Is Like Life: Food and Culture in the San Luis Valley of Colorado (Texas University Press 2009), Around the Tuscan Table: Food, Family and Gender in Twentieth-Century Florence (Routledge 2004), and The Anthropology of Food and Body (Routledge 1999). She is the co-editor of Food and Culture: A Reader (Routledge 1997, 2008, 2013, 2018), Taking Food Public (Routledge 2012), Food Activism (Bloomsbury 2014), and Making Taste Public: Ethnographies of Food and the Senses (Bloomsbury 2018). She is editor-in-chief of the scholarly journal Food and Foodways .

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Guest Access

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Carole Counihan; Food Activism and Language in a Slow Food Italy Restaurant Menu. Gastronomica 1 November 2021; 21 (4): 76–87. doi: https://doi.org/10.1525/gfc.2021.21.4.76

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

This essay explores how food activists in Italy purposely shape food and language to construct meaning and value. It is grounded in years of ethnographic fieldwork on food and culture in Italy and looks specifically at the Slow Food Movement. The essay explores language and food activism through a detailed unpacking of the text of a menu prepared for a restaurant dinner for delegates to the Slow Food National Chapter Assembly in 2009. The menu uses descriptive poetic language to construct an idealized folk cuisine steeped in local products, poverty, history, and peasant culinary traditions. As I explore the language of the menu and the messages communicated by the food, I ask if they intensify people’s activism, advance Slow Food’s goals of “good, clean and fair food,” and promote food democracy.

Food activists in Italy mutually shape food and language in the construction of meaning and value. Food and language intertwine in many ways and pointed language can shape new understandings of cuisine and culture. This essay uses the Italian Slow Food Movement as an example of food activism and considers its goals and tactics, particularly as they are conveyed through alimentary language. Food activism consists of “people’s efforts to promote social and economic justice by transforming food habits” ( Counihan 2019 : 1) and includes buying organic and Fairtrade products, frequenting farmers markets, establishing community gardens, organizing against pesticides or GMOs, maintaining quality product designations, supporting legislation, and so on. Overall, it pursues food democracy: “the vision of an ecologically sound, economically viable, and socially just system of food and agriculture” ( Hassanein 2003 : 84).

The essay examines the kind of food activism Slow Food promotes by performing a detailed exegesis of the menu of a restaurant dinner for delegates to the Slow Food National Chapter Assembly in 2009. It considers food not only as discourse created through the language of the menu but also as material substance on the plate, analyzing its symbolism in the context of Italian history and culture. The essay asks if the alimentary language of one menu in particular, and of food activism in general, can help produce the counter-hegemonic attitudes and behaviors fundamental to food system change.

Analysis of the menu reveals its construction of an idealized folk cuisine based on local, humble, tasty dishes grounded in historically important places and traditions. 1 Folk cuisine is similar to what pioneering folklorist Don Yoder called “folk cookery…traditional domestic cookery marked by regional variation” ( 2015 : 21). It includes “the foods themselves, their morphology, their preparation, their preservation, their social and psychological functions, and their ramifications into all other aspects of folk-culture.” For Italians, folk cuisine is cucina popolare , “popular cuisine, cuisine of the people,” or cucina povera , “humble cuisine, cuisine of poverty” ( Montanari 2001 ). 2 In Italy, folk cuisine has historically been rooted in the countryside and the peasant families who comprised the majority of the population for most of Italian history. Today folk cuisine is an idealized construct rather than daily fare. Since the 1930s, Italians have steadily abandoned peasant farming, and the percentage of the population employed in agriculture dropped from 47 percent in 1930 to 4 percent in 2008, where it remains today ( Pratt and Luetchford 2013 : 27). Since the 1980s, Italians have increasingly consumed processed, imported, and mass-produced foods in place of the locally raised foods of the past ( Vercelloni 2001 ).

The folk cuisine depicted in the Slow Food dinner menu accentuated three threads. First, it was local food, rooted in place, with the implication that locality was crucial to (although not synonymous with) quality and environmental sustainability. Second, folk cuisine was steeped in history and tradition, which generated pride but also a potential undercurrent of xenophobia. Third, it was a cuisine of poverty, born from scarcity, hunger, and inexpensive foods, which raised issues of access and equity. As I explore the language of the Slow Food dinner menu and the messages communicated by the food, I ask what kind of activism they promote and whether they advance Slow Food’s overriding goals of “good, clean and fair food”—“good: quality, flavorsome and healthy food; clean: production that does not harm the environment; fair: accessible prices for consumers and fair conditions and pay for producers.” 3

Founded in Italy in 1986, Slow Food is a global association claiming a million supporters and 100,000 dues-paying members in 160 countries organized into roughly 1,500 local chapters called “convivia” worldwide and condotte in Italy. 4 The association is an important player in Italy’s landscape of food activism, taking place alongside of and sometimes participating in other initiatives including community or school gardens, solidarity purchase groups, farmers markets, Fairtrade, farmworker organizing, and so on. Slow Food has grown beyond its early focus on good food to “becoming a legitimate actor in the political arenas of food production and consumption…climate change…energy and biodiversity” ( Siniscalchi 2018 : 186). Some adherents, such as twenty-six-year-old Riccardo Astolfi from Bologna, described its evolution from the “old soul” ( vecchia anima) to the “new soul” ( nuova anima ): “When I say the old soul, I refer to people who get together exclusively for hedonistic pleasure, for gourmet food for rich people. The new soul was born on the road to Terra Madre and is summarized…in the triad ‘good, clean and fair.’” Terra Madre is the biannual meeting Slow Food has held since 2004 for producers, consumers, chefs, and activists from all over the world, and within the association it represents the shift toward “eco-gastronomy” linking good food to environmentalism and labor justice. 5 The evolution from the old soul to the new soul has not been without conflicts and tensions, which members told me have often played out in the condotte .

All Slow Food members become part of a local chapter run by committees of member-volunteers with guidance from the central office in Bra, northwest Italy, the home of Carlo Petrini, one of the founders, longtime leader, and still in 2021, president of Slow Food International. Local chapters organize tastings and theme dinners around high-quality local products, support small-scale producers, establish school gardens and farmers markets, educate through Master of Food classes, establish “food communities” to protect high-quality endangered foods, and review restaurants for the best-selling Slow Food restaurant guide, Guida alle Osterie d’Italia . Membership is open to all for modest dues, 6 and participation in most events, like the “classic” Slow Food dinners, is open to both members and nonmembers and can become gateways to membership.

Slow Food has been both praised and criticized by those who have participated in and studied the association, but it is important to note that its approach and efficacy vary a great deal according to the commitment and abilities of its local chapter leaders and members. Some have called Slow Food elitist because of its sometimes pricey dinners and exclusionary notions of taste ( Chrzan 2004 ; Hayes-Conroy and Hayes-Conroy 2010 ; Paxson 2005 ). Others have accused the association of neglecting producers and failing to make more than minor changes to the food system because of inadequate or misguided efforts ( Brackett 2011 ; Lotti 2010 ; Simonetti 2012 ; West and Domingos 2012 ). Still others have praised it for introducing new ways of thinking about food to thousands around the globe and for building communities of consumers and producers to foster change ( Fontefrancesco 2018 ; Sassatelli and Davolio 2010 ; Siniscalchi 2018 ). Here I want to contribute to the literature on Slow Food by examining the role of language in fostering its goals.

My exploration of Italian food activism is grounded in years of residence and ethnographic research in different Italian locations over a span of forty-plus years. This essay focuses on data gathered during my ethnographic research on “Convivium Culture: Stories from the Slow Food Movement” in diverse regions of Italy in 2009. I studied the grassroots participation of Slow Food members in their local chapters. I did participant observation and informal interviews at Slow Food dinners, major events (Slow Fish and Terra Madre), tastings, farms, farmers markets, and the 2009 National Chapter Assembly. I recorded and transcribed thirty-eight semi-structured interviews in Italian and translated the excerpts used in this essay. I also cite some personal interviews I recorded with Slow Food members in Cagliari, Italy, in 2011 as part of a study of food activism in that city ( Counihan 2019 ).

Language can shape attitudes and behaviors surrounding food, and food itself speaks reams about culture, as Priscilla Parkhurst Ferguson demonstrated in her study of France. She claimed that “every cuisine is a code…” and “words sustain cuisine” ( 2004 : 9–10). Linguistic anthropologists have outlined four ways that food and language constitute each other: “language-through-food, language-about-food, language-around-food, and language-as-food” ( Riley and Cavanaugh 2017 ; Karrebæk, Sif, Riley, and Cavanaugh 2018 ). Here I want to look at “language-about-food” as presented in the menu, and “language-through-food”—the way the food itself conveyed messages at the accompanying dinner—to ask how these discourses shape food activism.

Food is a lot like language. According to Roland Barthes, food contains and manifests “a collective imagination” and “a certain mental framework” ( 2013 : 24)—just as language does ( Sapir 1921 ). Food is “a system of communication, a body of images, a protocol of usages, situations, and behavior” ( Barthes 2013 : 24). These were manifest in the dinner menu, the dishes, the ingredients, and the ways they were combined, arrayed, and consumed. Cuisine contains a “structure” (25) based on a grammar of constituent units—such as courses within meals and dishes within courses—visible in the restaurant menu analyzed here. Yet cuisine also undergoes constant improvisation and evolution, as does language. Moreover, food is characterized by “polysemia” (28). Its ability to hold multiple meanings—what Arjun Appadurai calls its “semiotic virtuosity”—enhances its communicative power ( 1981 : 494). Moreover, as Appadurai observes, food has the “capacity to mobilize strong emotions” (494), which makes it a particularly powerful agent of relationships not only of hierarchy and separation such as he found in Indian caste system food rules but also of equality and intimacy, such as those generated among Slow Food dinner participants ( Siniscalchi 2018 : 188).

Sociologist Donna Maurer showed how language can shape food choice in the case of tofu’s introduction into the United States ( 1996 : 62). Initially, consumers resisted it, but changes in the discourse about tofu altered their perceptions of its acceptability and taste. Such discourses constitute a mode of “framing,” a way of seeing and interpreting foodways; sociologists Alison Adams and Thomas Shriver show how alternative agro-food movement organizations use framing to further their goals by creating meaning and a socially shared ideology ( 2010 : 35). Similarly, the Slow Food dinner menu “framed” food and projected certain ideologies, which were enhanced by Italians’ exuberant interest in both food and language.

Only a few studies of restaurants concentrate specifically on interpreting the menus. One is Irina Mihalache’s analysis of museum restaurants’ deployment of themed menus associated with special exhibitions. She found that “the menu and the food are multisensorial ‘lessons’ in history and culture” ( 2016 : 319); that is, they frame and recount the world in a certain way. Menus, others have found, can shape people’s eating experience and “actual perception of flavor” ( Mac Con Iomaire 2009 : 212). On an artfully constructed menu, “each item of food sums up and transmits a situation; it constitutes an information; it signifies” ( Barthes 2013 : 24).

In Italy, people talk constantly about food, particularly at meals, ideal sites for food-language discussions ( Karrebæk et al. 2018 : 20). 7 Slow Food member Raimondo Mandis expressed a widely shared belief: “Put two Italians together around a table, wherever they are, in Singapore, Los Angeles, Alaska, wherever they are, these two Italians around a table within five minutes will have started talking about food” (personal interview 2011). In Italy, food, like language, is highly localized and strongly linked to community identity; this provides fodder for many animated discussions about whose version of any given dish or idiom is better and why.

Language has always been important in furthering Slow Food’s activist mission and captivating adherents. Although the founders are Italian, and Italian is the language of the central office in Bra, “Slow Food” is always in English, which is also the default language of the Slow Food International website at www.slowfood.com . This website points viewers to websites in seven other languages: Italian, French, Spanish, German, Portuguese, Russian, and Japanese. All have a page called “Slow Food terminology,” 8 which defines key terms like “good, clean, and fair food,” “convivium,” and “eco-gastronomy”—all critical to changing the way people think about food by providing new terms for new concepts and practices.

As early as 1989, Slow Food established its own publishing house, Slow Food Editore. 9 Its mission is to publish books and magazines about high-quality and endangered foods, to educate consumers, and to promote sustainable food systems and eco-gastronomy. In an interview in 2009, Roberto Burdese, then-president of Slow Food Italy, told me: “For an organization like Slow Food, which is yes, political, but which above all wants to educate and inform, it is important to have our own publishing house which serves not only to tell our own stories but also to publish books and texts that contribute to understanding the spirit of our project.”

Also important in establishing and propagating Slow Food’s linguistic framing of alimentary issues were its chapter, national, and international websites and social media activity announcing events and connecting regularly with existing and potential new members ( Frost and Laing 2013 ). Social media language has played an increasingly important part in food activism ( Goodman and Jaworsky 2020 ). In her master’s thesis, Carolyn Bender (2012) took a detailed look at Slow Food’s significant media presence and found that it fostered democratic knowledge sharing and communication between chapters and the central office. Connecting whether virtually or in person to debate Slow Food’s actions has been critical to the association’s mission. As member Noemi Franchi told me, “The best thing about Slow Food for me is the fact that you can really give everyone a chance to speak and that you can put people from diverse places in communication with each other” (personal interview 2009).

One opportunity for Slow Food members to get together and exchange ideas was the National Chapter Assembly ( assemblea nazionale delle condotte ), which I was able to attend in March 2009 in Fiumicino, Italy, a city of 80,000 in the region of Lazio near Rome (and site of Rome’s Leonardo da Vinci airport). About 500 delegates came from 300 chapters all over Italy to participate in two days of discussions about Slow Food’s status and future plans. The chapter assemblies were important occasions for debating change in the association, and the one I attended was abuzz with excitement. For the first time ever, large portions of the conference were allocated to five-minute speeches from any member who wished to speak, and many did. Men and women, young and old, from Italy’s diverse cities, towns, and regions spoke of chapter activities and concerns at several sessions during the two days.

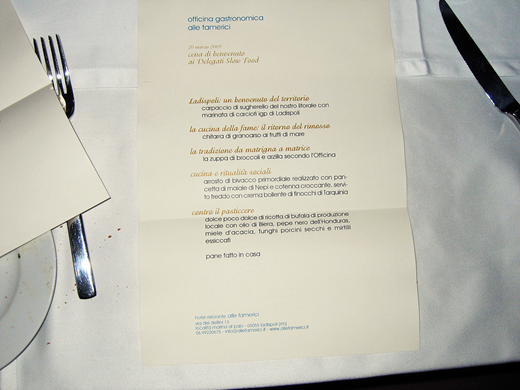

The conference activities began on Friday evening with delegates in regional groups dining at several restaurants in the Fiumicino area. I attended dinner with the Emilia-Romagna regional delegation at the restaurant Officina Gastronomica alle Tamerici (Gastronomic Workshop by the Tamarisks—hereafter Officina ). The restaurant’s name included “workshop” ( officina ), which highlighted the artisanal nature of the cookery, “gastronomic” ( gastronomica) , which accentuated skilled cooking and delicious food, and “tamarisks” ( tamerici ) or salt cedar trees, which emphasized locality, for they constituted a prominent species that thrived in the sandy salty soils of the littoral region.

I arrived from the conference hotel with a busload of hungry delegates at the Officina restaurant around 8:30 p.m. on a cool Friday, and each of us found a seat at one of several tables set for four to six people. I sat with a welcoming group that included one of my former students from the University of Gastronomic Sciences in Pollenzo, Italy. Tables were set with white tablecloths, simple silverware, and a menu at each diner’s place ( figure 1 ). People eagerly began studying their menu and chatting about the dishes while anticipating their tastiness.

Officina gastronomica alle tamerici menu.

Photograph by Carole Counihan © 2021

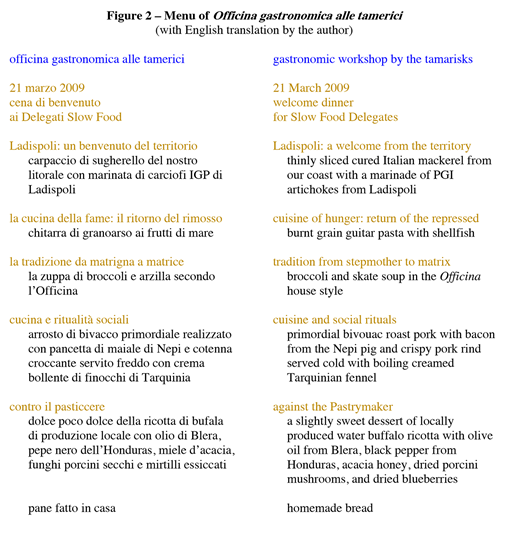

To uncover the Officina menu’s culinary signification of history and culture, I analyze it following one of the methods Jillian Cavanaugh and colleagues describe: “semiotic analysis of documents and media” ( 2014 : 93–94). This method examines how texts like the menu “describe and delimit the world around them” and “produce cultural and economic value for certain foods.” The transcribed menu in the original Italian is shown in figure 2 , with my English translation.

Transcribed Officina gastronomica alle tamerici menu with English translation.

The menu consisted of five “couplets,” representing five courses. The first line of each couplet was in gold letters and described a general context; the second line, in black print, slightly indented, described a dish. This dyadic structure was like call and response, a kind of poetry, a fact that recalls Elizabeth Andoh’s comment that, “translated literally, some Japanese restaurant menus could be mistaken for poetry” ( 2010 : 33). The Italian language of the Officina menu was rhythmic and alliterative—it rolled off the tongue with a mellifluous and pulsing cadence. Within the five couplets/courses, the dishes became longer and more elaborate as they went on, building to a crescendo in the dessert, and then ending with a final note of closure with the most basic food of all: homemade bread, pane fatto in casa .

The menu declared its overriding intent of “welcome” by using the word twice. In fact, the very first line of the menu declared the event a “welcome dinner” for the Slow Food delegates. The next line, describing the first course, then read: “Ladispoli: a welcome from the territory.” Welcome— benvenuto —was central to cultural practice everywhere in Italy and was often demonstrated through commensality ( Counihan 1984 ). On the menu, it had the double meaning of welcoming the Slow Food delegates from all over Italy to the conference, and also welcoming attendees to the specific place and cuisine of Lazio, the region in Central Italy where we were conferencing.

The menu stressed the importance of locality by mentioning several place names from Lazio: Ladispoli, Blera, Nepi, and Tarquinia. All had deep historical significance in ancient Roman and Etruscan times. Ladispoli was the site of the Etruscan port of Alsium near where we were dining, and Tarquinia’s famed Monterozzi necropolis was a Unesco World Heritage site. Renowned places like these, ubiquitous in Italy, were sources of patrimonial pride. The use of the word territorio in “Ladispoli: a welcome from the territory,” emphasized the centrality of local identity. Territorio was highly significant to many Italians and meant not only the land but also “meaningful place” imbued with local history, culture, and identity ( Counihan 2019 ).

In the first course, the food materialized the importance of locality in the “thinly sliced cured mackerel from our coast with a marinade of PGI artichokes from Ladispoli” ( figure 3 ). Use of the possessive “our” ( nostro ) laid claim to the mackerel, an inexpensive and tasty Mediterranean species integral to the traditional fishery. It was accompanied by a marinade of PGI artichokes from Ladispoli, the second mention of this important city. PGI—Protected Geographical Indication (IGP— Indicazione Geografica Protetta )—is an EU category recognizing excellent products linked to specific regions, like the artichokes in this dish ( Parasecoli 2014 : 253–254). The menu was full of foods clearly identified as local, and all three of its named vegetables—artichokes, broccoli, and fennel—were indigenous to the Mediterranean region. There were no products of the Columbian exchange commonly found in Italian cuisine such as tomatoes, green peppers, potatoes, and beans ( Guigoni 2009 ). Only in the very last course, dessert, did “black pepper from Honduras” appear. This was perhaps a quiet salute to the global origins of some important foods even in a context otherwise highlighting foods from the “territory,” from “our coast,” from “local production,” and from nearby famous sites of the venerated Etruscans and Romans.

Thinly sliced cured Italian mackerel from our shores with artichoke marinade.

Along with local products, the menu highlighted the cuisine of poverty at the heart of folk foodways. The first line of the second course/stanza was explicit—it read: “Cuisine of hunger: the return of the repressed.” This alluded to how hunger had been ubiquitous in the old days, but it was overcome and its memory “repressed” during the post–World War II Italian economic boom, marked by a rising standard of living, improved food security, abandonment of small-scale farming, and increased consumption of former luxury foods like meat. Nonetheless, the long history of dearth had shaped cuisines across Italy profoundly, and the inclusion of poverty foods at the Slow Food dinner materialized and memorialized this fact ( Capatti and Montanari 1999 ; Helstosky 2004 ).

The “cuisine of hunger” of the second course consisted of burnt grain “guitar” pasta with shellfish— chitarra di grano arso ai frutti di mare ( figure 4 ). Historically, mollusks and crustaceans, or frutti di mare (“fruits of the sea”), belonged to the cuisine of poverty because people gathered them for free, but today due to environmental degradation and overfishing, they have become scarce and costly. Burnt grain pasta was poor people’s food dating back perhaps to the eighteenth century. Scholarship is lacking, but media and cookbooks report that this pasta was made from burnt wheat gleaned by poor peasants—wheat scorched either by burning the stubble to clear the fields or by the hot threshing machines used in the harvest. 10 On the menu it appeared as “guitar” pasta, a spaghetti square in cross section rather than round, and typical of the Abruzzo region just east of Lazio. 11 Pasta made of burnt grain was once poor people’s food, cucina povera , and its consumption at a white tablecloth restaurant was a way to remember a past of scarcity and frugality. But it could also represent a transformation of that hunger food into a badge of distinction, and indeed burnt grain pasta has become chic and trendy ( Krader 2018 ). Its elevation in status by way of its heritage is similar to the “elite authenticity” Gwynne Mapes found in her analysis of New York Times food articles, which built distinction around qualities of “historicity” and “simplicity” among others ( 2018 ).

Burnt grain guitar pasta with shellfish.

The menu’s third course/stanza highlighted the enigmatic “tradition from stepmother to matrix.” Perhaps in the recipe, the stepmother represented new outside forces, contrasted with those belonging to matrix/ matrice connoting “mother,” “uterus,” and “origin, fundamental cause, inspiring element.” 12 This course emphasized the female influences on culinary traditions typical of folk cuisine, which originated in the domestic kitchen—both maternal, familial, foundational influences and new, external, “stepmother” ones. The stepmother/ matrigna is an anomalous figure in the family, wife to the husband but not mother to the children, occupying the mother space but not the real mother. Nadia Rosso reminds us of the long history in myth and literature of the cruel stepmother, la matrigna crudele , “the incarnation of the negative female stereotype,” renowned for her hostility to the husband’s children ( 2020 : 1–2). It is not clear how this image of the cruel stepmother might shape perception of the dish except perhaps to imply that some innovations are “cruel” and should be abandoned in favor of the “matrix” or original dish. The typical, local, humble dish of broccoli and skate soup 13 ( figure 5 ) underscored the ongoing imprint of tradition, here done in the style of the restaurant, Officina , which aligned with the matrix rather than the stepmother influences.

Broccoli and skate soup in the Officina house style.

The fourth course featured a fancier, meat-based, more prestigious dish—the long-named “primordial bivouac roast pork with bacon from the Nepi pig and crispy pork rind served cold with boiling creamed Tarquinian fennel” ( figure 6 ). For most of Italian history, meat was expensive, rarely eaten, and “a quintessential symbol of social prestige” ( Montanari 2001 : 4). Pork, however, was more accessible than beef because many peasant families raised a pig on scraps and forage, butchered it in late fall, and preserved the meat for the entire year, eventually eating every bit of it including muscle, lard, organs, feet, ears, and tail in various forms including boiled, fried, roasted, and preserved as salame, sausage, prosciutto, and head cheese (see Apergi and Bianco 1991 : 43–52). Roast pork was a prestigious cut appropriate to marking a festive occasion. The sauce of “boiling creamed Tarquinian fennel” adorning the sliced meat accentuated a renowned local vegetable. The allusion to “primordial” and “bivouac” signaled history, nature, the outdoors, and the wild, which were sometimes sites of festive meat consumption, for example at scampagnate , picnics in the countryside with friends ( Counihan 2004 : 125). The name of the course, “cuisine and social rituals,” underscored the importance of commensality to social relationships, widely acknowledged in Italy (117–138).

Primordial bivouac roast pork with Nepi bacon and crispy pork rind served cold with boiling creamed Tarquinian fennel.

The last course/stanza, dessert, had the somewhat ambiguous title contro il pasticcere —literally “in contrast to or against the pastry chef.” This was another celebration of humble foods, opposing them to fancy desserts made by trained confectioners. The dessert consisted of “locally produced water buffalo ricotta with olive oil from Blera, black pepper from Honduras, acacia honey, dried porcini mushrooms, and dried blueberries” ( figure 7 ). While the menu noted black pepper’s far-off origins, the rest of the ingredients were either explicitly local, such as the ricotta and Blera olive oil, or implicitly so, such as the honey, mushrooms, and blueberries, which were foraged wild foods and thus quintessentially part of folk cuisine ( Cucinotta and Pieroni 2018 ). The description of the dessert, dolce poco dolce , was a play on words, as dolce as an adjective means sweet, but as a noun it means a sweet or a dessert, hence the literal translation is “a slightly sweet sweet.” Ricotta, used in the dessert, was an inexpensive byproduct of cheese making and part of cucina popolare . After adding rennet to milk and making cheese from the curds, the leftover whey was “recooked” into “ricotta.” Its presence on the menu again gave attention to the frugality of folk cuisine, although the special occasion was marked by ricotta made from Italian water buffalo milk, prized for its higher fat content than regular cow’s milk ricotta.

A slightly sweet dessert of locally produced water buffalo ricotta with olive oil from Blera, black pepper from Honduras, acacia honey, dried porcini mushrooms, and dried blueberries.

The menu and meal spoke to and through the senses. The dishes were beautifully plated with a pleasing variety of colors, shapes, and forms: the red, orange, yellow, and beige of the carpaccio [ figure 3 ]; the dull gray-brown of the stringy burnt grain “guitar” pasta contrasting with the brilliant red-orange mussels in their shimmering black shells [ figure 4 ]; the yellow skate soup dotted with vibrant green specks of broccoli [ figure 5 ]. The meal appealed not only to the eyes but also to the other senses by displaying a variety of textures, temperatures, fragrances, and tastes: the chewy, dense, room temperature carpaccio ; the hot, liquid soup mingling the briny fragrance of skate with the earthy odor of broccoli; the firm dense room-temperature pork paired with the hot semi-liquid creamed fennel [ figure 6 ]; the smooth white buffalo ricotta lightly honey-sweetened, its silky melt-in-your mouth texture disrupted with crunchy bits of dried blueberries, dried mushrooms, and ground pepper [ figure 7 ]. The carefully orchestrated meal spoke through diverse sensory registers, which enriched the verbal message of the menu; food’s “materiality” and “discursivity” reinforced each other ( Mapes 2018 : 265).

As noted above, the menu ended with the most basic food of all, homemade bread, which accompanied the entire meal. Traditionally, bread constituted a large part of the diet of most Italians, especially peasants and workers ( Counihan 1984 , 2004 ; Teti 1976 ). But its home production and overall consumption have been waning since the mid–twentieth century as meat, sweets, and fats have played an ever-larger role in the diet ( Vercelloni 1998 , 2001 ; italiani.coop 2021 ). Placing homemade bread on the menu affirmed the importance of this traditional and highly localized comestible, which had for centuries been central to poor people’s diets and survival.

Some motifs observed in other forms of food activism were not evident in the Officina menu. For example, Michael Kideckel found themes of “anti-intellectualism” and “natural food” in his historical analysis of the language of US food activists since 1830 ( 2018 ). But neither were key to Slow Food or the dinner. On the contrary, Slow Food was quite intellectual—education about food and taste was central to its mission, and activities combined cognitive and sensory learning ( Counihan 2019 : ch. 2). In the Officina menu, “natural” was not in evidence, nor was “organic.” The dinner did not celebrate elite dishes— cucina ricca —or abundance, excess, gluttony, or waste ( Montanari 2001 ). Although the dinner included several courses, portions were small, the pace leisurely, and participants were able to consume every bite of each course. Absent in the menu were foreign or ethnic dishes, ingredients, or spices, with the exception of black pepper. This absence was a double-edged sword, creating space for forgotten local foods and their producers but closing off appreciation of foreign and ethnic cuisines and their immigrant purveyors.

Do activities like the menu and dinner strengthen participants’ commitment to food democracy? Such events are certainly fun, social, and full of good food and education about it, but do they develop critical consciousness? What sorts of activism do they promote? While in some situations, including some Slow Food dinners, food can be an instrument of class privilege and what Josée Johnston tellingly calls “bourgeois piggery,” she importantly emphasizes that “food also represents an entry point for political engagement” ( 2008 : 94). This was confirmed by Slow Food Cagliari member Carla Marcis, who stated, “Slow Food has enabled me to see food as a way of changing things” (personal interview 2011). Further, Johnston argues, because power is fragmented and ubiquitous, resistance must be pluralistic and continuous (2008: 95). Repeated quotidian acts of shopping and eating can entrench new ways of behaving and influence the economy and culture of food. Commensal events help develop new ways of thinking ( Marovelli 2019 ).