An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Med (Lausanne)

Rethinking clinical decision-making to improve clinical reasoning

Salvatore corrao.

1 Department of Internal Medicine, National Relevance and High Specialization Hospital Trust ARNAS Civico, Palermo, Italy

2 Dipartimento di Promozione della Salute Materno Infantile, Medicina Interna e Specialistica di Eccellenza “G. D’Alessandro” (PROMISE), University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy

Christiano Argano

Associated data.

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Improving clinical reasoning techniques is the right way to facilitate decision-making from prognostic, diagnostic, and therapeutic points of view. However, the process to do that is to fill knowledge gaps by studying and growing experience and knowing some cognitive aspects to raise the awareness of thinking mechanisms to avoid cognitive errors through correct educational training. This article examines clinical approaches and educational gaps in training medical students and young doctors. The authors explore the core elements of clinical reasoning, including metacognition, reasoning errors and cognitive biases, reasoning strategies, and ways to improve decision-making. The article addresses the dual-process theory of thought and the new Default Mode Network (DMN) theory. The reader may consider the article a first-level guide to deepen how to think and not what to think, knowing that this synthesis results from years of study and reasoning in clinical practice and educational settings.

Introduction

Clinical reasoning is based on complex and multifaceted cognitive processes, and the level of cognition is perhaps the most relevant factor that impacts the physician’s clinical reasoning. These topics have inspired considerable interest in the last years ( 1 , 2 ). According to Croskerry ( 3 ) and Croskerry and Norman ( 4 ), over 40 affective and cognitive biases may impact clinical reasoning. In addition, it should not be forgotten that both the processes and the subject matter are complex.

In medicine, there are thousands of known diagnoses, each with different complexity. Moreover, in line with Hammond’s view, a fundamental uncertainty will inevitably fail ( 5 ). Any mistake or failure in the diagnostic process leads to a delayed diagnosis, a misdiagnosis, or a missed diagnosis. The particular context in which a medical decision is made is highly relevant to the reasoning process and outcome ( 6 ).

More recently, there has been renewed interest in diagnostic reasoning, primarily diagnostic errors. Many researchers deepen inside the processes underpinning cognition, developing new universal reasoning and decision-making model: The Dual Process Theory.

This theory has a prompt implementation in medical decision-making and provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the gamma of theoretical approaches taken into consideration previously. This model has critical practical applications for medical decision-making and may be used as a model for teaching decision reasoning. Given this background, this manuscript must be considered a first-level guide to understanding how to think and not what to think, deepening clinical decision-making and providing tools for improving clinical reasoning.

Too much attention to the tip of the iceberg

The New England Journal of Medicine has recently published a fascinating article ( 7 ) in the “Perspective” section, whereon we must all reflect on it. The title is “At baseline” (the basic condition). Dr. Bergl, from the Department of Medicine of the Medical College of Wisconsin (Milwaukee), raised that his trainees no longer wonder about the underlying pathology but are focused solely on solving the acute problem. He wrote that, for many internal medicine teams, the question is not whether but to what extent we should juggle the treatment of critical health problems of patients with care for their coexisting chronic conditions. Doctors are under high pressure to discharge, and then they move patients to the next stage of treatment without questioning the reason that decompensated the clinical condition. Suppose the chronic condition or baseline was not the fundamental goal of our performance. In that case, our juggling is highly inconsistent because we are working on an intermediate outcome curing only the decompensation phase of a disease. Dr. Bergl raises another essential matter. Perhaps equally disturbing, by adopting a collective “base” mentality, we unintentionally create a group of doctors who prioritize productivity rather than developing critical skills and curiosity. We agree that empathy and patience are two other crucial elements in the training process of future internists. Nevertheless, how much do we stimulate all these qualities? Perhaps are not all part of cultural backgrounds necessary for a correct patient approach, the proper clinical reasoning, and balanced communication skills?

On the other hand, a chronic baseline condition is not always the real reason that justifies acute hospitalization. The lack of a careful approach to the baseline and clinical reasoning focused on the patient leads to this superficiality. We are focusing too much on our students’ practical skills and the amount of knowledge to learn. On the other hand, we do not teach how to think and the cognitive mechanisms of clinical reasoning.

Time to rethink the way of thinking and teaching courses

Back in 1910, John Dewey wrote in his book “How We Think” ( 8 ), “The aim of education should be to teach us rather how to think than what to think—rather improve our minds to enable us to think for ourselves than to load the memory with the thoughts of other men.”

Clinical reasoning concerns how to think and make the best decision-making process associated with the clinical practice ( 9 ). The core elements of clinical reasoning ( 10 ) can be summarized in:

- 1. Evidence-based skills,

- 2. Interpretation and use of diagnostic tests,

- 3. Understanding cognitive biases,

- 4. Human factors,

- 5. Metacognition (thinking about thinking), and

- 6. Patient-centered evidence-based medicine.

All these core elements are crucial for the best way of clinical reasoning. Each of them needs a correct learning path to be used in combination with developing the best thinking strategies ( Table 1 ). Reasoning strategies allow us to combine and synthesize diverse data into one or more diagnostic hypotheses, make the complex trade-off between the benefits and risks of tests and treatments, and formulate plans for patient management ( 10 ).

Set of some reasoning strategies (view the text for explanations).

However, among the abovementioned core element of clinical reasoning, two are often missing in the learning paths of students and trainees: metacognition and understanding cognitive biases.

Metacognition

We have to recall cognitive psychology, which investigates human thinking and describes how the human brain has two distinct mental processes that influence reasoning and decision-making. The first form of cognition is an ancient mechanism of thought shared with other animals where speed is more important than accuracy. In this case, thinking is characterized by a fast, intuitive way that uses pattern recognition and automated processes. The second one is a product of evolution, particularly in human beings, indicated by an analytical and hypothetical-deductive slow, controlled, but highly consuming way of thinking. Today, the psychology of thinking calls this idea “the dual-process theory of thought” ( 11 – 14 ). The Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences awardee Daniel Kahneman has extensively studied the dichotomy between the two modes of thought, calling them fast and slow thinking. “System 1” is fast, instinctive, and emotional; “System 2” is slower, more deliberative, and more logical ( 15 ). Different cerebral zones are involved: “System 1” includes the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, the pregenual medial prefrontal cortex, and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex; “System 2” encompasses the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Glucose utilization is massive when System 2 is performing ( 16 ). System 1 is the leading way of thought used. None could live permanently in a deliberate, slow, effortful way. Driving a car, eating, and performing many activities over time become automatic and subconscious.

A recent brilliant review of Gronchi and Giovannelli ( 17 ) explores those things. Typically, when a mental effort is required for tasks requiring attention, every individual is subject to a phenomenon called “ego-depletion.” When forced to do something, each one has fewer cognitive resources available to activate slow thinking and thus is less able to exert self-control ( 18 , 19 ). In the same way, much clinical decision-making becomes intuitive rather than analytical, a phenomenon strongly affected by individual differences ( 20 , 21 ). Experimental evidence by functional magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography studies supports that the “resting state” is spontaneously active during periods of “passivity” ( 22 – 25 ). The brain regions involved include the medial prefrontal cortex, the posterior cingulate cortex, the inferior parietal lobule, the lateral temporal cortex, the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex, and the hippocampal formation ( 26 ). Findings reporting high-metabolic activity in these regions at rest ( 27 ) constituted the first clear evidence of a cohesive default mode in the brain ( 28 ), leading to the widely acknowledged introduction of the Default Mode Network (DMN) concept. The DMN contains the medial prefrontal cortex, the posterior cingulate cortex, the inferior parietal lobule, the lateral temporal cortex, the dorsal medial prefrontal cortex, and the hippocampal formation. Lower activity levels characterize the DMN during goal-directed cognition and higher activity levels when an individual is awake and involved in the mental processes requiring low externally directed attention. All that is the neural basis of spontaneous cognition ( 26 ) that is responsible for thinking using internal representations. This paradigm is growing the idea of stimulus-independent thoughts (SITs), defined by Buckner et al. ( 26 ) as “thoughts about something other than events originating from the environment” that is covert and not directed toward the performance of a specific task. Very recently, the role of the DMN was highlighted in automatic behavior (the rapid selection of a response to a particular and predictable context) ( 29 ), as opposed to controlled decision making, suggesting that the DMN plays a role in the autopilot mode of brain functioning.

In light of these premises, everyone can pause to analyze what he is doing, improving self-control to avoid “ego-depletion.” Thus, one can actively switch between one type of thinking and the other. The ability to make this switch makes the physician more performing. In addition, a physician can be trained to understand the ways of thinking and which type of thinking is engaged in various situations. This way, experience and methodology knowledge can energize Systems 1 and 2 and how they interact, avoiding cognitive errors. Figure 1 summarizes all the concepts abovementioned about the Dual Mode Network and its relationship with the DMN.

Graphical representation of the characteristics of Dual Mode Network, including the relationship between the two systems by Default Mode Network (view the text for explanations).

Emotional intelligence is another crucial factor in boosting clinical reasoning for the best decision-making applied to a single patient. Emotional intelligence recognizes one’s emotions. Those others label different feelings appropriately and use emotional information to guide thinking and behavior, adjust emotions, and create empathy, adapt to environments, and achieve goals ( 30 ). According to the phenomenological account of Fuchs, bodily perception (proprioception) has a crucial role in understanding others ( 31 ). In this sense, the proprioceptive skills of a physician can help his empathic understanding become elementary for empathy and communication with the patient. In line with Fuchs’ view, empathic understanding encompasses a bodily resonance and mediates contextual knowledge about the patient. For medical education, empathy should help to relativize the singular experience, helping to prevent that own position becomes exclusive, bringing oneself out of the center of one’s own perspective.

Reasoning errors and cognitive biases

Errors in reasoning play a significant role in diagnostic errors and may compromise patient safety and quality of care. A recently published review by Norman et al. ( 32 ) examined clinical reasoning errors and how to avoid them. To simplify this complex issue, almost five types of diagnostic errors can be recognized: no-fault errors, system errors, errors due to the knowledge gap, errors due to misinterpretation, and cognitive biases ( 9 ). Apart from the first type of error, which is due to unavoidable errors due to various factors, we want to mention cognitive biases. They may occur at any stage of the reasoning process and may be linked to intuition and analytical systems. The most frequent cognitive biases in medicine are anchoring, confirmation bias, premature closure, search satisficing, posterior probability error, outcome bias, and commission bias ( 33 ). Anchoring is characterized by latching onto a particular aspect at the initial consultation, and then one refuses to change one’s mind about the importance of the later stages of reasoning. Confirmation bias ignores the evidence against an initial diagnosis. Premature closure leads to a misleading diagnosis by stopping the diagnostic process before all the information has been gathered or verified. Search satisficing blinds other additional diagnoses once the first diagnosis is made posterior probability error shortcuts to the usual patient diagnosis for previously recognized clinical presentations. Outcome bias impinges on our desire for a particular outcome that alters our judgment (e.g., a surgeon blaming sepsis on pneumonia rather than an anastomotic leak). Finally, commission bias is the tendency toward action rather than inaction, assuming that only good can come from doing something (rather than “watching and waiting”). These biases are only representative of the other types, and biases often work together. For example, in overconfidence bias (the tendency to believe we know more than we do), too much faith is placed in opinion instead of gathered evidence. This bias can be augmented by the anchoring effect or availability bias (when things are at the forefront of your mind because you have seen several cases recently or have been studying that condition in particular), and finally by commission bias—with disastrous results.

Novice vs. expert approaches

The reasoning strategies used by novices are different from those used by experts ( 34 ). Experts can usually gather beneficial information with highly effective problem-solving strategies. Heuristics are commonly, and most often successfully, used. The expert has a saved bank of illness scripts to compare and contrast the current case using more often type 1 thinking with much better results than the novice. Novices have little experience with their problems, do not have time to build a bank of illness scripts, and have no memories of previous similar cases and actions in such cases. Therefore, their mind search strategies will be weak, slow, and ponderous. Heuristics are poor and more often unsuccessful. They will consider a more comprehensive range of diagnostic possibilities and take longer to select approaches to discriminate among them. A novice needs specific knowledge and specific experience to become an expert. In our opinion, he also needs special training in the different ways of thinking. It is possible to study patterns, per se as well. It is, therefore, likely to guide the growth of knowledge for both fast thinking and slow one.

Moreover, learning by osmosis has traditionally been the method to move the novice toward expert capabilities by gradually gaining experience while observing experts’ reasoning. However, it seems likely that explicit teaching of clinical reasoning could make this process quicker and more effective. In this sense, an increased need for training and clinical knowledge along with the skill to apply the acquired knowledge is necessary. Students should learn disease pathophysiology, treatment concepts, and interdisciplinary team communication developing clinical decision-making through case-series-derived knowledge combining associative and procedural learning processes such as “Vienna Summer School on Oncology” ( 35 ).

Moreover, a refinement of the training of communicative skills is needed. Improving communication skills training for medical students and physicians should be the university’s primary goal. In fact, adequate communication leads to a correct diagnosis with 76% accuracy ( 36 ). The main challenge for students and physicians is the ability to respond to patients’ individual needs in an empathic and appreciated way. In this regard, it should be helpful to apply qualitative studies through the adoption of a semi-structured or structured interview using face-to-face in-depth interviews and e-learning platforms which can foster interdisciplinary learning by developing expertise for the clinical reasoning and decision-making in each area and integrating them. They could be effective tools to develop clinical reasoning and decision-making competencies and acquire effective communication skills to manage the relationship with patient ( 37 – 40 ).

Clinical reasoning ways

Clinical reasoning is complex: it often requires different mental processes operating simultaneously during the same clinical encounter and other procedures for different situations. The dual-process theory describes how humans have two distinct approaches to decision-making ( 41 ). When one uses heuristics, fast-thinking (system 1) is used ( 42 ). However, complex cases need slow analytical thinking or both systems involved ( 15 , 43 , 44 ). Slow thinking can use different ways of reasoning: deductive, hypothetic-deductive, inductive, abductive, probabilistic, rule-based/categorical/deterministic, and causal reasoning ( 9 ). We think that abductive and causal reasoning need further explanation. Abductive reasoning is necessary when no deductive argument (from general assumption to particular conclusion) nor inductive (the opposite of deduction) may be claimed.

In the real world, we often face a situation where we have information and move backward to the likely cause. We ask ourselves, what is the most plausible answer? What theory best explains this information? Abduction is just a process of choosing the hypothesis that would best explain the available evidence. On the other hand, causal reasoning uses knowledge of medical sciences to provide additional diagnostic information. For example, in a patient with dyspnea, if considering heart failure as a casual diagnosis, a raised BNP would be expected, and a dilated vena cava yet. Other diagnostic possibilities must be considered in the absence of these confirmatory findings (e.g., pneumonia). Causal reasoning does not produce hypotheses but is typically used to confirm or refute theories generated using other reasoning strategies.

Hypothesis generation and modification using deduction, induction/abduction, rule-based, causal reasoning, or mental shortcuts (heuristics and rule of thumbs) is the cognitive process for making a diagnosis ( 9 ). Clinicians develop a hypothesis, which may be specific or general, relating a particular situation to knowledge and experience. This process is referred to as generating a differential diagnosis. The process we use to produce a differential diagnosis from memory is unclear. The hypotheses chosen may be based on likelihood but might also reflect the need to rule out the worst-case scenario, even if the probability should always be considered.

Given the complexity of the involved process, there are numerous causes for failure in clinical reasoning. These can occur in any reasoning and at any stage in the process ( 33 ). We must be aware of subconscious errors in our thinking processes. Cognitive biases are subconscious deviations in judgment leading to perceptual distortion, inaccurate assessment, and misleading interpretation. From an evolutionary point of view, they have developed because, often, speed is more important than accuracy. Biases occur due to information processing heuristics, the brain’s limited capacity to process information, social influence, and emotional and moral motivations.

Heuristics are mind shortcuts and are not all bad. They refer to experience-based techniques for decision-making. Sometimes they may lead to cognitive biases (see above). They are also essential for mental processes, expressed by expert intuition that plays a vital role in clinical practice. Intuition is a heuristic that derives from a natural and direct outgrowth of experiences that are unconsciously linked to form patterns. Pattern recognition is just a quick shortcut commonly used by experts. Alternatively, we can create patterns by studying differently and adequately in a notional way that accumulates information. The heuristic that rules out the worst-case scenario is a forcing mind function that commits the clinician to consider the worst possible illness that might explain a particular clinical presentation and take steps to ensure it has been effectively excluded. The heuristic that considers the least probable diagnoses is a helpful approach to uncommon clinical pictures and thinking about and searching for a rare unrecognized condition. Clinical guidelines, scores, and decision rules function as externally constructed heuristics, usually to ensure the best evidence for the diagnosis and treatment of patients.

Hence, heuristics are helpful mind shortcuts, but the exact mechanisms may lead to errors. Fast-and-frugal tree and take-the-best heuristic are two formal models for deciding on the uncertainty domain ( 45 ).

In the recent times, clinicians have faced dramatic changes in the pattern of patients acutely admitted to hospital wards. Patients become older and older with comorbidities, rare diseases are frequent as a whole ( 46 ), new technologies are growing in a logarithmic way, and sustainability of the healthcare system is an increasingly important problem. In addition, uncommon clinical pictures represent a challenge for clinicians ( 47 – 50 ). In our opinion, it is time to claim clinical reasoning as a crucial way to deal with all complex matters. At first, we must ask ourselves if we have lost the teachings of ancient masters. Second, we have to rethink medical school courses and training ones. In this way, cognitive debiasing is needed to become a well-calibrated clinician. Fundamental tools are the comprehensive knowledge of nature and the extent of biases other than studying cognitive processes, including the interaction between fast and slow thinking. Cognitive debiasing requires the development of good mindware and the awareness that one debiasing strategy will not work for all biases. Finally, debiasing is generally a complicated process and requires lifelong maintenance.

We must remember that medicine is an art that operates in the field of science and must be able to cope with uncertainty. Managing uncertainty is the skill we have to develop against an excess of confidence that can lead to error. Sound clinical reasoning is directly linked to patient safety and quality of care.

Data availability statement

Author contributions.

SC and CA drafted the work and revised it critically. Both authors have approved the submission of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Critical thinking: what it is and why it counts. 2020. https://tinyurl.com/ybz73bnx (accessed 27 April 2021)

Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine. Curriculum for training for advanced critical care practitioners: syllabus (part III). version 1.1. 2018. https://www.ficm.ac.uk/accps/curriculum (accessed 27 April 2021)

Guerrero AP. Mechanistic case diagramming: a tool for problem-based learning. Acad Med.. 2001; 76:(4)385-9 https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200104000-00020

Harasym PH, Tsai TC, Hemmati P. Current trends in developing medical students' critical thinking abilities. Kaohsiung J Med Sci.. 2008; 24:(7)341-55 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1607-551X(08)70131-1

Hayes MM, Chatterjee S, Schwartzstein RM. Critical thinking in critical care: five strategies to improve teaching and learning in the intensive care unit. Ann Am Thorac Soc.. 2017; 14:(4)569-575 https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201612-1009AS

Health Education England. Multi-professional framework for advanced clinical practice in England. 2017. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/multi-professionalframeworkforadvancedclinicalpracticeinengland.pdf (accessed 27 April 2021)

Health Education England, NHS England/NHS Improvement, Skills for Health. Core capabilities framework for advanced clinical practice (nurses) working in general practice/primary care in England. 2020. https://www.skillsforhealth.org.uk/images/services/cstf/ACP%20Primary%20Care%20Nurse%20Fwk%202020.pdf (accessed 27 April 2021)

Health Education England. Advanced practice mental health curriculum and capabilities framework. 2020. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/AP-MH%20Curriculum%20and%20Capabilities%20Framework%201.2.pdf (accessed 27 April 2021)

Jacob E, Duffield C, Jacob D. A protocol for the development of a critical thinking assessment tool for nurses using a Delphi technique. J Adv Nurs.. 2017; 73:(8)1982-1988 https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13306

Kohn MA. Understanding evidence-based diagnosis. Diagnosis (Berl).. 2014; 1:(1)39-42 https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2013-0003

Clinical reasoning—a guide to improving teaching and practice. 2012. https://www.racgp.org.au/afp/201201/45593

McGee S. Evidence-based physical diagnosis, 4th edn. Philadelphia PA: Elsevier; 2018

Norman GR, Monteiro SD, Sherbino J, Ilgen JS, Schmidt HG, Mamede S. The causes of errors in clinical reasoning: cognitive biases, knowledge deficits, and dual process thinking. Acad Med.. 2017; 92:(1)23-30 https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001421

Papp KK, Huang GC, Lauzon Clabo LM Milestones of critical thinking: a developmental model for medicine and nursing. Acad Med.. 2014; 89:(5)715-20 https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000000220

Rencic J, Lambert WT, Schuwirth L., Durning SJ. Clinical reasoning performance assessment: using situated cognition theory as a conceptual framework. Diagnosis.. 2020; 7:(3)177-179 https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0051

Examining critical thinking skills in family medicine residents. 2016. https://www.stfm.org/FamilyMedicine/Vol48Issue2/Ross121

Royal College of Emergency Medicine. Emergency care advanced clinical practitioner—curriculum and assessment, adult and paediatric. version 2.0. 2019. https://tinyurl.com/eps3p37r (accessed 27 April 2021)

Young ME, Thomas A, Lubarsky S. Mapping clinical reasoning literature across the health professions: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ.. 2020; 20 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02012-9

Advanced practice: critical thinking and clinical reasoning

Sadie Diamond-Fox

Senior Lecturer in Advanced Critical Care Practice, Northumbria University, Advanced Critical Care Practitioner, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, and Co-Lead, Advanced Critical/Clinical Care Practitioners Academic Network (ACCPAN)

View articles

Advanced Critical Care Practitioner, South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

Clinical reasoning is a multi-faceted and complex construct, the understanding of which has emerged from multiple fields outside of healthcare literature, primarily the psychological and behavioural sciences. The application of clinical reasoning is central to the advanced non-medical practitioner (ANMP) role, as complex patient caseloads with undifferentiated and undiagnosed diseases are now a regular feature in healthcare practice. This article explores some of the key concepts and terminology that have evolved over the last four decades and have led to our modern day understanding of this topic. It also considers how clinical reasoning is vital for improving evidence-based diagnosis and subsequent effective care planning. A comprehensive guide to applying diagnostic reasoning on a body systems basis will be explored later in this series.

The Multi-professional Framework for Advanced Clinical Practice highlights clinical reasoning as one of the core clinical capabilities for advanced clinical practice in England ( Health Education England (HEE), 2017 ). This is also identified in other specialist core capability frameworks and training syllabuses for advanced clinical practitioner (ACP) roles ( Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine, 2018 ; Royal College of Emergency Medicine, 2019 ; HEE, 2020 ; HEE et al, 2020 ).

Rencic et al (2020) defined clinical reasoning as ‘a complex ability, requiring both declarative and procedural knowledge, such as physical examination and communication skills’. A plethora of literature exists surrounding this topic, with a recent systematic review identifying 625 papers, spanning 47 years, across the health professions ( Young et al, 2020 ). A diverse range of terms are used to refer to clinical reasoning within the healthcare literature ( Table 1 ), which can make defining their influence on their use within the clinical practice and educational arenas somewhat challenging.

The concept of clinical reasoning has changed dramatically over the past four decades. What was once thought to be a process-dependent task is now considered to present a more dynamic state of practice, which is affected by ‘complex, non-linear interactions between the clinician, patient, and the environment’ ( Rencic et al, 2020 ).

Cognitive and meta-cognitive processes

As detailed in the table, multiple themes surrounding the cognitive and meta-cognitive processes that underpin clinical reasoning have been identified. Central to these processes is the practice of critical thinking. Much like the definition of clinical reasoning, there is also diversity with regard to definitions and conceptualisation of critical thinking in the healthcare setting. Facione (2020) described critical thinking as ‘purposeful reflective judgement’ that consists of six discrete cognitive skills: analysis, inference, interpretation, explanation, synthesis and self–regulation. Ross et al (2016) identified that critical thinking positively correlates with academic success, professionalism, clinical decision-making, wider reasoning and problem-solving capabilities. Jacob et al (2017) also identified that patient outcomes and safety are directly linked to critical thinking skills.

Harasym et al (2008) listed nine discrete cognitive steps that may be applied to the process of critical thinking, which integrates both cognitive and meta-cognitive processes:

- Gather relevant information

- Formulate clearly defined questions and problems

- Evaluate relevant information

- Utilise and interpret abstract ideas effectively

- Infer well-reasoned conclusions and solutions

- Pilot outcomes against relevant criteria and standards

- Use alternative thought processes if needed

- Consider all assumptions, implications, and practical consequences

- Communicate effectively with others to solve complex problems.

There are a number of widely used strategies to develop critical thinking and evidence-based diagnosis. These include simulated problem-based learning platforms, high-fidelity simulation scenarios, case-based discussion forums, reflective journals as part of continuing professional development (CPD) portfolios and journal clubs.

Dual process theory and cognitive bias in diagnostic reasoning

A lack of understanding of the interrelationship between critical thinking and clinical reasoning can result in cognitive bias, which can in turn lead to diagnostic errors ( Hayes et al, 2017 ). Embedded within our understanding of how diagnostic errors occur is dual process theory—system 1 and system 2 thinking. The characteristics of these are described in Table 2 . Although much of the literature in this area regards dual process theory as a valid representation of clinical reasoning, the exact causes of diagnostic errors remain unclear and require further research ( Norman et al, 2017 ). The most effective way in which to teach critical thinking skills in healthcare education also remains unclear; however, Hayes et al (2017) proposed five strategies, based on well-known educational theory and principles, that they have found to be effective for teaching and learning critical thinking within the ‘high-octane’ and ‘high-stakes’ environment of the intensive care unit ( Table 3 ). This is arguably a setting that does not always present an ideal environment for learning given its fast pace and constant sensory stimulation. However, it may be argued that if a model has proven to be effective in this setting, it could be extrapolated to other busy clinical environments and may even provide a useful aide memoire for self-assessment and reflective practices.

Integrating the clinical reasoning process into the clinical consultation

Linn et al (2012) described the clinical consultation as ‘the practical embodiment of the clinical reasoning process by which data are gathered, considered, challenged and integrated to form a diagnosis that can lead to appropriate management’. The application of the previously mentioned psychological and behavioural science theories is intertwined throughout the clinical consultation via the following discrete processes:

- The clinical history generates an initial hypothesis regarding diagnosis, and said hypothesis is then tested through skilled and specific questioning

- The clinician formulates a primary diagnosis and differential diagnoses in order of likelihood

- Physical examination is carried out, aimed at gathering further data necessary to confirm or refute the hypotheses

- A selection of appropriate investigations, using an evidence-based approach, may be ordered to gather additional data

- The clinician (in partnership with the patient) then implements a targeted and rationalised management plan, based on best-available clinical evidence.

Linn et al (2012) also provided a very useful framework of how the above methods can be applied when teaching consultation with a focus on clinical reasoning (see Table 4 ). This framework may also prove useful to those new to the process of undertaking the clinical consultation process.

Evidence-based diagnosis and diagnostic accuracy

The principles of clinical reasoning are embedded within the practices of formulating an evidence-based diagnosis (EBD). According to Kohn (2014) EBD quantifies the probability of the presence of a disease through the use of diagnostic tests. He described three pertinent questions to consider in this respect:

- ‘How likely is the patient to have a particular disease?’

- ‘How good is this test for the disease in question?’

- ‘Is the test worth performing to guide treatment?’

EBD gives a statistical discriminatory weighting to update the probability of a disease to either support or refute the working and differential diagnoses, which can then determine the appropriate course of further diagnostic testing and treatments.

Diagnostic accuracy refers to how positive or negative findings change the probability of the presence of disease. In order to understand diagnostic accuracy, we must begin to understand the underlying principles and related statistical calculations concerning sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV) and likelihood ratios.

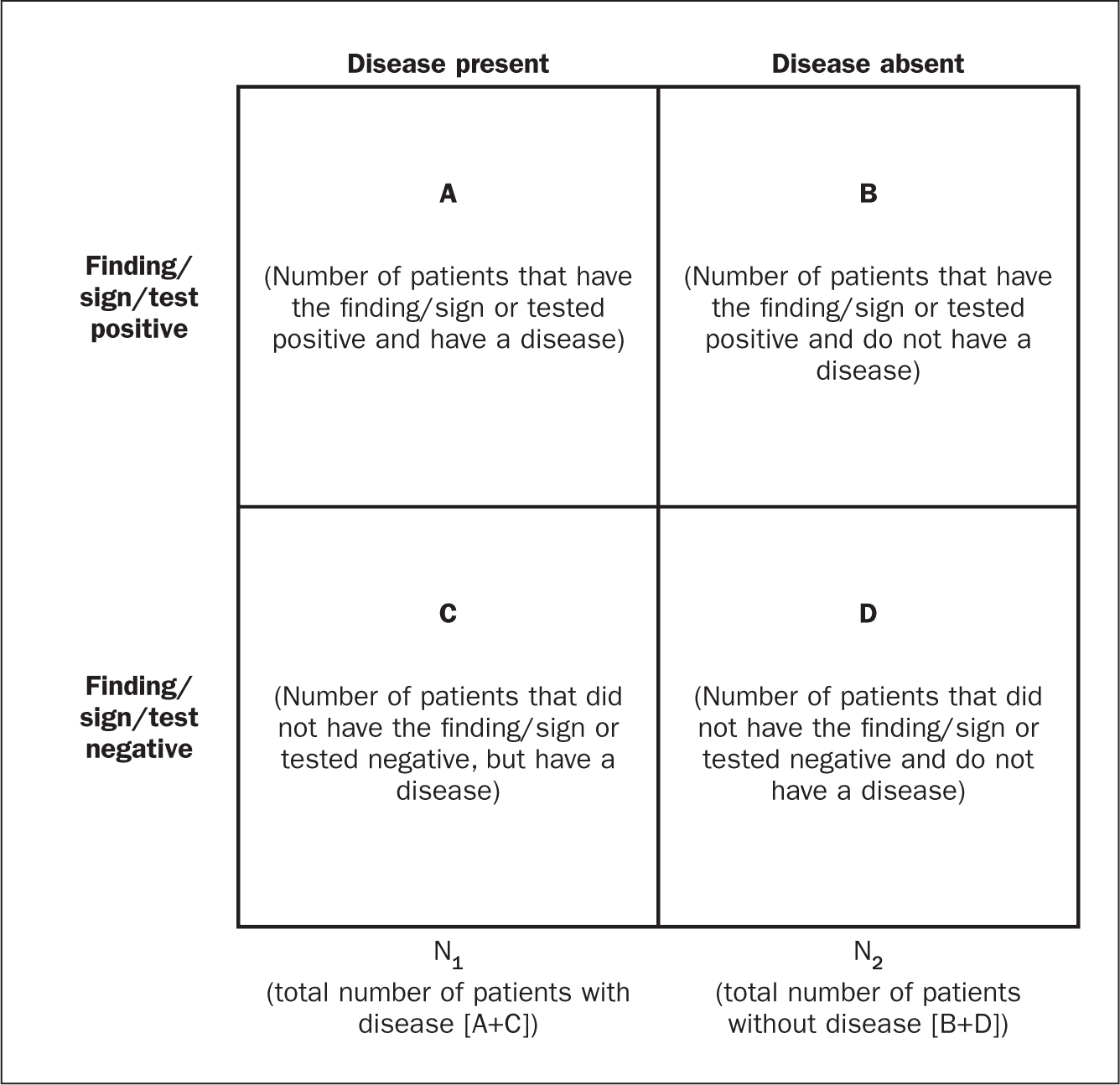

The construction of a two-by-two square (2 x 2) table ( Figure 1 ) allows the calculation of several statistical weightings for pertinent points of the history-taking exercise, a finding/sign on physical examination, or a test result. From this construct we can then determine the aforementioned statistical calculations as follows ( McGee, 2018 ):

- Sensitivity , the proportion of patients with the diagnosis who have the physical sign or a positive test result = A ÷ (A + C)

- Specificity , the proportion of patients without the diagnosis who lack the physical sign or have a negative test result = D ÷ (B + D)

- Positive predictive value , the proportion of patients with disease who have a physical sign divided by the proportion of patients without disease who also have the same sign = A ÷ (A + B)

- Negative predictive value , proportion of patients with disease lacking a physical sign divided by the proportion of patients without disease also lacking the sign = D ÷ (C + D)

- Likelihood ratio , a finding/sign/test results sensitivity divided by the false-positive rate. A test of no value has an LR of 1. Therefore the test would have no impact upon the patient's odds of disease

- Positive likelihood ratio = proportion of patients with disease who have a positive finding/sign/test, divided by proportion of patients without disease who have a positive finding/sign/test OR (A ÷ N1) ÷ (B÷ N2), or sensitivity ÷ (1 – specificity) The more positive an LR (the further above 1), the more the finding/sign/test result raises a patient's probability of disease. Thresholds of ≥ 4 are often considered to be significant when focusing a clinician's interest on the most pertinent positive findings, clinical signs or tests

- Negative likelihood ratio = proportion of patients with disease who have a negative finding/sign/test result, divided by the proportion of patients without disease who have a positive finding/sign/test OR (C ÷ N1) ÷ (D÷N1) or (1 – sensitivity) ÷ specificity The more negative an LR (the closer to 0), the more the finding/sign/test result lowers a patient's probability of disease. Thresholds <0.4 are often considered to be significant when focusing clinician's interest on the most pertinent negative findings, clinical signs or tests.

There are various online statistical calculators that can aid in the above calculations, such as the BMJ Best Practice statistical calculators, which may used as a guide (https://bestpractice.bmj.com/info/toolkit/ebm-toolbox/statistics-calculators/).

Clinical scoring systems

Evidence-based literature supports the practice of determining clinical pretest probability of certain diseases prior to proceeding with a diagnostic test. There are numerous validated pretest clinical scoring systems and clinical prediction tools that can be used in this context and accessed via various online platforms such as MDCalc (https://www.mdcalc.com/#all). Such clinical prediction tools include:

- 4Ts score for heparin-induced thrombocytopenia

- ABCD² score for transient ischaemic attack (TIA)

- CHADS₂ score for atrial fibrillation stroke risk

- Aortic Dissection Detection Risk Score (ADD-RS).

Conclusions

Critical thinking and clinical reasoning are fundamental skills of the advanced non-medical practitioner (ANMP) role. They are complex processes and require an array of underpinning knowledge of not only the clinical sciences, but also psychological and behavioural science theories. There are multiple constructs to guide these processes, not all of which will be suitable for the vast array of specialist areas in which ANMPs practice. There are multiple opportunities throughout the clinical consultation process in which ANMPs can employ the principles of critical thinking and clinical reasoning in order to improve patient outcomes. There are also multiple online toolkits that may be used to guide the ANMP in this complex process.

- Much like consultation and clinical assessment, the process of the application of clinical reasoning was once seen as solely the duty of a doctor, however the advanced non-medical practitioner (ANMP) role crosses those traditional boundaries

- Critical thinking and clinical reasoning are fundamental skills of the ANMP role

- The processes underlying clinical reasoning are complex and require an array of underpinning knowledge of not only the clinical sciences, but also psychological and behavioural science theories

- Through the use of the principles underlying critical thinking and clinical reasoning, there is potential to make a significant contribution to diagnostic accuracy, treatment options and overall patient outcomes

CPD reflective questions

- What assessment instruments exist for the measurement of cognitive bias?

- Think of an example of when cognitive bias may have impacted on your own clinical reasoning and decision making

- What resources exist to aid you in developing into the ‘advanced critical thinker’?

- What resources exist to aid you in understanding the statistical terminology surrounding evidence-based diagnosis?

- Update librarian

Key Features

New features.

Very good book, engaging, good use of figures and diagrams. Good application to practice - I will also be adding this to an International Health Assessment reading list.

This is a fantastic update from previous versions giving good scenarios for the students to work through. It includes all the relevant theories of clinical decision making and relates this to up to date practice.

Personally I love the practical approach and as such, it should be of use to my students. It couldn't be a core text though as the module is speciality specific, but I expect students to develop critical thinking and clinical reasoning within the module and they need ideas of ways to do this. Thank you for writing this text.

An excellent book used by other staff members and students. Very helpful when teaching communication and interpersonal skills

An exceptionally well written book, that related to all Healthcare professionals not just Nursing Students - the aspects on critical thinking has been central to the course

This year I was able to use a few chapters of the book to develop the basics of nursing course for English students.

Please verify your email.

We've sent you an email. Please follow the link to reset your password.

You can now close this window.

Edits have been made. Are you sure you want to exit without saving your changes?

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.3: Critical Thinking and Clinical Reasoning

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 63335

- Ernstmeyer & Christman (Eds.)

- Chippewa Valley Technical College via OpenRN

Before learning how to use the nursing process, it is important to understand some basic concepts related to critical thinking and nursing practice. Let’s take a deeper look at how nurses think.

Critical Thinking and Clinical Reasoning

Nurses make decisions while providing patient care by using critical thinking and clinical reasoning. Critical thinking is a broad term used in nursing that includes “reasoning about clinical issues such as teamwork, collaboration, and streamlining workflow.” [1] Using critical thinking means that nurses take extra steps to maintain patient safety and don’t just “follow orders.” It also means the accuracy of patient information is validated and plans for caring for patients are based on their needs, current clinical practice, and research.

“Critical thinkers” possess certain attitudes that foster rational thinking. These attitudes are as follows:

- Independence of thought: Thinking on your own

- Fair-mindedness: Treating every viewpoint in an unbiased, unprejudiced way

- Insight into egocentricity and sociocentricity: Thinking of the greater good and not just thinking of yourself. Knowing when you are thinking of yourself (egocentricity) and when you are thinking or acting for the greater good (sociocentricity)

- Intellectual humility: Recognizing your intellectual limitations and abilities

- Nonjudgmental: Using professional ethical standards and not basing your judgments on your own personal or moral standards

- Integrity: Being honest and demonstrating strong moral principles

- Perseverance: Persisting in doing something despite it being difficult

- Confidence: Believing in yourself to complete a task or activity

- Interest in exploring thoughts and feelings: Wanting to explore different ways of knowing

- Curiosity: Asking “why” and wanting to know more

Clinical reasoning is defined as, “A complex cognitive process that uses formal and informal thinking strategies to gather and analyze patient information, evaluate the significance of this information, and weigh alternative actions.” To make sound judgments about patient care, nurses must generate alternatives, weigh them against the evidence, and choose the best course of action. The ability to clinically reason develops over time and is based on knowledge and experience. [3]

The ANA’s Standards of Professional Nursing Practice associated with each component of the nursing process are described below.

Assessment is the first step of the nursing process. The American Nurses Association (ANA) “Assessment” Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse collects pertinent data and information relative to the health care consumer’s health or the situation.” This includes collecting “pertinent data related to the health and quality of life in a systematic, ongoing manner, with compassion and respect for the wholeness, inherent dignity, worth, and unique attributes of every person, including but not limited to, demographics, environmental and occupational exposures, social determinants of health, health disparities, physical, functional, psychosocial, emotional, cognitive, spiritual/transpersonal, sexual, sociocultural, age-related, environmental, and lifestyle/economic assessments.” [1]

A registered nurse uses a systematic method to collect and analyze patient data. Assessment includes physiological data, as well as psychological, sociocultural, spiritual, economic, and lifestyle data. For example, a nurse’s assessment of a hospitalized patient in pain includes the patient’s response to pain, such as the inability to get out of bed, refusal to eat, withdrawal from family members, or anger directed at hospital staff. Nurses assess patients to gather clues, make generalizations, and diagnose human responses to health conditions and life processes. Patient data is considered either subjective or objective, and it can be collected from multiple sources.

The “Diagnosis” Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse analyzes the assessment data to determine actual or potential diagnoses, problems, and issues.” [13] A nursing diagnosis is the nurse’s clinical judgment about the client's response to actual or potential health conditions or needs. Nursing diagnoses are the bases for the nurse’s care plan and are different than medical diagnoses.

Outcomes Identification

The “Outcomes Identification” Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse identifies expected outcomes for a plan individualized to the health care consumer or the situation.” The nurse sets measurable and achievable short- and long-term goals and specific outcomes in collaboration with the patient based on their assessment data and nursing diagnoses.

The “Planning” Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse develops a collaborative plan encompassing strategies to achieve expected outcomes.” [16] Assessment data, diagnoses, and goals are used to select evidence-based nursing interventions customized to each patient’s needs and concerns. Goals, expected outcomes, and nursing interventions are documented in the patient’s nursing care plan so that nurses, as well as other health professionals, have access to it for continuity of care. [17]

Nursing Care Plans

Creating nursing care plans is a part of the “Planning” step of the nursing process. A nursing care plan is a type of documentation that demonstrates the individualized planning and delivery of nursing care for each specific patient using the nursing process. Registered nurses (RNs) create nursing care plans so that the care provided to the patient across shifts is consistent among health care personnel.

Implementation

The “Implementation” Standard of Practice is defined as, “The nurse implements the identified plan.” Nursing interventions are implemented or delegated with supervision according to the care plan to assure continuity of care across multiple nurses and health professionals caring for the patient. Interventions are also documented in the patient’s electronic medical record as they are completed.

The “Evaluation” Standard of Practice is defined as, “The registered nurse evaluates progress toward attainment of goals and outcomes.” During evaluation, nurses assess the patient and compare the findings against the initial assessment to determine the effectiveness of the interventions and overall nursing care plan. Both the patient’s status and the effectiveness of the nursing care must be continuously evaluated and modified as needed.

Benefits of Using the Nursing Process

Using the nursing process has many benefits for nurses, patients, and other members of the health care team. The benefits of using the nursing process include the following:

- Promotes quality patient care

- Decreases omissions and duplications

- Provides a guide for all staff involved to provide consistent and responsive care

- Encourages collaborative management of a patient’s health care problems

- Improves patient safety

- Improves patient satisfaction

- Identifies a patient’s goals and strategies to attain them

- Increases the likelihood of achieving positive patient outcomes

- Saves time, energy, and frustration by creating a care plan or path to follow

By using these components of the nursing process as a critical thinking model, nurses plan interventions customized to the patient’s needs, plan outcomes and interventions, and determine whether those actions are effective in meeting the patient’s needs. In the remaining sections of this chapter, we will take an in-depth look at each of these components of the nursing process. Using the nursing process and implementing evidence-based practices are referred to as the “science of nursing.” Let’s review concepts related to the “art of nursing” while providing holistic care in a caring manner using the nursing process.

Holistic Nursing Care

The American Nurses Association (ANA) recently updated the definition of nursing as, “Nursing integrates the art and science of caring and focuses on the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and human functioning; prevention of illness and injury; facilitation of healing; and alleviation of suffering through compassionate presence. Nursing is the diagnosis and treatment of human responses and advocacy in the care of individuals, families, groups, communities, and populations in the recognition of the connection of all humanity.”

The ANA further describes nursing is a learned profession built on a core body of knowledge that integrates both the art and science of nursing. The art of nursing is defined as, “Unconditionally accepting the humanity of others, respecting their need for dignity and worth, while providing compassionate, comforting care.”

Nurses care for individuals holistically, including their emotional, spiritual, psychosocial, cultural, and physical needs. They consider problems, issues, and needs that the person experiences as a part of a family and a community as they use the nursing process.

Caring and the Nursing Process

The American Nurses Association (ANA) states, “The act of caring is foundational to the practice of nursing.” Successful use of the nursing process requires the development of a care relationship with the patient. A care relationship is a mutual relationship that requires the development of trust between both parties. This trust is often referred to as the development of rapport and underlies the art of nursing. While establishing a caring relationship, the whole person is assessed, including the individual’s beliefs, values, and attitudes, while also acknowledging the vulnerability and dignity of the patient and family. Assessing and caring for the whole person takes into account the physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual aspects of being a human being. Caring interventions can be demonstrated in simple gestures such as active listening, making eye contact, touching, and verbal reassurances while also respecting and being sensitive to the care recipient’s cultural beliefs and meanings associated with caring behaviors.

- Klenke-Borgmann, L., Cantrell, M. A., & Mariani, B. (2020). Nurse educator’s guide to clinical judgment: A review of conceptualization, measurement, and development. Nursing Education Perspectives, 41 (4), 215-221. ↵

- Powers, L., Pagel, J., & Herron, E. (2020). Nurse preceptors and new graduate success. American Nurse Journal, 15 (7), 37-39. ↵

- “ The Detective ” by paurian is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- “ In the Quiet Zone… ” by C.O.D. Library is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 ↵

- NCSBN. (n.d.). NCSBN clinical judgment model . https://www.ncsbn.org/14798.htm ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- “ The Nursing Process ” by Kim Ernstmeyer at Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- “Patient Image in LTC.JPG” by ARISE project is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- American Nurses Association. (n.d.). The nursing process. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/workforce/what-is-nursing/the-nursing-process/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (n.d.). The nursing process . https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/workforce/what-is-nursing/the-nursing-process/ ↵

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Nursing: Scope and standards of practice (3rd ed.). American Nurses Association. ↵

- American Nurses Association. (n.d.) The nursing process. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/workforce/what-is-nursing/the-nursing-process / ↵

- American Nurses Association. (n.d.). The nursing process. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/workforce/what-is-nursing/the-nursing-process / ↵

- Walivaara, B., Savenstedt, S., & Axelsson, K. (2013). Caring relationships in home-based nursing care - registered nurses’ experiences. The Open Journal of Nursing, 7 , 89-95. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3722540/pdf/TONURSJ-7-89.pdf ↵

- “ hospice-1793998_1280.jpg ” by truthseeker08 is licensed under CC0 ↵

- Watson Caring Science Institute. (n.d.). Watson Caring Science Institute. Jean Watson, PHD, RN, AHN-BC, FAAN, (LL-AAN) . https://www.watsoncaringscience.org/jean-bio/ ↵

Assessment Strategies Used by Nurse Educators To Evaluate Critical Thinking, Clinical Judgment or Clinical Reasoning In Undergraduate Nursing Students In Clinical Settings: A Scoping Review of The Literature

Affiliations.

- 1 Professor, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Faculty of Health, Community & Education, Mount Royal University. Adjunct Associate Professor, Faculty of nursing, University of Calgary, Acute Care Nurse Practitioner Medical Cardiology, Coronary Care Unit - Rockyview General Hospital, 4825 Mount Royal Gate S.W. Calgary, AB T3E 6K6 [email protected].

- 2 Associate Professor, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Mount Royal University, Room Y352, 4825 Mount Royal Gate, Calgary, AB T3E 6K6.

- 3 Registered Nurse, Alberta Health Services, Internal Medicine/ Medical Teaching Unit.

- PMID: 35292560

- DOI: 10.1891/RTNP-2021-0027

Background: Nursing students in Canada are typically enrolled in a four-year bachelor degree program that provides students with the necessary skills and knowledge to enter a highly demanding and challenging workforce. Strong critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and clinical judgment skills are essential skills for safe nursing practice. Therefore, educational institutes and their mentors are mandated to teach and assess these skills. In addition, nursing programs operate under an apprenticeship model, which entails the fulfillment of practical experience during which students are expected to develop and refine their skills in critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and clinical judgment.

Purpose: The purpose of this scoping review of the literature is to assess the available evidence of how higher-level thinking, including critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and clinical judgment are evaluated in undergraduate nursing students in clinical settings.

Methods: The inclusion criteria consisted of quantitative research articles published in the last 10 years. Search databases accessed included CINAHL Plus (EBSCO), Medline, and PubMed.

Results: Seven articles that fit the inclusion criteria became the focus of this scoping review. Four tools to evaluate higher-thinking processes in clinical settings were located and scrutinized: Lasater Clinical Judgment Rubric (LCJR), Script Concordance Testing, and Yoon's Critical Thinking Disposition Instrument. Relevance to practice : The scoping review will provide direction and contextualize future studies that focus on the appraisal of nursing students' critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and clinical judgment in clinical settings.

Keywords: and clinical judgment; clinical reasoning; critical thinking; scoping review.

© Copyright 2022 Springer Publishing Company, LLC.

- Search Search Search …

- Search Search …

Clinical Reasoning and Critical Thinking

There are a number of ways to evaluate problems we face on a daily basis, but in the medical field no two are more important than clinical reasoning and critical thinking. Here’s everything you need to know about the two, why they are used, and how they are interconnected.

Clinical reasoning is a cognitive process applied by nurses, clinicians, and other health professionals to analyze a clinical case, evaluate data, and prescribe a treatment plan. Critical thinking is the capability to analyze data and form a judgement on the basis of that information.

As you might recognize, clinical reasoning and critical thinking go hand in hand when evaluating information and creating treatment plans based on the available data. The depth of these two thinking methods goes far beyond mere analysis, however, and the rest of this article will define the two and dive into how clinical reasoning and critical thinking are used.

What Is Clinical Reasoning?

Believe it or not, there’s no agreed-upon definition for the term clinical reasoning, yet it’s widely used and well understood in the medical field. This phenomenon is likely due to the fact that clinical thinking is an offshoot of critical thinking that is applied to the treatment of patients.

The role of nurses, doctors, clinicians, and health professionals is often multifaceted, taking into account numerous sources of information in order to evaluate the patient’s condition, develop a course of treatment, and monitor that course of treatment for success.

Of course, clinical reasoning also relies heavily on prior cases, which themselves probably relied on some degree of clinical reasoning. That data is evaluated, and the patient’s health care professionals will assess whether more data needs to be gathered before making a decision about the treatment plan.

This process can be broken up into three general steps, although it’s important to reiterate that “clinical reasoning” doesn’t have a definite process that clinicians must follow; rather, it’s a mindset that is part and parcel of a patient-centric mentality.

Evaluating Data

Applying clinical reasoning starts with a fairly simple premise. If the patient comes in complaining of a headache, then some of the most logical causes a nurse or clinician might consider would be stress, a migraine, or certain infections.

This prompts them to ask more questions to evaluate the data further. Where is the headache located? Does the headache occur in relation to a particular event? Are there any other symptoms the patient is experiencing?

The answers to these questions can help narrow down the patient’s condition thanks to the historical precedents for and research on headaches and their underlying causes. At the very least, evaluating the data that the patient provides in light of prior cases is beneficial to eliminating the possibility of certain conditions.

Gathering More Data

Based on this initial information provided by the patient and gathered by physician tools, the physician can use this representation of the problem to guide the process.

Based on that initial information, the physician might be confident enough to prescribe a course of treatment based on a wealth of prior knowledge and information.

In other cases, however, more data needs to be gathered, and the physician will use clinical reasoning to repeat the information gathering process until they obtain a level of confidence that allows them to move forward with treatment.

Based on the information, the physician might issue a final diagnosis or suggest management actions to help the patient recover.

Taking Action

After the clinician has evaluated the information to the degree that they are confident making a diagnosis of the patient’s ailment, they can then evaluate the right course of treatment.

Is this an illness that can be treated with rest and an OTC medicine? Will surgery be required? Does the intensity of the illness warrant a higher dosage?

These questions, broad as they may be, are informed by the information gathering process to create an accurate picture of the problem and develop a solution. Again, that solution can be behavior modification, treatment, or a combination of both.

At this point, a physician should also manage the recovery process. Is the treatment working as expected? Are there any complications? How might we manage any complications that do arise?

If clinical reasoning as a whole seems particularly broad, it’s probably because it is. At its core, clinical reasoning is just the judgement of a healthcare professional to make accurate diagnoses, initiate treatment, and improve the patient’s condition.

How Are Clinical Reasoning and Critical Thinking Linked?

Clinical reasoning is a form of critical thinking that is applied to the medical field. Critical thinking skills help physicians evaluate credible information and assess alternative solutions, all of which is geared towards the question: how can I help the patient recover?

Critical thinking is an important skill for making judgement based on a rational, objective, and impartial thought process. It’s important in research, academic pursuits, and, obviously, clinical reasoning.

Physicians and clinicians, for example, apply their clinical reasoning skills to evaluate what treatments have the best success rate, how different factors of the patient’s condition can affect their recovery, and how alternative treatment methods might be used to improve the patient’s recovery process.

In particular, these health care professionals are evaluating the relevancy of information, the source of that information, and how that information can be used to better the treatment of patients in the future.

A systematic approach to clinical reasoning is a core aspect of critical thinking and crucial to the success of clinical judgement. A lapse in judgement or poor clinical reasoning can be harmful, costly, and extremely impactful on the patient’s wellbeing, which is likely why solid clinical reasoning is such a valuable skill in the world of medicine.

Final Thoughts

Clinical reasoning is a skill that you will develop in your years of schooling when entering the medical field, and the process of gathering information, evaluating information, and developing a course of treatment is strongly linked to the skill of critical thinking.

You may also like

Critical thinking jokes

Critical thinking can make life smoother and smarter, solving all kinds of academic, professional and everyday problems. But it’s not something you […]

The Psychology Behind Critical Thinking: Understanding the Mental Processes Involved

Critical thinking is an essential skill that enables individuals to analyze, evaluate, and interpret information effectively. It is a cognitive process that […]

The Role of Intuition in Critical Thinking: Unraveling the Connection

Intuition plays a significant role in the process of critical thinking. As an innate ability, intuition allows individuals to make decisions and […]

Critical Thinking Models: A Comprehensive Guide for Effective Decision Making

Critical thinking models are valuable frameworks that help individuals develop and enhance their critical thinking skills. These models provide a structured approach […]

A Crash Course in Critical Thinking

What you need to know—and read—about one of the essential skills needed today..

Posted April 8, 2024 | Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

- In research for "A More Beautiful Question," I did a deep dive into the current crisis in critical thinking.

- Many people may think of themselves as critical thinkers, but they actually are not.

- Here is a series of questions you can ask yourself to try to ensure that you are thinking critically.

Conspiracy theories. Inability to distinguish facts from falsehoods. Widespread confusion about who and what to believe.

These are some of the hallmarks of the current crisis in critical thinking—which just might be the issue of our times. Because if people aren’t willing or able to think critically as they choose potential leaders, they’re apt to choose bad ones. And if they can’t judge whether the information they’re receiving is sound, they may follow faulty advice while ignoring recommendations that are science-based and solid (and perhaps life-saving).

Moreover, as a society, if we can’t think critically about the many serious challenges we face, it becomes more difficult to agree on what those challenges are—much less solve them.

On a personal level, critical thinking can enable you to make better everyday decisions. It can help you make sense of an increasingly complex and confusing world.

In the new expanded edition of my book A More Beautiful Question ( AMBQ ), I took a deep dive into critical thinking. Here are a few key things I learned.

First off, before you can get better at critical thinking, you should understand what it is. It’s not just about being a skeptic. When thinking critically, we are thoughtfully reasoning, evaluating, and making decisions based on evidence and logic. And—perhaps most important—while doing this, a critical thinker always strives to be open-minded and fair-minded . That’s not easy: It demands that you constantly question your assumptions and biases and that you always remain open to considering opposing views.

In today’s polarized environment, many people think of themselves as critical thinkers simply because they ask skeptical questions—often directed at, say, certain government policies or ideas espoused by those on the “other side” of the political divide. The problem is, they may not be asking these questions with an open mind or a willingness to fairly consider opposing views.

When people do this, they’re engaging in “weak-sense critical thinking”—a term popularized by the late Richard Paul, a co-founder of The Foundation for Critical Thinking . “Weak-sense critical thinking” means applying the tools and practices of critical thinking—questioning, investigating, evaluating—but with the sole purpose of confirming one’s own bias or serving an agenda.

In AMBQ , I lay out a series of questions you can ask yourself to try to ensure that you’re thinking critically. Here are some of the questions to consider:

- Why do I believe what I believe?

- Are my views based on evidence?

- Have I fairly and thoughtfully considered differing viewpoints?

- Am I truly open to changing my mind?

Of course, becoming a better critical thinker is not as simple as just asking yourself a few questions. Critical thinking is a habit of mind that must be developed and strengthened over time. In effect, you must train yourself to think in a manner that is more effortful, aware, grounded, and balanced.

For those interested in giving themselves a crash course in critical thinking—something I did myself, as I was working on my book—I thought it might be helpful to share a list of some of the books that have shaped my own thinking on this subject. As a self-interested author, I naturally would suggest that you start with the new 10th-anniversary edition of A More Beautiful Question , but beyond that, here are the top eight critical-thinking books I’d recommend.

The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark , by Carl Sagan

This book simply must top the list, because the late scientist and author Carl Sagan continues to be such a bright shining light in the critical thinking universe. Chapter 12 includes the details on Sagan’s famous “baloney detection kit,” a collection of lessons and tips on how to deal with bogus arguments and logical fallacies.

Clear Thinking: Turning Ordinary Moments Into Extraordinary Results , by Shane Parrish

The creator of the Farnham Street website and host of the “Knowledge Project” podcast explains how to contend with biases and unconscious reactions so you can make better everyday decisions. It contains insights from many of the brilliant thinkers Shane has studied.

Good Thinking: Why Flawed Logic Puts Us All at Risk and How Critical Thinking Can Save the World , by David Robert Grimes

A brilliant, comprehensive 2021 book on critical thinking that, to my mind, hasn’t received nearly enough attention . The scientist Grimes dissects bad thinking, shows why it persists, and offers the tools to defeat it.

Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don't Know , by Adam Grant

Intellectual humility—being willing to admit that you might be wrong—is what this book is primarily about. But Adam, the renowned Wharton psychology professor and bestselling author, takes the reader on a mind-opening journey with colorful stories and characters.

Think Like a Detective: A Kid's Guide to Critical Thinking , by David Pakman

The popular YouTuber and podcast host Pakman—normally known for talking politics —has written a terrific primer on critical thinking for children. The illustrated book presents critical thinking as a “superpower” that enables kids to unlock mysteries and dig for truth. (I also recommend Pakman’s second kids’ book called Think Like a Scientist .)

Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems Scarce, Why It Matters , by Steven Pinker

The Harvard psychology professor Pinker tackles conspiracy theories head-on but also explores concepts involving risk/reward, probability and randomness, and correlation/causation. And if that strikes you as daunting, be assured that Pinker makes it lively and accessible.

How Minds Change: The Surprising Science of Belief, Opinion and Persuasion , by David McRaney

David is a science writer who hosts the popular podcast “You Are Not So Smart” (and his ideas are featured in A More Beautiful Question ). His well-written book looks at ways you can actually get through to people who see the world very differently than you (hint: bludgeoning them with facts definitely won’t work).

A Healthy Democracy's Best Hope: Building the Critical Thinking Habit , by M Neil Browne and Chelsea Kulhanek

Neil Browne, author of the seminal Asking the Right Questions: A Guide to Critical Thinking, has been a pioneer in presenting critical thinking as a question-based approach to making sense of the world around us. His newest book, co-authored with Chelsea Kulhanek, breaks down critical thinking into “11 explosive questions”—including the “priors question” (which challenges us to question assumptions), the “evidence question” (focusing on how to evaluate and weigh evidence), and the “humility question” (which reminds us that a critical thinker must be humble enough to consider the possibility of being wrong).

Warren Berger is a longtime journalist and author of A More Beautiful Question .

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Improving clinical reasoning techniques is the right way to facilitate decision-making from prognostic, diagnostic, and therapeutic points of view. However, the process to do that is to fill knowledge gaps by studying and growing experience and knowing some cognitive aspects to raise the awareness of thinking mechanisms to avoid cognitive ...

Critical thinking is a general reasoning process that informs a discipline and context-specific clinical reasoning process, and both are used in the complex process of clinical judgment (Bowles, 2000; Klenke-Borgmann et al., 2020; Victor-Chmil, 2013). For example, critical thinking informs our common day-to-day decision-making, such as ...

Teaching clinical reasoning is challenging, particularly in the time-pressured and complicated environment of the ICU. Clinical reasoning is a complex process in which one identifies and prioritizes pertinent clinical data to develop a hypothesis and a plan to confirm or refute that hypothesis. Clinical reasoning is related to and dependent on critical thinking skills, which are defined as one ...

Critical thinking skills are necessary to engage in effective patient care in the ICU, and clinicians and educators can help learners develop their reasoning skills by emphasizing the role of inductive reasoning in clinical practice, asking effective questions (using "how" and "why'), acknowledging the impact of cognitive biases in ...

Clinical reasoning is a multi-faceted and complex construct, the understanding of which has emerged from multiple fields outside of healthcare literature, primarily the psychological and behavioural sciences. The application of clinical reasoning is central to the advanced non-medical practitioner (ANMP) role, as complex patient caseloads with undifferentiated and undiagnosed diseases are now ...

As detailed in the table, multiple themes surrounding the cognitive and meta-cognitive processes that underpin clinical reasoning have been identified. Central to these processes is the practice of critical thinking. Much like the definition of clinical reasoning, there is also diversity with regard to definitions and conceptualisation of critical thinking in the healthcare setting.

critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and clinical decision-making. In the purest form, health profession educators are referencing the cognitive abilities of a clinician to transfer thinking skills from an academic to a clinical setting. The problem with teaching clinical reasoning in health professions is that the ability to transfer knowledge and skill to patient care is often inefficient ...

We examine the literature that questions the benefits of teaching clinical reasoning skills to increase diagnostic accuracy, and we identify methodological problems with those studies. ... Learners should be encouraged to understand the role of all these processes to mature and develop their critical thinking and clinical reasoning skills.