Eudora Welty's Rules for Writing

The Pulitzer-winning Southern writer, a master of the short story, would have been 107 years old today. Welty was the author of nearly 20 books, a skilled photographer, and an avid gardener. Humanities magazine has a compelling sketch of her work :

AP Her three avocations—gardening, current events, and photography—were, like her writing, deeply informed by a desire to secure fragile moments as objects of art. … She appears to see the people in her pictures as objects of affection, not abstract political points. … What Welty seems to say, without quite saying so, is that the best pictures and stories cannot simply reduce the creatures within their spell to specimens. True engagement requires a durable sympathy with the world.

I haven’t read much of Welty’s writing yet, but based on her essay “The Reading and Writing of Short Stories”—published in the February and March 1949 issues of The Atlantic— I have a feeling I should. The complete essay hasn’t been digitized, but you can read an excerpt here . Among her snippets of wisdom:

- “Every good story has mystery—not the puzzle kind, but the mystery of allurement.”

- “The great stories of the world are the ones that seem new to their readers on and on, always new because they keep their power of revealing something.”

- “Beware of tidiness.”

- “Beauty comes from form, from development of idea, from after-effect. It often comes from carefulness, lack of confusion, elimination of waste—and yes, those are the rules.”

But don’t follow the rules too closely. To quote Welty again: “Sometimes spontaneity is the most sparkling kind of beauty.” She put those ideas into practice in more than a dozen stories for The Atlantic , but because of copyright, only one of them is digitized thus far: “ A Worn Path ,” from our February 1941 issue. It’s a short story about an elderly African-American woman who travels down a country road to retrieve medicine for her grandson.

Biography of Eudora Welty, American Short-Story Writer

- Best Selling Authors

- Best Seller Reviews

- Book Clubs & Classes

- Classic Literature

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

- M.A., Classics, Catholic University of Milan

- M.A., Journalism, New York University.

- B.A., Classics, Catholic University of Milan

Eudora Welty (April 13, 1909 – July 23, 2001) was an American writer of short stories, novels, and essays, best known for her realistic portrayal of the South. Her most acclaimed work is the novel The Optimist’s Daughter, which won her a Pulitzer Prize in 1973, as well as the short stories “Life at the P.O.” and “A Worn Path.”

Fast Facts: Eudora Welty

- Full Name: Eudora Alice Welty

- Known For: American writer known for her short stories and novels set in the South

- Born: April 13, 1909 in Jackson, Mississippi

- Parents: Christian Webb Welty and Chestina Andrews Welty

- Died: July 23, 2001 in Jackson, Mississippi

- Education: Mississippi State College for Women, University of Wisconsin, and Columbia University

- Selected Works: A Curtain of Green ( 1941), The Golden Apples (1949), The Optimist’s Daughter (1972), One Writer’s Beginnings (1984)

- Awards: Guggenheim Fellowship (1942), Pulitzer Prize for Fiction (1973), American Academy of Arts and Letters Gold Medal for Fiction (1972), National Book Award (1983), Medal of Distinguished Contribution to American Letters (1991), PEN/Malamud Award (1992)

- Notable Quote: "The excursion is the same when you go looking for your sorrow as when you go looking for your joy."

Early Life (1909-1931)

Eudora Welty was born on April 13, 1909 in Jackson, Mississippi. Her parents were Christian Webb Welty and Chestina Andrews Welty. Her father, who was an insurance executive, taught her the “love for all instruments that instruct and fascinate”, while she inherited her proclivity for reading and language from her mother, a schoolteacher. The instruments that “instruct and fascinate,” including technology, were present in her fiction, and she also complemented her writerly work with photography. Welty graduated from Central High School in Jackson in 1925.

After high school, Welty enrolled in the Mississippi State College for Women, where she remained from 1925 to 1927, but then transferred to the University of Wisconsin to complete her studies in English Literature. Her father advised her to study advertising at Columbia University as a safety net, but she graduated during the Great Depression , which made it difficult for her to find work in New York.

Local Reporting (1931-1936)

Eudora Welty returned to Jackson in 1931; her father died of leukemia shortly after her return. She started working in the Jackson media with a job at a local radio station and she also wrote about Jackson society for the Commercial Appeal , a newspaper based in Memphis.

Two years later, in 1933, she started working for the Work Progress Administration , the New-Deal agency that developed public work projects during the Great Depression in order to employ job seekers. There she photographed, carried out interviews and collected stories on daily life in Mississippi. This experience allowed her to obtain a wider perspective on life in the South, and she used that material as a starting point for her stories.

Welty's house, located at 1119 Pinehurst Street, in Jackson, served as a gathering point for her and fellow writers and friends, and was christened the “Night-Blooming Cereus Club.”

She left her job at the Work Progress Administration in 1936 to become a full-time writer.

First Success (1936-1941)

- Death of a Traveling Salesman (1936)

- A Curtain of Green (1941)

- A Worn Path , 1941

- The Robber Bridegroom.

The 1936 publication of her short story “The Death of a Traveling Salesman,” which appeared in the literary magazine Manuscript and explored the mental toll isolation takes on an individual, was Welty’s springboard into literary fame. It attracted the attention of author Katherine Anne Porter, who became her mentor.

“The Death of a Traveling Salesman” reappeared in her first book of short stories, A Curtain of Green, published in 1941. The collection painted a portrait of Mississippi by highlighting its inhabitants, both Black and white, and presenting racial relations in a realistic manner. Other than “Death of a Traveling Salesman,” her collection contains other notable entries, such as “Why I Live at the P.O.” and "A Worn Path." Originally published in The Atlantic Monthly, "Why I Live at the P.O." casts a comical look at family relationships through the eyes of the protagonist who, once she became estranged from her family, took up living at the Post Office. “A Worn Path,” which originally appeared in The Atlantic Monthly as well, tells the story of Phoenix Jackson, an African American woman who journeys along the Natchez Trace, located in Mississippi, overcoming many hurdles, a repeated journey in order to get medicine for her grandson, who swallowed a lye and damaged his throat. "A Worn Path" won her the second-place O. Henry Award in 1941. The collection received praise for her “fanatic love of people,” according to The New York Times . “With a few lines she draws the gesture of a deaf-mute, the windblown skirts of a Negro woman in the fields, the bewilderment of a child in the sickroom of an old people's asylum—and she has told more than many an author might tell in a novel of six hundred pages,” wrote Marianne Hauser in 1941, in her review for The New York Times .

The following year, in 1942, she wrote the novella The Robber Bridegroom, which employed a fairy-tale-like set of characters, with a structure reminiscent of the works of the Grimm Brothers.

The War, the Mississippi Delta, and Europe (1942-1959)

- The Wide Net and Other Stories (1943)

- Delta Wedding (1946)

- Music from Spain (1948)

- The Golden Apples (1949)

- The Ponder Heart (1954)

- Selected Stories (1954)

- The Bride of the Innisfallen and Other Stories (1955)

Welty was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in March 1942, but instead of using it to travel, she decided to stay at home and write. Her short story “Livvie,” which appeared in The Atlantic Monthly, won her another O. Henry Award. However, as World War II raged on, her brothers and all members of the Night-Blooming Cereus Club were enlisted, which worried her to the point of consumption and she devoted little time to writing.

Despite her difficulties, Welty managed to publish two stories, both set in the Mississippi Delta: “The Delta Cousins” and “A Little Triumph.” She continued researching the area and turned to her friend John Robinson's relatives. Two cousins of Robinson who lived on the delta hosted Eudora and shared the diaries of John’s great-grandmother, Nancy McDougall Robinson. Thanks to these diaries, Welty was able to link the two short stories and turn them into a novel, titled Delta Wedding.

Upon the end of the war, she expressed discontent with the way her state did not uphold the value for which the war was fought, and took a hard stance against anti-Semitism, isolationism, and racism.

In 1949, Welty sailed for Europe for a six-month tour. There, she met with John Robinson, at the time a Fulbright scholar studying Italian in Florence. She also lectured at Oxford and Cambridge, and was the first woman to be allowed to enter the hall of Peterhouse College. When she came back from Europe in 1950, given her independence and financial stability, she tried to buy a home, but realtors in Mississippi would not sell to an unmarried woman. Welty led a private life, overall.

Her novella The Ponder Heart, which originally appeared in The New Yorker in 1953, was republished in book format in 1954. The novella follows the deeds of Daniel Ponder, a rich heir of Clay County, Mississippi, who has an everyman-like disposition towards life. The narrative is told from the perspective of his niece Edna. This “wonderful tragicomedy of good intentions in a durably sinful world,” per The New York Times, was turned into a Tony Award-winning Broadway play in 1956.

Activism and High Honors (1960–2001)

- The Shoe bird (1964)

- Thirteen Stories (1965)

- Losing Battles (1970)

- The Optimist’s Daughter (1972)

- The Eye of the Story (1979)

- The Collected Stories (1980)

- Moon Lake and Other Stories (1980)

- One Writer’s Beginnings (1984)

- Morgana: Two Stories from The Golden Apples (1988)

- On Writing (2002)

In 1960, Welty returned to Jackson to care for her elderly mother and two brothers. In 1963, after the assassination of Medgar Evers, the field secretary of the Mississippi chapter of the NAACP, she published the short story “Where Is the Voice Coming From?” in The New Yorker, which was narrated from the assassin’s point of view, in first person. Her 1970 novel Losing Battles, which is set over the course of two days, blended comedy and lyricism. It was her first novel to make the best seller list.

Welty was also a lifelong photographer, and her images often served as an inspiration for her short stories. In 1971, she published a collection of her photographs under the title One Time, One Place ; the collection largely depicted life during the Great Depression. The following year, in 1972, she wrote the novel The Optimist’s Daughter, about a woman who travels to New Orleans from Chicago to visit her ailing father following a surgery. There, she gets to know her father's shrew and young second wife, who seems negligent about her ailing husband, and she also reconnects with the friends and family she had left behind when she moved to Chicago. This novel won her the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1973.

In 1979 she published The Eye of the Story , a collection of her essays and reviews that had appeared in the The New York Book Review and other outlets. The compilation contained analysis and criticism of two trends at the time: the confessional novel and long literary biographies lacking original insight.

In 1983, Welty gave three afternoon lectures at Harvard University. In those, she talked about her upbringing and about how family and the environment she grew up in shaped her as a writer and as a person. She collected these lectures into a volume, One Writer’s Beginnings , in 1984, which became a best seller and a runner-up for the 1984 National Book Award for Nonfiction. This book was a rare peek into her personal life, which she usually remained private about—and instructed her friends to do the same. She died on July 23, 2001 in Jackson, Mississippi.

Style and Themes

A Southern writer, Eudora Welty placed great importance on the sense of place in her writing. In “A Worn Path,” she describes the Southern landscape in minute detail, while in “The Wide Net,” each character views the river in the story in a different manner. “Place” is also meant figuratively, as it often pertains to the relationship between individuals and their community, which is both natural and paradoxical. For example, in “Why I Live at the P.O.,” Sister, the protagonist, is in conflict with her family, and the conflict is marked by lack of proper communication. Likewise, in The Golden Apples, Miss Eckhart is a piano teacher who leads an independent lifestyle, which allows her to live as she pleases, yet she also longs to start a family and to feel that she belongs in her small town of Morgana, Mississippi.

She also used mythological imagery to give her hyperlocal situations and characters a universal dimension. For instance, the protagonist of “A Worn Path” is named Phoenix, just like the mythological bird with red and gold plumage known for rising from its ashes. Phoenix wears a handkerchief that’s red with gold undertones, and she is resilient in her quest to get medicine for her grandson. When it comes to representing powerful women, Welty refers to Medusa, the female monster whose stare could petrify mortals; such imagery occurs in “Petrified Man” and elsewhere.

Welty relied heavily on description. As she outlined in her essay, “The Reading and Writing of Short Stories,” which appeared in The Atlantic Monthly in 1949, she thought that good stories had an element of novelty and mystery, “not the puzzle kind, but the mystery of allurement.” And while she claimed that “beauty comes from development of idea, from after-effect. It often comes from carefulness, lack of confusion, elimination of waste—and yes, those are the rules,” she also cautioned writers to “beware of tidiness.”

Eudora Welty’s work has been translated into 40 languages. She personally influenced Mississippi writers such as Richard Ford, Ellen Gilchrist, and Elizabeth Spencer. The popular press, however, has had the tendency to pigeonhole her into the box of “literary aunt,” both because of how privately she lived and because her stories lacked the celebration of the faded aristocracy of the South and the depravation portrayed by authors such as Faulkner and Tennessee Williams.

- Bloom, Harold. Eudora Welty . Chelsea House Publ., 1986.

- Brown, Carolyn J. A Daring Life: A Biography of Eudora Welty . University of Mississippi, 2012.

- Welty, Eudora, and Ann Patchett. The Collected Stories of Eudora Welty . Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019.

- 42 Must-Read Feminist Female Authors

- Writing About Literature: Ten Sample Topics for Comparison & Contrast Essays

- Ralph Ellison

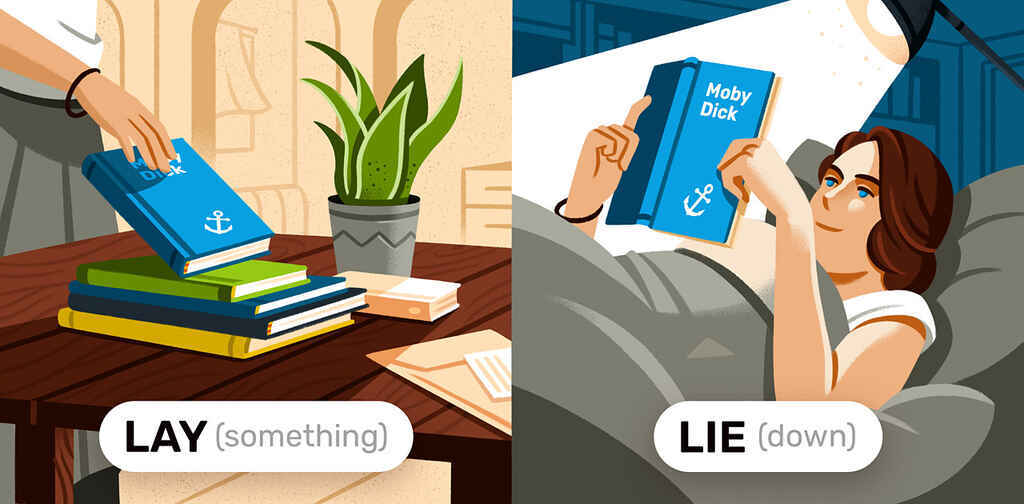

- What Are Partitives in Grammar?

- Top 100 Women of History

- Black History and Women's Timeline: 1950–1959

- How to Find the Theme of a Book or Short Story

- Biography of Ernest Hemingway, Pulitzer and Nobel Prize Winning Writer

- Biography of Jorge Luis Borges, Argentina's Great Storyteller

- The Story of Jessie Redmon Fauset

- Arna Bontemps, Documenting the Harlem Renaissance

- Doris Lessing

- Classic British and American Essays and Speeches

- Women of the Harlem Renaissance

- Biography of Lydia Maria Child, Activist and Author

- Biography of George Eliot, English Novelist

- O'Connor's Short Stories

Flannery O'Connor

- Literature Notes

- About O'Connor's Short Stories

- Summary and Analysis

- "A Good Man Is Hard to Find"

- "The Life You Save May Be Your Own"

- "The River"

- "A Late Encounter with the Enemy"

- "The Displaced Person"

- "Good Country People"

- "Everything That Rises Must Converge"

- "Revelation"

- "Parker's Back"

- "Judgement Day"

- Flannery O'Connor Biography

- Critical Essay

- Thoughts on O'Connor's Stories

- Essay Questions

- Cite this Literature Note

O'Connor appears to have developed, at a very early stage in her writing career, a sense of direction and purpose which allowed her to reject vigorously even proposed revisions suggested by Mr. Shelby, her contact at Rinehart. If changes were called for, she herself wanted to make them, and she did. In fact, the experimentation with atmosphere and tone which characterized the five stories in her master's thesis at Iowa and the seeming uncertainty about the direction of her work, which she expressed in an early letter to Elizabeth McKee, her literary agent, was replaced in less than a year by such a degree of self-confidence that she became interested in finding another publishing company for her yet-to-be-completed first novel.

In July 1948, O'Connor had written to McKee, "I don't have my novel outlined and I have to write to discover what I am doing. Like the old lady, I don't know so well what I think until I see what I say; then I have to say it over again." In February 1949, she wrote to McKee again, "I want mainly to be where they will take the book as I write it." Two weeks later, she wrote again to McKee, concerning a letter received from Shelby, "I presume Shelby says either that Rinehart will not take the novel as it will be if left to my fiendish care (it will be essentially as it is), or that Rinehart would like to rescue it at this point and train it into a conventional novel. . . . The letter [Shelby's letter to O'Connor] is addressed to a slightly dim-witted Camp Fire Girl, and I cannot look with composure on getting a lifetime of others like them."

The following day, O'Connor wrote to Mr. Shelby, "I feel that whatever virtues the novel may have are very much connected with the limitations you mention. I am not writing a conventional novel, and I think that the quality of the novel I write will derive precisely from the peculiarity or aloneness, if you will, of the experience I wrote from."

We may never know, as some critics suggest, whether O'Connor found in the writings of Nathaniel West, another American writer, confirmation of "the odd comic look of her world," or whether this confirmation strengthened her self-confidence to the extent that she could reject Shelby's suggested revisions. There is, however, evidence of O'Connor's acquaintance with West's work — especially in her story "The Peeler," a short story which first appeared in the December 1949 Partisan Review, and which was later revised to become Chapter 3 of Wise Blood.

West's cynical Willie Shrike, Miss Lonelyhearts' editor (from West's Miss Lonelyhearts ), appears reborn in Asa Shrike, the blind street preacher in "The Peeler"; he is then further transformed into Asa Hawks, the supposedly blind street preacher who cynically uses his "blindness," as well as his feigned religion, to wheedle a meager living from the people of Taulkingham (O'Connor's equivalent of Atlanta). When Hazel Motes (the protagonist of Wise Blood ) discovers Hawks' fraud, the revelation functions as one of the turning points which leads Hazel to reevaluate his life and to turn again to the religion from which he had so desperately attempted to flee. Although one may grant West's influence on the overall tone and the style of O'Connor's writing, one must remember that, as one critic has suggested, "West and O'Connor wrote out of opposing religious commitments."

With the exception of a number of the early stories, O'Connor consistently produced fiction having an implicit, if not a totally explicit, religious world view as an integral element of each work. This should come as no surprise to anyone familiar with her habit of attending mass each morning while she was at Iowa and going to mass with one of the Fitzgeralds each morning while she was in Connecticut. Even though O'Connor was, according to all available evidence, a devout Catholic, she did not let her religious conservatism interfere with the practice of her craft.

In numerous articles and letters to her friends, O'Connor stressed the need for the Catholic writer to make fiction "according to its nature . . . by grounding it in concrete observable reality" because when the Catholic writer "closes his own eyes and tries to see with the eyes of the Church, the result is another addition to that large body of pious trash for which we have so long been famous." As she noted in one article, "When people have told me that because I am a Catholic, I cannot be an artist, I have had to reply, ruefully, that because I am a Catholic, I cannot afford to be less than an artist."

O'Connor's concern with the generally low quality of religious literature and the typical lack of literary acumen among the average readers of religious stories led her to expend large amounts of her carefully managed energy in order to produce book reviews for The Bulletin, a diocesan paper of limited circulation, because, as she wrote a friend, it was "the only corporal work of mercy open to me." This, in spite of the fact that she had written to the same friend concerning her frustrations with the inaccurate reporting by The Bulletin of some of her comments: "They didn't want to hear what I said and when they heard it they didn't want to believe it and so they changed it. I also told them that the average Catholic reader was a Militant Moron but they didn't quote that naturally."

As a writer with professedly Christian concerns, O'Connor was, throughout her writing career, convinced that the majority of her audience did not share her basic viewpoint and was, if not openly hostile to it, at best indifferent. In order to reach such an audience, O'Connor felt that she had to make the basic distortions of a world separated from the original, divine plan "appear as distortions to an audience which is used to seeing them as natural." This she accomplished by resorting to the grotesque in her fiction.

To the "true believer," the "ultimate grotesqueness" is found in those postlapsarian (after the Fall) individuals who ignore their proper relationship to the Divine and either rebel against It or deny that they have any need to rely upon It for help in this life. In the first category, one would find those characters like Hazel Motes or Francis Marion Tarwater (the protagonists of her two novels), who flee from the call of the Divine only to find themselves pursued by It and ultimately forced to accept their role as children of God. Likewise, the Misfit, having finally decided to reject the account of Christ having raised Lazarus from the dead because he had not been there to witness it, accepts this world and its temporal pleasures only to discover, "It's no real pleasure in life."

In the second category, one can find those prideful, self-reliant individuals such as the Misfit and the grandmother (from "A Good Man Is Hard to Find"), Mrs. McIntyre (from "The Displaced Person"), and Hulga Hopewell (from "Good Country People"), who feel that they have conquered life because they are especially pious, prudent, and hardworking. To make these individuals appear grotesque to the secular humanist (one who argues that humans can, by their own ingenuity and wisdom, make a paradise of this earth, if given sufficient time), O'Connor creates, for example, the psychopathic killer, the pious fraud, or the physical or intellectual cripple. This display of what some critics have labeled the "gratuitous grotesque" became for O'Connor the means by which she hoped to capture the attention of her audience. She wrote in a very early essay, "when you can assume that your audience holds the same beliefs you do, you can relax a little and use more normal means of talking to it; when you have to assume that it does not, then you have to make your vision apparent by shock — to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost-blind you draw large and startling figures." For O'Connor, writing was a long, continuous shout.

No examination of O'Connor's view of her fiction would be complete without mentioning a couple of comments that she made concerning the nature of her work; in fact, anyone particularly interested in O'Connor should read Mystery and Manners , a collection of O'Connor's occasional prose, selected and edited by the Fitzgeralds. At one point in a section of that book entitled "On Her Own Work," O'Connor notes, "There is a moment in every great story in which the presence of grace can be felt as it waits to be accepted or rejected even though the reader may not recognize this moment."

At another point, she comments, "From my own experience in trying to make stories 'work,' I have discovered that what is needed is an action that is totally unexpected, yet totally believable, and I have found that, for me, this is always an action which indicates that grace has been offered. And frequently it is an action in which the devil has been the unwilling instrument of grace."

Without becoming totally bogged down in the Catholic doctrine of grace (a good Catholic dictionary will list at least ten to fifteen entries dealing with the subject), one should be aware of what O'Connor means when she uses the term in connection with her stories. Loosely defined, Illuminating Grace (the type of grace most frequently used by O'Connor in her stories) may be described as a gift, freely given by God, which is designed to enlighten the minds of people and help them toward eternal life. It may take the form of some natural mental experience, such as a dream or viewing a beautiful sunset, or of some experience imposed from outside the individual — for example, from hearing a sermon or from experiencing an intense joy, a sorrow, or some other shock.

Man, having been given free will, may, according to the Catholic position, elect not to accept the gift of grace, as opposed to a Calvinist position, which argues for a concept of Irresistible Grace — that is, man cannot reject God's grace when it is given to him. Even though O'Connor notes that she looks for the moment "in which the presence of grace can be felt as it waits to be accepted or rejected," one should not assume that she is attempting to pass judgment on the ultimate fate of her characters. That, from an orthodox point of view, is not possible for man to do. It is for this reason (much to the bewilderment of some of her readers) that O'Connor can say of the Misfit, "I prefer to think, however unlikely this may seem, the old lady's gesture . . . will be enough of a pain to him there to turn him into the prophet he was meant to become."

Even though O'Connor's vision was essentially religious, she chose to present it from a primarily comic or grotesque perspective. In a note to the second edition of Wise Blood, her first novel, O'Connor wrote, "It is a comic novel about a Christian malgré lui [in spite of himself], and as such, very serious, for all comic novels that are any good must be about matters of life and death." Several friends have verified O'Connor's problem with public readings of her stories.

When on lecture tours, O'Connor habitually read "A Good Man Is Hard to Find" because it was one of the few of her stories which she could read without breaking out in laughter. One acquaintance who had taken a class of students to Andalusia in order to meet O'Connor and to listen to a reading of one of her stories reported that as O'Connor neared the end of "Good Country People," "her reading had to be interrupted for perhaps as much as a minute while she laughed. I really doubted whether she would be able to finish the story."

For individuals incapable of seeing humanity as a group of struggling manikins operating against a backdrop of eternal purpose, many of O'Connor's stories appear to be filled with meaningless violence. Even those characters who are granted a moment of grace or experience an epiphanal vision do so only at the cost of having their self-images, if not themselves, destroyed. In a very real sense, all of O'Connor's characters have inherited the Original Sin of Adam, and all are equally guilty. The only distinction to be made between them is that some come to an awareness of their situation and some do not.

Next "A Good Man Is Hard to Find"

Looking to publish? Meet your dream editor, designer and marketer on Reedsy.

Find the perfect editor for your next book

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Last updated on Oct 29, 2023

How to Write a Short Story in 9 Simple Steps

This post is written by UK writer Robert Grossmith. His short stories have been widely anthologized, including in The Time Out Book of London Short Stories , The Best of Best Short Stories , and The Penguin Book of First World War Stories . You can collaborate with him on your own short stories here on Reedsy .

The joy of writing short stories is, in many ways, tied to its limitations. Developing characters, conflict, and a premise within a few pages is a thrilling challenge that many writers relish — even after they've "graduated" to long-form fiction.

In this article, I’ll take you through the process of writing a short story, from idea conception to the final draft.

How to write a short story:

1. Know what a short story is versus a novel

2. pick a simple, central premise, 3. build a small but distinct cast of characters, 4. begin writing close to the end, 5. shut out your internal editor, 6. finish the first draft, 7. edit the short story, 8. share the story with beta readers, 9. submit the short story to publications.

But first, let’s talk about what makes a short story different from a novel.

The simple answer to this question, of course, is that the short story is shorter than the novel, usually coming in at between, say, 1,000-15,000 words. Any shorter and you’re into flash fiction territory. Any longer and you’re approaching novella length .

As far as other features are concerned, it’s easier to define the short story by what it lacks compared to the novel . For example, the short story usually has:

- fewer characters than a novel

- a single point of view, either first person or third person

- a single storyline without subplots

- less in the way of back story or exposition than a novel

If backstory is needed at all, it should come late in the story and be kept to a minimum.

It’s worth remembering too that some of the best short stories consist of a single dramatic episode in the form of a vignette or epiphany.

GET ACCOUNTABILITY

Meet writing coaches on Reedsy

Industry insiders can help you hone your craft, finish your draft, and get published.

A short story can begin life in all sorts of ways.

It may be suggested by a simple but powerful image that imprints itself on the mind. It may derive from the contemplation of a particular character type — someone you know perhaps — that you’re keen to understand and explore. It may arise out of a memorable incident in your own life.

For example:

- Kafka began “The Metamorphosis” with the intuition that a premise in which the protagonist wakes one morning to find he’s been transformed into a giant insect would allow him to explore questions about human relationships and the human condition.

- Herman Melville’s “Bartleby the Scrivener” takes the basic idea of a lowly clerk who decides he will no longer do anything he doesn’t personally wish to do, and turns it into a multi-layered tale capable of a variety of interpretations.

When I look back on some of my own short stories, I find a similar dynamic at work: a simple originating idea slowly expands to become something more nuanced and less formulaic.

So how do you find this “first heartbeat” of your own short story? Here are several ways to do so.

Experiment with writing prompts

Eagle-eyed readers will notice that the story premises mentioned above actually have a great deal in common with writing prompts like the ones put forward each week in Reedsy’s short story competition . Try it out! These prompts are often themed in a way that’s designed to narrow the focus for the writer so that one isn’t confronted with a completely blank canvas.

Turn to the originals

Take a story or novel you admire and think about how you might rework it, changing a key element. (“Pride and Prejudice and Vampires” is perhaps an extreme product of this exercise.) It doesn’t matter that your proposed reworking will probably never amount to more than a skimpy mental reimagining — it may well throw up collateral narrative possibilities along the way.

Keep a notebook

Finally, keep a notebook in which to jot down stray observations and story ideas whenever they occur to you. Again, most of what you write will be stuff you never return to, and it may even fail to make sense when you reread it. But lurking among the dross may be that one rough diamond that makes all the rest worthwhile.

Like I mentioned earlier, short stories usually contain far fewer characters than novels. Readers also need to know far less about the characters in a short story than we do in a novel (sometimes it’s the lack of information about a particular character in a story that adds to the mystery surrounding them, making them more compelling).

Yet it remains the case that creating memorable characters should be one of your principal goals. Think of your own family, friends and colleagues. Do you ever get them confused with one another? Probably not.

Your dramatis personae should be just as easily distinguishable from one another, either through their appearance, behavior, speech patterns, or some other unique trait. If you find yourself struggling, a character profile template like the one you can download for free below is particularly helpful in this stage of writing.

FREE RESOURCE

Reedsy’s Character Profile Template

A story is only as strong as its characters. Fill this out to develop yours.

- “The Yellow Wallpaper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman features a cast of two: the narrator and her husband. How does Gilman give her narrator uniquely identifying features?

- “The Tell-Tale Heart” by Edgar Allan Poe features a cast of three: the narrator, the old man, and the police. How does Poe use speech patterns in dialogue and within the text itself to convey important information about the narrator?

- “A Good Man Is Hard to Find” by Flannery O’Connor is perhaps an exception: its cast of characters amounts to a whopping (for a short story) nine. How does she introduce each character? In what way does she make each character, in particular The Misfit, distinct?

He’s right: avoid the preliminary exposition or extended scene-setting. Begin your story by plunging straight into the heart of the action. What most readers want from a story is drama and conflict, and this is often best achieved by beginning in media res . You have no time to waste in a short story. The first sentence of your story is crucial, and needs to grab the reader’s attention to make them want to read on.

One way to do this is to write an opening sentence that makes the reader ask questions. For example, Kingsley Amis once said, tongue-in-cheek, that in the future he would only read novels that began with the words: “A shot rang out.”

This simple sentence is actually quite telling. It introduces the stakes: there’s an immediate element of physical danger, and therefore jeopardy for someone. But it also raises questions that the reader will want answered. Who fired the shot? Who or what were they aiming at, and why? Where is this happening?

We read fiction for the most part to get answers to questions. For example, if you begin your story with a character who behaves in an unexpected way, the reader will want to know why he or she is behaving like this. What motivates their unusual behavior? Do they know that what they’re doing or saying is odd? Do they perhaps have something to hide? Can we trust this character?

As the author, you can answer these questions later (that is, answer them dramatically rather than through exposition). But since we’re speaking of the beginning of a story, at the moment it’s enough simply to deliver an opening sentence that piques the reader’s curiosity, raises questions, and keeps them reading.

“Anything goes” should be your maxim when embarking on your first draft.

FREE COURSE

How to Craft a Killer Short Story

From pacing to character development, master the elements of short fiction.

By that, I mean: kill the editor in your head and give your imagination free rein. Remember, you’re beginning with a blank page. Anything you put down will be an improvement on what’s currently there, which is nothing. And there’s a prescription for any obstacle you might encounter at this stage of writing.

- Worried that you’re overwriting? Don’t worry. It’s easier to cut material in later drafts once you’ve sketched out the whole story.

- Got stuck, but know what happens later? Leave a gap. There’s no necessity to write the story sequentially. You can always come back and fill in the gap once the rest of the story is complete.

- Have a half-developed scene that’s hard for you to get onto the page? Write it in note form for the time being. You might find that it relieves the pressure of having to write in complete sentences from the get-go.

Most of my stories were begun with no idea of their eventual destination, but merely an approximate direction of travel. To put it another way, I’m a ‘pantser’ (flying by the seat of my pants, making it up as I go along) rather than a planner. There is, of course, no right way to write your first draft. What matters is that you have a first draft on your hands at the end of the day.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of the ending of a short story : it can rescue an inferior story or ruin an otherwise superior one.

If you’re a planner, you will already know the broad outlines of the ending. If you’re a pantser like me, you won’t — though you’ll hope that a number of possible endings will have occurred to you in the course of writing and rewriting the story!

In both cases, keep in mind that what you’re after is an ending that’s true to the internal logic of the story without being obvious or predictable. What you want to avoid is an ending that evokes one of two reactions:

- “Is that it?” aka “The author has failed to resolve the questions raised by the story.”

- “WTF!” aka “This ending is simply confusing.”

Like Truman Capote said, “Good writing is rewriting.”

Once you have a first draft, the real work begins. This is when you move things around, tightening the nuts and bolts of the piece to make sure it holds together and resembles the shape it took in your mind when you first conceived it.

In most cases, this means reading through your first draft again (and again). In this stage of editing , think to yourself:

- Which narrative threads are already in place?

- Which may need to be added or developed further?

- Which need to perhaps be eliminated altogether?

All that’s left afterward is the final polish . Here’s where you interrogate every word, every sentence, to make sure it’s earned its place in the story:

- Is that really what I mean?

- Could I have said that better?

- Have I used that word correctly?

- Is that sentence too long?

- Have I removed any clichés?

Trust me: this can be the most satisfying part of the writing process. The heavy lifting is done, the walls have been painted, the furniture is in place. All you have to do now is hang a few pictures, plump the cushions and put some flowers in a vase.

Eventually, you may reach a point where you’ve reread and rewritten your story so many times that you simply can’t bear to look at it again. If this happens, put the story aside and try to forget about it.

When you do finally return to it, weeks or even months later, you’ll probably be surprised at how the intervening period has allowed you to see the story with a fresh pair of eyes. And whereas it might have felt like removing one of your own internal organs to cut such a sentence or paragraph before, now it feels like a liberation.

The story, you can see, is better as a result. It was only your bloated appendix you removed, not a vital organ.

It’s at this point that you should call on the services of beta readers if you have them. This can be a daunting prospect: what if the response is less enthusiastic than you’re hoping for? But think about it this way: if you’re expecting complete strangers to read and enjoy your story, then you shouldn’t be afraid of trying it out first on a more sympathetic audience.

This is also why I’d suggest delaying this stage of the writing process until you feel sure your story is complete. It’s one thing to ask a friend to read and comment on your new story. It’s quite another thing to return to them sometime later with, “I’ve made some changes to the story — would you mind reading it again?”

So how do you know your story’s really finished? This is a question that people have put to me. My reply tends to be: I know the story’s finished when I can’t see how to make it any better.

This is when you can finally put down your pencil (or keyboard), rest content with your work for a few days, then submit it so that people can read your work. And you can start with this directory of literary magazines once you're at this step.

The truth is, in my experience, there’s actually no such thing as a final draft. Even after you’ve submitted your story somewhere — and even if you’re lucky enough to have it accepted — there will probably be the odd word here or there that you’d like to change.

Don’t worry about this. Large-scale changes are probably out of the question at this stage, but a sympathetic editor should be willing to implement any small changes right up to the time of publication.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

Bring your short stories to life

Fuse character, story, and conflict with tools in the Reedsy Book Editor. 100% free.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How Racist Was Flannery O’Connor?

By Paul Elie

In 1943, eighteen-year-old Mary Flannery O’Connor went north on a summer trip. Growing up in Georgia—she spent her childhood in Savannah, and went to high school in Milledgeville—she saw herself as a writer and artist in the making. She created illustrated books “too old for children and too young for grown-ups” and dryly titled an assemblage of her poems “The Priceless Works of M. F. O’Connor”; she drew cartoons and submitted them to magazines, noting that her hobby was “collecting rejection slips.”

On her travels, she and two cousins visited Manhattan: Chinatown, St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and Columbia University. Then they went to Massachusetts, and visited Radcliffe, where one cousin was a student. O’Connor disliked both schools, and said so in letters and postcards to her mother. (Her father had died two years earlier.) Back in Milledgeville, O’Connor studied at the state women’s college (“the institution of higher larning across the road”). In 1945, she made her next trip north, enrolling in the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where she dropped the Mary (it put her in mind of “an Irish washwoman”) and became Flannery O’Connor.

Less than two decades later, she died, in Milledgeville, of lupus. She was thirty-nine, the author of two novels and a book of stories. A brief obituary in the Times called her “one of the nation’s most promising writers.” Some of her readers dismissed her as a “regional writer”; many didn’t know she was a woman.

We are still learning who Flannery O’Connor was. The materials of her life story have surfaced gradually: essays in 1969, letters in 1979, an annotated Library of America volume in 1988, and a cache of personal items deposited at Emory University in 2012, which yielded the “ Prayer Journal ,” jottings on faith and fiction from her time at Iowa. Each phase has deepened the portrait of the artist and furthered her reputation. Southerners, women, Catholics, and M.F.A.-program instructors now approach her with devotion. We call her Flannery; we see her as a wise elder, a literary saint, poised for revelation at a typewriter set up on the ground floor of a farmhouse near Milledgeville because treatments for lupus left her unable to climb stairs.

O’Connor is now as canonical as Faulkner and Welty. More than a great writer, she’s a cultural figure: a funny lady in a straw hat, puttering among peacocks, on crutches she likened to “flying buttresses.” The farmhouse is open for tours; her visage is on a stamp. A recent book of previously unpublished correspondence, “ Good Things Out of Nazareth ” (Convergent), and a documentary, “Flannery: The Storied Life of the Writer from Georgia,” suggest a completed arc, situating her at the literary center where she might have been all along.

The arc is not complete, however. Those letters and postcards she sent home from the North in 1943 were made available to scholars only in 2014, and they show O’Connor as a bigoted young woman. In Massachusetts, she was disturbed by the presence of an African-American student in her cousin’s class; in Manhattan, she sat between her two cousins on the subway lest she have to sit next to people of color. The sight of white students and black students at Columbia sitting side by side and using the same rest rooms repulsed her.

It’s not fair to judge a writer by her juvenilia. But, as she developed into a keenly self-aware writer, the habit of bigotry persisted in her letters—in jokes, asides, and a steady use of the word “nigger.” For half a century, the particulars have been held close by executors, smoothed over by editors, and justified by exegetes, as if to save O’Connor from herself. Unlike, say, the struggle over Philip Larkin, whose coarse, chauvinistic letters are at odds with his lapidary poetry, it’s not about protecting the work from the author; it’s about protecting an author who is now as beloved as her stories.

The work largely deserves the love it gets. O’Connor’s fiction is full of scenarios that now have the feel of mid-century myths: an evangelist preaching the gospel of a Church Without Christ outside a movie house; a grandmother shot by an escaped convict at the roadside; a Bible salesman seducing a female “interleckshul” in a hayloft and taking her wooden leg. The late story “Parker’s Back,” from 1964, in which a tattooed ex-sailor tries to appease his puritanical wife by getting a life-size face of Christ inked onto his back, is a summa of O’Connor’s effects. There’s outlandish naming (Obadiah Elihue Parker), blunt characterization (“The skin on her face was thin and drawn as tight as the skin on an onion and her eyes were gray and sharp like the points of two icepicks”), and pungent speech (“Mr. Parker . . . You’re a walking panner-rammer!”). There’s the way the action hurtles to an end both comic and profound, and the sense, as she put it in an essay, “that something is going on here that counts.” There’s the attractive-repulsive force of religion, as Parker submits to the tattooer’s needle in the hope of making himself a holy image of Christ. And there’s a preoccupation with human skin, and skin coloring, as a locus of conflict.

O’Connor defined herself as a novelist, but many readers now come to her through her essays and letters, and the core truth to emerge from the expansion of her body of work is that the nonfiction is as strong and strange as the fiction. The 1969 book of essays, “ Mystery and Manners ,” is both an astute manual on the craft of writing and a statement of precepts for the religious artist; the 1979 book of letters, “ The Habit of Being ,” is bedside reading as wisdom literature, at once companionable and full of barbed, contrarian insights. That they are books was part of O’Connor’s design. She made carbon copies of her letters with publication in mind: fearing that lupus would cut her life short, as it had her father’s, she used the letters and essays to shape the posthumous interpretation of her fiction.

Even much of the material left out of those books is tart and epigrammatic. Here is O’Connor, fresh from Iowa, on what a writing program can do for a writer:

It can put him in the way of experienced writers and literary critics, people who are usually able to tell him after not too long a time whether he should go on writing or enroll immediately in the School of Dentistry.

Here she is on life in Milledgeville, from a 1948 letter to the director of Yaddo, the writers’ colony in upstate New York:

Lately we have been treated to some parades by the Ku Klux Klan. . . . The Grand Dragon and the Grand Cyclops were down from Atlanta and both made big speeches on the Court House square while hundreds of men stamped and hollered inside sheets. It’s too hot to burn a fiery cross, so they bring a portable one made with electric light bulbs.

On her first encounter, in 1956, with the scholar William Sessions:

He arrived promptly at 3:30, talking, talked his way across the grass and up the steps and into a chair and continued talking from that position without pause, break, breath, or gulp until 4:50. At 4:50 he departed to go to Mass (Ascension Thursday) but declared he would like to return after it so I thereupon invited him to supper with us. 5:50 brings him back, still talking, and bearing a sack of ice cream and cake to the meal. He then talked until supper but at that point he met a little head wind in the form of my mother, who is also a talker. Her stories have a non-stop quality, but every now and then she does have to refuel and every time she came down, he went up.

Reviewers of O’Connor’s fiction were vexed by her characters’ lack of interiority. Admirers of the nonfiction have reversed the charge, taking up the idea that the most vivid character in her work is Flannery O’Connor. The new film adroitly introduces the author-as-character. The directors—Mark Bosco, a Jesuit priest who teaches a course on O’Connor at Georgetown, and Elizabeth Coffman, who teaches film at Loyola University Chicago—draw on a full spread of archival material and documentary effects. The actress Mary Steenburgen reads passages from the letters; several stories are animated, with an eye to O’Connor’s adage that “to the hard of hearing you shout, and for the almost-blind you draw large and startling figures.” There’s a clip from John Huston’s 1979 film of her singular first novel, “Wise Blood,” which she wrote at Yaddo and in Connecticut before the onset of lupus forced her to return home. Erik Langkjaer, a publishing sales rep O’Connor fell in love with, describes their drives in the country. Alice Walker tells of living “across the way” from the farmhouse during her teens, not knowing that a writer lived there: “It was one of my brothers who took milk from her place to the creamery in town. When we drove into Milledgeville, the cows that we saw on the hillside going into town would have been the cows of the O’Connors.”

In May, 1955, O’Connor went to New York to promote her story collection, “ A Good Man Is Hard to Find ,” on TV. The rare footage of O’Connor lights up the documentary. She sits, very still, in a velvet-trimmed black dress; her accent is strong, her demeanor assured. “I understand you are living on a farm,” the host prompts. “Yes,” she says. “I only live on one, though. I don’t see much of it. I’m a writer, and I farm from the rocking chair.” He asks her if she is a regional writer, and she replies:

I think that to overcome regionalism, you must have a great deal of self-knowledge. I think that to know yourself is to know your region, and that it’s also to know the world, and in a sense, paradoxically, it’s also to be an exile from that world. So that you have a great deal of detachment.

That is a profound and stringent definition of the writer’s calling. It locates the writer’s art in the refinement of her character: the struggle to overcome an outlook that is an obstacle to a greater good, the letting go of the comforts of home. And it recognizes that detachment can leave the writer alone and apart.

Link copied

At Iowa and in Connecticut, O’Connor had begun to read European fiction and philosophy, and her work, old-time in its particulars, is shot through with contemporary thought: Gabriel Marcel’s Christian existentialism, Martin Buber’s sense of “the eclipse of God.” She saw herself as “a Catholic peculiarly possessed of the modern consciousness” and saw the South as “Christ-haunted.”

All this can suggest points of similarity with Martin Luther King, Jr., another Georgian who was infused with Continental ideas up north and then returned south to take up a brief, urgent calling. Born four years apart, they grasped the Bible’s pertinence to current events, and saw religion as the tie that bound blacks and whites—as in her second novel, “ The Violent Bear It Away ,” from 1960, which opens with a black farmer giving a white preacher a Christian burial. O’Connor and King shared a gift for the convention-upending gesture, as in her story “The Enduring Chill,” in which a white man tries to affirm equality with the black workers on his mother’s farm by smoking cigarettes with them in the barn.

O’Connor lectured in a dozen states and often went to Atlanta to visit her doctors; she saw plenty of the changing South. That’s clear from her 1961 story “Everything That Rises Must Converge.” (The title alludes to a thesis advanced by the French Jesuit Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, who saw the world as gradually “divinized” by human activity in a kind of upward spiral.) A white man, living at home after college, takes his mother to “reducing class” on a newly integrated city bus. The sight of an African-American woman wearing the same style of hat that his mother is wearing stirs him to reflect on all that joins them. The sight of a black boy in the woman’s company prompts his mother to give the boy a gift: a penny with Lincoln’s profile on it. Things get grim after that.

The story was published in “Best American Short Stories” and won an O. Henry Prize in 1963. O’Connor declared that it was all she had to say on “That Issue.” It wasn’t. In May, 1964, she wrote to her friend Maryat Lee, a playwright who was born in Tennessee, lived in New York, and was ardent for civil rights:

About the Negroes, the kind I don’t like is the philosophizing prophesying pontificating kind, the James Baldwin kind. Very ignorant but never silent. Baldwin can tell us what it feels like to be a Negro in Harlem but he tries to tell us everything else too. M. L. King I dont think is the ages great saint but he’s at least doing what he can do & has to do. Don’t know anything about Ossie Davis except that you like him but you probably like them all. My question is usually would this person be endurable if white. If Baldwin were white nobody would stand him a minute. I prefer Cassius Clay. “If a tiger move into the room with you,” says Cassius, “and you leave, that dont mean you hate the tiger. Just means you know you and him can’t make out. Too much talk about hate.” Cassius is too good for the Moslems.

That passage, published in “The Habit of Being,” echoed a remark in a 1959 letter, also to Maryat Lee, who had suggested that Baldwin—his “Letter from the South” had just run in Partisan Review —could pay O’Connor a visit while on a subsequent reporting trip. O’Connor demurred:

No I can’t see James Baldwin in Georgia. It would cause the greatest trouble and disturbance and disunion. In New York it would be nice to meet him; here it would not. I observe the traditions of the society I feed on—it’s only fair. Might as well expect a mule to fly as me to see James Baldwin in Georgia. I have read one of his stories and it was a good one.

O’Connor-lovers have been downplaying those remarks ever since. But they are not hot-mike moments or loose talk. They were written at the same desk where O’Connor wrote her fiction and are found in the same lode of correspondence that has brought about the rise in her stature. This has put her champions in a bind—upholding her letters as eloquently expressive of her character, but carving out exceptions for the nasty parts.

Last year, Fordham University hosted a symposium on O’Connor and race, supported with a grant from the author’s estate. The organizer, Angela Alaimo O’Donnell, edits a series of books on Catholic writers funded by the estate, has compiled a book of devotions drawn from O’Connor’s work, and has written a book of poems that “channel the voice” of the author. In a new volume in the series, “ Radical Ambivalence: Race in Flannery O’Connor ” (Fordham), she takes up Flannery and That Issue. Proposing that O’Connor’s work is “race-haunted,” she applies techniques from whiteness studies and critical race theory, as well as Toni Morrison’s idea of “Africanist ‘othering.’ ” O’Donnell presents a previously unpublished passage on race and engages with scholars who have offered context for the racist remarks. Although she is palpably anguished about O’Connor’s race problem, she winds up reprising those earlier arguments in current literary-critical argot, treating O’Connor as “transgressive in her writing about race” but prone to lapses and excesses that stemmed from social forces beyond her control.

The context arguments go like this. O’Connor was a writer of her place and time, and her limitations were those of “the culture that had produced her.” Forced by illness to return to Georgia, she was made captive to a “Southern code of manners” that maintained whites’ superiority over blacks, but her fiction subjects the code to scrutiny. Although she used racial epithets carelessly in her correspondence, she dealt with race courageously in the fiction, depicting white characters pitilessly and creating upstanding black characters who “retain an inviolable privacy.” And she was admirably leery of cultural appropriation. “I don’t feel capable of entering the mind of a Negro,” she told an interviewer—a reluctance that Alice Walker lauded in a 1975 essay.

All the contextualizing produces a seesaw effect, as it variously cordons off the author from history, deems her a product of racist history, and proposes that she was as oppressed by that history as anybody else was. It backdates O’Connor as a writer of her time when she was a near-contemporary of writers typically seen as writers of our time: Gabriel García Márquez (born 1927), Maya Angelou (1928), Ursula K. Le Guin (1929), Tom Wolfe (1930), and Derek Walcott (1930), among others. It suggests that white racism in Georgia was all-encompassing and brooked no dissent, even though (as O’Donnell points out) Georgia was then changing more dramatically than at any point before or since. Patronizingly, it proposes that O’Connor, a genius who prized detachment, lacked the free will to think for herself.

Another writer of that cohort is Toni Morrison, who was born in Ohio in 1931 and became a Catholic at the age of twelve. Morrison published “ Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination ” in 1992. “The fabrication of an Africanist persona” by a white writer, she proposed, “is reflexive: an extraordinary meditation on the self; a powerful exploration of the fears and desires that reside in the writerly consciousness.” Invoking Morrison, O’Donnell argues that O’Connor’s fiction is fundamentally a working-through of her own racism, and that the offending remarks in the letters “tell us . . . that O’Connor understood evil in the form of racism from the inside, as one who has practiced it.”

The clinching evidence is “Revelation,” drafted in late 1963. This extraordinary story involves Ruby Turpin—a white Southerner in middle age, the owner of a dairy farm—and her encounter in a doctor’s waiting room with a Wellesley-educated young woman, also white, who is so repulsed by Turpin’s condescension toward people there that she cries out, “Go back to hell where you came from, you old wart hog.” This arouses Turpin to quarrel with God as she surveys a hog pen on her property, and calls forth a magnificent final image of the hereafter in Turpin’s eyes—the people of the rural South heading heavenward. Some say this “vision” redeems the author on That Issue. Brad Gooch, in a 2009 biography , likened it to the dream that Martin Luther King, Jr., spelled out in August, 1963; O’Donnell, drawing on a remark in the letters, depicts it as a “vision O’Connor has been wresting from God every day for much of her life.” Seeing it that way is a stretch. King’s “I Have a Dream” speech envisioned blacks and whites holding hands at the end of time; Turpin’s vision, by contrast, is a segregationist’s vision, in which people process to Heaven by race and class, equal but separate, white landowners such as Turpin preceded (the last shall be first) by “bands of black niggers in white robes, and battalions of freaks and lunatics shouting and clapping and leaping like frogs.”

After revising “Revelation” in early 1964, O’Connor wrote several letters to Maryat Lee. Many scholars maintain that their letters (often signed with nicknames) are a comic performance, with Lee playing the over-the-top liberal and O’Connor the dug-in gradualist, but O’Connor’s most significant remarks on race in her letters to Lee are plainly sincere. On May 3, 1964—as Richard Russell, Democrat of Georgia, led a filibuster in the Senate to block the Civil Rights Act—O’Connor set out her position in a passage now published for the first time: “You know, I’m an integrationist by principle & a segregationist by taste anyway. I don’t like negroes. They all give me a pain and the more of them I see, the less and less I like them. Particularly the new kind.” Two weeks after that, she told Lee of her aversion to the “philosophizing prophesying pontificating kind.” Ravaged by lupus, she wrote Lee a note to say that she was checking in to the hospital, signing it “Mrs. Turpin.” She died at home ten weeks later.

Those remarks show a view clearly maintained and growing more intense as time went on. They were objectionable when O’Connor made them. And yet—the argument goes—they’re just remarks, made in chatty letters by an author in extremis. They’re expressive but not representative. Her “public work” (as the scholar Ralph C. Wood calls it) is more complex, and its significance for us lies in its artfully mixed messages, for on race none of us is without sin and in a position to cast a stone.

That argument, however, runs counter to history and to O’Connor’s place in it. It sets up a false equivalence between the “segregationist by taste” and those brutally oppressed by segregation. And it draws a neat line between O’Connor’s fiction and her other writing where race is involved, even though the long effort to move her from the margins to the center has proceeded as if that line weren’t there. Those remarks don’t belong to the past, or to the South, or to literary ephemera. They belong to the author’s body of work; they help show us who she was.

Posterity, in literature, is a strange god—consecrating Dickinson and Melville as American divines, repositioning T. S. Eliot as a man on the run from a Missouri boyhood and a bad marriage. Posterity has favored Flannery O’Connor: the readers of her work today far outnumber those in her lifetime. After her death, the racist passages were stumbling blocks to the next generation’s encounter with her, and it made a kind of sense to sidestep them. Now the reluctance to face them squarely is itself a stumbling block, one that keeps us from approaching her with the seriousness that a great writer deserves.

There’s a way forward, rooted in the work. For twenty years, the director Karin Coonrod has staged dramatic adaptations of O’Connor’s stories. Following a stipulation of the author’s estate, she uses every word: narration, description, dialogue, imagery, and racial epithets. Members of the multiracial cast circulate the full text fluidly from actor to actor, character to character, so that the author’s words, all of them, ring out in her own voice and in other voices, too. ♦

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Katy Waldman

By Lauren Michele Jackson

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Take risks and tell the truth: how to write a great short story

Drawing on writers from Anton Chekhov to Kit de Waal, Donal Ryan explores the art of writing short fiction. Plus Chris Power on the best books for budding short story writers

T he first story I wrote outside of school was about Irish boxer Barry McGuigan. I was 10 and I loved Barry. He’d just lost his world featherweight title to the American Steve Cruz under the hellish Nevada sun and the only thing that could mend my broken heart was a restoration of my hero’s belt. Months passed and there was no talk of a rematch, so I wrote a story about it.

My imagined fight was in Ireland, and I was ringside. In my story I’d arranged the whole thing. I’d even given Barry some tips on countering Steve’s vicious hook. It went the distance but Barry won easily on points. He hugged Steve. His dad sang “Danny Boy”. I felt as I finished my story an intense relief. The world in that moment was restful and calm. I’d created a new reality for myself, and I was able to occupy it for a while, to feel a joy I’d created by moving a biro across paper. I think of that story now every single time I sit down to write. I strive for the feeling of rightness it gave me, that feeling of peace.

It took me a while to regain that feeling. When I left school, where I was lucky enough to be roundly encouraged and told with conviction that I was a writer, I inexplicably embarked on a career of self-sabotage, only allowing my literary ambitions to surface very sporadically, and then burning the results in fits of disgust. Nothing I wrote rang true; nothing felt worthy of being read.

Shortly after I got married my mother-in-law happened upon a file on the hard drive of a PC I’d loaned her (there’s a great and terrifying writing prompt!). It contained a ridiculous story about a young solicitor being corrupted by a gangster client. I’d forgotten about the story, and about one of its peripheral characters, a simple and pure-hearted man named Johnsey Cunliffe. My wife suggested giving Johnsey new life, and I started a rewrite with him as the hero; the story kept growing until I found myself with a draft of my first finished novel, The Thing About December . I didn’t feel embarrassed, nor did I feel an urge to burn it. I felt peace. I knew it wouldn’t last, and so I quickly wrote a handful of new stories, and the peace didn’t dissipate. Not for a while, anyway.

So a forgotten short story, written somewhere in the fog of my early 20s, turned out to be the making of my writing career. Maybe it would have happened anyway, or maybe not, but I think the impulse would always have been present, the urge to put a grammar on the ideas in my head. Mary Costello, author of The China Factory , one of the finest short story collections I’ve ever read, says: “Write only what’s essential, what must be written … an image or a story that keeps gnawing, that won’t leave you alone. And the only way to get peace is to write it.”

I know that in this straitened, rule-bound, virus-ridden present, many people find themselves with that gnawing feeling, that urge to fashion from language a new reality, or to get the idea that’s been clamouring inside them out of their imagination and into the world. So I’ve put together some ideas with the help of some of my favourite writers on how best to go about finding that peace.

Don’t worry

In a short story, the sentences have to do so much! Some of Chekhov’s stories are less than three printed pages; a few comprise a single brief paragraph. In his most famous story, “The Lady with the Dog”, we are given a detailed account of the nature, history and motivations of Gurov within the first page, but there is no feeling of stress or overload. Stephen King’s 2010 collection Full Dark, No Stars is a masterclass in compression and suspense. My colleague in creative writing at the University of Limerick, Sarah Moore Fitzgerald, is, like me, a novelist who turns occasionally to the short form. Sarah considers short stories to be “storytelling’s finest gifts. In the best ones, nothing is superfluous, their focus is sharp and vivid but they can be gloriously elliptical too, full of echoes.” The novel form, as I’ve heard Mike McCormack say, offers “a wonderful accommodation to the writer”, but the short story is a barren territory. There’s nowhere to hide, no space for excess or digression.

My wife asked me once why this worried me so much. I’d just published my first two novels and had embarked on a whole collection of short stories, A Slanting of the Sun . She’d come home from work to find me curled up in a ball of despair. “Every sentence worries me,” I whined. “None of them is doing enough .” “Don’t worry about how much they’re doing until all the work is done,” she said. “Get the story written, and then you can go back and fix all those worrisome sentences. And the chances are, once the story exists, you won’t be as worried about those sentences at all. They’ll just be. ”

Ah. I can still feel the beautiful relief I felt at her wise words. Life is filled with things to worry about. The quality of our sentences should be a challenge and a constant fruitful quest, a gradual aggregation of attainment. But creativity should always bring us at least some whisper of joy. It should be a way out of worry.

One of the concepts my colleague Sarah illuminates is that of a “draft zero” – a draft that comes before a first draft, where your story is splashed on to your screen or page, containing all or most of its desired elements. Draft zero offers complete freedom from any consideration of craft or finesse.

Kit de Waal, who recently published a wonderful collection, Supporting Cast , featuring characters from her novels, offers this wisdom on getting your story from your head on to your page or screen: “Don’t overthink but do overwrite. Sometimes you see a pair of gloves or a flower on the street or lipstick on a coffee cup and it moves you in a particular way. That’s your prompt right there. Write that feeling or set something around that idea, you don’t know what at this stage, you’re going off sheer muse, writerly energy, so just follow it. And follow it right to the end – it might be a day, a week, a year. Overwrite the thing and then sit back and ask yourself, ‘Where is the magic? What am I saying? Who is speaking?’ When you’ve worked that out, you have your story and you can start crafting and editing.”

Your draft zero is Michelangelo’s lump of rough-hacked marble, but with David’s basic shape. It is the reassuring existence of something tangible in the world outside of your mind , something raw and real, containing within its messy self the potential for greatness. And the best way to make it great is to make it truthful.

Be truthful

I don’t mean by this that you need to speak your own truth at all times or to draw only on your own lived experience, but it’s important to be true to our own impulses and ambitions as writers; to write the story we want to write, not the story we think we should write. That’s like saying things that you think people want to hear: you’ll end up tangling yourself in a knot of half-truths and constructed, co-opted beliefs. You’ll be more politician than writer, and, as good and decent as some of them are, the world definitely has enough politicians.

Your own experiences, of course, your own truth, can be parlayed into wonderful fictions, and can by virtue of their foundation in reality contain an almost automatic immediacy and intensity. Melatu Uche Okorie’s debut collection, This Hostel Life , is drawn from her experiences in the Irish direct provision system as an asylum seeker. The title story in particular has about it a feeling of absolute truthfulness, written in the demotic of the author’s Nigerian countrywomen; while another story, “Under the Awning”, feels as though it might be an oblique description of events witnessed or experienced first-hand by the author.

You might as well do exactly what you want to do, even (or especially) if it’s never been done before. You have nothing to lose by taking risks, with form, content, style, structure or any other element of your piece of fiction. Rob Doyle , a consummate literary risk-taker, exhorts writers to “try writing a story that doesn’t look how short stories are meant to look – try one in the form of an encyclopaedia entry, or a list, or an essay, or a review of an imaginary restaurant, sex toy, amusement park or film. Have people wondering if it’s even fiction. Mix it all up. Short stories can explore ideas as well as emotions – huge ideas can fit into short stories. For proof, read the work of Jorge Luis Borges . In fact, I second Roberto Bolaño’s advice to anyone writing short stories: read Borges.”

Bend the iron bar

“When the curtain falls,” said Frank O’Connor of the short story, “everything must be changed. An iron bar must have been bent and been seen to be bent.” One of the first short stories to break my heart was O’Connor’s “ Guests of the Nation ”. It has been described as one of the greatest anti-war stories ever written, and one of the finest stories from a master of the form. Its devastating denouement closes with this plaintive statement from the shattered narrator: “And anything that happened to me afterwards, I never felt the same about again.” This line contains within it an entreaty to short story writers to reach for that profound moment, that event or epiphany or reversal or triumph; to arrive within the confines of their story at a moment that will have a resonance far beyond its narrow scope.

Another great literary O’Connor, this time the novelist Joseph, who teaches creative writing at the University of Limerick, says that “to me every excellent short story centres around an instant where intense change becomes possible or, at least, imaginable for the character. Cut into the story late, leave it early, and find a moment.” Joseph quotes the closing words of one of his favourite short stories, Raymond Carver’s “Fat”: “It is August. My life is going to change. I feel it.”

The moment of course needn’t be in the ending, and the end of a story doesn’t necessarily have to be incendiary or revelatory, or to contain an unexpected twist. Mary Gaitskill ’s story “Heaven” describes a family going through change and trauma and loss, and iron bars are bent in almost every paragraph, but its ending is memorable for the moment of relief it offers, in a gently muted description of the perfect grace of a summer evening and a family gathered for a meal. “They all sat in lawn chairs and ate from the warm plates in their laps. The steak was good and rare; its juices ran into the salad and pasta when Virginia moved her knees. A light wind blew loose hairs around their faces and tickled them. The trees rustled dimly. There were nice insect noises. Jarold paused, a forkful of steak rising across his chest. ‘Like heaven,’ he said. ‘It’s like heaven.’ They were quiet for several minutes.”

Listen to your story

“Beer Trip to Llandudno”, Kevin Barry’s masterpiece of the short form, from his 2012 collection Dark Lies the Island , is another story that has remained pristine in my consciousness since I first read it. Part of the magic of that story, and of all Barry’s work, is its dialogue: the earthy, pithy, perfectly authentic exchanges between his characters. When I asked Kevin about this, he said: “If you feel like you’re coming towards the final draft of a story, print it out and read it aloud, slowly, with red pen in hand. Your ear will catch all the evasions and the false notes in the story much quicker than your eye will catch them on the screen or page. Listen to what’s not being said in the dialogue. Very often the story, and the drama, is to be found just underneath the surface of the talk.”

Such scrupulous attention to the burden carried by each unit of language and to the work done by the notes played and unplayed can make a story truly shine. Alice Kinsella is an accomplished poet who recently turned her hand to the short form in great style with her sublime account of early motherhood, “Window”. “Poetry or prose,” Alice says, “the aim is the same, to make every word earn its place on the page.”

Ignore everything

And as self-defeating as this sounds, here’s a final piece of advice: once you sit down to write your story, forget about this article. Forget all the advice you’ve ever been given. Free your hand, free your mind, cut yourself loose into the infinity of possibility, and create from those 26 little symbols what you will. We came from the hearts of stars. We are the universe, telling itself its own story.

Donal Ryan is a judge for the BBC national short story award with Cambridge University. The shortlist will be announced on 10 September and the winner on 19 October. For more information see www.bbc.co.uk/nssa .

Books for budding short story writers By Chris Power