- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Implementation...

Implementation research: what it is and how to do it

- Related content

- Peer review

- David H Peters , professor 1 ,

- Taghreed Adam , scientist 2 ,

- Olakunle Alonge , assistant scientist 1 ,

- Irene Akua Agyepong , specialist public health 3 ,

- Nhan Tran , manager 4

- 1 Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Department of International Health, 615 N Wolfe St, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA

- 2 Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, World Health Organization, CH-1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland

- 3 University of Ghana School of Public Health/Ghana Health Service, Accra, Ghana

- 4 Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, Implementation Research Platform, World Health Organization, CH-1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland

- Correspondence to: D H Peters dpeters{at}jhsph.edu

- Accepted 8 October 2013

Implementation research is a growing but not well understood field of health research that can contribute to more effective public health and clinical policies and programmes. This article provides a broad definition of implementation research and outlines key principles for how to do it

The field of implementation research is growing, but it is not well understood despite the need for better research to inform decisions about health policies, programmes, and practices. This article focuses on the context and factors affecting implementation, the key audiences for the research, implementation outcome variables that describe various aspects of how implementation occurs, and the study of implementation strategies that support the delivery of health services, programmes, and policies. We provide a framework for using the research question as the basis for selecting among the wide range of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods that can be applied in implementation research, along with brief descriptions of methods specifically suitable for implementation research. Expanding the use of well designed implementation research should contribute to more effective public health and clinical policies and programmes.

Defining implementation research

Implementation research attempts to solve a wide range of implementation problems; it has its origins in several disciplines and research traditions (supplementary table A). Although progress has been made in conceptualising implementation research over the past decade, 1 considerable confusion persists about its terminology and scope. 2 3 4 The word “implement” comes from the Latin “implere,” meaning to fulfil or to carry into effect. 5 This provides a basis for a broad definition of implementation research that can be used across research traditions and has meaning for practitioners, policy makers, and the interested public: “Implementation research is the scientific inquiry into questions concerning implementation—the act of carrying an intention into effect, which in health research can be policies, programmes, or individual practices (collectively called interventions).”

Implementation research can consider any aspect of implementation, including the factors affecting implementation, the processes of implementation, and the results of implementation, including how to introduce potential solutions into a health system or how to promote their large scale use and sustainability. The intent is to understand what, why, and how interventions work in “real world” settings and to test approaches to improve them.

Principles of implementation research

Implementation research seeks to understand and work within real world conditions, rather than trying to control for these conditions or to remove their influence as causal effects. This implies working with populations that will be affected by an intervention, rather than selecting beneficiaries who may not represent the target population of an intervention (such as studying healthy volunteers or excluding patients who have comorbidities).

Context plays a central role in implementation research. Context can include the social, cultural, economic, political, legal, and physical environment, as well as the institutional setting, comprising various stakeholders and their interactions, and the demographic and epidemiological conditions. The structure of the health systems (for example, the roles played by governments, non-governmental organisations, other private providers, and citizens) is particularly important for implementation research on health.

Implementation research is especially concerned with the users of the research and not purely the production of knowledge. These users may include managers and teams using quality improvement strategies, executive decision makers seeking advice for specific decisions, policy makers who need to be informed about particular programmes, practitioners who need to be convinced to use interventions that are based on evidence, people who are influenced to change their behaviour to have a healthier life, or communities who are conducting the research and taking action through the research to improve their conditions (supplementary table A). One important implication is that often these actors should be intimately involved in the identification, design, and conduct phases of research and not just be targets for dissemination of study results.

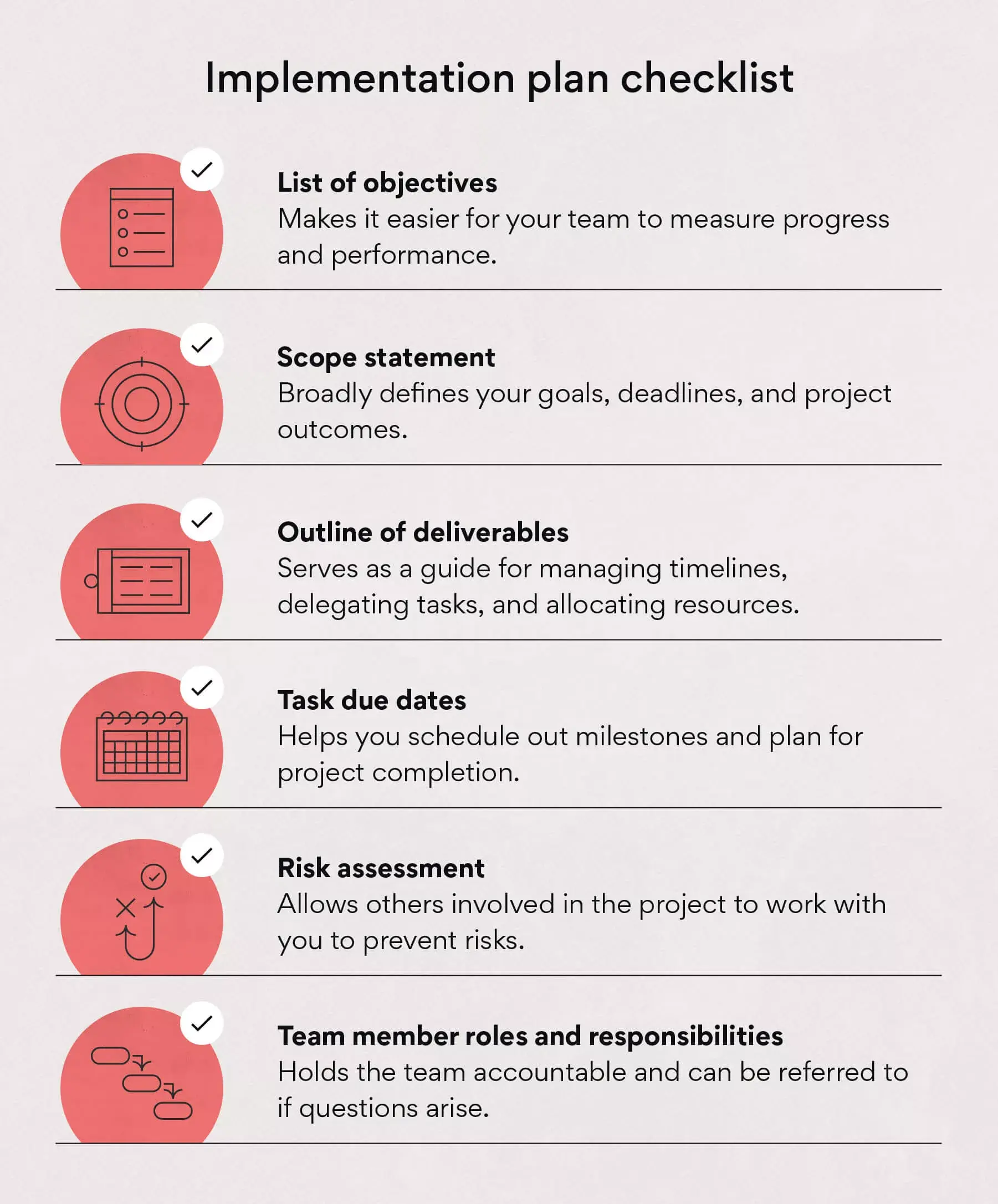

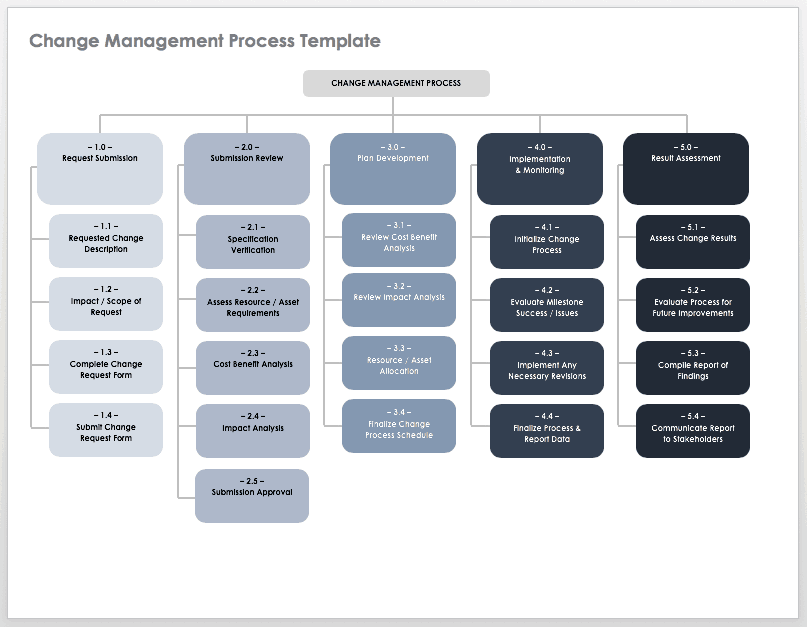

Implementation outcome variables

Implementation outcome variables describe the intentional actions to deliver services. 6 These implementation outcome variables—acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, feasibility, fidelity, implementation cost, coverage, and sustainability—can all serve as indicators of the success of implementation (table 1 ⇓ ). Implementation research uses these variables to assess how well implementation has occurred or to provide insights about how this contributes to one’s health status or other important health outcomes.

Implementation outcome variables

- View inline

Implementation strategies

Curran and colleagues defined an “implementation intervention” as a method to “enhance the adoption of a ‘clinical’ intervention,” such as the use of job aids, provider education, or audit procedures. 7 The concept can be broadened to any type of strategy that is designed to support a clinical or population and public health intervention (for example, outreach clinics and supervision checklists are implementation strategies used to improve the coverage and quality of immunisation).

A review of ways to improve health service delivery in low and middle income countries identified a wide range of successful implementation strategies (supplementary table B). 8 Even in the most resource constrained environments, measuring change, informing stakeholders, and using information to guide decision making were found to be critical to successful implementation.

Implementation influencing variables

Other factors that influence implementation may need to be considered in implementation research. Sabatier summarised a set of such factors that influence policy implementation (clarity of objectives, causal theory, implementing personnel, support of interest groups, and managerial authority and resources). 9

The large array of contextual factors that influence implementation, interact with each other, and change over time highlights the fact that implementation often occurs as part of complex adaptive systems. 10 Some implementation strategies are particularly suitable for working in complex systems. These include strategies to provide feedback to key stakeholders and to encourage learning and adaptation by implementing agencies and beneficiary groups. Such strategies have implications for research, as the study methods need to be sufficiently flexible to account for changes or adaptations in what is actually being implemented. 8 11 Research designs that depend on having a single and fixed intervention, such as a typical randomised controlled trial, would not be an appropriate design to study phenomena that change, especially when they change in unpredictable and variable ways.

Another implication of studying complex systems is that the research may need to use multiple methods and different sources of information to understand an implementation problem. Because implementation activities and effects are not usually static or linear processes, research designs often need to be able to observe and analyse these sometimes iterative and changing elements at several points in time and to consider unintended consequences.

Implementation research questions

As in other types of health systems research, the research question is the king in implementation research. Implementation research takes a pragmatic approach, placing the research question (or implementation problem) as the starting point to inquiry; this then dictates the research methods and assumptions to be used. Implementation research questions can cover a wide variety of topics and are frequently organised around theories of change or the type of research objective (examples are in supplementary table C). 12 13

Implementation research can overlap with other types of research used in medicine and public health, and the distinctions are not always clear cut. A range of implementation research exists, based on the centrality of implementation in the research question, the degree to which the research takes place in a real world setting with routine populations, and the role of implementation strategies and implementation variables in the research (figure ⇓ ).

Spectrum of implementation research 33

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

A more detailed description of the research question can help researchers and practitioners to determine the type of research methods that should be used. In table 2 ⇓ , we break down the research question first by its objective: to explore, describe, influence, explain, or predict. This is followed by a typical implementation research question based on each objective. Finally, we describe a set of research methods for each type of research question.

Type of implementation research objective, implementation question, and research methods

Much of evidence based medicine is concerned with the objective of influence, or whether an intervention produces an expected outcome, which can be broken down further by the level of certainty in the conclusions drawn from the study. The nature of the inquiry (for example, the amount of risk and considerations of ethics, costs, and timeliness), and the interests of different audiences, should determine the level of uncertainty. 8 14 Research questions concerning programmatic decisions about the process of an implementation strategy may justify a lower level of certainty for the manager and policy maker, using research methods that would support an adequacy or plausibility inference. 14 Where a high risk of harm exists and sufficient time and resources are available, a probability study design might be more appropriate, in which the result in an area where the intervention is implemented is compared with areas without implementation with a low probability of error (for example, P< 0.05). These differences in the level of confidence affect the study design in terms of sample size and the need for concurrent or randomised comparison groups. 8 14

Implementation specific research methods

A wide range of qualitative and quantitative research methods can be used in implementation research (table 2 ⇑ ). The box gives a set of basic questions to guide the design or reporting of implementation research that can be used across methods. More in-depth criteria have also been proposed to assess the external validity or generalisability of findings. 15 Some research methods have been developed specifically to deal with implementation research questions or are particularly suitable to implementation research, as identified below.

Key questions to assess research designs or reports on implementation research 33

Does the research clearly aim to answer a question concerning implementation?

Does the research clearly identify the primary audiences for the research and how they would use the research?

Is there a clear description of what is being implemented (for example, details of the practice, programme, or policy)?

Does the research involve an implementation strategy? If so, is it described and examined in its fullness?

Is the research conducted in a “real world” setting? If so, is the context and sample population described in sufficient detail?

Does the research appropriately consider implementation outcome variables?

Does the research appropriately consider context and other factors that influence implementation?

Does the research appropriately consider changes over time and the level of complexity of the system, including unintended consequences?

Pragmatic trials

Pragmatic trials, or practical trials, are randomised controlled trials in which the main research question focuses on effectiveness of an intervention in a normal practice setting with the full range of study participants. 16 This may include pragmatic trials on new healthcare delivery strategies, such as integrated chronic care clinics or nurse run community clinics. This contrasts with typical randomised controlled trials that look at the efficacy of an intervention in an “ideal” or controlled setting and with highly selected patients and standardised clinical outcomes, usually of a short term nature.

Effectiveness-implementation hybrid trials

Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs are intended to assess the effectiveness of both an intervention and an implementation strategy. 7 These studies include components of an effectiveness design (for example, randomised allocation to intervention and comparison arms) but add the testing of an implementation strategy, which may also be randomised. This might include testing the effectiveness of a package of delivery and postnatal care in under-served areas, as well testing several strategies for providing the care. Whereas pragmatic trials try to fix the intervention under study, effectiveness-implementation hybrids also intervene and/or observe the implementation process as it actually occurs. This can be done by assessing implementation outcome variables.

Quality improvement studies

Quality improvement studies typically involve a set of structured and cyclical processes, often called the plan-do-study-act cycle, and apply scientific methods on a continuous basis to formulate a plan, implement the plan, and analyse and interpret the results, followed by an iteration of what to do next. 17 18 The focus might be on a clinical process, such as how to reduce hospital acquired infections in the intensive care unit, or management processes such as how to reduce waiting times in the emergency room. Guidelines exist on how to design and report such research—the Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE). 17

Speroff and O’Connor describe a range of plan-do-study-act research designs, noting that they have in common the assessment of responses measured repeatedly and regularly over time, either in a single case or with comparison groups. 18 Balanced scorecards integrate performance measures across a range of domains and feed into regular decision making. 19 20 Standardised guidance for using good quality health information systems and health facility surveys has been developed and often provides the sources of information for these quasi-experimental designs. 21 22 23

Participatory action research

Participatory action research refers to a range of research methods that emphasise participation and action (that is, implementation), using methods that involve iterative processes of reflection and action, “carried out with and by local people rather than on them.” 24 In participatory action research, a distinguishing feature is that the power and control over the process rests with the participants themselves. Although most participatory action methods involve qualitative methods, quantitative and mixed methods techniques are increasingly being used, such as for participatory rural appraisal or participatory statistics. 25 26

Mixed methods

Mixed methods research uses both qualitative and quantitative methods of data collection and analysis in the same study. Although not designed specifically for implementation research, mixed methods are particularly suitable because they provide a practical way to understand multiple perspectives, different types of causal pathways, and multiple types of outcomes—all common features of implementation research problems.

Many different schemes exist for describing different types of mixed methods research, on the basis of the emphasis of the study, the sampling schemes for the different components, the timing and sequencing of the qualitative and quantitative methods, and the level of mixing between the qualitative and quantitative methods. 27 28 Broad guidance on the design and conduct of mixed methods designs is available. 29 30 31 A scheme for good reporting of mixed methods studies involves describing the justification for using a mixed methods approach to the research question; describing the design in terms of the purpose, priority, and sequence of methods; describing each method in terms of sampling, data collection, and analysis; describing where the integration has occurred, how it has occurred, and who has participated in it; describing any limitation of one method associated with the presence of the other method; and describing any insights gained from mixing or integrating methods. 32

Implementation research aims to cover a wide set of research questions, implementation outcome variables, factors affecting implementation, and implementation strategies. This paper has identified a range of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods that can be used according to the specific research question, as well as several research designs that are particularly suited to implementation research. Further details of these concepts can be found in a new guide developed by the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research. 33

Summary points

Implementation research has its origins in many disciplines and is usefully defined as scientific inquiry into questions concerning implementation—the act of fulfilling or carrying out an intention

In health research, these intentions can be policies, programmes, or individual practices (collectively called interventions)

Implementation research seeks to understand and work in “real world” or usual practice settings, paying particular attention to the audience that will use the research, the context in which implementation occurs, and the factors that influence implementation

A wide variety of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods techniques can be used in implementation research, which are best selected on the basis of the research objective and specific questions related to what, why, and how interventions work

Implementation research may examine strategies that are specifically designed to improve the carrying out of health interventions or assess variables that are defined as implementation outcomes

Implementation outcomes include acceptability, adoption, appropriateness, feasibility, fidelity, implementation cost, coverage, and sustainability

Cite this as: BMJ 2013;347:f6753

Contributors: All authors contributed to the conception and design, analysis and interpretation, drafting the article, or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and all gave final approval of the version to be published. NT had the original idea for the article, which was discussed by the authors (except OA) as well as George Pariyo, Jim Sherry, and Dena Javadi at a meeting at the World Health Organization (WHO). DHP and OA did the literature reviews, and DHP wrote the original outline and the draft manuscript, tables, and boxes. OA prepared the original figure. All authors reviewed the draft article and made substantial revisions to the manuscript. DHP is the guarantor.

Funding: Funding was provided by the governments of Norway and Sweden and the UK Department for International Development (DFID) in support of the WHO Implementation Research Platform, which financed a meeting of authors and salary support for NT. DHP is supported by the Future Health Systems research programme consortium, funded by DFID for the benefit of developing countries (grant number H050474). The funders played no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of the research.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare: support for the submitted work as described above; NT and TA are employees of the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research at WHO, which is supporting their salaries to work on implementation research; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Invited by journal; commissioned by WHO; externally peer reviewed.

- ↵ Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK, eds. Dissemination and implementation research in health: translating science to practice. Oxford University Press, 2012.

- ↵ Ciliska D, Robinson P, Armour T, Ellis P, Brouwers M, Gauld M, et al. Diffusion and dissemination of evidence-based dietary strategies for the prevention of cancer. Nutr J 2005 ; 4 (1): 13 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Remme JHF, Adam T, Becerra-Posada F, D’Arcangues C, Devlin M, Gardner C, et al. Defining research to improve health systems. PLoS Med 2010 ; 7 : e1001000 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ McKibbon KA, Lokker C, Mathew D. Implementation research. 2012. http://whatiskt.wikispaces.com/Implementation+Research .

- ↵ The compact edition of the Oxford English dictionary. Oxford University Press, 1971.

- ↵ Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health 2010 ; 38 : 65 -76. OpenUrl

- ↵ Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care 2012 ; 50 : 217 -26. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Peters DH, El-Saharty S, Siadat B, Janovsky K, Vujicic M, eds. Improving health services in developing countries: from evidence to action. World Bank, 2009.

- ↵ Sabatier PA. Top-down and bottom-up approaches to implementation research. J Public Policy 1986 ; 6 (1): 21 -48. OpenUrl CrossRef

- ↵ Paina L, Peters DH. Understanding pathways for scaling up health services through the lens of complex adaptive systems. Health Policy Plan 2012 ; 27 : 365 -73. OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Gilson L, ed. Health policy and systems research: a methodology reader. World Health Organization, 2012.

- ↵ Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers DA, Brownson RC. Bridging research and practice: models for dissemination and implementation research. Am J Prev Med 2012 ; 43 : 337 -50. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Improved Clinical Effectiveness through Behavioural Research Group (ICEBeRG). Designing theoretically-informed implementation interventions. Implement Sci 2006 ; 1 : 4 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Habicht JP, Victora CG, Vaughn JP. Evaluation designs for adequacy, plausibility, and probability of public health programme performance and impact. Int J Epidemiol 1999 ; 28 : 10 -8. OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Green LW, Glasgow RE. Evaluating the relevance, generalization, and applicability of research. Eval Health Prof 2006 ; 29 : 126 -53. OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Swarenstein M, Treweek S, Gagnier JJ, Altman DG, Tunis S, Haynes B, et al, for the CONSORT and Pragmatic Trials in Healthcare (Practihc) Groups. Improving the reporting of pragmatic trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. BMJ 2008 ; 337 : a2390 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Davidoff F, Batalden P, Stevens D, Ogrince G, Mooney SE, for the SQUIRE Development Group. Publication guidelines for quality improvement in health care: evolution of the SQUIRE project. Qual Saf Health Care 2008 ; 17 (suppl I): i3 -9. OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Speroff T, O’Connor GT. Study designs for PDSA quality improvement research. Q Manage Health Care 2004 ; 13 (1): 17 -32. OpenUrl CrossRef

- ↵ Peters DH, Noor AA, Singh LP, Kakar FK, Hansen PM, Burnham G. A balanced scorecard for health services in Afghanistan. Bull World Health Organ 2007 ; 85 : 146 -51. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Edward A, Kumar B, Kakar F, Salehi AS, Burnham G. Peters DH. Configuring balanced scorecards for measuring health systems performance: evidence from five years’ evaluation in Afghanistan. PLOS Med 2011 ; 7 : e1001066 . OpenUrl

- ↵ Health Facility Assessment Technical Working Group. Profiles of health facility assessment method, MEASURE Evaluation, USAID, 2008.

- ↵ Hotchkiss D, Diana M, Foreit K. How can routine health information systems improve health systems functioning in low-resource settings? Assessing the evidence base. MEASURE Evaluation, USAID, 2012.

- ↵ Lindelow M, Wagstaff A. Assessment of health facility performance: an introduction to data and measurement issues. In: Amin S, Das J, Goldstein M, eds. Are you being served? New tools for measuring service delivery. World Bank, 2008:19-66.

- ↵ Cornwall A, Jewkes R. “What is participatory research?” Soc Sci Med 1995 ; 41 : 1667 -76. OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed Web of Science

- ↵ Mergler D. Worker participation in occupational health research: theory and practice. Int J Health Serv 1987 ; 17 : 151 . OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Chambers R. Revolutions in development inquiry. Earthscan, 2008.

- ↵ Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Sage Publications, 2011.

- ↵ Tashakkori A, Teddlie C. Mixed methodology: combining qualitative and quantitative approaches. Sage Publications, 2003.

- ↵ Leech NL, Onwuegbuzie AJ. Guidelines for conducting and reporting mixed research in the field of counseling and beyond. Journal of Counseling and Development 2010 ; 88 : 61 -9. OpenUrl CrossRef Web of Science

- ↵ Creswell JW. Mixed methods procedures. In: Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. 3rd ed. Sage Publications, 2009.

- ↵ Creswell JW, Klassen AC, Plano Clark VL, Clegg Smith K. Best practices for mixed methods research in the health sciences. National Institutes of Health, Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, 2011.

- ↵ O’Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. The quality of mixed methods studies in health services research. J Health Serv Res Policy 2008 ; 13 : 92 -8. OpenUrl Abstract / FREE Full Text

- ↵ Peters DH, Tran N, Adam T, Ghaffar A. Implementation research in health: a practical guide. Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, World Health Organization, 2013.

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 5th ed. Free Press, 2003.

- Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, Booth A, Rick J, Balain S. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement Sci 2007 ; 2 : 40 . OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- Victora CG, Schellenberg JA, Huicho L, Amaral J, El Arifeen S, Pariyo G, et al. Context matters: interpreting impact findings in child survival evaluations. Health Policy Plan 2005 ; 20 (suppl 1): i18 -31. OpenUrl Abstract

- Open access

- Published: 25 September 2020

The Implementation Research Logic Model: a method for planning, executing, reporting, and synthesizing implementation projects

- Justin D. Smith ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3264-8082 1 , 2 ,

- Dennis H. Li 3 &

- Miriam R. Rafferty 4

Implementation Science volume 15 , Article number: 84 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

88k Accesses

192 Citations

83 Altmetric

Metrics details

A Letter to the Editor to this article was published on 17 November 2021

Numerous models, frameworks, and theories exist for specific aspects of implementation research, including for determinants, strategies, and outcomes. However, implementation research projects often fail to provide a coherent rationale or justification for how these aspects are selected and tested in relation to one another. Despite this need to better specify the conceptual linkages between the core elements involved in projects, few tools or methods have been developed to aid in this task. The Implementation Research Logic Model (IRLM) was created for this purpose and to enhance the rigor and transparency of describing the often-complex processes of improving the adoption of evidence-based interventions in healthcare delivery systems.

The IRLM structure and guiding principles were developed through a series of preliminary activities with multiple investigators representing diverse implementation research projects in terms of contexts, research designs, and implementation strategies being evaluated. The utility of the IRLM was evaluated in the course of a 2-day training to over 130 implementation researchers and healthcare delivery system partners.

Preliminary work with the IRLM produced a core structure and multiple variations for common implementation research designs and situations, as well as guiding principles and suggestions for use. Results of the survey indicated a high utility of the IRLM for multiple purposes, such as improving rigor and reproducibility of projects; serving as a “roadmap” for how the project is to be carried out; clearly reporting and specifying how the project is to be conducted; and understanding the connections between determinants, strategies, mechanisms, and outcomes for their project.

Conclusions

The IRLM is a semi-structured, principle-guided tool designed to improve the specification, rigor, reproducibility, and testable causal pathways involved in implementation research projects. The IRLM can also aid implementation researchers and implementation partners in the planning and execution of practice change initiatives. Adaptation and refinement of the IRLM are ongoing, as is the development of resources for use and applications to diverse projects, to address the challenges of this complex scientific field.

Peer Review reports

Contributions to the literature

Drawing from and integrating existing frameworks, models, and theories, the IRLM advances the traditional logic model for the requirements of implementation research and practice.

The IRLM provides a means of describing the complex relationships between critical elements of implementation research and practice in a way that can be used to improve the rigor and reproducibility of research and implementation practice, and the testing of theory.

The IRLM offers researchers and partners a useful tool for the purposes of planning, executing, reporting, and synthesizing processes and findings across the stages of implementation projects.

In response to a call for addressing noted problems with transparency, rigor, openness, and reproducibility in biomedical research [ 1 ], the National Institutes of Health issued guidance in 2014 pertaining to the research it funds ( https://www.nih.gov/research-training/rigor-reproducibility ). The field of implementation science has similarly recognized a need for better specification with similar intent [ 2 ]. However, integrating the necessary conceptual elements of implementation research, which often involves multiple models, frameworks, and theories, is an ongoing challenge. A conceptually grounded organizational tool could improve rigor and reproducibility of implementation research while offering additional utility for the field.

This article describes the development and application of the Implementation Research Logic Model (IRLM). The IRLM can be used with various types of implementation studies and at various stages of research, from planning and executing to reporting and synthesizing implementation studies. Example IRLMs are provided for various common study designs and scenarios, including hybrid designs and studies involving multiple service delivery systems [ 3 , 4 ]. Last, we describe the preliminary use of the IRLM and provide results from a post-training evaluation. An earlier version of this work was presented at the 2018 AcademyHealth/NIH Conference on the Science of Dissemination and Implementation in Health, and the abstract appeared in the Implementation Science [ 5 ].

Specification challenges in implementation research

Having an imprecise understanding of what was done and why during the implementation of a new innovation obfuscates identifying the factors responsible for successful implementation and prevents learning from what contributed to failed implementation. Thus, improving the specification of phenomena in implementation research is necessary to inform our understanding of how implementation strategies work, for whom, under what determinant conditions, and on what implementation and clinical outcomes. One challenge is that implementation science uses numerous models and frameworks (hereafter, “frameworks”) to describe, organize, and aid in understanding the complexity of changing practice patterns and integrating evidence-based health interventions across systems [ 6 ]. These frameworks typically address implementation determinants, implementation process, or implementation evaluation [ 7 ]. Although many frameworks incorporate two or more of these broad purposes, researchers often find it necessary to use more than one to describe the various aspects of an implementation research study. The conceptual connections and relationships between multiple frameworks are often difficult to describe and to link to theory [ 8 ].

Similarly, reporting guidelines exist for some of these implementation research components, such as strategies [ 9 ] and outcomes [ 10 ], as well as for entire studies (i.e., Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies [ 11 ]); however, they generally help describe the individual components and not their interactions. To facilitate causal modeling [ 12 ], which can be used to elucidate mechanisms of change and the processes involved in both successful and unsuccessful implementation research projects, investigators must clearly define the relations among variables in ways that are testable with research studies [ 13 ]. Only then can we open the “black box” of how specific implementation strategies operate to predict outcomes.

- Logic models

Logic models, graphic depictions that present the shared relationships among various elements of a program or study, have been used for decades in program development and evaluation [ 14 ] and are often required by funding agencies when proposing studies involving implementation [ 15 ]. Used to develop agreement among diverse stakeholders of the “what” and the “how” of proposed and ongoing projects, logic models have been shown to improve planning by highlighting theoretical and practical gaps, support the development of meaningful process indicators for tracking, and aid in both reproducing successful studies and identifying failures of unsuccessful studies [ 16 ]. They are also useful at other stages of research and for program implementation, such as organizing a project/grant application/study protocol, presenting findings from a completed project, and synthesizing the findings of multiple projects [ 17 ].

Logic models can also be used in the context of program theory, an explicit statement of how a project/strategy/intervention/program/policy is understood to contribute to a chain of intermediate results that eventually produce the intended/observed impacts [ 18 ]. Program theory specifies both a Theory of Change (i.e., the central processes or drivers by which change comes about following a formal theory or tacit understanding) and a Theory of Action (i.e., how program components are constructed to activate the Theory of Change) [ 16 ]. Inherent within program theory is causal chain modeling. In implementation research, Fernandez et al. [ 19 ] applied mapping methods to implementation strategies to postulate the ways in which changes to the system affect downstream implementation and clinical outcomes. Their work presents an implementation mapping logic model based on Proctor et al. [ 20 , 21 ], which is focused primarily on the selection of implementation strategy(s) rather than a complete depiction of the conceptual model linking all implementation research elements (i.e., determinants, strategies, mechanisms of action, implementation outcomes, clinical outcomes) in the detailed manner we describe in this article.

Development of the IRLM

The IRLM began out of a recognition that implementation research presents some unique challenges due to the field’s distinct and still codifying terminology [ 22 ] and its use of implementation-specific and non-specific (borrowed from other fields) theories, models, and frameworks [ 7 ]. The development of the IRLM occurred through a series of case applications. This began with a collaboration between investigators at Northwestern University and the Shirley Ryan AbilityLab in which the IRLM was used to study the implementation of a new model of patient care in a new hospital and in other related projects [ 23 ]. Next, the IRLM was used with three already-funded implementation research projects to plan for and describe the prospective aspects of the trials, as well as with an ongoing randomized roll-out implementation trial of the Collaborative Care Model for depression management [Smith JD, Fu E, Carroll AJ, Rado J, Rosenthal LJ, Atlas JA, Burnett-Zeigler I, Carlo, A, Jordan N, Brown CH, Csernansky J: Collaborative care for depression management in primary care: a randomized rollout trial using a type 2 hybrid effectiveness-implementation design submitted for publication]. It was also applied in the later stages of a nearly completed implementation research project of a family-based obesity management intervention in pediatric primary care to describe what had occurred over the course of the 3-year trial [ 24 ]. Last, the IRLM was used as a training tool in a 2-day training with 63 grantees of NIH-funded planning project grants funded as part of the Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative [ 25 ]. Results from a survey of the participants in the training are reported in the “Results” section. From these preliminary activities, we identified a number of ways that the IRLM could be used, described in the section on “Using the IRLM for different purposes and stages of research.”

The Implementation Research Logic Model

In developing the IRLM, we began with the common “pipeline” logic model format used by AHRQ, CDC, NIH, PCORI, and others [ 16 ]. This structure was chosen due to its familiarity with funders, investigators, readers, and reviewers. Although a number of characteristics of the pipeline logic model can be applied to implementation research studies, there is an overall misfit due to implementation research’s focusing on the systems that support adoption and delivery of health practices; involving multiple levels within one or more systems; and having its own unique terminology and frameworks [ 3 , 22 , 26 ]. We adapted the typical evaluation logic model to integrate existing implementation science frameworks as its core elements while keeping to the same aim of facilitating causal modeling.

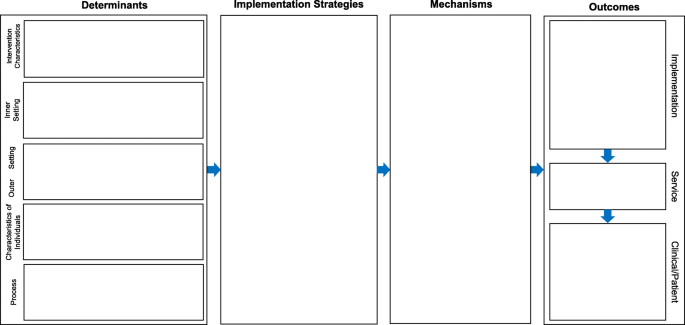

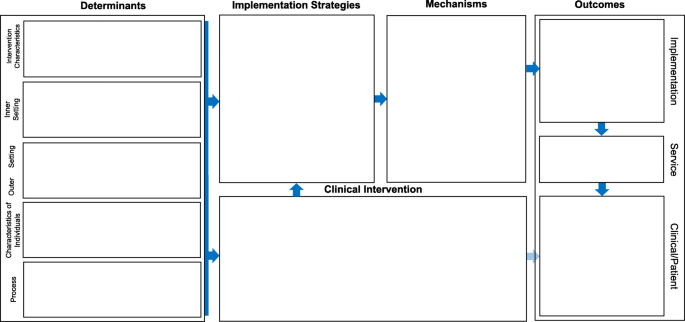

The most common IRLM format is depicted in Fig. 1 . Additional File A1 is a Fillable PDF version of Fig. 1 . In certain situations, it might be preferable to include the evidence-based intervention (EBI; defined as a clinical, preventive, or educational protocol or a policy, principle, or practice whose effects are supported by research [ 27 ]) (Fig. 2 ) to demonstrate alignment of contextual factors (determinants) and strategies with the components and characteristics of the clinical intervention/policy/program and to disentangle it from the implementation strategies. Foremost in these indications are “home-grown” interventions, whose components and theory of change may not have been previously described, and novel interventions that are early in the translational pipeline, which may require greater detail for the reader/reviewer. Variant formats are provided as Additional Files A 2 to A 4 for use with situations and study designs commonly encountered in implementation research, including comparative implementation studies (A 2 ), studies involving multiple service contexts (A 3 ), and implementation optimization designs (A 4 ). Further, three illustrative IRLMs are provided, with brief descriptions of the projects and the utility of the IRLM (A 5 , A 6 and A 7 ).

Implementation Research Logic Model (IRLM) Standard Form. Notes. Domain names in the determinants section were drawn from the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. The format of the outcomes column is from Proctor et al. 2011

Implementation Research Logic Model (IRLM) Standard Form with Intervention. Notes. Domain names in the determinants section were drawn from the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. The format of the outcomes column is from Proctor et al. 2011

Core elements and theory

The IRLM specifies the relationships between determinants of implementation, implementation strategies, the mechanisms of action resulting from the strategies, and the implementation and clinical outcomes affected. These core elements are germane to every implementation research project in some way. Accordingly, the generalized theory of the IRLM posits that (1) implementation strategies selected for a given EBI are related to implementation determinants (context-specific barriers and facilitators), (2) strategies work through specific mechanisms of action to change the context or the behaviors of those within the context, and (3) implementation outcomes are the proximal impacts of the strategy and its mechanisms, which then relate to the clinical outcomes of the EBI. Articulated in part by others [ 9 , 12 , 21 , 28 , 29 ], this causal pathway theory is largely explanatory and details the Theory of Change and the Theory of Action of the implementation strategies in a single model. The EBI Theory of Action can also be displayed within a modified IRLM (see Additional File A 4 ). We now briefly describe the core elements and discuss conceptual challenges in how they relate to one another and to the overall goals of implementation research.

Determinants

Determinants of implementation are factors that might prevent or enable implementation (i.e., barriers and facilitators). Determinants may act as moderators, “effect modifiers,” or mediators, thus indicating that they are links in a chain of causal mechanisms [ 12 ]. Common determinant frameworks are the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [ 30 ] and the Theoretical Domains Framework [ 31 ].

Implementation strategies

Implementation strategies are supports, changes to, and interventions on the system to increase adoption of EBIs into usual care [ 32 ]. Consideration of determinants is commonly used when selecting and tailoring implementation strategies [ 28 , 29 , 33 ]. Providing the theoretical or conceptual reasoning for strategy selection is recommended [ 9 ]. The IRLM can be used to specify the proposed relationships between strategies and the other elements (determinants, mechanisms, and outcomes) and assists with considering, planning, and reporting all strategies in place during an implementation research project that could contribute to the outcomes and resulting changes

Because implementation research occurs within dynamic delivery systems with multiple factors that determine success or failure, the field has experienced challenges identifying consistent links between individual barriers and specific strategies to overcome them. For example, the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) compilation of strategies [ 32 ] was used to determine which strategies would best address contextual barriers identified by CFIR [ 29 ]. An online CFIR–ERIC matching process completed by implementation researchers and practitioners resulted in a large degree of heterogeneity and few consistent relationships between barrier and strategy, meaning the relationship is rarely one-to-one (e.g., a single strategy is often is linked to multiple barriers; more than one strategy needed to address a single barrier). Moreover, when implementation outcomes are considered, researchers often find that to improve one outcome, more than one contextual barrier needs to be addressed, which might in turn require one or more strategies.

Frequently, the reporting of implementation research studies focuses on the strategy or strategies that were introduced for the research study, without due attention to other strategies already used in the system or additional supporting strategies that might be needed to implement the target strategy. The IRLM allows for the comprehensive specification of all introduced and present strategies, as well as their changes (adaptations, additions, discontinuations) during the project.

Mechanisms of action

Mechanisms of action are processes or events through which an implementation strategy operates to affect desired implementation outcomes [ 12 ]. The mechanism can be a change in a determinant, a proximal implementation outcome, an aspect of the implementation strategy itself, or a combination of these in a multiple-intervening-effect model. An example of a causal process might be using training and fidelity monitoring strategies to improve delivery agents’ knowledge and self-efficacy about the EBI in response to knowledge-related barriers in the service delivery system. This could result in raising their acceptability of the EBI, increase the likelihood of adoption, improve the fidelity of delivery, and lead to sustainment. Relatively, few implementation studies formally test mechanisms of action, but this area of investigation has received significant attention more recently as the necessity to understand how strategies operate grows in the field [ 33 , 34 , 35 ].

Implementation outcomes are the effects of deliberate and purposive actions to implement new treatments, practices, and services [ 21 ]. They can be indicators of implementation processes, or key intermediate outcomes in relation to service, or target clinical outcomes. Glasgow et al. [ 36 , 37 , 38 ] describe the interrelated nature of implementation outcomes as occurring in a logical, but not necessarily linear, sequence of adoption by a delivery agent, delivery of the innovation with fidelity, reach of the innovation to the intended population, and sustainment of the innovation over time. The combined impact of these nested outcomes, coupled with the size of the effect of the EBI, determines the population or public health impact of implementation [ 36 ]. Outcomes earlier in the sequence can be conceptualized as mediators and mechanisms of strategies on later implementation outcomes. Specifying which strategies are theoretically intended to affect which outcomes, through which mechanisms of action, is crucial for improving the rigor and reproducibility of implementation research and to testing theory.

Using the Implementation Research Logic Model

Guiding principles.

One of the critical insights from our preliminary work was that the use of the IRLM should be guided by a set of principles rather than governed by rules. These principles are intended to be flexible both to allow for adaptation to the various types of implementation studies and evolution of the IRLM over time and to address concerns in the field of implementation science regarding specification, rigor, reproducibility, and transparency of design and process [ 5 ]. Given this flexibility of use, the IRLM will invariably require accompanying text and other supporting documents. These are described in the section “Use of Supporting Text and Documents.”

Principle 1: Strive for comprehensiveness

Comprehensiveness increases transparency, can improve rigor, and allows for a better understanding of alternative explanations to the conclusions drawn, particularly in the presence of null findings for an experimental design. Thus, all relevant determinants, implementation strategies, and outcomes should be included in the IRLM.

Concerning determinants, the valence should be noted as being either a barrier, a facilitator, neutral, or variable by study unit. This can be achieved by simply adding plus (+) or minus (–) signs for facilitators and barriers, respectively, or by using coding systems such as that developed by Damschroder et al. [ 39 ], which indicates the relative strength of the determinant on a scale: – 2 ( strong negative impact ), – 1 ( weak negative impact ), 0 ( neutral or mixed influence ), 1 ( weak positive impact ), and 2 ( strong positive impact ). The use of such a coding system could yield better specification compared to using study-specific adjectives or changing the name of the determinant (e.g., greater relative priority, addresses patient needs, good climate for implementation). It is critical to include all relevant determinants and not simply limit reporting to those that are hypothesized to be related to the strategies and outcomes, as there are complex interrelationships between determinants.

Implementation strategies should be reported in their entirety. When using the IRLM for planning a study, it is important to list all strategies in the system, including those already in use and those to be initiated for the purposes of the study, often in the experimental condition of the design. Second, strategies should be labeled to indicate whether they were (a) in place in the system prior to the study, (b) initiated prospectively for the purposes of the study (particularly for experimental study designs), (c) removed as a result of being ineffective or onerous, or (d) introduced during the study to address an emergent barrier or supplement other strategies because of low initial impact. This is relevant when using the IRLM for planning, as an ongoing tracking system, for retrospective application to a completed study, and in the final reporting of a study. There have been a number of processes proposed for tracking the use of and adaptations to implementation strategies over time [ 40 , 41 ]. Each of these is more detailed than would be necessary for the IRLM, but the processes described provide a method for accurately tracking the temporal aspects of strategy use that fulfill the comprehensiveness principle.

Although most studies will indicate a primary implementation outcome, other outcomes are almost assuredly to be measured. Thus, they ought to be included in the IRLM. This guidance is given in large part due to the interdependence of implementation outcomes, such that adoption relates to delivery with fidelity, reach of the intervention, and potential for sustainment [ 36 ]. Similarly, the overall public health impact (defined as reach multiplied by the effect size of the intervention [ 38 ]) is inextricably tied to adoption, fidelity, acceptability, cost, etc. Although the study might justifiably focus on only one or two implementation outcomes, the others are nonetheless relevant and should be specified and reported. For example, it is important to capture potential unintended consequences and indicators of adverse effects that could result from the implementation of an EBI.

Principle 2: Indicate key conceptual relationships

Although the IRLM has a generalized theory (described earlier), there is a need to indicate the relationships between elements in a manner aligning with the specific theory of change for the study. Researchers ought to provide some form or notation to indicate these conceptual relationships using color-coding, superscripts, arrows, or a combination of the three. Such notations in the IRLM facilitate reference in the text to the study hypotheses, tests of effects, causal chain modeling, and other forms of elaboration (see “Supporting Text and Resources”). We prefer the use of superscripts to color or arrows in grant proposals and articles for practical purposes, as colors can be difficult to distinguish, and arrows can obscure text and contribute to visual convolution. When presenting the IRLM using presentation programs (e.g., PowerPoint, Keynote), colors and arrows can be helpful, and animations can make these connections dynamic and sequential without adding to visual complexity. This principle could also prove useful in synthesizing across similar studies to build the science of tailored implementation, where strategies are selected based on the presence of specific combinations of determinants. As previously indicated [ 29 ], there is much work to be done in this area given.

Principle 3: Specify critical study design elements

This critical element will vary by the study design (e.g., hybrid effectiveness-implementation trial, observational, what subsystems are assigned to the strategies). This principle includes not only researchers but service systems and communities, whose consent is necessary to carry out any implementation design [ 3 , 42 , 43 ].

Primary outcome(s)

Indicate the primary outcome(s) at each level of the study design (i.e., clinician, clinic, organization, county, state, nation). The levels should align with the specific aims of a grant application or the stated objective of a research report. In the case of a process evaluation or an observational study including the RE-AIM evaluation components [ 38 ] or the Proctor et al. [ 21 ] taxonomy of implementation outcomes, the primary outcome may be the product of the conceptual or theoretical model used when a priori outcomes are not clearly indicated. We also suggest including downstream health services and clinical outcomes even if they are not measured, as these are important for understanding the logic of the study and the ultimate health-related targets.

For quasi/experimental designs

When quasi/experimental designs [ 3 , 4 ] are used, the independent variable(s) (i.e., the strategies that are introduced or manipulated or that otherwise differentiate study conditions) should be clearly labeled. This is important for internal validity and for differentiating conditions in multi-arm studies.

For comparative implementation trials

In the context of comparative implementation trials [ 3 , 4 ], a study of two or more competing implementation strategies are introduced for the purposes of the study (i.e., the comparison is not implementation-as-usual), and there is a need to indicate the determinants, strategies, mechanisms, and potentially outcomes that differentiate the arms (see Additional File A 2 ). As comparative implementation can involve multiple service delivery systems, the determinants, mechanisms, and outcomes might also differ, though there must be at least one comparable implementation outcome. In our preliminary work applying the IRLM to a large-scale comparative implementation trial, we found that we needed to use an IRLM for each arm of the trial as it was not possible to use a single IRLM because the strategies being tested occurred across two delivery systems and strategies were very different, by design. This is an example of the flexible use of the IRLM.

For implementation optimization designs

A number of designs are now available that aim to test processes of optimizing implementation. These include factorial, Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trial (SMART) [ 44 ], adaptive [ 45 ], and roll-out implementation optimization designs [ 46 ]. These designs allow for (a) building time-varying adaptive implementation strategies based on the order in which components are presented [ 44 ], (b) evaluating the additive and combined effects of multiple strategies [ 44 , 47 ], and (c) can incorporate data-driven iterative changes to improve implementation in successive units [ 45 , 46 ]. The IRLM in Additional File A 4 can be used for such designs.

Additional specification options

Users of the IRLM are allowed to specify any number of additional elements that may be important to their study. For example, one could notate those elements of the IRLM that have been or will be measured versus those that were based on the researcher’s prior studies or inferred from findings reported in the literature. Users can also indicate when implementation strategies differ by level or unit within the study. In large multisite studies, strategies might not be uniform across all units, particularly those strategies that already exist within the system. Similarly, there might be a need to increase the dose of certain strategies to address the relative strengths of different determinants within units.

Using the IRLM for different purposes and stages of research

Commensurate with logic models more generally, the IRLM can be used for planning and organizing a project, carrying out a project (as a roadmap), reporting and presenting the findings of a completed project, and synthesizing the findings of multiple projects or of a specific area of implementation research, such as what is known about how learning collaboratives are effective within clinical care settings.

When the IRLM is used for planning, the process of populating each of the elements often begins with the known parameter(s) of the study. For example, if the problem is improving the adoption and reach of a specific EBI within a particular clinical setting, the implementation outcomes and context, as well as the EBI, are clearly known. The downstream clinical outcomes of the EBI are likely also known. Working from the two “bookends” of the IRLM, the researchers and community partners and/or organization stakeholders can begin to fill in the implementation strategies that are likely to be feasible and effective and then posit conceptually derived mechanisms of action. In another example, only the EBI and primary clinical outcomes were known. The IRLM was useful in considering different scenarios for what strategies might be needed and appropriate to test the implementation of the EBI in different service delivery contexts. The IRLM was a tool for the researchers and stakeholders to work through these multiple options.

When we used the IRLM to plan for the execution of funded implementation studies, the majority of the parameters were already proposed in the grant application. However, through completing the IRLM prior to the start of the study, we found that a number of important contextual factors had not been considered, additional implementation strategies were needed to complement the primary ones proposed in the grant, and mechanisms needed to be added and measured. At the time of award, mechanisms were not an expected component of implementation research projects as they will likely become in the future.

For another project, the IRLM was applied retrospectively to report on the findings and overall logic of the study. Because nearly all elements of the IRLM were known, we approached completion of the model as a means of showing what happened during the study and to accurately report the hypothesized relationships that we observed. These relationships could be formally tested using causal pathway modeling [ 12 ] or other path analysis approaches with one or more intervening variables [ 48 ].

Synthesizing

In our preliminary work with the IRLM, we used it in each of the first three ways; the fourth (synthesizing) is ongoing within the National Cancer Institute’s Improving the Management of symPtoms during And Following Cancer Treatment (IMPACT) research consortium. The purpose is to draw conclusions for the implementation of an EBI in a particular context (or across contexts) that are shared and generalizable to provide a guide for future research and implementation.

Use of supporting text and documents

While the IRLM provides a good deal of information about a project in a single visual, researchers will need to convey additional details about an implementation research study through the use of supporting text, tables, and figures in grant applications, reports, and articles. Some elements that require elaboration are (a) preliminary data on the assessment and valence of implementation determinants; (b) operationalization/detailing of the implementation strategies being used or observed, using established reporting guidelines [ 9 ] and labeling conventions [ 32 ] from the literature; (c) hypothesized or tested causal pathways [ 12 ]; (d) process, service, and clinical outcome measures, including the psychometric properties, method, and timing of administration, respondents, etc.; (e) study procedures, including subject selection, assignment to (or observation of natural) study conditions, and assessment throughout the conduct of the study [ 4 ]; and (f) the implementation plan or process for following established implementation frameworks [ 49 , 50 , 51 ]. By utilizing superscripts, subscripts, and other notations within the IRLM, as previously suggested, it is easy to refer to (a) hypothesized causal paths in theoretical overviews and analytic plan sections, (b) planned measures for determinants and outcomes, and (c) specific implementation strategies in text, tables, and figures.

Evidence of IRLM utility and acceptability

The IRLM was used as the foundation for a training in implementation research methods to a group of 65 planning projects awarded under the national Ending the HIV Epidemic initiative. One investigator (project director or co-investigator) and one implementation partner (i.e., a collaborator from a community service delivery system) from each project were invited to attend a 2-day in-person summit in Chicago, IL, in October 2019. One hundred thirty-two participants attended, representing 63 of the 65 projects. A survey, which included demographics and questions pertaining to the Ending the HIV Epidemic, was sent to potential attendees prior to the summit, to which 129 individuals—including all 65 project directors, 13 co-investigators, and 51 implementation partners (62% Female)—responded. Those who indicated an investigator role ( n = 78) received additional questions about prior implementation research training (e.g., formal coursework, workshop, self-taught) and related experiences (e.g., involvement in a funded implementation project, program implementation, program evaluation, quality improvement) and the stage of their project (i.e., exploration, preparation, implementation, sustainment [ 50 ]).

Approximately 6 weeks after the summit, 89 attendees (69%) completed a post-training survey comprising more than 40 questions about their overall experience. Though the invitation to complete the survey made no mention of the IRLM, it included 10 items related to the IRLM and one more generally about the logic of implementation research, each rated on a 4-point scale (1 = not at all , 2 = a little , 3 = moderately , 4 = very much ; see Table 1 ). Forty-two investigators (65% of projects) and 24 implementation partners indicated attending the training and began and completed the survey (68.2% female). Of the 66 respondents who attended the training, 100% completed all 11 IRLM items, suggesting little potential response bias.

Table 1 provides the means, standard deviations, and percent of respondents endorsing either “moderately” or “very” response options. Results were promising for the utility of the IRLM on the majority of the dimensions assessed. More than 50% of respondents indicated that the IRLM was “moderately” or “very” helpful on all questions. Overall, 77.6% ( M = 3.18, SD = .827) of respondents indicated that their knowledge on the logic of implementation research had increased either moderately or very much after the 2-day training. At the time of the survey, when respondents were about 2.5 months into their 1-year planning projects, 44.6% indicated that they had already been able to complete a full draft of the IRLM.

Additional analyses using a one-way analysis of variance indicated no statistically significant differences in responses to the IRLM questions between investigators and implementation partners. However, three items approached significance: planning the project ( F = 2.460, p = .055), clearly reporting and specifying how the project is to be conducted ( F = 2.327, p = .066), and knowledge on the logic of implementation research ( F = 2.107, p = .091). In each case, scores were higher for the investigators compared to the implementation partners, suggesting that perhaps the knowledge gap in implementation research lay more in the academic realm than among community partners, who may not have a focus on research but whose day-to-day roles include the implementation of EBPs in the real world. Lastly, analyses using ordinal logistic regression did not yield any significant relationship between responses to the IRLM survey items and prior training ( n = 42 investigators who attended the training and completed the post-training survey), prior related research experience ( n = 42), and project stage of implementation ( n = 66). This suggests that the IRLM is a useful tool for both investigators and implementers with varying levels of prior exposure to implementation research concepts and across all stages of implementation research. As a result of this training, the IRLM is now a required element in the FY2020 Ending the HIV Epidemic Centers for AIDS Research/AIDS Research Centers Supplement Announcement released March 2020 [ 15 ].

Resources for using the IRLM

As the use of the IRLM for different study designs and purposes continues to expand and evolve, we envision supporting researchers and other program implementers in applying the IRLM to their own contexts. Our team at Northwestern University hosts web resources on the IRLM that includes completed examples and tools to assist users in completing their model, including templates in various formats (Figs. 1 and 2 , Additional Files A 1 , A 2 , A 3 and A 4 and others) a Quick Reference Guide (Additional File A 8 ) and a series of worksheets that provide guidance on populating the IRLM (Additional File A 9 ). These will be available at https://cepim.northwestern.edu/implementationresearchlogicmodel/ .

The IRLM provides a compact visual depiction of an implementation project and is a useful tool for academic–practice collaboration and partnership development. Used in conjunction with supporting text, tables, and figures to detail each of the primary elements, the IRLM has the potential to improve a number of aspects of implementation research as identified in the results of the post-training survey. The usability of the IRLM is high for seasoned and novice implementation researchers alike, as evidenced by our survey results and preliminary work. Its use in the planning, executing, reporting, and synthesizing of implementation research could increase the rigor and transparency of complex studies that ultimately could improve reproducibility—a challenge in the field—by offering a common structure to increase consistency and a method for more clearly specifying links and pathways to test theories.

Implementation occurs across the gamut of contexts and settings. The IRLM can be used when large organizational change is being considered, such as a new strategic plan with multifaceted strategies and outcomes. Within a narrower scope of a single EBI in a specific setting, the larger organizational context still ought to be included as inner setting determinants (i.e., the impact of the organizational initiative on the specific EBI implementation project) and as implementation strategies (i.e., the specific actions being done to make the organizational change a reality that could be leveraged to implement the EBI or could affect the success of implementation). The IRLM has been used by our team to plan for large systemic changes and to initiate capacity building strategies to address readiness to change (structures, processes, individuals) through strategic planning and leadership engagement at multiple levels in the organization. This aspect of the IRLM continues to evolve.

Among the drawbacks of the IRLM is that it might be viewed as a somewhat simplified format. This represents the challenges of balancing depth and detail with parsimony, ease of comprehension, and ease of use. The structure of the IRLM may inhibit creative thinking if applied too rigidly, which is among the reasons we provide numerous examples of different ways to tailor the model to the specific needs of different project designs and parameters. Relatedly, we encourage users to iterate on the design of the IRLM to increase its utility.

The promise of implementation science lies in the ability to conduct rigorous and reproducible research, to clearly understand the findings, and to synthesize findings from which generalizable conclusions can be drawn and actionable recommendations for practice change emerge. As scientists and implementers have worked to better define the core methods of the field, the need for theory-driven, testable integration of the foundational elements involved in impactful implementation research has become more apparent. The IRLM is a tool that can aid the field in addressing this need and moving toward the ultimate promise of implementation research to improve the provision and quality of healthcare services for all people.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

Evidence-based intervention

Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change

Implementation Research Logic Model

Nosek BA, Alter G, Banks GC, Borsboom D, Bowman SD, Breckler SJ, Buck S, Chambers CD, Chin G, Christensen G, et al. Promoting an open research culture. Science. 2015;348:1422–5.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Slaughter SE, Hill JN, Snelgrove-Clarke E. What is the extent and quality of documentation and reporting of fidelity to implementation strategies: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2015;10:1–12.

Article Google Scholar

Brown CH, Curran G, Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Wells KB, Jones L, Collins LM, Duan N, Mittman BS, Wallace A, et al: An overview of research and evaluation designs for dissemination and implementation. Annual Review of Public Health 2017, 38:null.

Hwang S, Birken SA, Melvin CL, Rohweder CL, Smith JD: Designs and methods for implementation research: advancing the mission of the CTSA program. Journal of Clinical and Translational Science 2020:Available online.

Smith JD. An Implementation Research Logic Model: a step toward improving scientific rigor, transparency, reproducibility, and specification. Implement Sci. 2018;14:S39.

Google Scholar

Tabak RG, Khoong EC, Chambers DA, Brownson RC. Bridging research and practice: models for dissemination and implementation research. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:337–50.

Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;10:53.

Damschroder LJ. Clarity out of chaos: use of theory in implementation research. Psychiatry Res. 2019.

Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013;8.

Kessler RS, Purcell EP, Glasgow RE, Klesges LM, Benkeser RM, Peek CJ. What does it mean to “employ” the RE-AIM model? Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2013;36:44–66.

Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, Eldridge S, Grandes G, Griffiths CJ, Rycroft-Malone J, Meissner P, Murray E, Patel A, et al. Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI): explanation and elaboration document. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e013318.

Lewis CC, Klasnja P, Powell BJ, Lyon AR, Tuzzio L, Jones S, Walsh-Bailey C, Weiner B. From classification to causality: advancing understanding of mechanisms of change in implementation science. Front Public Health. 2018;6.

Glanz K, Bishop DB. The role of behavioral science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:399–418.

WK Kellogg Foundation: Logic model development guide. Battle Creek, Michigan: WK Kellogg Foundation; 2004.

CFAR/ARC Ending the HIV Epidemic Supplement Awards [ https://www.niaid.nih.gov/research/cfar-arc-ending-hiv-epidemic-supplement-awards ].

Funnell SC, Rogers PJ. Purposeful program theory: effective use of theories of change and logic models. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons; 2011.

Petersen D, Taylor EF, Peikes D. The logic model: the foundation to implement, study, and refine patient-centered medical home models (issue brief). Mathematica Policy Research: Mathematica Policy Research Reports; 2013.

Davidoff F, Dixon-Woods M, Leviton L, Michie S. Demystifying theory and its use in improvement. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2015;24:228–38.

Fernandez ME, ten Hoor GA, van Lieshout S, Rodriguez SA, Beidas RS, Parcel G, Ruiter RAC, Markham CM, Kok G. Implementation mapping: using intervention mapping to develop implementation strategies. Front Public Health. 2019;7.

Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, Mittman B. Implementation research in mental health services: an emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Admin Pol Ment Health. 2009;36.

Proctor EK, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, Griffey R, Hensley M. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health Ment Health Serv Res. 2011;38.

Rabin BA, Brownson RC: Terminology for dissemination and implementation research. In Dissemination and implementation research in health: translating science to practice. 2 edition. Edited by Brownson RC, Colditz G, Proctor EK. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2017: 19-45.

Smith JD, Rafferty MR, Heinemann AW, Meachum MK, Villamar JA, Lieber RL, Brown CH: Evaluation of the factor structure of implementation research measures adapted for a novel context and multiple professional roles. BMC Health Serv Res 2020.

Smith JD, Berkel C, Jordan N, Atkins DC, Narayanan SS, Gallo C, Grimm KJ, Dishion TJ, Mauricio AM, Rudo-Stern J, et al. An individually tailored family-centered intervention for pediatric obesity in primary care: study protocol of a randomized type II hybrid implementation-effectiveness trial (Raising Healthy Children study). Implement Sci. 2018;13:1–15.

Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP. Ending the HIV epidemic: a plan for the United States: Editorial. JAMA. 2019;321:844–5.

Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. 2012;7:50.

Brown CH, Curran G, Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Wells KB, Jones L, Collins LM, Duan N, Mittman BS, Wallace A, et al. An overview of research and evaluation designs for dissemination and implementation. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:1–22.

Krause J, Van Lieshout J, Klomp R, Huntink E, Aakhus E, Flottorp S, Jaeger C, Steinhaeuser J, Godycki-Cwirko M, Kowalczyk A, et al. Identifying determinants of care for tailoring implementation in chronic diseases: an evaluation of different methods. Implement Sci. 2014;9:102.

Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Fernández ME, Abadie B, Damschroder LJ. Choosing implementation strategies to address contextual barriers: diversity in recommendations and future directions. Implement Sci. 2019;14:42.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4.

Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, O’Connor D, Patey A, Ivers N, Foy R, Duncan EM, Colquhoun H, Grimshaw JM, et al. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement Sci. 2017;12:77.

Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, Damschroder LJ, Smith JL, Matthieu MM, Proctor EK, Kirchner JE. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement Sci. 2015;10.

Powell BJ, Fernandez ME, Williams NJ, Aarons GA, Beidas RS, Lewis CC, McHugh SM, Weiner BJ. Enhancing the impact of implementation strategies in healthcare: a research agenda. Front Public Health. 2019;7.

PAR-19-274: Dissemination and implementation research in health (R01 Clinical Trial Optional) [ https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-19-274.html ].

Edmondson D, Falzon L, Sundquist KJ, Julian J, Meli L, Sumner JA, Kronish IM. A systematic review of the inclusion of mechanisms of action in NIH-funded intervention trials to improve medication adherence. Behav Res Ther. 2018;101:12–9.

Gaglio B, Shoup JA, Glasgow RE. The RE-AIM framework: a systematic review of use over time. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:e38–46.

Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B, Rabin B, Smith ML, Porter GC, Ory MG, Estabrooks PA. RE-AIM planning and evaluation framework: adapting to new science and practice with a 20-year review. Front Public Health. 2019;7.

Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1322–7.

Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Sperber N, Robinson CH, Fickel JJ, Oddone EZ. Implementation evaluation of the Telephone Lifestyle Coaching (TLC) program: organizational factors associated with successful implementation. Transl Behav Med. 2016;7:233–41.

Bunger AC, Powell BJ, Robertson HA, MacDowell H, Birken SA, Shea C. Tracking implementation strategies: a description of a practical approach and early findings. Health Research Policy and Systems. 2017;15:15.

Boyd MR, Powell BJ, Endicott D, Lewis CC. A method for tracking implementation strategies: an exemplar implementing measurement-based care in community behavioral health clinics. Behav Ther. 2018;49:525–37.