The Law Dictionary

Your Free Online Legal Dictionary • Featuring Black’s Law Dictionary, 2nd Ed.

HYPOTHESIS Definition & Legal Meaning

Definition & citations:.

A supposition, assumption, or theory; a theory set up by the prosecution,on a criminal trial, or by the defense, as an explanation of the facts in evidence,and a ground for inferring guilt or innocence, as the case may be, or asindicating a probable or possible motive for the crime.

This article contains general legal information but does not constitute professional legal advice for your particular situation. The Law Dictionary is not a law firm, and this page does not create an attorney-client or legal adviser relationship. If you have specific questions, please consult a qualified attorney licensed in your jurisdiction.

Browse Legal Articles

Business Formation

Business Law

Child Custody & Support

Criminal Law

Employment & Labor Law

Estate Planning

Immigration

Intellectual Property

Landlord-Tenant

Motor Vehicle Accidents

Personal Injury

Real Estate & Property Law

Traffic Violations

Browse by Area of Law

Powered by Black’s Law Dictionary, Free 2nd ed., and The Law Dictionary .

About The Law Dictionary

Terms and Conditions

Privacy Policy

- TheFreeDictionary

- Word / Article

- Starts with

- Free toolbar & extensions

- Word of the Day

- Free content

An assumption or theory.

During a criminal trial, a hypothesis is a theory set forth by either the prosecution or the defense for the purpose of explaining the facts in evidence. It also serves to set up a ground for an inference of guilt or innocence, or a showing of the most probable motive for a criminal offense.

- criminology

- Dred Scott v. Sandford

- fingerprint

- Indirect Evidence

- Kelsen, Hans

- Kelsinian jurisprudence

- natural law

- Second Treatise on Government

- Hunter, Elmo Bolton

- hunting and felony charges

- hunting with hounds

- Huntley Hearing

- Hurtado v. California

- Husband and Wife

- husband and wife on mortgage

- Husband died, wife accused of identity theft

- Husband in jail for possession

- Husband taken to jail for outstanding ticket

- Husband tested positive for drugs at work

- hybrid bill

- Hypothecate

- hypothecation

- Hypothetical Question

- Ictus orbis

- Id certum est quod certum reddi potest

- Id perfectum est quod ex omnibus suis partibus constat

- Id possumus quod de jure possumus

- Id quod nostrum est

- Idem agens et patiens esse non potest

- Idem est facere

- Idem est nihil dicere et insufficienter dicere

- Idem est non probari et non esse; non deficit jus

- Idem est scire aut scire debet aut potuisse

- Idem non esse et non apparet

- Idem semper antecedenti proximo refertur

- Idem sonans

- identification parade

- Hypothermia After Cardiac Arrest

- Hypothermia After Cardiac Arrest Registry

- hypothermia blanket

- hypothermia therapy

- hypothermia treatment

- Hypothermia, induced

- hypothermic

- hypothermic anesthesia

- hypothermic circulatory arrest

- Hypothermic machine perfusion

- hypothermicly

- Hypothèse Extraterrestre

- Hypothesis Driven Lexical Adaptation

- Hypothesis test

- Hypothesis testing

- hypothesis testing sampling

- hypothesis to test

- Hypothesis-Based Testing

- Hypothesis-Oriented Algorithm for Clinicians

- hypothesise

- hypothesised

- hypothesiser

- hypothesisers

- hypothesises

- Facebook Share

The Law Dictionary

TheLaw.com Law Dictionary & Black's Law Dictionary 2nd Ed.

A supposition, assumption, or theory; a theory set up by the prosecution, on a criminal trial, or by the defense, as an explanation of the facts in evidence, and a ground for Inferring guilt or Innocence, as the case may be, or as indicating a probable or possible motive for the crime.

No related posts found

- Legal Terms

- Editorial Guidelines

- © 1995 – 2016 TheLaw.com LLC

Hypothesis, Model, Theory, and Law

Dorling Kindersley / Getty Images

- Physics Laws, Concepts, and Principles

- Quantum Physics

- Important Physicists

- Thermodynamics

- Cosmology & Astrophysics

- Weather & Climate

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/AZJFaceShot-56a72b155f9b58b7d0e783fa.jpg)

- M.S., Mathematics Education, Indiana University

- B.A., Physics, Wabash College

In common usage, the words hypothesis, model, theory, and law have different interpretations and are at times used without precision, but in science they have very exact meanings.

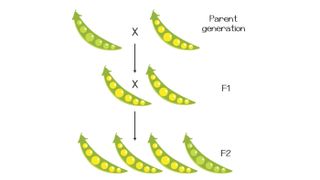

Perhaps the most difficult and intriguing step is the development of a specific, testable hypothesis. A useful hypothesis enables predictions by applying deductive reasoning, often in the form of mathematical analysis. It is a limited statement regarding the cause and effect in a specific situation, which can be tested by experimentation and observation or by statistical analysis of the probabilities from the data obtained. The outcome of the test hypothesis should be currently unknown, so that the results can provide useful data regarding the validity of the hypothesis.

Sometimes a hypothesis is developed that must wait for new knowledge or technology to be testable. The concept of atoms was proposed by the ancient Greeks , who had no means of testing it. Centuries later, when more knowledge became available, the hypothesis gained support and was eventually accepted by the scientific community, though it has had to be amended many times over the year. Atoms are not indivisible, as the Greeks supposed.

A model is used for situations when it is known that the hypothesis has a limitation on its validity. The Bohr model of the atom , for example, depicts electrons circling the atomic nucleus in a fashion similar to planets in the solar system. This model is useful in determining the energies of the quantum states of the electron in the simple hydrogen atom, but it is by no means represents the true nature of the atom. Scientists (and science students) often use such idealized models to get an initial grasp on analyzing complex situations.

Theory and Law

A scientific theory or law represents a hypothesis (or group of related hypotheses) which has been confirmed through repeated testing, almost always conducted over a span of many years. Generally, a theory is an explanation for a set of related phenomena, like the theory of evolution or the big bang theory .

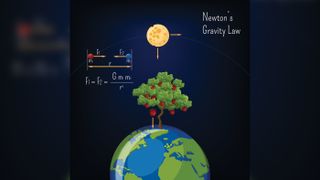

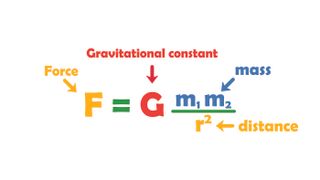

The word "law" is often invoked in reference to a specific mathematical equation that relates the different elements within a theory. Pascal's Law refers an equation that describes differences in pressure based on height. In the overall theory of universal gravitation developed by Sir Isaac Newton , the key equation that describes the gravitational attraction between two objects is called the law of gravity .

These days, physicists rarely apply the word "law" to their ideas. In part, this is because so many of the previous "laws of nature" were found to be not so much laws as guidelines, that work well within certain parameters but not within others.

Scientific Paradigms

Once a scientific theory is established, it is very hard to get the scientific community to discard it. In physics, the concept of ether as a medium for light wave transmission ran into serious opposition in the late 1800s, but it was not disregarded until the early 1900s, when Albert Einstein proposed alternate explanations for the wave nature of light that did not rely upon a medium for transmission.

The science philosopher Thomas Kuhn developed the term scientific paradigm to explain the working set of theories under which science operates. He did extensive work on the scientific revolutions that take place when one paradigm is overturned in favor of a new set of theories. His work suggests that the very nature of science changes when these paradigms are significantly different. The nature of physics prior to relativity and quantum mechanics is fundamentally different from that after their discovery, just as biology prior to Darwin’s Theory of Evolution is fundamentally different from the biology that followed it. The very nature of the inquiry changes.

One consequence of the scientific method is to try to maintain consistency in the inquiry when these revolutions occur and to avoid attempts to overthrow existing paradigms on ideological grounds.

Occam’s Razor

One principle of note in regards to the scientific method is Occam’s Razor (alternately spelled Ockham's Razor), which is named after the 14th century English logician and Franciscan friar William of Ockham. Occam did not create the concept—the work of Thomas Aquinas and even Aristotle referred to some form of it. The name was first attributed to him (to our knowledge) in the 1800s, indicating that he must have espoused the philosophy enough that his name became associated with it.

The Razor is often stated in Latin as:

entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem

or, translated to English:

entities should not be multiplied beyond necessity

Occam's Razor indicates that the most simple explanation that fits the available data is the one which is preferable. Assuming that two hypotheses presented have equal predictive power, the one which makes the fewest assumptions and hypothetical entities takes precedence. This appeal to simplicity has been adopted by most of science, and is invoked in this popular quote by Albert Einstein:

Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler.

It is significant to note that Occam's Razor does not prove that the simpler hypothesis is, indeed, the true explanation of how nature behaves. Scientific principles should be as simple as possible, but that's no proof that nature itself is simple.

However, it is generally the case that when a more complex system is at work there is some element of the evidence which doesn't fit the simpler hypothesis, so Occam's Razor is rarely wrong as it deals only with hypotheses of purely equal predictive power. The predictive power is more important than the simplicity.

Edited by Anne Marie Helmenstine, Ph.D.

- Scientific Hypothesis, Model, Theory, and Law

- Einstein's Theory of Relativity

- What Is a Paradigm Shift?

- Wave Particle Duality and How It Works

- Scientific Method

- Oversimplification and Exaggeration Fallacies

- Kinetic Molecular Theory of Gases

- Understanding Cosmology and Its Impact

- The History of Gravity

- The Copenhagen Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics

- Tips on Winning the Debate on Evolution

- Geological Thinking: Method of Multiple Working Hypotheses

- The Life and Work of Albert Einstein

- Newton's Law of Gravity

- De Broglie Hypothesis

- What Is a Scientific or Natural Law?

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

The Legal Concept of Evidence

The legal concept of evidence is neither static nor universal. Medieval understandings of evidence in the age of trial by ordeal would be quite alien to modern sensibilities (Ho 2003–2004) and there is no approach to evidence and proof that is shared by all legal systems of the world today. Even within Western legal traditions, there are significant differences between Anglo-American law and Continental European law (see Damaška 1973, 1975, 1992, 1994, 1997). This entry focuses on the modern concept of evidence that operates in the legal tradition to which Anglo-American law belongs. [ 1 ] It concentrates on evidence in relation to the proof of factual claims in law. [ 2 ]

It may seem obvious that there must be a legal concept of evidence that is distinguishable from the ordinary concept of evidence. After all, there are in law many special rules on what can or cannot be introduced as evidence in court, on how evidence is to be presented and the uses to which it may be put, on the strength or sufficiency of evidence needed to establish proof and so forth. But the law remains silent on some crucial matters. In resolving the factual disputes before the court, the jury or, at a bench trial, the judge has to rely on extra-legal principles. There have been academic attempts at systematic analysis of the operation of these principles in legal fact-finding (Wigmore 1937; Anderson, Schum, and Twining 2009). These principles, so it is claimed, are of a general nature. On the basis that the logic in “drawing inferences from evidence to test hypotheses and justify conclusions” is governed by the same principles across different disciplines (Twining and Hampsher-Monk 2003: 4), ambitious projects have been undertaken to develop a cross-disciplinary framework for the analysis of evidence (Schum 1994) and to construct an interdisciplinary “integrated science of evidence” (Dawid, Twining, and Vasilaki 2011; cf. Tillers 2008).

While evidential reasoning in law and in other contexts may share certain characteristics, there nevertheless remain aspects of the approach to evidence and proof that are distinctive to law (Rescher and Joynt 1959). Section 1 (“conceptions of evidence”) identifies different meanings of evidence in legal discourse. When lawyers talk about evidence, what is it that they are referring to? What is it that they have in mind? Section 2 (“conditions for receiving evidence”) approaches the concept of legal evidence from the angle of what counts as evidence in law. What are the conditions that the law imposes and must be met for something to be received by the court as evidence? Section 3 (“strength of evidence”) shifts the attention to the stage where the evidence has already been received by the court. Here the focus is on how the court weighs the evidence in reaching the verdict. In this connection, three properties of evidence will be discussed: probative value, sufficiency, and degree of completeness.

1. Conceptions of Evidence: What does Evidence Refer to in Law?

2.1.1 legal significance of relevance, 2.1.2 conceptions of logical relevance, 2.1.3 logical relevance versus legal relevance, 2.2 materiality and facts-in-issue, 2.3.1 admissibility and relevance, 2.3.2 admissibility or exclusionary rules, 3.1 probative value of specific items of evidence, 3.2.1 mathematical probability and the standards of proof, 3.2.2 objections to using mathematical probability to interpret standards of proof, 3.3 the weight of evidence as the degree of evidential completeness, other internet resources, related entries.

Stephen (1872: 3–4, 6–7) long ago noted that legal usage of the term “evidence” is ambiguous. It sometimes refers to that which is adduced by a party at the trial as a means of establishing factual claims. (“Adducing evidence” is the legal term for presenting or producing evidence in court for the purpose of establishing proof.) This meaning of evidence is reflected in the definitional section of the Indian Evidence Act (Stephen 1872: 149). [ 3 ] When lawyers use the term “evidence” in this way, they have in mind what epistemologists would think of as “objects of sensory evidence” (Haack 2004: 48). Evidence, in this sense, is divided conventionally into three main categories: [ 4 ] oral evidence (the testimony given in court by witnesses), documentary evidence (documents produced for inspection by the court), and “real evidence”; the first two are self-explanatory and the third captures things other than documents such as a knife allegedly used in committing a crime.

The term “evidence” can, secondly, refer to a proposition of fact that is established by evidence in the first sense. [ 5 ] This is sometimes called an “evidential fact”. That the accused was at or about the scene of the crime at the relevant time is evidence in the second sense of his possible involvement in the crime. But the accused’s presence must be proved by producing evidence in the first sense. For instance, the prosecution may call a witness to appear before the court and get him to testify that he saw the accused in the vicinity of the crime at the relevant time. Success in proving the presence of the accused (the evidential fact) will depend on the fact-finder’s assessment of the veracity of the witness and the reliability of his testimony. (The fact-finder is the person or body responsible for ascertaining where the truth lies on disputed questions of fact and in whom the power to decide on the verdict vests. The fact-finder is also called “trier of fact” or “judge of fact”. Fact-finding is the task of the jury or, for certain types of cases and in countries without a jury system, the judge.) Sometimes the evidential fact is directly accessible to the fact-finder. If the alleged knife used in committing the crime in question (a form of “real evidence”) is produced in court, the fact-finder can see for himself the shape of the knife; he does not need to learn of it through the testimony of an intermediary.

A third conception of evidence is an elaboration or extension of the second. On this conception, evidence is relational. A factual proposition (in Latin, factum probans ) is evidence in the third sense only if it can serve as a premise for drawing an inference (directly or indirectly) to a matter that is material to the case ( factum probandum ) (see section 2.2 below for the concept of materiality). The fact that the accused’s fingerprints were found in a room where something was stolen is evidence in the present sense because one can infer from this that he was in the room, and his presence in the room is evidence of his possible involvement in the theft. On the other hand, the fact that the accused’s favorite color is blue would, in the absence of highly unusual circumstances, be rejected as evidence of his guilt: ordinarily, what a person’s favorite color happens to be cannot serve as a premise for any reasonable inference towards his commission of a crime and, as such, it is irrelevant (see discussion of relevance in section 2.1 below). In the third sense of “evidence”, which conceives of evidence as a premise for a material inference, “irrelevant evidence” is an oxymoron: it is simply not evidence. Hence, this statement of Bentham (1825: 230): [ 6 ]

To say that testimony is not pertinent, is to say that it is foreign to the case, has no connection with it, and does not serve to prove the fact in question; in a word, it is to say, that it is not evidence.

There can be evidence in the first sense without evidence in the second or third sense. To pursue our illustration, suppose it emerges during cross-examination of the expert that his testimony of having found a finger-print match was a lie. Lawyers would describe this situation as one where the “evidence” (the testimony of the expert) fails to prove the fact that it was originally produced to prove and not that no “evidence” was adduced on the matter. Here “evidence” is used in the first sense—evidence as testimony—and the testimony remains in the court’s record whether it is believed or not. But lawyers would also say that, in the circumstances, there is no “evidence” that the accused was in the room, assuming that there was nothing apart from the discredited expert testimony of a fingerprint match to establish his presence there. Here, the expert’s testimony is shown to be false and fails to establish that the accused’s fingerprints were found in the room, and there is no (other) factual basis for believing that he was in the room. The factual premise from which an inference is sought to be drawn towards the accused’s guilt is not established.

Fourthly, the conditions for something to be received (or, in technical term “admitted”) as evidence at the trial are sometimes included in the legal concept of evidence. (These conditions are discussed in section 2 below.) On this conception, legal evidence is that which counts as evidence in law. Something may ordinarily be treated as evidence and yet be rejected by the court. Hearsay is often cited as an example. It is pointed out that reliance on hearsay is a commonplace in ordinary life. We frequently rely on hearsay in forming our factual beliefs. In contrast, “hearsay is not evidence” in legal proceedings (Stephen 1872: 4–5). As a general rule, the court will not rely on hearsay as a premise for an inference towards the truth of what is asserted. It will not allow a witness to testify in court that another person X (who is not brought before the court) said that p on a certain occasion (an out-of-court statement) for the purpose of proving that p .

In summary, at least four possible conceptions of legal evidence are in currency: as an object of sensory evidence, as a proposition of fact, as an inferential premise and as that which counts as evidence in law. The sense in which the term “evidence” is being used is seldom made explicit in legal discourse although the intended meaning will often be clear from the context.

2. Conditions for Receiving Evidence: What Counts as Evidence in Law?

This section picks up on the fourth conception of evidence. To recall, something will be accepted by the court as evidence—it is, to use Montrose’s term, receivable as evidence in legal proceedings—only if three basic conditions are satisfied: relevance , materiality, and admissibility (Montrose 1954). These three conditions of receivability are discussed in turn below.

2.1 Relevance

The concept of relevance plays a pivotal role in legal fact-finding. Thayer (1898: 266, 530) articulates its significance in terms of two foundational principles of the law of evidence: first, without exception, nothing which is not relevant may be received as evidence by the court and secondly, subject to many exceptions and qualifications, whatever is relevant is receivable as evidence by the court. Thayer’s view has been influential and finds expression in sources of law, for example, in Rule 402 of the Federal Rules of Evidence in the United States. [ 7 ] Thayer claims, and it is now widely accepted, that relevance is a “logical” and not a legal concept; in section 2.1.3 , we will examine this claim and the dissent expressed by Wigmore. Leaving aside the dissenting view for the moment, we will turn first to consider possible conceptions of relevance in the conventional sense of logical relevance.

Evidence may be adduced in legal proceedings to prove a fact only if the fact is relevant. Relevance is a relational concept. No fact is relevant in itself; it is relevant only in relation to another fact. The term “probable” is often used to describe this relation. We see two instances of this in the following well-known definitions. According to Stephen (1886: 2, emphasis added):

The word “relevant” means that any two facts to which it is applied are so related to each other that according to the common course of events one either taken by itself or in connection with other facts proves or renders probable the past, present, or future existence or non-existence of the other.

The second definition is contained in the United States’ Federal Rule of Evidence 401 which (in its restyled version) states that evidence is relevant if “it has a tendency to make a fact more or less probable than it would be without the evidence” (emphasis added). The word “probable” in these and other standard definitions is sometimes construed as carrying the mathematical meaning of probability. [ 8 ] In a leading article, Lempert gave this example to show how relevance turns on the likelihood ratio. The prosecution produces evidence that the perpetrator’s blood found at the scene of the crime is type A. The accused has the same blood type. Suppose fifty percent of the suspect population has type A blood. If the accused is in fact guilty, the probability that the blood found at the scene will be type A is 1.0. But if he is in fact innocent, the probability of finding type A blood at the scene is 0.5—that is, it matches the background probability of type A blood from the suspect population. The likelihood ratio is the ratio of the first probability to the second—1.0:0.5 or, more simply, 2:1. Evidence is considered relevant so long as the likelihood ratio is other than 1:1 (Lempert 1977). If the ratio is 1:1, that means that the probability of the evidence is the same whether the accused is guilty or innocent.

The conventional view is that relevance in law is a binary concept: evidence is either relevant or it is not. So long as the likelihood ratio is other than 1:1, the evidence is considered relevant. [ 9 ] However, the greater the likelihood ratio deviates from 1:1, the higher the so-called probative value of the evidence (that is, on one interpretation of probative value). We will take a closer look at probative value in section 3.1 below.

While the likelihood ratio may be useful as a heuristic device in analysing evidential reasoning, it is controversial as to whether it captures correctly the concept of relevance. In the first place, it is unclear that the term “probable” in the standard definitions of relevance was ever intended as a reference to mathematical probability. Some have argued that relevance should be understood broadly such that any evidence would count as relevant so long as it provides some reason in support of the conclusion that a proposition of fact material to the case is true or false (Pardo 2013: 576–577).

The mathematical conception of relevance has been disputed. At a trial, it is very common for the opposing sides to present competing accounts of events that share certain features. To use Allen’s example, the fact that the accused drove to a particular town on a particular day and time is consistent with the prosecution’s case that he was driving there to commit a murder and also with the defence’s case that he was driving there to visit his mother. This fact, being a common feature of both sides’ explanations of the material events, is as consistent with the hypothesis of guilt as with the hypothesis of innocence. On the likelihood ratio conception of relevance, this fact should be irrelevant and hence evidence of it should not be allowed to be adduced. But in such cases, the court will let the evidence in (Park et al. 2010: 10). The mathematical theory of relevance cannot account for this. (For critical discussion of this claim, see section 4.2 of the entry on legal probabilism .) It is argued that an alternative theory of relevance better fits legal practice and is thus to be preferred. On an explanatory conception of relevance, evidence is relevant if it is explained by or provides a reason for believing the particular explanation of the material events offered by the side adducing the evidence, and it remains relevant even where, as in our example, the evidence also supports or forms part of the explanation offered by the opponent (Pardo and Allen 2008: 241–2; Pardo 2013: 600).

One possible response to the above challenge to the likelihood ratio theory of relevance is to deny that it was ever meant to be the exclusive test of relevance. Evidence is relevant if the likelihood ratio is other than 1:1. But evidence may also be relevant on other grounds, such as when it provides for a richer narrative or helps the court in understanding other evidence. It is for these reasons that witnesses are routinely allowed to give their names and parties may present diagrams, charts and floor plans (so-called “demonstrative evidence”) at the trial (McCormick 2013: 995). The admission of evidence in the scenario painted by Allen above has been explained along a similar line (Park et al. 2010: 16).

The concept of relevance examined in the preceding section is commonly known as “logical relevance”. This is somewhat of a misnomer: “Relevance is not a matter of logic, but depends on matters of fact” (Haack 2004: 46). In our earlier example, the relevance of the fact that the accused has type A blood depends obviously on the state of the world. On the understanding that relevance is a probabilistic relation, it is tempting to think that in describing relevance as “logical”, one is subscribing to a logical theory of probability (cf. Franklin 2011). However, the term “logical relevance” was not originally coined with this connotation in mind. In the forensic context, “logic” is used loosely and refers to the stock of background beliefs or generalisations and the type of reasoning that judges and lawyers are fond of labelling as “commonsense” (MacCrimmon 2001–2002; Twining 2006: 334–335).

A key purpose of using the adjective “logical” is to flag the non-legal character of relevance. As Thayer (1898: 269) famously claimed, relevance “is an affair of logic and not of law.” This is not to say that relevance has no legal dimension. The law distinguishes between questions of law and questions of fact. An issue of relevance poses a question of law that is for the judge to decide and not the jury, and so far as relevance is defined in legal sources (for example, in Federal Rule of Evidence 401 mentioned above), the judge must pay heed to the legal definition. But legal definitions of relevance are invariably very broad. Relevance is said to be a logical, and non-legal, concept in the sense that in answering a question of relevance and in applying the definition of relevance, the judge has necessarily to rely on extra-legal resources and is not bound by legal precedents. Returning to Federal Rule of Evidence 401, it states generally that evidence is relevant if “it has a tendency to make a fact more or less probable than it would be without the evidence”. In deciding whether the evidence sought to be adduced does have this tendency, the judge has to look outside the law. Thayer was most insistent on this. As he put it, “[t]he law furnishes no test of relevancy. For this, it tacitly refers to logic and general experience” (Thayer 1898: 265). That the accused’s favorite color is blue is, barring extraordinary circumstances, irrelevant to the question of his intention to commit theft. It is not the law that tells us so but “logic and general experience”. On Thayer’s view, the law does not control or regulate the assessment of relevance; it assumes that judges are already in possession of the (commonsense) resources to undertake this assessment.

Wigmore adopts a different position. He argues, against Thayer, that relevance is a legal concept. There are two strands to his contention. The first is that for evidence to be relevant in law, “a generally higher degree of probative value” is required “than would be asked in ordinary reasoning”:

legal relevance denotes…something more than a minimum of probative value. Each single piece of evidence must have a plus value. (cf. Pattenden 1996–7: 373)

As Wigmore sees it, the requirement of “plus value” guards against the jury “being satisfied by matters of slight value, capable to being exaggerated by prejudice and hasty reasoning” (Wigmore 1983b: 969, cf. 1030–1031). Opponents of Wigmore acknowledge that there may be sound policy reasons for excluding evidence of low probative value. Receiving the evidence at the trial might raise a multiplicity of issues, incur too much time and expense, confuse the jurors or produce undue prejudice in their mind. When the judge excludes evidence for any of these reasons, and the judge has the discretion to do so in many countries, the evidence is excluded despite it being relevant (e.g., United States’ Federal Rule of Evidence 403). Relevance is a relation between facts and the aforesaid reasons for exclusion are extrinsic to that relation; they are grounded in considerations such as limitation of judicial resources and jury psychology. The notion of “plus value” confuses relevance with extraneous considerations (James 1941; Trautman 1952).

There is a second strand to Wigmore’s contention that relevance is a legal concept. Relevance is legal in the sense that the judge is bound by previously decided cases (“judicial precedents”) when he has to make a ruling on the relevance of a proposed item of evidence.

So long as Courts continue to declare…what their notions of logic are, just so long will there be rules of law which must be observed. (Wigmore 1983a: 691)

Wigmore cites in support the judgment of Cushing C.J. in State v LaPage where it was remarked:

[T]here are many instances in which the evidence of particular facts as bearing on particular issues has been so often the subject of discussion in courts of law, and so often ruled upon, that the united logic of a great many judges and lawyers may be said to furnish…the best evidence of what may be properly called common -sense, and thus to acquire the authority of law. (1876 57 N.H. 245 at 288 [Supreme Court, New Hampshire])

Wigmore’s position on relevance is strangely at odds with his strong stand against the judge being bound by judicial precedents in assessing the weight or credibility of evidence (Wigmore 1913). More importantly, the second strand of his argument also does not sit well with the first strand. If, as Wigmore contends, evidence must have a plus value to make it legally relevant, the court has to consider the probative value of the evidence and to weigh it against the amount of time and expense likely to be incurred in receiving the evidence, the availability of other evidence, the risk of the evidence misleading or confusing the trier of fact and so forth. Given that the assessment of plus value and, hence, legal relevance is so heavily contextual, it is difficult to see how a judicial precedent can be of much value in another case in determining a point of legal relevance (James 1941: 702).

We have just considered the first condition of receivability, namely, relevance. That fact A is relevant to fact B is not sufficient to make evidence of fact A receivable in court. In addition, B must be a “material” fact. The materiality of facts in a particular case is determined by the law applicable to that case. In a criminal prosecution, it depends on the law which defines the offence with which the accused is charged and at a civil trial, the law which sets out the elements of the legal claim that is being brought against the defendant (Wigmore 1983a, 15–19; Montrose 1954: 536–537).

Imagine that the accused is prosecuted for the crime of rape and the alleged victim’s behaviour (fact A ) increases the probability that she had consented to have sexual intercourse with the accused (fact B ). On the probabilistic theory of relevance that we have considered, A is relevant to B . Now suppose that the alleged victim is a minor. Under criminal law, it does not matter whether she had consented to the sexual intercourse. If B is of no legal consequence, the court will not allow evidence of A to be adduced for the purpose of proving B : the most obvious reason is that it is a waste of time to receive the evidence.

Not all material facts are necessarily in dispute. Suppose the plaintiff sues the defendant for breach of contract. Under the law of contract, to succeed in this action, the plaintiff must prove the following three elements: that there was a contract between the parties, that the defendant was in breach of the contract, and that the plaintiff had suffered loss as a result of that breach. The defendant may concede that there was a contract and that he was in breach of it but deny that the plaintiff had suffered any loss as a result of that breach. In such a situation, only the last of the material facts is disputed. Following Stephen’s terminology, a disputed material fact is called a “fact in issue” (Stephen 1872: 9).

The law does not allow evidence to be adduced to prove facts that are immaterial. Whether evidence may be adduced to prove a material fact may depend on whether the material fact is disputed; for instance, the requirement that it must be disputed exists under Rule 210 of the Evidence Code of California but not Rule 401 of the Federal Rules of Evidence in the United States. “Relevance” is often used in the broader sense that encompasses the concepts under discussion. Evidence is sometimes described as “irrelevant” not for the reason that no logical inference can be drawn to the proposition that is sought to be proved (in our example, A is strictly speaking relevant to B ) but because that proposition is not material or not disputed (in our example, B is not material). [ 10 ] This broader usage of the term “relevance”, though otherwise quite harmless, does not promote conceptual clarity because it runs together different concepts (see James 1941: 690–691; Trautman 1952: 386; Montrose 1954: 537).

2.3 Admissibility

A further condition must be satisfied for evidence to be received in legal proceedings. There are legal rules that prohibit evidence from being presented at a trial even though it is relevant to a factual proposition that is material and in issue. These rules render the evidence to which they apply “inadmissible” and require the judge to “exclude” it. Two prominent examples of such rules of admissibility or rules of exclusion are the rule against hearsay evidence and the rule against character evidence. This section considers the relation between the concept of relevance and the concept of admissibility. The next section ( section 2.3.2 ) discusses general arguments for and against exclusionary or admissibility rules.

Here, again, the terminology is imprecise. Admissibility and receivability are not clearly distinguished. It is common for irrelevant evidence, or evidence of an immaterial fact to be described as “inadmissible”. What this means is that the court will refuse to receive evidence if it is irrelevant or immaterial. But, importantly, the court also excludes evidence for reasons other than irrelevance and immateriality. For Montrose, there is merit in restricting the concept of “inadmissibility” to the exclusion of evidence based on those other reasons (Montrose 1954: 541–543). If evidence is rejected on the ground of irrelevance, it is, as Thayer (1898: 515) puts it, “the rule of reason that rejects it”; if evidence is rejected under an admissibility or exclusionary rule, the rejection is by force of law. The concepts of admissibility and materiality should also be kept apart. This is because admissibility or exclusionary rules serve purposes and rationales that are distinct from the law defining the crime or civil claim that is before the court and it is this law that determines the materiality of facts in the dispute.

Thayer (1898: 266, 530) was influential in his view that the law of evidence has no say on logical relevance and that its main business is in dealing with admissibility. If the evidence is logically irrelevant, it must for that reason be excluded. If the evidence is logically relevant, it will be received by the court unless the law—in the form of an exclusionary or admissibility rule—requires its exclusion. In this scheme, the concept of relevance and the concept of admissibility are distinct: indeed, admissibility rules presuppose the relevance of the evidence to which they apply.

Stephen appears to hold a different view, one in which the concept of admissibility is apparently absorbed by the concept of relevance. Take, for example, Stephen’s analysis of the rule that in general no evidence may be adduced to prove “statements as to facts made by persons not called as witnesses”, in short, hearsay (Stephen 1872: 122). As a general rule, no evidence may be given of hearsay because the law prohibits it. The question then arises as to the rationale for this prohibition. Stephen’s answer to this question is often taken to be that hearsay is not “relevant” and he is criticised for failing to see the difference between relevance and admissibility (Whitworth 1881: 3; Thayer 1898: 266–268; Pollock 1876, 1899; Wigmore 1983a: §12). His critics point out that hearsay has or can have probative value and evidence of hearsay is excluded despite or regardless of its relevance. On the generalisation that there is no smoke without fire, the fact that a person claimed that p in a statement made out-of-court does or can have a bearing on the probability that p , and p may be (logically relevant to) a material fact in the dispute.

Interestingly, Stephen seemed to have conceded as much. He acknowledged that a policeman or a lawyer engaged in preparing a case would be negligent if he were to shut his ears to hearsay. Hearsay is one of those facts that are “apparently relevant but not really so” (Stephen 1872: 122; see also Stephen 1886: xi). In claiming that hearsay is irrelevant, Stephen appears to be merely stating the effect of the law: the law requires that hearsay be treated as irrelevant. He offered a variety of justifications for excluding hearsay evidence: its admissibility would “present a great temptation to indolent judges to be satisfied with second-hand reports” and “open a wide door to fraud”, with the result that “[e]veryone would be at the mercy of people who might tell a lie, and whose evidence could neither be tested nor contradicted” (Stephen 1872: 124–125). For his detractors, these are reasons of policy and fairness and it disserves clarity to sneak such considerations into the concept of relevance.

Although there is force to the criticism that Stephen had unhelpfully conflated admissibility and relevance (understood as logical relevance), something can perhaps be said in his defence. Exclusionary rules or rules of admissibility—at any rate, many of them—are more accurately seen as excluding forms of reasoning rather than prohibiting proof of certain types of facts (McNamara 1986). This is certainly true of the hearsay rule. On one authoritative definition of the rule (decision of the Privy Council in Subramaniam v PP , (1956) 1 Weekly Law Reports 965), what it prohibits is the use of a hearsay statement to prove the truth of the facts asserted therein. [ 11 ] The objection is to the drawing of the inference that p from X ’s out-of-court statement that p where X is not available to be examined in court. But the court will allow the evidence of X ’s hearsay statement to be admitted—it will allow proof of the statement— where the purpose of adducing the evidence is to persuade the court that X did make the statement and this fact is relevant for some other purpose. For instance, it may be relevant as to the state of mind of the person hearing the statement, and his state of mind may be material to his defence of having acted under duress. Hence, two writers have commented that “there is no such thing as hearsay evidence , only hearsay uses ” (Roberts and Zuckerman 2010: 385).

Other admissibility rules are also more accurately seen as targeted at forms of reasoning and not types of facts. In the United States, Federal Rule of Evidence 404(a)(1) bars the use of evidence of a person’s character “to prove that on a particular occasion the person acted in accordance with the character” and Federal Rule of Evidence 404(b)(1) provides that evidence of a crime or wrong

is not admissible to prove a person’s character in order to show that on a particular occasion the person acted in accordance with the character.

It is doubtful that evidence of a person’s character and past behaviour can have no probabilistic bearing on his behaviour on a particular occasion; on a probabilistic conception of relevance, it is difficult to see why the evidence is not relevant. Even so, there may be policy, moral or other reasons for the law to prohibit certain uses of character evidence. In declaring a fact as irrelevant for a particular purpose, we are not necessarily saying or implying anything about probability. We may be expressing a normative judgment. For policy, moral or other reasons, the law takes the position that hearsay or the accused’s character or previous misconduct must not be used as the premise for a particular line of reasoning. The line of reasoning might be morally objectionable (“give a dog a bad name and hang him for it”) or it might be unfair to permit the drawing of the inference when the opponent was not given a fair opportunity to challenge it (as in the hearsay situation) (Ho 2008: chs. 5, 6). If we take a normative conception of relevance instead of a logical or probabilistic one, it is not an abuse of language to describe inadmissible evidence as irrelevant if what is meant is that the evidence ought not to be taken into account in a certain way.

On one historical account, admissibility or exclusionary rules are the product of the jury system where citizens untrained in assessing evidence sit as judges of fact. These rules came about because it was thought necessary to keep away from inexperienced jurors certain types of evidence that may mislead or be mishandled by them—for instance, evidence to which they are likely to give too much weight or that carries the risk of creating unfair prejudice in their minds (Thayer 1898; Wigmore 1935: 4–5). Epistemic paternalism is supposedly at play (Leiter 1997: 814–5; Allen and Leiter 2001: 1502). Subscription to this theory has generated pressure for the abolition of exclusionary rules with the decline of the jury system and the replacement of lay persons with professional judges as triers of fact. There is doubt as to the historical accuracy of this account; at any rate, it does not appear capable of explaining the growth of all exclusionary rules (Morgan 1936–37; Nance 1988: 278–294).

Even if the theory is right, it does not necessarily follow that exclusionary rules should be abolished once the jury system is removed. Judges may be as susceptible to the same cognitive and other failings as the jury and there may be the additional risk that judges may over-estimate their own cognitive and intellectual abilities in their professional domain. Hence, there remains a need for the constraints of legal rules (Schauer 2006: 185–193). But the efficacy of these rules in a non-jury system is questionable. The procedural reality is that judges will have to be exposed to the evidence in order to decide on its admissibility. Since a judge cannot realistically be expected to erase the evidence from his mind once he has decided to exclude it, there seems little point in excluding the evidence; we might as well let the evidence in and allow judge to give the evidence the probative value that it deserves (Mnookin 2006; Damaška 2006; cf. Ho 2008: 44–46).

Bentham was a strong critic of exclusionary rules. He was much in favour of “freedom of proof” understood as free access to information and the absence of formal rules that restrict such access (Twining 2006: 232, n 65). The direct object of legal procedure is the “rectitude of decision”, by which he means the correct application of substantive law to true findings of facts. The exclusion of relevant evidence—evidence capable of casting light on the truth—is detrimental to this end. Hence, no relevant evidence should be excluded; the only exceptions he would allow are where the evidence is superfluous or its production would involve preponderant delay, expense or vexation (Bentham 1827: Book IX; Bentham 1825: Book VII; Twining 1985: ch. 2). Bentham’s argument has been challenged on various fronts. It is said that he overvalued the pursuit of truth, undervalued procedural fairness and procedural rights, and placed too much faith in officials, underestimating the risk of abuse when they are given discretion unfettered by rules (Twining 1985: 70–71).

Even if we agree with Bentham that rectitude of decision is the aim of legal procedure and that achieving accuracy in fact-finding is necessary to attain this aim, it is not obvious that a rule-based approach to admissibility will undermine this aim in the long run. Schauer has defended exclusionary rules of evidence along a rule-consequentialist line. Having the triers of fact follow rules on certain matters instead of allowing them the discretion to exercise judgment on a case-by-case basis may produce the greatest number of favourable outcomes in the aggregate. It is in the nature of a formal rule that it has to be followed even when doing so might not serve the background reason for the rule. If hearsay evidence is thought to be generally unreliable, the interest of accuracy may be better served overall to require such evidence to be excluded without regard to its reliability in individual cases. Given the imperfection of human reason and our suspicion about the reasoning ability of the fact-finder, allowing decisions to be taken individually on the reliability and admissibility of hearsay evidence might over time produce a larger proportion of misjudgements than on the rule-based approach (Schauer 2006: 180–185; Schauer 2008). However, this argument is based on a large assumption about the likely effects of having exclusionary rules and not having them, and there is no strong empirical basis for thinking that the consequences are or will be as alleged (Goldman 1999: 292–295; Laudan 2006: 121–122).

Other supporters of exclusionary rules build their arguments on a wide range of different considerations. The literature is too vast to enter into details. Here is a brief mention of some arguments. On one theory, some exclusionary rules are devices that serve as incentives for lawyers to produce the epistemically best evidence that is reasonably available (Nance 1988, 2016: 195–201). For example, if lawyers are not allowed to rely on second-hand (hearsay) evidence, they will be forced to seek out better (first-hand) evidence. On another theory, exclusionary rules allocate the risks of error. Again, consider hearsay. The problem with allowing a party to rely on hearsay evidence is that the opponent has no opportunity to cross-examine the original maker of the statement and is thus deprived of an important means of attacking the reliability of the evidence. Exclusionary rules in general insulate the party against whom the evidence is sought to be adduced from the risks of error that the evidence, if admitted, would have introduced. The distribution of such risks is said to be a political decision that should not be left to the discretion of individual fact-finders (Stein 2005; cf. Redmayne 2006 and Nance 2007a: 154–164). It has also been argued that the hearsay rule and the accompanying right to confront witnesses promote the public acceptance and stability of legal verdicts. If the court relies on direct evidence, it can claim superior access to the facts (having heard from the horse’s mouth, so to speak) and this also reduces the risk of new information emerging after the trial to discredit the inference that was drawn from the hearsay evidence (the original maker of the statement might turn up after the trial to deny the truth of the statement that was attributed to him) (Nesson 1985: 1372–1375; cf. Park 1986; Goldman 1999: 282; Goldman 2005: 166–167).

3. Strength of Evidence

The decision whether to allow a party to adduce a particular item of evidence is one that the judge has to make and arises in the course of a trial. Section 2 above dealt with the conditions that must be satisfied for a witness’s testimony, a document or an object to be received as evidence. At the end of the trial, the fact-finder must consider all the evidence that has been presented and reach a verdict. Although verdict deliberation is sometimes subjected to various forms of control through legal devices such as presumptions and corroboration rules, such control is limited and the fact-finder is expected to exercise personal judgment in the evaluation of evidence (Damaška 2019). Having heard or seen the evidence, the fact-finder now has to evaluate or ‘weigh’ it in reaching the verdict. Weight can refer to any of the following three properties of evidence: (a) the probative value of individual items of evidence, (b) the sufficiency of the whole body of evidence adduced at the trial in meeting the standard of proof, or (c) the relative completeness of this body of evidence. The first two aspects of weight are familiar to legal practitioners but the third has been confined to academic discussions. These three ideas are discussed in the same order below.

In reaching the verdict, the trier of fact has to assess the probative value of the individual items of evidence which have been received at the trial. The concept of probative value can also play a role at the prior stage (which was the focus in section 2 ) where the judge has to make a ruling on whether to receive the evidence in the first place. In many legal systems, if the judge finds the probative value of a proposed item of evidence to be low and substantially outweighed by countervailing considerations, such as the risk of causing unfair prejudice or confusion, the judge can refuse to let the jury hear or see the evidence (see, e.g., Rule 403 of the United States’ Federal Rules of Evidence).

The concept of probative value (or, as it is also called, probative force) is related to the concept of relevance. Section 2.1.2 above introduced and examined the claim that the likelihood ratio is the measure of relevance. To recapitulate, the likelihood of an item of evidence, E (in our previous example, the likelihood of a blood type match) given a hypothesis H (that the accused is in fact guilty) is compared with the likelihood of E given the negation of H (that the accused is in fact innocent). Prior to the introduction of E , one may have formed some belief about H based on other evidence that one already has. This prior belief does not affect the likelihood ratio since its computation is based on the alternative assumptions that H is true and that H is false (Kaye 1986a; Kaye and Koehler 2003; cf. Davis and Follette 2002 and 2003). Rulings on relevance are made by the judge when objections of irrelevance are raised in the course of the trial. The relevance of an item of evidence is supposedly assessed on its own, without consideration of other evidence, and, indeed, much of the other evidence may have yet to presented at the point when the judge rules on the relevance of a particular item of evidence (Mnookin 2013: 1544–5). [ 12 ]

Probative value, as with relevance, has been explained in terms of the likelihood ratio (for detailed examples, see Nance and Morris 2002; Finkelstein and Levin 2003). It was noted earlier that evidence is either relevant or not, and, on the prevailing understanding, it is relevant so long as the likelihood ratio deviates from 1:1. But evidence can be more or less probative depending on the value of the likelihood ratio. In our earlier example, the probative value of a blood type match was 1.0:0.5 (or 2:1) as 50% of the suspect population had the same blood type as the accused. But suppose the blood type is less common and only 25% of the suspect population has it. The probative value of the evidence is now 1.0:0.25 (or 4:1). In both cases, the evidence is relevant; but the probative value is greater in the latter than in the former scenario. It is tempting to describe probative value as the degree of relevance but this would be misleading as relevance in law is a binary concept.

There is a second way of thinking about probative value. On the second view, but not on the first, the probative value of an item of evidence is assessed contextually. The probative value of E may be low given one state of the other evidence and substantial given a different body of other evidence (Friedman 1986; Friedman and Park 2003; cf. Davis and Follette 2002, 2003). Where the other evidence shows that a woman had died from falling down an escalator at a mall while she was out shopping, her husband’s history of spousal battery is unlikely to have any probative value in proving that he was responsible for her death. But where the other evidence shows that the wife had died of injuries in the matrimonial home, and the question is whether the injuries were sustained from an accidental fall from the stairs or inflicted by the husband, the same evidence of spousal battery will now have significant probative value.

On the second view, the probative value of an item of evidence ( E ) is not measured simply by the likelihood ratio as it is on the first view. Probative value is understood as the degree to which E increases (or decreases) the probability of the proposition or hypothesis ( H ) in support of (or against) which E is led. The probative value of E is measured by the difference between the probability of H given E (the posterior probability) and the probability of H absent E (the prior probability) (Friedman 1986; James 1941: 699).

Probative value of \(E = P(H | E) - P(H)\)

\(P(H | E)\) (the posterior probability) is derived by applying Bayes’ theorem—that is, by multiplying the prior probability by the likelihood ratio (see discussion in section 3.2.2 below). On the present view, while the likelihood ratio does not itself measure the probative value of E , it is nevertheless a crucial component in the assessment.

A major difficulty with both of the mathematical conceptions of probative value that we have just examined is that for most evidence, obtaining the figures necessary for computing the likelihood ratio is problematic (Allen 1991: 380). Exceptionally, quantitative base rates data exist, as in our blood type example. Where objective data is unavailable, the fact-finder has to draw on background experience and knowledge to come up with subjective values. In our blood type example, a critical factor in computing the likelihood ratio was the percentage of the “suspect population” who had the same blood type as the accused. “Reference class” is the general statistical term for the role that the suspect population plays in this analysis. How should the reference class of “suspect population” be defined? Should we look at the population of the country as a whole or of the town or the street where the alleged murder occurred? What if it occurred at an international airport where most the people around are foreign visitors? Or what if it is shown that both the accused and the victim were at the time of the alleged murder inmates of the same prison? Should we then take the prison population as the reference class? The distribution of blood types may differ according to which reference class is selected. Sceptics of mathematical modelling of probative value emphasize that data from different reference classes will have different explanatory power and the choice of the reference class is open to—and should be subjected to—contextual argument and requires the exercise of judgment; there is no a priori way of determining the correct reference class. (On the reference class problem in legal factfinding, see, in addition to references cited in the rest of this section, Colyvan, Regan, and Ferson 2001; Tillers 2005; Allen and Roberts 2007.)

Some writers have proposed quantifiable ways of selecting, or assisting in the selection, of the appropriate reference class. On one suggestion, the court does not have to search for the optimal reference class. A general characteristic of an adversarial system of trial is that the judge plays a passive role; it is up to the parties to come up with the arguments on which they want to rely and to produce evidence in support of their respective arguments. This adversarial setting makes the reference class problem more manageable as the court need only to decide which of the reference classes relied upon by the parties is to be preferred. And this can be done by applying one of a variety of technical criteria that statisticians have developed for comparing and selecting statistical models (Cheng 2009). Another suggestion is to use the statistical method of “feature selection” instead. The ideal reference class is defined by the intersection of all relevant features of the case, and a feature is relevant if it is correlated to the matter under enquiry (Franklin 2010, 2011: 559–561). For instance, if the amount of drug likely to be smuggled is reasonably believed to co-vary with the airport through which it is smuggled, the country of origin and the time period, and there is no evidence that any other feature is relevant on which data is available, the ideal reference class is the class of drug smugglers passing through that airport originating from that country and during that time period. Both suggestions have self-acknowledged limitations: not least, they depend on the availability of suitable data. Also, as Franklin stresses, while statistical methods “have advice to offer on how courts should judge quantitative evidence”, they do so “in a way that supplements normal intuitive legal argument rather than replacing it by a formula” (Franklin 2010: 22).

The reference class problem is not confined to the probabilistic assessment of the probative value of individual items of evidence. It is a general difficulty with a mathematical approach to legal proof. In particular, the same problem arises on a probabilistic interpretation of the standard of proof when the court has to determine whether the standard is met based on all the evidence adduced in the case. This topic is explored in section 3.2 below but it is convenient at this juncture to illustrate how the reference class problem can also arise in this connection. Let it be that the plaintiff sues Blue Bus Company to recover compensation for injuries sustained in an accident. The plaintiff testifies, and the court believes on the basis of his testimony, that he was run down by a recklessly driven bus. Unfortunately, it was dark at the time and he cannot tell whether the bus belonged to Blue Bus Company. Assume further that there is also evidence which establishes that Blue Bus Company owns 75% of the buses in the town where the accident occurred and the remaining 25% is owned by Red Bus Company. No other evidence is presented. To use the data as the basis for inferring that there is 0.75 probability that the bus involved in the accident was owned by Blue Bus Company would seem to privilege the reference class of “buses operating in the town” over other possible reference classes such as “buses plying the street where the accident occurred” or “buses operating at the time in question” (Allen and Pardo 2007a: 109). Different reference classes may produce very different likelihood ratios. It is crucial how the reference class is chosen and this is ultimately a matter of argument and judgment. Any choice of reference class (other than the class that shares every feature of the particular incident, which is, in effect, the unique incident itself) is in principle contestable.

Critics of the mathematization of legal proof raise this point as an example of inherent limitations to the mathematical modelling of probative value (Allen and Pardo 2007a). [ 13 ] Allen and Pardo propose an alternative, the explanatory theory of legal proof. They claim that this theory has the advantage of avoiding the reference class problem because it does not attempt to quantify probative value (Pardo 2005: 374–383; Pardo and Allen 2008: 261, 263; Pardo 2013: 600–601). Suppose a man is accused of killing his wife. Evidence is produced of his extra-marital affair. The unique probative value of the accused’s infidelity cannot be mathematically computed from statistical base rates of infidelity and uxoricides (husbands murdering wives). In assessing its probative value, the court should look instead at how strongly the evidence of infidelity supports the explanation of the material events put forward by the side adducing the evidence and how strongly it challenges the explanation offered by the opponent. For instance, the prosecution may be producing the evidence to buttress its case that the accused wanted to get rid of his wife so that he could marry his mistress, and the defence may be advancing the alternative theory that the couple was unusual in that they condoned extra-marital affairs and had never let it affect their loving relationship. How much probative value the evidence of infidelity has depends on the strength of the explanatory connections between it and the competing hypotheses, and this is not something that can be quantified.

But the disagreement in this debate is not as wide as it might appear. The critics concede that formal models for evaluating evidence in law may be useful. What they object to is

scholarship arguing … that such models establish the correct or accurate probative value of evidence, and thus implying that any deviations from such models lead to inaccurate or irrational outcomes. (Allen and Pardo 2007b: 308)

On the other side, it is acknowledged that there are limits to mathematical formalisation of evidential reasoning in law (Franklin 2012: 238–9) and that context, argument and judgment do play a role in identifying the reference class (Nance 2007b).

3.2 Sufficiency of Evidence and the Standards of Proof

In the section 3.1 above, we concentrated on the weight of evidence in the sense of probative value of individual items of evidence. The concept of weight can also apply to the total body of evidence presented at the trial; here “weight” is commonly referred to as the “sufficiency of evidence”. [ 14 ] The law assigns the legal burden of proof between parties to a dispute. For instance, at a criminal trial, the accused is presumed innocent and the burden is on the prosecution to prove that he is guilty as charged. To secure a conviction, the body of evidence presented at the trial must be sufficient to meet the standard of proof. Putting this generally, a verdict will be given in favour of the side bearing the legal burden of proof only if, having considered all of the evidence, the fact-finder is satisfied that the applicable standard of proof is met. The standard of proof has been given different interpretations.

On one interpretation, the standard of proof is a probabilistic threshold. In civil cases, the standard is the “balance of probabilities” or, as it is more popularly called in the United States, the “preponderance of evidence”. The plaintiff will satisfy this standard and succeed in his claim only if there is, on all the evidence adduced in the case, more than 0.5 probability of his claim being true. At criminal trials, the standard for a guilty verdict is “proof beyond a reasonable doubt”. Here the probabilistic threshold is thought to be much higher than 0.5 but courts have eschewed any attempt at authoritative quantification. Typically, a notional value, such as 0.9 or 0.95, is assumed by writers for the sake of discussion. For the prosecution to secure a guilty verdict, the evidence adduced at the trial must establish the criminal charge to a degree of probability that crosses this threshold. Where, as in the United States, there is an intermediate standard of “clear and convincing evidence” which is reserved for special cases, the probabilistic threshold is said to lie somewhere between 0.5 and the threshold for proof beyond reasonable doubt.

Kaplan was among the first to employ decision theory to develop a framework for setting the probabilistic threshold that represents the standard of proof. Since the attention in this area of the law tends to be on the avoidance of errors and their undesirable consequences, he finds it convenient to focus on disutility rather than utility. The expected disutility of an outcome is the product of the disutility (broadly, the social costs) of that outcome and the probability of that outcome. Only two options are generally available to the court: in criminal cases, it must either convict or acquit the accused and in civil cases, it has to give judgment either for the plaintiff or for the defendant. At a criminal trial, the decision should be made to convict where the expected disutility of a decision to acquit is greater than the expected disutility of a decision to convict. This is so as to minimize the expected disutilities. To put this in the form of an equation:

P is the probability that the accused is guilty on the basis of all the evidence adduced in the case, Dag is the disutility of acquitting a guilty person and Dci is the disutility of convicting an innocent person. A similar analysis applies to civil cases: the defendant should be found liable where the expected disutility of finding him not liable when he is in fact liable exceeds the expected disutility of finding him liable when he is in fact not liable.

On this approach, a person should be convicted of a crime only where P is greater than:

The same formula applies in civil cases except that the two disutilities ( Dag and Dci ) will have to be replaced by their civil equivalents (framed in terms of the disutility of awarding the judgment to a plaintiff who in fact does not deserve it and disutility of awarding the judgment to a defendant who in fact does not deserve it). On this formula, the crucial determinant of the standard of proof is the ratio of the two disutilities. In the civil context, the disutility of an error in one direction is deemed equal to the disutility of an error in the other direction. Hence, a probability of liability of greater than 0.5 would suffice for a decision to enter judgment against the defendant (see Redmayne 1996: 171). The situation is different at a criminal trial. Dci , the disutility of convicting an innocent person is considered far greater than Dag , the disutility of acquitting a guilty person. [ 15 ] Hence, the probability threshold for a conviction should be much higher than 0.5 (Kaplan 1968: 1071–1073; see also Cullison 1969).

An objection to this analysis is that it is incomplete. It is not enough to compare the costs of erroneous verdicts. The utility of an accurate conviction and the utility of an accurate acquittal should also be considered and factored into the equation (Lillquist 2002: 108). [ 16 ] This results in the following modification of the formula for setting the standard of proof:

Ucg is the utility of convicting the guilty, Uag is the utility of acquitting the guilty, Uai is the utility of acquitting the innocent and Uci the utility of convicting the innocent.

Since the relevant utilities depend on the individual circumstances, such as the seriousness of the crime and the severity of the punishment, the decision-theoretic account of the standard of proof would seem, on both the simple and the modified version, to lead to the conclusion that the probabilistic threshold should vary from case to case (Lillquist 2002; Bartels 1981; Laudan and Saunders 2009; Ribeiro 2019). In other words, the standard of proof should be a flexible or floating one. This view is perceived to be problematic.

First, it falls short descriptively. The law requires the court to apply a fixed standard of proof for all cases within the relevant category. In theory, all criminal cases are governed by the same high standard and all civil cases are governed by the same lower standard. That said, it is unclear whether factfinders in reality adhere strictly to a fixed standard of proof (see Kaplow 2012: 805–809).

The argument is better interpreted as a normative argument—as advancing the claim about what the law ought to be and not what it is. The standard of proof ought to vary from case to case. But this proposal faces a second objection. For convenience, the objection will be elaborated in the criminal setting; in principle, civil litigants have the same two rights that we shall identify. According to Dworkin (1981), moral harm arises as an objective moral fact when a person is erroneously convicted of a crime. Moral harm is distinguished from the bare harm (in the form of pain, frustration, deprivation of liberty and so forth) that is suffered by a wrongfully convicted and punished person. While accused persons have the right not to be convicted if innocent, they do not have the right to the most accurate procedure possible for ascertaining their guilt or innocence. However, they do have the right that a certain weight or importance be attached to the risk of moral harm in the design of procedural and evidential rules that affect the level of accuracy. Accused persons have the further right to a consistent weighting of the importance of moral harm and this further right stems from their right to equal concern and respect. Dworkin’s theory carries an implication bearing on the present debate. It is arguable that to adopt a floating standard of proof would offend the second right insofar as it means treating accused persons differently with respect to the evaluation of the importance of avoiding moral harm. This difference in treatment is reflected in the different level of the risk of moral harm to which they are exposed.

There is a third objection to a floating standard of proof. Picinali (2013) sees fact-finding as a theoretical exercise that engages the question of what to believe about the disputed facts. What counts as “reasonable” for the purposes of applying the standard of proof beyond reasonable doubt is accordingly a matter for theoretical as opposed to practical reasoning. Briefly, theoretical reasoning is concerned with what to believe whereas practical reasoning is about what to do. Only reasons for belief are germane in theoretical reasoning. While considerations that bear on the assessment of utility and disutility provide reasons for action, they are not reasons for believing in the accused’s guilt. Decision theory cannot therefore be used to support a variable application of the standard of proof beyond reasonable doubt.

The third criticism of a flexible standard of proof does not directly challenge the decision-theoretic analysis of the standard of proof. On that analysis, it would seem that the maximisation of expected utility is the criterion for selecting the appropriate probabilistic threshold to apply and it plays no further role in deciding whether that threshold, once selected, is met on the evidence adduced in the particular case. It is not incompatible with the decision-theoretic analysis to insist that the question of whether the selected threshold is met should be governed wholly by epistemic considerations. However, it is arguable that what counts as good or strong enough theoretical reason for judging, and hence believing, that something is true is dependent on the context, such as what is at stake in believing that it is true. More is at stake at a trial involving the death penalty than in a case of petty shop-lifting; accordingly, there should be stronger epistemic justification for a finding of guilt in the first than in the second case. Philosophical literature on epistemic contextualism and on interest-relative accounts of knowledge and justified belief has been drawn upon to support a variant standard of proof (Ho 2008: ch. 4; see also Amaya 2015: 525–531). [ 17 ]

The premise of the third criticism is that the trier of fact has to make a finding on a disputed factual proposition based on his belief in the proposition. This is contentious. Beliefs are involuntary; we cannot believe something by simply deciding to believe it. The dominant view is that beliefs are context-independent; at any given moment, we cannot believe something in one context and not believe it in another. On the other hand, legal fact-finding involves choice and decision making and it is dependent on the context; for example, evidence that is strong enough to justify a finding of fact in a civil case may not be strong enough to justify the same finding in a criminal case where the standard of proof is higher. It has been argued that the fact-finder has to base his findings not on what he believes but what he accepts (Cohen 1991, 1992: 117–125, Beltrán 2006; cf. Picinali 2013: 868–869). Belief and acceptance are propositional attitudes: they are different attitudes that one can have in relation to a proposition. As Cohen (1992: 4) explains:

to accept that p is to have or adopt a policy of deeming, positing or postulating that p —i.e. of including that proposition or rule among one’s premises for deciding what to do or think in a particular context.

Understanding standards of proof in terms of mathematical probabilities is controversial. It is said to raise a number of paradoxes (Cohen 1977; Allen 1986, 1991; Allen and Leiter 2001; Redmayne 2008). Let us return to our previous example. The defendant, Blue Bus Company, owns 75% of the buses in the town where the plaintiff was injured by a recklessly driven bus and the remaining 25% is owned by Red Bus Company. No other evidence is presented. Leaving aside the reference class problem discussed above, there is a 0.75 probability that the accident was caused by a bus owned by the defendant. On the probabilistic interpretation of the applicable standard of proof (that is, the balance of probabilities), the evidence should be sufficient to justify a verdict in the plaintiff’s favour. But most lawyers would agree that the evidence is insufficient. Another familiar hypothetical scenario is set in the criminal context (Nesson 1979: 1192–1193). Twenty five prisoners are exercising in a prison yard. Twenty four of them suddenly set upon a guard and kill him. The remaining prisoner refuses to participate. We cannot in the ensuing confusion identify the prisoner who refrained from the attack. Subsequently, one prisoner is selected randomly and prosecuted for the murder of the guard. Those are the only facts presented at the trial. The applicable standard is proof beyond a reasonable doubt. Assume that the probabilistic threshold of this standard is 0.95. On the statistical evidence, there is a probability of 0.96 that the defendant is criminally liable. [ 18 ] Despite the statistical probability of liability exceeding the threshold, it is widely agreed that the defendant must be acquitted. In both of the examples just described, why is the evidence insufficient and what does this say about legal standards of proof?