Center for Teaching

Group work: using cooperative learning groups effectively.

Many instructors from disciplines across the university use group work to enhance their students’ learning. Whether the goal is to increase student understanding of content, to build particular transferable skills, or some combination of the two, instructors often turn to small group work to capitalize on the benefits of peer-to-peer instruction. This type of group work is formally termed cooperative learning, and is defined as the instructional use of small groups to promote students working together to maximize their own and each other’s learning (Johnson, et al., 2008).

Cooperative learning is characterized by positive interdependence, where students perceive that better performance by individuals produces better performance by the entire group (Johnson, et al., 2014). It can be formal or informal, but often involves specific instructor intervention to maximize student interaction and learning. It is infinitely adaptable, working in small and large classes and across disciplines, and can be one of the most effective teaching approaches available to college instructors.

What can it look like?

What’s the theoretical underpinning, is there evidence that it works.

- What are approaches that can help make it effective?

Informal cooperative learning groups In informal cooperative learning, small, temporary, ad-hoc groups of two to four students work together for brief periods in a class, typically up to one class period, to answer questions or respond to prompts posed by the instructor.

Additional examples of ways to structure informal group work

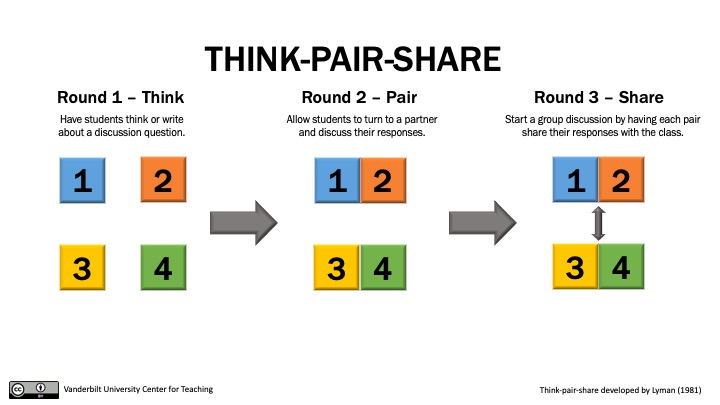

Think-pair-share

The instructor asks a discussion question. Students are instructed to think or write about an answer to the question before turning to a peer to discuss their responses. Groups then share their responses with the class.

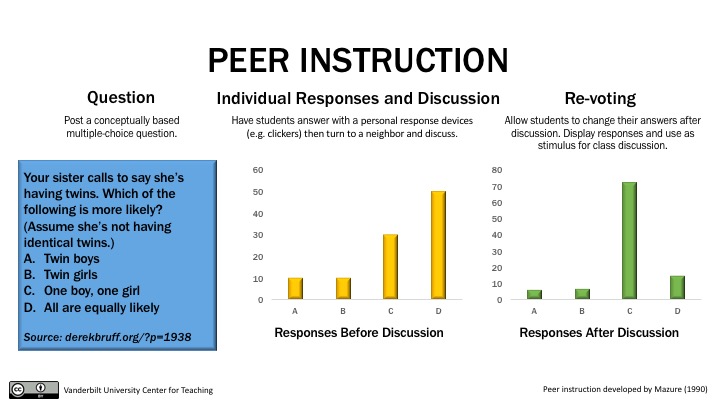

Peer Instruction

This modification of the think-pair-share involves personal responses devices (e.g. clickers). The question posted is typically a conceptually based multiple-choice question. Students think about their answer and vote on a response before turning to a neighbor to discuss. Students can change their answers after discussion, and “sharing” is accomplished by the instructor revealing the graph of student response and using this as a stimulus for large class discussion. This approach is particularly well-adapted for large classes.

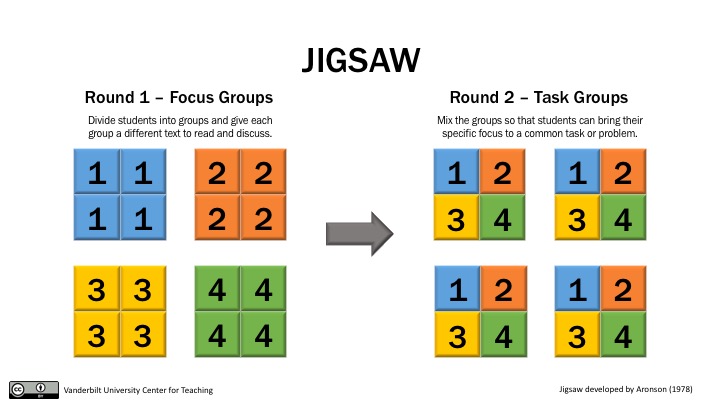

In this approach, groups of students work in a team of four to become experts on one segment of new material, while other “expert teams” in the class work on other segments of new material. The class then rearranges, forming new groups that have one member from each expert team. The members of the new team then take turns teaching each other the material on which they are experts.

Formal cooperative learning groups

In formal cooperative learning students work together for one or more class periods to complete a joint task or assignment (Johnson et al., 2014). There are several features that can help these groups work well:

- The instructor defines the learning objectives for the activity and assigns students to groups.

- The groups are typically heterogeneous, with particular attention to the skills that are needed for success in the task.

- Within the groups, students may be assigned specific roles, with the instructor communicating the criteria for success and the types of social skills that will be needed.

- Importantly, the instructor continues to play an active role during the groups’ work, monitoring the work and evaluating group and individual performance.

- Instructors also encourage groups to reflect on their interactions to identify potential improvements for future group work.

This video shows an example of formal cooperative learning groups in David Matthes’ class at the University of Minnesota:

There are many more specific types of group work that fall under the general descriptions given here, including team-based learning , problem-based learning , and process-oriented guided inquiry learning .

The use of cooperative learning groups in instruction is based on the principle of constructivism, with particular attention to the contribution that social interaction can make. In essence, constructivism rests on the idea that individuals learn through building their own knowledge, connecting new ideas and experiences to existing knowledge and experiences to form new or enhanced understanding (Bransford, et al., 1999). The consideration of the role that groups can play in this process is based in social interdependence theory, which grew out of Kurt Koffka’s and Kurt Lewin’s identification of groups as dynamic entities that could exhibit varied interdependence among members, with group members motivated to achieve common goals. Morton Deutsch conceptualized varied types of interdependence, with positive correlation among group members’ goal achievements promoting cooperation.

Lev Vygotsky extended this work by examining the relationship between cognitive processes and social activities, developing the sociocultural theory of development. The sociocultural theory of development suggests that learning takes place when students solve problems beyond their current developmental level with the support of their instructor or their peers. Thus both the idea of a zone of proximal development, supported by positive group interdependence, is the basis of cooperative learning (Davidson and Major, 2014; Johnson, et al., 2014).

Cooperative learning follows this idea as groups work together to learn or solve a problem, with each individual responsible for understanding all aspects. The small groups are essential to this process because students are able to both be heard and to hear their peers, while in a traditional classroom setting students may spend more time listening to what the instructor says.

Cooperative learning uses both goal interdependence and resource interdependence to ensure interaction and communication among group members. Changing the role of the instructor from lecturing to facilitating the groups helps foster this social environment for students to learn through interaction.

David Johnson, Roger Johnson, and Karl Smith performed a meta-analysis of 168 studies comparing cooperative learning to competitive learning and individualistic learning in college students (Johnson et al., 2006). They found that cooperative learning produced greater academic achievement than both competitive learning and individualistic learning across the studies, exhibiting a mean weighted effect size of 0.54 when comparing cooperation and competition and 0.51 when comparing cooperation and individualistic learning. In essence, these results indicate that cooperative learning increases student academic performance by approximately one-half of a standard deviation when compared to non-cooperative learning models, an effect that is considered moderate. Importantly, the academic achievement measures were defined in each study, and ranged from lower-level cognitive tasks (e.g., knowledge acquisition and retention) to higher level cognitive activity (e.g., creative problem solving), and from verbal tasks to mathematical tasks to procedural tasks. The meta-analysis also showed substantial effects on other metrics, including self-esteem and positive attitudes about learning. George Kuh and colleagues also conclude that cooperative group learning promotes student engagement and academic performance (Kuh et al., 2007).

Springer, Stanne, and Donovan (1999) confirmed these results in their meta-analysis of 39 studies in university STEM classrooms. They found that students who participated in various types of small-group learning, ranging from extended formal interactions to brief informal interactions, had greater academic achievement, exhibited more favorable attitudes towards learning, and had increased persistence through STEM courses than students who did not participate in STEM small-group learning.

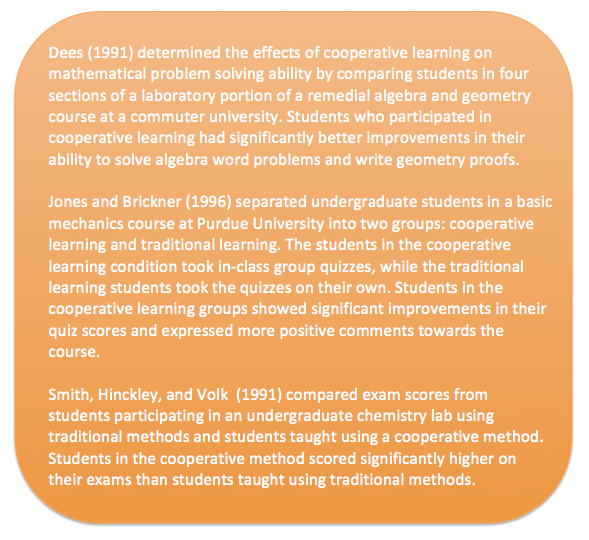

The box below summarizes three individual studies examining the effects of cooperative learning groups.

What are approaches that can help make group work effective?

Preparation

Articulate your goals for the group work, including both the academic objectives you want the students to achieve and the social skills you want them to develop.

Determine the group conformation that will help meet your goals.

- In informal group learning, groups often form ad hoc from near neighbors in a class.

- In formal group learning, it is helpful for the instructor to form groups that are heterogeneous with regard to particular skills or abilities relevant to group tasks. For example, groups may be heterogeneous with regard to academic skill in the discipline or with regard to other skills related to the group task (e.g., design capabilities, programming skills, writing skills, organizational skills) (Johnson et al, 2006).

- Groups from 2-6 are generally recommended, with groups that consist of three members exhibiting the best performance in some problem-solving tasks (Johnson et al., 2006; Heller and Hollabaugh, 1992).

- To avoid common problems in group work, such as dominance by a single student or conflict avoidance, it can be useful to assign roles to group members (e.g., manager, skeptic, educator, conciliator) and to rotate them on a regular basis (Heller and Hollabaugh, 1992). Assigning these roles is not necessary in well-functioning groups, but can be useful for students who are unfamiliar with or unskilled at group work.

Choose an assessment method that will promote positive group interdependence as well as individual accountability.

- In team-based learning, two approaches promote positive interdependence and individual accountability. First, students take an individual readiness assessment test, and then immediately take the same test again as a group. Their grade is a composite of the two scores. Second, students complete a group project together, and receive a group score on the project. They also, however, distribute points among their group partners, allowing student assessment of members’ contributions to contribute to the final score.

- Heller and Hollabaugh (1992) describe an approach in which they incorporated group problem-solving into a class. Students regularly solved problems in small groups, turning in a single solution. In addition, tests were structured such that 25% of the points derived from a group problem, where only those individuals who attended the group problem-solving sessions could participate in the group test problem. This approach can help prevent the “free rider” problem that can plague group work.

- The University of New South Wales describes a variety of ways to assess group work , ranging from shared group grades, to grades that are averages of individual grades, to strictly individual grades, to a combination of these. They also suggest ways to assess not only the product of the group work but also the process. Again, having a portion of a grade that derives from individual contribution helps combat the free rider problem.

Helping groups get started

Explain the group’s task, including your goals for their academic achievement and social interaction.

Explain how the task involves both positive interdependence and individual accountability, and how you will be assessing each.

Assign group roles or give groups prompts to help them articulate effective ways for interaction. The University of New South Wales provides a valuable set of tools to help groups establish good practices when first meeting. The site also provides some exercises for building group dynamics; these may be particularly valuable for groups that will be working on larger projects.

Monitoring group work

Regularly observe group interactions and progress , either by circulating during group work, collecting in-process documents, or both. When you observe problems, intervene to help students move forward on the task and work together effectively. The University of New South Wales provides handouts that instructors can use to promote effective group interactions, such as a handout to help students listen reflectively or give constructive feedback , or to help groups identify particular problems that they may be encountering.

Assessing and reflecting

In addition to providing feedback on group and individual performance (link to preparation section above), it is also useful to provide a structure for groups to reflect on what worked well in their group and what could be improved. Graham Gibbs (1994) suggests using the checklists shown below.

The University of New South Wales provides other reflective activities that may help students identify effective group practices and avoid ineffective practices in future cooperative learning experiences.

Bransford, J.D., Brown, A.L., and Cocking, R.R. (Eds.) (1999). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school . Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Bruffee, K. A. (1993). Collaborative learning: Higher education, interdependence, and the authority of knowledge. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Cabrera, A. F., Crissman, J. L., Bernal, E. M., Nora, A., Terenzini, P. T., & Pascarella, E. T. (2002). Collaborative learning: Its impact on college students’ development and diversity. Journal of College Student Development, 43 (1), 20-34.

Davidson, N., & Major, C. H. (2014). Boundary crossing: Cooperative learning, collaborative learning, and problem-based learning. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 25 (3&4), 7-55.

Dees, R. L. (1991). The role of cooperative leaning in increasing problem-solving ability in a college remedial course. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 22 (5), 409-21.

Gokhale, A. A. (1995). Collaborative Learning enhances critical thinking. Journal of Technology Education, 7 (1).

Heller, P., and Hollabaugh, M. (1992) Teaching problem solving through cooperative grouping. Part 2: Designing problems and structuring groups. American Journal of Physics 60, 637-644.

Johnson, D.W., Johnson, R.T., and Smith, K.A. (2006). Active learning: Cooperation in the university classroom (3 rd edition). Edina, MN: Interaction.

Johnson, D.W., Johnson, R.T., and Holubec, E.J. (2008). Cooperation in the classroom (8 th edition). Edina, MN: Interaction.

Johnson, D.W., Johnson, R.T., and Smith, K.A. (2014). Cooperative learning: Improving university instruction by basing practice on validated theory. Journl on Excellence in College Teaching 25, 85-118.

Jones, D. J., & Brickner, D. (1996). Implementation of cooperative learning in a large-enrollment basic mechanics course. American Society for Engineering Education Annual Conference Proceedings.

Kuh, G.D., Kinzie, J., Buckley, J., Bridges, B., and Hayek, J.C. (2007). Piecing together the student success puzzle: Research, propositions, and recommendations (ASHE Higher Education Report, No. 32). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Love, A. G., Dietrich, A., Fitzgerald, J., & Gordon, D. (2014). Integrating collaborative learning inside and outside the classroom. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 25 (3&4), 177-196.

Smith, M. E., Hinckley, C. C., & Volk, G. L. (1991). Cooperative learning in the undergraduate laboratory. Journal of Chemical Education 68 (5), 413-415.

Springer, L., Stanne, M. E., & Donovan, S. S. (1999). Effects of small-group learning on undergraduates in science, mathematics, engineering, and technology: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 96 (1), 21-51.

Uribe, D., Klein, J. D., & Sullivan, H. (2003). The effect of computer-mediated collaborative learning on solving ill-defined problems. Educational Technology Research and Development, 51 (1), 5-19.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1962). Thought and Language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Teaching Guides

- Online Course Development Resources

- Principles & Frameworks

- Pedagogies & Strategies

- Reflecting & Assessing

- Challenges & Opportunities

- Populations & Contexts

Quick Links

- Services for Departments and Schools

- Examples of Online Instructional Modules

Eberly Center

Teaching excellence & educational innovation, using group projects effectively.

If structured well, group projects can promote important intellectual and social skills and help to prepare students for a work world in which teamwork and collaboration are increasingly the norm. This section provides advice for faculty employing group projects. We examine the following questions:

- What are the benefits of group work?

- What are the challenges of group work, and how can I address them?

- What are best practices for designing group projects?

- How can I compose groups?

- How can I monitor groups?

- How can I assess group work?

- Sample group project tools

This site supplements our 1-on-1 teaching consultations. CONTACT US to talk with an Eberly colleague in person!

Ideas for Great Group Work

Many students, particularly if they are new to college, don’t like group assignments and projects. They might say they “work better by themselves” and be wary of irresponsible members of their group dragging down their grade. Or they may feel group projects take too much time and slow down the progression of the class. This blog post by a student— 5 Reasons I Hate Group Projects —might sound familiar to many faculty assigning in-class group work and longer-term projects in their courses.

We all recognize that learning how to work effectively in groups is an essential skill that will be used by students in practically every career in the private sector or academia. But, with the hesitancy of students towards group work and how it might impact their grade, how do we make group in-class work, assignments, or long-term projects beneficial and even exciting to students?

The methods and ideas in this post have been compiled from Duke faculty who we have consulted with as part of our work in Learning Innovation or have participated in one of our programs. Also included are ideas from colleagues at other universities with whom we have talked at conferences and other venues about group work practices in their own classrooms.

Have clear goals and purpose

Students want to know why they are being assigned certain kinds of work – how it fits into the larger goals of the class and the overall assessment of their performance in the course. Make sure you explain your goals for assigning in-class group work or projects in the course. You may wish to share:

- Information on the importance of developing skills in group work and how this benefits the students in the topics presented in the course.

- Examples of how this type of group work will be used in the discipline outside of the classroom.

- How the assignment or project benefits from multiple perspectives or dividing the work among more than one person.

Some faculty give students the option to come to a consensus on the specifics of how group work will count in the course, within certain parameters. This can help students feel they have some control over their own learning process and and can put less emphasis on grades and more on the importance of learning the skills of working in groups.

Choose the right assignment

Some in-class activities, short assignments or projects are not suitable for working in groups. To ensure student success, choose the right class activity or assignment for groups.

- Would the workload of the project or activity require more than one person to finish it properly?

- Is this something where multiple perspectives create a greater whole?

- Does this draw on knowledge and skills that are spread out among the students?

- Will the group process used in the activity or project give students a tangible benefit to learning in and engagement with the course?

Help students learn the skills of working in groups

Students in your course may have never been asked to work in groups before. If they have worked in groups in previous courses, they may have had bad experiences that color their reaction to group work in your course. They may have never had the resources and support to make group assignments and projects a compelling experience.

One of the most important things you can do as an instructor is to consider all of the skills that go into working in groups and to design your activities and assignments with an eye towards developing those skills.

In a group assignment, students may be asked to break down a project into steps, plan strategy, organize their time, and coordinate efforts in the context of a group of people they may have never met before.

Consider these ideas to help your students learn group work skills in your course.

- Give a short survey to your class about their previous work in groups to gauge areas where they might need help: ask about what they liked best and least about group work, dynamics of groups they have worked in, time management, communication skills or other areas important in the assignment you are designing.

- Allow time in class for students in groups to get to know each other. This can be a simple as brief introductions, an in-class active learning activity or the drafting of a team charter.

- Based on the activity you are designing and the skills that would be involved in working as a group, assemble some links to web resources that students can draw on for more information, such as sites that explain how to delegate and share responsibilities, conflict resolution, or planning a project and time management. You can also address these issues in class with the students.

- Have a plan for clarifying questions or possible problems that may emerge with an assignment or project. Are there ways you can ask questions or get draft material to spot areas where students are having difficulty understanding the assignment or having difficulty with group dynamics that might impact the work later?

Designing the assignment or project

The actual design of the class activity or project can help the students transition into group work processes and gain confidence with the skills involved in group dynamics. When designing your assignment, consider these ideas.

- Break the assignment down into steps or stages to help students become familiar with the process of planning the project as a group.

- Suggest roles for participants in each group to encourage building expertise and expertise and to illustrate ways to divide responsibility for the work.

- Use interim drafts for longer projects to help students manage their time and goals and spot early problems with group projects.

- Limit their resources (such as giving them material to work with or certain subsets of information) to encourage more close cooperation.

- Encourage diversity in groups to spread experience and skill levels and to get students to work with colleagues in the course who they may not know.

Promote individual responsibility

Students always worry about how the performance of other students in a group project might impact their grade. A way to allay those fears is to build individual responsibility into both the course grade and the logistics of group work.

- Build “slack days” into the course. Allow a prearranged number of days when individuals can step away from group work to focus on other classes or campus events. Individual students claim “slack days” in advance, informing both the members of their group and the instructor. Encourage students to work out how the group members will deal with conflicting dates if more than one student in a group wants to claim the same dates.

- Combine a group grade with an individual grade for independent write-ups, journal entries, and reflections.

- Have students assess their fellow group members. Teammates is an online application that can automate this process.

- If you are having students assume roles in group class activities and projects, have them change roles in different parts of the class or project so that one student isn’t “stuck” doing one task for the group.

Gather feedback

To improve your group class activities and assignments, gather reflective feedback from students on what is and isn’t working. You can also share good feedback with future classes to help them understand the value of the activities they’re working on in groups.

- For in-class activities, have students jot down thoughts at the end of class on a notecard for you to review.

- At the end of a larger project, or at key points when you have them submit drafts, ask the students for an “assignment wrapper”—a short reflection on the assignment or short answers to a series of questions.

Further resources

Information for faculty

Best practices for designing group projects (Eberly Center, Carnegie Mellon)

Building Teamwork Process Skills in Students (Shannon Ciston, UC Berkeley)

Working with Student Teams (Bart Pursel, Penn State)

Barkley, E.F., Cross, K.P., and Major, C.H. (2005). Collaborative learning techniques: A handbook for college faculty. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Johnson, D.W., Johnson, R., & Smith, K. (1998). Active learning: Cooperation in the college classroom. Edina, MN: Interaction Book Company.

Thompson, L.L. (2004). Making the team: A guide for managers. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education Inc.

Information for students

10 tips for working effectively in groups (Vancouver Island University Learning Matters)

Teamwork skills: being an effective group member (University of Waterloo Centre for Teaching Excellence)

5 ways to survive a group project in college (HBCU Lifestyle)

Group project tips for online courses (Drexel Online)

Group Writing (Writing Center at UNC-Chapel Hill)

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

fa51e2b1dc8cca8f7467da564e77b5ea

- Make a Gift

- Join Our Email List

Many students have had little experience working in groups in an academic setting. While there are many excellent books and articles describing group processes, this guide is intended to be short and simply written for students who are working in groups, but who may not be very interested in too much detail. It also provides teachers (and students) with tips on assigning group projects, ways to organize groups, and what to do when the process goes awry.

Some reasons to ask students to work in groups

Asking students to work in small groups allows students to learn interactively. Small groups are good for:

- generating a broad array of possible alternative points of view or solutions to a problem

- giving students a chance to work on a project that is too large or complex for an individual

- allowing students with different backgrounds to bring their special knowledge, experience, or skills to a project, and to explain their orientation to others

- giving students a chance to teach each other

- giving students a structured experience so they can practice skills applicable to professional situations

Some benefits of working in groups (even for short periods of time in class)

- Students who have difficulty talking in class may speak in a small group.

- More students, overall, have a chance to participate in class.

- Talking in groups can help overcome the anonymity and passivity of a large class or a class meeting in a poorly designed room.

- Students who expect to participate actively prepare better for class.

Caveat: If you ask students to work in groups, be clear about your purpose, and communicate it to them. Students who fear that group work is a potential waste of valuable time may benefit from considering the reasons and benefits above.

Large projects over a period of time

Faculty asking students to work in groups over a long period of time can do a few things to make it easy for the students to work:

- The biggest student complaint about group work is that it takes a lot of time and planning. Let students know about the project at the beginning of the term, so they can plan their time.

- At the outset, provide group guidelines and your expectations.

- Monitor the groups periodically to make sure they are functioning effectively.

- If the project is to be completed outside of class, it can be difficult to find common times to meet and to find a room. Some faculty members provide in-class time for groups to meet. Others help students find rooms to meet in.

Forming the group

- Forming the group. Should students form their own groups or should they be assigned? Most people prefer to choose whom they work with. However, many students say they welcome both kinds of group experiences, appreciating the value of hearing the perspective of another discipline, or another background.

- Size. Appropriate group size depends on the nature of the project. If the group is small and one person drops out, can the remaining people do the work? If the group is large, will more time be spent on organizing themselves and trying to make decisions than on productive work?

- Resources for students. Provide a complete class list, with current email addresses. (Students like having this anyway so they can work together even if group projects are not assigned.)

- Students that don't fit. You might anticipate your response to the one or two exceptions of a person who really has difficulty in the group. After trying various remedies, is there an out—can this person join another group? work on an independent project?

Organizing the work

Unless part of the goal is to give people experience in the process of goal-setting, assigning tasks, and so forth, the group will be able to work more efficiently if they are provided with some of the following:

- Clear goals. Why are they working together? What are they expected to accomplish?

- Ways to break down the task into smaller units

- Ways to allocate responsibility for different aspects of the work

- Ways to allocate organizational responsibility

- A sample time line with suggested check points for stages of work to be completed

Caveat: Setting up effective small group assignments can take a lot of faculty time and organization.

Getting Started

- Groups work best if people know each others' names and a bit of their background and experience, especially those parts that are related to the task at hand. Take time to introduce yourselves.

- Be sure to include everyone when considering ideas about how to proceed as a group. Some may never have participated in a small group in an academic setting. Others may have ideas about what works well. Allow time for people to express their inexperience and hesitations as well as their experience with group projects.

- Most groups select a leader early on, especially if the work is a long-term project. Other options for leadership in long-term projects include taking turns for different works or different phases of the work.

- Everyone needs to discuss and clarify the goals of the group's work. Go around the group and hear everyone's ideas (before discussing them) or encourage divergent thinking by brainstorming. If you miss this step, trouble may develop part way through the project. Even though time is scarce and you may have a big project ahead of you, groups may take some time to settle in to work. If you anticipate this, you may not be too impatient with the time it takes to get started.

Organizing the Work

- Break up big jobs into smaller pieces. Allocate responsibility for different parts of the group project to different individuals or teams. Do not forget to account for assembling pieces into final form.

- Develop a timeline, including who will do what, in what format, by when. Include time at the end for assembling pieces into final form. (This may take longer than you anticipate.) At the end of each meeting, individuals should review what work they expect to complete by the following session.

Understanding and Managing Group Processes

- Groups work best if everyone has a chance to make strong contributions to the discussion at meetings and to the work of the group project.

- At the beginning of each meeting, decide what you expect to have accomplished by the end of the meeting.

- Someone (probably not the leader) should write all ideas, as they are suggested, on the board, a collaborative document, or on large sheets of paper. Designate a recorder of the group's decisions. Allocate responsibility for group process (especially if you do not have a fixed leader) such as a time manager for meetings and someone who periodically says that it is time to see how things are going (see below).

- What leadership structure does the group want? One designated leader? rotating leaders? separately assigned roles?

- Are any more ground rules needed, such as starting meetings on time, kinds of interruptions allowed, and so forth?

- Is everyone contributing to discussions? Can discussions be managed differently so all can participate? Are people listening to each other and allowing for different kinds of contributions?

- Are all members accomplishing the work expected of them? Is there anything group members can do to help those experiencing difficulty?

- Are there disagreements or difficulties within the group that need to be addressed? (Is someone dominating? Is someone left out?)

- Is outside help needed to solve any problems?

- Is everyone enjoying the work?

Including Everyone and Their Ideas

Groups work best if everyone is included and everyone has a chance to contribute ideas. The group's task may seem overwhelming to some people, and they may have no idea how to go about accomplishing it. To others, the direction the project should take may seem obvious. The job of the group is to break down the work into chunks, and to allow everyone to contribute. The direction that seems obvious to some may turn out not to be so obvious after all. In any event, it will surely be improved as a result of some creative modification.

Encouraging Ideas

The goal is to produce as many ideas as possible in a short time without evaluating them. All ideas are carefully listened to but not commented on and are usually written on the board or large sheets of paper so everyone can see them, and so they don't get forgotten or lost. Take turns by going around the group—hear from everyone, one by one.

One specific method is to generate ideas through brainstorming. People mention ideas in any order (without others' commenting, disagreeing or asking too many questions). The advantage of brainstorming is that ideas do not become closely associated with the individuals who suggested them. This process encourages creative thinking, if it is not rushed and if all ideas are written down (and therefore, for the time-being, accepted). A disadvantage: when ideas are suggested quickly, it is more difficult for shy participants or for those who are not speaking their native language. One approach is to begin by brainstorming and then go around the group in a more structured way asking each person to add to the list.

Examples of what to say:

- Why don't we take a minute or two for each of us to present our views?

- Let's get all our ideas out before evaluating them. We'll clarify them before we organize or evaluate them.

- We'll discuss all these ideas after we hear what everyone thinks.

- You don't have to agree with her, but let her finish.

- Let's spend a few more minutes to see if there are any possibilities we haven't thought of, no matter how unlikely they seem.

Group Leadership

- The leader is responsible for seeing that the work is organized so that it will get done. The leader is also responsible for understanding and managing group interactions so that the atmosphere is positive.

- The leader must encourage everyone's contributions with an eye to accomplishing the work. To do this, the leader must observe how the group's process is working. (Is the group moving too quickly, leaving some people behind? Is it time to shift the focus to another aspect of the task?)

- The leader must encourage group interactions and maintain a positive atmosphere. To do this the leader must observe the way people are participating as well as be aware of feelings communicated non-verbally. (Are individuals' contributions listened to and appreciated by others? Are people arguing with other people, rather than disagreeing with their ideas? Are some people withdrawn or annoyed?)

- The leader must anticipate what information, materials or other resources the group needs as it works.

- The leader is responsible for beginning and ending on time. The leader must also organize practical support, such as the room, chalk, markers, food, breaks.

(Note: In addition to all this, the leader must take part in thc discussion and participate otherwise as a group member. At these times, the leader must be careful to step aside from the role of leader and signal participation as an equal, not a dominant voice.)

Concerns of Individuals That May Affect Their Participation

- How do I fit in? Will others listen to me? Am I the only one who doesn't know everyone else? How can I work with people with such different backgrounds and expericnce?

- Who will make the decisions? How much influence can I have?

- What do I have to offer to the group? Does everyone know more than I do? Does anyone know anything, or will I have to do most of the work myself?

Characteristics of a Group that is Performing Effectively

- All members have a chance to express themselves and to influence the group's decisions. All contributions are listened to carefully, and strong points acknowledged. Everyone realizes that the job could not be done without the cooperation and contribution of everyone else.

- Differences are dealt with directly with the person or people involved. The group identifies all disagreements, hears everyone's views and tries to come to an agreement that makes sense to everyone. Even when a group decision is not liked by someone, that person will follow through on it with the group.

- The group encourages everyone to take responsibility, and hard work is recognized. When things are not going well, everyone makes an effort to help each other. There is a shared sense of pride and accomplishment.

Focusing on a Direction

After a large number of ideas have been generated and listed (e.g. on the board), the group can categorize and examine them. Then the group should agree on a process for choosing from among the ideas. Advantages and disadvantages of different plans can be listed and then voted on. Some possibilities can be eliminated through a straw vote (each group member could have 2 or 3 votes). Or all group members could vote for their first, second, and third choices. Alternatively, criteria for a successful plan can be listed, and different alternatives can be voted on based on the criteria, one by one.

Categorizing and evaluating ideas

- We have about 20 ideas here. Can we sort them into a few general categories?

- When we evaluate each others' ideas, can we mention some positive aspects before expressing concerns?

- Could you give us an example of what you mean?

- Who has dealt with this kind of problem before?

- What are the pluses of that approach? The minuses?

- We have two basic choices. Let's brainstorm. First let's look at the advantages of the first choice, then the disadvantages.

- Let's try ranking these ideas in priority order. The group should try to come to an agreement that makes sense to everyone.

Making a decision

After everyone's views are heard and all points of agreement and disagreement are identified, the group should try to arrive at an agreement that makes sense to everyone.

- There seems to be some agreement here. Is there anyone who couldn't live with solution #2?

- Are there any objections to going that way?

- You still seem to have worries about this solution. Is there anything that could be added or taken away to make it more acceptable? We're doing fine. We've agreed on a great deal. Let's stay with this and see if we can work this last issue through.

- It looks as if there are still some major points of disagreement. Can we go back and define what those issues are and work on them rather than forcing a decision now.

How People Function in Groups

If a group is functioning well, work is getting done and constructive group processes are creating a positive atmosphere. In good groups the individuals may contribute differently at different times. They cooperate and human relationships are respected. This may happen automatically or individuals, at different times, can make it their job to maintain the atmospbere and human aspects of the group.

Roles That Contribute to the Work

Initiating —taking the initiative, at any time; for example, convening the group, suggesting procedures, changing direction, providing new energy and ideas. (How about if we.... What would happen if... ?)

Seeking information or opinions —requesting facts, preferences, suggestions and ideas. (Could you say a little more about... Would you say this is a more workable idea than that?)

Giving information or opinions —providing facts, data, information from research or experience. (ln my experience I have seen... May I tell you what I found out about...? )

Questioning —stepping back from what is happening and challenging the group or asking other specific questions about the task. (Are we assuming that... ? Would the consequence of this be... ?)

Clarifying —interpreting ideas or suggestions, clearing up confusions, defining terms or asking others to clarify. This role can relate different contributions from different people, and link up ideas that seem unconnected. (lt seems that you are saying... Doesn't this relate to what [name] was saying earlier?)

Summarizing —putting contributions into a pattern, while adding no new information. This role is important if a group gets stuck. Some groups officially appoint a summarizer for this potentially powerful and influential role. (If we take all these pieces and put them together... Here's what I think we have agreed upon so far... Here are our areas of disagreement...)

Roles That Contribute to the Atmosphere

Supporting —remembering others' remarks, being encouraging and responsive to others. Creating a warm, encouraging atmosphere, and making people feel they belong helps the group handle stresses and strains. People can gesture, smile, and make eye-contact without saying a word. Some silence can be supportive for people who are not native speakers of English by allowing them a chance to get into discussion. (I understand what you are getting at...As [name] was just saying...)

Observing —noticing the dynamics of the group and commenting. Asking if others agree or if they see things differently can be an effective way to identify problems as they arise. (We seem to be stuck... Maybe we are done for now, we are all worn out... As I see it, what happened just a minute ago.. Do you agree?)

Mediating —recognizing disagreements and figuring out what is behind the differences. When people focus on real differences, that may lead to striking a balance or devising ways to accommodate different values, views, and approaches. (I think the two of you are coming at this from completely different points of view... Wait a minute. This is how [name/ sees the problem. Can you see why she may see it differently?)

Reconciling —reconciling disagreements. Emphasizing shared views among members can reduce tension. (The goal of these two strategies is the same, only the means are different… Is there anything that these positions have in common?)

Compromising —yielding a position or modifying opinions. This can help move the group forward. (Everyone else seems to agree on this, so I'll go along with... I think if I give in on this, we could reach a decision.)

Making a personal comment —occasional personal comments, especially as they relate to the work. Statements about one's life are often discouraged in professional settings; this may be a mistake since personal comments can strengthen a group by making people feel human with a lot in common.

Humor —funny remarks or good-natured comments. Humor, if it is genuinely good-natured and not cutting, can be very effective in relieving tension or dealing with participants who dominate or put down others. Humor can be used constructively to make the work more acceptable by providing a welcome break from concentration. It may also bring people closer together, and make the work more fun.

All the positive roles turn the group into an energetic, productive enterprise. People who have not reflected on these roles may misunderstand the motives and actions of people working in a group. If someone other than the leader initiates ideas, some may view it as an attempt to take power from the leader. Asking questions may similarly be seen as defying authority or slowing down the work of the group. Personal anecdotes may be thought of as trivializing the discussion. Leaders who understand the importance of these many roles can allow and encourage them as positive contributions to group dynamics. Roles that contribute to the work give the group a sense of direction and achievement. Roles contributing to the human atmosphere give the group a sense of cooperation and goodwill.

Some Common Problems (and Some Solutions)

Floundering —While people are still figuring out the work and their role in the group, the group may experience false starts and circular discussions, and decisions may be postponed.

- Here's my understanding of what we are trying to accomplish... Do we all agree?

- What would help us move forward: data? resources?

- Let's take a few minutes to hear everyone's suggestions about how this process might work better and what we should do next.

Dominating or reluctant participants —Some people might take more than their share of the discussion by talking too often, asserting superiority, telling lengthy stories, or not letting others finish. Sometimes humor can be used to discourage people from dominating. Others may rarely speak because they have difficulty getting in the conversation. Sometimes looking at people who don't speak can be a non-verbal way to include them. Asking quiet participants for their thoughts outside the group may lead to their participation within the group.

- How would we state the general problem? Could we leave out the details for a moment? Could we structure this part of the discussion by taking turns and hearing what everyone has to say?

- Let's check in with each other about how the process is working: Is everyone contributing to discussions? Can discussions be managed differently so we can all participate? Are we all listening to each other?

Digressions and tangents —Too many interesting side stories can be obstacles to group progress. It may be time to take another look at the agenda and assign time estimates to items. Try to summarize where the discussion was before the digression. Or, consider whether there is something making the topic easy to avoid.

- Can we go back to where we were a few minutes ago and see what we were trying to do ?

- Is there something about the topic itself that makes it difficult to stick to?

Getting Stuck —Too little progress can get a group down. It may be time for a short break or a change in focus. However, occasionally when a group feels that it is not making progress, a solution emerges if people simply stay with the issue.

- What are the things that are helping us solve this problem? What's preventing us from solving this problem?

- I understand that some of you doubt whether anything new will happen if we work on this problem. Are we willing to give it a try for the next fifteen minutes?

Rush to work —Usually one person in the group is less patient and more action-oriented than the others. This person may reach a decision more quickly than the others and then pressure the group to move on before others are ready.

- Are we all ready-to make a decision on this?

- What needs to be done before we can move ahead?

- Let's go around and see where everyone stands on this.

Feuds —Occasionally a conflict (having nothing to do with the subject of the group) carries over into the group and impedes its work. It may be that feuding parties will not be able to focus until the viewpoint of each is heard. Then they must be encouraged to lay the issue aside.

- So, what you are saying is... And what you are saying is... How is that related to the work here?

- If we continue too long on this, we won't be able to get our work done. Can we agree on a time limit and then go on?

For more information...

James Lang, " Why Students Hate Group Projects (and How to Change That) ," The Chronicle of Higher Education (17 June 2022).

Hodges, Linda C. " Contemporary Issues in Group Learning in Undergraduate Science Classrooms: A Perspective from Student Engagement ," CBE—Life Sciences Education 17.2 (2018): es3.

- Designing Your Course

- A Teaching Timeline: From Pre-Term Planning to the Final Exam

- The First Day of Class

- Group Agreements

- Classroom Debate

- Flipped Classrooms

- Leading Discussions

- Polling & Clickers

- Problem Solving in STEM

- Teaching with Cases

- Engaged Scholarship

- Devices in the Classroom

- Beyond the Classroom

- On Professionalism

- Getting Feedback

- Equitable & Inclusive Teaching

- Advising and Mentoring

- Teaching and Your Career

- Teaching Remotely

- Tools and Platforms

- The Science of Learning

- Bok Publications

- Other Resources Around Campus

University of Bridgeport News

7 Strategies for Taking Group Projects by Storm

It’s day one of the new semester, and you see it…staring ominously from the syllabus, it lurks in eager waiting…haunting unlit corners of your lecture hall, the beast inches closer every class until one day, it strikes — sinking its teeth in. No silver tokens or wooden stakes will save you now. It’s time for mandatory group projects.

For even the most scholarly students, the mere suggestion of a group project can send shivers down the spine. These projects plague the mind with many questions. What if I get stuck with someone who does nothing? Will communication break down into a chaotic mess of emojis? And, sometimes, above all else, why do I have to do this?

So, fellow Purple Knights, let’s turn that stress into success — equip yourself with these 7 strategies to help you make the most of group assignments.

1. Acknowledge your anxiety and self-assess

Let’s take a moment to commemorate the ghosts of group projects past. Remember that paper from history class? The one on the American Revolution? Your whole team was supposed to write it, yet your group dedicated more time to scrolling through TikTok than typing. Oh, and how about that PowerPoint presentation for your accounting class? You know, the one nobody pulled their weight on, shaving a few precious points off your final grade?

Although you should never begin a group project with the attitude that failure is inevitable, being honest with yourself about any anxiety you feel helps repurpose the stress of past projects into lessons with future applicability.

So, when you see a group assignment on your syllabus, don’t panic. Instead, ask yourself a few questions, such as:

- What were some issues I encountered during previous group projects?

- How could these issues have been avoided or addressed?

- Did I give the project my all and contribute to the best of my ability?

- What did I learn about the subject I was studying?

- What did I learn about working with a group?

- More specifically, what did I learn about how I work with others?

If this self-assessment only serves to raise more questions, consider talking to your instructor or visiting the Academic Success Center . Expressing your concern about group work, and consulting with supportive and experienced professionals, can help you kickstart your collaboration with confidence.

2. Assemble your A-Team

Now that your head is in the game, it’s time to assemble the A-Team! Whether your group is self-selected or pre-assigned, first things first — for a cohesive collaboration, every teammate must cooperate.

Think of it like building a boat. Each crewmate takes on a different, albeit pivotal, role to ensure the ship will stay afloat. While some people lay floor plans and foundations, others gather materials, create sails, or complete safety assessments. Although every team member has their own purview, everyone must cooperate to achieve a common goal. If one person drops the ball, the vessel might not be seaworthy. The same goes for your group project — without joint effort, your crew may flounder in the face of challenges.

To take the helm, create team roles with the project’s guidelines in mind. Weigh the academic expectations with the skills and strengths of your teammates. Does one partner have a head for facts and figures? Group Researcher , reporting for duty! How about the group member with an eye for design? PowerPoint Coordinator may be the perfect fit!

Scenario snapshot

You and your best friend want to be in the same group for an English presentation. They’re a stand-up pal and astute problem-solver, but they often slack off on assignments. Let’s turn procrastination into collaboration. How can you help establish a healthy group dynamic without boxing out your bestie?

3. Planning is power

Collaborating on an assignment isn’t as simple as casting roles for each group member. You will also need a plan of attack outlining what must be done (and when).

During your initial group meeting, roll up your sleeves to brainstorm ideas and generate timelines for the different components of your project. To keep all the most vital information in an accessible location, utilize project management tools like Google Docs or Trello — providing a clear, shared resource teammates can refer to when working independently.

What would you do?

It’s been two weeks, and one of your group mates still hasn’t opened the shared document outlining their role and the project schedule. They were attentive when your team first met to discuss the presentation, but you’re concerned the assignment has fallen from their radar. How can you address your concerns?

At University of Bridgeport, your personal and professional success is our priority. Learn more about our comprehensive support services today!

4. keep up communication.

Determining guidelines for group check-ins is essential to success. Whether you’re meeting in person or virtually, it’s critical to establish when, where, and how your team will update one another.

You may even consider setting parameters for your group pow-wows. How long should each check-in last? Should one teammate have the floor during each meeting, or will everyone provide updates? Agreeing on these expectations can facilitate smooth sailing ahead.

Your four-person biology group includes a pair of close friends. Each time your team meets to discuss the project, the duo brings little to the table, filling most of the hour with fits of giggly gossip.

The last group check-in was the biggest bust yet — extending an hour longer than the agreed-upon time due to constant distractions and derailments. The following afternoon, your third partner privately messaged you, expressing the same frustrations you’re feeling. How can you and your partner constructively address this issue with your other teammates?

5. Be fair and flexible…

When collaborating with classmates, it’s crucial to remember that is difficult. With academic, personal, and professional demands competing for space, everybody has more than one ball in the air. If someone on your team needs an extension for their part of an assignment, show grace and understanding — most people are doing their best to meet all the expectations tossed their way, and a little leniency can go a long way.

6. …but remember to set boundaries

Flexibility may be paramount, but have you ever flexed too far? If you’re always happy to go with the flow, your willingness to bend could cause your group to break. If you and your teammates are always cleaning up after one partner, burnout will ensue — potentially leading to an underwhelming final project.

If you have a teammate who isn’t pulling their weight, it’s time to set boundaries and reiterate your group’s agreed-upon expectations. If you’re uncomfortable breaching the topic, consult with your professor. Even if they expect you to start the conversation on your own, they can offer support and strategies for addressing conflicts in your group. Moreover, communicating these concerns keeps your instructor in the loop about your team’s progress.

Last month, you were randomly assigned to group for your nursing project. You were pleasantly surprised by how well it was going — at least, at first. Over the past few weeks, one of your partners has missed every meeting due to a personal problem. While they didn’t disclose the specifics, they’ve missed three deadlines and have been completely incommunicado.

With the deadline quickly approaching, you and your other teammates are starting to sweat. What could you do to help your team overcome this challenge?

7. Celebrate success

Group projects are full of peaks and valleys alike. When you hit “submit” and the game is over, take some time to acknowledge your dedicated team. Collaborative assignments can present an invaluable opportunity to connect with classmates, learn from each other, and create something truly impressive.

While the anxiety of an impending group project can be overwhelming, don’t let it overshadow the fact that these ventures can be rewarding and, dare we say, enjoyable experiences. Furthermore, in our increasingly interconnected world, nurturing your collaborative aptitude provides you with a career-ready skill — sought after by employers across all industries.

At University of Bridgeport, #UBelong. Begin your UB journey today — learn more about becoming a Purple Knight !

How to Get Students Excited About Group Work

Explore more.

- Classroom Management

- Course Design

- Student Engagement

- Student Support

W hen I first introduced a team project in my undergraduate biochemistry course in 2018, I was excited to have my students work together and learn from each other. It was the middle of the term; I had already introduced the course’s core concepts in lectures before putting students in teams of four and asking them to design an experiment to diagnose a metabolic condition. The students had five weeks to complete the project and present it to the rest of the class.

Everything seemed to go well based on student performance. But to my utter disappointment, when I asked students at the end of the term for feedback about the project, I learned they hated it.

Surprisingly, it wasn’t the project itself they disliked. It was having to do it in teams. When I assigned the group project, my focus was solely on the content and what students would learn from it. I assumed that since students must have worked in teams since high school, they would know how to navigate the human aspect of working with others. That wasn’t the case.

While we expect students to carry out high-stakes team projects in higher education, we often don’t explicitly teach them how to work effectively in a team. So I researched how to make working in groups a better experience for my students and developed a short teamwork program that I incorporated into my course the following year.

Here are seven improvements I made to my course to provide a better group-project experience for students.

1. Build teams thoughtfully

Whether you allow students to pick their own teams or assign the teams yourself depends on the context of your course. Three distinct styles exist: groups in which students know nothing about each other, groups in which they are partnered based on similar interests or ability, and groups in which they know a lot about each other already. All of these are valid methods and can lead to successful teams.

Whichever method you use, make it clear to students why you chose it. Is it because you want diversity within the teams ? You want to have equal distribution of skills? You think students are mature enough to select their own partners? Whatever the reason, they will value transparency in your decision-making.

“I assumed that since students must have worked in teams since high school, they would know how to navigate the human aspect of working with others. That wasn’t the case.”

I have tried many methods, but the one that worked best for my students and for me has been sorting students based on their previous performance in the class. Instead of mixing high, low, and middle achievers, I grouped them separately. This is not a common method, but I have found that it allows high achievers to try new things and low achievers to take on more responsibility for their own learning. Students are often surprised by how capable they are by the end, and I always make sure to provide support to all teams as needed.

2. Encourage bonding and sow trust early

Put students into their teams at the start of the term, even if they aren’t starting the project for a few weeks. That way, you can provide them with time and activities to get to know each other, to bond and build relationships. Create a set of tasks that will allow everyone to participate irrespective of their abilities and knowledge in your subject. It is better if the tasks are fun or silly, so students don’t feel judged.

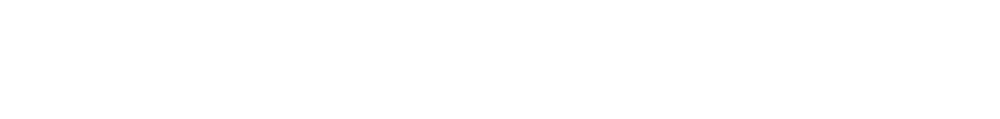

Provide class time to do these bonding activities; this helps students get comfortable with each other and learn about each other, ensuring a certain level of trust between them by the time the project begins. See the image below for an example of a task I do with my students. I give each group 40 spaghetti sticks, tape, and marshmallows and challenge them to build the tallest structure possible.

Students in my biochemistry class build structures with spaghetti sticks, tape, and marshmallows.

In addition to bonding activities, I also provide teams with opportunities leading up to the project to learn from and teach each other. I give students small quizzes to complete on their own, and then again with their groups. Students can discuss the answers, debate why an answer might be incorrect, make decisions together, and get immediate feedback on their performance.

3. Prepare groups to face conflict

Conflict within teams is inevitable, but students tend to avoid it as much as possible and get stressed when it arises. Often, this is because they don’t know how to deal with it. A week after teams have formed in my classes, I run a conflict-resolution workshop. Each group is given a potential conflict that could arise during the term, and they must explore how they would deal with it (see the sidebar for an example exercise). The groups share each conflict and possible solutions with the wider class. Instructors can add to their strategies if they think the students have missed important aspects. Then, if conflict does happen during the semester, students are prepped with solutions they can implement.

EXAMPLE CONFLICT EXERCISE

Here is an example of a scenario I might propose in my conflict-resolution workshop:

One of your teammates has missed two consecutive group meetings and they always have an excuse for not coming. They also seem to ignore messages in the team chat and don’t reply for days. The group is stressed, as they are not sure if this student will complete the assigned tasks. What should the team do?

Since introducing this activity, I have only had to step in to deal with one or two conflicts out of nearly 50 groups per year—and those groups tried other strategies before reaching out for help.

4. Check in with students frequently

One of the biggest struggles for students is time management, so a primary goal of this teamwork program is to teach them its importance—especially when working in groups. A practical way to do this is through regular check ins.

I check in with my students regularly throughout the term to ensure they are meeting consistently and meeting project milestones on schedule. I want to identify any problems as the project progresses, rather than after they’ve made a submission.

Here are a few ways you can do this:

Use interactive polls during class sessions to ask students where in the project they’re at—whether they’ve started or completed certain steps, for example. This gives you an idea of whether any groups might be falling behind.

Talk to students directly when you see them in class; this can make them feel more accountable. Use check ins to remind students of where they should be in the project and provide them opportunities to seek help for any issues or conflicts.

Build draft submission into the project steps. This is a great way to get students started on tasks and make improvements as they go. I provide general feedback to the whole class based on these drafts. You can also have students provide feedback to each other.

5. Provide space for student reflection

Throughout the project, I want students to reflect on the value of teamwork and what they each bring to the table. Every week, I get them to write short reflections answering targeted questions. Here are some examples:

What is your general attitude toward teamwork?

Do you participate in group discussions willingly?

What role do you play in the team?

What is something you learned from your team members you wouldn’t have learned otherwise?

“If student reflections indicate they are struggling with a part of the project, I provide specific guidance and support to the whole class, either during lecture or in online announcements.”

I use these questions to increase students’ self-awareness, which leads to strengthened relationships within teams as well. Some students find the emotional aspects of reflection challenging, and some feel frustrated when there are no immediate actions they can take to address concerns. However, as the instructor, I learn a lot about the students’ experiences and can also implement changes to the course to improve them. For example, if student reflections indicate they are struggling with a part of the project, I provide specific guidance and support to the whole class, either during lecture or in online announcements.

6. Evaluate group functionality at key points

The evaluation of individual and team contributions is an important component of group projects. I evaluate students at two stages of the project timeline (the halfway point and the end) using the same anonymous, online evaluation form . The form has a reflection section accompanied by statements on communication, leadership, accountability, trust, and conflict resolution. Students are asked to rate their own contributions and those of their teammates.

The midpoint evaluation gives students a chance to see their strengths and weaknesses and have time to adjust for the remainder of the project. Constructive feedback can increase self-awareness and motivate students to grow and develop the skills needed to be good team members. It also gives me insight into which students might be struggling or not contributing so I can reach out to help.

7. Strive for improvement with each iteration

This whole program came to be because of my reflections after that first unsuccessful group project. It’s important for you to reflect at the end of the term on how the project process went, too. Think about what worked well and what didn’t and how you can make improvements for the following year. It is important to do this immediately after, while things are still fresh in your mind.

One of the changes I incorporated into my course after reflection was to dedicate a lecture in the first week to introducing the group project and allowing students to ask questions. Previously, I asked students to read the project instructions on their own time, but some students didn’t and others were unclear about expectations.

Introducing the project during the live lecture allowed students to see the full picture of the project and ask questions to clarify things. It also gave me the opportunity to provide tips for group work, such as establishing group roles, setting actionable goals, and running meetings effectively.

Making students feel like part of a community of learners

Since the introduction of this program in 2019, over 96 percent of my students have agreed that they feel like part of a learning community in the course; 56 percent strongly agreed. Over time, more students have mentioned that they found themselves liking biochemistry more than they thought they would when signing up for the class. This course has also had the highest rating within my school for the past five years.

A good team project requires patience, dedication, and commitment by both you and your students. You don’t need to incorporate all these components. Pick and choose the ones you think would have the most impact in your classroom and see the change in attitude toward working in groups.

Nirmani Wijenayake is an education-focused senior lecturer from the School of Biotechnology and Biomolecular Sciences at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. With over 10 years of experience in higher education, she has taught and coordinated large undergraduate courses in biochemistry and cell biology. She won the UNSW Vice Chancellor’s teaching award for outstanding contribution to student learning in 2020 and is a senior fellow of the UK’s higher education academy.

Related Articles

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

- Online Learning

- Effective Online Group Projects

The Key to Effective Online Group Projects: Strategies and Solutions

WVU Online | Wednesday, March 20, 2024

In today's digital classrooms, group work remains as important as ever. However, collaborating effectively in a virtual environment presents unique challenges. In this article, we'll explore strategies that can help you thrive in online group work, giving you the tools and techniques needed to set you up for success.

Setting Up The Online Group Project

When you are preparing for an online group project, planning the logistics of the project is essential to making it a success. Here, we'll dive into challenges that groups may encounter, offering practical recommendations to navigate them effectively.

Understand the Group Dynamics

Take the time to understand each team member's skill sets, schedules, time zones, meeting preferences, and learning style preferences. This understanding will help in allocating tasks efficiently and accommodating everyone's needs. Online students often juggle multiple responsibilities such as jobs and family commitments, so flexibility and clear communication are key to managing busy schedules effectively.

Choosing the Right Communication Tools

Selecting appropriate communication tools is crucial for seamless collaboration. If the professor hasn't specified a platform, the team should collectively decide on tools that suit their needs. Whether it's Slack for real-time messaging, Zoom for video conferencing, or Google Drive for document sharing, ensure that the chosen tools align with the group's workflow, technical abilities, and preferences.

In an online setting, navigating group projects is just one of the many challenges that students face. Understanding these challenges can help teams understand each other and work together more effectively toward their common goals.

Create Standards for the Team

Let's lay down some ground rules to keep your online team project running smoothly. This phase is key for setting expectations and roles within the group, so everyone can start on the same page and be prepared to tackle the project together.

Establish Roles and Responsibilities

Once the team has gotten to know each other, take some time to assess each team member's strengths and skills. Assign roles accordingly—a leader, a coordinator, a researcher, etc. Clarifying these roles upfront helps ensure everyone knows their responsibilities and can contribute effectively.

Build Trust and Rapport

Building trust is essential for effective teamwork. Create a supportive environment where everyone feels valued and respected. Encourage open communication, active listening, and inclusivity. When team members trust each other, collaboration becomes much more seamless.

Determine How and When You’ll Communicate

Clear and consistent communication is key in any collaborative effort, especially in an online setting. Decide on the best methods for staying in touch—whether it's through regular meetings, group chats, or shared documents. Establishing your communication channels early and keeping up with regular check-ins and updates can ensure everyone stays informed and connected throughout the project.

Treat the Project Like a Job

It's important for all team members to take the project seriously. Set deadlines, prioritize tasks, and hold yourselves accountable. Approach it with the dedication and professionalism you would apply to a job. By doing so, you'll set a high standard for the project and maximize your chances of success. These standards and expectations will help lay the groundwork for a productive and collaborative online project.

Managing The Work and Overcoming Challenges

As you dive deeper into your online group project, it's essential to stay organized and prepared to tackle any challenges that may arise. This section focuses on strategies for managing the workload effectively and overcoming obstacles that often come with online collaboration.

Tips for Organizing Work and Delegating Tasks

When it comes to organizing work, it's crucial to distribute tasks among team members so you can divide and conquer. Utilize everyone’s individual strengths and expertise to maximize efficiency and quality. This step isn't just about getting the job done—it's about fostering a sense of ownership and teamwork within the group.

Keeping the Team on Track

Managing deadlines and tracking progress is essential for project success. Using project management tools and strategies can help keep the team organized and accountable. Whether it's using task boards, setting milestones, or scheduling regular check-ins, maintaining momentum is key to achieving your goals.

Navigating Conflicts

Conflict is inevitable in any group setting, but it's how we handle it that matters. To address and resolve conflicts constructively within online groups, encourage open communication, practice respect for one another, and focus on finding mutually beneficial solutions. By addressing conflicts head-on, the team can maintain harmony and focus on the task at hand.

Dealing with Absentee Group Members

Dealing with absent teammates can be tough, but it's all about finding solutions together. Start by reaching out to the missing member, checking in to see if everything's okay and reminding them of their role in the group. If the problem persists, have an open chat with the team to brainstorm ideas on how to address it and how to ensure the missing person’s work is completed.

Teachers can also help by giving groups the power to deal with absenteeism through peer evaluations or the option to remove non-participating members with approval. By working together and keeping communication active, we can make sure the work is equally distributed and the project stays on track.

Establishing Healthy Boundaries

In the digital realm, it's easy for work to bleed into personal time, leading to burnout and resentment. Discuss the importance of setting healthy boundaries within the group, such as establishing norms around response times and respecting each other's schedules. By prioritizing self-care and respect, the team can maintain a positive and sustainable working environment.

Explore Online Learning Options at WVU Online

By understanding the importance of clear communication, defining roles, conflict resolution, and accountability, you've laid a solid foundation for success in online group work.

Whether you're interested in a degree to boost your career, level up your skills, or pursue the passion you've always wanted to study, WVU Online is here to help you reach your goals. Offering a variety of degree programs and certifications, WVU Online provides a supportive environment where you can thrive and grow.

Ready to learn more? Explore our online degree and certification options at WVU Online or connect with an Academic Coach to get more information about our available opportunities. Let’s turn your academic dreams into a reality—one online class at a time!

We're here for you.

Call us, write us, or fill out the request information form. Whichever communication style you prefer, there will be someone from WVU Online on the other end waiting to help.

(800) 253-2762 Email Us Submit a Contact Request Form

Become a problem solver.

Be a decision maker. First, your degree. World-class academics at an exceptional value.

Occasionally a student will encounter an issue with an online course that he or she doesn’t know how to resolve. Should this occur, please visit the link below.

Internal Student Complaint Process

WVU Online West Virginia University PO Box 6800 Morgantown, WV 26506-6800

Phone: (800) 253-2762 Email: [email protected]

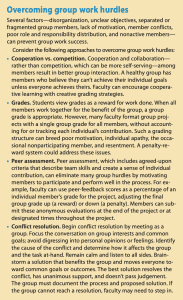

Connect with WVU Online