- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

5 Tips for Managing Successful Overseas Assignments

- Andy Molinsky

- Melissa Hahn

Stay in constant touch and have a plan for their return.

Sending talented employees overseas can be a promising way to leverage the benefits of a global economy. But expatriate assignments can be extremely expensive: up to three times the cost of a person’s typical annual salary, according to some statistics. And despite the investment, many organizations lack the know-how for optimizing the potential benefits, leaving them disappointed with the results. The unfortunate reality is that even companies providing well-crafted relocation packages (including the all-important cultural training) may not have the talent management mechanisms in place to truly leverage the valuable skills expatriate employees gain during their assignments.

- Andy Molinsky is a professor of Organizational Behavior and International Management at Brandeis University and the author of Global Dexterity , Reach , and Forging Bonds in a Global Workforce . Connect with him on LinkedIn and download his free e-booklet of 7 myths about working effectively across cultures .

- Melissa Hahn teaches intercultural communication at American University’s School of International Service. Her new book, Forging Bonds in a Global Workforce (McGraw Hill), helps global professionals build effective relationships across cultures.

Partner Center

Enhancing expatriates’ assignments success: the relationships between cultural intelligence, cross-cultural adaptation and performance

- Open access

- Published: 20 July 2020

- Volume 41 , pages 4291–4311, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Ilaria Setti 1 ,

- Valentina Sommovigo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9273-5706 1 &

- Piergiorgio Argentero 1

23k Accesses

34 Citations

Explore all metrics

Today’s increasingly global marketplace is resulting in more organizations sending employees to work outside their home countries as expatriates. Consequently, identifying factors influencing expatriates’ cross-cultural adjustment at work and performance has become an increasingly important issue for both researchers and firms. Drawing on Kim et al. ( 2008 ), this study examines the critical elements to expatriate success, which are the relationships between cultural intelligence, cross-cultural adjustment at work, and assignment-specific performance. One-hundred and fifty-one expatriates working within the energy sector, who were mainly located in the Middle East completed questionnaires, investigating: cultural intelligence ( Cultural Intelligence Scale ), cross-cultural adjustment ( Expatriate Adjustment Scale ), performance (Expatriate Contextual/Managerial Performance Skills ), cultural distance (Kogut and Singh’ index), length of staying in the host country and international work experience. Findings indicated that the four cultural intelligence components were directly and indirectly (through cross-cultural adjustment at work) associated with performance. The positive relationship between motivational cultural intelligence and cross-cultural adjustment at work was stronger when cultural distance was low, when expatriates were at the beginning of a new international assignment, and when they had lower experience. Organizations can greatly benefit from hiring cross-culturally intelligent expatriates for international assignments, providing their employees with pre-departure training programs aimed at increasing cultural intelligence, and giving them organizational resources and logistical help to support them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Does cultural intelligence matter within cross-cultural teams in hospitality industry? Understanding the role of team dissimilarity climate

Do stays abroad increase intercultural and general competences, affecting employability?

Exploring the Relationship Between International Service Performance and Personal Characteristics in the Latin American Context

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As globalization of trade encourages multinational corporations (MNCs) to operate in different geographic environments (Sambasivan et al. 2013 ), talent mobility has become one of the key channels through which to develop global organizations’ competitive advantages (Tarique and Schuler 2010 ). This requires the presence of a cross-culturally competent workforce that can manage overseas subsidiaries and liaise with foreign affiliates (Froese and Peltokorpi 2011 ). In this context, expatriates are considered as invaluable assets by MNCs (Wu and Ang 2011 ). Consequently, there have been numerous calls in psychology (e.g., Mol et al. 2005 ) for more research aimed at identifying the psychological factors driving expatriates’ cross-cultural adjustment and performance.

In this context, cultural intelligence (CQ) represents an interesting variable since it is a malleable capability which can be developed through cross-cultural experiences (Chao et al. 2017 ) and specific trainings (Leung et al. 2014 ). CQ is defined as “an individual’s competence to function and manage effectively in culturally diverse settings” (Ang and Van Dyne 2008 , p. 3). CQ is conceptualized as a multidimensional construct which includes four main components: metacognitive CQ (i.e., cultural awareness), cognitive CQ (i.e., cultural knowledge), motivational CQ (i.e., motivation and self-efficacy in functioning in diverse cultural settings), and behavioural CQ (i.e., adoption of appropriate behaviours during cross-cultural interactions). Scholars have called for more research on the CQ dimensions (Ang et al. 2011 ) as the four CQ components have been differently associated with specific intercultural effectiveness outcomes (see Rockstuhl and Van Dyne 2018 for a review).

This study responds to this call by analysing the relationships between specific CQ dimensions, cross-cultural adjustment (CCA; i.e., psychological comfort in a foreign country; Black and Gregersen 1999 ) at work and assignment-specific performance. This latter construct, which refers to the ability to accomplish certain assignment specific tasks (e.g., replacement planning; Caligiuri 1997 ), was chosen in this paper as main dependent variable because successfully executing assignment-specific duties is frequently the main constituent of success, which is evaluated by the home office (Earley and Ang 2003 ). Aside from performance, this study focused on work CCA, namely the extent to which expatriates become psychologically comfortable handling assignment duties and meeting performance expectations (Chen et al. 2010 ; Shaffer et al. 2006 ). Work CCA is one of the three dimensions of CCA, together with general (i.e., general living conditions) and interaction (i.e., interactions with locals) components (Black et al. 1991 ). This paper concentrated on work CCA as it is more predictive of performance than the other CCA dimensions (Chew et al. 2019 ).

The role of overall CQ as a meaningful antecedent of overall CCA (e.g., Chen et al. 2014 ; Rockstuhl and Van Dyne 2018 ) and job performance (e.g., Malek and Budhwar 2013 ; Ramalu et al. 2012 ) has been identified, whereas the literature on the role of the four CQ facets in facilitating work CCA is less consistent (e.g., Ott and Michailova 2018a , 2018b ). The literature on the effect of CQ on performance indicates an intricate association between the variables, the relevance of the specific CQ dimensions, and the role of work CCA in this association (ibidem). Thus, while some researchers found a direct positive CQ-performance association (e.g., Chen et al. 2011 ; Lee et al. 2013 ), there is also evidence that the impact of CQ on performance may be mediated by work CCA (e.g., Jyoti and Kour 2017a , 2017b ; Lee et al. 2013 ).

Additionally, a closer look to the literature on the boundary conditions under which specific CQ dimensions may enhance work CCA and, in turn, assignment-specific performance reveal numerous gaps. To fil this gap, this study aimed to analyse how and when specific CQ facets were more - or less - likely to facilitate assignment-specific performance. To this end, this paper concentrated on cultural distance (CD, i.e., the extent to which the culture of destination differs from expatriates’ home country on various values; Shenkar 2001 ), length of stay in the host country and work international experience. Indeed, although some studies analysed the moderating role of CD in the relationships between various individual features and outcomes in the expatriation area (e.g., Chen et al. 2010 ; Zhang 2013 ), the research on the effect of CD on the association between CQ dimensions and work CCA remains limited. Moreover, even though some studies demonstrated that the length of residence in the local country influenced both CQ (e.g., Li et al. 2013 ) and CCA (e.g., Ramalu et al. 2010 ), no previous research, to the best of our knowledge, has investigated the enhancing effect of length of stay on the association between specific CQ assets and work CCA. Furthermore, though some investigations showed that work experience played a moderating role in the CQ-CCA relationship (e.g., Lee and Sukoco 2010 ; Jyoti and Kour 2017a , 2017b ), no study, to our knowledge, has considered the moderated mediated effect of the four CQ dimensions and work experience - through work CCA - on assignment-specific performance.

Therefore, our research questions are as follows: do the four CQ dimensions directly and indirectly, through work CCA, impact on assignment-specific performance? And what are the effects of CD, length of stay in the host country and previous international experience with regard to this? In answering these questions, this paper drew on Kim et al. ( 2008 ) which presented, for the first time, propositions that delineated the relationships between CQ, CCA and performance analysing them together, so that scholars and practitioners could reach a better understanding of each of these. The authors proposed that overall CQ – conceptualized as the result of its four components – would be directly and indirectly, through each of the three dimensions of CCA, associated with overall performance. Additionally, the authors suggested that the CQ-CCA relationship would be positively moderated by CD, so that such relationship would be stronger when CD would be greater.

The main contribution of the present work is to extend this model by analysing whether specific dimensions of CQ – rather than overall CQ - were related to assignment-specific performance – rather than overall performance. Moreover, this research moves an important step forward in the expatriate literature as it identifies, beyond CD – as proposed by the model - other understudied boundary conditions for CQ effects (i.e., work experience and length of stay in the host country).

In doing so, the study was undertaken on the relatively under-investigated population of expatriates working within the energy sector in the Middle East for several reasons. First, some Middle East countries, such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE), have experienced unprecedented growth over the past years (Bealer and Bhanugopan 2014 ). Second, such nations remain relevant economic hubs in the Middle Eastern region, that attract numerous expatriates from Western countries (ibidem), especially within the energy sector (Finaccord 2018 ). For instance, in 2017 Saudi Arabia hosted the largest number of expatriates, whereas in the UAE expatriates constituted the 87.8% of the total population (ibidem). Nevertheless, only a few studies have concentrated on this population. Third, since most of our research respondents were from Latin America, the subsequent national cultural dissimilarities were likely to result in significant CCA difficulties. Thereby, we contribute to literature surrounding organizational behaviour and psychology as well as international human resource management.

In the next section, we provide theoretical arguments for the reasons why each of the four CQ dimensions might be uniquely posited to contribute to expatriates’ assignment-specific performance and work CCA. We describe each component in more detail, and we give rationale for the mediating role of work CCA. Subsequently, we present conceptual logic for our proposed effects of CD, length of stay in the host country and international work experience in the association between specific CQ components and work CCA. After that, we present the sample investigated and the methodology adopted. Then, we report the results and discuss our findings. Finally, we present theoretical and managerial implications, limitations, and suggestions for future research as well as conclusion.

The Relationship between CQ Dimensions and Expatriates’ Assignment-Specific Performance

The construct of CQ attracted ever-increasing attention since other existing formulations of intelligence, such as emotional intelligence (EQ) or social intelligence (SI), do not provide a comprehensive explanation in culturally diverse situations (Groves and Feyerherm 2011 ). Indeed, both EQ and SI are culture bound, such that although these two forms of intelligence may enable individuals to better understand social situations, this does not turn automatically into successful CCA (Caputo et al. 2018 ). Thus, individuals who have high EQ and SI in one culture may not easily adapt to cross-cultural interactions due to misinterpretations of culture-specific situational cues. Conversely, CQ is culture free and regards a general array of abilities particularly relevant on settings characterized by cultural diversity.

Drawing on Kim et al. ( 2008 ), CQ is related to expatriates’ performance, such that culturally intelligent expatriates may successfully function across cultural settings. We present below conceptual logic for our proposed relationships for each of the CQ dimensions with performance, describing each component in more detail.

Meta-cognitive CQ refers to an individual’s level of conscious cultural awareness of - and control over - cognitions during cross-cultural interactions. Self-awareness and cognitive flexibility can promote expatriates’ performance by facilitating their understanding of culturally appropriate role expectations (Ang et al. 2007 ). Indeed, individuals high in meta-cognitive CQ are better at adjusting their existing knowledge to meet changing environmental demands (ibidem). Thus, they can compensate for cognitive capability when previously acquired knowledge is unreliable, avoiding potential problems. Additionally, in unpredictable situations, their meta-cognitive skills provide them with a means by which supplement the lack of overt cues (Fernandez-Duque et al. 2000 ). This may stimulate the adoption of effective solutions to perform well (Tobias and Everson 2002 ). Meta-cognitive CQ may also facilitate expatriates’ performance by enhancing intercultural creative collaboration (Chua et al. 2012 ), conflict management (Caputo et al. 2018 ), decision-making and task performance (Ang et al. 2007 ) as well as knowledge transfer from headquarters to subsidiaries (Vlajčić et al. 2019 ). Thus, we expected the following:

Hypothesis 1a: meta-cognitive CQ will be positively related to assignment-specific performance.

Cognitive CQ refers to an individual’s general knowledge of norms, practices, and conventions in foreign countries gained from personal experiences and education (Ang et al. 2007 ). Expatriates high in cognitive CQ possess sophisticated mental maps of culture, which allow them to anticipate similarities and differences across cultures (Brislin et al. 2006 ). As a result, they may perform well in foreign workplaces because their in-depth knowledge about diverse cultures enables them to reach a greater understanding of cultural expectations. Additionally, such knowledge leads them to adopt culturally appropriate behaviours by facilitating decision-making, cultural judgment (Ang et al. 2007 ), intercultural negotiation (Groves et al. 2015 ), conflict management (Caputo et al. 2018 ) and knowledge transfer from headquarters to subsidiaries (Vlajčić et al. 2019 ). Thereby, we expected the following:

Hypothesis 1b: cognitive CQ will be positively related to assignment-specific performance.

Motivational CQ refers to individual’s ability to direct attention to understand cultural diversity and maintain energy concentrated on learning about - and operating in - new cultural settings, even when situations are challenging (Ang et al. 2007 ). Expatriates high in motivational CQ are motivated intrinsically and by their efficient beliefs of adaptive capabilities to interact with colleagues from different backgrounds (Templer et al. 2006 ). As a result, they may direct their energy toward learning role expectations, positively coping with problems, and striving to address challenges. Motivational CQ may also facilitate expatriates’ performance by easing intercultural collaboration and negotiation (Chua et al. 2012 ), communication effectiveness (Presbitero and Quita 2017 ), integrative information behaviours (Imai and Gelfand 2010 ), and conflict management (Caputo et al. 2018 ). Therefore, we formulated the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1c: motivational CQ will be positively related to assignment-specific performance.

Behavioural CQ reflects the individual’s ability to communicate in a culturally sensitive way and exhibit culturally appropriate (verbal and non-verbal) behaviours when interacting with people from other cultures (Ang et al. 2007 ). This involves having a wide repertoire of overt behavioural responses which fits to a variety of cross-cultural situations, in addition to using culturally appropriate words, body language and conversation style (ibidem). Expatriates high in behavioural CQ can choose appropriate verbal and physical actions when interacting with locals (Ang and Van Dyne 2008 ). This behavioural flexibility may help them to enact culturally appropriate role-related behaviours and meet assignment-specific expectations (ibidem). This may reduce miscommunications and enhance performance (Ng et al. 2012 ; Rose et al. 2010 ). Accordingly, behavioural flexibility was positively related to task performance within intercultural environments (e.g., Chen et al. 2011 ), conflict management (Caputo et al. 2018 ), and intercultural negotiation effectiveness (Groves et al. 2015 ). Then, we hypothesized the following:

Hypothesis 1d: behavioural CQ will be positively related to assignment-specific performance.

The Relationship between CQ Dimensions and Expatriate Adjustment at Work

In line with Kim et al. ( 2008 ), culturally intelligent individuals are better able to adjust to the host country because they are more likely to gain appropriate emotional and informational support through interactions with locals. Then, CQ represents an important factor driving expatriate CCA which may explain individual dissimilarities in adapting to foreign contexts. We provide below theoretical arguments for the reasons why each of the CQ facets might be uniquely positioned to contribute to work CCA.

To date, relatively little research has been conducted to analyse the relationship between meta-cognitive CQ and work CCA, producing mixed results. Indeed, whereas some investigations have found that meta-cognitive CQ exerts a positive influence on work CCA (e.g., Lin et al. 2012 ; Guðmundsdóttir 2015 ), other studies have revealed a nonsignificant effect (e.g., Jyoti and Kour 2015 ; Jyoti et al. 2015 ). Expatriates high in meta-cognitive CQ tend to reflect on cultural dissimilarities before a cross-cultural interaction and develop action plans for how they will interact with locals. This planning prompts cultural learning, problem-solving and interactions with host colleagues, which may reduce uncertainties related to expatriation and, then, facilitate work CCA (Earley and Ang 2003 ; Earley et al. 2006 ). Thus, we proposed the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2a: metacognitive CQ will be positively related to work CCA.

Whereas some studies have identified a positive influence of cognitive CQ on work CCA (e.g., Konanahalli et al. 2014 ), other investigations revealed a non-significant association between the two constructs (e.g., Jyoti and Kour 2015 ). Expatriates high in cognitive CQ have a greater understanding of cross-cultural differences (Brislin et al. 2006 ): they are better able to use their cultural knowledge in making decisions and thinking strategically to overcome transition problems. This, in turn, may improve their ability to adjust to the new workplace (Van Dyne et al. 2012 ). Thus, we expected the following:

Hypothesis 2b: cognitive CQ will be positively related to work CCA.

Expatriates high in motivational CQ are more psychologically prepared to adjust to the work demands expected in culturally diverse workplaces (Chen et al. 2010 ). Thus, they have confidence in their capabilities and intrinsic motivation to adjust to new workplaces (Palthe 2004 ) and display newly learn behaviours (Black et al. 1991 ). This may stimulate their involvement in culturally different modes of working and the accomplishment of their assignment objectives (Lin et al. 2012 ). Accordingly, empirical evidence supported that motivational CQ is positively associated with expatriates’ work CCA (Jyoti and Kour 2015 ; Jyoti et al. 2015 ). Thus, we predicted the following:

Hypothesis 2c: motivational CQ will be positively related to work CCA.

Whereas some studies have revealed that behavioural CQ was non-significantly (e.g., Huff et al. 2014 ; Konanahalli et al. 2014 ) or negatively (e.g., Guðmundsdóttir 2015 ; Malek and Budhwar 2013 ) related to work CCA, other investigations have found a positive association between the two constructs (e.g., Ng et al. 2012 ; Ramalu et al. 2011 ). Expatriates with greater behavioural CQ can use culturally appropriate expressions in communication, in addition to flexibly adapting their behaviour to create comfort zones for the other individual(s) involved in cross-cultural encounters (Earley and Peterson 2004 ). The ability to make such adaptations is likely to result in better work CCA because it facilitates communication with host colleagues, reducing the risk of cross-cultural misunderstandings (Ang et al. 2007 ). Therefore, we hypothesized the following:

Hypothesis 2d: behavioural CQ will be positively related to work CCA.

The Relationship between Expatriates’ Work CCA and Assignment-Specific Performance

When expatriates can successfully adjust to the work domain, they are less stressed and, then, have more personal resources to invest in job duties. In this case, they are likely to feel themselves as culturally competent and build closer relationships with local colleagues (Lee and Sukoco 2010 ; Chen et al. 2010 ). As a result, expatriates who are culturally adjusted to their new workplaces are more likely to perform well on their international assignments than those who are unable to adjust well (Lee and Kartika 2014 ; Wu and Ang 2011 ). Therefore, we expected the following:

Hypothesis 3: work CCA will be positively related to assignment-specific performance.

The Mediating Role of Work CCA

Prior research suggested that CCA might mediate the association between CQ and performance (Kim and Slocum 2008 ; Wang and Takeuchi 2007 ). Despite this development, the empirical evidence on the role played by work CCA in mediating the relationship between specific CQ dimensions and assignment-related tasks has been relatively limited in the expatriate literature, requiring further research (e.g., Jyoti and Kour 2015 ; Lee et al. 2014 ). Kim et al. ( 2008 ) proposed that CQ may work through work CCA to affect expatriate performance as the extent to which expatriates are able to successfully adapt to a new work setting may impact on individual work outcomes. They argued that “a smooth transition across work assignments is critical to an expatriate’s success because the work-role that is executed in the host country may be quite unfamiliar, even though the task is the same as it was in their home country, due to different cultural contexts” (ibidem, p. 76). Therefore, expatriates who have greater CQ are more likely to successfully adjust to their new work setting which, in turn, will enable them to reach high levels of performance. Overall, relevant intercultural skills, such as abilities to revise cultural assumptions (meta-cognitive CQ), elaborate sophisticated metal maps about cultures (cognitive CQ), channel one’s own energies toward functioning (motivational CQ) and exhibit appropriate actions (behavioural CQ) in culturally diverse settings, are all factors which are expected to decrease the misunderstandings in role expectations and facilitate interactions with local colleagues (Ramalu et al. 2012 ). As a result, culturally intelligent expatriates, who are better able to cope with stress related to uncertainties (Sambasivan et al. 2017 ), may more easily feel comfortable in any cultural setting they are working in. Then, work CCA holds the potential to be a proximal intercultural effectiveness outcome which may partially mediate the effects of the four CQ dimensions on more distal effectiveness outcomes, such as assignment specific performance. Hence:

Hypothesis 4: work CCA will mediate the relationship between specific dimensions of CQ (Hp4a: meta-cognitive CQ, Hp4b: cognitive CQ, Hp4c: motivational CQ, Hp4d: behavioural CQ) and assignment-specific performance.

The Moderating Role of Cultural Distance

The individual’s capability to successfully adjust abroad is related to the novelty of the foreign culture. A large difference between the country of origin and the destination requires more transitions, which results in more adjustment difficulties than in a country with a similar culture (Bhaskar-Shrinivas et al. 2005 ). Said differently, adjustment is more challenging when the host country is more culturally distant (Wang and Varma 2019 ). In this context, individual differences may become particularly salient. Indeed, prior investigations revealed that CD moderates the relationship between individual characteristics and various outcomes in the expatriation field, such as effectiveness (Chen et al. 2010 ), adjustment (Zhang 2013 ), and intention to work abroad (Remhof et al. 2013 ). Among individual characteristics, CQ seems to be a variable highly likely to interact with CD on work CCA because of its relevance on settings characterized by cultural diversity. In line with Kim et al. ( 2008 ), “as CD increases, it is expected that CQ would become more, rather than less, critical to expatriates’ adjustment and success” (Kim et al. 2008 , p. 78). Accordingly, CD strengthens the CQ-CCA association since the greater cultural challenges inherent in more culturally distant settings demand more cross-cultural competencies. In this context, those with greater CQ may be better equipped to overcome such challenges and, then, better able to adjust and perform well than those with lower CQ. Thus, we expected the following:

Hypothesis 5: CD will strength the relationship between CQ, in all its dimensions (Hp5a: metacognitive CQ, Hp5b: cognitive CQ, Hp5c: motivational CQ, Hp5d: behavioural CQ), and work CCA, such that the positive effect of CQ dimensions through work CCA on assignment-specific performance will be stronger when the home-host CD will be greater.

The Moderating Role of Length of Residence in the Host Country

Previous investigations on CCA have showed that length of residence in the host country influences CCA (e.g., Li et al. 2013 ; Ramalu et al. 2010 ). According to the U-Curve of CCA framework (Black and Mendenhall 1991 ), the first twelve months in a foreign country are characterized by frustration as the newcomer must deal with living in the host country on a daily basis, overcoming the so-called “cultural shock stage”. CQ may become critical to overcome such highly challenging period because culturally intelligent expatriates can more easily use their cultural knowledge and develop action plans to solve transition problems (meta-cognitive and cognitive CQ; Earley et al. 2006 ). In addition, CQ may be salient because it drives expatriates to establish relationships with local colleagues and vicariously learn about appropriate behaviours (motivational CQ; Mendenhall and Oddou 1985 ). This may lead them to make appropriate behavioural adaptations (behavioural CQ). Thereby, expatriates high in CQ are more likely to learn quickly appropriate behaviours, which may decrease the anxiety related to not knowing how to behave in an unfamiliar environment. As a result, the time required to reach the adjustment stage may be shortened. Additionally, the longer the time spent in the host country, the greater the opportunities to build support systems, reach greater cultural knowledge, and become more efficacious in interacting with locals. This suggests that motivational CQ might be more critical in the initial stages of the adjustment process when individuals have to deal with daily challenges. Thus, we expected the following:

Hypothesis 6: the length of residence in the host country will moderate the relationship between CQ, in all its dimensions (Hp6a: metacognitive CQ, Hp6b: cognitive CQ, Hp6c: motivational CQ, Hp6d: behavioural CQ) and work CCA, such that the positive effect of CQ dimensions through work CCA on assignment-specific performance will be stronger when the length of residence will be lower.

The Moderating Role of International Work Experience

Culturally intelligent expatriates having longer experience of working abroad through vicarious learning can more easily make anticipatory adjustments to the new work setting before they ever experience it (Black et al. 1991 ). In this sense, they may benefit from prior international work experience because they can utilize it as an important source of information which facilitates the formation of realistic work expectations and accurate anticipatory work behavioural adaptations (Church 1982 ). Indeed, expatriates with greater CQ will be more likely to acquire more accurate information from their previous experience as, for instance, they will think critically about cultural knowledge and monitor the quality of that knowledge (Ang et al. 2007 ). This may increase attention and retention processes, leading them to make anticipatory adjustments in behaviours, which would turn out to be appropriate in the host workplace. This means that they will learn lessons from their prior experience and form comprehensive cognitive schemata, which will be useful to predict consequences across a variety of future situations (Takeuchi et al. 2005 ). As a result, prior experience will help expatriates with greater CQ to effectively handle future cross-cultural situations (Lee and Sukoco 2010 ; Shannon and Begley 2008 ). This will decrease the uncertainty and, therefore facilitate, the adjustment process (Black et al. 1991 ), leading to a better performance (Jyoti and Kour 2017a , 2017b ). Conversely, expatriates with lower CQ will be less likely to take advantage from their prior experience as the content of the information will be inaccurate and, then, their actual reproduction of the anticipatorily determined behaviours will prove to be inappropriate in the new workplace (Black et al. 1991 ). Furthermore, although some studies showed that prior experience had an enhancing effect on the CQ-CCA relationship (Lee 2010 ; Lee and Sukoco 2010 ; Jyoti and Kour 2017a , 2017b ), the research has not been consistently supportive (Vlajčić et al. 2019 ). Further to this, research analysing whether prior experience might exert an enhancing effect on the association between the four CQ dimensions and specific domains, such as work CCA, is still limited (Kusumoto 2014 ). Thus, we examined whether prior experience would strengthen the CQ- work CCA relationship, expecting the following:

Hypothesis 7: international work experience will moderate the relationship between CQ, in its dimensions (Hp7a: metacognitive, Hp7b: cognitive, Hp7c: motivational, Hp7d: behavioural), and work CCA, such that the culturally intelligent expatriates with greater experience will adapt more easily to the host workplace and, then, perform more effectively than those with lower experience.

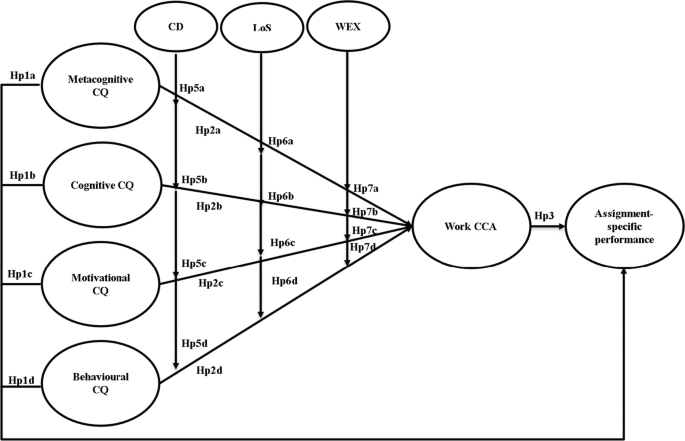

As a conceptual framework, Fig. 1 illustrates our proposed model, incorporating our hypothesized relationships.

Proposed model regarding the relationships between the four components of cultural intelligence (CQ) and assignment-specific performance as well as the moderating role of cultural distance (CD), length of stay in the host country (LoS) and previous international work experience (WEX) in the association between CQ components and cross-cultural adaptation at work (work CCA)

Participants and Procedure

Our research sample consists of employees who were working in a company in the oil and gas industry with an extensive portfolio of projects around the world. Expatriates’ contacts details were gathered from organizational databases. Questionnaires were administrated in English (see Appendix 1 ), the official working language in the company, through a Web-based solution (i.e., mails and online questionnaires). Once respondents voluntarily agreed to participate, we obtained informed consent from them and ensured them the anonymity and confidentiality of their responses. Data were collected in the period between March and May 2018. In total, we contacted four hundred ninety-four expatriates. Of them, one hundred sixty-eight employees completed the survey (34% response rate). We excluded eight participants working in their home country and nine participants because they did not complete at least the 60 % of the survey. The descriptive statistics of the remaining participants ( N = 151) are reported in Table 1 .

Most of research participants were Latin American expatriates assigned to Middle East countries. The Middle East, especially the Muslim and Arab countries of Sud Arabia, Oman and the UAE, represents a hot spot for international assignments (Raghu and Sartawi 2012 ). For instance, according to the data provided by the World Bank, the UAE’s population in 2020 is 9.89 million of whose the 88.52% is constituted by expatriates and immigrants (GMI 2020 ). Arab countries have practices and habits that contrast with those of the Latin American nations. Since the UAE’s culture is masculine in nature, a Latin American expatriate might have difficulties to adjust to a 100% male environment where there is a dress code for men as well (Konanahalli et al. 2012 ). Additionally, during the holy month of Ramadan the Muslim colleagues observe Ramadan fasting rules, which will require Latin Americans to be respectful of such religious observances (ibidem). According to GLOBE Project’s studies on cultural dimensions (House et al. 2004 ), the Middle East cultural cluster is characterized by high scores on collectivism, average scores on assertiveness, human orientation, institutional collectivism, performance orientation and power distance, while for future-orientation, gender egalitarianism and uncertainty avoidance the scores are low (for a detailed description of each cultural dimension see at the following link: https://globeproject.com/study_2004_2007 ). Although similar for some dimensions, the Middle East cluster differs from the Latin American cluster most significantly on the values of institutional collectivism, performance orientation and gender egalitarianism. These differences might translate in striking contrasts in terms of decision making, negotiation, conflict management, leadership styles and so on (e.g., Caputo et al. 2018 ; Caputo et al. 2019 ). In sum, it is likely that Latin American expatriates working in an Arab country will experience significant national cultural dissimilarities, which might lead them to adjustment difficulties.

CQ was assessed by The Cultural Intelligence Scale (Ang et al. 2007 ) which comprises four sub-scales: meta-cognitive CQ (four items, e.g. “I check the accuracy of my cultural knowledge as I interact with people from different cultures”, α = .81 ) ; cognitive CQ (six items, e.g., “ I know the rules for expressing non-verbal behaviour in other cultures”, α = .83); motivational CQ (five items, e.g., “ I enjoy interacting with people from different cultures”, α = .89 ) ; behavioural CQ (five items, e.g., “ I change my verbal behaviour when a cross-cultural interaction requires it”, α = .84 ) . This robust and reliable scale has been utilized by previous studies (e.g., Gozzoli and Gazzaroli 2018 ), confirming the existence of four specific CQ dimensions. Participants indicated how much they agreed with each statement concerning their cultural abilities on a seven-point Likert-type scale (1 = strongly disagree 7 = strongly agree ), where higher scores indicated higher CQ levels.

Work CCA was measured using three items from the Expatriate Adjustment Scale (Black and Stephens 1989 ). Participants rated their adjustment (e.g., “ How adjusted are you to performance standards and expectations in your job? ”, α = .89) on a seven-point Likert-type scale (1 = very unadjusted 7 = very adjusted ), where greater scores indicated greater work CCA. This measure has been consistently validated by previous studies on expatriates (e.g., Bhaskar-Shrinivas et al. 2005 ) confirming its construct validity among culturally different samples.

Assignment-specific performance was evaluated through five items from the Expatriate Contextual/Managerial Performance Skills (Caligiuri 1997 ). Participants were asked to rate their perceived ability in each of the job performance items (e.g., “ Your effectiveness at transferring information across strategic units (e.g., from the host country to headquarters) ”, α = .73) on a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = poor 5 = outstanding ) , where greater scores indicated greater performance.

CD between expatriates’ home country and host country was computed through the index of Kogut and Singh ( 1988 ) in combination with Hofstede’s ( 2001 ) country-specific scores (i.e., power distance, individualism, masculinity, and uncertainty avoidance), consistent with prior studies (e.g., Ng et al. 2019 ).

Length of residence in the host country was measured in months in line with previous researchers (e.g., Chen et al. 2014 ). Participants indicated the period in the current country of destination in months (i.e., How long have you been working in your current country of residence? ).

International work experience was assessed in years, according to previous studies (e.g., Jyoti and Kour 2017a , b ). Respondents indicated how many years they had been working internationally (i.e., How many years had you spent working abroad before this assignment? ).

Control variables . We controlled for marital status (1 = single, 2 = engaged) and education level (1 = high-school, 2 = degree) because previous studies showed that work-family conflict - that is more likely to occur for married expatriates; Kupka and Cathro 2007 - and education level (e.g., Moon et al. 2012 ) may influence CCA; thereby, potentially affecting performance. Furthermore, we controlled for gender (1 = male, 2 = female) and age since prior investigations (e.g., Li et al. 2016 ; Vlajčić et al. 2019 ) have revealed contrasting results about the impact of age and gender on CQ and CCA. Additionally, we recognized that pre-departure cross-cultural training (i.e., Did you have any cross-cultural training before departure? 1 = yes, 2 = no) might be associated with CCA as some studies showed that expatriates who received cross-cultural pre-departure training were more likely to successfully adjust to the host environment (e.g., Evans 2012 ). Since previous studies found that length of stay in the host country and international work experience could affect both CQ (e.g., Wang et al. 2017 ; Moon et al. 2012 ) and CCA (e.g., Ramalu et al. 2010 ; Lee and Kartika 2014 ), we considered the role of these constructs as control variables. Moreover, we acknowledged that CD might impact on CCA, such that the greater the CD, the greater the adjustment difficulties (e.g., Wang and Varma 2019 ). None of the control variables significantly correlated with - or had any significant impact on - the variables of interest within our models, which is why we decided to exclude them from all subsequent analyses and present models without these controls. This is in line with recommended practices (Aguinis and Vandenberg 2014 ).

Descriptive Analyses

We conducted descriptive statistics and correlations among the study variables using SPSS version 20 (Morgan et al. 2012 ). The four CQ dimensions were significantly and positively correlated with each other and with both work CCA and performance (see Table 2 ). The average inter-item correlations between CQ and outcomes was .24, suggesting that items did contain sufficiently unique variance to not be isomorphic with each other (Piedmont 2014 ).

Confirmatory Factor Analyses and Assessment of Common Method Bias

Firstly, using Mplus Version 7 (Muthén and Muthén 1998-2012 ), a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with the maximum likelihood method was carried out to examine the factor structure of the study variables. Results from CFA revealed that the six-factor model (i.e., four CQ dimensions, work CCA, performance) outperformed all the alternative models (χ 2 [335] = 782.70, CFI = .78, TLI = .76, RMSEA = .09, SRMR = .10). However, to obtain a satisfactory fit (χ 2 [330] = 221.59, CFI = .90, TLI = .90, RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .07), it was necessary to take into account the high correlation existing among some items (see Table 3 ). The resulting models were built considering the modification indices which were used in this satisfactory model. Moreover, to control for common method bias, an unmeasured latent method factor was added to the hypothesized CFA model and allowed manifest indicators to load on their respective latent constructs as well as on the method factor (Podsakoff et al. 2012 ). Results indicated that the hypothesized six-factor model yielded a better fit to the data after inclusion of the method factor (Δ χ 2 [302] = 480.28, RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .06, CFI = .91, TLI = .90). The method factor explained only 24% of the variance in the items, which is below the average amount of method variance (25%) reported in self-reported research (Podsakoff et al. 2012 ). Accordingly, common method bias does not appear to have a substantial impact on the present study. Finally, a second order CFA was tested, confirming that CQ loaded into its respective four sub-dimensions (χ 2 [327] = 505.460, CFI = .91, TLI = .90, RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .07).

Hypotheses Testing

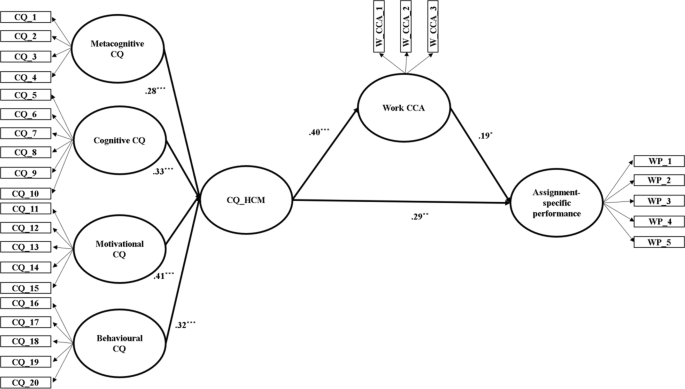

Given our relatively small sample size, the Partial Least Squares (PLS) method, which is a variance-based structural equation modelling, was considered as particularly appropriate to simultaneously test whether each of the four CQ dimensions were related to performance directly and indirectly, as mediated by work CCA. Partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) represents a multivariate modelling technique suitable for the analysis of multiple dependent and independent latent constructs (Mathwick et al. 2008 ). This technique computes relationships between all variables simultaneously and does not necessitate multivariate normality (Zhou et al. 2012 ). Since CQ includes four components, a hierarchical component model (HCM) was created to assess the mediation model (Lohmoller 1989 ). This allowed us to reduce the number of associations in the model, making the model more parsimonious and resistant to collinearity problems (Hair et al. 2017 ). PLS-SEM methodology, utilizing a HCM, enables to examine each component of CQ independently through a higher-order construct that, by theoretical classification of HCM modelling, is a full mediator (Hair et al. 2017 ) in the process of direct and indirect associations between each component of CQ and performance. Using PLS-SEM, it is possible to evaluate each dimension separately, in addition to providing a diverse theoretical explanation for each dimension (Ott and Michailova 2018a , 2018b ). The repeated indicator approach was utilized in a reflective-formative type of HCM using SmartPLS v. 3.2.6. (Ringle et al. 2017 ) to further confirm the measurement model which was previously tested. This model comprises six reflective constructs and one second-order construct which contains latent variable scores for the four dimensions of CQ (a similar methodological approach was also taken by Vlajčić et al. 2019 ). All the items showed statistically significant and satisfactory loadings values (> 0.7; de Pablo González et al. 2014 ). The composite reliabilities of all seven constructs were acceptable as values were above 0.80 and below 0.95 (Nunnally and Bernstein 1994 ; see Table 2 ). The convergence validity was acceptable as all the average variance extracted (AVE) values were above the recommended value of 0.5 (Hair et al. 2010 ). Discriminant validity of our constructs was further confirmed as correlations between each pair of latent constructs do not exceed the square root of each construct’s AVE (Fornell and Larcker 1981 ), apart from the second-order formative construct (CQ-HCM) and the latent constructs it includes, as anticipated by Hair et al. ( 2017 ). These results further confirmed the discriminant validity of our constructs of interest.

Subsequently, the structural model was evaluated using a bootstrapping procedure (10,000 sub-samples; Hernández-Perlines et al. 2016 ). Structural coefficients presented in the PLS model (see Table 4 ) indicated that the dimensions of meta-cognitive ( β = .10, t = 4.13, p < .001), cognitive ( β = .12, t = 3.58, p < .001), motivational ( β = .15, t = 4.12, p < .001), and behavioural ( β = .12, t = 3.68, p < .001) CQ were directly and positively associated with performance. Thereby, Hypotheses 1a , 1b , 1c and 1d were confirmed. Additionally, the dimensions of meta-cognitive ( β = .11, t = 3.39, p < .001), cognitive ( β = .13, t = 4.79, p < .001), motivational ( β = .17, t = 4.30, p < .001), and behavioural ( β = .13, t = 4.18, p < .001) CQ were directly and positively related to work CCA. Thereby, Hypotheses 2a , 2b , 2c and 2d were confirmed. Work CCA ( β = .19, t = 1.96, p < .05) was positively related to performance (see Fig. 2 ). Thereby, Hypothesis 3 was supported. Results from mediation models indicated that work CCA partially mediated the associations between meta-cognitive ( β = .02, t = 1.65, p < .05), cognitive ( β = .03, t = 1.83, p < .05), motivational ( β = .03, t = 1.84, p < .05), and behavioural ( β = .02, t = 1.85, p < .05) CQ and assignment specific performance. Therefore, Hypotheses 4a , 4b , 4c and 4d were confirmed. Moreover, our analysis of the structural model also includes the R 2 and Q 2 as indexes of model consistency and predictive relevance. The indicators of consistency were appropriate, even if CQ and its dimensions explained a weak amount of variation in the constructs of interest (R 2 (CCA) = .26; R 2 (performance) = .25). The predictive relevance of the indicators (Q 2 (CCA) = .70; Q 2 (performance) = .35) were in the large effect size range (Neter et al. 1990 ).

Results from models analysing the mediating effect of work CCA in the relationships between each of CQ dimension and assignment-specific performance

Further, we tested whether the strength of the relationship between CQ and performance through work CCA was conditional on the value of our expected moderators. To this end, we conducted moderated mediation models for each of the CQ dimensions using Mplus Version 7. CD weakened the relationship between motivational CQ and work CCA (β = −.06, p < .05), but no significant interaction terms were revealed for the other CQ dimensions. Then, Hypotheses 5a , 5b and 5d were not supported. The moderated mediation effect of the interaction of motivational CQ and CD through work CCA on performance was significant (see Table 5 ). However, contrary to what expected based on Hypothesis 5c , results indicated that CD weakened the positive relationship between motivational CQ and work CCA, such that the relationship was stronger when CD was low and weaker when CD was high (β = .14, p < .05 for low CD, β = .12, p < .05 for moderate CD, β = .11, p < .05 for high CD).

Length of residence in the host country weakened the positive association between motivational CQ and work CCA (β = −.19, p < .01). The moderated mediation effect of motivational CQ and time of residence in the host country through work CCA on performance was particularly significant for expatriates who had been working in the host country for a shorter time (β = .44, p < .05), but, even if it was still significant, the enhancing effect of length of residence in the host region on the motivational CQ-work CCA relationship decreased with the passage of time (β = .37, p < .05 and β = .31, p < .05; for those working in the foreign country for an average and a longer period of time, respectively; see Table 5 ). Thereby, Hypothesis 6c was supported, whereas Hypotheses 6a , 6b and 6d were rejected.

Experience moderated the relationship between motivational CQ and work CCA (β = −.35, p < .01), but not the associations between the other CQ dimensions. However, contrary to what expected based on Hypothesis 7c , the moderated mediation effect of motivational CQ and experience through work CCA on performance was stronger for expatriates who had lower international work experience (β = .47, p < .05) than for those who had moderate (β = .36, p < .05) or longer (β = .24, p < .05) experience (see Table 5 ). Therefore, Hypotheses 7a , 7b and 7d were rejected and Hypothesis 7c was not confirmed given that the direction was opposed to what expected.

The validity of the hypothesized models was assessed by comparing each of them (i.e., in terms of BIC and AIC comparative indices) with three competing models, as described in detail in Table 6 . The models with motivational CQ were the better-fitting models compared to those which included other CQ dimensions as antecedents.

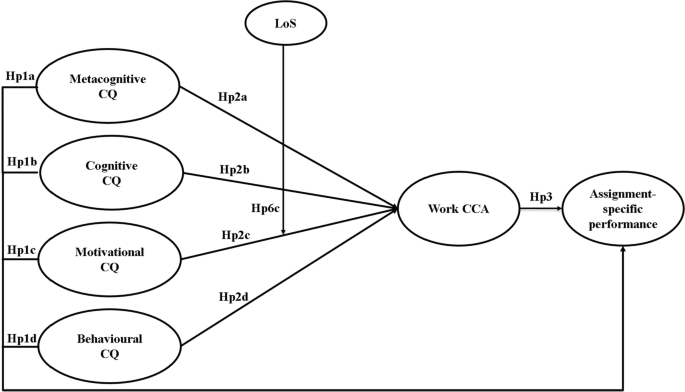

Several findings emerged from this research which make a meaningful contribution to the existing literature on expatriates (see Fig. 3 for an overview of the confirmed hypotheses).

Model representing the hypotheses which were confirmed

First, each of the four CQ components were related to assignment-specific performance, both directly and indirectly, as partially mediated by work CCA. Then, culturally intelligent expatriates are likely to minimize cultural blunders and meet role expectations which, in turn, reduces the likelihood of misunderstandings, increasing performance (Moynihan et al. 2006 ). Moreover, they can successfully adjust to the host workplace, which enables them to channel their energies to improve their performance in assignment-specific tasks (Malek and Budhwar 2013 ; Shaffer et al. 2006 ).

Second, contrary to what expected based on Kim et al. ( 2008 ), CD is more likely to attenuate, rather than amplify, the positive effect of motivational CQ on work CCA in less culturally distant settings, such that the culturally intelligent expatriates are more likely to adjust to the host workplace and, then, perform well when CD is low. A plausible explanation is that when expatriates are confronted with more culturally different workplaces, their motivational CQ might not be sufficient to overcome the challenges posed by more complex assignments due to the greater cultural unfamiliarity (Chen et al. 2010 ; Vlajčić et al. 2018 ; Wang and Varma 2019 ).

Third, the length of residence in the host country weakens the positive relationship between motivational CQ and work CCA, such that motivational CQ is particularly salient when expatriates are in the initial stages of the adjustment process. Said differently, the greater the initial level of motivational CQ, the shorter the time required to adjust to the host country. Therefore, even if motivational CQ facilitates work CCA at any time, expatriates who are at the beginning of their assignment are likely to benefit more from motivational CQ than those who are in the host region from a longer time (Firth et al. 2014 ). Even if they were confronted with failures in their attempts of reproducing the new behaviours, cross-culturally motivated expatriates would be likely to persist at trying to imitate such behaviours longer than those with lower motivational CQ (Bandura 2002 ). This will increase the chances of receiving feedbacks, which will result in displaying appropriate behaviours; thereby, facilitating their adjustment to the new workplace and, then, their performance.

Fourth, motivational CQ is more salient for expatriates who are on their first assignment than for those who have longer experience in international assignments. Even if they have limited experience, the cross-culturally motivated expatriates tend to be more self-confident about their ability to interact with culturally diverse colleagues. They are also more willing to learn about unfamiliar cultures and experiment themselves in imitating culturally appropriate behaviours. Said differently, motivational CQ may counterbalance expatriates’ lack of experience, enabling them to adjust to the host workplace and, then, perform well.

Theoretical Implications

This research has several key contributions to expatriate literature. Firstly, this study extends Kim et al. ( 2008 ) by investigating whether specific CQ dimensions were associated with performance directly and indirectly, as mediated by work CCA. Additionally, by identifying, beyond CD, length of stay in the host country and work experience as boundary conditions for CQ effects, this research helps explain the mixed findings obtained in prior investigations on CQ.

Secondly, this study provides further evidence for the differential role of CQ dimensions (e.g., Rockstuhl and Van Dyne 2018 ) by testing mediating and moderating mechanisms which explain how and when each CQ facet is more - or less - likely to facilitate work CCA and performance.

Thirdly, our findings add to a growing body of literature on expatriate adjustment (e.g., Chew et al. 2019 ; Bhaskar-Shrinivas et al. 2005 ) by confirming the key role of work CCA, which represents a primary factor of interest to MNCs as it is crucial for assignment-specific performance.

Fourthly, this study deepens our understanding of boundary conditions for CQ effects by showing that, of the four CQ factors, only motivational CQ was qualified by CD, length of stay and experience. On the one hand, this suggests that cognitive, metacognitive, and behavioural CQ dimensions had a positive influence on work CCA and, then, assignment-specific performance, regardless of CD, length of stay and experience. In the absence of moderation from such factors, we can confirm that, even if expatriates are on their first assignment, at the beginning of their assignment or assigned to a highly culturally diverse country, a prediction of their success can be based on cognitive, metacognitive and behavioural CQ dimensions. Such dimensions can be particularly useful in promoting performance, since the demanding work setting entails high degrees of culture-related cognitive processing, cultural awareness, and behavioural flexibility to enable for efficient problem solving (Stahl et al. 2009 ). On the other hand, this allows to consider the boundary conditions that provide insights into when motivational CQ has a stronger influence on work CCA and, then, assignment-specific performance. Even motivational CQ is a relevant skill for expatriates at any time of their assignment, expatriates benefited more from motivational CQ when they were working in the host country for a shorter period or when they had lower experience. Motivational CQ plays a peculiar role which differentiates this dimension from the others. Indeed, culturally motivated expatriates are driven to prove themselves in a large quantity of intercultural work situations (Ng et al. 2019 ), despite the challenges experienced at the beginning of a novel assignment. Furthermore, motivational CQ may compensate the lack of work experience by strengthening use of skills and resilience in the face of cultural difficulties (Bandura 2002 ). However, the positive effect of motivational CQ on CCA is necessary yet not sufficient for overcoming the challenges posed by more culturally distant workplaces, as such environments demand less familiar task requirements from expatriates. This makes the effort arouse by motivational CQ less relevant (Chen et al. 2010 ). Overall, this study adds substantially to our understanding of how motivation-related processes may contribute uniquely to expatriate effectiveness.

Practical Implications

The current study has practical implications for MNCs and international human resource management. Firstly, the finding that all CQ dimensions are related to expatriates’ performance suggests that recruiters should select and hire culturally intelligent candidates for international assignments. By evaluating applicants’ CQ and by emphasizing CQ as a critical credential that candidates – especially those with lower international experience - should have, HR representatives can select the most suitable candidates, assigning more cross-culturally motivated expatriates to foreign assignments, if possible, in less culturally distant countries.

Secondly, organizations should provide expatriates with pre-departure training programs aimed at increasing their CQ. For instance, training can offer several scenarios for work so that expatriates may be adequately prepared to comprehend and master different situations (e.g., cultural habits) when facing problems in the host country (Lin et al. 2012 ). Since our findings suggest that motivational CQ is particularly relevant to work CCA, training programs could include a module on motivational CQ (Earley and Peterson 2004 ). For example, training based on dramaturgical exercises, including role plays and simulations about intercultural interactions could be useful tools to build efficacy regarding cross-cultural challenges (ibidem). Furthermore, managers should consider fostering expatriates’ motivation prior to their assignments by emphasizing benefits related to international assignments (e.g., opportunity to develop global career competencies or monetary incentives; Hajro et al. 2017 ) and by stimulating their curiosity about diverse cultures.

Thirdly, considering the mediating role of work CCA in the relationship between CQ and performance, interventions should be implemented to enable expatriates – especially those who are on their first assignment or at the beginning of a new assignment – to receive organizational social support (i.e., from both home and host-country managers and peers) and logistical help (e.g., housing, schooling) to facilitate reaching the adjustment stage (Bhaskar-Shrinivas et al. 2005 ). For instance, companies could consider arranging informal gatherings to help workers build strong bonds with local colleagues and assigning newcomers to experienced mentors (Chen et al. 2010 ). Moreover, MNCs should develop appropriate performance management systems for expatriates and expatriate-host country nationals interaction mechanisms to facilitate work CCA (Wang and Varma 2019 ).

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

This research suffers from some limitations which may give venues for future research.

Some concerns regard the cross-sectional design of our study and the exclusive use of self-reported measures. To decrease the risk of common method bias, we followed Podsakoff et al.’ ( 2012 ) recommendations regarding questionnaire design. Additionally, we used the unmeasured method factor technique, showing that common method variance was not a major issue. Future studies should focus on non-same-source outcomes, collect data from multiple sources (e.g., interviews, observations of actual behaviours, performance ratings from supervisors), adopt a longitudinal design and analyse CQ at the team level (Ott and Michailova 2018a , 2018b ).

Since most of research participants were men, and gender has been previously found to affect the levels of performance among expatriates (e.g., Ramalu et al. 2012 ), this might have partially influenced our findings. However, the gender distribution in our sample is highly representative of expatriate workforce in the analysed sector. Future studies should control for other variables (e.g., openness to experience, having family accompanying in the host country).

A further limitation is related to the fact that possible selection bias due to the voluntary participation into the research cannot be ruled out. It is possible that those who experienced successful CCA experiences were more motivated to respond and, as such, are overrepresented.

Since majority of respondents were from Latin America, and cultural orientation has been revealed to impact differing coping styles, such as conflict management and negotiation styles (e.g., Caputo et al. 2018 ; Caputo et al. 2019 ), this might have partially affected our results. Therefore, more research on larger sample sizes is needed to investigate how the effect of CQ on expatriate performance might vary as a function of individual’s cultural values.

As the nature of global work assignment is expanding beyond the traditional expatriation (e.g., frequent international business travel; Shaffer et al. 2012 ), future studies should investigate the relationships between specific CQ dimensions, work CCA and performance by comparing expatriates employed in different international work arrangements and by collecting data also on international skilled migrants (Hajro et al. 2019 ).

Since CQ, EQ and SI are distinct but overlapping constructs which have been found to positively interact with each other (Crowne 2013 ), future investigations should analyse associations at the subcomponent level of CQ, EQ and SI to identify how specific dimensions of each may affect expatriate performance when the three forms of intelligence are examined together.

Future studies should also analyse conditions under which higher motivational CQ levels might undermine expatriate effectiveness (e.g., through complacency; Chen et al. 2010 ), including situations characterized by ambiguous tasks (e.g., Schmidt and DeShon 2010 ).

Finally, it would be especially important to detect further contextual variables (e.g., group climate, performance management practices; Chen et al. 2010 ; Wang and Varma 2019 ) that may facilitate expatriate performance, either directly or through interactions with specific CQ dimensions.

Even though the current cross-sectional study relied only on self-report measures, it was conducted on the relatively under-investigated population of expatriates working within the energy sector in the Middle East and it addressed some gaps in the literature by disentangling the complex relationship between CQ, CCA and performance. To this end, we tested mediating and moderating mechanisms which explain how and when specific CQ facets were more - or less - likely to facilitate assignment-specific performance. Each CQ dimension had a differential role in contributing to assignment-specific performance, directly and through work CCA. Conversely, of the four CQ factors, only motivational CQ was qualified by CD, length of stay and international work experience. Our findings indicated that motivational CQ was particularly salient in overcoming work CCA difficulties for expatriates who were at the beginning of their international assignment and who had lower experience. Moreover, motivational CQ related more positively to expatriate work CCA in less culturally distant countries. We conclude with the hope that our theoretical contributions will stimulate additional multilevel and longitudinal research on factors influencing work CCA and performance to gather further knowledge about cross-cultural management.

Aguinis, H., & Vandenberg, R. J. (2014). An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure: Improving research quality before data collection. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior., 1 (1), 569–595. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091231 .

Article Google Scholar

Ang, S., & Van Dyne, L. (2008). Handbook of cultural intelligence: Theory, measurement, and application . Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, Inc. ISBN: 9780765622624.

Google Scholar

Ang, S., Van Dyne, L., Koh, C., Ng, K. Y., Templer, K. J., Tay, C., & Chandrasekar, N. A. (2007). Cultural intelligence: Its measurement and effects on cultural judgment and decision making, cultural adaptation and task performance. Management and Organization Review, 3 (3), 335–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8784.2007.00082.x .

Ang, S., Van Dyne, L., & Tan, I. (2011). Cultural intelligence. In R. J. Sternberg & S. B. Kaufman (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook on intelligence . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press ISBN: 9780521739115.

Bandura, A. (2002). Social cognitive theory in cultural context. Applied Psychology, 51 (2), 269–290.

Bealer, D., & Bhanugopan, R. (2014). Transactional and transformational leadership behaviour of expatriate and national managers in the UAE: A cross-cultural comparative analysis. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25 (2), 293–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.826914 .

Bhaskar-Shrinivas, P., Harrison, D. A., Shaffer, M. A., & Luk, D. M. (2005). Input-based and time-based models of international adjustment: Meta-analytic evidence and theoretical extensions. Academy of Management Journal, 48 (2), 257–281. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.16928400 .

Black, J. S., & Gregersen, H. B. (1999). The right way to manage expats. Harvard Business Review, 77 (2), 52–53.

Black, J. S., & Mendenhall, M. (1991). The U-curve adjustment hypothesis revisited: A review and theoretical framework. Journal of International Business Studies, 22 (2), 225–247 https://www.jstor.org/stable/155208 .

Black, J. S., & Stephens, G. K. (1989). The influence of the spouse on American expatriate adjustment and intent to stay in Pacific rim overseas assignments. Journal of Management, 15 (4), 529–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/%2F014920638901500403 .

Black, J. S., Mendenhall, M., & Oddou, G. (1991). Toward a comprehensive model of international adjustment: An integration of multiple theoretical perspectives. Academy of Management Review, 16 (2), 291–317. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1991.4278938 .

Brislin, R., Worthley, R., & Macnab, B. (2006). Cultural intelligence: Understanding behaviors that serve people’s goals. Group & Organization Management, 31 (1), 40–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601105275262 .

Caligiuri, P. M. (1997). Assessing expatriate success: Beyond just “being there”. In D. M. Saunders & Z. Aycan (Eds.), New approaches to employee management (Vol. 4, pp. 245–260). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press ISBN: 9780762303113.

Caputo, A., Ayoko, O. B., & Amoo, N. (2018). The moderating role of cultural intelligence in the relationship between cultural orientations and conflict management styles. Journal of Business Research, 89 , 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.03.042 .

Caputo, A., Ayoko, O. B., Amoo, N., & Menke, C. (2019). The relationship between cultural values, cultural intelligence and negotiation styles. Journal of Business Research, 99 , 23–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.02.011 .

Chao, M. M., Takeuchi, R., & Farh, J. L. (2017). Enhancing cultural intelligence: The roles of implicit culture beliefs and adjustment. Personnel Psychology, 70 (1), 257–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12142 .

Chen, G., Kirkman, B. L., Kim, K., & Farh, C. I. C. (2010). When does cross-cultural motivation enhance expatriate effectiveness? A multi-level investigation of the moderating roles of subsidiary support and cultural distance. Academy of Management Journal, 53 (5), 1110–1130. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.54533217 .

Chen, A. S. Y., Lin, Y. C., & Sawangpattanakul, A. (2011). The relationship between cultural intelligence and performance with the mediating effect of culture shock: A case from Philippine laborers in Taiwan. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35 (2), 246–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.09.005 .

Chen, A. S. Y., Wu, I. H., & Bian, M. D. (2014). The moderating effects of active and agreeable conflict management styles on cultural intelligence and cross-cultural adjustment. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 14 (3), 270–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595814525064 .

Chew, E, Y., Ghurburn, A., Terspstra-Tong, J, L., & Perera, H, K. (2019). Multiple intelligence and expatriate effectiveness: The mediating roles of cross-cultural adjustment. The International Journal of Human Resource Management , 1-33. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1616591 .

Chua, R. Y., Morris, M. W., & Mor, S. (2012). Collaborating across cultures: Cultural metacognition and affect-based trust in creative collaboration. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 118 (2), 116–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2012.03.009 .

Church, A. T. (1982). Sojourner adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 91 (3), 540–572. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.91.3.540 .

Crowne, K. A. (2013). Cultural exposure, emotional intelligence, and cultural intelligence: An exploratory study. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 13 (1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595812452633 .

de Pablo González, J. D. S., Pardo, I. P. G., & Perlines, F. H. (2014). Influence factors of trust building in cooperation agreements. Journal of Business Research, 67 (5), 710–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.11.032 .

Earley, P. C., & Ang, S. (2003). Cultural intelligence: Individual interactions across cultures . Palo Alto: Stanford University Press ISBN: 9780804743129.

Book Google Scholar

Earley, P. C., & Peterson, R. S. (2004). The elusive cultural chameleon: Cultural intelligence as a new approach to intercultural training for the global manager. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 3 (1), 100–115. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2004.12436826 .

Earley, P. C., Ang, S., & Tan, J. (2006). Cultural intelligence: Developing cultural intelligence at work . Palo Alto: Stanford University Press ISBN: 9780804771726.

Evans, E, H. (2012). Expatriate success: Cultural intelligence and personality as predictors for cross-cultural adjustment (doctoral dissertation, the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga).

Fernandez-Duque, D., Baird, J. A., & Posner, M. I. (2000). Executive attention and metacognitive regulation. Consciousness and Cognition, 9 (2), 288–307. https://doi.org/10.1006/ccog.2000.0447 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Finaccord (2018). Global expatriates: size, segmentation and forecast for the worldwide market. Available from http://finaccord.com/BlankSite/media/Catalog/Prospectus/report_prospectus _APG_GEP.pdf.

Firth, B. M., Chen, G., Kirkman, B. L., & Kim, K. (2014). Newcomers abroad: Expatriate adaptation during early phases of international assignments. Academy of Management Journal, 57 (1), 280–300. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.0574 .

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18 (1), 39–50.

Froese, F. J., & Peltokorpi, V. (2011). Cultural distance and expatriate job satisfaction. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 35 (1), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2010.10.002 .

GMI (2020). United Arab Emirates population statistics (2020). Available from https://www.globalmediainsight.com/blog/uae-population-statistics/

Gozzoli, C., & Gazzaroli, D. (2018). The cultural intelligence scale: A contribution to the Italian validation. Frontiers in Psychology, 9 , 1183. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01183 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Groves, K. S., & Feyerherm, A. E. (2011). Leader cultural intelligence in context: Testing the moderating effects of team cultural diversity on leader and team performance. Group & Organization Management, 36 (5), 535–566. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601111415664 .

Groves, K. S., Feyerherm, A., & Gu, M. (2015). Examining cultural intelligence and cross-cultural negotiation effectiveness. Journal of Management Education, 39 (2), 209–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562914543273 .

Guðmundsdóttir, S. (2015). Nordic expatriates in the US: The relationship between cultural intelligence and adjustment. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 47 , 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.05.001 .

Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., & Anderson, R. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective . Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education.

Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., & Thiele, K. O. (2017). Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45 (5), 616–632.

Hajro, A., Gibson, C. B., & Pudelko, M. (2017). Knowledge exchange processes in multicultural teams: Linking organizational diversity climates to teams’ effectiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 60 (1), 345–372. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0442

Hajro, A., Stahl, G. K., Clegg, C. C., & Lazarova, M. B. (2019). Acculturation, coping, and integration success of international skilled migrants: An integrative review and multilevel framework. Human Resource Management Journal, 29 (3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12233 .

Hernández-Perlines, F., Moreno-García, J., & Yañez-Araque, B. (2016). The mediating role of competitive strategy in international entrepreneurial orientation. Journal of Business Research, 69 (11), 5383–5389.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations . Thousand Oaks: Sage ISBN: 9780803973244.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (Eds.). (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies . Thousand Oaks: Sage publications.

Huff, K. C., Song, P., & Gresch, E. B. (2014). Cultural intelligence, personality, and cross-cultural adjustment: A study of expatriates in Japan. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 38 , 151–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.08.005 .

Imai, L., & Gelfand, M. J. (2010). The culturally intelligent negotiator: The impact of cultural intelligence on negotiation sequences and outcomes. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 112 (2), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2010.02.001 .

Jyoti, J., & Kour, S. (2015). Assessing the cultural intelligence and task performance equation: Mediating role of cultural adjustment. Cross Cultural Management, 22 (2), 236–258. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCM-04-2013-0072 .

Jyoti, J., & Kour, S. (2017a). Factors affecting cultural intelligence and its impact on job performance: Role of cross-cultural adjustment, experience and perceived social support. Personnel Review, 46 (4), 767–791. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-12-2015-0313 .

Jyoti, J., & Kour, S. (2017b). Cultural intelligence and job performance: An empirical investigation of moderating and mediating variables. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 17 (3), 305–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595817718001 .

Jyoti, J., Kour, S., & Bhau, S. (2015). Assessing the impact of cultural intelligence on job performance: Role of cross-cultural adaptability. Journal of IMS Group, 12 (1), 23–33.

Kim, K., & Slocum, J. W. (2008). Individual differences and expatriate assignment effectiveness: The case of US-based Korean expatriates. Journal of World Business, 43 (1), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2007.10.005 .

Kim, K., Kirkman, B. L., & Chen, G. (2008). Cultural intelligence and international assignment effectiveness: A conceptual model and preliminary findings. In S. Ang & L. Van Dyne (Eds.), Handbook of cultural intelligence: Theory, measurement, and applications (pp. 71–90). Armonk: M.E. Sharpe ISBN:9780765622624.

Kogut, B., & Singh, H. (1988). The effect of national culture on the choice of entry mode. Journal of International Business Studies, 19 (3), 411–432. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490394 .

Konanahalli, A., Oyedele, L. O., Coates, R., von Meding, J., & Spillane, J. (2012). International projects and cross-cultural adjustments of British expatriates in Middle East: A qualitative investigation of influencing factors. Construction Economics and Building, 12 (3), 31–54. https://doi.org/10.5130/AJCEB.v12i3.2628 .

Konanahalli, A., Oyedele, L., Spillane, J., Coates, R., Von Meding, J., & Ebohon, J. (2014). Cross-cultural intelligence: Its impact on British expatriate adjustment on international construction projects. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 7 (3), 423–448. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMPB-10-2012-0062 .

Kupka, B., & Cathro, V. (2007). Desperate housewives–social and professional isolation of German expatriated spouses. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18 (6), 951–968. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190701320908 .

Kusumoto, M. (2014). The role of expatriates in cross-subsidiary collaboration. In D. A. Vazquez-Brust, J. Sarkis, & J. J. Cordeiro (Eds.), Collaboration for sustainability and innovation: A role for sustainability driven by the global south? (pp. 43–62). Dordrecht: Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Lee, L. Y. (2010). Multiple intelligences and the success of expatriation: The roles of contingency variables. African Journal of Business Management, 4 (17), 3793–3804 Retrieved from http://www.academicjournals.org/AJBM .

Lee, L. Y., & Kartika, N. (2014). The influence of individual, family, and social capital factors on expatriate adjustment and performance: The moderating effect of psychology contract and organizational support. Expert Systems with Applications, 41 (11), 5483–5494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2014.02.030 .

Lee, L. Y., & Sukoco, B. M. (2010). The effects of cultural intelligence on expatriate performance: The moderating effects of international experience. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21 (7), 963–981. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585191003783397 .