Essay on Language Development in Early Childhood

Language development essay introduction, stages language development, promoting child language development, concepts of child language development, conclusion of language development essay, reference list.

Language development refers to the process of deliberate communication using sounds, gestures, or symbols which can be understood by other people (Machado, 1985). Language is double perspectives process which forms the basis for other forms of learning. These two aspects include communicating information, and listening to others (Training Module, 2007).

Existing theories acknowledge early childhood as a period during which physical and cognitive developmental processes occur rapidly. These developments form the basis upon which personal success will depend. Language development is one such process that fully depends on the factors presented during this phase of personal growth (Otto, 2010).

Children undergo various stages in their acquisition of language skills. The following phases depicts a typical sequences through which the skills develops, although their are diversities in the pattern of growth from child to child (Corporation for National Services [CNS], U.S. Department of Education, U.S. department of Health and Human Services, 1997, cited in Training Module, 2007).

- Stage 1: – concerns a newborn, whereby it responds to sounds including voices through cries, smiles and coos.

- Stage 2: – concern infant aged between 3 to 8 months; the time during which he or she begins to play with sounds, as well as babbling to others in conjunction to self. Also, in this stage language development is expressed through the waving of arms and kicking of legs.

- Stage 3: – concerns children aged between 8 to 12 months and she or he understands and can react to basic words and signs.

- Stage 4: – deals with children of age 12 to 18 months, the period during which a normal child starts to utter basic words and to follow very basic instructions. In addition, a normal child knows its name, and can chatter with a sequence of syllables that mimic expressions.

- Stage 5: – concerns children aged between 18 to 24 months old; the level at which a child can construct two-word phrases, and imitate words and gestures of the grown-ups. It can also ask as well as answer general queries.

The process of promoting language development in children must take into consideration the development stage of the child. The following are some of the ways through which a child’s parent or caregiver can promote language development pertaining to the stage of development (Training Module, 2007).

- Newborn: Reaction to the child’s cries indicates to the child that s/he can communicate something to you and get a response (Lagoni et al, 1989, cited in Training Module, 2007).

- 3 to 8 months: it is encouraged that during this stage, the child’s custodian sings to the child while changing his or her diaper. Also, it has been discovered that playing peek-a-boo to the infant enhance language development (CNS et al., cited in Training Module, 2007). Also, the caregiver or parent is encouraged to describe daily routines to the child while performing them (Machado, 1985).

- 8 to 12 months: During this stage it is commended that the parent or caregiver uses the baby’s name repeatedly, perhaps by incorporating the name in simple rhythmical expressions or songs so that she or he can start to recognize it. , (CNS et al., 1997, cited in Training Module, 2007). Also, Machado (1985) recommends giving names to the toys, foods, and other objects surrounding the child.

- 12 to 18 months: – caregiver is advised to entice the child to converse on a toy telephone (CNS et al., 1997, cited in Training Module, 2007). Also, caregiver or parent should present rhymes and finger games to the child (Lagoni et al., 1989, cited in Training Module, 2007).

- 18 to 24 months: during this stage parent or caregiver is encouraged to talk about the previous day’s events, and what will transpire the next day.

There are five concepts of language development which emerge in children’s receptive and communicative language processes. The receptive language skills maturity precedes and lay the foundation for the development of expressive language process. The following paragraphs will explore these concepts of language development in children (Otto, 2010).

To begin with, the phonetic development in toddlerhood involves their ability to express their viewpoints, and constructions of phonemes. Phonemes refers to “a speech sound that distinguishes one word from another, e.g. the sounds “d” and “t” in the words “bid” and “bit.” A phoneme is the smallest phonetic unit that can carry meaning” [Encarta Dictionary].

This concept of language development begins to express during toddlerhood when she or he begins to articulate a range of terms. At first, the child’s pronunciation is unsteadily characterized with day to day variations, and in some cases shorter intervals. In addition, some variations have been observed between children in regard of the mastering of certain syllable (Otto, 2010).

Secondly, semantic language development in infancy entails initial connection of speech to meaning, conception and receptive semantic ability, direct and vivid events, symbol development signifying speech, and expressive semantic ability. On the other hand, the concept of semantic language development presents between the age 1 and 2. At this stage, the toddler possesses a range of 20 to 170 terms in his or her useful vocabulary.

Semantic development depicts variation from child to child depending on their respective familial experiences and background. While the child’s language will undergo gradual transition with age, the idiomorphs will still be retained in the child’s verbal expressions. In their hyperactive exploration of their environment, toddlers discover the identity of people and objects (Otto, 2010).

Furthermore, semantic understanding of toddles and arising literacy, increasingly progress during the toddler stage of a child’s language development process. Also, the child consciousness of environmental features and meaning, like stop signs, brand on food packets, and McDonalds’s logos increases. This consciousness of written symbols is normally expressed in their behaviors with inscribed materials within their familial environment (Otto, 2010).

Thirdly, the concept of syntactic language development on infants concerns the syntactic understanding and story book experiences. Conventionally, infants who are engaged in story book experiences with parent or caregiver get exposed to more complex syntactic arrangement relative those involved in routine conversational environment.

Noteworthy, as infants approach age 1, their verbal and non-verbal participation increase. On the other side, syntactic learning development in toddlers involves syntactic organization in telegraphic speech, mastering of pronouns, and emergent literacy coupled with syntactic ability (Otto, 2010).

Fourthly, the concept of morphemic language development in infants is influenced by phonemic ability. Development of morphemic understanding is dependent upon the skill to identify sound differences related with inflectional morphemes such as; tense indicators, plurals, and possessiveness.

Thus, receptive understanding of the meaning transforming features of morphemic develops with the experiences of spoken and read language. In addition, the development of morphemes skill gets clearer when toddlers start to exercise language. This stage is significant in development of morphemic understanding in regard that noun verb compatibility in English impact on the use of inflectional morphemes (Otto, 2010).

Language development in children is largely dependent on the characteristic of the environment within which the child grows. Experiences of a child determine the rate at which a child develops language skills. The degree of parent or caregiver interaction with a child plays a very significant role in a child language development. Also, health issues can slow a child language understanding.

Otto, B. W. (2010) Language Development in Early Childhood Education (3rd Edition). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education Inc.

Machado, J. M. (2010). Early childhood experiences in language arts: early literacy. Belmont, U.S.; Cengage learning.

Training Module. (2007). Language Development of Infants and Toddlers . HighReach learning.

- Language and Its Relation to Cognition

- Does Global English Mean Linguistic Holocaust?

- Cognitive Linguistics: Semantic Networks Assimilation

- Syntactic Properties of Phrasal Verbs in English

- Critical Summary: “The time course of semantic and syntactic processing in Chinese sentence comprehension: Evidence from eye movements” by Yang, Suiping, Hsuan-Chih and Rayner

- Effects of Text Messaging on English Language

- Language Accommodation

- Christiane Nord Translation Theory: Functions and Elements Analytical Essay

- The Significance of Language: “Mother Tongue”

- Perceiving Culture Through the Language

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, July 24). Language Development in Early Childhood. https://ivypanda.com/essays/language-development-in-early-childhood/

"Language Development in Early Childhood." IvyPanda , 24 July 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/language-development-in-early-childhood/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Language Development in Early Childhood'. 24 July.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Language Development in Early Childhood." July 24, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/language-development-in-early-childhood/.

1. IvyPanda . "Language Development in Early Childhood." July 24, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/language-development-in-early-childhood/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Language Development in Early Childhood." July 24, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/language-development-in-early-childhood/.

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Language Acquisition Theory

Henna Lemetyinen

Postdoctoral Researcher

BSc (Hons), Psychology, PhD, Developmental Psychology

Henna Lemetyinen is a postdoctoral research associate at the Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust (GMMH).

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul McLeod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul McLeod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Language is a cognition that truly makes us human. Whereas other species do communicate with an innate ability to produce a limited number of meaningful vocalizations (e.g., bonobos) or even with partially learned systems (e.g., bird songs), there is no other species known to date that can express infinite ideas (sentences) with a limited set of symbols (speech sounds and words).

This ability is remarkable in itself. What makes it even more remarkable is that researchers are finding evidence for mastery of this complex skill in increasingly younger children.

Infants as young as 12 months are reported to have sensitivity to the grammar needed to understand causative sentences (who did what to whom; e.g., the bunny pushed the frog (Rowland & Noble, 2010).

After more than 60 years of research into child language development, the mechanism that enables children to segment syllables and words out of the strings of sounds they hear and to acquire grammar to understand and produce language is still quite an enigma.

Behaviorist Theory of Language Acquisition

One of the earliest scientific explanations of language acquisition was provided by Skinner (1957). As one of the pioneers of behaviorism , he accounted for language development using environmental influence, through imitation, reinforcement, and conditioning.

In this view, children learn words and grammar primarily by mimicking the speech they hear and receiving positive feedback for correct usage.

Skinner argued that children learn language based on behaviorist reinforcement principles by associating words with meanings. Correct utterances are positively reinforced when the child realizes the communicative value of words and phrases.

For example, when the child says ‘milk’ and the mother smiles and gives her some. As a result, the child will find this outcome rewarding, enhancing the child’s language development (Ambridge & Lieven, 2011).

Over time, through repetition and reinforcement, they refine their linguistic abilities. Critics argue this theory doesn’t fully explain the rapid pace of language acquisition nor the creation of novel sentences.

Chomsky Theory of Language Development

However, Skinner’s account was soon heavily criticized by Noam Chomsky, the world’s most famous linguist to date.

In the spirit of the cognitive revolution in the 1950s, Chomsky argued that children would never acquire the tools needed for processing an infinite number of sentences if the language acquisition mechanism was dependent on language input alone.

Noam Chomsky introduced the nativist theory of language development, emphasizing the role of innate structures and mechanisms in the human brain. Key points of Chomsky’s theory include:

Language Acquisition Device (LAD): Chomsky proposed that humans have an inborn biological capacity for language, often termed the LAD, which predisposes them to acquire language.

Universal Grammar: He suggested that all human languages share a deep structure rooted in a set of grammatical rules and categories. This “universal grammar” is understood intuitively by all humans.

Poverty of the Stimulus: Chomsky argued that the linguistic input received by young children is often insufficient (or “impoverished”) for them to learn the complexities of their native language solely through imitation or reinforcement. Yet, children rapidly and consistently master their native language, pointing to inherent cognitive structures.

Critical Period: Chomsky, along with other linguists, posited a critical period for language acquisition, during which the brain is particularly receptive to linguistic input, making language learning more efficient.

Critics of Chomsky’s theory argue that it’s too innatist and doesn’t give enough weight to social interaction and other factors in language acquisition.

Universal Grammar

Consequently, he proposed the theory of Universal Grammar: an idea of innate, biological grammatical categories, such as a noun category and a verb category, that facilitate the entire language development in children and overall language processing in adults.

Universal Grammar contains all the grammatical information needed to combine these categories, e.g., nouns and verbs, into phrases. The child’s task is just to learn the words of her language (Ambridge & Lieven).

For example, according to the Universal Grammar account, children instinctively know how to combine a noun (e.g., a boy) and a verb (to eat) into a meaningful, correct phrase (A boy eats).

This Chomskian (1965) approach to language acquisition has inspired hundreds of scholars to investigate the nature of these assumed grammatical categories, and the research is still ongoing.

Contemporary Research

A decade or two later, some psycho-linguists began to question the existence of Universal Grammar. They argued that categories like nouns and verbs are biologically, evolutionarily, and psychologically implausible and that the field called for an account that can explain the acquisition process without innate categories.

Researchers started to suggest that instead of having a language-specific mechanism for language processing, children might utilize general cognitive and learning principles.

Whereas researchers approaching the language acquisition problem from the perspective of Universal Grammar argue for early full productivity, i.e., early adult-like knowledge of the language, the opposing constructivist investigators argue for a more gradual developmental process. It is suggested that children are sensitive to patterns in language which enables the acquisition process.

An example of this gradual pattern learning is morphology acquisition. Morphemes are the smallest grammatical markers, or units, in language that alter words. In English, regular plurals are marked with an –s morpheme (e.g., dog+s).

Similarly, English third singular verb forms (she eat+s, a boy kick+s) are marked with the –s morpheme. Children are considered to acquire their first instances of third singular forms as entire phrasal chunks (Daddy kicks, a girl eats, a dog barks) without the ability to tease the finest grammatical components apart.

When the child hears a sufficient number of instances of a linguistic construction (i.e., the third singular verb form), she will detect patterns across the utterances she has heard. In this case, the repeated pattern is the –s marker in this particular verb form.

As a result of many repetitions and examples of the –s marker in different verbs, the child will acquire sophisticated knowledge that, in English, verbs must be marked with an –s morpheme in the third singular form (Ambridge & Lieven, 2011; Pine, Conti-Ramsden, Joseph, Lieven & Serratrice, 2008; Theakson & Lieven, 2005).

Approaching language acquisition from the perspective of general cognitive processing is an economic account of how children can learn their first language without an excessive biolinguistic mechanism.

However, finding a solid answer to the problem of language acquisition is far from being over. Our current understanding of the developmental process is still immature.

Investigators of Universal Grammar are still trying to convince that language is a task too demanding to acquire without specific innate equipment, whereas constructivist researchers are fiercely arguing for the importance of linguistic input.

The biggest questions, however, are yet unanswered. What is the exact process that transforms the child’s utterances into grammatically correct, adult-like speech? How much does the child need to be exposed to language to achieve the adult-like state?

What account can explain variation between languages and the language acquisition process in children acquiring very different languages to English? The mystery of language acquisition is granted to keep psychologists and linguists alike astonished decade after decade.

What is language acquisition?

Language acquisition refers to the process by which individuals learn and develop their native or second language.

It involves the acquisition of grammar, vocabulary, and communication skills through exposure, interaction, and cognitive development. This process typically occurs in childhood but can continue throughout life.

What is Skinner’s theory of language development?

Skinner’s theory of language development, also known as behaviorist theory, suggests that language is acquired through operant conditioning. According to Skinner, children learn language by imitating and being reinforced for correct responses.

He argued that language is a result of external stimuli and reinforcement, emphasizing the role of the environment in shaping linguistic behavior.

What is Chomsky’s theory of language acquisition?

Chomsky’s theory of language acquisition, known as Universal Grammar, posits that language is an innate capacity of humans.

According to Chomsky, children are born with a language acquisition device (LAD), a biological ability that enables them to acquire language rules and structures effortlessly.

He argues that there are universal grammar principles that guide language development across cultures and languages, suggesting that language acquisition is driven by innate linguistic knowledge rather than solely by environmental factors.

Ambridge, B., & Lieven, E.V.M. (2011). Language Acquisition: Contrasting theoretical approaches . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the Theory of Syntax . MIT Press.

Pine, J.M., Conti-Ramsden, G., Joseph, K.L., Lieven, E.V.M., & Serratrice, L. (2008). Tense over time: testing the Agreement/Tense Omission Model as an account of the pattern of tense-marking provision in early child English. Journal of Child Language , 35(1): 55-75.

Rowland, C. F.; & Noble, C. L. (2010). The role of syntactic structure in children’s sentence comprehension: Evidence from the dative. Language Learning and Development , 7(1): 55-75.

Skinner, B.F. (1957). Verbal behavior . Acton, MA: Copley Publishing Group.

Theakston, A.L., & Lieven, E.V.M. (2005). The acquisition of auxiliaries BE and HAVE: an elicitation study. Journal of Child Language , 32(2): 587-616.

Further Reading

An excellent article by Steven Pinker on Language Acquisition

Pinker, S. (1995). The New Science of Language and Mind . Penguin.

Tomasello, M. (2005). Constructing A Language: A Usage-Based Theory of Language Acquisition . Harvard University Press.

- NAEYC Login

- Member Profile

- Hello Community

- Accreditation Portal

- Online Learning

- Online Store

Popular Searches: DAP ; Coping with COVID-19 ; E-books ; Anti-Bias Education ; Online Store

Language and Literacy Development: Research-Based, Teacher-Tested Strategies

You are here

“Why does it tick and why does it tock?”

“Why don’t we call it a granddaughter clock?”

“Why are there pointy things stuck to a rose?”

“Why are there hairs up inside of your nose?”

She started with Why? and then What? How? and When? By bedtime she came back to Why? once again. She drifted to sleep as her dazed parents smiled at the curious thoughts of their curious child, who wanted to know what the world was about. They kissed her and whispered, “You’ll figure it out.”

—Andrea Beaty, Ada Twist, Scientist

I have dozens of favorite children’s books, but while working on this cluster about language and literacy development, Ada Twist, Scientist kept coming to mind. Ada is an African American girl who depicts the very essence of what it means to be a scientist. The book is a celebration of children’s curiosity, wonder, and desire to learn.

The more I thought about language and literacy, the more Ada became my model. All children should have books as good as Ada Twist, Scientist read to them. All children should be able to read books like Ada Twist, Scientist by the end of third grade. All children should be encouraged to ask questions about their world and be supported in developing the literacy tools (along with broad knowledge, inquiring minds, and other tools!) to answer those questions. All children should see themselves in books that rejoice in learning.

Early childhood teachers play a key role as children develop literacy. While this cluster does not cover the basics of reading instruction, it offers classroom-tested ways to make common practices like read alouds and discussions even more effective.

The cluster begins with “ Enhancing Toddlers’ Communication Skills: Partnerships with Speech-Language Pathologists ,” by Janet L. Gooch. In a mutually beneficial partnership, interns from a university communication disorders program supported Early Head Start teachers in learning several effective ways to boost toddlers’ language development, such as modeling the use of new vocabulary and expanding on what toddlers say. (One quirk of Ada Twist, Scientist is that Ada doesn’t speak until she is 3; in real life, that would be cause for significant concern. Having a submission about early speech interventions was pure serendipity.) Focusing on preschoolers, Kathleen M. Horst, Lisa H. Stewart, and Susan True offer a framework for enhancing social, emotional, and academic learning. In “ Joyful Learning with Stories: Making the Most of Read Alouds ,” they explain how to establish emotionally supportive routines that are attentive to each child’s strengths and needs while also increasing group discussions. During three to five read alouds of a book, teachers engage children in building knowledge, vocabulary, phonological awareness, and concepts of print.

Next up, readers go inside the lab school at Stepping Stones Museum for Children. In “ Equalizing Opportunities to Learn: A Collaborative Approach to Language and Literacy Development in Preschool ,” Laura B. Raynolds, Margie B. Gillis, Cristina Matos, and Kate Delli Carpini share the engaging, challenging activities they designed with and for preschoolers growing up in an under-resourced community. Devondre finds out how hard Michelangelo had to work to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, and Sayo serves as a guide in the children’s classroom minimuseum— taking visitors to her artwork!

Moving into first grade, Laura Beth Kelly, Meridith K. Ogden, and Lindsey Moses explain how they helped children learn to lead and participate in meaningful discussions of literature. “ Collaborative Conversations: Speaking and Listening in the Primary Grades ” details the children’s progress (and the teacher’s methods) as they developed discussion-related social and academic skills. Although the first graders still required some teacher facilitation at the end of the school year, they made great strides in preparing for conversations, listening to their peers, extending others’ comments, asking questions, and reflecting on discussions.

Rounding out the cluster are two articles on different aspects of learning to read. In “ Sounding It Out Is Just the First Step: Supporting Young Readers ,” Sharon Ruth Gill briefly explains the complexity of the English language and suggests several ways teachers can support children as they learn to decode fluently. Her tips include giving children time to self-correct, helping them use semantic and syntactic cues, and analyzing children’s miscues to decide what to teach next.

In “ Climbing Fry’s Mountain: A Home–School Partnership for Learning Sight Words ,” Lynda M. Valerie and Kathleen A. Simoneau describe a fun program for families. With game-like activities that require only basic household items, children in kindergarten through second grade practice reading 300 sight words. Children feel successful as they begin reading, and teachers reserve instructional time for phonological awareness, phonics, vocabulary, and other essentials of early reading.

At the end of Ada Twist, Scientist , there is a marvelous illustration of Ada’s whole family reading. “They remade their world—now they’re all in the act / of helping young Ada sort fiction from fact.” It reminds me of the power of reading and of the important language and literacy work that early childhood educators do every day.

—Lisa Hansel

We’d love to hear from you!

Send your thoughts on this issue, as well as topics you’d like to read about in future issues of Young Children , to [email protected] .

Would you like to see your children’s artwork featured? For guidance on submitting print-quality photos (as well as details on permissions and licensing), see NAEYC.org/resources/pubs/authors-photographers/photos .

Is your classroom full of children’s artwork? To feature it in Young Children , see the link at the bottom of the page or email [email protected] for details.

Lisa Hansel, EdD, is the editor in chief of NAEYC's peer-reviewed journal, Young Children .

Vol. 74, No. 1

Print this article

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Affective Science

- Biological Foundations of Psychology

- Clinical Psychology: Disorders and Therapies

- Cognitive Psychology/Neuroscience

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational/School Psychology

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems of Psychology

- Individual Differences

- Methods and Approaches in Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational and Institutional Psychology

- Personality

- Psychology and Other Disciplines

- Social Psychology

- Sports Psychology

- Share Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Language acquisition.

- Erica H. Wojcik , Erica H. Wojcik Department of Psychology, Skidmore College

- Irene de la Cruz-Pavía Irene de la Cruz-Pavía Laboratoire Psychologie de la Perception, Universite Paris Descartes

- , and Janet F. Werker Janet F. Werker Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.56

- Published online: 26 April 2017

Language is a structured form of communication that is unique to humans. Within the first few years of life, typically developing children can understand and produce full sentences in their native language or languages. For centuries, philosophers, psychologists, and linguists have debated how we acquire language with such ease and speed. Central to this debate has been whether the learning process is driven by innate capacities or information in the environment. In the field of psychology, researchers have moved beyond this dichotomy to examine how perceptual and cognitive biases may guide input-driven learning and how these biases may change with experience. There is evidence that this integration permeates the learning and development of all aspects of language—from sounds (phonology), to the meanings of words (lexical-semantics), to the forms of words and the structure of sentences (morphosyntax). For example, in the area of phonology, newborns’ bias to attend to speech over other signals facilitates early learning of the prosodic and phonemic properties of their native language(s). In the area of lexical-semantics, infants’ bias to attend to novelty aids in mapping new words to their referents. In morphosyntax, infants’ sensitivity to vowels, repetition, and phrase edges guides statistical learning. In each of these areas, too, new biases come into play throughout development, as infants gain more knowledge about their native language(s).

- child development

- lexical-semantics

You do not currently have access to this article

Please login to access the full content.

Access to the full content requires a subscription

Printed from Oxford Research Encyclopedias, Psychology. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 07 November 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.126.86.119]

- 185.126.86.119

Character limit 500 /500

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 9: Language Development

Theories of Language Development

Psychological theories of language learning differ in terms of the importance they place on nature and nurture. Remember that we are a product of both nature and nurture. Researchers now believe that language acquisition is partially innate and partially learned through our interactions with our linguistic environment (Gleitman & Newport, 1995; Stork & Widdowson, 1974).

Video 9.3 Theories of Language Development discusses the major theories of how language develops in children.

Learning Theory

Perhaps the most straightforward explanation of language development is that it occurs through the principles of learning, including association and reinforcement (Skinner, 1953). Additionally, Bandura (1977) described the importance of observation and imitation of others in learning language. There must be at least some truth to the idea that language is learned through environmental interactions or nurture. Children learn the language that they hear spoken around them rather than some other language. Also supporting this idea is the gradual improvement of language skills with time. It seems that children modify their language through imitation and reinforcement, such as parental praise and being understood. For example, when a two-year-old child asks for juice, he might say, “me juice,” to which his mother might respond by giving him a cup of apple juice.

However, language cannot be entirely learned. For one, children learn words too fast for them to be learned through reinforcement. Between the ages of 18 months and 5 years, children learn up to 10 new words every day (Anglin, 1993). More importantly, language is more generative than it is imitative . Language is not a predefined set of ideas and sentences that we choose when we need them, but rather a system of rules and procedures that allows us to create an infinite number of statements, thoughts, and ideas, including those that have never previously occurred. When a child says that they “swimmed” in the pool, for instance, they are showing generativity. No adult speaker of English would ever say “swimmed,” yet it is easily generated from the normal system of producing language.

Other evidence that refutes the idea that all language is learned through experience comes from the observation that children may learn languages better than they ever hear them. Deaf children whose parents do not speak ASL very well nevertheless are able to learn it perfectly on their own, and may even make up their own language if they need to (Goldin-Meadow & Mylander, 1998). A group of deaf children in a school in Nicaragua, whose teachers could not sign, invented a way to communicate through made-up signs (Senghas, Senghas, & Pyers, 2005). The development of this new Nicaraguan Sign Language has continued and changed as new generations of students have come to the school and started using the language. Although the original system was not a real language, it is becoming closer and closer every year, showing the development of a new language in modern times.

The linguist Noam Chomsky is a believer in the nature approach to language, arguing that human brains contain a Language Acquisition Device that includes a universal grammar that underlies all human language (Chomsky, 1965, 1972). According to this approach, each of the many languages spoken around the world (there are between 6,000 and 8,000) is an individual example of the same underlying set of procedures that are hardwired into human brains. Chomsky’s account proposes that children are born with a knowledge of general rules of syntax that determine how sentences are constructed. Language develops as long as the infant is exposed to it. No teaching, training, or reinforcement is required for language to develop as proposed by Skinner.

Although there is general agreement among psychologists that babies are genetically programmed to learn language, there is still debate about Chomsky’s idea that there is a universal grammar that can account for all language learning. Evans and Levinson (2009) surveyed the world’s languages and found that none of the presumed underlying features of the language acquisition device were entirely universal. In their search they found languages that did not have noun or verb phrases, that did not have tenses (e.g., past, present, future), and even some that did not have nouns or verbs at all, even though a basic assumption of a universal grammar is that all languages should share these features.

Sensitive Periods

Anyone who has tried to master a second language as an adult knows the difficulty of language learning. Yet children learn languages easily and naturally. Children who are not exposed to language early in their lives will likely never learn one. Case studies, including Victor the “Wild Child,” who was abandoned as a baby in France and not discovered until he was 12, and Genie, a child whose parents kept her locked in a closet from 18 months until 13 years of age, are (fortunately) two of the only known examples of these deprived children. Both of these children made some progress in socialization after they were rescued, but neither of them ever developed complex language abilities (Rymer, 1993). This is also why it is important to determine quickly if a child is deaf, and to communicate in sign language immediately. Deaf children who are not exposed to sign language during their early years will likely never learn the complexity of language (Mayberry, Lock, & Kazmi, 2002). The concept of sensitive periods highlights the importance of both nature and nurture for language development.

Interactionist Approach

The interactionist approach (sociocultural theory) combines ideas from psychology and biology to explain how language is developed. According to this theory, children learn language out of a desire to communicate with the world around them. Language emerges from, and is dependent upon, social interaction. The interactionist approach claims that if our language ability develops out of a desire to communicate, then language is dependent upon whom we want to communicate with. This means the environment you grow up in will heavily affect how well and how quickly you learn to talk. For example, infants being raised by only their mother are more likely to learn the word “mama”, and less likely to develop “dada”. Among the first words we learn are ways to demand attention or food. If you’ve ever tried to learn a new language, you may recognize this theory’s influence. Language classes often teach commonly used vocabulary and phrases first, and then focus on building conversations rather than simple rote memorization. Even when we expand our vocabularies in our native language, we remember the words we use the most.

Social pragmatics

Language from the interactionist view is not only a cognitive skill but also a social one. Language is a tool humans use to communicate, connect to, influence, and inform others. Most of all, language comes out of a need to cooperate. The social nature of language has been demonstrated by a number of studies that have shown that children use several pre-linguistic skills (such as pointing and other gestures) to communicate not only their own needs but what others may need. So a child watching her mother search for an object may point to the object to help her mother find it.

Eighteen-month to 30-month-olds have been shown to make linguistic repairs when it is clear that another person does not understand them (Grosse, Behne, Carpenter & Tomasello, 2010). Grosse et al. (2010) found that even when the child was given the desired object, if there had been any misunderstanding along the way (such as a delay in being handed the object, or the experimenter calling the object by the wrong name), children would make linguistic repairs. This would suggest that children are using language not only as a means of achieving some material goal, but to make themselves understood in the mind of another person.

Vygotsky and Language Development

Lev Vygotsky hypothesized that children had a zone of proximal development (ZPD) . The ZPD is the range of material that a child is ready to learn if proper support and guidance are given from either a peer who understands the material or by an adult. We can see the benefit of this sort of guidance when we think about the acquisition of language. Children can be assisted in learning language by others who listen attentively, model more accurate pronunciations and encourage elaboration. For example, if the child exclaims, “I’m goed there!” then the adult responds, “You went there?” This specific type of assistance is called recasting .

Children may be hard-wired for language development, as Noam Chomsky suggested in his theory of universal grammar, but active participation is also important for language development. The process of scaffolding is one in which the guide provides needed assistance to the child as a new skill is learned. Repeating what a child has said, but in a grammatically correct way, is scaffolding for a child who is struggling with the rules of language production.

Private Speech

Do you ever talk to yourself? Why? Chances are, this occurs when you are struggling with a problem, trying to remember something or feel very emotional about a situation. Children talk to themselves too. Piaget interpreted this as egocentric speech or a practice engaged in because of a child’s inability to see things from other points of view. Vygotsky, however, believed that children talk to themselves in order to solve problems or clarify thoughts. As children learn to think in words, they do so aloud before eventually closing their lips and engaging in private speech or inner speech. Thinking out loud eventually becomes thought accompanied by internal speech, and talking to oneself becomes a practice only engaged in when we are trying to learn something or remember something, etc. Private speech is not as elaborate as the speech we use when communicating with others (Vygotsky, 1962).

combines ideas from psychology and biology to explain how language is developed

the range of material that a child is ready to learn if proper support and guidance are given from either a peer who understands the material or by an adult

a process in which adults or capable peers model or demonstrate how to solve a problem, and then step back, offering support as needed

thought accompanied by internal speech

Child and Adolescent Development Copyright © 2023 by Krisztina Jakobsen and Paige Fischer is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Energized – Engaged – Empowered

Language Development In Early Childhood: A Parent’s Guide

Table of Contents

What is Language Development in Early Childhood Development?

Stages of language development in early childhood, what affects language development in early childhood, be a role model, follow their interests, establish a language-rich environment, read to them, ishcmc’s commitment to language development in early childhood.

Language development contributes significantly to a child’s development journey when encouraging them to understand, communicate, and express their feelings. Knowing how linguistics develops can aid parents in creating an atmosphere that encourages their child’s ability to use language. This guidance takes a closer look at the process, the factors, and strategies for children to develop language.

Language development in early childhood is a well-described process where children, within the early stages of birth to the early adolescent period, gradually learn to comprehend and use language. It ranges from understanding the words, their meanings, grammar, and usage in appropriate contexts to achieving effective communication. Exposure to language and conversation at the earliest years of life is core to developing essential skills for the child to communicate thoughts and feelings.

Language development occurs in successive stages: mere recognition of the sound and then responding to voices of familiar persons; later on, babies babble, imitate words, and construct simple sentences. These stages can be divided as follows:

- Pre-linguistic stage (0-12 months): In this phase, the infant plays with the sounds and connects meaning to gestures and vocal cues.

- Single-word stage (12-18 months): Babies start using single words to convey meaning, such as “mama” or “ball.”

- Two-word stage (18 months-2 years): Children combine words to express more complex ideas like “want milk.”

- Multi-word stage (2-3 years): Vocabulary expands rapidly, and children form short sentences to communicate their needs and thoughts.

- Complex Sentences (3-4 years): At this stage, children begin to understand grammar rules and can form more detailed sentences, often incorporating descriptive words. They start asking many “why” and “how” questions.

- Narrative Development (4-5 years): Children can tell simple stories and describe events in sequence. Their vocabulary grows significantly, and they begin using more complex sentence structures to express ideas clearly.

Several factors influence how and when children develop language skills. Below are some key elements:

- Age: Younger children typically learn language faster, with rapid vocabulary growth in the first few years.

- Home Environment: A language-rich environment fosters language development by allowing caregivers to engage in conversation and provide diverse vocabulary.

- Social and Cultural Influences: Children exposed to various languages and cultural contexts develop unique language skills, impacting their communication style.

- Cognitive Factors: The influence of cognitive development determines how a child will learn and apply the language.

- Learning Environment: Quality early childhood education programs can offer planned opportunities for language interaction and learning.

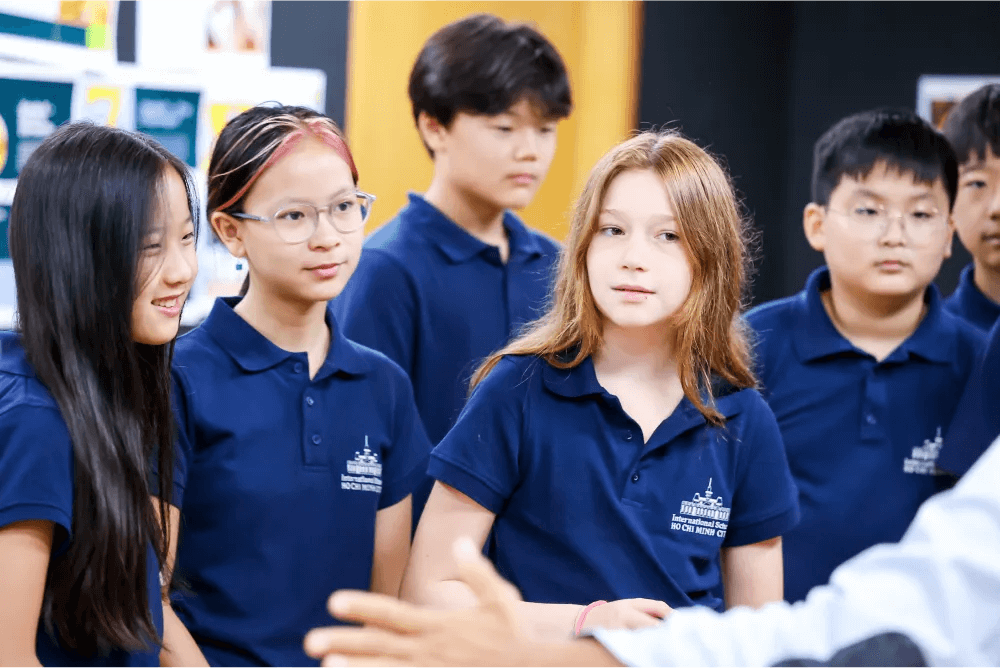

At ISHCMC, language development is cultivated through a range of activities that promote interaction and investigation. The School focuses on a multicultural environment where children learn multiple languages and explore various cultural standpoints. This holistic approach develops the linguistic abilities in children while instilling a love of learning.

How to Support Language Development In Early Childhood

Supporting your child’s language development involves intentional engagement and interaction. Here are effective strategies:

Children learn a lot from what they see and then intend to mimic the adults. Therefore, parents and caregivers should also model clear and articulate speech themselves, using diverse vocabulary and an expressively toned conversation. Show your child the freedom to talk by listening and responding to them to enhance their self-esteem in the use of language.

Talking to your child about what they like can help you improve their vocabulary. If your children are animal lovers, talk about the different species, their habitats, and behaviors. This makes learning enjoyable and encourages children to ask many questions, helping them acquire new words related to their interests.

Create a language-rich house by having books and labels all over the house read to the children. Play educational games and have educational toys, story cards, and rhyming games. Choose a time for the family to sit together, such as during supper, where everyone shares how their day went. Regularly engaging your child in these kinds of conversations will contribute to the development of their language skills.

One of the best ways to encourage language use is through reading. Reading introduces children to new words, sentence structures, and new concepts. Make reading a daily activity and allow children to choose the books they want. Engage them interactively by asking about the events in the story and encouraging them to predict what happens next. Observing the illustrations and discussing the emotions displayed by the characters helps develop their understanding and builds a habit of reading.

Language-based games can make learning fun and educational. “I Spy” is a great example that can enhance vocabulary and observation skills. Storytelling games encourage creativity and help children learn to structure their thoughts. Use puppets or dolls to create stories, allowing your child to participate in the narrative. These playful interactions make learning engaging and help enjoyably solidify their language skills.

Language development is a vital part of early childhood, influenced by many factors such as environment and social interactions. Parents play a crucial role in this journey by creating a supportive, language-rich environment.

At ISHCMC, we nurture the language development of children through our English as an Additional Language (EAL) program . This program will access students’ English level to provide them with relevant support and resources, enhancing their social and academic skills. To learn more about how ISHCMC can help your child excel in language development, visit our admissions page.

More articles

Why Choose IB Schools in Vietnam for Your Child’s Education?

What is Intercultural Communication? Benefits and Importance

A Level or IB ? Key Differences and How to Decide

IB Certificate vs IB Diploma: Key Differences & Choosing Guides

Theories of Language Development

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2021

- pp 4816–4821

- Cite this reference work entry

- Inge-Marie Eigsti 2

66 Accesses

Language acquisition presents children with a tremendous challenge: how to determine the mappings between meanings in their world, and the complex acoustic signal of speech. Children must segment the running stream of sounds that they hear into words and phrases, and determine the regularities, or systematicities, of the language. Furthermore, they accomplish this task in the absence of direct instruction and even (for example, in the case of Quiche Mayan) while hearing little language directed at themselves (Pye 1986 ). As such, the acquisition of human language has been described as the single most impressive intellectual accomplishment of individual humans (Pinker 1984 ).

There are five systematic features of language that a learner must master in order to understand and produce a spoken or signed language. Note that while this review focuses on spoken languages, there is such significant overlap with signed languages; see the “American Sign Language (ASL)” entry for more...

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

References and Reading

Brynskov, C., Eigsti, I. M., Jørgensen, M., Lemcke, S., Bohn, O.-S., & Krøjgaard, P. (2017). Syntax and morphology in Danish-speaking children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47 (2), 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2962-7 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Candland, D. K. (1993). Feral children and clever animals: Reflections on human nature . New York: Oxford University Press.

Google Scholar

Chomsky, N. (1959). Review of skinner’s ‘verbal behavior’. Language, 35 , 26–58.

Chomsky, N. (1986). Knowledge of language: Its nature, origin, and use . New York: Praeger.

Cicchetti, D., & Rogosch, F. (1996). Developmental pathways: Diversity in process and outcome. Development and Psychopathology, 8 (4), 597–896.

Curtiss, S., Katz, W., & Tallal, P. (1992). Delay versus deviance in the language acquisition of language-impaired children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 35 (2), 373–383.

de Marchena, A., Eigsti, I. M., Worek, A., Ono, K. E., & Snedeker, J. (2011). Mutual exclusivity in autism spectrum disorders: Testing the pragmatic hypothesis. Cognition, 119 , 96–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2010.12.011 .

Elman, J. L., Bates, E. A., Johnson, M. H., Karmiloff-Smith, A., Parisi, D., & Plunkett, K. (1996). Rethinking innateness: A connectionist perspective on development . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Fodor, J. A. (1983). The modularity of mind . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Fromkin, V., Krashen, S., Curtiss, S., Rigler, D., & Rigler, M. (1974). The development of language in Genie: A case of language acquisition beyond the “critical period”. Brain and Language, 1 (1), 81–107.

Markman, E. M. (1990). Constraints children place on word meanings. Cognitive Science, 14 , 57–77.

McClelland, J. L. (2000). The basis of hyperspecificity in autism: A preliminary suggestion based on properties of neural nets. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30 (5), 497–502.

PubMed Google Scholar

McNeill, D. (1970). The acquisition of language: The study of developmental psycholinguistics . New York: Harper & Row.

Oller, D. K., Niyogi, P., Gray, S., Richards, J. A., Gilkerson, J., Xu, D., et al. (2010). Automated vocal analysis of naturalistic recordings from children with autism, language delay, and typical development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107 (30), 13354–13359. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1003882107 .

Article Google Scholar

Pinker, S. (1984). Language learnability and language development . Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Plunkett, K. (1997). Theories of early language acquisition. Trends Cognition Sciences, 1 (4), 146–153. https://doi.org/110.1016/S1364-6613(1097)01039-01035 .

Pye, C. (1986). Quiche Mayan speech to children. Journal of Child Language, 13 , 85–100.

Quine, W. V. (1960). Word and object . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Saffran, J. R., Aslin, R. N., & Newport, E. L. (1996). Statistical learning by 8-month-old infants. Science, 274 , 1926–1928.

Saffran, J. R., Pollak, S. D., Seibel, R. L., & Shkolnik, A. (2007). Dog is a dog is a dog: Infant rule learning is not specific to language. Cognition, 105 (3), 669–680. Epub 2006 Dec 2026.

Schuh, J. M., Eigsti, I. M., & Mirman, D. (2016). Referential communication in autism spectrum disorder: The roles of working memory and theory of mind. Autism Research . https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1632 .

Tek, S., Jaffery, G., Fein, D., & Naigles, L. R. (2008). Do children with autism spectrum disorders show a shape bias in word learning? Autism Research, 1 (4), 208–222. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.38 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tomasello, M. (2000). The item-based nature of children’s early syntactic development. Trends Cognition Sciences, 4 (4), 156–163.

Warlaumont, A. S., Richards, J. A., Gilkerson, J., & Oller, D. K. (2014). A social feedback loop for speech development and its reduction in autism. Psychological Science, 25 (7), 1314–1324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614531023 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychological Sciences, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT, USA

Inge-Marie Eigsti

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Inge-Marie Eigsti .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA

Fred R. Volkmar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Eigsti, IM. (2021). Theories of Language Development. In: Volkmar, F.R. (eds) Encyclopedia of Autism Spectrum Disorders. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91280-6_543

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91280-6_543

Published : 14 March 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-91279-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-91280-6

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Business, Economics and Social Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Language Development Essay Introduction. Language development refers to the process of deliberate communication using sounds, gestures, or symbols which can be understood by other people (Machado, 1985). Language is double perspectives process which forms the basis for other forms of learning.

In summary, language occurs through an interaction among genes (which hold innate tendencies to communicate and be sociable), environment, and the child's own thinking abilities. When children develop abilities is always a difficult question to answer. In general…. Children say their first words between 12 and 18 months of age.

March, 2024 Dr.Mahfoudh. 2. Abstract: Language development in children is a multifaceted process influenced by various factors, including biological predispositions, environmental influences, and ...

development [1]. Thus, the study of language development, for the most part, can be compared to that of the physical organ and this has become apparent after the Chomskian revolution. Noam Chomsky concluded that there is a language acquisition device in the human brain, an organ that grows and develops and matures

During early childhood, children's abilities to understand, to process, and to produce language also flourish in an amazing way. Young children experience a language explosion between the ages of 3 and 6. At age 3, their spoken vocabularies consist of roughly 900 words. By age 6, spoken vocabularies expand dramatically to anywhere between ...

Child development and learning focusing on language development This essay is about a child's development and learning, focusing primarily on language development. It will describe the main stages of developmental "milestones" and the key concepts involved for children to develop their language skills, discussing language acquisition and ...

In the following chapter, the basic milestones of early language development are reviewed.Language acquisition in early years of childhood 5 Language acquisition during the first years of life (0 to 3 years) Responsive relationships and language-rich environment during early childhood create a basis for language acquisition and cognitive ...

Language acquisition refers to the process by which individuals learn and develop their native or second language. It involves the acquisition of grammar, vocabulary, and communication skills through exposure, interaction, and cognitive development. This process typically occurs in childhood but can continue throughout life.

This essay will explore Piaget's Theory of Language Development, examining its key aspects and implications for understanding how children acquire language. By analyzing the stages of language development proposed by Piaget, we can gain valuable insights into the processes that underlie language acquisition and their significance for children's ...

%PDF-1.7 %âãÏÓ 26 0 obj > endobj 44 0 obj >/Filter/FlateDecode/ID[0D4D4F7E231D8B479880931EBF2675F5>]/Index[26 35]/Info 25 0 R/Length 93/Prev 113622/Root 27 0 R ...

Acquisition of a child's first language begins at birth and conti nues to puberty (the 'critical period'). Spada and Lightbo wn [6]; DeKe yser and Larson -Hall [2] noted that d uring the ...

Language Development. Figure 1. Reading to young children helps them develop language skills by hearing and using new vocabulary words. A child's vocabulary expands between the ages of two to six from about 200 words to over 10,000 words through a process called fast-mapping.

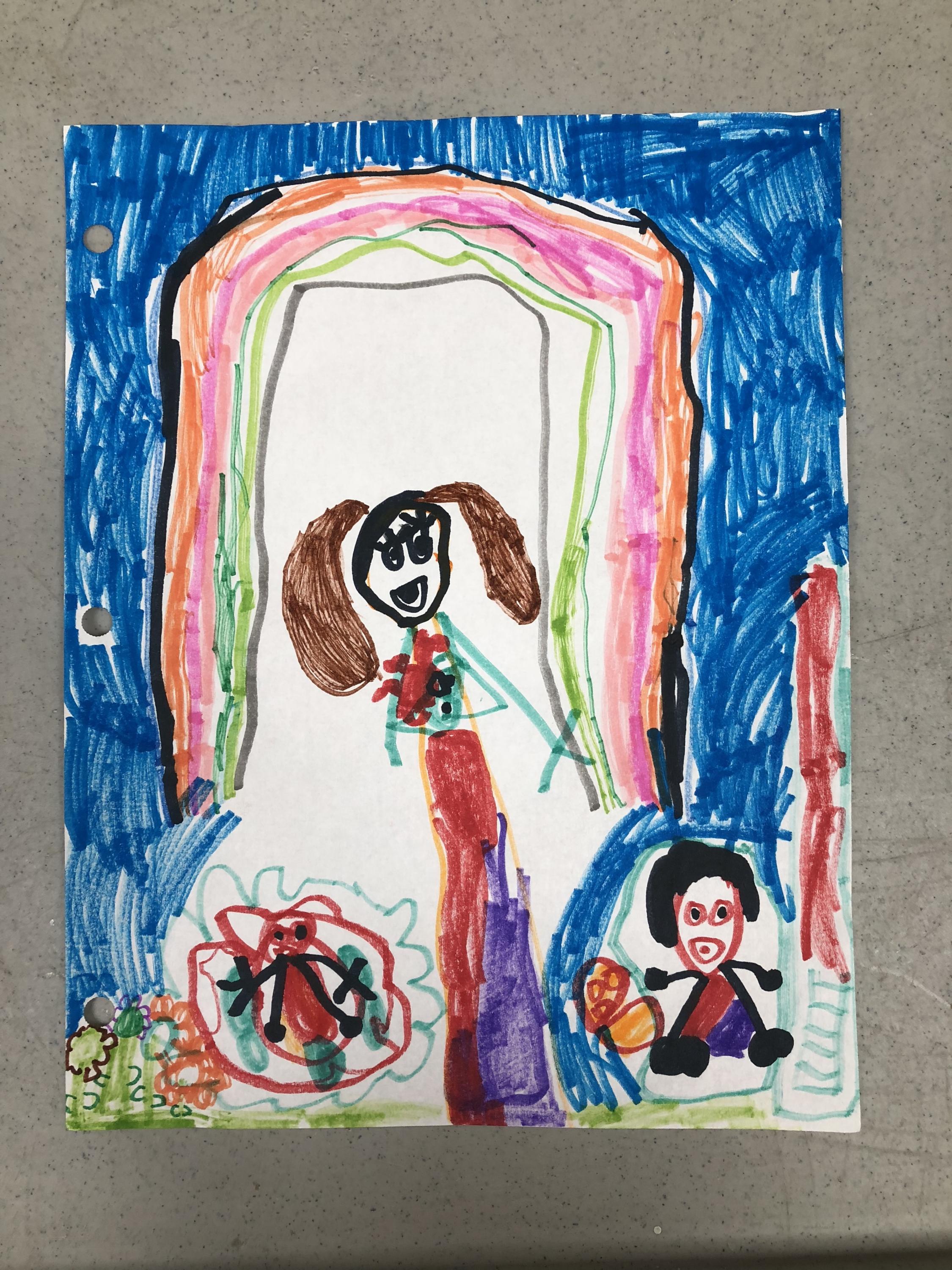

Advertisement. Early childhood teachers play a key role as children develop literacy. While this cluster does not cover the basics of reading instruction, it offers classroom-tested ways to make common practices like read alouds and discussions even more effective. This drawing is by a 4-year-old at Bet Yeladim Preschool in Columbia, MD,

A strong foundation in language skills is associated with positive, long-term academic, occupational, and social outcomes. Individual differences in the rate of language development appear early. Approximately 16% of children experience delays in initial phases of language learning; approximately half of those show persistent difficulties that may lead to clinical disorders.1 Because of the ...

About this book. Perspectives on Language and Language Development brings together new perspectives on language, discourse and language development in 31 chapters by leading scholars from several countries with diverging backgrounds and disciplines. It is a comprehensive overview of language as a rich, multifaceted system, inspired by the ...

Developmental Science, 1-17. Language is a structured form of communication that is unique to humans. Within the first few years of life, typically developing children can understand and produce full sentences in their native language or languages. For centuries, philosophers, psychologists, and linguists have debated how we acquire language ...

Definition. Language development is the process by which children come to understand and produce language to communicate with others, and entails the different components of phonology (sounds of a language), semantics (word meanings), grammar (rules on combining words into sentences), and pragmatics (the norms around communication).

Nativism. The linguist Noam Chomsky is a believer in the nature approach to language, arguing that human brains contain a Language Acquisition Device that includes a universal grammar that underlies all human language (Chomsky, 1965, 1972).According to this approach, each of the many languages spoken around the world (there are between 6,000 and 8,000) is an individual example of the same ...

Language development in early childhood is a well-described process where children, within the early stages of birth to the early adolescent period, gradually learn to comprehend and use language. It ranges from understanding the words, their meanings, grammar, and usage in appropriate contexts to achieving effective communication.

The acquisition of a language's vocabulary, or lexicon, is a challenging proposition; some languages convey concepts that, in other languages, are unspecified (for example, the concepts melancholy and gloomy are conveyed by a single term in many other languages). Typically developing children produce first words by around 10-11 months.

Young children learn to communicate in the language(s) of their communities, yet the individual trajectories of language development and the particular language varieties and modes of communication children acquire vary depending on the contexts in which they live. This review describes how context shapes language development. Building on the bioecological model of development, we ...