Sample of a Short Essay on Electronic Gadgets

Using electronic devices in the classroom is often underestimated. They can bring a lot of benefits if students and professors use them only for studying purposes. Otherwise, if students use their smartphones and laptops only for entertainment, this misuse significantly distracts them from the learning process and makes their devices uselessm, unless they look for “ write my essay for me cheap ” help.

WritingCheap cheap essay writing service proposes students to read our sample short essay on electronic gadgets. After getting acquainted with this subject, you can understand the methods of using electronic devices in the classroom and how to write a perfect essay by yourself. Impress your teacher with your knowledge of the advantages and disadvantages of electronic gadgets in class.

Effects of Electronic Devices on Education Electronic devices include integrated circuits controlled by the electric current; they are mainly used for processing, transfer, and control systems. Education, on the other hand, involves the process of gaining knowledge through an interactive process. Electronic devices affect education positively and negatively; the positive influence concerns enhancing education, and the negative influences affect the entire learning process. Positive Effects Electronic devices enhance education by making the learning resources easily assessable. By using a computer, students can access education information through the Internet. Additionally, there are technology-related projects that help the student be creative, innovative, and inventive (Eggers, 16). It also improves the teacher-student communication; these devices make a classroom a network system where there is a transfer of information from teacher to student and among students. Moreover, they directly help teachers in educating by bringing out the real picture in the process of giving information. For example, documentaries show the practical experience of events in history. Negative Effects The negative effects include making students spend the most time on devices, time that could otherwise be used for studying. Additionally, the information given tends to diminish the necessity of education. Some devices, such as mobile phones, also affect the learning process through interruptions from calls and text messages. Moreover, there is too much information available on electronic devices, and some of it is wrong. Hence, they tend to misguide students (Chen & Yun 6). Finally, these devices also create an opportunity for cheating among students. Conclusion In conclusion, electronic devices positively affect the communication process by making it easier for both the student and the teacher. However, if they are not contained, they change the process negatively. Therefore, there is a need to establish the best approach to ensure that devices have a positive effect, for example, through creating rules about the use of these devices in a classroom. Works Cited Chen, Shengjian, and Yun Lu. “The Negative Effects and Control of Blended Learning in the University.” 2013 the International Conference on Education Technology and Information System (ICETIS 2013) . Atlantis Press, 2013. Eggers, William D. Government 2.0: Using Technology to Improve Education, Cut Red Tape, Reduce Gridlock, and Enhance Democracy. Rowman & Littlefield, 2017.

~ out of 10 - average quality score

~ writers active

The impact of smartphone use on learning effectiveness: A case study of primary school students

- Published: 11 November 2022

- Volume 28 , pages 6287–6320, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Jen Chun Wang 1 ,

- Chia-Yen Hsieh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5476-2674 2 &

- Shih-Hao Kung 1

83k Accesses

4 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

This study investigated the effects of smartphone use on the perceived academic performance of elementary school students. Following the derivation of four hypotheses from the literature, descriptive analysis, t testing, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), Pearson correlation analysis, and one-way multivariate ANOVA (MANOVA) were performed to characterize the relationship between smartphone behavior and academic performance with regard to learning effectiveness. All coefficients were positive and significant, supporting all four hypotheses. We also used structural equation modeling (SEM) to determine whether smartphone behavior is a mediator of academic performance. The MANOVA results revealed that the students in the high smartphone use group academically outperformed those in the low smartphone use group. The results indicate that smartphone use constitutes a potential inequality in learning opportunities among elementary school students. Finally, in a discussion of whether smartphone behavior is a mediator of academic performance, it is proved that smartphone behavior is the mediating variable impacting academic performance. Fewer smartphone access opportunities may adversely affect learning effectiveness and academic performance. Elementary school teachers must be aware of this issue, especially during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The findings serve as a reference for policymakers and educators on how smartphone use in learning activities affects academic performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Smartphone Usage, Social Media Engagement, and Academic Performance: Mediating Effect of Digital Learning

Learning Hard or Hardly Learning: Smartphones in the University’s Classrooms

Relationships between adolescent smartphone usage patterns, achievement goals, and academic achievement

Meehyun Yoon & Heoncheol Yun

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The advent of the Fourth Industrial Revolution has stimulated interest in educational reforms for the integration of information and communication technology (ICT) into instruction. Smartphones have become immensely popular ICT devices. In 2019, approximately 96.8% of the global population had access to mobile devices with the coverage rate reaching 100% in various developed countries (Sarker et al., 2019 ). Given their versatile functions, smartphones have been rapidly integrated into communication and learning, among other domains, and have become an inseparable part of daily life for many. Smartphones are perceived as convenient, easy-to-use tools that promote interaction and multitasking and facilitate both formal and informal learning (Looi et al., 2016 ; Yi et al., 2016 ). Studies have investigated the impacts of smartphones in education. For example, Anshari et al. ( 2017 ) asserted that the advantages of smartphones in educational contexts include rich content transferability and the facilitation of knowledge sharing and dynamic learning. Modern students expect to experience multiple interactive channels in their studies. These authors also suggested incorporating smartphones into the learning process as a means of addressing inappropriate use of smartphones in class (Anshari et al., 2017 ). For young children, there are differences in demand and attributes and some need for control depending upon the daily smartphone usage of the children (Cho & Lee, 2017 ). To avoid negative impacts, including interference with the learning process, teachers should establish appropriate rules and regulations. In a study by Bluestein and Kim ( 2017 ) on the use of technology in the classroom they examined three themes: acceptance of tablet technology, learning excitement and engagement, and the effects of teacher preparedness and technological proficiency. They suggested that teachers be trained in application selection and appropriate in-class device usage. Cheng et al. ( 2016 ) found that smartphone use facilitated English learning in university students. Some studies have provided empirical evidence of the positive effects of smartphone use, whereas others have questioned the integration of smartphone use into the academic environment. For example, Hawi and Samaha ( 2016 ) investigated whether high academic performance was possible for students at high risk of smartphone addiction. They provided strong evidence of the adverse effects of smartphone addiction on academic performance. Lee et al. ( 2015 ) found a negative correlation between smartphone addiction and learning in university students. There has been a lot of research on the effectiveness of online teaching, but the results are not consistent. Therefore, this study aims to further explore the effects of independent variables on smartphone use behavior and academic performance.

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused many countries to close schools and suspend in-person classes, enforcing the transition to online learning. Carrillo and Flores ( 2020 ) suggested that because of widespread school closures, teachers must learn to manage the online learning environment. Online courses have distinct impacts on students and their families, requiring adequate technological literacy and the formulation of new teaching or learning strategies (Sepulveda-Escobar & Morrison, 2020 ). Since 2020, numerous studies have been conducted on parents’ views regarding the relationship of online learning, using smartphones, computers, and other mobile devices, with learning effectiveness. Widely inconsistent findings have been reported. For instance, in a study by Hadad et al. ( 2020 ), two thirds of parents were opposed to the use of smartphones in school, with more than half expressing active opposition ( n = 220). By contrast, parents in a study by Garbe et al. ( 2020 ) agreed to the school closure policy and allowed their children to use smartphones to attend online school. Given the differences in the results, further scholarly discourse on smartphone use in online learning is essential.

Questions remain on whether embracing smartphones in learning systems facilitates or undermines learning (i.e., through distraction). Only a few studies have been conducted on the impacts of smartphone use on academic performance in elementary school students (mostly investigating college or high school students). Thus, we investigated the effects of elementary school students’ smartphone use on their academic performance.

2 Literature review

Mobile technologies have driven a paradigm shift in learning; learning activities can now be performed anytime, anywhere, as long as the opportunity to obtain information is available (Martin & Ertzberger, 2013 ).

Kim et al. ( 2014 ) focused on identifying factors that influence smartphone adoption or use. Grant and Hsu ( 2014 ) centered their investigation on user behavior, examining the role of smartphones as learning devices and social interaction tools. Although the contribution of smartphones to learning is evident, few studies have focused on the connection between smartphones and learning, especially in elementary school students. The relationship between factors related to learning with smartphones among this student population is examined in the following sections.

2.1 Behavioral intentions of elementary school students toward smartphone use

Children experience rapid growth and development during elementary school and cultivate various aspects of the human experience, including social skills formed through positive peer interactions. All these experiences exert a substantial impact on the establishment of self-esteem and a positive view of self. Furthermore, students tend to maintain social relationships by interacting with others through various synchronous or asynchronous technologies, including smartphone use (Guo et al., 2011 ). Moreover, students favor communication through instant messaging, in which responses are delivered rapidly. However, for this type of interaction, students must acquire knowledge and develop skills related to smartphones or related technologies which has an impact on social relationships (Kang & Jung, 2014 ; Park & Lee, 2012 ).

Karikoski and Soikkeli ( 2013 ) averred that smartphone use promotes human-to-human interaction both through verbal conversation and through the transmission of textual and graphic information, and cn stimulate the creation and reinforcement of social networks. Park and Lee ( 2012 ) examined the relationship between smartphone use and motivation, social relationships, and mental health. The found smartphone use to be positively correlated with social intimacy. Regarding evidence supporting smartphone use in learning, Firmansyah et al. ( 2020 ) concluded that smartphones significantly benefit student-centered learning, and they can be used in various disciplines and at all stages of education. They also noted the existence of a myriad smartphone applications to fulfill various learning needs. Clayton and Murphy ( 2016 ) suggested that smartphones be used as a mainstay in classroom teaching, and that rather than allowing them to distract from learning, educators should help their students to understand how smartphones can aid learning and facilitate civic participation. In other words, when used properly, smartphones have some features that can lead to better educational performance. For example, their mobility can allow students access to the same (internet-based) services as computers, anytime, anywhere (Lepp et al., 2014 ). Easy accessibility to these functionalities offers students the chance to continuously search for study-related information. Thus, smartphones can provide a multi-media platform to facilitate learning which cannot be replaced by simply reading a textbook (Zhang et al., 2014 ). Furthermore, social networking sites and communication applications may also contribute to the sharing of relevant information. Faster communication between students and between students and faculty may also contribute to more efficient studying and collaboration (Chen et al., 2015 ). College students are more likely to have access to smartphones than elementary school students. The surge in smartphone ownership among college students has spurred interest in studying the impact of smartphone use on all aspects of their lives, especially academic performance. For example, Junco and Cotton ( 2012 ) found that spending a fair amount of time on smartphones while studying had a negative affect on the university student's Grade Point Average (GPA). In addition, multiple studies have found that mobile phone use is inversely related to academic performance (Judd, 2014 ; Karpinski et al., 2013 ). Most research on smartphone use and academic performance has focused on college students. There have few studies focused on elementary school students. Vanderloo ( 2014 ) argued that the excessive use of smartphones may cause numerous problems for the growth and development of children, including increased sedentary time and reduced physical activity. Furthermore, according to Sarwar and Soomro ( 2013 ), rapid and easy access to information and its transmission may hinder concentration and discourage critical thinking and is therefore not conducive to children’s cognitive development.

To sum up, the evidence on the use of smartphones by elementary school students is conflicting. Some studies have demonstrated that smartphone use can help elementary school students build social relationships and maintain their mental health, and have presented findings supporting elementary students’ use of smartphones in their studies. Others have opposed smartphone use in this student population, contending that it can impede growth and development. To take steps towards resolving this conflict, we investigated smartphone use among elementary school students.

In a study conducted in South Korea, Kim ( 2017 ) reported that 50% of their questionnaire respondents reported using smartphones for the first time between grades 4 and 6. Overall, 61.3% of adolescents reported that they had first used smartphones when they were in elementary school. Wang et al. ( 2017 ) obtained similar results in an investigation conducted in Taiwan. However, elementary school students are less likely to have access to smartphones than college students. Some elementary schools in Taiwan prohibit their students from using smartphones in the classroom (although they can use them after school). On the basis of these findings, the present study focused on fifth and sixth graders.

Jeong et al. ( 2016 ), based on a sample of 944 respondents recruited from 20 elementary schools, found that people who use smartphones for accessing Social Network Services (SNS), playing games, and for entertainment were more likely to be addicted to smartphones. Park ( 2020 ) found that games were the most commonly used type of mobile application among participants, comprised of 595 elementary school students. Greater smartphone dependence was associated with greater use of educational applications, videos, and television programs (Park, 2020 ). Three studies in Taiwan showed the same results, that elementary school students in Taiwan enjoy playing games on smartphones (Wang & Cheng, 2019 ; Wang et al., 2017 ). Based on the above, it is reasonable to infer that if elementary school students spend more time playing games on their smartphones, their academic performance will decline. However, several studies have found that using smartphones to help with learning can effectively improve academic performance. In this study we make effort to determine what the key influential factors that affect students' academic performance are.

Kim ( 2017 ) reported that, in Korea, smartphones are used most frequentlyfrom 9 pm to 12 am, which closely overlaps the corresponding period in Taiwan, from 8 to 11 pm In this study, we not only asked students how they obtained their smartphones, but when they most frequently used their smartphones, and who they contacted most frequently on their smartphones were, among other questions. There were a total of eight questions addressing smartphone behavior. Recent research on smartphones and academic performance draws on self-reported survey data on hours and/or minutes of daily use (e.g. Chen et al., 2015 ; Heo & Lee, 2021 ; Lepp et al., 2014 ; Troll et al., 2021 ). Therefore, this study also uses self-reporting to investigate how much time students spend using smartphones.

Various studies have indicated that parental attitudes affect elementary school students’ behavioral intentions toward smartphone use (Chen et al., 2020 ; Daems et al., 2019 ). Bae ( 2015 ) determined that a democratic parenting style (characterized by warmth, supervision, and rational explanation) was related to a lower likelihood of smartphone addiction in children. Park ( 2020 ) suggested that parents should closely monitor their children’s smartphone use patterns and provide consistent discipline to ensure appropriate smartphone use. In a study conducted in Taiwan, Chang et al. ( 2019 ) indicated that restrictive parental mediation reduced the risk of smartphone addiction among children. In essence, parental attitudes critically influence the behavioral intention of elementary school students toward smartphone use. The effect of parental control on smartphone use is also investigated in this study.

Another important question related to student smartphone use is self-control. Jeong et al. ( 2016 ) found that those who have lower self-control and greater stress were more likely to be addicted to smartphones. Self-control is here defined as the ability to control oneself in the absence of any external force, trying to observe appropriate behavior without seeking immediate gratification and thinking about the future (Lee et al., 2015 ). Those with greater self-control focus on long-term results when making decisions. People are able to control their behavior through the conscious revision of automatic actions which is an important factor in retaining self-control in the mobile and on-line environments. Self-control plays an important role in smartphone addiction and the prevention thereof. Previous studies have revealed that the lower one’s self-control, the higher the degree of smartphone dependency (Jeong et al., 2016 ; Lee et al., 2013 ). In other words, those with higher levels of self-control are likely to have lower levels of smartphone addiction. Clearly, self-control is an important factor affecting smartphone usage behavior.

Reviewing the literature related to self-control, we start with self-determination theory (SDT). The SDT (Deci & Ryan, 2008 ) theory of human motivation distinguishes between autonomous and controlled types of behavior. Ryan and Deci ( 2000 ) suggested that some users engage in smartphone communications in response to perceived social pressures, meaning their behavior is externally motivated. However, they may also be intrinsically motivated in the sense that they voluntarily use their smartphones because they feel that mobile communication meets their needs (Reinecke et al., 2017 ). The most autonomous form of motivation is referred to as intrinsic motivation. Being intrinsically motivated means engaging in an activity for its own sake, because it appears interesting and enjoyable (Ryan & Deci, 2000 ). Acting due to social pressure represents an externally regulated behavior, which SDT classifies as the most controlled form of motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2000 ). Individuals engage in such behavior not for the sake of the behavior itself, but to achieve a separable outcome, for example, to avoid punishment or to be accepted and liked by others (Ryan & Deci, 2006 ). SDT presumes that controlled and autonomous motivations are not complementary, but “work against each other” (Deci et al., 1999 , p. 628). According to the theory, external rewards alter the perceived cause of action: Individuals no longer voluntarily engage in an activity because it meets their needs, but because they feel controlled (Deci et al., 1999 ). For media users, the temptation to communicate through the smartphone is often irresistible (Meier, 2017 ). Researchers who have examined the reasons why users have difficulty controlling media use have focused on their desire to experience need gratification, which produces pleasurable experiences. The assumption here is that users often subconsciously prefer short-term pleasure gains from media use to the pursuit of long-term goals (Du et al., 2018 ). Accordingly, self-control is very important. Self-control here refers to the motivation and ability to resist temptations (Hofmann et al., 2009 ). Dispositional self-control is a key moderator of yielding to temptation (Hofmann et al., 2009 ). Ryan and Deci ( 2006 ) suggested that people sometimes perform externally controlled behaviors unconsciously, that is, without applying self-control.

Sklar et al. ( 2017 ) described two types of self-control processes: proactive and reactive. They suggested that deficiencies in the resources needed to inhibit temptation impulses lead to failure of self-control. Even when impossible to avoid a temptation entirely, self-control can still be made easier if one avoids attending to the tempting stimulus. For example, young children instructed to actively avoid paying attention to a gift and other attention-drawing temptations are better able to resist the temptation than children who are just asked to focus on their task. Therefore, this study more closely investigates students' self-control abilities in relation to smartphone use asking the questions, ‘How did you obtain your smartphone?’ (to investigate proactivity), and ‘How much time do you spend on your smartphone in a day?’ (to investigate the effects of self-control).

Thus, the following hypotheses are advanced.

Hypothesis 1: Smartphone behavior varies with parental control.

Hypothesis 2: Smartphone behavior varies based on students' self-control.

2.2 Parental control, students' self-control and their effects on learning effectiveness and academic performance

Based on Hypothesis 1 and 2, we believe that we need to focus on two factors, parental control and student self-control and their impact on academic achievement. In East Asia, Confucianism is one of the most prevalent and influential cultural values which affect parent–child relations and parenting practice (Lee et al., 2016 ). In Taiwan, Confucianism shapes another feature of parenting practice: the strong emphasis on academic achievement. The parents’ zeal for their children’s education is characteristic of Taiwan, even in comparison to academic emphasis in other East Asian countries. Hau and Ho ( 2010 ) noted that, in Eastern Asian (Chinese) cultures, academic achievement does not depend on the students’ interests. Chinese students typically do not regard intelligence as fixed, but trainable through learning, which enables them to take a persistent rather than a helpless approach to schoolwork, and subsequently perform well. In Chinese culture, academic achievement has been traditionally regarded as the passport to social success and reputation, and a way to enhance the family's social status (Hau & Ho, 2010 ). Therefore, parents dedicate a large part of their family resources to their children's education, a practice that is still prevalent in Taiwan today (Hsieh, 2020 ). Parental control aimed at better academic achievement is exerted within the behavioral and psychological domains. For instance, Taiwan parents tightly schedule and control their children’s time, planning private tutoring after school and on weekends. Parental control thus refers to “parental intrusiveness, pressure, or domination, with the inverse being parental support of autonomy” (Grolnick & Pomerantz, 2009 ). There are two types of parental control: behavioral and psychological. Behavioral control, which includes parental regulation and monitoring over what children do (Steinberg et al., 1992 ), predict positive psychosocial outcomes for children. Outcomes include low externalizing problems, high academic achievement (Stice & Barrera, 1995 ), and low depression. In contrast, psychological control, which is exerted over the children’s psychological world, is known to be problematic (Stolz et al., 2005 ). Psychological control involves strategies such as guilt induction and love withdrawal (Steinberg et al., 1992 ) and is related with disregard for children’s emotional autonomy and needs (Steinberg et al., 1992 ). Therefore, it is very important to discuss the type of parental control.

Troll et al. ( 2021 ) suggested that it is not the objective amount of smartphone use but the effective handling of smartphones that helps students with higher trait self-control to fare better academically. Heo and Lee ( 2021 ) discussed the mediating effect of self-control. They found that self-control was partially mediated by those who were not at risk for smartphone addiction. That is to say, smartphone addiction could be managed by strengthening self-control to promote healthy use. In an earlier study Hsieh and Lin ( 2021 ), we collected 41 international journal papers involving 136,491students across 15 countries, for meta-analysis. We found that the average and majority of the correlations were both negative. The short conclusion here was that smartphone addiction /reliance may have had a negative impact on learning performance. Clearly, it is very important to investigate the effect of self-control on learning effectiveness with regard to academic performance.

2.3 Smartphone use and its effects on learning effectiveness and academic performance

The impact of new technologies on learning or academic performance has been investigated in the literature. Kates et al. ( 2018 ) conducted a meta-analysis of 39 studies published over a 10-year period (2007–2018) to examine potential relationships between smartphone use and academic achievement. The effect of smartphone use on learning outcomes can be summarized as follows: r = − 0.16 with a 95% confidence interval of − 0.20 to − 0.13. In other words, smartphone use and academic achievement were negatively correlated. Amez and Beart ( 2020 ) systematically reviewed the literature on smartphone use and academic performance, observing the predominance of empirical findings supporting a negative correlation. However, they advised caution in interpreting this result because this negative correlation was less often observed in studies analyzing data collected through paper-and-pencil questionnaires than in studies on data collected through online surveys. Furthermore, this correlation was less often noted in studies in which the analyses were based on self-reported grade point averages than in studies in which actual grades were used. Salvation ( 2017 ) revealed that the type of smartphone applications and the method of use determined students’ level of knowledge and overall grades. However, this impact was mediated by the amount of time spent using such applications; that is, when more time is spent on educational smartphone applications, the likelihood of enhancement in knowledge and academic performance is higher. This is because smartphones in this context are used as tools to obtain the information necessary for assignments and tests or examinations. Lin et al. ( 2021 ) provided robust evidence that smartphones can promote improvements in academic performance if used appropriately.

In summary, the findings of empirical investigations into the effects of smartphone use have been inconsistent—positive, negative, or none. Thus, we explore the correlation between elementary school students’ smartphone use and learning effectiveness with regard to academic performance through the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3: Smartphone use is associated with learning effectiveness with regard to academic performance.

Hypothesis 4: Differences in smartphone use correspond to differences in learning effectiveness with regard to academic performance.

Hypotheses 1 to 4 are aimed at understanding the mediating effect of smartphone behavior; see Fig. 1 . It is assumed that smartphone behavior is the mediating variable, parental control and self-control are independent variables, and academic performance is the dependent variable. We want to understand the mediation effect of this model.

Model 1: Model to test the impact of parental control and students’ self-control on academic performance

Thus, the following hypotheses are presented.

Hypothesis 5: Smartphone behaviors are the mediating variable to impact the academic performance.

2.4 Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on smartphone use for online learning

According to 2020 statistics from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, full or partial school closures have affected approximately 800 million learners worldwide, more than half of the global student population. Schools worldwide have been closed for 14 to 22 weeks on average, equivalent to two thirds of an academic year (UNESCO, 2021 ). Because of the pandemic, instructors have been compelled to transition to online teaching (Carrillo & Flores, 2020 ). According to Tang et al. ( 2020 ), online learning is among the most effective responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the effectiveness of online learning for young children is limited by their parents’ technological literacy in terms of their ability to navigate learning platforms and use the relevant resources. Parents’ time availability constitutes another constraint (Dong et al., 2020 ). Furthermore, a fast and stable Internet connection, as well as access to devices such as desktops, laptops, or tablet computers, definitively affects equity in online education. For example, in 2018, 14% of households in the United States lacked Internet access (Morgan, 2020 ). In addition, the availability and stability of network connections cannot be guaranteed in relatively remote areas, including some parts of Australia (Park et al., 2021 ). In Japan, more than 50% of 3-year-old children and 68% of 6-year-old children used the Internet in their studies, but only 21% of households in Thailand have computer equipment (Park et al., 2021 ).

In short, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to changes in educational practices. With advances in Internet technology and computer hardware, online education has become the norm amid. However, the process and effectiveness of learning in this context is affected by multiple factors. Aside from the parents’ financial ability, knowledge of educational concepts, and technological literacy, the availability of computer equipment and Internet connectivity also exert impacts. This is especially true for elementary school students, who rely on their parents in online learning more than do middle or high school students, because of their short attention spans and undeveloped computer skills. Therefore, this study focuses on the use of smartphones by elementary school students during the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on learning effectiveness.

3.1 Participants

Participants were recruited through stratified random sampling. They comprised 499 Taiwanese elementary school students (in grades 5 and 6) who had used smartphones for at least 12 months. Specifically, the students advanced to grades 5 or 6 at the beginning of the 2018–2019 school year. Boys and girls accounted for 47.7% and 52.3% ( n = 238 and 261, respectively) of the sample.

3.2 Data collection and measurement

In 2020, a questionnaire survey was conducted to collect relevant data. Of the 620 questionnaires distributed, 575 (92.7%) completed questionnaires were returned. After 64 participants were excluded because they had not used their smartphones continually over the past 12 months and 14 participants were excluded for providing invalid responses, 499 individuals remained. The questionnaire was developed by one of the authors on the basis of a literature review. The questionnaire content can be categorized as follows: (1) students’ demographic characteristics, (2) smartphone use, (3) smartphone behavior, and (4) learning effectiveness. The questionnaire was modified according to evaluation feedback provided by six experts. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses were conducted to test the structural validity of the questionnaire. Factor analysis was performed using principal component analysis and oblique rotation. From the exploratory factor analysis, 25 items (15 and 10 items on smartphone behavior and academic performance as constructs, respectively) were extracted and confirmed. According to the results of the exploratory factor analysis, smartphone behavior can be classified into three dimensions: interpersonal communication, leisure and entertainment, and searching for information. Interpersonal communication is defined as when students use smartphones to communicate with classmates or friends, such as in response to questions like ‘I often use my smartphone to call or text my friends’. Leisure and entertainment mean that students spend a lot of their time using their smartphones for leisure and entertainment, e.g. ‘I often use my smartphone to listen to music’ or ‘I often play media games with my smartphone’. Searching for information means that students spend a lot of their time using their smartphones to search for information that will help them learn, such as in response to questions like this ‘I often use my smartphone to search for information online, such as looking up words in a dictionary’ or ‘I will use my smartphone to read e-books and newspapers online’.

Academic performance can be classified into three dimensions: learning activities, learning applications, and learning attitudes. Learning activities are when students use their smartphones to help them with learning, such as in response to a question like ‘I often use some online resources from my smartphone to help with my coursework’. Learning applications are defined as when students apply smartphone software to help them with their learning activities, e.g. ‘With a smartphone, I am more accustomed to using multimedia software’. Learning attitudes define the students’ attitudes toward using the smartphone, with questions like ‘Since I have had a smartphone, I often find class boring; using a smartphone is more fun’ (This is a reverse coded item). The factor analysis results are shown in the appendix (Appendix Tables 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 and 14 ). It can be seen that the KMO value is higher than 0.75, and the Bartlett’s test is also significant. The total variance explained for smartphone behavior is 53.47% and for academic performance it is 59.81%. These results demonstrate the validity of the research tool.

In this study, students were defined as "proactive" if they had asked their parents to buy a smartphone for their own use and "reactive" if their parents gave them a smartphone unsolicited (i.e. they had not asked for it). According to Heo and Lee ( 2021 ), students who proactively asked their parents to buy them a smartphone gave the assurance that they could control themselves and not become addicted, but if they had been given a smartphone (without having to ask for it), they did not need to offer their parents any such guarantees. They defined user addiction (meaning low self-control) as more than four hours of smartphone use per day (Peng et al., 2022 ).

A cross-tabulation of self-control results is presented in Table 2 , with the columns representing “proactive” and “reactive”, and the rows showing “high self-control” and “low self-control”. There are four variables in this cross-tabulation, “Proactive high self-control” (students promised parents they would not become smartphone addicts and were successful), “Proactive low self-control” (assured their parents they would not become smartphone addicts, but were unsuccessful), “Reactive high self-control”, and “Reactive low self-control”.

Regarding internal consistency among the constructs, the Cronbach's α values ranged from 0.850 to 0.884. According to the guidelines established by George and Mallery ( 2010 ), these values were acceptable because they exceeded 0.7. The overall Cronbach's α for the constructs was 0.922. The Cronbach's α value of the smartphone behavior construct was 0.850, whereas that of the academic performance construct was 0.884.

3.3 Data analysis

The participants’ demographic characteristics and smartphone use (expressed as frequencies and percentages) were subjected to a descriptive analysis. To examine hypotheses 1 and 2, an independent samples t test (for gender and grade) and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were performed to test the differences in smartphone use and learning effectiveness with respect to academic performance among elementary school students under various background variables. To test hypothesis 3, Pearson’s correlation analysis was conducted to analyze the association between smartphone behavior and academic performance. To test hypothesis 4, one-way multivariate ANOVA (MANOVA) was employed to examine differences in smartphone behavior and its impacts on learning effectiveness. To test Hypothesis 5, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to test whether smartphone behavior is a mediator of academic performance.

4.1 Descriptive analysis

The descriptive analysis (Table 1 ) revealed that the parents of 71.1% of the participants ( n = 499) conditionally controlled their smartphone use. Moreover, 42.5% of the participants noted that they started using smartphones in grade 3 or 4. Notably, 43.3% reported that they used their parents’ old smartphones; in other words, almost half of the students used secondhand smartphones. Overall, 79% of the participants indicated that they most frequently used their smartphones after school. Regarding smartphone use on weekends, 54.1% and 44.1% used their smartphones during the daytime and nighttime, respectively. Family members and classmates (45.1% and 43.3%, respectively) were the people that the participants communicated with the most on their smartphones. Regarding bringing their smartphones to school, 53.1% of the participants indicated that they were most concerned about losing their phones. As for smartphone use duration, 28.3% of the participants indicated that they used their smartphones for less than 1 h a day, whereas 24.4% reported using them for 1 to 2 h a day.

4.2 Smartphone behavior varies with parental control and based on students' self-control

We used the question ‘How did you obtain your smartphone?’ (to investigate proactivity), and ‘How much time do you spend on your smartphone in a day?’ (to investigate the effects of students' self-control). According to the Hsieh and Lin ( 2021 ), and Peng et al. ( 2022 ), addition is defined more than 4 h a day are defined as smartphone addiction (meaning that students have low self-control).

Table 2 gives the cross-tabulation results for self-control ability. Students who asked their parents to buy a smartphone, but use it for less than 4 h a day are defined as having ‘Proactive high self-control’; students using a smartphone for more than 4 h a day are defined as having ‘Proactive low self-control’. Students whose parents gave them a smartphone but use them for less than 4 h a day are defined as having ‘Reactive high self-control’; students given smart phones and using them for more than 4 h a day are defined as having ‘Reactive low self-control’; others, we define as having moderate levels of self-control.

Tables 3 – 5 present the results of the t test and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) on differences in the smartphone behaviors based on parental control and students' self-control. As mentioned, smartphone behavior can be classified into three dimensions: interpersonal communication, leisure and entertainment, and information searches. Table 3 lists the significant independent variables in the first dimension of smartphone behavior based on parental control and students' self-control. Among the students using their smartphones for the purpose of communication, the proportion of parents enforcing no control over smartphone use was significantly higher than the proportions of parents enforcing strict or conditional control ( F = 11.828, p < 0.001). This indicates that the lack of parental control over smartphone use leads to the participants spending more time using their smartphones for interpersonal communication.

For the independent variable of self-control, regardless of whether students had proactive high self-control, proactive low self-control or reactive low self-control, significantly higher levels of interpersonal communication than reactive high self-control were reported ( F = 18.88, p < 0.001). This means that students effectively able to control themselves, who had not asked their parents to buy them smartphones, spent less time using their smartphones for interpersonal communication. However, students with high self-control but who had asked their parents to buy them smartphones, would spend more time on interpersonal communication (meaning that while they may not spend a lot of time on their smartphones each day, the time spent on interpersonal communication is no different than for the other groups). Those without effective self-control, regardless of whether they had actively asked their parents to buy them a smartphone or not, would spend more time using their smartphones for interpersonal communication.

Table 4 displays the independent variables (parental control and students' self-control) significant in the dimension of leisure and entertainment. Among the students using their smartphones for this purpose, the proportion of parents enforcing no control over smartphone use was significantly higher than the proportions of parents enforcing strict or conditional control ( F = 8.539, p < 0.001). This indicates that the lack of parental control over smartphone use leads to the participants spending more time using their smartphones for leisure and entertainment.

For the independent variable of self-control, students with proactive low self-control and reactive low self-control reported significantly higher use of smartphones for leisure and entertainment than did students with proactive high self-control and reactive high self-control ( F = 8.77, p < 0.001). This means that students who cannot control themselves, whether proactive or passive in terms of asking their parents to buy them a smartphone, will spend more time using their smartphones for leisure and entertainment.

Table 5 presents the significant independent variables in the dimension of information searching. Significant differences were observed only for gender, with a significantly higher proportion of girls using their smartphones to search for information ( t = − 3.979, p < 0.001). Parental control and students' self-control had no significance in the dimension of information searching. This means that the parents' attitudes towards control did not affect the students' use of smartphones for information searches. This is conceivable, as Asian parents generally discourage their children from using their smartphones for non-study related activities (such as entertainment or making friends), but not for learning-related activities. It is also worth noting that student self-control was not significant in relation to searching for information. This means that it makes no difference whether or not students have self-control in their search for learning-related information.

Four notable results are presented as follows.

First, a significantly higher proportion of girls used their smartphones to search for information. Second, if smartphone use was not subject to parental control, the participants spent more time using their smartphones for interpersonal communication and for leisure and entertainment rather than for information searches. This means that if parents make the effort to control their children's smartphone use, this will reduce their children's use of smartphones for interpersonal communication and entertainment. Third, student self-control affects smartphone use behavior for interpersonal communication and entertainment (but not searching for information). This does not mean that they spend more time on their smartphones in their daily lives, it means that they spend the most time interacting with people while using their smartphones (For example, they may only spend 2–3 h a day using their smartphone. During those 2–3 h, they spend more than 90% of their time interacting with people and only 10% doing other things), which is the fourth result.

These results support hypotheses 1 and 2.

4.3 Pearson’s correlation analysis of smartphone behavior and academic performance

Table 6 presents the results of Pearson’s correlation analysis of smartphone behavior and academic performance. Except for information searches and learning attitudes, all variables exhibited significant and positively correlations. In short, there was a positive correlation between smartphone behavior and academic performance. Thus, hypothesis 3 is supported.

4.4 Analysis of differences in the academic performance of students with different smartphone behaviors

Differences in smartphone behavior and its impacts on learning effectiveness with regard to academic performance were examined through. In step 1, cluster analysis was conducted to convert continuous variables into discrete variables. In step 2, a one-way MANOVA was performed to analyze differences in the academic performance of students with varying smartphone behavior. Regarding the cluster analysis results (Table 7 ), the value of the change in the Bayesian information criterion in the second cluster was − 271.954, indicating that it would be appropriate to group the data. Specifically, we assigned the participants into either the high smartphone use group or the low smartphone use group, comprised of 230 and 269 participants (46.1% and 53.9%), respectively.

The MANOVA was preceded by the Levene test for the equality of variance, which revealed nonsignificant results, F (6, 167,784.219) = 1.285, p > 0.05. Thus, we proceeded to use MANOVA to examine differences in the academic performance of students with differing smartphone behaviors (Table 8 ). Between-group differences in academic performance were significant, F (3, 495) = 44.083, p < 0.001, Λ = 0.789, η 2 = 0.211, power = 0.999. Subsequently, because academic performance consists of three dimensions, we performed univariate tests and an a posteriori comparison.

Table 9 presents the results of the univariate tests. Between-group differences in learning activities were significant, ( F [1, 497] = 40.8, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.076, power = 0.999). Between-group differences in learning applications were also significant ( F [1, 497] = 117.98, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.192, power = 0.999). Finally, differences between the groups in learning attitudes were significant ( F [1, 497] = 23.22, p < 0.001, η 2 = 0.045, power = 0.998). The a posteriori comparison demonstrated that the high smartphone use group significantly outperformed the low smartphone use group in all dependent variables with regard to academic performance. Thus, hypothesis 4 is supported.

4.5 Smartphone behavior as the mediating variable impacting academic performance

As suggested by Baron and Kenny ( 1986 ), smartphone behavior is a mediating variable affecting academic performance. We examined the impact through the following four-step process:

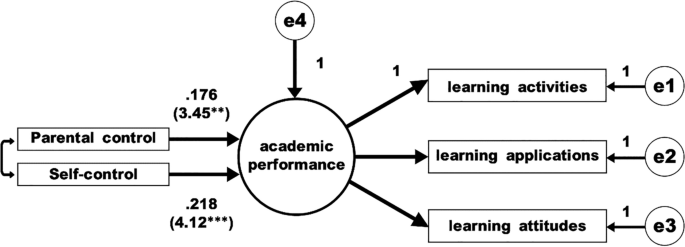

Step 1. The independent variable (parental control and students' self-control) must have a significant effect on the dependent variable (academic performance), as in model 1 (please see Fig. 1 ).

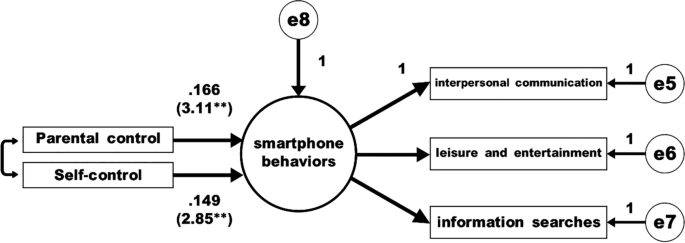

Step 2. The independent variable (parental control and students' self-control) must have a significant effect on the mediating variable (smartphone behaviors), as in model 2 (please see Fig. 2 ).

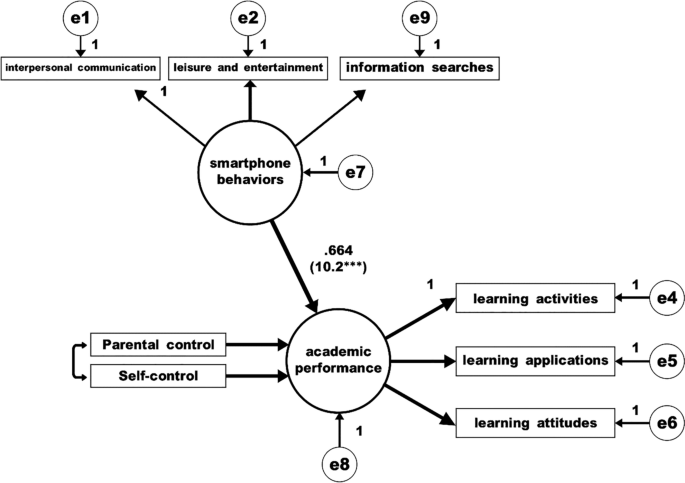

Step 3. When both the independent variable (parental control and student self-control) and the mediator (smartphone behavior) are used as predictors, the mediating variable (smartphone behavior) must have a significant effect on the dependent variable (academic performance), as in model 3 (please see Fig. 3 ).

Step 4. In model 3, the regression coefficient of the independent variables (parental control and student self-control) on the dependent variables must be less than in mode 1 or become insignificant.

Model 2: Model to test the impact of parental control and students’ self-control on smartphone behavior

Model 3: Both independent variables (parental control and student self-control) and mediators (smartphone behavior) were used as predictors to predict dependent variables

As can be seen in Fig. 1 , parental control and student self-control are observed variables, and smartphone behavior is a latent variable. "Strict" is set to 0, which means "Conditional", with "None" compared to "Strict". “Proactive high self-control” is also set to 0. From Fig. 1 we find that the independent variables have a significant effect on the dependent variable. The regression coefficient of parental control is 0.176, t = 3.45 ( p < 0.01); the regression coefficient of students’ self-control is 0.218, t = 4.12 ( p < 0.001), proving the fit of the model (Chi Square = 13.96**, df = 4, GFI = 0.989, AGFI = 0.959, CFI = 0.996, TLI = 0.915, RMSEA = 0.051, SRMR = 0.031). Therefore, the test results for Model 1 are in line with the recommendations of Baron and Kenny ( 1986 ).

As can be seen in Fig. 2 , the independent variables have a significant effect on smartphone behaviors. The regression coefficient of parental control is 0.166, t = 3.11 ( p < 0.01); the regression coefficient of students’ self-control is 0.149, t = 2.85 ( p < 0.01). The coefficients of the model fit are: Chi Square = 15.10**, df = 4, GFI = 0.988, AGFI = 0.954, CFI = 0.973, TLI = 0.932, RMSEA = 0.052, SRMR = 0.039. Therefore, the results of the test of Model 2 are in line with the recommendations of Baron and Kenny ( 1986 ).

As can be seen in Fig. 3 , smartphone behaviors have a significant effect on the dependent variable. The regression coefficient is 0.664, t = 10.2 ( p < 0.001). The coefficients of the model fit are: Chi Square = 91.04**, df = 16, GFI = 0.958, AGFI = 0.905, CFI = 0.918, TLI = 0.900, RMSEA = 0.077, SRMR = 0.063. Therefore, the results of the test of Model 3 are in line with the recommendations of Baron and Kenny ( 1986 ).

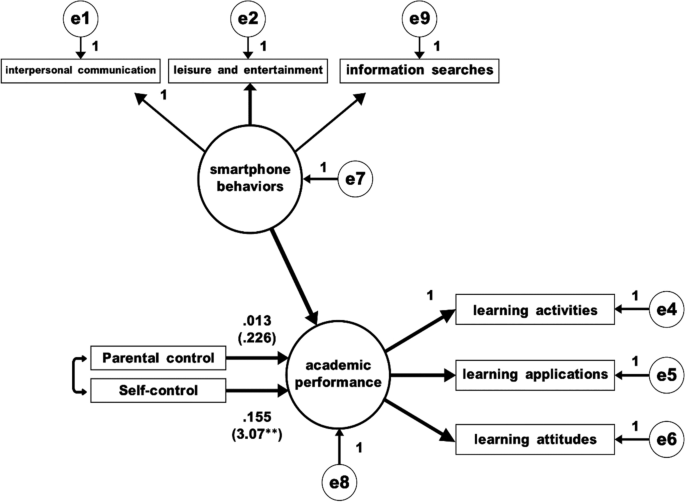

As can be seen in Fig. 4 , the regression coefficient of the independent variables (parental control and student self-control) on the dependent variables is less than in model 1, and the parental control variable becomes insignificant. The regression coefficient of parental control is 0.013, t = 0.226 ( p > 0.05); the path coefficient of students’ self-control is 0.155, t = 3.07 ( p < 0.01).

Model 4: Model three’s regression coefficient of the independent variables (parental control and student self-control) on the dependent variables

To sum up, we prove that smartphone behavior is the mediating variable to impact the academic performance. Thus, hypothesis 5 is supported.

5 Discussion

This study investigated differences in the smartphone behavior of fifth and sixth graders in Taiwan with different background variables (focus on parental control and students’ self-control) and their effects on academic performance. The correlation between smartphone behavior and academic performance was also examined. Although smartphones are being used in elementary school learning activities, relatively few studies have explored their effects on academic performance. In this study, the proportion of girls who used smartphones to search for information was significantly higher than that of boys. Past studies have been inconclusive about gender differences in smartphone use. Lee and Kim ( 2018 ) observed no gender differences in smartphone use, but did note that boys engaged in more smartphone use if their parents set fewer restrictions. Kim et al. ( 2019 ) found that boys exhibited higher levels of smartphone dependency than girls. By contrast, Kim ( 2017 ) reported that girls had higher levels of smartphone dependency than boys did. Most relevant studies have focused on smartphone dependency; comparatively little attention has been devoted to smartphone behavior. The present study contributes to the literature in this regard.

Notably, this study found that parental control affected smartphone use. If the participants’ parents imposed no restrictions, students spent more time on leisure and entertainment and on interpersonal communication rather than on information searches. This is conceivable, as Asian parents generally discourage their children from using their smartphones for non-study related activities (such as entertainment or making friends) but not for learning-related activities. If Asian parents believe that using a smartphone can improve their child's academic performance, they will encourage their child to use it. Parents in Taiwan attach great importance to their children's academic performance (Lee et al., 2016 ). A considerable amount of research has been conducted on parental attitudes or control in this context. Hwang and Jeong ( 2015 ) suggested that parental attitudes mediated their children’s smartphone use. Similarly, Chang et al. ( 2019 ) observed that parental attitudes mediated the smartphone use of children in Taiwan. Our results are consistent with extant evidence in this regard. Lee and Ogbolu ( 2018 ) demonstrated that the stronger children’s perception was of parental control over their smartphone use, the more frequently they used their smartphones. The study did not further explain the activities the children engaged in on their smartphones after they increased their frequency of use. In the present study, the participants spent more time on their smartphones for leisure and entertainment and for interpersonal communication than for information searches.

Notably, this study also found that students’ self-control affected smartphone use.

Regarding the Pearson’s correlation analysis of smartphone behavior and academic performance, except for information searches and learning attitudes, all the variables were significantly positively correlated. In other words, there was a positive correlation between smartphone behavior and academic performance. In their systematic review, Amez and Beart ( 2020 ) determined that most empirical results provided evidence of a negative correlation between smartphone behavior and academic performance, playing a more considerable role in that relationship than the theoretical mechanisms or empirical methods in the studies they examined. The discrepancy between our results and theirs can be explained by the between-study variations in the definitions of learning achievement or performance.

Regarding the present results on the differences in the academic performance of students with varying smartphone behaviors, we carried out a cluster analysis, dividing the participants into a high smartphone use group and a low smartphone use group. Subsequent MANOVA revealed that the high smartphone use group academically outperformed the low smartphone use group; significant differences were noted in the academic performance of students with different smartphone behaviors. Given the observed correlation between smartphone behavior and academic performance, this result is not unexpected. The findings on the relationship between smartphone behavior and academic performance can be applied to smartphone use in the context of education.

Finally, in a discussion of whether smartphone behavior is a mediator of academic performance, it is proved that smartphone behavior is the mediating variable impacting academic performance. Our findings show that parental control and students’ self-control can affect academic performance. However, the role of the mediating variable (smartphone use behavior) means that changes in parental control have no effect on academic achievement at all. This means that smartphone use behaviors have a full mediating effect on parental control. It is also found that students’ self-control has a partial mediating effect. Our findings suggest that parental attitudes towards the control of smartphone use and students' self-control do affect academic performance, but smartphone use behavior has a significant mediating effect on this. In other words, it is more important to understand the children's smartphone behavior than to control their smartphone usage. There have been many studies in the past exploring the mediator variables for smartphone use addiction and academic performance. For instance, Ahmed et al. ( 2020 ) found that the mediating variables of electronic word of mouth (eWOM) and attitude have a significant and positive influence in the relationship between smartphone functions. Cho and Lee ( 2017 ) found that parental attitude is the mediating variable for smartphone use addiction. Cho et al. ( 2017 ) indicated that stress had a significant influence on smartphone addiction, while self-control mediates that influence. In conclusion, the outcomes demonstrate that parental control and students’ self-control do influence student academic performance in primary school. Previous studies have offered mixed results as to whether smartphone usage has an adverse or affirmative influence on student academic performance. This study points out a new direction, thinking of smartphone use behavior as a mediator.

In brief, the participants spent more smartphone time on leisure and entertainment and interpersonal communication, but the academic performance of the high smartphone use group surpassed that of the low smartphone use group. This result may clarify the role of students’ communication skills in their smartphone use. As Kang and Jung ( 2014 ) noted, conventional communication methods have been largely replaced by mobile technologies. This suggests that students’ conventional communication skills are also shifting to accommodate smartphone use. Elementary students are relatively confident in communicating with others through smartphones; thus, they likely have greater self‐efficacy in this regard and in turn may be better able to improve their academic performance by leveraging mobile technologies. This premise requires verification through further research. Notably, high smartphone use suggests the greater availability of time and opportunity in this regard. Conversely, low smartphone use suggests the relative lack of such time and opportunity. The finding that the high smartphone use group academically outperformed the low smartphone use group also indicates that smartphone accessibility constitutes a potential inequality in the learning opportunities of elementary school students. Therefore, elementary school teachers must be aware of this issue, especially in view of the shift to online learning triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, when many students are dependent on smartphones and computers for online learning.

6 Conclusions and implications

This study examined the relationship between smartphone behavior and academic performance for fifth and sixth graders in Taiwan. Various background variables (parental control and students’ self-control) were also considered. The findings provide new insights into student attitudes toward smartphone use and into the impacts of smartphone use on academic performance. Smartphone behavior and academic performance were correlated. The students in the high smartphone use group academically outperformed the low smartphone use group. This result indicates that smartphone use constitutes a potential inequality in elementary school students’ learning opportunities. This can be explained as follows: high smartphone use suggests that the participants had sufficient time and opportunity to access and use smartphones. Conversely, low smartphone use suggests that the participants did not have sufficient time and opportunity for this purpose. Students’ academic performance may be adversely affected by fewer opportunities for access. Disparities between their performance and that of their peers with ready access to smartphones may widen amid the prevalent class suspension and school closure during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

This study has laid down the basic foundations for future studies concerning the influence of smartphones on student academic performance in primary school as the outcome variable. This model can be replicated and applied to other social science variables which can influence the academic performance of primary school students as the outcome variable. Moreover, the outcomes of this study can also provide guidelines to teachers, parents, and policymakers on how smartphones can be most effectively used to derive the maximum benefits in relation to academic performance in primary school as the outcome variable. Finally, the discussion of the mediating variable can also be used as the basis for the future projects.

7 Limitations and areas of future research

This research is significant in the field of smartphone functions and the student academic performance for primary school students. However, certain limitations remain. The small number of students sampled is the main problem in this study. For more generalized results, the sample data may be taken across countries within the region and increased in number (rather than limited to certain cities and countries). For more robust results, data might also be obtained from both rural and urban centers. In this study, only one mediating variable was incorporated, but in future studies, several other psychological and behavioral variables might be included for more comprehensive outcomes. We used the SEM-based multivariate approach which does not address the cause and effect between the variables, therefore, in future work, more robust models could be employed for cause-and-effect investigation amongst the variables.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Ahmed, R. R., Salman, F., Malik, S. A., Streimikiene, D., Soomro, R. H., & Pahi, M. H. (2020). Smartphone Use and Academic Performance of University Students: A Mediation and Moderation Analysis. Sustainability, 12 (1), 439. MDPI AG. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.3390/su12010439

Amez, S., & Beart, S. (2020). Smartphone use and academic performance: A literature review. International Journal of Educational Research, 103 , 101618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101618

Article Google Scholar

Anshari, M., Almunawar, M. N., Shahrill, M., Wicaksono, D. K., & Huda, M. (2017). Smartphones usage in the classrooms: Learning aid or interference? Education and Information Technologies, 22 , 3063–3079. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-017-9572-7

Bae, S. M. (2015). The relationships between perceived parenting style, learning motivation, friendship satisfaction, and the addictive use of smartphones with elementary school students of South Korea: Using multivariate latent growth modeling. School Psychology International, 36 (5), 513–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034315604017

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51 (6), 1173–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173

Bluestein, S. A., & Kim, T. (2017). Expectations and fulfillment of course engagement, gained skills, and non-academic usage of college students utilizing tablets in an undergraduate skills course. Education and Information Technologies, 22 (4), 1757–1770. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-016-9515-8

Carrillo, C., & Flores, M. A. (2020). COVID-19 and teacher education: A literature review of online teaching and learning practices. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43 (4), 466–487. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1821184

Chang, F. C., Chiu, C. H., Chen, P. H., Chiang, J. T., Miao, N. F., Chuang, H. T., & Liu, S. (2019). Children’s use of mobile devices, smartphone addiction and parental mediation in Taiwan. Computers in Human Behavior, 93 , 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.11.048

Chen, R. S., & Ji, C. H. (2015). Investigating the relationship between thinking style and personal electronic device use and its implications for academic performance. Computers in Human Behavior, 52 , 177–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.05.042

Chen, C., Chen, S., Wen, P., & Snow, C. E. (2020). Are screen devices soothing children or soothing parents?Investigating the relationships among children’s exposure to different types of screen media, parental efficacy and home literacy practices. Computers in Human Behavior, 112 , 106462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106462

Cheng, Y. M., Kuo, S. H., Lou, S. J., & Shih, R. C. (2016). The development and implementation of u-msg for college students’ English learning. International Journal of Distance Education Technologies, 14 (2), 17–29. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJDET.2016040102

Cho, K. S., & Lee, J. M. (2017). Influence of smartphone addiction proneness of young children on problematic behaviors and emotional intelligence: Mediating self-assessment effects of parents using smartphones. Computers in Human Behavior, 66 , 303–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.09.063

Cho, H.-Y., Kim, K. J., & Park, J. W. (2017). Stress and adult smartphone addiction: Mediation by self-control, neuroticism, and extraversion. Stress and Heath, 33 , 624–630. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2749

Clayton, K., & Murphy, A. (2016). Smartphone apps in education: Students create videos to teach smartphone use as tool for learning. Journal of Media Literacy Education , 8 , 99–109. Retrieved October 13, 2021. Review from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1125609.pdf

Daems, K., Pelsmacker, P. D., & Moons, I. (2019). The effect of ad integration and interactivity on young teenagers’ memory, brand attitude and personal data sharing. Computers in Human Behavior, 99 , 245–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.05.031

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across life’s domains. Canadian Psychology, 49 (1), 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/0708-5591.49.1.14

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review of experiments examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125 , 627–668. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.125.6.627

Dong, C., Cao, S., & Li, H. (2020). Young children’s online learning during COVID-19 pandemic: Chinese parents’ beliefs and attitudes. Children and Youth Services Review, 118 , 105440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105440

Du, J., van Koningsbruggen, G. M., & Kerkhof, P. (2018). A brief measure of social media self-control failure. Computers in Human Behavior, 84 , 68–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.002

Firmansyah, R. O., Hamdani, R. A., & Kuswardhana, D. (2020). IOP conference series: Materials science and engineering. The use of smartphone on learning activities: Systematic review . In International Symposium on Materials and Electrical Engineering 2019 (ISMEE 2019), Bandung, Indonesia. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/850/1/012006

Garbe, A., Ogurlu, U., Logan, N., & Cook, P. (2020). COVID-19 and remote learning: Experiences of parents with children during the pandemic. American Journal of Qualitative Research, 4 (3), 45–65. https://doi.org/10.29333/ajqr/8471

George, D., & Mallery, P. (2010). SPSS for windows step by step: A simple guide and reference. 17.0 update (10th ed.). Pearson.

Google Scholar

Grant, M., & Hsu, Y. C. (2014). Making personal and professional learning mobile: Blending mobile devices, social media, social networks, and mobile apps to support PLEs, PLNs, & ProLNs. Advances in Communications and Media Research Series, 10 , 27–46.

Grolnick, W. S., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2009). Issues and challenges in studying parental control: Toward a new conceptualization. Child Development Perspectives, 3 , 165–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2009.00099.x

Guo, Z., Lu, X., Li, Y., & Li, Y. (2011). A framework of students’ reasons for using CMC media in learning contexts: A structural approach. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 62 (11), 2182–2200. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21631

Hadad, S., Meishar-Tal, H., & Blau, I. (2020). The parents’ tale: Why parents resist the educational use of smartphones at schools? Computers & Education, 157 , 103984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103984

Hau, K.-T., & Ho, I. T. (2010). Chinese students’ motivation and achievement. In M. H. Bond (Ed.), Oxford handbook of Chinese psychology (pp. 187–204). Oxford University Press.

Hawi, N. S., & Samaha, M. (2016). To excel or not to excel: Strong evidence on the adverse effect of smartphone addiction on academic performance. Computers & Education, 98 , 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.03.007

Heo, Y. J., & Lee, K. (2021). Smartphone addiction and school life adjustment among high school students: The mediating effect of self-control. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 56 (11), 28–36. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20180503-06

Hofmann, W., Friese, M., & Strack, F. (2009). Impulse and self-control from a dual-systems perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4 (2), 162–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01116.x

Hsieh, C. Y. (2020). Predictive analysis of instruction in science to students’ declining interest in science-An analysis of gifted students of sixth - and seventh-grade in Taiwan. International Journal of Engineering Education, 2 (1), 33–51. https://doi.org/10.14710/ijee.2.1.33-51

Hsieh, C. Y., Lin, C. H. (2021). Other important issues. Meta-analysis: the relationship between smartphone addiction and college students’ academic performance . 2021 TERA International Conference on Education. IN National Sun Yat-sen University (NSYSU), Kaohsiung.

Hwang, Y., & Jeong, S. H. (2015). Predictors of parental mediation regarding children’s smartphone use. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18 (12), 737–743. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0286

Jeong, S.-H., Kim, H. J., Yum, J.-Y., & Hwang, Y. (2016). What type of content are smartphone users addicted to? SNS vs. games. Computers in Human Behavior, 54 , 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.035

Judd, T. (2014). Making sense of multitasking: The role of facebook. Computers & Education, 70 , 194–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.08.013

Junco, R., & Cotton, S. R. (2012). No A 4 U: The relationship between multitasking and academic performance. Computers & Education, 59 , 505–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.12.023

Kang, S., & Jung, J. (2014). Mobile communication for human needs: A comparison of smartphone use between the US and Korea. Computers in Human Behavior, 35 , 376–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.024

Karikoski, J., & Soikkeli, T. (2013). Contextual usage patterns in smartphone communication services. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 17 (3), 491–502. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-011-0503-0

Karpinski, A. C., Kirschner, P. A., Ozer, I., Mellott, J. A., & Ochwo, P. (2013). An exploration of social networking site use, multitasking, and academic performance among United States and European university students. Computers in Human Behavior, 29 , 1182–1192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.10.011

Kates, A. W., Wu, H., & Coryn, C. L. S. (2018). The effects of mobile phone use on academic performance: A meta-analysis. Computers & Education, 127 , 107–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.08.012

Kim, K. (2017). Smartphone addiction and the current status of smartphone usage among Korean adolescents. Studies in Humanities and Social Sciences, 2017 (56), 115–142. https://doi.org/10.17939/hushss.2017.56.006

Kim, D., Chun, H., & Lee, H. (2014). Determining the factors that influence college students’ adoption of smartphones. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65 (3), 578–588. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22987

Kim, B., Jahng, K. E., & Oh, H. (2019). The moderating effect of elementary school students’ perception of open communication with their parents in the relationship between smartphone dependency and school adjustment. Korean Journal of Childcare and Education, 15 (1), 54–73. https://doi.org/10.14698/jkcce.2019.15.01.057

Lee, J., & Cho, B. (2015). Effects of self-control and school adjustment on smartphone addiction among elementary school students. Korea Science, 11 (3), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.5392/IJoC.2015.11.3.001

Lee, E. J., & Kim, H. S. (2018). Gender differences in smartphone addiction behaviors associated with parent-child bonding, parent-child communication, and parental mediation among Korean elementary school students. Journal of Addictions Nursing, 29 (4), 244–254. https://doi.org/10.1097/JAN.0000000000000254

Lee, S. J., & Moon, H. J. (2013). Effects of self-Control, parent- adolescent communication, and school life satisfaction on smart-phone addiction for middle school students. Korean Journal of Human Ecology, 22 (6), 87–598. https://doi.org/10.5934/kjhe.2013.22.6.587

Lee, E. J., & Ogbolu, Y. (2018). Does parental control work with smartphone addiction? Journal of Addictions Nursing, 29 (2), 128–138. https://doi.org/10.1097/JAN.0000000000000222

Lee, J., Cho, B., Kim, Y., & Noh, J. (2015). Smartphone addiction in university students and its implication for learning. In G. Chen, V. K. Kinshuk, R. Huang, & S. C. Kong (Eds.), Emerging issues in smart learning (pp. 297–305). Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Lee, S., Lee, K., Yi, S. H., Park, H. J., Hong, Y. J., & Cho, H. (2016). Effects of Parental Psychological Control on Child’s School Life: Mobile Phone Dependency as Mediator. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25 , 407–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0251-2

Lepp, A., Barkley, J. E., & Karpinski, A. C. (2014). The relationship between cell phone use, academic performance, anxiety, and satisfaction with life in college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 31 , 343–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.049

Lin, Y. Q., Liu, Y., Fan, W. J., Tuunainen, V. K., & Deng, S. G. (2021). Revisiting the relationship between smartphone use and academic performance: A large-scale study. Computers in Human Behavior, 122 , 106835. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106835

Looi, C. K., Lim, K. F., Pang, J., Koh, A. L. H., Seow, P., Sun, D., Boticki, I., Norris, C., & Soloway, E. (2016). Bridging formal and informal learning with the use of mobile technology. In C. S. Chai, C. P. Lim, & C. M. Tan (Eds.), Future learning in primary schools (pp. 79–96). Springer.

Martin, F., & Ertzberger, J. (2013). Here and now mobile learning: An experimental study on the use of mobile technology. Computers & Education, 68 , 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.04.021

Meier, A. (2017). Neither pleasurable nor virtuous: Procrastination links smartphone habits and messenger checking behavior to decreased hedonic as well as eudaimonic well-being . Paper presented at the 67th Annual Conference of the International Communication Association (ICA), San Diego, CA.

Morgan, H. (2020). Best practices for implementing remote learning during a pandemic. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 93 (3), 135–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.2020.1751480

Park, J. H. (2020). Smartphone use patterns of smartphone-dependent children. Korean Academy of Child Health Nursing, 26 (1), 47–54. https://doi.org/10.4094/chnr.2020.26.1.47

Park, N., & Lee, H. (2012). Social implications of smartphone use: Korean college students’ smartphone use and psychological well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15 (9), 491–497. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2011.0580

Park, E., Logan, H., Zhang, L., Kamigaichi, N., & Kulapichitr, U. (2021). Responses to coronavirus pandemic in early childhood services across five countries in the Asia-Pacific region: OMEP Policy Forum. International Journal of Early Childhood, 2021 , 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-020-00278-0

Peng, Y., Zhou, H., Zhang, B., Mao, H., Hu, R., & Jiang, H. (2022). Perceived stress and mobile phone addiction among college students during the 2019 coronavirus disease: The mediating roles of rumination and the moderating role of self-control. Personality and Individual Differences, 185 , 111222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111222

Reinecke, L., Aufenanger, S., Beutel, M. E., Dreier, M., Quiring, O., Stark, B., & Müller, K. W. (2017). Digital stress over the life span: The effects of communication load and Internet multitasking on perceived stress and psychological health impairments in a German probability sample. Media Psychology, 20 (1), 90–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2015.1121832