Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

8.3 Drafting

Learning objectives.

- Identify drafting strategies that improve writing.

- Use drafting strategies to prepare the first draft of an essay.

Drafting is the stage of the writing process in which you develop a complete first version of a piece of writing.

Even professional writers admit that an empty page scares them because they feel they need to come up with something fresh and original every time they open a blank document on their computers. Because you have completed the first two steps in the writing process, you have already recovered from empty page syndrome. You have hours of prewriting and planning already done. You know what will go on that blank page: what you wrote in your outline.

Getting Started: Strategies For Drafting

Your objective for this portion of Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” is to draft the body paragraphs of a standard five-paragraph essay. A five-paragraph essay contains an introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. If you are more comfortable starting on paper than on the computer, you can start on paper and then type it before you revise. You can also use a voice recorder to get yourself started, dictating a paragraph or two to get you thinking. In this lesson, Mariah does all her work on the computer, but you may use pen and paper or the computer to write a rough draft.

Making the Writing Process Work for You

What makes the writing process so beneficial to writers is that it encourages alternatives to standard practices while motivating you to develop your best ideas. For instance, the following approaches, done alone or in combination with others, may improve your writing and help you move forward in the writing process:

- Begin writing with the part you know the most about. You can start with the third paragraph in your outline if ideas come easily to mind. You can start with the second paragraph or the first paragraph, too. Although paragraphs may vary in length, keep in mind that short paragraphs may contain insufficient support. Readers may also think the writing is abrupt. Long paragraphs may be wordy and may lose your reader’s interest. As a guideline, try to write paragraphs longer than one sentence but shorter than the length of an entire double-spaced page.

- Write one paragraph at a time and then stop. As long as you complete the assignment on time, you may choose how many paragraphs you complete in one sitting. Pace yourself. On the other hand, try not to procrastinate. Writers should always meet their deadlines.

- Take short breaks to refresh your mind. This tip might be most useful if you are writing a multipage report or essay. Still, if you are antsy or cannot concentrate, take a break to let your mind rest. But do not let breaks extend too long. If you spend too much time away from your essay, you may have trouble starting again. You may forget key points or lose momentum. Try setting an alarm to limit your break, and when the time is up, return to your desk to write.

- Be reasonable with your goals. If you decide to take ten-minute breaks, try to stick to that goal. If you told yourself that you need more facts, then commit to finding them. Holding yourself to your own goals will create successful writing assignments.

- Keep your audience and purpose in mind as you write. These aspects of writing are just as important when you are writing a single paragraph for your essay as when you are considering the direction of the entire essay.

Of all of these considerations, keeping your purpose and your audience at the front of your mind is the most important key to writing success. If your purpose is to persuade, for example, you will present your facts and details in the most logical and convincing way you can.

Your purpose will guide your mind as you compose your sentences. Your audience will guide word choice. Are you writing for experts, for a general audience, for other college students, or for people who know very little about your topic? Keep asking yourself what your readers, with their background and experience, need to be told in order to understand your ideas. How can you best express your ideas so they are totally clear and your communication is effective?

You may want to identify your purpose and audience on an index card that you clip to your paper (or keep next to your computer). On that card, you may want to write notes to yourself—perhaps about what that audience might not know or what it needs to know—so that you will be sure to address those issues when you write. It may be a good idea to also state exactly what you want to explain to that audience, or to inform them of, or to persuade them about.

Writing at Work

Many of the documents you produce at work target a particular audience for a particular purpose. You may find that it is highly advantageous to know as much as you can about your target audience and to prepare your message to reach that audience, even if the audience is a coworker or your boss. Menu language is a common example. Descriptions like “organic romaine” and “free-range chicken” are intended to appeal to a certain type of customer though perhaps not to the same customer who craves a thick steak. Similarly, mail-order companies research the demographics of the people who buy their merchandise. Successful vendors customize product descriptions in catalogs to appeal to their buyers’ tastes. For example, the product descriptions in a skateboarder catalog will differ from the descriptions in a clothing catalog for mature adults.

Using the topic for the essay that you outlined in Section 8.2 “Outlining” , describe your purpose and your audience as specifically as you can. Use your own sheet of paper to record your responses. Then keep these responses near you during future stages of the writing process.

My purpose: ____________________________________________

____________________________________________

My audience: ____________________________________________

Setting Goals for Your First Draft

A draft is a complete version of a piece of writing, but it is not the final version. The step in the writing process after drafting, as you may remember, is revising. During revising, you will have the opportunity to make changes to your first draft before you put the finishing touches on it during the editing and proofreading stage. A first draft gives you a working version that you can later improve.

Workplace writing in certain environments is done by teams of writers who collaborate on the planning, writing, and revising of documents, such as long reports, technical manuals, and the results of scientific research. Collaborators do not need to be in the same room, the same building, or even the same city. Many collaborations are conducted over the Internet.

In a perfect collaboration, each contributor has the right to add, edit, and delete text. Strong communication skills, in addition to strong writing skills, are important in this kind of writing situation because disagreements over style, content, process, emphasis, and other issues may arise.

The collaborative software, or document management systems, that groups use to work on common projects is sometimes called groupware or workgroup support systems.

The reviewing tool on some word-processing programs also gives you access to a collaborative tool that many smaller workgroups use when they exchange documents. You can also use it to leave comments to yourself.

If you invest some time now to investigate how the reviewing tool in your word processor works, you will be able to use it with confidence during the revision stage of the writing process. Then, when you start to revise, set your reviewing tool to track any changes you make, so you will be able to tinker with text and commit only those final changes you want to keep.

Discovering the Basic Elements of a First Draft

If you have been using the information in this chapter step by step to help you develop an assignment, you already have both a formal topic outline and a formal sentence outline to direct your writing. Knowing what a first draft looks like will help you make the creative leap from the outline to the first draft. A first draft should include the following elements:

- An introduction that piques the audience’s interest, tells what the essay is about, and motivates readers to keep reading.

- A thesis statement that presents the main point, or controlling idea, of the entire piece of writing.

- A topic sentence in each paragraph that states the main idea of the paragraph and implies how that main idea connects to the thesis statement.

- Supporting sentences in each paragraph that develop or explain the topic sentence. These can be specific facts, examples, anecdotes, or other details that elaborate on the topic sentence.

- A conclusion that reinforces the thesis statement and leaves the audience with a feeling of completion.

These elements follow the standard five-paragraph essay format, which you probably first encountered in high school. This basic format is valid for most essays you will write in college, even much longer ones. For now, however, Mariah focuses on writing the three body paragraphs from her outline. Chapter 9 “Writing Essays: From Start to Finish” covers writing introductions and conclusions, and you will read Mariah’s introduction and conclusion in Chapter 9 “Writing Essays: From Start to Finish” .

The Role of Topic Sentences

Topic sentences make the structure of a text and the writer’s basic arguments easy to locate and comprehend. In college writing, using a topic sentence in each paragraph of the essay is the standard rule. However, the topic sentence does not always have to be the first sentence in your paragraph even if it the first item in your formal outline.

When you begin to draft your paragraphs, you should follow your outline fairly closely. After all, you spent valuable time developing those ideas. However, as you begin to express your ideas in complete sentences, it might strike you that the topic sentence might work better at the end of the paragraph or in the middle. Try it. Writing a draft, by its nature, is a good time for experimentation.

The topic sentence can be the first, middle, or final sentence in a paragraph. The assignment’s audience and purpose will often determine where a topic sentence belongs. When the purpose of the assignment is to persuade, for example, the topic sentence should be the first sentence in a paragraph. In a persuasive essay, the writer’s point of view should be clearly expressed at the beginning of each paragraph.

Choosing where to position the topic sentence depends not only on your audience and purpose but also on the essay’s arrangement, or order. When you organize information according to order of importance, the topic sentence may be the final sentence in a paragraph. All the supporting sentences build up to the topic sentence. Chronological order may also position the topic sentence as the final sentence because the controlling idea of the paragraph may make the most sense at the end of a sequence.

When you organize information according to spatial order, a topic sentence may appear as the middle sentence in a paragraph. An essay arranged by spatial order often contains paragraphs that begin with descriptions. A reader may first need a visual in his or her mind before understanding the development of the paragraph. When the topic sentence is in the middle, it unites the details that come before it with the ones that come after it.

As you read critically throughout the writing process, keep topic sentences in mind. You may discover topic sentences that are not always located at the beginning of a paragraph. For example, fiction writers customarily use topic ideas, either expressed or implied, to move readers through their texts. In nonfiction writing, such as popular magazines, topic sentences are often used when the author thinks it is appropriate (based on the audience and the purpose, of course). A single topic sentence might even control the development of a number of paragraphs. For more information on topic sentences, please see Chapter 6 “Writing Paragraphs: Separating Ideas and Shaping Content” .

Developing topic sentences and thinking about their placement in a paragraph will prepare you to write the rest of the paragraph.

The paragraph is the main structural component of an essay as well as other forms of writing. Each paragraph of an essay adds another related main idea to support the writer’s thesis, or controlling idea. Each related main idea is supported and developed with facts, examples, and other details that explain it. By exploring and refining one main idea at a time, writers build a strong case for their thesis.

Paragraph Length

How long should a paragraph be?

One answer to this important question may be “long enough”—long enough for you to address your points and explain your main idea. To grab attention or to present succinct supporting ideas, a paragraph can be fairly short and consist of two to three sentences. A paragraph in a complex essay about some abstract point in philosophy or archaeology can be three-quarters of a page or more in length. As long as the writer maintains close focus on the topic and does not ramble, a long paragraph is acceptable in college-level writing. In general, try to keep the paragraphs longer than one sentence but shorter than one full page of double-spaced text.

Journalistic style often calls for brief two- or three-sentence paragraphs because of how people read the news, both online and in print. Blogs and other online information sources often adopt this paragraphing style, too. Readers often skim the first paragraphs of a great many articles before settling on the handful of stories they want to read in detail.

You may find that a particular paragraph you write may be longer than one that will hold your audience’s interest. In such cases, you should divide the paragraph into two or more shorter paragraphs, adding a topic statement or some kind of transitional word or phrase at the start of the new paragraph. Transition words or phrases show the connection between the two ideas.

In all cases, however, be guided by what you instructor wants and expects to find in your draft. Many instructors will expect you to develop a mature college-level style as you progress through the semester’s assignments.

To build your sense of appropriate paragraph length, use the Internet to find examples of the following items. Copy them into a file, identify your sources, and present them to your instructor with your annotations, or notes.

- A news article written in short paragraphs. Take notes on, or annotate, your selection with your observations about the effect of combining paragraphs that develop the same topic idea. Explain how effective those paragraphs would be.

- A long paragraph from a scholarly work that you identify through an academic search engine. Annotate it with your observations about the author’s paragraphing style.

Starting Your First Draft

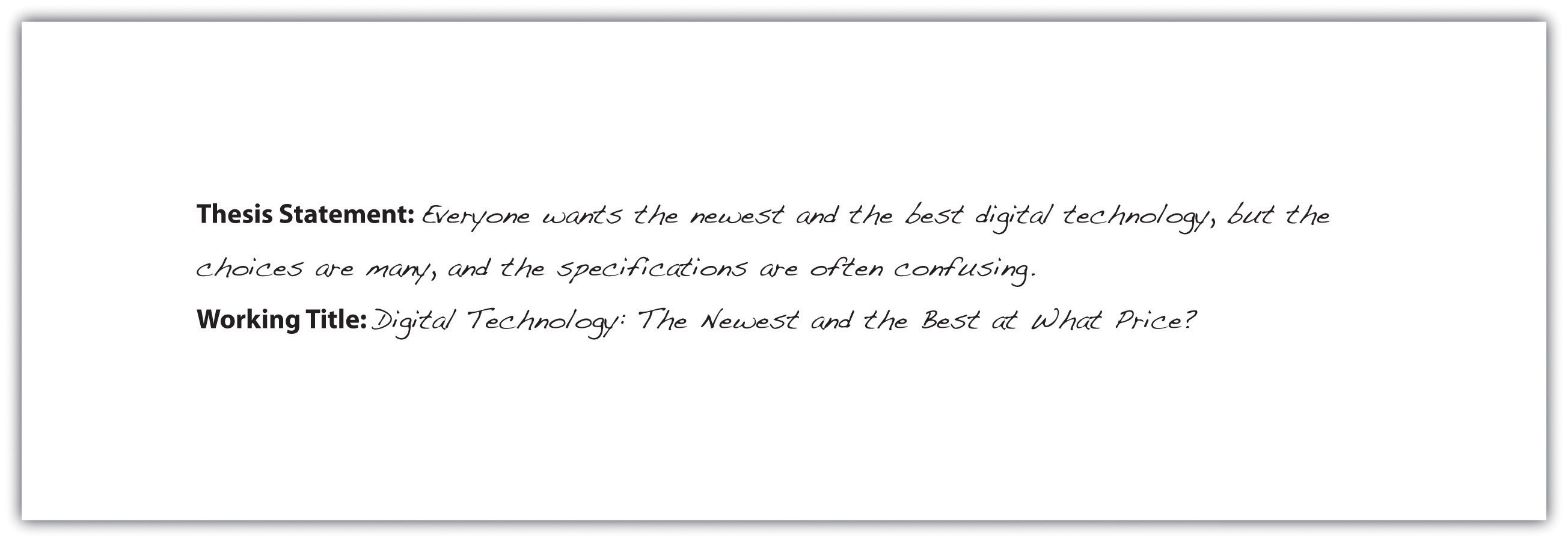

Now we are finally ready to look over Mariah’s shoulder as she begins to write her essay about digital technology and the confusing choices that consumers face. As she does, you should have in front of you your outline, with its thesis statement and topic sentences, and the notes you wrote earlier in this lesson on your purpose and audience. Reviewing these will put both you and Mariah in the proper mind-set to start.

The following is Mariah’s thesis statement.

Here are the notes that Mariah wrote to herself to characterize her purpose and audience.

Mariah chose to begin by writing a quick introduction based on her thesis statement. She knew that she would want to improve her introduction significantly when she revised. Right now, she just wanted to give herself a starting point. You will read her introduction again in Section 8.4 “Revising and Editing” when she revises it.

Remember Mariah’s other options. She could have started directly with any of the body paragraphs.

You will learn more about writing attention-getting introductions and effective conclusions in Chapter 9 “Writing Essays: From Start to Finish” .

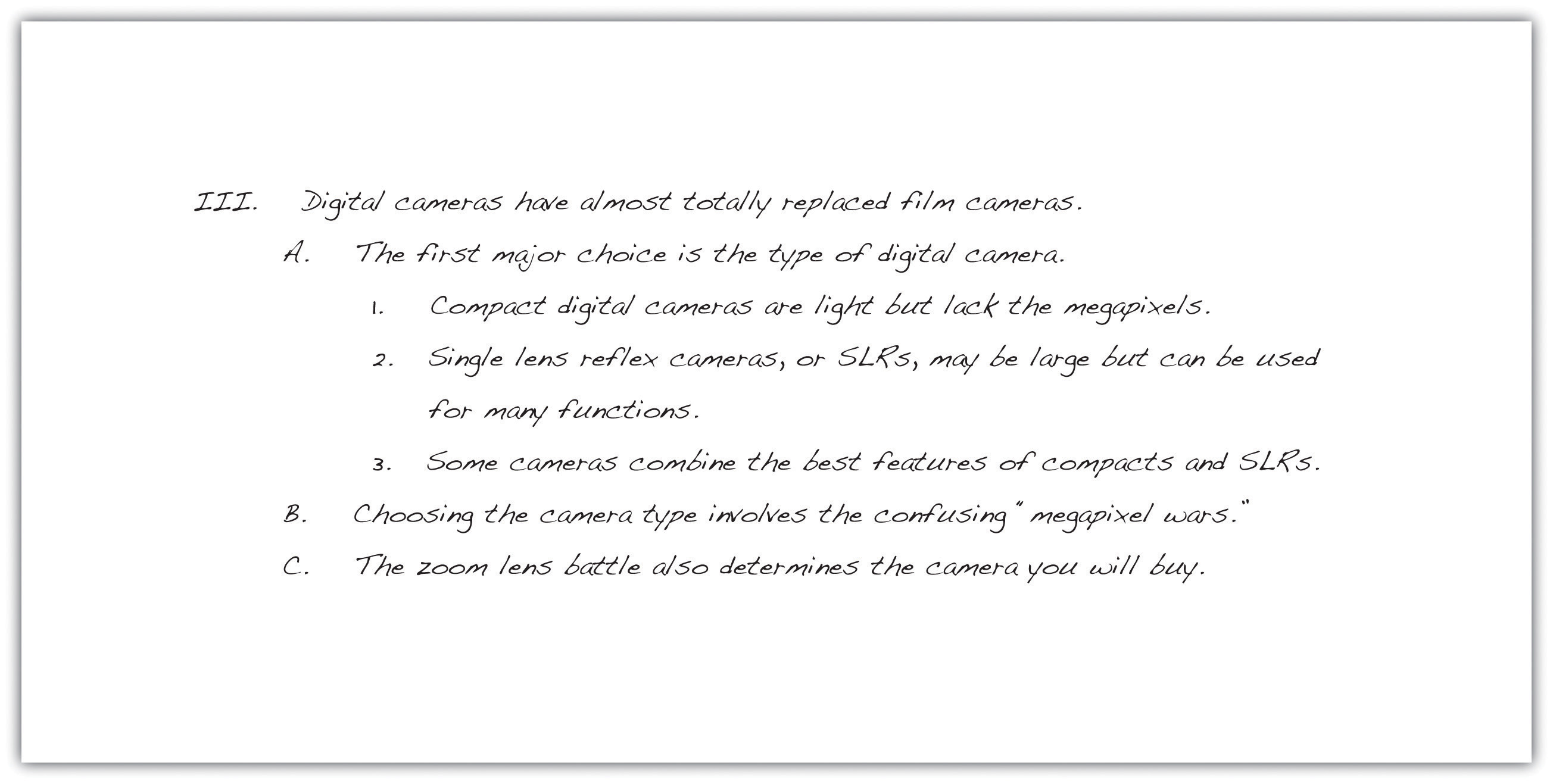

With her thesis statement and her purpose and audience notes in front of her, Mariah then looked at her sentence outline. She chose to use that outline because it includes the topic sentences. The following is the portion of her outline for the first body paragraph. The roman numeral II identifies the topic sentence for the paragraph, capital letters indicate supporting details, and arabic numerals label subpoints.

Mariah then began to expand the ideas in her outline into a paragraph. Notice how the outline helped her guarantee that all her sentences in the body of the paragraph develop the topic sentence.

If you write your first draft on the computer, consider creating a new file folder for each course with a set of subfolders inside the course folders for each assignment you are given. Label the folders clearly with the course names, and label each assignment folder and word processing document with a title that you will easily recognize. The assignment name is a good choice for the document. Then use that subfolder to store all the drafts you create. When you start each new draft, do not just write over the last one. Instead, save the draft with a new tag after the title—draft 1, draft 2, and so on—so that you will have a complete history of drafts in case your instructor wishes you to submit them.

In your documents, observe any formatting requirements—for margins, headers, placement of page numbers, and other layout matters—that your instructor requires.

Study how Mariah made the transition from her sentence outline to her first draft. First, copy her outline onto your own sheet of paper. Leave a few spaces between each part of the outline. Then copy sentences from Mariah’s paragraph to align each sentence with its corresponding entry in her outline.

Continuing the First Draft

Mariah continued writing her essay, moving to the second and third body paragraphs. She had supporting details but no numbered subpoints in her outline, so she had to consult her prewriting notes for specific information to include.

If you decide to take a break between finishing your first body paragraph and starting the next one, do not start writing immediately when you return to your work. Put yourself back in context and in the mood by rereading what you have already written. This is what Mariah did. If she had stopped writing in the middle of writing the paragraph, she could have jotted down some quick notes to herself about what she would write next.

Preceding each body paragraph that Mariah wrote is the appropriate section of her sentence outline. Notice how she expanded roman numeral III from her outline into a first draft of the second body paragraph. As you read, ask yourself how closely she stayed on purpose and how well she paid attention to the needs of her audience.

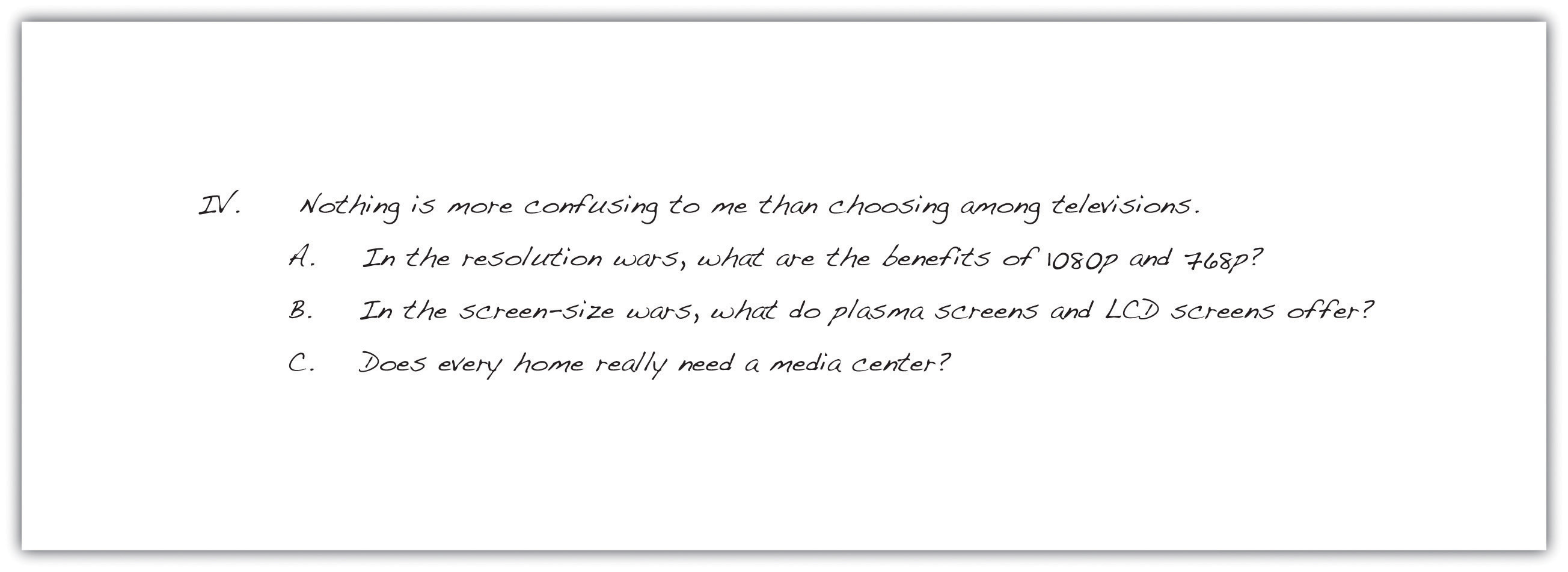

Mariah then began her third and final body paragraph using roman numeral IV from her outline.

Reread body paragraphs two and three of the essay that Mariah is writing. Then answer the questions on your own sheet of paper.

- In body paragraph two, Mariah decided to develop her paragraph as a nonfiction narrative. Do you agree with her decision? Explain. How else could she have chosen to develop the paragraph? Why is that better?

- Compare the writing styles of paragraphs two and three. What evidence do you have that Mariah was getting tired or running out of steam? What advice would you give her? Why?

- Choose one of these two body paragraphs. Write a version of your own that you think better fits Mariah’s audience and purpose.

Writing a Title

A writer’s best choice for a title is one that alludes to the main point of the entire essay. Like the headline in a newspaper or the big, bold title in a magazine, an essay’s title gives the audience a first peek at the content. If readers like the title, they are likely to keep reading.

Following her outline carefully, Mariah crafted each paragraph of her essay. Moving step by step in the writing process, Mariah finished the draft and even included a brief concluding paragraph (you will read her conclusion in Chapter 9 “Writing Essays: From Start to Finish” ). She then decided, as the final touch for her writing session, to add an engaging title.

Writing Your Own First Draft

Now you may begin your own first draft, if you have not already done so. Follow the suggestions and the guidelines presented in this section.

Key Takeaways

- Make the writing process work for you. Use any and all of the strategies that help you move forward in the writing process.

- Always be aware of your purpose for writing and the needs of your audience. Cater to those needs in every sensible way.

- Remember to include all the key structural parts of an essay: a thesis statement that is part of your introductory paragraph, three or more body paragraphs as described in your outline, and a concluding paragraph. Then add an engaging title to draw in readers.

- Write paragraphs of an appropriate length for your writing assignment. Paragraphs in college-level writing can be a page long, as long as they cover the main topics in your outline.

- Use your topic outline or your sentence outline to guide the development of your paragraphs and the elaboration of your ideas. Each main idea, indicated by a roman numeral in your outline, becomes the topic of a new paragraph. Develop it with the supporting details and the subpoints of those details that you included in your outline.

- Generally speaking, write your introduction and conclusion last, after you have fleshed out the body paragraphs.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

How to Write an Essay

Use the links below to jump directly to any section of this guide:

Essay Writing Fundamentals

How to prepare to write an essay, how to edit an essay, how to share and publish your essays, how to get essay writing help, how to find essay writing inspiration, resources for teaching essay writing.

Essays, short prose compositions on a particular theme or topic, are the bread and butter of academic life. You write them in class, for homework, and on standardized tests to show what you know. Unlike other kinds of academic writing (like the research paper) and creative writing (like short stories and poems), essays allow you to develop your original thoughts on a prompt or question. Essays come in many varieties: they can be expository (fleshing out an idea or claim), descriptive, (explaining a person, place, or thing), narrative (relating a personal experience), or persuasive (attempting to win over a reader). This guide is a collection of dozens of links about academic essay writing that we have researched, categorized, and annotated in order to help you improve your essay writing.

Essays are different from other forms of writing; in turn, there are different kinds of essays. This section contains general resources for getting to know the essay and its variants. These resources introduce and define the essay as a genre, and will teach you what to expect from essay-based assessments.

Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab

One of the most trusted academic writing sites, Purdue OWL provides a concise introduction to the four most common types of academic essays.

"The Essay: History and Definition" (ThoughtCo)

This snappy article from ThoughtCo talks about the origins of the essay and different kinds of essays you might be asked to write.

"What Is An Essay?" Video Lecture (Coursera)

The University of California at Irvine's free video lecture, available on Coursera, tells you everything you need to know about the essay.

Wikipedia Article on the "Essay"

Wikipedia's article on the essay is comprehensive, providing both English-language and global perspectives on the essay form. Learn about the essay's history, forms, and styles.

"Understanding College and Academic Writing" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This list of common academic writing assignments (including types of essay prompts) will help you know what to expect from essay-based assessments.

Before you start writing your essay, you need to figure out who you're writing for (audience), what you're writing about (topic/theme), and what you're going to say (argument and thesis). This section contains links to handouts, chapters, videos and more to help you prepare to write an essay.

How to Identify Your Audience

"Audience" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This handout provides questions you can ask yourself to determine the audience for an academic writing assignment. It also suggests strategies for fitting your paper to your intended audience.

"Purpose, Audience, Tone, and Content" (Univ. of Minnesota Libraries)

This extensive book chapter from Writing for Success , available online through Minnesota Libraries Publishing, is followed by exercises to try out your new pre-writing skills.

"Determining Audience" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This guide from a community college's writing center shows you how to know your audience, and how to incorporate that knowledge in your thesis statement.

"Know Your Audience" ( Paper Rater Blog)

This short blog post uses examples to show how implied audiences for essays differ. It reminds you to think of your instructor as an observer, who will know only the information you pass along.

How to Choose a Theme or Topic

"Research Tutorial: Developing Your Topic" (YouTube)

Take a look at this short video tutorial from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to understand the basics of developing a writing topic.

"How to Choose a Paper Topic" (WikiHow)

This simple, step-by-step guide (with pictures!) walks you through choosing a paper topic. It starts with a detailed description of brainstorming and ends with strategies to refine your broad topic.

"How to Read an Assignment: Moving From Assignment to Topic" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Did your teacher give you a prompt or other instructions? This guide helps you understand the relationship between an essay assignment and your essay's topic.

"Guidelines for Choosing a Topic" (CliffsNotes)

This study guide from CliffsNotes both discusses how to choose a topic and makes a useful distinction between "topic" and "thesis."

How to Come Up with an Argument

"Argument" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

Not sure what "argument" means in the context of academic writing? This page from the University of North Carolina is a good place to start.

"The Essay Guide: Finding an Argument" (Study Hub)

This handout explains why it's important to have an argument when beginning your essay, and provides tools to help you choose a viable argument.

"Writing a Thesis and Making an Argument" (University of Iowa)

This page from the University of Iowa's Writing Center contains exercises through which you can develop and refine your argument and thesis statement.

"Developing a Thesis" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This page from Harvard's Writing Center collates some helpful dos and don'ts of argumentative writing, from steps in constructing a thesis to avoiding vague and confrontational thesis statements.

"Suggestions for Developing Argumentative Essays" (Berkeley Student Learning Center)

This page offers concrete suggestions for each stage of the essay writing process, from topic selection to drafting and editing.

How to Outline your Essay

"Outlines" (Univ. of North Carolina at Chapel Hill via YouTube)

This short video tutorial from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill shows how to group your ideas into paragraphs or sections to begin the outlining process.

"Essay Outline" (Univ. of Washington Tacoma)

This two-page handout by a university professor simply defines the parts of an essay and then organizes them into an example outline.

"Types of Outlines and Samples" (Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab)

Purdue OWL gives examples of diverse outline strategies on this page, including the alphanumeric, full sentence, and decimal styles.

"Outlining" (Harvard College Writing Center)

Once you have an argument, according to this handout, there are only three steps in the outline process: generalizing, ordering, and putting it all together. Then you're ready to write!

"Writing Essays" (Plymouth Univ.)

This packet, part of Plymouth University's Learning Development series, contains descriptions and diagrams relating to the outlining process.

"How to Write A Good Argumentative Essay: Logical Structure" (Criticalthinkingtutorials.com via YouTube)

This longer video tutorial gives an overview of how to structure your essay in order to support your argument or thesis. It is part of a longer course on academic writing hosted on Udemy.

Now that you've chosen and refined your topic and created an outline, use these resources to complete the writing process. Most essays contain introductions (which articulate your thesis statement), body paragraphs, and conclusions. Transitions facilitate the flow from one paragraph to the next so that support for your thesis builds throughout the essay. Sources and citations show where you got the evidence to support your thesis, which ensures that you avoid plagiarism.

How to Write an Introduction

"Introductions" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page identifies the role of the introduction in any successful paper, suggests strategies for writing introductions, and warns against less effective introductions.

"How to Write A Good Introduction" (Michigan State Writing Center)

Beginning with the most common missteps in writing introductions, this guide condenses the essentials of introduction composition into seven points.

"The Introductory Paragraph" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post from academic advisor and college enrollment counselor Grace Fleming focuses on ways to grab your reader's attention at the beginning of your essay.

"Introductions and Conclusions" (Univ. of Toronto)

This guide from the University of Toronto gives advice that applies to writing both introductions and conclusions, including dos and don'ts.

"How to Write Better Essays: No One Does Introductions Properly" ( The Guardian )

This news article interviews UK professors on student essay writing; they point to introductions as the area that needs the most improvement.

How to Write a Thesis Statement

"Writing an Effective Thesis Statement" (YouTube)

This short, simple video tutorial from a college composition instructor at Tulsa Community College explains what a thesis statement is and what it does.

"Thesis Statement: Four Steps to a Great Essay" (YouTube)

This fantastic tutorial walks you through drafting a thesis, using an essay prompt on Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter as an example.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement" (WikiHow)

This step-by-step guide (with pictures!) walks you through coming up with, writing, and editing a thesis statement. It invites you think of your statement as a "working thesis" that can change.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement" (Univ. of Indiana Bloomington)

Ask yourself the questions on this page, part of Indiana Bloomington's Writing Tutorial Services, when you're writing and refining your thesis statement.

"Writing Tips: Thesis Statements" (Univ. of Illinois Center for Writing Studies)

This page gives plentiful examples of good to great thesis statements, and offers questions to ask yourself when formulating a thesis statement.

How to Write Body Paragraphs

"Body Paragraph" (Brightstorm)

This module of a free online course introduces you to the components of a body paragraph. These include the topic sentence, information, evidence, and analysis.

"Strong Body Paragraphs" (Washington Univ.)

This handout from Washington's Writing and Research Center offers in-depth descriptions of the parts of a successful body paragraph.

"Guide to Paragraph Structure" (Deakin Univ.)

This handout is notable for color-coding example body paragraphs to help you identify the functions various sentences perform.

"Writing Body Paragraphs" (Univ. of Minnesota Libraries)

The exercises in this section of Writing for Success will help you practice writing good body paragraphs. It includes guidance on selecting primary support for your thesis.

"The Writing Process—Body Paragraphs" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

The information and exercises on this page will familiarize you with outlining and writing body paragraphs, and includes links to more information on topic sentences and transitions.

"The Five-Paragraph Essay" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post discusses body paragraphs in the context of one of the most common academic essay types in secondary schools.

How to Use Transitions

"Transitions" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill explains what a transition is, and how to know if you need to improve your transitions.

"Using Transitions Effectively" (Washington Univ.)

This handout defines transitions, offers tips for using them, and contains a useful list of common transitional words and phrases grouped by function.

"Transitions" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

This page compares paragraphs without transitions to paragraphs with transitions, and in doing so shows how important these connective words and phrases are.

"Transitions in Academic Essays" (Scribbr)

This page lists four techniques that will help you make sure your reader follows your train of thought, including grouping similar information and using transition words.

"Transitions" (El Paso Community College)

This handout shows example transitions within paragraphs for context, and explains how transitions improve your essay's flow and voice.

"Make Your Paragraphs Flow to Improve Writing" (ThoughtCo)

This blog post, another from academic advisor and college enrollment counselor Grace Fleming, talks about transitions and other strategies to improve your essay's overall flow.

"Transition Words" (smartwords.org)

This handy word bank will help you find transition words when you're feeling stuck. It's grouped by the transition's function, whether that is to show agreement, opposition, condition, or consequence.

How to Write a Conclusion

"Parts of An Essay: Conclusions" (Brightstorm)

This module of a free online course explains how to conclude an academic essay. It suggests thinking about the "3Rs": return to hook, restate your thesis, and relate to the reader.

"Essay Conclusions" (Univ. of Maryland University College)

This overview of the academic essay conclusion contains helpful examples and links to further resources for writing good conclusions.

"How to End An Essay" (WikiHow)

This step-by-step guide (with pictures!) by an English Ph.D. walks you through writing a conclusion, from brainstorming to ending with a flourish.

"Ending the Essay: Conclusions" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This page collates useful strategies for writing an effective conclusion, and reminds you to "close the discussion without closing it off" to further conversation.

How to Include Sources and Citations

"Research and Citation Resources" (Purdue OWL Online Writing Lab)

Purdue OWL streamlines information about the three most common referencing styles (MLA, Chicago, and APA) and provides examples of how to cite different resources in each system.

EasyBib: Free Bibliography Generator

This online tool allows you to input information about your source and automatically generate citations in any style. Be sure to select your resource type before clicking the "cite it" button.

CitationMachine

Like EasyBib, this online tool allows you to input information about your source and automatically generate citations in any style.

Modern Language Association Handbook (MLA)

Here, you'll find the definitive and up-to-date record of MLA referencing rules. Order through the link above, or check to see if your library has a copy.

Chicago Manual of Style

Here, you'll find the definitive and up-to-date record of Chicago referencing rules. You can take a look at the table of contents, then choose to subscribe or start a free trial.

How to Avoid Plagiarism

"What is Plagiarism?" (plagiarism.org)

This nonprofit website contains numerous resources for identifying and avoiding plagiarism, and reminds you that even common activities like copying images from another website to your own site may constitute plagiarism.

"Plagiarism" (University of Oxford)

This interactive page from the University of Oxford helps you check for plagiarism in your work, making it clear how to avoid citing another person's work without full acknowledgement.

"Avoiding Plagiarism" (MIT Comparative Media Studies)

This quick guide explains what plagiarism is, what its consequences are, and how to avoid it. It starts by defining three words—quotation, paraphrase, and summary—that all constitute citation.

"Harvard Guide to Using Sources" (Harvard Extension School)

This comprehensive website from Harvard brings together articles, videos, and handouts about referencing, citation, and plagiarism.

Grammarly contains tons of helpful grammar and writing resources, including a free tool to automatically scan your essay to check for close affinities to published work.

Noplag is another popular online tool that automatically scans your essay to check for signs of plagiarism. Simply copy and paste your essay into the box and click "start checking."

Once you've written your essay, you'll want to edit (improve content), proofread (check for spelling and grammar mistakes), and finalize your work until you're ready to hand it in. This section brings together tips and resources for navigating the editing process.

"Writing a First Draft" (Academic Help)

This is an introduction to the drafting process from the site Academic Help, with tips for getting your ideas on paper before editing begins.

"Editing and Proofreading" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page provides general strategies for revising your writing. They've intentionally left seven errors in the handout, to give you practice in spotting them.

"How to Proofread Effectively" (ThoughtCo)

This article from ThoughtCo, along with those linked at the bottom, help describe common mistakes to check for when proofreading.

"7 Simple Edits That Make Your Writing 100% More Powerful" (SmartBlogger)

This blog post emphasizes the importance of powerful, concise language, and reminds you that even your personal writing heroes create clunky first drafts.

"Editing Tips for Effective Writing" (Univ. of Pennsylvania)

On this page from Penn's International Relations department, you'll find tips for effective prose, errors to watch out for, and reminders about formatting.

"Editing the Essay" (Harvard College Writing Center)

This article, the first of two parts, gives you applicable strategies for the editing process. It suggests reading your essay aloud, removing any jargon, and being unafraid to remove even "dazzling" sentences that don't belong.

"Guide to Editing and Proofreading" (Oxford Learning Institute)

This handout from Oxford covers the basics of editing and proofreading, and reminds you that neither task should be rushed.

In addition to plagiarism-checkers, Grammarly has a plug-in for your web browser that checks your writing for common mistakes.

After you've prepared, written, and edited your essay, you might want to share it outside the classroom. This section alerts you to print and web opportunities to share your essays with the wider world, from online writing communities and blogs to published journals geared toward young writers.

Sharing Your Essays Online

Go Teen Writers

Go Teen Writers is an online community for writers aged 13 - 19. It was founded by Stephanie Morrill, an author of contemporary young adult novels.

Tumblr is a blogging website where you can share your writing and interact with other writers online. It's easy to add photos, links, audio, and video components.

Writersky provides an online platform for publishing and reading other youth writers' work. Its current content is mostly devoted to fiction.

Publishing Your Essays Online

This teen literary journal publishes in print, on the web, and (more frequently), on a blog. It is committed to ensuring that "teens see their authentic experience reflected on its pages."

The Matador Review

This youth writing platform celebrates "alternative," unconventional writing. The link above will take you directly to the site's "submissions" page.

Teen Ink has a website, monthly newsprint magazine, and quarterly poetry magazine promoting the work of young writers.

The largest online reading platform, Wattpad enables you to publish your work and read others' work. Its inline commenting feature allows you to share thoughts as you read along.

Publishing Your Essays in Print

Canvas Teen Literary Journal

This quarterly literary magazine is published for young writers by young writers. They accept many kinds of writing, including essays.

The Claremont Review

This biannual international magazine, first published in 1992, publishes poetry, essays, and short stories from writers aged 13 - 19.

Skipping Stones

This young writers magazine, founded in 1988, celebrates themes relating to ecological and cultural diversity. It publishes poems, photos, articles, and stories.

The Telling Room

This nonprofit writing center based in Maine publishes children's work on their website and in book form. The link above directs you to the site's submissions page.

Essay Contests

Scholastic Arts and Writing Awards

This prestigious international writing contest for students in grades 7 - 12 has been committed to "supporting the future of creativity since 1923."

Society of Professional Journalists High School Essay Contest

An annual essay contest on the theme of journalism and media, the Society of Professional Journalists High School Essay Contest awards scholarships up to $1,000.

National YoungArts Foundation

Here, you'll find information on a government-sponsored writing competition for writers aged 15 - 18. The foundation welcomes submissions of creative nonfiction, novels, scripts, poetry, short story and spoken word.

Signet Classics Student Scholarship Essay Contest

With prompts on a different literary work each year, this competition from Signet Classics awards college scholarships up to $1,000.

"The Ultimate Guide to High School Essay Contests" (CollegeVine)

See this handy guide from CollegeVine for a list of more competitions you can enter with your academic essay, from the National Council of Teachers of English Achievement Awards to the National High School Essay Contest by the U.S. Institute of Peace.

Whether you're struggling to write academic essays or you think you're a pro, there are workshops and online tools that can help you become an even better writer. Even the most seasoned writers encounter writer's block, so be proactive and look through our curated list of resources to combat this common frustration.

Online Essay-writing Classes and Workshops

"Getting Started with Essay Writing" (Coursera)

Coursera offers lots of free, high-quality online classes taught by college professors. Here's one example, taught by instructors from the University of California Irvine.

"Writing and English" (Brightstorm)

Brightstorm's free video lectures are easy to navigate by topic. This unit on the parts of an essay features content on the essay hook, thesis, supporting evidence, and more.

"How to Write an Essay" (EdX)

EdX is another open online university course website with several two- to five-week courses on the essay. This one is geared toward English language learners.

Writer's Digest University

This renowned writers' website offers online workshops and interactive tutorials. The courses offered cover everything from how to get started through how to get published.

Writing.com

Signing up for this online writer's community gives you access to helpful resources as well as an international community of writers.

How to Overcome Writer's Block

"Symptoms and Cures for Writer's Block" (Purdue OWL)

Purdue OWL offers a list of signs you might have writer's block, along with ways to overcome it. Consider trying out some "invention strategies" or ways to curb writing anxiety.

"Overcoming Writer's Block: Three Tips" ( The Guardian )

These tips, geared toward academic writing specifically, are practical and effective. The authors advocate setting realistic goals, creating dedicated writing time, and participating in social writing.

"Writing Tips: Strategies for Overcoming Writer's Block" (Univ. of Illinois)

This page from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign's Center for Writing Studies acquaints you with strategies that do and do not work to overcome writer's block.

"Writer's Block" (Univ. of Toronto)

Ask yourself the questions on this page; if the answer is "yes," try out some of the article's strategies. Each question is accompanied by at least two possible solutions.

If you have essays to write but are short on ideas, this section's links to prompts, example student essays, and celebrated essays by professional writers might help. You'll find writing prompts from a variety of sources, student essays to inspire you, and a number of essay writing collections.

Essay Writing Prompts

"50 Argumentative Essay Topics" (ThoughtCo)

Take a look at this list and the others ThoughtCo has curated for different kinds of essays. As the author notes, "a number of these topics are controversial and that's the point."

"401 Prompts for Argumentative Writing" ( New York Times )

This list (and the linked lists to persuasive and narrative writing prompts), besides being impressive in length, is put together by actual high school English teachers.

"SAT Sample Essay Prompts" (College Board)

If you're a student in the U.S., your classroom essay prompts are likely modeled on the prompts in U.S. college entrance exams. Take a look at these official examples from the SAT.

"Popular College Application Essay Topics" (Princeton Review)

This page from the Princeton Review dissects recent Common Application essay topics and discusses strategies for answering them.

Example Student Essays

"501 Writing Prompts" (DePaul Univ.)

This nearly 200-page packet, compiled by the LearningExpress Skill Builder in Focus Writing Team, is stuffed with writing prompts, example essays, and commentary.

"Topics in English" (Kibin)

Kibin is a for-pay essay help website, but its example essays (organized by topic) are available for free. You'll find essays on everything from A Christmas Carol to perseverance.

"Student Writing Models" (Thoughtful Learning)

Thoughtful Learning, a website that offers a variety of teaching materials, provides sample student essays on various topics and organizes them by grade level.

"Five-Paragraph Essay" (ThoughtCo)

In this blog post by a former professor of English and rhetoric, ThoughtCo brings together examples of five-paragraph essays and commentary on the form.

The Best Essay Writing Collections

The Best American Essays of the Century by Joyce Carol Oates (Amazon)

This collection of American essays spanning the twentieth century was compiled by award winning author and Princeton professor Joyce Carol Oates.

The Best American Essays 2017 by Leslie Jamison (Amazon)

Leslie Jamison, the celebrated author of essay collection The Empathy Exams , collects recent, high-profile essays into a single volume.

The Art of the Personal Essay by Phillip Lopate (Amazon)

Documentary writer Phillip Lopate curates this historical overview of the personal essay's development, from the classical era to the present.

The White Album by Joan Didion (Amazon)

This seminal essay collection was authored by one of the most acclaimed personal essayists of all time, American journalist Joan Didion.

Consider the Lobster by David Foster Wallace (Amazon)

Read this famous essay collection by David Foster Wallace, who is known for his experimentation with the essay form. He pushed the boundaries of personal essay, reportage, and political polemic.

"50 Successful Harvard Application Essays" (Staff of the The Harvard Crimson )

If you're looking for examples of exceptional college application essays, this volume from Harvard's daily student newspaper is one of the best collections on the market.

Are you an instructor looking for the best resources for teaching essay writing? This section contains resources for developing in-class activities and student homework assignments. You'll find content from both well-known university writing centers and online writing labs.

Essay Writing Classroom Activities for Students

"In-class Writing Exercises" (Univ. of North Carolina Writing Center)

This page lists exercises related to brainstorming, organizing, drafting, and revising. It also contains suggestions for how to implement the suggested exercises.

"Teaching with Writing" (Univ. of Minnesota Center for Writing)

Instructions and encouragement for using "freewriting," one-minute papers, logbooks, and other write-to-learn activities in the classroom can be found here.

"Writing Worksheets" (Berkeley Student Learning Center)

Berkeley offers this bank of writing worksheets to use in class. They are nested under headings for "Prewriting," "Revision," "Research Papers" and more.

"Using Sources and Avoiding Plagiarism" (DePaul University)

Use these activities and worksheets from DePaul's Teaching Commons when instructing students on proper academic citation practices.

Essay Writing Homework Activities for Students

"Grammar and Punctuation Exercises" (Aims Online Writing Lab)

These five interactive online activities allow students to practice editing and proofreading. They'll hone their skills in correcting comma splices and run-ons, identifying fragments, using correct pronoun agreement, and comma usage.

"Student Interactives" (Read Write Think)

Read Write Think hosts interactive tools, games, and videos for developing writing skills. They can practice organizing and summarizing, writing poetry, and developing lines of inquiry and analysis.

This free website offers writing and grammar activities for all grade levels. The lessons are designed to be used both for large classes and smaller groups.

"Writing Activities and Lessons for Every Grade" (Education World)

Education World's page on writing activities and lessons links you to more free, online resources for learning how to "W.R.I.T.E.": write, revise, inform, think, and edit.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1917 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,425 quotes across 1917 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

Need something? Request a new guide .

How can we improve? Share feedback .

LitCharts is hiring!

4b. Drafting

Drafting is the point in the writing process at which you compose a complete first version of an essay. There are as many ways to write a first draft as there are essays in the world. Some academic writers begin their drafts with body paragraphs and work backwards to their introduction while others feel the need to develop a solid introduction before launching into the body of the essay. The best advice offered by most professional writers is to try not to worry too much about how unprepared, disorganized, repetitive, or uninspired a first draft might feel because relatively few of us can sit down and compose an entire essay (or even email) that is ready to be published in a single draft. As students, it can be easy to overlook the fact that the books and articles we read for class have been revised and edited many times and with the support of many people prior to publication. Your instructors will expect you to perform the role of both writer and editor before turning in your final draft.

As you dive into the drafting stage of the writing process, the following advice may come in handy when you are facing the pressure of deadlines and grades:

Begin with the part of your essay you know the most about or feel least nervous about.

- Having an outline allows you to start with the third, fifth, or second paragraph of an essay without worrying how it will flow with the rest. Your initial paragraphs may vary in length or contain insufficient reasoning or evidence as you draft. Topic sentences, transitions, and other details can be cleaned up later. Be sure to cite sources even if you’re unsure what quotation or other evidence you might include to reduce your formatting time later (and help you avoid unintentional plagiarism).

Just do it!

- Hesitation can be a writer’s worst enemy. Facing a blank page can feel like a climbing to the top of a diving platform and being too wary to jump or being unable to choose a restaurant for dinner. Although every good writer should be self-critical at times, try to remember that a first draft can be terrible and still be very useful. Try not to look back or doubt your ideas – there will be time for that later. Treat your drafting sessions like freewriting and do not worry about transitions, spelling, punctuation, and other mechanics.

Leave yourself a short note or comment at the end of each writing session .

- Every writer has picked up something they wrote a day or week ago and wondered what the heck they were thinking. Take an extra minute at the end of a writing session to leave yourself a short note or comment to remind yourself where you hope to pick up or anything you need to look up. Notes and comments can also be useful if you feel a sentence in your paragraph may be tangential or incomplete and you want to come back to it later.

Pace yourself and take breaks .

- Essays take time to develop. Hopefully, you can find a place to write where you are comfortable and able to avoid distractions. Turn off your phone and try not to have an internet browser open unless citing evidence.

Be reasonable with your goals .

- Begin each writing session by taking a moment to consider how long you plan to write and what you hope to accomplish. Plan breaks to stretch and rehydrate. Holding yourself to a goal for each session will help you stay on track toward your deadlines and give you a sense of achievement. Rewarding yourself after each successful writing session can be useful motivation as well.

Keep your audience, purpose, and task requirements in mind .

- By the time we get several paragraphs or hours into a writing task, we can become so attached to our own ideas and writing style that we lose track of our audience and purpose. Asking yourself “who will be reading this essay?” and “how will it be assessed?” or “what is my overall purpose?” can help you keep an eye on the big picture. Checking assignment guidelines will help guide your work and help you ensure that your draft meets an instructor or editor’s expectations.

The Value of First Drafts

A first draft is a complete version of a piece of writing, but it is certainly not expected to be the final version. During the revision stage, you will have the opportunity to make all kinds of changes to your first draft before you put the final touches on it during the editing stage. A first draft gives you a complete working version of an essay that is ready to share with peers, writing coaches, instructors, and/or editors that can be improved with revision and editing.

Writing as Inquiry Copyright © 2021 by Kara Clevinger and Stephen Rust is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Skip to main content

- Skip to ChatBot Assistant

- Academic Writing

- Research Writing

- Critical Reading and Writing

- Punctuation

- Writing Exercises

- ELL/ESL Resources

Building the Essay Draft

Building a strong essay draft requires going through a logical progression of stages:, explanation.

Development options

Linking paragraphs

Introductions

Conclusions.

Revising and proofreading the draft

Hints for revising and proofreading

Tip: After you have completed the body of your paper, you can decide what you want to say in your introduction and in your conclusion.

Once you know what you want to talk about and you have written your thesis statement, you are ready to build the body of your essay.

The thesis statement will usually be followed by

- the body of the paper

- the paragraphs that develop the thesis by explaining your ideas by backing them up

- examples or evidence

Tip: The "examples or evidence" stage is the most important part of the paper, because you are giving your reader a clear idea of what you think and why you think it.

Development Options

- For each reason you have to support your thesis, remember to state your point clearly and explain it.

Tip: Read your thesis sentence over and ask yourself what questions a reader might ask about it. Then answer those questions, explaining and giving examples or evidence.

Show how one thing is similar to another, and then how the two are different, emphasizing the side that seems more important to you. For example, if your thesis states, "Jazz is a serious art form," you might compare and contrast a jazz composition to a classical one.

Show your reader what the opposition thinks (reasons why some people do not agree with your thesis), and then refute those reasons (show why they are wrong). On the other hand, if you feel that the opposition isn't entirely wrong, you may say so, (concede), but then explain why your thesis is still the right opinion.

- Think about the order in which you have made your points. Why have you presented a certain reason that develops your thesis first, another second? If you can't see any particular value in presenting your points in the order you have, reconsider it until you either decide why the order you have is best, or change it to one that makes more sense to you.

- Does each paragraph develop my thesis?

- Have I done all the development I wish had been done?

- Am I still satisfied with my working thesis, or have I developed my body in ways that mean I must adjust my thesis to fit what I have learned, what I believe, and what I have actually discussed?

Linking Paragraphs

It is important to link your paragraphs together, giving your readers cues so that they see the relationship between one idea and the next, and how these ideas develop your thesis.

Your goal is a smooth transition from paragraph A to paragraph B, which explains why cue words that link paragraphs are often called "transitions."

Tip: Your link between paragraphs may not be one word, but several, or even a whole sentence.

Here are some ways of linking paragraphs:

- To show simply that another idea is coming, use words such as "also," "moreover," or "in addition."

- To show that the next idea is the logical result of the previous one, use words such as "therefore," "consequently," "thus," or "as a result."

- To show that the next idea seems to go against the previous one, or is not its logical result, use words such as "however," "nevertheless," or "still."

- To show you've come to your strongest point, use words such as "most importantly."

- To show you've come to a change in topic, use words such as "on the other hand."

- To show you've come to your final point, use words such as "finally."

After you have come up with a thesis and developed it in the body of your paper, you can decide how to introduce your ideas to your reader.

The goals of an introduction are to

- Get your reader's attention/arouse your reader's curiosity.

- Provide any necessary background information before you state your thesis (often the last sentence of the introductory paragraph).

- Establish why you are writing the paper.

Tip: You already know why you are writing, and who your reader is; now present that reason for writing to that reader.

Hints for writing your introduction:

- Use the Ws of journalism (who, what, when, where, why) to decide what information to give. (Remember that a history teacher doesn't need to be told "George Washington was the first president of the United States." Keep your reader in mind.)

- Add another "W": Why (why is this paper worth reading)? The answer could be that your topic is new, controversial, or very important.

- Catch your reader by surprise by starting with a description or narrative that doesn't hint at what your thesis will be. For example, a paper could start, "It is less than a 32nd of an inch long, but it can kill an adult human," to begin a paper about eliminating malaria-carrying mosquitoes.

There can be many different conclusions to the same paper (just as there can be many introductions), depending on who your readers are and where you want to direct them (follow-up you expect of them after they finish your paper). Therefore, restating your thesis and summarizing the main points of your body should not be all that your conclusion does. In fact, most weak conclusions are merely restatements of the thesis and summaries of the body without guiding the reader toward thinking about the implications of the thesis.

Here are some options for writing a strong conclusion:

Make a prediction about the future. You convinced the reader that thermal energy is terrific, but do you think it will become the standard energy source? When?

Give specific advice. If your readers now understand that multicultural education has great advantages, or disadvantages, or both, whatever your opinion might be, what should they do? Whom should they contact?

Put your topic in a larger context. Once you have proven that physical education should be part of every school's curriculum, perhaps readers should consider other "frill" courses which are actually essential.

Tip: Just as a conclusion should not be just a restatement of your thesis and summary of your body, it also should not be an entirely new topic, a door opened that you barely lead your reader through and leave them there lost. Just as in finding your topic and in forming your thesis, the safe and sane rule in writing a conclusion is this: neither too little nor too much.

Revising and Proofreading the Draft

Writing is only half the job of writing..

The writing process begins even before you put pen to paper, when you think about your topic. And, once you finish actually writing, the process continues. What you have written is not the finished essay, but a first draft, and you must go over many times to improve it--a second draft, a third draft, and so on until you have as many as necessary to do the job right. Your final draft, edited and proofread, is your essay, ready for your reader's eyes.

A revision is a "re-vision" of your essay--how you see things now, deciding whether your introduction, thesis, body, and conclusion really express your own vision. Revision is global, taking another look at what ideas you have included in your paper and how they are arranged.

Proofreading

Proofreading is checking over a draft to make sure that everything is complete and correct as far as spelling, grammar, sentence structure, punctuation, and other such matters go. It's a necessary, if somewhat tedious and tricky, job one that a friend or computer Spellcheck can help you perform. Proofreading is polishing, one spot at a time.

Tip: Revision should come before proofreading: why polish what you might be changing anyway?

Hints for revising and proofreading:

- Leave some time--an hour, a day, several day--between writing and revising. You need some distance to switch from writer to editor, some distance between your initial vision and your re-vision.

- Double-check your writing assignment to be sure you haven't gone off course . It is all right if you've shifted from your original plan, if you know why and are happier with this direction. Make sure that you are actually following your mentor's assignment.

- Read aloud slowly . You need to get your eye and your ear to work together. At any point that something seems awkward, read it over again. If you're not sure what's wrong--or even if something is wrong--make a notation in the margin and come back to it later. Watch out for "padding;" tighten your sentences to eliminate excess words that dilute your ideas.

- Be on the lookout for points that seem vague or incomplete ; these could present opportunities for rethinking, clarifying, and further developing an idea.

- Get to know what your particular quirks are as a writer. Do you give examples without explaining them, or forget links between paragraphs? Leave time for an extra rereading to look for any weak points.

- Get someone else into the act. Have others read your draft, or read it to them. Invite questions and ask questions yourself, to see if your points are clear and well-developed. Remember, though, that some well-meaning readers can be too easy (or too hard) on a piece of writing.

Tip: Never change anything unless you are convinced that it should be changed .

- Keep tools at hand, such as a dictionary, a thesaurus, and a writing handbook.

- While you're using word processing, remember that computers are wonderful resources for editing and revising.

- When you feel you've done everything you can, first by revising and then by proofreading, and have a nice clean, final draft, put it aside and return later to re-see the whole essay. There may be some last minute fine-tuning that can make all the difference.

Don't forget--if you would like help with at this point in your assignment or any other type of writing assignment, learning coaches are available to assist you. Please contact Academic Support by emailing [email protected] ; calling 1-800-847-3000, ext 3008; or calling the main number of the location in your region (click here for more information) to schedule an appointment.

Need Assistance?

If you would like assistance with any type of writing assignment, learning coaches are available to assist you. Please contact Academic Support by emailing [email protected].

Questions or feedback about SUNY Empire's Writing Support?

Contact us at [email protected] .

Smart Cookies

They're not just in our classes – they help power our website. Cookies and similar tools allow us to better understand the experience of our visitors. By continuing to use this website, you consent to SUNY Empire State University's usage of cookies and similar technologies in accordance with the university's Privacy Notice and Cookies Policy .

- Peterborough

Drafting the English Essay

- Creating an outline

- The use of "I" (first-person)

- Historical present

- Drafting body paragraphs

- The introduction

- The conclusion

Creating an Outline

Making an outline before you start to write has the same advantage as writing down your thesis as soon as you have one. It forces you to think about the best possible order for what you want to say and to think through your line of thought before you have to write sentences and paragraphs.

Remember that an essay and its outline do not have to be structured into five paragraphs. Think about major points, sections or parts of your essay, rather than paragraphs. The number of sections you have will depend on what you have to say and how you think your thesis needs to be supported. It is possible to structure an essay around two major points, each divided into sub-points. Or you may structure an essay around four, five or six points, depending on the essay's length. An essay under 1500 words may fall naturally into three sections, but let the number come from what you have to say rather than striving for the magic three.

Creating an outline also helps you avoid the temptation of organizing your essay by following the plot line of the text you are writing about and simply retelling the story with a few of your own comments thrown in. If you conscientiously make an outline that is ordered to best support your thesis, which is there in print before your eyes, your essay’s organization will be based on supporting your argument not on the text’s plotline.

Read more on organizing your essay

Writing the Draft

If you have followed good essay-writing practice, which includes developing a narrowed topic and analytical thesis, reading closely and taking careful notes, and creating an organized outline, you will find that writing your essay is much less difficult than if you simply sit down and plunge in with a vague topic in mind.

Always keep your reader in mind when you write. Work to convince this reader that your argument is valid and has merit. To do this, you must write clearly. The best writing is the product of drafting and revising.

As you write your rough draft, your ideas will develop, so it is helpful to accept the messy process of drafting. Review your sections as you write, but leave most of the revision for when you have a completed first draft. When you revise, you can refine your ideas by making your language more specific and direct, by developing your explanation of a quotation, and by explaining the connections between your ideas. Remember that your goal is clear expression; use a formal tone, avoid slang and colloquial terms, and be precise in your language.

Stylistic Notes for Writing the English Essay

The use of "i".

The judicious use of "I" in English essays is generally accepted. (You may run into a professor who doesn't want you to and says so, and, in that case, don't). The key is to not to overuse "I". When writing your draft, you may find it helpful to get your thoughts flowing by writing "I think that..." but when you revise, you will find that those three words can be eliminated from the sentences they begin.

For example:

I think that these poems also share a rather detached, unemotional, matter-of-fact acceptance of death.

Revised: These poems share a rather detached, unemotional, matter-of-fact acceptance of death.

I think death, dying, and the moments that precede dying preoccupy Dickinson.

Revised: Death, dying, and the moments the precede dying preoccupy Dickinson.

The Historical Present

Instructors generally agree that students should use the the present tense, which is known as the historical present, when describing events in a work of literature (or a film) or when discussing what authors or scholars say about a topic or issue, even when the work of literature is from the past or uses the past tense itself, or the authors and scholars are dead.

Examples of historical present:

In A Midsummer Night’s Dream , Bottom is a uniformly comedic figure.

Kyi argues that “democracy is the political system through which an empowerment of the people occurs.”

It is considered more accurate to use the present tense in these circumstances because the arguments put forward by scholars, and the characters presented and scenes depicted by novelists, poets, and dramatists continue to live in the present whenever anyone reads them. An added benefit is that many find the use of the historical present tense makes for a more lively style and a stronger voice.

Drafting Body Paragraphs

The body of the essay will be made up of the claims or points you are making, supported by evidence from the primary source, the work in question, and perhaps some secondary sources. Your supporting evidence may be quotations of words or phrases from the text, as well as details about character, setting, plot, syntax, diction, images and anything else you have found in the work that is relevant to your argument.

Writing successful paragraphs

You may find yourself quoting often, and that is fine. The words from the text are, after all, the support for the argument you are making, and they show that your ideas came from somewhere and are grounded in the text. But try to keep your quotations as short and pertinent as possible. Use quotations effectively to support your interpretation or arguments; be sure to explain the quotation: what does it illustrates and how?

Effectively integrating evidence

Make sure you don't use or quote words whose definition or meaning you are not sure about. As a student of English literature, you should make regular use of a good dictionary; many academics recommend the Oxford English Dictionary . Not knowing what a word means or misunderstanding how it is used can undermine a whole argument. When you read and write about authors from previous centuries, you will often have to familiarize yourself with new words. To write good English essays, you must take the time to do this.

Sample Body Paragraph

This body paragraph is a sample only. Its content is not to be reproduced in whole or part. Use of the ideas or words in this essay is an act of plagiarism, which is subject to academic integrity policy at Trent University and other academic institutions.

“Because I could not stop for Death” describes the process of dying right up to and past the moment of death, in the first person. This process is described symbolically. The speaker, walking along the road of life is picked up and given a carriage ride out of town to her destination, the graveyard and death. The speaker, looking back, says that she “could not stop for Death – / [so] He kindly stopped for” her (1-2). Dickinson personifies death as a “kindly” (2) masculine being with “civility” (6). As the two “slowly dr[i]ve” (5) down the road of life, the speaker observes life in its simplicity: the “School,” (9), “the Fields of Gazing Grain” (11), and the “Setting Sun” (12), and realizes that this road out of town is the road out of life. The road’s ending at “a House that seemed / A Swelling of the Ground” (17-18) is a life’s ending at death, “Eternity” (24). Once in the House that is the speaker’s grave, that is, after death, the speaker remains conscious. Her death is not experienced as a loss of consciousness, a sleep or oblivion. Her sense of time does change though:

Since then – 'tis Centuries – and yet Feels shorter than the Day I first surmised the Horses' Heads Were toward Eternity – (20-24)

It has become difficult for the speaker to tell the difference between a century and a day. But she knows it has been “Centuries” since then, so the implication is that her consciousness has lived on in an eternal afterlife.

What works in the sample paragraph?

- The topic sentence makes a clear claim that the rest of the paragraph develops through details, quotations and analysis.

- The quotation is followed by the writer’s analysis of the quoted words and argument about their implication. This is the best way to use textual evidence.

The Introduction

Often, the introduction is the hardest part to write. Here you make your first impression, introduce the topic, provide background information, define key terms perhaps, and, most important, present your thesis, upon which the entire essay hangs. Many people find it easiest to write the introduction last or to write a very rough introduction that they change significantly once the draft is complete.

Strategies for writing the introduction

Sample Introduction

This introductory paragraph is a sample only. Its content is not to be reproduced in whole or part. Use of the ideas or words in this essay is an act of plagiarism, which is subject to academic integrity policy at Trent University and other academic institutions.

Emily Dickinson was captivated by the riddle of death, and several of her poems deal with it in different ways. There are many poems that describe, in the first person, the process of dying right up to and including the moment of death, often recalled from a vantage point after death in some sort of afterlife. As well, several poems speculate more generally about what lies beyond the visible world our senses perceive in life. This essay examines four of Dickinson’s poems that are about dying and death and one that is more speculative. Two are straightforwardly about dying, while the other two present dying symbolically, but taken together they show many similarities. Death is experienced matter-of-factly and without fear and with a full consciousness that registers details and describes them clearly. All the poems examined hint at an afterlife which is not described in traditionally Christian terms but which is not contradictory to Christian belief either. Yet death remains a riddle. While one poem may emphasize an afterlife of peace, silence and anchors at rest, others only hint at an ongoing consciousness, and one both asserts that something beyond life exists while also saying that belief is really only a narcotic that cannot completely still the pain of doubt. Dying, the moment of death, and what comes after preoccupy Dickinson: in these poems, death and eternity both “beckon” and “baffle” (Dickinson, “This World is not Conclusion” 5).

What works in this sample introduction?

- This essay has a good, narrowed, focused topic.