- Write with us

- Advertise with us

- Liability Disclaimer

Primary Ka Master ● Com - प्राइमरी का मास्टर ● कॉम

एक छतरी के नीचे 'प्राइमरी का मास्टर' की समस्त ऑनलाइन सेवाएँ

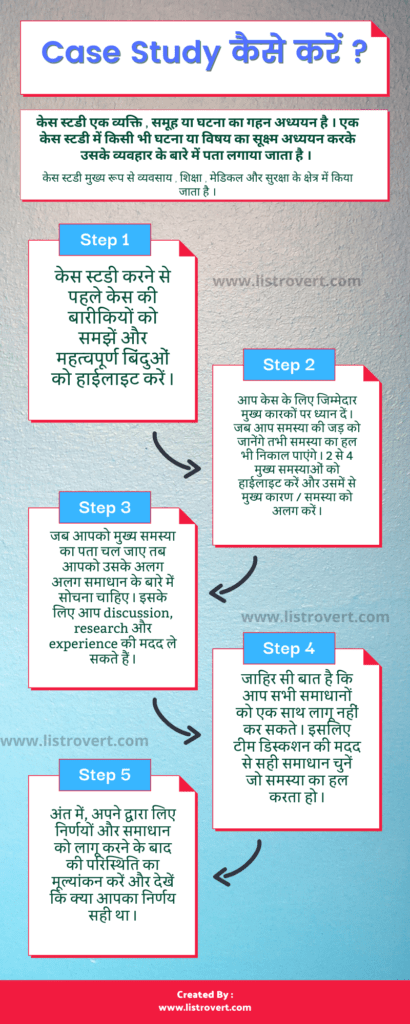

केस स्टडी विधि के उद्देश्य, विशेषताएं और इस विधि की उपयोगितायेँ

- विद्यार्थी स्वतंत्र होकर, स्वयं ही सृजनात्मक ढंग से समस्या पर विचार कर सकेंगें।

- वे समस्या समाधान ( Problem based learning )तक पहुंचने में सक्रिय हो सकेंगें।

- वे अपने पूर्व ज्ञान का प्रयोग करते हुए प्रमाणों को संग्रह कर सकेंगें।

- घटनाक्रम में नवीन तथ्यों को जान सकेंगे।

- स्वयं अपने अनुभव से सीखते हुए ज्ञान प्राप्त कर सकेंगें।

- व्यक्तिगत, सामाजिक संबंधों को उत्तम ढंग से स्थापित कर सकेंगे।

- छात्रों में अभिप्रेरण एवं अभिव्यक्ति की क्षमता में वृद्धि हो सकेगी।

- छात्रों की उपलब्धियों का मूल्यांकन हो सकेगा।

व्यक्तिगत अध्ययन छात्रों को एक सार्थक ज्ञान प्रदान करता है जिसका प्रयोग विभिन्न प्रकार के समाधान या अध्ययन के लिए किया जाता है। यह एक जटिल अधिगम का स्वरूप होता है। इसमें सृजनात्मक चिन्तन निहित होता है और चिन्तन स्तर पर शिक्षण की व्यवस्था होती है।

Post a Comment

Case of study child ka farmet kaise taiyar krein

- Skip to navigation

- Skip to main content

Children With Special Needs

For Students:

The audiobooks for visually impaired and ISL Dictionary for hearing impaired have been put up on DIKSHA platform. In addition, the National Institute of Open Schooling is committed to make its website accessible to people with disabilities. In its effort to make the website accessible, NIOS has incorporated different features which will make it easier for users to browse the website.

Some of the accessibility features incorporated in the website includes adjusting the display settings, ease of navigation, content readability and so on. Following are the accessibility features incorporated in this website:

- Alternate description for Images & Audio/Video

- Display settings

- Ease of navigation

- Content readability & structure

- Keyboard support

Visually Impaired Learners

- Study material has been developed in Digitally Accessible Information System (DAISY), a technical standard for digital audiobooks, periodicals and computerized text.

- Learners can access all study material of NIOS through DAISY

- An Indian Sign Language (ISL) Dictionary has been developed to facilitate communication and education of the deaf and hard-of-hearing learners.

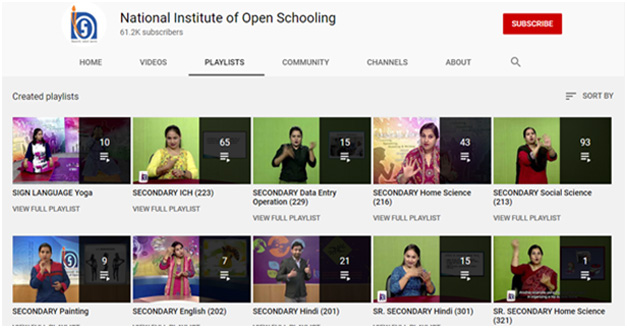

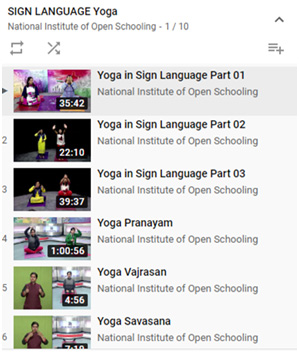

- NIOS has also developed more than 270 Video in Sign Language in 7 subjects to provide educational access to learners at secondary level and Yoga course.

- Accessibility in School Curriculum-NCERT’s Initiatives can be found here https://ciet.nic.in/pages.php?id=accesstoedu&ln=en&ln=en

Hearing Impaired Learners

- Course content (Selected ones) of NIOS has also been recorded in sign language which is placed on NIOS website as well as on YouTube.

- These videos are available at https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCXBn5q8Zv4Bz-LZXWWD7Jxw/playlists

- The recorded content is sent to HI learners on DVD

Innovative Material developed by NCERT

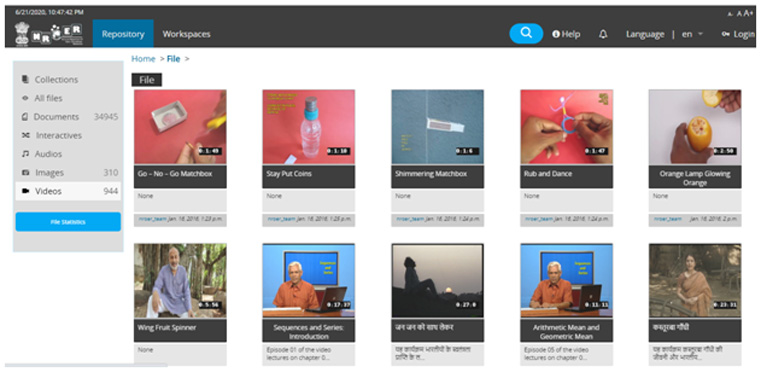

Various steps are being taken to bring children with special needs (CwSN) to schools such as the National Council of Educational Research & Training (NCERT) has developed exemplar material for providing low cost quality home education to students with severe disabilities through e-learning. NCERT text books have been converted into digital books which can be downloaded free by any one, any time. Most of the books are in UNICODE which a child with special needs can read using a Text-to-Speech (TTS)/Software/mobile app though e-Pathshaala mobile app. For visually challenged learners e-book in DAISY format and tactile maps have been developed.

Promoting Inclusive Education in the Foundational Years - Barkha: A Reading Series for ‘All’

The department has developed Barkha: A Reading Series for ‘All’ as an exemplary, inclusive learning material in the form of a supplementary early reading series. This reading series is available in print and digital formats. Its design is based on the principles of inclusion and the concept of Universal Design for Learning (UDL). Barkha: A Reading Series for ‘All’ is exemplary in demonstrating how the principles of UDL can guide the design of inclusive features like tactile and high resolution visuals, text in accessible scripts etc. This exemplar provides a direction and initial guidelines for developing similarly accessible material in the form of textbooks and other learning resources for all school stages.

In tandem with the Digital India Campaign, the department has also developed a digital version of Barkha: A Reading Series for ‘All’. This digital version retains all the inclusive features of the print version and is unique in its functionality because it allows for greater flexibility and has greater scope of appealing to all. Children can access all 40 story booklets through a single device. This also gives them space to revisit any book whenever and wherever they like. The privacy that is afforded by being able to read on one’s own computer or tablet allows one to read comfortably and at one’s own pace therefore promoting reading in a non-threatening environment with meaning and pleasure. An introduction to each story is available in audio-video format both in sign and regular language forms. It helps to introduce sign language as a regular form of communication at an early age to all children in an inclusive setting. The digital version of this reading series is available on NCERT website and the epathshala portal.

Sample Content:

https://nroer.gov.in/home/e-library

https://repository.seshagun.nic.in/video/support-to-children-with-special-needs-cwsn-through-special-resource-centre

This site is designed, developed, hosted and maintained by National Informatics Centre (NIC), Department of Electronics & Information Technology, Ministry of Communications & Information Technology, GoI. Contents provided by Ministry of Human Resource Development, GoI.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Sage Choice

The discovery of autism: Indian parents’ experiences of caring for their child with an autism spectrum disorder

The current study investigated the lived experience of 12 parents of children with an Autism Spectrum Disorder in everyday cultural contexts in Goa, India. Narratives from parents collected between 2009 and 2010 were analyzed using the procedures of phenomenological psychology. Four temporal phases of parents’ experience emerged from these data. Findings showed that the earliest phase of the child’s life was a period of relative normalcy and social cohesion. In the second phase, the child’s behaviors began to disrupt the everyday social order, but parents viewed these unexpected behaviors as temporary. In the third phase, parents’ observations in public situations, along with assessments of others, led to a qualitative shift in which parents began to perceive that there was a persisting problem interfering with their child’s social and practical activities. In the fourth phase, parents grappled with developing their child’s capacities to meet existing practical opportunities in the local society, while attempting to reshape the social world to accommodate the abilities and limits of children like their own. Parents’ fundamental concerns throughout their journey were: learning to meet new and unfamiliar challenges as parents, caring for their child’s basic needs, and finding an engaging niche with a sense of belonging for their child in the everyday milieu. Both culture-specific and potentially universal levels of experience are delineated in the overall findings. Implications for culturally sensitive research and practice in India and other low- and middle-income countries are discussed.

Since Kanner (1943) first identified a group of children with “autistic disturbances of affective contact” in the United States (1943, p. 217), classic autism and the broader group autism spectrum disorders (ASD) have been formally adopted by various professional diagnostic systems (e.g., Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000 ]; International Classification of Diseases [ICD-10; World Health Organization, 1992]). These diagnostic constructs have since “traveled around the globe,” as evidenced by the existence of national organizations for autism in over 80 countries ( Daley, 2002 , p. 532). With respect to India in particular, knowledge of Western psychiatry and psychology first arrived with British colonialism ( Daley, 2004 ). A “child showing schizophrenic behavior” was first mentioned in 1959 ( Batliwalla, 1959 , p. 251), and autism-specific research has substantially increased since then ( Daley, 2004 ). Sustained professional focus on autism began in the late 1980s and 1990s ( Krishnamurthy, 2008 ), and autism is now widely recognized in medical, political, and legal circles in India ( Daley, 2004 ; Daley & Sigman, 2002 ). The current study contributes to the extant literature by providing an in-depth, qualitative investigation of parenting a child with ASD in the Indian state of Goa.

Kleinman (1977) suggested that “ideal” cross-cultural studies begin with “local phenomenological descriptions” (1977, p. 4). Instead of presupposing the nature of psychopathology from a culturally distant perspective, local descriptions are required to provide an understanding of it in cultural contexts. Knowledge of local perspectives has helped strengthen community-based care and improve outcomes for individuals experiencing significant psychological distress (e.g., Chatterjee et al., 2008 ). In the case of autism, evidence from countries such as the USA ( Altiere & von Kluge, 2009 ), Israel ( Shaked, 2005 ), the UK ( Avdi, Griffin, & Brough, 2000b ), and Australia ( Gray, 1993 , 1995 , 2001 ), for instance, has shown that parent perspectives often differ from traditional scientific/professional ones and frequently invoke spiritual, moral, or personal interpretations. Because parents have been shown to find meaning by using nonmedical or nonprofessional interpretive frameworks and regularly turn to alternative treatments for ASD, an investigation of what matters to parents on an everyday level in other cultures is also necessary. In line with this general trend of exploring indigenous viewpoints, professional organizations such as the American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force on Evidence-Based Practice (2006) have recently stated that an understanding of patients’ culture, preferences, values, and worldview is an integral part of evidence-based practice in psychology (EBPP).

In India, little research has sought to examine parents’ indigenous viewpoints of their children diagnosed with ASD. The available literature has suggested that children with ASD often do present families with considerable challenges requiring external support ( Daley, 2004 ; Gupta & Singhal, 2005 ; Kishore & Basu, 2011 ; Krishnamurthy, 2008 ; Malhotra, Chakrabarti, Gupta, & Gill, 2004 ). Daley’s (2004) research in particular offered several insights into Indian parents’ perspectives on ASD. For instance, Daley found that Indian parents’ initial symptom recognition in children who were eventually diagnosed with ASD was at a range of 6 to 10 months later than families in the West. Potential reasons given for the extra time in India prior to help-seeking included local cultural beliefs like “boys speak late,” which perhaps normalized early unusual behaviors. Overall, the initial symptoms most reported were social difficulties, suggesting that a child’s ability to relate to others is of high import to parents in India. More recent research in India on parental perceptions of intellectual disabilities has also noted diverse frames of reference featuring sociocultural, spiritual, and biomedical components ( Edwardraj, Mumtaj, Prasad, Kuruvilla, & Jacob, 2010 ).

The extant literature provides some knowledge of the influence of Indian cultural beliefs and social norms on the local responses to ASD. However, more information is needed on parents’ indigenous viewpoints, prior to theoretical conceptualizations like symptoms and diagnosis. Parents may not initially be using these latter constructs to understand and describe their child, so it is important to examine the full meaning of their original perspectives and how these may change over time. In addition, research conducted in a different Indian location than previous research, with both urban and rural populations, may allow for knowledge of how parenting concerns and practices may be common or different across various settings (see Grinker, 2007 ). The phenomenological approach was utilized in order to freshly access and concretely describe the parents’ lived experiences of their child with sensitivity to local context and meaning. The research was embedded in a larger project on ASD in India (Autism Research and Training Initiative: ARTI) based at a community-based, nongovernmental organization (NGO) and child development center located in Goa, India.

The study was conducted in the Indian state of Goa. Goa differs from other parts of India given its Portuguese colonial heritage and relatively high educational and economic development. The state has a population of 1.4 million and is characterized by geographical, cultural, and religious diversity. The most commonly spoken language is Konkani, but Marathi, English, and Hindi are also used. The overall Autism Research and Training Initiative (ARTI) project investigated several domain areas related to ASD in India, including help-seeking patterns and family impact. The current study focused on parents’ experiences of and with their child from birth to the present time. Formal Institutional Review Board approval was granted by Sangath Centre and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine prior to the study.

Participants

Parents were recruited via key informants at special schools, child development centers, and health clinics. Primary inclusion criteria were parents with a child who was already identified as meeting criteria for ASD. Diagnoses had been given by pediatricians, local clinical psychologists, and special educators using standard DSM-based criteria.

The sample for the present study consisted of 12 parents of 10 children: one father and seven mothers were interviewed alone (i.e., eight parents of children with ASD); and two sets of parents, mother and father, were interviewed together (i.e., four parents of children with ASD). The sample size was consistent with standards for phenomenological research ( Giorgi, 2009 ; Starks & Trinidad, 2007 ). The participants were deliberately selected to reflect key differences in the local population, such as religious and geographical background. Table 1 displays information on these demographic characteristics and others including family type (nuclear/joint). Joint families are those with more than one “immediate” family living in one household and often include additional extended family members.

Participant demographics

Data collection

The data for the study were comprised of in-depth interviews ( Davidson, 2003 ; Giorgi, 2009 ; Kvale, 2008 ) conducted by members of ARTI between June 2009 and August 2010. Interview staff consisted of one doctoral-, two master’s-, and three bachelor-level personnel, conducting interviews in teams of two (one interviewer, one note-taker). All interviewers were trained and supervised by doctoral-level senior researchers with extensive experience in qualitative research. Interviews were completed in various settings, such as participants’ homes, child clinics, and special schools. The team made every effort to accommodate participants’ location preferences. For example, some parents preferred the school setting and time because they could participate in the research while waiting for their child, whereas others preferred the more familiar home environment. Interviews in formal settings such as schools were conducted in private rooms to minimize distractions and increase comfort. All participants gave consent for interviews and a separate consent for audio recording. Participants were assured that their participation was voluntary and confidential.

Each interview was conducted in the language of the participants’ preference (Konkani, Marathi, English, or Hindi) and lasted 1–3 hours, with later follow-up questions as needed. The present study utilized a semistructured interview guide, which elicited in-depth narratives from parents of life with the child from birth to the present (see Appendix). Interviewers remained flexible and open to topics introduced by participants, who guided the researcher through their particular narratives of parenting a child identified as ASD. Key events explored were: birth and early experiences with the child; parents’ first notice of behavioral differences; and interactions with family members, healthcare providers, educators, and community members in relation to their child. Throughout the process, completed interviews were examined by senior researchers to monitor the data quality and to provide feedback to the interviewers.

Data analysis

The tape-recorded interviews were transcribed into electronic format. Konkani, Marathi, or Hindi interviews were translated directly into English by research members fluent in both languages. Redundancy that offered no added meaning was removed. Additional words were added by researchers only to assure readability. The participants’ expressions were then ordered according to the original temporal sequence of the life situations they described. The analysis of the data was informed by the methods of phenomenological psychology, which were used to elucidate the essential meanings of the parents’ lived experiences of their child ( Davidson, 2003 ; Giorgi, 2009 ; Wertz, 1983 , 2005 , 2010 ). In addition, empirical trends in the data, such as the relative frequency of important parental experiences and the chronological ages of children, were noted and summarized when possible. The presentation in this report includes both phenomenological findings, (i.e., the essential structure and constituent meanings of parents’ experiences) and the empirical findings (accounts of related factual trends evident in the data). Analytic rigor was ensured via internal reviews by expert members of the research team. In the resulting presentation, participants have been de-identified. Narratives have been identified by the notation of M(other) and/or F(ather) with accompanying participant number (see Table 1 ).

The following sections describe parents’ lived experiences with their child, with reference to context, meaning, and life historical unfolding. The findings indicate a series of temporal structures. Four main temporal phases emerged from the data and are described in what follows. It was not possible to list the exact chronological duration of each because there were no definite boundaries between them. The age of the child when each phase began also varied considerably between parents, and some parents had not entered the latter phases.

In each of the four phases, the following three constituents were essential to parents in caring for their child: (a) Engaging in an open-ended process of parenting by learning to meet new and unfamiliar challenges; (b) Ensuring that the child’s basic needs are met; and (c) Finding an engaging niche with a sense of belonging for their child in the everyday milieu including social relationships, education/work, maintaining family values, etc. These aspects of parenting were present in the earliest period and continued to develop in later ones as described in what follows.

Beginning the parenting journey: Reciprocal routines, budding care networks, and an open future

In the earliest period after the child’s birth, parents happily welcomed the newborn and embarked upon the journey of care by attempting to develop harmonious, synergistic routines. Most parents identified this early period as joyful and honored the child with pride.

When he was born there was a huge celebration and a lot of excitement (M10). My daughter was so very cute and very good looking and on seeing her I forgot everything. All the negativity in me, it went away on seeing her (M1). It was like picture postcard. He won about three “Healthy Baby Contests” (M6).

The immediacy and novelty of their new life with their son or daughter was predominately positive:

Her first birthday actually I took time off (M1). We celebrated in a very big way (F1). We called relatives and it was a big party and … We took photographs (M1).

The child’s behaviors were expected, ordinary, and normal. Although parenting was an inexact science, parents gained sufficient know-how to respond to their child. Caring practices were informed by prior experiences of parenting, advice from extended family, and basic learning-by-doing, trial-and-error approaches. Parents did not extensively contemplate the long-term future; however, the baby’s future was given with open possibilities.

“Autism” and troublesome behaviors beyond the scope of routine parenting had yet to appear. If significant medical problems of the child appeared, courses of action were clear, such as taking the child to a doctor for excessive vomiting. In essence, their child’s medical issues were problem-solving situations in a world that was familiar to them. The anticipation was that solutions provided by doctors would enable the family to return to normal routines. Although ASD had yet to emerge, the caregiving skills and social networks that parents were now developing would later become essential resources when disruptive and unexplainable behaviors began to appear. For instance, the child’s early medical problems led parents to form relationships with physicians and extended family as allies in childcare. The nature and quality of these early social networks shaped the course that parents’ care efforts eventually took with regard to the child’s later behavioral problems. Two parents (M5, M10) recounted their child’s numerous early medical problems, which required extensive travel for specialized healthcare. One parent described her village as “a place where you don’t even have access to good doctors.” She was greatly dissatisfied with the lack of available local support and thus grew accustomed to traveling afar for better care. Both M5 and M10 experienced professionals as generally insensitive to the family’s situation, leaving an early negative impression that would later color expectations of various service providers when, with the appearance of ASD, the quality of relationships with service providers became a crucial issue.

Interruptions from the path: Child’s unexpected, incongruent, but seemingly temporary behaviors

Various unexpected behaviors of the child caught parents’ attention due to their disruption of the social cohesion of everyday life. These behaviors were incongruent with those of older siblings or same-aged children and parents’ own underlying views of expected childhood behavior. Other family members, however, normalized the incongruence by mentioning similar patterns in family history or cultural norms, for instance, concerning the typical age of speech onset (e.g., “your husband also used to also speak late”; “sometimes Jeep Zodh aasa [the tongue is thick]”). In this way, the discrepancies were ordinary and integrated into the prior experiential phase of parenting. Further examples of these behaviors of the child included: (a) Trouble falling asleep (M1); (b) Agitation in a restaurant during a family vacation with parents’ work colleagues (M6); (c) Crying continuously without stopping, and the parent not knowing why (M4); (d) Not sitting (F3, M10); (e) Flapping hands (M10); and (f) Crying so softly that it resembled a “cat’s meow” (M5).

The child’s unexpected, discrepant behaviors began affecting the everyday parent–child relationship, leading some parents to ponder their own caregiving efforts. However, some also noted adaptive aspects of the unexpected behaviors. For instance, one parent (M4) could not soothe her child’s crying, and two others (M1, F1) were surprised that their child did not seem very attached to them. In the first case, the parent could not understand why her soothing efforts weren’t working; however, in the second case, the parent felt that her daughter’s detached manner was actually a “blessing in disguise” because the child didn’t seem to miss her when the mother had to leave the house.

But one thing it was a bit strange that she didn’t seem to miss me very much sometimes. (M1) Not that she used to dislike her or anything like that. (F1) But that I took as a blessing in disguise. I thought that it’s good that she is not missing me. She was quite happy with her nanny and my mother-in-law. (M1)

In the parents’ understanding, these discrepant behaviors were not indicative of a larger or ongoing issue but instead were temporary. Although some parents began to doubt, their friends and family comforted them with reassurances that the child’s atypical behavior was just part of the ordinary process of child growth. Parents described that:

Nobody thought that there was anything amiss. (M6) At 8 months I was comparing him to other children, and I felt they used to do a lot more, but it still didn’t … cross my mind that there is problem. (M10)

Even as parents’ perspectives on their child became increasingly divergent from reassuring others, they continued to believe that the disruptions would eventually pass. The parents continued to anticipate a process of change that would lead to their child occupying a familiar place in adult society. The more distant future remained open and potentially limitless.

When the term “autism” was introduced early in this phase, its meaning for parents remained relatively empty and without significant implications. Parents may have heard the word but did not apply it to their child due to a lack of familiarity or because their child seemed to function well in most areas of life.

That first time when we were told autism, we had taken it carelessly. We had never heard about it. (F2) And he was okay in other things (M2). His only problem was that he was not communicating. He was not communicating but other things he was doing. He used to understand us if we told him anything. (F2)

“Autism” was relatively unknown. Perhaps it applied to others, but it was inconsequential with regard to their own child, because challenging behaviors were isolated, transient, and did not hold meaning concerning the child as a whole with implications for the future.

Roadblocks along the way: Child’s continued growth in question, and parents’ search for solutions

When behaviors began to be seen as different from other children and as socially problematic beyond the immediate family, parents sensed that they were persisting and potentially dangerous for the child. One parent stated:

He used to throw this and that, he used to remove and throw a burning stick from the chula [open flame cooking stove], he would touch the hot iron, he would dip his hand in boiling tea, he used to throw the milk out. Sometimes we would starve and [lose] sleep for this reason. (M7)

The most alarming and transformative events that initiated the third phase involved unexpected and intrusive communication from other concerned persons. One parent (M10), for example, was verbally accosted by a doctor for “poor parenting” after the parent brought her son to the doctor for his flu-like symptoms. The doctor admonished the mother for not recognizing the implications of the child’s speaking, sitting, and walking difficulties, after which she began elaborating their significance for the future.

The way he disclosed it to me, it came as a total shock to me because he said, “Oh my God, he will be a vegetable for the rest of his life. What kind of mother are you, you don’t know how to take care of a child?” … I just did not know what to do. I was just totally in a state of shock. (M10)

Although parents became concerned about the child’s fate and eventual place in adult society, the long-term future was still a distant, though increasingly uncertain, horizon. Parents were concerned with the possibility that their son’s or daughter’s ways of being may preclude their capacity for self-care, social relationships, and education. Consequently, the behaviors identified by teachers and administrators at schools engendered the most concern among parents. Parents had viewed education as the gateway towards a brighter future in which their children would gradually overcome relative dependence on them. However, these growing questions threw that expectation into uncertainty. Though the parents were increasingly concerned, hopes still remained that the child’s problems would subside. One father, a cattle herdsman, recounted taking pleasure in positive gains after earlier concerns about his son’s performance in school:

Now if I go to give fodder to the cow, he goes first and gives them. He comes and mixes all fodder and gives them. He knows everything. Now he says that he wants two cows, one red and one black. So it feels good. (F3)

Before this phase, the children were seen as proceeding along a typical pace. However, when the child began entering the outside world, perspectives of normality/abnormality from medicine or media came to the fore. In other words, this phase was when “autism” began to take on determinate meaning for parents in reference to their own child. Comparisons with other children and experts’ views introduced the meaning of a persisting problem with implications for important areas of life (education, relationships), but their total implications for the future were not yet elaborated in concrete ways. Allopathic and alternative healers were consulted, including an Ayurvedic doctor who determined that a “nerve is getting choked up somewhere” (M4) and a baba (religious man) who concluded there was “a shraap [curse] and [a] need to perform a Ganesh aarti [religious service]” (M9).

Some parents continued to hold on to dreams such as the arrival of a medical advancement or cure, the hope of a desirable job in government for the child, or the wish of the child becoming an “Einstein” or “Beethoven.” These connotations of scientific/musical genius did not necessarily match parents’ own observations of the child but were consistent with other meanings of the diagnosis learned from media and professionals. A concurrent manuscript (Divan, Vajaratkar, Desai, Strik-Lievers, & Patel, in press) discusses parents’ interactions with professionals in more detail.

Here, but not yet there: Addressing the present while looking towards the future

In this phase, the parents’ aim was to accept their child’s limited capacities, to expand them as much as is possible in relation to the given social realities, and to attempt to change those social realities so that they would become more welcoming for their child. It should be noted that not every parent in our study had fully reached this phase, such as the rural father who still assumed his child would be given a government job. The children in this phase were usually nearing their teenage years. The meaning of age here reflects normative parental beliefs about what the child should be doing at their current age with regard to learning, communicating, socializing, and so forth. As one parent discussed, when it became certain through persistent observations that her child was not performing in the classroom like his peers, it finally “dawned” on her that the child was not going to become a “typical” adult. Previous doubts concerning the child’s abilities have here become certainties. In this phase, parents began to give up the expectation that their child would reach the hoped for self-care, social, or vocational capacities of other adults.

Parents accepted and owned their child’s limitations as a consequence of seeing that their child remained different from other children in situations essential for becoming a fully functioning adult in the local setting. In this way, the label “autism” was filled in with meanings with implications for the child’s whole life—past and future. Parents were learning more about professional or scientific knowledge related to autism, and their own understandings of their child often changed as a result. For example, parents started to retrospectively reinterpret earlier perceptions as indicative of symptoms of ASD, and some reported their own indigenous care efforts to be consistent with professional therapy for autism.

Whenever we were in the restaurant, he used to get agitated. That was probably the first sign of socialization problem. (M6) She was content to be with herself. That’s probably one of the red flags but at that time you do not realize; you do not know anything about autism. (M1) In my intuition I taught her everything I could. And I was kind of doing ABA [applied behavior analysis] with her (M1). I did not know the term but I was doing ABA with her. She was looking outside the window and I was holding her head and literally turning her head; I was forcing her to make eye contact. (F1)

Even when the concept of autism was accepted as applicable to their child, most parents also attributed their child’s unusual differences to multiple, alternative, and often conflicting external causes, but remained unsure as to any final solution. Some general trends of explanation included: (a) genetics or chemical exposure (M1, a PhD scientist); (b) potential links to other children in the family with developmental issues, e.g., a “spastic” relative (M6); (c) mother not taking required medications while pregnant, or taking too many medications (F3, M10); and (d) stressful experiences during or after pregnancy.

As the children aged, parents came to assume a previously unexpected role as the one ultimately responsible for their son’s or daughter’s everyday needs. But what about the future? All parents in this fourth temporal phase deeply worried about what would happen to their child when the parents “are no longer,” that is, when the parents could no longer care for their children. One parent advocated for a social scale security system in India, whereas another worried:

Later on … who’ll take care [of him]? … He is independent but not independent enough to go out and all. (M5)

A major concern for parents became discovering their son’s and daughter’s place in the world and finding ways to help them occupy it. Some parents attempted to organize activities and find creative outlets where their child would belong and have an enjoyable present and future. One mother noted:

I don’t have expectations but I just want him to live a happy life. Enjoy every moment that we enjoy with him. Every moment of his has to be enjoyable and I don’t want any pressure on my son. (M5)

Parents also sought to maintain values and traditions like religion, spirituality, and art.

First he used to not mix with other children, but now he likes to play with them … He acted as Krishna [Hindu god] for his school program. That time he wore Krishna’s costume like mukut [crown], murli [flute]. (M7)

Given the difficulties of finding or establishing an alternative social milieu, patience became a virtue for many parents as they waited for their children to learn basic life skills, albeit in their own way: “I think we have to keep our patience. You can rush things with other kids but not with her. She will learn in due course” (M1). Another parent poignantly described: “He should be able to lead his own life; [he] should be able to write his own name, we don’t want him to be great but at least that much he should do” (M4).

Although “autism” took on a certain reality with implications for both the past and future, it is not necessarily a fully determinate fate or destiny, for open questions remain about what the child ultimately can become, what the parent can do, and how social realities can be changed to be more welcoming and accommodating to their sons and daughters.

This study conducted in Goa, India, has limits of generalizability because all participants had at least some contact with the health or educational system. The findings indicated that parents’ experiences of caring for their child with ASD involved three main constituents, which emerged through four temporal phases: learning to meet new and unfamiliar challenges as parents; caring for their child’s basic needs; and finding an engaging niche with a sense of belonging for their child in the everyday milieu. The four temporal phases were: Phase 1, a period of celebration and social cohesion; Phase 2, though parents began to perceive their child’s behaviors as incongruent with expected behaviors, the discrepancies were understood as temporary and viewed by family members as within the bounds of ordinary childhood behavior; Phase 3, parents’ observations in public situations, along with assessments by others, led to a qualitative shift in which parents began to perceive a persisting problem interfering with practical and social activities; and Phase 4, parents recognized that these persisting behavioral problems rendered the child’s future place in the social world uncertain. Parents grappled with developing their child’s capacities to meet existing practical opportunities in the local society, while attempting to reshape the social world to accommodate the abilities and limits of children like their own. With regard to diagnostic conceptualizations, neither “autism,” nor any conception of a “developmental disorder” was present in Phase 1, and in Phase 2, parents disregarded the autism diagnosis as they focused on what they perceived to be temporary deficits in functioning (e.g., poor communication). “Autism” took on meaning for parents beginning in Phase 3, as indicating persisting problems in social and educational settings, but future implications were not fully experienced until Phase 4.

The present study is consistent with other literature on ASD and developmental disabilities in India and elsewhere and extends its findings to Goa. Research has noted that family members explain early deficits in functioning as actually typical for children. For instance, the suggestion that “boys just speak late” is a consistent finding in the literature on India ( Daley, 2004 ; Krishnamurthy, 2008 ). Daley (2004) also pointed out that most parents reported social difficulties first; evidence from our study similarly indicates that difficulties in social settings, such as school, initiated the entry into Phase 3 where parents perceived that there was a persisting problem. Recently, researchers have also found that children’s basic self-care needs and capacity to live in society were central to parenting children with disabilities in South Asia ( Edwardraj et al., 2010 ; Maloni et al., 2010 ).

There is a striking convergence between our findings and a recent study from the USA ( Altiere & von Kluge, 2009 ), which appeared while the present study was being conducted and was reviewed after our findings were written. Both studies report similar evidence concerning a relatively cohesive early parenting phase; a later period of questioning and searching for solutions; and “hindsight” reinterpretations. The studies, however, differ in their descriptions of the meaning of “autism” for parents. In the present study, autism was not received by parents as a fixed entity and clear biomedical diagnosis. Instead, the idea and term were ambiguously perceived. Parents had initially never heard of the term autism, and subsequently disregarded it despite noticing some disruptive behaviors. At a later phase, parents understood autism as indicating an open-ended future. Both studies described this open-ended future, which, as Altiere and von Kluge pointed out, was characterized in part by patience, joy, social advocacy, and fighting for acceptance.

Research from the West has also noted a central paradox that parents of children with autism and other disabilities encounter, specifically of accepting their children as they are while also hoping for change by pursuing solutions to their difficulties ( Avdi, Griffin, & Brough, 2000a ; Landsman, 2003 ; Larson, 1998 ). Larson described the “embrace of paradox” in the face of an indeterminate future as follows:

the management of the internal tension of opposing forces between loving the child as he or she was and wanting to erase the disability, between dealing with the incurability while pursuing solutions, and between maintaining hopefulness for the child’s future while being given negative information and battling their own fears. (1998, p. 873)

This paradox was found to be central for Goan parents in Phase 4. Further, the present study extends the notion of paradox to include parents’ acceptance/change not only of the child but also of the social world . On the one hand, if parents do not accept the social reality and the requirements for participation in it, they cannot help their child adapt to it. On the other hand, parents cannot simply accept the social reality, because it is not entirely suitable or welcoming to their child—so they also endeavor to change the social world. In other words, there was a double paradox of acceptance/change of both the child and the surrounding environment. Parents embraced this paradoxical attitude towards the social world by accepting but changing the social reality. For instance, a group of mothers who helped their children adapt to the current social and practical realities in the local setting also worked with community members and professional mentors to advocate for more vocational opportunities, residential facilities, and a large-scale social security system. Grinker (2007) described similar instances of parents creating social change in India, such as the life story of Merry Barua, a mother of a child with ASD and subsequent founder of a national autism action network, advocating for relevant services and government recognition. These instances of parent empowerment in India resonate around the world with autism and disability advocates, such as those discussed by Grinker (2007) , Shaked (2005) , and others ( Daley, 2004 ; Gray, 2001 ; Luong, Yoder, & Canham, 2009 ; Skinner & Weisner, 2007 ; Woodgate, Ateah, & Secco, 2008 ). Autism advocacy is also exemplified by Temple Grandin ’s (2006) extensive discussion of “developing autistic talents” and focusing on strengths and opportunities over limitations alone.

Previous literature has called for more in-depth, cultural research on parents’ subjective processes ( Daley, 2002 , 2004; Kishore & Basu, 2011 ). Past research on ASD has demonstrated wide variations in the ways parents interpret their child’s early behavioral discrepancies, including consistent nonbiomedical interpretations, with an accompanying time lag between recognition of these discrepancies and professional help-seeking/diagnosis for many parents ( Daley, 2004 ; Kishore & Basu, 2011 ). The period when parents initially perceive disruptive, unexpected behaviors corresponds with Phase 2 found in our study. Parents here perceived temporary deficits in functioning, but these were not viewed as part of a larger problem or as requiring intensive or extensive professional help. Even when the child was given a diagnosis of autism in Phase 2, parents disregarded it as they focused on the particular discrepant behaviors. These behaviors were only later seen by parents as persisting problems and, in Phase 4, as possibly chronic or as early symptoms/indicators of autism upon retrospection to earlier times.

Although the Indian literature has started to broach this issue, it has not sufficiently distinguished early parental perceptions from their later interpretations or the interpretations of professionals. For instance, early parental perceptions have been described in the literature as “initial symptom recognition” ( Daley, 2004 , p. 1327) and “early indicators of autism” ( Kishore & Basu, 2011 , p. 157), which are parents’ retrospective reinterpretations of their child’s early behaviors in later phases. Parents originally did not perceive a behavioral problem of the magnitude of symptom/disorder. More accurately reflective of parents’ initial perceptions are such descriptive phrases as “some aspect of development … not proceeding as expected” ( Daley, 2004 , p. 1327) and “early concerns” and “atypicalities” ( Kishore & Basu, 2011 , p. 162). We propose that this is an important distinction because it may be difficult to fully engage parents without addressing their concerns in ways that are meaningful to them in their particular experiential phase.

Practice implications

The importance of direct parental involvement in the creation and provision of any services for special-needs children in India has been previously noted (e.g., Gupta & Singhal, 2005 ; Kalyanpur, 1996 ). Though professional perspectives differ from those of parents at various points, the present study indicates that professional practices can be related to the essential concerns of parents, and a common ground of understanding and shared purpose is possible.

With regard to the earliest phases, it is important for policymakers to work with communities to help build family relationships with local care systems, remaining respectful of their ways of life and points of view. In the present study, general care networks that supported parents prior to their noticing any serious behavioral discrepancies became relevant and useful when parents perceived a persisting problem. One mother who developed positive relationships with local care providers in the first two phases became empowered by them later when serious problems emerged. Another mother, however, not only lacked supportive service relationships in the first two phases, but had limited local availabilities for care altogether and needed to travel long distances for other options (see also Daley, 2004 , for discussion of geographic/socioeconomic issues in India). For families facing these situations, if caring relationships are developed earlier within the local care system, then parents may feel more empowered and receive immediate care when serious problems emerge.

Regarding Phase 2, though parents view discrepant behaviors as temporary and not a lasting problem for the child, there is an opportunity for communication between family and external helpers. Specifically, the child’s disruptive, unexpected behaviors can pose problems for parents, even if they do not see those problems as requiring extensive professional attention. Here, parents may be receptive to basic advice that addresses their child’s challenging behaviors, such as difficulty falling asleep or uncontrollable crying, which were beginning to exceed parents’ own management capacities in this study. One potentially relevant kind of community resource would be a local support network comprised of parents or caregivers of children with or without ASD as a source of relational support and a resource for “best parenting practices.” Several other researchers have noted the value of parent networking for childhood disabilities in South Asia ( Goldbart & Mukherjee, 2001 ; Gupta & Singhal, 2005 ; Maloni et al., 2010 ; Mirza, Tareen, Davidson, & Rahman, 2009 ; Pal & Chaudhury, 1998 ; Russell, John, & Lakshmanan, 1999 ).

Professionals might recommend early intervention to parents in Phase 2 or earlier, when they have not yet experienced a problem that requires it. This gap presents a dilemma, and further research is warranted. Parents’ major pathway to realizing their child’s long-term needs took place in social situations where they were able to compare their child to other children. A parent network could offer parents in Phase 2 a space to process how their child interacts with others, potentially occasioning an earlier perception of a persisting problem. Such a parent network could be particularly valuable for parents in India who are socially isolated, lack financial resources, and posses less knowledge of vocational requirements (see Maloni et al., 2010 ). For example, the cattle herder in this study did not appear to have means of accessing resources comparable to those of urban, highly educated parents when he needed them. As he succinctly put it: “Poor people like us find it difficult.” At the community level, families in Goa were aided by parent networks formed by a few key parent leaders with the help of professional mentors.

The present study provides evidence of a conflict of beliefs initiated by professional diagnosis in Phase 1 or 2. Professional views may clash with the interpretations of parents and extended family members. This possibility of conflicting viewpoints echoes previous research, which has demonstrated incongruity between parents’ perceptions of their child and scientific or biomedical interpretations offered by experts ( Avdi et al., 2000b ; Feinstein, 2008 ; Gray, 1995 , 2001 ; Landsman, 2003 ; Mandell & Novak, 2005 ; Shaked , 2005 ). In the present study, only after extended observations of their children in relation to other children in social situations did parents gain some realization of the concrete implications of their child’s difficulties (Phase 3). But these realizations took place after what we have called Phase 2, in which the parent viewed the unexpected, incongruent behaviors or deficits as temporary. Scholars have raised cautions about applying Western constructs of abnormality, disease, and treatment to novel populations or cultures ( Gone, 2004 ; Kalyanpur, 1996 ; Shweder, 2008 ; Watters, 2010 ). Our research suggests that without opportunities that will help parents concretely realize and explore their child’s capacities in social situations, diagnostic constructs are likely to have a largely indeterminate meaning that remains at a distance from parents’ and extended families’ practical hopes and activities. This distance limits the potential for parent–provider collaborations.

Beginning in Phase 3 and especially Phase 4, when parents contemplate the future implications of their children’s differences from others, their immediate concern is for alternative social situations that will offer their children opportunities to fulfill their potentials. Here arises the interplay of both the acceptance and reshaping of reality, possibly with the help of others. Professionals—medical, educational, or alternative—could play a key role in understanding this paradox, similar to what Larson (1998) called being “embracers of paradox” (1998, p. 871). Though usually trained primarily to change the child’s behaviors, professionals could also offer knowledge and awareness of social opportunities, and of how to creatively reshape them, as another primary role in serving families. Social action possibilities include developing more diversified paths for adult living for people of all walks of life. There are examples in our study of parents searching for alternative adult livelihoods, such as basic manufacturing and the arts. More opportunities can be created locally, ranging from sustainable jobs to a restructuring of society’s safety nets for differently abled children and adults. To be sure, scenarios where the child adapts to local opportunities, has their needs met, and engages in the tasks required of adults in the local milieu are possible. For example, a key informant (healthcare worker) mentioned witnessing a child with potentially diagnosable intellectual disabilities functioning reasonably well in the shepherding work expected by the child’s family. Development of these diversified pathways is a locally negotiated process that could be enhanced by the exploration and creativity of all interested parties mentioned in this study (see also Grinker, 2007 ).

Cultural/transcultural

The study began with an intent to discover how parents in Goa indigenously understood and cared for their child with ASD. Our study shows that research is needed to shed light on both the local and potentially universal (i.e., highly general) aspects of parental care of a child with ASD. In Goa, examples of the three-part structure—learning to meet the new and unfamiliar, caring for their child’s basic needs, and finding an engaging niche with a sense of belonging for their child in the everyday milieu—included the joy of seeing one’s son identify with the family’s agrarian way of life, the danger of a child throwing a stick from an open flame chula cooking apparatus, and the importance of performing in a Hindu play. Research elsewhere suggests that the four-part developmental sequence and three-part structure of parenting may be found in other cultures and with childhood problems other than ASD. Altiere and von Kluge (2009) described distinct phases including the child developing “normally,” parents’ questioning then searching for solutions, and personal/family growth. Similarly, Shaked’s (2005) study of autism in ultraorthodox Israel demonstrated how parents struggled to reintegrate their child into the religious community that they held so dear by both accepting and challenging social norms (i.e., learning to meet the new and finding engagement and belonging). Further, Grinker’s (2007) poignant narratives of parents of children with ASD included the story of a New York parent who devoted her life to creating alternative vocational and recreational centers (i.e., engagement and belonging) and lifelong housing (i.e., care for basic needs) for older persons with autism. Many aspects of parents’ concerns for their child in the present study appear to be similar to those of parents much more generally, but the manifestations of each caring practice are flavored by the local cultural customs and dynamics. Those local flavors are, in turn, influenced by parenting traditions, availabilities for childcare, and the opportunities for engagement and belonging in the family and community. More research is needed in order to further clarify potentially universal features as well as the many richly diverse local manifestations throughout the world.

Limitations and conclusion

The present study has several limitations. The sample was limited to parents who have had contact with professional care centers and whose child attended various services regularly. Families who never made contact with professionals were not included; the sample thus offered a picture of only a limited segment of local experiences. Also, the study relied on interviews with parents, whereas direct observations of family life were not systematically conducted. Consequently, the current study could not do full justice to the complex everyday experiences of families. The present study in Goa revealed similarities to other areas in India; however, more research from other regions in this vastly diverse country would be needed to further confirm and extend the conclusions of this paper. Further research is particularly needed for examining instances of parents and professionals fruitfully collaborating on the paradox of child acceptance–social acceptance/child change–social change.

This investigation of ASD in India reveals a rapidly changing and dynamic landscape. DSM and ICD diagnostic criteria are increasingly utilized by professionals in India ( Daley & Sigman, 2002 ). The descriptive approach of this study and focus on meaning provided insights into parents’ own perspectives and their discovery of the concept of autism in the midst of these historical developments. Parents’ experiences of their child diagnosed with ASD were found to be intimately tied in with fundamental human concerns: that a child is cared for, belongs in the social world, engages in practical activities, and finds enjoyment and contentment in life. These findings imply that helping families meet these needs locally can go a long way towards supporting parents and children in their life journeys.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Autism Speaks (Grant No. 5621) which supports the Autism Research and Training Initiative (ARTI) Project in Goa. VP is supported by a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellowship in Clinical Science. MD was supported by an APA Minority Fellowship (MHSAS) during this time. We would also like to thank Vivek Vajaratkar, Shaheen Badsha, Quincy Marques, and Deepti Parab. Our technical advisory board included Varsha Dessai, Giselle Lobo, Dr Vibha Krishnamurthy, Dr Sunanda Kolli Reddy, and Dr Shoba Srinath who provided guidance to the ARTI team. We also thank those who offered suggestions along the way, including Sarah Kamens and the qualitative research groups at Fordham and Sangath. Portions of this project were presented at the 118th Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association (Division 32), San Diego, CA. In closing, we gratefully acknowledge the support of the parents and families who made this work possible.

Miraj U. Desai, MA, is a doctoral candidate in clinical psychology at Fordham University and a psychology fellow at the Yale University School of Medicine. He is also an honorary research fellow at Sangath Centre, a community-based health and mental health NGO in Goa, India. His primary research focuses on the following areas: indigenous and cultural psychology; the relationship between psychology and social structures; and contemporary issues in phenomenological psychology, qualitative methods, and philosophy of science. His past research on the lived experience of depression received the Sidney Jourard Award from APA Division 32, Society for Humanistic Psychology. He is a Minority Fellow of the American Psychological Association and is an original member of the Task Force on Indigenous Psychology for APA Division 32. Address: Department of Psychology, Fordham University, Bronx, NY; Sangath, Goa, India. [Email: ude.mahdrof@iasedm ]

Gauri Divan, MRCPCH, is a pediatrician who has been working in the field of developmental and behavioral pediatrics. She is based in Sangath , a nongovernmental organization, working primarily in the field of child development, adolescent health and mental health. Sangath’s key mission and expertise lies in developing and evaluating interventions for childhood developmental disabilities (DD) and mental disorders across the life course, to be delivered through existing public systems. As recognition of its work in Disability, Sangath is the State Nodal Agency for the National Trust for Welfare of Persons with Autism, Mental Retardation, cerebral Palsy and Multiple Disabilities (government of India). As a consultant in Sangath, she provides clinical services which include the administration of the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule. She is also a trained facilitator in the Portage Package for Early Childhood Care and Education, which she used as a model to test its feasibility and acceptability to encourage inclusive education in government preschools. She was a coinvestigator in an Autism Speaks grant which explored the qualitative experiences of parenting a child with autism spectrum disorder in Goa, India and was the site principal investigator for an International Clinical Epidemiological Network Trust ( www.inclen.org ) which led an epidemiological study determining the prevalence of 10 neuro-developmental disorders in India. She is currently a collaborator in another Autism Speaks grant, which is aiming to adapt the Preschool Autism Communication Therapy (PACT) to the South Asian context. She teaches on Sangath’s Leadership in Mental Health Course and has just joined the visiting faculty at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria on their Master’s program in Child and Adolescent Mental Health. She is also on a consultative team for the National Trust (government of India).

Frederick J. Wertz, PhD, Professor of Psychology at Fordham University, received his PhD from Duquesne University in Phenomenological Psychology. His scholarship focuses on the philosophical foundations, research methodology, qualitative analytic methods, theoretical problems, and the cultural context of psychology. He has conducted phenomenological psychological research and also written about psychoanalysis, cognitive psychology, psychometrics, humanistic psychology, and qualitative research. He coedited Advances in Qualitative Research in Psychology: Themes and Variations (1987, Swets North America), edited The Humanistic Movement: Recovering the Person in Psychology (1994, Gardner Press), and coauthored Five Ways of Doing Qualitative Analysis: Phenomenological Psychology, Grounded Theory, Discourse Analysis, Narrative Research, and Intuitive Inquiry (2011, Guilford Publications). He has been the editor of the Journal of Phenomenological Psychology , The Bulletin of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology , and guest editor of The Humanistic Psychologist . He has served as President of APA’s Society for Humanistic Psychology and Society for Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology. He is an APA Fellow, Accreditation Site Visitor, and President of the Interdisciplinary Coalition of North American Phenomenologists. He received the Distinguished Teaching Award in the Sciences at Fordham, where he has chaired the Department of Psychology and serves on the Institutional Review Board.

Vikram Patel, MSc, MRCPsych, PhD, FMedSci, is a Professor of International Mental Health and Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow in Clinical Science at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (UK). He is the Joint Director of the School’s Centre for Global Mental Health ( www.centreforglobalmentalhealth.org ). His primary research spans three themes: investigating the social and cultural determinants of mental disorders; describing the interrelationship of mental disorders with other public health priorities; and evaluating interventions aimed at improving access to effective mental health care in low-resource settings. He serves on a number of committees including the WHO’s Expert Advisory Group for Mental Health and the Technical Steering Committee of the Department of Child & Adolescent Health, and the World Economic Forum Global Agenda Council on Brain and Cognitive Sciences. He is a cofounder of Sangath, a community-based NGO in India ( www.sangath.com ) which won the MacArthur Foundation’s International Prize for Creative and Effective Institutions in 2008. He is a member of a group constituted by the Ministry of Health (government of India) tasked with writing India's first mental health policy and designing the National Mental Health Program for the period of 2012–2017. He was elected a Fellow of the Academy of Medical Sciences of the UK and won the Chalmers Medal from the Royal Society for Tropical Medicine & Hygiene in 2009. His book Where There Is No Psychiatrist (Gaskell, 2003) has become a widely used manual for community mental health in developing countries. He was an editor of both Lancet series' on global mental health (2007 and 2011); the PLoS Medicine series on packages of care for mental and neurological disorders in developing countries (2009); the Lancet series on promoting universal health care in India (2011) and the forthcoming PLoS Medicine Global Mental Health Practice series. He led the efforts to set up the Movement for Global Mental Health ( www.globalmentalhealth.org ). He is based in Goa, India where he leads a program of public health research and capacity development with Sangath, the Public Health Foundation of India and government agencies focusing on three broad areas: child development, adolescent health and mental health.

Appendix. Interview guide

In-depth interview guide for parents.

- Let’s begin with telling me about your family

- How many people stay in this house (with you)?

- What are the children’s names? How old are they?

- Tell me more about your children.

- Probe: Pregnancy planned/unplanned? Experience of pregnancy. Childbirth normal/complicated? Personal emotions, first 3 years or until the parents first suspected/were told that XXX may be different

- As XXX grew up what was life like in the early days?

- Probe: When did you notice anything different about the way she/he was growing? Compared to whom? For what reasons? Did you call it anything in particular? What did you do? If different then how did you manage? Challenges in looking after XXX? What helped? What didn’t?

- As XXX grew how did people respond to him?

- Probe: Were there any behaviors which upset people, family members, siblings, community?

- Is there any advice that was given to you? What helped? What did not? What has changed since XXX was born?

- What did you think was the cause of XXX differences?

- Probe: Did others have a different opinion? Members of extended family? Siblings? Neighbors? Community? Doctors? If cause changed since early days, probe what made this change happen.

- Probe: How the understanding changed over time? For what reason did it change? Track this process through to the current understanding.

Help seeking

- What made you first think you should turn to somebody outside the family for help? (behavior/worry)

- Who did you go to first?

- Probe: Draw a timeline of all persons visited. Probe for each: reasons for consulting this person. What did they tell you? What did you think of the advice (good/bad)? What was done after each interaction? Ask specific: priest, other help. What are you continuing with now?

- Are you satisfied with what was told to you was the problem? How has this influenced your understanding of your child’s behaviors?

Impact/stigma/discrimination

- What is life like with XXX now? Are there any changes that you have made to your day-to- day life?

- Probe: Siblings? Husband/wife? Emotional/financial implications/social/work?

- Probe: Is there anyone you would not tell? Why?

- Are there any places or occasions that you don’t want to go to? What are the reasons? What do you do for XXX’s birthday? (Compare with other siblings).

- Has your relationship with anyone changed because of XXX; how/why?

- Is there any local way/words that people use to refer to XXX? Ways in which people behave towards him/her?

- Probe: What do their terms represent to you? How do you feel about people using such terms?

- Since the diagnosis has anyone’s behavior changed towards you as a family? How do you handle it?

- Have you had any unpleasant experiences related to how you or your child was treated by others? Can you describe a recent experience/worst experience? What happened? What did you do? How did you feel about this? And your child? How has this affected your life?

- Enjoyable moments?

- What support do you have from outside or in the family?

- Probe: Do you know any other family with children with disabilities? Do you meet up with them? Religious agencies? Other sources? Helpful?

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

Child Development and Pedagogy in Hindi : जानिए क्या है चाइल्ड डेवलपमेंट एंड पेडागोजी और इससे जुड़ी संपूर्ण जानकारी

- Updated on

- दिसम्बर 19, 2023

भारत एक ऐसा देश है जिसने हमेशा शिक्षा के क्षेत्र में विश्व को मार्गदर्शन देकर विश्वगुरु बनने का काम किया है। भारत में होने वाले लगभग सभी महत्वपूर्ण टीचर एलिजिबिलिटी टेस्ट (जैसे CTET, UPTET, HPTET, PSTET इत्यादि) का एक महत्वपूर्ण विषय Child Development & Pedagogy in Hindi होता है। सरकारी स्कूलों में काम करने के इच्छुक उम्मीदवार अक्सर KVS, DSSSB जैसे शिक्षक भर्ती परीक्षा भी देते हैं, जिनके लिए इस विषय की तैयारी करना अनिवार्य हो जाता है। बाल विकास और शिक्षाशास्त्र का उद्देश्य उम्मीदवारों को बालक के व्यवहार, रुचियों में हो रहे निरंतर परिवर्तन का अध्ययन कराना होता है। शिक्षकों के लिए होने वाले भर्तियो में भी बाल विकास और शिक्षाशास्त्र से जुड़े प्रश्न पूछे जाते हैं। इस ब्लॉग में उम्मीदवार Child Development & Pedagogy in Hindi के बारे में संपूर्ण जानकारी प्राप्त करेंगे।

This Blog Includes:

Child development and pedagogy in hindi, बाल विकास और शिक्षाशास्त्र की परिभाषाएं, बाल विकास और शिक्षाशास्त्र के उद्देश्य, चाइल्ड डेवलपमेंट एंड पेडागोजी का स्कोप, चाइल्ड डेवलपमेंट एंड पेडागोजी का सिलेबस, चाइल्ड डेवलपमेंट एंड पेडागोजी के लिए आवश्यक बुक्स, child development & pedagogy in hindi questions .

Check Out: UPTET ka Syllabus

मानव की प्रकृति को देखा जाए तो विकास एक निरंतर प्रक्रिया हैं। बाल अवस्था से लेकर वृद्धावस्था तक इंसान में अलग अलग तरह के बदलवा आते है जैसे शारीरिक, मानसिक, सामाजिक। इन सभी का अध्ययन बाल विकास कहलाता हैं।

चाइल्ड डेवलपमेंट एंड पेडागोजी एक ऐसा विषय है, जिसके माध्यम से उम्मीदवार शिक्षक बनने के अपने सपने को पूरा कर सकते हैं, इसकी परिभाषाओं को निम्नलिखित बिंदुओं द्वारा समझा जा सकता है;

- मुनरो के अनुसार – एक ऐसी परिवर्तन श्रृंखला जिसमें भ्रूणावस्था से लेकर प्रौढ़ावस्था तक गुज़रता हैं उसे विकास कहा जाता हैं।

- हरलॉक के अनुसार- विकास का मतलब बढ़ते रहने से नहीं है बल्कि इसमें प्रौढ़ावस्था के लक्ष्य कि और परिवर्तनों का प्रगतिशील क्रम रहता है। विकास के परिणाम स्वरूप इंसान में अनेक में विशेषताएं और नईम योग्यताएं स्पष्ट होती है।

- ड्रेवर के अनुसार-विकास, प्राणी में होने वाला प्रगति शील, जो किसी लक्ष्य की और लगातार केंद्रित होता है उदाहरणार्थ – “किसी भी जाति में भ्रूण अवस्था से लेकर प्रौढ़ अवस्था तक उत्तरोत्तर परिवर्तन है।

बाल विकास की प्रक्रिया को रिसर्च का विषय बनाने से पहले मनोवैज्ञानिकों ने कई महत्वपूर्ण उद्देश्य निर्धारित किए हैं। इसका ज्ञान हर अभिभावक और शिक्षक को होना चाहिए क्योंकि इसका पूरा ज्ञान नहीं होने से शिक्षक अपने कर्तव्य को पूरा नहीं कर सकता है। आइए देखते हैं बाल विकास के उद्देश्य क्या हैं-

- बाल विकास से हर शिक्षक को यह बताया जाता है कि वह संतुलित बाल विकास में किस प्रकार अपना सहयोग दे सकता है।

- बाल विकास के द्वारा बच्चों के विकास में होने वाली विभिन्नताओं के बारे में शिक्षक और अभिभावकों को बताया जाता है।

- इसका प्रमुख उद्देश्य बच्चों के संतुलित विकास के लिए मार्ग बनाना है जिससे वह पूरी तरह विकास को प्राप्त कर सकें।

- बाल विकास की ऐसी योजना तैयार की जाती है जिससे उसके व्यक्तित्व में निखार आय।

- बाल विकास में उन्हें बच्चों के शरीर में होने वाले परिवर्तनों और समस्याओं के बारे में जिसे दूर किया जा सके।

- बाल विकास का उद्देश्य बच्चों को शारीरिक मानसिक एवं सामाजिक रूप से श्रेष्ठा प्रदान करना है जिससे राष्ट्र के विकास में योगदान दे सकें। इन सब से यह पता चलता है कि बाल विकास का उद्देश्य बच्चों के लिए हर तरफ से विकास के मार्ग खोलना है साथ ही उनकी बाधाओं को दूर करना ,जिससे वह संतुलित रूप से जीवन व्यतीत कर सकें और समाज में अपना योगदान दे सकें।

Check Out: टीचर बनने की सोच रहे हैं तो जान लीजिए Deled Syllabus

चाइल्ड डेवलपमेंट एंड पेडागोजी की परिभाषा को जानने के बाद आपको इसके स्कोप के बारे में जान लेना चाहिए, जिन्हें निम्नलिखित बिंदुओं के माध्यम से समझा जा सकता है;

- मानसिक विकास -इसके अंदर बच्चों की क्रियाओं के आधार पर बच्चों के मानसिक विकास का अध्ययन किया जाता है। बच्चों में कई तरह के परिवर्तन आने लगते हैं जो उनके मानसिक विभाग में नजर आते हैं। जैसे-गुस्सा आना, नई चीजों का अध्ययन करना आदि।

- शारीरिक विकास – शारीरिक विकास में भ्रूणावस्था से लेकर प्रौढ़ावस्था तक अध्ययन करना शामिल है, और शारीरिक विकास में आ रही बाधाओं का कारण ढूॅंढ़नाऔर उसका हल निकालना ।

- सामाजिक विकास – बाल विकास के अन्दर बालकों के सामाजिक व्यहवार का अध्ययन किया जाता हैं । लोगों के प्रति गुस्सा, प्यार व्यक्त करना आपनी उम्र के हिसाब से सही व्यहवार करना संतुलित विकास दिखाता हैं ।

- भावनात्मक विकास – अगर बालक अपनी उम्र के हिसाब से खुद को व्यक्त नहीं कर पाता तो वो संतुलत विकास नही हैं। इसमें क्रोध , प्रेम, उत्तेजना आदि का अध्ययन किया जाता हैं ।

- भाषा विकास – बालक अलग अलग तरह की शब्दों का उच्चारण करता हैं जैसे 1 से 9 की उम्र तक शबदोंच्चारण 118 शब्द शब्द होने चाहिए अगर ऐसा हैं नहीं हैं तो बाल विकास ठीक से नहीं हो रहा हैं ।

Check Out: Ancient Indian History Quiz

चाइल्ड डेवलपमेंट एंड पेडागोजी का सिलेबस कुछ इस प्रकार है, जो आपको इसके बारे में विस्तृत जानकारी उपलब्ध कराएगा;

चाइल्ड डेवलपमेंट एंड पेडागोजी के लिए आवश्यक बुक्स के बारे में जानने के लिए नीचे दी गयी टेबल पर एक नज़र अवश्य डालें;

उत्तर – (B)लक्ष्यों को प्राप्त करने पर व्यक्तिगत संतुष्टि

उत्तर – (A) 12 वर्ष

उत्तर – (A)अल्फ्रेड बिने

उत्तर – (A)-प्रत्येक बच्चे के संपर्क में रहना

उत्तर- (D)प्रौढ़ावस्था में

उत्तर (A)परीक्षण और त्रुटि

उत्तर (B)प्रारंभिक बचपन

उत्तर-(A)6 से 14 वर्ष

उत्तर- (A) 125

उत्तर-(B) स्केनर

शिक्षण-कार्य की प्रक्रिया का विधिवत यानि कि सिलसिलेवार तरीके से अध्ययन करना ही शिक्षाशास्त्र या शिक्षणशास्त्र (Pedagogy) कहलाता है।

CheckOut: CTET Syllabus in Hindi

आशा है कि इस ब्लॉग ने Child Development & Pedagogy in Hindi के बारे में सभी आवश्यक जानकारी प्रदान की होगी है। यदि आप ऐसी किसी प्रतियोगिता की तैयारी कर रहे हैं और आपको सहायता की आवश्यकता है, तो Leverage Edu के हमारे विशेषज्ञों से संपर्क करें, जो आपको इस पेपर में सफल होने के लिए टिप्स और ट्रिक्स प्रदान करेंगे! अपना 30 मिनट का निःशुल्क करियर परामर्श सत्र बुक करें और अपना करियर व्यवस्थित करें!

Team Leverage Edu

प्रातिक्रिया दे जवाब रद्द करें

अगली बार जब मैं टिप्पणी करूँ, तो इस ब्राउज़र में मेरा नाम, ईमेल और वेबसाइट सहेजें।

Contact no. *

संक्षिप्त में समझाने का सबसे बेहतर तरीका। इसे पीडीएफ में बनाया मैंने धन्यवाद इस सामग्री के लिए..

आपका धन्यवाद, ऐसे ही हमारी वेबसाइट पर बने रहिए।

बच्चों के विकास के बारे में आप ने बहुत ही प्रशंसनीय जानकारी लिखी है। धन्यवाद !

धन्यवाद बलराम, ऐसे ही आप हमारी वेबसाइट पर बने रहें।

This is the best information because of your great writing skills and knowledge. I got to learn a lot by visiting this page.

इस ब्लॉग को सराहने के लिए आपका बहुत-बहुत आभार।

Leaving already?

8 Universities with higher ROI than IITs and IIMs

Grab this one-time opportunity to download this ebook

Connect With Us

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. take the first step today..

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

September 2024

January 2025

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

LEARNING DISABILITY : A CASE STUDY

The present investigation was carried out on a girl name Harshita who has been identified with learning disability. She is presently studying at ‘Udaan’ a school for the special children in Shimla. The girl was brought to this special school from the normal school where she was studying earlier when the teachers and parents found it difficult to teach the child with other normal children. The learning disability the child faces is in executive functioning i.e. she forgets what she has memorized. When I met her I was taken away by her sweet and innocent ways. She is attentive and responsible but the only problem is that she forgets within minutes of having learnt something. Key words : learning disability, executive functioning, remedial teaching

Related Papers

The Indian Journal of Pediatrics

Sunil Karande , Madhuri Kulkarni

International Journal of Scientific Research in Computer Science Applications and Management Studies

Monika Thapliyal

This paper reviews the research work on 'learning disability' in India. It studies the social and educational challenges for learning disabled, and details research in India, concerning the aspects of diagnosis, assessment, and measures for improvement. The paper critically examines the development in their teaching-learning process, over the years. It highlights the role of special educator in their education and explores the impact of technology and specific teaching-aids in the education of learners with learning disability. The later part of the paper, throws light on the government policies for learning disabled and attempts to interpolate their proposed effect in their learning. It concludes with possible solutions, learner progress, based on the recommendations from detailed analysis of the available literature.

International Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics

Shipra Singh

Background: Specific learning disability (SLD) is an important cause of academic underachievement among children, which often goes unrecognized, due to lack of awareness and resources in the community. Not much identifiable data is available such children, more so in Indian context. The objectives of the study were to study the demographic profile, risk factors, co-morbidities and referral patterns in children with specific learning disability.Methods: The study has a descriptive design. Children diagnosed with SLD over a 5 years’ period were included, total being 2015. The data was collected using a semi-structured proforma, (based on the aspects covered during child’s comprehensive assessment at the time of visit), which included socio-demographic aspects, perinatal and childhood details, scholastic and referral details, and comorbid psychiatric disorders.Results: Majority of the children were from English medium schools, in 8-12 years’ age group, with a considerable delay in seek...

Journal of Postgraduate Medicine

Sunil Karande

Fernando Raimundo Macamo

IJIP Journal