David Schulenberg

Wagner college faculty site, music of the baroque: worksheets and paper assignments.

All contents are copyright (c) 2012 by David Schulenberg. All rights reserved. Permission is granted to students and teachers in schools, colleges, and universities to download this page or any portion of it for use in planning or developing courses in Baroque music or related subjects. Permission is NOT granted for republication in any form, including print and online electronic publication, except through hypertext links to the present webpage.

To David Schulenberg’s home page

Suggested paper topics Comparison of settings of the same motet or madrigal text by different composers Early-Baroque musical drama Fugue analysis Comparison of French- and Italian-style vocal works Concert report Comparison of different performances of a work Performance project

Worksheets About worksheets (click here for an explanation of what they are and how I use them in class) Palestrina, Dum complerentur Lassus, Timor et tremor Madrigals by Gesualdo and Monteverdi La Pellegrina and Caccini (For Monteverdi, Orfeo and Combattimento , see the paper on early-Baroque musical drama ) Strozzi Alessandro Scarlatti and Henry Purcell Lully Gabrieli and Schütz Handel, Orlando Rameau, Les indes galantes Bach, Cantata 127 Handel, Jephtha Frescobaldi Gaultier, Froberger, Jacquet, and Couperin Buxtehude Concertos by Vivaldi and J. S. Bach C. P. E. Bach Study outline for final exam

Suggested paper topics

Comparison of settings of the same motet or madrigal text by different composers

Composers often wrote musical settings of favorite texts that had been previously set to music by other composers. In fact, most of the motets and madrigals included in our textbook sets a text that also exists in other musical settings. In this paper you will compare one of the settings from the textbook with another setting of the same text:

Text 1: Dum complerentur Setting in textbook by: Palestrina Alternate setting: also by Palestrina, but in four voices instead of six Note: Palestrina also composed a parody mass, based on the six-part motet Dum complerentur.

Text 2: Timor et tremor Setting in textbook by: Lassus Alternate setting by: Giovanni Gabrieli

Text 3: Luci serene Setting in textbook by: Monteverdi Alternate setting by: Gesualdo

Text 4: Sfogava con le stelle Setting in textbook by: Caccini Alternate setting by: Monteverdi

Your comparison might focus on two aspects of each work: (1) the musical setting and (2) the use of musical rhetoric. Musical “setting” includes such things as the ensemble for which the work is written (how many voices and/or instruments), the texture, the presence or absence of virtuoso writing, and similar aspects of the music. Musical rhetoric involves the relationships between the music and the text (see textbook, Box 2.3 on page 33).

Be sure to mention points of difference between the two works as well as points of similarity. You might also want to consider which of the two settings is more effective, or whether each composer has chosen to bring out different aspects of the text.

Whichever option you select, be sure to cite specific examples from both works. When you mention examples, be sure to identify the measure number and the voice or part to which you are referring. It is not necessary to do additional reading or research, but if you do so you must use footnotes properly in order to cite any information taken from outside sources.

Back to the top

Early-Baroque musical drama

In this paper you will examine a portion of your choice from either of the two stage works by Monteverdi discussed in the textbook: Orfeo and the Combattimento . Please select any one of the following segments of either work:

Orfeo : messenger scene (anthology, Selection 6b, mm. 15–152) Orfeo : Orfeo’s lament and the following chorus (Selection 6b, mm. 171–247) Combattimento : the invocation of Night (Selection 7, mm. 73–133) Combattimento : the second battle and the wounding of Clorinda (Selection 7, mm. 299–340)

The paper should be three to five pages long. It should be double-spaced, and it must be printed legibly and clearly. Be sure to proofread your work after it is printed. An occasional handwritten correction is acceptable, but misspelled words, incomplete sentences, and other typographical and grammatical errors are not.

It is not necessary to do any research beyond studying the text and score and doing the assigned reading and listening. As in any paper, however, material that you take from another source must be properly credited to its author, using a standard footnote format (a separate bibliography is not necessary). For a simple guide to citation style and other aspects of format in a college paper, see the author’s style and format page .

You may use the list below as an outline for your paper. Items 2–4 in the list include numerous questions, but you need not address all of them. Throughout the paper, be sure to refer to specific examples in the musical score, and always mention the measure number(s) and the words in the Italian text for each musical passage that you discuss.

1. Statement of topic. Identify the composer, the work, and the performing forces (voices and instruments for which it is written). Give an approximate date of composition and any other essential historical background. Name the author of the poetic text and give crucial information about the latter.

2. Plot and action. What portion of the work are you analyzing? In this portion of the work, where does the action take place; which characters are involved? What crucial events take place?

3. Music: general description. Does this portion of the work comprise distinct sections? What genre does each section represent (recitative, aria, etc.)? What is the scoring of each section (which voices and instruments participate)? Does any section fall into a standard form, such as ABA (da capo) form or strophic aria form?

4. Music and text. Can you relate anything in the music to individual words or phrases in the text, or to particular events in the action? For example, does the music employ instances of word painting, long melismas, or unusual harmonies? On what words do those devices fall? Do changes in scoring, tonality (key), or style of the vocal writing accompany events in the action? Are there any particularly striking moments in the music that merit detailed description?

Fugue analysis

In this assignment you will analyze the fugue in B-flat major (no. 21) from Part 1 of J. S. Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier . Please make two copies of the score, one for your own use and one to hand in as described below. You will be turning in (I) a marked copy of the score, (II) a form diagram or chart, and (III) a commentary three double-spaced pages in length. If you are unsure of the meaning of any terms used in this assignment, please review Box 11.1 in the textbook (pp. 254–7).

I. Begin by listening to the piece while following the score. Then (1) mark in the score all complete entries of the subject: place brackets or parentheses at the beginning and end of each statement. Label each such statement with the name of the voice (soprano, alto, or bass) and the key in which it occurs. (2) Next, do the same for any countersubject(s), labeling each statement of a countersubject in an appropriate manner. (3) When you are finished, you may discover that there are passages from which the subject is absent. If any of these passages are more than a measure or two in length, label each one as an episode. (4) Finally, mark each cadence by drawing an arrow from the dominant note to the tonic note in the bass line where each cadence occurs. Label each cadence with the key (major or minor) in which it occurs.

II. Next, make a chart comparable to the one given in the textbook for the fugue in G (table 11.2, p. 264). Use the same format and abbreviations employed in the textbook. You may find that the present fugue has special features not found in the one in G; if so, feel free devise your own way of illustrating these features in your chart.

III. Finally, write a three-page commentary explaining your chart. Begin by describing the subject and any countersubject(s) or other recurring thematic material in the work. Be sure to mention the location in the score of each item that you describe: identify both the measure number and the voice (e.g., soprano, bass) in which it occurs.

Also please explain the structure of the fugue as depicted in your chart. Mention: the number of expositions and episodes the pattern of the modulations any special features, such as: second subjects multiple countersubjects inversions of any subject or countersubject strettos sequences based on motives drawn from the subject or countersubject

Many Bach fugues contain an episode that is restated several times. Please identify by measure number any recurring episodes in this fugue. Also describe any alterations that the episode undergoes (for example, transposition).

Comparison of French- and Italian-style vocal works

The distinction between French and Italian style is crucial for understanding Baroque music. In this paper you will compare examples of vocal or instrumental works from the two traditions, thereby examining the differences between French and Italian approaches to musical style. You will take somewhat different approaches, depending on whether you choose vocal or instrumental works. For a summary of distinctions between French and Italian style, see Box 8.1 in the textbook (p. 159). This box focuses on opera, but many of the items listed apply to other types of music as well.

Option 1: vocal. Compare an aria from an Italian-style work of the later Baroque with a substantial air or aria-like passage from a contemporary French-style work. Italian-style arias are those in the works by Alessandro Scarlatti, Handel (both opera and oratorio), and Bach (cantata). Comparable passages in the French style passages can be found in the works by Lully, Charpentier, and Rameau. You may also select works not discussed in the textbook.

You might first identify several specifically Italian and French features, respectively, in each work. Consider such elements of style as: musical form expressive treatment of the text presence or absence of ornament signs and embellishments special features of the vocal writing. use of instruments You may also want to give your judgement of the overall dramatic or expressive quality or character of each selection.

Option 2: instrumental. Compare two instrumental compositions belonging to the same or similar genres. You might select two sonatas, two suites, two concertos, or two fugues. In the case of multi-movement works, you need not consider all movements. You may include one work that is not from the syllabus for this course.

Your discussion should include, but should not be limited to, your identification of French and Italian characteristics of each work. Other topics to consider include: form harmony and modulation presence or absence of ornament signs and embellishments the use of particular instrumental devices or techniques In addition, you may want to give your judgement as to the overall dramatic or expressive quality or character of each work.

Concert report

A “concert report” is based on one major work that you have heard in a live performance. It includes a historical introduction about the work and its composer; an analysis of the music, and a review of the performance. In place of a single major work, such as a cantata or a concerto, you may select a group of shorter compositions performed together. If the work you have chosen is very long, such as an opera, you should select a single portion containing ten to twenty minutes of music. In an opera or oratorio, a series of scenes containing three or four arias would be appropriate.

You will probably find it helpful to get to know the work prior to attending the performance. This means: get a score and look it over if reporting on a vocal work, also get a libretto, including translation, and read it, as well as any other relevant verbal material (such as a list of characters, or a synopsis) listen several times to a recording of the work, with score and libretto

The paper should be between three and five double-spaced pages in length, not counting bibliography, notes, or examples. It should include, but not be limited to, the following elements:

Basic identification and description of the music: full name of the composer complete title of work, including its instrumentation and/or voices date, time, and place of performance; name(s) of performer(s) Background information about the music essential biographical information about the composer essential historical information about the music Analysis of the music identify its genre describe its overall form and the forms of individual movements analyze any special features, great moments, etc. Description and critique of the performance special or unusual aspects of the performance comparison with recording(s), if available what was effective or ineffective, moving or dull (etc.) about the performance

Comparison of different performances of a work

Among the major themes of this textbook are the instruments and historical performance practices (vocal as well as instrumental) used in the music that we have studied. Today, many performances of this music employ so-called authentic or original instruments and practices–that is, reconstructions of historical performing conditions. Other performances, especially of music from the later Baroque, employ present-day instruments and approaches to performance.

For this assignment, find two recorded performances of a single work, such as a Bach cantata or a Handel opera. One performance should identify itself as using “original,” “authentic,” or “period” instruments and practices; the other should employ a “modern” performance approach. First, identify differences between the two performances in objective terms: the instruments used, the numbers and types of performers (including chorus members, if any), any differences in the choice or ordering of movements or sections of the work. Then identify differences in aspects of interpretation that are, again, relatively objective: the precise tempo used in each movement; the use or addition of specific ornaments, embellishments, or cadenzas; or the use of dynamics, rubato (variations in tempo), and other devices. In identifying each difference, be sure to refer to specific movements, citing exact vocal or instrumental parts and measure numbers where appropriate.

Finally, consider the overall effect of each performance. Are there differences in the expressive character of the two performances? Is one performance more moving, more dramatic, or more exciting than the other? If there is something that you find unappealing or unsuccessful about one performance, is it possible to explain what the performer(s) had in mind or why they chose to perform the work in that particular way?

Performance project

In this project you will prepare a presentation about any significant Baroque work. The presentation may be either a performance of the work or a brief talk about its performance. Presentations may be by individuals or by groups. Each presentation will be followed by discussion in which any member of the class may contribute.

The work chosen need not be from the syllabus, but it should have been composed between 1600 and 1750. It may be a work you are studying as a performer or as a member of an ensemble. Two or more students may participate together in a presentation; in fact you are encouraged to form groups for this purpose. The work chosen for this project may also be the subject of one of your papers for this course. Information to get you started on this project can be found in many of the commentaries that follow scores in the anthology, and in books listed in the section of the textbook’s bibliography devoted to performance practice and organology (pp. 348–51).

What we are looking for is not a perfect performance but rather a presentation showing thoughtful consideration of some of the issues that arise when performing a Baroque work. These issues include (but are not limited to): finding a reliable edition of the music choosing an appropriate tempo scoring (choosing instrument(s) and/or the type and number of voices realizing the figured bass, if any how to realize any ornament signs what unwritten ornaments and embellishments, if any, to add rhythmic conventions appropriate instrumental and vocal techniques (bowing, articulation, vibrato, etc.).

If you choose to do a performance, your presentation should consist of: (1) performance of the work (2) discuss one or two specific questions of performance that arose in your study or rehearsal of the work, such as: how to perform a particular ornament what tempo to use what instruments or voices to use Be prepared to demonstrate alternative solutions to each question. Also, be sure to refer to at least one recording or some written source that illustrates a solution to the problem (many editions include discussions of such matters).

If you choose not to do a performance, please give a verbal presentation in which you identify at least three specific problems or questions concerning the performance of the work. Be sure to include your own suggestions as to how to solve these questions. You will need to illustrate your presentation with examples from a score or selections from a recording of the work–preferably both. It would be especially effective if you could compare different recordings of the work, showing how different performers have dealt with the performance issues that you discuss.

Whether or not your presentation includes a performance, plan on taking a total of fifteen minutes to twenty minutes, including the performance (if any). You will need to plan your verbal comments ahead of time, choosing your examples carefully and speaking precisely and to the point. Groups will want to work out ahead of time which individual member addresses which issues. It will help to make an outline of your presentation and distribute it to all group members and to the class!

What I call worksheets are series of questions about individual composers and works discussed in the two textbooks. Most worksheets begin with a section where students identify the composer, dates, and similar information pertaining to each work. There follow a number of general questions concerned with the composer’s biography, social or historical background, and the like, drawing on readings in the textbook. From here the worksheets continue to more interpretive or analytical questions about specific compositions.

Worksheets can be used in several ways. I distribute each one ahead of time, as part of the assignment for the class that will take up the composition to which the worksheet pertains. Students complete the worksheets as homework while carrying out appropriate reading and listening assignments (see my class webpage for a sample syllabus). The completed worksheets serve as an outline for the class meeting and as a basis for class discussion. Later, the same completed worksheets serve students as study guides.

Worksheets may or may not be collected and graded. In some classes, one or two students are given responsibility for completing a given worksheet and leading the class discussion to which it applies.

Naturally, every instructor will want to adapt the questions to his or her own class. Few classes will use all of the worksheets or all of the questions included here. Many instructors will wish to include a greater amount of sociological or interpretive material than I have included here. The content of these worksheets reflects my own particular focuses as well as the types of students and programs in which I have taught this subject.

Worksheet: Palestrina, Dum complerentur

Composer (full name, with dates): Genre: Date of first publication: Scoring (how many voices? any instruments?):

1. Where in Europe was this work probably composed?

2. How many singers would probably have participated in its first performance? What instrument(s), if any, would have joined them?

3. Several words can be used to describe musical texture in these scores: monophonic, homophonic, contrapuntal, imitative, antiphonal. Which of these words describes the texture in the following passages from the first part of the work: mm. 1–3? mm. 12–13? mm. 17–20? mm. 31–34? mm. 42–46?

4. Two words that can be applied to the musical settings in these works are: syllabic, melismatic. Which word describes the setting of: the word complerentur in the upper voice, mm. 2–3? of dicentes in mm. 15–16? of alleluja in the tenor, mm. 20–22? of alleluja in the sextus, mm. 25–27? of et subito in all voices, mm. 31–35?

5. In this type of music, melismas can be used to emphasize syllables or words. Find two words in the Latin text that are so treated; identify the English word to which each corresponds and indicate which syllables are emphasized by melismas.

6. The Latin text of this work falls into distinct units separated by commas, periods, and other marks of punctuation. Sometimes the music changes texture at corresponding points; describe two instances of this (give the measure number at which the change occurs, and indicate how the texture changes).

7. Using the guidelines given in Box 2.2 in the textbook (pages 26–27) to: (a) identify the mode of the motet and indicate the basis for your answer (b) locate three cadences (for each cadence, give the measure number and identify the two voices that form the cadence).

Worksheet: Lassus, Timor et tremor

1. Name the two main sacred genres of music in which both Palestrina and Lassus as well as other contemporary composers were active.

2. In what ways were the careers of Lassus and Palestrina similar?

3. In what ways were they different?

4. Explain this statement: both Lassus and Palestrina were interested in musical rhetoric.

5. Define: word painting ( = text painting).

6. What types of musical rhetoric are there besides text painting?

7. What is its mode? State the reasons for your decision.

8. Find three cadences: explain in what measures and voices each occurs, and on what note.

9. Box 2.3 (textbook, p. 33) contains a list of various techniques of musical rhetoric, divided into three main categories. Find two examples from each category: (a) devices that articulate form (b) devices that concern declamation of the text (c) text painting. For each, give the measure number and voice(s) involved, as well as the word or phrase of the text, and explain how Lassus’s motet employs rhetoric.

Worksheet: Madrigals

Work 1 Composer (full name, with dates): Genre: Date of first publication: Scoring (how many voices? any instruments?):

Work 2 Composer (full name, with dates): Genre: Date of first publication: Scoring (how many voices? any instruments?):

1. Find two examples of the following in each work (list measure numbers in which each occurs): (a) homophony (b) imitation (c) melisma (d) chromaticism

2. In each work, locate one cadence: give the measure number and indicate which two voices form the cadence and on which pitch(es).

3. The poems as printed in the anthology contain six and nine numbered lines, respectively. In the two scores, write the number of each line of text in each voice as it occurs.

4. In the first work, find the division in the score between lines 4 and 5. How does the music articulate this division?

5. Another division occurs in the first work between lines 5 and 6; how is this division articulated?

6. In the first work, find two words or phrases that are emphasized by the music, and explain how this is accomplished.

7. In work 2, explain how the musical setting of lines 4-6 is similar to that of lines 1-3.

8. In the second work, find several imitations of the subject that the tenor states in m. 42.

9. In the second work, which of the following words characterize the subject stated by the tenor at m. 41: morose, lively, flowing, chromatic, diatonic, syncoapted? Which words in the Italian text might have elicited this particular subject?

10. Which of these words characterize the musical phrase sung by the canto (soprano) in mm. 50–5 of the second work: morose, lively, flowing, chromatic, diatonic, syncopated? Which words in the Italian poem might have elicited this musical setting?

11. In the second work, mm. 27–8 contain both a conventional suspension and an irregular one. In both cases, one of the two upper voices forms a dissonance against the bass. In the score, mark all intervals that both voices form against the bass; indicate which intervals are dissonances and identify which one is resolved irregularly.

12. In mm. 57–8, the soprano (canto) sings a dissonant melodic interval; what is the interval and how does its use here reflect the text?

Before answering the remaining questions of this worksheet, be sure you understand the discussions of the Artusi-Monteverdi controversy and dissonance treatment in the “second practice” (textbook, pp. 39–40).

13. Measures 28–9 of Luci serene contain both a conventional suspension and an irregular one. In both cases, one of the upper voices forms a dissonance against the bass. Identify the voices involved and the intervals that each forms with the bass. Also, explain which dissonance receives irregular treatment and what is irregular about it.

14. There is another irregular dissonance in m. 30; explain.

15. The tenor of m. 42 contains two passing dissonances; identify the notes involved and the interval that each forms with the bass. These notes occur on weak parts of the beat and are resolved by stepwise motion; hence they involve no irregular dissonance treatment.

16. The motive from the tenor in m. 42 is subsequently imitated by all four other voices. Find these statements of the motive and identify passing dissonances in each.

17. Find a dissonant interval between two voices in m. 53; is it treated regularly or irregularly?

18. In mm. 57-8, the soprano (canto) sings a dissonant melodic interval; what is the interval and how does its use here reflect the text?

Worksheet: La Pellegrina and Caccini

Note: The first work appears as Example 3.2 in the textbook (pp. 55–6).

Work 1 (Godi, turba mortal) Composer (full name, with dates): Genre: Date of first performance: Scoring (how many voices? how many instrumental parts?):

Work 2 (Sfogava con le stelle) Composer (full name, with dates): Genre: Date of first publication: Scoring (how many voices? what type of instrumental part?):

1. Explain the significance of La Pellegrina , which was a spoken play, for the history of European music.

2. Where, when, and for what occasion was La Pellegrina performed?

3. Name some composers and performers who participated in the performance of La Pellegrina .

4. One type of music heard in the performance of La Pellegrina is termed monody. What is monody?

5. How does the scoring of work 1 resemble that of an earlier work by Luzzaschi (shown in the textbook, example3.1 on page 50)?

6. Work 1 contains written-out embellishment for the singer. Identify two types of embellishment that work 1 shares with the example by Luzzaschi.

7. Was work 2 performed during La Pellegrina ?

8. In work 2, what term describes the lower (untexted) staff of the score?

9. In work 2, what instrument(s) might have played the lower staff? What do the numbers and other symbols attached to this part mean?

10. Caccini was very insistent that music should respect the meaning and expressive character of the text. In what ways does work 2 succeed in doing this? (You might consider declamation, word-painting, and harmony; identify specific examples of each, citing measure numbers.)

11. Are both works 1 and 2 through-composed, or are there repetitions of music and/or text? Give the measure numbers of any repeated passages.

12. Find at least two examples of written-out embellishment in the vocal part of work 2. Give measure numbers and describe the figuration used in each case (trill? turn? scale? see pp. 50-51 of the textbook).

Worksheet: Strozzi

Composer (full name, with dates): Genre: Date of first publication: Scoring:

1. In what city was this work composed? first performed? published?

2. What was unusual about the circumstances of this work’s composition and its probable first performances?

3. Who wrote the poetic text of this work? What was the poet’s relationship to the composer?

4. In what sense is this work a strophic aria? Name another instance of a strophic aria that we have studied; how does the present work differ?

5. Our work shows the direct influence of Monteverdi. Find one or two examples of each of these instances of Monteverdian treatment of individual words (give the measure number, the Italian word, and the latter’s English translation): (a) a long melisma used to emphasize a word; (b) a chromatic passage employed for word painting; (c) a passage in the stile concitato; (d) an instance of the seconda pratica, i.e., irregular use of dissonance.

6. Box 5.1 in the textbook (p. 94) provides an outline of the form of this work. Locate in the score each of the triple-time sections. Is there anything in the text of these sections to justify or explain the change of meter?

7. Box 5.1 also shows that each section of the work includes a passage that moves from a minor key (d) to a major key (F). Can you explain, based on the text, why the key and mode change at these points?

8. Figure 5.1 in the textbook (p. 92) shows the opening of this work as it was originally published. Compare this with the edition in the anthology and identify three ways in which the notation of the two differs.

Worksheet: Alessandro Scarlatti and Henry Purcell

Work 1 (Correa nel seno amato) Composer (full name, with dates): Genre: Approximate date of composition: Scoring:

Work 1 (From rosy bowers) Composer (full name, with dates): Genre: Date of first publication: Scoring:

1. For what type(s) of compositions is each composer best known?

2. In what city or cities did each composer work?

3. In the aria “Fresche brine” from the Scarlatti work, give measure numbers for: (a) the ritornello; (b) the motto; (c) the B section.

4. The textbook (p. 106) refers to a turning motive in “Onde belle” that represents the word onde (“waves”). List the measures in which this motive appears and circle each appearance in both instrumental and vocal parts.

5. In the opening movement of the Purcell work, identify one example of each of the following (give the word on which it occurs and the measure number): (a) word painting by means of a melisma; (b) chromaticism; (c) irregular dissonance treatment.

6. The closing movement of the Purcell work (“No, no, no”) could be described as beginning with recitative and concluding with arioso. In what measure and on what word(s) does the shift occur?

7. Box 5.2 of the textbook (pp. 98–9) lists the movements, keys, etc., for the Scarlatti cantata. It also summarizes the forms of the two arias “Fresche brine” and “Onde belle.” Make a similar list of movements, keys, etc., for the Purcell work. Include a summary of the form of Purcell’s aria “Or say, ye pow’rs.”

Worksheet: Lully

Composer (full name, with dates): Genre: Date of first performance: Scoring:

1. In the first part of the overture (anthology, Selection 12a, mm. 1–10), identify three rhythmic patterns whose performance differs from what a literal reading of the notation would suggest.

2. In the second part of the overture (mm. 10–25), identify the subject (theme) and locate each instance at which it is imitated.

3. In Armide’s recitative from the end of Act 2 (Selection 12b, mm. 20–71), what does Armide wish to do? how does the music express her hesitation in carrying out her plan?

4. In Armide’s air “Venez, seconder mes désirs” (Selection 12b, mm. 90–113), identify all full cadences (give key and measure number for each). How do these cadences break up the text?

5. Act 3, scene 2 alternates closely between recitative and air. Does this remind you more of (a) early Italian Baroque works (Monteverdi, Strozzi) or (b) later Baroque ones (Purcell, A. Scarlatti)?

6. In Armide’s air “Plus Renaud m’aimera” (textbook, Example 6.5, p. 129), the meter is notated in 6/4 but actually shifts between 6/4 and 3/2 from measure to measure. Indicate the accented beats, or the actual meter, of each measure. Bear in mind that in 6/4, accents fall on beats 1 and 4; in 3/2 accents fall on beats 1, 3, and 5. It will help to observe that the final syllable is accented in most French words, except for “e” (without an accent mark) at the end of a word.

7. The prelude, aria, and chorus for Hate and her followers open Act 3, scene 4 (see textbook, Examples 6.6–7, pp. 131–2). In this section, find two persistent rhythmic motives and explain their expressive or dramatic significance.

Worksheet: Gabrieli and Schütz

Work 1 (In ecclesiis) Composer (full name, with dates): Genre: Approximate date of composition: Scoring:

Work 2 (Herr, neige) Composer (full name, with dates): Genre: Date of first publication: Scoring:

Work 3 (Saul, Saul) Composer (full name, with dates): Genre: Date of first publication: Scoring:

1. With what major musical city is the first composer associated? In what other city(ies) and with what other important composer(s) did he work or study?

2. Work 1 is a polychoral composition. (a) How many choirs are there? (b) List the vocal and/or instrumental parts of each choir. (c) Is there a continuo part? What instrument(s) play(s) it? (d)

3. Give examples of other works by this composer: (a) a polychoral work for instruments alone; (b) a non-polychoral instrumental work.

4. Find the text for work 1 in the anthology (Selection 13, p. 123). Coordinate this text with the form diagram in the textbook (Box 7.2, p. 142) by: (a) circling statements of the refrain within the text (b) underlining lines of text in which the soloists are joined by the capella (c) highlighting or shading over lines of text accompanied by the instrumental choir

5. Next, in the score, write the words “refrain,” “soloist,” “soloist + capella,” and “instruments” at appropriate points above the top line of the score.

6. In work 1, for each of the following, identify the word(s), measure number(s), and instrumental and/or vocal part(s) on which there occurs an example of: (a) monody (b) antiphony (c) imitation (d) written-out melodic embellishment (e) chromaticism

7. The textbook (Box 7.3, pp. 145–6) gives an outline of the second composer’s biography. On this outline, find points of intersection with the life of composer 1. Also identify where and in what capacity composer 2 was working when he published work 2.

8. In work 2 ( Herr, neige ), find an example of each of the following (a) vocal part containing an embellished doubling of the basso continuo (b) a point of imitation that involves both voices and violins (c) chromaticism

9. For work 3, make a form diagram similar to the one given in the textbook for work 1.

10. In work 3, find one example of each of the following (identify the German word(s), measure number(s), and instrumental or vocal part(s) in which each occurs): (a) expressive use of rhythm, meter, or tempo (b) word painting through an unusual dissonance (c) expressive use of dynamics

Worksheet: Handel Opera

Composer (full name, with dates): Title: Date of first performance: Scoring (list the voices used for the characters who sing in our selections, as well as the instruments of the orchestra):

1. This is an example of a what type of Italian opera typical of the eighteenth century? List several ways in which this type of opera (a) differs from the French operas of Lully (b) resembles the cantata Correa nel seno amato by Alessandro Scarlatti

2. Which character sings the first aria in our anthology? What is the aria text about, and what is the dramatic situation? (See the synopsis in Box 8.3, pp. 172–3.)

3. In the first aria, what is the voice-type of the singer and which instruments play here?

4. The textbook (Table 8.1, p. 175) contains a form diagram for the aria “Oh care parolette.” (Caution: the aria is mislabled in the table caption as “Se il cor mai ti dirà.”). In the score of the aria (anthology, Selection 18, p. 157), finds the points of structural division whose measure numbers are listed in the form diagram. Draw a vertical line through all the parts at those points.

5. In the score of the same aria, locate each of the cadences listed in the form diagram; circle the dominant and tonic notes in the bass line for each of these cadences.

6. Still in the first aria, do the instrumental parts ever play at the same time as the singer? Why or why not?

7. What is the dramatic situation for the aria “Fammi combattere” (anthology, p. 163)?

8. Examine the libretto of “Fammi combattere” (anthology, p. 169). Note the numbers for the lines of the Italian text. Copy these numbers into the vocal part of the score, at appropriate points.

9. What word(s) receive(s) musical emphasis in the A section of “Fammi combattere”? How is/are the word(s) emphasized? Does any word receive musical emphasis in the B section?

10. Does the ritornello of “Fammi combattere” reflect the meaning of any of the words? If so, which words and how?

11. Also within the score of “Fammi combattere,” locate (a) each ritornello or ritornello fragment; (b) each cadence at the end of a ritornello or vocal passage. Note: the strings enter several times within vocal passages, but only those entries marked f (forte) should be considered ritornellos.

12. Make a form diagram for this aria, following the model in the textbook on p. 175.

Worksheet: Rameau

Composer (full name, with dates): Genre: Date of first complete performance: Scoring:

1. What is the dramatic situation for the scenes in the anthology (Selection 19, p. 171)?

2. What features does the recitative in these scenes share with that of Lully?

3. What features of these scenes are distinctive to Rameau?

4. What dance is suggested by Zima’s air? What musical features of her air are characteristic of the dance you have named?

5. In Zima’s air, is the texture formed by the voice and the two violin parts primarily contrapuntal or primarily homophonic? Explain.

6. In the duet at the end of the scene, find two examples of traditional musical rhetoric: (a) word painting (b) emphasis of a word through repetition

7. Is the relationship between the two vocal parts in the duet primarily imitative or primarily homophonic? Could one say that the texture of this duet reflects the new relationship between Zima and Adario?

Worksheet: Bach cantata

1. In what city and in what position was Bach working when he composed this piece? Where and in what years did he previously work?

2. How do Bach’s sacred cantatas differ from the Italian cantatas studied earlier? Where and for what purpose were they performed?

3. The last movement of this work is a chorale setting; explain.

4. In what sense can the opening movement be considered a ritornello form? In what sense can it be considered a cantus firmus movement? a paraphrase movement?

5. In the opening orchestral section of the first movement, locate two statements of the first phrase of the chorale melody; circle the eight notes of each statement

6. In the initial choral entry (mm. 17ff.), circle the statements of the first phrase of the chorale melody in all four voices. How would you describe the texture here?

7. In the second choral entry (mm. 26 ff.), which voice sings the second melodic phrase of the chorale? What is the source of the material sung by the other voices? How would you describe the texture here?

8. Movement 2 is designated as a recitative. What sort of recitative is it–simple? accompanied? Could any portion be considered arioso? which portion?

9. In the aria (mvt. 3), how does the ritornello relate to the opening vocal statement (mm. 9-15)?

10. Find an explanation in the text for the sustained note (B-natural) on beats 3-4 of the opening measure of both ritornello and vocal entry. Also explain the harmony on this note.

11. Why do the strings enter only in the B section (m. 31)? Why do they play pizzicato? What is the tonality at this point? Where and to what key does the next modulation occur?

12. Movement 4 is designated in the score as recitative and aria, but one might distinguish within it three types of writing: recitative, arioso, and aria. Find the points at which one type leads to another. What type of recitative is present–simple or accompanied?

13. Why is there a trumpet part in this movement only? Identify trumpet-like or military motives in the string parts of both recitative and aria sections.

Worksheet: Handel oratorio

This worksheet focuses on the chorus in the anthology (Selection 21b, p. 210). There is a simple analytical table for this music in the textbook (Table 9.1, p. 211).

1. Where would Handel originally have performed this work? When?

2. What number and types of voices comprised the chorus that Handel used? Which part did he play in the performance?

3. In the opening section, how do the instrumental parts complement the voices?

4. Why is the second section described in the analytical table as “canonic”? Which voices are involved in the canon?

5. In section 2, does any word receive emphasis or word painting (look in the alto, mm. 25–32)? Explain.

6. The third section is described as a fugue. List the voices in the order in which they enter with the fugue subject. Also identify the note on which each voice enters.

7. The anlytical table describes the last section as “alternatingly contrapuntal, declamatory.” In what measures do the contrapuntal passages begin? the declamatory ones?

8. Is either of the two types of passage identified in the previous question associated with any particular word(s) or phrase in the text?

9. The textbook (Figure 9.5, page 205) shows a page of the composer’s manuscript for this work. Find the corresponding measures of the edition in the anthology and identify three ways in which Handel’s notation differs from that of the modern edition.

Worksheet: Frescobaldi

1. In what city did the composer work? Name some other compositions that he wrote.

2. The textbook (table, p. 235) describes this work as falling into several distinct sections. In the score, draw lines through the staves at the appropriate points to mark the divisions between sections.

3. Frescobaldi employs written-out ornaments similar to those that we observed previously in vocal music of his time. In the the score, circle and label several examples of each of the following; list below the measure numbers in which each appears: (a) trills (b) turns (c) scalar figuration

4. One hallmark of Baroque improvisational style is surprise. Find an example of each of the following (give measure numbers below): (a) a harmonic surprise, such as a sudden change of key or mode (b) a melodic surprise, such as an unusual melodic interval (c) a sudden change of style, texture, or rhythmic motion

5. Mark the cadences at the ends of sections 1, 3, and 6 as follows: at each cadence, circle the dominant and tonic notes in the bass, then connect them by an arrow. Label each cadence with a letter indicating the key (uppercase letter for major keys, lowercase for minor).

6. Section 5 treats several motives in imitation. First, draw brackets over each of these motives and label them with the letter shown below: a: ascending tied figures (tenor, last note of m. 40 through penultimate note of m. 41) b: three or four short notes followed by a descending leap to a longer one (soprano, last four notes of m. 41 through downbeat of m. 42) c: ascending chromatic notes (lowest voice in m. 41, last note, through note 3 of m. 42).

7. Next, find subsequent entries of each of the motives described above and label them in the same way.

Worksheet: Gaultier, Froberger, Jacquet, and Couperin

Note: this worksheet covers the French-style pieces by Gaultier, Froberger, and Jacquet de La Guerre discussed in chapter 10, as well as those by Couperin discussed in chapter 11.

Work 1 Composer (full name, with dates): Genre: Date of first publication: Scoring:

Work 2 Composer (full name, with dates): Genre: Date and place of composition: Scoring:

Work 3 Composer (full name, with dates): Genre: Date of first publication: Scoring:

Work 4 Composer (full name, with dates): Genre: Date of first publication: Scoring:

1. The following chart summarizes the characteristics of the dance movements used in works 1, 2, and 3. Please complete the chart using the descriptions of the dances in the textbook and your analysis of the music. The first portion of the chart has been done for you.

Dance Meter Tempo Expressive Musical elements character (rhythm, texture, etc.)

allemande C moderate restrained broken chords movement in flowing sixteenths upbeat consisting of one sixteenth courante

gigue 2. In each of the last three works, identify an ornament sign and locate it on one of the ornament tables in the anthology (Selection 29). List below the name of the ornament sign, the measure in which it occurs, and a brief verbal or graphic description of how it is played:

Work 2. Mvt. ________. Measure ___. Ornament name: _____________. Description:

Work 3. Mvt. ________. Measure ___. Ornament name: _____________. Description:

Work 4. Mvt. ________. Measure ___. Ornament name: _____________. Description:

3. Work 4 consists of two movements by Couperin. Each has a descriptive title. Describe two ways in which the music of each might reflect its title.

Worksheet: Buxtehude

Work 1 ( Nun bitten wir ) Composer (full name, with dates): Genre: Approximate date of composition: Scoring:

Work 2 (Praeludium) Approximate date of composition: Scoring:

1. In which city did Buxtehude work? Name some other compositions by him.

2. In what sort of room(s) or building(s) and for what purpose(s) work 1 have been performed? work 2?

3. Compare the upper line (top staff) in work 1 to the soprano part in Schein’s setting of the same chorale melody (textbook, Example 11.1, p. 251): (a) Number the phrases in Schein’s setting (each phrase ends with a barline) (b) Now enter the same numbers at corresponding points in the score of work 1 (you may want to skip ahead to the next step before completing this one!) (c) In the score of work 1, place an asterisk (*) above each note of the soprano that corresponds with a note of the melody as set by Bach

4. Both works 1 and 2 employs written-out ornaments and embellishments similar to those used by Frescobaldi. In both of the present works, circle and label several examples each of the following (list measure numbers below): (a) trills (b) turns (c) scalar figuration

5. The textbook (p. 252) describes work 2 as falling into several distinct sections. In the score, draw lines through the staves at the appropriate points to mark the divisions between sections.

6. Mark imitation in the fugal sections of work 2 by placing brackets or parentheses around each statement of the subject. Also label each statement of the fugue subject with the name of the key and voice in which it occurs. (Table 11.1 in the textbook, p. 258, lists all entries of the subject.)

7. What is a countersubject? In the Buxtehude work, place each statement of the two countersubjects in brackets or parentheses. Using the numerals 1 and 2 to refer to the two respective countersubjects, label each entry of a countersubject in the score; also the name the voice in which it occurs.

Back to the top Worksheet: Concertos by Vivaldi and J. S. Bach

Work 2 Composer (full name, with dates): Genre: Date of the composer’s autograph manuscript: Scoring:

1. Where might one have heard each of these works performed? For each, name (a) a city (b) a social or architectural setting

2. The textbook contains a form diagram for the third movement of work 1 (Table 13.1 on page 318). Make a similar diagram for the first movement of work 1.

3. The solo sections in the quick movements of work 1 contain virtuoso violin figuration or passagework. Find examples of violin figuration in the solo sections of the last movement; list below measure numbers in which each of the following types of passagework occur: (a) scales (b) arpeggios (c) other (describe)

4. Work 2 represents a somewhat more complex version of the type of composition found in work 1. In what ways is it more complex? Consider: (a) instrumentation (b) form (c) texture (d) harmony

5. Table 13.2 (textbook, p. 320) summarizes the form of the first movement of Work 2. Why are certain ritornellos listed by capital letter (R) and others by small letter (r)?

6. The same table lists two sections described as “BACH.” Why are the sections so labeled? What notes in what measures correspond to the letters B, A, C, and H?

7. One of the soloists of work 2 does not play in the second movement of Work 2; why not?

8. The textbook shows an analytical chart for the last movement of work 2, which is a fugue (Table 13.4, page 324). Locate entries of the subject and countersubject(s) in the score, placing brackets around each entry and identifying the keys in which the subject occurs (do this at least through m. 57). (a) Does the movement contain any tonal answers? In what parts, in which measures? (b) Is there a regular countersubject? In what parts, in which measures? (c) Are there any strettos? Between which parts, in which measures? (d) What is distinctive about the episodes? Note: the trumpet is a transposing part, written in C but sounding in F.

Worksheet: C. P. E. Bach

Full name of composer, with dates: Genre, key, and identifying number of work: Instrumentation: Date and place of composition:

1. What was the composer’s occupation at the time he wrote this work?

2. Name some other types of music written by this composer.

3. What famous book did this composer also write? When and where?

4. How many movements comprise this work? What is the key of the second movement?

5. Are all three movements in the same key? What is the key of the second movement?

6. Describe the opening theme of the first movement. In what measures does this theme recur? in what keys? is it altered in any way?

7. Beginning at m. 21, the middle section of the first movement repeats music from the opening section. How far (up to what measure) does this repetition extend? How is the music altered?

8. Music from the opening section of the first movement again recurs at m. 42. How far does this restatement extend? How is the music altered?

9. The texture of the second movement resembles that of a trio sonata. Explain.

10. In what measures and in what keys does the opening theme of the second movement return?

11. The form of the third movement is similar to that of the first movement. In what ways are the two movements similar? in what ways are they different?

12. Although more homophonic than older Baroque keyboard music, this work retains a contrapuntal element. In the third movement, find examples of invertible counterpoint involving the motivic ideas introduced at m. 9.

13. The music of this composer is often described as empfindsamer, a German term suggesting emotional intensity or hyperexpressivity. Describe some intensely expressive or dramatic aspects of harmony, phrasing, or motivic work in all three movements. (Consider, for example, the fermatas in the first movement, sudden changes of mode in the second movement, and the harmonic surprise just after the double bar in the third movement.)

Study outline

This is a list of things to think about in preparation for a final examination in a course on Baroque music. Each item in this list should bring to mind the titles of relevant pieces or examples of related ideas of concepts.

Elements of late-Renaissance music genres: motet, madrigal texture and scoring modality cadences consonance and dissonance musical rhetoric Compositional techniques common to music of the late Renaissance and the Baroque paraphrase cantus firmus imitation variation Innovations of the the Baroque new vocal genres: continuo madrigal, opera, cantata, oratorio new instrumental genres: toccata, praeludium, prelude (and fugue), suite, sonata, concerto French dances: allemande, courante, sarabande, gigue, minuet, gavotte, chaconne forms based on modulation to different tonalities new types of instrumental ensemble ensembles combining voices and specified instruments basso continuo new vocal styles: recitative, aria, arioso idiomatic types of instrumental music division of cantatas, sonatas, etc., into distinct movements distinct French and Italian styles Forms and their associated genres through-composed form: motet, madrigal, sacred concerto, recitative, prelude strophic form: early-Baroque aria, chorale variation forms: strophic aria, passacaille, chaconne binary forms: most dances, some sonata movements, some arias ternary forms: Da Capo aria rondo-like forms: French Baroque keyboard pieces, some vocal works French overture ritornello form: instrumental concerto, late-Baroque aria Musical rhetoric devices that articulate form devices for declamation of the text devices that reflect the meaning of the text Performance practices sources for information about performance: treatises, instruments, musical manuscripts, the compositions themselves musical instruments: types no longer used; changes in those that are still used ornament signs and embellishments basso continuo: notation; instruments used Music in its social and cultural context types and status of composers and performers amateur, professional lay, religious types and status of audiences middle-class aristocracy professional musicians the role of gender in influencing: the activities of individuals as composers, performers, patrons, and audience members the subjects of texts and dramatic works the ways in which music represents people, ideas, and dramatic characters places for hearing and performing music: private homes palaces churches monasteries theaters occasions for hearing and performing music private gatherings diplomatic and political events religious services public concerts how music was transmitted and disseminated aurally by manuscripts by printed music

All contents copyright (c) 2012 by David Schulenberg. All rights reserved. No portion of this page may be republished or distributed except as noted at the top of this page.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.38: More on the Baroque Period

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 72569

Here is another overview and summary of the Baroque period; however, this reading contains more information on the early years of the Baroque. Pay special attention to the references to the Florentine Camerata, a group of scholar-musicians in Florence, Italy. Their discussions were particularly influential in the development of a new style of music that marks the beginning of the Baroque.

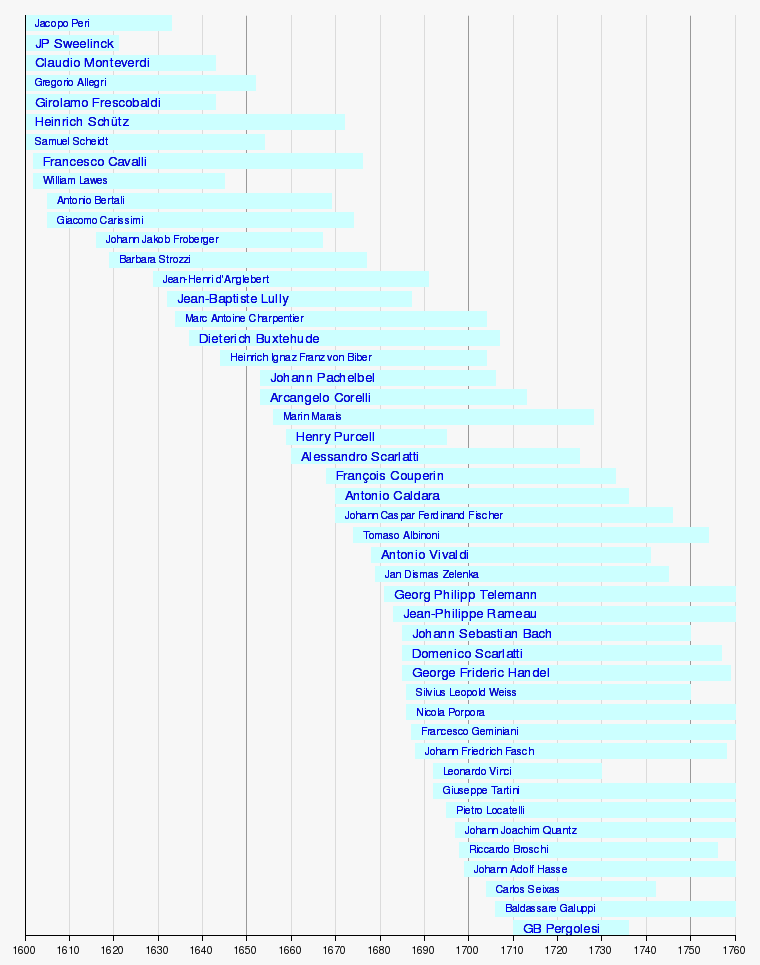

The composer timeline near the end of this page is a handy resource. I want you to get a sense of the number of significant composers that we just don’t have time to study. It’s also a handy index to the composers we do reference in our reading materials. If you’re interested in specific composers, feel free to do an internet search to find more information about them.

There is also a list of instruments common in this period. You don’t need to study the instruments individually; however, as you come across references to different instruments in later readings (instrumental music becomes much more important in the Baroque than it was in the Renaissance) you’ll have this as a glossary that you can refer to.

Introduction

Baroque music is a style of Western art music composed from approximately 1600 to 1750. This era followed the Renaissance, and was followed in turn by the Classical era. The word baroque comes from the Portuguese word barroco , meaning misshapen pearl , a negative description of the ornate and heavily ornamented music of this period. Later, the name came to apply also to the architecture of the same period.

Baroque music forms a major portion of the “classical music” canon, being widely studied, performed, and listened to. Composers of the Baroque era include Johann Sebastian Bach, George Frideric Handel, Alessandro Scarlatti, Domenico Scarlatti, Antonio Vivaldi, Henry Purcell, Georg Philipp Telemann, Jean-Baptiste Lully, Arcangelo Corelli, Tomaso Albinoni, François Couperin, Denis Gaultier, Claudio Monteverdi, Heinrich Schütz, Jean-Philippe Rameau, Jan Dismas Zelenka, and Johann Pachelbel.

The Baroque period saw the creation of tonality. During the period, composers and performers used more elaborate musical ornamentation, made changes in musical notation, and developed new instrumental playing techniques. Baroque music expanded the size, range, and complexity of instrumental performance, and also established opera, cantata, oratorio,concerto, and sonata as musical genres. Many musical terms and concepts from this era are still in use today.

History of European Art Music

The term “Baroque” is generally used by music historians to describe a broad range of styles from a wide geographic region, mostly in Europe, composed over a period of approximately 150 years.

Although it was long thought that the word as a critical term was first applied to architecture, in fact it appears earlier in reference to music, in an anonymous, satirical review of the première in October 1733 of Rameau’s Hippolyte et Aricie, printed in the Mercure de France in May 1734. The critic implied that the novelty in this opera was “du barocque,” complaining that the music lacked coherent melody, was filled with unremitting dissonances, constantly changed key and meter, and speedily ran through every compositional device.

The systematic application by historians of the term “baroque” to music of this period is a relatively recent development. In 1919, Curt Sachs became the first to apply the five characteristics of Heinrich Wölfflin’s theory of the Baroque systematically to music. Critics were quick to question the attempt to transpose Wölfflin’s categories to music, however, and in the second quarter of the 20th century independent attempts were made by Manfred Bukofzer (in Germany and, after his immigration, in America) and by Suzanne Clercx-Lejeune (in Belgium) to use autonomous, technical analysis rather than comparative abstractions, in order to avoid the adaptation of theories based on the plastic arts and literature to music. All of these efforts resulted in appreciable disagreement about time boundaries of the period, especially concerning when it began. In English the term acquired currency only in the 1940s, in the writings of Bukofzer and Paul Henry Lang.

As late as 1960 there was still considerable dispute in academic circles, particularly in France and Britain, whether it was meaningful to lump together music as diverse as that of Jacopo Peri, Domenico Scarlatti, and J.S. Bach under a single rubric. Nevertheless, the term has become widely used and accepted for this broad range of music. It may be helpful to distinguish the Baroque from both the preceding (Renaissance) and following (Classical) periods of musical history.

The Baroque period is divided into three major phases: early, middle, and late. Although they overlap in time, they are conventionally dated from 1580 to 1630, from 1630 to 1680, and from 1680 to 1730.

Early baroque music (1580–1630)

The Florentine Camerata was a group of humanists, musicians, poets and intellectuals in late Renaissance Florence who gathered under the patronage of Count Giovanni de’ Bardi to discuss and guide trends in the arts, especially music and drama. In reference to music, they based their ideals on a perception of Classical (especially ancient Greek) musical drama that valued discourse and oration. As such, they rejected their contemporaries’ use of polyphony and instrumental music, and discussed such ancient Greek music devices as monody, which consisted of a solo singing accompanied by a kithara. The early realizations of these ideas, including Jacopo Peri’s Dafne and L’Euridice , marked the beginning of opera, which in turn was somewhat of a catalyst for Baroque music.

Concerning music theory, the more widespread use of figured bass (also known as thorough bass ) represents the developing importance of harmony as the linear underpinnings of polyphony. Harmony is the end result of counterpoint, and figured bass is a visual representation of those harmonies commonly employed in musical performance. Composers began concerning themselves with harmonic progressions, and also employed the tritone, perceived as an unstable interval, to create dissonance. Investment in harmony had also existed among certain composers in the Renaissance, notably Carlo Gesualdo; however, the use of harmony directed towards tonality, rather than modality, marks the shift from the Renaissance into the Baroque period. This led to the idea that chords, rather than notes, could provide a sense of closure—one of the fundamental ideas that became known as tonality.

By incorporating these new aspects of composition, Claudio Monteverdi furthered the transition from the Renaissance style of music to that of the Baroque period. He developed two individual styles of composition—the heritage of Renaissance polyphony (prima pratica) and the new basso continuo technique of the Baroque (seconda pratica). With the writing of the operas L’Orfeo and L’incoronazione di Poppea among others, Monteverdi brought considerable attention to the new genre of opera.

Middle baroque music (1630–1680)

The rise of the centralized court is one of the economic and political features of what is often labelled the Age of Absolutism, personified by Louis XIV of France. The style of palace, and the court system of manners and arts he fostered became the model for the rest of Europe. The realities of rising church and state patronage created the demand for organized public music, as the increasing availability of instruments created the demand for chamber music.

The middle Baroque period in Italy is defined by the emergence of the cantata, oratorio, and opera during the 1630s, and a new concept of melody and harmony that elevated the status of the music to one of equality with the words, which formerly had been regarded as pre-eminent. The florid, coloratura monody of the early Baroque gave way to a simpler, more polished melodic style. These melodies were built from short, cadentially delimited ideas often based on stylized dance patterns drawn from the sarabande or the courante. The harmonies, too, might be simpler than in the early Baroque monody, and the accompanying bass lines were more integrated with the melody, producing a contrapuntal equivalence of the parts that later led to the device of an initial bass anticipation of the aria melody.

This harmonic simplification also led to a new formal device of the differentiation of recitative and aria. The most important innovators of this style were the Romans Luigi Rossi and Giacomo Carissimi, who were primarily composers of cantatas and oratorios, respectively, and the Venetian Francesco Cavalli, who was principally an opera composer. Later important practitioners of this style include Antonio Cesti, Giovanni Legrenzi, and Alessandro Stradella.

The middle Baroque had absolutely no bearing at all on the theoretical work of Johann Fux, who systematized the strict counterpoint characteristic of earlier ages in his Gradus ad Paranassum (1725).

One pre-eminent example of a court style composer is Jean-Baptiste Lully. He purchased patents from the monarchy to be the sole composer of operas for the king and to prevent others from having operas staged. He completed 15 lyric tragedies and left unfinished Achille et Polyxène .

Musically, he did not establish the string-dominated norm for orchestras, which was inherited from the Italian opera, and the characteristically French five-part disposition (violins, violas—in hautes-contre, tailles and quintes sizes—and bass violins) had been used in the ballet from the time of Louis XIII. He did, however, introduce this ensemble to the lyric theatre, with the upper parts often doubled by recorders, flutes, and oboes, and the bass by bassoons. Trumpets and kettledrums were frequently added for heroic scenes.

Arcangelo Corelli is remembered as influential for his achievements on the other side of musical technique—as a violinist who organized violin technique and pedagogy—and in purely instrumental music, particularly his advocacy and development of the concerto grosso. Whereas Lully was ensconced at court, Corelli was one of the first composers to publish widely and have his music performed all over Europe. As with Lully’s stylization and organization of the opera, the concerto grosso is built on strong contrasts—sections alternate between those played by the full orchestra, and those played by a smaller group. Dynamics were “terraced”, that is with a sharp transition from loud to soft and back again. Fast sections and slow sections were juxtaposed against each other. Numbered among his students is Antonio Vivaldi, who later composed hundreds of works based on the principles in Corelli’s trio sonatas and concerti.

In contrast to these composers, Dieterich Buxtehude was not a creature of court but instead was church musician, holding the posts of organist and Werkmeister at the Marienkirche at Lübeck. His duties as Werkmeister involved acting as the secretary, treasurer, and business manager of the church, while his position as organist included playing for all the main services, sometimes in collaboration with other instrumentalists or vocalists, who were also paid by the church. Entirely outside of his official church duties, he organised and directed a concert series known as the Abendmusiken, which included performances of sacred dramatic works regarded by his contemporaries as the equivalent of operas.

Late baroque music (1680–1730)

Through the work of Johann Fux, the Renaissance style of polyphony was made the basis for the study of composition.

A continuous worker, Handel borrowed from others and often recycled his own material. He was also known for reworking pieces such as the famous Messiah , which premiered in 1742, for available singers and musicians.

Timeline of Baroque Composers

Baroque Instruments

- Violino piccolo

- Viola d’amore

- Viola pomposa

- Tenor violin

- Angélique

- Hurdy-gurdy

- Baroque flute

- Cortol (also known as Cortholt, Curtall, Oboe family)

- Musette de cour

- Baroque oboe

- Natural horn

- Baroque trumpet

- Tromba da tirarsi (also called tromba spezzata )

- Flatt trumpet

- Sackbut (16th- and early 17th-century English name for FR: saquebute , saqueboute ; ES: sacabuche ; IT: trombone ; MHG: busaun , busîne , busune / DE (since the early 17th century) Posaune )

- Trombone (English name for the same instrument, from the early 18th century)

- Tangent piano

- Fortepiano—early version of piano

- Harpsichord

- Baroque timpani

- Wood snare drum

Styles and Forms

- Basso continuo— a kind of continuous accompaniment notated with a new music notation system, figured bass, usually for a sustaining bass instrument and a keyboard instrument.

- The concerto and concerto grosso

- Monody—an outgrowth of song

- Homophony—music with one melodic voice and rhythmically similar accompaniment (this and monody are contrasted with the typical Renaissance texture, polyphony)

- Dramatic musical forms like opera, dramma per musica

- Combined instrumental-vocal forms, such as the oratorio and cantata

- New instrumental techniques, like tremolo and pizzicato

- The da capo aria “enjoyed sureness.”

- The ritornello aria—repeated short instrumental interruptions of vocal passages.

- The concertato style—contrast in sound between groups of instruments.

- Extensive ornamentation

- Opera seria

- Opéra comique

- Opera-ballet

- Passion (music)

- Mass (music)

Instrumental

- Chorale composition

- Concerto grosso

- Sonata da camera

- Sonata da chiesa

- Trio sonata

- Passacaglia

- Chorale prelude

- Stylus fantasticus

Contributors and Attributions

- Authored by : Elliott Jones. Provided by : Santa Ana College. Located at : http://www.sac.edu . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Baroque music. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : http://en.Wikipedia.org/wiki/Baroque_music . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Mix and match activities to create a fun lesson about the baroque period in music. Integrate Solfeg.io in teaching about baroque composers and analyzing their pieces.

🎲 What's included in the activities:

- Analyzing a baroque piece

- Learning about the baroque period in music

- Learning about Johann Sebastian Bach

- Analyzing a baroque manuscript

- Listening and analyzing a modern version of a baroque piece

- Ideas for homework & further lessons (Beyond the lesson)

💻 Materials:

- Solfeg.io web app best used with Chrome browser

- Projector or computer and access to Wi-Fi

Air on the air

🕐 Time: 10 min

🎯 Objectives:

- Analyze a baroque piece

🎶 Recommended Songs:

🎲 Activity:

-Play Johann Sebastian Bach's Air from Orchestral suite No. 3 in D major, BWV 1068 on Solfeg.io web app with muting the synth and rhythm lines (find them in Controls - Volume ).

-Discuss the piece:

- Have you heard this piece before?

It has been cited in other songs, used in films and adverts. Here are some examples (you can play excerpts from them, if you wish):

'A Whiter Shade of Pale' by Procol Harum, a rock song from the 1960s;

'Everything's Gonna Be Alright' by Sweetbox, a hip-hop song from the 1990s;

French pianist Jacques Loussier did a jazz interpretation of the piece;

Film composer Hugo Montenegro used the piece in his 'Love Theme' in the movie 'The Godfather';

The piece was interpreted on a Moog synthesizer by the American electronic music composer Walter (later Wendy) Carlos and included in the groundbreaking album 'Switched-On Bach' (1968).

- How would you describe the mood of the piece? ( Such adjectives could be used as nostalgic, longing, wistful, calm, moving, airy, graceful, elegant, subtle, delicate etc.)

- What instruments are played in this piece? ( Violin, viola, cello, double bass, harpsichord).

What's baroque about baroque?

🕐 Time: 15 min

- Learn about the baroque period in music

- Learn about Johann Sebastian Bach

-Bach's Orchestral suite No. 3 and thus its 2nd movement - the air we just heard - was written around 1731, so almost 300 years ago.

-Probably at least some of the students will have heard the piece somewhere before and there are different versions and interpretations of the piece made in different times, so you could assume it's popular. Discuss it with the class!

- What makes one musical piece more popular than others?

- Why, in your opinion, this piece from 300 years ago is still remembered and liked while some pop songs that were in the top of the charts only a few years ago are forgotten?

-The Air could be considered the most famous piece from the Baroque era.

- Talk about Baroque, its timeframe and the characteristics of art in this era. Some facts you can choose to mention:

An era in the Western art; a style of architecture, music, painting, sculpture and other arts.

Its time frame is usually considered from 1600 until 1750.

The word 'baroque' derived from the Italian word 'barocco', used during the Middle Ages by philosophers to describe an obstacle in logic and later came to denote anything absurdly complex. Another possible source of the word is the Portuguese word 'barroco' which means a flawed or imperfectly shaped pearl.

In general, the baroque art is characterized by complexity, the desire to evoke certain emotional states, dynamism, movement, tension, grandeur and sharp contrasts.

Mention the most famous composers of the Baroque era, for example, George Friedrich Handel, Antonio Vivaldi, Henry Purcell, Domenico Scarlatti, Barbara Strozzi etc. And of course, Johann Sebastian Bach!

-The piece is composed by Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 - 1750) - a German composer, organist, harpsichordist, violist and violinist.

- The most celebrated member of a large family of north German musicians.

- Bach worked as a musician at different churches and courts and as a musical director and choirmaster at one of the oldest schools in the world - St. Thomas in th German city of Leipzig.

- He has composed more than 1000 works and is the author of masterpieces in every major Baroque musical genre except opera: sonatas, concertos, suites and cantatas.

- Bach wasn't an appreciated composer during his lifetime, he was considered 'outdated'.

- Bach was married twice and had 20 children.

- Mark that the year Bach died corresponds to the end of the Baroque era.

Explore the Baroque dance suite

- Analyze a baroque-time manuscript

- Divide the class into five groups.

- Find a manuscript score of Bach's Orchestral suite No. 3 in D major, BWV 1068 in public domain! (for example, here )

- Give each group a manuscript score of a movement from the suite (Overture, Air, Gavotte, Bouree, Gigue) .

- Each group has a look at their score and tries to find an answer to these questions (for the last two of these, they might have to look it up on the internet

What instruments play in this movement?

What time signature is the movement in?

How long is the movement (how many pages)?

What does the name of the movement mean?

How would you describe the character and the mood of this movement?

- Explain any unclear or foreign terms students encounter.

- Each group presents their findings to the class. Do it in the order of movements of the suite!

The Air under the microscope

- Analyze the characteristics of a baroque piece

- Listen and analyze to a modern version of a baroque piece

-As you might have noticed in the previous exercise, Air is quite a contrast to the other movements (be reminded of contrasts as a characteristic of Baroque art!).

- Air is the only movement where only string instruments play (two violin parts, viola and bass) - other movements feature oboes, trumpets and timpani too.

- It is the shortest of all movements (only 18 measures!).

- Even though the Orchestral suite is based on the form of dance suite, Air is not a dance - it's an English term for 'aria' which normally signifies a lyrical piece for a solo voice, also used to mean 'melody', 'tune' or 'song'.

Arias are most commonly associated with opera (a drama in which the actors sing throughout), a musical genre which developed during the Baroque era.

- Open 'The Air on the G String' by Johann Sebastian Bach in Solfeg.io player and solo the bass track (under the menu 'Controls' - 'Volume).

- Listen to the bass line of the A part and discuss its characteristics.

It's an example of 'walking bass' ( In Baroque music, a term used informally for a bass line that moves steadily and continuously in contrasting (usually longer) note values to those in the upper part or parts. - Grove Music Online)

If you follow the notation, you'll see that it moves in steps of a scale interspersed with octave leaps.

The bass line gives the sense of perpetual movement to Air. Remember that dynamism, movement and tension is characteristic to the Baroque art in general.

In the original score, the bass line is marked as 'basso continuo' - it's an instrumental line, over which the player improvises a chordal accompaniment (in the video you watched earlier, it was done on harpsichord).

- Now, unmute the 1st violin part and listen how it sounds together with the bass.

- As the piece unfolds, unmute the parts of the 2nd violin and viola.

These are marked as 'ripieno' in the score, meaning they fulfill the role of harmonic 'stuffing' or ripieno in Italian.

Explain to students how polyphony works in this piece and how the lines of simultaneous independent melodies interact - point the students' attention to the melodies in violin and viola parts, played during the long notes of the 1st violin part.

- Explain where the name 'The Air on the G String' originates from.

Almost 150 years after Bach's Orchestral suite No. 3 was written, the violinist August Wilhelm arranged its 2nd movement for violin and piano. He changed the key of the piece so that it could be played on one string - the lowest, also called G string - of the violin.

- Time to hear another arrangement of the piece: unmute all the tracks, including the synth and rhythm lines!

- After listening, ask your students:

What was different about this arrangement?

Which instruments did you hear?

How did you like it?

🕐 Time: 5 min

- Consolidate the knowledge about the baroque period

- How does the mood of the piece change when the synth and rhythm part is added?

- If you did an arrangement of this Air, how would it be different from the original?

Beyond the Lesson

- Solidify the knowledge about the baroque period