Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

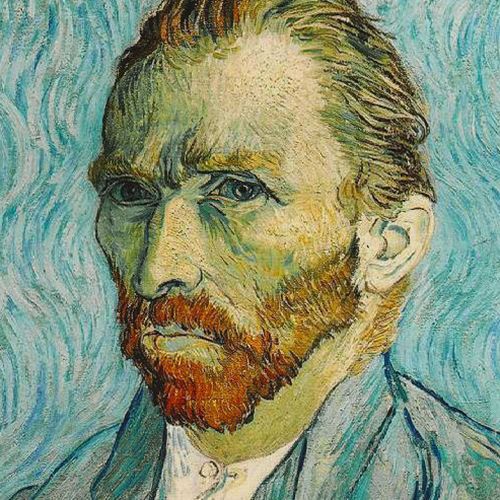

Vincent van gogh (1853–1890): the drawings.

Road in Etten

Vincent van Gogh

Nursery on Schenkweg

Street in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer

Wheat Field with Cypresses

Corridor in the Asylum

Colta Ives Department of Drawings and Prints, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Susan Alyson Stein Department of European Paintings, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2005

Generally overshadowed by the fame and familiarity of his paintings, Vincent van Gogh’s more than 1,100 drawings remain comparatively unknown, although they are among his most ingenious and striking creations. Van Gogh engaged drawing and painting in a rich dialogue, which enabled him to fully realize the creative potential of both means of expression.

Largely self-taught, Van Gogh believed that drawing was “the root of everything.” His reasons for drawing were numerous. At the outset of his career, he felt it necessary to master black and white before attempting to work in color. Thus, drawings formed an inextricable part of his development as a painter. There were periods when he wished to do nothing but draw. Sometimes, it was a question of economics: the materials he needed to create his drawings—paper and ink purchased at nearby shops and pens he himself cut with a penknife from locally grown reeds—were cheap, whereas costly paints and canvases had to be ordered and shipped from Paris. When the fierce mistral winds made it impossible for him to set up an easel, he found he could draw on sheets of paper tacked securely to board.

Van Gogh used drawing to practice interesting subjects or to capture an on-the-spot impression, to tackle a motif before venturing it on canvas, and to prepare a composition. Yet, more often than not, he reversed the process by making drawings after his paintings to give his brother and his friends an idea of his latest work.

Van Gogh produced most of his greatest drawings and watercolors during the little more than two years he spent working in Provence.

Etten: 1881 Van Gogh was aimless until, in late 1880, he decided to take up the practice of art—mainly on the advice of his brother Theo, who was his principal source of support. He moved from Brussels to his parents’ house in Etten and applied himself wholeheartedly to a self-designed program of instruction focused on drawing and the study of artists’ books on technique, anatomy, and perspective.

Hoping to become a genre illustrator/painter, Van Gogh began by drawing figures in relatively static poses, usually in profile. In a few unpremeditated landscapes of this period, the artist revealed, for the first time, uncommon spirit and ingenuity.

The Hague, Drenthe, and Nuenen: 1882–85 While in the Netherlands, Van Gogh remained focused on his study of the human figure. He was profoundly inspired by the social realism of the masters Rembrandt , Millet, and Daumier but also admired the dark graphic reports of magazine illustrators. In The Hague (January 1882–September 1883), he found models to draw in shelters for the poor and in crowded back streets. In rural Nuenen (December 1883–November 1885), he studied peasants working the earth or weaving at looms.

Always more at ease drawing landscapes, Van Gogh continued to record local scenery in increasingly intricate penwork while perfecting his mastery of perspective. He enjoyed contact with the Hague school artists and picked up commissions for two series of city views from his uncle C. M. Van Gogh, an art dealer. After a brief sojourn to the peat fields of Drenthe (September–November 1883), he discovered his voice as a draftsman in Nuenen when he described winter’s bleak trees in the garden of his father’s vicarage.

Antwerp and Paris: 1885–88 After a short, frustrating effort to conform to the standards of the Antwerp art academy, Van Gogh headed for Paris to move in with his brother Theo and to study at Fernand Cormon’s atelier, where he met fellow students Toulouse-Lautrec , Émile Bernard, and John Russell. In the French capital (March 1886–February 1888), Van Gogh came in contact with many of the avant-garde artists of the era, including Pissarro, Seurat, Signac, and Gauguin . He awakened to the bright palette of the Impressionists , the pointillist touch of the Neo-Impressionists , and the novelties of imported Japanese prints . Like so many of his most advanced contemporaries, he put aside the practice of drawing to paint in short, semigraphic strokes. In focusing his sights on the city and its suburbs, he kept pace with current trends and found scenery that reminded him of home.

Sojourn in Arles: February 1888–May 1889 After two years in Paris, Van Gogh longed for a sunny retreat where he could “recover and regain [his] peace of mind and self-composure.” In February 1888, he headed south to the town of Arles. He hoped to attract other colleagues to his “Studio of the South,” but aside from Gauguin’s fateful stay that fall, Van Gogh spent most of his fifteen-month sojourn alone. His Provençal outpost did not guarantee the fellowship he craved, but instead afforded him the distance necessary for his art to come into his own.

In Arles, Van Gogh depended largely on pen and paper for feedback and dialogue. Drawing, like writing, regained the importance it had held for him earlier in the Netherlands and once again became a staple of his working practice. He discovered in the reed pen—which he made from local hollow-barreled grass, sharpened with a penknife—a drawing tool entirely sympathetic to his aims: easy to acquire and use, bold and incisive in his statement. In turn, he set out to do “an ENORMOUS amount of drawing,” armed with the means to produce works in line that were as compelling as those in color. Casting aside the traditional roles accorded to drawing and painting, Van Gogh fully realized the creative potential of both.

Répétitions : Drawings after Paintings While living apart from the mainstream, Van Gogh routinely relied on his drawings—small sketches in his letters as well as full-fledged sheets—to give his family and friends a sense of his recent work. In Provence, he exploited old strategies in novel ways. During the summer of 1888, while his latest oil paintings were tacked up on the walls of his studio to dry, he devoted three weeks to reproducing them in thirty-two pen-and-ink drawings that he sent to fellow artists Émile Bernard and John Russell, and to his brother Theo.

Van Gogh selected and crafted the images with each of the recipients clearly in mind. With these successive suites of drawings, he hoped to elicit an exchange of works with Bernard, to win over the recalcitrant Russell as a prospective patron for Gauguin, and to report his progress to Theo.

None of his drawings is a slavish copy—far from it. Van Gogh used the opportunity to reconsider and reinvigorate his original conceptions in a series of richly inventive linear improvisations.

Taking Asylum in Saint-Rémy: May 1889–May 1890 Van Gogh spent a year as a voluntary patient at the asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole in Saint-Rémy. Under the care of doctors (who diagnosed his illness as a form of epilepsy), the artist forged ahead, the pace of his accomplishment slowed only by hospital restrictions, recurrent attacks, and depleted or embargoed art supplies. These challenges did not defeat his creative spirit, but spurred it on. When he was unable to paint, he resorted to his drawing tools, sometimes in novel combinations with whatever materials he had on hand.

The drawings Van Gogh produced during this period are stylistically diverse and richly inventive. Those in color—like his contemporaneous paintings—succeed in wedding expressive line to color, synthesizing the breakthroughs he had achieved in Arles with inimitable ingenuity.

Auvers: May–June 1890 Van Gogh checked himself out of the asylum at Saint-Rémy on May 16, 1890, and headed north to the town of Auvers, not far from Paris, where he could live close to Theo and be cared for by Dr. Paul Gachet, a collector and amateur artist. Enchanted by the quaint hamlet and refreshed by the quality of the northern light, Van Gogh responded with a new palette of blues and greens carried by rhythmic, undulating lines. In seventy days he produced nearly seventy-five paintings and fifty drawings—mostly quick sketches.

Van Gogh’s career came to an abrupt end when he died on July 29, 1890, from a self-inflicted gunshot wound. By the time of his death, the paintings he had shown in recent exhibitions in Paris and Brussels had begun to command the interest of artists and critics. Prospects looked even brighter for Van Gogh’s work as a draftsman—as one writer boldly predicted: “It may be certain that in the future the artist who died young will receive attention primarily for his drawings.”

Ives, Colta, and Susan Alyson Stein. “Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890): The Drawings.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/gogh_d/hd_gogh_d.htm (October 2005)

Further Reading

Brooks, David. Vincent van Gogh: The Complete Works . CD-ROM. Sharon, Mass.: Barewalls Publications, 2002.

Dorn, Roland, et al. Van Gogh Face to Face: The Portraits . New York: Thames & Hudson, 2000.

Druick, Douglas W., et al. Van Gogh and Gauguin: The Studio of the South . Exhibition catalogue. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2001.

Ives, Colta, et al. Vincent van Gogh: The Drawings. Exhibition catalogue . New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005. See on MetPublications

Kendall, Richard. Van Gogh's Van Gogh's: Masterpieces from the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam . Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1998.

The Complete Letters of Vincent van Gogh . 3 vols. Boston: Bullfinch Press, 2000.

Pickvance, Ronald. Van Gogh in Arles . New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1984. See on MetPublications

Pickvance, Ronald. Van Gogh in Saint-Rémy and Auvers . New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1986. See on MetPublications

Selected and edited by Ronald de Leeuw. The Letters of Vincent van Gogh . London: Penguin, 2006.

Stein, Susan Alyson, ed. Van Gogh: A Retrospective . New York: New Line Books, 2006.

Stolwijk, Chris, and Richard Thomson. Theo van Gogh . Amsterdam: Van Gogh Museum, 1999.

Additional Essays by Colta Ives

- Ives, Colta. “ The Printed Image in the West: Aquatint .” (October 2003)

- Ives, Colta. “ The Print in the Nineteenth Century .” (October 2004)

- Ives, Colta. “ Japonisme .” (October 2004)

- Ives, Colta. “ Lithography in the Nineteenth Century .” (October 2004)

Related Essays

- Paul Gauguin (1848–1903)

- Post-Impressionism

- Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890)

- Frans Hals (1582/83–1666)

- Georges Seurat (1859–1891) and Neo-Impressionism

- Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901)

- Impressionism: Art and Modernity

- Nineteenth-Century French Realism

- The Print in the Nineteenth Century

- Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669): Prints

- The Transformation of Landscape Painting in France

List of Rulers

- List of Rulers of Europe

- Central Europe and Low Countries, 1800–1900 A.D.

- France, 1800–1900 A.D.

- 19th Century A.D.

- Arboreal Landscape

- French Literature / Poetry

- Impressionism

- Low Countries

- Neo-Impressionism

- The Netherlands

- Oil on Canvas

- Pointillism

- Printmaking

- Self-Portrait

Artist or Maker

- Daumier, Honoré

- Gauguin, Paul

- Millet, Jean-François

- Pissarro, Camille

- Seurat, Georges

- Signac, Paul

- Toulouse-Lautrec, Henri de

- Van Gogh, Vincent

- Van Rijn, Rembrandt

Online Features

- The Artist Project: “Sopheap Pich on Vincent van Gogh’s drawings”

- Connections: “Dutch” by Merantine Hens

Vincent van Gogh

Vincent van Gogh was one of the world’s greatest artists, with paintings such as ‘Starry Night’ and ‘Sunflowers,’ though he was unknown until after his death.

(1853-1890)

Who Was Vincent van Gogh?

Vincent van Gogh was a post-Impressionist painter whose work — notable for its beauty, emotion and color — highly influenced 20th-century art. He struggled with mental illness and remained poor and virtually unknown throughout his life.

Early Life and Family

Van Gogh was born on March 30, 1853, in Groot-Zundert, Netherlands. Van Gogh’s father, Theodorus van Gogh, was an austere country minister, and his mother, Anna Cornelia Carbentus, was a moody artist whose love of nature, drawing and watercolors was transferred to her son.

Van Gogh was born exactly one year after his parents' first son, also named Vincent, was stillborn. At a young age — with his name and birthdate already etched on his dead brother's headstone — van Gogh was melancholy.

Theo van Gogh

The eldest of six living children, van Gogh had two younger brothers (Theo, who worked as an art dealer and supported his older brother’s art, and Cor) and three younger sisters (Anna, Elizabeth and Willemien).

Theo van Gogh would later play an important role in his older brother's life as a confidant, supporter and art dealer.

Early Life and Education

At age 15, van Gogh's family was struggling financially, and he was forced to leave school and go to work. He got a job at his Uncle Cornelis' art dealership, Goupil & Cie., a firm of art dealers in The Hague. By this time, van Gogh was fluent in French, German and English, as well as his native Dutch.

He also fell in love with his landlady's daughter, Eugenie Loyer. When she rejected his marriage proposal, van Gogh suffered a breakdown. He threw away all his books except for the Bible, and devoted his life to God. He became angry with people at work, telling customers not to buy the "worthless art," and was eventually fired.

Life as a Preacher

Van Gogh then taught in a Methodist boys' school, and also preached to the congregation. Although raised in a religious family, it wasn't until this time that he seriously began to consider devoting his life to the church

Hoping to become a minister, he prepared to take the entrance exam to the School of Theology in Amsterdam. After a year of studying diligently, he refused to take the Latin exams, calling Latin a "dead language" of poor people, and was subsequently denied entrance.

The same thing happened at the Church of Belgium: In the winter of 1878, van Gogh volunteered to move to an impoverished coal mine in the south of Belgium, a place where preachers were usually sent as punishment. He preached and ministered to the sick, and also drew pictures of the miners and their families, who called him "Christ of the Coal Mines."

The evangelical committees were not as pleased. They disagreed with van Gogh's lifestyle, which had begun to take on a tone of martyrdom. They refused to renew van Gogh's contract, and he was forced to find another occupation.

Finding Solace in Art

In the fall of 1880, van Gogh decided to move to Brussels and become an artist. Though he had no formal art training, his brother Theo offered to support van Gogh financially.

He began taking lessons on his own, studying books like Travaux des champs by Jean-François Millet and Cours de dessin by Charles Bargue.

Van Gogh's art helped him stay emotionally balanced. In 1885, he began work on what is considered to be his first masterpiece, "Potato Eaters." Theo, who by this time living in Paris, believed the painting would not be well-received in the French capital, where Impressionism had become the trend.

Nevertheless, van Gogh decided to move to Paris, and showed up at Theo's house uninvited. In March 1886, Theo welcomed his brother into his small apartment.

In Paris, van Gogh first saw Impressionist art, and he was inspired by the color and light. He began studying with Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec , Camille Pissarro and others.

To save money, he and his friends posed for each other instead of hiring models. Van Gogh was passionate, and he argued with other painters about their works, alienating those who became tired of his bickering.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S VINCENT VAN GOGH FACT CARD

Van Gogh's love life was nothing short of disastrous: He was attracted to women in trouble, thinking he could help them. When he fell in love with his recently widowed cousin, Kate, she was repulsed and fled to her home in Amsterdam.

Van Gogh then moved to The Hague and fell in love with Clasina Maria Hoornik, an alcoholic prostitute. She became his companion, mistress and model.

When Hoornik went back to prostitution, van Gogh became utterly depressed. In 1882, his family threatened to cut off his money unless he left Hoornik and The Hague.

Van Gogh left in mid-September of that year to travel to Drenthe, a somewhat desolate district in the Netherlands. For the next six weeks, he lived a nomadic life, moving throughout the region while drawing and painting the landscape and its people.

Van Gogh became influenced by Japanese art and began studying Eastern philosophy to enhance his art and life. He dreamed of traveling there, but was told by Toulouse-Lautrec that the light in the village of Arles was just like the light in Japan.

In February 1888, van Gogh boarded a train to the south of France. He moved into a now-famous "yellow house" and spent his money on paint rather than food.

Vincent van Gogh completed more than 2,100 works, consisting of 860 oil paintings and more than 1,300 watercolors, drawings and sketches.

Several of his paintings now rank among the most expensive in the world; "Irises" sold for a record $53.9 million, and his "Portrait of Dr. Gachet" sold for $82.5 million. A few of van Gogh’s most well-known artworks include:

'Starry Night'

Van Gogh painted "The Starry Night" in the asylum where he was staying in Saint-Rémy, France, in 1889, the year before his death. “This morning I saw the countryside from my window a long time before sunrise, with nothing but the morning star, which looked very big,” he wrote to his brother Theo.

A combination of imagination, memory, emotion and observation, the oil painting on canvas depicts an expressive swirling night sky and a sleeping village, with a large flame-like cypress, thought to represent the bridge between life and death, looming in the foreground. The painting is currently housed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, NY.

'Sunflowers'

Van Gogh painted two series of sunflowers in Arles, France: four between August and September 1888 and one in January 1889; the versions and replicas are debated among art historians.

The oil paintings on canvas, which depict wilting yellow sunflowers in a vase, are now displayed at museums in London, Amsterdam, Tokyo, Munich and Philadelphia.

In 1889, after entering an asylum in Saint-Rémy, France, van Gogh began painting Irises, working from the plants and flowers he found in the asylum's garden. Critics believe the painting was influenced by Japanese woodblock prints.

French critic Octave Mirbeau, the painting's first owner and an early supporter of Van Gogh, remarked, "How well he has understood the exquisite nature of flowers!"

'Self-Portrait'

Over the course of 10 years, van Gogh created more than 43 self-portraits as both paintings and drawings. "I am looking for a deeper likeness than that obtained by a photographer," he wrote to his sister.

"People say, and I am willing to believe it, that it is hard to know yourself. But it is not easy to paint yourself, either. The portraits painted by Rembrandt are more than a view of nature, they are more like a revelation,” he later wrote to his brother.

Van Gogh's self-portraits are now displayed in museums around the world, including in Washington, D.C., Paris, New York and Amsterdam.

Van Gogh's Ear

In December 1888, van Gogh was living on coffee, bread and absinthe in Arles, France, and he found himself feeling sick and strange.

Before long, it became apparent that in addition to suffering from physical illness, his psychological health was declining. Around this time, he is known to have sipped on turpentine and eaten paint.

His brother Theo was worried, and he offered Paul Gauguin money to go watch over Vincent in Arles. Within a month, van Gogh and Gauguin were arguing constantly, and one night, Gauguin walked out. Van Gogh followed him, and when Gauguin turned around, he saw van Gogh holding a razor in his hand.

Hours later, van Gogh went to the local brothel and paid for a prostitute named Rachel. With blood pouring from his hand, he offered her his ear, asking her to "keep this object carefully."

The police found van Gogh in his room the next morning, and admitted him to the Hôtel-Dieu hospital. Theo arrived on Christmas Day to see van Gogh, who was weak from blood loss and having violent seizures.

The doctors assured Theo that his brother would live and would be taken good care of, and on January 7, 1889, van Gogh was released from the hospital.

He remained, however, alone and depressed. For hope, he turned to painting and nature, but could not find peace and was hospitalized again. He would paint at the yellow house during the day and return to the hospital at night.

Van Gogh decided to move to the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence after the people of Arles signed a petition saying that he was dangerous.

On May 8, 1889, he began painting in the hospital gardens. In November 1889, he was invited to exhibit his paintings in Brussels. He sent six paintings, including "Irises" and "Starry Night."

On January 31, 1890, Theo and his wife, Johanna, gave birth to a boy and named him Vincent Willem van Gogh after Theo's brother. Around this time, Theo sold van Gogh's "The Red Vineyards" painting for 400 francs.

Also around this time, Dr. Paul Gachet, who lived in Auvers, about 20 miles north of Paris, agreed to take van Gogh as his patient. Van Gogh moved to Auvers and rented a room.

On July 27, 1890, Vincent van Gogh went out to paint in the morning carrying a loaded pistol and shot himself in the chest, but the bullet did not kill him. He was found bleeding in his room.

Van Gogh was distraught about his future because, in May of that year, his brother Theo had visited and spoke to him about needing to be stricter with his finances. Van Gogh took that to mean Theo was no longer interested in selling his art.

Van Gogh was taken to a nearby hospital and his doctors sent for Theo, who arrived to find his brother sitting up in bed and smoking a pipe. They spent the next couple of days talking together, and then van Gogh asked Theo to take him home.

On July 29, 1890, Vincent van Gogh died in the arms of his brother Theo. He was only 37 years old.

Theo, who was suffering from syphilis and weakened by his brother's death, died six months after his brother in a Dutch asylum. He was buried in Utrecht, but in 1914 Theo's wife, Johanna, who was a dedicated supporter of van Gogh's works, had Theo's body reburied in the Auvers cemetery next to Vincent.

Theo's wife Johanna then collected as many of van Gogh's paintings as she could, but discovered that many had been destroyed or lost, as van Gogh's own mother had thrown away crates full of his art.

On March 17, 1901, 71 of van Gogh's paintings were displayed at a show in Paris, and his fame grew enormously. His mother lived long enough to see her son hailed as an artistic genius. Today, Vincent van Gogh is considered one of the greatest artists in human history.

Van Gogh Museum

In 1973, the Van Gogh Museum opened its doors in Amsterdam to make the works of Vincent van Gogh accessible to the public. The museum houses more than 200 van Gogh paintings, 500 drawings and 750 written documents including letters to Vincent’s brother Theo. It features self-portraits, “The Potato Eaters,” “The Bedroom” and “Sunflowers.”

In September 2013, the museum discovered and unveiled a van Gogh painting of a landscape entitled "Sunset at Montmajour.” Before coming under the possession of the Van Gogh Museum, a Norwegian industrialist owned the painting and stored it away in his attic, having thought that it wasn't authentic.

The painting is believed to have been created by van Gogh in 1888 — around the same time that his artwork "Sunflowers" was made — just two years before his death.

Watch "Vincent Van Gogh: A Stroke of Genius" on HISTORY Vault

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Vincent van Gogh

- Birth Year: 1853

- Birth date: March 30, 1853

- Birth City: Zundert

- Birth Country: Netherlands

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Vincent van Gogh was one of the world’s greatest artists, with paintings such as ‘Starry Night’ and ‘Sunflowers,’ though he was unknown until after his death.

- Astrological Sign: Aries

- Brussels Academy

- Nacionalities

- Interesting Facts

- Some of van Gogh's most famous works include "Starry Night," "Irises," and "Sunflowers."

- In a moment of instability, Vincent Van Gogh cut off his ear and offered it to a prostitute.

- Van Gogh died in France at age 37 from a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

- Death Year: 1890

- Death date: July 29, 1890

- Death City: Auvers-sur-Oise

- Death Country: France

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Vincent van Gogh Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/artists/vincent-van-gogh

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: March 4, 2020

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- As for me, I am rather often uneasy in my mind, because I think that my life has not been calm enough; all those bitter disappointments, adversities, changes keep me from developing fully and naturally in my artistic career.

- I am a fanatic! I feel a power within me…a fire that I may not quench, but must keep ablaze.

- I get very cross when people tell me that it is dangerous to put out to sea. There is safety in the very heart of danger.

- I want to paint what I feel, and feel what I paint.

- As my work is, so am I.

- The love of art is the undoing of true love.

- When one has fire within oneself, one cannot keep bottling [it] up—better to burn than to burst. What is in will out.

- For my part I know nothing with any certainty, but the sight of the stars makes me dream.

- I do not say that my work is good, but it's the least bad that I can do. All the rest, relations with people, is very secondary, because I have no talent for that. I can't help it.

- What is wrought in sorrow lives for all time.

- What I draw, I see clearly. In these [drawings] I can talk with enthusiasm. I have found a voice.

- Enjoy yourself too much rather than too little, and don't take art or love too seriously.

- But I always think that the best way to know God is to love many things.

Famous Painters

11 Notable Artists from the Harlem Renaissance

Fernando Botero

Gustav Klimt

The Surreal Romance of Salvador and Gala Dalí

Salvador Dalí

Margaret Keane

Andy Warhol

Table of Contents

Director’s Foreword - Emilie E. S. Gordenker

Preface - Joost van der Hoeven

Introductory Essay: The Genesis of the Collection of Art Assembled by Theo and Vincent van Gogh - Joost van der Hoeven

Notes to the Reader

Contributors

Credits and Terms of Use

Acknowledgements

Emile Bernard

Fisherman and Boat

Fragment of a Venus (recto), Figures in a Street (verso)

Breton Woman with Child

Boy Sitting in the Grass

Vase of Flowers and Cup

Portrait of Bernard's Grandmother

Brothel Scenes

Breton Watercolours

Adoration of the Shepherds

Drawings Sent to Van Gogh in September 1888

Self-Portrait with Portrait of Gauguin

Albert Besnard

The Parting

Eugène Boch

The Mine Crachet-Picquery in Frameries, Borinage

Théophile de Bock

Paintings and Drawings

Frank Meyers Boggs

Honfleur Harbour and Coal Barges on the Thames

George Hendrik Breitner

Girl in the Grass

Vittorio Matteo Corcos

Portrait of a Young Woman

Honoré Daumier

Man on Horseback

Jean Louis Forain

Prints from the Series Croquis parisiens

Paul Gauguin

The Mango Trees, Martinique

On the Banks of the River, Martinique

Study of a Martinican Woman

Study for the painting Breton Girls Dancing, Pont-Aven (recto), Sketch of a Flower Still Life (verso)

Study of a Woman Seen from the Back

Self-Portrait with Portrait of Emile Bernard (Les misérables)

Study Sheet with Portraits of Camille Roulin

Portrait of Joseph-Michel Ginoux

Vincent van Gogh Painting Sunflowers

Cleopatra Pot

Leo Marie Gausson

The Church Tower of Bussy-Saint-Georges

Armand Guillaumin

Self-Portrait with Palette and Portrait of a Young Woman

Meijer de Haan

Portrait of Theo van Gogh

Portrait of a Bearded Man

Hans Heyerdahl

Joseph jacob isaacson, arnold koning, charles laval.

Self-Portrait

Edouard Manet

Portrait of a Lady

Sientje Mesdag-van Houten

Still Life with Fruit

Adolphe Monticelli

Christian mourier-petersen.

Tulip Field

Camille Pissarro

Landscape with Rainbow (Paysage avec arc-en-ciel)

Ernest Quost

Garden with Hollyhocks and The New Season

Jean-François Raffaëlli

Odilon redon.

In Heaven or Closed Eyes

John Peter Russell

Portrait of Vincent van Gogh and Female Nude

Paul van Ryssel

Portrait of Vincent van Gogh on His Deathbed

Georges Seurat

Eden Concert

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Two Prostitutes in a Café

Young Woman at a Table, 'Poudre de riz'

Portrait of Vincent van Gogh

Victor Alfred Paul Vignon

Entry details

Works Collected by Theo and Vincent van Gogh

The Genesis of the Collection of Art Assembled by Theo and Vincent van Gogh

Introductory essay by joost van der hoeven.

An art collection is seldom a perfect reflection of the wishes of the collector. Budgetary constraints and coincidence can be just as important to a collection as determination and vision. Luck is often a major factor, and this was certainly true of the art collection assembled by Theo (1857–1891) and Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) between around 1880 and 1890. The brothers’ distinct tastes and passion for collecting were inevitably curbed to some extent by their limited financial means. Even though Theo had a decent job at the Paris art dealership of Goupil & Cie, which became Boussod, Valadon & Cie in 1884, he was from a young age the mainstay of the family, and this was a significant drain on his resources. After Vincent decided to become an artist in 1880, he lived on an allowance from Theo, who also sent money to their mother after the death of their father, Theodorus, in 1885. 01 Starting in early 1881, in fact, Theo gradually took over this responsibility from his father. Open footnotes panel Their younger siblings Willemien and Cor, who still lived at home, likewise depended on Theo’s support. 02 See Vincent van Gogh, letter to Theo van Gogh, between 21 and 26 August 1885 [530 ] , n. 3. Open footnotes panel Yet this lack of funds did not prevent Vincent and Theo from making shrewd purchases, and they added to their modest holdings by exchanging Vincent’s paintings for the work of other artists. 03 Although the exact provenance of many works in the collection is not known, we know for certain that at least fifteen paintings were purchased, as well as some nine drawings. With regard to the prints, it is also difficult to say whether they were purchased, although this was probably true of most of them. Open footnotes panel Although swapping artworks proved to be an effective means of acquisition, a collection built up in this way was subject to arbitrariness. By no means could the brothers always choose which works they were given in exchange, nor did they have much say in the various works they received as gifts. 04 For example, when Vincent van Gogh exchanged Sunflowers (1887, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) and Sunflowers (1887, Kunstmuseum, Bern) for one of Gauguin’s Martinican paintings in late 1887 or early 1888, he did not know at the time which work Gauguin would select for him. See On the Banks of the River, Martinique . In the case of The Mine Crachet-Picquery in Frameries, Borinage by Eugène Boch, which also entered the collection through an exchange, Theo chose the work and Vincent could not influence his decision. See The Mine Crachet-Picquery in Frameries, Borinage. Open footnotes panel

Despite these limitations, however, the brothers were able to form a sizeable collection, of which some eighty paintings, more than seventy-five drawings and over seventy prints are still preserved in the Van Gogh Museum, which means the collection has stayed largely intact. 05 See n. 222. Open footnotes panel The collection contains work by artists who are now considered among the greatest of the avant-garde, including Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), Georges Seurat (1859–1891) and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901), as well as the work of artists who have since been forgotten. Most of them belonged to Vincent and Theo’s immediate circle and were still relatively unknown, which was true of Vincent too. Their work was not expensive, so the brothers could afford it, but it took vision and boldness for them to stake their money on these avant-garde artist friends whose future was uncertain. Thanks to their keen eye and instinctive discernment, Theo and Vincent were able to acquire a varied collection with a large number of pieces that have earned a place in the canon of modern European art.

An introduction to this collection is obliged to point out that the Van Gogh brothers did not collect merely out of a love of art. Around 1885, Theo conceived a plan to set up his own art dealership, and with this in mind, both he and Vincent began to see their collection as stock in trade for their future gallery. 06 Theo’s attempts to become an independent art dealer are discussed later in this essay. Open footnotes panel Because the brothers planned to devote themselves to promoting artists whom they admired, their acquisitions were based on personal tastes and commercial considerations, which largely coincided. 07 Theo van Gogh, letter to Jo Bonger, 26 July 1887, in Leo Jansen, Jan Robert and Han van Crimpen (eds.), Brief Happiness: The Correspondence of Theo van Gogh and Jo Bonger , Amsterdam & Zwolle 1999, no. 1: ‘I had several artists in mind whose work I admired & with whom I was sure I could do business.’ For the original Dutch, see Kort geluk: De briefwisseling tussen Theo van Gogh en Jo Bonger , Amsterdam & Zwolle 1999, no. 1: ‘Ik had verschillende artis-ten in t’oog waarvan het werk mijne bewondering opwekte & waarmede ik zeker was zaken te kunnen doen.’ Hereafter both the original Dutch text and its English translation will be indicated by Jansen, Robert and Van Crimpen 1999. Open footnotes panel As far as we know, Theo made two – unsuccessful – attempts to set himself up in business. When he died in 1891, the entire collection came into the hands of Theo’s heirs: Jo van Gogh-Bonger (1862–1925) and their son, Vincent Willem van Gogh (1890–1978). A chronology of the collection’s genesis – inasmuch as it is possible to establish – gives rise to an interesting picture of the brothers’ evolving tastes and their steadily expanding network of contacts, thereby augmenting previous publications on the collection, chief among them the exhibition catalogue Theo van Gogh, 1857–1891: Art Dealer, Collector and Brother of Vincent (1999). 08 Chris Stolwijk and Richard Thomson (eds.), with a contribution by Sjraar van Heugten, Theo van Gogh, 1857–1891: Art Dealer, Collector and Brother of Vincent , exh. cat., Amsterdam (Van Gogh Museum) / Paris (Musée d’Orsay), Amsterdam & Zwolle 1999. Open footnotes panel That catalogue, though, breaks down the history of the collection according to the various methods of acquisition, without paying much attention to the brothers’ evolving tastes and widening network. Moreover, that publication and many others make Theo’s role seem disproportionately large, whereas both Vincent and Theo played vital roles in building up the collection. The frequent question as to which works belonged to whom is therefore irrelevant. In their letters, the brothers often referred to ‘our’ collection and the works that ‘we’ have acquired. 09 Vincent van Gogh, letter to Theo van Gogh, 15 July 1888 [640 ] : ‘But it’s not my business, after all, but our personal stock, that I do value’ (‘Mais enfin cela ne me regarde pas mais à notre depot personel j’y tiens’); Theo van Gogh, letter to Anna Cornelia van Gogh-Carbentus, July/August 1886 (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation), inv. no. b0942V1962): ‘He has not yet sold any paintings for money, but exchanges his work for other paintings. In this way we’re acquiring a fine collection, which is also worth something, of course.’ (‘Hij heeft nog geen schilderijen tegen geld verkocht, maar ruilt zijn werk tegen andere schilderijen in. Zoo krijgen wij een mooie verzameling, die ook natuurlijk wat waard is.’) Open footnotes panel The collection is actually the product of the brothers’ ongoing artistic dialogue, which began in their teenage years and continued – in both face-to-face conversations and letters – until Vincent’s death in 1890.

The prelude: collecting reproductive prints

Long before the brothers acquired their first painting or drawing, they were actively engaged in collecting reproductive prints and magazine illustrations. The low prices of black-and-white reproductions of works by famous artists in such techniques as wood engraving, line engraving and autotype actually made collecting an affordable undertaking and provided the brothers with an excellent opportunity to discover, by degrees, their artistic predilections. Collecting reproductive prints can therefore be seen as the prelude to collecting one-of-a-kind drawings and paintings, even though the brothers still had no clear-cut goal when they embarked on their collection of graphic art. 10 At first the prints they owned were simply a collection, but once Vincent had decided to become an artist, they served as a point of reference and source of inspiration for his own work. See Hans Luijten, ‘Rummaging among My Woodcuts: Van Gogh and the Graphic Arts’, in Chris Stolwijk et al. (eds.), Vincent’s Choice: The Musée imaginaire of Van Gogh , exh. cat., Amsterdam (Van Gogh Museum) 2003, pp. 99–112. See also Fleur Roos Rosa de Carvalho, ‘Uplifting, Not Lofty: Vincent and Theo van Gogh’s Collection of Reproductions and Illustrations’, in Lisa Smit and Hans Luijten (eds.), Choosing Vincent: From Family Collection to Van Gogh Museum , exh. cat., Amsterdam (Van Gogh Museum), Bussum 2023, pp. 42–67. Open footnotes panel

Vincent began to collect reproductive prints in 1869, at the age of sixteen, after becoming the youngest employee at the Hague branch of Goupil & Cie, an art dealership with headquarters in Paris. At its height, the firm also had branches in Brussels, London, Berlin and New York. His appointment had been arranged by his uncle Vincent van Gogh (Uncle Cent), a partner in the firm since 1858. 11 Vincent van Gogh (1820–1888) set up a shop for art supplies in The Hague that later developed into an art dealership. Its success made it eligible for a merger with Goupil & Cie and Vincent thus became a partner in the firm. See Jan Hulsker, Lotgenoten: het leven van Vincent en Theo van Gogh , Weesp 1985, p. 25. Open footnotes panel Although Goupil & Cie increasingly developed into a gallery that sold paintings and drawings, its core business was the trade and production of prints after important works of contemporary art. 12 John Rewald, ‘Theo van Gogh, Goupil and the Impressionists’, Gazette des Beaux-Arts 81 (January–February 1973), pp. 1–2. Open footnotes panel Such reproductions were immensely popular among art lovers and therefore a lucrative line of business. During Vincent’s time at the gallery, thousands of prints must have passed through his hands, fostering a desire to own such reproductions himself. No doubt he was further stimulated by the art collections of both Uncle Cent and Uncle Cor (Cornelis Marinus van Gogh), who was also active in the art trade. 13 Regarding the collection of Uncle Vincent van Gogh, see the posthumous sale of his holdings, Tableaux modernes: collection de feu M. Vincent van Gogh de Princenhage , Pulchri Studio, The Hague, 2 and 3 April 1889. On Cornelis (Cor) Marinus van Gogh, see Vincent van Gogh, letter to Theo van Gogh, 28 January 1873 [004 ] : ‘Last Sunday I was at Uncle Cor’s and had a very pleasant day there and, as you can well imagine, saw many beautiful things. As you know, Uncle has just been to Paris and has brought home splendid paintings and drawings.’ (‘Verl. Zondag ben ik bij Oom Cor geweest & heb daar een heel prettigen dag gehad & zoo als je denken kunt veel moois gezien. Zooals je weet is Oom pas naar Parijs geweest & heeft prachtige schilderijen & teekeningen mede gebracht.’) In addition to Uncle Cent and Uncle Cor (1824–1908), Vincent and Theo had a third uncle who was active in the art trade: Hendrik Vincent van Gogh (Uncle Hein, 1814–1877). Open footnotes panel

Vincent was glad that he could share his passion for art and collecting reproductions with his brother Theo, his junior by four years. Theo, who began his career at Goupil’s Brussels branch on 1 January 1873, at the age of fifteen, had barely started work when Vincent wrote to him: ‘You must write to me in particular about what kind of paintings you see and what you find beautiful.’ 14 Chris Stolwijk, ‘Theo van Gogh: A Life’, in Stolwijk and Thomson 1999, p. 22; Vincent van Gogh, letter to Theo van Gogh, mid-January 1873 [003 ] : ‘Ge moet mij vooral schrijven wat je al zoo voor schilderijen ziet & wat je mooi vindt.’ Open footnotes panel This marked the beginning of an intense correspondence in which Vincent and Theo frequently exchanged ideas about art. Both brothers were transferred a number of times, but they never worked together at the same branch of Goupil. 15 In May 1873, Vincent was transferred to the London branch and in May 1875 to Paris, where he was dismissed on 1 April 1876. Theo was transferred from Brussels to The Hague in November 1873, and from there to Paris in November 1879. Open footnotes panel The written word thus remained their primary means of communication, and in this Vincent took the lead. As the older brother, he was determined to help Theo develop good taste. Theo thus received in January 1874 a list of the artists whom Vincent found interesting. This list betrays his eclectic taste, which ranged from landscapes to religious subjects and from then ‘modern’ artists, including Camille Corot (1796–1875) and Jan Hendrik Weissenbruch (1824–1903), to academic painters like Ernest Meissonier (1815–1891) and romantics such as Barend Cornelis Koekkoek (1803–1862). Vincent did not care about an artist’s nationality. 16 See Vincent van Gogh, letter to Theo van Gogh, beginning of January 1874 [017 ] . Open footnotes panel This wide-ranging, international approach is also apparent in the collection the brothers eventually built up, although not all of the above mentioned artists are represented in their holdings. 17 The brothers acquired artist’s prints by Corot and Weissenbruch. Neither Koekkoek nor Meissonier were ever represented in their collection. Open footnotes panel

Vincent often told Theo about paintings on offer in the gallery and exhibitions he had seen. Gradually he developed distinct preferences. 18 See, for example, Vincent van Gogh, letter to Theo van Gogh, London, between 4 January and 5 March 1875 [029 ] : ‘Our gallery is now finished and it’s beautiful, we have many beautiful things at the moment: Jules Dupré, Michel, Daubigny, Maris, Israëls, Mauve, Bisschop, &c. [ …] There’s a beautiful exhibition of old art here, including a large Descent from the Cross by Rembrandt, 5 large figures at twilight, you can imagine the sentiment. 5 Ruisdaels, 1 Frans Hals, Van Dyck. A landscape with figures by Rubens, a landscape, an autumn evening, by Titian.’ (‘Onze galery is nu klaar & is mooi, wij hebben veel moois op t’oogenblik: Jules Dupré, Michel, Daubigny, Maris, Israels, Mauve, Bisschop, &c. [ …] Er is eene mooie tentoonstelling van oude kunst hier; o.a. eene groote afneming van het kruis van Rembrandt, 5 groote figuren, in de schemering, ge kunt denken wat een sentiment. 5 Ruysdaels, 1 Frans Hals, van Dyck, een landschap met figuren van Rubens, een landschap, herfstavond, van Titiaan.’) Open footnotes panel He often discussed the work of the painters of Barbizon and those of the Hague School, but he also told Theo about the art of the Old Masters, such as Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669), Frans Hals (1582/3–1666) and Jacob van Ruisdael (1628/9–1682). Vincent’s ideas largely concurred with both current Dutch tastes and the art on offer at Goupil’s. His favourite artist was Jean-François Millet (1814–1875). After seeing an exhibition of Millet’s drawings in Paris in 1875, he wrote to Theo: ‘felt something akin to: Put off thy shoes from off thy feet, for the place whereon thou standest is holy ground’. 19 Vincent van Gogh, letter to Theo van Gogh, 29 June 1876 [036 ] : ‘ [ Ik] voelde zoo iets van: Neem Uw schoenen van uwe voeten, want de plek waar gij staat is heilig land.’ Open footnotes panel

Scrapbook of Magazine Illustrations, Reproductive Prints and Photographic Reproductions, 167 prints in various techniques, pasted on paper and bound in an album, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Theo moves to Paris

Around 1 November 1879, Theo was transferred to Paris, where he took up a position at Goupil & Cie at 19 boulevard Montmartre, one of their three branches in the French capital. The other two were situated at 9 rue Chaptal and 2 place de l’Opéra, both more prestigious locations. Evidently Theo did a good job, because in early 1881 he was appointed branch manager ( gérant ). It cannot be a coincidence that around the time of this promotion, Theo began to acquire original artworks, such as drawings, artist’s prints and paintings. At this point the brothers still had no well-defined ideas about a joint collection; Theo’s early purchases were mainly for himself.

While it is true that Theo now had more money to spend, Vincent had meanwhile decided to become an artist and had no income of his own. The funds put aside for Vincent’s allowance represented a considerable drain on Theo’s income. He earned between 11,000 and 14,000 francs a year, an amount that consisted of a monthly salary and a yearly commission of 7.5 per cent of his branch’s profit. 23 Chris Stolwijk et al. (eds.), The Account Book of Theo van Gogh and Jo van Gogh-Bonger , Leiden & Amsterdam 2002, pp. 11, 15–16. Open footnotes panel On average, 14.5 per cent of Theo’s total income went to Vincent. 24 Jansen, Luijten and Bakker, ‘Biographical and Historical Backgrounds: The Financial Backgrounds’ , accessed 30 November 2022. Open footnotes panel

Léon-Augustin Lhermitte, April , 1859, lithograph in black on wove paper, 25.1 × 34.9 cm, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Theo also bought two paintings by the Norwegian artist Hans Heyerdahl (1857–1913), whose work had been on offer at Goupil’s since 1881. 34 See the entry on the paintings and drawings of Hans Heyerdahl. Open footnotes panel He paid 250 francs for Portrait of a Girl with a Bunch of Flowers and Park , both produced in 1882. 35 Receipt for two paintings from Goupil & Cie to Theo van Gogh, c. 1882–c. 1885 (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation), inv. no. b1332V1962). These are the only paintings of which it can be said for certain that Theo bought them through his employer. Open footnotes panel For these two works, which are modest in size, Theo paid the market price. 36 A Head of a Young Girl ( Tête de Jeune fille ), for example, was sold at Goupil’s for 250 francs. The work was registered on 3 September 1881, but there is no record of when it was sold. Goupil Stock Book 10, page 181, row 11, stock no. 15618, Getty Provenance Index. Open footnotes panel Unlike Theo’s previous purchases, Heyerdahl did not represent a continuation of the direction the brothers had taken with their collection of reproductive prints. Theo had become acquainted with Heyerdahl in Paris and had written to Vincent about him. From Vincent’s reaction, we may assume that Theo had expressed enthusiasm for Heyerdahl’s work and had praised his ‘proportions for the purpose of design’. 37 Vincent van Gogh, letter to Theo van Gogh, 2 April 1881 [164 ] : ‘You speak of Heyerdahl as one who takes great pains to seek “proportions for the purpose of design”, that’s precisely what I need.’ (‘Gij spreekt van Heyerdahl als van iemand die zich veel moeite geeft om “verhoudingen voor teekening” te zoeken, dat is juist wat ik noodig heb.’) Open footnotes panel Heyerdahl’s work was rather sentimental, and in terms of style it was somewhere between naturalism and impressionism. Theo must have found it exciting to buy the work of a totally ‘new’ artist.

First gifts

Not only did Theo’s promotion mean an increase in salary, but his new position also gave him higher standing, which had a positive influence on the collection that he and Vincent were forming. His dealings as branch manager were crucial to the commercial success of the artists whose work Goupil dealt in. Theo’s network steadily grew, as evidenced by his surviving address books and notebooks, which are filled with the names of influential artists, critics and collectors, including Edgar Degas (1834–1917), Félix Fénéon (1861–1944) and Georges de Bellio (1826–1894). 38 Theo van Gogh’s address book, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation), inv. no. b2947V1962. See also Ronald de Leeuw and Fieke Pabst, ‘Le carnet d’adresses de Theo van Gogh’, in Françoise Cachin and Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov, Van Gogh à Paris, exh. cat., Paris (Musée d’Orsay) 1988, pp. 348–69. Other notebooks belonging to Theo, which likewise contain addresses, are also to be found in the collection of the Van Gogh Museum: b4166V1962, b4167V1962 and b4168V1962. An album of portrait photographs of acquaintances (b4417V1962) also survives. Open footnotes panel Theo’s new position therefore made it more likely that artists would make him a gift of their work. This is probably how he acquired, in the first years after his promotion, the watercolour Girl in the Grass by George Hendrik Breitner (1857–1923), who hoped, through Theo, to have his work shown at one of Goupil’s Paris branches. 39 See Lili Jampoller, ‘Theo and Vincent as Art Collectors’, in Evert van Uitert and Michael Hoyle (eds.), The Rijksmuseum Vincent van Gogh , Amsterdam 1987, p. 31. Open footnotes panel As he wrote to Theo: ‘For my part, I hope to send you something soon. Would you see a chance to place sketches of nudes by me?’ 40 George Hendrik Breitner, letter to Theo van Gogh, c. 1887 (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation), inv. no. b1331V1962): ‘Ik voor mij hoop je spoedig wat te sturen. Zou je ook kans zien naaktschetsen van mij te plaatsen.’ Open footnotes panel Breitner probably sent him the watercolour to strengthen their relations. It did not have the desired effect, however: Breitner’s work was not sold at Goupil & Cie until after Theo’s death, and then only at the Hague branch. 41 The Getty Provenance Index includes no entry of Breitner’s work prior to 1893, which was two years after Theo’s death. Open footnotes panel

The Italian artist Vittorio Corcos (1859–1933) made a similar gift in 1884, even though he was not hoping to be promoted by Theo. Instead, he was thanking him for services rendered. From the time he took up his position at Goupil’s in Paris until his death in 1891, more than ninety works by Corcos were sold. 42 See Getty Provenance Index. Open footnotes panel On Portrait of a Young Woman , intended for Theo, he wrote: ‘A m. Th. Van Gogh / souvenir de Corcos’. A work in the collection by Albert Besnard , who served more or less the same market as the fashionable Corcos, was presumably given to Theo with similar strategic motives.

Marie Désiré Bourgoin, Landscape with a Woman and a Goat , 1883, pen and brush and black ink and white transparent watercolour on cardboard, 17.2 × 26.6 cm, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Theo’s burgeoning interest in modern art

An interesting question is the extent to which Theo’s evolving taste in art was influenced by his new cosmopolitan life in Paris. In the early 1880s, Goupil was anything but a beacon of the new developments in painting. The firm mainly sold the work of established artists, such as the painters of Barbizon (most of whom had meanwhile died) and the Hague School. 43 See Richard Thomson, ‘Theo van Gogh: An Honest Broker’, in Stolwijk, and Thomson (eds.) 1999, pp. 69–78. Open footnotes panel Their paintings – primarily landscapes – were still popular, but so was the work of such Academy painters as Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904) and William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825–1905). The work of Lhermitte and Jules Breton (1827–1906), who belonged to the second generation of French naturalist painters, likewise sold well, as did the work of society painters such as Giuseppe de Nittis (1846–1884) and the previously mentioned Corcos. 44 Ibid. Open footnotes panel Theo must have admired much of the work that passed through his hands; his purchase of two paintings by Heyerdahl can be seen as confirmation of this. After all, this Norwegian artist was an affordable alternative to fashionable, more expensive French work, such as that of Jean Béraud (1849–1935). As emerges from the brothers’ correspondence, Vincent, too, admired many of these popular artists. 45 See, for instance, letters [017 ] , [039 ] , [156 ] and [333 ] , all four of which were written by Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh. Open footnotes panel

At the same time, Theo was well informed about developments outside Goupil’s, where the modern art of the impressionists was steadily gaining in popularity. At the Impressionist Exhibitions in 1880, 1881 and 1882, for example, Theo could have become familiar with the work of Claude Monet (1840–1926), Edgar Degas (1834–1917), Camille Pissarro (1830–1903), Mary Cassatt (1844–1926) and Berthe Morisot (1841–1895), among others. In 1883, several of these artists were given solo exhibitions at the gallery of Paul Durand-Ruel, and not long after that, Georges Petit, Goupil’s most important competitor, ventured to exhibit a few impressionist works at his luxurious and fashionable gallery. 46 Petit first exhibited work by Degas in 1884 at the show Le sport dans l’art , which ran from 14 December 1884 to 31 January 1885. Work by Monet was first exhibited in 1885, at the 4ème Exposition de peinture , which opened on 15 May of that year. Ten of his canvases were shown at that time. See Pierre Sanchez, Les expositions de la galerie Georges Petit (1881–1934): répertoire des artistes et liste de leurs œuvres , Dijon 2011, pp. 607, 1407–8. Open footnotes panel

Theo must have taken an interest in the impressionists, because in 1883 he made his first, cautious purchase of an impressionist work for his collection. Instead of choosing a more distinctive work by Monet, Degas or Pissarro, he selected a painting by Victor Vignon (1847–1909), an artist who had exhibited a number of times at the impressionist shows and who often collaborated with Pissarro. 47 Vignon’s work was shown at the Impressionist Exhibitions of 1880, 1881, 1882 and 1886. Open footnotes panel Vignon was more conservative than his more prominent colleagues; stylistically, he was midway between Pissarro and Daubigny. His work was affordable and in the same price range as the paintings of Pissarro, who was still finding it difficult to sell his work at the beginning of the 1880s. Vignon’s work sold better, which must have been why Theo found it safer as a first step in this new direction. He paid 200 francs for either Woman in a Vineyard or Winter Landscape , it is not certain which. 48 Henri Guérard, letter to Theo van Gogh, 24 January 1883 (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation), inv. no. b1177V1962). The receipt from Henri Guérard, who acted as a dealer or middleman, explicitly records one painting, whereas both of the paintings mentioned in the text were to be found in the collection (and a third was added in April 1890). It is not known which of the two works was acquired in 1883, nor is it known how the second work entered the collection. Perhaps Theo received it as a gift when he bought the other work. See the entry for Woman in a Vineyard , Winter Landscape and View of a Town . Open footnotes panel

In 1884, Theo bought an impressionist painting for his branch of Boussod, Valadon & Cie, and this time he did choose a Pissarro. The sales ledgers record a small work titled Landscape ( Paysage ), which was purchased for 125 francs and subsequently sold with a profit of only 25 francs. 49 Goupil Stock Book 11, page 101, row 10, stock no. 16994, Getty Provenance Index. Open footnotes panel In the following year, Theo sold works by Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919) and Alfred Sisley (1839–1899) – one painting by each of those artists. 50 Monet: Goupil Stock Book 11, page 128, row 14, stock no. 17401; Renoir: Goupil Stock Book 11, page 129, row 7, stock no. 17409; Sisley: Goupil Stock Book 11, page 128, row 14, stock no. 17401, Getty Provenance Index. Open footnotes panel That was it, as far as the impressionists were concerned, because his employers were not keen on the new art. 51 Maurice Joyant, who was Theo’s successor at Boussod, Valadon & Cie’s branch at 19 boulevard Montmartre, wrote a monograph on Toulouse-Lautrec in 1926 in which he recorded his recollection of a conversation with Léon Boussod about Theo. Boussod reportedly said: ‘He has accumulated appalling things by modern painters which are the shame of the firm.’ (‘Il a accumulé des choses affreuses de peintres modernes qui sont le déshonneur de la maison.’) See Maurice Joyant, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec , Paris 1926, p. 118. Open footnotes panel With the exception of the work by Sisley, Theo acquired the impressionist works from third parties, which means that he was not yet in direct contact with Pissarro, Monet or Renoir.

It is quite conceivable that during this period of new discoveries, Theo began to buy the work of the leading impressionists for his own collection. An inventory of the estate, drawn up after Theo’s death for a fire insurance policy, lists two paintings by Renoir and one by Pissarro. 52 Jo van Gogh-Bonger’s fire insurance policy, list of artworks (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation), inv. no. b4557V1982). Open footnotes panel In 1899, Theo’s widow, Jo van Gogh-Bonger, sold these works to the art dealer Ambroise Vollard, after which no paintings by these artists remained in the estate. 53 Stolwijk, Veenenbos and Van Heugten 2002, p. 199. Open footnotes panel Sisley’s work was attainable and affordable for Theo, in part because he was in direct contact with the artist, but he seems not to have taken a real interest in it. 54 In 1885, Sisley’s painting was the only work that had come directly from the artist, which implies personal contact. The sales ledger records its provenance as ‘Artiste’ . See Goupil Stock Book 11, page 128, row 14, stock no. 17401, Getty Provenance Index. Open footnotes panel And although Theo held the art of Monet and Degas in high esteem, their high prices prevented him from buying it. 55 With regard to Monet, for example, see Theo van Gogh, letter to Jo Bonger, 9 and 10 February 1889, in Jansen, Robert and Van Crimpen 1999, no. 41: ‘There is light & life, often bright sunshine, in all the paintings [ by Monet] on display, & each picture evokes the sentiments that nature itself would inspire. The colours have a certain richness.’ (‘In aIle schilderijen [ van Monet] die er zijn tentoongesteld is licht & leven, dikwijls felle zon, & men gevoelt in elk schilderij de sensatie die de natuur zelf ook zou teweeg gebracht hebben. Wat kleur aan-gaat is er iets rijks in.’) As regards Degas, for instance, see Theo van Gogh, letter to Willemien van Gogh, 14 March 1890 (Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation), inv. no. b0927V1962): ‘I just got an old painting by Degas that he sold to me, which portrays an itinerant girl of Auvergne. It is something. There is something so pure and fresh in that figure, without even remotely lapsing into sentimentality, that it’s almost as tranquil as a Greek statue.’ (‘Ik heb juist een oud schilderij van Degas, dat hij mij verkocht heeft dat een rondreizend meisje van Auvergne voorstelt. Dat is zoo iets. Er zit zoo iets reins en frisch in dat figuurtje zonder in de verste verte in sentimentaliteit te vervallen dat het haast zoo kalm is als een grieksch beeld.’) The work by Monet that Theo acquired for Goupil in 1885 was sold for 800 francs. See Goupil Stock Book 11, page 128, row 14, stock no. 17401, Getty Provenance Index. With regard to Degas, At the Milliner’s (1882, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) was purchased in 1882 for 2,000 francs by Durand-Ruel, who sold the work that same year for at least 3,500 francs. See Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, Splendid Legacy: The Havemeyer Collection , New York 1993, p. 335. Open footnotes panel

Much has been written about Theo as a dealer in impressionist paintings, in particular by John Rewald in 1973 and Richard Thomson in 1999. 56 John Rewald, ‘Theo van Gogh, Goupil and the Impressionists’, Gazette des Beaux-Arts 81 (January–February 1973) and Richard Thomson, ‘Theo van Gogh: An Honest Broker’, in Stolwijk, Thomson and Van Heugten 1999. Open footnotes panel Rewald called Theo a hero for his reputed altruism in choosing to deal in art of this kind, whereas Thomson maintains that Theo did nothing more than go with the flow of the art market. The truth probably lies somewhere in the middle: Theo’s dealings in 1884–85, as well as what he bought for his own collection, reveal that he was moving towards the impressionists on his own initiative and that his personal taste was becoming considerably more modern.

In the same period, Theo no doubt wrote enthusiastically to Vincent about the impressionists, because the term occurs frequently in their correspondence from 1884 onwards. Vincent thus had high expectations of this style of painting when he set off for Paris in 1886. 57 Vincent van Gogh, letter to Willemien van Gogh, between 16 and 20 June 1888 [620 ] : ‘People have heard of the Impressionists, they have great expectations of them [ …] and when they see them for the first time they’re bitterly, bitterly disappointed and find them careless, ugly, badly painted, badly drawn, bad in colour, everything that’s miserable. That was my first impression, too, when I came to Paris with the ideas of Mauve and Israëls and other clever painters.’ (‘Men heeft van de impressionisten gehoord, men stelt er zich veel van voor en [ …] als men ze voor t’eerst ziet is men bitter en bitter teleurgesteld en vindt het slordig, leelijk, slecht geschilderd, slecht geteekend, slecht van kleur, al wat miserabel is. Dat was mijn eigen eerste indruk ook toen ik met de idees van Mauve en Israels en andere knappe schilders in Parijs kwam.’) Open footnotes panel When he finally saw the work of the impressionists, it took him a while – and quite some effort – before he could bring himself to admire it. This shows that the roles of the brothers were briefly reversed, with regard to the formation of their artistic tastes, and that Theo was taking the lead in introducing his older brother to new developments in painting. In fact, this was not so surprising, given that Theo was leading a cosmopolitan life in Paris, whereas Vincent was striving to be a ‘peasant painter’ in rural Brabant.

Nevertheless, Theo must have been frustrated by the limitations imposed on him by his employers with regard to trading in impressionist art, and this made him reflect on his future with the firm. Instead of continuing on the path prescribed by Boussod, Valadon & Cie, Theo would have liked to go into business for himself, in order to focus on modern art with no outside interference. It is possible that he thought of the first impressionist paintings he had acquired as potential stock in trade, even though it was by no means enough. Together with his good friend Andries Bonger, whom he had met several years earlier in Paris, he devised a plan to approach Uncle Cent and Uncle Cor and ask them to invest in his business. 58 Theo van Gogh, letter to Jo Bonger, 26 July 1887, in Jansen, Robert and Van Crimpen 1999, no. 1: ‘As you know, 1 was thinking about setting myself up at the time. I had several artists in mind whose work I admired & with whom I was sure I could do business. Andre shared my views & we arranged that I would approach my uncle, who had once promised to help me, to get the money we needed to carry out our plan & start a business together.’ (‘Zooals ge weet was er toen kwestie van dat ik mij zou zijn gaan vestigen. Ik had verschillende artisten in t'oog waarvan het werk mijne bewondering opwekte & waarmede ik zeker was zaken te kunnen doen. Andre deelde mijn gevoelen & wij kwamen overeen dat ik zou trachten bij mijn Oom, die mij in der tijd zijne hulp had toegezegd, het noodige geld te krijgen om aan ons plan gevolg te geven & samen zaken te beginnen.’) Open footnotes panel Vincent was also closely involved in the plan. 59 See Vincent van Gogh and Andries Bonger, letter to Theo van Gogh, c. 18 August 1886 [568 ] . Open footnotes panel Theo made the request in the summer of 1886, while visiting his uncles during a vacation in the Netherlands. But they saw nothing in the plan, thinking it too risky to invest in impressionist paintings. 60 Theo van Gogh, letter to Jo Bonger, 26 July 1887, in Jansen, Robert and Van Crimpen 1999, no. 1: ‘My uncle refused to help & fobbed me off, kindly at first, but later, when I persisted, quite firm.’ (‘Mijn Oom weigerde mij te helpen & scheepte mij eerst met vriendelijke, later toen ik aandrong met harde woorden af.’) Open footnotes panel Theo was deeply disappointed but continued to harbour a desire to strike out on his own. From this time on, the brothers’ acquisitions were driven not just by their love of art but also by the hope of future profits. 61 [568 ] n. 2; Jansen, Robert and Van Crimpen 1999, Introduction, p. 18, and Letter 1, pp. 63–64. Open footnotes panel

Prints by Raffaëlli, Forain and Manet

It is remarkable that in the case of Degas, Theo did not turn his attention to his drawings or prints, both of which were less expensive and more readily available than his paintings. This was not so much the case with Monet, who presented himself mainly as a painter. Nevertheless, there are several modern artists whose prints Theo did buy: Jean-François Raffaëlli (1850–1924), Jean-Louis Forain (1852–1931) and Edouard Manet (1832–1883). It is not known exactly when Theo made these purchases, but because the brothers often corresponded about Raffaëlli and Manet in 1884 and 1885, it is conceivable that their prints were acquired in this period.

The illustrated edition of Huysmans’s novel also contained work by Forain, who produced six prints, which, together with Raffaëlli’s, were available in a collector’s edition. 65 Marcel Guérin, J.-L. Forain, aquafortiste: catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre gravé de l’artiste , San Francisco 1980, nos. 15–21. Open footnotes panel It was this edition that Theo bought. The combination of these two artists was telling, for although they were both chroniclers of contemporary Parisian life, they recorded it from different perspectives. Forain specialized in scenes of nightlife, whereas Raffaëlli concentrated on the working classes. Both extremes of life in Paris were exhaustively described in Huysmans’s book.

Edouard Manet, The Smoker , 1866, oil on canvas, 100.3 × 81.3 cm, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Gift of Bruce B. Dayton

Manet’s large retrospective exhibition – held at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1884, the year after his death – therefore featured 116 paintings and, by comparison, only 21 etchings and 5 lithographs. 69 Anonymous, Exposition des œuvres de Edouard Manet , with preface by Emile Zola, exh. cat., Paris (École Nationale des Beaux-Arts) 1884. Open footnotes panel Vincent, then living in Nuenen, was extremely interested in this exhibition, particularly because he had already seen so much of the artist’s work during his time at Goupil’s in Paris (1875–76). 70 See Vincent van Gogh, letter to Theo van Gogh, c. 3 February 1884 [428 ] . Open footnotes panel He asked Theo for a detailed description of the show and a list of the works on display. 71 Ibid. Open footnotes panel It included numerous paintings of which Manet had also made prints, such as The Spanish Singer and Lola de Valence (1862, Musée d’Orsay, Paris), both of which Theo had bought. The acquisition of Manet’s prints was no doubt due in part to the high price of his paintings. The artist’s death in 1883 and the compelling retrospective not long afterwards drove up the price of his paintings far beyond Theo’s budget. 72 For example, the painting The Spanish Singer (1860, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) was sold in 1873 for 7,000 francs. See under ‘Provenance’, accessed 13 December 2022. Open footnotes panel The fact that Manet saw his prints as fully fledged works of art certainly added to the brothers’ appreciation of his etchings.

In addition to these prints, Theo bought Manet’s drawing Portrait of a Lady . It is not known when he made this purchase. In contrast to his great personal interest in the artist, Theo sold only a handful of Manets at the gallery. In 1886 he sold a seascape, but after that it was years before the artist’s name recurred in the sales ledgers of Boussod, Valadon & Cie. When Vincent moved to Paris that same year, he was finally able to see the prints and Theo’s other acquisitions with his own eyes and admire them at first hand. After Vincent’s arrival, Theo’s taste began to incline even more towards the avant-garde.

Vincent comes to Paris

In late February 1886, Vincent joined Theo in Paris and moved into his small apartment at 25 rue Laval. From the moment of his arrival, he began to participate in their collecting activities. We can be sure that he voiced his opinion of Theo’s previous purchases and that he now became actively involved in acquisitions. The artistic exchanges in their letters, which by this time spanned a period of thirteen years, could now take place uninterrupted in their shared accommodation. For the first time, they could visit exhibitions together and discuss the art they had seen.

Vincent enabled them to expand the collection considerably through the exchange of his work. At first these swaps were intended not so much to enrich the collection as to enlarge Vincent’s incipient Paris network, which was one of his main objectives in the first months after his arrival in the metropolis. 73 Louis van Tilborgh, ‘The History of the Collection: Exchanges, Gifts, Sales and the Sacrosanct Core’, in Ella Hendriks and Louis van Tilborgh (eds.), Vincent van Gogh: Paintings , vol. 2: Antwerp and Paris, 1885–1888 , Amsterdam 2011, p. 19. Open footnotes panel He enrolled, for instance, in Fernand Cormon’s (1845–1924) atelier libre (‘free studio’), where he not only strove to develop his skills as an artist but also met many other painters. Moreover, through Theo he became acquainted with several art dealers who were willing to exhibit work he had painted specially for the market, such as flower still lifes and townscapes. 74 Vincent van Gogh, letter to Horace Mann Livens, September or October 1886 [569 ]: ‘At this present moment I have found four dealers who have exhibited studies of mine.’ These dealers were Pierre Firmin-Martin (1817–1891), Georges Thomas (?–1908), Julien Tanguy (1825–1894) and probably Alphonse Portier (1841–1902); see Van Tilborgh 2011, pp. 18–19. Open footnotes panel

Fabian, View from Montmartre, c. 1886, oil on panel, 12.6 × 21.6 cm, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

Six paintings by Monticelli

In their admiration of Monticelli, Theo and Vincent found a kindred spirit in the Scot Alexander Reid, who had arrived in Paris with hopes of becoming an artist, but a lack of talent had prompted him to turn his attention to the art trade. Reid worked for Theo at the gallery on the boulevard Montmartre, and from December 1886 or thereabouts he lived for six months with Theo and Vincent. 81 Frances Fowle, Van Gogh’s Twin: The Scottish Art Dealer Alexander Reid , Edinburgh 2010, pp. 26–29. Open footnotes panel Reid was well informed about the demand for Monticelli’s work in Britain, which only increased after the painter’s death on 29 June 1886. Reid tried in a personal capacity (which was allowed at Boussod, Valadon & Cie) to buy up large numbers of Monticellis from Delarebeyrette, among others, with a view to selling them at much higher prices on the British market. 82 Frances Fowle, ‘Vincent’s Scottish Twin: The Glasgow Art Dealer Alexander Reid’, Van Gogh Museum Journal , 2000, pp. 92–94. Open footnotes panel Owing in part to his close collaboration with Reid, Theo succeeded in November 1886 in selling no fewer than eleven paintings by Monticelli to the London art dealer Charles Obach, Vincent’s former boss at Goupil’s, who had struck out on his own in 1884. For this transaction Theo had bought up, on Boussod’s behalf, twelve Monticellis, one of which, Italian Girl , was offered to him as a bonus for the sale. 83 Goupil Stock Book 11, page 177, rows 5–6, stock nos. 18125–18126, Getty Provenance Index. Recorded in L’Italienne : ‘Offert par M. Boussod à M. Van Gogh.’ Open footnotes panel Thus the first work by this highly sought-after artist entered the brothers’ collection at no cost to themselves, which must have been a source of great satisfaction.

On 19 March 1887, Theo managed – probably in collaboration with Reid – to buy nine more paintings by Monticelli at Delarebeyrette’s, which he likewise sold on to Obach. 84 Goupil Stock Book 11, page 196, rows 7–15, stock nos. 18412–18420, Getty Provenance Index. Open footnotes panel In May of that year he bought a further six, again from Delarebeyrette; these he sold to the London art dealership Dowdeswell & Dowdeswell, one of Reid’s contacts. 85 Goupil Stock Book 11, page 203, row 12, stock nos. 18522; page 204, row 2, stock no. 18527, Getty Provenance Index. Open footnotes panel In 1887, Theo – following the example of Reid, who by this time had been living with the brothers for around three months – bought four paintings by Monticelli from Delarebeyrette for his and Vincent’s collection, presumably thinking that they would sell them for a profit. 86 Vincent van Gogh, letter to Theo van Gogh, c, 24 February 1888 [578 ] : ‘Reid made Monticellis go up in value, and since we own 5 of them the result for us is that these paintings have increased in value.’ (‘Reid a fait monter les Monticelli de valeur et puisqu’on en possède 5 il en résulte pour nous que ces tableaux ont haussé en tant que valeur.’) The four works that Theo bought from Delarebeyrette are Meeting in the Park (c. 1877), Arabian Horseman (1871), Woman at the Well (1870–71) and Woman with a Parasol (c. 1879). See entry Paintings by Monticelli. Open footnotes panel These works were never sold, however, and they consequently remained in the collection. Yet this clearly shows that Theo continued to seek possibilities to go into business for himself, and that he and Vincent now approached their acquisitions not only as art lovers but also as future dealers.

Vincent van Gogh, Portrait of Alexander Reid , c. 1887, oil on panel, 41 × 33 cm, Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art, Norman, Oklahoma, Aaron M. and Clara Weitzenhoffer Bequest, 2000

Towards the end of Vincent’s stay in Paris, feelings of competition between the brothers and Reid must have arisen. They reproached him for letting commercial considerations cloud his aesthetic judgement; for them, after all, the trade in Monticelli’s work had been prompted not merely by commercial interests but also by artistic convictions. 90 Vincent van Gogh, letter to John Russell, 19 April 1888 [598 ] : ‘So much to say that I consider the dealer STRONGER in him [ Reid] than THE ARTIST though there be a battle in his conscience concerning this – of the which [ sic ] battle I do not yet know the result.’ Open footnotes panel One minor reason for Vincent’s departure for the south of France in early 1888 was his determination to get there before Reid, to prevent him from buying up all the paintings from Monticelli’s heirs. 91 Vincent van Gogh, letter to Theo van Gogh, c. 24 February 1888 [578 ] : ‘As far as Reid goes, I wouldn’t be very surprised if – (wrongly, however) – he took it badly that I went to the south before him.’ (‘Pour ce qui est de Reid je serais peu étonné de ce qu’– (à tort pourtant) – il prît de mauvaise part que je l’aie dévancé dans le midi.’) Open footnotes panel It never came to this, but it illustrates Vincent’s passionate involvement in collecting and trading art.

Even though Theo never actually sold any paintings by Monticelli for his own profit, in 1890 he made renewed efforts, on behalf of Boussod, Valadon & Cie, to enhance the artist’s reputation. He did this by collaborating with the lithographer Auguste Lauzet (1865–1898) to produce a series of twenty lithographs after paintings by Monticelli. 92 Sheon 2000, p. 53. Open footnotes panel Theo expected the album to sell well, especially among his British clientele. 93 See Theo van Gogh, letter to Vincent van Gogh, 8 December 1889 [825 ] . Open footnotes panel He was still very interested and had great confidence in the graphic arts. It is no coincidence that the series contains two lithographs after paintings from their own collection. 94 Sheon 2000, pp. 54–55. Open footnotes panel Clearly, Theo’s strategy for increasing Monticelli’s popularity and the price of his work was not only in the interest of his employer; it would also be in his own interest if he were to become an independent dealer.

Interest in avant-garde artists