- Exemplar IEP Transition Plans

New Hampshire exemplars

The Parent Information Center (PIC) and the New Hampshire Department of Education worked together to develop two exemplar IEP transition plans, Ryan and Sarah. Both IEPs are included in the Life After High School Transition Toolkit (PDF, 80 pages, 2018) from PIC.

Heidi Wyman, NH-based transition consultant, developed a Transition Planning Worksheet (PDF, 3 pages, 2020) that looks like the NHSEIS IEP to use in transition conversations with students and families.

Ryan will graduate at age 21 with a certificate of attendance. His employment goal is to become a state trooper. His annual goals include steps to test the viability of that goal.

Ryan’s NH IEP transition plan

Examples of measureable annual goals and a chart to help build them.

Sarah will graduate with a regular high school diploma and plans to attend a 4-year college to major in a field related to writing.

Sarah’s NH IEP transition plan

Jamarreo will graduate with a regular high school diploma and plans to attend a community college to obtain a welding certificate.

Jamarreo’s transition plan

National exemplars

The National Technical Assistance Center on Transition (NTACT) developed case study collection with a cross-section of gender, ages, and disability categories. Note that you may have to set up a free account to view the case studies.

Several of the case studies contain examples and non-examples of measurable postsecondary goals and annual goals.

Allison has a specific learning disability in reading comprehension and written expression, and organizational challenges. She would like to attend a four-year college and major in child development.

Allison’s case study

Lilly has severe multiple mental and physical disabilities who likes to be around people. She receives specially designed instruction with an alternate curriculum in a separate school setting.

Lilly’s case study

Lissette is a 20 year old student with Down Syndrome and plans to complete a certificate program in food service.

Lissette’s case study

Alex is a 17 year old student with autism spectrum disorder who would like to continue working in the business department of an office supply store, and may need employment supports.

Alex’s case study

Chris is a 19 year old senior with emotional disturbance and a moderate hearing loss. He has interests in welding and auto body.

Chris’s case study

Aaliyah is a 17 year old sophomore with a mild to moderate hearing loss detected in third grade.

Aaliyah’s case study

Jamal is a 16 year old sophomore with cerebral palsy and an orthopedic impairment. He would like to become a lawyer.

Jamal’s case study

Connor is an 18 year old senior with a profound hearing loss. He would like to attend a 4-year college and become a graphic designer.

Connor’s case study

Sean is a 15 year old sophomore with a specific learning disability in mathematics and language processing. He’s interested in diesel mechanics.

Sean’s case study

Middle School

NTACT also offers two exemplars for middle school students.

Tyler is 13 years old and in 7th grade, with a specific learning disability in reading comprehension and written expression.

Tyler’s case study

Carla is almost 14 years old and in 8th grade, with a moderate intellectual disability.

Carla’s case study

Updated 10-27-22

Transition IEP General Help

- Introduction

- About Indicator 13

- Video Shorts on Transition IEPs

- Operationalizing Student Voice in the IEP (PDF)

Transition IEP Requirements

- NH Indicator 13 Checklist (PDF)

- Postsecondary Goals

- Transition Assessments

- Transition Services

- Course of Study

- Annual Goals

- Student Invitation

- Invitation to Participating Agency

Additional Resources

- Requirements placement in IEP (PDF)

- Blank IEP form from NHSEIS (PDF)

- NH DOE Indicator 13 Compliance Guidance (PDF, 15 pages, Aug 2023)

- NH DOE Indicator 13 webpage

Case Studies

Bridges, William with Bridges, Susan. Chapter 2: “A Test Case” in Managing Transitions: Making the Most of Change. 1991, 2003, 2019, 2017.

“we think in generalities, but we live in detail.” .

—Alfred North Whitehead, British philosopher

Case Study 1: Software Company

Taken from: Managing Transitions: Making the Most of Change, Chapter 2.

Chapter 1 of Managing Transitions: Making the Most of Change was fairly theoretical. Unless you understand the basic transition model, you won’t be able to use it. But only in actual situations can you use it, so let’s look at a situation that I encountered in a software company. I was brought in because the service manager wanted to make some changes, and his staff was telling him it wasn’t going to be as easy as he thought.

He told me that he didn’t see why that should be so. The change made perfect sense, and it was also necessary for the firm’s continued leadership in the field of business software for banks. “Besides,” he said, “no one’s going to lose a job or anything like that.”

Bearing in mind what you read in chapter 1, see what you think.

The company’s service unit did most of its business over the telephone. Individual technicians located in separate cubicles fielded callers’ questions. The company culture was very individualistic. Not only were employees referred to as “individual contributors,” but each was evaluated based on the number of calls he or she disposed of in a week. At the start of each year a career evaluation plan was put together for each employee in which a target (a little higher than the total of the previous year’s weekly numbers) was set. To hit the target brought you a bonus. To miss it cost you that bonus.

Purchasers of the company’s big, custom software packages called to report various kinds of operating difficulties, and the calls were handled by people in three different levels. First the calls went to relatively inexperienced individuals, who could answer basic questions. They took the calls on an availability basis. If the problem was too difficult for the first level, it went to the second tier. Technicians at that level had more training and experience and could field most of the calls, but if they couldn’t take care of a problem, they passed it on to someone on the third level. The “thirds” were programmers who knew the system from the ground up and could, if necessary, tell the client how to reprogram the software to deal with the problem.

Each tier of the service unit was a skill-based group with its own manager, who was responsible for managing the workload and evaluating the performance of the individual contributors. Not surprisingly, there was some rivalry and mistrust among the different levels, as each felt that its task was the pivotal one and that the others didn’t pull their weight.

As you may have surmised, there were several inherent difficulties with this system. First, customers never got the same person twice unless they remembered to ask. Worse yet, there was poor coordination among the three levels. A level-one technician never knew to whom he was referring a customer—or sometimes even whether anyone at the next level actually took over the customers when he passed them on. Customers were often angry at being passed around rather than being helped.

Managers were very turf-conscious, and this didn’t improve coordination. Sometimes the second-tier manager announced that all the “seconds” were busy—although this was hard to ascertain because each technician was hidden in a cubicle—and then the service would go on hold for a day (or even a week) while the seconds caught up with their workload. In the meantime, the frustrated customer might have called back and found that he had to start over again and explain the problem to a different first-tier worker.

Not only were customers passed along from one part of the service unit to another, but sometimes they were “mislaid” entirely. The mediocre (at best) level of customer satisfaction hadn’t been as damaging when the company had no real competition, but when another company launched an excellent new product earlier that year, it spelled trouble.

The general manager of the service unit brought in a service consultant, who studied the situation and recommended that the unit be reorganized into teams of people drawn from all three of the levels. (This reorganization is what in the last chapter I called the change.) A customer would be assigned to a team, and the team would have the collective responsibility of solving the customer’s problem. Each team would have a coordinator responsible for steering the customer through the system of resources. Everyone agreed: the change ought to solve the problem.

The change was explained at a unit-wide meeting, where large organization charts and team diagrams lined the walls. Policy manuals were rewritten, and the team coordinators—some of whom had been level managers and some of whom were former programmers—went through a two-day training seminar. The date for the reorganization was announced, and each team met with the general manager, who told them how important the change was and how important their part was in making it work.

Although there were problems when the reorganization occurred, no one worried too much, because there are always problems with change. But a month or so later it became clear that the new system not only wasn’t working but didn’t even exist except on paper. The old levels were still entrenched in everyone’s mind, and customers were still being tossed back and forth (and often dropped) without any system of coordination. The coordinators maintained their old ties with people from their former groups and tended to try to get things done with the help of their old people (even when those people belonged to another team) rather than by their team as a whole.

Imagine that you’re brought in to help them straighten out this tangle. What would you do? Because we can’t discuss the possibilities face to face, I will give you a list of actions that might be taken in such a situation. Scan them and see which sound like good ideas to you. Then go back through the list slowly and put a number by each item, assigning it to one of the following five categories:

1 = Very important. Do this at once. 2 = Worth doing but takes more time. Start planning it. 3 = Yes and no. Depends on how it’s done. 4 = Not very important. May even be a waste of effort. 5 = No! Don’t do this.

Fill in those numbers before you read further, and take your time. This is not a simple situation, and solving it is a complicated undertaking.

Possible Actions to Take

- Explain the changes again in a carefully written memo.

- Figure out exactly how individuals’ behavior and attitudes will have to change to make teams work.

- Analyze who stands to lose something under the new system.

- Redo the compensation system to reward compliance with the changes.

- “Sell” the problem that is the reason for the change.

- Bring in a motivational speaker to give employees a powerful talk about teamwork.

- Design temporary systems to contain the confusion during the cutover from the old way to the new.

- Use the interim between the old system and the new to improve the way in which services are delivered by the unit—and, where appropriate, create new services.

- Change the spatial arrangements so that the cubicles are separated only by glass or low partitions.

- Put team members in contact with disgruntled clients, either by phone or in person. Let them see the problem firsthand.

- Appoint a “change manager” to be responsible for seeing that the changes go smoothly.

- Give everyone a T-shirt with a new “teamwork” logo on it.

- Break the change into smaller stages. Combine the firsts and seconds, then add the thirds later. Change the managers into coordinators last.

- Talk to individuals. Ask what kinds of problems they have with “teaming.”

- Change the spatial arrangements from individual cubicles to group spaces.

- Pull the best people in the unit together as a model team to show everyone else how to do it.

- Give everyone a training seminar on how to work as a team.

- Reorganize the general manager’s staff as a team and reconceive the GM’s job as that of a coordinator.

- Send team representatives to visit other organizations where service teams operate successfully.

- Turn the whole thing over to the individual contributors as a group and ask them to come up with a plan to change over to teams.

- Scrap the plan and find one that is less disruptive. If that one doesn’t work, try another. Even if it takes a dozen plans, don’t give up.

- Tell them to stop dragging their feet or they’ll face disciplinary action.

- Give bonuses to the first team to process 100 client calls in the new way.

- Give everyone a copy of the new organization chart.

- Start holding regular team meetings.

- Change the annual individual targets to team targets, and adjust bonuses to reward team performance.

- Talk about transition and what it does to people. Give coordinators a seminar on how to manage people in transition.

Category 1: Very important. Do this at once.

Figure out exactly how individuals’ behavior and attitudes will have to change to make teams work. To deal successfully with transition , you need to determine precisely what changes in their existing behavior and attitudes people will have to make. It isn’t enough to tell them that they have to work as a team. They need to know how teamwork differs behaviorally and attitudinally from the way they are working now. What must they stop doing, and what are they going to have to start doing? Be specific. Until these changes are spelled out, people won’t be able to understand what you tell them.

Analyze who stands to lose something under the new system. This step follows the previous one. Remember, transition starts with an ending. You can’t grasp the new thing until you’ve let go of the old thing. It’s this process of letting go that people resist, not the change itself. Their resistance can take the form of foot-dragging or sabotage, and you have to understand the pattern of loss to be ready to deal with the resistance and keep it from getting out of hand.

“Sell” the problem that is the reason for the change. Most managers and leaders put 10% of their energy into selling the problem and 90% into selling the solution to the problem. People aren’t in the market for solutions to problems they don’t see, acknowledge, and understand. They might even come up with a better solution than yours, and then you won’t have to sell it—it will be theirs.

Put team members in contact with disgruntled clients, either by phone or in person. Let them see the problem firsthand. This is part of selling the problem. As long as you are the only one fielding complaints, poor service is going to be your problem, no matter how much you try to get your subordinates to acknowledge its importance. To engage their energies, you must make poor service their problem. Client visits are the best opportunity for people to see how their operation is perceived by its customers. DuPont has used this program very successfully in a number of its plants. Under its “Adopt a Customer” program, blue-collar workers are sent to visit customers once a month and bring what they learn back to the factory floor.

Talk to individuals. Ask what kinds of problems they have with “teaming.” When an organization is having trouble with change, managers usually say they know what is wrong. But the truth is that often they don’t. They imagine that everyone sees things as they do, or they make assumptions about others that are untrue. You need to ask the right questions. If you ask, “Why aren’t you doing this?” you’ve set up an adversarial relation and will probably get a defensive answer. If, on the other hand, you ask, “What problems are you having with this?” you’re likelier to learn why it isn’t happening.

Talk about transition and what it does to people. Give coordinators a seminar on how to manage people in transition. Everyone can benefit from understanding transition. A coordinator will deal with subordinates better if he or she understands what they are going through. If they understand what transition feels like, team members will feel more confident that they haven’t taken a wrong turn. They’ll also see that some of their problems come from the transition process and not from the details of the change. If they don’t understand transition, they’ll blame the change for what they are feeling.

Start holding regular team meetings. Even before you can change the space to fit the new teams, you can start building the new identity by having those groups meet regularly. In this particular organization, the plan had been to hold meetings every two weeks. We changed that immediately: the teams met every morning for ten minutes for the first two months. Only such frequent clustering can override the old habits and the old self-images and build the new relations that teamwork requires. And you can give no stronger message about a new priority than to give it a visible place on everyone’s calendar.

Category 2: Worth doing but takes more time. Start planning it.

Redo the compensation system to reward compliance with the changes. This is important because you need to stop rewarding the old behavior. But do it carefully. A reward system that comes off the top of someone’s head is likely to introduce new problems faster than it clears up old ones.

Design temporary systems to contain the confusion during the cutover from the old way to the new. The time between the end of old ways and the beginning of new ones is a dangerous period. Things fall through the cracks. You’ll learn more about this when we talk about the neutral zone, but for now, suffice to say that you may have to create temporary policies, procedures, reporting relationships, roles, and even technologies to get you through this chaotic time.

Use the interim between the old system and the new to improve the ways in which services are delivered by the unit—and, where appropriate, create new services. This is the flip side of the chaotic “in-between” time: when everything is up for grabs anyway, innovations can be introduced more easily than during stable times. It’s a time to try doing things in new ways—especially new ways that people have long wanted to try but that conflicted with the old ways.

Change the spatial arrangements from individual cubicles to group spaces. Until this is done, the new human configuration has no connection with the physical reality of the place. Space is symbolic. If they’re all together physically, people are more likely to feel together mentally and emotionally.

Reorganize the general manager’s staff as a team and reconceive the GM’s job as that of a coordinator. Leaders send many more messages than they realize or intend to. Unless the leader is modeling the behavior that he or she is seeking to develop in others, things aren’t likely to change very much. As Ralph Waldo Emerson said, “What you are speaks so loudly I can’t hear what you say.”

Send team representatives to visit other organizations where service teams operate successfully. People need to see, hear, and touch to learn effectively. Talking to someone who’s actually doing something carries more weight with a doubtful person than even the best seminar or the most impressive pep talk. If you can’t take people to another location, invite a representative to your location and get a videotape that shows how work is done there.

Change the annual individual targets to team targets, and adjust bonuses to reward team performance. It’s hard to get people who are used to going it alone to play on a team, and you’ll never succeed until the game is redefined as a team sport. Annual performance schedules are part of what defines the game. Make this important change as soon as you can.

Category 3: Yes and no. Depends on how it’s done.

Bring in a motivational speaker to give employees a powerful talk about teamwork. The problem is that, by itself, this solution accomplishes nothing. And too often it is done by itself, as though, once “motivated,” people will make the change they are supposed to. This method should be integrated into a comprehensive transition management plan to be effective.

Appoint a “change manager” to be responsible for seeing that the changes go smoothly. This is a good idea if you have a well-planned undertaking, complete with communication, training, and support. But if you merely appoint someone and say, “Make it happen,” you are unlikely to accomplish anything. If the person isn’t very skilled, he or she may become simply an enforcer and weaken the change effort.

Give everyone a T-shirt with a new “teamwork” logo on it. Symbols are great, and you should use them. They have to be part of a larger, comprehensive effort. (A lot of issues come back to that point, and so will we.)

Give everyone a training seminar on how to work as a team. Seminars are important because people have to learn the new way. But much training is wasted because it’s not part of a larger, comprehensive effort.

Change the spatial arrangements so that the cubicles are separated only by glass or low partitions. You’re on the right track—individual cubicles do reinforce the old behavior—but this solution doesn’t go far enough because it doesn’t use space creatively to reinforce the new identity as “part of a team.” See Category 2 for a better solution.

Give bonuses to the first team to process 100 client calls in the new way. Rewards and competition can both serve your effort, but be sure not to set simplistic quantitative goals. Those 100 clients can be “processed” in ways that send them right out the door and into the competition’s arms. In addition, speed can be achieved by a few team members doing all the work. You want to reward teamwork, so plan your competition carefully.

Category 4: Not very important. May even be a waste of effort.

Explain the changes again in a carefully written memo. When you put things in writing, people can’t claim later that they weren’t told. Memos are actually better ways of protecting the sender, however, than they are of informing the receiver. And they are especially poor as ways to convey complex information—like how a reorganization is going to be undertaken.

Give everyone a copy of the new organization chart. An organization chart can help to clarify complex groupings and reporting relationships, but this solution is pretty straightforward. It’s the new attitudes and behavior we’re concerned with here, not which VP people report to.

Category 5: No! Don’t do this.

Turn the whole thing over to the individual contributors as a group and ask them to come up with a plan to change over to teams. Involvement is fine, but it has to be carefully prepared and framed within realistic constraints. Simply to turn the power over to people who don’t want a change to happen is to invite catastrophe.

Break the change into smaller stages. Combine the firsts and seconds, then add the thirds later. Change the managers into coordinators last. This one is tempting because small changes are easier to assimilate than big ones. But one change after another is trouble. It’s better to introduce change in one coherent package.

Pull the best people in the unit together as a model team to show everyone else how to do it. This is even more appealing, but it strips the best people out of the other units and hamstrings the other groups’ ability to duplicate the model team’s accomplishments.

Scrap the plan and find one that is less disruptive. If that one doesn’t work, try another. Even if it takes a dozen plans, don’t give up. If there is one thing that is harder than a difficult transition, it is a whole string of them occurring because somebody is pushing one change after another and forgetting about transition.

Tell them to stop dragging their feet or they’ll face disciplinary action. Don’t make threats. They build ill will faster than they generate positive results. But do make expectations clear. People who don’t live up to them will have to face the music.

As you look back over my comments and compare them to your own thinking, reflect on the change-transition difference again. When people come up with very different answers than I have offered, it is usually because they forgot that it was transition and not change that they were supposed to be watching out for. Change needs to be managed too, of course. But it won’t do much good to get everyone into the new teams and the new seating arrangements if all of the old behavior and thinking continue. As you read the rest of the book, keep reminding yourself that it isn’t enough to change the situation. You also have to help people make the psychological reorientation that they must make if the change is to work. The following chapters provide dozens of tactics that have proved helpful in doing that.

In chapter 8 you’ll find another case and another chance to try your hand at a transition management plan. But first let’s look at some well-tested transition management tactics. Chapters 3, 4, and 5 deal with how to manage, respectively, endings, neutral zones, and new beginnings. Chapter 6 talks about the stages of organizational life, and managing nonstop change is the subject of Chapter 7. When you reach the next case study, you’ll be full of ideas.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Implementing a standardized transition care plan in skilled nursing facilities

1 University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, School of Nursing, Carrington Hall CB#7460, Chapel Hill, NC, 27599, USA

Jennifer Leeman

Cathleen colón-emeric.

2 Duke University School of Medicine, Box 3003 DUMC, Durham, NC, 27710; and Durham VA Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center, 508 Fulton St., Durham, NC, 27701, USA

Laura C. Hanson

3 University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, School of Medicine, 321 S Columbia St, Chapel Hill, NC, 27516, USA

Authors’ Contributions

Associated Data

Prior studies have not described strategies for implementing transitional care in skilled nursing facilities (SNF). As part of the Connect-Home study, we pilot-tested the Transition Plan of Care template, an implementation tool that SNF staff used to deliver transitional care. A retrospective chart review was used to describe the impact of the Transition Plan of Care template on three implementation outcomes: reach to patients, staff adoption of the template, and staff fidelity to the intervention protocol for transition care planning. The template reached 100% of eligible patients (N=68). Adoption was high, with documentation by 4 disciplines in 90.6% of patient records (N=61). Fidelity to the intervention protocol was moderately high, with 73% of documentation that was concordant with the protocol. Our findings suggest an EMR-based implementation tool may increase the ability of staff to prepare older adults and their caregivers for self-care at home.

Transitional care in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs) is a multi-component intervention that supports patients who transfer from SNFs to home with the goal of preventing poor outcomes such as re-hospitalization ( Toles et al., 2016 ). As defined by the American Geriatrics Society, transitional care is a “set of actions designed to ensure the coordination and continuity of healthcare as patients transfer between different locations or different levels of care within the same location” ( Coleman & Boult, 2003 ). To date, implementing effective transitional care in SNFs is poorly understood.

A core element of transitional care is creating a patient-centered transition plan of care ( Naylor, Aiken, Kurtzman, Olds, & Hirschman, 2011 ; Naylor et al., 2017 ) that serves as a “bridging intervention,” providing patient instructions for care at home and linking providers of facility-based and home-based services and supports ( Hansen, Young, Hinami, Leung, & Williams, 2011 ). To develop a transition plan of care, clinical staff from many disciplines must identify patient needs and preferences and develop treatment goals and instructions for achieving them at home ( American Medical Directors Association, 2010 ; Jack et al., 2009 ; National Transitions of Care Coalition, 2010 ; Snow et al., 2009 ). To date, most research on transition plans of care has focused on improving the transition from hospital to home or other settings. Research to improve the transition from SNF to home is needed to address the documented lack of input from family caregivers and the omission of key guidance about administering medications, monitoring changes in health, and participating in primary care follow-up ( Lee, 2006 ; Toles et al., 2012 ; Toles, Colon-Emeric, Naylor, Barroso, & Anderson, 2016 ). Improving the quality of patient transitions from SNFs to home is significant because, in the U.S., up to a third of SNF patients are discharged to home without an adequate transition plan of care ( Department of Health and Human Services, 2013 ), and one in five patients require acute medical care within 30 days of transfers to home ( Toles et al., 2014 ).

Implementation tools (e.g., clinical algorithms, electronic documentation templates, and pocket guides) are widely used to support nursing and other clinical staff as they integrate new care processes into routine practice ( Gagliardi, Brouwers, Bhattacharyya, Guideline Implementation, & Application, 2014 ; Wandersman, Chien, & Katz, 2012b ). Though rarely used in SNFs, transitional care planning templates have been advocated for improving health transitions when patients transfer from hospitals to home; for example, to assure care planning of a core set of treatment domains for each patient, such as diagnosis, indicators that health status is worsening, special instructions for taking medication, and guidance for follow-up medical care ( Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2015 ; Society of Hospital Medicine, 2017 ). When embedded in hospital electronic medical record (EMR) systems, transitional care templates further increase the availability of information staff need to educate patients and caregivers, and create a written record of key instructions for use at home ( Cipriano et al., 2013 ).

In an earlier publication, we reported on a study of the Connect-Home transitional care intervention in SNFs; the intervention provided tools, training, and technical assistance for existing SNF staff to develop and implement a transition plan of care in the SNF and in a post-discharge telephone call at home ( Toles, et al., 2017 ). Results demonstrated the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention, and its beneficial impact on patient and caregiver self-reported preparedness for discharge. As part of the study, we pilot-tested the Transition Plan of Care (TPOC) template, a new implementation tool that SNF staff used to walk patients and caregivers through the Connect-Home intervention ( Toles et al., 2017 ). Despite growing awareness of transitional care plans, prior studies have not evaluated the implementation tools used to integrate transitional care interventions into care settings. Thus, the aim of this manuscript is to describe the impact of the TPOC template on three implementation outcomes: reach to eligible patients, staff adoption, and fidelity to the intervention protocol for transition care planning.

A two-phase process was used to develop the TPOC and implementation strategies and then to pilot test them in three SNFs. Below, we describe development of the TPOC template, strategies used to implement the template in the SNFs, and the methods used in our pilot test of the impact of the template.

Development of the Transition Plan of Care (TPOC) Template and Implementation Strategies

We designed the TPOC template to improve interdisciplinary communication and coordination within the SNF and to improve communication with those caring for the patient post discharge. Staff in the SNF were responsible for completing the TPOC in the EMR system with the following goals: (1) focus transition planning in the SNF on evidence-based transitional care domains, (2) increase information flow and problem solving across disciplines, (3) provide a written record of information and goals for the patient and caregiver on the day of discharge (along with the reconciled medication list) to guide home-based care, and (4) create a record of transition plans for the patient’s follow-up medical clinicians.

An iterative process was used to write the prototype of the TPOC template, building on prior tests of transitional care in hospitals ( Naylor, Bowles et al., 2011 ; Verhaegh et al., 2014 ), the team’s case study research in SNFs ( Toles, et al., 2016 ), and input from academic and practice-based experts in transitional care and SNFs. Next, SNF clinical and administrative staff reviewed the language and reading level, feasibility, and acceptability of the template prototype, which was subsequently revised. Finally, the TPOC template and Connect-Home intervention protocol were submitted to an Advisory Group, comprised of experts in patient care in SNFs, for final review and recommendations.

As illustrated in Table 1 , the TPOC template is designed to organize transition care planning in 16 evidence-based domains. The rationale for this decision was to establish a standard set of 16 care planning domains, including 5 in nursing (such as medications), 3 in rehabilitation therapy (such as mobility), 6 in social work (such as discharge destination), and 2 in general domains (such as caregiver understanding of the plan). For each domain, the TPOC template is configured with a free-text field for staff documentation. The rationale for using free-text fields, as opposed to a “point and click” approach to documenting with drop-down menus, was to require individualized planning for each patient in each planning domain.

Transition Plan of Care Template: Domains, Topics, and Staff Assignment

We conducted a feasibility test of the TPOC template with 10 patients. Initially, SNF staff reported that documentation requirements were too cumbersome. In response, we reduced the amount of required documentation for each domain and developed a “Cue Sheet” to identify topics for planning in each domain ( Table 1 , content from the TPOC Cue Sheet is summarized in the column 2).

We used a multiple-step process to integrate the TPOC template within SNF routines of care. Before the intervention was implemented in the individual SNFs, the lead investigator and an information technology specialist in the SNF corporate office installed the Connect-Home transition plan of care (TPOC) template in the nursing home chain EMR system. Then, five additional implementation strategies were used to promote staff adoption of the TPOC template and fidelity to the Connect-Home protocol. First, an executive champion participated in meetings to establish implementation objectives and timelines. Second, a registered nurse in each SNF was trained as site champion, including one director of nursing and two nurses in the dual role of Minimum Data Set/case manager. Third, a total of 5 administrative and 46 clinical staff members (nurses, social workers, rehabilitation therapists, and administrative staff) completed 4 hours of in-person staff training to use the TPOC template and implement the Connect-Home protocol. Fourth, staff were given a printed copy of the “Connect-Home Implementation Toolkit,” a “Cue Sheet” for using the TPOC template, and paper copies of all study tools, agendas, and schedules. Finally, 46 staff members participated in audit and feedback cycles; the primary investigator used a standardized tool to audit patient records and provide written and verbal feedback with staff about adoption and fidelity to the Connect-Home protocol.

Pilot testing the impact of the TPOC template

Design and sample for the connect-home pilot study..

A retrospective medical records review was used to evaluate the TPOC template’s impact on implementation outcomes ( Vassar & Holzmann, 2013 ). As described in a previous publication, the Connect-Home study was conducted with a non-randomized, historically controlled design ( Toles et al., 2017 ). Patients were eligible for inclusion if they: 1) spoke English, 2) had no more than mild cognitive impairment or more than mild cognitive impairment and a legally authorized representative who represented them in the research, and 3) were discharged from the SNF to home ( Toles et al., 2017 ). Of the 133 eligible patients, 68 were in the intervention arm and 65 in the control.

In this study of the TPOC template, medical records were reviewed for all intervention patients (N=68), including 24 patients in SNF 1, 23 in SNF 2, and 21 in SNF 3. Seventy-nine percent of patients were female, mean age was 80 years, mean length of SNF stay was 26 days, and treatments in the SNF most commonly focused on nursing and rehabilitative care after orthopedic surgery (e.g., hip fracture) or medical conditions (e.g., pneumonia and congestive heart failure) ( Toles et al., 2017 ). All patients provided a written signed consent to participate in the parent study. Ethics approval to conduct the study was obtained at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Implementation Outcomes and Data Collection.

Three implementation outcomes were assessed as indicators of the extent to which the Connect-Home care planning template was used as intended: reach to eligible patients, staff adoption of the TPOC template, and staff fidelity to the intervention protocol ( Proctor et al., 2011 ; Proctor et al., 2009 ). Reach was defined as the proportion of patients in the intervention arm for whom the TPOC template was initiated. Adoption was defined as the proportion of patient records that included a Transition Plan of Care template with documentation from four core members of the inter-disciplinary team, including a nurse, physical therapist, occupational therapist, and social worker. Fidelity to the intervention protocol was defined as the extent to which use of the TPOC template was concordant with the transition planning guidance provided in the TPOC Cue Sheet ( Table 1 , column 2). Published instruments for evaluating the quality of transition care plans were not available; thus, we developed the TPOC Review Instrument to assess whether documentation in each TPOC template domain included the content specified in the Connect-Home protocol (fidelity to protocol). The TPOC Review Instrument included criteria for rating intervention fidelity in 11 of the 16 domains on a yes/no scale, with “yes” scored as 1 and “no” scored as 0 (see Supplementary File 1 ). Five domains were not relevant in planning of all patients (e.g., caregiver understanding was not relevant in care of patients with no identified family or other caregiver) and therefore were not included in the review; thus, accurate use of the template was defined as completing 11 domains, and the range of possible scores on the instrument was 0–11.

The lead investigator and a trained research assistant independently reviewed the TPOC for all patients in the intervention arm; agreement between evaluators was 100% for staff adoption of the TPOC tool and 94% for fidelity to the Connect-Home protocol. Differences in the way items were scored were resolved by consensus.

The reach of the TPOC to eligible patients was calculated by dividing the number of times a template was initiated by the number of eligible patients (N=68). Staff adoption of the template was calculated by dividing the number of Transition Plan of Care templates with documentation from a nurse, physical therapist, occupational therapist, and social worker by the total sample of Transition Plan of Care templates. Fidelity to the intervention protocol was calculated as the average number of domains per medical record that were concordant with the intervention protocol. In addition, we collected exemplar documentation of low versus high fidelity transition care planning from the TPOC across the sample. Data were managed and calculated in Microsoft Excel.

Impact of the TPOC template

Patient reach and staff adoption of the tpoc template..

We found that SNF staff initiated the TPOC template in care of 100% of patients (n=68). Documentation that all four disciplines adopted the TPOCs was found on 61 (91.6%) of those templates. In records of seven patients, reviewers could not determine the name or discipline of the individuals who completed one or more of the domains in the TPOC. Because information was incomplete, the TPOCs for these seven patients were excluded from the analysis of fidelity.

Fidelity of transition planning to the Connect-Home protocol.

For the sample of 61 patients, the average number of TPOC template domains that included content specified in the Connect-Home protocol was 8.3 domains out of the 11 domains on the TPOC Review Instrument, indicating relatively high overall fidelity. The number of domains with content specified in the protocol co-varied with setting: in SNF 1, the average was 7.2 domains, in SNF 2 the average was 8.5 domains, and in SNF 3, the average was 9.3 domains.

Exemplars of documentation that was and was not concordant with the intervention protocol are described in Table 2 . There were five common patterns in documentation with low fidelity. First, in the “Home Health Care” and “Follow-up Appointments” domains, documentation in 15% of records did not include critical details such as telephone numbers of caregivers and follow-up clinicians or service providers (exemplar 1). Second, plans in the “Signs of Worsening Health” domain identified a sign or a symptom to monitor but in 18% of records did not suggest an appropriate response, such as calling a physician for help (exemplar 2). Third, plans in the “Medical Treatments” and “Medications” domains indicated the name of a treatment or medication (such as use of a back brace) but in 25% of records did not describe procedures for continuing the treatment or medication at home (exemplars 3 and 4). Fourth, in the “Advanced Care Planning” domain, no records of patients with advanced care plans included complete information (exemplar 5). Finally, plans in the “Mobility” and “Self-care” domains included technical jargon (15%) or did not describe specific instructions (e.g., falls prevention) for safety at home (18%) (exemplar 6).

Low vs. High Fidelity Documentation in the TPOC Template

L = low concordance; H = high concordance

Progress has been made in developing effective transitional care interventions and improving health outcomes after older adults transfer between settings and providers of care. 1 The next step is for this field to move from innovation to implementation to improve transitional care. Implementation tools have potential to standardize transitional care processes and integrate them into complex systems. ( Toles et al., 2016 ; Wandersman, Chien, & Katz, 2012a ; Leeman et al., 2015 ). In this paper we report on development and implementation outcomes for the TPOC, an implementation tool developed to integrate the Connect-Home transitional care intervention into three SNFs. We found that the template was used for 100% of patients and that all involved disciplines adopted the template for at least 90.6% of patients. Findings also support staff fidelity to the tool (76%), with substantial inter-facility variation in the extent that documented transition care plans were concordant with the protocol.

Taken together, these findings support the potential value of the TPOC as a tool for improving transitional care in SNFs. The TPOC template created a focal point for transition care planning in the SNFs and clearly articulated core domains of transitional care. The TPOC template replaced the “Discharge Summary” form in the SNFs, which did not include specific nursing, rehabilitation therapy, and advanced care planning goals or recommendations. By requiring written documentation, the TPOC overcame the limitations of the SNFs’ prior reliance on verbal communication of discharge goals and instructions among disciplines and to patients and sometimes caregivers. With the template, a complete set of transition plans were documented in one place, which created the opportunity for presenting a more unified overall plan to patients and their caregivers. The “Cue Sheet,” developed to support staff use of the TPOC template, provided detailed guidance on care processes and documentation required for each domain. This resource was critical for helping staff members learn and routinize elements of an evidence-based transition care plan.

Understood in terms defined in the “Applied Framework for Understanding Health Information Technology in Nursing Homes,” this study showed that, when integrated into the EMR system, the TPOC supported staff members’ successful implementation of the patient care protocol in the SNFs ( Degenholtz, Resnick, Lin, & Handler, 2016 ). First, addressing the need to integrate patient care across fragmented settings and providers of medical care ( Coleman, 2003 ; Ng, Harrington, & Kitchener, 2010 ), the TPOC enabled staff to more reliably document a complete description of the plan for home-based care. Although created primarily for the patient and caregiver, the SNF staff also faxed the TPOC to primary care clinicians ( Toles et al., 2017 ). Second, preparing nursing homes to comply with pending readmission penalties ( Carnahan, Unroe, & Torke, 2016 ), staff use of the TPOC template generated an auditable record of transition care planning for demonstrating compliance with regulatory standards. Third, using the TPOC template contributed data usable in quality improvement efforts; for example, in our assessment of staff fidelity, we found that no transition plan in the study included complete information about advanced care plans, which suggested an area for future quality improvement work. Fourth, staff use of the TPOC generated structured clinical information guided care in the SNF and during follow-up calls with patients after discharge ( Toles et al., 2017 ). Finally, the TPOC template also supported patients and their caregivers with instructions for recommended medication use, and communicated clinical information for patients and caregivers to use at home ( Toles et al., 2017 ). These findings suggest that implementation strategies, including an EMR template for transition care planning, promote the capacity of SNF staff to prepare older adults and their caregivers for self-care at home, and prevent re-hospitalization.

The TPOC template was designed with extensive staff input to ensure a pragmatic approach for staff to write brief, action-oriented, individualized goals and instructions for patients in 16 domains. The TPOC also may be used in future research to refine and tailor the Connect-Home intervention. Gaps in performance will require revisions to the training and technical assistance; in particular, additional staff training to 1) recognize and record advance care plans and 2) to identify specific steps for responding to changes in health as they emerge. To address complex goals of care and implications for the care plan, additional patient educational materials are likely needed to supplement the TPOC, such as instructions for using warfarin, providing assistance with using shower benches and assistive devices, and more detailed instructions for health monitoring.

Future research is also needed to explain variations in performance across SNFs, information that may then be applied to tailor Connect-Home to fit the needs of different settings; for example, using fidelity monitoring in quality improvement cycles with staff across SNFs. Although initial pilot testing provided support for Connect-Home’s effectiveness ( Toles et al., 2017 ), additional research is needed to confirm effectiveness and also to assess the role that TPOC adoption/fidelity plays in sustaining Connect Home effectiveness on patient and caregiver outcomes.

The medical records review of the TPOC for intervention participants in the Connect-Home pilot study is limited by small number of charts reviewed, the small number of SNFs that participated, and potential biases of the investigators who conducted the medical records review. Limitations in using a retrospective chart review to assess implementation outcomes limits the reliability of study findings; for example, if staff developed elements of a transition plan without consulting patients, the chart review potentially misidentified intervention fidelity. Moreover, in seven records it was not feasible with the chart review to determine which discipline recorded some of the patient’s goals in the TPOC, thereby limiting assessment of staff adoption using these records. Although the study has these limitations, it provides essential data about novel implementation strategies to deliver transitional care and improve patient and caregiver preparedness for discharge.

Gaps in the quality of transitional care place SNF patients at high risk for poor health outcomes. Recent changes in healthcare policy present an opportunity to invest in closing the quality gap. The U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services will soon implement a value based payment program designed to improve SNF patient and cost outcomes. Under this program, facilities with the lowest rate of hospital readmissions in 30 days will receive the largest payment, and facilities with the highest rate will receive payments less than they would have received before the program ( Carnahan et al., 2016 ). The findings in this study of suggest that an EMR-based implementation tool may strengthen the integration of transitional care best practices into SNF’s care processes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

The authors wish to acknowledge Gail Hall and Deborah Tillman who assisted with data collection.

This work was supported by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, grant number: 1KL2TR001109. Mark Toles was also supported by the John A. Hartford Foundation.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Research Ethics and Patient Consent

All patients provided a written signed consent to participate in the parent study. Ethics approval to conduct the study was obtained at the Institutional Review Board at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2015). Re-Engineered Discharge (RED) Toolkit . Retrieved from http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/systems/hospital/red/toolkit/index.html

- American Medical Directors Association. (2010). Transitions in Care in the Long Term Continuum Clinical Practice Guideline . Columbia, MD: AMDA. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carnahan JL, Unroe KT, & Torke AM (2016). Hospital Readmission Penalties: Coming Soon to a Nursing Home Near You! J Am Geriatr Soc , 64 ( 3 ), 614–618. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14021 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cipriano PF, Bowles K, Dailey M, Dykes P, Lamb G, & Naylor M (2013). The importance of health information technology in care coordination and transitional care . Nursing Outlook , 61 ( 6 ), 475–489. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Coleman EA (2003). Falling through the cracks: Challenges and opportunities for improving transitional care for persons with continuous complex care needs . Journal of the American Geriatrics Society , 51 ( 4 ), 549–555. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Coleman EA, & Boult C (2003). Improving the quality of transitional care for persons with complex care needs . Journal of the American Geriatrics Society , 51 ( 4 ), 556–557. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Degenholtz HB, Resnick A, Lin M, & Handler S (2016). Development of an Applied Framework for Understanding Health Information Technology in Nursing Homes. Journal of the American Medical Directors’ Association , 17 ( 5 ), 434–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.02.002 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Department of Health and Human Services. (2013). Skilled nursing facilites often fail to meet care planning and discharge planning requirements . Retrieved from https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-09-00201.pdf

- Gagliardi AR, Brouwers MC, Bhattacharyya OK, Guideline Implementation R, & Application N (2014). A framework of the desirable features of guideline implementation tools (GItools): Delphi survey and assessment of GItools . Implement Sci , 9 , 98. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0098-8 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, & Williams MV (2011). Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review . Annals of Internal Medicine , 155 ( 8 ), 520–528. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00008 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, Greenwald JL, Sanchez GM, Johnson AE, … Culpepper L (2009). A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: A randomized trial . Annals of Internal Medicine , 150 ( 3 ), 178–187. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee J (2006). An imperative to improve discharge planning: Predictors of physical function among residents of a medicare skilled nursing facility . Nursing Administration Quarterly , 30 ( 1 ), 38–47. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leeman J, Calancie L, Hartman M, Escoffery C, Hermann A, Tague L, & al e. (2015). What strategies are used to build practitioners’ capacity to implement community-based interventions and are they effective?: A systematic review . Implement Sci , 10 , 80. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- National Transitions of Care Coalition. (2010). Improving Transitions of Care . Retrieved from http://www.ntocc.org/Portals/0/PDF/Resources/NTOCCIssueBriefs.pdf

- Naylor MD, Aiken LH, Kurtzman ET, Olds DM, & Hirschman KB (2011). The care span: The importance of transitional care in achieving health reform . Health Affairs , 30 ( 4 ), 746–754. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0041 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Naylor MD, Bowles KH, McCauley KM, Maccoy MC, Maislin G, Pauly MV, & Krakauer R (2011). High-value transitional care: translation of research into practice . Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice . doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01659.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Naylor MD, Shaid EC, Carpenter D, Gass B, Levine C, Li J, … Williams MV (2017). Components of Comprehensive and Effective Transitional Care . Journal of the American Geriatrics Society , 65 ( 6 ), 1119–1125. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14782 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ng T, Harrington C, & Kitchener M (2010). Medicare and medicaid in long-term care . Health Affairs , 29 ( 1 ), 22–28. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0494 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, … Hensley M (2011). Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda . Administration and Policy in Mental Health , 38 ( 2 ), 65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Proctor EK, Landsverk J, Aarons G, Chambers D, Glisson C, & Mittman B (2009). Implementation Research in Mental Health Services: an Emerging Science with Conceptual, Methodological, and Training challenges . Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research , 36 ( 1 ), 24–34. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, Miller DC, Potter J, Wears RL, … Williams MV (2009). Transitions of Care Consensus policy statement: American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College Of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine . J Hosp Med , 4 ( 6 ), 364–370. doi: 10.1002/jhm.510 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Society of Hospital Medicine. (2017). Project BOOST: Implementation Toolkit . Retrieved from http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Quality_Innovation/Implementation_Toolkits/Project_BOOST/Web/Quality___Innovation/Implementation_Toolkit/Boost/First_Steps/Implementation_Guide.aspx

- Toles M, Anderson RA, Massing M, Naylor MD, Jackson E, Peacock-Hinton S, Colon-Emeric C, (2014). Restarting the cycle: incidence and predictors of first acute care use after nursing home discharge . Journal of the American Geriatrics Society , 62 ( 1 ), 79–85. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12602 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Toles M, Barroso J, Colon-Emeric C, Corazzini K, McConnell E, Anderson RA, (2012). Staff interaction strategies that optimize delivery of transitional care in a skilled nursing facility: a multiple case study . Family and Community Health , 35 ( 4 ), 334–344. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e31826666eb [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Toles M, Colon-Emeric C, Asafu-Adjei J, Moreton E, Hanson LC, (2016). Transitional care of older adults in skilled nursing facilities: A systematic review . Geriatr Nurs , 37 ( 4 ), 296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.04.012 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Toles M, Colon-Emeric C, Naylor MD, Asafu-Adjei J, Hanson LC, (2017). Connect-Home: Transitional Care of Skilled Nursing Facility Patients and their Caregivers . Journal of the American Geriatrics Society . doi: 10.1111/jgs.15015 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Toles M, Colon-Emeric C, Naylor MD, Barroso J, Anderson RA, (2016). Transitional care in skilled nursing facilities: a multiple case study . BMC Health Serv Res , 16 , 186. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1427-1 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vassar M, & Holzmann M (2013). The retrospective chart review: important methodological considerations . J Educ Eval Health Prof , 10 , 12. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2013.10.12 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Verhaegh KJ, MacNeil-Vroomen JL, Eslami S, Geerlings SE, de Rooij SE, & Buurman BM (2014). Transitional care interventions prevent hospital readmissions for adults with chronic illnesses . Health Affairs , 33 ( 9 ), 1531–1539. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0160 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wandersman A, Chien VH, & Katz J (2012a). Toward an Evidence-Based System for Innovation Support for Implementing Innovations with Quality: Tools, Training, Technical Assistance, and Quality Assurance/Quality Improvement . Am J Community Psychol . doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9509-7 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wandersman A, Chien VH, & Katz J (2012b). Toward an evidence-based system for innovation support for implementing innovations with quality: tools, training, technical assistance, and quality assurance/quality improvement . American Journal of Community Psychology , 50 ( 3–4 ), 445–459. doi: 10.1007/s10464-012-9509-7 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- {{subColumn.name}}

AIMS Energy

- {{newsColumn.name}}

- Share facebook twitter google linkedin

Hydrogen economy transition plan: A case study on Ontario

- Faris Elmanakhly 1,# ,

- Andre DaCosta 2,# ,

- Brittany Berry 3,4 ,

- Robert Stasko 4 ,

- Michael Fowler 2 ,

- Xiao-Yu Wu 1 , ,

- 1. Department of Mechanical and Mechatronics Engineering, University of Waterloo, 200 University Avenue West, Waterloo, ON N2L 3G1, Canada

- 2. Department of Chemical Engineering, University of Waterloo, 200 University Avenue West, Waterloo, ON N2L 3G1, Canada

- 3. School of Environment, Enterprise and Development, University of Waterloo, 200 University Avenue West, Waterloo, ON N2L 3G1, Canada

- 4. Hydrogen Business Council, 2140 Winston Park Drive, Unit 203, Oakville, ON L6H 5V5, Canada

- # FE and AD contributed equally

- Received: 02 April 2021 Accepted: 22 June 2021 Published: 25 June 2021

- Full Text(HTML)

- Download PDF

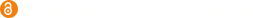

A shift towards a "hydrogen economy" can reduce carbon emissions, increase penetration of variable renewable power generation into the grid, and improve energy security. The deployment of hydrogen technologies promises major contributions to fulfilling the economy's significant energy needs while also reducing urban pollution emissions and the overall carbon footprint and moving towards a circular economy. Using the Canadian province of Ontario as an example, this paper prioritizes certain recommendations for near-term policy actions, setting the stage for long-term progress to reach the zero-emissions target by 2050. To roll out hydrogen technologies in Ontario, we recommend promptly channeling efforts into deployment through several short-, mid-, and long-term strategies. Hydrogen refueling infrastructure on Highway 401 and 400 Corridors, electrolysis for the industrial sector, rail infrastructure and hydrogen locomotives, and hydrogen infrastructure for energy hubs and microgrids are included in strategies for the near term. With this infrastructure, more Class 8 large and heavy vehicles will be ready to be converted into hydrogen fuel cell power in the mid-term. Long-term actions such as Power-to-Gas, hydrogen-enriched natural gas, hydrogen as feedstock for products (e.g., ammonia and methanol), and seasonal and underground storage of hydrogen will require immediate financial and policy support for research and technology development.

- hydrogen economy ,

- hydrogen production ,

- hydrogen storage ,

- alternative fuel ,

- 2 emissions" type="keywords.keywordEn">Net-Zero CO 2 emissions ,

- Ontario hydrogen roadmap

Citation: Faris Elmanakhly, Andre DaCosta, Brittany Berry, Robert Stasko, Michael Fowler, Xiao-Yu Wu. Hydrogen economy transition plan: A case study on Ontario[J]. AIMS Energy, 2021, 9(4): 775-811. doi: 10.3934/energy.2021036

Related Papers:

- This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ -->

Supplements

Access history.

- Corresponding author: Email: [email protected] ; Tel: +15198884567

Reader Comments

- © 2021 the Author(s), licensee AIMS Press. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 )

通讯作者: 陈斌, [email protected]

沈阳化工大学材料科学与工程学院 沈阳 110142

Article views( 6893 ) PDF downloads( 721 ) Cited by( 7 )

Figures and Tables

Figures( 10 ) / Tables( 4 )

Associated material

Other articles by authors.

- Faris Elmanakhly

- Andre DaCosta

- Brittany Berry

- Robert Stasko

- Michael Fowler

Related pages

- on Google Scholar

- Email to a friend

- Order reprints

Export File

- Figure 1. Different power-to-gas pathways (Reprinted from [ 30 ] under the terms of the Creative Commons CC-BY license)

- Figure 2. Schematic of a PEM fuel cell

- Figure 3. Diagram of PEM fuel cell components (Adapted from [ 92 ] )

- Figure 4. Emissions based on the sector in Canada, 2018 (Data from [ 93 ] )

- Figure 5. Ontario energy demand breakdown [ 99 ]

- Figure 6. Total traffic and truck traffic distribution along Highway 401 (Reprinted from [ 23 ] with permission of Elsevier). 1

- Figure 7. Proposed locations of hydrogen production and refueling stations along the 401 (Adapted from [ 23 ] with permission of Elsevier). 2

- Figure 8. Schematic of hydrogen as an energy vector in a microgrid system (Reprinted from [ 116 ] with permission from Elsevier). 3

- Figure 9. Diagram of energy interactions between hypothetical energy hubs (Adapted from [ 118 ] with permission from Elsevier) 4 [ 102 ]

- Figure 10. Ontario's exports through trucking [ 101 ]

Call for transition plan case studies

Calling all ESG practitioners and teams! The Transition Plan Taskforce wants to learn from your organisation’s transition planning journey.

The TPT is seeking ESG practitioners and teams interested in capturing reflections about their preparation and use of transition plans in a short case study to share with other preparers and users of transition plans in our audiences. We are also looking to highlight your examples of relevant disclosures from existing transition plans and annual reports.

TPT plans to use these illustrative examples within the Build Your Transition Plan section of the TPT’s Website, in our Explore the Disclosure Recommendations and Transition Planning Cycle guidance. In doing so, we will help preparers needing to develop and publish their own transition plans.

If interested, please e-mail [email protected] We will follow-up directly with any suitable examples. We look forward to seeing your submissions!

Watch existing video case studies below. More written case studies can be found in the various sections of Build Your Transition Plan .

Latest transition plan resources published today

The TPT launches today its final set of transition plan resources to help businesses

Speakers announced for event – register for the live stream

Transition Plan Taskforce (TPT) announces the speakers for its event on 9 April from

Unlocking Finance and Growth through Credible Transition Plans

Tuesday 9 April 2024, 18:00 – 19:30, Guildhall – London Our next major event

Sharing transition plan case studies

Explore case studies and examples relating to elements of the TPT Disclosure Framework and

The TPT’s mandate has been extended

The TPT was announced at COP26 in Glasgow and launched in April 2022 with

How do TPT transition plan resources apply for my sector?

The TPT’s core Disclosure Framework is sector-neutral and can be used by any sector.

TPT materials are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY-NC-ND https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.en ), which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. Please contact the Secretariat for any other usage requests.

- Explore the Disclosure Recommendations

Privacy Policy | Cookie Policy

Sign up to hear more from the TPT

Transition Planning and the IEP

Case studies: determine the extent and type of transition services needed, table of contents.

Page 24 of 51

Each case study provides an example of a set of transition services that directly support the associated postsecondary goal. These examples are not meant to suggest that these are the only or priority transition services. Instead, they offer a sample of how services might be identified and aligned to identified needs of the postsecondary goal.

Overview of postsecondary goals:

“Robert will independently work part-time in a body shop making car repairs, attend adult education classes in the community, and plans to move to his own apartment.

Team discussion determined that Robert’s transition services should include assessment to determine his current level of skill in the area of auto repair, as well as his ability to transfer his study skills to the adult education environment. He will require instruction in social skills in order to interact effectively with coworkers and customers. Robert also needs to gain understanding of the aspects of adult education that may be different from high school. Although Robert demonstrates some daily living skills, he will need instruction in this area so that he can become independent and competent to achieve his postsecondary goals. Following are some of the specific transition services that the team felt would address these needs.

Transition Services

Employment:.

Assistance to access and create an Ohio Means Jobs backpack and to select and navigate through surveys and information about automotive jobs and skills.

Vocational assessment to determine current abilities in the area of car repair and related skills

Job shadowing/work experience in an auto body shop to assess his ongoing interest and improve skills related to community employment and auto mechanics

Specialized instruction in social competency related to interactions with supervisor, coworkers and customers.

Instruction in how to identify adult classes, register and travel to the class in a timely manner.

Community experience to take an adult education class to become familiar with the location, the pace and structure of the courses and to apply study and social skills.

Independent Living:

Daily living skills training by participation in a life skills class.

“After high school and college graduation, Antonio will attend a four-year college and then work in the field of aerospace engineering, plastics and polymer manufacturing or pharmaceuticals. He plans to live in the dorms and then independently in his own apartment.“

Antonio’s team determined that his transition services should include experiences that provide additional assessment as well as improve his skills related to his adult goals.

Community experiences/shadowing of chemical engineer to confirm career direction.

Related service for an assistive technology assessment related to accommodations for college courses, community experiences visiting campuses.

Community experiences visiting dorms and planning an overnight experience.

“Following high school, Carla will work part-time in a community setting with support in an area of interest and skill. She will receive on-the-job training for her employment and also instruction in daily living skills. She plans to move from the family home to a supported residential home when the appropriate supported and individualized setting is available. During planning, the team determined the need for more information related to how well Carla was able to use her skills in the community and potential supports or accommodations she could use in adult life.

Assistance to access and create an Ohio Means Jobs backpack and to select and navigate through surveys and information to identify interests, skills and preferences related to employment

Community work experiences in areas of interest and potential work/volunteer opportunities

Functional vocational assessment

Assistive technology assessment

On-the-job instruction in community work experiences.

Life skills instruction

Community experiences in residential and leisure opportunities to assess future needs

- Open access

- Published: 11 January 2024

How Germany is phasing out lignite: insights from the Coal Commission and local communities

- Jörg Radtke ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6540-8096 1 &

- Martin David ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7982-3127 2

Energy, Sustainability and Society volume 14 , Article number: 7 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

773 Accesses

22 Altmetric

Metrics details

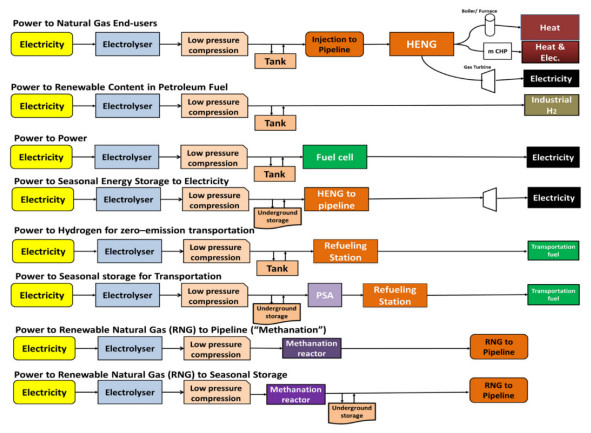

This article asks the following question: how well are coal regions, affected by phase-out plans, represented in mediating commissions, to what extent do local communities participate in the decision-making process and how are the political negotiations perceived by the communities? We look at the case of the German lignite phase-out from a procedural justice perspective. Informed by literature on sociotechnical decline and procedural justice in energy transitions, we focus first on aspects of representation, participation and recognition within the German Commission on Growth, Structural Change and Employment (“Coal Commission”). Second, we analyze how to exnovate coal in two regions closely tied to the coal- and lignite-based energy history in Germany: Lusatia and the Rhenish Mining District.

Based on interview series in both regions, we connect insights from local communities with strategies for structural change and participation programs in the regions. We find significant differences between the two regions, which is primarily an effect of the challenging historical experiences in Lusatia. Participation within existing arrangements is not sufficient to solve these problems; they require a comprehensive strategy for the future of the regions.

Conclusions

We conclude that the first phase-out process was a lost opportunity to initiate a community-inclusive sustainable transition process. As the phase-out process is not yet concluded, additional efforts and new strategies are needed to resolve the wicked problem of lignite phase-out.

Introduction: justice, recognition and the representation of public interest in the German coal phase-out

Studies have examined defossilization or decarbonization from a distributional or intergenerational justice perspective [ 1 , 2 ]. This article adds a procedural justice perspective to the question of deliberate sociotechnical decline [ 3 ].

The literature has delved into the ways in which the state can promote more sustainable living [ 4 ], particularly concerning energy resources [ 5 ]. An essential question revolves around the legitimacy of state structures in determining the design and sustainability of public goods, such as electricity production [ 6 , 7 , 8 ]. In the deployment of renewable energy technologies [ 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ], the legitimacy question has been examined from the procedural justice perspective. Here, we use the perspective to analyze the German coal phase-out process and its implications for affected local communities.

Lignite is a distinctive incumbent fossil fuel that cannot be stored and must be burned for electricity and heat [ 13 ]. This practice is widespread in Germany, notably in the Rhenish Mining District (West Germany) and in Lusatia (East Germany), two regions whose economies are based on lignite mining. Transitions away from lignite will significantly alter local conditions, but coal phase-out takes precedence from an environmental standpoint, given that the combustion of lignite is more detrimental than that of hard coal.

We analyze the Coal Commission's work from 2018 to 2019, considering the anticipations for it and reactions to it, as well as development programs and strategies developed from it for the affected regions. We consider decarbonization in the years following the Commission’s work, which allows us to evaluate this key pillar in Germany's climate strategy [ 14 , 15 , 16 ]. The Commission aimed to balance the interests of different regions, communities, and stakeholders in the lignite phase-out, a challenge when the main lignite mining regions, Rhineland and Lusatia, are economically weak and chronically lack qualified workers [ 17 , 18 , 19 ]. We analyze how the Commission`s decisions are perceived and evaluated by citizens and stakeholders in the mining regions, comparing the representation of interests and the participation of stakeholders, as well as conflicts and controversies in the two regions, leading to three research questions:

Representation of affected regions: how did the affected regions react to the decisions to phase out coal; how was equal representation of interests achieved (or not)?

Participation of local communities: which participation processes can be found in the two regions; how are they conceptualized, and do they deliver procedural justice?

Conflict and controversy about the phase-out process: what controversies arose and how well could conflicts be solved during and after the process of decision-making?

Through these questions, we can present in detail how state intervention affects procedural justice in (former) German coal regions by studying how people's representation in the Coal Commission's decision-making processes was (or was not) enabled.

Framework: procedural justice and social representation in processes of deliberate sociotechnical decline

Sociotechnical discontinuation and procedural justice.

We use “sociotechnical discontinuation” to mean leaving unsustainable energy practices through exnovation and phase-out policies [ 20 ]. This involves procedural justice, which requires energy systems be “clean, efficient and affordable” [[ 21 ], p. 2541] and meet other criteria [ 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 ]. However, as technology transition is controversial and creates winners and losers [ 3 ], procedural justice also concerns the quality of legal and political processes [ 9 , 13 ], including those related to sociotechnical decline [ 10 ]. We focus on three aspects of procedural justice: representation, participation, and conflict resolution.

Representation

We discuss two aspects of social representation in lignite phase-out. One is the influence of experts, policy makers and administrators on technological design [ 26 , 27 ]. We examine how the Commission excluded a specific technology from the discussion and focused on the phase-out. The second aspect is the reactions of local inhabitants and Commission representatives to technology implementation [ 12 ]. We use the concepts of participation, equality, fairness and information provision to analyze representation in the decision-making process [ 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ]. We also consider how inequality and injustice are embedded in the cultural politics of coal [ 33 ].

Intentional participation