- Home

- University Colleges

- SUNY College at New Paltz

- SUNY New Paltz Undergraduate Honors Thesis Collection

Campus Communities in SOAR

Exploring love languages: the key to building and maintaining healthy relationships.

Average rating

Cast your vote you can rate an item by clicking the amount of stars they wish to award to this item. when enough users have cast their vote on this item, the average rating will also be shown. star rating, date published, collections.

The following license files are associated with this item:

- Creative Commons

entitlement

Export search results

The export option will allow you to export the current search results of the entered query to a file. Different formats are available for download. To export the items, click on the button corresponding with the preferred download format.

By default, clicking on the export buttons will result in a download of the allowed maximum amount of items.

To select a subset of the search results, click "Selective Export" button and make a selection of the items you want to export. The amount of items that can be exported at once is similarly restricted as the full export.

After making a selection, click one of the export format buttons. The amount of items that will be exported is indicated in the bubble next to export format.

Creating a Healthy Loving Relationship Essay

Introduction.

The most important ingredient for a healthy relationship is unwavering love. Love can be described as a feeling of cherishing and holding each other dearly and unconditionally. The prayer for everyone who is in, or intends to get into a relationship is that the relationship will be healthy and loving for as long as it takes. However, whether relationship will be healthy depends on the mutual commitment of the partners in building and maintaining the bond between them through loyalty, acceptance, communication, and appreciation among others. In building a healthy loving relationship, four key behavioral qualities must be entrenched; respect, trust, honest and caring.

Is essential as it shows concern for the other person’s wellbeing. It involves empathy and accommodation while appreciating the other person’s feelings and offering a shoulder to lean on. According to Wlliams (2006) care involves feeling that the happiness of the other person is more important than your own happiness. Offering support to the other partner at all times and in all endeavors enhances the bonding and creates a path for commitment of either partner in his/her role in the relationship. A healthy loving relationship depends on how well the couple is able to resolve conflicts as they arise in which case reflective listening is paramount. Identifying and solving, and expressing differences caringly is important to the couple’s wellbeing (Schaeffer 1997).

Is a feeling of confidence and faith with the other half that he/she can be relied upon without reservations. This means that, both partners should be committed to earning trust by appreciating each other and being morally upright with utmost value and dignity thus creating a sense of security to each other. In addition, spending time together and being consistent with amount of time spent together builds trust. For trust to prevail, their must be agreement between the partners which gives a sense of moral self integrity and dedication to either partner. Where agreement fails or breaks down, the relationship suffers from eroded trust and breakdown in communication, the remedy of which is to amend or institute a new agreement as soon as possible before the damage becomes worse.

Keeps the relationship intact as, apart from building trust, it ensures both partners engage in truth and meaningful communication with no intent to hurt each other whatsoever. Being honest with oneself also helps to be honest to the other partner. Even where problems are available, admitting their existence means being honest, which in turn acts as a step towards seeking solution. Openness with undistorted information whether negative or not, provided it is the truth is important to keep the relationship intact. Withholding the truth may become disastrous in future in case the truth is revealed in one way or another.

For each other tends to ensure that the values and feelings of either partner are appreciated and not compromised. This means that, both partners value, appreciate and understand each other and in the process tend to accommodate each other. Communication plays a vital role in establishing respect in that, the tone and level of command used influences the level of respect portrayed. Listening as twice as you speak and understanding other person’s boundaries helps to create respect and ignite the mutual bonding in the relationship.

In conclusion, the path to a healthy loving relationship is commitment by both partners to their roles and embodiment of love that is unconditional. In addition upholding the tenets of care, honesty trust and respect, not only shows willingness to foster love, but also enhances connectivity between partners.

Benokraitis, Nijole Vaicaitis. Marriages and families: changes, choices, and constraints. 2 nd Edition, 1996. NJ: Prentice Hall.

Schaeffer, Brenda. Is It Love or Is It Addiction. 2 nd Edition, 1997. MN: Hazelden Publishing.

Williams, Richard N. “Loving and Caring for Each Other”. Loving and Caring for Each Other. 2006. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, November 1). Creating a Healthy Loving Relationship. https://ivypanda.com/essays/creating-a-healthy-loving-relationship/

"Creating a Healthy Loving Relationship." IvyPanda , 1 Nov. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/creating-a-healthy-loving-relationship/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Creating a Healthy Loving Relationship'. 1 November.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Creating a Healthy Loving Relationship." November 1, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/creating-a-healthy-loving-relationship/.

1. IvyPanda . "Creating a Healthy Loving Relationship." November 1, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/creating-a-healthy-loving-relationship/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Creating a Healthy Loving Relationship." November 1, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/creating-a-healthy-loving-relationship/.

- Reasons for Not Appreciating Different Cultural Point of View

- Intimate Relationships: Conceptual Distinction Between Liking and Loving

- Classic & Modern Art Classifying and Appreciating

- Why Beautiful Women Prefer Unattractive Men

- First Date: Sociological Analysis

- “Sex and the City”: The Question of Monogamy and Polygamy

- Why People Idealize Love but Do Not Practice It

- Love. Characteristics of a True Feeling

The Main Theses of Healthy Relationship

Introduction, factors that enhance healthy relationship, you should work towards your happiness, make and keep clear agreements, communication, forgiveness, works cited.

A healthy relationship refers to a good relation with the people around you whereby there are no instances of quarrel or disagreements over given issues. Not every person in the society knows how to maintain healthy or good relationship with the people around him or her and this is the reason you find that there very many broke relationships in the society. (Harry, 2008)

There are certain factors that play great role in maintaining healthy relationships among people in the society and which in most cases should be followed in order to have good relationships with people around us. These factors include the following

As a partner in a relationship you should work towards achieving happiness in that relationship and this can only be achieved through understanding of certain concepts. First accept who you are, acceptance of who you are will give you confidence when handling issues in the relationship, this is because you will not accept anything that will intimidate your dignity hence you will be happy in that relationship. Secondly respect yourself; if you respect yourself other will respect you too, its out of that the other party in the relationship will also respect you. If you don’t respect yourself it will be difficult for other people to respect hence you will suffer in the relationship. (Harry, 2008)

Every person in the relationship should strive towards achieving his or her own happiness in the relationship. This is because many people in society expect other people to give them happiness and in most cases you find that even though in a relationship every person is more concerned about his or her life. Because of this in order to achieve a healthy relationship with your partner you should ensure that you are working towards your happiness as well as his or her happiness. (Harry, 2008)

One thing people should understand while in a relationship is that you are different from the other and every one of you has his own likes and dislikes as well as principles. It is important to make and keep clear agreements on certain issues which concern both of you, before you conclude on something you should first reach a common agreement or plan on the issue at hand and then make a commitment to it. Both of the partners should ensure that they work towards achieving the agreement, it would be difficult for one partner to adhere to the agreement while the other to keep on failing. In such a case it is advisable to leave the relationship since you will keep on quarrelling over simple matters. (Margret 2010)

Common is a very essential tool in success of any partnership not only in a relationship, in order for a relationship to be successful and healthy there should be efficient communication whereby there is free flow of information between the partners. Good communication enables partners in a relationship to understand each other better and also to understand each others point of view in different issues hence creating a common understanding and agreement between the partners. (Margret 2010)

Forgiveness is very important in the society we are in and especially as it concerns relationships, this is because it gives the other person room in the relationship. Forgiveness is a choice one makes of letting go what has been done to you however hurting it may be. You should talk about the issue with your partner and let go whatever thing he or she has done to you; at the same time you should let him or her know that you have forgiven him for the relationship to continue and to regain back happiness. (Harry, 2008)

Harry, Croft. What is a healthy relationship . Web.

Margret, Paul. 10 signs of a healthy relationship. Web.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2021, December 12). The Main Theses of Healthy Relationship. https://studycorgi.com/the-main-theses-of-healthy-relationship/

"The Main Theses of Healthy Relationship." StudyCorgi , 12 Dec. 2021, studycorgi.com/the-main-theses-of-healthy-relationship/.

StudyCorgi . (2021) 'The Main Theses of Healthy Relationship'. 12 December.

1. StudyCorgi . "The Main Theses of Healthy Relationship." December 12, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/the-main-theses-of-healthy-relationship/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "The Main Theses of Healthy Relationship." December 12, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/the-main-theses-of-healthy-relationship/.

StudyCorgi . 2021. "The Main Theses of Healthy Relationship." December 12, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/the-main-theses-of-healthy-relationship/.

This paper, “The Main Theses of Healthy Relationship”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: December 29, 2021 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Why Communication In Relationships Is So Important

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Ivy Kwong, LMFT, is a psychotherapist specializing in relationships, love and intimacy, trauma and codependency, and AAPI mental health.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Ivy_Kwong_headshot_1000x1000-8cf49972711046e88b9036a56ca494b5.jpg)

Willie B. Thomas / Getty Images

What Kind of Communicator Are You?

- Why Communication Matters

- Limitations

- Characteristics

- Communication Problems

- Improve Your Communication

When to Get Help

Communication is vital for healthy relationships . Being able to talk openly and honestly with the people in your life allows you to share, learn, respond, and forge lasting bonds. This is a vital part of any relationship, including those with friends and family, but it can be particularly important in romantic relationships.

At a Glance

While all relationships are different and each one has its own ups and downs, being able to talk to your partner means that you'll be able to share your worries, show support for one another, and work together to handle conflict more effectively.

If the communication in your relationship is lacking, you can strengthen it by being present in your conversations, focusing on your relationship, and really listening to what your partner has to say.

Our fast and free communication styles quiz can help give you some insight into how you interact with others and what it could mean for your interpersonal relationships, both at work and at home.

Benefits of Communication in Relationships

According to Dr. John Gottman, a clinical psychologist and founder of the Gottman Institute, a couple's communication pattern can often predict how successful a relationship will be. Good communication can help enhance your relationship in a variety of ways:

Less Rumination

Communication in relationships can minimize rumination . Instead of stewing over negative feelings, good communication allows people to discuss their concerns and resolve them in a more positive, effective way.

Greater Intimacy

Good communication in relationships also fosters intimacy. Forming a close emotional connection with another person requires a mutual give-and-take when it comes to sharing things about yourself and listening to the other person.

This reciprocal self-disclosure means talking about your experiences, beliefs, values, opinions, and expectations. In order to do this, you both need to possess communication skills that foster this connection and allow it to grow and deepen with time.

Less Conflict

Communication in relationships reduces and resolves conflict. Every relationship is bound to experience conflict from time to time.

When you are able to talk about your problems in an open and honest way, however, you can resolve arguments and disagreements more readily.

Rather than getting caught up in a cycle of misunderstandings, hurt feelings, and emotional strife, you can address your problems and take steps to improve your relationship .

Communication Doesn't Solve Everything

While the common assumption has long been that if you want to improve your relationship, you should start by improving your communication, some research has suggested that the answer might not be so simple.

A study published in the Journal of Marriage and Family found that while there is certainly a connection between communication and relationship satisfaction, good communication alone doesn't definitively predict how happy you'll be in your relationships.

Other Factors Play a Role

Other factors—including how much interaction a couple has, the personality characteristics of each partner, and stress—all play a part in determining how satisfied people feel in their relationship.

Another study found that positive communication did not have a strong connection with relationship satisfaction over time. However, couples that reported less negative communication than usual and reported feeling more satisfied with their relationship than they usually did.

So while research suggests that communicating well isn't a guarantee for a happy relationship, there is plenty of research indicating that good communication skills enhance relationships and well-being in a number of ways.

Effective communication is one way to foster a positive, supportive relationship with your partner.

When you actively listen and respond to your partner (and they do the same for you), both of you are more likely to feel valued and cared for.

For example, one study found that when people feel that their partner values them, they are more likely to sleep better. And ultimately, feeling more valued, positive, and happy in your relationships can have a beneficial impact on your overall well-being.

Communication is just one part of a good relationship. Research suggests that people who are happy in their relationships are more likely to communicate well with one another.

Signs of Great Communication in Relationships

So what do experts mean when they talk about "good communication?" Are you and your partner both on the same page or are there signs that might indicate a problem in how you relate to one another?

First, it is important to think about what we mean by communication. On the surface, it involves the words that people use to convey information to one another.

But it can also involve other ways of transmitting information including tone of voice, body language , and other forms of nonverbal communication . In many cases, what you don’t say can mean just as much if not more than what you do say.

Some of the hallmarks of effective communication in relationships include:

- Active listening : Active listening involves being engaged in the conversation, listening attentively, and reflecting back on what people have said. It also involves asking for clarification when needed and avoiding making judgments.

- Not personalizing issues : When communicating in relationships, people who are good at it avoid personalizing their partner's actions. Instead, they focus on the situation and how things can be resolved.

- Using "I feel" statements : I-statements can be helpful in interpersonal conflicts. Instead of saying, "You never clean up after yourself," try using an I-statement like, "I feel uncomfortable when there is clutter accumulating around the house."

- Kindness : Kindness is important because it makes people feel cared for and understood.

- Being present : When talking with your partner, it is important to be fully present in the moment . Getting distracted by outside sources–including electronic distractions such as your phone–can lead to a lack of communication and a poor connection.

- Showing acceptance : Healthy communication is about accepting and validating the other person , even if you might not agree with them. When you communicate well with your partner, you’re able to recognize that people have a right to feel their feelings even if those emotions and reactions are different from your own.

Communicating well in relationships involves actively listening, avoiding judgments, and practicing kindness instead of trying to win the argument.

Signs of Poor Communication in Relationships

Some signs that your relationship is being negatively affected by communication problems include:

- Assuming that you know what your partner thinks or feels

- Constantly criticizing one another

- Engaging in passive-aggressive behaviors

- Feeling like you can't really talk to your partner

- Getting defensive when your partner tries to talk to you

- Giving each other the silent treatment

- Having the same arguments over and over without reaching a resolution

- Refusing to compromise or listen to the other person's perspective

- Stonewalling in order to avoid problems or conversations

It is also important to learn to recognize some of the more subtle signs of poor communication. This can include avoiding arguments for the sake of keeping the peace.

If you never disagree, it means that one of you is hiding what you really feel or think just to avoid a fight. This deprives you both of experiencing authentic, open, and honest discussions.

Withholding issues can be another common communication problem in relationships. Instead of having tough conversations with your partner, you might avoid the issue and then end up dumping all of your anger, irritation, worries, or problems on the other people in your life.

For example, when you don’t tell your partner you are upset, you might end up ranting to your friend about your frustrations. While this might provide you with an emotional outlet, it doesn’t do anything to resolve the problem. And it might result in passive-aggressive actions designed to "punish" your partner for not being able to read your mind.

Criticisms, defensiveness, silence, and feeling misunderstood are just a few signs of communication problems in a relationship. And a lack of arguing isn't necessarily a sign that you're communicating well. Instead, it may mean you are holding back in order to avoid conflict.

5 Ways to Improve Communication in Relationships

If you think that poor communication is having a negative impact on your relationship, there are strategies that can help you improve your connection.

Consider Your Attachment Style

Think about how your attachment style might affect your communication patterns. Attachment styles are your characteristic patterns of behavior in relationships. Your early attachment style, which emerges in childhood based on relationships with caregivers, can continue to affect how you behave and respond in adult romantic relationships.

If you have an insecure attachment style , you may be more likely to engage in communication patterns that can be seen as anxious or avoidant. Recognizing how your attachment style affects how you interact with your partner (and how your partner's style affects how they interact with you) can give you clues into what you might need to work on.

If you or your partner have an insecure attachment style, it can have an impact on how you communicate and interact with your partner. Knowing your style and being aware of how it may manifest as anxious or avoidant behavior can help you find ways to overcome less effective communication patterns.

Be Fully Present

In order to make sure that both of you are listening and understanding, minimize distractions and focus on being fully present when you are communicating. This might involve setting aside time each day to really focus on one another and talk about the events of the day and any concerns you may have.

Limiting your device use at certain times of day, such as during meals or at bedtime, can be a great way to focus on your partner without having your attention pulled in different directions.

Use "I" Statements

Sometimes the way that you talk to each other can play a major role in communication problems. If you are both focusing on arguing facts without talking about feelings, arguments can quickly turn into debates over who is "right" or who gets the last word.

Examples of "I" Statements

"I" statements are focused on what you are feeling instead of your partner’s behavior. For example, instead of saying, "You are never on time," you might say "I get worried when you don’t arrive on time."

Using this type of statement can help conversations seem less accusatory or blaming and instead help you and your partner focus on the emotions behind some of the issues you are concerned about.

Avoid Negative Communication Patterns

When you are tempted to engage in behavior like ignoring your partner, using passive-aggressive actions, or yelling, consider how your actions will negatively affect your relationship.

It isn’t always easy to change these patterns, since many of them formed in childhood, but becoming more aware of them can help you start to replace these destructive behaviors with healthier, more positive habits.

Focus on Your Relationship

While good communication is important, research suggests that it is just one of many factors that impact the success, duration, and satisfaction in relationships.

In fact, research seems to suggest that your satisfaction with your relationship might predict how well you and your partner communicate.

The more satisfied people are in their relationship, the more likely they are to openly talk about their thoughts, feelings, concerns, and problems with one another.

If you want to improve your communication, focusing on improving your relationship overall can play an important role.

There are many steps you can take to improve the communication in your relationship on your own, but there may be times that you feel like professional help might be needed. Couples therapy can be a great way to address communication problems that might be holding your relationship back.

A therapist can help identify unhelpful communication patterns, develop new coping techniques, and practice talking to one another in more effective ways. They can also address any underlying resentments or other mental health issues that might be having a detrimental impact on your relationship.

Keep in Mind

Effective communication in a relationship allows people to tell other people what they need and to respond to what their partner needs. It allows people to feel understood, validated, and connected to another person.

Always remember that the goal of communicating is to understand one another. It isn't about sweeping problems under the rug in order to prevent all conflict. Instead, focus on listening to understand and responding with empathy and care. If you and your partner are struggling with communication issues, consider talking to a therapist for advice and tips on how to cope.

Gottman J, Silver N. The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work . New York, NY: Crown Publishers; 1999.

Lavner JA, Karney BR, Bradbury TN. Does couples’ communication predict marital satisfaction, or does marital satisfaction predict communication?: couple communication and marital satisfaction . Journal of Marriage and Family . 2016;78(3):680-694. doi:10.1111/jomf.12301

Johnson MD, Lavner JA, Mund M, et al. Within-couple associations between communication and relationship satisfaction over time . Pers Soc Psychol Bull . 2022;48(4):534-549. doi:10.1177/01461672211016920

Selcuk E, Stanton SCE, Slatcher RB, Ong AD. Perceived partner responsiveness predicts better sleep quality through lower anxiety . Social Psychological and Personality Science . 2017;8(1):83-92. doi:10.1177/1948550616662128

Rogers SL, Howieson J, Neame C. I understand you feel that way, but I feel this way: the benefits of I-language and communicating perspective during conflict . PeerJ . 2018;6:e4831. doi:10.7717/peerj.4831

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Developing a Thesis Statement

Many papers you write require developing a thesis statement. In this section you’ll learn what a thesis statement is and how to write one.

Keep in mind that not all papers require thesis statements . If in doubt, please consult your instructor for assistance.

What is a thesis statement?

A thesis statement . . .

- Makes an argumentative assertion about a topic; it states the conclusions that you have reached about your topic.

- Makes a promise to the reader about the scope, purpose, and direction of your paper.

- Is focused and specific enough to be “proven” within the boundaries of your paper.

- Is generally located near the end of the introduction ; sometimes, in a long paper, the thesis will be expressed in several sentences or in an entire paragraph.

- Identifies the relationships between the pieces of evidence that you are using to support your argument.

Not all papers require thesis statements! Ask your instructor if you’re in doubt whether you need one.

Identify a topic

Your topic is the subject about which you will write. Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic; or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper.

Consider what your assignment asks you to do

Inform yourself about your topic, focus on one aspect of your topic, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts, generate a topic from an assignment.

Below are some possible topics based on sample assignments.

Sample assignment 1

Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II.

Identified topic

Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis

This topic avoids generalities such as “Spain” and “World War II,” addressing instead on Franco’s role (a specific aspect of “Spain”) and the diplomatic relations between the Allies and Axis (a specific aspect of World War II).

Sample assignment 2

Analyze one of Homer’s epic similes in the Iliad.

The relationship between the portrayal of warfare and the epic simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64.

This topic focuses on a single simile and relates it to a single aspect of the Iliad ( warfare being a major theme in that work).

Developing a Thesis Statement–Additional information

Your assignment may suggest several ways of looking at a topic, or it may name a fairly general concept that you will explore or analyze in your paper. You’ll want to read your assignment carefully, looking for key terms that you can use to focus your topic.

Sample assignment: Analyze Spain’s neutrality in World War II Key terms: analyze, Spain’s neutrality, World War II

After you’ve identified the key words in your topic, the next step is to read about them in several sources, or generate as much information as possible through an analysis of your topic. Obviously, the more material or knowledge you have, the more possibilities will be available for a strong argument. For the sample assignment above, you’ll want to look at books and articles on World War II in general, and Spain’s neutrality in particular.

As you consider your options, you must decide to focus on one aspect of your topic. This means that you cannot include everything you’ve learned about your topic, nor should you go off in several directions. If you end up covering too many different aspects of a topic, your paper will sprawl and be unconvincing in its argument, and it most likely will not fulfull the assignment requirements.

For the sample assignment above, both Spain’s neutrality and World War II are topics far too broad to explore in a paper. You may instead decide to focus on Franco’s role in the diplomatic relationships between the Allies and the Axis , which narrows down what aspects of Spain’s neutrality and World War II you want to discuss, as well as establishes a specific link between those two aspects.

Before you go too far, however, ask yourself whether your topic is worthy of your efforts. Try to avoid topics that already have too much written about them (i.e., “eating disorders and body image among adolescent women”) or that simply are not important (i.e. “why I like ice cream”). These topics may lead to a thesis that is either dry fact or a weird claim that cannot be supported. A good thesis falls somewhere between the two extremes. To arrive at this point, ask yourself what is new, interesting, contestable, or controversial about your topic.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times . Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Derive a main point from topic

Once you have a topic, you will have to decide what the main point of your paper will be. This point, the “controlling idea,” becomes the core of your argument (thesis statement) and it is the unifying idea to which you will relate all your sub-theses. You can then turn this “controlling idea” into a purpose statement about what you intend to do in your paper.

Look for patterns in your evidence

Compose a purpose statement.

Consult the examples below for suggestions on how to look for patterns in your evidence and construct a purpose statement.

- Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis

- Franco turned to the Allies when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from the Axis

Possible conclusion:

Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: Franco’s desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power.

Purpose statement

This paper will analyze Franco’s diplomacy during World War II to see how it contributed to Spain’s neutrality.

- The simile compares Simoisius to a tree, which is a peaceful, natural image.

- The tree in the simile is chopped down to make wheels for a chariot, which is an object used in warfare.

At first, the simile seems to take the reader away from the world of warfare, but we end up back in that world by the end.

This paper will analyze the way the simile about Simoisius at 4.547-64 moves in and out of the world of warfare.

Derive purpose statement from topic

To find out what your “controlling idea” is, you have to examine and evaluate your evidence . As you consider your evidence, you may notice patterns emerging, data repeated in more than one source, or facts that favor one view more than another. These patterns or data may then lead you to some conclusions about your topic and suggest that you can successfully argue for one idea better than another.

For instance, you might find out that Franco first tried to negotiate with the Axis, but when he couldn’t get some concessions that he wanted from them, he turned to the Allies. As you read more about Franco’s decisions, you may conclude that Spain’s neutrality in WWII occurred for an entirely personal reason: his desire to preserve his own (and Spain’s) power. Based on this conclusion, you can then write a trial thesis statement to help you decide what material belongs in your paper.

Sometimes you won’t be able to find a focus or identify your “spin” or specific argument immediately. Like some writers, you might begin with a purpose statement just to get yourself going. A purpose statement is one or more sentences that announce your topic and indicate the structure of the paper but do not state the conclusions you have drawn . Thus, you might begin with something like this:

- This paper will look at modern language to see if it reflects male dominance or female oppression.

- I plan to analyze anger and derision in offensive language to see if they represent a challenge of society’s authority.

At some point, you can turn a purpose statement into a thesis statement. As you think and write about your topic, you can restrict, clarify, and refine your argument, crafting your thesis statement to reflect your thinking.

As you work on your thesis, remember to keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Sometimes your thesis needs to evolve as you develop new insights, find new evidence, or take a different approach to your topic.

Compose a draft thesis statement

If you are writing a paper that will have an argumentative thesis and are having trouble getting started, the techniques in the table below may help you develop a temporary or “working” thesis statement.

Begin with a purpose statement that you will later turn into a thesis statement.

Assignment: Discuss the history of the Reform Party and explain its influence on the 1990 presidential and Congressional election.

Purpose Statement: This paper briefly sketches the history of the grassroots, conservative, Perot-led Reform Party and analyzes how it influenced the economic and social ideologies of the two mainstream parties.

Question-to-Assertion

If your assignment asks a specific question(s), turn the question(s) into an assertion and give reasons why it is true or reasons for your opinion.

Assignment : What do Aylmer and Rappaccini have to be proud of? Why aren’t they satisfied with these things? How does pride, as demonstrated in “The Birthmark” and “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” lead to unexpected problems?

Beginning thesis statement: Alymer and Rappaccinni are proud of their great knowledge; however, they are also very greedy and are driven to use their knowledge to alter some aspect of nature as a test of their ability. Evil results when they try to “play God.”

Write a sentence that summarizes the main idea of the essay you plan to write.

Main idea: The reason some toys succeed in the market is that they appeal to the consumers’ sense of the ridiculous and their basic desire to laugh at themselves.

Make a list of the ideas that you want to include; consider the ideas and try to group them.

- nature = peaceful

- war matériel = violent (competes with 1?)

- need for time and space to mourn the dead

- war is inescapable (competes with 3?)

Use a formula to arrive at a working thesis statement (you will revise this later).

- although most readers of _______ have argued that _______, closer examination shows that _______.

- _______ uses _______ and _____ to prove that ________.

- phenomenon x is a result of the combination of __________, __________, and _________.

What to keep in mind as you draft an initial thesis statement

Beginning statements obtained through the methods illustrated above can serve as a framework for planning or drafting your paper, but remember they’re not yet the specific, argumentative thesis you want for the final version of your paper. In fact, in its first stages, a thesis statement usually is ill-formed or rough and serves only as a planning tool.

As you write, you may discover evidence that does not fit your temporary or “working” thesis. Or you may reach deeper insights about your topic as you do more research, and you will find that your thesis statement has to be more complicated to match the evidence that you want to use.

You must be willing to reject or omit some evidence in order to keep your paper cohesive and your reader focused. Or you may have to revise your thesis to match the evidence and insights that you want to discuss. Read your draft carefully, noting the conclusions you have drawn and the major ideas which support or prove those conclusions. These will be the elements of your final thesis statement.

Sometimes you will not be able to identify these elements in your early drafts, but as you consider how your argument is developing and how your evidence supports your main idea, ask yourself, “ What is the main point that I want to prove/discuss? ” and “ How will I convince the reader that this is true? ” When you can answer these questions, then you can begin to refine the thesis statement.

Refine and polish the thesis statement

To get to your final thesis, you’ll need to refine your draft thesis so that it’s specific and arguable.

- Ask if your draft thesis addresses the assignment

- Question each part of your draft thesis

- Clarify vague phrases and assertions

- Investigate alternatives to your draft thesis

Consult the example below for suggestions on how to refine your draft thesis statement.

Sample Assignment

Choose an activity and define it as a symbol of American culture. Your essay should cause the reader to think critically about the society which produces and enjoys that activity.

- Ask The phenomenon of drive-in facilities is an interesting symbol of american culture, and these facilities demonstrate significant characteristics of our society.This statement does not fulfill the assignment because it does not require the reader to think critically about society.

Drive-ins are an interesting symbol of American culture because they represent Americans’ significant creativity and business ingenuity.

Among the types of drive-in facilities familiar during the twentieth century, drive-in movie theaters best represent American creativity, not merely because they were the forerunner of later drive-ins and drive-throughs, but because of their impact on our culture: they changed our relationship to the automobile, changed the way people experienced movies, and changed movie-going into a family activity.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast-food establishments, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize America’s economic ingenuity, they also have affected our personal standards.

While drive-in facilities such as those at fast- food restaurants, banks, pharmacies, and dry cleaners symbolize (1) Americans’ business ingenuity, they also have contributed (2) to an increasing homogenization of our culture, (3) a willingness to depersonalize relationships with others, and (4) a tendency to sacrifice quality for convenience.

This statement is now specific and fulfills all parts of the assignment. This version, like any good thesis, is not self-evident; its points, 1-4, will have to be proven with evidence in the body of the paper. The numbers in this statement indicate the order in which the points will be presented. Depending on the length of the paper, there could be one paragraph for each numbered item or there could be blocks of paragraph for even pages for each one.

Complete the final thesis statement

The bottom line.

As you move through the process of crafting a thesis, you’ll need to remember four things:

- Context matters! Think about your course materials and lectures. Try to relate your thesis to the ideas your instructor is discussing.

- As you go through the process described in this section, always keep your assignment in mind . You will be more successful when your thesis (and paper) responds to the assignment than if it argues a semi-related idea.

- Your thesis statement should be precise, focused, and contestable ; it should predict the sub-theses or blocks of information that you will use to prove your argument.

- Make sure that you keep the rest of your paper in mind at all times. Change your thesis as your paper evolves, because you do not want your thesis to promise more than your paper actually delivers.

In the beginning, the thesis statement was a tool to help you sharpen your focus, limit material and establish the paper’s purpose. When your paper is finished, however, the thesis statement becomes a tool for your reader. It tells the reader what you have learned about your topic and what evidence led you to your conclusion. It keeps the reader on track–well able to understand and appreciate your argument.

Writing Process and Structure

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Getting Started with Your Paper

Interpreting Writing Assignments from Your Courses

Generating Ideas for

Creating an Argument

Thesis vs. Purpose Statements

Architecture of Arguments

Working with Sources

Quoting and Paraphrasing Sources

Using Literary Quotations

Citing Sources in Your Paper

Drafting Your Paper

Generating Ideas for Your Paper

Introductions

Paragraphing

Developing Strategic Transitions

Conclusions

Revising Your Paper

Peer Reviews

Reverse Outlines

Revising an Argumentative Paper

Revision Strategies for Longer Projects

Finishing Your Paper

Twelve Common Errors: An Editing Checklist

How to Proofread your Paper

Writing Collaboratively

Collaborative and Group Writing

- Open access

- Published: 13 December 2022

Learning how relationships work: a thematic analysis of young people and relationship professionals’ perspectives on relationships and relationship education

- Simon Benham-Clarke ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6053-9804 1 , 2 ,

- Jan Ewing ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1420-1116 3 ,

- Anne Barlow ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7628-4589 2 &

- Tamsin Newlove-Delgado ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5192-3724 2

BMC Public Health volume 22 , Article number: 2332 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

5171 Accesses

2 Citations

170 Altmetric

Metrics details

Relationships in various forms are an important source of meaning in people’s lives that can benefit their health, wellbeing and happiness. Relationship distress is associated with public health problems such as alcohol misuse, obesity, poor mental health, and child poverty, whilst safe, stable, and nurturing relationships are potential protective factors. Despite increased emphasis on Relationship Education in schools, little is known about the views of relationship professionals on relationship education specifically, and how this contrasts with the views of young people (YP). This Wellcome Centre for the Cultures and Environments of Health funded Beacon project seeks to fill this gap by exploring their perspectives and inform the future development of relationship education.

We conducted focus groups with YP ( n = 4) and interviews with relationship professionals ( n = 10). The data was then thematically analysed.

Themes from YP focus groups included: ‘Good and bad relationships’; ‘Learning about relationships’; ‘the role of schools’ and ‘Beyond Relationship Education’. Themes from interviews with relationship professionals included: ‘essential qualities of healthy relationships’; ‘how YP learn to relate’ and ‘the role of Relationship Education in schools’.

Conclusions

YP and relationship professionals recognised the importance of building YP’s relational capability in schools with a healthy relationship with oneself at its foundation. Relationship professionals emphasised the need for a developmental approach, stressing the need for flexibility, adaptability, commitment and resilience to maintain relationships over the life course. YP often presented dichotomous views, such as relationships being either good or bad relationships, and perceived a link between relationships and mental health. Although not the focus of current curriculum guidance, managing relationship breakdowns and relationship transitions through the life course were viewed as important with an emphasis on building relational skills. This research suggests that schools need improved Relationship Education support, including specialist expertise and resources, and guidance on signposting YP to external sources of help. There is also potential for positive relationship behaviours being modelled and integrated throughout curriculums and reflected in a school’s ethos. Future research should explore co-development, evaluation and implementation of Relationship Education programmes with a range of stakeholders.

Peer Review reports

Relationships in various forms are an important source of meaning in people’s lives that can benefit their health, well-being and happiness [ 1 ]. ‘A ‘distressed’ relationship is one with a severe level of relationship problems, which has a clinically significant negative impact on their partner’s wellbeing. Those in ‘distressed’ relationships report regularly considering separation/divorce, quarrelling, regretting being in their relationship, being unhappy in their relationship, for example’ [ 2 ]. A growing evidence base shows that distress in relationships is associated with public health priorities such as alcohol misuse, obesity, mental health problems, and child poverty, whilst safe, stable, and nurturing relationships are potential protective factors [ 3 , 4 , 5 ]. For young people (YP), there is evidence of a significant link between well-being and romantic relationships, suggesting that these relationships (when healthy) can positively influence self-concept, social integration and social support [ 6 ]. However, research indicates that some early romantic relationships can act as stressors regardless of their nature, whilst YP are negotiating other developmental tasks. For example, Olson and Crosnow’s longitudinal analysis [ 7 ] suggested that adolescent romantic relationships are associated with increased depressive symptomatology, particularly for girls.

The term ‘relationship’ has been defined as an enduring association between two persons [ 8 ]. The terms ‘healthy’ or ‘quality’ relationships have been described, defined and measured in various ways. They are ‘complex and ambiguous constructs’ with factors varying for each type of relationship [ 9 ]. Attempts to reach a definition tend to focus on interaction and positive and negative relationship characteristics and behaviours such as the existence or absence of caregiving, respect, support, emotional regulation, and the ability to learn from experience [ 10 , 11 ]. It has been theorised that early intervention and the development of these relationship skills in YP may allow them to negotiate early romantic relationships better as well as improve the quality and/or health of adult relationships, normalise help-seeking behaviour and prevent or manage relationship breakdown [ 12 , 13 ]. In their 2014 Manifesto, the Relationships Alliance Footnote 1 called upon The Department for Education (DfE) “to develop standards for those delivering RSE (Relationship and Sex Education) and set an expectation that schools recognise that developing relational capability is an important function of education and a child’s future” [ 14 ]. Relational capability refers to the capacity to form and maintain safe, stable, and nurturing relationships [ 15 ].

In 2019, DfE published statutory guidance in England on Relationship and Sex Education (RSE) [ 16 ], following the passing of the Children and Social Work Act 2017 [ 17 ]. The new Act stipulates Footnote 2 that pupils should learn about safety in forming and maintaining relationships; the characteristics of ‘healthy’ relationships and how relationships may affect physical and mental health and well-being. However, schools have been largely left to work out how to deliver this sensitive area of education, with little practical content guidance to date [ 18 ]. Skills for ‘healthy’ romantic relationships have also been relatively neglected both in research and practice. There are several programmes developed for YP that teach about relationships, but those that currently exist are mainly from the US, and generally focussed on sexual health or relationship violence [ 19 , 20 ]. Similarly, research with YP on their perspectives of RSE mostly focus on their views on sex education [ 21 ]. Therefore, despite the increased emphasis on delivering RSE in schools, Footnote 3 little is known about how YP view this aspect of the curriculum, or what outcomes they feel it should deliver. This is an important gap to fill to engage YP with the curriculum, and to lay the groundwork for the design, adaptation and evaluation of healthy relationship programmes. Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) work conducted in a prior project [ 22 ] by some of the authors demonstrated a great appetite in YP to learn more about relationships.

Our Beacon project, funded by The Wellcome Centre for the Cultures and Environments of Health, is focussed on ‘Transforming relationships and relationship transitions with and for the next generation’ in two strands (Healthy Relationship Education (HeaRE) and Healthy Relationship Transitions (HeaRT)). As part of the project, we conducted qualitative interviews and focus groups with young people and relationship professionals, with the aims of exploring their perspectives on relationships and relationship education. This paper presents and integrates the findings of these studies, to inform the development of future Relationship Education.

Recruitment

YP were recruited from a convenience sample of community groups and schools in South-West England, across urban, suburban and rural settings. Young people were contacted through school and youth group leaders, who made the first approach to participants. YP consented for themselves if aged 16 and over; for under 16 s, both parent and young person consent was sought. The YP formed four focus groups with a total of 24 participants. The two focus groups conducted in schools were with Years 9 and 10 pupils (aged 14 to 16 years). Following PPI consultation, these were set up separately for boys and girls; one group with eight girls and one with seven boys. The community group focus groups included young people aged between 14 and 18 and had one group with four boys and one with two boys and three girls.

A purposive sampling strategy was used to recruit the relationship professionals, seeking out key people who are likely to provide rich sources of information or data [ 22 ]. Here, ten nationally based relationship professionals (three men and seven women) were purposively sampled for their recognised expertise in the field of romantic relationships either through their research interests or because they were psychotherapists or counsellors. All had a minimum of 15 years of experience in their chosen field, and most had many more. Consent in writing or by audio recording was obtained before the interview.

Focus groups with YP were used due to their suitability for exploring ideas within their social context [ 23 , 24 ]. The topic guides were developed and refined through accompanying consultations with YP in our Youth Panel PPI sessions. Content included questions and prompts around views on relationships, experiences of Relationship Education, and what YP wanted to get from participating in Relationship Education. The first two focus groups were conducted face-to-face in February 2020. Due to COVID-19, the procedure had to be adapted for the latter two, which were conducted on Microsoft Teams in the summer of 2020. The focus groups were audio-recorded and conducted by TND and SBC with each lasting approximately an hour.

Semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted with the relationship professionals by JE. An interview schedule for the relationship professionals was devised, piloted and refined in team discussions. The topics relevant to this paper were the views of the relationship professionals on what constituted an enduring, mutually satisfying intimate partner relationship, how older children can learn the skills needed to identify healthy and unhealthy relationships and the role, content and delivery of Relationship Education. The interviews were conducted by telephone since there are no significant differences between telephone and face-to-face interview data [ 25 ] and given COVID-19 restrictions at the time. The duration of each interview was 64 min on average.

The focus groups with YP and the interviews with professionals were analysed separately rather than in combination, as interview schedules and formats were different for both. Transcription was conducted by an approved University service. NVivo 12 was used to manage the data, analysed using the thematic approach described by Braun and Clark [ 26 ]. In both datasets, a second author coded the first transcripts. Variations between coders were discussed by the team. Themes were developed separately for the YP and the relationship professionals; in this paper we present and compare these themes, identifying difference and similarities in the Discussion section.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was gained from the University of Exeter Medicine School (UEMS) Research Ethics Committee (reference: Jun20/D/229∆1) for the research with YP and the University of Exeter College of Social Sciences and International Studies Research Ethics Committee for research involving relationship professionals (reference: 201,920–017).

The ethical approach we took is based on the successful and tested approach used by the Shackleton Project (UEMS ethics number 201617–018). We developed a protocol, agreed with teachers and community group leaders, for actions to be taken should a participant appear distressed, wish to withdraw, or should concerns be raised. We were highly aware that this could be a sensitive area, and emphasised to participants that they could withdraw at any point, as well as ensuring that they were aware of sources of support, and of confidential ways to contact the researchers, teachers, or community group leaders (e.g. through private chat on Teams) if they needed to. Researchers were alert throughout the groups for verbal and non-verbal signs that YP might wish to leave or take a break from the discussions, and strategic pauses or break points were included to facilitate this. The researchers were both experienced and well placed to conduct the focus groups with YP. The topics discussed with YP were framed to young people as being around ‘healthy relationships’ and existing RSE guidance. Our approach throughout the research was to engage young people in helping us to understand how Relationship Education could be improved for all YP in general. We used and explained Chatham House Rules to participants but were aware that this is not sufficient as the only measure. Therefore, we used appropriate distancing techniques, discouraging and steering conversations away from personal disclosures as needed and framing questions accordingly, for example, ‘what should young people get out of Relationship Education? We developed a protocol, agreed with teachers and community group leaders, for actions to be taken should a participant appear distressed, wish to withdraw, or should concerns be raised.

All names referred to below are pseudonyms.

- Young people

‘Good’ and ‘bad’ relationships

When asking what was meant by relationships YP appeared to be most comfortable and forthcoming in discussing relationships using dichotomous terms. Typically, relationships were categorised as positive or negative, such as good, bad, right, wrong, comfortable, uncomfortable, successful, unsuccessful, healthy and unhealthy. There was also a frequently expressed concept of ‘normal’ versus ‘abnormal’ relationships, which linked to a desire to be taught how to have a ‘normal relationship’, although few participants challenged this.

’Like there are bad sides of a relationship, there’s the good side of the relationship’. (Male) ’I don’t think I was ever taught in school about what a normal relationship is or how a relationship works’. (Male) ‘… I don’t want to be too forceful in this cookie-cutter idea of what good and bad relationships are, ... people are free to do what they want’. (Female)

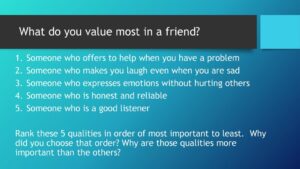

YP attempted to define the qualities involved in ‘healthy’ or ‘normal’ relationships differently. Trust, respect and having common ground were often mentioned. Communication was also seen as being crucial, which linked to handling conflict the ‘right’ way. They also recognised that these qualities were involved in the different stages of relationships.

‘Well, I think a lot about healthy relationships in general is to do with communication. And starting a relationship and establishing what you want from the relationship is very important, and the same with finishing a relationship and saying to someone “I’m not happy with this because of this, this and this … . So, I think all of those stages really are about communication’. (Female)

Some YP introduced different sources of influence on relationships. They attributed importance to the role of upbringing and parental models. Again, ‘normality’ in relationships was present as a concept.

‘I think our parents are our closest role models really’. (Male) ‘ if you’ve been brought up in a domestic violence place or household, you’re never going to know until you grow up “Oh, that’s not okay, that’s not a normal thing ’. (Male)

In response to a question about how Relationship Education might help young people in different stages of their lives others commented on the influence of fairy tales, and Disney in particular; this was linked most strongly to gender roles and expectations in relationships.

‘I think it actually does create this toxic image to some degree… it’s very much the female is feeble, and she must be saved by the male, and it kind of creates a toxic masculinity’. (Female) ’It’s embedded into our heads that it’s always Prince Charming and it’s always the prince and the princess … you don’t understand it until you actually get to it, and that’s when you realise that it’s not like Disney movies or anything ...’. (Female).

Participants recognised that these ‘bad’ relationships early in life could have long-lasting impacts, including on mental health. This extended to the relationships between parents and children.

‘I’ve got so many friends who have fallen down mental health spirals due to bad relationships’. (Female) “Some parents, because they had such a rough childhood, treat their children the same thinking that it is the right way’. (Female).

Learning about relationships

There was a general feeling from many participants that Relationship Education would have a range of benefits for YP, across different kinds of relationships. Communication and conflict were critical areas where participants felt that there were skills, or ways of coping or doing things that they could learn.

’how to communicate effectively with our peers and partners, family members’. (Female) ’ [I would like to learn] Probably how to defuse an argument, … instead of having to shout at each other and maybe possibly break stuff and maybe even harm each other, and you can talk about it responsibly’. (Male)

Some of the desired outcomes involved learning how to manage different stages in relationships; for example, how to sustain happy relationships, and how to end relationships that could not be sustained, and cope with the aftermath. There was also a sense that they were sometimes taught about ‘red flags’ (signs that relationships are unhealthy), but not how then to end the relationships.

’ the basic foundations of relationships, like how to keep it running, happy…’. (Male) ’if you’ve tried to maintain them but it… keeps happening, you just need to know how to end it nicely’. (Male) ’It is all well knowing the signs, but if you don’t know how to get out of an unhealthy relationship what is the point of knowing that it is unhealthy?’ (Female)

Some participants felt that focussing on relationships with themselves as a first step would have greater long-term benefits and could help YP avoid abusive relationships. One participant had their own experience of where they felt Relationship Education had an impact on their well-being but thought it would have been more beneficial if taught sooner.

’… that is a big thing for people our age more – accepting themselves rather than being in a relationship with other people. Their mental health more than other people’. (Female). ’ it has made me be more… conscious of my relationships and friendships, and I’m able to see which ones are bad and been able to cut off bad relationships…my mental health would be better now if that education had happened earlier’. (Female)

Some YP were thinking about how relationships might be challenged after leaving school or relocating, and how Relationship Education might prepare them for that, whilst others thought further ahead to when they might have families, and the potential impacts of Relationship Education in the longer term.

‘[after relationship education] If they were a parent, they would know how to treat their children and instead of the way their parents treated them, treat them a different way’. (Female)

The role of schools

YP saw schools as offering a neutral setting in which Relationship Education can be taught free from the potential influences and biases. This was thought to be critical, particularly for those who might have more challenging backgrounds, however a desire was expressed for a greater focus in schools on how relationships ‘work’ rather than on sex education.

‘people need to be taught about relationships in quite an unbiased environment, and school is the most likely place that’s going to happen’. (Female) ‘[Relationship lessons have] been very clinical. It’s not really teaching you anything to do with how the relationship works … For me, it’s just been the clinical side of sex, basically’. (Male)

In terms of how Relationship Education should be taught, YP emphasised the need to build on earlier learning and to revisit important content. Participants also felt that talking about family and peer relationships should come first, building up to later discussions about romantic relationships in later years at school, with some highlighting links between patterns of relationship behaviour.

’ I think they need to talk about our family relationships before they talk about future ones that we will have’. (Female) ’even in primary school, you have friendships and stuff. And if you’re getting bullied, you might not necessarily realise the way that they’re using you and being mean to you. And if you get used to that from a young age … it’s very hard to get out of that pattern of ending up with people who aren’t necessarily a good influence on you’. (Male)

Some YP were concerned about whether education about romantic relationships could put YP under pressure if it were too early, but others felt this could leave young people open to abuse.

‘… you can’t teach them too much at a young age, otherwise they’ll feel like there’s a lot of pressure on them when it comes to relationships’. (Male) ‘the younger ages are the most susceptible to abuse… because you don’t have the knowledge’. (Female) .

Beyond relationship education lessons

Discussions about teaching in school led to several YP voicing reservations about the limits of what Relationship Education could do, and acknowledgements of the complexity of whether relationships can be ‘taught’ at all.

‘I think first and foremost, it’s the role of the parents to teach about relationships. And I think all the school can really do is build on that’. (Male) ‘…to teach it, the first thing that you need to do as a teacher would be acknowledge that it isn’t necessarily something that can just be taught, and it’s more complicated than that ’. (Female)

There was a feeling amongst participants that schools could improve relationship outcomes for YP in other ways beyond the Relationship Education lesson, such as having someone to talk to, in person and in private. Others wanted signposting and information about sources of help outside the school setting.

‘I think it’s important, especially with young people, to have someone to speak to…Maybe a counsellor or something’. (Female) ‘it needs to offer information of places where people who might be in unhealthy relationships can go’. (Female)

YP felt help was needed beyond RSE especially when a relationship was ending, in terms of specialist and peer support, and some even made the case for access to ‘experts’ for relationship breakdown related problems.

‘it’s hard to teach people about how to deal with a break-up…But that’s why I think people who are experts on relationships should probably be better at it’. (Male)

Results- relationship professionals

Theme 1 – qualities of healthy relationships.

The quality of a healthy relationship most frequently cited by the relationship professionals was communicating well. As Rosemary Allen put it.

’the ability to be able to express what you think, what you need and to be able to hear the other person… being able to… adapt language so that you are using the tone and the quality and the vocabulary that gets across what you need to say and being sure that it is understood’.

Secondly, an ability to adapt was thought to be critical, and this required the couple to be flexible – sufficiently flexible to learn from one another but also to adapt to life’s transitions such as having a baby or children leaving home, which Alexander Ingles said depended on a.

‘ flexibility of internal world. It's about whether one is potentially available for development throughout life’.

The skills needed to adapt can be learned, and some potentially ‘unpromising’ relationships can flourish provided one person in the couple is sufficiently skilled and flexible at the outset. The relationship professionals agreed that couples who have the degree of flexibility required, such that their relationships thrive over time, tend to be ‘developmental’ in outlook that is, they expect to have to work at their relationship. As Kay Eagles explained.

‘… not giving up… you have to work at relationships, they don't just happen… people change as they get older and relationships change, and the nature of relationships change all the time… the… falling in love bit is very much just… the glossy part at the beginning but doesn't necessarily give you the skills for a long, healthy relationship’.

Fun and friendship were viewed as a necessity by many relationship professionals, not least because this gave a bedrock to come back to if couples begin to drift apart. Alongside this need to prioritise the relationship was a recognition of the need to maintain a sense of self. One of the relationship professionals described this concern for the self and the other as ‘ like a dance’ . As Jacob Beardsley put it, what is critical is.

’the importance of looking after yourself in a relationship, thinking about yourself as a separate person as well as nourishing and caring for the relationship’.

The relationship professionals distinguished the skills needed to initiate a healthy relationship and those needed to sustain it. The former included having: realistic expectations, a sense of self-worth, sufficient self-awareness to judge compatibility, well-developed communication skills and an ability to give and receive support within the relationship. The latter also included good communication skills as well as empathy, flexibility, likeability, commitment, respect, altruism, reciprocity and, in particular, resilience.

Theme 2—learning to relate

As might be expected, the relationship professionals spoke at length about the importance of good early caregiving in building the capacities of YP to form and maintain healthy relationships of their own. Positive early care, usually from parents, and the witnessing of a healthy, well-functioning relationship between parents was described variously as ‘ the building blocks’ (Margot Hendon),’ the architecture’ (Clara Farley) or’ the template’ (Fran Clarkson) for YP to learn relationship skills. The relationship professionals emphasised that a poor beginning did not mean that YP were doomed to make poor relationship choices or find maintaining relationships impossible. For some, positive other role models, grandparents or a teacher, might.

‘mediate some of those original depravations’. (Alexander Ingle).

For others, counselling (preferably at a young age) was said to help YP gain skills that are not being modelled in the home or help YP understand that their parents’ behaviour is unhealthy.

Whilst a minority thought there was a place for peer mentoring and learning from one's peers more generally, several relationship professionals expressed concerns at the calibre of the training given to peer mentoring, the misinformation that peers can impart and the potential lack of objectivity of one’s peers.

Several relationship professionals spoke of the changes that would be needed at a macro level to cultivate an environment that.

‘enables, or even supports individuals to establish and nurture relationships’. (Margot Hendon).

Theme 3 – teaching about relationships in schools

While young people’s families were seen as the primary source of learning about healthy relationships, there was clear support for schools’ role to augment this. Relationship professionals thought that there were key transition moments in life, getting married or having a baby, where people are receptive to learning relationship skills, but that schools had a critical role in teaching and embedding critical skills around initiating and maintaining a healthy relationship.

There was strong support for Relationship Education to start early, preferably in primary schools, exploring what a healthy friendship and relating well to others looks like before moving onto romantic relationships, which would give YP vital life skills. Starting early, in primary schools and with counselling support where needed, was thought to be particularly important for YP whose parents were locked in conflict.

’ Modules that stress good relating from the very beginning … Once you get [skills to relate well to others] in your fold, and once you have got your template for good relating, it doesn't matter whether it's love relationships or with your teacher or with your friends or with anyone ’. (Rosemary Allen) ’ it is harder to unpick some of those really entrenched beliefs around relationships and things the longer it goes on ’ (Shelley Jackson)

Regarding content for a Relationship Education curriculum, teaching skills such as relating, communication, empathy, respect, conflict resolution and repair and ending relationships kindly and safely were highlighted. There was general agreement that these skills were teachable and that YP needed opportunities to rehearse using these skills to help them to recognise, for example, key turning points in interactions which leads some to end positively and others not. Therefore, there was strong support from the relationship professionals for RSE to be interactive and participatory, giving YP the opportunity to learn and try out vital communication skills in RSE by practising listening and mirroring what is heard in a non-conflict discussion.

’ [engaging] with an interaction that they can see somebody else having and they can then have input into trying to understand why the interaction went in the direction it went and how it might have gone differently and had different endings is… powerful’ . (Margot Hendon)

Regarding delivery of the teaching, Clara Farley felt that if Relationship Education lessons were to take place within schools, they needed to be ’ brilliantly led’ with ’ vivid and interesting materials’ , but she felt that schools did not have such material available to them. Others expressed reservations at asking teachers who may be experiencing difficulties in their own relationship to be responsible for Relationship Education in school. Another favoured external specialists to deliver Relationship Education, which was suggested as having added benefits.

’young people are more likely to explore things, open up and be honest with someone that they perhaps haven't seen before, might not see again or see now and again around school. They will be more likely to share and explore their own thoughts than if they were with their own form teacher doing those things’. (Shelly Jackson)

The relationship professionals were also in agreement that the emphasis of Relationship Education should be on teaching about healthy relationships in an inclusive way, which assists those in relationships that may be unhealthy because it allows them to reflect on differences.

’ [Relationships] come in all different shapes and sizes and sexual orientation and everything else, but nevertheless I think that it is possible to talk about at least, explore what a healthy relationship looks like in its many different forms ’. (Jacob Beardsley)

Several relationship professionals spoke of the need for excellent pastoral care and counselling within schools for YP with particular issues around relationships. Kay Eagles felt that Relationship Education should not just be limited to intimate relationships but relationships more widely to include components of respect, valuing and caring for others. Echoing the views of others, Alexander Ingles stressed the need for the ethos of the school to complement the messages within Relationship Education which should encourage YP to ask questions, with support readily available within schools.

‘[Relationship Education] can only work if it's in the context of a good school in a broad sense’. (Alexander Ingles)

Four main themes were presented from our focus groups with YP. The first, ‘Good and bad relationships’, presents YP’s views on romantic relationships, and the influences they recognised from parents and culture. The second, ‘Learning about relationships’, explores participant’s views of the benefits of Relationship Education and the skills they want to develop.

The third theme, ‘the role of schools’, is about experiences of Relationship Education teaching in the school setting and how and when this should be taught. The final theme of ‘Beyond Relationship Education’ focuses on some of the limitations of teaching relationships, and YP’s needs for support beyond the classroom. From the interviews with relationship professionals, we identified three relevant themes: what they viewed as the essential qualities of healthy relationships; how YP learn to relate (primarily through observing the parental role model) and the role that Relationship Education in schools might have in teaching YP how to instigate and maintain a healthy relationship. Many of the views of YP and relationship professionals were similar, but there were areas of contrast and variations in emphasis. Below, we discuss some of the key findings, drawing out implications for public health and education policy and practice.