Qualitative Research 101: Interviewing

5 Common Mistakes To Avoid When Undertaking Interviews

By: David Phair (PhD) and Kerryn Warren (PhD) | March 2022

Undertaking interviews is potentially the most important step in the qualitative research process. If you don’t collect useful, useable data in your interviews, you’ll struggle through the rest of your dissertation or thesis. Having helped numerous students with their research over the years, we’ve noticed some common interviewing mistakes that first-time researchers make. In this post, we’ll discuss five costly interview-related mistakes and outline useful strategies to avoid making these.

Overview: 5 Interviewing Mistakes

- Not having a clear interview strategy /plan

- Not having good interview techniques /skills

- Not securing a suitable location and equipment

- Not having a basic risk management plan

- Not keeping your “ golden thread ” front of mind

1. Not having a clear interview strategy

The first common mistake that we’ll look at is that of starting the interviewing process without having first come up with a clear interview strategy or plan of action. While it’s natural to be keen to get started engaging with your interviewees, a lack of planning can result in a mess of data and inconsistency between interviews.

There are several design choices to decide on and plan for before you start interviewing anyone. Some of the most important questions you need to ask yourself before conducting interviews include:

- What are the guiding research aims and research questions of my study?

- Will I use a structured, semi-structured or unstructured interview approach?

- How will I record the interviews (audio or video)?

- Who will be interviewed and by whom ?

- What ethics and data law considerations do I need to adhere to?

- How will I analyze my data?

Let’s take a quick look at some of these.

The core objective of the interviewing process is to generate useful data that will help you address your overall research aims. Therefore, your interviews need to be conducted in a way that directly links to your research aims, objectives and research questions (i.e. your “golden thread”). This means that you need to carefully consider the questions you’ll ask to ensure that they align with and feed into your golden thread. If any question doesn’t align with this, you may want to consider scrapping it.

Another important design choice is whether you’ll use an unstructured, semi-structured or structured interview approach . For semi-structured interviews, you will have a list of questions that you plan to ask and these questions will be open-ended in nature. You’ll also allow the discussion to digress from the core question set if something interesting comes up. This means that the type of information generated might differ a fair amount between interviews.

Contrasted to this, a structured approach to interviews is more rigid, where a specific set of closed questions is developed and asked for each interviewee in exactly the same order. Closed questions have a limited set of answers, that are often single-word answers. Therefore, you need to think about what you’re trying to achieve with your research project (i.e. your research aims) and decided on which approach would be best suited in your case.

It is also important to plan ahead with regards to who will be interviewed and how. You need to think about how you will approach the possible interviewees to get their cooperation, who will conduct the interviews, when to conduct the interviews and how to record the interviews. For each of these decisions, it’s also essential to make sure that all ethical considerations and data protection laws are taken into account.

Finally, you should think through how you plan to analyze the data (i.e., your qualitative analysis method) generated by the interviews. Different types of analysis rely on different types of data, so you need to ensure you’re asking the right types of questions and correctly guiding your respondents.

Simply put, you need to have a plan of action regarding the specifics of your interview approach before you start collecting data. If not, you’ll end up drifting in your approach from interview to interview, which will result in inconsistent, unusable data.

2. Not having good interview technique

While you’re generally not expected to become you to be an expert interviewer for a dissertation or thesis, it is important to practice good interview technique and develop basic interviewing skills .

Let’s go through some basics that will help the process along.

Firstly, before the interview , make sure you know your interview questions well and have a clear idea of what you want from the interview. Naturally, the specificity of your questions will depend on whether you’re taking a structured, semi-structured or unstructured approach, but you still need a consistent starting point . Ideally, you should develop an interview guide beforehand (more on this later) that details your core question and links these to the research aims, objectives and research questions.

Before you undertake any interviews, it’s a good idea to do a few mock interviews with friends or family members. This will help you get comfortable with the interviewer role, prepare for potentially unexpected answers and give you a good idea of how long the interview will take to conduct. In the interviewing process, you’re likely to encounter two kinds of challenging interviewees ; the two-word respondent and the respondent who meanders and babbles. Therefore, you should prepare yourself for both and come up with a plan to respond to each in a way that will allow the interview to continue productively.

To begin the formal interview , provide the person you are interviewing with an overview of your research. This will help to calm their nerves (and yours) and contextualize the interaction. Ultimately, you want the interviewee to feel comfortable and be willing to be open and honest with you, so it’s useful to start in a more casual, relaxed fashion and allow them to ask any questions they may have. From there, you can ease them into the rest of the questions.

As the interview progresses , avoid asking leading questions (i.e., questions that assume something about the interviewee or their response). Make sure that you speak clearly and slowly , using plain language and being ready to paraphrase questions if the person you are interviewing misunderstands. Be particularly careful with interviewing English second language speakers to ensure that you’re both on the same page.

Engage with the interviewee by listening to them carefully and acknowledging that you are listening to them by smiling or nodding. Show them that you’re interested in what they’re saying and thank them for their openness as appropriate. This will also encourage your interviewee to respond openly.

Need a helping hand?

3. Not securing a suitable location and quality equipment

Where you conduct your interviews and the equipment you use to record them both play an important role in how the process unfolds. Therefore, you need to think carefully about each of these variables before you start interviewing.

Poor location: A bad location can result in the quality of your interviews being compromised, interrupted, or cancelled. If you are conducting physical interviews, you’ll need a location that is quiet, safe, and welcoming . It’s very important that your location of choice is not prone to interruptions (the workplace office is generally problematic, for example) and has suitable facilities (such as water, a bathroom, and snacks).

If you are conducting online interviews , you need to consider a few other factors. Importantly, you need to make sure that both you and your respondent have access to a good, stable internet connection and electricity. Always check before the time that both of you know how to use the relevant software and it’s accessible (sometimes meeting platforms are blocked by workplace policies or firewalls). It’s also good to have alternatives in place (such as WhatsApp, Zoom, or Teams) to cater for these types of issues.

Poor equipment: Using poor-quality recording equipment or using equipment incorrectly means that you will have trouble transcribing, coding, and analyzing your interviews. This can be a major issue , as some of your interview data may go completely to waste if not recorded well. So, make sure that you use good-quality recording equipment and that you know how to use it correctly.

To avoid issues, you should always conduct test recordings before every interview to ensure that you can use the relevant equipment properly. It’s also a good idea to spot check each recording afterwards, just to make sure it was recorded as planned. If your equipment uses batteries, be sure to always carry a spare set.

4. Not having a basic risk management plan

Many possible issues can arise during the interview process. Not planning for these issues can mean that you are left with compromised data that might not be useful to you. Therefore, it’s important to map out some sort of risk management plan ahead of time, considering the potential risks, how you’ll minimize their probability and how you’ll manage them if they materialize.

Common potential issues related to the actual interview include cancellations (people pulling out), delays (such as getting stuck in traffic), language and accent differences (especially in the case of poor internet connections), issues with internet connections and power supply. Other issues can also occur in the interview itself. For example, the interviewee could drift off-topic, or you might encounter an interviewee who does not say much at all.

You can prepare for these potential issues by considering possible worst-case scenarios and preparing a response for each scenario. For instance, it is important to plan a backup date just in case your interviewee cannot make it to the first meeting you scheduled with them. It’s also a good idea to factor in a 30-minute gap between your interviews for the instances where someone might be late, or an interview runs overtime for other reasons. Make sure that you also plan backup questions that could be used to bring a respondent back on topic if they start rambling, or questions to encourage those who are saying too little.

In general, it’s best practice to plan to conduct more interviews than you think you need (this is called oversampling ). Doing so will allow you some room for error if there are interviews that don’t go as planned, or if some interviewees withdraw. If you need 10 interviews, it is a good idea to plan for 15. Likely, a few will cancel , delay, or not produce useful data.

5. Not keeping your golden thread front of mind

We touched on this a little earlier, but it is a key point that should be central to your entire research process. You don’t want to end up with pages and pages of data after conducting your interviews and realize that it is not useful to your research aims . Your research aims, objectives and research questions – i.e., your golden thread – should influence every design decision and should guide the interview process at all times.

A useful way to avoid this mistake is by developing an interview guide before you begin interviewing your respondents. An interview guide is a document that contains all of your questions with notes on how each of the interview questions is linked to the research question(s) of your study. You can also include your research aims and objectives here for a more comprehensive linkage.

You can easily create an interview guide by drawing up a table with one column containing your core interview questions . Then add another column with your research questions , another with expectations that you may have in light of the relevant literature and another with backup or follow-up questions . As mentioned, you can also bring in your research aims and objectives to help you connect them all together. If you’d like, you can download a copy of our free interview guide here .

Recap: Qualitative Interview Mistakes

In this post, we’ve discussed 5 common costly mistakes that are easy to make in the process of planning and conducting qualitative interviews.

To recap, these include:

If you have any questions about these interviewing mistakes, drop a comment below. Alternatively, if you’re interested in getting 1-on-1 help with your thesis or dissertation , check out our dissertation coaching service or book a free initial consultation with one of our friendly Grad Coaches.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

13.2 Qualitative interview techniques

Learning objectives.

- Identify the primary goal of an in-depth interview

- Describe the unique characteristics of qualitative interview techniques

- Define the term “interview guide” and describe how to construct one

- Outline the guidelines for constructing good qualitative interview questions

- Describe the function and purpose of field notes and journals in qualitative research

- Identify the strengths and weaknesses of interviews

Qualitative interviews are sometimes called intensive or in-depth interviews. These interviews are considered semi-structured because the researcher has a particular topic for the respondent, but questions are open-ended and may not be asked in the exact same way or order to each respondent. The primary goal of an in-depth interview is to hear what respondents think is important about the topic at hand and to hear it in their own words. In this section, we’ll look at how to conduct qualitative interviews, analyze interview data, and identify some of the strengths and weaknesses of this method.

Constructing an interview guide

Respondents might think that qualitative interviews feel more like a conversation than an interview, but the researcher is guiding the conversation with the goal of gathering information from a respondent. Qualitative interviews use open-ended questions, which are questions that a researcher poses but does not provide answer options for. Open-ended questions are more demanding of participants than closed-ended questions for they require participants to come up with their own words, phrases, or sentences to respond.

In a qualitative interview, the researcher usually develops a guide in advance that they can refer to during the interview or memorize the interview takes place. An interview guide is a list of topics or questions that the interviewer hopes to cover during the course of an interview. It is called a guide because it is simply that—it is used to guide the interviewer, but it is not set in stone. Think of an interview guide like your agenda for the day or your to-do list: Both probably contain all the items you hope to check off or accomplish, though it probably won’t be the end of the world if you don’t accomplish everything on the list or if you don’t accomplish it in the exact order that you have it written down. Perhaps new events will come up that cause you to rearrange your schedule just a bit, or perhaps you simply won’t get to everything on the list.

Interview guides should outline issues that a researcher feels are likely to be important. Participants are asked to provide answers in their own words and to raise points they believe are important, so each interview is likely to flow a little differently. While the opening question in an in-depth interview may be the same across all interviews, the information that each participant shared will shape how the interview proceeds. This is what makes in-depth interviewing so exciting and rather challenging. It takes a skilled interviewer to be able to ask questions, listen to respondents, and pick up on cues about when to follow up, move on, or simply let the participant speak without guidance or interruption.

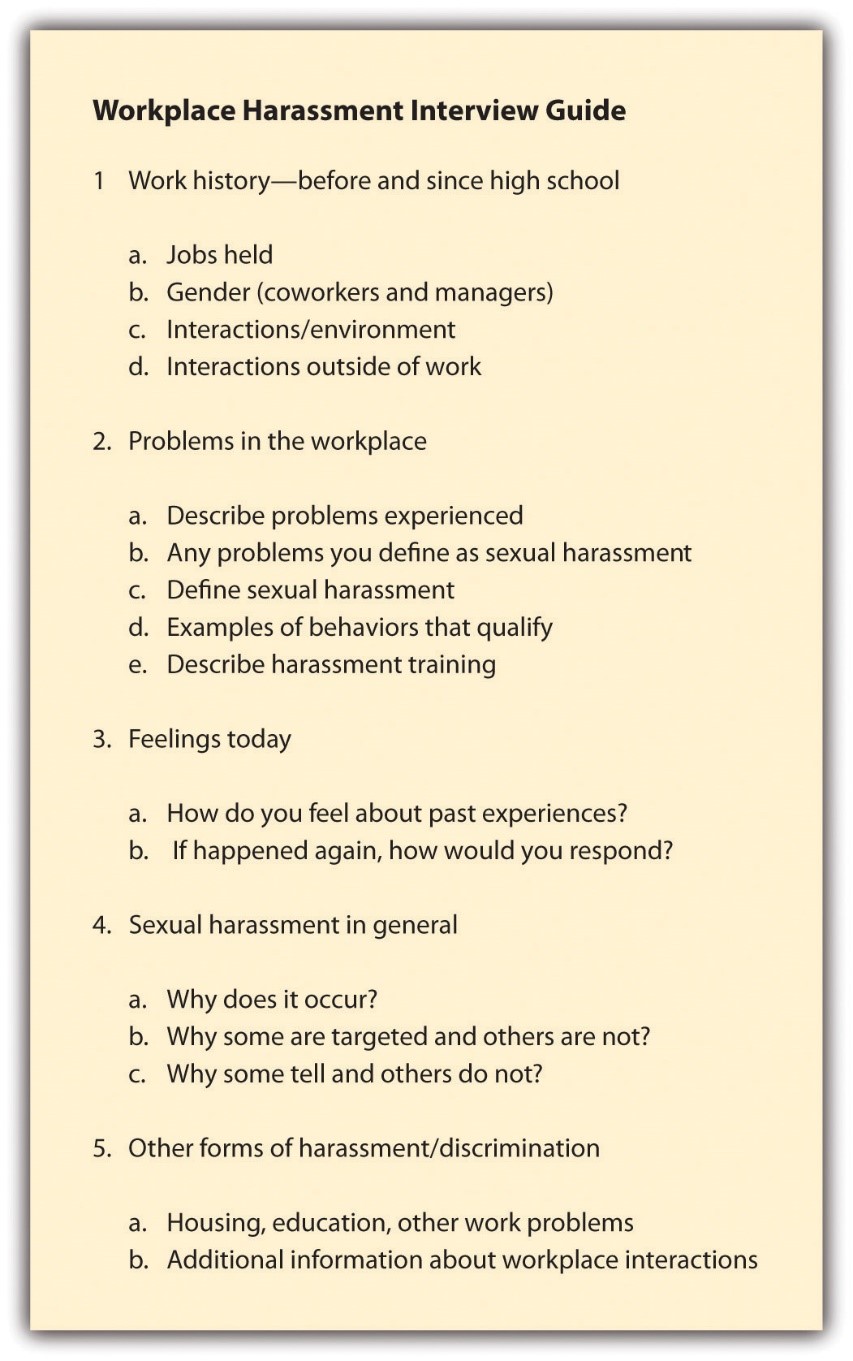

Earlier, I mentioned that interview guides can list topics or questions. The specific format of an interview guide might depend on your style, experience, and comfort level as an interviewer or with your topic. Figure 13.1 provides an example of an interview guide for a study of how young people experience workplace sexual harassment. The guide is topic-based, rather than a list of specific questions. The listed order of the topics is important, however the order that each comes up during the interview may vary.

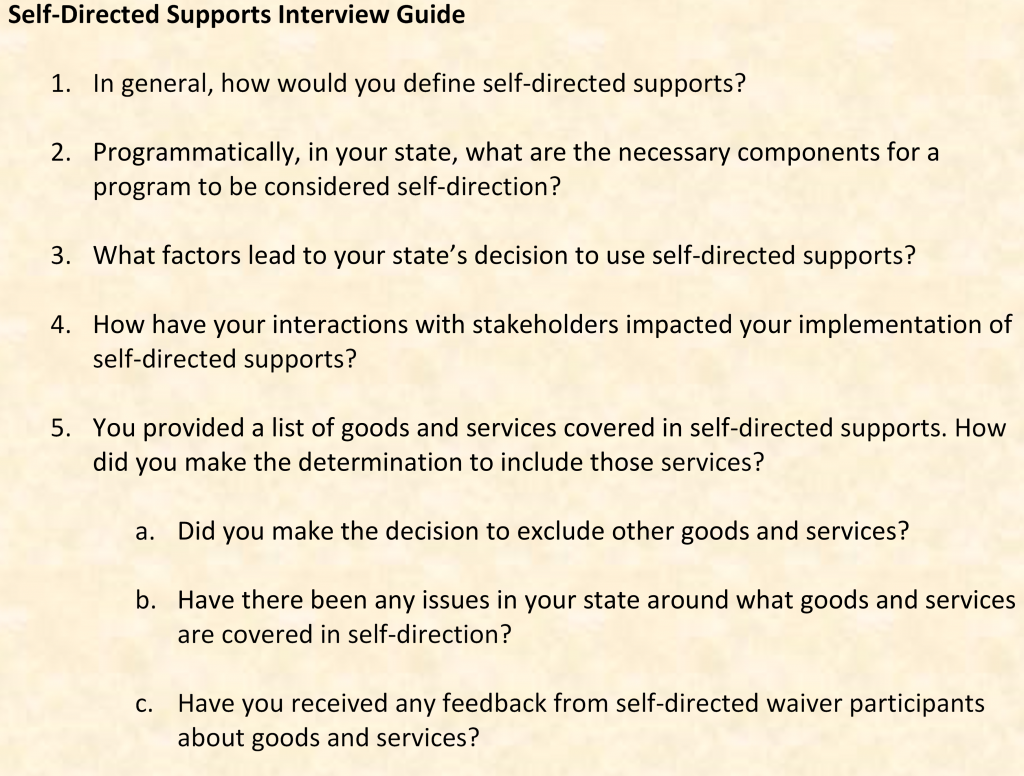

When I was interviewing state administrators of developmental disabilities departments, my interview guide contained 15 questions, all of which were asked to each participant. Sometimes, participants would cover the answer to one question before it was read. When I came to that question later on in the interview, I would acknowledge that they already addressed part of this question and ask them if they had anything to add to their response. Underneath some of the questions were more specific words or phrases for follow-up in case the participant did not mention those topics in their responses. These probes, as well as the questions, were based on our review of their department’s documentation about their programs. Our project was challenging because we were studying specific types of programs and the administrators may have thought we had an agenda to convince them to expand or better fund those programs. We had to be very objective in how we worded questions to avoid the appearance of bias. Some of these questions are depicted in Figure 13.2.

As you might have guessed, interview guides do not appear out of thin air. They are the result of thoughtful and careful work on the part of a researcher. As you can see in both of the preceding guides, the topics and questions have been organized thematically and in the order in which they are likely to proceed (though keep in mind that the flow of a qualitative interview is in part determined by what a respondent has to say). Sometimes qualitative interviewers may create two versions of the interview guide: one version contains a very brief outline of the interview, perhaps with just topic headings, and another version contains detailed questions underneath each topic heading. In this case, the researcher might use the detailed guide to prepare and practice before conducting interviews and then bring the brief outline to the interview. Bringing an outline to an interview encourages the researcher to actively listen to what a participant is telling them. An overly detailed interview guide will be difficult to navigate during an interview and could give respondents the misimpression the interviewer is more interested in their questions than in the participant’s answers.

Brainstorming is usually the first step in constructing an interview guide. There are no rules at the brainstorming stage—simply list all the topics and questions that come to mind when you think about your research question. Once you have a decent list, you can begin to cut questions and topics that seem redundant and group similar questions and topics together. If you haven’t done so yet, you may also want to come up with question and topic headings for your grouped categories. You should also consult the scholarly literature to find out what kinds of questions other interviewers have asked in studies of similar topics and what theory indicates might be important. As with quantitative survey research, avoid placing very sensitive or potentially controversial questions at the beginning of your qualitative interview guide. You need to give participants the opportunity to warm up to the interview and to feel comfortable talking with you. Finally, get some feedback on your interview guide. Ask your friends, other researchers, and your professors for some guidance and suggestions once you’ve come up with what you think is a strong guide. They may catch a few things that you hadn’t noticed. Once you begin conducting interviews, your participants may also suggest revisions or improvements.

There are a few noteworthy guidelines for the specific questions you should include in your guide. First, avoid questions that can be answered with a simple yes or no. Try to rephrase your questions in a way that invites longer responses from your interviewees. If you choose to include yes or no questions, be sure to include follow-up questions. Remember, one of the benefits of qualitative interviews is that you can ask participants for more information, so be sure to do so. While it is a good idea to ask follow-up questions, try to avoid asking “why,” as this can come off as unintentionally confrontational. Respondents often won’t know how to respond to this type of question, perhaps because they have not explored “why” themselves. Instead, I recommend using something like, “Could you tell me a little more about that?” This allows participants to explain themselves further without feeling that they’re being doubted or questioned in a hostile way.

Also, try to avoid phrasing your questions in a leading way. For example, rather than asking, “Don’t you think most people who don’t want kids are selfish?” you could ask, “What comes to mind for you when you hear someone doesn’t want kids?” Instead of asking “What do you think about juvenile offenders who drink and drive?” you could ask, “How do you feel about underage drinking?” or “What do you think about drinking and driving?” Finally, remember to keep most, if not all, of your questions open-ended. The key to a successful qualitative interview is giving participants the opportunity to share information in their own words and in their own way. Documenting your decisions regarding which questions are used, thrown out, or revised can help you remember the thought process behind the interview guide when you analyze your results. Additionally, documentation promotes the rigor of the qualitative project, ensuring the researcher is proceeding in a reflective and deliberate manner that can be checked by others reviewing their study.

Recording qualitative data

After the interview guide is constructed, the interviewer is not yet ready to begin conducting interviews. Next, the researcher must decide how to collect and maintain the information that is provided by participants. Researchers keep field notes or written recordings produced by the researcher during the data collection process, including before, during, and after interviews. Field notes help researchers to document their observations and they form the first draft of data analysis. Field notes may contain many things, including but not limited to observations of body language or environment, reflections on whether interview questions are working well, and connections between ideas that participants share.

Unfortunately, even the most diligent researcher cannot write down everything that is seen or heard during an interview. In particular, it is difficult for a researcher to be truly present and observant if they are also writing down everything the participant is saying. For this reason, it is quite common for interviewers to create audio recordings of the interviews they conduct. Recording interviews allows the researcher to focus on their interaction with the interview participant rather than being distracted by trying to write down every word that is said.

Of course, not all participants will feel comfortable being recorded and there may be situations in which the interviewer feels the subject is too sensitive to be recorded. In these cases, the researcher must balance excellent note-taking, exceptional question-asking, and even better listening. I don’t think I can understate the difficulty of managing all these feats simultaneously. It is crucial to practice the interview in advance whether you will be recording your interviews or not. Ideally, you’ll find a friend or two willing to participate in a couple of trial runs with you. Even better, you’ll find a friend or two who are similar in at least some ways to your sample. They can give you the best feedback on your questions and your interview demeanor.

Another issue interviewers face is documenting the decisions made during the data collection process. Qualitative research is open to new ideas that emerge through the data collection process. For example, a participant might suggest a new concept you hadn’t thought of before or define a concept in a new way. This may lead you to create new questions or ask questions in a different way to future participants. These processes should be documented in a process called journaling or memoing. Journal entries are notes to yourself about reflections or methodological decisions that emerge during the data collection process. Documenting these decisions is important, as you’d be surprised how quickly you can forget what happened. Journaling ensures that you remember, how, when, and why certain changes were made when it comes time to analyze your data. The discipline of journaling in qualitative research helps to ensure the rigor of the research process—that is its trustworthiness and authenticity. We covered these standards of qualitative rigor in Chapter 9.

Strengths and weaknesses of qualitative interviews

As we’ve mentioned in this section, qualitative interviews are an excellent way to gather detailed information. Researchers can explore topics in the most depth by using interviews compared to other methods. Qualitative interviewing allows participants the opportunity to elaborate in ways that are not possible with other methods like survey research. They are also able share information with researchers in their own words and from their own perspectives. Differently, quantitative research asks participants to fit their perspectives into the limited response options provided by the researcher. Qualitative interviews are designed to elicit detailed information, so they are especially useful when a researcher’s aim is to study social processes or the “how” of various phenomena. While it is often an overlooked benefit of qualitative interviewing, researchers can make observations beyond those that a respondent is orally reporting. A respondent’s body language, and even their choice of time and location for the interview, might provide a researcher with useful data.

Of course, all these benefits come with some drawbacks. As with quantitative survey research, qualitative interviews rely on respondents’ ability to accurately and honestly recall specific details about their lives, circumstances, thoughts, opinions, or behaviors. As Esterberg (2002) puts it, “If you want to know about what people actually do, rather than what they say they do, you should probably use observation [instead of interviews].” [2] Further, as you may have already guessed, qualitative interviewing is time-intensive and can be quite expensive. Creating an interview guide, identifying a sample, and conducting interviews are just the beginning. Writing out what was said in interviews and analyzing the qualitative data are time consuming processes. Keep in mind you are also asking for more of participants’ time than if you’d simply mailed them a questionnaire containing closed-ended questions. Conducting qualitative interviews is not only labor-intensive but can also be emotionally taxing. Seeing and hearing the impact that social problems have on respondents is difficult. Researchers embarking on a qualitative interview project should keep in mind their own abilities to receive stories that may be difficult to hear.

Key Takeaways

- In-depth interviews are semi-structured interviews where the researcher has topics and questions in mind to ask, but questions are open-ended and flow according to how the participant responds to each.

- Interview guides can vary in format but should contain some outline of the topics you hope to cover during the course of an interview.

- Qualitative interviews allow respondents to share information in their own words and are useful for gathering detailed information and understanding social processes.

- Field notes and journal entries document the researcher’s decisions and thoughts that influence the research process.

- Drawbacks of qualitative interviews include reliance on respondents’ accuracy and their intensity in terms of time, expense, and possible emotional strain.

Field notes- written notes produced by the researcher during the data collection process

In-depth interviews- interviews in which researchers hear from respondents about what they think is important about the topic at hand in the respondent’s own words

Interview guide- a list of topics or questions that the interviewer hopes to cover during the course of an interview

Journaling- making notes of emerging issues and changes during the research process

Semi-structured interviews- questions are open ended and may not be asked in exactly the same way or in exactly the same order to each and every respondent

Image attributions

questions by geralt CC-0

writing by StockSnap CC-0

- Figure 13.1 is copied from Blackstone, A. (2012) Principles of sociological inquiry: Qualitative and quantitative methods. Saylor Foundation. Retrieved from: https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_principles-of-sociological-inquiry-qualitative-and-quantitative-methods/ Shared under CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/) ↵

- Esterberg, K. G. (2002). Qualitative methods in social research . Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill. ↵

Scientific Inquiry in Social Work Copyright © 2018 by Matthew DeCarlo is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- University Libraries

- Research Guides

- Topic Guides

- Research Methods Guide

- Interview Research

Research Methods Guide: Interview Research

- Introduction

- Research Design & Method

- Survey Research

- Data Analysis

- Resources & Consultation

Tutorial Videos: Interview Method

Interview as a Method for Qualitative Research

Goals of Interview Research

- Preferences

- They help you explain, better understand, and explore research subjects' opinions, behavior, experiences, phenomenon, etc.

- Interview questions are usually open-ended questions so that in-depth information will be collected.

Mode of Data Collection

There are several types of interviews, including:

- Face-to-Face

- Online (e.g. Skype, Googlehangout, etc)

FAQ: Conducting Interview Research

What are the important steps involved in interviews?

- Think about who you will interview

- Think about what kind of information you want to obtain from interviews

- Think about why you want to pursue in-depth information around your research topic

- Introduce yourself and explain the aim of the interview

- Devise your questions so interviewees can help answer your research question

- Have a sequence to your questions / topics by grouping them in themes

- Make sure you can easily move back and forth between questions / topics

- Make sure your questions are clear and easy to understand

- Do not ask leading questions

- Do you want to bring a second interviewer with you?

- Do you want to bring a notetaker?

- Do you want to record interviews? If so, do you have time to transcribe interview recordings?

- Where will you interview people? Where is the setting with the least distraction?

- How long will each interview take?

- Do you need to address terms of confidentiality?

Do I have to choose either a survey or interviewing method?

No. In fact, many researchers use a mixed method - interviews can be useful as follow-up to certain respondents to surveys, e.g., to further investigate their responses.

Is training an interviewer important?

Yes, since the interviewer can control the quality of the result, training the interviewer becomes crucial. If more than one interviewers are involved in your study, it is important to have every interviewer understand the interviewing procedure and rehearse the interviewing process before beginning the formal study.

- << Previous: Survey Research

- Next: Data Analysis >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2023 10:42 AM

Using an interview in a research paper

Consultant contributor: Viviane Ugalde

Using an interview can be an effective primary source for some papers and research projects. Finding an expert in the field or some other person who has knowledge of your topic can allow for you to gather unique information not available elsewhere.

There are four steps to using an interview as a source for your research.

- Know where and how to start.

- Know how to write a good question.

- Know how to conduct an interview.

- Know how to incorporate the interview into your document or project.

Step one: Where to start

First, you should determine your goals and ask yourself these questions:

- Who are the local experts on topic?

- How can I contact these people?

- Does anyone know them to help me setup the interviews?

- Are their phone numbers in the phone book or can I find them on the Internet?

Once you answer these questions and pick your interviewee, get their basic information such as their name, title, and other general details. If you reach out and your interview does not participate, don’t be discouraged. Keep looking for other interview contacts.

Step two: How to write a good question

When you have confirmed an interview, it is not time to come up with questions.

- Learning as much as you can about the person before the interview can help you create questions specific to your interview subject.

- Doing research about your interviewee’s past experience in your topic, or any texts that they have written would be great background research.

When you start to think of questions, write down more questions than you think you’ll need, and prioritize them as you go. Any good questions will answer the 5W and H questions. Asking Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How questions that you need answered for your paper, will help you form a question to ask your interviewee.

When writing a good question, try thinking of something that will help your argument.

- Is your interviewee an advocate for you position?

- Are they in any programs that are related to your research?

- How much experience do they have?

From broad questions like these, you can begin to narrow down to more specific and open-ended questions.

Step three: The interview

If at all possible, arrange to conduct the interview at the subject’s workplace. It will make them more comfortable, and you can write about their surroundings.

- Begin the interview with some small talk in order to give both of you the chance to get comfortable with one another

- Develop rapport that will make the interview easier for both of you.

- Ask open-ended questions

- Keep the conversation moving

- Stay on topic

- The more silence in the room, the more honest the answer.

- If an interesting subject comes up that is related to your research, ask a follow-up or an additional question about it.

- Ask if you can stay in contact with your interview subject in case there are any additional questions you have.

Step four: Incorporating the interview

When picking the material out of your interview, remember that people rarely speak perfectly. There will be many slang words and pauses that you can take out, as long as it does not change the meaning of the material you are using.

As you introduce your interview in the paper, start with a transition such as “according to” or other attributions. You should also be specific to the type of interview you are working with. This way, you will build a stronger ethos in your paper .

The body of your essay should clearly set up the quote or paraphrase you use from the interview responses,. Be careful not to stick a quote from the interview into the body of your essay because it sounds good. When deciding what to quote in your paper, think about what dialogue from the interview would add the most color to your interview. Quotes that illustrate what your interviewer sounded like, or what their personality is are always the best quotes to choose from.

Once you have done that, proofread your essay. Make sure the quotes you used don’t make up the majority of your paper. The interview quotes are supposed to support your argument; you are not supposed to support the interview.

For example, let’s say that you are arguing that free education is better than not. For your argument, you interview a local politician who is on your side of the argument. Rather than using a large quote that explains the stance of both sides, and why the politician chose this side, your quote is there to support the information you’ve already given. Whatever the politician says should prove what you argue, and not give new information.

Step five: Examples of citing your interviews

Smith, Jane. Personal interview. 19 May 2018.

(E. Robbins, personal communication, January 4, 2018).

Smith also claimed that many of her students had difficulties with APA style (personal communication, November 3, 2018).

Reference list

Daly, C. & Leighton W. (2017). Interviewing a Source: Tips. Journalists Resource.

Driscoll, D. (2018 ). Interviewing. Purdue University

Hayden, K. (2012). How to Conduct an Interview to Write a Paper . Bright Hub Education, Bright Hub Inc.

Hose, C. (2017). How to Incorporate Interviews into Essays. Leaf Group Education.

Magnesi, J. (2017). How to Interview Someone for an Article or Research Paper. Career Trend, Leaf group Media.

Interviews for your thesis

All the information at a glance.

- Research method

View our services

Language check

Have your thesis or report reviewed for language, structure, coherence, and layout.

Plagiarism check

Check if your document contains plagiarism.

APA-generator

Create your reference list in APA style effortlessly. Completely free of charge.

Interviews for qualitative or quantitative research?

What type of interviews are there, recruiting respondents, interview step-by-step plan, asking good interview questions, how do you transcribe interviews, incorporating the interviews into your thesis, our best tips for interview techniques.

Are interviews necessary for your thesis? In that case, there are a few things to consider. You have to decide what kind of interview to conduct. You need to draw up good questions. You also have to choose an appropriate transcription method and incorporate the interview results into your thesis correctly. How do you do all of this properly? Here you will find everything you need to know about conducting and processing interviews for your thesis.

Interviews are an appropriate form of data collection in both quantitative and qualitative research.

Quantitative research is all about numbers and testing hypotheses.

In qualitative research, you primarily go into detail collecting opinions, experiences and ideas to fully understand a concept.

In qualitative research, you usually see open-ended questions because they lead to rich data. In quantitative research, closed questions are more common.

Roughly speaking, we can distinguish between a few types of interviews. The most common are the following interview forms:

Structured interviews: you follow a strict interview schedule with a fixed order of questions so that all interviews take place in the same way.

Semi-structured interviews: you prepare the questions, but can deviate on the spot from your preparation during the interview (e.g. if you want to ask further questions).

Unstructured interviews: in advance, you have only prepared a list with topics you want to ask about; the questions you want to ask are not yet known.

Focus group: you get a group of people together to talk to each other about a topic, and you are the one to ask the questions and facilitate the conversation.

Group interview: you interview several people at the same time about various topics, focusing more on the interaction between you and the interviewees than the participants engaging with each other.

To conduct interviews, you need to find people willing to be interviewed. Sometimes one or two interviews will suffice, for instance in a case study. There are also research methods that require a larger number of interviews. The number of interviews that is ideal depends on your research goal and research question.

The more interviews you conduct, the greater the reliability and validity of your results. Your research results are then more likely to reflect reality.

Discuss with your thesis supervisor in advance how many interviews would be ideal for your research. Keep the time schedule in mind. Of course, the number of interviews should be realistic within the time you have to recruit respondents and conduct interviews.

To conduct an interview, you go through several stages. Good preparation is very important. Our interview roadmap will help you do this properly. Follow these 6 steps:

Choose the type of interview.

Prepare the interview guide.

Practice your interview techniques.

Start the interview in the right way.

Conduct the interview.

Transcribe the conversation.

A good interview depends on the quality of the questions you ask. Take the time to draft good and clear questions. These tips for formulating interview questions will help you do just that.

For example, note the following:

Ask non-directive questions. Be objective in your questioning to avoid pressuring your interviewee into giving socially desirable answers.

Be as clear as possible with your questions. Keep them short, be specific, avoid jargon, and only ask one question at a time.

Ask the questions in a logical order. For example, this could be in chronological order if you ask people to describe an event. Another option is to start with questions about the problem and its causes and later ask questions about possible solutions.

Make a good trade-off between open and closed questions. With open questions, you get richer answers; with closed questions, the answers are more limited, but the answers are more comparable. Try to achieve a balance that suits your research question.

To analyse, code, and use the interview data in your thesis, you need to transcribe the interviews first.

We list the main points of interest in our article on transcribing interviews. Read here, for example, which transcription methods exist and which software you can use to make your life a lot easier. Are you willing to pay a small amount of money? Then, you may want to consider outsourcing your transcription.

If all goes well, interesting findings will emerge from the interviews. Processing the data from the interviews in your thesis is done as follows:

In the method chapter , describe how you conducted the interviews. For example, indicate the interview format, explain how you arrived at the questionnaire and describe the results of any pre-test you do.

In the results chapter , summarise the main findings from the interviews. Refer to the interview data using quotes or paraphrases. You may find the various models for your thesis, such as risk analysis or SWOT analysis, useful for your data analysis.

In the conclusion , answer your research question based on the interview data (and any other research methods or sources).

In the discussion , explain what you did to ensure the reliability and validity of your study. Also, mention the possible limitations of the chosen interview method here.

Put the interview transcripts in the appendices . You can also include the questionnaire or topic list you used in the appendix. Refer to this in the running text of your thesis.

Do you doubt whether you have placed the interview data in the right place and used the correct thesis structure? The editors of AthenaCheck will be happy to check your thesis for proper structure, a common thread and/or language and spelling. This way, you can be sure that your thesis is well put together in these areas.

The quality of your data largely depends on your qualities as an interviewer. We are happy to help you tackle the interview in the best possible way. Check out our tips for useful interview techniques, such as:

Listen more rather than speak more. Above all, let the interviewee speak.

Ask further questions if the interviewee says something interesting.

Above all, ask open-ended questions, as they provide richer data.

Formulate your questions neutrally so that you don't steer the interviewee too much towards a particular answer.

Be clear and specific with your questions.

Avoid jargon.

Keep an eye on non-verbal cues from the interviewee. These cues sometimes tell you more than a thousand words could. You can tell, for example, if someone does not understand something or if the interviewee is getting emotional.

- Dissertations

- Qualitative Research

- Quantitative Research

- Academic Writing

- Getting Published

News & Events

How to create an interview guide.

- March 6, 2017

- Posted by: Mike Rucker

- Category: Research

If your research involves gathering data by interviewing people, you will probably need to create an interview guide. An interview guide contains a list of questions you want to cover during your interview(s). It is meant to keep you on track and ensures that you cover all the topics needed to answer your research question(s).

Interview guides are very common in semi-structured interviews. They need to be designed in a way that gives your interviewees enough space to tell their stories and provide you with meaningful data. Therefore, you should include open-ended questions that allow for your conversation to flow freely. Free flowing conversation can help you uncover topics you were not aware of previously (without wandering off your subject matter). An interview guide acts as an unobtrusive road map you can turn to during the interview to yourself back on course. A good interview guide provides you with prompts and a general direction.

As your research progresses, you can update your interview guide to include new questions. Often, an initial interview guide can be used for the first few interviews, after which a few tweaks can be made to allow you (the researcher) to dive deeper into the topic by using a revised guide. A revised guide should not be perceived as a stumbling block. On the contrary, creating a revised interview guide can be a sign of a good research process — it shows you are letting the research material guide you (and not vice versa).

Here are some useful strategies when you create an interview guide:

- Think about the research question of your study and identify which areas need to explored to answer your question. Your interview questions are not the same as your research question, but should help answer it. (If you have troubles developing your research question, you can read this post .)

- Consider how much time you can spend with each interviewee and adjust the number of questions accordingly. Be realistic about how much can be covered in 60 to 90 minutes (the usual length of an interview). Field test your guide on test/volunteer subjects to make sure your timing assumptions are accurate before actually collecting data.

- Avoid asking questions that can be answered in a few words (also known as closed-ended questions). The point of a qualitative interview is to collect a rich amount of data. You need to encourage your participants to open up and talk at length, sharing their personal expertise with you.

- Make your questions easy to understand. Ask only one question at a time (e.g. avoid compound questions).

- Think about the language you use so that it fits that particular respondent (for instance, professional versus informal language).

- Allow enough time for interviewees to be able to elaborate on certain answers and give you examples. Develop probes that can be used to elicit more detail (when needed).

- Usually, “how” questions are the preferred option, as these type of questions give an opportunity for a longer response. For example, “Can you tell me how you started working with the American Cancer Society?”

Structure of an Interview Guide

In qualitative research, a lot can depend on the ability of the researcher to enter the field and build rapport with their respondents. When people feel at ease with you, they are more likely to share information honestly and freely. The idea is to build trust and rapport as quickly as possible. Therefore, it can be helpful if you structure your interview so it is set up to build trust quickly. For example, it is usually a good idea to begin the conversation with a warm-up question. Start by asking a simple question that your participants can easily answer and that helps them feel more relaxed. This first question doesn’t necessarily need to be related to your overall topic.

Create an interview guide so the structure of your interview follows a logical order and flows naturally. Don’t jump from one topic to another. Also, if you feel that enough time has been spent answering a certain question, you can use gentle probes to change the subject (e.g. “Let’s move on to another topic now.”).

Save the most difficult questions for the end of the interview. It is more likely people will be willing to share their private experience after they have had some time to become more comfortable with you.

Finish with a question that can provide some closure to the interview. It is important that at the end of your interview, your respondent(s) feel positive and pleased they have participated in your research.

Our systems are now restored following recent technical disruption, and we’re working hard to catch up on publishing. We apologise for the inconvenience caused. Find out more: https://www.cambridge.org/universitypress/about-us/news-and-blogs/cambridge-university-press-publishing-update-following-technical-disruption

We use cookies to distinguish you from other users and to provide you with a better experience on our websites. Close this message to accept cookies or find out how to manage your cookie settings .

Login Alert

- > Doing Interview-based Qualitative Research

- > Designing the interview guide

Book contents

- Frontmatter

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Some examples of interpretative research

- 3 Planning and beginning an interpretative research project

- 4 Making decisions about participants

- 5 Designing the interview guide

- 6 Doing the interview

- 7 Preparing for analysis

- 8 Finding meanings in people's talk

- 9 Analyzing stories in interviews

- 10 Analyzing talk-as-action

- 11 Analyzing for implicit cultural meanings

- 12 Reporting your project

5 - Designing the interview guide

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2015

This chapter shows you how to prepare a comprehensive interview guide. You need to prepare such a guide before you start interviewing. The interview guide serves many purposes. Most important, it is a memory aid to ensure that the interviewer covers every topic and obtains the necessary detail about the topic. For this reason, the interview guide should contain all the interview items in the order that you have decided. The exact wording of the items should be given, although the interviewer may sometimes depart from this wording. Interviews often contain some questions that are sensitive or potentially offensive. For such questions, it is vital to work out the best wording of the question ahead of time and to have it available in the interview.

To study people's meaning-making, researchers must create a situation that enables people to tell about their experiences and that also foregrounds each person's particular way of making sense of those experiences. Put another way, the interview situation must encourage participants to tell about their experiences in their own words and in their own way without being constrained by categories or classifications imposed by the interviewer. The type of interview that you will learn about here has a conversational and relaxed tone. However, the interview is far from extemporaneous. The interviewer works from the interview guide that has been carefully prepared ahead of time. It contains a detailed and specific list of items that concern topics that will shed light on the researchable questions.

Often researchers are in a hurry to get into the field and gather their material. It may seem obvious to them what questions to ask participants. Seasoned interviewers may feel ready to approach interviewing with nothing but a laundry list of topics. But it is always wise to move slowly at this point. Time spent designing and refining interview items – polishing the wording of the items, weighing language choices, considering the best sequence of topics, and then pretesting and revising the interview guide – will always pay off in producing better interviews. Moreover, it will also provide you with a deep knowledge of the elements of the interview and a clear idea of the intent behind each of the items. This can help you to keep the interviews on track.

Access options

Save book to kindle.

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle .

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service .

- Designing the interview guide

- Eva Magnusson , Umeå Universitet, Sweden , Jeanne Marecek , Swarthmore College, Pennsylvania

- Book: Doing Interview-based Qualitative Research

- Online publication: 05 October 2015

- Chapter DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107449893.005

Save book to Dropbox

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox .

Save book to Google Drive

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive .

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

Semi-Structured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples

Published on January 27, 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

A semi-structured interview is a data collection method that relies on asking questions within a predetermined thematic framework. However, the questions are not set in order or in phrasing.

In research, semi-structured interviews are often qualitative in nature. They are generally used as an exploratory tool in marketing, social science, survey methodology, and other research fields.

They are also common in field research with many interviewers, giving everyone the same theoretical framework, but allowing them to investigate different facets of the research question .

- Structured interviews : The questions are predetermined in both topic and order.

- Unstructured interviews : None of the questions are predetermined.

- Focus group interviews : The questions are presented to a group instead of one individual.

Table of contents

What is a semi-structured interview, when to use a semi-structured interview, advantages of semi-structured interviews, disadvantages of semi-structured interviews, semi-structured interview questions, how to conduct a semi-structured interview, how to analyze a semi-structured interview, presenting your results (with example), other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about semi-structured interviews.

Semi-structured interviews are a blend of structured and unstructured types of interviews.

- Unlike in an unstructured interview, the interviewer has an idea of what questions they will ask.

- Unlike in a structured interview, the phrasing and order of the questions is not set.

Semi-structured interviews are often open-ended, allowing for flexibility. Asking set questions in a set order allows for easy comparison between respondents, but it can be limiting. Having less structure can help you see patterns, while still allowing for comparisons between respondents.

Semi-structured interviews are best used when:

- You have prior interview experience. Spontaneous questions are deceptively challenging, and it’s easy to accidentally ask a leading question or make a participant uneasy.

- Your research question is exploratory in nature. Participant answers can guide future research questions and help you develop a more robust knowledge base for future research.

Just like in structured interviews, it is critical that you remain organized and develop a system for keeping track of participant responses. However, since the questions are less set than in a structured interview, the data collection and analysis become a bit more complex.

Differences between different types of interviews

Make sure to choose the type of interview that suits your research best. This table shows the most important differences between the four types.

| Fixed questions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed order of questions | ||||

| Fixed number of questions | ||||

| Option to ask additional questions |

Semi-structured interviews come with many advantages.

Best of both worlds

No distractions, detail and richness.

However, semi-structured interviews also have their downsides.

Low validity

High risk of research bias, difficult to develop good semi-structured interview questions.

Since they are often open-ended in style, it can be challenging to write semi-structured interview questions that get you the information you’re looking for without biasing your responses. Here are a few tips:

- Define what areas or topics you will be focusing on prior to the interview. This will help you write a framework of questions that zero in on the information you seek.

- Write yourself a guide to refer to during the interview, so you stay focused. It can help to start with the simpler questions first, moving into the more complex ones after you have established a comfortable rapport.

- Be as clear and concise as possible, avoiding jargon and compound sentences.

- How often per week do you go to the gym? a) 1 time; b) 2 times; c) 3 times; d) 4 or more times

- If yes: What feelings does going to the gym bring out in you?

- If no: What do you prefer to do instead?

- If yes: How did this membership affect your job performance? Did you stay longer in the role than you would have if there were no membership?

Once you’ve determined that a semi-structured interview is the right fit for your research topic , you can proceed with the following steps.

Step 1: Set your goals and objectives

You can use guiding questions as you conceptualize your research question, such as:

- What are you trying to learn or achieve from a semi-structured interview?

- Why are you choosing a semi-structured interview as opposed to a different type of interview, or another research method?

If you want to proceed with a semi-structured interview, you can start designing your questions.

Step 2: Design your questions

Try to stay simple and concise, and phrase your questions clearly. If your topic is sensitive or could cause an emotional response, be mindful of your word choices.

One of the most challenging parts of a semi-structured interview is knowing when to ask follow-up or spontaneous related questions. For this reason, having a guide to refer back to is critical. Hypothesizing what other questions could arise from your participants’ answers may also be helpful.

Step 3: Assemble your participants

There are a few sampling methods you can use to recruit your interview participants, such as:

- Voluntary response sampling : For example, sending an email to a campus mailing list and sourcing participants from responses.

- Stratified sampling of a particular characteristic trait of interest to your research, such as age, race, ethnicity, or gender identity.

Step 4: Decide on your medium

It’s important to determine ahead of time how you will be conducting your interview. You should decide whether you’ll be conducting it live or with a pen-and-paper format. If conducted in real time, you also need to decide if in person, over the phone, or via videoconferencing is the best option for you.

Note that each of these methods has its own advantages and disadvantages:

- Pen-and-paper may be easier for you to organize and analyze, but you will receive more prepared answers, which may affect the reliability of your data.

- In-person interviews can lead to nervousness or interviewer effects, where the respondent feels pressured to respond in a manner they believe will please you or incentivize you to like them.

Step 5: Conduct your interviews

As you conduct your interviews, keep environmental conditions as constant as you can to avoid bias. Pay attention to your body language (e.g., nodding, raising eyebrows), and moderate your tone of voice.

Relatedly, one of the biggest challenges with semi-structured interviews is ensuring that your questions remain unbiased. This can be especially challenging with any spontaneous questions or unscripted follow-ups that you ask your participants.

After you’re finished conducting your interviews, it’s time to analyze your results. First, assign each of your participants a number or pseudonym for organizational purposes.

The next step in your analysis is to transcribe the audio or video recordings. You can then conduct a content or thematic analysis to determine your categories, looking for patterns of responses that stand out to you and test your hypotheses .

Transcribing interviews

Before you get started with transcription, decide whether to conduct verbatim transcription or intelligent verbatim transcription.

- If pauses, laughter, or filler words like “umm” or “like” affect your analysis and research conclusions, conduct verbatim transcription and include them.

- If not, you can conduct intelligent verbatim transcription, which excludes fillers, fixes any grammatical issues, and is usually easier to analyze.

Transcribing presents a great opportunity for you to cleanse your data . Here, you can identify and address any inconsistencies or questions that come up as you listen.

Your supervisor might ask you to add the transcriptions to the appendix of your paper.

Coding semi-structured interviews

Next, it’s time to conduct your thematic or content analysis . This often involves “coding” words, patterns, or recurring responses, separating them into labels or categories for more robust analysis.

Due to the open-ended nature of many semi-structured interviews, you will most likely be conducting thematic analysis, rather than content analysis.

- You closely examine your data to identify common topics, ideas, or patterns. This can help you draw preliminary conclusions about your participants’ views, knowledge or experiences.

- After you have been through your responses a few times, you can collect the data into groups identified by their “code.” These codes give you a condensed overview of the main points and patterns identified by your data.

- Next, it’s time to organize these codes into themes. Themes are generally broader than codes, and you’ll often combine a few codes under one theme. After identifying your themes, make sure that these themes appropriately represent patterns in responses.

Analyzing semi-structured interviews

Once you’re confident in your themes, you can take either an inductive or a deductive approach.

- An inductive approach is more open-ended, allowing your data to determine your themes.

- A deductive approach is the opposite. It involves investigating whether your data confirm preconceived themes or ideas.

After your data analysis, the next step is to report your findings in a research paper .

- Your methodology section describes how you collected the data (in this case, describing your semi-structured interview process) and explains how you justify or conceptualize your analysis.

- Your discussion and results sections usually address each of your coded categories.

- You can then conclude with the main takeaways and avenues for further research.

Example of interview methodology for a research paper

Let’s say you are interested in vegan students on your campus. You have noticed that the number of vegan students seems to have increased since your first year, and you are curious what caused this shift.

You identify a few potential options based on literature:

- Perceptions about personal health or the perceived “healthiness” of a vegan diet

- Concerns about animal welfare and the meat industry

- Increased climate awareness, especially in regards to animal products

- Availability of more vegan options, making the lifestyle change easier

Anecdotally, you hypothesize that students are more aware of the impact of animal products on the ongoing climate crisis, and this has influenced many to go vegan. However, you cannot rule out the possibility of the other options, such as the new vegan bar in the dining hall.

Since your topic is exploratory in nature and you have a lot of experience conducting interviews in your work-study role as a research assistant, you decide to conduct semi-structured interviews.

You have a friend who is a member of a campus club for vegans and vegetarians, so you send a message to the club to ask for volunteers. You also spend some time at the campus dining hall, approaching students at the vegan bar asking if they’d like to participate.

Here are some questions you could ask:

- Do you find vegan options on campus to be: excellent; good; fair; average; poor?

- How long have you been a vegan?

- Follow-up questions can probe the strength of this decision (i.e., was it overwhelmingly one reason, or more of a mix?)

Depending on your participants’ answers to these questions, ask follow-ups as needed for clarification, further information, or elaboration.

- Do you think consuming animal products contributes to climate change? → The phrasing implies that you, the interviewer, do think so. This could bias your respondents, incentivizing them to answer affirmatively as well.

- What do you think is the biggest effect of animal product consumption? → This phrasing ensures the participant is giving their own opinion, and may even yield some surprising responses that enrich your analysis.

After conducting your interviews and transcribing your data, you can then conduct thematic analysis, coding responses into different categories. Since you began your research with several theories about campus veganism that you found equally compelling, you would use the inductive approach.

Once you’ve identified themes and patterns from your data, you can draw inferences and conclusions. Your results section usually addresses each theme or pattern you found, describing each in turn, as well as how often you came across them in your analysis. Feel free to include lots of (properly anonymized) examples from the data as evidence, too.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Student’s t -distribution

- Normal distribution

- Null and Alternative Hypotheses

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Data cleansing

- Reproducibility vs Replicability

- Peer review

- Prospective cohort study

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Placebo effect

- Hawthorne effect

- Hindsight bias

- Affect heuristic

- Social desirability bias

A semi-structured interview is a blend of structured and unstructured types of interviews. Semi-structured interviews are best used when:

- You have prior interview experience. Spontaneous questions are deceptively challenging, and it’s easy to accidentally ask a leading question or make a participant uncomfortable.

The four most common types of interviews are:

- Structured interviews : The questions are predetermined in both topic and order.

- Semi-structured interviews : A few questions are predetermined, but other questions aren’t planned.

Social desirability bias is the tendency for interview participants to give responses that will be viewed favorably by the interviewer or other participants. It occurs in all types of interviews and surveys , but is most common in semi-structured interviews , unstructured interviews , and focus groups .

Social desirability bias can be mitigated by ensuring participants feel at ease and comfortable sharing their views. Make sure to pay attention to your own body language and any physical or verbal cues, such as nodding or widening your eyes.

This type of bias can also occur in observations if the participants know they’re being observed. They might alter their behavior accordingly.

The interviewer effect is a type of bias that emerges when a characteristic of an interviewer (race, age, gender identity, etc.) influences the responses given by the interviewee.

There is a risk of an interviewer effect in all types of interviews , but it can be mitigated by writing really high-quality interview questions.

Inductive reasoning is a bottom-up approach, while deductive reasoning is top-down.

Inductive reasoning takes you from the specific to the general, while in deductive reasoning, you make inferences by going from general premises to specific conclusions.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). Semi-Structured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved September 14, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/semi-structured-interview/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, structured interview | definition, guide & examples, unstructured interview | definition, guide & examples, what is a focus group | step-by-step guide & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Piloting for Interviews in Qualitative Research: Operationalization and Lessons Learnt

- International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 7(4):1073-1080

- 7(4):1073-1080

- Universiti Teknologi MARA

- Universiti Putra Malaysia

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Tippawan Lertatthakornkit

- Erwin Erwin

- Farida Ariani

- Anna Kawakami

- Daricia Wilkinson

- Alexandra Chouldechova

- M. Sachchithananthan

- Menaha Thayaparan

- Abhinaya S. B

- Connor Osin

- Anthony Crozier

- Helen Jones

- Molly Glickman

- Maryam Dikko

- Murat Özpehlivan

- Vanora Hundley

- Milagros Castillo-Montoya

- Kim Kostere

- Sandra Kostere

- John W. Creswell

- Vicki L. Plano Clark

- M L Gutmann

- Frank M. Andrews

- Stephen B. Withey

- James C. Taylor

- David G. Bowers

- Vanora Hundley BN MSc RGN RM

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

2. Not having good interview technique. While you're generally not expected to become you to be an expert interviewer for a dissertation or thesis, it is important to practice good interview technique and develop basic interviewing skills.. Let's go through some basics that will help the process along.

3. People's espoused theories differ from their theories-in-practice. Get them to tell a story. Ask "how" questions not "do". Use "tell me about" and "tell me more about that". Use open-ended questions. Approach your topic sideways. Don't take the first answer as a final answer. Ask for elaboration.

Depending on the type of interview you are conducting, your questions will differ in style, phrasing, and intention. Structured interview questions are set and precise, while the other types of interviews allow for more open-endedness and flexibility. Here are some examples. Structured. Semi-structured.

To present interviews in a dissertation, you first need to transcribe your interviews. You can use transcription software for this. You can then add the written interviews to the appendix. If you have many or long interviews that make the appendix extremely long, the appendix (after consultation with the supervisor) can be submitted as a ...

How to Conduct an Effective Interview; A Guide. to Interview Design in Research Study. Authors. Hamed Taherdoost. University Canada West. [email protected]. Vancouver, Canada. Abstract ...

The specific format of an interview guide might depend on your style, experience, and comfort level as an interviewer or with your topic. Figure 13.1 provides an example of an interview guide for a study of how young people experience workplace sexual harassment. The guide is topic-based, rather than a list of specific questions.

Structured Interview | Definition, Guide & Examples. Published on January 27, 2022 by Tegan George and Julia Merkus. Revised on June 22, 2023. A structured interview is a data collection method that relies on asking questions in a set order to collect data on a topic. It is one of four types of interviews.. In research, structured interviews are often quantitative in nature.

TIPSHEET QUALITATIVE INTERVIEWINGTIP. HEET - QUALITATIVE INTERVIEWINGQualitative interviewing provides a method for collecting rich and detailed information about how individuals experience, understand. nd explain events in their lives. This tipsheet offers an introduction to the topic and some advice on. arrying out eff.

Develop an interview guide. Introduce yourself and explain the aim of the interview. Devise your questions so interviewees can help answer your research question. Have a sequence to your questions / topics by grouping them in themes. Make sure you can easily move back and forth between questions / topics. Make sure your questions are clear and ...

Career Trend, Leaf group Media. University Writing & Speaking Center. 1664 N. Virginia Street, Reno, NV 89557. William N. Pennington Student Achievement Center, Mailstop: 0213. [email protected]. (775) 784-6030. Using an interview can be an effective primary source for some papers and research projects.

To conduct an interview, you go through several stages. Good preparation is very important. Our interview roadmap will help you do this properly. Follow these 6 steps: Choose the type of interview. Prepare the interview guide. Practice your interview techniques. Start the interview in the right way.

If your research involves gathering data by interviewing people, you will probably need to create an interview guide. An interview guide contains a list of questions you want to cover during your interview(s). It is meant to keep you on track and ensures that you cover all the topics needed to answer your research question(s). Interview guides ...

The interview guide serves many purposes. Most important, it is a memory aid to ensure that the interviewer covers every topic and obtains the necessary detail about the topic. For this reason, the interview guide should contain all the interview items in the order that you have decided. The exact wording of the items should be given, although ...

Teleconference no.: +33 75 34 29 417. [email protected] or [email protected] yo. This information sheet is for you to keep. Appendix 3: Participant consent form. ea. cher: Linda Nyanchoka Please initial box1. I confirm that I have re. ve understood the info. mation sheetdated[] for the above study.

Abstract. The interview is an important data gathering technique involving verbal communication between the researcher and the subject. Interviews are commonly used in survey designs and in ...