Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 4: Theoretical frameworks for qualitative research

Tess Tsindos

Learning outcomes

Upon completion of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe qualitative frameworks.

- Explain why frameworks are used in qualitative research.

- Identify various frameworks used in qualitative research.

What is a Framework?

A framework is a set of broad concepts or principles used to guide research. As described by Varpio and colleagues 1 , a framework is a logically developed and connected set of concepts and premises – developed from one or more theories – that a researcher uses as a scaffold for their study. The researcher must define any concepts and theories that will provide the grounding for the research and link them through logical connections, and must relate these concepts to the study that is being carried out. In using a particular theory to guide their study, the researcher needs to ensure that the theoretical framework is reflected in the work in which they are engaged.

It is important to acknowledge that the terms ‘theories’ ( see Chapter 3 ), ‘frameworks’ and ‘paradigms’ are sometimes used interchangeably. However, there are differences between these concepts. To complicate matters further, theoretical frameworks and conceptual frameworks are also used. In addition, quantitative and qualitative researchers usually start from different standpoints in terms of theories and frameworks.

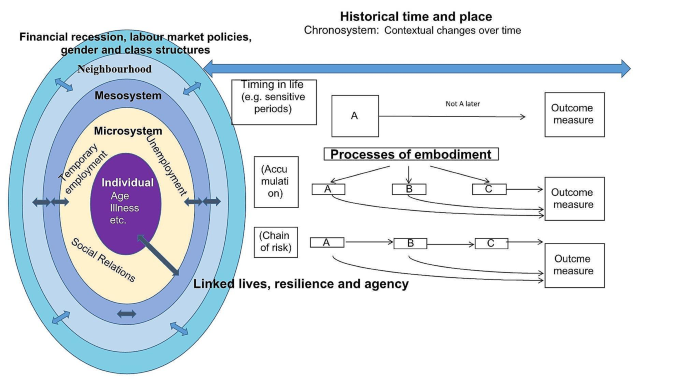

A diagram by Varpio and colleagues demonstrates the similarities and differences between theories and frameworks, and how they influence research approaches. 1(p991) The diagram displays the objectivist or deductive approach to research on the left-hand side. Note how the conceptual framework is first finalised before any research is commenced, and it involves the articulation of hypotheses that are to be tested using the data collected. This is often referred to as a top-down approach and/or a general (theory or framework) to a specific (data) approach.

The diagram displays the subjectivist or inductive approach to research on the right-hand side. Note how data is collected first, and through data analysis, a tentative framework is proposed. The framework is then firmed up as new insights are gained from the data analysis. This is referred to as a specific (data) to general (theory and framework) approach .

Why d o w e u se f rameworks?

A framework helps guide the questions used to elicit your data collection. A framework is not prescriptive, but it needs to be suitable for the research question(s), setting and participants. Therefore, the researcher might use different frameworks to guide different research studies.

A framework informs the study’s recruitment and sampling, and informs, guides or structures how data is collected and analysed. For example, a framework concerned with health systems will assist the researcher to analyse the data in a certain way, while a framework concerned with psychological development will have very different ways of approaching the analysis of data. This is due to the differences underpinning the concepts and premises concerned with investigating health systems, compared to the study of psychological development. The framework adopted also guides emerging interpretations of the data and helps in comparing and contrasting data across participants, cases and studies.

Some examples of foundational frameworks used to guide qualitative research in health services and public health:

- The Behaviour Change Wheel 2

- Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) 3

- Theoretical framework of acceptability 4

- Normalization Process Theory 5

- Candidacy Framework 6

- Aboriginal social determinants of health 7(p8)

- Social determinants of health 8

- Social model of health 9,10

- Systems theory 11

- Biopsychosocial model 12

- Discipline-specific models

- Disease-specific frameworks

E xamples of f rameworks

In Table 4.1, citations of published papers are included to demonstrate how the particular framework helps to ‘frame’ the research question and the interpretation of results.

Table 4.1. Frameworks and references

As discussed in Chapter 3, qualitative research is not an absolute science. While not all research may need a framework or theory (particularly descriptive studies, outlined in Chapter 5), the use of a framework or theory can help to position the research questions, research processes and conclusions and implications within the relevant research paradigm. Theories and frameworks also help to bring to focus areas of the research problem that may not have been considered.

- Varpio L, Paradis E, Uijtdehaage S, Young M. The distinctions between theory, theoretical framework, and conceptual framework. Acad Med . 2020;95(7):989-994. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003075

- Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci . 2011;6:42. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

- CFIR Research Team. Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). Center for Clinical Management Research. 2023. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://cfirguide.org/

- Sekhon M, Cartwright M, Francis JJ. Acceptability of healthcare interventions: an overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Serv Res . 2017;17:88. doi:10.1186/s12913-017-2031-8

- Murray E, Treweek S, Pope C, et al. Normalisation process theory: a framework for developing, evaluating and implementing complex interventions. BMC Med . 2010;8:63. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-8-63

- Tookey S, Renzi C, Waller J, von Wagner C, Whitaker KL. Using the candidacy framework to understand how doctor-patient interactions influence perceived eligibility to seek help for cancer alarm symptoms: a qualitative interview study. BMC Health Serv Res . 2018;18(1):937. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3730-5

- Lyon P. Aboriginal Health in Aboriginal Hands: Community-Controlled Comprehensive Primary Health Care @ Central Australian Aboriginal Congress; 2016. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://nacchocommunique.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/cphc-congress-final-report.pdf

- Solar O., Irwin A. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health: Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice); 2010. Accessed February 22, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241500852

- Yuill C, Crinson I, Duncan E. Key Concepts in Health Studies . SAGE Publications; 2010.

- Germov J. Imagining health problems as social issues. In: Germov J, ed. Second Opinion: An Introduction to Health Sociology . Oxford University Press; 2014.

- Laszlo A, Krippner S. Systems theories: their origins, foundations, and development. In: Jordan JS, ed. Advances in Psychology . Science Direct; 1998:47-74.

- Engel GL. From biomedical to biopsychosocial: being scientific in the human domain. Psychosomatics . 1997;38(6):521-528. doi:10.1016/S0033-3182(97)71396-3

- Schmidtke KA, Drinkwater KG. A cross-sectional survey assessing the influence of theoretically informed behavioural factors on hand hygiene across seven countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health . 2021;21:1432. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11491-4

- Graham-Wisener L, Nelson A, Byrne A, et al. Understanding public attitudes to death talk and advance care planning in Northern Ireland using health behaviour change theory: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health . 2022;22:906. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13319-1

- Walker R, Quong S, Olivier P, Wu L, Xie J, Boyle J. Empowerment for behaviour change through social connections: a qualitative exploration of women’s preferences in preconception health promotion in the state of Victoria, Australia. BMC Public Health . 2022;22:1642. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-14028-5

- Ayton DR, Barker AL, Morello RT, et al. Barriers and enablers to the implementation of the 6-PACK falls prevention program: a pre-implementation study in hospitals participating in a cluster randomised controlled trial. PLOS ONE . 2017;12(2):e0171932. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0171932

- Pratt R, Xiong S, Kmiecik A, et al. The implementation of a smoking cessation and alcohol abstinence intervention for people experiencing homelessness. BMC Public Health . 2022;22:1260. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13563-5

- Bossert J, Mahler C, Boltenhagen U, et al. Protocol for the process evaluation of a counselling intervention designed to educate cancer patients on complementary and integrative health care and promote interprofessional collaboration in this area (the CCC-Integrativ study). PLOS ONE . 2022;17(5):e0268091. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0268091

- Lwin KS, Bhandari AKC, Nguyen PT, et al. Factors influencing implementation of health-promoting interventions at workplaces: protocol for a scoping review. PLOS ONE . 2022;17(10):e0275887. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0275887

- Wilhelm AK, Schwedhelm M, Bigelow M, et al. Evaluation of a school-based participatory intervention to improve school environments using the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research. BMC Public Health . 2021;21:1615. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11644-5

- Timm L, Annerstedt KS, Ahlgren JÁ, et al. Application of the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability to assess a telephone-facilitated health coaching intervention for the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes. PLOS ONE . 2022;17(10):e0275576. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0275576

- Laing L, Salema N-E, Jeffries M, et al. Understanding factors that could influence patient acceptability of the use of the PINCER intervention in primary care: a qualitative exploration using the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability. PLOS ONE . 2022;17(10):e0275633. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0275633

- Renko E, Knittle K, Palsola M, Lintunen T, Hankonen N. Acceptability, reach and implementation of a training to enhance teachers’ skills in physical activity promotion. BMC Public Health . 2020;20:1568. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09653-x

- Alexander SM, Agaba A, Campbell JI, et al. A qualitative study of the acceptability of remote electronic bednet use monitoring in Uganda. BMC Public Health . 2022;22:1010. doi:10.1186/s12889-022-13393

- May C, Rapley T, Mair FS, et al. Normalization Process Theory On-line Users’ Manual, Toolkit and NoMAD instrument. 2015. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://normalization-process-theory.northumbria.ac.uk/

- Davis S. Ready for prime time? Using Normalization Process Theory to evaluate implementation success of personal health records designed for decision making. Front Digit Health . 2020;2:575951. doi:10.3389/fdgth.2020.575951

- Durand M-A, Lamouroux A, Redmond NM, et al. Impact of a health literacy intervention combining general practitioner training and a consumer facing intervention to improve colorectal cancer screening in underserved areas: protocol for a multicentric cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health . 2021;21:1684. doi:10.1186/s12889-021-11565

- Jones SE, Hamilton S, Bell R, Araújo-Soares V, White M. Acceptability of a cessation intervention for pregnant smokers: a qualitative study guided by Normalization Process Theory. BMC Public Health . 2020;20:1512. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09608-2

- Ziegler E, Valaitis R, Yost J, Carter N, Risdon C. “Primary care is primary care”: use of Normalization Process Theory to explore the implementation of primary care services for transgender individuals in Ontario. PLOS ONE . 2019;14(4):e0215873. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0215873

- Mackenzie M, Conway E, Hastings A, Munro M, O’Donnell C. Is ‘candidacy’ a useful concept for understanding journeys through public services? A critical interpretive literature synthesis. Soc Policy Adm . 2013;47(7):806-825. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9515.2012.00864.x

- Adeagbo O, Herbst C, Blandford A, et al. Exploring people’s candidacy for mobile health–supported HIV testing and care services in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: qualitative study. J Med Internet Res . 2019;21(11):e15681. doi:10.2196/15681

- Mackenzie M, Turner F, Platt S, et al. What is the ‘problem’ that outreach work seeks to address and how might it be tackled? Seeking theory in a primary health prevention programme. BMC Health Serv Res . 2011;11:350. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-350

- Liberati E, Richards N, Parker J, et al. Qualitative study of candidacy and access to secondary mental health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Soc Sci Med. 2022;296:114711. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114711

- Pearson O, Schwartzkopff K, Dawson A, et al. Aboriginal community controlled health organisations address health equity through action on the social determinants of health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia. BMC Public Health . 2020;20:1859. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-09943-4

- Freeman T, Baum F, Lawless A, et al. Revisiting the ability of Australian primary healthcare services to respond to health inequity. Aust J Prim Health . 2016;22(4):332-338. doi:10.1071/PY14180

- Couzos S. Towards a National Primary Health Care Strategy: Fulfilling Aboriginal Peoples Aspirations to Close the Gap . National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation. 2009. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/35080/

- Napier AD, Ancarno C, Butler B, et al. Culture and health. Lancet . 2014;384(9954):1607-1639. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61603-2

- WHO. COVID-19 and the Social Determinants of Health and Health Equity: Evidence Brief . 2021. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240038387

- WHO. Social Determinants of Health . 2023. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

- McCrae JS, Robinson JAL, Spain AK, Byers K, Axelrod JL. The Mitigating Toxic Stress study design: approaches to developmental evaluation of pediatric health care innovations addressing social determinants of health and toxic stress. BMC Health Serv Res . 2021;21:71. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-06057-4

- Hosseinpoor AR, Stewart Williams J, Jann B, et al. Social determinants of sex differences in disability among older adults: a multi-country decomposition analysis using the World Health Survey. Int J Equity Health . 2012;11:52. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-11-52

- Kabore A, Afriyie-Gyawu E, Awua J, et al. Social ecological factors affecting substance abuse in Ghana (West Africa) using photovoice. Pan Afr Med J . 2019;34:214. doi:10.11604/pamj.2019.34.214.12851

- Bíró É, Vincze F, Mátyás G, Kósa K. Recursive path model for health literacy: the effect of social support and geographical residence. Front Public Health . 2021;9. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.724995

- Yuan B, Zhang T, Li J. Family support and transport cost: understanding health service among older people from the perspective of social-ecological model. Arch Public Health . 2022;80:173. doi:10.1186/s13690-022-00923-1

- Mahmoodi Z, Karimlou M, Sajjadi H, Dejman M, Vameghi M, Dolatian M. A communicative model of mothers’ lifestyles during pregnancy with low birth weight based on social determinants of health: a path analysis. Oman Med J . 2017 ;32(4):306-314. doi:10.5001/omj.2017.59

- Vella SA, Schweickle MJ, Sutcliffe J, Liddelow C, Swann C. A systems theory of mental health in recreational sport. Int J Environ Res Public Health . 2022;19(21):14244. doi:10.3390/ijerph192114244

- Henning S. The wellness of airline cabin attendants: A systems theory perspective. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure . 2015;4(1):1-11. Accessed February 15, 2023. http://www.ajhtl.com/archive.html

- Sutphin ST, McDonough S, Schrenkel A. The role of formal theory in social work research: formalizing family systems theory. Adv Soc Work . 2013;14(2):501-517. doi:10.18060/7942

- Colla R, Williams P, Oades LG, Camacho-Morles J. “A new hope” for positive psychology: a dynamic systems reconceptualization of hope theory. Front Psychol . 2022;13. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.809053

- Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129–136. doi:10.1126/science.847460

- Wade DT, HalliganPW. The biopsychosocial model of illness: a model whose time has come. Clin Rehabi l. 2017;31(8):995–1004. doi:10.1177/0269215517709890

- Ip L, Smith A, Papachristou I, Tolani E. 3 Dimensions for Long Term Conditions – creating a sustainable bio-psycho-social approach to healthcare. J Integr Care . 2019;19(4):5. doi:10.5334/ijic.s3005

- FrameWorks Institute. A Matter of Life and Death: Explaining the Wider Determinants of Health in the UK . FrameWorks Institute; 2022. Accessed February 15, 2023. https://www.frameworksinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/FWI-30-uk-health-brief-v3a.pdf

- Zemed A, Nigussie Chala K, Azeze Eriku G, Yalew Aschalew A. Health-related quality of life and associated factors among patients with stroke at tertiary level hospitals in Ethiopia. PLOS ONE . 2021;16(3):e0248481. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0248481

- Finch E, Foster M, Cruwys T, et al. Meeting unmet needs following minor stroke: the SUN randomised controlled trial protocol. BMC Health Serv Res . 2019;19:894. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4746-1

Qualitative Research – a practical guide for health and social care researchers and practitioners Copyright © 2023 by Tess Tsindos is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Theoretical Frameworks in Qualitative Research

- Vincent A. Anfara, Jr. - University of Tennessee, Knoxville, USA

- Norma T. Mertz - University of Tennessee, Knoxville, USA

- Description

The Second Edition of Theoretical Frameworks in Qualitative Research brings together some of today’s leading qualitative researchers to discuss the frameworks behind their published qualitative studies. They share how they found and chose a theoretical framework, from what discipline the framework was drawn, what the framework posits, and how it influenced their study. Both novice and experienced qualitative researchers are able to learn first-hand from various contributors as they reflect on the process and decisions involved in completing their study. The book also provides background for beginning researchers about the nature of theoretical frameworks and their importance in qualitative research; about differences in perspective about the role of theoretical frameworks; and about how to find and use a theoretical framework.

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

Committee decision because of the depth of the qualitative information.

Not the right fit for analysis course

useful for all types of health care professions

NEW TO THIS EDITION:

- Abstracts added to the beginning of each contributed chapter highlight what can be learned about the chapter’s theoretical frameworks.

- The contributing author’s published study is now displayed prominently after the abstract for easy access.

- A broader range of theoretical frameworks is presented and examined through three entirely new chapters, and a chapter that combines two chapters from the first edition, showing how to use multiple frameworks.

- New brief pieces in Chapter 12 by doctoral students show how they arrived at the frameworks used in their dissertations.

- Enhanced discussions cover the lessons to be learned from the contributing authors and further explain how to find a theoretical framework.

KEY FEATURES:

- A comprehensive examination of the role and influence of theoretical frameworks in qualitative research helps readers plan for their own qualitative research studies.

- A wide variety of distinctive, sometimes unusual, theoretical frameworks drawn from a number of disciplines are included.

- In-depth reflections on the use of a range of frameworks employed in accessible published studies help readers learn to use and understand theory.

- Real-world examples are detailed and explained by some of today's leading qualitative researchers.

- Expert and insightful guidance helps readers find a theoretical framework appropriate to their own study and also helps readers understand how to integrate the complexities of their frameworks into solid research designs.

Sample Materials & Chapters

For instructors, select a purchasing option.

The Ultimate Guide to Qualitative Research - Part 1: The Basics

- Introduction and overview

- What is qualitative research?

- What is qualitative data?

- Examples of qualitative data

- Qualitative vs. quantitative research

- Mixed methods

- Qualitative research preparation

- Theoretical perspective

- Introduction

Strategies for developing the theoretical framework

- Literature reviews

- Research question

- Conceptual framework

- Conceptual vs. theoretical framework

- Data collection

- Qualitative research methods

- Focus groups

- Observational research

- Case studies

- Ethnographical research

- Ethical considerations

- Confidentiality and privacy

- Power dynamics

- Reflexivity

Theoretical framework

The theoretical perspective provides the broader lens or orientation through which the researcher views the research topic and guides their overall understanding and approach. The theoretical framework, on the other hand, is a more specific and focused framework that connects the theoretical perspective to the data analysis strategy through pre-established theory.

A useful theoretical framework provides a structure for organizing and interpreting the data collected during the research study. Theoretical frameworks provide a specific lens through which the data is examined, allowing the researcher to identify recurring patterns, themes, and categories related to your research inquiry based on relevant theory.

Let's explore the idea of the theoretical framework in greater detail by exploring its place in qualitative research, particularly how it is generated and how it contributes to and guides your research study.

Theoretical framework vs. theoretical perspective

While these two terms may sound similar, they play very distinct roles in qualitative research . A theoretical perspective refers to the philosophical stance informing the methodology and thus provides a context for the research process. These perspectives could be rooted in various schools of thought like postmodernism, constructivism, or positivism, which fundamentally shape how researchers perceive reality and construct knowledge.

On the other hand, the theoretical framework represents the structure that can hold or support a theory of a research study. It presents a logical structure of connected concepts that help the researcher understand, explain, and predict how phenomena are interrelated. The theoretical framework can pull together various theories or ideas from different perspectives to provide a comprehensive approach to addressing the research problem.

Moreover, theoretical frameworks provide useful guidance as to which research methods are appropriate for your research project. If the theoretical framework you employ is relevant to individual perspectives and beliefs, then interviews may be more suitable for your research. On the other hand, if you are utilizing an existing theory about a certain social behavior, then ethnographic observations can help you more ably capture data from social interactions.

Later in this guide, we will also discuss conceptual frameworks , which help you visualize the essential concepts and data points in the context you are studying. For now, it is important to emphasize that these are all related but ultimately different ideas.

Example of a theoretical framework

Let's look at a simple example of a theoretical framework used to address a social science research problem. Consider a study examining the impact of social media on body image among adolescents. The theoretical perspective might be rooted in social constructivism, based on the assumption that our understanding of reality is shaped by social interactions and cultural context.

The theoretical framework, then, could draw on one or several theories to provide a comprehensive structure for examining this issue. For instance, it might combine elements of "social comparison theory" (which suggests that individuals determine their own social and personal worth based on how they stack up against others), "self-perception theory" (which posits that individuals develop their attitudes by observing their own behavior and concluding what attitudes must have caused it), and "cultivation theory" (which suggests that long-term immersion in a media environment leads to "cultivation", or adopting the attitudes and beliefs portrayed in the media).

This framework would provide the structure to understand how social media exposure influences adolescents' perceptions of their bodies, how they compare themselves to images seen on social media, and how these influences may shape their attitudes toward their own bodies.

Put your theories into focus with ATLAS.ti

Powerful data analysis to turn your data into insights and theory. Download a free trial today.

Other examples of theoretical frameworks

Let's briefly look at examples in other fields to put the idea of "theoretical framework" in greater context.

Political science

In a study investigating the influence of lobbying on legislative decisions, the theoretical framework could be rooted in the "pluralist theory" and "elite theory".

Pluralist theory views politics as a competition among groups, each one pressing for its preferred policies, while elite theory suggests that a small, cohesive elite group makes the most important decisions in society. The framework could combine these theories to examine the power dynamics in legislative decisions and the role of lobbying groups in influencing these outcomes.

Educational research

An educational research study aiming to understand the impact of parental involvement on children's academic success could employ a theoretical framework based on Bronfenbrenner's ecological systems theory and Epstein's theory of overlapping spheres of influence.

The ecological systems theory emphasizes the importance of multiple environmental systems on child development, while Epstein's theory focuses on the partnership between family, school, and community. The intersection of these theories allows for a comprehensive examination of parental involvement both in and outside of the school context.

Health services research

In a health services study exploring factors affecting patient adherence to medication regimes, the theoretical framework could draw from the health belief model and social cognitive theory.

The health belief model posits that people's beliefs about health problems, perceived benefits of action and barriers to action, and self-efficacy explain engagement in health-promoting behavior.

The social cognitive theory emphasizes the role of observational learning, social experience, and reciprocal determinism in behavior change. The framework combining these theories provides a holistic understanding of both personal and social influences on patient medication adherence.

Developing a theoretical framework involves a multi-step process that begins with a thorough literature review . This allows you to understand the existing theories and research related to your topic and identify gaps or unresolved puzzles that your study can address.

1. Identify key concepts: These might be the phenomena you are studying, the attributes of these phenomena, or the relationships between them. Identifying these can help you define the relevant data points to analyze.

2. Find relevant theories: Conduct a literature review to search for existing theories in academic research papers that relate to your key concepts. These theories might explain the phenomena you are studying, provide context for it, or suggest how the phenomena might be related. You can build off of one theory or multiple theories, but what is most important is that the theory is aligned with the concepts and research problem you are studying.

3. Map relationships: Outline how the theories you have found relate to one another and to your key concepts. This might involve drawing a diagram or writing a narrative that explains these relationships.

4. Refine the framework: As you conduct your research, refine your theoretical framework. This might involve adding new concepts or theories, removing concepts or theories that do not fit your data, or changing how you conceptualize the relationships between theories.

Remember, the theoretical framework is not set in stone. At the same time, it may start with existing knowledge, it is important to develop your own framework as you gather more data and gain a deeper understanding of your research topic and context.

In the end, a good theoretical framework guides your research question and methods so that you can ultimately generate new knowledge and theory that meaningfully contributes to the existing conversation around a topic.

Visualize your theories and analysis with ATLAS.ti

From literature review to research paper, ATLAS.ti makes the research process easier and more efficient. See how with a free trial.

Use of theoretical and conceptual frameworks in qualitative research

Affiliation.

- 1 University of Leeds, UK.

- PMID: 25059086

- DOI: 10.7748/nr.21.6.34.e1252

Aim: To debate the definition and use of theoretical and conceptual frameworks in qualitative research.

Background: There is a paucity of literature to help the novice researcher to understand what theoretical and conceptual frameworks are and how they should be used. This paper acknowledges the interchangeable usage of these terms and researchers' confusion about the differences between the two. It discusses how researchers have used theoretical and conceptual frameworks and the notion of conceptual models. Detail is given about how one researcher incorporated a conceptual framework throughout a research project, the purpose for doing so and how this led to a resultant conceptual model.

Review methods: Concepts from Abbott (1988) and Witz ( 1992 ) were used to provide a framework for research involving two case study sites. The framework was used to determine research questions and give direction to interviews and discussions to focus the research.

Discussion: Some research methods do not overtly use a theoretical framework or conceptual framework in their design, but this is implicit and underpins the method design, for example in grounded theory. Other qualitative methods use one or the other to frame the design of a research project or to explain the outcomes. An example is given of how a conceptual framework was used throughout a research project.

Conclusion: Theoretical and conceptual frameworks are terms that are regularly used in research but rarely explained. Textbooks should discuss what they are and how they can be used, so novice researchers understand how they can help with research design.

Implications for practice/research: Theoretical and conceptual frameworks need to be more clearly understood by researchers and correct terminology used to ensure clarity for novice researchers.

Keywords: Theoretical framework; case study; case study research.; conceptual framework; conceptual model; qualitative research; research design.

- Nursing Research / organization & administration*

- Qualitative Research*

- Research Design

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- CBE Life Sci Educ

- v.21(3); Fall 2022

Literature Reviews, Theoretical Frameworks, and Conceptual Frameworks: An Introduction for New Biology Education Researchers

Julie a. luft.

† Department of Mathematics, Social Studies, and Science Education, Mary Frances Early College of Education, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602-7124

Sophia Jeong

‡ Department of Teaching & Learning, College of Education & Human Ecology, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210

Robert Idsardi

§ Department of Biology, Eastern Washington University, Cheney, WA 99004

Grant Gardner

∥ Department of Biology, Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN 37132

Associated Data

To frame their work, biology education researchers need to consider the role of literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks as critical elements of the research and writing process. However, these elements can be confusing for scholars new to education research. This Research Methods article is designed to provide an overview of each of these elements and delineate the purpose of each in the educational research process. We describe what biology education researchers should consider as they conduct literature reviews, identify theoretical frameworks, and construct conceptual frameworks. Clarifying these different components of educational research studies can be helpful to new biology education researchers and the biology education research community at large in situating their work in the broader scholarly literature.

INTRODUCTION

Discipline-based education research (DBER) involves the purposeful and situated study of teaching and learning in specific disciplinary areas ( Singer et al. , 2012 ). Studies in DBER are guided by research questions that reflect disciplines’ priorities and worldviews. Researchers can use quantitative data, qualitative data, or both to answer these research questions through a variety of methodological traditions. Across all methodologies, there are different methods associated with planning and conducting educational research studies that include the use of surveys, interviews, observations, artifacts, or instruments. Ensuring the coherence of these elements to the discipline’s perspective also involves situating the work in the broader scholarly literature. The tools for doing this include literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks. However, the purpose and function of each of these elements is often confusing to new education researchers. The goal of this article is to introduce new biology education researchers to these three important elements important in DBER scholarship and the broader educational literature.

The first element we discuss is a review of research (literature reviews), which highlights the need for a specific research question, study problem, or topic of investigation. Literature reviews situate the relevance of the study within a topic and a field. The process may seem familiar to science researchers entering DBER fields, but new researchers may still struggle in conducting the review. Booth et al. (2016b) highlight some of the challenges novice education researchers face when conducting a review of literature. They point out that novice researchers struggle in deciding how to focus the review, determining the scope of articles needed in the review, and knowing how to be critical of the articles in the review. Overcoming these challenges (and others) can help novice researchers construct a sound literature review that can inform the design of the study and help ensure the work makes a contribution to the field.

The second and third highlighted elements are theoretical and conceptual frameworks. These guide biology education research (BER) studies, and may be less familiar to science researchers. These elements are important in shaping the construction of new knowledge. Theoretical frameworks offer a way to explain and interpret the studied phenomenon, while conceptual frameworks clarify assumptions about the studied phenomenon. Despite the importance of these constructs in educational research, biology educational researchers have noted the limited use of theoretical or conceptual frameworks in published work ( DeHaan, 2011 ; Dirks, 2011 ; Lo et al. , 2019 ). In reviewing articles published in CBE—Life Sciences Education ( LSE ) between 2015 and 2019, we found that fewer than 25% of the research articles had a theoretical or conceptual framework (see the Supplemental Information), and at times there was an inconsistent use of theoretical and conceptual frameworks. Clearly, these frameworks are challenging for published biology education researchers, which suggests the importance of providing some initial guidance to new biology education researchers.

Fortunately, educational researchers have increased their explicit use of these frameworks over time, and this is influencing educational research in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields. For instance, a quick search for theoretical or conceptual frameworks in the abstracts of articles in Educational Research Complete (a common database for educational research) in STEM fields demonstrates a dramatic change over the last 20 years: from only 778 articles published between 2000 and 2010 to 5703 articles published between 2010 and 2020, a more than sevenfold increase. Greater recognition of the importance of these frameworks is contributing to DBER authors being more explicit about such frameworks in their studies.

Collectively, literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual frameworks work to guide methodological decisions and the elucidation of important findings. Each offers a different perspective on the problem of study and is an essential element in all forms of educational research. As new researchers seek to learn about these elements, they will find different resources, a variety of perspectives, and many suggestions about the construction and use of these elements. The wide range of available information can overwhelm the new researcher who just wants to learn the distinction between these elements or how to craft them adequately.

Our goal in writing this paper is not to offer specific advice about how to write these sections in scholarly work. Instead, we wanted to introduce these elements to those who are new to BER and who are interested in better distinguishing one from the other. In this paper, we share the purpose of each element in BER scholarship, along with important points on its construction. We also provide references for additional resources that may be beneficial to better understanding each element. Table 1 summarizes the key distinctions among these elements.

Comparison of literature reviews, theoretical frameworks, and conceptual reviews

This article is written for the new biology education researcher who is just learning about these different elements or for scientists looking to become more involved in BER. It is a result of our own work as science education and biology education researchers, whether as graduate students and postdoctoral scholars or newly hired and established faculty members. This is the article we wish had been available as we started to learn about these elements or discussed them with new educational researchers in biology.

LITERATURE REVIEWS

Purpose of a literature review.

A literature review is foundational to any research study in education or science. In education, a well-conceptualized and well-executed review provides a summary of the research that has already been done on a specific topic and identifies questions that remain to be answered, thus illustrating the current research project’s potential contribution to the field and the reasoning behind the methodological approach selected for the study ( Maxwell, 2012 ). BER is an evolving disciplinary area that is redefining areas of conceptual emphasis as well as orientations toward teaching and learning (e.g., Labov et al. , 2010 ; American Association for the Advancement of Science, 2011 ; Nehm, 2019 ). As a result, building comprehensive, critical, purposeful, and concise literature reviews can be a challenge for new biology education researchers.

Building Literature Reviews

There are different ways to approach and construct a literature review. Booth et al. (2016a) provide an overview that includes, for example, scoping reviews, which are focused only on notable studies and use a basic method of analysis, and integrative reviews, which are the result of exhaustive literature searches across different genres. Underlying each of these different review processes are attention to the s earch process, a ppraisa l of articles, s ynthesis of the literature, and a nalysis: SALSA ( Booth et al. , 2016a ). This useful acronym can help the researcher focus on the process while building a specific type of review.

However, new educational researchers often have questions about literature reviews that are foundational to SALSA or other approaches. Common questions concern determining which literature pertains to the topic of study or the role of the literature review in the design of the study. This section addresses such questions broadly while providing general guidance for writing a narrative literature review that evaluates the most pertinent studies.

The literature review process should begin before the research is conducted. As Boote and Beile (2005 , p. 3) suggested, researchers should be “scholars before researchers.” They point out that having a good working knowledge of the proposed topic helps illuminate avenues of study. Some subject areas have a deep body of work to read and reflect upon, providing a strong foundation for developing the research question(s). For instance, the teaching and learning of evolution is an area of long-standing interest in the BER community, generating many studies (e.g., Perry et al. , 2008 ; Barnes and Brownell, 2016 ) and reviews of research (e.g., Sickel and Friedrichsen, 2013 ; Ziadie and Andrews, 2018 ). Emerging areas of BER include the affective domain, issues of transfer, and metacognition ( Singer et al. , 2012 ). Many studies in these areas are transdisciplinary and not always specific to biology education (e.g., Rodrigo-Peiris et al. , 2018 ; Kolpikova et al. , 2019 ). These newer areas may require reading outside BER; fortunately, summaries of some of these topics can be found in the Current Insights section of the LSE website.

In focusing on a specific problem within a broader research strand, a new researcher will likely need to examine research outside BER. Depending upon the area of study, the expanded reading list might involve a mix of BER, DBER, and educational research studies. Determining the scope of the reading is not always straightforward. A simple way to focus one’s reading is to create a “summary phrase” or “research nugget,” which is a very brief descriptive statement about the study. It should focus on the essence of the study, for example, “first-year nonmajor students’ understanding of evolution,” “metacognitive prompts to enhance learning during biochemistry,” or “instructors’ inquiry-based instructional practices after professional development programming.” This type of phrase should help a new researcher identify two or more areas to review that pertain to the study. Focusing on recent research in the last 5 years is a good first step. Additional studies can be identified by reading relevant works referenced in those articles. It is also important to read seminal studies that are more than 5 years old. Reading a range of studies should give the researcher the necessary command of the subject in order to suggest a research question.

Given that the research question(s) arise from the literature review, the review should also substantiate the selected methodological approach. The review and research question(s) guide the researcher in determining how to collect and analyze data. Often the methodological approach used in a study is selected to contribute knowledge that expands upon what has been published previously about the topic (see Institute of Education Sciences and National Science Foundation, 2013 ). An emerging topic of study may need an exploratory approach that allows for a description of the phenomenon and development of a potential theory. This could, but not necessarily, require a methodological approach that uses interviews, observations, surveys, or other instruments. An extensively studied topic may call for the additional understanding of specific factors or variables; this type of study would be well suited to a verification or a causal research design. These could entail a methodological approach that uses valid and reliable instruments, observations, or interviews to determine an effect in the studied event. In either of these examples, the researcher(s) may use a qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods methodological approach.

Even with a good research question, there is still more reading to be done. The complexity and focus of the research question dictates the depth and breadth of the literature to be examined. Questions that connect multiple topics can require broad literature reviews. For instance, a study that explores the impact of a biology faculty learning community on the inquiry instruction of faculty could have the following review areas: learning communities among biology faculty, inquiry instruction among biology faculty, and inquiry instruction among biology faculty as a result of professional learning. Biology education researchers need to consider whether their literature review requires studies from different disciplines within or outside DBER. For the example given, it would be fruitful to look at research focused on learning communities with faculty in STEM fields or in general education fields that result in instructional change. It is important not to be too narrow or too broad when reading. When the conclusions of articles start to sound similar or no new insights are gained, the researcher likely has a good foundation for a literature review. This level of reading should allow the researcher to demonstrate a mastery in understanding the researched topic, explain the suitability of the proposed research approach, and point to the need for the refined research question(s).

The literature review should include the researcher’s evaluation and critique of the selected studies. A researcher may have a large collection of studies, but not all of the studies will follow standards important in the reporting of empirical work in the social sciences. The American Educational Research Association ( Duran et al. , 2006 ), for example, offers a general discussion about standards for such work: an adequate review of research informing the study, the existence of sound and appropriate data collection and analysis methods, and appropriate conclusions that do not overstep or underexplore the analyzed data. The Institute of Education Sciences and National Science Foundation (2013) also offer Common Guidelines for Education Research and Development that can be used to evaluate collected studies.

Because not all journals adhere to such standards, it is important that a researcher review each study to determine the quality of published research, per the guidelines suggested earlier. In some instances, the research may be fatally flawed. Examples of such flaws include data that do not pertain to the question, a lack of discussion about the data collection, poorly constructed instruments, or an inadequate analysis. These types of errors result in studies that are incomplete, error-laden, or inaccurate and should be excluded from the review. Most studies have limitations, and the author(s) often make them explicit. For instance, there may be an instructor effect, recognized bias in the analysis, or issues with the sample population. Limitations are usually addressed by the research team in some way to ensure a sound and acceptable research process. Occasionally, the limitations associated with the study can be significant and not addressed adequately, which leaves a consequential decision in the hands of the researcher. Providing critiques of studies in the literature review process gives the reader confidence that the researcher has carefully examined relevant work in preparation for the study and, ultimately, the manuscript.

A solid literature review clearly anchors the proposed study in the field and connects the research question(s), the methodological approach, and the discussion. Reviewing extant research leads to research questions that will contribute to what is known in the field. By summarizing what is known, the literature review points to what needs to be known, which in turn guides decisions about methodology. Finally, notable findings of the new study are discussed in reference to those described in the literature review.

Within published BER studies, literature reviews can be placed in different locations in an article. When included in the introductory section of the study, the first few paragraphs of the manuscript set the stage, with the literature review following the opening paragraphs. Cooper et al. (2019) illustrate this approach in their study of course-based undergraduate research experiences (CUREs). An introduction discussing the potential of CURES is followed by an analysis of the existing literature relevant to the design of CUREs that allows for novel student discoveries. Within this review, the authors point out contradictory findings among research on novel student discoveries. This clarifies the need for their study, which is described and highlighted through specific research aims.

A literature reviews can also make up a separate section in a paper. For example, the introduction to Todd et al. (2019) illustrates the need for their research topic by highlighting the potential of learning progressions (LPs) and suggesting that LPs may help mitigate learning loss in genetics. At the end of the introduction, the authors state their specific research questions. The review of literature following this opening section comprises two subsections. One focuses on learning loss in general and examines a variety of studies and meta-analyses from the disciplines of medical education, mathematics, and reading. The second section focuses specifically on LPs in genetics and highlights student learning in the midst of LPs. These separate reviews provide insights into the stated research question.

Suggestions and Advice

A well-conceptualized, comprehensive, and critical literature review reveals the understanding of the topic that the researcher brings to the study. Literature reviews should not be so big that there is no clear area of focus; nor should they be so narrow that no real research question arises. The task for a researcher is to craft an efficient literature review that offers a critical analysis of published work, articulates the need for the study, guides the methodological approach to the topic of study, and provides an adequate foundation for the discussion of the findings.

In our own writing of literature reviews, there are often many drafts. An early draft may seem well suited to the study because the need for and approach to the study are well described. However, as the results of the study are analyzed and findings begin to emerge, the existing literature review may be inadequate and need revision. The need for an expanded discussion about the research area can result in the inclusion of new studies that support the explanation of a potential finding. The literature review may also prove to be too broad. Refocusing on a specific area allows for more contemplation of a finding.

It should be noted that there are different types of literature reviews, and many books and articles have been written about the different ways to embark on these types of reviews. Among these different resources, the following may be helpful in considering how to refine the review process for scholarly journals:

- Booth, A., Sutton, A., & Papaioannou, D. (2016a). Systemic approaches to a successful literature review (2nd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. This book addresses different types of literature reviews and offers important suggestions pertaining to defining the scope of the literature review and assessing extant studies.

- Booth, W. C., Colomb, G. G., Williams, J. M., Bizup, J., & Fitzgerald, W. T. (2016b). The craft of research (4th ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. This book can help the novice consider how to make the case for an area of study. While this book is not specifically about literature reviews, it offers suggestions about making the case for your study.

- Galvan, J. L., & Galvan, M. C. (2017). Writing literature reviews: A guide for students of the social and behavioral sciences (7th ed.). Routledge. This book offers guidance on writing different types of literature reviews. For the novice researcher, there are useful suggestions for creating coherent literature reviews.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORKS

Purpose of theoretical frameworks.

As new education researchers may be less familiar with theoretical frameworks than with literature reviews, this discussion begins with an analogy. Envision a biologist, chemist, and physicist examining together the dramatic effect of a fog tsunami over the ocean. A biologist gazing at this phenomenon may be concerned with the effect of fog on various species. A chemist may be interested in the chemical composition of the fog as water vapor condenses around bits of salt. A physicist may be focused on the refraction of light to make fog appear to be “sitting” above the ocean. While observing the same “objective event,” the scientists are operating under different theoretical frameworks that provide a particular perspective or “lens” for the interpretation of the phenomenon. Each of these scientists brings specialized knowledge, experiences, and values to this phenomenon, and these influence the interpretation of the phenomenon. The scientists’ theoretical frameworks influence how they design and carry out their studies and interpret their data.

Within an educational study, a theoretical framework helps to explain a phenomenon through a particular lens and challenges and extends existing knowledge within the limitations of that lens. Theoretical frameworks are explicitly stated by an educational researcher in the paper’s framework, theory, or relevant literature section. The framework shapes the types of questions asked, guides the method by which data are collected and analyzed, and informs the discussion of the results of the study. It also reveals the researcher’s subjectivities, for example, values, social experience, and viewpoint ( Allen, 2017 ). It is essential that a novice researcher learn to explicitly state a theoretical framework, because all research questions are being asked from the researcher’s implicit or explicit assumptions of a phenomenon of interest ( Schwandt, 2000 ).

Selecting Theoretical Frameworks

Theoretical frameworks are one of the most contemplated elements in our work in educational research. In this section, we share three important considerations for new scholars selecting a theoretical framework.

The first step in identifying a theoretical framework involves reflecting on the phenomenon within the study and the assumptions aligned with the phenomenon. The phenomenon involves the studied event. There are many possibilities, for example, student learning, instructional approach, or group organization. A researcher holds assumptions about how the phenomenon will be effected, influenced, changed, or portrayed. It is ultimately the researcher’s assumption(s) about the phenomenon that aligns with a theoretical framework. An example can help illustrate how a researcher’s reflection on the phenomenon and acknowledgment of assumptions can result in the identification of a theoretical framework.

In our example, a biology education researcher may be interested in exploring how students’ learning of difficult biological concepts can be supported by the interactions of group members. The phenomenon of interest is the interactions among the peers, and the researcher assumes that more knowledgeable students are important in supporting the learning of the group. As a result, the researcher may draw on Vygotsky’s (1978) sociocultural theory of learning and development that is focused on the phenomenon of student learning in a social setting. This theory posits the critical nature of interactions among students and between students and teachers in the process of building knowledge. A researcher drawing upon this framework holds the assumption that learning is a dynamic social process involving questions and explanations among students in the classroom and that more knowledgeable peers play an important part in the process of building conceptual knowledge.

It is important to state at this point that there are many different theoretical frameworks. Some frameworks focus on learning and knowing, while other theoretical frameworks focus on equity, empowerment, or discourse. Some frameworks are well articulated, and others are still being refined. For a new researcher, it can be challenging to find a theoretical framework. Two of the best ways to look for theoretical frameworks is through published works that highlight different frameworks.

When a theoretical framework is selected, it should clearly connect to all parts of the study. The framework should augment the study by adding a perspective that provides greater insights into the phenomenon. It should clearly align with the studies described in the literature review. For instance, a framework focused on learning would correspond to research that reported different learning outcomes for similar studies. The methods for data collection and analysis should also correspond to the framework. For instance, a study about instructional interventions could use a theoretical framework concerned with learning and could collect data about the effect of the intervention on what is learned. When the data are analyzed, the theoretical framework should provide added meaning to the findings, and the findings should align with the theoretical framework.

A study by Jensen and Lawson (2011) provides an example of how a theoretical framework connects different parts of the study. They compared undergraduate biology students in heterogeneous and homogeneous groups over the course of a semester. Jensen and Lawson (2011) assumed that learning involved collaboration and more knowledgeable peers, which made Vygotsky’s (1978) theory a good fit for their study. They predicted that students in heterogeneous groups would experience greater improvement in their reasoning abilities and science achievements with much of the learning guided by the more knowledgeable peers.

In the enactment of the study, they collected data about the instruction in traditional and inquiry-oriented classes, while the students worked in homogeneous or heterogeneous groups. To determine the effect of working in groups, the authors also measured students’ reasoning abilities and achievement. Each data-collection and analysis decision connected to understanding the influence of collaborative work.

Their findings highlighted aspects of Vygotsky’s (1978) theory of learning. One finding, for instance, posited that inquiry instruction, as a whole, resulted in reasoning and achievement gains. This links to Vygotsky (1978) , because inquiry instruction involves interactions among group members. A more nuanced finding was that group composition had a conditional effect. Heterogeneous groups performed better with more traditional and didactic instruction, regardless of the reasoning ability of the group members. Homogeneous groups worked better during interaction-rich activities for students with low reasoning ability. The authors attributed the variation to the different types of helping behaviors of students. High-performing students provided the answers, while students with low reasoning ability had to work collectively through the material. In terms of Vygotsky (1978) , this finding provided new insights into the learning context in which productive interactions can occur for students.

Another consideration in the selection and use of a theoretical framework pertains to its orientation to the study. This can result in the theoretical framework prioritizing individuals, institutions, and/or policies ( Anfara and Mertz, 2014 ). Frameworks that connect to individuals, for instance, could contribute to understanding their actions, learning, or knowledge. Institutional frameworks, on the other hand, offer insights into how institutions, organizations, or groups can influence individuals or materials. Policy theories provide ways to understand how national or local policies can dictate an emphasis on outcomes or instructional design. These different types of frameworks highlight different aspects in an educational setting, which influences the design of the study and the collection of data. In addition, these different frameworks offer a way to make sense of the data. Aligning the data collection and analysis with the framework ensures that a study is coherent and can contribute to the field.

New understandings emerge when different theoretical frameworks are used. For instance, Ebert-May et al. (2015) prioritized the individual level within conceptual change theory (see Posner et al. , 1982 ). In this theory, an individual’s knowledge changes when it no longer fits the phenomenon. Ebert-May et al. (2015) designed a professional development program challenging biology postdoctoral scholars’ existing conceptions of teaching. The authors reported that the biology postdoctoral scholars’ teaching practices became more student-centered as they were challenged to explain their instructional decision making. According to the theory, the biology postdoctoral scholars’ dissatisfaction in their descriptions of teaching and learning initiated change in their knowledge and instruction. These results reveal how conceptual change theory can explain the learning of participants and guide the design of professional development programming.

The communities of practice (CoP) theoretical framework ( Lave, 1988 ; Wenger, 1998 ) prioritizes the institutional level , suggesting that learning occurs when individuals learn from and contribute to the communities in which they reside. Grounded in the assumption of community learning, the literature on CoP suggests that, as individuals interact regularly with the other members of their group, they learn about the rules, roles, and goals of the community ( Allee, 2000 ). A study conducted by Gehrke and Kezar (2017) used the CoP framework to understand organizational change by examining the involvement of individual faculty engaged in a cross-institutional CoP focused on changing the instructional practice of faculty at each institution. In the CoP, faculty members were involved in enhancing instructional materials within their department, which aligned with an overarching goal of instituting instruction that embraced active learning. Not surprisingly, Gehrke and Kezar (2017) revealed that faculty who perceived the community culture as important in their work cultivated institutional change. Furthermore, they found that institutional change was sustained when key leaders served as mentors and provided support for faculty, and as faculty themselves developed into leaders. This study reveals the complexity of individual roles in a COP in order to support institutional instructional change.

It is important to explicitly state the theoretical framework used in a study, but elucidating a theoretical framework can be challenging for a new educational researcher. The literature review can help to identify an applicable theoretical framework. Focal areas of the review or central terms often connect to assumptions and assertions associated with the framework that pertain to the phenomenon of interest. Another way to identify a theoretical framework is self-reflection by the researcher on personal beliefs and understandings about the nature of knowledge the researcher brings to the study ( Lysaght, 2011 ). In stating one’s beliefs and understandings related to the study (e.g., students construct their knowledge, instructional materials support learning), an orientation becomes evident that will suggest a particular theoretical framework. Theoretical frameworks are not arbitrary , but purposefully selected.

With experience, a researcher may find expanded roles for theoretical frameworks. Researchers may revise an existing framework that has limited explanatory power, or they may decide there is a need to develop a new theoretical framework. These frameworks can emerge from a current study or the need to explain a phenomenon in a new way. Researchers may also find that multiple theoretical frameworks are necessary to frame and explore a problem, as different frameworks can provide different insights into a problem.

Finally, it is important to recognize that choosing “x” theoretical framework does not necessarily mean a researcher chooses “y” methodology and so on, nor is there a clear-cut, linear process in selecting a theoretical framework for one’s study. In part, the nonlinear process of identifying a theoretical framework is what makes understanding and using theoretical frameworks challenging. For the novice scholar, contemplating and understanding theoretical frameworks is essential. Fortunately, there are articles and books that can help:

- Creswell, J. W. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage. This book provides an overview of theoretical frameworks in general educational research.

- Ding, L. (2019). Theoretical perspectives of quantitative physics education research. Physical Review Physics Education Research , 15 (2), 020101-1–020101-13. This paper illustrates how a DBER field can use theoretical frameworks.

- Nehm, R. (2019). Biology education research: Building integrative frameworks for teaching and learning about living systems. Disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Science Education Research , 1 , ar15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43031-019-0017-6 . This paper articulates the need for studies in BER to explicitly state theoretical frameworks and provides examples of potential studies.

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice . Sage. This book also provides an overview of theoretical frameworks, but for both research and evaluation.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORKS

Purpose of a conceptual framework.

A conceptual framework is a description of the way a researcher understands the factors and/or variables that are involved in the study and their relationships to one another. The purpose of a conceptual framework is to articulate the concepts under study using relevant literature ( Rocco and Plakhotnik, 2009 ) and to clarify the presumed relationships among those concepts ( Rocco and Plakhotnik, 2009 ; Anfara and Mertz, 2014 ). Conceptual frameworks are different from theoretical frameworks in both their breadth and grounding in established findings. Whereas a theoretical framework articulates the lens through which a researcher views the work, the conceptual framework is often more mechanistic and malleable.

Conceptual frameworks are broader, encompassing both established theories (i.e., theoretical frameworks) and the researchers’ own emergent ideas. Emergent ideas, for example, may be rooted in informal and/or unpublished observations from experience. These emergent ideas would not be considered a “theory” if they are not yet tested, supported by systematically collected evidence, and peer reviewed. However, they do still play an important role in the way researchers approach their studies. The conceptual framework allows authors to clearly describe their emergent ideas so that connections among ideas in the study and the significance of the study are apparent to readers.

Constructing Conceptual Frameworks

Including a conceptual framework in a research study is important, but researchers often opt to include either a conceptual or a theoretical framework. Either may be adequate, but both provide greater insight into the research approach. For instance, a research team plans to test a novel component of an existing theory. In their study, they describe the existing theoretical framework that informs their work and then present their own conceptual framework. Within this conceptual framework, specific topics portray emergent ideas that are related to the theory. Describing both frameworks allows readers to better understand the researchers’ assumptions, orientations, and understanding of concepts being investigated. For example, Connolly et al. (2018) included a conceptual framework that described how they applied a theoretical framework of social cognitive career theory (SCCT) to their study on teaching programs for doctoral students. In their conceptual framework, the authors described SCCT, explained how it applied to the investigation, and drew upon results from previous studies to justify the proposed connections between the theory and their emergent ideas.

In some cases, authors may be able to sufficiently describe their conceptualization of the phenomenon under study in an introduction alone, without a separate conceptual framework section. However, incomplete descriptions of how the researchers conceptualize the components of the study may limit the significance of the study by making the research less intelligible to readers. This is especially problematic when studying topics in which researchers use the same terms for different constructs or different terms for similar and overlapping constructs (e.g., inquiry, teacher beliefs, pedagogical content knowledge, or active learning). Authors must describe their conceptualization of a construct if the research is to be understandable and useful.

There are some key areas to consider regarding the inclusion of a conceptual framework in a study. To begin with, it is important to recognize that conceptual frameworks are constructed by the researchers conducting the study ( Rocco and Plakhotnik, 2009 ; Maxwell, 2012 ). This is different from theoretical frameworks that are often taken from established literature. Researchers should bring together ideas from the literature, but they may be influenced by their own experiences as a student and/or instructor, the shared experiences of others, or thought experiments as they construct a description, model, or representation of their understanding of the phenomenon under study. This is an exercise in intellectual organization and clarity that often considers what is learned, known, and experienced. The conceptual framework makes these constructs explicitly visible to readers, who may have different understandings of the phenomenon based on their prior knowledge and experience. There is no single method to go about this intellectual work.

Reeves et al. (2016) is an example of an article that proposed a conceptual framework about graduate teaching assistant professional development evaluation and research. The authors used existing literature to create a novel framework that filled a gap in current research and practice related to the training of graduate teaching assistants. This conceptual framework can guide the systematic collection of data by other researchers because the framework describes the relationships among various factors that influence teaching and learning. The Reeves et al. (2016) conceptual framework may be modified as additional data are collected and analyzed by other researchers. This is not uncommon, as conceptual frameworks can serve as catalysts for concerted research efforts that systematically explore a phenomenon (e.g., Reynolds et al. , 2012 ; Brownell and Kloser, 2015 ).

Sabel et al. (2017) used a conceptual framework in their exploration of how scaffolds, an external factor, interact with internal factors to support student learning. Their conceptual framework integrated principles from two theoretical frameworks, self-regulated learning and metacognition, to illustrate how the research team conceptualized students’ use of scaffolds in their learning ( Figure 1 ). Sabel et al. (2017) created this model using their interpretations of these two frameworks in the context of their teaching.

Conceptual framework from Sabel et al. (2017) .

A conceptual framework should describe the relationship among components of the investigation ( Anfara and Mertz, 2014 ). These relationships should guide the researcher’s methods of approaching the study ( Miles et al. , 2014 ) and inform both the data to be collected and how those data should be analyzed. Explicitly describing the connections among the ideas allows the researcher to justify the importance of the study and the rigor of the research design. Just as importantly, these frameworks help readers understand why certain components of a system were not explored in the study. This is a challenge in education research, which is rooted in complex environments with many variables that are difficult to control.

For example, Sabel et al. (2017) stated: “Scaffolds, such as enhanced answer keys and reflection questions, can help students and instructors bridge the external and internal factors and support learning” (p. 3). They connected the scaffolds in the study to the three dimensions of metacognition and the eventual transformation of existing ideas into new or revised ideas. Their framework provides a rationale for focusing on how students use two different scaffolds, and not on other factors that may influence a student’s success (self-efficacy, use of active learning, exam format, etc.).

In constructing conceptual frameworks, researchers should address needed areas of study and/or contradictions discovered in literature reviews. By attending to these areas, researchers can strengthen their arguments for the importance of a study. For instance, conceptual frameworks can address how the current study will fill gaps in the research, resolve contradictions in existing literature, or suggest a new area of study. While a literature review describes what is known and not known about the phenomenon, the conceptual framework leverages these gaps in describing the current study ( Maxwell, 2012 ). In the example of Sabel et al. (2017) , the authors indicated there was a gap in the literature regarding how scaffolds engage students in metacognition to promote learning in large classes. Their study helps fill that gap by describing how scaffolds can support students in the three dimensions of metacognition: intelligibility, plausibility, and wide applicability. In another example, Lane (2016) integrated research from science identity, the ethic of care, the sense of belonging, and an expertise model of student success to form a conceptual framework that addressed the critiques of other frameworks. In a more recent example, Sbeglia et al. (2021) illustrated how a conceptual framework influences the methodological choices and inferences in studies by educational researchers.

Sometimes researchers draw upon the conceptual frameworks of other researchers. When a researcher’s conceptual framework closely aligns with an existing framework, the discussion may be brief. For example, Ghee et al. (2016) referred to portions of SCCT as their conceptual framework to explain the significance of their work on students’ self-efficacy and career interests. Because the authors’ conceptualization of this phenomenon aligned with a previously described framework, they briefly mentioned the conceptual framework and provided additional citations that provided more detail for the readers.

Within both the BER and the broader DBER communities, conceptual frameworks have been used to describe different constructs. For example, some researchers have used the term “conceptual framework” to describe students’ conceptual understandings of a biological phenomenon. This is distinct from a researcher’s conceptual framework of the educational phenomenon under investigation, which may also need to be explicitly described in the article. Other studies have presented a research logic model or flowchart of the research design as a conceptual framework. These constructions can be quite valuable in helping readers understand the data-collection and analysis process. However, a model depicting the study design does not serve the same role as a conceptual framework. Researchers need to avoid conflating these constructs by differentiating the researchers’ conceptual framework that guides the study from the research design, when applicable.

Explicitly describing conceptual frameworks is essential in depicting the focus of the study. We have found that being explicit in a conceptual framework means using accepted terminology, referencing prior work, and clearly noting connections between terms. This description can also highlight gaps in the literature or suggest potential contributions to the field of study. A well-elucidated conceptual framework can suggest additional studies that may be warranted. This can also spur other researchers to consider how they would approach the examination of a phenomenon and could result in a revised conceptual framework.