Leadership agility in the context of organisational agility: a systematic literature review

- Published: 17 April 2024

Cite this article

- Latika Tandon ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9937-072X 1 ,

- Tithi Bhatnagar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8469-7658 1 , 2 &

- Tanushree Sharma ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7727-0258 3

17 Accesses

Explore all metrics

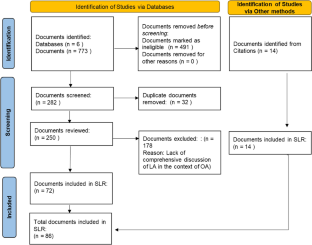

Organisations across the globe are looking to become agile and are seeking leaders to guide their transformation to agility. This paper conducts a systematic literature review across eighty-six papers spanning over 25 years (1999–2023), to develop an overview of how leadership agility is conceptualized in the context of organisational agility in the extant literature. This systematic review was conducted using the PRISMA framework. The databases searched for the review were: EBSCO, Emerald Insight, JStor, ProQuest, ScienceDirect, and Scopus. The data thus collected was organised and integrated using reflective thematic synthesis. Literature suggests that leadership agility is one of the key dimensions to foster organisational agility, though challenging in practice and difficult to implement. Based on the analysis of extant literature, this paper identifies four emergent themes of leadership agility: Leadership Agility Mindsets; Leadership Agility Competencies; Leadership Agility Styles; and Leadership Organisational Agility Functions . This study has conceptualized a framework of leadership agility in the context of organisational agility, anchored in the interplay of the emergent themes and their categories, contributing to leadership agility research, and promoting its adoption by the practitioners.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Agile Leadership and Bootlegging Behavior: Does Leadership Coping Dynamics Matter?

Positive Leadership: Moving Towards an Integrated Definition and Interventions

Leadership and Change Management: Examining Gender, Cultural and ‘Hero Leader’ Stereotypes

Data availability.

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Adhiatma A, Fachrunnisa O, Lukman N, Majid MNA (2023) Comparative study on workforce transformation strategy and SME policies in Indonesia and Malaysia. Eng Manage Prod Ser 15(4):1–11. https://doi.org/10.2478/emj-2023-0024

Article Google Scholar

Ahmed J, Mrugalska B, Akkaya B (2022) Agile management and VUCA 2.0 (VUCA-RR) during industry 4.0. In: Akkaya B, Guah MW, Jermsittiparsert K, Bulinska-Stangrecka H, Kaya Y (eds) Agile management and VUCA-RR: opportunities and threats in industry 4.0 towards society 5.0. Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80262-325-320220002

Chapter Google Scholar

Akkaya B, Tabak A (2020) The link between organizational agility and leadership: a research in science parks. Acad Strateg Manag J 19:1–17

Google Scholar

Akkaya B, Waritay-Guah M, Jermsittiparsert K, Bulinska-Stangrecka H, Kaya-Koçyiğit Y (2022) Agile management and VUCA-RR opportunities and threats in industry 4.0 towards society 5.0. Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley

Book Google Scholar

Akkaya B, Üstgörül S (2020) Leadership styles and female managers in perspective of agile leadership. Agile Bus Leadersh Methods Ind 4:121–137. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80043-380-920201008

Akkaya B, Sever E (2022) Agile leadership and organization performance in the perspective of VUCA. In: Post-pandemic talent management models in knowledge organizations. IGI Global

Aldianto L, Anggadwita G, Permatasari A, Mirzanti IR, Williamson IO (2021) Toward a business resilience framework for startups. Sustainability (switzerland) 13(6):1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063132

Appelbaum SH, Calla R, Desautels D, Hasan L (2017a) The challenges of organizational agility (part 1). Ind Commer Train 49(1):6–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICT-05-2016-0027

Appelbaum SH, Calla R, Desautels D, Hasan LN (2017b) The challenges of organizational agility: part 2. Ind Commer Train 49(2):69–74. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICT-05-2016-0028

As Global Growth Slows, Developing Economies Face Risk of ‘Hard Landing.’ (2022) The World Bank

Asseraf Y, Gnizy I (2022) Translating strategy into action: the importance of an agile mindset and agile slack in international business. Int Bus Rev 31(6):102036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2022.102036

Attar M, Abdul-Kareem A (2020) The role of agile leadership in organisational agility. In: Akkaya B (ed) Agile business leadership methods for industry 40. Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 171–191. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80043-380-920201011

Avery CM (2004) The mindset of an agile leader. Cut IT J 17(6):22–27

Balázs V, Éva S (2023) Unlocking the key dimensions of organizational agility: a systematic literature review on leadership, structural and cultural antecedents. Soc Econ 45. https://doi.org/10.1556/204.2023.00023

Benchea L, Ilie AG (2023) Preparing for a new world of work: leadership styles reconfigured in the digital age. Eur J Interdiscip Stud 15(1):135–143. https://doi.org/10.24818/ejis.2023.10

Booth A, Sutton A, Papaioannou D (2016) Systematic approaches to a successful literature review, 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Brandt EN, Kjellström S, Andersson A-C (2019) Transformational change by a post-conventional leader. Leadersh Org Dev J 40(4):457–471. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-07-2018-0273

Buttigieg SC, Cassia MV, Cassar V (2023) The relationship between transformational leadership, leadership agility, work engagement and adaptive performance: a theoretically informed empirical study. In: Chambers N (ed) Research handbook on leadership in healthcare. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 235–251

Chakraborty T, Awan TM, Natarajan A, Kamran M (eds) (2023) Agile leadership for industry 4.0: an indispensable approach for the digital era, 1 edn. AAP/Apple Academic Press

Chatwani N (2019) Agility revisited. In: Chatwani N (ed) Organisational agility. Springer International Publishing, Berlin, pp 1–21

De Smet A, Lurie M, St George A (2018) Leading agile transformation: The new capabilities leaders need to build 21st-century organizations. Mckinsey.com, October 2018.

Denning S (2016) Agile’s ten implementation challenges. Strategy Leadersh 44(5):15–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/SL-08-2016-0065

Denning S (2018a) Succeeding in an increasingly Agile world. Strategy Leadersh 46(3):3–9. https://doi.org/10.1108/SL-03-2018-0021

Denning S (2018b) The role of the C-suite in Agile transformation: the case of Amazon. Strategy Leadersh 46(6):14–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/SL-10-2018-0094

Denning S (2019a) Lessons learned from mapping successful and unsuccessful Agile transformation journeys. Strategy Leadersh 47(4):3–11. https://doi.org/10.1108/SL-04-2019-0052

Denning S (2019b) The ten stages of the Agile transformation journey. Strategy Leadersh 47(1):3–10. https://doi.org/10.1108/SL-11-2018-0109

Doz Y, Kosonen M (2008) The dynamics of strategic agility: Nokia’s rollercoaster experience. Calif Manage Rev 50(3):95–118. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166447

Dulay S (ed) (2023) Empowering educational leaders: How to thrive in a volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous world. Peter Lang, Lausanne

Eilers K, Peters C, Leimeister JM (2022) Why the agile mindset matters. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 179:121650. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121650

Esamah A, Aujirapongpan S, Rakangthong NK, Imjai N (2023) Agile leadership and digital transformation in savings cooperative limited: impact on sustainable performance amidst COVID-19. J Hum Earth Future 4(1):36–53. https://doi.org/10.28991/HEF-2023-04-01-04

Fachrunnisa O, Adhiatma A, Lukman N, Ab-Majid MN (2020) Towards SMEs’ digital transformation: the role of agile leadership and strategic flexibility. J Small Bus Strategy 30:65–85

Felipe CM, Roldán JL, Leal-Rodríguez AL (2016) An explanatory and predictive model for organizational agility. J Bus Res 69(10):4624–4631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.014

Fernandes V, Wong W, Noonan M (2023) Developing adaptability and agility in leadership amidst the COVID-19 crisis: experiences of early-career school principals. Int J Educ Manag 37(2):483–506. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-02-2022-0076

Garton E, Noble A (2017) How to make agile work for the C-Suite. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2017/07/how-to-make-agile-work-for-the-c-suite

Govuzela S, Mafini C (2019) Organisational agility, business best practices and the performance of small to medium enterprises in South Africa. S Afr J Bus Manag 50(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajbm.v50i1.1417

Gren L, Ralph P (2022) What makes effective leadership in agile software development teams? In: Proceedings of the 44th international conference on software engineering, pp. 2402–2414. https://doi.org/10.1145/3510003.3510100

Gren L, Lindman M, Stray V, Hoda R, Paasivaara M, Kruchten P (2020) Agile processes in software engineering and extreme programming. 21st International Conference on Agile Software Development XP 2020 Copenhagen Denmark June 8–12, 2020 Proceedings What an Agile Leader Does: The Group Dynamics Perspective. Springer, Cham, pp 178–194. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49392-9

Grześ B (2023) Managing an agile organization – key determinants of orgnizational agility. Scientific Papers of Silesian University of Technology Organization and Management Series. 2023(172). https://doi.org/10.29119/1641-3466.2023.172.17

Hartney E, Melis E, Taylor D, Dickson G, Tholl B, Grimes K, Chan M-K, Van Aerde J, Horsley T (2022) Leading through the first wave of COVID: a Canadian action research study. Leadersh Health Serv 35(1):30–45. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHS-05-2021-0042

Hill L (2020) Being the agile boss. MIT SMR, Fall (2020)

Hofstede G, Hofstede GJ, Minkov M (2005) Cultures and organizations: software of the mind. Choice Rev 42(10):42–5937. https://doi.org/10.5860/CHOICE.42-5937

Holbeche L (2018) Organisational effectiveness and agility. J Organ Eff People Perform 5(4):302–313. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-07-2018-0044

Holbeche L (2019) Designing sustainably agile and resilient organizations. Syst Res Behav Sci 36(5):668–677. https://doi.org/10.1002/sres.2624

Horney N, Pasmore B, O’Shea T (2010) Leadership agility: a business imperative for a VUCA world. People Strategy 33(4):34

Howieson B, Grant K (2022) Wicked leadership development for wicked problems. In: Holland P, Bartram T, Garavan T, Grant K (eds) The emerald handbook of work, workplaces and disruptive issues in HRM. Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80071-779-420221030

Jansen JJP, Vera D, Crossan M (2009) Strategic leadership for exploration and exploitation: the moderating role of environmental dynamism. Leadersh Q 20(1):5–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.11.008

Joiner B (2009) Creating a culture of agile leaders: a developmental approach. People Strategy 32(4):28–35

Joiner B (2012) How to build an agile leader. Chief Learn off 11(8):48–51

Joiner B, Josephs S (2007) Developing agile leaders. Ind Commer Train 39(1):35–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/00197850710721381

Jones S, Cass D (2022) Agile leadership: eight steps to becoming an agile team leader. Eff Exec 25(1):7–12

Kaya Y (2023) Agile leadership from the perspective of dynamic capabilities and creating value. Sustainability 15(21):15253. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152115253

Keleş HN (2023) Agile leadership in schools. In: Empowering educational leaders: How to thrive in a volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous world. Peter Lang AG

Konrad-Maerk M, Gfrerer A, Hutter K (2022) From transformational to agile leadership: what future skills it takes to act as agile leaders. Acad Manag Proc 2022(1):12343. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2022.12343abstract

Kumar S, Ray S (2023) Moving towards agile leadership to help organizations succeed. IUP J Soft Skills 17(1):2023. ProQuest

Lang D, Rumsey C (2018) Business disruption is here to stay: What should leaders do? Qual Access Success 19(S3):35–40

Leslie J (2015) The leadership gap: what you need, and still don’t have, when it comes to leadership talent. Cent Creative Leadersh. https://doi.org/10.35613/ccl.2015.1014 (2015).

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 339(1):b2700. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700

Luthia M (2023) Agile Leadership for Industry 4.0. An Indispensable Approach for the Digital Era. Apple Academic Press, New York

MacLean D, MacIntosh R, Seidl D (2015) Rethinking dynamic capabilities from a creative action perspective. Strateg Organ 13(4):340–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127015593274

McKenzie J, Aitken P (2012) Learning to lead the knowledgeable organization: developing leadership agility. Strateg HR Rev 11(6):329–334. https://doi.org/10.1108/14754391211264794

McPherson B (2016) Agile, adaptive leaders. Hum Resour Manag Int Dig 24(2):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1108/HRMID-11-2015-0171

Menon S, Suresh M (2021) Factors influencing organizational agility in higher education. Benchmark Int J 28(1):307–332. https://doi.org/10.1108/BIJ-04-2020-0151

Meyer R, Meijers R (2017) Leadership Agility: Developing Your Repertoire of Leadership Styles, 1st edn. Routledge, London

Modi S, Strode D (2020) Leadership in agile software development: a systematic literature review. In: ACIS 2020 proceedings. 55. https://aisel.aisnet.org/acis2020/55

Morton J, Stacey P, Mohn M (2018) Building and maintaining strategic agility: an agenda and framework for executive IT leaders. Calif Manage Rev 61(1):94–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008125618790245

Muafi M, Diamastuti E, Pambudi A (2020) Service innovation strategic consensus: a lesson from the Islamic banking industry in Indonesia. J Asian Finance Econ Bus 7(11):401–411. https://doi.org/10.13106/JAFEB.2020.VOL7.NO11.401

Muafi M, Uyun Q (2019) Leadership agility, the influence on the organizational learning and organizational innovation and how to reduce imitation orientation. Int J Qual Res 13(2):467–484. https://doi.org/10.24874/IJQR13.02-14

Mukherjee T (2023) The power of empathy: rethinking leadership agility during transition. In: Agile leadership for industry 4.0. An indispensable approach for the digital era , 1st edn. Apple Academic Press

Naslund D, Kale R (2020) Is agile the latest management fad? A review of success factors of agile transformations. Int J Qual Serv Sci 12(4):489–504. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQSS-12-2019-0142

Oliveira SRM, Saraiva MA (2023) Leader skills interpreted in the lens of education 4.0. Procedia Comput Sci 217:1296–1304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2022.12.327

Orski K (2017) What’s your agility ability? Nurs Manage 48(4):44–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NUMA.0000511922.75269.6a

O’Brien E, Robertson P (2009) Future leadership competencies: from foresight to current practice. J Eur Ind Train 33(4):371–380. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090590910959317

O’Reilly CA, Tushman ML (2008) Ambidexterity as a dynamic capability: resolving the innovator’s dilemma. Res Organ Behavior 28:185–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2008.06.002

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S et al (2021) PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:160. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160

Paul J, Criado AR (2020) The art of writing literature review: What do we know and what do we need to know? Int Bus Rev 29(4):101717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2020.101717

Pesut DJ, Thompson SA (2018) Nursing leadership in academic nursing: The wisdom of development and the development of wisdom. J Prof Nurs 34(2):122–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2017.11.004

Piwowar-Sulej K, Sołtysik M, Różycka-Antkowiak JŁ (2022) Implementation of management 3.0: its consistency and conditional factors. J Organ Change Manage 35(3):541–557. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-07-2021-0203

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, Britten N, Roen K, Duffy S (2006) Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Lanc Univ https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.1018.4643

Psychogios A (2022) Re-conceptualising total quality leadership: a framework development and future research agenda. TQM J. https://doi.org/10.1108/TQM-01-2022-0030

Rigby D, Elk S, Steve B (2020) The agile C-suite a new approach to leadership for the team at the top. Harv Bus Rev

Roux M, Härtel CEJ (2018) The cognitive, emotional, and behavioral qualities required for leadership assessment and development in the new world of work. In: Petitta L, Härtel CEJ, Ashkanasy NM, Zerbe WJ (eds) Research on emotion in organizations, vol 14, pp 59–69. Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1746-979120180000014010

Rožman M, Oreški D, Tominc P (2023a) A multidimensional model of the new work environment in the digital age to increase a company’s performance and competitiveness. IEEE Access 11:26136–26151. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3257104

Rožman M, Tominc P, Štrukelj T (2023b) Competitiveness through development of strategic talent management and agile management ecosystems. Glob J Flex Syst Manage 24(3):373–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40171-023-00344-1

Şahin S, Alp F (2020) Agile leadership model in health care: Organizational and individual antecedents and outcomes. In: Akkaya B (ed) Agile business leadership methods for industry 4.0. Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 47–68

Sampson CJ (2023) How agile leadership can sustain innovation in healthcare. Front Health Serv Manage 40(2):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/HAP.0000000000000186

Saputra N (2023) Digital quotient as mediator in the link of leadership agility to employee engagement of digital generation. In: 2023 8th International conference on business and industrial research (ICBIR), pp 706–710. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICBIR57571.2023.10147472

Sharifi H, Zhang Z (1999) Methodology for achieving agility in manufacturing organisations: an introduction. Int J Prod Econ 62(1):7–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-5273(98)00217-5

Sheffield R, Jensen KR, Kaudela-Baum S (2023) Inspiring and enabling innovation leadership: key findings and future directions. In: K. R. Jensen, S. Kaudela-Baum, R. Sheffield (eds) Innovation leadership in practice: how leaders turn ideas into value in a changing world. Emerald Publishing Limited, pp 367–381. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-83753-396-120231019

Silva-Martinez J (2023) Conceptualization of agile leadership characteristics and outcomes from NASA agile teams as a path to the development of an agile leadership theory. J Creat Value, 23949643231202894. https://doi.org/10.1177/23949643231202894

Spiegler SV, Heinecke C, Wagner S (2021) An empirical study on changing leadership in agile teams. Abstr Empirical Softw Eng 26(3). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10664-021-09949-5

Teece D, Peteraf M, Leih S (2016) Dynamic capabilities and organizational agility: Risk, uncertainty, and strategy in the innovation economy. Calif Manage Rev 58(4):13–35. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2016.58.4.13

The Center for Creative Leadership (2015) What you need, and don’t have, when it comes to leadership talent. Center for Creative Leadership

The World Bank (2022) As global growth slows, developing economies face risk of ‘Hard Landing’. The World Bank . The World Bank

Theobald S, Prenner N, Krieg A, Schneider K (2020) Agile leadership and agile management on organizational level—a systematic literature review. In: Lecture notes in computer science (including subseries lecture notes in artificial intelligence and lecture notes in bioinformatics), 12562 LNCS, pp 20–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64148-1_2

Turan HY, Cinnioğlu H (2022) Agile leadership and employee performance in VUCA world. In: Akkaya B, Guah MW, Jermsittiparsert K, Bulinska-Stangrecka H, Kaya Y (eds) Agile management and VUCA-RR: opportunities and threats in industry 4.0 towards society 5.0. Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 27–38

Ulrich D, Yeung A (2019) Agility: the new response to dynamic change. Strateg HR Rev 18(4):161–167. https://doi.org/10.1108/SHR-04-2019-0032

Vaszkun B, Sziráki É (2023) Unlocking the key dimensions of organizational agility: a systematic literature review on leadership, structural and cultural antecedents. Soc Econ 45(4):393–410. https://doi.org/10.1556/204.2023.00023

Walter A-T (2021) Organizational agility: ill-defined and somewhat confusing? A systematic literature review and conceptualization. Manage Rev Q 71(2):343–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-020-00186-6

Warner KSR, Wäger M (2019) Building dynamic capabilities for digital transformation: an ongoing process of strategic renewal. Long Range Plan 52(3):326–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2018.12.001

Weiss L, Vergin L, Kanbach DK (2023) How agile leaders promote continuous innovation: an explorative framework. In: K. R. Jensen, S. Kaudela-Baum, R. Sheffield (eds) Innovation leadership in practice: How leaders turn ideas into value in a changing world. Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 223–242. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-83753-396-120231012

Zitkiene R, Deksnys M (2018) Organizational agility conceptual model. Monten J Econ 14(2):115–129. https://doi.org/10.14254/1800-5845/2018.14-2.7

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Research Ethics and Review Board (RERB) at O.P. Jindal Global University for their review and approval on our research study.

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Jindal Institute of Behavioural Sciences, O.P. Jindal Global University, Haryana, India

Latika Tandon & Tithi Bhatnagar

National Institute of Advanced Studies (NIAS), Bangalore, India

Tithi Bhatnagar

Jindal Global Business School, and Executive Director-Centre for Learning and Innovative Pedagogy (CLIP), O.P. Jindal Global University, Haryana, India

Tanushree Sharma

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by first author. The first draft of the manuscript was written by first author and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Latika Tandon .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

See the Table 6 , 7 and 8 .

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Tandon, L., Bhatnagar, T. & Sharma, T. Leadership agility in the context of organisational agility: a systematic literature review. Manag Rev Q (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-024-00422-3

Download citation

Received : 15 June 2022

Accepted : 12 March 2024

Published : 17 April 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-024-00422-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Leadership agility

- Agile leaders

- Agile leadership

- Organisational agility

- Leadership agility mindset

- Leadership agility competencies

- Leadership agility functions

JEL Classification

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

6 Common Leadership Styles — and How to Decide Which to Use When

- Rebecca Knight

Being a great leader means recognizing that different circumstances call for different approaches.

Research suggests that the most effective leaders adapt their style to different circumstances — be it a change in setting, a shift in organizational dynamics, or a turn in the business cycle. But what if you feel like you’re not equipped to take on a new and different leadership style — let alone more than one? In this article, the author outlines the six leadership styles Daniel Goleman first introduced in his 2000 HBR article, “Leadership That Gets Results,” and explains when to use each one. The good news is that personality is not destiny. Even if you’re naturally introverted or you tend to be driven by data and analysis rather than emotion, you can still learn how to adapt different leadership styles to organize, motivate, and direct your team.

Much has been written about common leadership styles and how to identify the right style for you, whether it’s transactional or transformational, bureaucratic or laissez-faire. But according to Daniel Goleman, a psychologist best known for his work on emotional intelligence, “Being a great leader means recognizing that different circumstances may call for different approaches.”

- RK Rebecca Knight is a journalist who writes about all things related to the changing nature of careers and the workplace. Her essays and reported stories have been featured in The Boston Globe, Business Insider, The New York Times, BBC, and The Christian Science Monitor. She was shortlisted as a Reuters Institute Fellow at Oxford University in 2023. Earlier in her career, she spent a decade as an editor and reporter at the Financial Times in New York, London, and Boston.

Partner Center

Leadership Research Paper

This sample leadership research paper features: 7900 words (approx. 26 pages), an outline, and a bibliography with 38 sources. Browse other research paper examples for more inspiration. If you need a thorough research paper written according to all the academic standards, you can always turn to our experienced writers for help. This is how your paper can get an A! Feel free to contact our writing service for professional assistance. We offer high-quality assignments for reasonable rates.

I. Introduction

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

II. Leadership Defined

III. The Trait Approach to Leadership

IV. What Do Leaders Do? The Behavioral Approach

V. Situational Approaches to Leadership

VI. Contingency Theories of Leadership

VII. Leader-Member Exchange Theory

VIII. Charismatic and Transformational Leadership

IX. Leader Emergence and Transition

X. Leadership Development

XI. Summary

XII. Bibliography

More Leadership Research Papers:

- Implicit Leadership Theories Research Paper

- Judicial Leadership Research Paper

- Leadership Styles Research Paper

- Police Leadership Research Paper

- Political Leadership Research Paper

- Remote Leadership Research Paper

Introduction

There are few things more important to human activity than leadership. Most people, regardless of their occupation, education, political or religious beliefs, or cultural orientation, recognize that leadership is a real and vastly consequential phenomenon. Political candidates proclaim it, pundits discuss it, companies value it, and military organizations depend on it. The French diplomat Talleyrand once said, “I am more afraid of an army of 100 sheep led by a lion than an army of 100 lions led by a sheep.” Effective leadership guides nations in times of peril, promotes effective team and group performance, makes organizations successful, and, in the form of parenting, nurtures the next generation. Winston Churchill, the Prime Minister of Great Britain during World War II, was able to galvanize the resolve of his embattled people with these words: “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears, and sweat.” When leadership is missing, the effects can be equally dramatic; organizations move too slowly, stagnate, and often lose their way. The League of Nations, created after the World War I, failed to meet the challenges of the times in large part because of a failure to secure effective leadership. With regard to bad leaders, Kellerman (2004) makes an important distinction between incompetent leaders and corrupt leaders. To this we might also add leaders who are “toxic.” Bad leadership can perpetuate misery on those who are subject to its domain. Consider the case of Jim Jones, the leader of the Peoples Temple, who in 1978 ordered the mass suicide of his 900 followers in what has been called the Jonestown Massacre, or the corrupt leadership of Enron and Arthur Anderson that impoverished thousands of workers and led to the dissolution of a major organization. These examples remind us that there are many ways in which leadership can fail.

Leadership Defined

When you think of leadership, the ideas of power, authority, and influence may come to mind. You may think of the actions of effective leaders in accomplishing important goals. You may think of actual people who have been recognized for their leadership capabilities. Dwight D. Eisenhower, 34th president of the United States, defined leadership as “the ability to decide what is to be done, and then to get others to want to do it.” Leadership can be defined as the ability of an individual to influence the thoughts, attitudes, and behavior of others. It is the process by which others are motivated to contribute to the success of the groups of which they are members. Leaders set a direction for their followers and help them to focus their energies on achieving their goals. Theorists have developed many different theories about leadership, and although none of the theories completely explains everything about leadership, each has received some scientific support. Some of the theories are based on the idea that there are “born leaders” with particular traits that contribute to their ability to lead. Other theories suggest that leadership consists of specific skills and behaviors. Some theories take a contingency approach that suggests that a leader’s effectiveness depends on the situation requiring leadership. Still other theories examine the relationship between the leader and his or her followers as the key to understanding leadership. In this research paper, we examine these various theories and describe the process of leadership development.

The Trait Approach to Leadership

Aristotle suggested that “men are marked out from the moment of birth to rule or be ruled,” an idea that evolved into the Great Person Theory. Great leaders of the past do seem different from ordinary human beings. When we consider the lives of Gandhi or Martin Luther King, Jr., it is easy to think of their influence as a function of unique personal attributes. This trait approach was one of the first perspectives applied to the study of leadership and for many years dominated leadership research. The list of traits associated with effective leadership is extensive and includes personality characteristics such as being outgoing, assertive, and conscientious. Other traits that have been identified are confidence, integrity, discipline, courage, self-sufficiency, humor, and mystery. Charles de Gaulle described this last trait best when he noted that “A true leader always keeps an element of surprise up his sleeve, which others cannot grasp but which keeps his public excited and breathless.”

Another trait often attributed to effective leaders is intelligence. However, intelligence is a two-edged sword. Although highly intelligent people may be effective leaders, their followers may feel that large differences in intellectual abilities mean large differences in attitudes, values, and interests. Thus, Gibb (1969) has pointed out that many groups prefer to be “ill-governed by people [they] can understand” (p. 218). One important aspect of intelligence that does predict leader effectiveness is emotional intelligence, which includes not only social skills but strong self-monitoring skills, which provide the leader with feedback as to how followers feel about the leader’s actions.

Finally, personal characteristics such as attractiveness, height, and poise are associated with effective leadership. After decades of research, in which the list of traits grew dramatically, researchers realized that the same person could be effective in one context (Winston Churchill as war leader) but ineffective in another context (Winston Churchill, who was removed from office immediately after the war was over). The failure of this approach to recognize the importance of the situation in providing clear distinctions between leaders and followers with regard to their traits caused many scientists to turn their attention elsewhere. However, theorists using more sophisticated methodological and conceptual approaches have revived this approach. Zaccaro (2007) suggests that the revival of the trait approach reflects a shift away from the idea that traits are inherited, as suggested in Galton’s 1869 book Hereditary Genius, and focuses on personal characteristics that reflect a range of acquired individual differences. This approach has three components. First, researchers do not consider traits as separate and distinct contributors to leadership effectiveness but rather as a constellation of characteristics that, taken together, make a good leader.

The second component broadens the concept of trait to refer not only to personality characteristics but also to motives, values, social and problem-solving skills, cognitive abilities, and expertise. For example, in a series of classic studies, McClelland and his colleagues (see McClelland & Boyatzis, 1982) identified three motives that contribute to leadership. They are the need for achievement, the need for power, and the need for affiliation. In their work, leader traits are not attributes of the person but the basis for the leader’s behavior. The need for achievement is manifested in the desire to solve problems and accomplish tasks. In the words of Donald McGannon, “Leadership is action, not position.” The need for power is evident in the desire to influence others without using coercion. As Hubert H. Humphrey once said, “Leadership in today’s world requires far more than a large stock of gunboats and a hard fist at the conference table.” The final motive, need for affiliation, can be a detriment to effective leadership if the leader becomes too concerned with being liked. However, it can provide positive results from the satisfaction a leader derives in helping others succeed. Lao Tse once wrote, “A good leader is a catalyst, and though things would not get done well if he weren’t there, when they succeed he takes no credit. And because he takes no credit, credit never leaves him.”

The third component of this new approach focuses on attributes that both are enduring and occur across a variety of situations. For example, there is strong empirical support for the trait approach when traits are organized according to the five-factor model of personality. Both extraversion and conscientiousness are highly correlated with leader success and, to a lesser extent, so are openness to experience and the lack of neuroticism.

What Do Leaders Do? The Behavioral Approach

Three major schools of thought—the Ohio State Studies, Theory X/Y (McGregor, 1960), and the Managerial Grid (Blake & Mouton, 1984)—have all suggested that differences in leader effectiveness are directly related to the degree to which the leader is task oriented versus person oriented. Task-oriented leaders focus on the group’s work and its goals. They define and structure the roles of their subordinates in order to best obtain organizational goals. Task-oriented leaders set standards and objectives, define responsibilities, evaluate employees, and monitor compliance with their directives. In the Ohio State studies this was referred to as initiating structure, whereas McGregor (1960) refers to it as Theory X, and the Managerial Grid calls it task-centered. Harry S. Truman, 33rd president of the United States, once wrote, “A leader is a man who can persuade people to do what they don’t want to do, or do what they’re too lazy to do, and like it.” Task-oriented leaders often see their followers as undisciplined, lazy, extrinsically motivated, and irresponsible. For these leaders, leadership consists of giving direction, setting goals, and making unilateral decisions. When under pressure, task-oriented leaders become anxious, defensive, and domineering.

In contrast, person-oriented leaders tend to act in a warm and supportive manner, showing concern for the well-being of their followers. Person-oriented leaders boost morale, take steps to reduce conflict, establish rapport with group members, and provide encouragement for obtaining the group’s goals. The Ohio State studies referred to this as consideration, the Managerial Grid calls this country club leadership, and McGregor uses the term Theory Y. Person-oriented leaders see their followers as responsible, self-controlled, and intrinsically motivated. As a result, they are more likely to consult with others before making decisions, praise the accomplishment of their followers, and be less directive in their supervision. Under pressure, person-oriented leaders tend to withdraw socially.

Leadership effectiveness can be gauged in several ways: employee performance, turnover, and dissatisfaction. As you can see in Table 68.1, the most effective leaders are those who are both task and person oriented, whereas the least effective leaders are those who are neither task nor person oriented. A recent meta-analysis found that person-oriented leadership consistently improves group morale, motivation, and job satisfaction, whereas task-oriented leadership only sometimes improves group performance, depending on the types of groups and situations.

In thinking about what leaders do, it is important to distinguish between leadership and management. Warren Bennis (1989) stated, “To survive in the twenty-first century, we are going to need a new generation of leaders— leaders, not managers.” He points out that managers focus on “doing things right” whereas leaders focus on “doing the right things.” Table 68.2 provides a comparison of the characteristics that distinguish a leader from a manager. As you look at the list, it is clear that a person can be a leader without being a manager and be a manager without being a leader.

Situational Approaches to Leadership

The Great Person theory of leadership, represented by such theorists as Sigmund Freud, Thomas Carlyle, and Max Weber, suggests that from time to time, highly capable, talented, charismatic figures emerge, captivate a host of followers, and change history. In contrast to this, Hegel, Marx, and Durkheim suggest that there is a tide running in human affairs, defined by history or the economy, and that leaders are those who ride the tide. The idea of the tide leads us to the role of situational factors in leadership. For example, Perrow (1970) suggests that leadership effectiveness is dependent upon structural aspects of the organization. Longitudinal studies of organizational effectiveness provide support for this idea. For example, Pfeffer (1997) indicated that “If one cannot observe differences when leaders change, then what does it matter who occupies the positions or how they behave?” (p. 108). Vroom and Jago (2007) have identified three distinct roles that situational factors play in leadership effectiveness. First, organizational effectiveness is not strictly a result of good leadership practices. Situational factors beyond the control of the leader often affect the outcomes of any group effort. Whereas leaders, be they navy admirals or football coaches, receive credit or blame for the activities of their followers, success or failure is often the result of external forces: the actions of others, changing technologies, or environmental conditions. Second, situations shape how leaders act. Although much of the literature on leadership has focused on individual differences, social psychologists such as Phil Zimbardo, in his classic Stanford Prison Experiment, and Stanley Milgram, in his studies of obedience, have demonstrated how important the situation is in determining behavior. Third, situations influence the consequences of leader behavior. Although many popular books on leadership provide a checklist of activities in which the leader should engage, most of these lists disregard the impact of the situation. Vroom and Jago (2007) suggest that the importance of the situation is based on three factors: the limited power of many leaders, the fact that applicants for leadership positions go through a uniform screening process that reduces the extent to which they differ from one another, and whatever differences between them still exist will be overwhelmed by situational demands. If all of these factors are present, it is probably true that the individual differences between leaders will not significantly contribute to their effectiveness. Nevertheless, in most of the situations in which leaders find themselves, they are not that powerless and their effectiveness is mostly a result of matching their skills with the demands of the situation, which brings us to a discussion of contingency theories.

Contingency Theories of Leadership

One of the first psychologists to develop a contingency approach to leadership effectiveness was Fred Fiedler (1964, 1967), who believed that a leader’s style is a result of lifelong experiences that are not easy to change. With this in mind, he suggested that leaders need to understand what their style is and to manipulate the situation so that the two match. Like previous researchers, Fiedler’s idea of leadership style included task orientation and person orientation, although his approach for determining a leader’s orientation was unique. Fiedler developed the least-preferred coworker (LPC) scale. On this scale, individuals rate the person with whom they would least want to work on a variety of characteristics. Individuals who rate their LPC as uniformly negative are considered task oriented, whereas those who differentiate among the characteristics are person oriented. The second part of his contingency theory is the favorableness of the situation. Situational favorability is determined by three factors: the extent to which the task facing the group is structured, the legitimate power of the leader, and the relations between the leader and his subordinates. The relation between LPC scores and group performance is complex, as can be seen in Table 68.3. A meta-analysis conducted by Strube and Garcia (1981) found that task-oriented leaders function best in situations that are either favorable (clear task structure, solid position power, and good leader/member relations) or unfavorable (unclear task structure, weak position power, and poor leader/member relations). In contrast, person-oriented leaders function best in situations that are only moderately favorable, which is often based on the quality of leader-member relations.

Another theory that addresses the relation between leadership style and the situation is path-goal theory (House, 1971). In this theory, path refers to the leader’s behaviors that are most likely to help the group attain a desired outcome or goal. Thus, leaders must exhibit different behaviors to reach different goals, depending on the situation. Four different styles of behavior are described:

- Directive leadership. The leader sets standards of performance and provides guidelines and expectations to subordinates on how to achieve those standards.

- Supportive leadership. The leader expresses concern for the subordinates’ well-being and is supportive of them as individuals, not just as workers.

- Participative leadership. The leader solicits ideas and suggestions from subordinates and invites them to participate in decisions that directly affect them.

- Achievement-oriented leadership. The leader sets challenging goals and encourages subordinates to attain those goals.

According to path-goal theory, effective leaders need all four of these styles because each one produces different results. Which style to use depends on two types of situational factors: subordinate characteristics, including ability, locus of control, and authoritarianism; and environmental characteristics, including the nature of the task, work group, and authority system. According to House and Mitchell (1974), when style and situation are properly matched, there is greater job satisfaction and acceptance of the leader, as well as more effort toward obtaining desired goals. A meta-analysis by Indvik (1986) is generally supportive of the theory. Studies of seven organizations found that task-oriented approaches are effective in situations with low task structure, because they help subordinates cope with an ambiguous situation, and ineffective in situations with high task structure, because they appear to be micromanagement. Additional studies have found that supportive leadership is most effective when subordinates are working on stressful, frustrating, or dissatisfying tasks. Researchers found participative leadership to be most effective when subordinates were engaged in nonrepetitive, ego-involving tasks. Finally, achievement-oriented leadership was most effective when subordinates were engaged in ambiguous, nonrepetitive tasks. A clear implication of the theory is that leaders must diagnose the situation before adopting a particular leadership style.

A third contingency approach is the normative and descriptive model of leadership and decision making developed by Vroom and his colleagues (see Vroom & Jago, 2007). This approach examines the extent to which leaders should involve their subordinates in decision-making processes. To answer this question, the researchers developed a matrix that outlines the five decision processes that range from highly autocratic through consultative to highly participative (see Table 68.4). Which of these approaches is the best? The answer is none of them is uniformly preferred, and each process has different costs and benefits. For example, participative approaches are more likely to gain support and acceptance among subordinates for the leader’s ideas, whereas autocratic approaches are quick and efficient, but may cause resentment. The theory suggests that the best approach may be selected by answering several basic questions about the situation that relate to the quality and acceptance of a decision. Some examples of the type of questions that should be asked are “Do I have enough information to make a decision? How structured is the task? Must subordinates accept the decision to make it work?” By answering such questions and applying the specific rules shown in Table 68.5, a leader is able to eliminate approaches that are likely to fail and to choose the approach that seems most feasible from those remaining.

Leader-Member Exchange Theory

A growing number of researchers have found that subordinates may affect leaders as much as leaders affect subordinates. Yukl (1998) pointed out that when subordinates perform poorly, leaders tend to be more task oriented, but when subordinates perform well, leaders are more person oriented. Similarly, Miller, Butler, and Cosentino (2004) found that the effectiveness of followers conformed to the same rules as those Fiedler applied to leaders. It may be that the productivity of a group can have a greater impact on leadership style than leadership style does on the productivity of the group. This reciprocal relation has been formally recognized in the vertical dyad linkage approach (Dansereau, Graen, & Haga, 1975), now commonly referred to as leader-member exchange (LMX) theory (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). This theory describes how leaders maintain their influence by treating individual followers differently. Over time, leaders develop a special relationship with an inner circle of trusted lieutenants, assistants and advisors—the in-group. The members of the in-group are given high levels of responsibility, influence over decision making, and access to resources. Members of the in-group typically are those who are highly committed to the organization, work harder, show loyalty to the leader, and share more administrative duties. Their reward is greater access to the leader’s resources, including information, concern, and confidence. To maintain the exchange, leaders must be careful to nurture the relationship with the in-group, giving them sufficient power to satisfy their needs but not so much power that they become independent. The leader-member relationship generally follows three stages. The first stage is role taking. During this stage the leader assesses the members’ abilities and talents and offers them opportunities to demonstrate their capabilities and commitment. In this stage, both the leader and member discover how the other wants to be respected. The second stage is role making. In this stage, the leader and member take part in unstructured and informal negotiations in order to create a role for the member with a tacit promise of benefits and power in return for dedication and loyalty. In this stage, trust building is very important, and betrayal in any form can result in the member’s being relegated to the out-group. In this stage the leader and member explore relationship factors as well as work-related factors. At this stage, it is clear that perceived similarities between the leader and follower become important. For this reason, a leader may favor a member who is similar in sex, race, or outlook with assignment to the in-group, although research by Murphy and Ensher (1999) indicated that the perception of similarity is more important than actual demographic similarities. The final stage is routinization. In this phase the pattern established by the leader and member becomes established.

The quality of the leader-member relationship is dependent on several factors. It tends to be better when the challenge of the job is either extremely high or extremely low. Other factors that affect the quality of the relationship are the size of the group, availability of resources, and overall workload.

Charismatic and Transformational Leadership

In a speech given at the University of Maryland, Warren Bennis said, “[A] leader has to be able to change an organization that is dreamless, soulless and visionless…someone’s got to make a wake-up call. The first job of a leader is to define a vision for the organization.…Leadership is the capacity to translate vision into reality.” Effective leaders are able to project a vision, explaining to their subordinates the purpose, meaning, and significance of their efforts. As Napoleon once said, “Leaders are dealers in hope.” Although the idea of charismatic leadership goes back as far as biblical times (“Where there is no vision, the people perish”—Proverbs 29:18), its modern development can be attributed to the work of Robert House. House (1977) analyzed political and religious leaders and noted that charismatic leaders are those high in self-confidence and confidence in their subordinates, with high expectations, a clear vision of what can be accomplished, and a willingness to use personal examples. Their followers often identify with the leader and his or her mission, show unswerving loyalty toward and confidence in the leader, and derive a sense of self-esteem from their association with the leader. Charismatic leaders are usually quite articulate, with superior debating and persuasive skills. They also possess the technical expertise to understand what their followers must do. Charismatic leaders usually have high self-confidence, impression-management skills, social sensitivity, and empathy. Finally, they have the skills to promote attitudinal, behavioral, and emotional change in their followers. Those who follow charismatic leaders are often surprised at how much they are able to accomplish that extends beyond their own expectations. Research on charismatic leadership indicates that the impact of such leaders is greatest when the followers engage in high self-monitoring (observing their effect on others) and exhibit high levels of self-awareness. Charismatic leadership enhances followers’ cooperation and motivation.

It is important to recognize that charismatic leadership can have a dark side. We began this research paper with the example of Jim Jones, the charismatic religious leader who led his people to commit mass suicide. Howell and Avolio (1992) describe the difference between ethical and unethical charismatic leaders. According to their analysis, ethical leaders use their power to serve others, not for personal gain. They also promote a vision that aligns with their follower’s needs and aspirations rather than with their own personal vision. Ethical leaders stimulate followers to think independently and to question the leader’s views. They engage in open, two-way communication and are sensitive to their followers’ needs. Finally, ethical leaders rely on internal moral standards to satisfy organizational and societal interests, not their own self-interests.

In helping followers achieve their aspirations, Bernard Bass (1997) has noted that charismatic leadership is a component of a broader-based concept, that of transformational leadership. Bass believed that most leaders are transactional rather than transformational in that they approach their relationships with followers as a transaction, one in which they define expectations and offer rewards that will be forthcoming when those expectations are met. Transactional leaders use a contingent reward system, manage by exception, watch followers to catch them doing something wrong, and intervene only when standards are not met. Finally, transactional leaders tend to adopt a laissez-faire approach by avoiding the need to make hard decisions.

In contrast, transformational leadership goes beyond mutually satisfactory agreements about rewards and punishments to heighten followers’ motivation, confidence, and satisfaction by uniting them in the pursuit of shared, challenging goals. In the process of doing that, they change their followers’ beliefs, values, and needs. Bass and Avolio (1994) identified four components of transformational leadership. The first component is idealized influence (charisma). Leaders provide vision, a sense of mission, and their trust in their followers. Leaders take stands on difficult issues and urge their followers to follow suit. They emphasize the importance of purpose, commitment, and ethical decision making. The second component is inspirational motivation. Leaders communicate high expectations, express important purposes in easy-to-understand ways, talk optimistically and enthusiastically about the tasks facing the organization, and provide encouragement and meaning for what has to be done. They often use symbols to focus the efforts of their followers. The third component is intellectual stimulation. Leaders promote thoughtful, rational, and careful decision making. They stimulate others to discard outmoded assumptions and beliefs and to explore new perspectives and ways of doing things. The fourth component is individualized consideration. Leaders give their followers personal attention and treat each person individually. They listen attentively and consider the individual needs, abilities, and goals of their followers in their decisions. In order to enhance the development of their followers they advise, teach, and coach, as needed. Yukl (2002) offers the following guidelines for transformational leadership:

- Develop a clear and appealing vision.

- Create a strategy for attaining the vision.

- Articulate and promote the vision.

- Act confident and optimistic.

- Express confidence in followers.

- Use early success in achievable tasks to build confidence.

- Celebrate your followers’ successes.

- Use dramatic, symbolic actions to emphasize key values.

- Model the behaviors you want followers to adopt.

- Create or modify cultural forms as symbols, slogans, or ceremonies.

Perhaps Walter Lippman provided the best summary of transformational leadership. He wrote, “The final test of a leader is that he leaves behind him in other men the conviction and the will to carry on…” The genius of good leaders is to leave behind them a situation that common sense, without the grace of genius, can deal with successfully.

Leader Emergence and Transition

Who becomes the leader? The process by which someone becomes formally or informally, perceptually or behaviorally, and implicitly or explicitly recognized as a leader is leadership emergence. Scholars have debated this question for centuries and in this research paper, so far, we have offered several possible answers. The Great Person Theory suggests that some people are marked for greatness and dominate the times in which they live. Tolstoy’s zeitgeist theory suggests that leaders come to prominence because of the spirit of the times. Trait theories suggest leaders are selected based on their personal characteristics, whereas interactional approaches examine the joint effects of the situation and the leader’s behavior. Research suggests that leadership emergence is an orderly process that reflects a rational group process whereby the individual with the most skill or experience or intelligence or capabilities takes charge. Implicit leadership theories (Lord & Maher, 1991) provide a cognitive explanation for leadership emergence. According to these theories, each member of a group comes to the group with a set of expectations and beliefs about leaders and leadership. These cognitive structures are called implicit leadership theories or leader prototypes. Typically these prototypes include both task and relationship skills as well as an expectation that the leader will epitomize the core values of the group. Members use their implicit theories to sort people into either leaders or followers based on the extent to which others conform to their implicit theory of what a leader should be. These implicit theories also guide members in their evaluations of the leader’s effectiveness. Because these theories are implicit, they are rarely subjected to critical scrutiny. As a result, it is not uncommon for followers to demonstrate a bias toward those who fit the mold of a traditional leader: White, male, tall, and vocal, regardless of the qualifications of that individual to be the leader.

Transition, rotation, succession, change of command; all are words used to describe a central facet of organizational leadership—that leaders follow one another. Despite the frequent occurrence of leader successions in nearly all groups, especially in large stable organizations, relatively little research has addressed this phenomenon. An early review by Gibb (1969) reported on studies of leader emergence and succession mode. In particular, Gibb noted the importance of establishing leadership/followership through early, shared, significant experiences; he also stressed that an important aspect of the organizational climate for the new leader derives from the policies of the former leader, the consequence of which shape followers’ expectations, morale, and interpersonal relations. In general, studies have demonstrated that leadership succession causes turbulence and instability resulting in performance decrements in most organizations and thus constitutes a major challenge to organizations. Thus, the process of becoming the new leader is often an arduous, albeit rewarding, journey of learning and self-development. The trials involved in this rite of passage have serious consequences for both the individual and the organization. As organizations have become leaner and more dynamic, new leaders have described a transition that gets more difficult all the time. To make the transition less difficult, leaders might attend to the following suggestions adapted from the works of Betty Price, a management consultant. Some of these suggestions are particularly important for newly appointed leaders in establishing an effective leadership style early in their tenure as leader.

- New leaders should show passion for their group, its purpose, and its people in order to reassure followers that the new leader is there to make the group better, not to further his or her personal ambitions.

- New leaders should think more strategically than tactically. Look for the big picture and don’t become bogged down in implementation processes.

- New leaders should first learn to listen, and then provide leadership. Leaders should be compelling in their ability to help others embrace the values that drive the group’s success. To do this the new leader must listen intently and provide feedback that demonstrates that he or she has truly heard what others have said.

- New leaders should operate in a learning mode. As the new person on the block, the new leader may be unsure about the reputation of the preceding leader. He or she should honor the insights and knowledge of others, believing that one can learn from everyone. The new leader should engage people purposefully at all levels, knowing that the distance between the front line and senior leadership is often so great that one small piece of information may have tremendous impact.

- New leaders should take particular care in doing what’s right and telling the truth, even if it is painful. One of the first tasks of a new leader is building trust. In the face of uncertainties, being honest, direct, and truthful enables people to move forward with faith. It gives them hope.

- New leaders should encourage their people to take risks in order to achieve their goals, and be prepared to pick up the pieces if they fail. The leader’s role is to cushion the risk by providing support and encouragement, and knowing and drawing from his or her people’s best capabilities.

Leadership Development

Not everyone is born with “the right stuff” or finds himself or herself in just the right situation to demonstrate his or her capacity as a leader. However, anyone can improve his or her leadership skills. The process of training people to function effectively in a leadership role is known as leadership development and it is a multimillion-dollar business. Leadership development programs tend to be of two types: internal programs within an organization, designed to strengthen the organization, and external programs that take the form of seminars, workshops, conferences, and retreats.

Typical of external leadership development programs are the seminars offered by the American Management Association. Their training seminars are held annually in cities across the country and address both general leadership skills as well as strategic leadership. Among the seminars offered in the area of general leadership are critical thinking, storytelling, and team development in a variety of areas such as instructional technology or government. Seminars on strategic leadership address such topics as communication strategies, situational leadership, innovation, emotional intelligence, and coaching.

A second approach to leadership development is a technique known as grid training. The first step in grid training is a grid seminar during which members of an organization’s management team help others in their organization identify their management style as one of four management styles: impoverished management, task management, country-club management, and team management. The second step is training, which varies depending on the leader’s management style. The goal of the training is greater productivity, better decision making, increased morale, and focused culture change in the leader’s unique organizational environment. Grid training is directed toward six key areas: leadership development, team building, conflict resolution, customer service, mergers, and selling solutions.

Internal leadership development programs tend to focus on three major areas: the development of social interaction networks both between people within a given organization and between organizations that work with one another, the development of trusting relationships between leaders and followers, and the development of common values and a shared vision among leaders and followers. There are several techniques that promote these goals. One such technique is 360-degree feedback. This is a process whereby leaders may learn what peers, subordinates, and superiors think of their performance. This kind of feedback can be useful in identifying areas in need of improvement. The strength of the technique is that it provides differing perspectives across a variety of situations that help the leader to understand the perceptions of his or her actions. This practice has become very popular and is currently used by virtually all Fortune 500 companies. Like all forms of assessment, 360-degree feedback is only useful if the leader is willing and able to change his or her behavior as a result of the feedback. To ensure that leaders don’t summarily dismiss feedback that doesn’t suit them, many companies have arranged for face-to-face meetings between the leaders and those who have provided the feedback.

Another form of internal leadership development is networking. As a leadership development tool, networking is designed to reduce the isolation of leaders and help them better understand the organization in which they work. Networking is specifically designed to connect leaders with key personnel who can help them accomplish their everyday tasks. Networking promotes peer relationships and allows individuals with similar concerns and responsibilities to learn from one another ways to better do their job. Research indicates that these peer relationships tend to be long-lasting.

Executive coaching is a method for developing leaders that involves custom-tailored, one-on-one interactions. This method generally follows four steps. It begins with an agreement between the coach and the leader as to the nature of the coaching relationship, to include what is to be done and how it will be done. The second step is an expert’s assessment of the leader’s strengths and weaknesses. The third step provides a comprehensive plan for improvement that is usually shared with the leader’s immediate supervisor. The fourth and final step is the implementation of the plan. Coaching is sometimes a onetime event aimed at addressing a particular concern or it can be an ongoing, continuous process.

Another form of internal leadership development is mentoring. The term mentor can mean many things: a trusted counselor or guide, tutor, coach, master, experienced colleague, or role model. A mentor is usually someone older and more experienced who provides advice and support to a younger, less experienced person (protégé). In general, mentors guide, watch over, and encourage the progress of their protégés. Mentors often pave the way for their protégé’s success by providing opportunities for achievement, nominating them for promotion, and arranging for their recognition. As a form of leadership development, there are several advantages to mentoring. A meta-analysis by Allen, Eby, Poteet, Lima, and Lentz (2004) indicated that individuals who were mentored showed greater organizational commitment, lower turnover, higher career satisfaction, enhanced leadership skills, and a better understanding of their organization.

In the future, leadership is likely to become more group centered as organizations become more decentralized. Other changes will come about as a result of new and emerging technologies. Avolio and his colleagues (2003) refer to this as “e-leadership.” Leadership effectiveness will depend on the leader’s ability to integrate the new technologies into the norms and culture of their organization.

Another change is that the future will most likely see more women break through the “glass ceiling” and take leadership positions. Men are considerably more likely to enact leadership behaviors than are women in studies of leaderless groups, and as a result are more likely to emerge as leaders (Eagly, 1987). Even though women do sometimes emerge as leaders, historically they have been excluded from the highest levels of leadership in both politics and business. This exclusion has been called the glass ceiling. Studies of leadership in organizational settings have found that men and women do not differ significantly in their basic approach to leadership, with equal numbers of task- versus person-oriented leaders. However, women are much more likely to adopt a participative or transformational leadership style whereas men are more likely to be autocratic, laissez-faire, or transactional (Eagly & Johnson, 1990). Women’s leadership styles are more closely associated with group performance as well as subordinate satisfaction, and in time our implicit theories about leadership may very well favor those who adopt such approaches.

Diversity and working in a global economy will provide additional challenges to tomorrow’s leaders. Project GLOBE (Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness) is an extensive international project involving 170 researchers who have gathered data from 18,000 managers in 62 countries (House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorman, & Gupta, 2004). A major goal of the project was to develop societal and organizational measures of culture and leader attributes that were appropriate to use across all cultures. There have been several important findings. In some cultures, leadership is denigrated and regarded with suspicion. People in these cultures often fear that leaders will acquire and abuse power and as a result substantial restraints are placed on the exercise of leadership. Twenty-two leadership traits (e.g., foresight and decisiveness) were identified as being desirable across all cultures. Eight leadership traits (e.g., ruthlessness and irritability) were identified as being universally undesirable. Some leadership traits were dependent upon the culture, including ambition and elitism. Six leadership styles common to many cultures were identified. They are charismatic, self-protective, humane, team oriented, participative, and autonomous. Although the charismatic style is familiar to us, some of the others are not. The self-protective style involves following agreed-upon procedures, being cognizant of the status hierarchy, and saving face. The humane style includes modesty and helping others. The team-oriented style includes collaboration, team building, and diplomacy. The participative style encourages getting the opinions and help of others. The autonomous style involves being independent and making one’s own decisions. Cultures differ in their preferences for these styles. For example, leaders from northern European countries are more participative and less self-protective whereas leaders from southern Asia are more humane and less participative.

Although most of us would agree that leadership is extraordinarily important, research in this field has yet to arrive at a generally accepted definition of what leadership is, create a widely accepted paradigm for studying leadership, or find the best strategies for developing and practicing leadership. Hackman and Wageman (2007) attempted to address this problem by reframing the questions we have been asking about leadership effectiveness, with the hope that these questions will be more informative than many of those asked previously.

- Question 1. Ask NOT “Do leaders make a difference?” but “Under what conditions does leadership matter?” The task here is to examine conceptually and empirically the circumstances under which leadership makes a difference and to distinguish those from the circumstances for which leadership is inconsequential.

- Question 2. Ask NOT “What are the traits that define an effective leader?” but “How do leaders’ personal attributes interact with situational properties to shape outcomes?” This approach will require that we reduce our reliance on both fixed traits and complex contingencies. To do this, we should embrace the idea that there are many different ways to achieve the same outcome.

- Question 3. Ask NOT “Are there common dimensions on which all leaders can be arrayed?” but “Are good and poor leadership qualitatively different phenomena?” Recent research has found that ineffective leaders were not ones who scored low on those dimensions for which good leaders scored high, but rather they exhibited entirely different patterns of behavior than those exhibited by good leaders.

- Question 4. Ask NOT “How do leaders and followers differ from one another?” but “How can leadership models be reframed so they treat all members of a group as leaders and followers?” Although it is clear that to be a leader requires that you have followers, it is equally true that most leaders are at times followers and most followers are at times leaders.

- Question 5. Ask NOT “What should be taught in leadership courses?” but “How can leaders be helped to learn?” Research is needed to understand how leaders learn from their experiences, especially when they are coping with crises (see Avolio, 2007).

In the 21st century, the study of leadership will be increasingly collaborative as researchers from multiple disciplines tackle the questions outlined above. Some of the disciplines that must contribute to the study of leadership include media and communications. In today’s world more and more of the relationships between leaders and followers are not face-to-face but mediated through electronic means.

John Kenneth Galbraith, in his book The Age of Uncertainty, wrote that “All of the great leaders have had one characteristic in common: it was the willingness to confront unequivocally the major anxiety of their people in their time. This, and not much else, is the essence of leadership.” In the special issue of the American Psychologist devoted to leadership, Warren Bennis (2007) suggests that the four most important threats facing our world today are these: (a) a nuclear or biological catastrophe; (b) a worldwide pandemic; (c) tribalism and its cruel offspring, assimilation; and (d) leadership of our human institutions. He points out that solving the first three problems will not be possible without exemplary leadership and that an understanding of how to develop such leadership will have serious consequences for the quality of our health and our lives.

Bibliography:

- Allen, T. D., Eby, L. T., Poteet, M., Lima, L., & Lentz, E. (2004). Outcomes associated with mentoring protégés: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 127–136.

- Avolio, B. J. (2007). Promoting more integrative strategies for leadership theory building. American Psychologist, 62, 25–33.

- Avolio, B. J., Sosik, J. J., Jung, D. I., & Bierson, Y. (2003). Leadership models, methods, and applications. In W. C. Borman, D. R. Ilgen, & R. J. Klimoski (Eds.), Handbook of psychology: Vol. 12. Industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 277–307). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Bass, B. M. (1990). Bass and Stogdill’s handbook of leadership: A survey of theory and research. New York: Free Press.

- Bass, B. M. (1997). Does the transactional-transformational leadership paradigm transcend organizational and national boundaries? American Psychologist, 52, 130–139.

- Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1994). Improving organizational effectiveness through transformational leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Bennis, W. (1989). On becoming a leader. New York: Perseus.

- Bennis, W. (2007). The challenges of leadership in the modern world: Introduction to the special issue. American Psychologist, 62, 2–5.

- Blake, R. R., & Mouton, J. S. (1984). Solving costly organizational conflicts: Achieving intergroup trust, cooperation, and teamwork. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Dansereau, F., Graen, G. G., & Haga, W. (1975). A vertical dyad linkage approach to leadership in formal organizations. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 13, 46–78.

- Eagly, A. H. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior: A social role interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Eagly, A., & Johnson, B. (1990). Gender and the emergence of leaders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 233–256.

- Fiedler, F. E. (1964). A contingency model of leadership effectiveness. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 1). New York: Academic Press.

- Fiedler, F. E. (1967). A theory of leadership effectiveness. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Gibb, C. A. (1969). Leadership. In G. Lindzey & E. Aronson (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (2nd ed., Vol. 4, pp. 205–282). Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219–247.