- Lesson Plans

- Teacher's Guides

- Media Resources

Lesson 2: The Spanish–American War

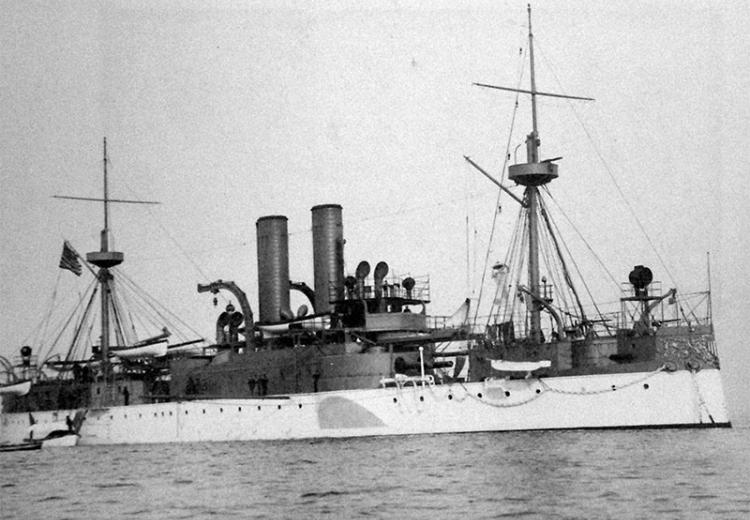

Battleship U.S.S. Maine, at anchor. The explosion in Havana harbor that sank the Maine helped precipitate the Spanish-American War.

Wikimedia Commons

On April 11, 1898, two months after the battleship U.S.S. Maine was destroyed by an explosion in Havana harbor, President McKinley sent a message to Congress requesting authority to use the U.S. armed forces to end a brutal civil war in the Spanish colony of Cuba. Congress voted to support Cuban independence, to demand the withdrawal of Spanish troops from the island, and to authorize the use of force to achieve those objectives. On April 25, after Spain broke diplomatic relations and declared war against the United States, Congress formally asserted that a state of war existed. In a whirlwind military campaign, the U.S. Army invaded Cuba and the U.S. Navy destroyed Spanish squadrons in the Caribbean and Manila Bay. Hostilities were halted on August 12, 1898. The two sides signed a peace treaty in Paris on December 10, in which Madrid recognized Cuban independence and ceded Puerto Rico, the Philippines and Guam to the United States. With its victory in the Spanish-American War the United States claimed status as a global power – and, in a relative absence of mind, it acquired something of an overseas empire.

This lesson plan, through the use of primary sources and a WebQuest Interactive , will focus on the causes of the war and the political debate in the United States over the advisability of intervening militarily in the affairs of countries.

Guiding Questions

Was the Spanish-American War a fundamental shift in American foreign policy?

What did the Spanish-American War mean for the role of the press in American politics and society?

Learning Objectives

Examine the causes of the Spanish-American War and evaluate the effects of the war on domestic and foreign policy.

Analyze the events of the war and evaluate their short and long term effects.

Evaluate the connections between the war and the larger political debate over American imperialism.

Lesson Plan Details

Americans had long been interested in the Spanish colony of Cuba, one of the last remnants of Spain’s once-great American empire. The island commanded critical maritime lines of communication into the Gulf of Mexico. Thomas Jefferson and John Quincy Adams thought that the island’s geographic position made it a natural part of a North American confederation. American businessmen held substantial investments on the island. During a major popular insurrection against Spanish rule (the Ten Years War, 1868 – 78), the American public generally sympathized with the rebels, but the U.S. government chose not to intervene directly.

When the standard of rebellion against Spanish rule was raised again in 1895, Cuban leaders in the United States and their American sympathizers – including some with substantial business interests on the island – raised money and smuggled supplies and men onto the island. Many Cuban leaders, including the famous New York-based writer José Martí (who died in a skirmish in 1895), admired much about the United States but were suspicious of American intentions. A new Spanish commander, General Valeriano Weyler, waged a counterinsurgency campaign that brought the civilian population into concentration camps. Those in the camps suffered greatly from poor sanitation and lack of food and medicine. Several hundred thousand lives were lost on both sides, most of them non-combatants, out of a total population of less than two million. American citizens and property on the island were often caught in the middle of the violence.

The humanitarian disaster in Cuba caught the attention of the popular press in the United States. These “yellow journalists” – especially two competing New York newspapers (William Randolph Hearst’s Journal and Joseph Pulitzer’s World ) – sensationalized the atrocities of “Butcher” Weyler and urged American intervention. Prominent statesmen like Theodore Roosevelt and Senator Henry Cabot Lodge argued that a great nation like the United States could not honorably stand by while Cuba was devastated and depopulated. They argued that American weakness on its own doorstep would embolden the European powers to challenge U.S. hemispheric interests and global aspirations. These war hawks, following the geopolitical arguments made popular by Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan, stressed the strategic importance of Cuba.

Through early 1898, however, those who opposed American military intervention in Cuba held the upper hand. The devastation caused by the Civil War was still within living memory. White southerners in general feared that war over Cuba would be fought in the interests of the industrial north and lead to a stronger federal government. Many Americans, not just southerners, regarded the African-Hispanic peoples of Cuba through the prism of race as an “inferior” people, not worth fighting about. Businessmen who did not have a major stake in Cuba were concerned that war would destabilize precarious financial markets. The anti-interventionists pointed to serious human rights abuses by the insurrectos and argued that security and honor for the United States meant staying out the quarrels of others.

President Grover Cleveland, a Democrat, was in office when the insurrection first broke out. He was decidedly in the anti-interventionist camp. Cleveland sought to protect American citizens and property while encouraging a peaceful settlement of the conflict. Republican President William McKinley, who assumed office in March 1897, likewise sought a diplomatic solution in which Spain would grant substantial autonomy to Cuba. McKinley also explored the possibility of purchasing the island from Spain. The government in Madrid did not feel it could make such concessions, however, in light of strong domestic opposition to surrendering the last vestiges of the Spanish empire. Spain offered only limited reforms and recalled General Weyler. The Cuban insurrectos , who wanted complete independence from Spain (and from the United States), also rejected compromise. Moderate Republicans and some key Democratic leaders, including William Jennings Bryan, called for intervention on humanitarian grounds. The press published an inflammatory private letter, written by the Spanish Minister to the United States, Enrique Dupuy de Lôme, which disparaged McKinley. On February 15, 1898, the battleship Maine exploded while on a “courtesy visit” to Havana harbor. The official U.S. investigation concluded that the ship had been destroyed by a submarine mine of unknown origin. The obvious inference was that Spain was responsible.

Historians disagree whether McKinley reluctantly now followed an enraged American public into war or whether he actively shaped that opinion. The President insisted on Spanish acceptance of U.S. arbitration. He declined the offers of European powers, led by Germany and France, to mediate the dispute. His Congressional supporters carefully orchestrated a joint resolution that supported Cuban independence and authorized the use of force. To promote cooperation with the Cuban insurrectos and reassure European powers of U.S. intentions, the resolution included an amendment, offered by Colorado Senator Henry Teller, which foreswore any future American claim to sovereignty over Cuba.

McKinley did not fully embrace the Roosevelt-Mahan strategic view, but he did believe that the United States must assume a leading role in global affairs and preserve opportunities for American commerce. The Spanish – American War was fought with these larger goals in mind. The U.S. Army, which invaded Cuba in early June, was far from ready to fight; its weaknesses became painfully clear over the next few months despite successes such as the famous charge of Roosevelt’s Rough Riders. But McKinley and his advisers decided that the war would be won primarily at sea. The newly-modernized U.S. Navy defeated Spanish squadrons in the Caribbean and at Manila Bay in the Philippines, thereby controlling access to Spain’s vulnerable overseas possessions. U.S. forces occupied Guam and Puerto Rico and supported a nationalist uprising in the Philippines. Within three months, the Spanish government sued for peace. Hostilities were halted on August 12, 1898. The two sides signed a peace treaty in Paris on December 10. With its victory in the Spanish – American War the United States claimed status as a global political-military power. Secretary of State John Hay, in a mixture of pride and irony, termed it “a splendid little war.” Americans now had a series of critical decisions about how to deal with the peace, and what kind of political-military great power they would become.

NCSS.D1.2.9-12. Explain points of agreement and disagreement experts have about interpretations and applications of disciplinary concepts and ideas associated with a compelling question.

NCSS.D2.His.1.9-12. Evaluate how historical events and developments were shaped by unique circumstances of time and place as well as broader historical contexts.

NCSS.D2.His.2.9-12. Analyze change and continuity in historical eras.

NCSS.D2.His.3.9-12. Use questions generated about individuals and groups to assess how the significance of their actions changes over time and is shaped by the historical context.

NCSS.D2.His.4.9-12. Analyze complex and interacting factors that influenced the perspectives of people during different historical eras.

NCSS.D2.His.5.9-12. Analyze how historical contexts shaped and continue to shape people’s perspectives.

NCSS.D2.His.12.9-12. Use questions generated about multiple historical sources to pursue further inquiry and investigate additional sources.

NCSS.D2.His.14.9-12. Analyze multiple and complex causes and effects of events in the past.

NCSS.D2.His.15.9-12. Distinguish between long-term causes and triggering events in developing a historical argument.

NCSS.D2.His.16.9-12. Integrate evidence from multiple relevant historical sources and interpretations into a reasoned argument about the past.

Review the lesson plan. Locate and bookmark suggested materials and links from EDSITEment reviewed websites used in this lesson. Download and print out selected documents and duplicate copies as necessary for student viewing. Alternatively, excerpted versions of these documents are available as part of the downloadable PDF.

Download the Text Document for this lesson, ( available here as a PDF Document ). This file contains excerpted versions of the documents used in the various activities, as well as questions for students to answer. Print out and make an appropriate number of copies of the handouts you plan to use in class.

Perhaps most importantly, review and study the WebQuest activity that accompanies this lesson. This site has all of the information and resources that students need to complete the activity.

In addition, if your students need assistance with primary source documents, the following EDSITEment-reviewed websites may be useful:

- The Learning Page at the American Memory Project of the Library of Congress

- National Archives, Teaching with Documents

Activity 1: The Splendid Little War

During months of conflict between the Spanish Army and irregular native forces in Cuba, the United States government attempted to broker a diplomatic solution that would avoid the need for American military intervention and end the humanitarian disaster on the island. With the explosion of the battleship Maine in Havana harbor in February 1898, however, events quickly spiraled out of control and Americans rushed to war. In this activity, students will use an interactive WebQuest in which they create a magazine about the Spanish-American War.

To begin, hand out the following document, located in its excerpted form on pages 1-2 of the Text Document that accompanies this lesson:

- Grover Cleveland on Cuba, 1896

Discuss with students the ideas/beliefs raised by Grover Cleveland about American interests in Cuba and the reasons for the United States to be cautious about intervention. Make a list of these reasons on the board.

Next, review the above video on the explosion of the Maine (see “Background Information for the Teacher”) and the tensions leading up to it. Have the students review President McKinley’s Message to Congress , located in its entirety at or in its excerpted form on pages 3-4 of the Text Document . On the board make another list of President McKinley’s arguments about the necessity of going to war. How do his arguments differ from those of President Cleveland? What has changed?

Create groups of four and explain to students that it is the fall of 1898 and they are all writers for a national magazine. Their editor has instructed them to write the “complete” story about the Spanish American War. In order to make this the complete story, each group member will be writing articles from one of the following roles:

Coming of War

Battles of the war, opposition to the war, photographer.

Next, direct students to the interactive WebQuest . Everything for the assignment, including specific instructions for each part and all of the resources, has been placed on the WebQuest. Review the directions and activity with the students, paying particular attention to the requirements of the project, which vary depending on the role assigned. Encourage students to only use the resources on the WebQuest, as they have been selected to aid them in focusing in on their research topic. Below are the requirements for each of the roles.

It is your job to report on the issues/events leading up to the war.

- What events occurred to lead to the actual war?

- What were people in America thinking?

- How did "Yellow Journalism" affect public opinion?

- What finally pushed us into war?

In doing this, you must adhere to the following requirements:

- Your article must be at least two typed pages.

- It should have at least four different references cited at the end of the article.

- You should use three quotes from people from that time period.

It is your job to report on the specific battles of the war.

- What went wrong, what went right?

- What were the key land/naval battles?

- Why did America win the war?

It is your job to your job is to report on the opposition to the War.

- What did those opposed to the war do?

- What did they think?

- How organized was this resistance?

Many photographs of the Spanish American war have been published. Using these pictures, make a visual display of the war.

- Your article must be at least 4 pages.

- Each picture should have your own written caption.

- Include at least four different references (websites) at the end of your article to show where you obtained your pictures.

Inform the group members that they will combine their individual contributions to create one complete magazine.

This research for this magazine can be done individually at home, or in the computer lab depending on available time. Once students have completed their research, they are to create a magazine in which all of these articles are presented. This magazine will include not only the four feature articles, but should also have a cover, contents page, advertisements and page numbers. Remind students that it is to look like a real magazine. Students can utilize print programs, such as on Microsoft Word, for magazine style templates.

Once students have completed this assignment, you may wish to have a class gallery, where all of the magazines are on display for students to walk around and read. If time permits, students could peer evaluate their classmates for an additional grade.

To conclude, discuss the Spanish American War with the students. Does it deserve the title “A Splendid Little War?”

The magazine from the WebQuest should be graded as a formal assessment.

Students should be able to identify and/or define the following:

- Theodore Roosevelt

- Imperialism

- Yellow Journalism

- General Weyler

In addition, students should be able to locate the following on a map

- Philippines

- Puerto Rico

Finally, students should be able to write a brief essay (3 – 4 paragraphs) answering the following:

- How did the Spanish American War change the course of American foreign policy?

PBS has developed a useful documentary on the Spanish American War entitled, “ Crucible of Empire: The Spanish – American War .” If time permits, teachers might show this to their students. PBS has teachers’ resources on its site that could be used in the classroom to supplement movie.

Selected EDSITEment Resources

- Page of International Politics, Mt. Holyoke College

- Grover Cleveland: American Interests in the Cuban Revolution

- President McKinley, Declaration of War, 1898

- Crucible of Empire

- Blank map of the World

Materials & Media

The spanish–american war: worksheet 1, related on edsitement, the spanish–american war, lesson 1: the question of an american empire, lesson 3: the matter of the philippines, lesson 4: imperialism and the open door.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Spanish American War

By: History.com Editors

Updated: May 2, 2022 | Original: May 14, 2010

The Spanish-American War was an 1898 conflict between the United States and Spain that ended Spanish colonial rule in the Americas and resulted in U.S. acquisition of territories in the western Pacific and Latin America.

Causes: Remember the Maine!

The war originated in the Cuban struggle for independence from Spain, which began in February 1895.

Spain’s brutally repressive measures to halt the rebellion were graphically portrayed for the U.S. public by several sensational newspapers engaging in yellow journalism , and American sympathy for the Cuban rebels rose.

Did you know? The term yellow journalism was coined in the 19th century to describe journalism that relies on eye-catching headlines, exaggeration and sensationalism to increase sales.

The growing popular demand for U.S. intervention became an insistent chorus after the still-unexplained sinking in Havana harbor of the American battleship USS Maine , which had been sent to protect U.S. citizens and property after anti-Spanish rioting in Havana.

War Is Declared

Spain announced an armistice on April 9 and speeded up its new program to grant Cuba limited powers of self-government.

But the U.S. Congress soon afterward issued resolutions that declared Cuba’s right to independence, demanded the withdrawal of Spain’s armed forces from the island, and authorized the use of force by President William McKinley to secure that withdrawal while renouncing any U.S. design for annexing Cuba.

Spain declared war on the United States on April 24, followed by a U.S. declaration of war on the 25th, which was made retroactive to April 21.

Spanish American War Begins

The ensuing war was pathetically one-sided, since Spain had readied neither its army nor its navy for a distant war with the formidable power of the United States.

In the early morning hours of May 1, 1898, Commodore George Dewey led a U.S. naval squadron into Manila Bay in the Philippines. He destroyed the anchored Spanish fleet in two hours before pausing the Battle of Manila Bay to order his crew a second breakfast. In total, fewer than 10 American seamen were lost, while Spanish losses were estimated at over 370. Manila itself was occupied by U.S. troops by August.

The elusive Spanish Caribbean fleet under Adm. Pascual Cervera was located in Santiago harbor in Cuba by U.S. reconnaissance. An army of regular troops and volunteers under Gen. William Shafter (including then-former assistant secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt and his 1st Volunteer Cavalry, the “Rough Riders”) landed on the coast east of Santiago and slowly advanced on the city in an effort to force Cervera’s fleet out of the harbor.

Cervera led his squadron out of Santiago on July 3 and tried to escape westward along the coast. In the ensuing battle all of his ships came under heavy fire from U.S. guns and were beached in a burning or sinking condition.

Santiago surrendered to Shafter on July 17, thus effectively ending the brief but momentous war.

Treaty of Paris

The Treaty of Paris ending the Spanish American War was signed on December 10, 1898. In it, Spain renounced all claim to Cuba, ceded Guam and Puerto Rico to the United States and transferred sovereignty over the Philippines to the United States for $20 million.

Philippine insurgents who had fought against Spanish rule soon turned their guns against their new occupiers. The Philippine-American War began in February of 1899 and lasted until 1902. Ten times more U.S. troops died suppressing revolts in the Philippines than in defeating Spain.

Impact of the Spanish-American War

The Spanish American War was an important turning point in the history of both antagonists. Spain’s defeat decisively turned the nation’s attention away from its overseas colonial adventures and inward upon its domestic needs, a process that led to both a cultural and a literary renaissance and two decades of much-needed economic development in Spain.

The victorious United States, on the other hand, emerged from the war a world power with far-flung overseas possessions and a new stake in international politics that would soon lead it to play a determining role in the affairs of Europe and the rest of the globe.

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Teacher Opportunities

- AP U.S. Government Key Terms

- Bureaucracy & Regulation

- Campaigns & Elections

- Civil Rights & Civil Liberties

- Comparative Government

- Constitutional Foundation

- Criminal Law & Justice

- Economics & Financial Literacy

- English & Literature

- Environmental Policy & Land Use

- Executive Branch

- Federalism and State Issues

- Foreign Policy

- Gun Rights & Firearm Legislation

- Immigration

- Interest Groups & Lobbying

- Judicial Branch

- Legislative Branch

- Political Parties

- Science & Technology

- Social Services

- State History

- Supreme Court Cases

- U.S. History

- World History

Log-in to bookmark & organize content - it's free!

- Bell Ringers

- Lesson Plans

- Featured Resources

Bell Ringer: Spanish-American War

Description.

Stephan McAteer discusses the Spanish-American War, and the MacArthur Museum of Arkansas Military History exhibit, “Splendid Little War.”

Bell Ringer Assignment

- What did this war represent for people in the United States after the Civil War?

- Explain the significance of Cuba in this conflict.

- What was the role of journalism at this time?

- What part did jingoists play in this war?

- Explain the conflict between military minds during this time.

- What was the catalyst for the war?

- What did the United States gain as a result of the conflict?

Participants

- Colonial Empire

- Joseph Pulitzer

- President Mckinley

- Theodore Roosevelt

- William Randolph Hearst

- Yellow Journalism

Spanish-American War

The Spanish-American War lesson plan explores the events and reasoning that led to the Spanish-American War, the main events and people of the war, and the results and impact of the war across the world.

Included with this lesson are some adjustments or additions that you can make if you’d like, found in the “Options for Lesson” section of the Classroom Procedure page. One of the optional additions to this lesson is to assign a country (Spain, Philippines, Guam, Puerto Rico, or Cuba) to each student to research and present to the class.

Description

Additional information, what our spanish-american war lesson plan includes.

Lesson Objective and Overview: Spanish-American War explores the events and reasoning that led to the Spanish-American War, the main events and people of the war, and the results and impact of the war across the world. At the end of the lesson, students will be able to identify the reasons for the Spanish-American War, the main events and people of the war, and the results and impact of the war. This lesson is for students in 4th grade, 5th grade, and 6th grade.

Classroom Procedure

Every lesson plan provides you with a classroom procedure page that outlines a step-by-step guide to follow. You do not have to follow the guide exactly. The guide helps you organize the lesson and details when to hand out worksheets. It also lists information in the orange box that you might find useful. You will find the lesson objectives, state standards, and number of class sessions the lesson should take to complete in this area. In addition, it describes the supplies you will need as well as what and how you need to prepare beforehand.

Options for Lesson

Included with this lesson is an “Options for Lesson” section that lists a number of suggestions for activities to add to the lesson or substitutions for the ones already in the lesson. One optional addition to this lesson is to assign a country (Spain, Philippines, Guam, Puerto Rico, or Cuba) to each student to research and present to the class. You can also have your students draw detailed maps of their assigned country, identifying the capital and other large cities on the map. Finally, you can assign the homework assignment as in-class work instead.

Teacher Notes

The teacher notes page includes a paragraph with additional guidelines and things to think about as you begin to plan your lesson. This page also includes lines that you can use to add your own notes as you’re preparing for this lesson.

SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR LESSON PLAN CONTENT PAGES

The Spanish-American War lesson plan includes two content pages. The Spanish-American War, fought between Spain and America from April 25, 1898 to August 12, 1898, lasted just three and a half months. These countries fought this war mostly over Cuba’s independence. At this time, Cuba was one of Spain’s colonies, as were the Philippines. Cuban revolutionaries had been fighting for their independence for years. Lots of Americans favored Cuba’s independence. They wanted the U.S. to help the Cuban revolutionaries.

President William McKinley sent a battleship, the Maine , to protect the American citizens and the interests of the U.S. However, the ship sank in an explosion in the Havana Harbor on February 15, 1898. Many Americans suspected Spain’s involvement in the explosion and pressured McKinley to declare war against Spain. This was the beginning of the Spanish-American War on April 25, 1898.

The U.S. attacked Spanish battleships in the Philippines to try to stop them from traveling to Cuba. The Battle of Manilla took place on May 1st. The U.S. Navy beat the Spanish Navy easily and took control of the Philippines.

Rough Riders

During this war, a new type of volunteer soldier began: the Rough Riders. They were ranchers, cowboys, and outdoorsmen led by future U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt. They traveled on foot because they could not bring their horses to Cuba.

The U.S. fought the Spanish in the Battle of San Juan Hill. During this battle, a small Spanish force stopped the U.S. from advancing. They killed many U.S. troops. The U.S. gained back the advantage, however, when the Rough Riders appeared.

The final battle of this war was the Battle of Santiago. It took place in the city of Santiago, where U.S. soldiers took over the city and the U.S. Navy destroyed Spanish ships. The Spanish troops surrendered on July 17th.

The fighting stopped about a month later, on August 12th. Both sides signed a formal peace treaty, the Treaty of Paris, on December 19, 1898. This treaty gave Cuba its independence. Spain also gave up its control of the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico to the U.S. for $20 million.

Today, few historians believe that the Spanish caused the sinking of the battleship Maine . At that time, some U.S. newspapers reported incorrect facts to the citizens of the U.S., who then pressured the U.S. to go to war with Spain. We now call this kind of reporting, when facts are incomplete or changed, “Yellow Journalism”.

The Spanish-American War lasted only a few months but had a big impact on the United States, Cuba, Guam, the Philippine Islands, and Spain.

Here is a list of the vocabulary words students will learn in this lesson plan:

- Cuba: Former colony of Spain

- The Maine : The battleship sent by President McKinley; exploded in 1898

- Rough Riders: Volunteer soldiers during the Spanish-American War

- Theodore Roosevelt: Leader of the Rough Riders; future President

- Battle of San Juan Hill: A battle in Cuba

- Battle of Santiago: The final battle of the war

- The Treaty of Paris: Treaty that ended the war; gave Cuba its independence

- Yellow Journalism:

SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR LESSON PLAN WORKSHEETS

The Spanish-American War lesson plan includes two worksheets: an activity worksheet and a homework assignment. You can refer to the guide on the classroom procedure page to determine when to hand out each worksheet.

MAPS ACTIVITY WORKSHEET

The activity worksheet asks students to find, shade, and label Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippine Islands on the maps printed on the worksheet. They will also label the bodies of water and continents on each map.

Students can also work in pairs to complete the activity.

SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR HOMEWORK ASSIGNMENT

For the homework assignment, students will answer 17 questions about the lesson material.

Worksheet Answer Keys

This lesson plan includes answer keys for the homework assignment. If you choose to administer the lesson pages to your students via PDF, you will need to save a new file that omits these pages. Otherwise, you can simply print out the applicable pages and keep these as reference for yourself when grading assignments.

Thank you for submitting a review!

Your input is very much appreciated. Share it with your friends so they can enjoy it too!

Spanish American War

I liked it because it explained things using kid-friendly language and gave more of an overview than too many details for fifth grade.

I haven't used it yet. But I reviewed it and it looks very good.

This was a great resource

5th Grade Spanish American War Lesson Plan - Just What I Needed!

The material was just what I needed in order to supplement the in-school learning of my boy-girl, 5th grade twins. I needed more information than what the school supplies, since they do not use textbooks. The variety of materials in this unit makes it possible to accommodate each of my children's learning styles. It was easy to sign up for these resources and easy to download the material. I appreciate Clarendon Learning!

Related products

Careers: Game Designer

Careers: Computer Programmer

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark

Make Your Life Easier With Our Lesson Plans

Stay up-to-date with new lessons.

- Lesson Plans

- For Teachers

© 2024 Learn Bright. All rights reserved. Terms and Conditions. Privacy Policy.

- Sign Up for Free

- Get Started

Learning Lab Collections

- Collections

- Assignments

My Learning Lab:

Forgot my password.

Please provide your account's email address and we will e-mail you instructions to reset your password. For assistance changing the password for a child account, please contact us

You are about to leave Smithsonian Learning Lab.

Your browser is not compatible with site. do you still want to continue.

The Road to War

What causes a nation to go to war.

In 1898, people in the United States were paying close attention to events in Cuba, where Cuban guerrillas were fighting for independence from Spain. Although Spain posed no direct threat to the U.S., humanitarian concerns and economic interests made U.S. involvement in the situation there seem inevitable. In addition, those who dreamed of creating an American empire hoped that a war would help the U.S. gain control over Spanish colonies.

Watch this video and jot down information that explains the events and attitudes that led the U.S. to become involved in Cuba.

What events and attitudes led the U.S. to become involved in Cuba? (Click "Save" when you have finished. To see your saved or submitted work again, click "My Work" at the top of the page.)

You must be signed in to save work in this lesson. Log in

Calderwood Writing Course: U.S. History

Interactive Lesson Sign In

Sign in to your PBS LearningMedia account to save your progress and submit your work, or continue as a guest.

The website is not compatible for the version of the browser you are using. Not all the functionality may be available. Please upgrade your browser to the latest version.

- Social Media

- Access Points

- Print/Export Standards

- Standards Books

- Coding Scheme

- Standards Viewer App

- Course Descriptions

- Graduation Requirements

- Course Reports

- Gifted Coursework

- Career and Technical Education (CTE) Programs

- Browse/Search

- Original Student Tutorials

- MEAs - STEM Lessons

- Perspectives STEM Videos

- STEM Reading Resources

- Math Formative Assessments

- CTE Related Resources

- Our Review Process

- Professional Development Programs

- iCPALMS Tools

- Resource Development Programs

- Partnership Programs

- User Testimonials

- iCPALMS Account

![spanish american war assignment Cpalms [Logo]](https://www.cpalms.org/images/cpalms_color.png)

- Not a member yet? SIGN UP

- Home of CPALMS

- Standards Info. & Resources

- Course Descriptions & Directory

- Resources Vetted by Peers & Experts

- PD Programs Self-paced Training

- About CPALMS Initiatives & Partnerships

- iCPALMS Florida's Platform

Imperialism and the Spanish-American War

In this interactive tutorial, learn about imperialism and understand the four major factors that drove America's imperial mindset in the late 1800s. Then learn about the causes and consequences of the Spanish-American War and how the U.S.A. gained new territories as a result.

Attachments

General information, source and access information, aligned standards, suggested tutorials.

In this interactive tutorial, learn the history behind the different territories that belong to the United States, including those that have become states, like Alaska and Hawaii, and those that haven't, like Puerto Rico and American Samoa. You'll also learn about America's role in the construction of the Panama Canal and the Panama Canal Zone the U.S. controlled.

Related Resources

Congratulations, you have successfully created an account..

A verifications link was sent to your email at . Please check your email and click on the link to confirm your email address and fully activate your iCPALMS account. Please check your spam folder.

Did you enter an incorrect email address?

Did not receive an email, you have not completed your profile information. please take a few moments to complete the section below so we can customize your cpalms experience., there was an error creating your account. please contact support [email protected] for assistance., modal header, feedback form.

Please fill the following form and click "Submit" to send the feedback.

Your Email Address: *

Your comment : *, teacher rating, leave cpalms.

You are leaving the CPALMS website and will no longer be covered by our Terms and Conditions.

Stay in touch with CPALMS

Loading....

This website is trying to open a CPALMS page using an iFrame, which is against our terms of use . Click the link below to view the resource on CPALMS.org.

Prologue Magazine

Sailors, Soldiers, and Marines of the Spanish-American War

The legacy of uss maine.

Spring 1998, Vol. 30, No. 1

By Rebecca Livingston

John Matza was a seaman on the USS Maine and one of the 260 servicemen who died in the explosion on February 15, 1898, in Havana Harbor. (NARA, Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, RG 24)

This year marks the centennial of the Spanish-American War, which was fought between May and August 1898. For many reasons, this short war was a turning point in the history of the United States. The four-month conflagration marked the transformation of the United States from a developing nation into a global power. At its conclusion, the United States had acquired the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico. The war was also the first successful test of the new armored navy.

Interest in the Spanish-American War is therefore increasing, and along with it, a desire on the part of many people to learn more about the 280,564 sailors, marines, and soldiers who served, of whom 2,061 died from various causes. The number of participants was not large compared to the approximately three million men who served in the Civil War or the sixteen million men and women who served in World War II. The smaller numbers are in part due to the short length of the Spanish-American War—it ended before many soldiers had even been transported to the war zone. There was also no draft during this war, as there was for the Civil War and the two subsequent world wars. But for the many Americans whose families came to the United States during the mass immigrations of the 1880s and 1890s, the Spanish-American War records are the first military records they can research.

Anyone who has done family or genealogical research in Civil War records will be pleasantly surprised at the fullness and accuracy of the Spanish-American War records. The records tend to be more descriptive and complete, with more consistency in name spelling, than the records for previous wars. By the turn of the century, enlistees were more likely to know their birth dates and how to spell their names. Record keepers were also more likely to list them correctly. These developments increase the likelihood that modern-day researchers will be able to locate birth dates, addresses of next of kin, medical information, and other information about people who served in the war.

With a few significant exceptions, the process of locating records of Spanish-American War veterans is similar to that for Civil War veterans. The best place to start is with National Archives Microfilm Publication T288, General Index to Pension Files, 1861–1934. Pension records were carefully compiled when a veteran applied for benefits on grounds of injury, illness, or disability (later, veterans could also receive benefits based on age) or when the mothers, fathers, widows, and minor children of veterans similarly applied for benefits. Pension records typically include the application forms, proof of marriage, proof of children's births, a summary of military service, and usually death certificates. If you want to check if your great-grandfather served in the Spanish-American War and the only information you have is his name, you may be able to use the pension index to learn his branch of service, rank, and military organization. The pension index includes veterans who served in the regular army, state volunteers who were called into federal service, U.S. volunteers (e.g., Rough Riders), regular U.S. Navy, temporary naval personnel, naval militia, U.S. Coast Signal Service, and U.S. Marine Corps.

Researchers should note that the index to pension files intermingles the names of Civil War and Spanish-American War veterans. It is usually easy to distinguish those who served in the Spanish-American War, however, by the "date of service" (at the top right of the index card) or by the date on which they applied for a pension (at the bottom left of the index card.) When researchers know the branch of service and rank of their veteran, they can search the appropriate army, navy, or Marine Corps records described in this article.

Minorities and Women in the Spanish-American War

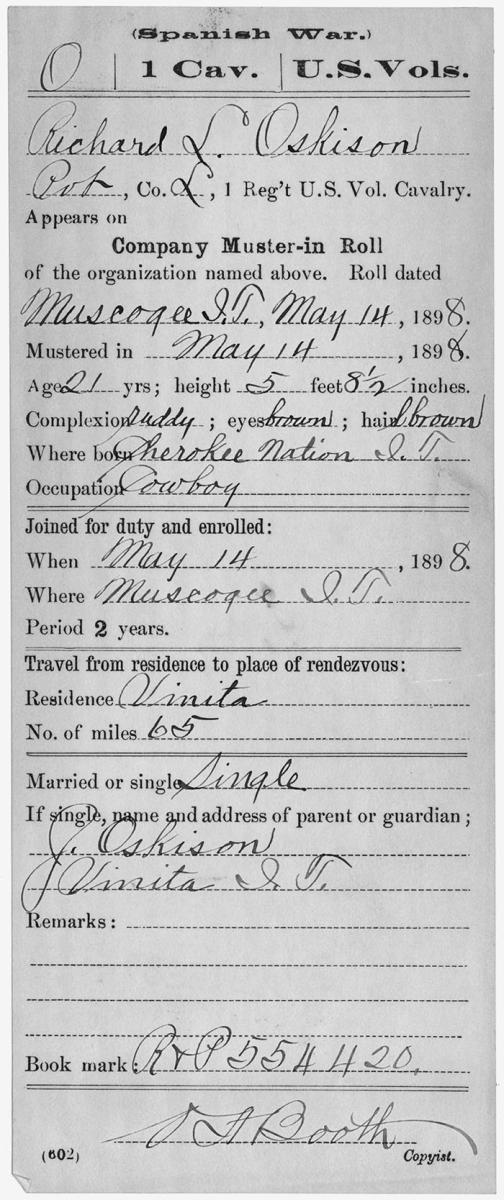

At this time, African Americans served in the U.S. Navy and U.S. Army but not in the U.S. Marine Corps. Women served in the U.S. Army Nurse Corps, but there are no known records at this time of any women in the U.S. Navy or U.S. Marine Corps. Native Americans fought in the Spanish-American War in the U.S. Volunteers, especially in the First Volunteer Cavalry (Rough Riders) and First Territorial Volunteer Infantry.

A newspaper illustration of the Maine' s baseball team identified several crewmembers, including an African American, Fireman William Lambert. (NARA, Records of the Bureau of Naval Personnel, RG 24)

On board U.S. Navy ships, African Americans were integrated with sailors of all nationalities. (Many aliens, including Japanese, Chinese, and Filipinos, served on U.S. Navy ships during that era. Some of them enlisted while the ships were in foreign ports.) According to a list of "colored men on board USS Maine, February 15, 1898," 30 African Americans were among the 350 personnel on board at the time of the explosion. Of the 260 men who died, 22 were African American. They typically worked in the engine rooms; as firemen, oilers, and coal passers; or as mess attendants and landsmen. However, there were also five African American petty officers, three seamen (experienced sailors), and one ordinary seaman. Over the ensuing years, a resurgence of racism led the navy to relegate blacks to ratings of mess attendants, including some men who had held much higher ratings during the Spanish-American War.

The names of the African American sailors who served on USS Maine during the Spanish-American War, and the addresses of their next of kin, can be found in the records of the Naval Records Collection, U.S. Navy Subject File, 1775–1910 (hereinafter called the Navy Subject File). Two African American sailors received the Medal of Honor, one for actions at the Battle of Santiago de Cuba, another for actions just prior to the official start of the war. Another African American sailor, Fireman William Lambert, was the pitcher for the USS Maine' s baseball team. A sketch of him appears in a newspaper clipping from 1898.

African American soldiers served in the U.S. Army's Seventh to Tenth U.S. Volunteer (Colored) Infantries and in the Tenth U.S. Cavalry (whose soldiers were commonly referred to as the "Buffalo Soldiers"). Five soldiers from these regiments were awarded the Medal of Honor. The U.S. Marine Corps did not accept African Americans until World War II.

While there were no known women soldiers, sailors, or marines, the U.S. Army used female nurses both as civilian contract nurses and in the Army Nurse Corps. The Navy Nurse Corps was not established until 1909.

Special Records Relating to the USS Maine Victims and Survivors

For the U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps, the casualties that resulted from the explosion of the USS Maine (which actually occurred nearly three months before the declaration of war) were far greater than those sustained during the war itself. Only 90 of the 350 men on board the USS Maine at the time of the explosion survived. During the war, there were eighty-five U.S. Navy and U.S. Marine Corps casualties, of which sixteen were men killed in action. A list of the "men lost" and "men saved" for the USS Maine is available in the Navy Subject File. This list of casualties was reprinted in the Annual Reports of the Secretary of the Navy for 1898. Due to the widespread newspaper coverage of the incident and the significance of the event to the outbreak of the war, there are special records that provide information about both the victims and survivors. These special records provide a wealth of family and personal information that one rarely finds among government records of that era.

The National Archives has a collection of the letters and checks sent by two relief societies as well as replies from the family members. One of the relief organizations, known as the "Captain Sigsbee Relief Fund," was funded by Congress. The other, the "Ladies Committee Relief Fund," was privately funded. Both made substantial efforts to locate the widows, mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, and even cousins of the lost men. The relief societies helped place offspring of the dead servicemen in orphanages and contributed to the children's care. They also wrote hundreds of letters to post offices and embassies searching for addresses of family members. This correspondence represents a real treasure trove for genealogists. The records show that sailors and marines on the USS Maine had families in all parts of the world: the United States, Canada, Ireland, England, Denmark, Russia, Spain, Germany, Sweden, Norway, Greece, Australia, and Japan.

Many of these letters describe the intense grieving of the families and their desolate poverty, which was aggravated by the loss of pay to their sailor sons and husbands. One mother of twelve children pleads for help because she was too sick to work at anything other than "taking in laundry." Other mothers sent the relief organizations newspaper clippings, prayers, and in one instance, a photograph in tribute to their sons. In some cases, the letters reveal family discord. A sister of one of the USS Maine' s victims asked that her father be denied benefits because he would use it only to get drunk. With her letter, she enclosed a newspaper article describing her father's record of arrests. In another case, a widow resentful of money given to her mother-in-law commented, "She was always mean to her son and kicked him out on his own." Another case involved a unmarried woman, Mary Anderson, who had a baby by a victim of the USS Maine . She applied for relief so she could obtain medicine for the baby, who had fallen ill. Because the sailor already had a wife, Miss Anderson was ineligible for his back pay or pension benefits that she might have been entitled to as a common-law wife. Although the relief fund eventually sent her some money, it came too late to save her sick baby.

The correspondence between the relief organizations and victims' families also hints at the sorry state of race relations at the time. Some of the letters suggest that the relief societies investigated the "worthiness" of some of the African American families before providing benefits.

Filed with this correspondence are also letters from the Navy Department to families of the victims. Usually these letters answer questions about the identities of the victims in response to queries. Most mothers or widows received a letter saying, "We regret to inform you that your son was on the list of persons who were lost." One particularly sad case is revealed in a letter from the Navy Department to the brother-in-law of a marine who wrote, "Please send us information about Private John Brown. His wife is expecting a baby any day now, and is very anxious to know if her husband is alive or dead." Mrs. Brown received a letter of condolence from the Navy Department. She delivered a baby girl on March 3, 1898, sixteen days after the explosion that killed her husband.

There were a few happy letters, though, including one that began, "Your son is recovering at the Navy Hospital, Key West." Another stated, "Although your son had been ordered to USS Maine, he was still on board USS Texas at the time of the explosion."

Correspondence of the relief groups, the letters of condolences from the Navy Department, and the resulting "thank you" letters from the families are among the "correspondence relating to Naval personnel lost in the sinking of the Maine, " which is arranged alphabetically by name of sailor or marine.

Regarding the survivors of the USS Maine, there are medical records of treatment at naval hospitals and their requests for compensation for personal possessions that went down with the ship. Their claims for lost possessions are located in the Navy Subject File. The records also include a list of addresses for all the survivors as of 1926. Another undated list of survivors indicates that seven men later deserted the U.S. Navy, and another two ended up at the Government Hospital of the Insane in Washington, D.C. Many no doubt experienced great trauma witnessing the drowning, burning, and mutilation of their comrades. Many who survived had serious burns and injuries. Some spent long periods convalescing in naval hospitals, and the relief groups offered money to these hospitalized sailors.

The survivors' claims for lost possessions reveal much about shipboard life at the turn of the century. A Japanese cook claimed to have lost "a Japanese-English dictionary, grammar books, a geography book, a translation of Parry's [ sic ] history, a sealskin vest, and a gold scarf pin with opal, a gift from his parents when he left Japan and are therefore without price." Other items claimed to have been lost by survivors included a camera, banjo, and dress sword. More routinely, survivors reported losing clothing, bedding, shaving kits, pipes, watches, knives, and Havana cigars. All of the survivors claimed a whisk broom and ditty box. Incidentally, although a large number of the survivors claimed to have lost Cuban cigars, the navy made allowances for only five hundred cigars per claimant. The USS Maine' s chaplain, who claimed he had lost nine hundred Havana cigars when the ship sank, was out of luck.

Navy Records

Enlisted men. Personnel files for enlisted sailors who served after 1885 are at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri. Researchers seeking to study these records should use Standard Form 180 and send it to the National Personnel Records Center, Military Records, 9700 Page Avenue, St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 1 Archives Drive, St. Louis, MO 63138. The National Archives in Washington, D.C., does not have an index of these personnel records or compiled or consolidated records of any type for enlisted sailors. However, researchers able to visit the National Archives in person, and willing to search through old fragile volumes, can successfully ferret out the information that is typically included in a personnel file.

The National Archives Building does have annual registers of enlistment, called the "keys to enlistments, 1846–1902," for sailors. These registers are arranged by the year (or partial year), then by the first letter of the sailor's surname, and then by the date of his enlistment. The five volumes for 1898 include records for most of the sailors who enlisted in response to the outbreak of the war or who enlisted for the war's duration. If you are searching for a John Brown, for example, you would need to check all the "B" enlistments for 1898. From these records you can learn the sailor's rating, date of enlistment, place of enlistment, terms of enlistment (e.g., one year), the names of the ships on which he served, and his discharge date. The records do not indicate earlier or subsequent enlistments. Sailors could enlist for terms from one to four years. Boys aged sixteen to seventeen were required to enlist until their twenty-first birthday. Since some sailors who served in the Spanish-American War enlisted before 1898, researchers should also check the keys to enlistment for 1894–1897.

Another source of information at the National Archives is a register of Bureau of Navigation correspondence with enlistees for the years 1896–1902. However, this register is only suitable for the most patient and hardy researchers. It is arranged by the first letter of the enlisted man's name and then by the date of the correspondence.

When you know the names of ships on which a veteran served, you can examine U.S. Navy muster rolls and conduct books. Both are arranged alphabetically by name of ship. The muster rolls are nearly complete for every ship. The conduct books are a much less comprehensive collection. Musters were taken quarterly and cover the preceding three months. Within each muster roll, sailors are listed by the first letter of their last name. For each sailor the rolls show his name, rating, date of his present enlistment, place of enlistment (city or ship), citizenship (native, alien, or naturalized), date received on board the ship, reason for leaving the ship (transfer, death, end of enlistment), and place transferred, discharged, or died. If the rolls show a "continuous service certificate number," it means that the sailor had a previous enlistment. A check mark or "OK" penciled in beside a name indicates that the person was entitled to the Spanish-American War campaign badge, the "Sampson Medal."

In addition to the main set of navy muster rolls, there is a separate, smaller set that combines navy muster rolls with shipping articles. Shipping articles are records of the enlistee's terms of enlistment, and they include his signature, something not found in the main set. Some also provide physical descriptions of the enlistee, which are not in the main set either. These records are unavailable for many ships, however.

Conduct books, which describe the enlistee's conduct and performance during drills, are another excellent source for genealogists. They show the same information as the muster rolls, but conduct books may also include address of next of kin, birth date, birthplace, marital status, years of previous naval service, personal description, punishments, scores on drills and training, and medical condition (good or poor). The names in conduct books may be unarranged or arranged alphabetically, by muster number, or by rating. Some conduct books have name indexes.

Commissioned officers. The service records of regular navy officers who served in the Spanish-American War are available on National Archives Microfilm Publication M1328, Abstracts of Service Records of Naval Officers ("Records of Officers"), 1829–1924. The descriptive pamphlet contains a name index to the abstracts. There are also registers of officers arranged by name of ship or station. Other good sources of information about officers are the proceedings of the promotion examining boards and retirement examining boards, found among records of the Judge Advocate General's Office. Names and dates of service of naval officers are printed in List of Officers of the Navy of the United States and of the Marine Corps from 1775–1900, edited by Edward W. Callahan. Most Spanish-American War–era U.S. Navy logbooks include a list of officers in the first few pages of each volume. For biographical records about chaplains, there are Chaplains Division records, a collection of records used to write a history of the Navy Chaplain Corps. Records of medical officers are located among records of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery.

Acting officers. During the Spanish-American War, many volunteers were given temporary commissions. The National Archives has copies of these acting officers' commissions and discharges or resignations, in addition to order books. A register of temporary officers shows their assignments and "remarks." There are special records for acting engineers, including application papers and order books, and a register of commissioned officers of the Auxiliary Naval Force, 1898.

Warrant officers. Application papers and examination papers are available at the National Archives for the following warrant officers: carpenters, boatswains, gunners, and machinists. Many of them were promoted from the comparable chief petty officer position (chief boatswain's mate, chief machinist mate, etc.) Others were appointed from civilian life because they had related experience in their civilian occupations. The papers include letters of recommendation from civilian employers or commanding officers. Promotion Board proceedings are another excellent source for information about warrant officers.

Navy medical records. The National Archives has medical logbooks kept by ships' surgeons and by surgeons at shore stations. These logs describe medical treatments received by officers and enlisted men and their return to duty or death. There are also registers of patients at U.S. Navy hospitals.

Court records. Additional information about some sailors and marines who served in the Spanish-American War, including both officers and enlisted men, can be found in proceedings of U.S. Navy courts-martial, courts of inquiry, boards of investigations, and boards of inquest. In these proceedings, researchers can learn about men who were in trouble, who were investigated for various reasons, or who died by accident or as a result of foul play.

Marine Corps Records

Enlisted men. Personnel jackets ("case files") for marines who fought in the Spanish-American War can be found in two places. If the marine was discharged before 1906, his personnel jacket is at the National Archives. If the marine continued to serve after 1906, his personnel jacket is at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis, Missouri. A typical personnel jacket includes enlistment papers, descriptive list, conduct record from each ship or station, and records relating to campaign badges or awards. Occasionally, the personnel jacket will include a letter from a relative relating to pension benefits, cemetery headstone, or general information. These records usually show the address of next of kin, birth date, birthplace, age, personal description, medical condition, and discharge information. The Marine Corps case files are arranged alphabetically by name of marine for enlistments after 1895. Case files for enlistments before 1895 are arranged by enlistment date. There is a card index to Marine Corps enlistments, 1798–1941.

Officers. The National Archives does not have personnel files for Marine Corps officers for the period around the Spanish-American War. Personnel files beginning with 1896 are at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis. However, researchers who can travel to the National Archives in Washington, D.C., can find monthly reports on the duties to which the officers were assigned and summaries of their service among the Records of the U.S. Marine Corps. There are some correspondence files for officers, 1904–1912, with a name index.

Army Records

Volunteers (regiments raised by states called into federal service). Most soldiers called into service for the Spanish-American War served with regiments raised by their state. A consolidated name index to the compiled military service records of these men has been microfilmed as National Archives Microfilm Publication M871, General Index to Compiled Service Records of Volunteers Who Served During the War With Spain. Compiled service records are arranged by state, type of regiment (artillery, cavalry, and infantry), and then by number of the regiment. Within each regiment, the jackets for individual soldiers are arranged alphabetically. There are compiled military service records for both officers and enlisted men. A typical record includes cards that extract the monthly muster rolls and other regimental papers about that individual. Usually the cards show whether the soldier was present with his company, absent on detached duty, or sick. In addition, you may find medical treatment cards and certificates of discharge for disability. The compiled military service records for the Spanish-American War usually show the date of enlistment, place of enlistment, birth place and date, personal description, medical information, date and place of discharge, and address of next of kin.

Richard L. Oskison's military service record suggests his Native American heritage and records his injury while a "Rough Rider" at San Juan Hill. (NARA Records of the Adjutant General's Office, 1780's–1917, RG 94)

View in National Archives Catalog

U.S. Volunteers. The U.S. volunteers were special regiments raised for the Spanish-American War. The most famous of these is the First Volunteer Cavalry, the official name of the Rough Riders. There were three volunteer cavalry units, three volunteer engineers, ten volunteer infantry regiments, and a volunteer signal corps. The Seventh to Tenth Volunteer Infantries were composed of African American soldiers. There are compiled military service jackets for the enlisted men and officers, similar to the jackets for the state volunteers. Their names are also indexed on National Archives Microfilm Publication M871.

Regular army--enlisted. Enlistment papers for men who served in the regular army, arranged alphabetically by name of soldier, show the personal description, age, and birthplace of the soldier. With the enlistment papers are assignment and descriptive cards. Registers of enlistments are available on National Archives Microfilm Publication M233, Register of Enlistments in the U.S. Army, 1798-1914. The registers show the regiments to which the soldier was assigned and his discharge date. More detailed information about his service can be found in muster rolls, which are arranged by type of regiment, by number of regiment, and then by company, troop, or battery.

Regular army—officers. The War Department did not compile personnel files for regular army officers. For most officers, however, there is a consolidated correspondence file that includes their orders, assignments, oaths of office, monthly fitness reports, promotions, and more. An officer's consolidated correspondence file may be found in several different places. Many officers of the Spanish-American War have a consolidated correspondence file among the Adjutant General's Office Document File ("AGO Doc File"), 1890–1917. The index to this file is available on National Archives Microfilm Publication M698, Index to General Correspondence of the Office of the Adjutant General, 1890–1917. Other officers have consolidated correspondence files among the Appointment, Commission, and Personal Branch (ACP) of the Adjutant General's Office. The index to the ACP files are available on National Archives Microfilm Publication M1125, Name and Subject Index to the Letters Received by the Appointment, Commission, and Personal Branch of the Adjutant General's Office, 1871–1894. Many of the most frequently requested ACP files have been reproduced on microfiche; the others are available in the original format. Officers whose service goes back to the Civil War may have a consolidated correspondence file among the Commission Branch (CB) of the Adjutant General's Office. The CB files are reproduced on National Archives Microfilm Publication M1064, Letters Received by the Commission Branch of the Adjutant General's Office, 1863–1870. The descriptive pamphlet includes a list of frequently requested files. A complete card index is also available. For regular army medical officers, there are service cards and personal papers.

Nurses care for convalescents at Sternberg Hospital in Camp Thomas, Chickamauga Park, Georgia. (NARA 80-G-7U-1)

Contract nurses and surgeons. During the Spanish-American War, the army hired many civilian nurses and surgeons by contract. Records of the Surgeon General's Office include case files, personal data cards, and correspondence files for contract nurses and doctors, most of which is arranged alphabetically. A researcher should also check the index to the Surgeon General's general correspondence (Doc File), 1889–1917, under the letter "C" for "contract surgeons" and "contract nurses." Under these categories, there are alphabetically arranged index cards by name of contractor. The cards provide the pertinent consolidated document file number. In addition, there are records relating to contract surgeons among the personal papers of medical officers and physicians.

Unless otherwise mentioned, all the records described in this article are available at the National Archives Building in downtown Washington, D.C. Researchers who are unable to visit the National Archives in person may request copies of records through the mail. This request is made on a National Archives Trust Fund Form 80 [ see note ], National Archives Order for Copies of Veterans Records. To obtain this form, write to the National Archives and Records Administration, Attn: NWDT1, 700 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20408-0001.

Note: NATF Form 80 was discontinued in November 2000. Use NATF 85 for military pension and bounty land warrant applications, and NATF 86 for military service records for Army veterans discharged before 1912.

See also these related records:

- NARA Records Relating to Service in the Spanish-American War

- Microfilm Relating to Service in the Spanish-American War

Military Records at the Archives & Library of the Ohio History Connection

- Military Records

- Revolutionary War

- War of 1812

- Mexican-American War

Ohio and the Spanish-American War

Collection information and access, spanish-american war battle flags, colonel charles young, the 9th ohio volunteer infantry battalion, new discovery layer - one catalog for print, state archives, manuscripts & av collections.

- Can't Find What You're Looking For?

- World War I

- World War II

15,354 Ohioans served in volunteer and Ohio National Guard Units during the Spanish-American War. Many people in the U.S. objected Spain's treatment of their then colony Cuba. The United States declared war on Spain on April 25, 1898 by President William McKinley, an Ohioan, after the Maine, a U.S. battle ship, exploded near Cuba. The conflict lasted less than 3 months with Spain, and ended in a complete victory for the United States with the 1898 Treaty of Paris. Cuba technically gained independence and the U.S. acquired the Spanish colonies of Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines as territories. The 4th, 6th, and 8th Ohio Volunteer Infantry's served overseas during the conflict. 230 total deaths were recorded.

The Official Roster of Ohio Soldiers in the War with Spain, 1898-1899 [R 973.89471 B786i 1991] is available for research in the Library with a separate index that contains regimental histories.

The Spanish-American War Rolls, 1898 [State Archives Series 1139] include assignment cards, muster rolls, payrolls, correspondence, canceled checks, and company descriptive rolls. They are available on microfilm rolls GR 2062 through GR 2087 in the Library Microfilm Room.

Spanish-American War Veterans Grave Registration Cards, A-Z [State Archives Series 6992] can be paged for research in the Library. Files include the veteran's name, company, birth date, and death date ranging from 1920 to 1980.

Correspondence to the Governor and Adjutant General of Ohio, 1861-1898 [State Archives Series 147] contains correspondence related to Spanish-American War topics. Responses to these letter can be found in Correspondence from the Adjutant General, 1861-1898 [State Archives Series 146]. Both collections can be paged for researched in the Library.

Further Spanish-American War information can be accessed by using Ancestry and Fold3 which are available via computers in the Library.

You can browse all Spanish-American War era newspapers, library, archives, and museum records using our Online Collections Catalog.

Below is a an example of a Spanish-American War battle flag found in our museum collections.

Description: This flag is a silk guidon of 1st Ohio Light Artillery, Battery H and Battery I. The gold appliques of crossed cannons are an "I" above and an "H” below against a red field. At one time it was likely a swallowtail shape but has since been torn. Both Battery H and I mustered out of Cincinnati. President McKinley, a fellow Ohioan, issued the first call for volunteers on April 23, 1898. They easily filled Ohio's initial quota of six infantry regiments and four batteries of light artillery. The term of enlistment for volunteer troops in 1898 was for two years or until discharged.

The Guidon of 1st Ohio Light Artillery, Battery H and I flag is part of the Ohio Adjutant General's Battle Flag collection maintained and preserved by the Ohio History Connection. More images of the Ohio battle flags from the Spanish-American War era are available on Ohio Memory , a statewide digital library program.

Charles Young was the first African American to achieve the rank of colonel in the United States Army and, until his death in 1922, was the highest-ranking African American officer. In 1884, he reported to the United States Military Academy at West Point. He became its third African American graduate five years later. After graduating with a commission as a second lieutenant, he proceeded to serve 28 years with black troops in the 9th and 10th U.S. Cavalries, also known as the Buffalo Soldiers. He had multiple military assignments both foreign and domestic, and it was after his service in Mexico, during the 1916 Punitive Expedition, that he was promoted to lieutenant colonel. Young was placed on the U.S. Army's inactive list during World War I due to health concerns, later riding from Wilberforce, Ohio where he was a professor to Washington, D.C. to prove his fitness for duty. Young was reinstated as a full colonel in 1918. He died in 1922 while on a reconnaissance mission in Nigeria. He received a full military funeral and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Below is a photograph of Colonel Charles Young in uniform. More images of Colonel Young and collection finding aids pertaining to him are available on Ohio Memory , a statewide digital library program.

Black Cadet in a White Bastion: Charles Young at West Point by Brian Shellum [B Y84s 2006] is available to be paged and researched in the Library. Shellum also authored Black Officer in a Buffalo Soldier Regiment: The Military Career of Charles Young [B Y84s1 2010] which is also available to be paged and researched in the Library.

The Glendower Photograph Collection, circa 1850-1940 [AV 300] includes photographs of Charles Young and his family. This collection contains a compilation of photographs from smaller collections once held at the Glendower Museum in Warren County, Ohio.

Additional collections pertaining to Colonel Young may be accessed at the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center in Wilberforce, Ohio. Some collection materials are available on their Ohio Memory webpage.

The 9th Ohio Volunteer Infantry Battalion was an African American regiment formed in 1881 with companies in Springfield and Columbus. A company was added in Xenia in 1884, then in Cleveland in 1898. The battalion was commanded by Major Charles Young. The regiment did not see overseas service during the Spanish-American War, but spent duration of the war at several camps across the United States. This regiment, along with the 10th U.S. Cavalry, were also known as the Buffalo Soldiers.

Below is a photograph of Arthur Kelton Lawrence, who served as a hospital steward in the 9th Battalion during the Spanish-American War. More images related to the 9th Ohio Volunteer Infantry Battalion from the Spanish-American War era are available on Ohio Memory , a statewide digital library program.

The Lawrence Family Collection [P 104] contains photographs and oversize materials related to Dr. Thomas Lawrence and his family, including his son Arthur Kelton Lawrence. The collection includes photographs from the Spanish-American War. A finding aid for this collection is available on Ohio Memory.

Black Soldiers-Black Sailors-Black Ink: Research Guide on African-Americans in U.S. Military History, 1526-1900 by Thomas Truxtun Moebs [R 355.008996073 M722b 1994] is available for research in the Library. It discusses African American military service in America through the Spanish-American War.

Additional collections pertaining to the 9th O.V.I. and the Buffalo Soldiers may be accessed at the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center in Wilberforce, Ohio. Some collection materials are available on their Ohio Memory webpage.

Search The Library Catalog

Discover books, newspapers, periodicals, company catalogs, pamphlets, maps, atlases and more!

Can't Find What You're Looking For?

We do not hold military service or pension records. That information can be obtained by contacting the National Archives and Records Administration. Records prior to World War I are located at the National Archives Building in Washington, D.C.

You may also wish to read the military records section of the National Archives Genealogy webpage.

If you have questions, please contact us at [email protected] or 614.297.2510.

- << Previous: Civil War

- Next: World War I >>

- Last Updated: Mar 18, 2024 1:37 PM

- URL: https://ohiohistory.libguides.com/military

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Cuban movement for independence from Spain in 1895 garnered considerable American support. When the USS Maine sank, the United States believed the tragedy was the result of Spanish sabotage and declared war on Spain. The Spanish-American War lasted only six weeks and resulted in a decisive victory for the United States.

Spanish-American War, (1898), conflict between the United States and Spain that ended Spanish colonial rule in the Americas and resulted in U.S. acquisition of territories in the western Pacific and Latin America.. Origins of the war. The war originated in the Cuban struggle for independence from Spain, which began in February 1895. The Cuban conflict was injurious to U.S. investments in the ...

Assignment on edg Learn with flashcards, games, and more — for free. ... The Spanish-American War Quiz (US History) 9 terms. Beastmode6704. Preview. us history midterm review. 51 terms. Mg123123. Preview. Imperialism in Asia and Africa. 25 terms. Sofia_Palomo2. Preview. Gilded Age Last Part.

VIDEO CLIP: Early Film and the Spanish-American War (2:22) VIDEO CLIP: The Battle of Manila (2:51) VIDEO CLIP: Foreign Policy and the Spanish-American War (2:19) VIDEO CLIP: Puerto Rico and The ...

Explore the causes, events and effects of the Spanish-American War through primary sources and a WebQuest Interactive. Learn how the war shaped American foreign policy, imperialism and the role of the press.

Treaty of Paris . The Treaty of Paris ending the Spanish American War was signed on December 10, 1898. In it, Spain renounced all claim to Cuba, ceded Guam and Puerto Rico to the United States and ...

The Spanish-American War (April 21 - December 10, 1898) began in the aftermath of the internal explosion of USS ... Campos's reluctance to accept his new assignment and his method of containing the revolt to the province of Oriente earned him criticism in the Spanish press.

Stephan McAteer discusses the Spanish-American War, and the MacArthur Museum of Arkansas Military History exhibit, "Splendid Little War." 5 minutes Bell Ringer Assignment

The Spanish-American War (1898) was fought between the United States and Spain, a conflict that ended with Spain losing most of its overseas empire and the U.S. emerging as a world power. After only a few months of fighting and a series of American victories in the Caribbean and the Pacific, the Treaty of Paris was signed on December 10, 1898 ...

Spanish-American War: 5 Day Lesson Overview: On the Historical Thinking Matters website, students work through the Spanish-American War investigation. They read the nine documents, answer guiding questions on the interactive on-line notebook, and prepare to complete the final essay assignment using their notes. Each day includes a brief teacher ...

The Spanish-American War lesson plan includes two content pages. The Spanish-American War, fought between Spain and America from April 25, 1898 to August 12, 1898, lasted just three and a half months. These countries fought this war mostly over Cuba's independence. At this time, Cuba was one of Spain's colonies, as were the Philippines.

The Spanish-American War was preceded by three years of intense fighting by Cuban revolutionaries who sought to gain independence from Spanish colonial rule. From 1895-98, the conflict in Cuba captured the attention of the American public mostly because of the economic and political instability within close geographical proximity to the United States. The U.S. press and political ...

Spanish-American War. This collection highlights artifacts and secondary sources to help students explore the history of the Spanish-American War. Specific topics referenced in this collection include the explosion of US Maine and political and military figures. Time Period: April 21, 1898-August 13, 1898 (approx. 5 months)

March. READ: Reconcentration Camps. Head Note: By the late 1800's, the Spanish were losing control of their colony, Cuba. Concerned about guerilla warfare in the countryside, they moved rural Cubans to "reconcentration" camps where the Spanish claimed they would be better able to protect them. However, people around the world saw newspaper ...

Students will begin to understand multiple reasons for the Spanish-American War and that textual evidence can be used to support arguments about cause. Students will begin to read documents historically, using skills of sourcing, contextualization, careful reading, and corroboration. ... Webquest assignment; Step 1: 5 minutes: Share homework.

Although Spain posed no direct threat to the U.S., humanitarian concerns and economic interests made U.S. involvement in the situation there seem inevitable. In addition, those who dreamed of creating an American empire hoped that a war would help the U.S. gain control over Spanish colonies. Watch this video and jot down information that ...