- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Slavery in British and American Literature

Introduction, general overviews.

- Bibliographies

- Anthologies

- Print Culture

- Slavery and English Literature

- Slave Narratives

- Popular Works

- The American Novel

- Neo-Slave Narratives

- Harriet Beecher Stowe

- Frederick Douglass

- Harriet Jacobs

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Dreams and Dreaming

- Literature and Culture

- Literature of the British Caribbean

- Literature, Slavery, and Colonization

- Phillis Wheatley

- Poetry in the British Atlantic

- Shakespeare and the Atlantic World

- Slavery in British America

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Ecology and Nineteenth-Century Anglophone Atlantic Literature

- Science and Technology (in Literature of the Atlantic World)

- The Danish Atlantic World

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Slavery in British and American Literature by Judie Newman LAST REVIEWED: 19 March 2013 LAST MODIFIED: 19 March 2013 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199730414-0159

For some literary scholars, all literature that follows the establishment of Atlantic slavery is inflected by the existence of the “peculiar institution.” Toni Morrison has argued that the prevalence of gothic in 19th-century writing, particularly in America (not naturally a land of haunted castles and ruined abbeys), results from the repressed awareness of a dark abiding Africanist presence in American culture. Slavery thus underwrites the broad generic qualities of the national literature. In the view of Pierre Macherey, the silences and omissions in literature are as important as the presences. Slavery is a shrieking absence in many canonical works of American literature; “writing back “against such silences has become a major critical activity. White writers are now regularly examined in the light of the history of slavery: Emily Brontë’s Heathcliff as a black orphan from the slave port of Liverpool (in Wuthering Heights ) or the Caribbean estate in Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park , for example. Almost all writers from the American South (and especially William Faulkner) can be viewed in this light. If little space is given in the current bibliography to canonical English writers who engage at some level with slavery, it is because the critical literature on their work is already extensive. More narrowly, in the English-speaking world “slavery in literature” includes the writings of slaves and former slaves, as well as works written about slavery by non-slaves. Though the field is dominated by American works, British, Caribbean, and postcolonial writers are also significant. Temporally the field includes the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, with a significant engagement by later writers with the legacy of slavery. Only one later genre, however, the neo-slave narrative, is formally connected to the literary tradition of the 19th-century slave narratives. “Literature” is a capacious category in this field and is not confined to conventional belles lettres (novels, plays, poetry) but includes significant examples of oratory, addresses, letters, folk material, minstrelsy and life-writings. There is also a dynamic relationship between literary criticism and creative writing, and between popular blockbusters and the academy. Controversies over popular works have been a spur to the writing of both novels and scholarly works. Scholarship on slavery may appear in works concerning African American, Caribbean or English literature, and despite the exponential expansion of the field since the 1980s there is no single bibliography to be recommended. Nor is there a single journal devoted to slavery in literature.

The topic of slavery in literature is rarely the subject of a discrete work. More commonly it receives coverage in general overviews of African American literature or in discussions of race in literature. In one argument slavery inflects all American literature in a repressed subtext in canonical white writers ( Morrison 1992 ). Criticism also varies in the degree to which it takes into account Latin American and Caribbean elements ( Rosenthal 2004 ), African traditions ( M’Baye 2009 ) or white writers ( McDowell and Rampersad 1989 ). Recent scholarship such as Bruce 2001 has redressed the neglect of the early period and of the American North and there are now histories and companions that can be unequivocally recommended for their comprehensive coverage, including Andrews, et al. 1997 ; Graham 2004 ; and Graham and Ward 2011 . For the scholar of “slavery in literature” the best friend is often the excellent index to such overviews.

Andrews, William L., Frances Smith Foster, and Trudier Harris, eds. The Oxford Companion to African American Literature . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

A thoroughly comprehensive volume with entries on more than four hundred writers, along with literary movements and forms, literary criticism, the novel, and a host of others. A broadly conceived image of African American literary culture allows for the inclusion of entries on iconic figures in African American literature.

Bruce, Dickson D., Jr. The Origins of African American Literature, 1680–1865 . Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2001.

Significant for its challenge to the idea that African American voices were silenced in the colonial and early national period. And includes an important reevaluation of the fiction of James McCune Smith.

Graham, Maryemma, ed. The Cambridge Companion to the African American Novel . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

DOI: 10.1017/CCOL0521815746

Fifteen essays by leading scholars arranged chronologically, covering the novel of slavery and its legacy, with particular attention to literary movements and periods, and an excellent bibliography.

Graham, Maryemma, and Jerry R. Ward, eds. The Cambridge History of African American Literature . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

DOI: 10.1017/CHOL9780521872171

At 860 pages, this volume offers a huge amount of material on the literature of slavery, with works discussed on their individual merits and in relation to events in American history. Features excellent essays on early print literature of Africans in America and the neo-slave narrative.

M’Baye, Babacar. The Trickster Comes West: Pan African Influence in Early Black Diasporan Narratives . Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009.

Explores relationships between African American, African Caribbean, and African British narratives of slavery and African literary influences—particularly the use of the Trickster motif in such figures as Anancy (Spider), Leuk (Rabbit), and Mbe (Tortoise)—in slave writers, including Olaudah Equiano, Mary Prince and Phillis Wheatley.

McDowell, Deborah, and Arnold Rampersad, eds. Slavery and the Literary Imagination . Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989.

The best starting point for any consideration of the impact of slavery on American literature, with all the essays by acknowledged authorities. Although the emphasis falls on African Americans, substantial attention is also paid to white writers. Hazel V. Carby provides a valuable essay on the historical novel of slavery.

Morrison, Toni. Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1992.

In this groundbreaking study, the Nobel Prize–winning novelist argues for a deep abiding Africanist presence in American culture, delineating the effect of a racialized history on Willa Cather, Edgar Allan Poe, Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Ernest Hemingway, and Mark Twain. The discussion of American gothic as a repressed awareness of dark others was highly influential.

Rosenthal, Debra J. Race Mixture in Nineteenth-Century U.S. and Spanish American Fictions: Gender, Culture and Nation Building . Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

In a thoroughly transnational comparative study, Rosenthal broadens critical discussion of American literature to include Latin America, examining interracial sexual and cultural mixing, and fictional treatments of skin difference, incest, and inheritance laws, in major writers from the United States, Cuba, Peru, and Ecuador.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Atlantic History »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abolition of Slavery

- Abolitionism and Africa

- Africa and the Atlantic World

- African American Religions

- African Religion and Culture

- African Retailers and Small Artisans in the Atlantic World

- Age of Atlantic Revolutions, The

- Alexander von Humboldt and Transatlantic Studies

- America, Pre-Contact

- American Revolution, The

- Anti-Catholicism and Anti-Popery

- Army, British

- Art and Artists

- Asia and the Americas and the Iberian Empires

- Atlantic Biographies

- Atlantic Creoles

- Atlantic History and Hemispheric History

- Atlantic Migration

- Atlantic New Orleans: 18th and 19th Centuries

- Atlantic Trade and the British Economy

- Atlantic Trade and the European Economy

- Bacon's Rebellion

- Barbados in the Atlantic World

- Barbary States

- Berbice in the Atlantic World

- Black Atlantic in the Age of Revolutions, The

- Bolívar, Simón

- Borderlands

- Bourbon Reforms in the Spanish Atlantic, The

- Brazil and Africa

- Brazilian Independence

- Britain and Empire, 1685-1730

- British Atlantic Architectures

- British Atlantic World

- Buenos Aires in the Atlantic World

- Cabato, Giovanni (John Cabot)

- Cannibalism

- Captain John Smith

- Captivity in Africa

- Captivity in North America

- Caribbean, The

- Cartier, Jacques

- Catholicism

- Cattle in the Atlantic World

- Central American Independence

- Central Europe and the Atlantic World

- Chartered Companies, British and Dutch

- Chinese Indentured Servitude in the Atlantic World

- Church and Slavery

- Cities and Urbanization in Portuguese America

- Citizenship in the Atlantic World

- Class and Social Structure

- Coastal/Coastwide Trade

- Cod in the Atlantic World

- Colonial Governance in Spanish America

- Colonial Governance in the Atlantic World

- Colonialism and Postcolonialism

- Colonization, Ideologies of

- Colonization of English America

- Communications in the Atlantic World

- Comparative Indigenous History of the Americas

- Confraternities

- Constitutions

- Continental America

- Cook, Captain James

- Cortes of Cádiz

- Cosmopolitanism

- Credit and Debt

- Creek Indians in the Atlantic World, The

- Creolization

- Criminal Transportation in the Atlantic World

- Crowds in the Atlantic World

- Death in the Atlantic World

- Demography of the Atlantic World

- Diaspora, Jewish

- Diaspora, The Acadian

- Disease in the Atlantic World

- Domestic Production and Consumption in the Atlantic World

- Domestic Slave Trades in the Americas

- Dutch Atlantic World

- Dutch Brazil

- Dutch Caribbean and Guianas, The

- Early Modern Amazonia

- Early Modern France

- Economy and Consumption in the Atlantic World

- Economy of British America, The

- Edwards, Jonathan

- Emancipation

- Empire and State Formation

- Enlightenment, The

- Environment and the Natural World

- Europe and Africa

- Europe and the Atlantic World, Northern

- Europe and the Atlantic World, Western

- European Enslavement of Indigenous People in the Americas

- European, Javanese and African and Indentured Servitude in...

- Evangelicalism and Conversion

- Female Slave Owners

- First Contact and Early Colonization of Brazil

- Fiscal-Military State

- Forts, Fortresses, and Fortifications

- Founding Myths of the Americas

- France and Empire

- France and its Empire in the Indian Ocean

- France and the British Isles from 1640 to 1789

- Free People of Color

- Free Ports in the Atlantic World

- French Army and the Atlantic World, The

- French Atlantic World

- French Emancipation

- French Revolution, The

- Gender in Iberian America

- Gender in North America

- Gender in the Atlantic World

- Gender in the Caribbean

- George Montagu Dunk, Second Earl of Halifax

- Georgia in the Atlantic World

- German Influences in America

- Germans in the Atlantic World

- Giovanni da Verrazzano, Explorer

- Glorious Revolution

- Godparents and Godparenting

- Great Awakening

- Green Atlantic: the Irish in the Atlantic World

- Guianas, The

- Haitian Revolution, The

- Hanoverian Britain

- Havana in the Atlantic World

- Hinterlands of the Atlantic World

- Histories and Historiographies of the Atlantic World

- Hunger and Food Shortages

- Iberian Atlantic World, 1600-1800

- Iberian Empires, 1600-1800

- Iberian Inquisitions

- Idea of Atlantic History, The

- Impact of the French Revolution on the Caribbean, The

- Indentured Servitude

- Indentured Servitude in the Atlantic World, Indian

- India, The Atlantic Ocean and

- Indigenous Knowledge

- Indigo in the Atlantic World

- Internal Slave Migrations in the Americas

- Interracial Marriage in the Atlantic World

- Ireland and the Atlantic World

- Iroquois (Haudenosaunee)

- Islam and the Atlantic World

- Itinerant Traders, Peddlers, and Hawkers

- Jamaica in the Atlantic World

- Jefferson, Thomas

- Jews and Blacks

- Labor Systems

- Land and Propert in the Atlantic World

- Language, State, and Empire

- Languages, Caribbean Creole

- Latin American Independence

- Law and Slavery

- Legal Culture

- Leisure in the British Atlantic World

- Letters and Letter Writing

- Literature, Slavery and Colonization

- Liverpool in The Atlantic World 1500-1833

- Louverture, Toussaint

- Manumission

- Maps in the Atlantic World

- Maritime Atlantic in the Age of Revolutions, The

- Markets in the Atlantic World

- Maroons and Marronage

- Marriage and Family in the Atlantic World

- Material Culture in the Atlantic World

- Material Culture of Slavery in the British Atlantic

- Medicine in the Atlantic World

- Mental Disorder in the Atlantic World

- Mercantilism

- Merchants in the Atlantic World

- Merchants' Networks

- Migrations and Diasporas

- Minas Gerais

- Mining, Gold, and Silver

- Missionaries

- Missionaries, Native American

- Money and Banking in the Atlantic Economy

- Monroe, James

- Morris, Gouverneur

- Music and Music Making

- Napoléon Bonaparte and the Atlantic World

- Nation and Empire in Northern Atlantic History

- Nation, Nationhood, and Nationalism

- Native American Histories in North America

- Native American Networks

- Native American Religions

- Native Americans and Africans

- Native Americans and the American Revolution

- Native Americans and the Atlantic World

- Native Americans in Cities

- Native Americans in Europe

- Native North American Women

- Native Peoples of Brazil

- Natural History

- Networks for Migrations and Mobility

- Networks of Science and Scientists

- New England in the Atlantic World

- New France and Louisiana

- New York City

- Nineteenth-Century Atlantic World

- Nineteenth-Century France

- Nobility and Gentry in the Early Modern Atlantic World

- North Africa and the Atlantic World

- Northern New Spain

- Novel in the Age of Revolution, The

- Oceanic History

- Pacific, The

- Paine, Thomas

- Papacy and the Atlantic World

- People of African Descent in Early Modern Europe

- Pets and Domesticated Animals in the Atlantic World

- Philadelphia

- Philanthropy

- Plantations in the Atlantic World

- Political Participation in the Nineteenth Century Atlantic...

- Polygamy and Bigamy

- Port Cities, British

- Port Cities, British American

- Port Cities, French

- Port Cities, French American

- Port Cities, Iberian

- Ports, African

- Portugal and Brazile in the Age of Revolutions

- Portugal, Early Modern

- Portuguese Atlantic World

- Poverty in the Early Modern English Atlantic

- Pre-Columbian Transatlantic Voyages

- Pregnancy and Reproduction

- Print Culture in the British Atlantic

- Proprietary Colonies

- Protestantism

- Quebec and the Atlantic World, 1760–1867

- Race and Racism

- Race, The Idea of

- Reconstruction, Democracy, and United States Imperialism

- Red Atlantic

- Refugees, Saint-Domingue

- Religion and Colonization

- Religion in the British Civil Wars

- Religious Border-Crossing

- Religious Networks

- Representations of Slavery

- Republicanism

- Rice in the Atlantic World

- Rio de Janeiro

- Russia and North America

- Saint Domingue

- Saint-Louis, Senegal

- Salvador da Bahia

- Scandinavian Chartered Companies

- Science, History of

- Scotland and the Atlantic World

- Sea Creatures in the Atlantic World

- Second-Hand Trade

- Settlement and Region in British America, 1607-1763

- Seven Years' War, The

- Sex and Sexuality in the Atlantic World

- Ships and Shipping

- Slave Codes

- Slave Names and Naming in the Anglophone Atlantic

- Slave Owners In The British Atlantic

- Slave Rebellions

- Slave Resistance in the Atlantic World

- Slave Trade and Natural Science, The

- Slave Trade, The Atlantic

- Slavery and Empire

- Slavery and Fear

- Slavery and Gender

- Slavery and the Family

- Slavery, Atlantic

- Slavery, Health, and Medicine

- Slavery in Africa

- Slavery in Brazil

- Slavery in British and American Literature

- Slavery in Danish America

- Slavery in Dutch America and the West Indies

- Slavery in New England

- Slavery in North America, The Growth and Decline of

- Slavery in the Cape Colony, South Africa

- Slavery in the French Atlantic World

- Slavery, Native American

- Slavery, Public Memory and Heritage of

- Slavery, The Origins of

- Slavery, Urban

- Sociability in the British Atlantic

- Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts...

- South Atlantic

- South Atlantic Creole Archipelagos

- South Carolina

- Sovereignty and the Law

- Spain, Early Modern

- Spanish America After Independence, 1825-1900

- Spanish American Port Cities

- Spanish Atlantic World

- Spanish Colonization to 1650

- Subjecthood in the Atlantic World

- Sugar in the Atlantic World

- Swedish Atlantic World, The

- Technology, Inventing, and Patenting

- Textiles in the Atlantic World

- Texts, Printing, and the Book

- The American West

- The French Lesser Antilles

- The Fur Trade

- The Spanish Caribbean

- Time(scapes) in the Atlantic World

- Toleration in the Atlantic World

- Transatlantic Political Economy

- Tudor and Stuart Britain in the Wider World, 1485-1685

- Universities

- USA and Empire in the 19th Century

- Venezuela and the Atlantic World

- Visual Art and Representation

- War and Trade

- War of 1812

- War of the Spanish Succession

- Warfare in Spanish America

- Warfare in 17th-Century North America

- Warfare, Medicine, and Disease in the Atlantic World

- West Indian Economic Decline

- Whitefield, George

- Whiteness in the Atlantic World

- William Blackstone

- William Shakespeare, The Tempest (1611)

- William Wilberforce

- Witchcraft in the Atlantic World

- Women and the Law

- Women Prophets

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|193.7.198.129]

- 193.7.198.129

Slavery Role in the American Literature Essay

Introduction.

In the period between the sixteenth and the eighteenth century, a number of European countries led by Portugal and Spain went to Africa to search for slaves. It is said that, during this period, the agrarian revolution had just taken off and as a result, more man power was needed to work in the plantations that were being established in America. In addition, the modern day United States of America was witnessing massive migration of Europeans.

Most of them carried with them this agrarian technology, a situation that made them require a lot of people to work for them. This was because the land was in plenty and very few laborers were available to work there. They therefore turned to African and especially in West Africa where they shipped out millions of young and energetic men to work in the plantations. This is what came to form the modern day Africa American community in the United State of America.

Identify and discuss how Stowe uses biblical images to incite a strong response to oppose slavery

Slavery is not a unique phenomenon amongst Christians. This is because the Bible narrates a story of how Jacob’s children became slaves in Egypt. To begin with, we find that Stowe has noted that between 1780 and1830, the religious groups tried in vain to pressurize the government to abolish slavery in both the north and south of the United States of America. She has observed that in their letters they argued that the Black people are not sub human beings.

They have stated that God created all human beings equal and therefore no one should oppress the other for his or her own gains. Stowe has said that the anti slavery groups argued that it was not possible to have the White Christians oppressing the Black Christians counterparts.

In addition, we find that the issue of morality has also been addressed. Stowe has claimed that the anti slavery groups questioned the morality of the white Christians who were at the fore front in the oppression of the Black people. The Bible teachings emphasizes on people to be of high morality. However, this was in contrast with what the White Christians in the United States were doing. She has further observed that the anti slavery crusaders found it untrue that the Blacks were being favored by being brought from Africa to the United States of America. She says that many people died on the way in the course of being transported, which would certainly be termed as murder.

One of commandments in the Holy Bible dictates that no one should kill the other. Stowe has observed that those people who advocated for slavery regarded it as a way of saving Africans from the misery in their former lands. However, those who were strongly opposed to this argued that it was only God who could bring salvation to human kind. As a result, the anti slavery campaigners claimed that if slaves were being saved, then they should be let free so that the salvation aspect become meaningful.

The Biblical teachings do not advocate for war or wrangles amongst people in any given society. However, due to non observance of these teachings, Stowe has claimed that there was a lot of conflict and war as the southerners refused to let go of slaves in the United States of America. She argues that the White Americans were of the opinion that war is good. Names such as Augustine St. Claire have been used to represent their godlessness; that is they are known to serve their own pleasures. This is in contrast with what the word saint is used to signify among the Christians. Therefore, the Whites on one hand supported the Christian teachings but on the other hand failed to execute what those teachings talked of.

Discuss how Jacobs’ journals reinforce the attitude of the Whites that slaves were inferior and/or childlike and needed to be “parented.”

The Whites have for a long time regarded the Black community as inferior to them. To them, that was an illustration that the Black people could not do or discover anything on their own without the assistance of the White people. Although these remarks have been proved to be inaccurate over the years, during the slavery period, the Whites regarded the Black people as sub humans. As a result, they would treat them the same they would to other animals which were not equal to a human being.

According to Yellin (2004), Harriet Ann Jacobs was a Black woman and therefore born a slave in 1813. However, as she grew up she managed to run away from slavery. He has noted that despite being a poor woman, she managed to write several articles to different people showing them how slavery had impacted on the lives of the Blacks in the United States of America. He has claimed that at one point, Jacobs managed to travel to United Kingdom where she found out that people were not discriminated on basis of their skin color.

This motivated her to come up with an abolitionist movement that would help free all the enslaved the Blacks in her country. He however notes that most of her writings revolved around how she would get assistance from other people in her society. This, according to the Whites, amounts to dependency which should not be the case if a person is healthy and able to work. Therefore, he argues that this is one way in which the Whites’ superiority over the Black community is manifested.

Furthermore, Garfield (1996) has observed that Jacobs organized and helped in the construction of barracks for the freed men in her society. However, he has noted that only about 500 people could be accommodated in those houses out of the 1500 targeted. This is a clear demonstration of how the Black people were disorganized in their work. It was hoped that if the White man was in charge of such construction, the total number of people envisaged to be housed would be met. This is an indication that the Blacks needed to be taught more on how to conduct their work by the Whites.

How the beliefs of Lincoln about God and the country are reflected in his address to congress. How do you think he perceived of his role as president within this “spiritual” conflict

Lincoln has remained a key figure in the United States politics because of the role he played in ensuring that slaves were set free. According to Abraham Lincoln, God created all human beings to be equal and therefore no one should have the right to oppress the other because of their racial or political affiliations. As a result, he marshaled the congress in passing laws that set the slaves free.

In addition, we find that Abraham Lincoln believed that people should be let to decide what they want to do other than be coerced. He observed that God created man and let him do whatever pleased him as long as he stuck to the guidelines that God had given him. This was meant to call upon slave owners to let them free.

As a president of the United States, Lincoln knew that it was not easy to persuade slave owners to emancipate slaves because this was the order of the day in many parts of the country. However, he knew that as a president he had the power to punish those who went against his directives. He however knew that he had to approach this matter cautiously not to be seen as slave’s sympathizer to avoid loosing faith amongst the electorate.

Slavery caused a lot of pain not only to the people directly enslaved but also to their relatives and friends who had to see such people being shipped for slavery. Although this trade is no longer visible in the contemporary world, more still need to be done to protect other people from witnessing what the slaves went through in the past. People should learn to co exist with one another so that racial and other forms of discrimination are eliminated.

It should be the role of the modern day governments to pass strict laws that makes it illegal for a person to discriminate the other on basis of race, religion, political or gender. This is a move that will go a long way in making sure that the world is a peaceful place to live in.

Reference List

Garfield, D. (1996). Harriet Jacobs and Incidents in the life of a slave girl: new critical Essays. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yellin, J. (2004). Harriet Jacobs: A Life. New York: Basic Civitas Books.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, February 14). Slavery Role in the American Literature. https://ivypanda.com/essays/slavery-role-in-the-american-literature/

"Slavery Role in the American Literature." IvyPanda , 14 Feb. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/slavery-role-in-the-american-literature/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Slavery Role in the American Literature'. 14 February.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Slavery Role in the American Literature." February 14, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/slavery-role-in-the-american-literature/.

1. IvyPanda . "Slavery Role in the American Literature." February 14, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/slavery-role-in-the-american-literature/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Slavery Role in the American Literature." February 14, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/slavery-role-in-the-american-literature/.

- Harriet Beecher Stowe: Opinions and Thoughts

- "Uncle Tom’s Cabin" by Harriet Beecher Stowe

- Role of Women in "Uncle Tom’s Cabin" by Harriet Beecher Stowe

- Was Stowe a Racist in Her Presentation of African Americans in "Uncle Tom’s Cabin"?

- Harriet Beecher Stowe in the Abolition Movement

- Christian Thought in Stowe’s "Uncle Tom’s Cabin"

- Harriet Ann Jacobs’ Narrative

- Portraits of Escaping Slaves Portrayed as Heroic Fugitives

- Racist Presentation of African Americans in "Uncle Tom’s Cabin"

- Critical Analysis of "Uncle Tom’s Cabin"

- Consumerism in the 1960s in “A&;P“ by John Updike

- “The Day of the Locust” Novel by Nathanael West

- “Ask the Dust” Novel by John Fante

- Slavery in "Flight to Canada" Novel by Ishmael Reed

- "Mumbo Jumbo" Afro-American Novel by Ishmael Reed

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.2: The Slavery Controversy and Abolitionist Literature

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 134196

Learning Objectives

After completing this section, you should be able to:

- Summarize the ways that Africans resisted slavery, the impact of that resistance, who was involved in anti-slavery movements, and the arguments they used to advance their cause

- Explain how slavery related to ideas of manifest destiny, the Western expansion, and the Mexican-American War

- Define the key abolitionist arguments of Garrison, Walker, and Mott, and distinguish their approaches from one another

- List the chief features of the slave narrative as a literary genre

- Distinguish similarities and differences between Douglass' and Jacobs' slave narratives, analyzing the roles gender and genre play in those distinctions

- Identify key turning points in Douglass' account of achieving freedom

- Outline the ways that Jacobs appealed specifically to women readers in the North

- Describe Stowe's appeal to her readers in Uncle Tom's Cabin and formulate hypotheses to explain its incredible popularity despite stereotypical representations of women and African Americans

- Analyze the role of Christianity, motherhood, and racialist representations in the antislavery arguments of Uncle Tom's Cabin

Slavery and the Debate over Abolition

Resistance and abolition.

Consider these questions as you read: In what ways did Africans resist slavery, and what was the impact of this resistance? Who was involved in anti-slavery movements, and how did the sentiment spread? What arguments did anti-slavery movements use to advance their cause?

Resistance to slavery came in many forms, all of which contributed to the abolition of slavery as an institution in the Americas in the second half of the nineteenth century. There were two main arms of resistance: that of slaves themselves and that of abolitionists, whose calls for the end of slavery became louder and more forceful beginning in the last two decades of the eighteenth century.

Africans resisted slavery in several ways. First, they adopted defensive measures in their own villages to elude capture by slavers. Second, they launched attacks on the crews aboard slave ships. Slavers' reports document over 400 such attacks, but scholars believe there were many more. Third, once ashore, Africans ran away, sometimes establishing Maroon communities. Maroon communities, such as those in Suriname and Jamaica, and the Republic of Palmares in Brazil, warred with white settlers throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Fourth, African slaves revolted on the very lands on which they were enslaved. The first slave revolt in the Americas we know of occurred in 1522 on the island of Hispaniola. This revolt, like most that would follow in the next 250 years, was quickly put down. During the late eighteenth century, however, the Americas saw an increase in slave revolts, especially in the French Caribbean. The French and Haitian Revolutions, which began in 1789 and 1791 respectively, largely inspired these revolts. Both revolutions were fought in the name of natural rights and the equality of men, ideas not lost on those who remained enslaved in the French colonial world. The French revolutionary government even abolished slavery in its colonies, although this did not last for very long, as slavery was soon reinstated during the reign of Napoleon. Slave revolts continued into the nineteenth century in British and Spanish Caribbean colonies. A revolt on the British-controlled island of Barbados in 1816 involved 20,000 slaves from over seventy plantations.

In 1831, a slave revolt in Virginia led by Nat Turner, although small in comparison with other slave revolts of the same period, became a symbol for slaveholders in the U.S. of the danger posed by abolition. For others, however, two decades of increased slave unrest supported calls for the end of slavery. These were the individuals involved in anti-slavery movements, which began gaining substantial ground with public opinion beginning in the 1780s. The anti-slavery movement was perhaps strongest in Britain, where member of Parliament William Wilberforce led anti-slavery campaigns from the 1780s onwards. Evangelical Protestant Christians joined him. These campaigns led to thousands of petitions to end slavery between the 1780s and 1830s. The slave trade was anti-slavery's first target and in 1787 the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was established in Britain. Wilberforce and evangelical Protestants saw slavery and slaveholders as evil. So, too, did the Quakers (or the Society of Friends). On both sides of the Atlantic, Quakers attacked slavery as immoral and prohibited their members from owning slaves or being involved in any part of the slave trade.

In addition to these moral attacks on slavery, Enlightenment thinkers attacked slavery on philosophical grounds. French Enlightenment philosophers such as Montesquieu argued that slavery went against the natural rights of man. During the French Revolution, members of the Society of the Friends of Blacks, which originated among Enlightenment thinkers, joined with free blacks from the Caribbean colonies living in France, who organized the Society of Colored Citizens, to advocate for equal rights for free people of color and the end of slavery. The anti-slavery movement scored a victory in 1807 when the United States and then Britain signed bills to end their nations' involvement in the slave trade. Many in the anti-slavery movement believed this was the first step to abolishing slavery as an institution.

The Library of Congress: "Abolition, Anti-Slavery Movements, and the Rise of the Sectional Controversy"

To better understand abolition, antislavery movements, and the rise of the sectional controversy, read this text, which provides a short overview of abolition with related images from the Library of Congress.

Black and white abolitionists in the first half of the nineteenth century waged a biracial assault against slavery. Their efforts proved to be extremely effective. Abolitionists focused attention on slavery and made it difficult to ignore. They heightened the rift that had threatened to destroy the unity of the nation even as early as the Constitutional Convention.

Although some Quakers were slaveholders, members of that religious group were among the earliest to protest the African slave trade, the perpetual bondage of its captives, and the practice of separating enslaved family members by sale to different masters.

As the nineteenth century progressed, many abolitionists united to form numerous antislavery societies. These groups sent petitions with thousands of signatures to Congress, held abolition meetings and conferences, boycotted products made with slave labor, printed mountains of literature, and gave innumerable speeches for their cause. Individual abolitionists sometimes advocated violent means for bringing slavery to an end.

Although black and white abolitionists often worked together, by the 1840s they differed in philosophy and method. While many white abolitionists focused only on slavery, black Americans tended to couple anti-slavery activities with demands for racial equality and justice.

Anti-Slavery Activists

Christian arguments against slavery.

Benjamin Lay, a Quaker who saw slavery as a "notorious sin", addresses this 1737 volume to those who "pretend to lay claim to the pure and holy Christian religion". Although some Quakers held slaves, no religious group was more outspoken against slavery from the seventeenth century until slavery's demise. Quaker petitions on behalf of the emancipation of African Americans flowed into colonial legislatures and later to the United States Congress.

Plea for the Suppression of the Slave Trade

In this plea for the abolition of the slave trade, Anthony Benezet, a Quaker of French Huguenot descent, pointed out that if buyers did not demand slaves, the supply would end. "Without purchasers", he argued, "there would be no trade; and consequently every purchaser as he encourages the trade, becomes partaker in the guilt of it". He contended that guilt existed on both sides of the Atlantic. There are Africans, he alleged, "who will sell their own children, kindred, or neighbors". Benezet also used the biblical maxim, "Do unto others as you would have them do unto you", to justify ending slavery. Insisting that emancipation alone would not solve the problems of people of color, Benezet opened schools to prepare them for more productive lives.

The Conflict Between Christianity and Slavery

Connecticut theologian Jonathan Edwards, born 1745, echoes Benezet's use of the Golden Rule as well as the natural rights arguments of the Revolutionary era to justify the abolition of slavery. In this printed version of his 1791 sermon to a local anti-slavery group, he notes the progress toward abolition in the North and predicts that through vigilant efforts slavery would be extinguished in the next fifty years.

Sojourner Truth

Abolitionist and women's rights advocate Sojourner Truth was enslaved in New York until she was an adult. Born Isabella Baumfree around the turn of the nineteenth century, her first language was Dutch. Owned by a series of masters, she was freed in 1827 by the New York Gradual Abolition Act and worked as a domestic. In 1843 she believed that she was called by God to travel around the nation--sojourn--and preach the truth of his word. Thus, she believed God gave her the name, Sojourner Truth. One of the ways that she supported her work was selling these calling cards.

Ye wives and ye mothers, your influence extend-- Ye sisters, ye daughters, the helpless defend-- The strong ties are severed for one crime alone, Possessing a colour less fair than your own.

Abolitionists understood the power of pictorial representations in drawing support for the cause of emancipation. As white and black women became more active in the 1830s as lecturers, petitioners, and meeting organizers, variations of this female supplicant motif, appealing for interracial sisterhood, appeared in newspapers, broadsides, and handicraft goods sold at fund-raising fairs.

Harriet Tubman--the Moses of Her People

The quote below, echoing Patrick Henry, is from this biography of underground railroad conductor Harriet Tubman:

Harriet was now left alone, . . . She turned her face toward the north, and fixing her eyes on the guiding star, and committing her way unto the Lord, she started again upon her long, lonely journey. She believed that there were one or two things she had a right to, liberty or death.

After making her own escape, Tubman returned to the South nineteen times to bring over three hundred fugitives to safety, including her own aged parents.

In a handwritten note on the title page of this book, Susan B. Anthony, who was an abolitionist as well as a suffragist, referred to Tubman as a "most wonderful woman".

Increasing Tide of Anti-slavery Organizations

In 1833, sixty abolitionist leaders from ten states met in Philadelphia to create a national organization to bring about immediate emancipation of all slaves. The American Anti-slavery Society elected officers and adopted a constitution and declaration. Drafted by William Lloyd Garrison, the declaration pledged its members to work for emancipation through non-violent actions of "moral suasion", or "the overthrow of prejudice by the power of love". The society encouraged public lectures, publications, civil disobedience, and the boycott of cotton and other slave-manufactured products.

William Lloyd Garrison--Abolitionist Strategies

White abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, born in 1805, had a particular fondness for poetry, which he believed to be "naturally and instinctively on the side of liberty". He used verse as a vehicle for enhancing anti-slavery sentiment. Garrison collected his work in Sonnets and Other Poems (1843).

During the 1840s, abolitionist societies used song to stir up enthusiasm at their meetings. To make songs easier to learn, new words were set to familiar tunes. This song by William Lloyd Garrison has six stanzas set to the tune of "Auld Lang Syne".

Popularizing Anti-Slavery Sentiment

Slave stealer branded.

Massachusetts sea captain Jonathan Walker, born in 1790, was apprehended off the coast of Florida for attempting to carry slaves who were members of his church denomination to freedom in the Bahamas in 1844. He was jailed for more than a year and branded with the letters "S.S." for slave stealer. The abolitionist poet John Greenleaf Whittier immortalized Walker's deed in this often reprinted verse: "Then lift that manly right hand, bold ploughman of the wave! Its branded palm shall prophesy, 'Salvation to the Slave!'"

Abolitionist Songsters

George W. Clark's, The Liberty Minstrel, is an exception among songsters in having music as well as words. "Minstrel" in the title has its earlier meaning of "wandering singer". Clark, a white musician, wrote some of the music himself; most of it, however, consists of well-known melodies to which anti-slavery words have been written. The book is open to a page containing lyrics to the tune of "Near the Lake", which appeared earlier in this exhibit (section 1, item 22) as "Long Time Ago". Note that there is an anti-slavery poem on the right-hand page. Like many songsters, The Liberty Minstrel contains an occasional poem.

Music was one of the most powerful weapons of the abolitionists. In 1848, William Wells Brown, abolitionist and former slave, published The Anti-Slavery Harp , "a collection of songs for anti-slavery meetings", which contains songs and occasional poems. The Anti-Slavery Harp is in the format of a "songster"--giving the lyrics and indicating the tunes to which they are to be sung, but with no music. The book is open to the pages containing lyrics to the tune of the "Marseillaise", the French national anthem, which to 19th-century Americans symbolized the determination to bring about freedom, by force if necessary.

Suffer the Children

This abolitionist tract, distributed by the Sunday School Union, uses actual life stories about slave children separated from their parents or mistreated by their masters to excite the sympathy of free children. Vivid illustrations help to reinforce the message that black children should have the same rights as white children, and that holding humans as property is "a sin against God".

Fugitive Slave Law

North to canada.

In the wake of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, which forced Northern law enforcement officers to aid in the recapture of runaways, more than ten thousand fugitive slaves swelled the flood of those fleeing to Canada. The Colonial Church and School Society established mission schools in western Canada, particularly for children of fugitive slaves but open to all. The school's Mistress Williams notes that their success proves the "feasibility of educating together white and colored children". While primarily focusing on spiritual and secular educational operations, the report reproduces letters of thanks for food, clothing, shoes, and books sent from England. This early photograph accompanied one such letter to the children of St. Matthew's School, Bristol.

The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850

This controversial law allowed slave-hunters to seize alleged fugitive slaves without due process of law and prohibited anyone from aiding escaped fugitives or obstructing their recovery. Because it was often presumed that a black person was a slave, the law threatened the safety of all blacks, slave and free, and forced many Northerners to become more defiant in their support of fugitives. S. M. Africanus presents objections in prose and verse to justify noncompliance with this law.

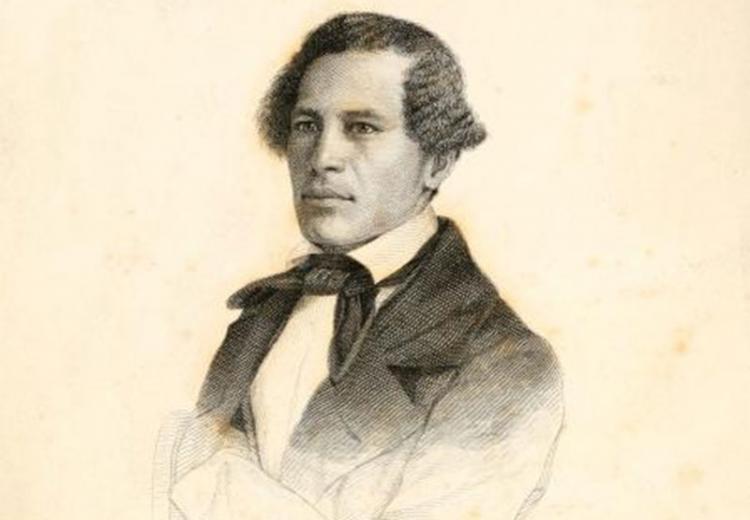

Anthony Burns--Capture of A Fugitive Slave

This is a portrait of fugitive slave Anthony Burns, whose arrest and trial in Boston under the provisions of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 incited riots and protests by white and black abolitionists and citizens of Boston in the spring of 1854. The portrait is surrounded by scenes from his life, including his sale on the auction block, escape from Richmond, Virginia, capture and imprisonment in Boston, and his return to a vessel to transport him to the South. Within a year after his capture, abolitionists were able to raise enough money to purchase Burns's freedom.

Growing Sectionalism

Antebellum map showing the free and slave states.

The growing sectionalism that was dividing the nation during the late antebellum years is documented graphically with this political map of the United States, published in 1856. Designed to portray and compare the areas of free and slave states, it also includes tables of statistics for each of the states from the 1850 census, the results of the 1852 presidential election, congressional representation by state, and the number of slaves held by owners. The map is also embellished with portraits of John C. Fremont and William L. Dayton, the 1856 presidential and vice-presidential candidates of the newly organized Republican Party, which advocated an anti-slavery platform.

Distribution of Slaves

Although the Southern states were known collectively as the "slave states" by the end of the Antebellum Period, this map provides statistical evidence to demonstrate that slaves were not evenly distributed throughout each state or the region as a whole. Using data from the 1860 census, the map shows, by county, the percentage of slave population to the whole population. Tables also list population and area for both Southern and Northern states, while an inset map shows the extent of cotton, rice, and sugar cultivation. Another version of this map was published with Daniel Lord's The Effect of Secession upon the Commercial Relations between the North and South, and upon Each Section (New York, 1861), a series of articles reprinted from The New York Times.

Militant Abolition

John brown's raid.

More than twenty years after the militant abolitionist John Brown had consecrated his life to the destruction of slavery, his crusade ended in October 1859 with his ill-fated attempt to seize the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry in western Virginia. He hoped to take the weapons from the arsenal and arm the slaves, who would then overthrow their masters and establish a free state for themselves.

Convicted of treason and sentenced to death, Brown maintained to the end that he intended only to free the slaves, not to incite insurrection. His zeal, courage, and willingness to die for the slaves made him a martyr and a bellwether of the violence soon to consume the country during the Civil War.

Frederick Douglass on John Brown

The friendship of Frederick Douglass and John Brown began in 1848, when Douglass visited Brown's home in Springfield, Massachusetts. Brown confided to Douglass his ambitious scheme to free the slaves. Over the next eleven years, Brown sought Douglass's counsel and support.

In August 1859 Brown made a final plea to Douglass to join the raid on Harpers Ferry. Douglass refused. After Brown's capture, federal marshals issued a warrant for Douglass's arrest as an accomplice. Douglass fled abroad. When he returned five months later to mourn the death of his youngest daughter Annie, he had been exonerated. Douglass wrote this lecture as a tribute to "a hero and martyr in the cause of liberty".

"The Book That Made This Great War"

Harriet beecher stowe's mighty pen.

Harriet Beecher Stowe is best remembered as the author of Uncle Tom's Cabin , her first novel, published as a serial in 1851 and then in book form in 1852. This book infuriated Southerners. It focused on the cruelties of slavery--particularly the separation of family members--and brought instant acclaim to Stowe. After its publication, Stowe traveled throughout the United States and Europe speaking against slavery. She reported that upon meeting President Lincoln, he remarked, "So you're the little woman who wrote the book that made this great war".

Uncle Tom's Cabin--Theatrical Productions

This poster for a production of Uncle Tom's Cabin features the Garden City Quartette under the direction of Tom Dailey and George W. Goodhart. Many stage productions of Harriet Beecher Stowe's famous novel have been performed in various parts of the country since Uncle Tom's Cabin was first published as a serial in 1851. Although the major actors were usually white, people of color were sometimes part of the cast. African American performers were often allowed only stereotypical roles--if any--in productions by major companies.

Narratives by fugitive slaves before the Civil War and by former slaves in the postbellum era are essential to the study of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century American history and literature, especially as they relate to the eleven states of the Old Confederacy, an area that included approximately one third of the population of the United States at the time when slave narratives were most widely read. As historical sources, slave narratives document slave life primarily in the American South from the invaluable perspective of first-hand experience. Increasingly in the 1840s and 1850s they reveal the struggles of people of color in the North, as fugitives from the South recorded the disparities between America's ideal of freedom and the reality of racism in the so-called "free states." After the Civil War, former slaves continued to record their experiences under slavery, partly to ensure that the newly-united nation did not forget what had threatened its existence, and partly to affirm the dedication of the ex-slave population to social and economic progress.

From a literary standpoint, the autobiographical narratives of former slaves comprise one of the most extensive and influential traditions in African American literature and culture. Until the Depression era slave narratives outnumbered novels written by African Americans. Some of the classic texts of American literature, including the two most influential nineteenth-century American novels, Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852) and Mark Twain 's Huckleberry Finn (1884), and such prize-winning contemporary novels as William Styron's The Confessions of Nat Turner (1967), and Toni Morrison's Beloved (1987), bear the direct influence of the slave narrative. Some of the most important revisionist scholarship in the historical study of American slavery in the last forty years has marshaled the slave narratives as key testimony. Slave narratives and their fictional descendants have played a major role in national debates about slavery, freedom, and American identity that have challenged the conscience and the historical consciousness of the United States ever since its founding.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, slave narratives were an important means of opening a dialogue between blacks and whites about slavery and freedom. The most influential slave narratives of the antebellum era were designed to enlighten white readers about both the realities of slavery as an institution and the humanity of black people as individuals deserving of full human rights. Although often dismissed as mere antislavery propaganda, the widespread consumption of slave narratives in the nineteenth-century U.S. and Great Britain and their continuing prominence in literature and historical curricula in American universities today testify to the power of these texts, then and now, to provoke reflection and debate among their readers, particularly on questions of race, social justice, and the meaning of freedom.

During the 350-year history of the transatlantic slave trade, Europeans made more than 54,000 voyages to and from Africa to send by force at least ten to twelve million Africans to the Americas. Scholars estimate that close to 400,000 Africans were sold into slavery in North America, the large majority ending up in the American South.

In the antebellum South, slavery provided the economic foundation that supported the dominant planter ruling class. Under slavery the structure of white supremacy was hierarchical and patriarchal, resting on male privilege and masculinist honor, entrenched economic power, and raw force. Black people necessarily developed their sense of identity, family relations, communal values, religion, and to an impressive extent their cultural autonomy by exploiting contradictions and opportunities within a complex fabric of paternalistic give-and-take. The working relationships and sometimes tacit expectations and obligations between slave and slaveholder made possible a functional, and in some cases highly profitable, economic system. Despite the exploitativeness and oppression of this system, slaves emerge in numerous antebellum slave narratives as actively, sometimes aggressively, in search of freedom, whether in the context of everyday speech and action or through covert and overt means of resistance.

Defeat in the Civil War severely destabilized slavery-based social, political, and economic hierarchies, demanding in some cases that white southerners develop new ones. After the Civil War, the southern ruling class was compelled to adapt to new exigencies of race relations and a restructured, as well as reconstructing, economic system. For African Americans, the end of slavery brought hope for unprecedented control of their own lives and economic prospects. After Emancipation, however, most black southerners found themselves steadily drawn into an exploitative sharecropping system that effectively prohibited their becoming property owners with a chance to claim their share of the American Dream. Unlike many poor whites who also found themselves under the thumb of white landowners, the rural black masses in the post-Reconstruction South were gradually subjected to a cradle-to-grave segregation regime designed not simply to separate the races but to create a permanent laboring underclass different in degree but not fundamentally in kind from the slave population of the antebellum era. By the turn of the century segregation had robbed black Southerners of their political rights as well as their economic opportunity and social mobility.

As historical documents, slave narratives chronicle the evolution of white supremacy in the South from eighteenth-century slavery through early twentieth-century segregation and disfranchisement. As autobiography these narratives give voice to generations of black people who, despite being written off by white southern literature, still found a way to bequeath a literary legacy of enormous collective significance to the South and the United States. Expected to concentrate primarily on eye-witness accounts of slavery, many slave narrators become I-witnesses as well, revealing their struggles, sorrows, aspirations, and triumphs in compellingly personal story-telling. Usually the antebellum slave narrator portrays slavery as a condition of extreme physical, intellectual, emotional, and spiritual deprivation, a kind of hell on earth. Precipitating the narrator's decision to escape is some sort of personal crisis, such as the sale of a loved one or a dark night of the soul in which hope contends with despair for the spirit of the slave. Impelled by faith in God and a commitment to liberty and human dignity comparable (the slave narrative often stresses) to that of America's Founding Fathers, the slave undertakes an arduous quest for freedom that climaxes in his or her arrival in the North. In many antebellum narratives, the attainment of freedom is signaled not simply by reaching the free states, but by renaming oneself and dedicating one's future to antislavery activism.

Advertised in the abolitionist press and sold at antislavery meetings throughout the English-speaking world, a significant number of antebellum slave narratives went through multiple editions and sold in the tens of thousands. This popularity was not solely attributable to the publicity the narratives received from the antislavery movement. Readers could see that, as one reviewer put it in 1849, "the slave who endeavors to recover his freedom is associating with himself no small part of the romance of the time." Selling in the tens of thousands, the most popular antebellum narratives by writers such as Frederick Douglass , William Wells Brown , and Harriet Jacobs , stressed how African Americans survived in slavery, making a way out of no way, oftentimes subtly resisting exploitation, occasionally fighting back and escaping in search of better prospects elsewhere in the North, the Midwest, Canada, or Europe. Not surprisingly, in their own era and in ours, the most memorable of these narratives evoke the national myth of the American individual's quest for freedom and for a society based on "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness."

Slave narrators such as Douglass, Brown, and Jacobs wrote with a keen sense of their regional identity as southern expatriates (the forerunners, quite literally, of more famous literary southerners in the twentieth century who left the South to write in the North). Knowing that the land of their birth had produced the likes of George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, southern-born slave narrators were often keen to contrast the lofty human rights ideology of Jefferson's "Declaration of Independence" with his real-world status as a slaveholder. While the autobiographies of the men of power and privilege in the nineteenth-century South are not read widely today, the slave narrative's focus on the conflict between alienated individuals and the oppressive social order of the Old South has spurred the re-evaluation of many hitherto submerged southern autobiographical and narrative forms, including the diaries of white women.

In most post-Emancipation slave narratives slavery is depicted as a kind of crucible in which the resilience, industry, and ingenuity of the slave was tested and ultimately validated. Thus the slave narrative argued the readiness of the freedman and freedwoman for full participation in the post-Civil War social and economic order. The biggest selling of the late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century slave narratives was Booker T. Washington 's Up from Slavery (1901), a classic American success story. Because Up from Slavery extolled black progress and interracial cooperation since emancipation, it won a much greater hearing from southern whites than was accorded those former slaves whose autobiographies detailed the legacy of injustices burdening blacks in the postwar South. One reason to create a complete collection of post-Civil War ex-slave narratives is to give voice to the many former slaves who shared neither Washington's comparatively benign assessment of slavery and segregation nor his rosy view of the future of African Americans in the South. Another reason to extend the slave narrative collection well into the twentieth century is to give black women's slave narratives, the preponderance of which were published after 1865, full representation as contributions to the tradition.

Slave and ex-slave narratives are important not only for what they tell us about African American history and literature, but also because they reveal to us the complexities of the dialogue between whites and blacks in this country in the last two centuries, particularly for African Americans. This dialogue is implicit in the very structure of the antebellum slave narrative, which generally centers on an African American's narrative but is prefaced by a white-authored text and often is appended by white authenticating documents, such as letters of reference attesting to the character and reliability of the slave narrator himself or herself. Some slave narratives elicited replies from whites that were published in subsequent editions of the narrative (the second, Dublin edition of Frederick Douglass's 1845 Narrative is a case in point). Other slave narratives, such as The Confessions of Nat Turner (1831), gave rise to novels implicitly or explicitly intended to defend the myth of the South, such as John Pendleton Kennedy 's Swallow Barn (1832), traditionally regarded as the first important plantation novel. Both intra-textually and extra-textually, therefore, the slave narrative from the early nineteenth century onward was a vehicle for dialogue over slavery and racial issues between whites and blacks in the North and the South. When reactionary white southern writers and regional boosters of the 1880s and 1890s decanted myths of slavery and the moonlight-and-magnolias plantation to a nostalgic white northern readership, the narratives of former slaves were one of the few resources that readers of the late nineteenth century could examine to get a reliable, first-hand portrayal of what slavery had actually been like.

Modern black autobiographies such as Richard Wright's Black Boy (1945) and The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965) testify to the influence of the slave narrative on the first-person writing of post-World War II African Americans. Beginning with Margaret Walker's Jubilee (1966) and extending through such contemporary novels as Ernest J. Gaines's The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman (1971), Sherley Ann Williams's Dessa Rose (1986), Toni Morrison's Beloved (1987), and Charles Johnson's Middle Passage (1990), the "neo-slave narrative" has become one of the most widely read and discussed forms of African American literature. These autobiographical and fictional descendants of the slave narrative confirm the continuing importance and vitality of its legacy: to probe the origins of psychological as well as social oppression and to critique the meaning of freedom for black and white Americans alike from the founding of the United States to the present day.

ENGL405: The American Renaissance

Essay on the slave narrative.

The slave narrative can broadly be defined as any first-person account of the experience of being enslaved. Read this introductory essay on the slave narrative as a literary genre.

No experience of enslavement has been as fully recorded as that of African Americans in the United States in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Despite the large numbers of first-person accounts of slavery in the United States – hundreds from the early-nineteenth century (e.g. pamphlet-length documents and numerous book-length texts), significant numbers from the post-Civil War era, and thousands collected through the WPA during the Depression – these resources were commonly dismissed as merely abolitionist propaganda or skewed memories until the late-twentieth century. Over the past half century, however, the slave narrative in its various incarnations has helped reshape our understanding not just of slavery in the U. S. but of American culture and American literature more broadly. At the same time that these narratives are significant for the picture they paint of African-American life and culture (and American life and culture more broadly), they repeatedly emphasize the importance of the individual former slave and his or her struggles against a system that would deny his or her individuality as a human. For the purposes of this class, we will focus on what could be seen as the classic era of the slave narrative, the decades immediately preceding the Civil War when hundreds of such works were produced, including its most popular and most influential individual texts, all part of the larger anti-slavery movement intent on making Americans, especially white Northerners, recognize the true crime of slavery and the essential humanity of those enslaved.

The slave narrative can broadly be defined as any first-person account of the experience of being enslaved. Modern slave narratives, emerging from the transatlantic slave trade of Africans, first appeared in English in the late-eighteenth century with the development of a broad abolitionist movement in Britain. The first slave narratives tended to be short and often focused more on the writer's conversion to Christianity and acceptance of God's grace over the horrors experienced in slavery. The most prominent slave narrative of this period, Olaudah Equiano's The Life of Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, Written by Himself (1789), mirrors this tendency even as it begins to approximate the more focused abolitionism of later narratives. In his narrative, Equiano narrates being kidnapped from his home in Africa and taken to the new world, producing a picture of Africa as a kind of Edenic region being despoiled by European greed. Over the first half of his narrative, he focuses on his experience as a slave, as he serves during the Seven Years' War on board a British privateer, expecting to earn his freedom only to be sold to a new owner in the Caribbean. He escapes the worst treatment in the Caribbean by becoming a valuable sailor for his owner, eventually accumulating enough money to buy his freedom. Unlike in many later slave narratives, however, Equiano's acquisition of freedom does not become the culminating moment of his narrative, as the second half of the narrative continues, describing his adventures (including his participation in an attempt at exploring the North Pole) and his experiences of racism and dangers of being re-enslaved, foregrounding, in the end, his religious conversion and concluding with him making an economic argument for abolitionism. Equiano's narrative reveals the formal instability of the slave narrative at the time, as it draws on several disparate literary traditions, most notably the Protestant conversion narrative, the related captivity narrative, natural history and travel narratives, and picaresque adventure fictions such as Daniel De Foe's Robinson Crusoe .

Over the course of the first decades of the nineteenth century, numerous former slaves produced published accounts of their lives, often through the help of a white amanuensis, but frequently on their own. As anti-slavery sentiment began to become both more wide-spread and more radical in the 1830s, black and white activists began to seek out more first-hand accounts of slavery's cruelties. Accounts written by the former slaves themselves served an important second purpose, providing evidence of the intellectual capacity of African Americans and thus countering claims of their mental inferiority. These dual purposes came together most forcefully, famously, and influentially in Frederick Douglass's The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave, Written by Himself (1845). Douglass had already established himself as a well-known abolitionist lecturer, and, in fact, he produced the narrative largely to counter claims that he had never been a slave. Much of the focus of the narrative, then, is on authenticating his life story, as he provides names and locales and, as often as possible, dates to corroborate his account. The work was immediately quite popular, with seven American and nine British editions appearing over the next five years, and more than 30,000 copies being sold. Douglass's Narrative helped to consolidate the slave narrative as a form, bringing together some of the key thematic and structural elements of earlier narratives into a more unified form, and it thus often serves as representative of the form as a whole. Douglass's Narrative begins with introductory letters from William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips, two of the most prominent white abolitionists of the time. The letters attest to Douglass's truthfulness and to the fact that he wrote the narrative himself, at the same time providing readers with a template of the narrative's chief points. While many slave narratives, especially those published by the authors themselves, did not have such introductory frames, they were common to many of the more widely disseminated, longer works. This prefatory material authorized the text that followed, thus empowering the former slave to tell his or her story, but the apparent necessity of such authorization reinforced the former slave's dependence on white power structures and readership.

Like many slave narratives, Douglass's begins with a simple statement of the fact that he was born, an announcement of his existence as a human being. This standard opening of many slave narratives – "I was born" – announces the existence of the slave as a human. But in what follows, he emphasizes all the ways that the system of slavery attempted to deny that humanity and treat him like an animal, by keeping him ignorant of his birthdate, by separating him from his mother and his family, by leaving him naked and assessing his worth alongside that of farm animals. Douglass thus reinforces Garrison's overarching argument against slavery: slavery's chief crime lies in the fact that it "reduces those who by creation were crowned with glory and honor to a level with four-footed beasts". This point introduces the central rhetorical problematic of Douglass's and most other slave narratives, the need to demonstrate how slavery destroys the humanity of the slaves (and of the slave-owners) while contending for the slaves' fundamental humanity. Douglass, in other words, must at once show how the slaves have been dehumanized while simultaneously humanizing them in the eyes of his readers.

The production of the work itself by the former slave played a central role in this operation. Like many other slave narratives, Douglass's title reinforced that it was "written by himself". In a culture and society that prized literacy as one of the markers of intelligence and within an intellectual tradition that ranked non-literate, non-European cultures as fundamentally inferior, African-American literary production could provide strong evidence of black intelligence, thus rebutting pro-slavery arguments that Africans were intellectually incapable of freedom. That focus on literacy and on writing one's self into existence becomes a central theme of Douglass's and many other slave narratives. Douglass repeatedly recurs to the importance of literacy in his developing desire for freedom and in his actual escape from slavery. He recounts how Sophia Auld began to teach him the alphabet only to be warned by her husband that it was dangerous and worthless to do so, a warning that only spurred Douglass's desire. He then tells us how he used poor white boys in his neighborhood in Baltimore to teach him and how he found an old copy of the The Columbian Orator , a common primer of the time, that he used as his textbook. In describing the impact of the Orator on him, Douglass states that it "gave tongue to interesting thoughts of my own soul which had frequently flashed through my mind, and died away for want of utterance". As such, he seems to suggest that literacy helps to consolidate an innate desire for freedom that slavery and enforced ignorance darkens but cannot destroy.

Foregrounding the importance of literacy, Douglass characterizes the slaves who remain illiterate as living in a darkened world where they have only an inkling of the fundamental wrongs they suffer. He furthers this depiction of how slaves are kept enslaved – but not happy – through his account of his time with the slave-breaker Covey. In this episode, Douglass emphasizes how a combination of work, discipline, mental and emotional manipulation, and violence breaks down even the most resistant slave: "I was broken in body, soul, and spirit. My natural elasticity was crushed, my intellect languished, the disposition to read departed, the cheerful spark that lingered about my eye died; the dark night of slavery closed in upon me; and behold a man transformed into a brute!" Yet he also emphasizes his individual ability to rise above this dehumanization and to violently resist and re-establish his manhood and his humanity when he resists Covey and proclaims his refusal to be a "slave in fact" no matter how long he might remain a "slave in form". Despite all the deprivations of slavery, some innate human desire for freedom remains. It is in convincing his audience of that innate desire and of the importance of defending that desire that Douglass makes his strongest case to his audience.