This website works best with JavaScript switched on. Please enable JavaScript

- Centre Services

- Associate Extranet

- All About Maths

Specifications that use this resource:

- AS and A-level English Literature A 7711; 7712

Example student response and examiner commentary

Below you will find an exemplar student response to a Section B question in the specimen assessment materials, followed by an examiner commentary on the response.

Sample question

'Women characters are presented primarily as those who suffer and endure.'

By comparing two prose texts, explore the extent to which you agree with this statement.

Band 4 response

Stereotypically, women are portrayed as the weaker sex in pre-1900 literature and they often suffer and endure unhappy marriages because of the inequality of the sexes. In post-1900 literature, however, women are shown as more equal and so writers don't focus on their suffering alone but also on the suffering of male characters in relationships. This is true of The Great Gatsby and The Rotters' Club where women do suffer and endure but arguably men are presented as suffering even more.

The Great Gatsby focuses on the main character of Jay Gatsby and his unrequited love for Daisy whereas The Rotters' Club includes many relationships. There are, however, similarities between Gatsby's suffering and that of Benjamin Trotter and Sam Chase, although the outcomes are different, and so this essay will focus on those male characters.

Gatsby's suffering is emphasised by Fitzgerald because he withholds it from the reader to begin with. Fitzgerald suggests Gatsby is successful and popular before we meet him through his house parties where 'champagne was served in glasses bigger than finger bowls' so his lovesickness is a surprise to the reader. We learn, that 'Gatsby bought that house so that Daisy would be just across the bay' and Fitzgerald uses the symbolism of the green light Gatsby can see at the bottom of Daisy's land to show how he is pining for her: 'he stretched out his arms toward the dark water…I could have sworn he was trembling.'

Having loved Daisy from afar for five years, Gatsby engineers afternoon tea at Nick's to reacquaint himself with her and Fitzgerald presents Gatsby as so desperate to impress her that he becomes very nervous with 'trembling fingers' and 'a strained counterfeit of perfect ease'. In the same way, Benjamin is presented as 'anxious' to know whether Cicely still loved him after her stay in America and his 'yearning' and 'nervousness' is 'transparent.' Where we see Gatsby's lovesickness through Nick's narration, Coe gives Benjamin a 36-page sentence to narrate his and his rambling style emphasises how he has suffered through loving Cicely from afar: 'I had tried not to doubt her during that time, but once or twice, it's inevitable I suppose, you find yourself wondering, not about other men, I was never worried about that, but feelings fade, it happens all the time, or so I'm told, or so I've read.'

Having been reunited with their loves, Gatsby and Benjamin are unable to relax and believe that everything will be alright. Although 'consumed with wonder at her presence' in his house, Gatsby is presented as 'running down like an over-wound clock' because 'he had been full of the idea so long, dreamed it right through to the end, waited with his teeth set…at an inconceivable pitch of intensity.' Where Gatsby is obsessed with turning back time to recapture the five years they lost, Benjamin has a 'fear of the past, fear of how the past might have turned out, because we came within a whisker, Cicely and I, of missing each other altogether…and the thought of that, the thought that we might never have reached this point at all, oh, it was almost unbearable, unsupportable.'

The outcomes for Gatsby and Benjamin are, however, very different. By the end of the novel, Cicely and Benjamin are together and Coe effectively expresses Benjamin's relief and joy: 'suddenly it's as if everything refers to me and Cicely, everything is a metaphor for the way we feel, somehow the entire city has become nothing less than a life-size diagram of our hearts'. Gatsby's dream, however, crumbles, Firstly Daisy doesn't enjoy Gatsby's party, which he believed would impress her, and this leads to 'his unutterable depression' where he stops the parties and sack his servants 'so the whole caravansary had fallen in like a card house at the disapproval of her eyes.' Undeterred, however, Gatsby continues to pursue Daisy to the point of humiliation. When Daisy admits to having loved Tom, 'the words seemed to bite physically into Gatsby' but he still takes the blame for Myrtle's death to protect Daisy and then pitifully sits outside Daisy's house until 4 a.m. in a misguided belief he is protecting her from Tom when he is 'watching over nothing.'

Like Gatsby, Sam Chase is humiliated in The Rotter's Club but by his wife's affair with their son's art teacher, Miles Plumb, who seduces Barbara with his academic language. As with Gatsby, this could be seen as a class issue where Plumb is educated and Sam believes he needs to enlarge his vocabulary to win his wife back. Coe amusingly sets Barbara's reading of Plumb's love note against Sam's attempts and failure to master the 'quick and easy crossword.' Barbara is struggling to understand Plumb's compliments such as ''callipygic enchantress, apogee of all that is pulchritudinous in this misbegotten, maculate world'. At the same time, Sam makes mistakes such as: 'It's not exactly Doctor Chicago is it?' and makes such a mess of the crossword that Barbara asks: 'Giving up again?' and 'with just a hint of a taunt in her voice.'

Unlike Gatsby, who loses his confrontation with Tom and so loses Daisy, Sam wins Barbara back after a humorous phone call to Miles Plumb. Coe shows the absurdity of the situation where, feeling that 'he had to meet this man on his own terms,' Sam practises insults to use such as 'you are a temerarious poltroon, a rebarbative mooncalf, a pixilated dunderhead' but when it comes to it Sam can't get the words out. Humiliated and angry with himself, he 'screwed his eyes tight shut, and instinctively, without thinking about it, blew the longest and loudest raspberry he had ever blown in his life', which had the desired effect on Miles Plum.

For Gatsby, however, the ending is more tragic not only because of his death but also because right before he is shot he still hopes he can win Daisy: 'I suppose Daisy'll call too. He looked at me anxiously, as if he hoped I'd corroborate this.' In the end, 'he must have felt that he had…paid a high price for living too long with a single dream'.

Examiner commentary

This is a logical and thorough argument where ideas are presented coherently. There is appropriate use of concepts and terminology and expression is accurate.

The candidate shows a thorough understanding of a range of ways in which meanings are shaped although analysis is often implicit rather than explicit. Discussion is supported purposefully with relevant textual evidence.

The candidate makes the literary presentation of women characters as the primary sufferers relevant to the period in which these texts were written; the focus instead on the suffering of male characters is supported by well-chosen examples.

The candidate makes a number of logical comparisons between the texts and shows an awareness of the wider presentation of characters as suffering and enduring for love.

The candidate engages thoroughly with the debate set up in the question in the focus on the suffering of male characters in these texts and in the discussion of different forms of suffering.

Overall: Coherent and thorough: this response seems to fit the Band 4 descriptors.

This resource is part of the Love through the ages resource package .

Document URL https://www.aqa.org.uk/resources/english/as-and-a-level/english-literature-a/teach/love-through-the-ages-example-answer-and-commentary-3-as-b2

Last updated 16 Dec 2022

Derek Walcott — A-Grade A-Level Literature Essay Example

One of my students completed this essay on Walcott recently for the CIE / Cambridge A-Level Literature Exam Board.

It received a borderline A grade (80%, 20/25) — there are some absolutely brilliant parts of it, and also some aspects which have room for improvement, so I’ve put my mark breakdown and suggestions for how to improve next time at the end of the exemplar too for you to read through. Hope it’s useful!

If you find this resource helpful, you can take a look at the full Walcott poetry course .

I have a lot of Derek Walcott’s poetry analysis, so be sure to check it out too by clicking this link .

THE QUESTION:

Walcott has said that the process of poetry is ‘one of excavation and of self-discovery’. How far do you see this process in his work? In your answer, you should refer in detail to three poems.

Much of Walcott’s poetry displays excavation and self-discovery through the exploration of themes such as nature, the environment and politics. By holding up a mirror to the issues surrounding these themes, Walcott arguably recreates the past and present as a form of excavation. Within his examination he is able to ignite an awareness for the reader, around the issues of slavery, post-colonialism and urbanisation. This awareness arguably awakens the reader to self-discovery, through being informed on the aforementioned issues. Likewise, by speaking of these issues, Walcott himself is also examining his own frustrations and expressing these views through his poetry.

With reference to the poem, ‘Ebb’, Walcott sets out to explore the theme of urbanisation and its harmful effects. The environment takes centre stage and is heavily prominent throughout each stanza. For instance, the first verse of the poem describes the endless cycle of how the earth is scorched and ‘fretted’ upon, how the earth resembles a ‘frayed hide’. The verb, ‘fretted’ refers to how the land has been tampered with and spoiled, and the adjective of ‘frayed’ shows the violent extent to which this has happened. Lastly, the noun, ‘hide’ is used as a metaphor for a heavily lashed animal hide. The use of this visual imagery effectively connotes how human greed disrespects nature. This is arguably because Walcott strongly believed that since the Caribbean islands left the federation and became independent islands like Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago in 1962, and Walcott’s own native island, Saint Lucia in 1979, they all suffered a lack of unity among the Caribbean as a whole. In turn this led islands to be exploited for commercial greed. Another example of this can be found in the line, ‘rainbow-muck’, which again is a metaphor used to describe oil. Of all of the Caribbean Islands, Trinidad and Tobago is renowned for its copious oil supply, yet the island itself appears not to prosper from it. Rather, the wealth generated from it is passed directly into the pockets of other countries. Walcott further criticises the effects of urbanisation by portraying nature as victim with the image of an ‘oil-crippled gull’. Again ‘oil’ is used a symbol of urbanisation and greed, while the adjective of ‘crippled’ represents the damage caused. Through the use of powerful imagery denoting the destruction of nature, the reader is made to feel informed and aware of the issues raised.

In the poem ‘Veranda’ Walcott reconnects the reader to past and vividly turns his spotlight on the plight of slavery and colonialism, by vividly tying a link from past to present through language featuring ghosts and apparitions. From the second stanza a reference is made to slavery with ‘planters’ whose ‘tears’ are described as ‘marketable gum’. The noun, ‘tears’ laments the pain and suffering endured by the slaves to then be exploited as ‘marketable gum’ The noun, ‘gum’ is used as a triviality, something insignificant to be consumed by the masses, to then be spat out tasteless on the ground. This visual image strongly reflects the facelessness of greed and acknowledges the pain and toil to bring about such a triviality. Another ghost described is that of the ‘colonel’ whose heart is ‘hard’ as the ‘Commonwealth’s greenheart’. The colour ‘green’ with reference to the ‘greenheart’ could connote the colour of money and also represent envy for riches. Also the colonel himself, described as ‘hard’ is a fitting image of colonialism, for they enslaved the ‘planters’ without conscience. With this poem Walcott eerily describes the sins of history’s ugly past, presenting them as ghosts either in despair or still power-hungry. Walcott argued that British colonists took away Africa’s history and the colonisers themselves argued that they had no history before their presence there. This is why Walcott frequently opposes colonialism in his poetry, to raise awareness of the wrongs of the past and show that much African culture and history very much exists. Through painting a portrait of the past, Walcott arguably shows the reader the unflinching truth of what came before. This in-turn recreates the past and educates the reader on the former ills of slavery and colonialism.

With reference to the poem, ‘Parades, Parades, Walcott arguably demonstrates his use of excavation by hovering his lens over the theme of Caribbean politics. Consisting of two lengthy stanzas, the first, written in third-person, offers abstract imagery, such as a ‘wide desert’ that ‘no one marches’ and a vast ‘ocean’ of which ‘keels incise’. The adjective of ‘wide’ arguably paints an image of empty sparseness and the second person pronoun, ‘no one’ refers to loss of identity pertaining to the ills of post-colonialism. The verb, ‘marches’ could also symbolise a stagnant lack of progress for the Caribbean as a whole. The noun, ‘ocean’ refers to beautiful Caribbean beaches, only to then be ‘incise’(d) by the luxury liners filled with indulgent tourists. Walcott also cites the politicians who ‘plod’ devoid of ‘imagination’. Again, the active verb of ‘plod’ connotes the sluggish progress made to better the Caribbean and the abstract noun, ‘imagination’ paints the politician as dull and backward thinking. The second stanza then shifts tonally with a volta, and also to a first person plural, addressing the Caribbean locals, belonging to the parade. Walcott questions why they should have propaganda ‘drummed into their minds’ and why they should be made to feel ‘shy’ and ‘bewildered’. The stative verb of ‘drummed’ portrays the idea that people have been force-fed political ideas which do not hold their best interests in mind. The abstract noun ‘shy’ also connotes that they have been led astray and exploited. Walcott clearly demonstrates his ideas about ineffective politics by confronting the issues and in turn dismantling them in order to present them in a new light. This arguably informs the reader of the political injustice and also offers a sounding board for Walcott himself to air his frustrations.

While it could be argued that Walcott’s poetry doesn’t show evidence of the excavation process or self-discovery, owing to the sometimes abstract and esoteric manner in which he presents his work, there appears to be clear evidence pointing to the opposite. With the cynical and retrospective tone that seems to dominate his poetry, there appears to be compelling evidence that he is shedding light on the themes of politics, slavery and post-colonialism, by confronting the ills they caused, and in turn allowing the audience, and himself to re-discover the toil they have brought about.

GRADING (CIE Cambridge Mark Scheme)

Band 2 20/25 80% Borderline A Grade

Evidence of proficiency in selecting relevant knowledge to address the question with precise and integrated direct references to the text and supporting quotation. There may be evidence of awareness of the contexts in which the literary works studied were written and understood. U Evidence of intelligent understanding of ways in which writers’ choices of structure, form and language shape meanings, with analysis and appreciation of literary methods, effects and contexts.

P Evidence of personal response to the texts, relevant to the question, supported from the text, some originality of thought, straightforward and vigorously articulated, perhaps, rather than penetrating and subtle.

C Expression confident, with some complex ideas expressed with some fluency. Structure is sound. Literary arguments will be coherent, with progression of ideas through clearly linked paragraphs.

O Considers varying views and argues a case with support from the text. – This is the main one you’re lacking in, you don’t argue a case clearly or consider varying views .

HOW TO IMPROVE:

- Make sure to address the question argumentatively or discursively (depending on the type of question) — rather than each paragraph is about a poem, make it about a point that answers the question, all linked together with a clear thesis

- Alternative interpretations / critical theories — use these to develop your analysis further and achieve greater sensitivity of interpretation

- Needs more specific, detailed use of contextual ideas

- More structure/form points — good on language

Thanks for reading! If you found this resource helpful, you can take a look at the full Walcott poetry course .

Related Posts

The Theme of Morality in To Kill A Mockingbird

Unseen Poetry Exam Practice – Spring

To Kill A Mockingbird Essay Writing – PEE Breakdown

Emily Dickinson A Level Exam Questions

Poem Analysis: Sonnet 116 by William Shakespeare

An Inspector Calls – Official AQA Exam Questions

The Dolls House by Katherine Mansfield: Summary + Analysis

An Occurrence At Owl Creek Bridge: Stories of Ourselves:

How to Get Started with Narrative Writing

Robert Frost’s Life and Poetic Career

© Copyright Scrbbly 2022

- UCAS Guide Home >

- A-Level English Literature

How to Write an A-Level English Literature Essay

Writing an A-level English Literature essay is like creating a masterpiece. It’s a skill that can make a big difference in your academic adventure.

In this article, we will explore the world of literary analysis in an easy-to-follow way. We’ll show you how to organise your thoughts, analyse texts, and make strong arguments.

The Basics of Crafting A-Level English Literature Essays

Understanding the Assignment: Decoding Essay Prompts

Writing begins with understanding. When faced with an essay prompt, dissect it carefully. Identify keywords and phrases to grasp what’s expected. Pay attention to verbs like “analyse,” “discuss,” or “evaluate.” These guide your approach. For instance, if asked to analyse, delve into the how and why of a literary element.

Essay Structure: Building a Solid Foundation

The structure is the backbone of a great essay. Start with a clear introduction that introduces your topic and thesis. The body paragraphs should each focus on a specific aspect, supporting your thesis. Don’t forget topic sentences—they guide readers. Finally, wrap it up with a concise conclusion that reinforces your main points.

Thesis Statements: Crafting Clear and Powerful Arguments

Your thesis is your essay’s compass. Craft a brief statement conveying your main argument. It should be specific, not vague. Use it as a roadmap for your essay, ensuring every paragraph aligns with and supports it. A strong thesis sets the tone for an impactful essay, giving your reader a clear sense of what to expect.

Exploring PEDAL for Better A-Level English Essays

Going beyond PEE to PEDAL ensures a holistic approach, hitting the additional elements crucial for A-Level success. This structure delves into close analysis, explains both the device and the quote, and concludes with a contextual link.

Below are some examples to illustrate how PEDAL can enhance your essay:

Clearly state your main idea.

Example: “In this paragraph, we explore the central theme of love in Shakespeare’s ‘Romeo and Juliet.'”

Pull relevant quotes from the text.

Example: “Citing Juliet’s line, ‘My only love sprung from my only hate,’ highlights the conflict between love and family loyalty.”

Identify a literary technique in the evidence.

Example: “Analysing the metaphor of ‘love sprung from hate,’ we unveil Shakespeare’s use of contrast to emphasise the intensity of emotions.”

Break down the meaning of the evidence.

Example: “Zooming in on the words ‘love’ and ‘hate,’ we dissect their individual meanings, emphasising the emotional complexity of the characters.”

Link to Context:

Connect your point to broader contexts.

Example: “Linking this theme to the societal norms of the Elizabethan era adds depth, revealing how Shakespeare challenges prevailing beliefs about love and family.”

Navigating the World of Literary Analysis

Breaking Down Literary Elements: Characters, Plot, and Themes

Literary analysis is about dissecting a text’s components. Characters, plot, and themes are key players. Explore how characters develop, influence the narrative, and represent broader ideas. Map out the plot’s structure—introduction, rising action, climax, and resolution. Themes, the underlying messages, offer insight into the author’s intent. Pinpointing these elements enriches your analysis.

Effective Text Analysis: Uncovering Hidden Meanings

Go beyond the surface. Effective analysis uncovers hidden layers. Consider symbolism, metaphors, and imagery. Ask questions: What does a symbol represent? How does a metaphor enhance meaning? Why was a particular image chosen? Context is crucial. Connect these literary devices to the broader narrative, revealing the author’s nuanced intentions.

Incorporating Critical Perspectives: Adding Depth to Your Essays

Elevate your analysis by considering various perspectives. Literary criticism opens new doors. Explore historical, cultural, or feminist viewpoints. Delve into how different critics interpret the text. This depth showcases a nuanced understanding, demonstrating your engagement with broader conversations in the literary realm. Incorporating these perspectives enriches your analysis, setting your essay apart.

Secrets to Compelling Essays

Structuring your ideas: creating coherent and flowing essays.

Structure is the roadmap readers follow. Start with a captivating introduction that sets the stage. Each paragraph should have a clear focus, connected by smooth transitions. Use topic sentences to guide readers through your ideas. Aim for coherence—each sentence should logically follow the previous one. This ensures your essay flows seamlessly, making it engaging and easy to follow.

Presenting Compelling Arguments: Backing Up Your Points

Compelling arguments rest on solid evidence. Support your ideas with examples from the text. Quote relevant passages to reinforce your points. Be specific—show how the evidence directly relates to your argument. Avoid generalisations. Strong arguments convince the reader of your perspective, making your essay persuasive and impactful.

The Power of Language: Writing with Clarity and Precision

Clarity is key in essay writing. Choose words carefully to convey your ideas precisely. Avoid unnecessary complexity—simple language is often more effective. Proofread to eliminate ambiguity and ensure clarity. Precision in language enhances the reader’s understanding and allows your ideas to shine. Crafting your essay with care elevates the overall quality, leaving a lasting impression.

Mastering A-level English Literature essays unlocks academic success. Armed with a solid structure, nuanced literary analysis, and compelling arguments, your essays will stand out. Transform your writing from good to exceptional.

For personalised guidance, join Study Mind’s A-Level English Literature tutors . Elevate your understanding and excel in your literary pursuits. Enrich your learning journey today!

How long should my A-level English Literature essay be, and does word count matter?

While word count can vary, aim for quality over quantity. Typically, essays range from 1,200 to 1,500 words. Focus on expressing your ideas coherently rather than meeting a specific word count. Ensure each word contributes meaningfully to your analysis for a concise and impactful essay.

Is it acceptable to include personal opinions in my literature essay?

While it’s essential to express your viewpoint, prioritise textual evidence over personal opinions. Support your arguments with examples from the text to maintain objectivity. Balance your insights with the author’s intent, ensuring a nuanced and well-supported analysis.

Can I use quotes from literary critics in my essay, and how do I integrate them effectively?

Yes, incorporating quotes from critics can add depth. Introduce the critic’s perspective and relate it to your argument. Analyse the quote’s relevance and discuss its impact on your interpretation. This demonstrates a broader engagement with literary conversations.

How do I avoid sounding repetitive in my essay?

Vary your language and sentence structure. Instead of repeating phrases, use synonyms and explore different ways to express the same idea. Ensure each paragraph introduces new insights, contributing to the overall development of your analysis. This keeps your essay engaging and avoids monotony.

Is it necessary to memorise quotes, or can I refer to the text during exams?

While memorising key quotes is beneficial for a closed text exam, you can refer to the text during open text exams. However, it’s crucial to be selective. Memorise quotes that align with common themes and characters, allowing you to recall them quickly and use them effectively in your essay under time constraints.

How can I improve my essay writing under time pressure during exams?

Practise timed writing regularly to enhance your speed and efficiency. Prioritise planning—allocate a few minutes to outline your essay before starting. Focus on concise yet impactful analysis. Develop a systematic approach to time management to ensure each section of your essay receives adequate attention within the given timeframe.

Still got a question? Leave a comment

Leave a comment, cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Let's get acquainted ? What is your name?

Nice to meet you, {{name}} what is your preferred e-mail address, nice to meet you, {{name}} what is your preferred phone number, what is your preferred phone number, just to check, what are you interested in, when should we call you.

It would be great to have a 15m chat to discuss a personalised plan and answer any questions

What time works best for you? (UK Time)

Pick a time-slot that works best for you ?

How many hours of 1-1 tutoring are you looking for?

My whatsapp number is..., for our safeguarding policy, please confirm....

Please provide the mobile number of a guardian/parent

Which online course are you interested in?

What is your query, you can apply for a bursary by clicking this link, sure, what is your query, thank you for your response. we will aim to get back to you within 12-24 hours., lock in a 2 hour 1-1 tutoring lesson now.

If you're ready and keen to get started click the button below to book your first 2 hour 1-1 tutoring lesson with us. Connect with a tutor from a university of your choice in minutes. (Use FAST5 to get 5% Off!)

Anthony Cockerill

| Writing | The written word | Teaching English |

How to write great English literature essays at university

Essential advice on how to craft a great english literature essay at university – and how to avoid rookie mistakes..

If you’ve just begun to study English literature at university, the prospect of writing that first essay can be daunting. Tutors will likely offer little in the way of assistance in the process of planning and writing, as it’s assumed that students know how to do this already. At A-level, teachers are usually very clear with students about the Assessment Objectives for examination components and centre-assessed work, but it can feel like there’s far less clarity around how essays are marked at university. Furthermore, the process of learning how to properly reference an essay can be a steep learning curve.

But essentially, there are five things you’re being asked to do: show your understanding of the text and its key themes, explore the writer’s methods, consider the influence of contextual factors that might influence the writing and reading of the text, read published critical work about the text and incorporate this discourse into your essay, and finally, write a coherent argument in response to the task.

With advice from English teachers, HE tutors and other people who’ve been there and done it, here are the most crucial things to remember when planning and writing an essay.

Read around the subject and let your argument evolve.

‘One of the big step-ups from A-level, where students might only have had to deal with critical material as part of their coursework, is the move toward engaging with the critical debate around a text.’

Reading around the task and making notes is all important. Get familiar with the reading list. Become adept at searching for critical material in books and articles that’s not on the reading list. Talk with the librarian. Make sure you can find your way around the stacks. Get log-ins for the various databases of online criticism, such as the MLA International Bibliography .

‘Tutors are looking for flair… for students to be nuanced and creative with their ideas as opposed to reproducing the same criticism that others already have.’

When reading, keep notes, make summaries and write down useful quotations. Make sure you keep track of what you’ve read as you go. Note the publication details (author, publisher, year and place of publication). If you write down a quotation, note the page number. This will make dealing with citations and writing your bibliography much easier later on, as there’s nothing more annoying than getting to the end of the first draft of your essay and realising you’ve no idea which book or article a quote came from or which page it was on.

‘The more I read, the sharper my own writing style became because I developed an opinion of the writing style I liked and I had a clear sense of the subject matter that I was discussing.’

‘Don’t wing the reading. Or the thinking. Crap writing emerges from style over substance.’

Get to grips with the question and plan a response.

‘Brain dump at the start in the form of a mind map. This will help you focus and relax. You can add to it as go along and can shape it into a brief plan.’

Before writing a single word, brainstorm. Do some free-thinking. Get your ideas down on paper or sticky notes. Cross things out; refine. Allow your planning to be led by ideas that support your argument.

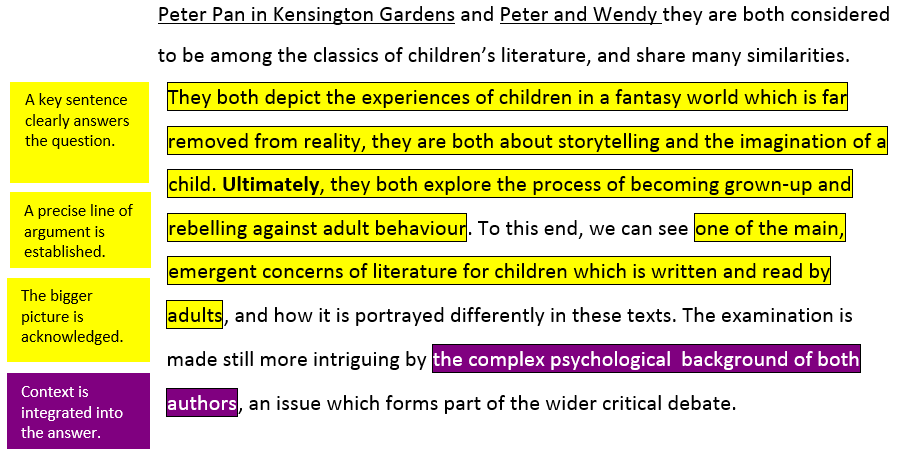

Use different colour-coded sticky notes for your planning. In the example below, the student has used yellow sticky notes for ideas, blue for language, structure and methods, purple for context and green for literary criticism, which makes planning the sequence of the essay much easier.

Structure and sequence your ideas

‘Make your argument clear in your opening paragraph, and then ensure that every subsequent paragraph is clearly addressing your thesis.’

Plan the essay by working out a sequence of your ideas that you believe to be the most compelling. Allow your ideas to serve as structural signposts. Augment these with relevant criticism, context and focus on language and style.

‘Read wide and look at different pieces of criticism of a particular work and weave that in with your own interpretation of said work.’

Write a great introduction.

‘By the end of the first paragraph, make sure you have established a very clear thesis statement that outlines the main thrust of the essay.’

Your introduction should make your argument very clear. It’s also a chance to establish working definitions of any problematic terms and to engage with key aspects of the wider critical debate.

Get to grips with academic style and draft the essay

‘[Write with] an ‘exploratory’ tone rather than ‘dogmatic’ one.’

Academic writing is characterised by argument, analysis and evaluation. In an earlier post , I explored how students in high school might improve their analytical writing by adopting three maxims. These maxims are just as helpful for undergraduates. Firstly, aim for precise, cogent expression. Secondly, deliver an individual response supported by your reading – and citing – of published literary criticism. Thirdly, work on your personal voice. In formal analytical writing such as the university essay, your personal voice might be constrained rather more than it would be in a blog or a review, but it must nonetheless be exploratory in tone. Tentativity can be an asset as it suggests appreciation of nuances and alternative ways of thinking.

‘I got to grips with what was being asked of me by reading lots of literary criticism and becoming more familiar with academic writing conventions.’

Avoid unnecessary or clunky sign-post phrases such as ‘in this essay, I am going to…’ or ‘a further thing…’ A transition devices that can work really well is the explicit paragraph link, in which a motif or phrase in the last sentence of a paragraph is repeated in the first sentence of the next paragraph.

Write a killer conclusion

‘There is more emphasis on finding your own voice at university, something which in many ways is inhibited by Assessment Objectives at A-Level. I don’t think ‘good’ academic writing is necessarily taught very well in schools — at least from my experience.’

The conclusion is a really important part of your essay. It’s a chance to restate your thesis and to draw conclusions. You might achieve closure or instead, allude to interesting questions or ideas the essay has perhaps raised but not answered. You might synthesise your argument by exploring the key issue. You could zoom-out and explore the issue as part of a bigger picture.

Be meticulous in your referencing.

Having supported your argument with quotations from published critics, it’s important to be meticulous about how you reference these, otherwise you could be accused of plagiarism – passing someone else’s work off as your own. There are three broad ways of referencing: author-date, footnote and endnote. However, within each of these three approaches, there are specific named protocols. Most English literature faculties use either the MLA (Modern Languages Association of America) style or the Harvard style (variants of the author-date approach). It’s important to check what your faculty or department uses, learn how to use it (faculties invariably publish guidance, but ask if you’re unsure) and apply the rules meticulously.

‘Read your work aloud, slowly, sentence by sentence. It’s the best way to spot typos, and it allows you to hear what is awkward and/or ungrammatical. Then read the essay aloud again.’

Write with precision. Use a thesaurus to help you find the right word, but make sure you use it properly and in the right context. Read sentences back and prune unnecessary phrases or redundant words. Similarly, avoid words or phrases which might sound self-important or pompous.

Like those structural signposts that don’t really add anything, some phrases need to be omited, such as ‘many people have argued that…’ or ‘futher to the previous paragraph…’.

Finally, make sure the essay is formatted correctly. University departments are usually clear about their expectations, but font, size, and line spacing are usually stipulated along with any other information you’re expected to include in the essay’s header or footer. And don’t expect the proofing tool to pick up every mistake.

Featured image by Glenn Carstens-Peters on Unsplash

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- analytical writing

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

AS & A2 English Blog

Revision notes and example essays on the edexcel a level english literature syllabus (2015), how to write and approach an essay.

At first glance many of us may find an essay question intimidating or confusing, especially under exam time pressure. It’s so normal, everyone’s minds go all over the place, questioning ‘Will I finish the essay on time?’ or ‘I need to include something no one else has thought of’. While there is no one way to approach writing an English essay, we have found this is what works for us best. Remember, you may want to try a range of essay writing techniques and structures and have them graded by a teacher, to find what works best for you. Here’s some advice on what to include in your essays and common mistakes we all tend to do. Hopefully these tips will ease your exam experiences and help you achieve the grade you’re definitely capable of!

Thesis statements:

Thesis statements might be new to you in A-Level, but they help you set out a compelling argument. Repeating the foundation of your thesis statement (what you are arguing) throughout your essay will achieve easy marks, helping you get the best grade, as you will remind the examiner and yourself that you are focusing on the question. Thesis statements are ultimately your introduction and by following these 3 steps you can construct an excellent introduction, displaying confidence and clarity (which examiners love!)

- Discuss: talk about the bigger picture, what the author is trying to say

- Define: how the question applies to the text

- Refine: what is your argument? (Go back to refine in every paragraph to reiterate your focusing on the question)

Why write a thesis statement?

- Establish your academic voice. Having a strong academic voice from the start of the essay will not only give your argument direction, but it will also boost your thesis, as this and the conclusion are reflective, personal ideas about the text. This, in turn, makes these parts of the essay extremely reflective of your style of writing and voice.

- Gain A03 marks for Context. In the ‘define’ section of the thesis, you could compare the writer’s themes to real world issues, whether this is past issues (e.g. Reagan’s presidency) that concerned the author at the time (what motivated/ inspired them to write the novel), or how these issues and themes are still prominent in society today (e.g. gender inequality and environmental concerns).

- Repeat your thesis statement and focus on it throughout. There is no point writing a thesis about ‘How Atwood uses language to portray oppression in The Handmaid’s Tale’ if one of the following paragraphs is about structure, or you will lose marks. It might be helpful to keep the thesis a general technique, such as language, as it gives you a lot to write about in the main body of your essay.

- Helps establish direction. For everyone, exams will cause us to fluster, it happens to the best of us. Having a strong thesis statement and therefore knowing your argument will really help you in the long run, as you can always support your thesis with evidence and context.

Sample introduction answering:

Explore the ways Atwood presents the difficulties of maintaining an identity in The Handmaid’s Tale

Much of a person’s life is spent creating and maintaining their identity: what they think they stand for, and what sort of person they want to be. The process of identity-formation is reversed in Atwood’s novel though as the regime seeks to remove any sense of identity from its handmaids in particular, as seen in the ‘re-education’ they receive at the Red Centre. Ultimately, Atwood uses Offred’s narrative voice and the manipulative use of state language to suggest that a person’s identity is not as much within her own control as she may think.

Make it interesting for the examiner:

- Academic voice

Establishing an academic voice shows the examiner that you are confident in your writing and that you have thought through your argument very carefully. Avoid using simple phrases that have been used by most (as it’s always best to stand out) such as:

- Instead of ‘for example’: exemplified by, demonstrates, illustrates, highlights, specifically, markedly, including, poignantly

- Instead of ‘contrast’: dichotomy, dissimilarity, juxtaposition, divergence, incongruity, distinction, disparity, chasm

- Instead of ‘in my opinion/I think’: the evidence suggests that…, it is credible to argue…, it is reasonable to advocate for…, one must consider.., it is possible to argue that…

- Instead of ‘in conclusion’: ultimately, in summation, on balance, in closing, to recapitulate

- Instead of ‘a lot’: plethora, myriad, notably

- Instead of ‘so’: therefore, subsequently, thus, hence, as a result

- Instead of ‘says’: declares, articulates, pronounces, discusses, mentions, remarks, suggests, states, reacts, responds

- Provide different perspectives

A strong answer to the question will provide a variety of perspectives uncovering multiple layers behind the author’s superficial meaning and integral when writing an essay. The examiner wants you to open up new conversations. In offering different perspectives the examiner can see that your writing is evaluative. It offers depth and insight into the novel, not just retaining an idea from class and writing it in an exam. Remember, when offering layers of meaning, you can write about perspectives you have seen that you disagree with. Use it as a counter-argument, opening with ‘one critic argues’ (even better if you can cite the critic!) We recommend reading critical articles too, very impressive!

- Judge the author on how they convey their concerns: is it convincing enough?

It is also important to be evaluative. Showing you’re evaluative and judge the author’s choices will exemplify your understanding and confidence with the text. Using particular words to sign post to the examiner you are being evaluative is crucial. Words such as: persuasive, compelling, criticise, endeavours to show, expresses, successfully conveys, fails to provide closure, ambiguous, didactic, moralistic, scholarly, eloquently, poignantly. This also plays into the tone of voice, which is key to analyse.

- Embedded quotes

Using embedded quotes will elevate your writing style, making the examiners reading your essay flow effortlessly. This also shows skill and how assured you are during the exam. Embedding context is also a hard skill as it can sometimes feel too forced as it does not apply to the rest of your point. Finding the correct context which applies suitably will also help with the smoothness and clarity of your writing.

- Literary and Structural terminology

Including literary terminology especially ones that are highly sophisticated help you gain AO2 marks, giving you more marks. Terminology will vary as poetry terminology is different from prose terminology.

- Does the ending provide us closure? Unsatisfactory openness?

- Does it help fulfill the author’s purpose/convey their messages/themes/concerns

- How have the characters changed? Character arcs

The Assessment Objectives

- A personal and creative responses to literary texts

- Remembering to zoom in and out (in the play and out to context)

- Subject terminology

- The author: read autobiographies or watch videos on their lives and their beliefs.

- The time it was written: their beliefs and important elements of their lives e.g. religion or nature

- Historical events

- How critics and the readers at the time responded to the text.

Common mistakes

- Unfinished Analysis. With the time pressure, we also forget to fully finish our analysis, leaving a potentially strong paragraph unfinished and holding us back from expressing our points completely. Therefore, planning beforehand is crucial even for just 5 minutes, so you yourself know what you will talk about and not get carried away!

- We tend to write everything we remember from lessons and our revision, which may not necessarily be relevant to the question. Again, planning will help you remember quotes and context relevant to your question. Take your time!

- Forgetting to plan!! Personally, I did not plan and fell into the trap of over analysing and not having enough time to finish other paragraphs.Taking as little as 5 minutes to plan what your main body paragraphs will be about can help you structure your essay and show the examiner that you have carefully thought about the question. (this will also come in handy when writing your conclusion)

- If you take the Edexcel English Literature exam, it is easy to fall into the trap of not learning quotes, as you are given the texts in the exam. It is still worth learning some quotes, as looking for them in an exam setting will take a long time and you may not pick judicious quotes (the relevance of the quotes you pick is worth marks too!).

- Writing too many ideas can be just as dangerous as writing too little ideas. If we write everything we’ve remembered from lessons, we risk losing in-depth analysis, leaving the essay with lots of incomplete arguments. If we write too little, there is a risk of lacking enough awardable content, and missing marks.

- Focus on the question. It is as easy as repeating the words of the question, further showing your understanding of the question to the examiner.

Writing a conclusion

The conclusion is often the hardest part of the essay to write. If you’re anything like me, you are writing it with about 5 minutes left of the exam (and panicking slightly!)

- Quality, not quantity: The conclusion only needs to be around 2 or 3 sentences, but it must be concise and strong. It helps prove your argument is compelling and convincing, something which should be carried through the essay until the very end.

- To do this, ideally you should read over the whole of your essay, to pick up on ideas you wrote about which link to your thesis, but you hadn’t considered when writing your thesis. However, with only 5 minutes left of an exam this may not be possible. This is where your plan comes in handy! Read over your plan (which is a ‘skeleton’ of your essay) and take your ideas in the same way from there.

These are a few tips to remember and maybe try out! Don’t worry about getting the perfect essay immediately, as practicing skills and writing essays for teachers to mark will definitely help you achieve your aspired grade.

Let us know if you have any questions about this post!

Marian and Maisie

Tragedy In A Streetcar Named Desire

Here’s a post on A Streetcar Named Desire, and my interpretations of how tragedy plays a key role within the play. It’s not structured like a proper essay but hopefully some of the ideas are useful!

To what extent is the play a tragedy and is it a conventional tragedy?

Williams’ is genius in how he plays with tropes of Greek tragedy and manipulates them to suit his aims and place Streetcar in the context of his time, 1940’s America. It is not conventional in this way, but the play still keeps many key elements of a tragedy. Ideas of hamartia and hubris can be seen in our tragic heroine – Blanche. Blanche makes several errors of judgement throughout the play: she blames Stella in scene 1, she decides not to go back to Laurel in the birthday scene, and continues to buy into illusions. She also displays hubris in how she denies fate and tries to escape death and reality through her illusions. Ironically, this only leads her further to tragedy. While these features of tragedy can be clearly seen in Blanche, the play itself is less clear-cut as a tragedy. I make the argument that there is no clear climax or turning point as such, and the play doesn’t follow a typical tragic arc. It could be argued that there are several points that could be considered the climax, or the point where there is no going back e.g: the birthday scene, the rape scene, the scene with Mitch, or even the final scene. Through this lack of clarity, Williams’ may be suggesting that tragedy in the play is inevitable and no specific moment can have the power to change the course of the play entirely, rather a series of events lead up to tragedy or events before the play even starts may predetermine the play’s tragic end.

I think it’s fair to say that a play’s ending is often what characterises it as a tragedy – or not a tragedy. The ending acts as the determiner. Typically, tragedies end in irreversible catastrophe, or death. While we do see catastrophe at the end of Streetcar, it is questionable how tragic the ending is as no-one dies, as the audience may expect. Also, there is a sense of victory for Blanche, which is conflicting for the audience. What I mean by this is that Blanche is so unaware of what is happening to her, she almost suffers the least out of the characters present in the final scene. She metaphorically describes her death, in a very romanticised way ‘And when I die, I’m going to die on the sea […] I shall die eating an unwashed grape one day out on the ocean.’ – she is claiming control of her end, and so in a way, she wins. She also leaves on the arm of a gentleman (the doctor), which we can imagine is what Blanche would want, so maybe it’s not so tragic for her after all? However, the play is tragic for other characters in this final scene. Notably, Stella: she is the one in the middle who has to deal with the emotional turmoil of what has happened to her sister, she cries out ‘Blanche! Blanche, Blanche!’. So, on a practical level, she arguably suffers the most. Furthermore, the perhaps most tragic aspect of this scene is how Stella has to live in illusions much like her sister now, as she is aware that Stanley raped Blanche, but chooses to ignore reality ‘I couldn’t believe her story and go on living with Stanley.’. Maybe, the tragedy has only begun and the real victim here is Stella.

Overall, the play is a tragedy, just not a conventional one. Williams’ makes tragedy more down-to-earth and adapted to the world he inhabited as his characters are not noblemen or women, they are just ordinary people. Arguably, Williams’ version of tragedy is more valuable to modern readers as we can relate to his characters more and take away messages from the play that are truly in correlation with today’s society.

When does the tragedy of the play begin?

Once again, I think it is up for discussion when the tragedy of the play begins, as arguably tragedy starts before the play even takes place and there are also many moments of tragedy very early on. It can be argued that the tragedy of the play resides in the old-fashioned ways of the South, as ultimately Blanche is a product of that world. So, the idea of the ‘Southern Belle’ is a cause of tragedy that exists before the play even starts. By doing this, Williams’ highlights the ongoing conflict between the North and South of America, and he may be commenting on the importance of progression in society, that it is foolish to confine ourselves to traditional beliefs. Furthermore, the tragedy of the play could start when Allan dies, and Blanche is constantly escaping death and reality from that moment on, which we know is ironically only going to lead Blanche towards more despair. The Varsouviana is played at moments of tragedy or heightened tension for Blanche in the play, which may support this theory that Allan’s death was the moment where tragedy began. In terms of the play itself, tragedy may begin the very moment that Blanche turns up at Elysian fields, which is hinted at when Blanche says ‘They told me to take a streetcar named Desire, and then transfer to one called Cemeteries and ride six blocks and get off at – Elysian Fields!’ – in essence, Blanche has been unknowingly led to her downfall by coming here as ‘Cemeteries’ is symbolic of her metaphorical death. Finally, hints towards tragedy are evident early on in the play e.g: when Blanche talks about the deaths at belle reve in scene 1, hints towards Allan’s death at the end of scene 1, and the poker night scene. Williams’ suggests that tragedy is very much dormant throughout the play – and in time it will surface.

Example Essay: Relationship between Blanche and Mitch

Williams presents Blanche and Mitch’s relationship as toxic in a way so subtle that neither of them notice the spiral they voluntarily go down until one of them is mad and the other has to watch them be sent to an asylum. Right from the start of the play, they bond over their mutual losses, “you need somebody. And I need somebody, too. Could it be you and me, Blanche?” A relationship founded on death and decay could foreshadow an ending even more destructive than their past one. Williams could be warning that there is no way that a relationship between a man and a woman from two different sides of the Civil War could ever survive in a relationship together, Mitch working a blue-collar job and Blanche, a ‘Southern belle’ raised in wealth on a plantation.

Williams presents the relationship between Blanche and Mitch as one of mutual destruction and dependence. Blanche’s loss of her husband Allen still preys on her, evidenced by the repeating motif of the Varsouviana Polka, the last dance they shared before Allen killed himself. Therefore, it seems wrong that she would move onto another man when she is still so deeply hurt. Her guilt could also be seen through this motif, as it often plays when she is around Mitch, who is also the only person she opens up to about him. A relationship where one of the participants is already regretful doesn’t seem healthy. Moreover, Williams presents Mitch as the most redeemable character, his kindness and sensitivity his strength, but if we look deeper, his desire for that normality leads him to ignore the abusive relationship between Stella and Stanley. The first time we get a sense that not all is right, is when he comforts Blanche after Stella and Stanely’s fight, commenting “there’s nothing to be afraid of, they’re crazy about each other.” He further silences Blanche’s protest at the violence, suggesting that there will be more of this invalidation of Blanche’s feelings throughout the relationship. Blanche’s desperate search for love could be leading her down a dangerous spiral where she becomes too dependent on a man, that when she is inevitably rejected, she falls back into that unhealthy tunnel of devaluing herself. This is further argued by critics, suggesting that ‘Blanche’s tragic flaw is that she adheres to the Southern tradition that she needs a man for completion when she can complete herself’. The whole relationship between Mitch and Blanche seems to be built on lies, that by the end of the play are excruciatingly revealed to Blanche, along with the facade of sweetness surrounding Mitch, which she has almost romanticised in her head, falling down. “I’ll tell you what I want. Magic!” Blanche is forced to admit to herself that everything she has built about herself is a lie, and whatever she had hidden beneath these lies might not be something anyone wants. Mitch forced her to see this, emphasising the incompatible nature of the two. Williams seems to be criticising the fact that Blanche forgot about Mitch’s separate upbringing in the war, and therefore the violence he was capable of, and Blanche’s desperate attempts to hide her secrets behind the lie of a Southern Belle seems to bring this violence out of Mitch, a man very deeply rooted in reality. This suggests that their relationship was built on lies and misunderstandings, as well as convenience – Blanche needing a husband to hide behind, and Mitch wanting a wife to bring home to his mother – which, due to their differing social standings, would never have allowed them to have a truly loving relationship. Here, Williams is commenting on the fact that the two sides of Civil War would never be able to live in peace, their views differing too much, almost resembling Shakespeare’s famous story of Romeo and Juliet.

Furthermore, Williams presents Blanche and Mitch’s relationship as dangerosuly volatile and isolating despite the comfort a relationship is supposed to bring. Right from the start of the play, Blanche is presented as ‘the other’. When she arrives she is described as “incongruous to the setting”, a semantic field of white making her seem otherworldly, whilst at the same time distancing her from the surroundings. Later when we find out that she was exiled from her former job and lost her childhood home, it becomes even more apparent that she has no home and nowhere to belong. Mitch represents Blanche’s last chance at finding love and stability within a world that is changing before her eyes quicker than she has time to adjust to. His rejection of her in Scene 9, could represent her moment of peripeteia, where she will never find love again. Her desire to paint everything in an ideological light clouding her views could be identified as the trigger for this distance between her and the rest of the world, highlighted by her demand of Mitch to cover the light, “I can’t stand a naked bulb.” This could be a metaphor for her inability to connect with reality, which has proved so disappointing to her. This is further emphasised by the motif of light throughout the play and her early description of being like a “moth”, wanting to be close to the light and the “magic”, and yet harming themselves in the process. It seems her desire to paint Mitch into becoming her perfect Southern beau, demanding he dance with her, despite him doing it “awkwardly”. This adjective highlights the illusion she fabricates around herself, as she calls hims her knight and he clumsily fumbles around her ‘magic’, possibly leading to the collapse of their relationship as Mitch finds out about all the “lies, lies, lies!” Her efforts to turn Mitch into her perfect husband despite him being a member of the new America after the Civil War, separates them, as he doesn’t appreciate the ideology of Blanche, a women clinging onto the old American ideals. Williams further underlines the inevitability of the collapse of the relationship with Blanche’s first impression of him before they’ve even met, when Stella says that “Stanely’s friends” are coming for dinner and Blanche immediately assumes they’re “Polacks?” Furthermore, her continued mocking of his lack of intelligence, specifically when she uses French words or phrases that he cannot understand, such as “Rosenkavalier”, shows that she only needs him to ensure her financial stability. However, the play Der Rosenkavalier has connotations of knights and comedic, happy endings, suggesting that that is what Blanche desires, despite her lies to Mitch. This again emphasises the destructive nature of her refusal to see reality, and how the relationship between Mitch and Blanche only pushed her further into her isolation, ending with her in an insane asylum.

Overall, Williams presents the relationship between Blanche and Mitch as damaging to both characters, emphasised by the ending, when Mitch is left “sobbing” on the floor and Blanche is banished to an asylum. By the end of the play, Blanche is more alone than she was at the start, her sister having abandoned her, leaving her with no hope of returning to her former life. Ultimately, Williams does this to highlight the backwards nature of the Southern values of women, as it pushed Blanche to the limits, and announces that they will inevitably cease to exist in a modern society because they will forever be at odds with the new society, emphasised by Blanche’s inability to empathise with Stanley or Mitch and in turn ending up in an insane asylum.

Example Essay: Unhappiness in On This Day I Complete My Thirty-Sixth Year

Explore the ways in which unhappiness is portrayed in On This Day I Complete My Thirty-Sixth Year by Lord Byron and in one other poem. (Specimen paper)

Thirty-Sixth Year: Unhappiness as the speaker has no purpose in life.

- “If thou regret’st thy youth, why live? ”

- “The sword, the banner, and the field” – could not only be convincing other young men to come and fight for their country, but also consoling himself that he will die soon in the war as well.

- “Glory and Greece.”

- “Makes a conscious effort to change the direction of the tone of the poem at stanza 5. “Where glory decks the hero’s bier / Or binds his brow.” what was once laborious and slow, is now fast-paced and anticipatory. (plosive alliteration).

- “That fire on my bosom preys” he now has no way to alleviate the pain, could be going to fight to displace that passion and find a new purpose, Fire can be the spark of life or it can be a tool for destruction.

Unhappiness is shown through time moving on and him growing old.

- “Yet, still though I cannot be beloved / Still let me love!” Could reflect his recent rejection by a boy much younger than him and he is despairing at not being wanted anymore, not loved and has nowhere to turn. Or it could be due to being ostracised by British society due to his scandalism. And despite being banished he still feels love from where he was brought up, and that is why he is sailing to help the Greeks take back their home.

- “The worm, the canker, and the grief” Feels his only company now is decay, grief and alcohol. Sadness that time is passing and he is becoming undesirable, and due to how he lived his life he doesn’t know what to do now.

- “A funeral pile” his passion, which is now alone due to no one wanting him, is burning him from the inside out.

- “But wear the chain” – feels that he is now chained by his age and experiences (links to Rousseau and his belief that men earn their chains through life, Byron now feels the collected weight of the chains of love that have become more and more complicated as he got older and now he has no way to untangle them.)

Holy Thursday: Unhappiness as uncertainty for others, lots of questions.

- “Trembling cry a song?”

- And their sun never does shine.”

- Volta from questioning and fearful, then to certainty that their situation cannot last because there is a heaven out there.

- Looks regular on the outside, but there is actually no rhyming scheme reflects the uncertainty underneath the speakers criticism of the upper-class.

Unhappiness at juxtapositions between rich and poor, and that after all this time has passed, nothing has been done.

- “In a rich and fruitful land”.

- “And their fields are bleak and bare”

- Condemns British society for having the power to change the levels of poverty and yet doing nothing about it – unhappiness is forms of poverty.

- Speakers unhappiness at not being able to do anything – links to 36th year in not having a purpose.

- Tone is savage and direct, could they not only be criticising the monarchy, but themselves as well.

Example Essay:

In the poem’s, on this day I complete My Thirty-Sixth Year by Lord Byron and Songs of Experience: ‘Holy Thursday’ by William Blake, unhappiness is portrayed as having no purpose in life whilst time passes and nothing has changed. In 36th Year, the poem starts as a melancholy reflection of the speaker’s past and then transitions to a quest for a noble quest. Holy Thursday describes the procession of Children who go to charity schools through London.

In 36th Year, Byron presents unhappiness as the feeling of time moving away without you and regretting your past. The rhetorical question “If thou regret’st thy youth, why live? ” suggests that the speaker is struggling with his past as he grows older. In a contextual view “Yet, still though I cannot be beloved / Still let me love!” could reflect his recent rejection by a boy much younger than him and he is despairing at not being wanted anymore. This reflects a problem many adults go through where their view of themselves does not fit with the way others view them. Byron is benign turned away because he is too old, and now is being forced to look back on his past to reflect about whether he accomplished anything material that could help him in his future. Or it could be due to being ostracised by British society due to his experimentation. And despite being banished he still feels love from where he was brought up, and that is why he is sailing to help the Greeks take back their home. The listing of “The worm, the canker, and the grief” implies that he feels his only company now is decay, grief and alcohol. It shows how he feels sadness that time is passing and he is becoming undesirable, and due to how he lived his life he doesn’t know what to do now. The “funeral pile” of his passion, which is now alone due to no one wanting him, is burning him from the inside out. Or it could be Byron’s past exploits returning to him and he is now burning with shame. This could further be reflected by “But wear the chain”, where he feels like the past and his reputation are restraining him and as time passes, what he desires moves further and further from him. It could be that he feels that he is now chained by his age and experiences, linking to Rousseau and his belief that men earn their chains through life – Byron now feels the collected weight of the chains of love that have become more and more complicated as he got older and now he has no way to untangle them.

In 36th Year, Lord Byron portrays unhappiness as a lack of purpose in life. The first 4 stanzas describe a life which has stagnated. The fricative alliteration of “flowers and fruits of love are gone”, suggests a deep feeling of loneliness and yet being unable to do anything. The “f” sound of “flowers and fruits” is laborious to sy, suggesting that the speaker feels as though their life and love has become a chore. Moreover, “that fire on my bosom preys” highlights how he now has no way to alleviate his desire for love, which could be why he is going to fight with the Greeks to displace that passion which no one wants anymore. Fire can be the spark of life or it can be a tool for destruction. In a volta at the start of stanza 5, the speaker makes a conscious effort to change the direction of the tone of the poem, suggesting that despite the unhappiness, they are going to look for a new purpose. This is further emphasised by “Where glory decks the hero’s bier / Or binds his brow,” where what was once laborious and slow, is now fast-paced and anticipatory. The plosive alliteration suggests excitement at finding something new. However, the hesitancy is shown in the asyndetic list “the sword, the banner, and the field” where it becomes clear that he is not only trying to convince other soldiers to come and fight, but also encourage himself.

In SE:HT, Blake portrays unhappiness as being unsettled how time passes and nothing changes about the juxtapositions between the rich and the poor. Despite the poor living in a developed, “rich and fruitful land” their “fields are bleak and bare”. Here the plosive alliteration of “bleak and bare” has a less optimistic tone for the future like in 36th Year, but instead it is a condemnation of the rich – Blake is criticising the wealthy for leaving the poor children in poverty and unhappiness despite having the power to change it. Could also reflect the speakers unhappiness at not being able to do anything – links to 36th year in not having a purpose. This bitterness about the future and how the time passes and nothing happens is reflected by the anaphora in stanza 3, a syndetic list, suggesting that the future is going to be nothing but a repetition of this endless pain. This is further underlined by the metaphor, “it is eternal winter there.” The adjective “eternal” coupled with the structure of 4 stanzas made of 4 lines highlights the never ending cycle of suffering and unhappiness.

Furthermore, in SE:HT, Blake displays unhappiness as uncertainty for others and the crippling belief that there is nothing you can do to help them. “Is that trembling cry a song?” reflects the speaker’s confusion that nothing has changed in London. It also could show how the speaker is trying to convince themselves that there children still feel enough joy to sing, but also the rational part of their brain acknowledges the truth of it being a “trembling cry”. “And their sun never does shine,” as though there are constantly storm clouds over their life and there is no way out. There is a volta from stanzas 2 and 3 where the tone switches from questioning to fearful, then to certainty that their situation cannot last because there is a heaven out there. Seems that they are comforting themselves, whilst calling to others that this cannot continue. This uncertainty is further reflected in the rhyming scheme – it looks regular, but there actually isn’t a rhyming scheme – the confusion at having no purpose and no way to help.

Overall, both authors portray unhappiness as a lack of purpose and the speed of passing time. The Greek war of Independence described in 36th Year could represent the struggle between the First and Second Generation Romantic poets, where Byron is trying to find his purpose and establish himself as a separate poet from his influences. The shorter lines and questioning tone of SE:HT end inconclusively with many of the questions unanswered reflecting how many of the issues with the poor were swept under the rug at the time leaving the asker in a never ending purgatory of witnessing unhappiness and being unable to do anything about it.

Themes in ‘An Easy Passage’ by Julia Copus: Youth

How is the theme of youth explored in ‘An Easy Passage’ by Julia Copus?

- In ‘An easy Passage’ Copus presents youth as a process of discovery and embracing unknown danger that is key to the strength needed to move into the adult world. This sense of the unknown can be seen in the repeated use of the adjective ‘halfway’ to establish the theme of journey in this poem. For instance, the poet described how ‘Once she is halfway up there’ what the girl in the poem ‘must not do is think of the narrow windowsill, the sharp drop…’ This sentence can be read on both a literal and metaphorical level, as she is halfway in her physical climb to her window, but also ‘halfway’ in the journey from childhood to adulthood. The risk of the ‘drop’ could represent the unknown potential for failure as she grows into an adult, as shown later in the poem with the line ‘What can she know of the way the world admits us less and less the more we grow?’ The use of this rhetorical question creates an almost judgemental tone to the poem that could symbolise external pressure of society that will judge this girl as she matures, which is metaphorically shown through the risk of a fall.

- Just as the girl is balancing precariously on the windowsill, she also walks the fine line as she grows between acceptance and rejection from a society that is constantly watching. There is even a voyeuristic tone that comes through the character of the ‘secretary’ who described the girls as ‘wearing next to nothing’ with ‘her tiny breasts resting lightly on her thighs.’ which seem almost intrusive on the girl’s privacy as she judges her body. This is also displayed through the metaphor of the ‘long, grey eye of the street’ with the imagery of the ‘eye’ representing societies’ more voyeuristic tendencies to judge others’ personal lives.

- The fact that the girl is ‘halfway’ through the journey, only half sure that she won’t fail, creates a sort of tension in the poem that reflects on the real life fears surrounding young people as they begin to enter society. She is at an age where she is aware of the possibility of social rejection, as teenage years are often a time where children are very conscious of being able to fit in. This could be seen in the metaphor of her journey climbing the house, as she is seen to be ‘trembling’ with fear, watched by a friend below who she is ‘half in love with.’ Again, this repeated use of the adjective ‘half’ suggests a hesitancy that could be a symbol again of the unknown, in this case unknown desire and sexuality.

- In a way this sense of the overwhelming unknown that haunts all of the girl’s decisions is deliberately mirrored in the free verse structure of the poem, which leaves no point for the reader to pause. This also mirrors the fact that embracing the unknown and expansive future is one long process that not even the adults of the poem have conquered, as seen by the older secretary who still reads the ‘astrology column’. She is still looking for answers to what the future holds.

- However, although this theme of the unknown may seem overwhelming, the poet does give us hope for the girl’s future even within all this uncertainty. One of the last lines of the poem described ‘oyster painted toenails of an outstretched foot’ that is compared to ‘a flash of armaments.’ The connotations of war and security in the noun ‘armaments’ suggests a strength to the girls that may not have been revealed before. The metaphor of the ‘oyster’ also promotes a cause for hope, as over time oysters may produce priceless pearls which could represent how the girl’s future may be rich in experiences and joy.

By Karensa Lopez

Mary Shelley’s ‘Frankenstein’: How a generation’s obsession with science influenced the making of the creature.

It is difficult in our modern society to understand how science in the Romantic era was so closely linked with the domestic, politics and also theology. In our current time, science can often seem distant from us. Something that happens in labs that is often beyond our understanding. For the everyday people of the Romantic era, science (or Natural Philosophy as it was then called) was often considered one of the key ways in which the mysteries of the natural world and the soul could be discovered. This keen interest in science and in pushing the boundaries of human understanding was a key theme in Mary Shelly’s ‘Frankenstein’, as she herself witnessed this often anarchic society in which the problems and principles of scientific research and how far humans should go in pursuit for knowledge were beginning to come to light.

Mary Shelly was exposed to science from a young age, through her father William Godwin, who was often considered one of the most controversial men in England due to his influence in radical political and artistic circles. He had many visitors such as writers Coleridge and Wordsworth who met Mary through their admiration of her father for his radical views. We know that Mary was present for these sessions, as in her memoirs she reflects fondly on how she and her half-sister Claire Clairmont would hide underneath the sofa to listen to Coleridge recite his poem ‘The Ancient Mariner’ which also makes several appearances in ‘Frankenstein’. The most famous scientists of the time also visited, such as the doctor Anthony Carlisle and Humphry Davy. Scientific experiments demonstrated in the home were common for the middle classes in the Regency period, and so it was likely these visitors also did experiments in the house where Mary lived which could have influenced some of her writing. However, the most important perhaps of these visitors, not only for her writing but for her personal life, was Percy Shelly with whom she would elope with at the age of 16 and married in 1816 after the suicide of his first wife.

Percy Shelly was a prime example of the obsessive nature of scientists at this time, when science and the occult were still somewhat intertwined. The first school that Percy attended was Syon house, where he was greatly influenced by the scientist Adam Walker. He has a keen interest in Natural philosophy (the individual sciences had not been fully established, and so were grouped under this term) and toured the country giving lectures on the power of electricity and giving experiments to show its potential use to transform society. Percy Shelly was fascinated by this, and with the help of one of Walkers’ assistants, he built electrical experiments in his rooms and also experimented with galvanism on his sisters until they refused.

This obsession still remained when he took his first classes at Eton, but soon began to intertwine with a fascination with the occult, much in the same way as Victor in ‘Frankenstein’ had an obsession with ‘The philosopher’s stone and the elixir of life.’ He shunned all other students at the school and was bullied daily so that he confined himself to his rooms. He immersed himself in Alchemist writers such as Paracelsus and Cornelius Aggripa who often spoke more of magic than actual science which was considered useless by the new logical age of science known as the Enlightenment. His love of the occult became almost hysterical, and was known as ‘Mad Shelly’ after one set of experiments caused him to run wild through the countryside believing he had summoned the devil. This again is very similar to Frankenstein, who ‘shunned my fellow creatures.’ and who suffered from ‘frantic impulses’ before creating the creature as he became increasingly engrossed in the sciences. One of his friends Jefferson Hogg even described Shelly’s rooms as ‘The chemist in his laboratory, the alchemist in his study, the wizard in his cave.’ that is an image which mirrors the most recognizable scenes from the book, the mad scientist in his laboratory, which has been adapted countless times for the stage and in film. It is likely that Frankenstein is a mixture of many influences in Mary’s life, but the most obvious of these is certainly her husband, who even used the pen name ‘Victor’ when writing his first collection of poems, ‘Poetry by Victor and Cazier’ in 1810. Shelly was just one amongst many young men influenced by so-called ‘Master scientists’ such as Humphry Davy, who tested the boundaries of how far humans could go in search of knowledge. Many would even go as far as testing experiments on other people or themselves, and even Shelly’s younger siblings recounted in letters the fear of seeing Shelly approach them with some new electrical device that he wanted to test on them when they were young.