Unit 7: Injury Prevention and Safety Promotion

Unit 7 focuses on injury prevention and safety promotion in schools. You will find information on children’s disaster preparedness, brain injury, substance use disorder, and violence and suicide prevention. Additionally, information on sun and water safety, hearing loss, and mercury safety in schools. Lesson plans and trainings with free CEU’s are available under some topics.

Emergency Preparedness in Schools

- Children in Disasters Emergency Kit Checklists

- Easy as ABC

General Injury Prevention & Safety Promotion

- Don’t Mess with Mercury (includes lesson plans)

- Hearing Loss Prevention (includes lesson plan and accompanies the comic book issue Ask a Scientist: How Loud is Too Loud? [PDF – 5 MB] | Español [PDF – 5 MB] )

- Heat and Infants and Children

- HEADS UP to Schools

- Concussion Handout for Kids [PDF – 4 MB]

- Sun Safety Tips for Schools

- Water Safety

Violence Prevention

- Two introductory modules that provide an overview of ACEs and the public health approach to preventing them. Additionally, please find training modules for specific professions including mental health providers appropriate for school counselors.

- Coping with Stress

- Dating Matters ® : Strategies to Promote Healthy Teen Relationships is a comprehensive teen dating violence prevention model developed by CDC to stop teen dating violence before it starts. Dating Matters is an evidence-based teen dating violence prevention model that includes prevention strategies for individuals, peers, families, schools, and neighborhoods. The online module is designed for educators.

Opioids and Other Drugs

- CDC’s Response to the Opioid Overdose Epidemic

- Find free science- and standards-based classroom lessons and multimedia activities on teens and drugs – all funded or created by the National Institute on Drug Abuse for Teens (NIDA).

- Games: Drug Use and Effects

- This free fact sheet by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) provides facts about opioids for teens. It describes short- and long-term effects, lists signs of opioid use and helps to dispel common myths about opioids.

- Youth Opioid Abuse Prevention Brochure [PDF – 3.48 MB]

Healthy Youth

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Chapter Seven: Preventing Injury; Protecting Children’s Safety

Kelly McKown

Chapter 7 Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Connect classroom design to safety and injury prevention.

- Discuss ways to handle unsafe behavior by understanding the function of behaviors.

- Describe how teachers can ensure the toys and materials they offer children do not present injury risks and are nontoxic.

- Explain ways adults can support safe and developmentally appropriate use of technology.

- Lists ways to protect children from choking, poisoning, burns, drowning, and falls.

- Identify how to implement safe sleep practices to protect against Sudden Infant Death Syndrome.

- Explain what active supervision is and what it might look like.

- Discuss how to create a culture of safety.

- Identify common risks that lead to injury in children.

- Describe how understanding injuries can help create a safety plan that prevents future injury.

- Summarize strategies teachers can use to help children learn about and protect their own safety.

- Recall several ways to engage family in safety education.

- Analyze the value of allowing risky play.

Introduction

Keeping children safe must be a top priority for all early care and education programs. Active Supervision is the most effective strategy for creating a safe environment and preventing injuries in young children. It transforms supervision from a passive approach to an active skill. Staff use this strategy to make sure that children of all ages explore their environments safely. Each program can keep children safe by teaching all staff how to look, listen, and engage.

What is Active Supervision?

Active supervision requires focused attention and intentional observation of children at all times. Staff position themselves so that they can observe all of the children: watching, counting, and listening at all times. During transitions, staff account for all children with name-to-face recognition by visually identifying each child. They also use their knowledge of each child’s development and abilities to anticipate what they will do, then get involved and redirect them when necessary. This constant vigilance helps children learn safely.

Strategies to Put Active Supervision in Place

The following strategies allow children to explore their environments safely. Infants, toddlers, and preschoolers must be directly supervised at all times. This includes daily routines such as sleeping, eating, and diapering or bathroom use. Programs that use active supervision take advantage of all available learning opportunities and never leave children unattended.

Set Up the Environment

Staff set up the environment so that they can supervise children and be accessible at all times. When activities are grouped together and furniture is at waist height or shorter, adults are always able to see and hear the children. Small spaces are kept clutter-free and big spaces are set up so that children have clear play spaces that staff can observe.

Position Staff

Staff carefully plan where they will position themselves in the environment to prevent children from harm. They place themselves so that they can see and hear all of the children in their care. They make sure there are always clear paths to where children are playing, sleeping, and eating so they can react quickly when necessary. Staff stay close to children who may need additional support. Their location helps them provide support, if necessary.

Scan and Count

Staff are always able to account for the children in their care. They continuously scan the entire environment to know where everyone is and what they are doing. They count the children frequently. This is especially important during transitions when children are moving from one location to another.

Specific sounds or the absence of them may signify reason for concern. Staff who are listening closely to children immediately identify signs of potential danger. Programs that think systematically implement additional strategies to safeguard children. For example, bells added to doors help alert staff when a child leaves or enters the room.

Anticipate Children’s Behavior

Staff use what they know about each child’s individual interests and skills to predict what he/she will do. They create challenges that children are ready for and support them in succeeding. But, they also recognize when children might wander, get upset, or take a dangerous risk. Information from the daily health check (e.g., illness, allergies, lack of sleep or food, etc.) informs staff’s observations and helps them anticipate children’s behavior. Staff who know what to expect are better able to protect children from harm.

Engage and Redirect

Staff use what they know about each child’s individual needs and development to offer support. Staff wait until children are unable to problem-solve on their own to get involved. They may offer different levels of assistance or redirection depending on each individual child’s needs. [2]

Active Supervision for Infants and Toddlers

Infant/toddler care is responsive, individualized care. And it’s important to think about infants and toddlers that are cared for in small groups with a primary-caregiver system of care and also to think about the flow of the day as being responsive to the individualized needs of the children. Staff work very closely with children throughout the day guiding them through individual or small-group routines and experiences. Staff are providing responsive, individualized care, and they will know each child well. That’s an important piece of both individualized care and active and responsive supervision. They have a good sense of how each child gets through the day, what their abilities are, what their temperament is. Even as they grow and change from day to day, they’re able to follow each child in their care with an understanding of how it is that they’re growing.

In center-based programs or larger family child care homes, more than one caregiver is working together in a team. And the other thing that’s important to remember is the kind of communication that develops between the two teachers in a classroom or a family-childcare provider and an assistant — a communication that supports a child’s safe movement throughout the day as well as their ability to explore and grow in a nurturing environment.

Adults provide support to each other, particularly at key times of the day, like transitions. All of those important, individualized routines require both adults to work together, such as individual sleeping times, going indoors and outdoors, changing times, feeding and eating times for infants and toddlers, and other times during the day when there may be a particular child that needs individualized care. It’s so important that the staff working with them are working together to support continuity of care.

The environment itself can be a partner in caring for infants and toddlers, particularly when it comes to keeping children safe. We want to create environments that provide places for children to play and be both together and apart but always in full view and within easy reach of a caring and attentive adult. [6]

Creating an Environment of Yes!

An environment of “yes” means that everything infants and toddlers can get their hands on is safe and acceptable for them to use. One way to ensure this is to for adults to do ongoing safety checks in group care spaces and provide families with information about doing safety checks of their own. The teacher, home visitor, and the child’s family play a vital role in making sure everything is safe, then stepping back to allow exploration.

Sometimes infants and toddlers will use materials in creative ways that surprise us! When teachers feel uncomfortable about an activity, they should stop and ask themselves two questions:

- Is it dangerous?

- What are the children learning from this experience?

If it is decided that the activity is safe with supervision, they should stay nearby. They should be thoughtful and open to what the children might be learning. If the activity is not safe, they need to consider what else might address the infants’ and toddlers’ curiosity in the same way. For example, if young toddlers are delighted to discover that by shaking their sippy cups, liquid comes out; a teacher may be worried that this water on the floor will lead to a slippery accident. Instead, they might provide squeeze bottles outside or at the water table. The adult is responsible for keeping children safe and encouraging learning through curiosity.

Saying “no” to infants and toddlers or asking them to “share” is a strategy that rarely works. One way to prevent conflict is to reflect on, and then set up, the space where children play in ways that promote “yes!”

- What areas generate the most “no’s” or require the most adult guidance?

- What do the children need and enjoy the most when it comes to playtime?

- Do you have multiples of favorite toys?

- Do you have enough places where toddlers can play alone or with a few friends?

- Do you have adequate space for active play?

- Is the room appropriately child-proofed? [7]

Classroom Design

Designing an effective and engaging classroom environment takes careful thought and planning, but it’s important. A well-organized classroom that is interesting, orderly, and attractive contributes to children’s participation and engagement with the learning materials and activities. This engagement, in turn, contributes to children’s learning. Not all early learning centers for infants provide a high-quality environment for the youngest learners. What Does a High-Quality Program for Infants Look Like?

Let’s look at it from a child’s perspective. We want children to feel safe and comfortable in the classroom. We want them to be interested in the learning activities and to take full advantage of being at school and take full advantage of the activities you’ve planned and the materials you’ve selected. It can be helpful to get down at a child’s level and take a look at the classroom. Does it feel welcoming and inviting? Is there enough room to move, make choices, and stay involved with a toy or activity or project? And does the room help the child know what to do and what’s expected?

Active Supervision

It’s important not to become complacent with safety practices. Teachers need to keep it fresh, thoughtful, and intentional. This begins with setting up the environment. Classrooms will have unique factors to consider. But some general considerations include making sure that there is a teacher responsible for every part of the space children are in, which may be referred to as zoning, and for every part of the day (including transitions).

How teachers position their bodies is really important. They should see all of the children in their care from any position in the room. And when in playing areas, their back should not be to the center of the room, but towards the wall. It is also important to move closer to children as needed (rather than staying in one place and potentially missing out on problems that may arise).

Teachers also need to talk to each other, using back-and-forth communication, so that safety information is easily spread through the room. It may seem strange at first, sometimes, for teachers to talk to each other; but, it’s incredibly helpful for active supervision – when there are either changes in staff or children’s routines, changes in roles, changes during transitions.

And one of the main purposes of zoning was created to help all children be engaged and to minimize unnecessary wait times. When all staff know their roles in the classroom with zoning and tasks are getting handled, children are engaged and the unsupervised wait time is really minimized.

During transitions or routine changes, teachers need to have a heightened awareness. Transitions are challenging times for both children and their teachers, so the risk to safety increases. One thing that teachers can think about is how they can minimize the number of changes so that there aren’t as many transitions happening in the classroom. There should be plans what adults will do, before, during, and after transition times. 10

Designing an Effective and Safe Classroom Environment

There are all sorts of classrooms. They differ by size and shape, amount of light and wall space, placement of sinks and counters, and amount of storage. Figuring out how to design the physical space and to maximize children’s interactions within the space will take some time. Make a floor plan. Move things around. Take a look at other classrooms and see what works.

Here are a few things to think about when designing your space and making it as workable as possible. Think about the number of interest areas or centers that you want or need for the group of children. Arrange the space so that noisy areas are separated from quiet areas. Locate centers next to needed storage or equipment. Use furniture or other items to provide boundaries. But, make sure that the adults can see all of the areas of the room. [2]

Factors to Consider

Space and boundaries:

· Are the centers clearly defined with furniture, rugs, or shelves?

· Is there enough space for all children to easily move about the room?

· In each defined area, is there adequate space for the number of children using it?

Proximity and distance:

· Are the quiet and noisy areas in proximity or separated?

· Are centers located near things that children need to complete projects (art center near sink, puzzle or game shelves within reach of tables, etc.)?

· Are teachers able to view children in all centers?

Home and culture:

· What home-like features are included in the classroom?

· How is(are) the culture(s) of the local community reflected in the classroom?

Flexibility and permanence:

· How does the space accommodate gross motor activity?

· What aspects of the physical space cannot be changed (cost or structural issues) and are challenging to overcome (e.g., limited access to natural light, cumbersome cubbies, etc.)?

Engagement and challenging behaviors:

· Are there areas of the classroom where challenging behaviors are more likely to occur?

· Are there areas where typically children are positively engaged in classroom activities?

Traffic patterns:

· Can children move easily from space to space?

· Is running and wandering discouraged?

Material selection:

· Are materials chosen to support development and learning?

· Are they culturally relevant and meaningful to the children?

· Is there is a sufficient variety and quantity (without overwhelming children)? [3]

Pause to Reflect

Tips for Environmental Design

Traffic patterns need to discourage running.

Use furniture, rugs, and similar items to define boundaries.

Ensure that teachers can see what is happening in all areas of the classroom.

Cultural and home-like features are present in the room.

Use spaces with as much flexibility as possible.

Quiet and noisy centers are spaced appropriately.

Ensure interesting classroom content selection is balanced with appropriate stimulation versus overstimulation.

Each center provides enough information about what to do there and how to play. [1]

[1] Presenter Notes: Designing Environments by the Office of Head Start is in the public domain.

Grouping of Children

Teachers want to be intentional about how they group children, whether it’s a decision made in the moment or as part of lesson planning. Match the size of the group with the purpose of the activity. Think about the children who will be in the group. Young children need opportunities to participate and learn with the whole group, small groups, and they will thrive with a bit of one-on-one time with an adult. [6]

Large groups are good for:

· Introducing concepts

· Building community

· Conducting routine activities

Small groups are good for:

· Maximizing back and forth interactions

· Peer modeling of skills

· Guiding instruction

One-on-one interactions are good for:

· Tasks requiring complex skills

· Instance when a child needs specific direction and assistance [7]

Every early childhood environment is full of pros and cons; it is how educators work with the many characteristics of a classroom that can make a tremendous difference. Teachers can be surprised by the results when they:

· Assess the spaces for both limitations and strengths.

· Strategize how to optimize what they have to work with in their classrooms.

· Try a different arrangement, see what happens, and then modify based on what is working and what is not.

Sometimes a modification can be minor (raising or lowering a shelf, “stop” signs over unavailable areas, masking tape to better define a space, etc.). This highlights the “work-in-progress” nature of early childhood environments. As the needs of children change, the room may need minor changes or have to be rearranged completely to meet those needs. [9]

Interpersonal Safety

Children can behave in ways that hurt themselves or others so teachers must prepared to handle unsafe behaviors in their duty to protect children from injury. An important way to think about behavior is as a form of communication. Young children let us know their wants and needs through their behavior long before they have or can use words in the heat of the moment. They give us cues to help us understand what they are trying to communicate.

Early childhood educators can help children by interpreting their cues and responding to meet their needs. The following example illustrates the importance of responding to the possible meaning behind behavior:

Javon bites Blair because he wants the block she is playing with and we remove Javon from the situation. Not only are we not responding to his want or need, but we are taking him out of the context where he can learn to communicate his feelings in a way that doesn’t hurt others.

Forms and Functions of Behavior

There are many reasons a child might use specific behaviors. This is why it is important for adults to carefully observe children, pay attention to their cues, get to know them, and know what part of the schedule gives them a hard time to better understand what they are trying to tell us through their behavior. [11]

Each behavior has a:

FORM = the behavior the child is using to communicate

AND A FUNCTION = the reason or purpose the child is using that behavior [12]

Table 7.1 – Forms and Functions of Behavior [13]

Here are some examples of form and functions of infants, toddlers, and preschoolers:

Table 7.2 – Examples of Forms and Possible Functions of Behaviors [14]

Form and function are also shaped by culture. Children are socialized to express their feelings in culturally acceptable ways. It is important to talk with families so you can look for acceptable ways that children express themselves in a culturally respectful way.

As you have probably already experienced—it is not always easy to figure out the meaning of a child’s behavior. To add to the complexity of understanding the meaning of behavior:

A single form of behavior may serve more than one function. For example, a toddler might use biting (form) for different functions (“I want the toy you have.” “I want to play with you but don’t know how to let you know.” “I’m tired.” “I’m frustrated because you don’t understand what I am trying to tell you.” “I want some attention.”)

Several forms of behavior may serve one function. For example, a child’s purpose (function) may be to build with their favorite blocks, but they use different forms of behavior (biting, yelling, grabbing, running away with the blocks, sharing) based on how they feel that day, who is playing in the block area, or based on their cultural expectations.

The meaning of behavior is shaped by culture, family, and the unique makeup and experiences of the individual child. For example, some cultures may express sadness by crying or by having a nonchalant facial expression. Some cultures may express happiness by laughing and being exuberant, while others may expect more restrained behaviors.

Some of these functions of communication become a concern for children’s safety (of the child communicating, the other children, and other people in the environment). Early childhood educators must take the time to understand a behavior’s meaning so that they can help the child replace unsafe forms of communication with forms that don’t hurt others or harm the environment. Pausing to try to figure out the meaning behind a child’s behavior—instead of just reacting to the behavior—can change the way we see a child, the way we respond to a child, and the way we teach a child. Becoming a “behavior has meaning” detective who is always on the lookout for the meaning of behavior will help you keep children safe. [15] Take a look at the following example of an unsafe behavior, what it might mean, and what an educator might do to support the child.

Taking a Closer Look at Behavior

You may also find it valuable to examine behavior much the way you would injuries and traffic patterns. Gather data about unsafe behaviors:

When are they happening? Are there specific times of day that children are finding it more challenging to behave/communicate in safe ways?

Where are they happening? Are there hot spots for challenging behavior? What in the environment might be the focus of the unsafe behavior/communication?

Why they are happening? What happened before the led up to the behavior? What happened after?

Who are the behaviors happening between? All children will have times where they communicate with unsafe behavior, but some children may need more adult support in certain contexts (time of day, activity, groupings of children, etc.).

Look for patterns. Reflect on what can be changed in the physical environment, schedule/routine, groupings, and supervision to help prevent children from hurting themselves or others when trying to communicate their needs.

Safe Toys, Materials, and Equipment

Play is a natural activity for every young child. Play provides many opportunities for children to learn and grow – physically, mentally, and socially. If play is the child’s work, then the toys, materials, and equipment in the environment are what will enable children to do their work well and safely. [19]

Protecting children from unsafe toys is the responsibility of everyone. Careful toy selection and proper supervision of children at play are still—and always will be—the best ways to protect children from toy-related injuries. [20]

It is important that educators consider both safety and durability when choosing toys for children. Toys should be constructed to withstand the uses and abuses of children in the age range for which the toy is appropriate.

The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) has safety regulations for certain toys. Manufacturers must design and manufacture their products to meet these regulations so that hazardous products are not sold (see Table 3.3).

Table 7.3 – Mandatory Toy Safety Regulations [21]

In addition to the mandatory standards, many toy manufacturers also adhere to the toy industry’s voluntary safety standards (see Table 3.4). [22]

Table 7.4 – Voluntary Standards for Toy Safety [23]

Toys should be chosen with care. Teachers should look for quality design and construction. Safety labels to look for include “Flame retardant/Flame resistant” on fabric products and “Washable/hygienic materials” on stuffed toys and dolls. Watch for the hazards listed in Table 3.5 [25] .

Table 7.5 – Hazards to Avoid in Toys [26]

Check all toys periodically for breakage and potential hazards. A damaged or dangerous toy should be thrown away or repaired immediately.

Age Appropriate Toys

Teachers must keep in mind the ages of children they are choosing toys for, including their typical interests and skill levels. The manufacturer’s age recommendation is a good starting place to ensure that toys are age-appropriate. Warnings such as “Not recommended for children under 3” should be followed. [27] See Table 3.6 for some age-appropriate toys to consider. Please note that toys appear on the list when they become appropriate and are not repeated in later ages.

Table 7.6 – Age Appropriate Toys [28]

Federal law requires that all art materials offered for sale to consumers of all ages in the United States undergo a toxicological review of the complete formulation of each product to determine the product’s potential for producing adverse chronic health effects. It also requires that the art materials be properly labeled for acute and chronic hazards, as required by the Labeling of Hazardous Art Materials Act(LHAMA) and the Federal Hazardous Substances Act (FHSA), respectively.

In addition to the LHAMA requirements, art materials – such as paintbrushes and stencils – that are designed or intended primarily for children 12 years of age or younger, are also required, like all children’s products, to comply with the requirements of the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act of 2008 (CPSIA). [32] Under the FHSA, most children’s products that contain a hazardous substance are banned, whether the hazard is based on chronic toxicity, acute toxicity, flammability, or other hazard identified in the statute.

Children’s products that meet the FHSA’s definition of an art material include, but are not limited to, crayons, chalk, paint sets, colored pencils, and modeling clay. Non-toxic art and craft supplies intended for children are readily available. Read the labels and only purchase art and craft materials intended for children and that are labeled with the statement “Conforms to ASTM D-4236.” [33]

One such label will come from the Art and Creative Materials Institute’s (ACMI) certification program. “ACMI-certified product seals…indicate that these products have been evaluated by a qualified toxicologist and are labeled in accordance with federal and state laws… The AP (Approved Product) Seal identifies art materials that are safe and that are certified in a toxicological evaluation by a medical expert to contain no materials in sufficient quantities to be toxic or injurious to humans, including children, or to cause acute or chronic health problems.” [34]

Safety Risks from Art Materials

For certain chemicals and exposure situations, children may be especially susceptible to the risk of injury. For example, since children are smaller than adults, children’s exposures to the same amount of a chemical may result in more severe effects. Further, children’s developing bodies, including their brains, nervous systems, and lungs may make them more susceptible than adults. Differences in metabolism may also affect children’s responses to some chemicals.

Children‘s behaviors and cognitive abilities may also influence their risk. For example, children under the age of 12 are less able to remember and follow complex steps for safety procedures, and are more impulsive, making them more likely to ignore safety precautions. Children have a much higher chance of toxic exposure than adults because they are unaware of the dangers, not as concerned with cleanliness and safety precautions as adults, and are often more curious and attracted to novel smells, sights, or sounds. Children need regular and consistent reminders of safety rules, and there is no substitute for direct supervision.

Guidelines for Selecting Art and Craft Materials

Here are some helpful reminders about choosing art materials for children:

· Note that even products labeled ‘non-toxic’ when used in an unintended manner can have harmful effects.

· Products with cautionary/warning labels should not be used with children under age 12.

· Avoid solvents and solvent-based supplies, which include turpentine, paint thinner, shellac, and some glues, inks, and a few solvent-containing permanent markers.

· Avoid products or processes that produce airborne dust that can be inhaled (including powdered tempera paint).

· Avoid old supplies, unlabeled supplies, and be wary of donated supplies with cautionary/warning labels and that do not contain the statement “Conforms to ASTM D4236.”

· Look for products that are clearly labeled with information about intended uses.

· Give special attention to students with asthma or allergies, which may elevate the students’ sensitivities to fumes, dust, or products that come into contact with the skin. [41]

· Gather your supplies beforehand so that you can continue to supervise their use without needing to step away.

· Instruct children on safety practices before you begin (such as, modeling how to cut safely with scissors).

· Do activities in well-ventilated areas.

· Use protective equipment (such as smocks).

· Assume that anything you use should be safe enough that it won’t harm children if it gets on their skin or in their mouths and/or eyes. [42]

Using Technology and Media Safely

Developmentally appropriate use of technology can help young children grow and learn, especially when families and early educators play an active role. Early learners can use technology to explore new worlds, make-believe, and actively engage in fun and challenging activities. They can learn about technology and technology tools and use them to play, solve problems, and role play. But how technology is used is important to protect children’s health and safety.

Technology can be a Tool for Learning

What exactly is developmentally appropriate when it comes to technology for children? In Technology and Interactive Media as Tools in Early Childhood Programs Serving Children from Birth through Age 8 , the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) and the Fred Rogers Center state that “appropriate experiences with technology and media allow children to control the medium and the outcome of the experience, to explore the functionality of these tools, and pretend how they might be used in real life [43] .”

Lisa Guernsey, author of Screen Time: How Electronic Media—From Baby Videos to Educational Software—Affects Your Young Child , also provides guidance for families and early educators. For example, instead of applying arbitrary, “one-size-fits-all” time limits, families and early educators should determine when and how to use various technologies based on the Three C’s: the content, the context, and the needs of the individual child. They should ask themselves the following questions:

· Content—How does this help children learn, engage, express, imagine, or explore?

· Context—What kinds of social interactions (such as conversations with families or peers) are happening before, during, and after the use of the technology? Does it complement, and not interrupt, children’s learning experiences and natural play patterns?

· The individual child—What does this child need right now to enhance his or her growth and development? Is this technology an appropriate match with this child’s needs, abilities, interests, and development stage? [44]

Early childhood educators should keep in mind the developmental levels of children when using technology for early learning. That is, they first should consider what is best for healthy child development and then consider how technology can help early learners achieve learning outcomes. Technology should never be used for technology’s sake. Instead, it should only be used for learning and meeting developmental objectives, which can include being used as a tool during play.

When technology is used in early learning settings, it should be integrated into the learning program and used in rotation with other learning tools such as art materials, writing materials, play materials, and books, and should give early learners an opportunity for self-expression without replacing other classroom learning materials. There are additional considerations for educators when technology is used, such as whether a particular device will displace interactions with teachers or peers or whether a device has features that would distract from learning. Further, early educators should consider the overall use of technology throughout a child’s day and week, and adhere to recommended guidelines from the Let’s Move initiative, in partnership with families. Additionally, if a child has special needs, specific technology may be required to meet that child’s educational and care needs. And dual language learners can use digital resources in multiple languages or translation to support both their home language and English development.

For Infants and Toddlers

Research shows that unstructured playtime is particularly important for infants and toddlers because they learn more quickly through interactions with the real world than they do through media use and, at such a young age, they have limited periods of awake time. At this age, children require “hands-on exploration and social interaction with trusted caregivers to develop their cognitive, language, motor, and social-emotional skills.”

For children under the age of 2, technology use in early learning settings is generally discouraged. But if determined appropriate by the IFSP team under Part C of the IDEA, children with disabilities in this age range may also use technology, for example, an assistive technology device to help them communicate with others, access and participate in different learning opportunities, or help them get their needs met.

Active versus Passive Engagement

Early childhood educators should understand the differences between passive and active use of technology. Passive use of technology generally occurs when children are consuming content, such as watching a program on television, a computer, or a handheld device without accompanying reflection, imagination, or participation.

Active use occurs when children use technologies such as computers, devices, and apps to engage in meaningful learning or storytelling experiences. Examples include sharing their experiences by documenting them with photos and stories, recording their own music, using video chatting software to communicate with loved ones, or using an app to guide playing a physical game. These types of uses are capable of deeply engaging the child, especially when an adult supports them. While actions such as swiping or pressing on devices may seem to be interactive, if the child does not intentionally learn from the experience, it is not considered to be active use. To be considered active use, the content should enable deep, cognitive processing, and allow intentional, purposeful learning at the child’s developmental level.

Early childhood educators also need to think of ways they can reduce the sedentary nature of most technology use. Technology can encourage and complement physical activity, such as doing yoga with a video or learning about the plants outdoors with a nature app.

The Digital Divide

Research points to a widening digital use divide, which occurs when some children have the opportunity to use technology actively while others are asked primarily to use it passively. The research showed that children from families with lower incomes are more likely to complete passive tasks in learning settings while their more affluent peers are more likely to use technology to complete active tasks.

For low-income children who may not have access to devices or the internet at home, early childhood settings provide opportunities to learn how to use these tools more actively. For example, research shows that preschool-aged children from low-income families in an urban Head Start center who received daily access to computers and were supported by an adult mentor displayed more positive attitudes toward learning, improved self-esteem and self-confidence, and increased kindergarten readiness skills than children who had computer access but did not have support from a mentor.

Co-Viewing of Technology

Most research on children’s media usage shows that children learn more from content when parents/caregivers or early educators watch and interact with children, encouraging them to make real-world connections to what they are viewing both while they are viewing and afterward.

There are many ways that adult involvement can make learning more effective for young children using technology. Adult guidance that can increase active use of more passive technology includes, but are not limited to, the following:

· Prior to the child viewing content, an adult can talk to the child about the content and suggest certain elements to watch for or pay particular attention to;

· An adult can view the content with the child and interact with the child in the moment;

· After a child views the content, an adult can engage the child in an activity that extends learning such as singing a song they learned while viewing the content or connecting the content to the world.

Safety Risks of Technology

In addition to the health risks of sedentary activity (in place of active play), there are concerns about privacy and security with any technology. The rights of children under 13 and technology in school are governed by federal laws, but looking at privacy policies is important.

Software and apps may also include advertising and in-app purchasing (generally inappropriate for young children). So early childhood educators should choose software and apps that avoid advertising and in-app purchases.

Not all technology is appropriate for young children and not every technology-based experience is good for young children’s development. To ensure that technology has a positive impact, adults who use technology with children should continually update their knowledge and equip themselves to make sophisticated decisions on how to best leverage these technology tools to enhance learning and interpersonal relationships for young children.

Access to technology for children is necessary in the 21st century but not sufficient. To have beneficial effects, it must be accompanied by strong adult support. [53]

Preventing Injuries Indoors

Some injuries that early childhood educators should be aware of and intentionally act to prevent in the last chapter were presented in the previous chapter and earlier in this chapter during the discussion about safe toys and art materials. Here is some further information about injuries that are more likely to happen indoors.

Choking occurs when an object blocks the airway, preventing breathing. [54] Infants have the highest rates of choking (140 per 100,000). That risk decreases as they get older and their airway increases in size, with 90% of fatal choking happening in children less than 4 years of age. [55]

Reducing the Risks of Choking

The main way to prevent choking is to recognize that objects that are 1½ inches or less in diameter are higher risk. [56] Foods are the most common cause of choking. Having children sit during snacks and meals at an unhurried pace, allowing time for children to properly chew their food helps prevent choking on food. Food is safest when cut into small pieces or served in small amounts. See Table 3.7 for foods that commonly cause choking.

Table 7.7 – Common Choking Hazards [57]

Toys, and other items that children may play with, are another common source of choking hazards. Ensuring children only have access to age-appropriate toys is an important step. See Table 3.7 for items that should be kept out of reach of young children.

Teachers can use a small parts tester, a commercial product commonly known as choke tube, to test whether or not an object is a choking hazard. Recognizing and responding to choking will be addressed in Chapter 5. [58]

There are many hazards that put children at risk for accidental poisoning, both indoors and outdoors. Poisoning can occur at any time a harmful substance is intentionally or unintentionally ingested. Poisons come in many forms including plants, cleaning supplies, spoiled food, and medications. Children, who are naturally curious and like to explore, are in particular at risk for poisoning.

Guidelines to Prevent Poisoning

· Keep all cleaning supplies and chemicals locked.

· All medications should be kept in a locked storage area, out of reach.

· Check medications periodically for expiration dates and properly dispose of expired medications. Some medications become toxic when they are past their expiration date.

· Do not tell children that medication is “candy” as this makes it look more attractive to them.

· Ensure all medications and chemicals are properly labeled. Childproof caps should be on medicine bottles.

· Use safe food practices. (see Chapter 15)

· Never use cans that have bulges or deep dents in them.

· Keep poisonous plants out of reach of children and pets. (see Table 3.8)

· Keep the number for Poison Control near a telephone. [61]

Table 7.8 Poisonous Plants [62]

Every day, over 300 children ages 0 to 19 are treated in emergency rooms for burn-related injuries and two children die as a result of being burned.

Younger children are more likely to sustain injuries from scald burns that are caused by hot liquids or steam, while older children are more likely to sustain injuries from flame burns that are caused by direct contact with fire. [63]

Causes of Burns

Burns can be caused by dry or wet heat, chemicals, or electricity (both indoors and outdoors).

· Burns from dry heat can occur from fire, irons, hairdryers, curling irons, and stoves (American Institute for Preventive Medicine, 2012; Leahy, Fuzy & Grafe, 2013).

· Burns from wet or moist heat occur from hot liquids, such as hot water or steam (American Institute for Preventive Medicine; Leahy, Fuzy & Grafe). These types of burns are called scalds. Scalds can occur within seconds and cause serious injury.

· Chemical burns occur from chemical sources and can also cause serious burns when exposed to skin, or if swallowed, whether intentionally or unintentionally.

· Electrical burns can cause very serious injury as they can burn both the outside and inside of the person’s body, causing injury that cannot be seen, and which can be life-threatening.

· Radiation burns can also occur from sources of radiation such as sunlight (American Institute for Preventive Medicine). [64]

Types of Burns

Burns are divided into first, second, and third degree burns.

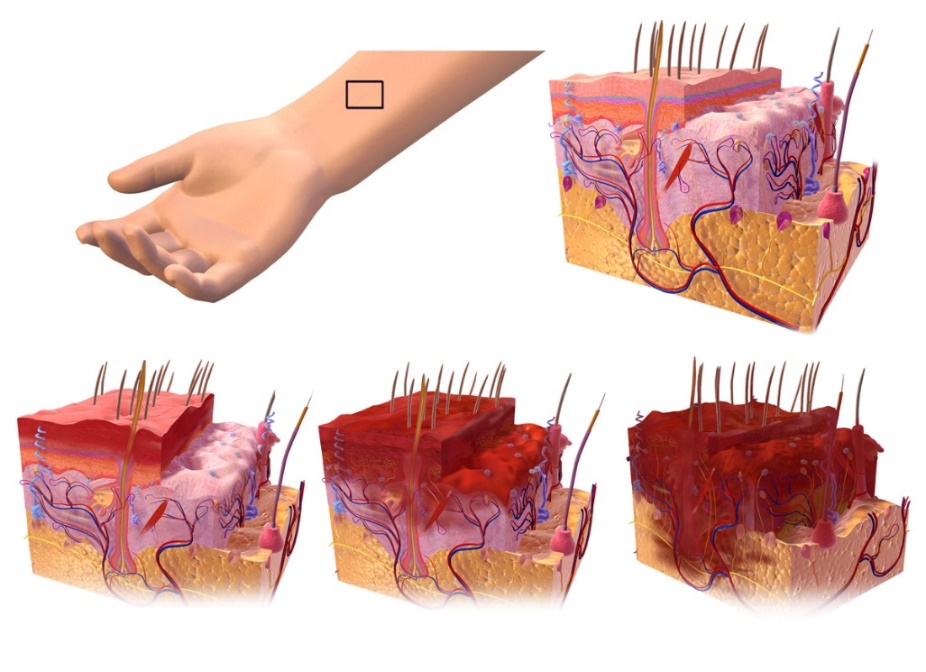

First degree burns affect only the outer layer of the skin (epidermis). These types of burns are the least serious as they are only on the surface of the skin. First degree burns usually appear red, dry, and slightly swollen (MedlinePlus, 2014). Blisters do not occur with this type of burn. They should heal within a couple of days (American Institute for Preventive Medicine, 2012). A first degree burn is pictured in the bottom left of Figure 3.20.

Second degree burns affect the top layer of the skin and the second layer of skin underneath (dermis). These are more serious than first degree burns. The skin may appear very swollen, red, moist, (MedlinePlus, 2014) and may have blisters or look watery and weepy (American Institute for Preventive Medicine, 2012). A second degree burn is pictured in the bottom middle of Figure 3.20.

Third degree burns are the most serious burn. A third degree burn affects all layers of the skin and may affect the organs below the surface of the skin. The skin may appear white or black and charred (MedlinePlus, 2014). The person may deny pain because the nerve endings in their skin have been burned away (American Institute for Preventive Medicine, 2012). Third degree burns require immediate medical treatment. If teachers suspect a child has a third degree burn, they should immediately call 911. A third degree burn is pictured in the bottom right of Figure 3.20. [65]

Chemical burns can occur anytime a liquid or powder chemical comes into contact with skin or mucous membranes that line the eyes, nose, or throat. Chemical burns may also occur if a chemical is swallowed. These burns can cause serious injury and emergency services should be contacted. If a person receives a chemical burn, the chemical should be removed from the skin by using a gloved hand to brush it off and then wash the area with plenty of cool water. Electrical burns can occur if a person has been using an electrical appliance and is exposed to water or if an electrical short occurs while using the electrical appliance. Using faulty or frayed cords on electrical appliances can result in electrical burns. Electrical burns are a serious injury. Emergency medical services (EMS) should be immediately activated.

Never use oils such as butter or vegetable oil on any type of burn as this can cause further injury. For first or second degree burns flush the area with plenty of cool (not ice cold) water for about 15 minutes or until the pain decreases and cover with a clean, dry bandage. Using ice or ice-cold water can cause frostbite (American Institute for Preventive Medicine, 2012). For major burns remove any clothing that is not stuck to the skin, cover the burned area with a dry, clean cloth, and seek emergency assistance. [67]

Guidelines to Prevent Burns

· Install and regularly test smoke alarms.

· Practice fire drills. [68]

· Train staff to use fire extinguishers.

· Teach children to stop, drop, and roll. [69]

· Never allow children to use electrical appliances unsupervised.

· Never use electrical appliances near water sources.

· Never use electrical appliances in which the cord appears to be damaged or frayed.

· Never pull a plug from the cord. Always remove a cord from an outlet by holding the base of the plug.

· Cover electrical outlets with childproof plugs. Never allow children to put anything inside an electrical outlet.

· Ensure stoves and other appliances are turned off when finished with them.

· Turn pot handles inward so that a person cannot accidentally bump a handle and spill hot liquids.

· Do not use space heaters and other personal heaters.

· Check to be sure the hot water heater is not set too high. To avoid scalds from hot tap water, hot water heaters should be set to 120 degrees or less (MedlinePlus, 2014).

· Keep chemicals, cleaning solutions, and matches and lighters securely locked and out of reach of children. [70]

Safe Sleeping

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) is identified when the death of a healthy infant occurs suddenly and unexpectedly, and medical and forensic investigation findings (including an autopsy) are inconclusive. SIDS is the leading cause of death in infants 1 to 12 months old, and approximately 1,500 infants died of SIDS in 2013 (CDC, 2015). Because SIDS is diagnosed when no other cause of death can be determined, possible causes of SIDS are regularly researched. One leading hypothesis suggests that infants who die from SIDS have abnormalities in the area of the brainstem responsible for regulating breathing (Weekes-Shackelford & Shackelford, 2005). [71]

This is a very important topic for early childhood educators as one study found that while data suggests that only 7% of incidents of SIDS should occur while children are in child care, 20.4% actually did. [72]

Risk Factors for SIDS

Babies are at higher risk for SIDS if they:

- Sleep on their stomachs

- Sleep on soft surfaces, such as an adult mattress, couch, or chair or under soft coverings

- Sleep on or under soft or loose bedding

- Get too hot during sleep

- Are exposed to cigarette smoke in the womb or in their environment, such as at home, in the car, in the bedroom, or other areas

- The adult smokes, has recently had alcohol, or is tired.

- The baby is covered by a blanket or quilt.

- The baby sleeps with more than one bed-sharer.

- The baby is younger than 11 to 14 weeks of age.

Important Facts About SIDS

· SIDS happens in families of all social, economic and ethnic groups.

· Most SIDS deaths occur between one and four months of age.

· SIDS occurs in boys more than girls.

· The death is sudden and unexpected, often occurring during sleep. In most cases, the baby seems healthy.

· Although it is not known exactly what causes SIDS, researchers know that it is not caused by suffocation, choking, spitting up, vomiting, or immunizations.

· SIDS is not contagious. [74]

Reducing the Risks

Although the sudden and unexpected death of an infant cannot be predicted or prevented, research shows that certain infant care practices can help reduce the risk of a baby dying suddenly and unexpectedly. Early childhood educators can help lower the risk of SUID for infants less than one year of age by following these risk reduction guidelines.

Sleeping Position

The chance of an infant dying suddenly and unexpectedly in childcare is higher when a baby first starts the transition from home to care. Research shows if a baby has been placed on his/her back by the families, and the childcare provider places the baby to sleep on his/her stomach, there is a higher risk of death in the first weeks of child care. One of the most important things you can do to reduce the risk of sudden unexpected death is to place babies to sleep on their backs.

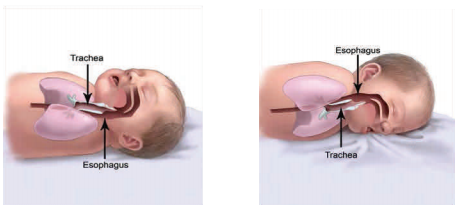

Healthy babies do not choke when placed to sleep on their backs. By reflex, babies swallow or cough up fluids to keep the airway clear. Since the windpipe (trachea) is positioned on top of the esophagus, fluids are not likely to enter the airway. (See Figure 3.21)

Babies who are able to roll back and forth between their back and tummy should be placed on their backs for sleep and allowed to assume their sleep position of choice. When infants fall asleep while playing on their tummies, move the baby to a crib onto his/her back to continue sleeping.

Cribs, Sleep Surface and Bedding

Infants should sleep in a crib, bassinet, portable crib or play yard that conforms to the safety standards of the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC). The mattress should be firm, fit tightly, and be covered with a tight fitted sheet. Babies should not sleep on adult beds, waterbeds, couches, beanbag chairs or other soft surfaces. Do not use fluffy blankets or comforters under the baby, or put the baby to sleep on a sheepskin, pillow or other soft materials. Keep stuffed toys, bumper pads, loose bedding and other toys and soft objects out of the crib.

Temperature

Babies should be kept warm, not hot. Babies should be dressed with only one additional layer than you are wearing for warmth. In areas where babies sleep, keep the temperature so that it feels comfortable to you. If needed, infants can be dressed in blanket sleepers for warmth. This ensures that the baby’s head will be uncovered during sleep.

No one should smoke around children. California Child Care Licensing Regulations prohibit smoking in childcare centers. Smoke in the infants’ environment is a major risk factor for SIDS.

If the family provides a pacifier, it should be offered to the infant. If a pacifier is used, it should never be attached to a string. Infants should not be forced to take a pacifier and if it falls out during sleep it doesn’t need to be given back to the infant.

Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding has many health benefits for mother and baby, including a reduced risk of SIDS. Childcare programs should be breastfeeding friendly. [76]

Indoor Falls

While most falls occur outdoors, and this topic is addressed in Chapter 4, they can also happen indoors. Teachers (and adults at home) can prevent falls indoors by

- Installing stops on windows that prevent them from being opened more than four inches or install window guards on lower parts of windows. Removing furniture from near windows. Screens should not be relied on to prevent a fall.

- Installing safety gates at the top and bottom of staircases. Installing lower rails on stairs that children can reach and use. Making sure the surface of the stairs stays clear.

- Using safety straps and harnesses on baby equipment and furniture. Children should not be left unattended in high chairs or on changing tables.

- Baby walkers should not be used (licensing prohibits these).

- Teaching children to walk where surfaces may be slick. Preventing these surfaces as much as possible, such as wiping up spills. [78]

Indoor Water Safety

Small children are top-heavy; they tend to fall forward and headfirst when they lose their balance. They do not have enough muscle development in their upper body to pull themselves up out of a bucket, toilet or bathtub, or for that matter, any body of water. Even a bucket containing only a few inches of water can be dangerous for a small child.

It’s important that early childhood educators follow the safety practices outlined in Chapter 4 for water safety both indoors and outdoors, keep children under active supervision, and be very aware of containers of water. [79]

Active supervision is critical to keep young children safe. When programs create a culture of safety, they go beyond following regulations and policies, by making a commitment to protecting safety so that children don’t get hurt. There are some common risks to safety that educators should be aware or (and that will be covered in more depth in the next two chapters). When early care and education programs create a safety plan using data they have gathered by documenting and analyzing the injuries children get, they can make changes to help protect children’s safety.

Teachers need to create safe indoor environments in which children engage, explore, and interact. By recognizing that behavior is communication, they can help children use safe behaviors to get their needs met. Teachers should choose age-appropriate toys and materials that are well constructed, hazard-free, and nontoxic. With adult support, children can navigate media and technology safely. Teachers must work to prevent injuries that may occur indoors, such as choking, poisoning, burns, drowning, and falls. And teachers that care for infants must follow practices to reduce the risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome.

Chapter 7 Review

Chapter 3 Workbook

See Workbook in Chapter 4

References:

[1] Photo provided by author.

[2] Managing the Classroom: Designing Environments by the Office of Head Start is in the public domain.

[3] Assessing Your Physical Spaces and Strategizing Chances by the Office of Head Start is in the public domain.

[4] Presenter Notes: Designing Environments by the Office of Head Start is in the public domain.

[5] Photo provided by author.

[6] Managing the Classroom: Designing Environments by the Office of Head Start is in the public domain.

[7] Preparing for Intentionally Grouping Children by the Office of Head Start is in the public domain.

[8] Photo provided by author.

[9] Presenter Notes: Designing Environments by the Office of Head Start is in the public domain.

[10] Presenter Notes: Designing Environments by the Office of Head Start is in the public domain.

[11] Behavior Has Meaning: Presenter Notes by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain.

[12] Form and Function by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain.

[13] Behavior Has Meaning: Presenter Notes by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain.

[14] Form and Function by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain.

[15] Behavior Has Meaning: Presenter Notes by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain.

[16] Girl Playing on Plastic Inline Boards is free for commercial use.

[17] AIAN Education Manager Webinar Series: February 2013 by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is in the public domain

[18] Biting: A Fact Sheet for Families by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is in the public domain.

[19] Which Toy for Which Child by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission is in the public domain.

[20] Think Toy Safety by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission is in the public domain.

[21] Which Toy for Which Child by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission is in the public domain.

[22] Which Toy for Which Child by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission is in the public domain.

[23] Think Toy Safety by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission is in the public domain.

[24] Think Toy Safety by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission is in the public domain.

[25] Think Toy Safety by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission is in the public domain.

[26] Think Toy Safety by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission is in the public domain.

[27] Think Toy Safety by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission is in the public domain.

[28] Think Toy Safety by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission is in the public domain.

[29] Children Wooden Multicolored Toy Labyrinth by Marco Verch is licensed under CC BY 2.0 .

[30] Image is in the public domain.

[31] Image is in the public domain.

[32] Art Materials Business Guide by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission is in the public domain.

[33] Art and Craft Safety Guide by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission is in the public domain.

[34] ACMI. (2020). Home. Retrieved from https://acmiart.org/

[35] Image by The Art and Creative Materials Institute is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

[36] Image provided by author

[37] Image provided by author

[38] Image provided by author

[39] Image provided by author

[40] Image provided by author

[41] Art and Craft Safety Guide by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission is in the public domain.

[42] Snell, S. (2018). Don’t Eat the Paint: Art Safety with Young Children. Retrieved from https://communitycarecollege.edu/early-childhood-education/tips-for-art-safety-with-young-children/

[43] National Association for the Education of Young Children & Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media at Saint Vincent College (2012), page 8. (cited in: https://tech.ed.gov/earlylearning/principles/ )

[44] Guernsey, L. (2012) Screen Time: How electronic media—from baby videos to educational software—affects your young child. New York, NY: Basic Books. (cited in: https://tech.ed.gov/earlylearning/principles/ )

[45] Bilingual Pre-K Technology Integration by Professional Learning is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

[46] Council on Communications and Media. (2016). Media and Young Minds. Pediatrics, 138 (5). Retrieved from https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/138/5/e20162591

[47] AAP, APHA, & MCHB. (2011). Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards: Guidelines for Early Care and Educational Programs, Third Edition. Retrieved from https://nrckids.org/files/CFOC3_updated_final.pdf

[48] California Preschool Program Guidelines by the California Department of Education is used with permission.

[49] California Preschool Program Guidelines by the California Department of Education is used with permission.

[50] Guiding Principles for Use of Technology with Early Learners by the Office of Educational Technology is in the public domain.

[51] U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Technology. (2015) Ed tech developer’s guide. Retrieved from https://tech.ed.gov/developers-guide/ (cited in https://tech.ed.gov/earlylearning/principles/ )

[52] Guiding Principles for Use of Technology with Early Learners by the Office of Educational Technology is in the public domain.

[53] Guiding Principles for Use of Technology with Early Learners by the Office of Educational Technology is in the public domain.

[54] Anderson, K. (2020). Choking: Knowing the Signs and What to Do. Retrieved from https://www.chla.org/blog/rn-remedies/choking-knowing-the-signs-and-what-do

[55] American Academy of Pediatrics. (2020). Safety and Injury Prevention Curriculum. Retrieved from https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/healthy-child-care/Pages/Safety-and-Injury-Prevention.aspx

[56] American Academy of Pediatrics. (2020). Safety and Injury Prevention Curriculum. Retrieved from https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/healthy-child-care/Pages/Safety-and-Injury-Prevention.aspx

[57] Anderson, K. (2020). Choking: Knowing the Signs and What to Do. Retrieved from https://www.chla.org/blog/rn-remedies/choking-knowing-the-signs-and-what-do

[58] Anderson, K. (2020). Choking: Knowing the Signs and What to Do. Retrieved from https://www.chla.org/blog/rn-remedies/choking-knowing-the-signs-and-what-do

[59] Small Parts: What Parents Need to Know , by the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission is in the public domain.

[60] Image by r. nial bradshaw is licensed under CC BY 2.0 .

[61] Safety and Injury Prevention by Kimberly McLain, Erin K. O’Hara-Leslie, & Andrea C. Wade is licensed under CC BY 4.0

[62] Even Plants Can Be Poisonous by from the Office of Head Start is in the public domain.

[63] Burn Prevention by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain

[64] Safety and Injury Prevention by Kimberly McLain, Erin K. O’Hara-Leslie, & Andrea C. Wade is licensed under CC BY 4.0

[65] Safety and Injury Prevention by Kimberly McLain, Erin K. O’Hara-Leslie, & Andrea C. Wade is licensed under CC BY 4.0

[66] 1st, 2nd, and 3rd degree burns by Bruce Blaus is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 .

[67] Safety and Injury Prevention by Kimberly McLain, Erin K. O’Hara-Leslie, & Andrea C. Wade is licensed under CC BY 4.0 .

[68] Burn Prevention by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain.

[69] Mayo Clinic. (2019). Burn Safety: Protect your child from burns. Retrieved from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/infant-and-toddler-health/in-depth/child-safety/art-20044027

[70] Safety and Injury Prevention by Kimberly McLain, Erin K. O’Hara-Leslie, & Andrea C. Wade is licensed under CC BY 4.0 .

[71] Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

[72] Moon, R. Y., Patel, K. M., & Shaefer, S. J. (2000). Sudden infant death syndrome in child care settings. Pediatrics , 106 (2 Pt 1), 295–300. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.106.2.295

[73] Image by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is in the public domain.

[74] California Dept. of Public Health MCAH. (2014). What Child Care Providers and Other Caregivers Should Know. Retrieved from https://cchealth.org/sids/pdf/Child-Care-SIDS-Booklet.pdf.

[75] California Dept. of Public Health MCAH. (2014). What Child Care Providers and Other Caregivers Should Know. Retrieved from https://cchealth.org/sids/pdf/Child-Care-SIDS-Booklet.pdf.

[76] California Dept. of Public Health MCAH. (2014). What Child Care Providers and Other Caregivers Should Know. Retrieved from https://cchealth.org/sids/pdf/Child-Care-SIDS-Booklet.pdf.

[77] California Dept. of Public Health MCAH. (2014). What Child Care Providers and Other Caregivers Should Know. Retrieved from https://cchealth.org/sids/pdf/Child-Care-SIDS-Booklet.pdf.

[78] Mayo Clinic. (2020). Infant and toddler health. Retrieved from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/infant-and-toddler-health/in-depth/child-safety/art-20046124

[79] California Childcare Health Program. (2003). Prevent Drowning. Retrieved from https://cchp.ucsf.edu/sites/g/files/tkssra181/f/drownen081803_adr.pdf

[1] Community Playthings. (2020). Inspiration Gallery. Retrieved from https://www.communityplaythings.com/inspiration/room-inspirations

[2] Active Supervision from the Office of Head Start is in the public domain.

[3] California Infant/Toddler Curriculum Framework by the California Department of Education is used with permission.

[4] Active Supervision from the Office of Head Start is in the public domain.

[5] California Infant/Toddler Curriculum Framework by the California Department of Education is used with permission.

[6] Keeping Babies Safe: Active Supervision for Infants & Toddlers by the Dept. of Health and Human Services is in the public domain.

[7] Environment as Curriculum for Infants and Toddlers by the Office of Head Start is in the public domain.

[8] California Infant/Toddler Curriculum Framework by the California Department of Education is used with permission.

[9] Active Supervision for Preschoolers by the Dept. of Health and Human Services is in the public domain.

[10] Infant/Toddler Learning and Development Program Guidelines by the California Department of Education is used with permission.

[11] Creating and Enhancing a Culture of Safety Head Start Town Hall Meeting: September 12, 2018 by the Dept. of Health and Human Services is in the public domain.

[12] 10 Actions to Create a Culture of Safety by the National Center on Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain.

[13] Fatal Injury Reports, National, Regional and State, 1981-2018 , by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain.

[14] Child Injury by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain.

[15] CDC Childhood Injury Report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain.

[16]Health implications of children in child care centres Part B: Injuries and infections. (2009). Paediatrics & child health , 14 (1), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/14.1.40

[17] California Dept. of Public Health MCAH. (2014). What Child Care Providers and Other Caregivers Should Know. Retrieved from https://cchealth.org/sids/pdf/Child-Care-SIDS-Booklet.pdf.

[18] American Academy of Pediatrics. (2020). Safety and Injury Prevention Curriculum. Retrieved from https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/healthy-child-care/Pages/Safety-and-Injury-Prevention.aspx

[19] Anderson, K. (2020). Choking: Knowing the Signs and What to Do. Retrieved from https://www.chla.org/blog/rn-remedies/choking-knowing-the-signs-and-what-do

[20] Drowning Prevention by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain.

[21] California Childcare Health Program. (n.d.). Prevent Drowning. Retrieved from https://cchp.ucsf.edu/sites/g/files/tkssra181/f/drownen081803_adr.pdf

[22] Burn Prevention by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain.

[23] Safety and Injury Prevention by Kimberly McLain, Erin K. O’Hara-Leslie, & Andrea C. Wade is licensed under CC BY 4.0

[24] Fall Prevention by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain.

[25] Mayo Clinic. (2020). Fall Safety for Kids: How to Prevent Falls. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/infant-and-toddler-health/in-depth/child-safety/art-20046124

[26] Poisoning Prevention by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain.

[27] Safety Tips for Pedestrians by the Pedestrian and Bicycle Information Center is in the public domain

[28] Child Passenger Safety: Get the Facts by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain

[29] Health and Safety Screener by the Office of Head Start is in the public domain.

[30] Infant/Toddler Learning & Development Program Guidelines by the California Department of Education is used with permission.

[31]Robertson, C. (2013). Safety, nutrition, and health in early education (5th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

[32] Hazard Mapping for Early Care and Education Programs by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain.

[33] Hazard Mapping for Early Care and Education Programs by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain.

[34] 150917-M-UF252-286.JPG by Nathan L. Hanks Jr. is in the public domain.

[35] California Preschool Curriculum Framework Volume 2 by the California Department of Education is used with permission.

[36] California Preschool Curriculum Framework Volume 2 by the California Department of Education is used with permission.

[37] Adventure Playground Natural Free Photo by MadCabbage is in the public domain.

[38] Brussoni, M., Olsen, L. L., Pike, I., & Sleet, D. A. (2012). Risky Play and Children’s Safety: Balancing Priorities for Optimal Child Development. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health , 9 (9), 3134–3148. doi:10.3390/ijerph9093134. Retrieved from https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/9/9/3134

Chapter Seven: Preventing Injury; Protecting Children’s Safety Copyright © by Kelly McKown is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Hughes RG, editor. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008 Apr.

Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses.

Chapter 10 fall and injury prevention.

Leanne Currie .

Affiliations

Fall and injury prevention continues to be a considerable challenge across the care continuum. In the United States, unintentional falls are the most common cause of nonfatal injuries for people older than 65 years. Up to 32 percent of community-dwelling individuals over the age of 65 fall each year, and females fall more frequently than males in this age group. 1 , 2 Fall-related injuries are the most common cause of accidental death in those over the age of 65, resulting in approximately 41 fall-related deaths per 100,000 people per year. In general, injury and mortality rates rise dramatically for both males and females across the races after the age of 85, but males older than 85 are more likely to die from a fall than females. 2–6 Unfortunately, fall-related death rates in the United States increased between 1999 and 2004, from 29 to 41 per 100,000 population. 2 , 7 Sadly, these rates are moving away from the Healthy People 2010 fall-prevention goal, which specifically seeks to reduce the number of deaths resulting from falls among those age 65 or older from the 2003 baseline of 38 per 100,000 population to no more than 34 per 100,000. 8 Thus, falls are a growing public health problem that needs to be addressed.

The sequelae from falls are costly. Fall-related injuries account for up to 15 percent of rehospitalizations in the first month after discharge from hospital. 9 Based on data from 2000, total annual estimated costs were between $16 billion and $19 billion for nonfatal, fall-related injuries and approximately $170 million dollars for fall-related deaths across care settings in the community. 10 , 11 Several factors have been implicated as causes of falls and injuries; to date, however, no definitive predictor profile has been identified. Although the underlying status of the individual who sustains a fall may contribute to the fall and subsequent injury, the trauma resulting from the fall itself is most often the cause of morbidity and mortality.

Over the past 20 years gerontology researchers, spearheaded by Mary Tinnetti from Yale University, have carried out a significant amount of research to address the problem of falls and injuries in the community. However, ubiquitous use of successful interventions is not yet in place in the community. As health care moves toward patient-centered care, and as a growing body of research provides guidance for widespread fall-prevention programs, fall- and fall-related-injury prevention now has the potential to be addressed across the care continuum.

Inpatient fall prevention has been an individual area of concern for nursing for almost 50 years. 12 , 13 Traditional hospital-based incident reports deem all inpatient falls to be avoidable, and therefore falls are classified as adverse events. Indeed, falls are the most frequently reported adverse events in the adult inpatient setting. But underreporting of fall events is possible, so injury reporting is likely a more consistent quality measure over time and organizations should consider judging the effects of interventions based on injury rates, not only fall rates. Inpatient fall rates range from 1.7 to 25 falls per 1,000 patient days, depending on the care area, with geropsychiatric patients having the highest risk. 14–18 Extrapolated hospital fall statistics indicate that the overall risk of a patient falling in the acute care setting is approximately 1.9 to 3 percent of all hospitalizations. 16–18 In the United States, there are approximately 37 million hospitalizations each year; 19 therefore, the resultant number of falls in hospitals could reach more than 1 million per year.

Injuries are reported to occur in approximately 6 to 44 percent of acute inpatient falls. 5 , 20–23 Serious injuries from falls, such as head injuries or fractures, occur less frequently, 2 to 8 percent, but result in approximately 90,000 serious injuries across the United States each year. 20 Fall-related deaths in the inpatient environment are a relatively rare occurrence. Although less than 1 percent of inpatient falls result in death, this translates to approximately 11,000 fatal falls in the hospital environment per year nationwide. Since falls are considered preventable, fatal fall-related injuries should never occur while a patient is under hospital care.

In the long-term care setting, 29 percent to 55 percent of residents are reported to fall during their stay. 24 , 25 In this group, injury rates are reported to be up to 20 percent, twice that of community-dwelling elderly. The increase in injury rates is likely because long-term care residents are more vulnerable than those who can function in the community. 26 Rubenstein 27 reported 1,800 long-term care fatal falls in the United States during1988. The current number of long-term care fatal falls has not been estimated; however, there are 16,000 nursing homes in the United States caring for 1.5 million residents in 2004. 28 This population will likely grow in the coming years, thus fall and injury prevention remains of utmost concern.

- Fall and Fall-Related Injury Reporting