- How It Works

- PhD thesis writing

- Master thesis writing

- Bachelor thesis writing

- Dissertation writing service

- Dissertation abstract writing

- Thesis proposal writing

- Thesis editing service

- Thesis proofreading service

- Thesis formatting service

- Coursework writing service

- Research paper writing service

- Architecture thesis writing

- Computer science thesis writing

- Engineering thesis writing

- History thesis writing

- MBA thesis writing

- Nursing dissertation writing

- Psychology dissertation writing

- Sociology thesis writing

- Statistics dissertation writing

- Buy dissertation online

- Write my dissertation

- Cheap thesis

- Cheap dissertation

- Custom dissertation

- Dissertation help

- Pay for thesis

- Pay for dissertation

- Senior thesis

- Write my thesis

111 Exceptional Foster Care Research Paper Topics

Foster care is not a common topic of discussion in academic papers. Those who handle it may not have enough data or have missing links due to the topic’s limited attention on the internet. Nonetheless, you are here because you have an assignment in this field, and you need impressive foster care topics for your research paper.

This article contains all the best writing ideas for foster care that will make you the top of your class. It is not your ordinary blog article on the internet looking for clicks! On the contrary, it is the product of professionally researched content that will enrich your academic prowess. Watch this space!

How To Write Foster Care Research Paper Topics

Writing foster care research topics is primarily tricky for college and university students who are starting. However, those who have been writing such papers can easily sail through and achieve high grades in the end. Making your professor smile while reading your article starts with eye-catching research. That is why our experts give their all into collating top-notch foster care paper topics.

Do you want fast and professional research topics for your paper? Well, follow the steps below:

Understand the scope of the question Find out your professor’s objective Identify what you know about the question Move on to look at what others say Collate a list of similar work done on the same question Develop an award-winning topic!

The means to success is doing what others are not doing. By following the tips above, you can be sure that you will end up with a great foster care topic that will envy many.

Look at the sample foster care research questions below for your motivation:

Foster Care Research Questions

- What is the importance of foster care on a child?

- What factors are considered for a child to be a candidate for foster care?

- How long does it take for one to register and to be able to foster a child?

- Is there any support given to foster parents?

- What is required for one to be a foster child?

- What measures are put in place to ensure a child’s wellbeing in the foster care system?

- How long can foster the same child?

- What disqualifies a person from fostering?

- In what state should a foster home be in before a minor comes in to live there?

- What are the measures taken in cases of child abuse in foster homes?

- Does one make money from fostering?

- What are the risks of becoming a foster parent?

- How should one respond to the problematic stories surrounding struggling foster families?

- What is the goal of a foster care system?

- How are kids impacted by the trauma they experienced?

- At what age is a child involved in foster care?

- Can children with special needs be involved in foster care?

- What are the rules and regulations for foster care parents?

- How does foster care affect the child’s life stability?

- In what way does the system affect foster children?

- What are the effects of foster children interacting with biological parents?

- How much support should foster parents have?

- How fast is the foster care adoption process?

- What measures should be in place for drug addicts?

Top Foster Care Issues

- Challenges that children in extended foster care experience?

- How the system is dealing with the rising number of children in foster care

- Problems faced in recruiting, training and retaining foster families

- How the foster care agencies get the resources needed to sustain them

- How does the foster care agency handle the sibling issue during adoption

- How orphan children end up in foster care

- How is the safety of a child ensured in the foster homes

- How do foster care agencies deal with child abuse and its effect on the child

- The disruption of child’s schooling due to foster parenting

Top Developmental Issues For Young Children In Foster Care In 2023

- Poor communication between social workers, foster parents and health care providers concerning services

- Public funded programs available for children in foster care

- How long-term foster care has affected children

- What strategies are in force to guarantee a child’s schooling goes on smoothly?

- How maltreatment of children in foster care has increased health care concerns

- Health risks on adolescents in the foster care

- The discrepancy in the number of children resulting with developmental and mental health care needs

- Foster parents training to be therapeutic agents

- Frequent changes experienced by children resulting in the incomplete transfer of information

- Effects of early intervention services on children in foster care

- The development of an orderly growth of the foster care system

- Management of foster care resources and equal distribution

Foster Care Problems

- Challenges faced by students that grew in foster care

- The increase of child abuse in foster care

- Children feeling guilty about separation from birth parents

- On waiting for adoption for a long time, children think unwanted

- Children questioning positive feelings towards foster parents

- The difficulty foster parents experience in letting the child return to birth parents

- Foster parents dealing with the needs of children in their care

- The feel helplessness on a child who has been to several foster homes

- The difficulty of the foster parent to answer medical questions

- Reasons why foster children should have maximum attention

- The parent has a lot of work ensuring they bond with all the children given to her

- Why foster parents do not provide enough support to the foster children

- Mixed emotions affecting foster parents

- Challenges foster parents experiencing when dealing with sponsoring social agencies.

- Dealing with a child’s emotions and behaviour

- Foster parents understanding mixed toward child’s birth parents

- How extensive is the licensing process to foster parents

- The uncertainty about a child’s living situation

- The cost of foster care to the foster parents

Top-Grade Foster Care Essay Topics

- The importance of foster care agencies to the society

- Benefits of the foster care system on the child

- Development and orderly growth of foster care

- How to decrease homelessness of children after foster care

- Problems faced in the social services and their solutions

- Ways of funding foster care organizations

- Positive and negative aspects of foster care

- The role of foster parents to the children

- Effects of long term care with foster parents

- Limitations of foster parents in the child’s everyday life

- How a child in foster care becomes available for adoption

Informative Speech Topics On Foster Care

- The increase of child abuse prevention efforts

- Sensitization of domestic abuse in the society

- Ways to improve foster care around the world

- Problems faced in the foster care system

- Ways to make adoption more accessible and better in the society

- How to make foster care more accessible in the world

- The impact of foster parents on a child’s life

- How better adoption is beneficial to both the foster parent and the child

- Foster care effects on the health of the child

- Why should one go to a foster care

- Ways in which foster care can change for the better

- Conditions that lead one to a foster care

- What next after children in foster homes get to 18 years of age

- The desired outcome of a foster care child

- Advantages and disadvantages of a foster care system

Foster Care Problems And Issues In The US

- How children adopt to foster parents in teenage versus adolescent stage

- The impact of legal regulations on foster care in the United States

- Why foster parents need to exhibit good parenting skills being getting children

- The effect of social perceptions towards foster care

- How social media and other interactive technologies are influencing foster care

- Explain why society should not look down upon foster parents

- Discuss the role of the media in highlighting the plight of foster parents

- Evaluate the distribution of foster care homes in the United States

- Why it is necessary to create awareness on foster care

- The impact of coronavirus on adapting children for foster care

- Why should children homes investigate foster parents

- Are there complications that may arise as a result of foster care

- Why it is necessary to ask the child is taking them to foster care

- Malpractices in the nursing industry towards foster care

- How to encourage children to interact with their peers

- Challenges in finding the right foster parents

- Discuss the impact of stigmatization on foster children

- Discuss the likeliness of foster children ending up as single parents

- Discuss the place of clinical therapy in foster care

- Are there enough legal measures about foster care

- What should the government do to crook foster parents?

We hope you enjoyed our professionally researched topics on foster care. Our proficient ENL US writers are ready to offset your paper any moment from now. Try our cheap research paper writing services for professional results!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Comment * Error message

Name * Error message

Email * Error message

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

As Putin continues killing civilians, bombing kindergartens, and threatening WWIII, Ukraine fights for the world's peaceful future.

Ukraine Live Updates

83 Foster Care Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best foster care topic ideas & essay examples, 🎓 good research topics about foster care, ⭐ simple & easy foster care essay titles, ❓ research questions about the foster care system.

- Children in Foster Care In instances where any or all of the factors are noted in a parental case, it is likely that reunification, despite the protests of a parent, will not be possible given that the government has […]

- Youths Transitioning Foster Care System These problems have led to the necessity of occupational therapy in the foster care systems where they enable the young people aging out of foster care to deal with these issues. We will write a custom essay specifically for you by our professional experts 808 writers online Learn More

- Non-Relative Care Placements for Children in Foster Care Here, the main issues to be addressed are the problems of children who are placed in foster care, the social impact of foster care centers, whether these centers are run as they are supposed, the […]

- New York’s Homeless Children and Foster Care System Foster homes have to also face the challenge of developing the mentalities of the children are their clients, and care should be provided on that basis.

- Foster Care Crisis in Georgia: Children in Substitute Families It decides whether a child is to be placed in foster care or to remain in the home of their caregiver.

- Foster Care System in the “Antwone Fisher” Film What could be done to improve the foster care system today? The foster system failed Antwone because they shifted him from a foster home he had innocently believed and enjoyed to be his birth family […]

- Foster Care of Children With a Different Background The ethical dilemma here was detected later when the social worker was able to contact the child’s mother, who insisted that such behavior was not a sign of anxiety but rather of respect and proper […]

- Healthcare, Human Services and Foster Care in the US Particularly, it is essential to enhance the importance of the caretakers’ role in both the provision of the necessary healthcare assistance to their foster children after the people in question become legal guardians of the […]

- Foster-Care Centers and Public Health Over the past ten years, California spent over $200 million on psychotropic drugs, which is about 70 percent of total foster care drug spending in the US.

- Group Home and Foster Care Forensic Settings The residents of the group home often access treatment through the treatment centers located within the homes. The foster cares are located in areas accessible to the amenities and other resources.

- Attachment Disorder Among Young Children in Foster Care Attachment refers to a deep connection between a child and a primary caregiver that plays an important role in the optimal growth and development of the child with regard to expression of emotions and creation […]

- Foster Care and Adoption Service The role of the human services professional is to understand the behavior and the expectations of each party in the adoption agreement and offer appropriate information to avoid misunderstanding in the future.

- Foster Care in the Criminal Justice System Throughout the history of the United States, the children welfare system has evolved according to shifting values and attitudes about what responsibilities governmental agencies should take in the defence and care of abandoned and abused […]

- African American Extended Families and Kinship Care: How Relevant Is the Foster Care Model for Kinship Care

- Childhood: Foster Care and Young Mothers

- Adoption Subsidies and Placement Outcomes for Children in Foster Care

- Leaving Foster Care: The Influence of Child and Case Characteristics on Foster Care Exit Rates

- Health Outcomes for Adults in Family Foster Care as Children: An Analysis by Ethnicity

- Adopting Children Through the Foster Care System

- Child Protection and Adult Crime: Using Investigator Assignment to Estimate Causal Effects of Foster Care

- Need for Change: The Harmful Effects of the Foster Care System

- Natural Mentoring and Psychosocial Outcomes Among Older Youth Transitioning From Foster Care

- Mental and Emotional Health of Children When Leaving Foster Care

- Cognitive, Educational, and Self-Support Outcomes of Long-Term Foster Care Versus Adoption

- Educational and Employment Outcomes of Adults Formerly Placed in Foster Care

- Trauma Treatments for Among Culturally Diverse Foster Care Youth: Treatment Retention and Outcomes

- Minority Children and Adolescents in Transracial Foster Care

- Balancing Permanency and Stability for Youth in Foster Care

- Risk and Protective Factors for Residential Foster Care Adolescents

- Attachment Theory and Change Processes in Foster Care

- Economics Incentives and Foster Care Placement

- Improved Intelligence, Literacy and Mathematic Skills Following School-Based Intervention for Children in Foster Care

- Foster Care: Protecting Bodies but Killing Minds

- Outcomes for Young Adults Who Experienced Foster Care

- Stability for the Children Leaving the Foster Care System

- Kinship Foster Care: Placement, Service, and Outcome Issues

- Adoption and Family Safety and Foster Care Plan

- New Policy for Getting Therapeutic Foster Care For Children With Mental Illnesses

- Evaluating Housing Programs for Youth Who Age Out of Foster Care

- Adolescent Resilience, Gender, and Foster Care

- Competencies and Problem Behaviors of Children in Family Foster Care: Variations by Kinship Placement Status and Race

- After Parental Rights Are Terminated: Factors Associated With Exiting Foster Care

- Increasing College Access for Youth Aging Out of Foster Care

- Career Readiness Programming for Youth in Foster Care

- Kinship Family Foster Care: A Methodological and Substantive Synthesis of Research

- Child Abuse Prevention and Foster Care

- Foster Care and Adoption as a Tool of Superior Care

- Granting Gay Couples to Adopt Children From Foster Care

- Factors Associated With Reunification: A Longitudinal Analysis of Long-Term Foster Care

- Behavioral Health Needs and Service Use Among Those Who’ve Aged Out of Foster Care

- Differences Between Foster Care and Adoption

- Context Matters: Experimental Evaluation of Home-Based Tutoring for Youth in Foster Care

- Natural Mentoring Among Older Youth in and Aging Out of Foster Care

- What Factors Are Considered for a Child to Be a Candidate for Foster Care?

- Should the Foster Care System Be Reformed?

- What Measures Are Put in Place to Ensure a Child’s Wellbeing in the Foster Care System?

- How Does Foster Care Affect Children?

- Should Race and Culture Matter for Children in Foster Care Place With Adoptive Families?

- What Factors Impact the Educational Outcomes of Children in Foster Care?

- Why Do Children Run Away From Foster Care?

- What Is the Importance of Foster Care on a Child?

- How Long Does It Take for One to Register and to Be Able to Foster a Child?

- Is There Any Support Given to Foster Parents?

- What Is Required for One to Be a Foster Child?

- How Long Can Foster the Same Child?

- What Disqualifies a Person From Fostering?

- In What State Should a Foster Home Be In Before a Minor Comes in to Live There?

- How Is the Safety of a Child Ensured in the Foster Homes?

- What Are the Measures Taken in Cases of Child Abuse in Foster Homes?

- Does One Make Money From Fostering?

- What Are the Risks of Becoming a Foster Parent?

- How Should One Respond to the Problematic Stories Surrounding Struggling Foster Families?

- What Is the Goal of a Foster Care System?

- How Are Kids Impacted by the Trauma They Experienced?

- At What Age Is a Child Involved in Foster Care?

- Can Children With Special Needs Be Involved in Foster Care?

- What Are the Rules and Regulations for Foster Care Parents?

- How Does Foster Care Affect the Child’s Life Stability?

- In What Way Does the System Affect Foster Children?

- What Are the Effects of Foster Children Interacting With Biological Parents?

- How Much Support Should Foster Parents Have?

- What Measures Should Be in Place for Drug Addicts?

- How Fast Is the Foster Care Adoption Process?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, January 21). 83 Foster Care Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/foster-care-essay-topics/

"83 Foster Care Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 21 Jan. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/foster-care-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2023) '83 Foster Care Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 21 January.

IvyPanda . 2023. "83 Foster Care Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." January 21, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/foster-care-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "83 Foster Care Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." January 21, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/foster-care-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "83 Foster Care Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." January 21, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/foster-care-essay-topics/.

- Caregiver Topics

- Attachment Theory Essay Topics

- Homelessness Questions

- Surrogacy Questions

- Child Welfare Essay Ideas

- Motherhood Ideas

- Parenting Research Topics

- Pedagogy Topics

- Social Development Essay Topics

- Family Titles

- Suffering Essay Topics

- Children’s Rights Research Ideas

- Charity Ideas

- Parenting Styles Titles

- Childcare Research Topics

Qualitative studies of the lived experiences of being in foster care: A scoping review protocol

Affiliations.

- 1 Nursing, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria, Australia [email protected].

- 2 Psychology, Victoria University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

- 3 Lighthouse Foundation, Melbourne, Victoria, Austalia.

- 4 Psychology, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia.

- 5 Nursing, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria, Australia.

- 6 Department of Regional Health, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark.

- PMID: 36854595

- PMCID: PMC9980361

- DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-069623

The aim of this scoping review is to provide an overview of the existing qualitative research concerning the lived experiences of children and young people currently in foster care.

Introduction: Lived experience of foster care is an area of limited research. Studies tend to focus on foster caregiver retention rates, education performance outcomes, evaluations and policy development. Although these studies are important, they provide little insight into the everyday lives of those currently in foster care, which is likely to influence these previous areas of research.

Methods and analysis: The scoping review will be guided by Arksey and O'Malley's approach to scoping studies. A systematic database search of PubMed, CINAHL and PsycINFO will be conducted followed by a systematic chain search of referenced and referencing literature. English-language peer-reviewed qualitative studies of children and young people currently in foster care will be included. We will exclude studies linked to transitioning out of foster care and studies with samples mixed with other types of out-of-home care. Mixed-methods studies will be excluded in addition to programme, treatment or policy evaluations. Following removal of duplicates, titles and abstracts will be screened, followed by a full-text review. Two researchers will independently screen references against inclusion and exclusion criteria using Covidence software. The quality of the included studies will be assessed by two independent reviewers using the appropriate Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist.

Ethics and dissemination: Information gathered in this research will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented at national and international conferences relevant to foster care services and quality improvement. Reports will be disseminated to relevant foster care agencies, where relevant. Ethical approval and informed consent are not required as this protocol is a review of existing literature. Findings from the included studies will be charted and summarised thematically in a separate manuscript.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH; QUALITATIVE RESEARCH; SOCIAL MEDICINE.

© Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2023. Re-use permitted under CC BY-NC. No commercial re-use. See rights and permissions. Published by BMJ.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Databases, Factual

- Educational Status

- Home Care Services*

- Qualitative Research

- Review Literature as Topic

Writing papers doesn't always come easy, ordering essays from us does.

My Paper Writer

142 Foster Care Research Paper Topics: Top Ideas

Choosing a great topic is essential for any research project. But a lot of students struggle to come up with ideas and as a result are unable to impress their professor with their assignments. This can be even tougher for ENL students that can have trouble developing original ideas in any discipline. We understand the challenges of this situation and provide some of the best ideas at no cost to help students get a great start toward putting together a top-notch research paper. In this article, our US writers list 142 foster care research paper topics for free. You can modify them to fit any kind of assignment and can share them with other students.

Table of Contents

What is foster care and how do i put together a great research paper, informative speech topics on foster care, foster care problems and issues, research paper topics on the foster care system, list of foster care topics for research paper, foster care topics for research paper.

Students and young professionals interested in going into a career related to foster care should know that it is a structure in which a minor has been planted into a ward, society home, or private home of a state-certified caregiver.

There are many developmental issues for young children in foster care that have given rise to a lot of government-sponsored and independent research. This gives people in this field a lot of opportunities to explore foster care issues and make valuable contributions to improve the system.

You must make sure you do several things to craft a great research paper about foster care. Follow the tips listed below to ensure you receive high marks on your project and effectively present your ideas clearly and concisely:

- Research Your Topic Carefully Using Reputable Sources Start with background research by searching the web for anything related to your topic. Write down source leads and search for in-depth facts and figures from trustworthy sources like government, academic, and certified foster care programs.

- Organize Your Notes, Develop a Thesis, and Create an Outline After your research, you need to gather all the notes you took and ensure that citation information is accurate. Organize the notes into related arguments and select the best ones to support your draft thesis. Finally, create an outline to guide your writing.

- Write the First Draft in One Sitting as Fast as Possible The best way to get started on any assignment is to get the first draft written as fast as possible. This doesn’t mean you can’t take any breaks, but you are encouraged to tackle each section in one sitting and get the first draft written in a few hours.

- Set Your Research Paper Draft Aside for a Few Days After completing your first draft you want to get away from reviewing and rewriting for a few days. Assuming you have adequately planned to complete your project by starting as early as possible, you can take a break from it all together so that you can return feeling refreshed.

- Revise Your Argument and Write a Second Draft The process of revision is to re-imagine your work through a critical lens which must identify areas that need to be strengthened by rearranging, adding, or deleting content. Revise your first draft to make sure you structure and format your work to better present your arguments.

- Set Your Second Draft Aside Before You Edit and Proofread You will likely want to wrap up your assignment soon after you complete your second draft. But you will have more success editing and proofreading if you set your work aside for at least another day. This ensures you will submit the best research paper possible.

You can also use an opportunity to custom college papers and feel free to enjoy more pleasant activities.

An informative speech intends to educate an audience about a particular subject. It should bring up valuable points so that an audience can better understand and remember what they learned later. The following are great foster care essay topics you might want to consider for this kind of assignment:

- Impact on children put in long-term foster care.

- A study of adults that grew in the foster care system.

- The foster care system and its advantages.

- Characteristics of a trustworthy foster care family.

- The rise of adoption rates in the United States.

- Adoption rules for children in foster care.

- Understanding the foster care system pros and cons.

- Race and ethnic prejudice in foster care placement.

- Examining the mission of the foster care system.

- Evaluating the methods used to determine if a child is at risk.

- The impact international adoption has had on the foster care system.

- Examining the ethics of the foster care system.

- The role of foster care agencies in urban areas.

- Understanding the current state of the foster care system.

- Explaining the foster care system to parents wanting to adopt.

- Improvements to the foster care system over the years.

- Foster care for non-English speaking children.

- Examining the current state of the foster care system in the U.S.

- Evaluating the educational system for children in foster care.

- Characteristics of healthy foster care homes.

- Evaluating the safety of foster care homes.

- Principles of the Foster Care Independence Act.

- Requirements to become a parent of a foster child.

- The benefits of the foster care program.

- Mental health concerns for children in foster care.

- The importance of foster care agencies in rural areas.

- Examination of child welfare policies in the U.S.

- Analyze the impact foster care has on marginalized groups.

- The impact federal foster programs have had on low-income communities.

Earlier we discussed how there are numerous foster care problems and issues that students and professionals alike can explore. These occur even among the more reputable foster care organizations. Here are some great ideas you can consider for a research assignment of about 5 – 10 pages long:

- The risks and dangers of a growing foster care system.

- Challenges of getting adequate foster care financial support.

- Analyzing the factors that must be considered for a child to be in foster care.

- Adequate training for foster care parents.

- Length of time it takes for someone to qualify for adoption.

- Financial support for parents of foster children.

- Length of time required to be available to adopt a child.

- The problem with the disparity in the foster care system.

- Determining the need for foster care need for children.

- The problem with homelessness of children after foster care.

- Instances of child abuse for children in foster care.

- Educational problems for children in foster care.

- Issues with separating siblings in foster care.

- Characteristics of the current foster care system.

- Federal support of the national foster care system.

- LGTBQ youth and the risk of homelessness in foster care.

- Inadequate funding for foster care organizations.

- The rights of children in foster care homes.

- Evaluating qualified parents in the foster care system.

- Adoption process for children that come from abusive homes.

- Interstate laws prevent adequate foster care programs.

- Financial disparity among foster care programs.

- The harsh reality of foster care for many children.

- Abusive foster parents and the impact on children.

- Systematic problems in foster care social programs.

- Problems with separating foster care children through adoption.

- Examining the importance of foster care to a child.

- Evaluating the support foster parents receive financially.

These research paper topics about foster care focus specifically on evaluating the system in various settings and situations. Regional or financial challenges often make it difficult to efficiently run a program and these topics cover some of the major issues:

- Foster care effectiveness across the 50 states.

- The problem with older children in foster care.

- The likelihood of success for children in foster care.

- Debate over gay foster care and adoption.

- Separating siblings through the adoption process.

- The effect of social perceptions toward foster care.

- Methods to encourage children to interact with their peers.

- Misconceptions about the behaviors of children in foster care.

- The relationship between foster care and single parents.

- Examination of parenting skills required to foster children.

- Encouraging children in foster care to socialize.

- How to use social media to encourage home placements.

- The stigmatizing of foster parents.

- How teenagers adopt to foster parents in the first three months.

- The impact of legal regulations on the foster care system.

- How children adopt to foster parents in the first three months.

- The importance of mental health for children in foster care.

- Criminal proceedings for abusive foster parents.

- Media and the portrayal of foster parents.

- Analyzing legal measure regarding foster care.

- The importance of clinical therapy in foster care.

- Interactive technologies and their influence on foster care.

- Trust issues in children from foster care homes.

- Challenges in finding the right foster parents.

- The stigmatization of adults coming from foster care.

- Foster parents that abuse the system for financial support.

- The impact social media has on the foster care system.

- Encouraging children to interact with foster care parents.

- Effective placement of children in foster care.

- The role of the social worker in the foster care system.

These are controversial foster care problems that have been in discussion for several years. There are varying viewpoints you can take for each one and you can develop an assignment that will generate a lot of interest and debate:

- Creating effective awareness of the foster care system.

- Problems faced in the foster care system.

- The negative impact Covid-19 has had on foster care.

- Public education and children of foster care.

- Highlighting the plight of foster parents in the U.S.

- Foster care and the relationship with academic success.

- Ways to improve foster care around the world.

- Frequency of foster home visitation and evaluation.

- The need for more qualified parents to foster children.

- The impact of foster parents on a foster child’s life.

- Medical and health negligence for children in foster care.

- Challenges of providing adequate social services to foster children.

- Examining why foster care children are more likely to fail.

- The investigation process for potential foster parents.

- Complications that arise because of foster care.

- Foster care systems in the United Kingdom.

- Analyze the distribution of foster homes in the U.S.

- The positive and negative effects on mental health.

- The challenges of getting more people to adopt.

- Interviewing children in foster care homes.

- Nursing malpractice for children in foster care.

- Advantages and disadvantages of the foster care system.

- The health effects of children coming from foster care.

- Compare and contrast foster care in the U.S. and U.K.

- Analyzing desired outcomes for children in foster care.

- How to make adoption more accessible.

- Examining proposals to improve the effectiveness of foster care.

- Providing social services to foster care children turning 18.

- Increasing efforts to prevent child abuse.

This set of research paper ideas can be modified to fit any kind of assignment of any length. Most cover current issues that are so new that you may have some trouble finding a lot of information. So, you can take the opportunity to be among the first ones to do work in these areas:

- Sensitization of foster care abuse in society.

- The effects of long-term care with foster parents.

- Responding to child abuse and neglect in foster homes.

- Development and orderly growth of foster care.

- Stress issues in parents that foster children.

- The problems in social services for foster care children.

- Foster care system and special needs children.

- Child abuse & neglect among low-income households.

- The financial burden for parents that foster children.

- Children from foster care and the connection with crime.

- Health risks on adolescents in the foster care system.

- Mandatory reporting of child abuse and neglect.

- Feelings of helplessness among children in foster care.

- Mental health in foster care parents.

- Encouraging increased adoption of older children.

- Achieving and maintaining permanency.

- The challenges of providing adequate medical care to children.

- Improving the foster parent licensing process.

- Mental issues related to the adoption of children.

- Providing parent education to strengthen families.

- Examining the signs and symptoms of child neglect.

- Supporting and preserving families.

- Providing out-of-home care for children in the foster care system.

- Providing more attention to children in foster care.

- Partnering with families to improve child welfare outcomes.

- How to improve a child’s chances for adoption.

Foster Care Research Paper Assistance

If you are a college or university student requiring foster care research questions or assistance editing or writing an assignment, our college paper writing service provides custom solutions that will earn you high grades. Our online services will deliver high-quality products fast and we have cheap packages that can fit any student’s budget. Learn more about our services by chat, email, or phone. Our friendly and knowledgeable customer support staff is ready to help.

189 Social Media Research Paper Topics To Top Your Paper

Social media has been around since the late 1990s and refers to the means of interaction and communication between groups of people from all over the world. It allows them to create, share, and exchange information, ideas, and conversations in virtual communities over the internet. Society embraced social media and it was made popular by individuals that wanted to connect with others but quickly became a tool used by businesses and organizations to promote products and services and is now a vital component in building relationships, broadcasting, and marketing at small- and large-scale levels.

- Different Types Of Social Media

- What Goes Into The Structure Of Great Social Media Paper

- Excellent Social Media Research Topics

- Easy Research Topics About Social Media

- Research Papers On Social Media For College

- Social Networks Topics For Graduate Students

- Popular List Of Social Networks Topics For 2023

I requested the editor as I wanted my essay to be proofread and revised following the teacher’s comments. Edits were made very quickly. I am satisfied with the writer’s work and would recommend her services. I requested the editor as I wanted my essay to be proofread and revised following the teacher’s comments. Edits were made very quickly. I am satisfied with the writer’s work and would recommend her services.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Secure the top grades, with vetted experts at your fingertips.

A national campaign to improve foster care

- Download the report

Subscribe to the Center for Economic Security and Opportunity Newsletter

Ron haskins ron haskins senior fellow emeritus - economic studies.

June 22, 2017

- 13 min read

In the U.S., it remains an unfortunate reality that many children—including those born to low-income parents whose families live in poor neighborhoods with low-quality schools or who are members of minority groups—are statistically disadvantaged from the moment of birth or even earlier. Though some are able to break out and achieve educational and economic success, the odds are stacked against these children—now more than ever.

Among this already disadvantaged group of children, one subgroup stands out for the accumulation of factors that work against them enjoying a happy and normal childhood or beating the odds to achieve a fulfilling life as an adult characterized by a stable family, a good job, and financial independence. These most unfortunate and at-risk children are those removed from their homes by local officials and placed in the nation’s foster care system. These are the most disadvantaged children in the nation, and therefore have the greatest claim to public support.

The magnitude of the problem is shown by a recent survey that found that nearly 40 percent of the nation’s children experienced a child protective services investigation by age 18. 1 In 2014 alone, reports to public authorities documented child abuse or neglect allegations affecting 3.2 million children. 2 Not all children who are victims of abuse or neglect are identified when the maltreatment occurs—and even fewer receive services—but every state has a public entity, often called the Department of Social Services (DSS), that investigates these reports of abuse or neglect and, in the cases that the local DSS finds to be most serious, formulates and executes a plan for helping the parents and the child improve their relationship and reduce the problems that led to the maltreatment.

In the most serious cases of abuse or neglect, DSS may remove children from their parents and place them in a setting outside their family household, sometimes in a group or institutional care setting, sometimes with a relative, and sometimes with another family that has been determined to meet at least minimum standards of being able to provide an adequate environment for raising the child. About 260,000 children enter foster care each year; at any given moment, a total of around 400,000 of the nation’s children are in foster care. 3

The needs of children in foster care

Imagine the emotional condition of children who enter foster care. Before entering care, nearly all of them experience trauma that can have serious and sometimes lasting impacts on their development and personality. Once placed in foster care, their contact with their own parents is greatly reduced, at least temporarily. Although child welfare agencies are supposed to keep children in their home communities and in their own schools if possible, achieving these two placement goals is often difficult, in which case children may be placed in a new neighborhood where they must go to a new school and make new friends. Thus, children who already face many disadvantages can lose major parts of their familiar environment while facing what must seem to them an uncertain and deeply confusing future.

It is little wonder that these children, when studied over many years, have outcomes in education, delinquency, mental health, employment, and many other areas that are far below average. One of the best studies of the long-term impacts of foster care and the conditions that cause children to enter foster care followed about 730 adolescents who were in foster care at age 17 in Iowa, Wisconsin, and Illinois. They were followed until they reached age 26. The authors’ conclusion provides a clear picture of the fate of many of these young people who experienced years in foster care:

The picture that emerges . . . is disquieting, particularly if we measure the success of the young people . . . in terms of self-sufficiency during early adulthood. Across a wide range of outcome measures, including postsecondary educational attainment, employment, housing stability, public assistance receipt, and criminal justice system involvement, these former foster youth are faring poorly as a group. . . . Our findings raise questions about the adequacy of current efforts to help young people make a successful transition out of foster care. 4

Research in recent decades has established that for most children, their parents are the most important influence on their development. 5 Parents establish and maintain most parts of the preschool child’s rearing environment and have more interactions with the child than any other person. Parents establish the child’s daily routines, listen to and talk to the child more than anyone else, and are the child’s original source of information and values. But just as children who enter foster care come from neighborhood and school environments that are less than ideal, their home environments—including their parents—are also unlikely to have supported normal child development. Most enter foster care already carrying emotional—and often physical—scars.

How foster care placement works

Precisely because parents are so important to children’s development and well-being, when children are removed from their parents by public officials, the public assumes responsibility for their development and well-being. For the approximately 260,000 children placed in foster care each year, the choice of foster care setting is central to the child’s future.

There is now almost universal agreement that group or institutional care should be considered an option of last resort. 6 In 2014, a group of ten leading child welfare researchers with extensive careers of research on children felt so strongly about this issue that they issued a “consensus statement” on group care. Their conclusion, stated with admirable conciseness, is that children should be placed in group care only “when necessary therapeutic mental health services cannot be delivered in a less restrictive setting.” 7 Nonetheless, according to a report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, nearly 15 percent of children are placed in group homes or institutional care. 8

Far preferable to group care is placement with a qualified, loving family. Two types of placements with families are used by child welfare offices across the nation. In one type, children are placed with family members, often grandparents. This mode of placement has been used for centuries and is today a form of foster care endorsed by child welfare agencies, government agencies responsible for administering child welfare programs, and child welfare professional organizations. 9 There are two major factors that make kinship placements so desirable: First, children are usually familiar with the adults with whom they will be living. Second, both the parents and the child experience less trauma if the child is placed with someone known to and trusted by the parents and the child. About 30 percent of children in foster care are in kinship care.

Many families whose children enter foster care do not have relatives available or able to provide reliable and loving care to the child. Thus, DSS agencies find families—usually unknown to the child and the child’s family—that are willing to devote themselves to the care and nurturing of the child. Children placed with foster families are often traumatized, especially if they have been living in difficult circumstances with their biological family for many years. Thus, the children often act out and are resistant to adult supervision. As every parent knows, raising children is always challenging. But raising a foster child can be especially challenging due to the unique needs of foster children and tensions with parents who have lost temporary custody of their children. Both conditions weigh heavily on foster parents.

Given these challenges, DSS agencies have a demanding task in selecting, training, and certifying foster parents who can stand up to these various pressures—and all so they can serve a child and family they don’t know. Despite these barriers, however, placement with non-relative families is the most common placement type: 45 percent of foster children live with non-relative foster families.

A national campaign to catalyze foster care reform

Given the stakes, and our nation’s public responsibility for providing the best possible care for these abused and neglected children, a group of child welfare advocates, researchers, community activists, and foundation officials have initiated a national campaign called CHAMPS (CHildren need AMazing ParentS) to ensure bright futures for children in foster care by promoting the highest quality foster parenting.

To achieve this goal, CHAMPS will work with state policymakers, child welfare administrators, and advocates to leverage research and spur policy reforms in up to 25 states over the next five years.

As spelled out in detail in a paper published in 2016 by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, 10 the reforms are aimed at:

- Building a robust constituency network and enhancing the capacity of advocates to effectively push for quality foster parenting through a broad-based coalition equipped with the latest evidence and tools.

- Reforming state policies, including changes to statutes, administrative codes, and regulations, to increase public and private agency capacity to support, engage, recruit, and retain foster parents. Policy approaches will vary by state, but will include steps to promote quality caregiving, ensure accountability and oversight, and create more effective partnerships between parents and agencies.

- Promoting stronger federal policies that firmly embed the principle that children do best in families. Federal policy approaches might include fiscal incentives and greater state accountability measures to ensure the availability of trained and qualified foster parents to meet the needs of children and communities.

- Changing the public narrative about foster parents to emphasize the vital role that they play in a child’s life. By leveraging survey data, as well as the voices of foster parents, youth who have experienced foster care, and other community leaders, the public will gain greater understanding and appreciation of foster parents.

The Center on Children and Families (CCF) at Brookings is pleased to announce its participation in the project as the research arm of the CHAMPs initiative.

With financial and advisory support from several foundations, CCF will examine four key issues that are well-aligned with the aims of the CHAMPS reforms outlined above.

First, we will conduct research on the quality of foster care offered by states. We are especially interested in research on how the quality of foster care can best be measured and on the relationship between quality measures and child progress and outcomes. Measures of the quality of foster care should correlate with, or even cause, the most important outcomes such high school graduation, attaining a post-high school degree or certificate, avoiding teen pregnancy, and avoiding delinquency and criminal involvement.

Second, we plan to examine the best ways to determine state accountability for their foster care systems, especially the capacity of states to conduct oversight and evaluation of the services they are offering. We will focus attention on how the federal government and the states now measure accountability and how the measures could be improved. Again, as with measures of the quality of foster care, measures of state accountability should be highly correlated with desirable child outcomes.

Third, we will explore ways to increase the American public’s understanding of the vital role played by foster parents and the great value of the services they provide to foster children. Increasing the visibility of foster parents and promoting a greater understanding of their vital role in preparing the nation’s most disadvantaged children for adulthood will increase the number of parents who are interested in the possibility of serving as foster parents as well as political support for public initiatives to improve foster care.

Fourth, as shown by a visit to the California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare, 11 in recent decades program specialists and researchers have developed a number of programs capable of successfully treating the types of serious emotional and behavioral problems that afflict many of the children who wind up in foster care. The field needs to know more about these intervention programs and how foster parents can play an important role in improving the success of these programs in helping foster children. A special focus of our research will be figuring out how to adapt these treatment programs to the individual strengths and weaknesses of foster families so that the impact of the programs in reducing emotional and behavioral problems can be improved.

The Center on Children and Families at Brookings looks forward to playing a contributing role in the national movement to help states improve the quality of foster parenting for abused and neglected children through aggressive implementation of the CHAMPS initiative. There are few public policies for which the potential payoff in lives brightened is as promising as improvements in the nation’s foster care system.

- Hyunil Kim et al., “Lifetime Prevalence of Investigating Child Maltreatment among US Children,” American Journal of Public Health , 107 (2017): 274-280.

- U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Ways and Means, “Child Welfare,” in Green Book (Washington: Committee on Ways and Means, 2016).

- Mark F. Courtney et al., “Midwest Evaluation of Adult Functioning of Former Foster Youth: Outcomes at Age 26” (Chicago: Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago, 2011).

- Richard V. Reeves and Kimberly Howard, “The Parenting Gap” (Washington: Brookings Institution, 2013); Ariel Kalil, “Addressing the Parenting Divide to Promote Early Childhood Development for Disadvantaged Children” (Washington: The Hamilton Project, 2014); Michael E. Lamb, “Mothers, Fathers, Families, and Circumstances: Factors Affecting Children’s Adjustment,” Applied Developmental Science 12 (2012): 98-111.

- Fred Wulczyn et al., “Within and Between State Variation in the Use of Congregate Care” (Chicago: Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago, June 2015); Annie E. Casey Foundation, “Every Kid Needs a Family: Giving Children in the Child Welfare System the Best Chance for Success” (Baltimore: Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2015); Richard P. Barth, “Institutions vs. Foster Homes: The Empirical Base for a Century of Action” (Chapel Hill, NC: Jordan Institute for Families, June 2002).

- Mary Dozier et al., “Consensus Statement on Group Care for Children and Adolescents: A Statement of Policy of the American Orthopsychiatric Association,” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 84 (2014): 219-225.

- All placement estimates are taken from the Department of Health and Human Services, “The AFCARS Report: Preliminary FY 2015 Estimates as of June 2016,” No. 23, accessed June 10, 2017, https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/afcarsreport23.pdf .

- Children’s Bureau, Child Welfare Information Gateway, “Kinship Caregivers and the Child Welfare System” (Washington: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau, 2016), accessed June 10, 2017, https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/f-kinshi/ ; “Kinship Care,” Child Welfare Leagues of America, accessed June 10, 2017, http://www.cwla.org/our-work/advocacy/placement-permanency/kinship-care/ .

- Annie E. Casey Foundation, “A Movement to Transform Foster Parenting” (Baltimore, MD: Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2016).

- See California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse for Child Welfare, http://www.cebc4cw.org/ .

Children & Families

Center for Economic Security and Opportunity

Nariman Moustafa

October 20, 2023

Anusha Bharadwaj

September 29, 2023

Sophia Espinoza, Charlotte Wright, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek

July 18, 2023

Advertisement

Fatherhood in Foster Care: A Scoping Review Spanning 30 Years of Research on Expectant and Parenting Fathers in State Care

- Published: 18 May 2022

- Volume 39 , pages 693–710, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Justin S. Harty ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2770-6869 1 &

- Kristen L. Ethier ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2881-4626 2

3548 Accesses

4 Citations

49 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Over the past 30 years, there has been a surge of interest in understanding the experiences and outcomes of expectant and parenting foster youth. Despite the importance of understanding this unique population of foster youth, there remains a lack of research on fathers in foster care. Most studies of expectant and parenting foster youth focus on mothers in care, and studies that have examined fathers in care provide little insight compared to what we know about mothers. Furthermore, existing research on fathers in foster care is limited by underreporting, service engagement issues, lack of meaningful engagement data, and very little information on fathers’ involvement with their children. There is very little published research on the experience of fatherhood in foster care or on related outcomes for fathers in care such as residency with children, father engagement with children, coparental relationship quality, or the health and well-being of their children. While there have been over 60 studies and three reviews on expectant and parenting foster youth spanning roughly 30 years, the articles have primarily focused on empirical findings relating to mothers in foster care. Information on fathers in foster care has received little attention and is restricted to empirical studies. This scoping review aims to fill this gap by examining the available information on fathers in foster care. To this end, our scoping review explores empirical findings and knowledge from practice-, legal-, and policy-related literature related to fathers in foster care from peer-reviewed journal articles, reports, dissertations, white papers, and grey literature published between 1989 and 2021. Findings from 94 sources of evidence on expectant and parenting foster youth suggest that mothers in foster care are consistently the focus of the literature. If fathers in foster care are included in the literature, findings or guidance are often provided in the aggregate (e.g., parents in care). However, when aggregated, literature still focuses on mothers in care, or female pronouns are used to describe the larger expectant or parenting foster youth population. Many of the studies excluded fathers, and the primary exclusion rationale includes a lack of identified fathers in care, unreliable child welfare data on fathers, or high attrition of fathers in parenting services. In terms of information on fathers in foster care by the source of evidence, research papers often provided quantitative descriptions of fathers, practice papers focused on rights of fathers, legal papers centered on paternity establishment or paternal rights, and policy papers largely discussed the need for improved data tracking and interventions for fathers. More research is needed to support fathers in foster care as they transition out of care into early adulthood and young fatherhood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Engaging Fathers in Child Welfare and Foster Care Settings: Promoting Paternal Contributions to the Safety, Permanency, and Well-being of Children and Families

Engaging At-Risk Fathers in Home Visiting Services: Effects on Program Retention and Father Involvement

Sandra McGinnis, Eunju Lee, … Rose Greene

“Foster Care is a Roller Coaster”: A Mixed-Methods Exploration of Foster Parent Experiences with Caregiving

Taylor Dowdy-Hazlett & Shelby L. Clark

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Youth in foster care have an increased likelihood of becoming parents as compared to their non-foster care peers (Courtney & Dworsky, 2006 ). Parenting while in foster care is associated with a variety of risk factors for young parents and their children, including adverse outcomes in education (Courtney & Hook, 2017 ), employment (Dworsky & Gitlow, 2017 ), housing stability, mental health (Matta Oshima et al., 2013 ) and criminal justice involvement (Shpiegel & Cascardi, 2015 ), and intergenerational maltreatment (Dworsky, 2015 ). As such, young parents in foster care have garnered the attention and concern of scholars, policymakers, and child welfare practitioners, including 30 years of research on this population. Relatively little attention has been paid to the outcomes, experiences, and needs of young fathers in care. The lack of research on fathers in foster care may stem from limitations in survey and child welfare administrative data to accurately capture reports of males impregnating females or fathering a child when paternity is unreported, disputed, or unknown. Further, research indicates that many young fathers in foster care are dually impacted by child welfare and criminal justice involvement (Shpiegel & Cascardi, 2015 ), which may constrain researchers’ abilities to connect with young fathers in foster care for rigorous qualitative research. Furthermore, research on young fathers (e.g., adolescent, teenage) broadly indicates that young fathers have unique needs related to their delayed entry into the labor force, lower academic achievements, and decreased developmental readiness for paternal obligations, which may affect their ability to meet traditional fatherhood expectations (Johnson Jr., 1998 , 2001a , 2001b ).

There are three existing literature reviews on expectant and parenting youth in foster care, which collectively review research published between 1989–2017. Each of these reviews covers research that includes a sample of only young mothers or a sample of both young mothers and young fathers together. None of the three reviews covers research that includes a sample of only young fathers. Svoboda et al. ( 2012 ) examined literature on parenting youth in foster care published from 1989–2010, identifying common themes across the 16 quantitative and qualitative studies reviewed. The authors note variation across studies in reported rates of pregnancy and impregnation, ranging from 16 to 50% of youth in care who either became pregnant or impregnated someone while they were in foster care. Common themes across the studies include barriers and opportunities, diverse mental and physical health needs of parenting youth, the influence of traumatic life experiences on sexual development, the influence of poverty, and the disruption of relationships and living environments. Although nine of the sixteen studies included fathers in the sample, the authors did not identify any implications for research or policy related to young fathers in foster care. Connolly et al. ( 2012 ) conducted a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies published on expectant and parenting youth in foster care in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. They identified risk factors, protective factors, and markers of resilience across 17 studies published between 2000–2010. The authors identified several themes related to what they identify as the experiences of young mothers in foster care, including (1) infants filling an emotional void (2) lack of consistent sexual education, (2) motherhood adversities, (4) mistrust of others and social stigma, (5) perception of motherhood as positive and stabilizing (6) internal strengths and wanting to do better, and (7) support contributing to positive motherhood. Interestingly, the Connolly et al. ( 2012 ) review focuses on the findings and implications of the studies solely for young mothers in foster care and their children. However, of the studies reviewed that are based in the United States, the majority included young fathers in foster care in the sample, but father-specific findings were not discussed. In the most recent literature review on this population, Eastman, Palmer, et al. ( 2019 ), Eastman, Schelbe, et al. ( 2019 )) reviewed 18 studies on young parents in care published between 2011 amd 2017. Of the studies reviewed, nine included fathers in the sample. Although the authors highlighted some of the findings on expectant and parenting males in care, no father-specific recommendations for child welfare policy, practice, or future research were made.

Across the three reviews, 19 studies included fathers in the sample. However, few studies reviewed identified implications specifically for young fathers and their children, and the existing reviews are similarly disengaged from father-related findings. As such, there are three notable gaps in current understandings of the research on young fathers in foster care. First, current reviews have not thoroughly analyzed the existing body of research published from 1989 and 2017 in terms of father-related findings, including some publications omitted from prior literature reviews. Second, additional research on expectant and parenting youth in foster care has been published from 2018–2021 and has yet to be reviewed for father-related findings. Third, none of the existing literature reviews include research exclusively focused on young expectant and parenting males in foster care. The objective of this scoping review is to address each of these gaps in order to identify the risks, experiences, and needs of young fathers in foster care with implications for child welfare policy, practice, and research. Furthermore, this scoping review seeks to explore in detail the available information on young fathers in foster care spanning the last 30 years. This 30-year span covers the oldest study (Polit et al., 1989 ) included in the first review of research on expectant and parenting foster youth by Svoboda and colleagues ( 2012 ) to the most recent studies reviewed in this scoping review (Dworsky et al., 2021 ; Martínez-García et al., 2021 ; Rouse et al., 2021 ; Shpiegel, Day, et al., 2021 ; Shpiegel, Fleming, et al., 2021 ).

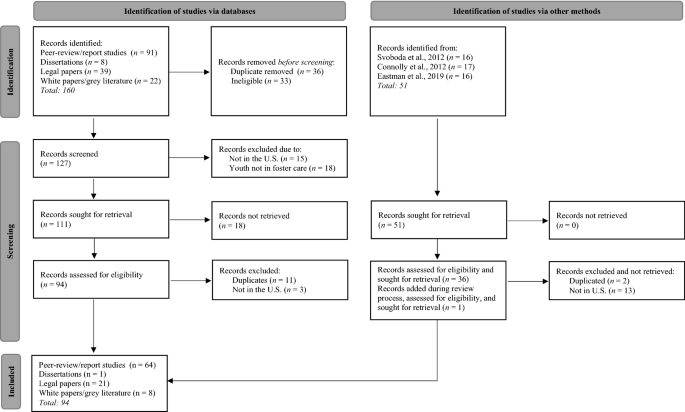

This scoping review began with the establishment of a research team consisting of the two authors of this paper who have practice and research experience with expectant and parenting youth in foster care. We collaborated on identifying the research question for this scoping review, including target audiences, search terms, and databases to conduct the searches. The methodology we used for this scoping review was based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Protocols extension for scoping reviews framework (Tricco et al., 2018 ). We completed a detailed review protocol for our scoping review but did not register it. Registering scoping reviews is recommended but not required to reduce duplication of research and for transparency (Tricco et al., 2018 ). However, we choose not to register our scoping review protocol due to the simplicity of our inclusion criteria (i.e., research containing any findings or information on fathers in foster care). Due to the scarcity of research on fathers in foster care, we were not concerned with the duplication of a research review on this topic. However, if one were to occur, we would welcome the possibility of different conclusions or alternative sources of evidence on this topic. To ensure transparency, our review protocol can be obtained from the primary author upon request and we detail the methods of our scoping review in the next section.

This study is a scoping review of expectant and parenting fathers in foster care. However, we decided to include expectant and parenting mothers in foster care in this scoping review as well. Given that our decision may seem perplexing, we believe that our rationale for including mothers in foster care in this scoping review is warranted. Scoping review methodology is used for variety of purposes (Peterson et al., 2017 ; Pollock et al., 2021 ). Two primary purposes of a scoping review are to provide an overview of a field of research (Moher et al., 2015 ; Pham et al., 2014 ) and to identify gaps in existing literature (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005 ; Sucharew, 2019 ). Our scoping review aligns with these purposes in two ways. First, we aimed to provide an overview of the field of research on expectant and parenting foster youth, examining the extent of research done on fathers in foster care. Second, we aimed to identify gaps in existing literature on expectant and parenting foster youth as they relate to fathers in foster care. To achieve these two aims, we review literature on expectant and parenting foster youth broadly (e.g., literature including mothers, fathers, or both) to ascertain the degree to which fathers in foster care are included in research literature (e.g., main sample or comparison group) or white/grey literature (e.g., principal focus or related focus).

Research Question and Purpose

Our scoping review was guided by the research question, “What are the research findings on or guidance for working with expectant and parenting fathers in foster care?” The purpose of our review was to search, identify, and summarize the literature on fathering foster youth that is relevant to research, legal, policy, and practice audiences.

Eligibility Criteria

Documents were eligible for inclusion if they contained one or more of the following elements of information on expectant or parenting fathers in foster care: (1) research findings, (2) legal guidance, (3) policy guidance, or (4) practice guidance. We included documents if they were published between 1989 and 2021, written in English, based in the United States, and either peer-reviewed journal articles, reports, dissertations, white papers, or grey literature. We included documents if they used quantitative, qualitative, mixed-method, or art-based research methodologies. In addition to the eligibility criteria stated above, we included any peer-reviewed publications or report studies that included only pregnant or parenting mothers in foster care and studies in which the gender of the parent in foster care was not clearly stated (e.g., “parents in foster care,” “parenting youth in foster care”). We expanded the eligibility criteria of peer-reviewed publications and reports to include studies on mothers in care and studies that may include fathers in care for comparative purposes (e.g., obtain the proportion studies including fathers in care versus solely mothers in care). For white papers and grey literature, we excluded any documents that made ambiguous or minimal references to fathers in foster care (e.g., “services should include parents in care,” “services should include mothers and fathers in care”).

Information Sources and Search Strategies

To identify potentially relevant documents, we searched the following online bibliographic databases in May and June of 2021: Google Scholar, Google, ArticlesPlus, PubMed, EBSCO, Web of Science, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, and HeinOnline. We used Google Scholar, Scite.ai, ConnectedPapers, and Dimensions.ai to conduct forward and backward citation searches. We searched Google Scholar, ArticlesPlus, PubMed, EBSCO, Web of Science, and HeinOnline for peer-reviewed research studies, reports, and legal publications. We searched ProQuest Dissertations & Theses for dissertation studies and searched Google for white papers, grey literature, and other reports not captured in earlier database searches. We developed and used a combination of the following Boolean search terms for each search to ensure that results were relevant to our research question and search: “adolesc*” OR “teen*” OR “young” OR “youth*” AND “father*” OR “mother*” OR “parent*” OR “expect*” OR “preg*” AND “in care” OR “foster care” OR “child welfare” OR “child protection” OR “child protective.” We searched databases for these Boolean search terms in the title, abstract, full-text, or keywords. The searches were conducted by both authors of this paper.

Selection of Sources of Evidence

Following the search, we conducted a two-phase selection process. In the first phase, we identified possible citations, collected citation data, uploaded citation data (e.g., title, author(s), journal, abstract, and DOI/URLs) into Zotero 5.0, and removed duplicates. In the second phase, we screened citations by assessing the citation data against the eligibility criteria for our review. We retrieved the online full-text of potentially relevant sources, read the text, and assessed the text against the inclusion criteria. We used different selection processes for each source of evidence that matched our eligibility criteria. For peer-reviewed publications and reports, we automatically included a study or report if they were reviewed in previous review studies (i.e., Connolly et al., 2012 ; Eastman, Palmer, et al., 2019 ; Svoboda et al., 2012 ). We also included any peer-reviewed publications and reports that met our eligibility criteria and were published but not reviewed in previous review studies (between 1989 and 2017), as well as peer-reviewed publications and report studies published after the 2017 eligibility year cut-off for the Eastman, Palmer, et al. ( 2019 ) and Eastman, Schelbe, et al. ( 2019 ) review (between 2018 and 2021). When peer-reviewed publications and report studies met our eligibility criteria, we conducted forward and backward citation searches to find additional studies for inclusion based on our eligibility criteria. We selected dissertations, white papers, and grey literature if the publications met our eligibility criteria and had distinct findings or guidance for fathers in foster care. Each author reviewed eligible studies for selection as sources of evidence. We resolved disagreements on publication selection through review and discussion.

Data Charting and Item Extraction

We developed and used a data-charting form to collect, track, and assess data variables to extract. We independently charted the data, discussed the results, and continuously updated the data-charting form in an iterative process based on information contained in the publications that varied based on the type of publication and target audience. We extracted data items from the publications included in our scoping review using a data extraction tool we developed. The data items we extracted from publications included specific details on the topic of the publication (e.g., expectant fathers, fathering, father rights), study sample (e.g., fathers, mothers, both), study context (e.g., research, policy, legal), research findings (e.g., for fathers, mothers, both), and implications (e.g., suggestions for future research, practice guidance).

Synthesis of Results

We grouped the studies by the type of publication and audience. We synthesized peer-reviewed research studies, report studies, and dissertations together for research audiences. We grouped legal studies together for law and advocacy audiences. Lastly, we grouped policy and practice-focused white papers and grey literature together for policy- and practice-related audiences. When we found reviews on pregnant, expectant, and parenting youth in foster care, we noted how many studies may have been missed or excluded from previous reviews and how many studies were published outside of year ranges covered in previous reviews. When we synthesize findings from peer-reviewed studies and report studies that were reviewed in previous review studies (Connolly et al., 2012 ; Eastman, Palmer, et al., 2019 ; Svoboda et al., 2012 ), we focus on synthesizing father-specific findings, study procedures, and implications.

As shown in Fig. 1 , after our initial search, we identified 160 sources of evidence. Thirty-six sources of evidence were duplicates of studies we found in our databases searches and studies we included from previous reviews on pregnant, expectant, and parenting youth in foster care (Connolly et al., 2012 ; Eastman, Palmer, et al., 2019 ; Svoboda et al., 2012 ) that met our eligibility criteria. Thirty-three sources of evidence were removed that did not meet eligibility criteria. We were then left with 127 sources of evidence that we reduced down to 93 after reviewing sources of evidence that did not meet eligibility criteria ( n = 18). During the review process, we added one source of evidence (grey literature) at the suggestion of a reviewer that we missed during the screening process. Of the 94 sources of evidence we included, 64 were peer-review or report studies, 1 was a dissertation, 21 were legal papers, and 8 were either white papers or grey literature. The selected articles highlighted six areas of interest regarding expectant and parenting male youth in foster care: (1) incidents of impregnation by males in foster care; (2) predictors and characteristics associated with fathering while in foster care; (3) risk factors of early fatherhood in care; (4) elements of fathering roles while in foster care; (5) legal rights of fathers in foster care; and (6) practice with fathers in care.

Identification and selection of sources of evidence

Review of Peer-Reviewed and Report Studies Reviewed in Previous Review Studies