An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

- PMC10135437

Spanning Borders, Cultures, and Generations: A Decade of Research on Immigrant Families

The authors review research conducted during the past decade on immigrant families, focusing primarily on the United States and the sending countries with close connections to the United States. They note several major advances. First, researchers have focused extensively on immigrant families that are physically separated but socially and economically linked across origin and destination communities and explored what these family arrangements mean for family structure and functions. Second, family scholars have explored how contexts of reception shape families and family relationships. Of special note is research that documented the experiences and risks associated with undocumented legal status for parents and children. Third, family researchers have explored how the acculturation and enculturation process operates as families settle in the destination setting and raise the next generation. Looking forward, they identify several possible directions for future research to better understand how immigrant families have responded to a changing world in which nations and economies are increasingly interconnected and diverse, populations are aging, and family roles are in flux and where these changes are often met with fear and resistance in immigrant-receiving destinations.

INTRODUCTION

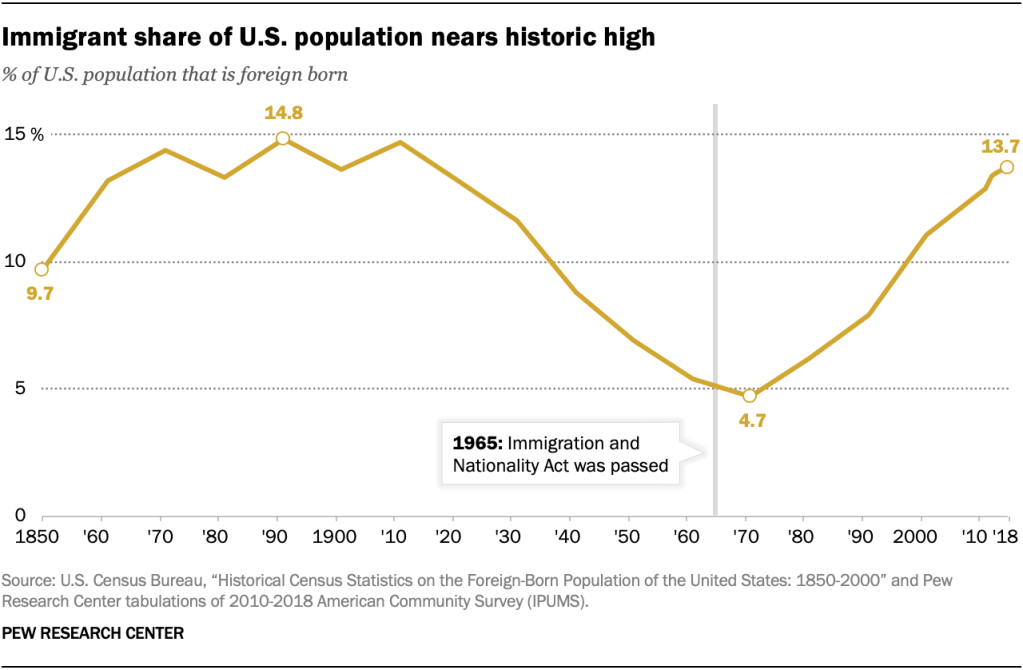

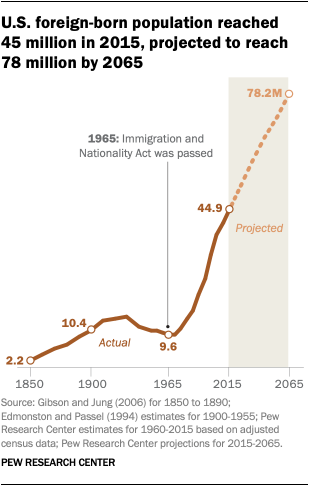

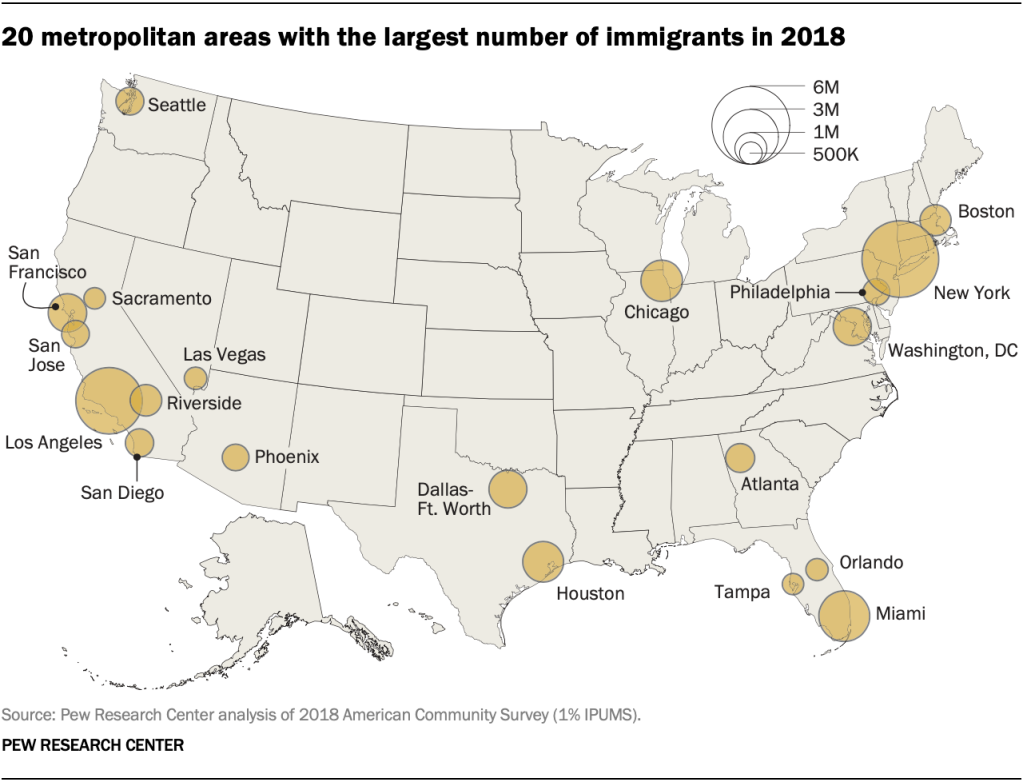

Approximately 244 million people globally live in a different country from where they were born, and increasing shares of the populations of North America, Europe, and the Middle East are immigrants ( International Organization for Migration, 2017 ). The decision to migrate—to move from one context to another—shapes the family life course. Not only do immigrants face a series of choices and constraints that determine when and where they can move but also families are impacted by this migration whether they remain in the origin community, move as a unit, or are formed in the place of settlement.

Our goal is to engage with the following question: How does migration shape families? To better understand how migration might influence families, it is helpful to consider that some forms of immigration entail a permanent move for any of a variety of reasons, such as to take a new job, join other family members living in the destination country, or flee danger. For these migrants, migration not only disrupts family processes but it also poses new challenges for families as they settle and assimilate in destination settings. Another form of migration, circular migration, is a response to competition from global markets and limited opportunities in the local area ( Massey, Alarcón, Durand, & González, 1990 ). Enacted as a strategy for managing financial risk, generating income, and building savings, parents or other household members migrate in search of better-paying work, often leaving other household members behind. All types of migrants maintain family ties in their countries of origin, but circular labor migrants are particularly likely to do so. This form of migration can bring resources in the form of remittances to households in the sending region, but often at the cost of the absence of a parent, child, or spouse. In addition, this type of migration tends to be accompanied by the flow of new ideas from destination to sending regions, often altering family norms and raising expectations for upward mobility among both migrants and among those remaining behind ( Levitt, 1998 ). The past decade has witnessed a growth of scholarship on all of these migration patterns, and research focused on sending and receiving contexts are now joined by studies and data collection efforts designed to understand how families navigate important ties between these contexts ( Mazzucato & Schans, 2011 ).

This article reviews recent scholarship on immigrant families with a focus on key points in the family life course. This has been an exciting decade of scholarship on immigrant families and migration around the globe (e.g., Foner & Dreby, 2011 ; Kulu & González-Ferrer, 2014 ). Recognizing that we cannot cover it all, we focus on themes that have emerged in the pages of the Journal of Marriage and Family ( JMF ) in the past decade. Although many of the studies that we cite were published in JMF , we also draw on work published in other outlets when it connects closely to the JMF themes. Our review is focused primarily on research in the United States and the sending countries with close connections to the United States, but we include studies on similar themes from other contexts to highlight where we see theoretical and methodological similarities and challenges for the field as a whole.

We organize the review according to key family processes, paying attention to both sending and destination settings. We begin with research focused on family formation, including schooling and union formation, couple relationships, and childbearing. This work illustrates the importance of the demographic, socioeconomic, and political conditions in flux across sending and destination contexts. We then turn to the challenges of parenting and the complexity of parent–child relationships in the context of migration. This is by far the largest body of work represented in JMF in the past decade on immigrant families. Finally, we address research on kin care and intergenerational family ties. This research has important implications for how people care for one another in an aging and mobile world. We conclude with some thoughts about the future of immigration and family dynamics and suggestions of key areas in need of new research, where we challenge scholars to consider how immigrant families continue to respond to the changing world around them.

FAMILY FORMATION

Transition to adulthood in sending communities.

In previous decades, research has focused on the timing of migration during the life course, often exploring how migration may interrupt school or family formation for migrants (e.g., Landale, 1994 ; McKenzie & Rapoport, 2006 ; Singley & Landale, 1998 ). In the past decade, work on the impact of parental migration on the children left behind has grown. For adolescents left behind in sending communities, parental labor migration is often associated with increased opportunities to attend school and delayed home leaving and marriage. The financial remittances sent by migrants can be used for schooling expenses and can substitute for children’s wages, freeing them to attend school ( Antman, 2012 ; Lu, 2012 ). Thus, parental migration can change the trajectory of human capital acquisition, family formation, and migration among young adults.

However, parental labor migration is not always linked with increased educational attainment of these youth (e.g., Creighton, Park, & Teruel, 2009 ). In one study of “left behind youth” in China, the migration of siblings was positively associated with children’s education, but parental migration was not, suggesting remittances are beneficial but parental presence is also important—a theme we return to when we address parenting below ( Lu, 2012 ). Recent research has explored the conditions under which parental migration can reduce children’s educational trajectories despite the apparent positive impact of remittances, such as when parental absence means that children have less time for school work and studying ( Meng & Yamauchi, 2017 ), or when children live in advantaged communities where private schooling, and the accompanying fees, is unnecessary ( Sawyer, 2016 ). Clearly, the role of parental migration for children’s schooling and educational attainment is not universal across or within migrant-sending countries ( Jensen, Giorguli Saucedo, & Hernández Padilla, 2016 ; Lu, 2014 ).

One important source of variation is the different role migration can play in the education, work, and life transitions of girls and boys. For example, remittances can substitute for bridewealth, allowing daughters in Mali ( Hertrich & Lesclingand, 2012 ) and Mozambique ( Chae, Hayford, & Agadjanian, 2016 ) to delay marriage and continue their schooling. For boys in communities where labor migration by men is very common, adolescents may drop out of school early to find work abroad ( McKenzie & Rapoport, 2006 ) and spend less time on school-work and work more outside the home ( Antman, 2011 ), but these studies are based in contexts such as Mexico and Central America where men are the traditional breadwinners and use labor migration to fulfill their breadwinner roles to provide for their families ( Nobles & McKelvey, 2015 ). We should expect gender differences to evolve over time; as female migration becomes more normative, this is likely to shift the schooling, family formation, and migration plans of girls remaining behind ( Arias, 2013 ).

The influence of migration also extends beyond economic returns as migrants share information about the opportunities and challenges found in their destination ( Levitt, 1998 ). Such social remittances shift orientations to individual self-fulfillment and can shape normative family formation patterns among the young people left behind ( Acharya, Santhya, & Jejeebhoy, 2013 ; Juarez, LeGrand, Lloyd, Singh, & Hertrich, 2013 ; White & Potter, 2013 ). Research on young adults is needed to clarify how their own ideas about family formation change in the context of migration.

Transition to Adulthood in Destination Settings

Past research has extensively explored how immigrant adolescents traverse the transition to adulthood in destination settings (e.g., Kasinitz, Mollenkopf, Waters, & Holdaway, 2009 ; Portes & Rumbaut, 2001 ; Waters, 2009 ; White & Glick, 2009 ). Research in the past decade continues to show how this critical part of the life course is strongly shaped by generational status and social acculturation, socioeconomic status, and discrimination (e.g., Haller, Portes, & Lynch, 2011 ; Jeong, Hamplová, & Le Bourdais, 2014 ; Treas & Batalova, 2011 ) both in the United States and in Europe (e.g., Engzell, 2019 ).

A newer theme in this area of study has been on the role of immigrants’ legal status and immigration enforcement in the United States. Gonzales (2011) describes the anguish of undocumented young adults as they become aware of the limitations they will face as undocumented adults. They are excluded from many American rites of passage and opportunities, such as obtaining a driver’s license, going to college, and attaining a professional occupation. These youth face high uncertainty and interruptions in their trajectory as they move into adulthood ( Suárez-Orozco, Yoshikawa, Teranishi, & Suárez-Orozco, 2011 ). Evidence of lower educational attainment among undocumented youth when compared with other foreign-born youth persists even when controlling for other family background characteristics and socioeconomic status ( Bean, Brown, & Bachmeier, 2015 ; Greenman & Hall, 2013 ). Other research, however, reveals that legalization initiatives—such as the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program—may not necessarily expand educational opportunities for these youths ( Amuedo-Dorantes & Antman, 2017 ; Hsin & Ortega, 2018 ). More research on the effects of unauthorized status, DACA, and other policy options on home leaving, union formation, and childbearing would be valuable.

Union Formation

Another important part of the transition to adulthood is cohabitation and marriage. Similar to past research on how generational status shapes partnering behaviors ( Bean, Berg, & Van Hook, 1996 ; Brown, Van Hook, & Glick, 2008 ; Oropesa & Landale, 2004 ), much of the recent work on this topic interprets generational patterns in marital behaviors through an assimilation lens. For example, interracial unions between whites and other groups continues to be interpreted as an indicator of assimilation, consistent with Gordon (1964 ; Lee & Bean, 2010 ; for direct evidence of the association between acculturation and interracial marriage, see also Chen & Takeuchi, 2011 ). For women in the second generation, endogamy within parental national origins appears to signal adherence to more traditional division of roles by gender, whereas second-generation women in exogamous relationships engage in less traditional roles and have higher labor force participation ( McManus & Apgar, 2019 ).

Recently, researchers have also found evidence for alternative interpretations beyond generational assimilation ( Lichter & Qian, 2018 ). For example, Yodanis, Lauer, and Ota (2012) found that some people in interracial relationships actively seek partners from other cultures because they are attracted to interesting experiences and lifestyles, and not because group differences are small and socially insignificant. Interracial marriages may also feature unequal power relationships formed between lower status men who seek foreign wives because of ethnic stereotypes that such women are submissive ( Choi, Cheung, & Cheung, 2012 ). More research on couple relationships in interracial unions would be valuable, especially in couples with inherent power imbalances such as marriages between legal and undocumented immigrants ( Dreby, 2015a ) or between U.S.-born men and “mail order” brides. Indeed, limitations on driving licenses and jobs pose barriers for undocumented young men’s ability to follow gendered scripts for dating and may slow their transitions to marriage based on these legal constraints. For young women, limitations posed by legal status are more apparent as they transition to marriage and motherhood where barriers to services challenge the gender script of being a good wife or mother ( Enriquez, 2017 ).

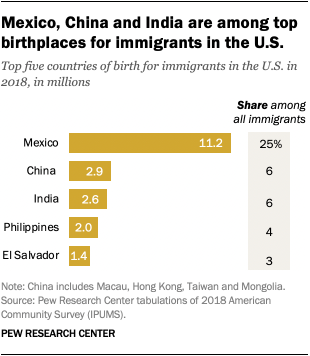

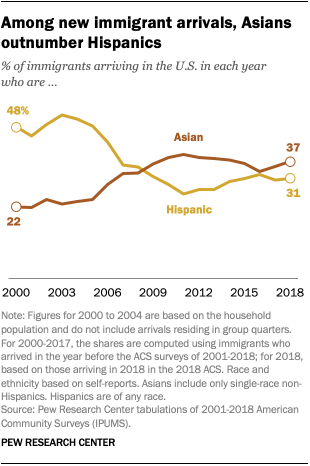

Researchers are also exploring how large-scale immigration has altered U.S. marriage markets. Intermarriage of Hispanics and Asians with Whites has leveled off in the past 2 decades while marriages between U.S.-born and foreign-born individuals has increased ( Qian & Lichter, 2011 ). This is largely attributable to large-scale new immigration in the 1990s and 2000s, which increased the availability of Hispanic and Asian singles in marriage markets ( Choi & Tienda, 2017 ; Lichter, Carmalt, & Qian, 2011 ) and in new immigrant destinations ( Qian, Lichter, & Tumin, 2018 ). As we look forward, we note that couples are increasingly likely to meet through online match services ( Lin & Lundquist, 2013 ), meaning that the composition of local marriage markets may impose fewer constraints now than in the past. It is an open question as to whether these virtual marriage markets increase or decrease interethnic or interracial unions.

Finally, it is important to consider nonmarital cohabitation as it becomes an important family form and children are increasingly likely to have cohabiting parents ( Brown, Stykes, & Manning, 2016 ). Past work has examined rates of cohabitation across race/ethnic and generational groups ( Brown et al., 2008 ), but more work is needed to understand how the meaning of cohabitation differs across groups. On one hand, there are commonalities that cut across groups. For example, interracial and interethnic unions with Whites are more common among cohabiting unions than marriages across a range of national origin and ethnic groups ( Qian, Glick, & Batson, 2012 ). This may be due to the less formal nature of cohabiting unions compared with marriage and a weakening of gender and family formation norms from the countries of origin ( McManus & Apgar, 2019 ). On the other hand, consensual unions and cohabitation are more common in some countries of origin and may be observed more frequently among some national origin groups than others ( Esteve, García-Román, & Lesthaeghe, 2012 ; Fomby & Estacion, 2011 ; Yu & Xie, 2015 ). This implies that the social support and acceptance for nonmarital unions may be higher among some immigrant groups than others and the impact of family structure on children may vary according to norms in parents’ country of origin. For example, in a study of low-income families in the United States, cohabitation was less strongly associated with children’s externalizing behaviors among those with foreign-born mothers when compared with those with U.S.-born mothers ( Fomby & Estacion, 2011 ). More research is clearly needed to help elucidate how cohabitation fits into patterns of assimilation and adaptation for immigrant families and children.

Couple Relationships

In the “new economics” theoretical perspective of circular labor migration, household members are portrayed as making consensual agreements to diversify risks, whereby one spouse migrates for work while other household members stay home to work and raise children ( Massey, 1999 ). This consensual view of immigrant families has been criticized in the past (e.g., Boyd & Grieco, 2003 ; Frank & Wildsmith, 2005 ; Hondagneu-Sotelo, 2003 ; Kanaiaupuni, 2000 ). Research in the past decade has continued to complicate the consensual view by showing how migration and prolonged spousal separation can erode intracouple relationships.

Distance and structural barriers, such as increased border security, limit the ability of migrants to return and maintain contact with spouses and children left behind. Long periods of separation, often extending for several years, is associated with weakening relationships, union dissolution, and the formation of new sexual partnerships in places of origin and destination ( Dreby, 2010 ; Landale, Oropesa, & Noah, 2014 ; Nobles, Rubalcava, & Teruel, 2015 ). Much of this research has been conducted on Hispanics, so these findings may not extend to other groups (e.g., Caarls & Mazzucato, 2015 ). For example, in contexts where women are more likely to migrate for work and leave spouses behind in the origin setting, migration may challenge traditional gender roles and create strain on couples beyond the strain of maintaining a transnational relationship ( Hoang & Yeoh, 2011 ).

Migration can also strain couple relationships for couples who live together in the destination country. Gender roles within couples may initially reflect those in immigrants’ sending countries and may be modeled from their parent’s relationships ( Kuo et al., 2017 ; Updegraff, Perez-Brena, Baril, McHale, & Umaña-Taylor, 2012 ), but these patterns fade with time in the destination country, as shown in studies conducted in Canada ( Frank & Hou, 2015 ) and Europe ( Pessin & Arpino, 2018 ). These changes may not come easily ( Hou, Neff, & Kim, 2018 ). For example, in a study of Iranian immigrants in Canada, men faced challenges adjusting to new gender roles and shifts in division of labor at home in response to women’s labor force participation ( Shirpak, Maticka-Tyndale, & Chinichian, 2011 ).

It would be valuable to extend prior work on how couple relationships and women’s roles change as a consequence of migration, particularly work that enables systematic comparisons across national origins with varying degrees of gender inequality. In doing so, it is important to account for selection into immigration to better separate the effects of migration from factors that lead to migration given that power dynamics within couples have been observed to influence the decision to migrate ( Nobles & McKelvey, 2015 ; Tucker, Torres-Pereda, Minnis, & Bautista-Arredondo, 2013 ). Comparisons across destination contexts could also be valuable. For example, in a qualitative study of Mexican immigrant women’s isolation and autonomy in Montana, Ohio, and New Jersey, Dreby and Schmalzbauer (2013) found that Mexican immigrant women’s relationships with their husbands or partners were less important in places with a concentrated Mexican population and social services infrastructure.

Childbearing

As with intermarriage, research on immigrant fertility and transitions to parenthood in prior decades looked to assimilation theory (e.g., Bean, Swicegood, & Berg, 2000 ; Parrado & Morgan, 2008 ). This approach was predicated on the observation that fertility rates tend to be higher among foreign-born than U.S.-born women, particularly among Hispanics ( Pew Research Center, 2015 ). Higher fertility norms from sending countries may play a role in the higher fertility of immigrants, as found in a study of Canada ( Adsera & Ferrer, 2014 ). Among Hispanics in the United States, fertility declines with generational status ( Parrado, 2011 ), and the perceived value of children is higher among foreign-born Hispanics than non-Hispanic Whites ( Hartnett & Parrado, 2012 ). Nevertheless, fertility is rapidly declining across Latin America and Asia ( Laplante, Castro-Martín, Cortina, & Martín-García, 2015 ; Raymo, Park, Xie, & Yeung, 2015 ), so we urge researchers to be cautious about continuing to assume that immigrants are likely to have higher fertility than natives or of attributing their fertility behaviors to pronatal values in their countries of origin, which may no longer exist ( Frank & Heuveline, 2005 ).

First, it is worth noting that fertility among Hispanic women has declined rapidly in the past few years ( Pew Research Center, 2016 ) and that much of the postrecession decline in period fertility rates in the United States is due to declines in fertility among Latina and Hispanic women ( Seltzer, 2019 ) as well as declines among foreign-born women. Second, the higher fertility that has been observed among foreign-born women in the past has been shown to be at least partially attributable to the timing of their childbearing and not to overall higher completed family size. For women who migrate during young adulthood, childbearing tends to be disrupted or delayed by migration, but once couples are reunited and settled in the destination country, childbearing may increase as couples make up for lost time. Parrado (2011) argued that the relatively high levels of period fertility rates observed among first-generation Hispanic women was largely attributable to this pattern of “catch-up” fertility. Still more evidence comes from research on how women feel about unintended births. In national surveys, Hispanic women report greater happiness about unintended births than African American or White women ( Hartnett, 2012 ), a result that could be interpreted as evidence of greater pronatal values among Hispanics. Yet qualitative interviews revealed more ambivalence than shown in quantitative data. In face-to-face interviews, Hispanic immigrant women revealed that they were actually not particularly happy about unwanted or mistimed pregnancy ( Aiken & Trussell, 2017 ).

A related area of research is adolescent childbearing. Although teen childbearing has been observed to be quite high among children of immigrants for some groups ( Haller et al., 2011 ), children of immigrants of all racial/ethnic groups have lower rates of teen childbearing than third or higher generation peers largely because they delay sex longer ( Goldberg, 2018 ). This may be related to close parent–child relationships within immigrant families. Killoren, Updegraff, Christopher, and Umaña-Taylor (2011) found significant linkages between Mexican-origin adolescents’ close relationships with their mothers and fathers, deviant peer affiliations, and sexual intentions. Foreign-born adolescents were less influenced by peers than their U.S.-born peers, suggesting that immigrant parents exerted greater influence than U.S.-born parents on whether their child considers having sex.

IMMIGRATION AND PARENTING

Parenting children in origin settings.

As the globe becomes more interconnected, the number of children living in migrant-sending households has increased worldwide ( DeWaard, Nobles, & Donato, 2018 ). Indeed, migration has become the most common form of father absence from the home in Mexico ( Nobles, 2013 ). Accompanying these demographic shifts has been a growing body of research on the challenges facing parents and children in migrant-sending households. This work points to the importance of parental separation and absence on child well-being ( Creighton et al., 2009 ; Nobles, 2011 ) and seeks to better understand the competing mechanisms through which migration can impact children.

On the surface, there may be little reason to expect parental absence via migration to produce different outcomes for children than other types of parental absence, but parental absence due to migration implies a different motivation for the absence (i.e., selection) when compared to parental mortality, union dissolution, or nonmarital fertility. For transnational families, the decision to migrate and the sacrifices made to remit resources back to the origin household are made with the intention of improving children’s lives ( Abrego, 2009 ; Dreby & Stutz, 2012 ), and there is evidence of positive outcomes when parents migrate across locations although results vary across different child outcomes. For example, in Tanzania, paternal migration was associated with better odds of child survival than paternal absence due to nonmarital birth, although this was not the case for children’s likelihood of entering school ( Gaydosh, 2017 ). One possible explanation for this finding is that parents who migrate are likely to be emotionally tied to the origin household in a way not found among those who are absent from the household following divorce or separation (e.g., Nobles, 2011 ). This is not to say that parenting strategies are constant. Parents may need to modify their approaches to accommodate distance and the challenges of parenting from afar. One study found that Mayan migrant parents provided consejos (advice) to their children rather than mandados (directives) because they were unable to enforce any such directives from a distance ( Hershberg, 2018 ).

Nevertheless, there are important variations in the impact of parental migration and, again, there is a need to consider factors such as gender and conditions in destination settings. For example, Abrego (2009) found that children in Salvadoran households with mothers who migrated to the United States received more in remittances than children whose fathers migrated despite the greater barriers and hardships reported by female migrants when compared with their male counterparts. The impact of mothers’ versus fathers’ migration is not the same everywhere. In a comparative study of children in the Philippines, Nigeria, and Mexico, migrating mothers were more likely to maintain engaged parenting in Mexico and Nigeria, but mothers who migrated from the Philippines were less engaged with origin households ( Jordan, Dito, Nobles, & Graham, 2018 ). Also, for children in Indonesia and Vietnam, paternal migration was more associated with psychological distress than maternal migration or living in a nonmigrant household, but in the Philippines there was no evidence of psychological distress regardless of which parent migrated or when compared with children in nonmigrant households ( Graham & Jordan, 2011 ). More theoretical and empirical work is required to reconcile these findings.

Parenting in Destination Settings

Low income, low parental education, low English proficiency, discrimination, and their newcomer status pose challenges to immigrant parents and their families in the destination setting, yet family scholars have consistently found that immigrant families provide unique advantages to children (e.g., Bravo, Umaña-Taylor, Zeiders, Updegraff, & Jahromi, 2016 ; Crosnoe, Ansari, Purtell, & Wu, 2016 ; Leidy, Guerra, & Toro, 2010 ). In an effort to understand this paradox, recent research on Mexican-origin families has unpacked the ways that these families function. This work traces the pathways through which cultural values—such as emphasis on family support and obligations—are associated with high-quality parental relationships that in turn reduce acculturative stress and help enhance child well-being and functioning ( Knight et al., 2011 ; Leidy, Parke, Cladis, Coltrane, & Duffy, 2009 ; Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro, Bámaca, & Guimond, 2009 ; Umaña-Taylor, Wong, Gonzales, & Dumka, 2012 ; Zeiders, Updegraff, Umaña-Taylor, McHale, & Padilla, 2016 ). Similar results were found among children of immigrants in England, Germany, the Netherlands, and Sweden ( Mood, Jonsson, & Låftman, 2017 ). The benefits of high-quality family relationships can extend to grandchildren, as shown in a series of studies that explore how Mexican American grandparent–parent relationships can enhance adolescent mothers’ parenting efficacy ( Bravo et al., 2016 ; Derlan, Umaña-Taylor, Updegraff, & Jahromi, 2018 ; Umaña-Taylor, Guimond, Updegraff, & Jahromi, 2013 ).

Although immigrant families buffer children from external risks and stressors, they are not fully immune to them. Prolonged exposure to discrimination, neighborhood poverty, and crime can strain parents and their families ( Benner & Kim, 2009 ). For example, White, Roosa, Weaver, and Nair (2009) found that fathers’ perceptions of neighborhood danger were related to depression, which in turn was related to less warmth in parenting for girls. Father’s perception of neighborhood danger was also related to less family cohesion, harsher parenting, and internalization problems for children ( White & Roosa, 2012 ). This work suggests that immigrant parents’ efforts to protect children may come at the expense of heightened risk for internalizing problems for children.

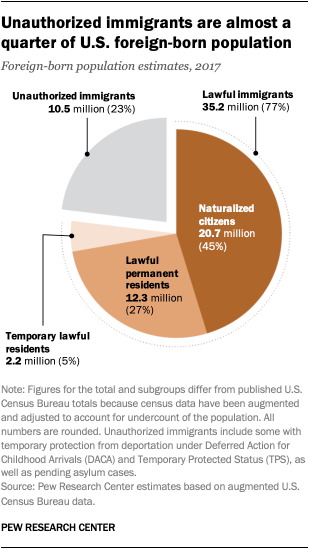

In addition to these stressors, many immigrant families contend with the possibility that a family member could be deported. In the United States, approximately 5 million children younger than age 18 live with at least one unauthorized immigrant parent ( Capps, Fix, & Zong, 2016 ), and many more children know at least one undocumented immigrant in their larger social network. In an era of ramped-up immigration enforcement and deportations both at the border and interior parts of the country, several family scholars have recently shifted their focus to the impact of immigration enforcement on immigrant families (e.g., Yoshikawa, 2011 ).

The most severe impact of immigration enforcement in the United States is family separation ( Dreby, 2010 , 2015a ). The relationship between immigration enforcement and family separation is actually quite complex. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the escalation of border enforcement was associated with a growth in the number of undocumented families in the United States. Border enforcement increased the costs (and thus reduced) circular labor migration and ultimately led to a reduction in the number of transnational families as women and children joined undocumented family members in the United States ( Hamilton & Hale, 2016 ). Once living in the United States, however, undocumented parents risk separation from their children due to deportation ( Amuedo-Dorantes & Arenas-Arroyo, 2019 ). The cycle repeats itself as deported parents who are separated from their U.S.-resident children are more likely to risk another undocumented trip than those who do not have children in the United States ( Amuedo-Dorantes, Pozo, & Puttitanun, 2015 ).

Parental deportation has more negative effects on children than other kinds of separation in part because the deportation of a parent is associated with the loss of both the parent and the financial resources the parent would have contributed to the household ( Dreby, 2015b ). Parental separation and other factors associated with having an undocumented parent negatively affects children’s emotional and behavioral development ( Allen, Cisneros, & Tellez, 2015 ; Bean et al., 2015 ; Brabeck & Sibley, 2016 ; Lu, He, & Brooks-Gunn, 2018 ; Yoshikawa & Kalil, 2011 ), although evidence of the pathways through which parental legal status impacts children is not entirely clear and may be context dependent ( Noah & Landale, 2018 ).

It is also useful to consider the spillover effects of immigration policies. Dreby (2012 ; p. 831) described a “deportation pyramid” to illustrate the far-reaching impacts of these policies. Alhough relatively few children (at the tip of the pyramid) experience the most severe consequences, the deportation of a parent and permanent family dissolution, many more children (at the base of the pyramid) experience other more diffused impacts such as fear of family instability, confusion over the impact legality has on their lives, and the conflation of immigration status with being undocumented or “illegal” in children’s minds. Undocumented legal status is also thought to impact parenting, for example, by restricting travel, limiting the extent to which parents access public programs and benefits on behalf of their children, and living in fear of the police (especially while driving; Berger Cardoso, Scott, Faulkner, & Barros Lane, 2018 ; Dreby, 2015b ; Enriquez, 2015 ; Yoshikawa, 2011 ). These restrictions limit the financial resources and opportunities of undocumented parents, which in turn spillover to their U.S.-born children, which led Enriquez (2015) to label the immigration enforcement policies of the U.S. government “intergenerational punishment.” Bean et al. (2015) provided evidence that the negative impacts of parental undocumented status significantly delayed the assimilation and socioeconomic integration of Mexican Americans by at least a generation.

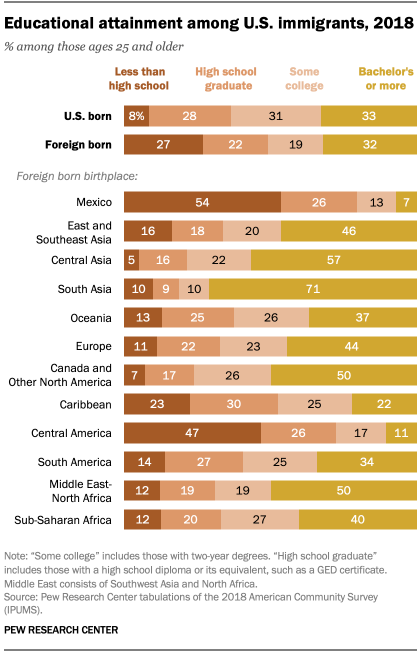

Launching the Second Generation

An important part of parenting is to prepare children for adulthood, and in today’s information-driven economy, it is increasingly vital that parents support children as they seek and acquire education. Immigrants face the challenge of raising their children in a context with new social institutions and expectations from their own upbringing. A long line of research in the United States shows that immigrant parents of all national origins tend to have (very) high educational aspirations and expectations for their children, yet not all groups of children experience equal success in school ( Lee & Zhou, 2015 ; White & Glick, 2009 ). Perhaps because of this, the bulk of recent research on children of immigrants’ educational attainment tends to look beyond the family to how broader social and institutional contexts (e.g., related to state funding policies for undocumented students, English-language acquisition policies, mentoring, discrimination, and peer influences) matter for children’s success in school.

Some recent studies have explored how immigrant parents could more effectively support their children’s efforts in school, often focusing on the “concerted cultivation” parenting behaviors that are associated with school readiness and success among American parents ( Glick, Hanish, Yabiku, & Bradley, 2012 ; Lareau, 2011 ; p. 2). Crosnoe et al. (2016) found that Latina immigrant mothers were less likely than other groups to engage in school-based activities, enroll children in extracurricular activities, and provide educational materials at home—all indicators of concerted cultivation. Furthermore, they found that this is related to Latina immigrant mothers’ lower educational attainment. Indeed, Latina mothers who increased their own education during adulthood also increased their involvement in their child’s education, which is likely, at least in part, attributable to the enhancements in mothers’ understanding and confidence in interacting with U.S. educational institutions ( Crosnoe & Kalil, 2010 ). Low educational attainment and limited familiarity with U.S. schools may explain why the children of mothers who arrived in the United States during adolescence have lower early school performance and socioemotional development when compared with those whose mothers arrived as young children themselves ( Glick et al., 2012 ; Glick, Bates, & Yabiku, 2009 ).

Sending Communities

The share of elderly is increasing in nearly every world region and is projected to continue to rise during the next several decades, including in Asia and Latin America ( Bengtson, 2018 ). Adding to the challenges of an aging world is the migration of young adults away from communities of origin. Research conducted in the past decade has explored how the migration of young adults has altered long-standing family roles and support systems. For one, child-care burdens may increase for grandparents. For example, Chinese rural-to-urban migrants often leave their young children in the care of their parents ( Chen, Liu, & Mair, 2011 ), and similar caregiving arrangements are made in Mexico and Central America. This practice is likely to change parenting and grandparenting roles in sending communities and may contribute to worse child outcomes given that aging grandparents may be unable to effectively supervise young children. It is less clear how such arrangements affect grandparents’ health and financial well-being.

At the same time that aging parents take on additional child-care responsibilities, their child’s migration may also mean that they lack care providers for themselves ( Foner & Dreby, 2011 ; Yahirun & Arenas, 2018 ). In China, where sons have traditionally been expected to care for aging parents, families have had to adapt to changing circumstances. For example, one study examined the frequency of contact with parents ( Gruijters, 2017 ). Although migrant children were unable to frequently visit their parents due to distance, they could leverage new forms of communication technology to maintain intensive social relations with them. Interestingly, this was true for both sons and well-educated daughters, a finding the authors attributed to changing gender norms in China. Research should continue to explore how the migration of adult children affects the health and well-being of elderly parents and in turn how kinship support systems adapt to changing conditions. Comparative research across various sending contexts would be especially valuable.

Destination Contexts

Migration can also alter kin support practices in destination countries ( Van Hook & Glick, 2007 ), as occurs when older parents migrate to be closer to their children and grandchildren and to receive care themselves (see the review by Treas & Gubernskaya, 2016 ). In 2017, 148,000 people were admitted to the United States under the “parent” family reunification criteria, roughly 13% of all lawfully admitted immigrants ( U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2018 ). As with young children and parents, family reunification and proximity to adult children can restore familial contact and care (e.g., Steinbach, 2013 ).

However, older immigrants’ expectations and needs for care also create tensions within families. Immigrants’ adult children are often busy with their work and children and may have adopted more Americanized, individualistic views of kin-care obligations ( Mendez-Luck, Applewhite, Lara, & Toyokawa, 2016 ). Vallejo (2012) described how middle-class, U.S.-born Mexican Americans felt internal conflict about their obligations to support aging parents and poorer relatives, leaving little money or time for themselves or their own children. Interestingly, older immigrants who migrated at younger ages may adjust their expectations for care. Sun (2014) described how Taiwanese immigrants reconfigured their expectations for care from adult children. The respondents reflected that they could rely on the elder care industry as other Americans and excused their U.S.-born children from familial care obligations because they were “Americanized” and had busy lives.

We anticipate that elder care for immigrants will become an increasingly important research topic. This is particularly the case for immigrants who lack citizenship and legal status because they are often ineligible for the social safety net programs that Americans routinely rely on, such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. Two decades ago, very few unauthorized immigrants were elderly. Most returned to their sending communities after working for a few years or they legalized in the early 1990s under the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act ( Baker, 1990 ). However, unauthorized immigrants are now much more likely to settle permanently ( Massey, Pren, & Durand, 2016 ), and the U.S. government has provided very few opportunities for unauthorized immigrants to legalize in recent decades. As a consequence, the number of elderly unauthorized immigrants is likely to increase considerably if no new legalization programs are enacted. As we touch on in the next section, new proposals to limit family reunification criteria for immigrant admissions could further strain the ability of immigrant families to care for elderly parents.

As we reflect on the work on immigrant families published in the past decade, we recognize several important advances in the field. First, more research has focused on immigrants’ sending communities, thus acknowledging the links between immigrants who live in destination communities and the situations and contexts from which they came as well as their families left behind in sending countries. Much of this work has focused on how parental migration affects children left behind, and it generally points to the benefits of remittances flowing back to migrant-sending families for children’s health, schooling, and well-being, but also reveals the costs incurred due to parental absence despite efforts by parents to maintain contact with children from afar.

Second, the context of reception in destination communities shapes family relationships and can limit opportunities for families to migrate together, reunite, and remain together after migration ( Eremenko & González-Ferrer, 2018 ). For example, the presence of an immigrant community and established social service infrastructure in new destination communities may reduce the importance of couple and family relationships for women’s independence and autonomy, thus shaping gender relations among couples ( Dreby & Schmalzbauer, 2013 ). Immigration restrictions and enforcement activity also has the capacity to weaken immigrant family support networks. Increased border security in the United States has made it costlier for undocumented immigrants to return home for vacations and short visits. Ultimately, the end of circular migration has led to prolonged family separation across borders. In destination contexts, immigration enforcement, sanctions against undocumented immigrants, and anti-immigrant animus and discrimination has altered parenting, limited children’s opportunities, created fears of deportation and parental separation, and derailed young adults’ life plans.

Third, family researchers have documented how the acculturation and enculturation process operates as families settle in the destination setting and raise the next generation. Much of this work has focused on Hispanic families—Mexican origin most often—and has employed longitudinal, multiple-reporter designs that explore the ways in which Mexican American parents pass along ethnic identities and values their children and in turn how and in which circumstances these parenting practices influence children’s socioemotional outcomes and their effectiveness as parents themselves. This work helps explicate the longstanding understanding that familistic values in Mexican American families are associated with warm and close parent–child relationships and better socioemotional outcomes for children. At the same time, however, this work underscores how external stressors, such as neighborhood crime, poverty, and discrimination, can wear down these defenses.

The insights gained into migration and family dynamics in the past decade have been possible through creative data harmonization and collection efforts as well as more concerted efforts to communicate and integrate quantitative and qualitative studies, but all of these efforts also yield potentially dozens of fruitful avenues for future research. Next we describe six new directions and unanswered questions for researchers going forward.

Diversity Among Immigrant Families

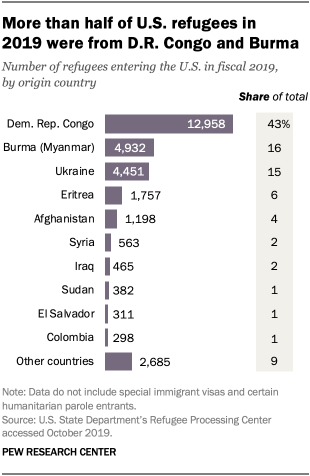

Immigrants in the United States have become increasingly diverse in terms of their race/ethnicity and national origins. The decline in Mexican migration in recent years has been accompanied by increases in families from Africa and Asia. The research on interethnic union formation is notable for exploring the effects of these changes. Research on educational patterns in the United States has also compared across broad ethnic groups, but for research on intrafamilial functioning, there have been fewer groups represented. In addition, very little research has focused on non-heterosexual, LBGTQ immigrants and their families, even though they may face unique challenges as many face discrimination in both their origin and destination country and must navigate legal systems that often fail to recognize their rights as married couples and parents ( Carrillo, 2018 ). Attending to the diversity of culture, race, socioeconomic status, gender, and sexual orientation will help us understand the extent to which the family processes and acculturation patterns observed in prior work are universal or whether they are contingent on a unique set of constraints or circumstances. Data collection projects in the United States such as the Immigration and Intergenerational Mobility in Metropolitan Los Angeles and Immigrant Second Generation in Metropolitan New York have allowed for comparisons across diverse groups in the same destination setting (e.g., Kasinitz et al., 2009 ) and facilitated theoretical and empirical work that seeks to better explain differential outcomes across national origin diverse groups ( Luthra, Waldinger, & Soehl, 2018 ).

Connections Across Borders

Migration networks have continued to proliferate around the globe ( Czaika & De Haas, 2014 ; Mazzucato & Schans, 2011 ). Accordingly, research has extended beyond analyses of one community at a time to consider the connections across borders between sending and destination communities. We have learned a great deal about the challenges of maintaining transnational family ties, but the results from comparative research have yielded complex and varied conclusions (e.g., Alba & Foner, 2015 ; Mazzucato et al., 2015 ). Children’s outcomes, gender patterns of migration, and intergenerational family roles all vary across these contexts.

New data collection and data harmonization efforts have yielded better opportunities to compare family dynamics across various migration contexts ( Alba & Foner, 2015 ; Jordan et al., 2018 ; Mazzucato & Schans, 2011 ). For example, DeWaard et al. (2018) pulled together data from the Latin American Migration Project and Mexican Migration Project to provide estimates of children’s exposure to parental absence due to migration across contexts. Still other data collection efforts have taken a more in-depth comparative focus on migration’s role in children’s lives or have combined qualitative and quantitative approaches (e.g., Garip, 2019 ). The Transnational Migration and Changing Care Arrangements for Left-Behind Children in Southeast Asia (CHAMPSEA) project, a comparative mixed-methods study focused on migrants and their children in Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam, has added to our understanding of the health and well-being of children and their caregivers when family members migrate for work in previously understudied settings ( Jordan & Graham, 2012 ). In-depth interviews and longitudinal survey data on children and adolescents are hallmarks of the Young Lives study of children in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam ( Nguyen, 2016 ).

We need more comparative research that can follow families over time as members move; this would provide a richer description of how families are selected into immigration and how immigration changes families across contexts. We also see a need for more theoretical development that can incorporate influences of the macro economic, social, and political systems along with family-level dynamics. This may give us the additional insights to understand why some families in some contexts appear to benefit from migration while returns are far less favorable for others.

Variation Across Types of Migration

It is also important to consider possible changes in the motivations for migration. Most of the research reviewed here focused on labor migration, but research is increasingly looking at migration related to climate change, natural disasters, and other types of forced migration. Also, there may be differences in the contrast between internal and international migration. On one hand, in contexts such as China, internal migrants face structural constraints to their moves that may mirror the barriers facing international migrants in other contexts. On the other hand, in other places, internal migrants face few restrictions, but international migration poses significant structural barriers to family reunification after migration—either by limiting parental return visits to the origin household or by limiting children’s ability to join parents in the destination. Thus, the impacts of parental migration are likely to be contingent on the underlying legal and economic constraints that prolong the separation of parents and children ( Dreby, 2015a ; Eremenko & González-Ferrer, 2018 ; Meng & Yamauchi, 2017 ).

Legal Status, Immigration Policy, and Enforcement

We must also be cognizant of the significant share of immigrant families facing greater hardship due to unauthorized or liminal legal status ( Menjívar, Abrego, & Schmalzbauer, 2016 ). This is becoming an ever-increasing concern as anti-immigrant sentiments echo throughout many receiving settings today, and increased border and interior enforcement, child separation practices, and mass deportations threaten to break apart and undermine families. We highlighted some research here on these topics, but most of it focused on Hispanic parents and young children. More work on the effects of legal status and immigration policies on other groups (non-Hispanics, young adults, older adults) is crucial, especially as the unauthorized immigrant population ages and becomes more diverse ( Passel & Cohn, 2016 ). Research that assesses the mid-range and longer range impacts of harsh or punitive immigration enforcement policies on children (e.g., family separation) is also of utmost importance (an entire issue of the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies was recently devoted to this topic). Clearly this is an area in which family scholars can be engaged in public-facing, policy-relevant work.

Just as research on transnational ties places high demands on data and careful comparative work, research on legal status and enforcement is challenged by data limitations. Research on immigrant legal status can pose challenges to qualitative researchers as they seek to gain the trust of their subjects. Quantitative researchers also face difficulties because immigration status is rarely asked in surveys, but new methods are beginning to be developed for imputing legal status from survey data ( Capps, Bachmeier, & Van Hook, 2018 ; Hall, Greenman, & Farkas, 2010 ). In addition, researchers have made significant advances in measuring contextual factors such as the intensity of immigration enforcement or anti-immigrant sentiment through the use of administrative (e.g., Amuedo-Dorantes et al., 2015 ) and webscraped data ( Flores, 2017 ).

It will also be important to consider how possible changes in immigration laws influence immigrant families who are legally admitted to the country. Currently, U.S. immigration policy gives preference to family members of U.S. citizens and lawful permanent residents. A majority (68%) of the new green-card holders were either immediate relatives of U.S. citizens or entered under the family preference program ( Zong, Batalova, & Hallock, 2018 ; U.S. Department of Homeland Security, 2018 , table 16). However, U.S. immigration advocates and critics have debated the merits of the United States adopting an immigration admission policy that would give greater emphasis to selecting on higher level skills, income, or educational attainment, akin to Canada’s point system ( RAISE Act, 2017 ; Meiiessner & Chishti, 2013 ; Capps, Greenburg, Fix, & Zong, 2018 ). The effects of such policy changes remain unclear. In the short run, at least, such changes could foreseeably lead to more family separation and further undermine informal support systems among immigrant families.

Connections Across Generations

It is also important to consider the ways families are linked across generations, from parents to children to grandchildren. Much of the research conducted on immigrants in destination settings has focused on immigrants and their children. This work fits in the mold of a large body of research conducted in the late 1980s and 1990s that sought to understand inequality among the “new” second generation, that is, the children of the highly diverse, post-1965 immigrant waves from Mexico, Latin America, and Asia ( Portes & Rumbaut, 2001 ). Nearly a generation has passed since this research was first conducted. The grandchildren of the post-1965 immigrant waves are now coming of age, yet little research has focused on them. As noted here, some scholars have examined the ways immigrant grandmothers support their daughters as they raise young children, but more longitudinal research on the “new” third generation would be valuable for better understanding the intergenerational assimilation and mobility process in the current social, economic, and political environment ( Jiménez, Park, & Pedroza, 2018 ). Data limitations have made it difficult to follow immigrants and their descendants across multiple generations. Yet progress is now being made on this score due to innovations in data linkages (e.g., Catron, 2016 ). Such work promises to provide new insights about the assimilation process as it unfolds across generations and over time.

Causal Inference

We cannot underemphasize the importance of descriptive work for influencing policies, services, and programs, but there is also an important place for studies that seek to establish cause and effect. This is important for the development and evaluation of programs and policies, ranging from national-level immigrant admission, enforcement, and legalization policies to smaller scale parenting programs for immigrant families. Some notable examples of such work include studies that seek to estimate the effect of interior immigration enforcement on the likelihood that Hispanic children live with one or no parents (e.g., Amuedo-Dorantes & Antman, 2017 ), the effects of Mexican immigrant mothers’ pursuit of their own schooling on their engagement in their child’s school ( Crosnoe & Kalil, 2010 ), and the effects of father absence due to migration (as opposed to divorce) on father–child interaction in Mexico ( Nobles, 2011 ). Each of these studies question whether the relationships they observe are causal or are a result of selection or reverse causality, draw on theory and prior knowledge about the independent variable (i.e., how and why does immigration interior enforcement, adult education, and parental migration from Mexico vary or change?), and apply well-established methods to approximate causal effects. These are all quantitative studies, but we see ways for both quantitative and qualitative research to contribute in this area. Qualitative research is essential because it can provide a deeper understanding of processes, mechanisms, and motivations underlying the relationships seen in quantitative work.

In conclusion, we view research on immigration and immigrant families as particularly urgent in the current anti-immigrant political environment. Immigration is one of the major forces of social change, and as nations and economies of the world have grown increasingly interconnected, this work has become vital for understanding the underlying shifts and changes occurring among immigrant and nonimmigrant families alike. As we look ahead to the next decade, we anticipate that family research on immigration will only grow in significance, as both immigration and nativist hostility toward immigrants is likely to continue and unsubstantiated (and often false) narratives about immigrants shape public opinion and drive policy. We recognize the inherent difficulties of conducting research on immigrant families due to the ways immigrants and their children span international borders, cultures, and generations, and the sensitivity of the topic. Yet we are also encouraged by the advances made in the past decade as researchers have employed careful measurement, innovative multisite data collections, and longitudinal methods to better understand how immigration is shaping families in both sending and destination contexts.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge assistance provided by the Population Research Institute at Penn State University, which is supported by an infrastructure grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P2CHD041025). We also thank Kendal Lowrey for assistance with the literature review.

- Abrego L (2009). Economic well-being in Salvadoran transnational families: How gender affects remittance practices . Journal of Marriage and Family , 71 ( 4 ), 1070–1085. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00653.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Acharya R, Santhya KG, & Jejeebhoy SJ (2013). Exploring associations between mobility and sexual experiences among unmarried young people: Evidence from India . The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science , 648 ( 1 ), 120–135. 10.1177/0002716213481571 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Adsera A, & Ferrer A (2014). Factors influencing the fertility choices of child immigrants in Canada . Population Studies , 68 ( 1 ), 65–79. 10.1080/00324728.2013.802007 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aiken AR, & Trussell J (2017). Anticipated emotions about unintended pregnancy in relationship context: Are Latinas really happier? Journal of Marriage and Family , 79 ( 2 ), 356–371. 10.1111/jomf.12338 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alba R, & Foner N (2015). Strangers no more: Immigration and the challenges of integration in North America and Western Europe . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Allen B, Cisneros EM, & Tellez A (2015). The children left behind: The impact of parental deportation on mental health . Journal of Child and Family Studies , 24 ( 2 ), 386–392. 10.1007/s10826-013-9848-5 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Amuedo-Dorantes C, & Antman F (2017). Schooling and labor market effects of temporary authorization: Evidence from DACA . Journal of Population Economics , 30 ( 1 ), 339–373. 10.1007/s00148-016-0606-z [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Amuedo-Dorantes C, & Arenas-Arroyo E (2019). Immigration enforcement and Children’s living arrangements . Journal of Policy Analysis and Management , 38 ( 1 ), 11–40. 10.1002/pam.22106 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Amuedo-Dorantes C, Pozo S, & Puttitanun T (2015). Immigration enforcement, parent–child separations, and intent to Remigrate by central American deportees . Demography , 52 ( 6 ), 1825–1851. 10.1007/s13524-015-0431-0 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Antman FM (2011). The intergenerational effects of paternal migration on schooling and work: What can we learn from Children’s time allocations? Journal of Development Economics , 96 ( 2 ), 200–208. 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.11.002 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Antman FM (2012). Gender, educational attainment, and the impact of parental migration on children left behind . Journal of Population Economics , 25 ( 4 ), 1187–1214. 10.1007/s00148-012-0423-y [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Arias P (2013). International migration and familial change in communities of origin: Transformation and resistance . Annual Review of Sociology , 39 , 429–450. 10.1146/annurev-soc-122012-112720 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baker SG (1990). The cautious welcome: The legalization programs of the Immigration Reform and Control Act . The Urban Insitute. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bean FD, Berg RR, & Van Hook JV (1996). Socioeconomic and cultural incorporation and marital disruption among Mexican Americans . Social Forces , 75 ( 2 ), 593–617. 10.2307/2580415 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bean FD, Brown SK, & Bachmeier JD (2015). Parents without papers: The Progress and pitfalls of Mexican American integration . New York: Russell Sage. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bean FD, Swicegood CG, & Berg R (2000). Mexican-origin fertility: New patterns and interpretations . Social Science Quarterly , 81 ( 1 ), 404–421. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bengtson V (2018). Global aging and challenges to families . Philadelphia, PA: Routledge. [ Google Scholar ]

- Benner AD, & Kim SY (2009). Intergenerational experiences of discrimination in Chinese American families: Influences of socialization and stress . Journal of Marriage and Family , 71 ( 4 ), 862–877. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00640.x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Berger Cardoso J, Scott JL, Faulkner M, & Barros Lane L (2018). Parenting in the context of deportation risk . Journal of Marriage and Family , 80 ( 2 ), 301–316. 10.1111/jomf.12463 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Boyd M, & Grieco E (2003). Women and migration: Incorporating gender into international migration theory . Migration Information Source , 1 ( 35 ), 28. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brabeck KM, & Sibley E (2016). Immigrant parent legal status, parent–child relationships, and child social emotional wellbeing: A middle childhood perspective . Journal of Child and Family Studies , 25 ( 4 ), 1155–1167. 10.1007/s10826-015-0314-4 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bravo DY, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Zeiders KH, Updegraff KA, & Jahromi LB (2016). Incongruent teen pregnancy attitudes, coparenting conflict, and support among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers . Journal of Marriage and Family , 78 ( 2 ), 531–545. 10.1111/jomf.12271 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown SL, Stykes JB, & Manning WD (2016). Trends in Children’s family instability, 1995–2010 . Journal of Marriage and Family , 78 ( 5 ), 1173–1183. 10.1111/jomf.12311 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown SL, Van Hook J, & Glick JE (2008). Generational differences in cohabitation and marriage in the US . Population Research and Policy Review , 27 ( 5 ), 531–550. 10.1007/s11113-008-9088-3 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Caarls K, & Mazzucato V (2015). Does international migration Lead to divorce? Ghanaian couples in Ghana and abroad . Population , 70 ( 1 ), 127–151. 10.3917/popu.1501.0135 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Capps R, Bachmeier JD, & Van Hook J (2018). Estimating the characteristics of unauthorized immigrants using U.S. Census data: Combined sample multiple imputation . The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science , 677 ( 1 ), 165–179. 10.1177/0002716218767383 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Capps R, Fix M, & Zong J (2016). A profile of U.S. children of unauthorized immigrant parents . Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. [ Google Scholar ]

- Capps R, Greenburg M, Fix M, & Zong J (2018). Gauging the impact of DHS’ proposed public-charge rule on U.S. immigration . Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. [ Google Scholar ]

- Carrillo H (2018). Pathways of desire: The sexual migration of Mexican gay men . Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Catron P (2016). Made in America? Immigrant occupational mobility in the first half of the twentieth century . American Journal of Sociology , 122 ( 2 ), 325–378. 10.1086/688043 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chae S, Hayford SR, & Agadjanian V (2016). Father’s migration and leaving the parental home in rural Mozambique . Journal of Marriage and Family , 78 ( 4 ), 1047–1062. 10.1111/jomf.12295 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen F, Liu G, & Mair CA (2011). Intergenerational ties in context: Grandparents caring for grandchildren in China . Social Forces , 90 ( 2 ), 571–594. 10.1093/sf/sor012 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen J, & Takeuchi DT (2011). Intermarriage, ethnic identity, and perceived social standing among Asian women in the United States . Journal of Marriage and Family , 73 ( 4 ), 876–888. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00853.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Choi KH, & Tienda M (2017). Marriage-market constraints and mate-selection behavior: Racial, ethnic, and gender differences in intermarriage . Journal of Marriage and Family , 79 ( 2 ), 301–317. 10.1111/jomf.12346 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Choi SY, Cheung YW, & Cheung AK (2012). Social isolation and spousal violence: Comparing female marriage migrants with local women . Journal of Marriage and Family , 74 ( 3 ), 444–461. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00963.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Creighton MJ, Park H, & Teruel GM (2009). The role of migration and single motherhood in upper secondary education in Mexico . Journal of Marriage and Family , 71 ( 5 ), 1325–1339. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00671.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crosnoe R, Ansari A, Purtell KM, & Wu N (2016). Latin American immigration, maternal education, and approaches to managing Children’s schooling in the United States . Journal of Marriage and Family , 78 ( 1 ), 60–74. 10.1111/jomf.12250 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Crosnoe R, & Kalil A (2010). Educational progress and parenting among Mexican immigrant mothers of young children . Journal of Marriage and Family , 72 ( 4 ), 976–990. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00743.x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Czaika M, & De Haas H (2014). The globalization of migration: Has the world become more migratory? International Migration Review , 48 ( 2 ), 283–323. 10.1111/imre.12095 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Derlan CL, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Updegraff KA, & Jahromi LB (2018). Mother–grandmother and mother–father Coparenting across time among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers and their families . Journal of Marriage and Family , 80 ( 2 ), 349–366. 10.1111/jomf.12462 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- DeWaard J, Nobles J, & Donato KM (2018). Migration and parental absence: A comparative assessment of transnational families in Latin America . Population, Space and Place , 24 ( 7 ), e2166. 10.1002/psp.2166 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dreby J (2010). Divided by borders: Mexican migrants and their children . Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dreby J (2012). The burden of deportation on children in Mexican immigrant families . Journal of Marriage and Family , 74 ( 4 ), 829–845. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00989.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dreby J (2015a). Everyday illegal: When policies undermine immigrant families . Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dreby J (2015b). US immigration policy and family separation: The consequences for Children’s well-being . Social Science & Medicine , 132 , 245–251. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.041 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dreby J, & Schmalzbauer L (2013). The relational contexts of migration: Mexican women in new destination sites . Sociological Forum , 28 ( 1 ), 1–26. 10.1111/socf.12000 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dreby J, & Stutz L (2012). Making something of the sacrifice: Gender, migration and Mexican Children’s educational aspirations . Global Networks , 12 ( 1 ), 71–90. 10.1111/j.1471-0374.2011.00337.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Engzell P (2019). Aspiration squeeze: The struggle of children to positively selected immigrants . Sociology of Education , 92 , 83–103. 10.1177/0038040718822573 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Enriquez LE (2015). Multigenerational punishment: Shared experiences of undocumented immigration status within mixed-status families . Journal of Marriage and Family , 77 ( 4 ), 939–953. 10.1111/jomf.12196 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Enriquez LE (2017). Gendering illegality: Undocumented young adults’ negotiation of the family formation process . American Behavioral Scientist , 61 , 1153–1171. 10.1177/0002764217732103 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Eremenko T, & González-Ferrer A (2018). Transnational families and child migration to France and Spain. The role of family type and immigration policies . Population, Space and Place , 24 ( 7 ), e2163. 10.1002/psp.2163 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Esteve A, García-Román J, & Lesthaeghe R (2012). The family context of cohabitation and single motherhood in Latin America . Population and Development Review , 38 ( 4 ), 707–727. 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2012.00533.x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Flores RD (2017). Do anti-immigrant Laws shape public sentiment? A study of Arizona’s SB 1070 using twitter data . American Journal of Sociology , 123 ( 2 ), 333–384. 10.1086/692983 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fomby P, & Estacion A (2011). Cohabitation and Children’s externalizing behavior in low-income Latino families . Journal of Marriage and Family , 73 ( 1 ), 46–66. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00788.x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Foner N, & Dreby J (2011). Relations between the generations in immigrant families . Annual Review of Sociology , 37 , 545–564. 10.1146/annurev-soc-081309-150030 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frank K, & Hou F (2015). Source-country gender roles and the division of labor within immigrant families . Journal of Marriage and Family , 77 , 557–574. 10.1111/jomf.12171 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frank R, & Heuveline P (2005). A crossover in Mexican and Mexican-American fertility rates: Evidence and explanations for an emerging paradox . Demographic Research , 12 ( 4 ), 77. 10.4054/DemRes.2005.12.4 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frank R, & Wildsmith E (2005). The grass widows of Mexico: Migration and union dissolution in a binational context . Social Forces , 83 ( 3 ), 919–947. 10.1353/sof.2005.0031 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Garip F (2019). On the move: Changing mechanisms of Mexico-US migration (Vol. 2 ). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gaydosh L (2017). Beyond Orphanhood: Parental nonresidence and child well-being in Tanzania . Journal of Marriage and Family , 79 , 1369–1387. 10.1111/jomf.12422 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Glick JE, Bates L, & Yabiku ST (2009). Mother’s age at arrival in the United States and early cognitive development . Early Childhood Research Quarterly , 24 ( 4 ), 367–380. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.01.001 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Glick JE, Hanish LD, Yabiku ST, & Bradley RH (2012). Migration timing and parenting practices: Contributions to social development in preschoolers with foreign-born and native-born mothers . Child Development , 83 ( 5 ), 1527–1542. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01789.x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goldberg RE (2018). Understanding generational differences in early fertility: Proximate and social determinants . Journal of Marriage and Family , 80 ( 5 ), 1225–1243. 10.1111/jomf.12506 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gonzales RG (2011). Learning to be illegal: Undocumented youth and shifting legal contexts in the transition to adulthood . American Sociological Review , 76 ( 4 ), 602–619. 10.1177/0003122411411901 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gordon MM (1964). Assimilation in American life: The role of race, religion, and national origins . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Graham E, & Jordan LP (2011). Migrant parents and the psychological well-being of left-behind children in Southeast Asia . Journal of Marriage and Family , 73 ( 4 ), 763–787. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00844.x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Greenman E, & Hall M (2013). Legal status and educational transitions for Mexican and central American immigrant youth . Social Forces , 91 ( 4 ), 1475–1498. 10.1093/sf/sot040 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gruijters RJ (2017). Intergenerational contact in Chinese families: Structural and cultural explanations . Journal of Marriage and Family , 79 ( 3 ), 758–768. 10.1111/jomf.12390 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hall M, Greenman E, & Farkas G (2010). Legal status and wage disparities for Mexican immigrants . Social Forces , 89 ( 2 ), 491–513. 10.1353/sof.2010.0082 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haller W, Portes A, & Lynch SM (2011). Dreams fulfilled, dreams shattered: Determinants of segmented assimilation in the second generation . Social Forces , 89 ( 3 ), 733–762. 10.1353/sof.2011.0003 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hamilton ER, & Hale JM (2016). Changes in the transnational family structures of Mexican farm workers in the era of border militarization . Demography , 53 ( 5 ), 1429–1451. 10.1007/s13524-016-0505-7 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hartnett C (2012). Are hispanic women happier about unintended births . Population Research and Policy Review , 31 , 683–701. 10.1007/s11113-012-9252-7 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hartnett CS, & Parrado EA (2012). Hispanic familism reconsidered: Ethnic differences in the perceived value of children and fertility intentions . The Sociological Quarterly , 53 ( 4 ), 636–653. 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2012.01252.x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hershberg RM (2018). Consejos as a family process in transnational and mixed-status Mayan families . Journal of Marriage and Family , 80 ( 2 ), 334–348. 10.1111/jomf.12452 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hertrich V, & Lesclingand M (2012). Adolescent migration and the 1990s nuptiality transition in Mali . Population Studies , 66 ( 2 ), 147–166. 10.1080/00324728.2012.669489 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hoang LA, & Yeoh BS (2011). Breadwinning wives and “left-behind” husbands: Men and masculinities in the Vietnamese transnational family . Gender & Society , 25 ( 6 ), 717–739. 10.1177/0891243211430636 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hondagneu-Sotelo P (Ed.). (2003). Gender and US immigration: Contemporary trends . Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hou Y, Neff LA, & Kim SY (2018). Language acculturation, acculturation-related stress, and marital quality in Chinese American couples . Journal of Marriage and Family , 80 ( 2 ), 555–568. 10.1111/jomf.12447 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hsin A, & Ortega F (2018). The effects of deferred action for childhood arrivals on the educational outcomes of undocumented students . Demography , 55 ( 4 ), 1487–1506. 10.1007/s13524-018-0691-6 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- International Organization for Migration. (2017). World migration report 2018 . New York: United Nations. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jensen B, Giorguli Saucedo S, & Hernández Padilla E (2016). International migration and the academic performance of Mexican adolescents . International Migration Review , 2016 , 1–38. 10.1111/imre.12307 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jeong YJ, Hamplová D, & Le Bourdais C (2014). Diversity of young adults’ living arrangements: The role of ethnicity and immigration . Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies , 40 ( 7 ), 1116–1135. 10.1080/1369183X.2013.831523 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jiménez TR, Park J, & Pedroza J (2018). The new third generation: Post-1965 immigration and the next chapter in the long story of assimilation . International Migration Review , 52 ( 4 ), 1040–1079. 10.1111/imre.12343 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jordan LP, Dito B, Nobles J, & Graham E (2018). Engaged parenting, gender, and Children’s time use in transnational families: An assessment spanning three global regions . Population, Space and Place , 24 ( 7 ), e2159. 10.1002/psp.2159 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jordan LP, & Graham E (2012). Resilience and well-being among children of migrant parents in south-east Asia . Child Development , 83 ( 5 ), 1672–1688. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01810.x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Juarez F, LeGrand T, Lloyd C, Singh S, & Hertrich V (2013). Youth migration and transitions to adulthood in developing countries . The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science , 648 , 6–15. 10.1177/0002716213485052 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kanaiaupuni SM (2000). Reframing the migration question: An analysis of men, women, and gender in Mexico . Social Forces , 78 ( 4 ), 1311–1347. 10.2307/3006176 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kasinitz P, Mollenkopf JH, Waters MC,& Hold-away J (2009). Inheriting the City: The children of immigrants come of age . New York: Russell Sage. [ Google Scholar ]

- Killoren SE, Updegraff KA, Christopher FS, & Umaña-Taylor AJ (2011). Mothers, fathers, peers, and Mexican-origin adolescents’ sexual intentions . Journal of Marriage and Family , 73 ( 1 ), 209–220. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00799.x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Knight GP, Berkel C, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Gonzales NA, Ettekal I, Jaconis M, & Boyd BM (2011). The familial socialization of culturally related values in Mexican American families . Journal of Marriage and Family , 73 ( 5 ), 913–925. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00856.x [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]