Popular Insights:

Best Project Management Software

Mind Mapping Software

Conflict Management, Problem Solving and Decision Making

Share this Article:

Our content and product recommendations are editorially independent. We may make money when you click links to our partners. Learn more in our Editorial & Advertising Policy .

Featured Partners

{{ POSITION }}. {{ TITLE }}

Conflict management, problem solving and decision making are topics that are generally considered to be distinct, but are actually interconnected such that they are used together to come up with the most feasible solution.

To come to the best possible outcome of a problem on the basis of sufficient information, certain problem solving steps need to be used. Some of these are as follows:

- Scrutinizing the problem

- Outlining the issue; solutions depends on the way it is outlined

- Detecting the main reasons which allowed the problem to occur

- Identifying the series of techniques to apply, and their outcomes

- Produce alternative options through processes such as brainstorming, discussions between groups and other discrete processes

- Choosing the simplest method that resolves the root cause

- Implementing the chosen method

- Monitoring and reviewing the execution

The flaw with this process is that it assumes there exists an ideal outcome, the information is available to reach this outcome, and the people taking part in the process are acting rationally. Unfortunately, this situation is extremely unusual.

Read More: What is Project Management? Definition, Types & Examples

Another flaw is the emotions of people involved in decision making. The core focus of conflict management is to reduce the effect of people’s emotions and make them think rationally. The typical solution choices are:

- Forcing/Directing – A method whereby a superior with autonomous power has a right to force the decision

- Smoothing/Accommodating – Negotiating the matter and trying to settle down the dispute

- Compromising/Reconciling – A give and take approach where each side surrenders something in order to come to a solution. The extent of dispute limits the generation of options.

- Problem-solving/Collaborating – Refers to collective decision making to come up with a solution that is conventional

- Avoiding/Withdrawing/Accepting – A method which may not settle the dispute but allows time to calm the emotions

Any of these approaches can be used for conflict management depending on the nature of conflict, although there primary focus is to control the level of the dispute. But, in due course, the underlying problems of the conflict need to be solved in its entirety .

To make the right decision, availability of sufficient and precise data needs to be present. Some decisions are not as simple, and data about them is not easily available.

The problems you can face range from simple to wicked problems.

- Wicked Problems are the kind of problems that continuously alter and demand the participant’s complexity and emotions. An iterative approach is best for these kinds of problems, as decision to every step simplifies the problem.

- In Dilemmas, you have to choose the solution which is the least worse as there is no right answer to these problems, but choosing a solution is always better than not making a decision.

- Conundrums are complicated questions that have speculative or hypothetical answers.

- Puzzles and mysteries need superlative judgment in certain circumstances. Lack of time to contract these decisions to simple problems is a constraint in this approach, although you can apply processes to a point.

- Problems require hard work to be solved. Carefully and properly designed execution of problem solving processes can show the best outcomes.

In order to come to the best possible conclusion, an understanding and balance of the following points is essential:

- Characteristics of problem at hand

- Emotion and conflict of stakeholders

- Features of different type of decisions

- Pick up the single best decision using your best judgement in given circumstances

The core of all the above is choosing & implementing the best decision, followed by a continuous review of the decision, making changes as quickly as possible, and providing a feedback.

Sign up for our emails and be the first to see helpful how-tos, insider tips & tricks, and a collection of templates & tools. Subscribe Now

{{ TITLE }}

You should also read.

What Is a RACI Matrix?

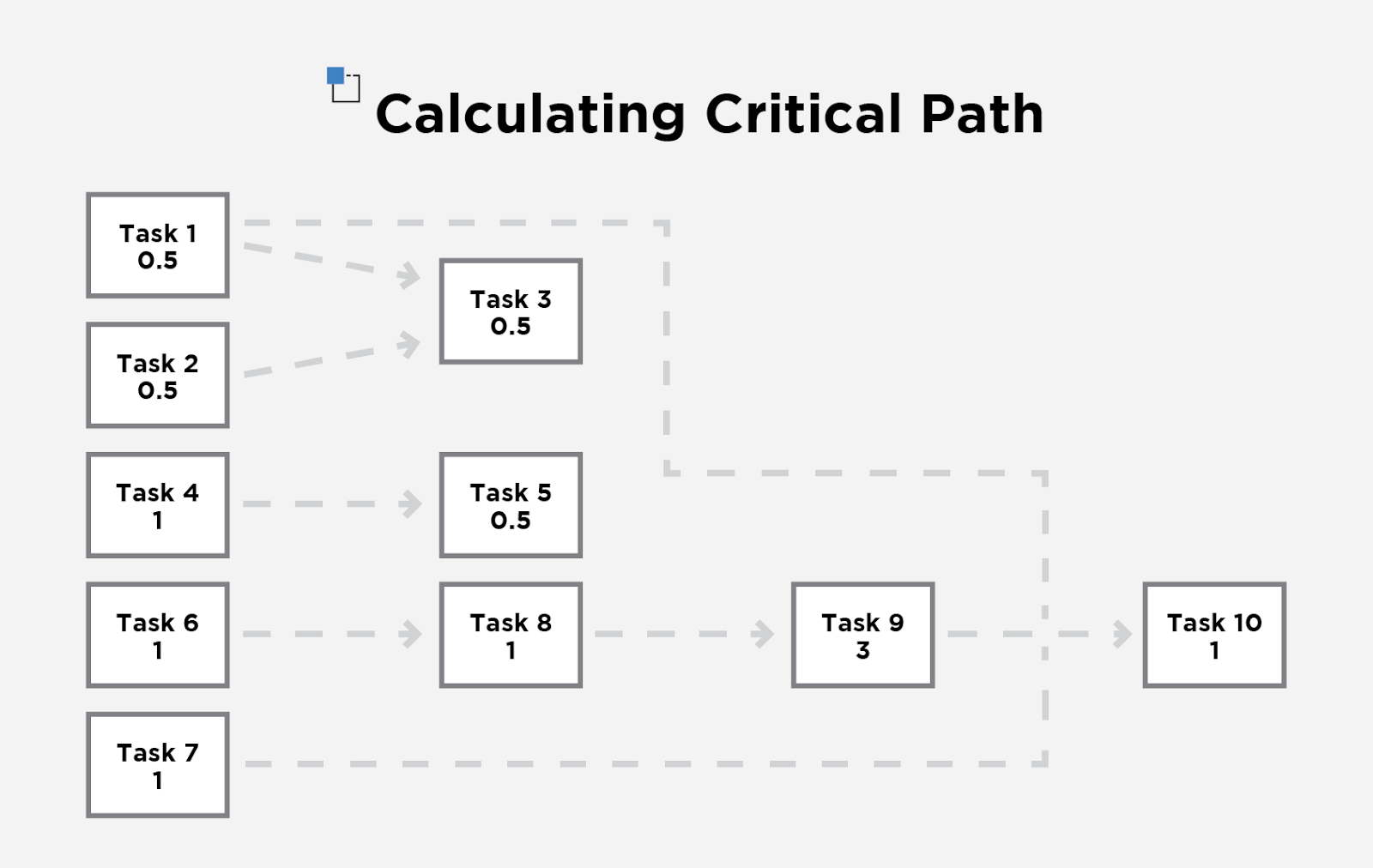

What Is a Critical Path Method in Project Management?

How to Take Meeting Minutes Effectively (+ Example and Templates)

Join our newsletter.

Subscribe to Project Management Insider for best practices, reviews and resources.

By clicking the button you agree of the privacy policy

Get the Newsletter

You might also like.

How to Manage Time Constraints: Top 7 Expert Tips

6 RACI Matrix Alternatives to Help Define Project Roles

10 Benefits of Project Management Software for Business

Effective Strategies for Conflict Management in Problem Solving Cycles

- Post author By bicycle-u

- Post date 08.12.2023

Conflict is an inevitable part of human interaction and can arise in various situations, including in the workplace, within teams, or even in personal relationships. Managing conflict effectively is crucial for maintaining positive relationships and achieving successful outcomes. This article will explore some proven conflict management strategies that can be applied in problem-solving cycles.

Firstly, it is important to acknowledge that conflict is not always a negative occurrence. In fact, conflicts can often lead to positive outcomes, such as the generation of new ideas or the identification of underlying issues. However, when conflict arises, it is crucial to address it promptly and constructively.

One of the most effective conflict management strategies is open communication. Encouraging all parties involved to express their thoughts and feelings in a respectful manner can help to uncover the root causes of the conflict and facilitate problem-solving. Active listening is also a key component of open communication, as it allows each party to fully understand the perspectives and concerns of others.

Another essential strategy is to focus on finding win-win solutions. This involves searching for mutually beneficial outcomes that address the needs and interests of all parties involved. By emphasizing collaboration and cooperation, rather than competition, conflict can be transformed into an opportunity for growth and development.

In conclusion, conflict management is a critical skill for successful problem-solving cycles. By promoting open communication, active listening, and a focus on win-win solutions, conflicts can be effectively managed and transformed into positive outcomes. These strategies can be applied in various contexts, whether in the workplace or personal relationships, to foster healthy and productive interactions.

Understanding Conflict Management

In problem-solving cycles, conflict is an inevitable part of the process. When individuals or teams work together to find solutions, differences in opinions, ideas, and approaches can lead to conflict. Conflict arises when there is a disagreement or tension between individuals or groups regarding goals, priorities, resources, or methods.

Effective conflict management involves understanding the nature of conflict and employing strategies to address and resolve it. It is important to approach conflict in a constructive and positive manner, as conflicts can provide opportunities for growth, innovation, and better outcomes.

Conflict can be categorized into two types: constructive and destructive. Constructive conflict refers to disagreements that lead to positive outcomes, such as increased creativity, collaboration, and problem-solving. Destructive conflict, on the other hand, hinders progress and stifles productivity.

To effectively manage conflict, it is essential to analyze the underlying causes and dynamics. Common causes of conflict include differences in communication styles, values, goals, and interests. Understanding these underlying factors can help identify potential areas of conflict and develop appropriate strategies for resolution.

Conflict management strategies can include active listening, open communication, mediation, negotiation, and compromise. Active listening involves truly hearing and empathizing with the perspectives and concerns of others. Open communication promotes transparency and encourages dialogue to address misunderstandings and find common ground.

Mediation involves a neutral third party facilitating communication and guiding the resolution process. Negotiation focuses on finding mutually agreeable solutions by exploring alternatives and making concessions where necessary. Compromise requires finding a middle ground that satisfies the needs and interests of all parties involved.

Conflict management should also prioritize building and maintaining positive relationships. It is important to approach conflicts with respect, empathy, and a willingness to understand and accommodate different perspectives. By fostering a culture of open communication and collaboration, conflicts can be transformed into opportunities for growth, learning, and stronger problem-solving.

In conclusion, conflict is a natural and expected part of problem-solving cycles. Understanding the nature of conflict and employing effective conflict management strategies is crucial for successful problem resolution. By approaching conflicts with empathy, active listening, open communication, and a focus on building positive relationships, conflicts can be transformed into opportunities for positive change and growth.

Benefits of Effective Conflict Resolution

In the cycles of problem solving and conflict management, effective conflict resolution has numerous benefits. When conflict is handled effectively, it can lead to positive outcomes and improved relationships among team members.

One of the main benefits of effective conflict resolution is that it reduces tension and stress within the team. Conflict can create a hostile and uncomfortable environment, but by resolving it in a constructive manner, team members can feel more at ease and motivated to work collaboratively.

Effective conflict resolution also promotes open communication and transparency. When conflicts are addressed and resolved, team members are encouraged to express their opinions, concerns, and ideas freely. This enhances overall communication within the team and fosters an environment of trust and respect.

Furthermore, effective conflict resolution can lead to innovative problem-solving. When conflicts arise, they often bring to light different perspectives and opinions. By actively engaging in conflict resolution, team members can learn to value different viewpoints and find creative solutions that address everyone’s needs.

Another benefit of effective conflict resolution is the development of stronger relationships. Conflict can strain relationships and create barriers between team members. However, by resolving conflict in a respectful and productive way, team members can build trust, empathy, and understanding, leading to stronger and more harmonious working relationships.

Problem Solving Cycles in Conflict Management

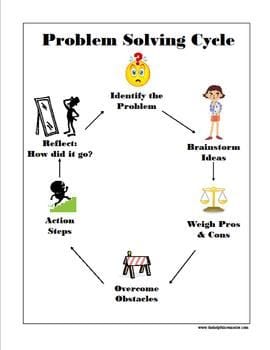

In conflict management, problem solving cycles play a crucial role in resolving issues and achieving productive outcomes. These cycles involve a series of steps that guide individuals and teams in addressing conflicts and finding innovative solutions.

The problem-solving cycle begins with the identification and definition of the problem or conflict at hand. This crucial step helps to clarify the issues, understand the underlying causes, and recognize the stakeholders involved. Once the problem is clearly defined, the next phase involves gathering information and conducting a thorough analysis of the situation. This includes identifying the interests, needs, and perspectives of all parties involved in the conflict.

After conducting a comprehensive analysis, the problem-solving cycle moves on to the generation of potential solutions. This step encourages brainstorming and creative thinking to develop various options that could address the conflict effectively. In this phase, it is important to foster open dialogue and encourage diverse perspectives to generate a wide range of possible solutions.

Once a range of potential solutions has been identified, the next step in the problem-solving cycle is evaluating and selecting the most appropriate option. This entails considering the feasibility, effectiveness, and potential consequences of each solution. It is crucial to involve all stakeholders in the decision-making process to ensure buy-in and ownership of the chosen solution.

Once a decision has been made, the problem-solving cycle moves on to implementation. This phase involves developing a clear action plan, assigning roles and responsibilities, and setting specific timelines. It is important to communicate the plan effectively to all stakeholders and provide the necessary support and resources to ensure successful execution.

Finally, the problem-solving cycle concludes with the evaluation and review of the implemented solution. This step helps to assess the effectiveness of the chosen approach and identify any areas for improvement. By reflecting on the outcomes and lessons learned, individuals and teams can refine their conflict management strategies and enhance their problem-solving skills for future challenges.

Importance of Communication in Conflict Resolution

Effective communication plays a crucial role in the resolution of conflicts. When conflicts arise, it is important for all parties involved to openly and honestly express their thoughts, feelings, and concerns. By actively listening and understanding each other’s perspectives, individuals can work towards finding common ground and resolving the conflict.

In problem solving cycles, communication helps in identifying and addressing the root causes of conflicts. Through open dialogue, individuals can explore the underlying issues that contribute to the conflict and develop strategies to address them. This process allows for a more comprehensive and long-lasting resolution, rather than just treating the symptoms of the conflict.

Communication also helps in managing conflicts by fostering empathy and understanding. When individuals communicate effectively, they can put themselves in each other’s shoes and gain a deeper appreciation for the other person’s point of view. This empathy can lead to a more collaborative approach to conflict resolution, where all parties are actively involved in finding mutually beneficial solutions.

Furthermore, communication helps in minimizing misunderstandings and misinterpretations that often escalate conflicts. Through clear and concise communication, individuals can clarify any misconceptions, address any false assumptions, and ensure that everyone is on the same page. This reduces the likelihood of conflicts escalating and allows for a more efficient and effective resolution process.

In conclusion, effective communication is of utmost importance in conflict resolution. By promoting open dialogue, addressing underlying issues, fostering empathy, and minimizing misunderstandings, communication plays a vital role in finding mutually beneficial solutions and resolving conflicts in problem solving cycles.

Active Listening Techniques for Conflict Resolution

In the management of problem solving cycles, conflicts are bound to arise. Conflict is a natural part of any human relationship and must be effectively managed in order to ensure productive outcomes.

The Importance of Active Listening

One key technique in conflict resolution is active listening. Active listening involves fully engaging with the speaker and demonstrating understanding and empathy. By actively listening, individuals can better understand the concerns and perspectives of others, which can lead to more effective problem solving.

Active listening techniques can be employed in various conflict resolution scenarios, including team meetings, client interactions, and interpersonal relationships. The goal is to create an environment of open communication and mutual respect, allowing parties to express their thoughts and feelings freely.

Techniques for Active Listening

Here are some techniques that can enhance active listening during conflict resolution:

- Maintain eye contact: By maintaining eye contact, you show the speaker that you are fully engaged and attentive.

- Ask clarifying questions: Clarifying questions help you gain a deeper understanding of the speaker’s perspective and can prevent misunderstandings.

- Reflect and paraphrase: Reflecting and paraphrasing the speaker’s words demonstrates that you are actively listening and seeking to understand their viewpoint.

- Show empathy: Demonstrating empathy towards the speaker’s feelings and experiences can help create a sense of trust and openness.

- Avoid interrupting: Interrupting the speaker can be perceived as disrespectful and may hinder effective communication. Allow the speaker to finish before responding.

- Summarize key points: Summarizing key points at the end of the conversation can help ensure that both parties are on the same page and have a clear understanding of the issues.

By incorporating these active listening techniques into conflict resolution processes, individuals can foster better understanding, promote collaborative problem solving, and ultimately achieve successful outcomes in any problem solving cycle.

Effective Negotiation Skills for Conflict Resolution

Conflict resolution is an essential part of effective management. It involves finding mutually acceptable solutions to conflicts and reaching agreements that satisfy all parties involved. Effective negotiation skills play a crucial role in resolving conflicts and promoting a healthy work environment.

Understanding the Problem

The first step in conflict resolution is to understand the problem at hand. It is important to listen to all parties involved and gather relevant information. By understanding the root causes of the conflict, a manager can gain insights into the underlying issues and find a solution that addresses the actual problem.

Setting Clear Goals

Once the problem is understood, it is important to set clear goals for the negotiation process. This involves identifying the desired outcomes and defining the boundaries within which the negotiation will take place. Clear goals help guide the negotiation and ensure that both parties are working towards a mutually beneficial solution.

During the negotiation process, effective communication is key. It is important to listen actively, ask clarifying questions, and express thoughts and concerns clearly. Active listening helps in understanding the other party’s perspective and finding common ground. It is also important to remain calm and composed during the negotiation process, as emotions can hinder effective communication and problem-solving.

- Be open to compromise

- Focus on interests, not positions

- Explore alternatives

- Find win-win solutions

- Use objective criteria for decision-making

By following these negotiation skills, conflicts can be resolved in a constructive manner. Effective negotiation skills allow managers to build strong relationships, promote collaboration, and foster a positive work environment. Through open communication and a focus on finding mutually beneficial solutions, conflicts can be transformed into opportunities for growth and improvement.

Mediation as a Conflict Resolution Strategy

Conflict is an inevitable part of problem-solving cycles in any organization. However, effective conflict management is crucial to ensure smooth problem-solving processes and maintain a positive work environment.

One strategy that has proven to be highly effective in resolving conflicts is mediation. Mediation involves the intervention of a neutral third party, known as a mediator, who helps facilitate communication and negotiation between conflicting parties.

Benefits of Mediation

Mediation offers several benefits as a conflict resolution strategy. Firstly, it allows all parties to express their concerns and interests openly and honestly. The mediator assists in creating a safe and respectful environment where everyone feels comfortable sharing their perspective.

Secondly, mediation promotes collaboration and cooperation among the conflicting parties. The mediator acts as a facilitator, guiding the conversation and ensuring that each party has an equal opportunity to be heard. This collaborative approach often leads to creative and mutually satisfactory solutions.

Furthermore, mediation helps build better relationships between conflicting parties. By engaging in open dialogue and working towards a common goal, individuals involved in the conflict can develop a deeper understanding and appreciate each other’s viewpoints.

Effective Mediation Process

For mediation to be effective, there are several key steps and techniques that should be followed. Firstly, the mediator must establish ground rules and create a safe space for dialogue. This includes ensuring confidentiality and impartiality.

The mediator then identifies the underlying causes of the conflict and helps the parties focus on problem-solving rather than blame. By clarifying interests and needs, the mediator can guide the conversation towards finding mutually beneficial solutions.

During the mediation process, active listening and effective communication are crucial. The mediator encourages each party to listen attentively to the other’s perspective and promotes constructive dialogue. The use of open-ended questions and paraphrasing helps facilitate understanding and clarity.

Finally, the mediator assists the parties in developing a written agreement that outlines the agreed-upon solutions and action steps. This agreement serves as a reference point for future conflict resolution if needed.

Overall, mediation is a valuable conflict resolution strategy in problem-solving cycles. When implemented effectively, it can lead to the resolution of conflicts in a respectful and collaborative manner, fostering better relationships and contributing to the overall success of the organization.

Collaborative Problem Solving in Conflict Management

Collaborative problem solving plays a crucial role in effective conflict management. In the context of problem solving cycles, it is essential to adopt a collaborative approach that encourages open communication, active listening, and cooperation among the parties involved.

Building a Collaborative Environment

Creating a collaborative environment is the foundation for successful conflict management. This involves establishing a safe space where all parties feel comfortable expressing their concerns, ideas, and perspectives. By encouraging open dialogue, individuals can work together to identify the root causes of the conflict and collectively generate potential solutions.

Active Listening and Empathy

Active listening is a critical skill in collaborative problem solving. It enables individuals to truly understand each other’s viewpoints and experiences. By actively listening, each party can demonstrate empathy towards one another, facilitating a deeper understanding of the underlying issues and fostering a spirit of cooperation.

Empathy involves putting oneself in another person’s shoes, acknowledging their emotions, and seeking understanding. By adopting an empathetic mindset, individuals can build trust and rapport, which are essential for effective conflict resolution.

Collaborative problem solving is an iterative process that involves ongoing communication, brainstorming, and evaluation of solutions. It requires a willingness to compromise and find mutually beneficial outcomes. By working together, individuals can reach resolutions that address the underlying problems and promote sustainable conflict management.

Emotional Intelligence in Conflict Resolution

In the cycles of problem solving, conflict is inevitable. However, the way we handle conflict can greatly impact the outcome of the problem solving process. One powerful tool for effective conflict resolution is emotional intelligence.

Emotional intelligence refers to the ability to recognize, understand, and manage our own emotions, as well as the emotions of others. In the context of conflict resolution, emotional intelligence helps us to navigate through difficult emotions and communicate effectively.

When faced with a conflict, individuals with high emotional intelligence are able to approach the situation with empathy and understanding. They are able to acknowledge their own feelings and those of others, which allows for a more constructive and collaborative dialogue.

Additionally, emotional intelligence enables individuals to regulate their emotions during conflict. Rather than reacting impulsively or allowing emotions to escalate, emotionally intelligent individuals are able to stay calm and composed. This helps to create a safe and positive environment for problem solving.

Another important aspect of emotional intelligence in conflict resolution is the ability to read non-verbal cues and understand underlying emotions. This allows individuals to better grasp the needs and concerns of others, leading to more effective problem solving strategies.

In summary, emotional intelligence plays a crucial role in conflict resolution within problem solving cycles. By understanding and managing our own emotions, as well as empathizing with others, we can create a supportive and collaborative environment that promotes effective problem solving.

Building Trust for Successful Conflict Management

Trust is an essential factor in effective conflict management and problem-solving cycles. When individuals trust each other, they are more likely to communicate openly, listen actively, and collaborate towards finding solutions to conflicts.

Trust plays a crucial role in conflict resolution as it creates an environment of psychological safety, where individuals feel comfortable expressing their perspectives and concerns. This open communication leads to a better understanding of the underlying causes of conflicts and facilitates the identification of suitable resolutions.

Building trust requires time and effort from all parties involved. It involves displaying transparency, honesty, and integrity in actions and words. Trust is nurtured through active listening, empathy, and showing respect for different viewpoints.

A key component of building trust is establishing clear expectations and boundaries. When individuals understand the expectations, roles, and responsibilities of each party involved, they feel more secure and confident in the conflict management process.

Another essential aspect of building trust is acknowledging and addressing past conflicts or betrayals. By openly discussing these issues and finding resolutions, individuals can heal and build stronger relationships based on trust and mutual understanding.

Trust can be built through consistent follow-through on commitments and promises made during conflict management discussions. When individuals witness that others keep their word and act upon their commitments, trust is strengthened.

In conclusion, building trust is a fundamental element in successful conflict management and problem-solving cycles. It creates an atmosphere of cooperation, open communication, and understanding. By actively working to build trust, individuals can navigate conflicts more effectively and reach resolutions that benefit all parties involved.

Empathy and Understanding in Conflict Resolution

In the management of problem solving cycles, conflicts are bound to arise. These conflicts may stem from various sources, such as differing opinions, scarce resources, or conflicting goals. However, effective conflict resolution requires more than just finding a solution; it calls for empathy and understanding.

Empathy is the ability to put oneself in someone else’s shoes and understand their perspective. In the context of conflict resolution, empathy allows individuals to truly listen to one another without judgment or bias. By actively practicing empathy, parties involved in a conflict can gain a deeper understanding of the underlying issues and emotions driving the disagreement.

Understanding, on the other hand, involves grasping the complexities and nuances of the conflict. It requires individuals to go beyond surface-level understanding and dig deeper into the root causes of the disagreement. Through understanding, people can identify the underlying values, needs, and fears that are driving the conflict and work towards addressing them in a constructive manner.

When empathy and understanding are present in conflict resolution, a transformative process can occur. Instead of approaching the conflict with the mindset of “winning” or “losing,” parties involved can focus on finding a mutually beneficial solution that addresses the underlying needs of all parties. Empathy and understanding create an environment of trust and collaboration, fostering open communication and creative problem-solving.

It is important to note that empathy and understanding do not mean agreement or condoning harmful behavior. They simply provide a foundation for productive dialogue and problem-solving. Through empathy and understanding, conflicts can be transformed from destructive cycles into opportunities for growth and learning.

Conflict Resolution Strategies in the Workplace

In any work environment, conflicts are bound to arise. These conflicts can stem from a variety of sources, such as differences in opinions, work styles, or values. It is essential for effective problem management to have strategies in place to address and resolve conflicts in the workplace.

1. Communication and Active Listening

One of the key strategies for resolving conflicts in the workplace is effective communication. Encouraging open and honest communication allows employees to express their concerns and viewpoints, providing an opportunity for understanding and finding common ground. Active listening plays a crucial role in conflict resolution, as it allows individuals involved in the conflict to feel heard and validated.

2. Mediation and Facilitation

When conflicts escalate and become challenging to resolve, mediation and facilitation can be helpful techniques. Mediation involves bringing in a neutral third party, such as a trained mediator, to assist in facilitating dialogue and finding a resolution. Facilitation, on the other hand, involves a designated facilitator guiding the conflict resolution process and ensuring that all parties have an equal opportunity to express their thoughts and concerns.

A common approach during mediation or facilitation is to encourage compromise and finding common ground. This involves identifying the underlying interests of the conflicting parties and seeking solutions that satisfy all parties to some extent. It is essential to maintain a fair and unbiased environment during these processes to ensure that conflicts are resolved in a mutually beneficial manner.

3. Conflict Management Training

An effective long-term strategy for conflict resolution in the workplace is providing conflict management training for employees. This training equips individuals with the skills and knowledge necessary to identify, address, and resolve conflicts effectively. Conflict management training can include sessions on effective communication, negotiation techniques, active listening skills, and understanding different conflict styles.

Implementing conflict resolution strategies in the workplace is essential for maintaining a healthy and productive work environment. By fostering effective communication, utilizing mediation or facilitation when necessary, and providing conflict management training, organizations can address conflicts in a constructive manner and prevent them from becoming larger problems. Ultimately, effective conflict resolution strategies contribute to the overall success and well-being of both individuals and the organization as a whole.

Conflict Resolution Techniques in Personal Relationships

In personal relationships, conflicts are bound to arise from time to time. It is essential to have effective conflict resolution techniques to ensure the maintenance of healthy relationships. By addressing conflicts promptly and effectively, individuals can prevent the escalation of issues and promote understanding and growth.

Identifying the Root Cause

When conflicts arise in personal relationships, it is crucial to identify the root cause of the problem. This involves open and honest communication, active listening, and empathy. Each party should express their thoughts and feelings without judgment, allowing for a deeper understanding of the issue at hand.

Collaborative Problem Solving

Once the root cause of the conflict is identified, both parties can engage in collaborative problem solving. This approach involves working together to find a solution that satisfies the needs and concerns of both individuals. By focusing on finding a mutually beneficial resolution, personal relationships can strengthen, and conflicts can be effectively resolved.

Implementing these conflict resolution techniques can greatly contribute to the resolution of conflicts in personal relationships. By promoting open and effective communication, empathy, and compromise, individuals can foster healthier and more long-lasting connections with their loved ones.

Conflict Resolution Training and Development

Conflict resolution training and development is an essential component of effective problem-solving and conflict management in any organization. By providing employees with the necessary skills and strategies to address and resolve conflicts, organizations can create a more positive and productive work environment.

Conflict resolution training typically includes workshops, seminars, and interactive exercises that help employees understand the nature of conflicts and their underlying causes. These training programs also provide strategies for effective communication, active listening, and negotiation, which are crucial skills for resolving conflicts.

Through conflict resolution training, employees learn how to identify and address conflicts early on, preventing them from escalating into larger problems. They also learn how to manage their emotions and maintain a respectful and collaborative attitude during conflict situations.

In addition to training sessions, development programs play a vital role in conflict resolution. These programs focus on developing the leadership and problem-solving skills of employees, empowering them to address conflicts in a constructive and proactive manner.

Development programs often include mentoring and coaching sessions, where employees receive personalized guidance and support in dealing with conflicts. These programs also provide opportunities for employees to practice their conflict resolution skills in real-life scenarios, allowing them to become more confident and proficient in managing conflicts.

By investing in conflict resolution training and development, organizations can benefit from improved teamwork, increased productivity, and enhanced employee satisfaction. Conflict resolution skills empower employees to handle disagreements and differences of opinion in a constructive and collaborative manner, ultimately leading to more effective problem-solving and decision-making processes.

Evaluating the Outcome of Conflict Resolution Strategies

After implementing conflict resolution strategies, it is essential for management to evaluate the outcome and effectiveness of these strategies. Evaluation allows organizations to assess whether the chosen strategies have successfully resolved the problem at hand and improved the overall conflict management process.

One way to evaluate the outcome of conflict resolution strategies is to analyze the impact on the problem itself. Did the strategies effectively address the root cause of the conflict and lead to a satisfactory resolution? This can be assessed by gathering feedback and input from all parties involved in the conflict, including employees, managers, and stakeholders. By understanding their perspectives and assessing their level of satisfaction, management can gain valuable insights into the effectiveness of the implemented strategies.

Another important aspect to evaluate is the impact of conflict resolution strategies on the overall problem-solving cycles within the organization. Did the strategies streamline the problem-solving process and improve efficiency? Were conflicts resolved in a timely manner, minimizing disruptions to workflow? Evaluating these factors can help management identify areas for improvement and make adjustments to the conflict resolution strategies if necessary.

Furthermore, the success of conflict resolution strategies can also be measured by analyzing the long-term effects on employee morale and productivity. Did the strategies foster a positive work environment and improve team dynamics? Did employees feel heard and respected during the conflict resolution process? Evaluating the impact on employee satisfaction and engagement can provide management with valuable insights into the effectiveness of the strategies and their ability to promote a harmonious workplace.

Overall, evaluating the outcome of conflict resolution strategies is crucial for organizations seeking to optimize their conflict management processes. By assessing the impact on the problem itself, the overall problem-solving cycles, and employee morale and productivity, management can identify successful strategies and make informed decisions for future conflict resolution endeavors.

Questions and answers:

What are some effective conflict management strategies for problem solving cycles.

Some effective conflict management strategies for problem solving cycles include active listening, clear communication, collaboration, compromising and seeking win-win solutions.

How can active listening help in managing conflicts during problem solving cycles?

Active listening is a crucial conflict management strategy during problem solving cycles as it involves fully focusing on and understanding the perspectives of all parties involved. It helps in building empathy, trust and creating a safe space for open communication which can lead to better problem solving and resolution.

Why is clear communication important in conflict management during problem solving cycles?

Clear communication is important in conflict management during problem solving cycles because it helps in avoiding misunderstandings and promotes effective collaboration. When the parties involved clearly express their needs, concerns and ideas, it becomes easier to find common ground and work towards a mutually beneficial solution.

What role does collaboration play in effective conflict management during problem solving cycles?

Collaboration is a key strategy in effective conflict management during problem solving cycles as it involves actively working together to find a solution that meets the needs and interests of all parties involved. It promotes the sharing of ideas, the pooling of resources and the cultivation of a sense of ownership over the problem-solving process, leading to more sustainable and satisfactory outcomes.

How can compromising and seeking win-win solutions aid in conflict management during problem solving cycles?

Compromising and seeking win-win solutions are important conflict management strategies during problem solving cycles as they help in finding a middle ground between conflicting parties. Compromising involves finding a solution that partially satisfies the needs of all parties, while seeking win-win solutions involves finding creative and mutually beneficial outcomes that address the interests of all parties involved.

Effective conflict management strategies for problem solving cycles include active listening, open communication, finding common ground, and seeking win-win solutions.

How can active listening help in conflict management during problem solving cycles?

Active listening can help in conflict management during problem solving cycles by ensuring that all parties feel heard and understood. It involves giving full attention to the speaker, paraphrasing and summarizing their points, and asking clarifying questions.

Related posts:

- The Stages of the Problem Solving Cycle in Cognitive Psychology – Understanding, Planning, Execution, Evaluation, and Reflection

- The Importance of Implementing the Problem Solving Cycle in Education to Foster Critical Thinking and Problem-Solving Skills in Students

- A Comprehensive Guide to the Problem Solving Cycle in Psychology – Strategies, Techniques, and Applications

- The Step-by-Step Problem Solving Cycle for Effective Solutions

- The Importance of the Problem Solving Cycle in Business Studies – Strategies for Success

- The Comprehensive Guide to the Problem Solving Cycle in PDF Format

- A Comprehensive Guide on the Problem Solving Cycle – Step-by-Step Approach with Real-Life Example

- The Seven Essential Steps of the Problem Solving Cycle

Outside USA: +1‑607‑330‑3200

Applying a Problem‑Solving Approach to Conflict Cornell Course

Course overview.

When most of us face conflict, we often either avoid dealing with it, or we jump in and try to force a solution. These responses may be driven by a lack of comfort with or even a fear of conflict. Unfortunately, neither response is always correct, and neither approach should be the first step. Professors Klingel and Nobles will share how to overcome these instincts and successfully apply a problem-solving approach to conflict.

The first course in this series, “Diagnosing Workplace Conflict,” focused on fully diagnosing a conflict without jumping into problem solving. In this course, you'll look at how to best handle a fully diagnosed conflict using a problem-solving approach. A common issue we'll address is jumping to solutions before understanding the scope of the conflict and the needs that will have to be addressed to resolve it. Thus, you'll begin by determining the scope. Depending on the scope you may move forward with the problem-solving approach, or, you may decide to let it go. The problem-solving approach, which consists of eight steps that can be broken down into three key elements, is the framework through which this course is taught. In the course project, you'll practice applying this approach to a conflict of your choosing. The approach is intended to be used when solving conflict you are directly involved in. Despite this, we'll offer practical advice on how you could adapt this for other use cases.

You are required to have completed the following course or have equivalent experience before taking this course:

- Diagnosing Workplace Conflict

Key Course Takeaways

- Move from conflict diagnosis to problem solving

- Determine the scope of the conflict and how to proceed

- Determine the problem, interests, and criteria for successful resolution

- Generate options and agree on a solution

- Implement and monitor a measurable solution

Download a Brochure

How it works, course authors.

- Certificates Authored

Katrina Nobles is the Director of Conflict Programs for the Scheinman Institute on Conflict Resolution at the Cornell University ILR School, focusing on educating the next generation of neutrals and practitioners on campus and in the workplace. Professor Nobles designs curriculum, instructs professional programs, and facilitates discussions for organizational workplace conflicts. She also teaches the Campus Mediation Practicum, an on-campus credit course that applies mediation skills to the campus judicial system, allowing students to work as peer mediators.

Professor Nobles has presented at national conflict resolution conferences on facilitating collaborative problem solving, cross-cultural communication, and conflict diagnosis. She has practiced mediation for over 15 years, and prior to her employment at Cornell, Professor Nobles was the Cortland County Coordinator for New Justice Mediation Services. During that time, she mediated hundreds of community, child custody/visitation, child support, and family disputes. Professor Nobles holds a Master’s degree in Conflict Analysis and Engagement from Antioch University Midwest.

- Conflict Resolution

Sally Klingel is the director of Labor-Management Relations programming for the Scheinman Institute on Conflict Resolution in Cornell’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations. She specializes in the design and implementation of conflict and negotiation systems, labor-management partnerships, collective bargaining strategies, strategic planning, and leadership development. Her work with Cornell over the past 20 years has included training, consulting, and research with organizations in a variety of industries, local, state and federal government agencies, union internationals and locals, public schools and universities, and worker owned companies.

Sally Klingel holds a M.S. in Organizational Behavior from Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations, and a B.A. from the University of Michigan. She has authored articles, monographs and book chapters on innovations in labor-management relations and conflict methods.

- Labor Relations

Who Should Enroll

Stack to a certificate, request information now by completing the form below..

Enter your information to get access to a virtual open house with the eCornell team to get your questions answered live.

- Online Degree Explore Bachelor’s & Master’s degrees

- MasterTrack™ Earn credit towards a Master’s degree

- University Certificates Advance your career with graduate-level learning

- Top Courses

- Join for Free

Conflict Management: Definition, Strategies, and Styles

Learn how to manage disputes at home or work using various conflict management styles and strategies.

![problem solving cycles conflict management [Featured Image] A manager discusses conflict management with her team in front of a whiteboard.](https://d3njjcbhbojbot.cloudfront.net/api/utilities/v1/imageproxy/https://images.ctfassets.net/wp1lcwdav1p1/5eQLJ54kbGeaaNTdEZRv0Y/638bc2355bc8705c08573c7f231257fc/GettyImages-1322313718__1_.jpg?w=1500&h=680&q=60&fit=fill&f=faces&fm=jpg&fl=progressive&auto=format%2Ccompress&dpr=1&w=1000)

Conflict management is an umbrella term for the way we identify and handle conflicts fairly and efficiently. The goal is to minimize the potential negative impacts that can arise from disagreements and increase the odds of a positive outcome.

At home or work, disagreements can be unpleasant, and not every dispute calls for the same response. Learn to choose the right conflict management style, and you'll be better able to respond constructively whenever disputes arise.

Learn key approaches to conflict management

If you want to learn conflict management skills and approaches, consider enrolling in UC Irvine's Conflict Management Specialization . Start learning with Coursera Plus today with a free 7-day trial.

What is conflict management?

Conflict management refers to the way that you handle disagreements. On any given day, you may have to deal with a dispute between you and another individual, your family members, or fellow employees.

Although there are many reasons people disagree, many conflicts revolve around:

Personal values (real or perceived)

Perceptions

Conflicting goals

Power dynamics

Communication style

Build job-ready skills with a Coursera Plus subscription

- Get access to 7,000+ learning programs from world-class universities and companies, including Google, Yale, Salesforce, and more

- Try different courses and find your best fit at no additional cost

- Earn certificates for learning programs you complete

- A subscription price of $59/month, cancel anytime

5 conflict management styles

It's human to deal with conflict by defaulting to what's comfortable. According to University of Pittsburgh professors of management Ken Thomas and Ralph Kilmann, most people take one of two approaches to conflict management, assertiveness or cooperativeness [ 1 ]. From these approaches come five modes or styles of conflict management:

1. Accommodating

An accommodating mode of conflict management tends to be high in cooperation but low in assertiveness. When you use this style, you resolve the disagreement by sacrificing your own needs and desires for those of the other party.

This management style might benefit your work when conflicts are trivial and you need to move on quickly. At home, this style works when your relationship with your roommate, partner, or child is more important than being right. Although accommodation might be optimal for some conflicts, others require a more assertive style.

2. Avoiding

When avoiding, you try to dodge or bypass a conflict. This style of managing conflicts is low in assertiveness and cooperativeness. Avoidance is unproductive for handling most disputes because it may leave the other party feeling like you don't care. Also, if left unresolved, some conflicts become much more troublesome.

However, an avoiding management style works in situations where:

You need time to think through a disagreement.

You have more pressing problems to deal with first.

The risks of confronting a problem outweigh the benefits.

3. Collaborating

A collaborating conflict management style demands a high level of cooperation from all parties involved. Individuals in a dispute come together to find a respectful resolution that benefits everyone. Collaborating works best if you have plenty of time and are on the same power level as the other parties involved. If not, you may be better off choosing another style.

4. Competing

When you use a competitive conflict management style (sometimes called 'forcing'), you put your own needs and desires over those of others. This style is high in assertiveness and low in cooperation. In other words, it's the opposite of accommodating. While you might think this style would never be acceptable, it's sometimes needed when you are in a higher position of power than other parties and need to resolve a dispute quickly.

5. Compromising

Compromising demands moderate assertiveness and cooperation from all parties involved. With this type of resolution, everyone gets something they want or need. This style of managing conflict works well when time is limited. Because of time constraints, compromising isn't always as creative as collaborating, and some parties may come away less satisfied than others.

Learn more about these conflict management approaches in this video from Rice University:

Tips for choosing a conflict management style

The key to successfully managing conflict is choosing the right style for each situation. For instance, it might make sense to use avoidance or accommodation to deal with minor issues, while critical disputes may call for a more assertive approach, like a competitive conflict management style. When you're wondering which method of conflict management to choose, ask yourself the following questions:

How important are your needs and wants?

What will happen if your needs and wants aren't met?

How much do you value the other person/people involved?

How much value do you place on the issue involved?

Have you thought through the consequences of using differing styles?

Do you have the time and energy to address the situation right now?

The answers to these questions can help you decide which style to pick in a particular situation based on what you've learned about the various conflict management styles.

Tips and strategies for conflict management

Conflicts inevitably pop up when you spend time with other people, whether at work or home. However, when conflicts aren’t resolved, they can lead to various negative consequences. These include:

Hurt feelings

Resentment and frustration

Loneliness and depression

Passive aggression and communication issues

Increased stress and stress-related health problems

Reduced productivity

Staff turnover

Conflict is a part of life. Knowing a few strategies for managing conflict can help keep your home or workplace healthy. Here are a few tips to keep in mind when conflict arises:

Acknowledge the problem.

If someone comes to you with a dispute that seems trivial to you, remember it may not be trivial to them. Actively listen to help the other person feel heard, then decide what to do about the situation.

Gather the necessary information.

You can't resolve a conflict unless you've investigated all sides of the problem. Take the time you need to understand all the necessary information. This way, you'll choose the best conflict management style and find an optimal resolution.

Set guidelines.

Whether discussing a conflict with a spouse or intervening for two employees, setting guidelines before you begin is essential. Participants should agree to speak calmly, listen, and try to understand the other person's point of view. Agree up front that if the guidelines aren't followed, the discussion will end and resume later.

Keep emotion out of the discussion.

An angry outburst may end a conflict, but it's only temporary. Talk things out calmly to avoid having the dispute pop up again.

Be decisive.

Once you've discussed a dispute and evaluated the best approach, take action on the solution you've identified. Letting others in on your decision lets them know you care and are moving forward.

Build conflict management skills today

Learn key conflict types and strategies to resolve them. Enroll in the Conflict Management Specialization from UC Irvine today to build your skills.

Article sources

Management Weekly. " Thomas Kilmann Conflict Model , https://managementweekly.org/thomas-kilmann-conflict-resolution-model/." Accessed March 13, 2024.

Keep reading

Coursera staff.

Editorial Team

Coursera’s editorial team is comprised of highly experienced professional editors, writers, and fact...

This content has been made available for informational purposes only. Learners are advised to conduct additional research to ensure that courses and other credentials pursued meet their personal, professional, and financial goals.

- Onsite training

3,000,000+ delegates

15,000+ clients

1,000+ locations

- KnowledgePass

- Log a ticket

01344203999 Available 24/7

Conflict Management Cycle: A Complete Guide

Conflict Management Cycle is a dynamic process designed to navigate and resolve conflicts efficiently. Discover how this cycle guides you through conflict identification, analysis, resolution, and post-conflict evaluation. Learn to foster a more harmonious environment through effective conflict management strategies in our insightful blog.

Exclusive 40% OFF

Training Outcomes Within Your Budget!

We ensure quality, budget-alignment, and timely delivery by our expert instructors.

Share this Resource

- Active Listening Training

- Managing Difficult Conversations Training

- Problem Solving Course

- Consulting Skills Training

- Dealing with Difficult People

With the increased pace of life, conflicts arise more than ever today. According to the Myers Briggs research, out of the people surveyed, 36% reported that they have dealt with conflict often, very often, and even at the workplace. So, it’s time to address the issue to drive your business towards success.

But how to eliminate conflicts? What approach can organisations adopt? Read this blog to learn about Conflict Management Cycle. Also, explore various strategies to manage conflicts successfully.

Table of Contents

1) What is Conflict Management?

2) The Conflict Management Cycle explained

a) Stage 1: Proactive phase

b) Stage 2: Strategic phase

c) Stage 3: Reactive phase

d) Stage 4: Recovery phase

3) Key strategies for effective conflict resolution

4) Conclusion

What is Conflict Management?

Conflicts are natural occurrences that arise when there is a clash of interests, differing perspectives, or disagreement on certain issues. They can arise in various contexts, including personal relationships, professional environments, and even within our own minds. Conflict Management is crucial in maintaining healthy relationships, promoting effective communication, and fostering positive outcomes.

It refers to the process of handling and resolving conflicts constructively and productively. It involves a set of strategies, techniques, and skills aimed at understanding, addressing, and finding solutions to conflicts that arise between individuals and groups.

The Conflict Management Cycle explained

Conflicts can be complex and dynamic, requiring a systematic approach to effectively address and resolve them. The Conflict Management Cycle provides a framework that guides us through the various stages of conflict resolution. Each stage plays a vital role in understanding, managing, and finding resolutions to conflicts. So, let’s explore the four key stages of this cycle:

Stage 1: Proactive phase

The proactive phase marks the initial stage of the Conflict Management Cycle. It involves taking preventive measures and creating an environment that minimises the likelihood of conflicts arising.

This stage primarily emphasises proactive communication, fostering positive relationships, and establishing clear expectations and guidelines. As a result, individuals and organisations can reduce the occurrence and severity of conflicts.

Stage 2: Strategic phase

The strategic phase in Conflict Management Cycle is where conflicts are identified, assessed, and analysed. This stage focuses on understanding the nature and causes of conflicts, gathering relevant information, and evaluating their potential impact.

Further, it involves conducting a thorough analysis of the underlying issues, interests, and needs of all parties involved. By employing active listening, effective communication, and problem-solving techniques, individuals can develop strategies for resolution and gain insights into the root causes of conflicts.

Ready to enhance your Conflict Management skills? Register for our Management Training now.

Stage 3: Reactive phase

In the reactive phase, the focus shifts towards addressing conflicts immediately. This stage involves implementing the strategies and interventions developed during the previous phase. It requires effective communication, negotiation skills, and a willingness to find mutually beneficial solutions.

This phase aims to manage conflicts promptly and constructively, minimising further escalation and damage. By engaging in respectful dialogue, considering different perspectives, and exploring collaborative solutions, individuals can work towards resolving conflicts effectively.

Stage 4: Recovery phase

The recovery phase occurs after conflicts have been addressed and resolved. It involves reflecting on the conflict experience, learning from it, and implementing measures to prevent similar conflicts in the future.

This stage emphasises evaluating the outcomes, identifying lessons learned, and implementing changes to improve future Conflict Management. The recovery phase also focuses on rebuilding relationships, restoring trust, and fostering a positive environment.

Understanding the Conflict Management Cycle and its different stages empowers individuals and organisations to navigate conflicts more effectively. They can drive themselves towards opportunities for growth, understanding, and improved relationships.

Take the next step towards professional growth with our Problem Solving Training .

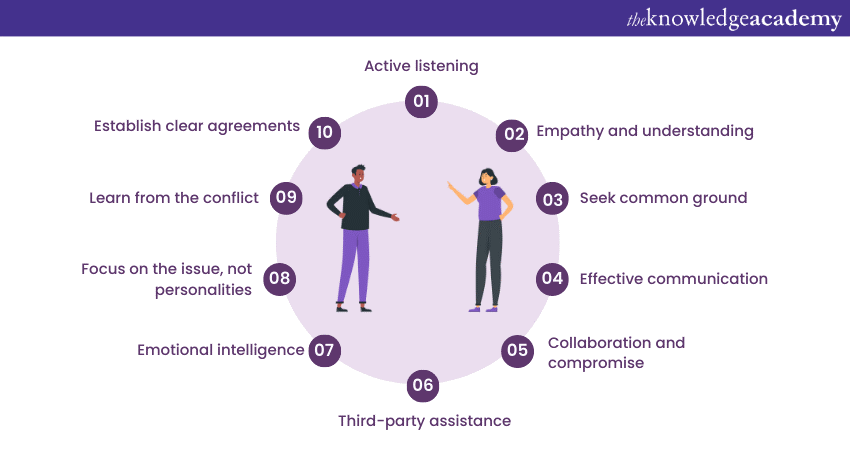

Key strategies for effective conflict resolution

a) Listen attentively to understand all perspectives without interruptions, fostering a deeper understanding of the conflict.

b) Cultivate empathy by considering others' emotions and needs, creating a more compassionate and constructive environment.

c) Focus on shared interests or goals to find collaborative solutions that benefit all parties involved.

d) Communicate clearly and respectfully using “I” statements to express feelings and encourage open dialogue.

e) Be open to alternative viewpoints and find win-win solutions through compromise.

f) Seek neutral third-party help when conflicts escalate or become complex, facilitating resolution.

g) Develop emotional intelligence to understand and manage emotions, promoting self-awareness and empathy.

h) Keep the focus on the conflict, separate individuals from the problem, and address it constructively.

i) Reflect on conflicts, identify lessons learned, and apply them to enhance future Conflict Management skills.

j) Define clear terms, responsibilities, and timelines to ensure understanding and commitment to the resolution.

Conclusion

The Conflict Management Cycle provides a comprehensive framework for effectively addressing and resolving conflicts. By embracing this cycle and employing the strategies, individuals can navigate conflicts with resilience and foster positive resolutions. They can also cultivate a more harmonious and productive environment in various aspects of life.

Gain an in-depth understanding of Conflict Management techniques with our Conflict Management Training .

Frequently Asked Questions

Upcoming business skills resources batches & dates.

Fri 3rd May 2024

Fri 19th Jul 2024

Fri 20th Sep 2024

Fri 1st Nov 2024

Get A Quote

WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE?

My employer

By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry

- Business Analysis

- Lean Six Sigma Certification

Share this course

Our biggest spring sale.

We cannot process your enquiry without contacting you, please tick to confirm your consent to us for contacting you about your enquiry.

By submitting your details you agree to be contacted in order to respond to your enquiry.

We may not have the course you’re looking for. If you enquire or give us a call on 01344203999 and speak to our training experts, we may still be able to help with your training requirements.

Or select from our popular topics

- ITIL® Certification

- Scrum Certification

- Change Management Certification

- Business Analysis Courses

- Microsoft Azure Certification

- Microsoft Excel Courses

- Microsoft Project

- Explore more courses

Press esc to close

Fill out your contact details below and our training experts will be in touch.

Fill out your contact details below

Thank you for your enquiry!

One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go over your training requirements.

Back to Course Information

Fill out your contact details below so we can get in touch with you regarding your training requirements.

* WHO WILL BE FUNDING THE COURSE?

Preferred Contact Method

No preference

Back to course information

Fill out your training details below

Fill out your training details below so we have a better idea of what your training requirements are.

HOW MANY DELEGATES NEED TRAINING?

HOW DO YOU WANT THE COURSE DELIVERED?

Online Instructor-led

Online Self-paced

WHEN WOULD YOU LIKE TO TAKE THIS COURSE?

Next 2 - 4 months

WHAT IS YOUR REASON FOR ENQUIRING?

Looking for some information

Looking for a discount

I want to book but have questions

One of our training experts will be in touch shortly to go overy your training requirements.

Your privacy & cookies!

Like many websites we use cookies. We care about your data and experience, so to give you the best possible experience using our site, we store a very limited amount of your data. Continuing to use this site or clicking “Accept & close” means that you agree to our use of cookies. Learn more about our privacy policy and cookie policy cookie policy .

We use cookies that are essential for our site to work. Please visit our cookie policy for more information. To accept all cookies click 'Accept & close'.

Brought to you by:

Some Aspects of Problem Solving and Conflict Resolution in Management Groups

By: James P. Ware

Provides a brief overview of the strengths and weaknesses of group problem solving and suggests criteria for when to use a group. Also, describes the three primary modes of conflict resolution…

- Length: 13 page(s)

- Publication Date: Sep 1, 1978

- Discipline: Organizational Behavior

- Product #: 479003-PDF-ENG

What's included:

- Educator Copy

$4.95 per student

degree granting course

$8.95 per student

non-degree granting course

Get access to this material, plus much more with a free Educator Account:

- Access to world-famous HBS cases

- Up to 60% off materials for your students

- Resources for teaching online

- Tips and reviews from other Educators

Already registered? Sign in

- Student Registration

- Non-Academic Registration

- Included Materials

Provides a brief overview of the strengths and weaknesses of group problem solving and suggests criteria for when to use a group. Also, describes the three primary modes of conflict resolution (smoothing and avoidance; bargaining and forcing, problem solving) and discusses difficulties experienced by the members of interdepartmental groups. Can be used with cases on group and intergroup conflict.

Sep 1, 1978 (Revised: Nov 1, 1979)

Discipline:

Organizational Behavior

Harvard Business School

479003-PDF-ENG

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

5.2 Small Group Dynamics

In this section:, small group dynamics, power and status in groups, toxic leadership in groups, cultivating a supportive group climate.

Almost every posting for a job opening in a workplace location lists teamwork among the required skills. Why? Is it because every employer writing a job posting copies other job postings? No, it’s because every employer’s business success absolutely depends on people working well in teams to get the job done. A high-functioning, cohesive, and efficient team is essential to workplace productivity anywhere you have three or more people working together. Effective teamwork means working together toward a common goal guided by a common vision, and it’s a mighty force.

Compared with several people working independently, teams maximize productivity through collaborative problem solving. When each member brings a unique combination of skills, talents, experience, and education, their combined efforts make the team synergistic—i..e, more than the sum of its parts. Collaboration can motivate and result in creative solutions not possible in single-contractor projects. The range of views and diversity can energize the process, helping address creative blocks and stalemates. While the “work” part of “teamwork” may be engaging or even fun, it also requires effort and commitment to a production schedule that depends on the successful completion of individual and group responsibilities for the whole project to finish in a timely manner. Like a chain, the team is only as strong as its weakest member.

Teamwork is not without its challenges. The work itself may prove to be difficult as members juggle competing assignments and personal commitments. The work may also be compromised if team members are expected to conform and pressured to follow a plan, perform a procedure, or use a product that they themselves have not developed or don’t support. Groupthink , or the tendency to accept the group’s ideas and actions in spite of individual concerns, can also compromise the process and reduce efficiency. Personalities, competition, and internal conflict can factor into a team’s failure to produce, which is why care must be taken in how teams are assembled and managed.

Establishing a Team

- Select team members wisely

- Select a responsible leader

- Promote cooperation

- Clarify goals

- Elicit commitment

- Clarify responsibilities

- Instill prompt action

- Apply technology

- Ensure technological compatibility

- Provide prompt feedback

Source: Thill & Bovee, (2002).

Group dynamics involve the interactions and processes of a team and influence the degree to which members feel a part of the goal and mission. A team with a strong identity can prove to be a powerful force. One that exerts too much control over individual members, however, runs the risk or reducing creative interactions, resulting in tunnel vision. A team that exerts too little control, neglecting all concern for process and areas of specific responsibility, may go nowhere. Striking a balance between motivation and encouragement is key to maximizing group productivity.

A skilled communicator creates a positive team by first selecting members based on their areas of skill and expertise. Attention to each member’s style of communication also ensures the team’s smooth operation. If their talents are essential, introverts who prefer working alone may need additional encouragement to participate. Extroverts may need encouragement to listen to others and not dominate the conversation. Both are necessary, however, so the selecting for a diverse group of team members deserves serious consideration.

Positive and Negative Team Roles

When a manager selects a team for a particular project, its success depends on its members filling various positive roles. There are a few standard roles that must be represented to achieve the team’s goals, but diversity is also key. Without an initiator-coordinator stepping up into a leadership position, for instance, the team will be a non-starter because team members such as the elaborator will just wait for more direction from the manager, who is busy with other things. If all the team members commit to filling a leadership role, however, the group will stall from the get-go with power struggles until the most dominant personality vanquishes the others, who will be bitterly unproductive relegated to a subordinate worker-bee role. A good manager must therefore be a good psychologist in building a team with diverse personality types and talents. Table 5.1 below captures some of these roles.

Table 5.1 Positive Group Roles

Of course, each team member here contributes work irrespective of their typical roles. The groupmate who always wanted to be recorder in high school because they thought that all they had to do what jot down some notes about what other people said and did, and otherwise contributed nothing, would be a liability as a slacker in a workplace team. We must therefore contrast the above roles with negative roles, some of which are captured in Table 5.2 below.

Table 5.2 Negative Group Roles

Original Source: Beene & Sheats, 1948; McLean, 2005

Whether a team member has a positive or negative effect often depends on context. Just as the class clown can provide some much-needed comic relief when the timing’s right, they can also impede productivity when they merely distract members during work periods. An initiator-coordinator gets things started and provides direction, but a dominator will put down others’ ideas, belittle their contributions, and ultimately force people to contribute little and withdraw partially or altogether.

Perhaps the worst of all roles is the slacker. If you consider a game of tug-o-war between two teams of even strength, success depends on everyone on the team pulling as hard as they would if they were in a one-on-one match. The tendency of many, however, is to slack off a little, thinking that their contribution won’t be noticed and that everyone else on the team will make up for their lack of effort. The team’s work output will be much less than the sum of its parts, however, if everyone else thinks this, too. Preventing slacker tendencies requires clearly articulating in writing the expectations for everyone’s individual contributions. With such a contract to measure individual performance, each member can be held accountable for their work and take pride in their contribution to solving all the problems that the team overcame on its road to success.

Recall back to our discussion of power and its bases. In a group or team, members with higher status are apt to command greater respect and possess more prestige and power than those with lower status. Status an be defined as a person’s perceived level of importance or significance within a particular context.

Our status is often tied to our identities and their perceived value within our social and cultural context. Groups may confer status upon their members on the basis of their age, wealth, gender, race or ethnicity, ability, physical stature, perceived intelligence, and/or other attributes. Status can also be granted through title or position. In professional circles, for instance, having earned a “terminal” degree such as a Ph.D. or M.D. usually generates a degree of status. The same holds true for the documented outcomes of schooling or training in legal, engineering, or other professional fields. Likewise, people who’ve been honored for achievements in any number of areas may bring status to a group by virtue of that recognition if it relates to the nature and purpose of the group. Once a group has formed and begun to sort out its norms, it will also build upon the initial status that people bring to it by further allocating status according to its own internal processes and practices. For instance, choosing a member to serve as an officer in a group generally conveys status to that person.

Consider This: High Stakes in Action

What does high status look like in action.

Second, some indicators of your participation will be particularly positive. Your activity level and self-regard will surpass those of lower-status group members. So will your level of satisfaction with your position. Furthermore, the rest of the group is less likely to ignore your statements and proposals than it is to disregard what lower-status individuals say.

Finally, the content of your communication will probably be different from what your fellow members discuss. Because you may have access to special information about the group’s activities and may be expected to shoulder specific responsibilities because of your position, you’re apt to talk about topics which are relevant to the central purposes and direction of the group. Lower-status members, on the other hand, are likely to communicate more about other matters.

There’s no such thing as a “status neutral” group—one in which everyone always has the same status as everyone else. Differences in status within a group are inevitable and can be dangerous if not recognized and managed. For example, someone who gains status without possessing the skills or attributes required to use it well may cause real damage to other members of a group, or to a group as a whole. A high-status, low-ability person may develop an inflated self-image, begin to abuse power, or both. One of us worked for the new president of a college who acted as though his position entitled him to take whatever actions he wanted. In the process of interacting primarily with other high-status individuals who shared the majority of his viewpoints and goals, he overlooked or rejected concerns and complaints from people in other parts of the organization. Turmoil and dissension broke out. Morale plummeted. The president eventually suffered votes of no confidence from his college’s faculty, staff, and students and was forced to resign.

We’ve focused for the most part on effective leadership, but what happens if you find yourself working under a horrible manager or team leader? It happens. Plenty of people assume positions of authority who are effective in some areas of management (e.g., they are shrewd business people and good with money) but aren’t so good with people, or vice versa. There are even managers who are bad at everything and it’s only a matter of time before they are fired or ruin the operation with incompetence, or they may continue to be propped up by cronyism, nepotism, or some other kind of corruption. Some people are even offensive to the point of committing harassment along a spectrum of misbehaviour ranging from inappropriate jokes or rude remarks to outright predatory sexual harassment or assault and violence. Whatever the case, nothing good comes of toxic leadership. Employees just aren’t productive when fearing abuse from their managers or worrying about the their leadership running the operation into the ground.

If the mismanagement is severe—especially if it is physically or emotionally abusive—the best way of dealing with the situation is to leave it. A person at work who makes you feel unsafe may suffer from a personality disorder that makes them dangerous, and there’s no fixing that. If you’re in immediate danger, of course you must leave immediately. From there, figure out your options. For starters, you could consider the following: