Flexibility in Online Learning: What It Means for Students

Flexibility allows students to get to know themselves better and schedule their learning schedule accordingly. This means that the time their focus is high and their capability of retaining information is significant is when they will start their learning. In time, it will lead to them having better results.

This article is part of the Flexible Learning Guide . Learn all about Flexible Thinking Activities , Flexible Learning Environments , and Flexibility in the Classroom .

Nowadays, there is a necessity for online learning, and institutions are trying to answer this need by offering the chance to study online or hybrid. The flexibility of online studies helps students worldwide have access to education without worrying about location, time or quality.

Traditional student or not, the changing environment and the social and economic factors that evolve make life as a student more demanding. This, along with the classes, may prove too much.

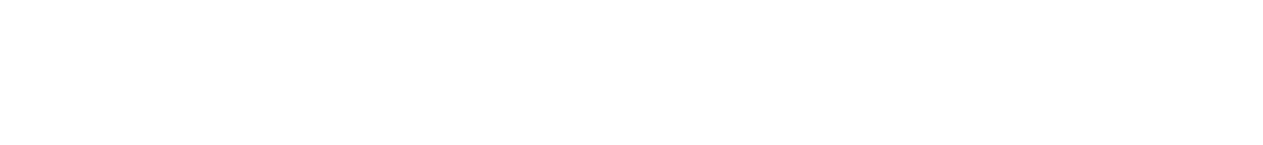

Flexible learning also comes as help to increase access to higher education, particularly as worldwide enrollments are expected to double by 2025 ( Maslen, 2012 ).

Having the flexibility of online education will give students peace of mind, will allow them to take things at their own pace and learn at their own will while also continuing to pursue their passions.

The flexibility in online learning has a primary significance – it offers bigger freedom to students. This is the most appealing factor as far as the flexibility of online learning is concerned.

The key elements of flexible online learning are – pace, place and mode. ( Gordon, 2014 )

The Importance of flexibility in online learning

Mostly the reason people choose online learning is because of the flexibility it offers.

As technology evolves, online learning can offer experiences equal to offline classes. It can do this through gamification, virtual and augmented reality. All of them will create a richer learning experience that will provide students with the same experience as the class learning.

While online learning is increasing, making it more flexible is a plus.

What does flexibility in online learning mean?

It mainly refers to the fact that you can study the course materials anytime your desire.

However, it does not mean a lack of structure, guidance and support. Flexible online learning also offers flexible help from tutors and mentors that guide you through the course .

Effects of flexible online learning on students

– A more significant focus on the comfort and quiet environment of your study place. Flexible online learning means “how, what, when and where [individuals] learn: the pace, place and mode of delivery” ( Higher Education Academy [HEA], 2015, para 1 )

– It allows them to take charge of their life.

– It offers them greater satisfaction when they know they can study while also continuing with their passions.

The benefits of a flexible online learning program

There are various benefits that a flexible online learning program offers. Due to technological advancement, you can follow an online education system and do not feel the lack of socialising and interaction with your colleagues.

Some of the main benefits of a flexible learning program are:

– Flexibility to speed up your degree at your own pace. While in conventional classes, teachers have their speed and usually have to tick a task on the learning board and rush students into understanding a subject, having the possibility to tackle the subject at your own pace is excellent.

– Comfort to study from anywhere. There is a direct connection between feeling comfortable in your learning environment and the learning results. Thus, if you are in a familiar atmosphere, it may make you feel like you do not have to worry about anything else but focus on studying.

– No need for long commutes as you virtually enter to have any class. Sometimes getting to school may prove a challenge as you need to wake up an hour earlier to get ready and then commute to school. Losing at least two hours per day on commuting is sometimes frustrating when you have a lot of homework.

– You are in complete control of your studying program, just like you are in a workplace. This will get you readier to balance the work-life when needed.

Advantages and disadvantages of online learning

– Students develop their responsibility.

– Students become aware of the importance of organising.

– Online learning helps students be more independent.

– It increases the student’s confidence in making decisions for their future.

– You can connect with people worldwide as it has no boundaries.

– Easier to attend classes.

– Access for a bigger number of students to education.

Disadvantages

A significant disadvantage of online learning is the separation it may cause between those with internet access, access to various and improved computer systems, those that have a computer and those in developing countries where technology and accessibility of it are two things they do not focus on nor have.

If you have trouble committing to something if it is not mandatory, choosing online learning can be a trick. Not committing to a studying schedule will leave you behind in classes, and you will have trouble making up for so many courses.

Some students may have an increased sense of isolation if they opt for online learning. The minimal physical interaction is necessary for some who feel this interaction gives them moral support.

Related Terms

Distance learning vs online learning .

The distance learning concept existed long before online learning. It is a kind of learning where students are given the learning materials and can go through them as they wish. In addition to the courses, students should attend some live sessions.

In comparison, online learning is where students have online access to the courses and can access them when they want. It also provides self-assessment materials for students. It can come with support from the tutor or mentor.

flexible learning vs online learning

Flexible learning allows students to choose when, how and where to learn. It does not necessarily have to be online. It addresses how to use the physical learning space, group students while learning, discuss topics, and learn pace.

E-learning is a need because of its flexibility regarding the pace, place, and mode of learning. However, online learning can be flexible as well. These days this is what online learning is all about – flexibility.

modular learning vs online learning

Modular learning is a type of class where students receive teh course materials in handouts to study until a specific deadline. The handout type provides the same access to materials for everyone and an easier way to study – as the information is summarised. With the modular classes, students can show what they learned only at the deadline.

Online classes offer students the ability to communicate constantly online and give and receive feedback on their course understanding and tasks. Online learning, in comparison, is done online and has no deadline for the lessons. The course is not summarised, and each student can take their understanding of the course.

There certainly are two teams – those pros and those against online learning. However, it is essential to bear in mind that online learning came not as a replacement for the traditional learning system but as a help to those students that cannot follow a conventional learning system from various considerations. There is no need to judge any of the teams as each learning type has its advantages and disadvantages.

When choosing what best suits you as a student, focus on the one solution with the most advantages.

Flexible Online Learning FAQ

How is online school more flexible .

Just being online, having the chance to study the courses at your own will, having the opportunity to review them every time you want for a better understanding and having the chance to study anytime fits your schedule gives the online school the flexibility most students look for. Besides all this, it allows students to choose the courses they want to have.

What are the advantages of flexible learning?

Flexible learning helps students

– Continue their extracurricular activities

– Choose their courses

– Make their schedule

– Learn at their own will

– Become more responsible

– Develop organising skills

What is a flexible online class?

A flexible online class is a class that allows students to learn when they want, how they want and from where they want.

Why You Should Enrol in an Online Learning Subscription

Unlimited Learning Subscription: Learn Without Limits

How can I get my high school diploma online?

Join our community of superheroes.

Your superhero story begins with a simple click. Sign up for our newsletter and embrace a journey where you're not only learning but also finding your cape - your unique superpower.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 25 January 2021

Online education in the post-COVID era

- Barbara B. Lockee 1

Nature Electronics volume 4 , pages 5–6 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

139k Accesses

209 Citations

337 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Science, technology and society

The coronavirus pandemic has forced students and educators across all levels of education to rapidly adapt to online learning. The impact of this — and the developments required to make it work — could permanently change how education is delivered.

The COVID-19 pandemic has forced the world to engage in the ubiquitous use of virtual learning. And while online and distance learning has been used before to maintain continuity in education, such as in the aftermath of earthquakes 1 , the scale of the current crisis is unprecedented. Speculation has now also begun about what the lasting effects of this will be and what education may look like in the post-COVID era. For some, an immediate retreat to the traditions of the physical classroom is required. But for others, the forced shift to online education is a moment of change and a time to reimagine how education could be delivered 2 .

Looking back

Online education has traditionally been viewed as an alternative pathway, one that is particularly well suited to adult learners seeking higher education opportunities. However, the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has required educators and students across all levels of education to adapt quickly to virtual courses. (The term ‘emergency remote teaching’ was coined in the early stages of the pandemic to describe the temporary nature of this transition 3 .) In some cases, instruction shifted online, then returned to the physical classroom, and then shifted back online due to further surges in the rate of infection. In other cases, instruction was offered using a combination of remote delivery and face-to-face: that is, students can attend online or in person (referred to as the HyFlex model 4 ). In either case, instructors just had to figure out how to make it work, considering the affordances and constraints of the specific learning environment to create learning experiences that were feasible and effective.

The use of varied delivery modes does, in fact, have a long history in education. Mechanical (and then later electronic) teaching machines have provided individualized learning programmes since the 1950s and the work of B. F. Skinner 5 , who proposed using technology to walk individual learners through carefully designed sequences of instruction with immediate feedback indicating the accuracy of their response. Skinner’s notions formed the first formalized representations of programmed learning, or ‘designed’ learning experiences. Then, in the 1960s, Fred Keller developed a personalized system of instruction 6 , in which students first read assigned course materials on their own, followed by one-on-one assessment sessions with a tutor, gaining permission to move ahead only after demonstrating mastery of the instructional material. Occasional class meetings were held to discuss concepts, answer questions and provide opportunities for social interaction. A personalized system of instruction was designed on the premise that initial engagement with content could be done independently, then discussed and applied in the social context of a classroom.

These predecessors to contemporary online education leveraged key principles of instructional design — the systematic process of applying psychological principles of human learning to the creation of effective instructional solutions — to consider which methods (and their corresponding learning environments) would effectively engage students to attain the targeted learning outcomes. In other words, they considered what choices about the planning and implementation of the learning experience can lead to student success. Such early educational innovations laid the groundwork for contemporary virtual learning, which itself incorporates a variety of instructional approaches and combinations of delivery modes.

Online learning and the pandemic

Fast forward to 2020, and various further educational innovations have occurred to make the universal adoption of remote learning a possibility. One key challenge is access. Here, extensive problems remain, including the lack of Internet connectivity in some locations, especially rural ones, and the competing needs among family members for the use of home technology. However, creative solutions have emerged to provide students and families with the facilities and resources needed to engage in and successfully complete coursework 7 . For example, school buses have been used to provide mobile hotspots, and class packets have been sent by mail and instructional presentations aired on local public broadcasting stations. The year 2020 has also seen increased availability and adoption of electronic resources and activities that can now be integrated into online learning experiences. Synchronous online conferencing systems, such as Zoom and Google Meet, have allowed experts from anywhere in the world to join online classrooms 8 and have allowed presentations to be recorded for individual learners to watch at a time most convenient for them. Furthermore, the importance of hands-on, experiential learning has led to innovations such as virtual field trips and virtual labs 9 . A capacity to serve learners of all ages has thus now been effectively established, and the next generation of online education can move from an enterprise that largely serves adult learners and higher education to one that increasingly serves younger learners, in primary and secondary education and from ages 5 to 18.

The COVID-19 pandemic is also likely to have a lasting effect on lesson design. The constraints of the pandemic provided an opportunity for educators to consider new strategies to teach targeted concepts. Though rethinking of instructional approaches was forced and hurried, the experience has served as a rare chance to reconsider strategies that best facilitate learning within the affordances and constraints of the online context. In particular, greater variance in teaching and learning activities will continue to question the importance of ‘seat time’ as the standard on which educational credits are based 10 — lengthy Zoom sessions are seldom instructionally necessary and are not aligned with the psychological principles of how humans learn. Interaction is important for learning but forced interactions among students for the sake of interaction is neither motivating nor beneficial.

While the blurring of the lines between traditional and distance education has been noted for several decades 11 , the pandemic has quickly advanced the erasure of these boundaries. Less single mode, more multi-mode (and thus more educator choices) is becoming the norm due to enhanced infrastructure and developed skill sets that allow people to move across different delivery systems 12 . The well-established best practices of hybrid or blended teaching and learning 13 have served as a guide for new combinations of instructional delivery that have developed in response to the shift to virtual learning. The use of multiple delivery modes is likely to remain, and will be a feature employed with learners of all ages 14 , 15 . Future iterations of online education will no longer be bound to the traditions of single teaching modes, as educators can support pedagogical approaches from a menu of instructional delivery options, a mix that has been supported by previous generations of online educators 16 .

Also significant are the changes to how learning outcomes are determined in online settings. Many educators have altered the ways in which student achievement is measured, eliminating assignments and changing assessment strategies altogether 17 . Such alterations include determining learning through strategies that leverage the online delivery mode, such as interactive discussions, student-led teaching and the use of games to increase motivation and attention. Specific changes that are likely to continue include flexible or extended deadlines for assignment completion 18 , more student choice regarding measures of learning, and more authentic experiences that involve the meaningful application of newly learned skills and knowledge 19 , for example, team-based projects that involve multiple creative and social media tools in support of collaborative problem solving.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, technological and administrative systems for implementing online learning, and the infrastructure that supports its access and delivery, had to adapt quickly. While access remains a significant issue for many, extensive resources have been allocated and processes developed to connect learners with course activities and materials, to facilitate communication between instructors and students, and to manage the administration of online learning. Paths for greater access and opportunities to online education have now been forged, and there is a clear route for the next generation of adopters of online education.

Before the pandemic, the primary purpose of distance and online education was providing access to instruction for those otherwise unable to participate in a traditional, place-based academic programme. As its purpose has shifted to supporting continuity of instruction, its audience, as well as the wider learning ecosystem, has changed. It will be interesting to see which aspects of emergency remote teaching remain in the next generation of education, when the threat of COVID-19 is no longer a factor. But online education will undoubtedly find new audiences. And the flexibility and learning possibilities that have emerged from necessity are likely to shift the expectations of students and educators, diminishing further the line between classroom-based instruction and virtual learning.

Mackey, J., Gilmore, F., Dabner, N., Breeze, D. & Buckley, P. J. Online Learn. Teach. 8 , 35–48 (2012).

Google Scholar

Sands, T. & Shushok, F. The COVID-19 higher education shove. Educause Review https://go.nature.com/3o2vHbX (16 October 2020).

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T. & Bond, M. A. The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. Educause Review https://go.nature.com/38084Lh (27 March 2020).

Beatty, B. J. (ed.) Hybrid-Flexible Course Design Ch. 1.4 https://go.nature.com/3o6Sjb2 (EdTech Books, 2019).

Skinner, B. F. Science 128 , 969–977 (1958).

Article Google Scholar

Keller, F. S. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 1 , 79–89 (1968).

Darling-Hammond, L. et al. Restarting and Reinventing School: Learning in the Time of COVID and Beyond (Learning Policy Institute, 2020).

Fulton, C. Information Learn. Sci . 121 , 579–585 (2020).

Pennisi, E. Science 369 , 239–240 (2020).

Silva, E. & White, T. Change The Magazine Higher Learn. 47 , 68–72 (2015).

McIsaac, M. S. & Gunawardena, C. N. in Handbook of Research for Educational Communications and Technology (ed. Jonassen, D. H.) Ch. 13 (Simon & Schuster Macmillan, 1996).

Irvine, V. The landscape of merging modalities. Educause Review https://go.nature.com/2MjiBc9 (26 October 2020).

Stein, J. & Graham, C. Essentials for Blended Learning Ch. 1 (Routledge, 2020).

Maloy, R. W., Trust, T. & Edwards, S. A. Variety is the spice of remote learning. Medium https://go.nature.com/34Y1NxI (24 August 2020).

Lockee, B. J. Appl. Instructional Des . https://go.nature.com/3b0ddoC (2020).

Dunlap, J. & Lowenthal, P. Open Praxis 10 , 79–89 (2018).

Johnson, N., Veletsianos, G. & Seaman, J. Online Learn. 24 , 6–21 (2020).

Vaughan, N. D., Cleveland-Innes, M. & Garrison, D. R. Assessment in Teaching in Blended Learning Environments: Creating and Sustaining Communities of Inquiry (Athabasca Univ. Press, 2013).

Conrad, D. & Openo, J. Assessment Strategies for Online Learning: Engagement and Authenticity (Athabasca Univ. Press, 2018).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Education, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA

Barbara B. Lockee

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Barbara B. Lockee .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lockee, B.B. Online education in the post-COVID era. Nat Electron 4 , 5–6 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-020-00534-0

Download citation

Published : 25 January 2021

Issue Date : January 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-020-00534-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

A comparative study on the effectiveness of online and in-class team-based learning on student performance and perceptions in virtual simulation experiments.

BMC Medical Education (2024)

Leveraging privacy profiles to empower users in the digital society

- Davide Di Ruscio

- Paola Inverardi

- Phuong T. Nguyen

Automated Software Engineering (2024)

Growth mindset and social comparison effects in a peer virtual learning environment

- Pamela Sheffler

- Cecilia S. Cheung

Social Psychology of Education (2024)

Nursing students’ learning flow, self-efficacy and satisfaction in virtual clinical simulation and clinical case seminar

- Sunghee H. Tak

BMC Nursing (2023)

Online learning for WHO priority diseases with pandemic potential: evidence from existing courses and preparing for Disease X

- Heini Utunen

- Corentin Piroux

Archives of Public Health (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Flexibility is the biggest benefit of online learning, students say

With many students embarking on a new university semester, the student surveyed more than 2,000 of them for their views on the benefits of online learning versus classroom learning.

The ability to view lectures at any time of day has been the most advantageous part of online learning for students and should remain part of university education, according to the latest THE Student Panel survey.

Being an international student during the Covid-19 pandemic

Discover the University of Liverpools' online postgraduate courses

Asked to list the three greatest advantages of studying online, 45 per cent of respondents who have had some teaching delivered online in the past 12 months said it was viewing lectures at any time of day, followed closely by 44 per cent citing the ability to continue studying during the pandemic and 34 per cent naming the ability to study at their own pace.

The online survey of 2,217 current students and prospective students who are part of the THE Student Pulse panel conducted between 13 July and 5 August 2021 included individuals from more than 120 countries applying to institutions in 91 countries around the world.

Overall, 85 per cent of those surveyed agreed that access to recorded lectures should remain available whether teaching is conducted in-person or online.

Despite warm feelings towards the flexibility that recorded online lectures offered, students still generally prefer studying in person. Just over half (53 per cent) said they didn’t enjoy the online study experience as much as an in-person equivalent, and 41 per cent thought it was lower quality than if it had been delivered in-person.

Given the scenario of their institution announcing that all teaching would be delivered online (similar to what occurred on many campuses at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic), nearly three-fifths of surveyed students (58 per cent) said they would be disappointed.

Difficulty socialising and making friends, trouble accessing university facilities, including labs, and lack of field trips were also downsides of online learning, according to students. Half of students felt that their chance to build a professional network at university would suffer because of online learning.

However, when it came to equipping them with the skills necessary for their career, 46 per cent of students agreed that online learning provided that, a result that might suggest that they gained or sharpened the digital skills needed to excel in a modern workplace while learning online.

Benefits of online learning vs classroom learning, according to the THE Student Pulse panel

- Flexibility of the schedule

- Working at your own pace

- Watching lectures back on demand

- Career skills development

The most important factors of a university’s location, according to the THE Student Pulse panel respondents

- Access to educational facilities and institutions (libraries, laboratories, other universities and so on) (69 per cent)

- Safety of the location (55 per cent)

- Job opportunities in the local area (55 per cent)

Discover the University of Liverpools' online postgraduate courses

Register free and enjoy extra benefits

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Online and face‐to‐face learning: Evidence from students’ performance during the Covid‐19 pandemic

Carolyn chisadza.

1 Department of Economics, University of Pretoria, Hatfield South Africa

Matthew Clance

Thulani mthembu.

2 Department of Education Innovation, University of Pretoria, Hatfield South Africa

Nicky Nicholls

Eleni yitbarek.

This study investigates the factors that predict students' performance after transitioning from face‐to‐face to online learning as a result of the Covid‐19 pandemic. It uses students' responses from survey questions and the difference in the average assessment grades between pre‐lockdown and post‐lockdown at a South African university. We find that students' performance was positively associated with good wifi access, relative to using mobile internet data. We also observe lower academic performance for students who found transitioning to online difficult and who expressed a preference for self‐study (i.e. reading through class slides and notes) over assisted study (i.e. joining live lectures or watching recorded lectures). The findings suggest that improving digital infrastructure and reducing the cost of internet access may be necessary for mitigating the impact of the Covid‐19 pandemic on education outcomes.

1. INTRODUCTION

The Covid‐19 pandemic has been a wake‐up call to many countries regarding their capacity to cater for mass online education. This situation has been further complicated in developing countries, such as South Africa, who lack the digital infrastructure for the majority of the population. The extended lockdown in South Africa saw most of the universities with mainly in‐person teaching scrambling to source hardware (e.g. laptops, internet access), software (e.g. Microsoft packages, data analysis packages) and internet data for disadvantaged students in order for the semester to recommence. Not only has the pandemic revealed the already stark inequality within the tertiary student population, but it has also revealed that high internet data costs in South Africa may perpetuate this inequality, making online education relatively inaccessible for disadvantaged students. 1

The lockdown in South Africa made it possible to investigate the changes in second‐year students' performance in the Economics department at the University of Pretoria. In particular, we are interested in assessing what factors predict changes in students' performance after transitioning from face‐to‐face (F2F) to online learning. Our main objectives in answering this study question are to establish what study materials the students were able to access (i.e. slides, recordings, or live sessions) and how students got access to these materials (i.e. the infrastructure they used).

The benefits of education on economic development are well established in the literature (Gyimah‐Brempong, 2011 ), ranging from health awareness (Glick et al., 2009 ), improved technological innovations, to increased capacity development and employment opportunities for the youth (Anyanwu, 2013 ; Emediegwu, 2021 ). One of the ways in which inequality is perpetuated in South Africa, and Africa as a whole, is through access to education (Anyanwu, 2016 ; Coetzee, 2014 ; Tchamyou et al., 2019 ); therefore, understanding the obstacles that students face in transitioning to online learning can be helpful in ensuring more equal access to education.

Using students' responses from survey questions and the difference in the average grades between pre‐lockdown and post‐lockdown, our findings indicate that students' performance in the online setting was positively associated with better internet access. Accessing assisted study material, such as narrated slides or recordings of the online lectures, also helped students. We also find lower academic performance for students who reported finding transitioning to online difficult and for those who expressed a preference for self‐study (i.e. reading through class slides and notes) over assisted study (i.e. joining live lectures or watching recorded lectures). The average grades between pre‐lockdown and post‐lockdown were about two points and three points lower for those who reported transitioning to online teaching difficult and for those who indicated a preference for self‐study, respectively. The findings suggest that improving the quality of internet infrastructure and providing assisted learning can be beneficial in reducing the adverse effects of the Covid‐19 pandemic on learning outcomes.

Our study contributes to the literature by examining the changes in the online (post‐lockdown) performance of students and their F2F (pre‐lockdown) performance. This approach differs from previous studies that, in most cases, use between‐subject designs where one group of students following online learning is compared to a different group of students attending F2F lectures (Almatra et al., 2015 ; Brown & Liedholm, 2002 ). This approach has a limitation in that that there may be unobserved characteristics unique to students choosing online learning that differ from those choosing F2F lectures. Our approach avoids this issue because we use a within‐subject design: we compare the performance of the same students who followed F2F learning Before lockdown and moved to online learning during lockdown due to the Covid‐19 pandemic. Moreover, the study contributes to the limited literature that compares F2F and online learning in developing countries.

Several studies that have also compared the effectiveness of online learning and F2F classes encounter methodological weaknesses, such as small samples, not controlling for demographic characteristics, and substantial differences in course materials and assessments between online and F2F contexts. To address these shortcomings, our study is based on a relatively large sample of students and includes demographic characteristics such as age, gender and perceived family income classification. The lecturer and course materials also remained similar in the online and F2F contexts. A significant proportion of our students indicated that they never had online learning experience before. Less than 20% of the students in the sample had previous experience with online learning. This highlights the fact that online education is still relatively new to most students in our sample.

Given the global experience of the fourth industrial revolution (4IR), 2 with rapidly accelerating technological progress, South Africa needs to be prepared for the possibility of online learning becoming the new norm in the education system. To this end, policymakers may consider engaging with various organizations (schools, universities, colleges, private sector, and research facilities) To adopt interventions that may facilitate the transition to online learning, while at the same time ensuring fair access to education for all students across different income levels. 3

1.1. Related literature

Online learning is a form of distance education which mainly involves internet‐based education where courses are offered synchronously (i.e. live sessions online) and/or asynchronously (i.e. students access course materials online in their own time, which is associated with the more traditional distance education). On the other hand, traditional F2F learning is real time or synchronous learning. In a physical classroom, instructors engage with the students in real time, while in the online format instructors can offer real time lectures through learning management systems (e.g. Blackboard Collaborate), or record the lectures for the students to watch later. Purely online courses are offered entirely over the internet, while blended learning combines traditional F2F classes with learning over the internet, and learning supported by other technologies (Nguyen, 2015 ).

Moreover, designing online courses requires several considerations. For example, the quality of the learning environment, the ease of using the learning platform, the learning outcomes to be achieved, instructor support to assist and motivate students to engage with the course material, peer interaction, class participation, type of assessments (Paechter & Maier, 2010 ), not to mention training of the instructor in adopting and introducing new teaching methods online (Lundberg et al., 2008 ). In online learning, instructors are more facilitators of learning. On the other hand, traditional F2F classes are structured in such a way that the instructor delivers knowledge, is better able to gauge understanding and interest of students, can engage in class activities, and can provide immediate feedback on clarifying questions during the class. Additionally, the designing of traditional F2F courses can be less time consuming for instructors compared to online courses (Navarro, 2000 ).

Online learning is also particularly suited for nontraditional students who require flexibility due to work or family commitments that are not usually associated with the undergraduate student population (Arias et al., 2018 ). Initially the nontraditional student belonged to the older adult age group, but with blended learning becoming more commonplace in high schools, colleges and universities, online learning has begun to traverse a wider range of age groups. However, traditional F2F classes are still more beneficial for learners that are not so self‐sufficient and lack discipline in working through the class material in the required time frame (Arias et al., 2018 ).

For the purpose of this literature review, both pure online and blended learning are considered to be online learning because much of the evidence in the literature compares these two types against the traditional F2F learning. The debate in the literature surrounding online learning versus F2F teaching continues to be a contentious one. A review of the literature reveals mixed findings when comparing the efficacy of online learning on student performance in relation to the traditional F2F medium of instruction (Lundberg et al., 2008 ; Nguyen, 2015 ). A number of studies conducted Before the 2000s find what is known today in the empirical literature as the “No Significant Difference” phenomenon (Russell & International Distance Education Certificate Center (IDECC), 1999 ). The seminal work from Russell and IDECC ( 1999 ) involved over 350 comparative studies on online/distance learning versus F2F learning, dating back to 1928. The author finds no significant difference overall between online and traditional F2F classroom education outcomes. Subsequent studies that followed find similar “no significant difference” outcomes (Arbaugh, 2000 ; Fallah & Ubell, 2000 ; Freeman & Capper, 1999 ; Johnson et al., 2000 ; Neuhauser, 2002 ). While Bernard et al. ( 2004 ) also find that overall there is no significant difference in achievement between online education and F2F education, the study does find significant heterogeneity in student performance for different activities. The findings show that students in F2F classes outperform the students participating in synchronous online classes (i.e. classes that require online students to participate in live sessions at specific times). However, asynchronous online classes (i.e. students access class materials at their own time online) outperform F2F classes.

More recent studies find significant results for online learning outcomes in relation to F2F outcomes. On the one hand, Shachar and Yoram ( 2003 ) and Shachar and Neumann ( 2010 ) conduct a meta‐analysis of studies from 1990 to 2009 and find that in 70% of the cases, students taking courses by online education outperformed students in traditionally instructed courses (i.e. F2F lectures). In addition, Navarro and Shoemaker ( 2000 ) observe that learning outcomes for online learners are as effective as or better than outcomes for F2F learners, regardless of background characteristics. In a study on computer science students, Dutton et al. ( 2002 ) find online students perform significantly better compared to the students who take the same course on campus. A meta‐analysis conducted by the US Department of Education finds that students who took all or part of their course online performed better, on average, than those taking the same course through traditional F2F instructions. The report also finds that the effect sizes are larger for studies in which the online learning was collaborative or instructor‐driven than in those studies where online learners worked independently (Means et al., 2010 ).

On the other hand, evidence by Brown and Liedholm ( 2002 ) based on test scores from macroeconomics students in the United States suggest that F2F students tend to outperform online students. These findings are supported by Coates et al. ( 2004 ) who base their study on macroeconomics students in the United States, and Xu and Jaggars ( 2014 ) who find negative effects for online students using a data set of about 500,000 courses taken by over 40,000 students in Washington. Furthermore, Almatra et al. ( 2015 ) compare overall course grades between online and F2F students for a Telecommunications course and find that F2F students significantly outperform online learning students. In an experimental study where students are randomly assigned to attend live lectures versus watching the same lectures online, Figlio et al. ( 2013 ) observe some evidence that the traditional format has a positive effect compared to online format. Interestingly, Callister and Love ( 2016 ) specifically compare the learning outcomes of online versus F2F skills‐based courses and find that F2F learners earned better outcomes than online learners even when using the same technology. This study highlights that some of the inconsistencies that we find in the results comparing online to F2F learning might be influenced by the nature of the course: theory‐based courses might be less impacted by in‐person interaction than skills‐based courses.

The fact that the reviewed studies on the effects of F2F versus online learning on student performance have been mainly focused in developed countries indicates the dearth of similar studies being conducted in developing countries. This gap in the literature may also highlight a salient point: online learning is still relatively underexplored in developing countries. The lockdown in South Africa therefore provides us with an opportunity to contribute to the existing literature from a developing country context.

2. CONTEXT OF STUDY

South Africa went into national lockdown in March 2020 due to the Covid‐19 pandemic. Like most universities in the country, the first semester for undergraduate courses at the University of Pretoria had already been running since the start of the academic year in February. Before the pandemic, a number of F2F lectures and assessments had already been conducted in most courses. The nationwide lockdown forced the university, which was mainly in‐person teaching, to move to full online learning for the remainder of the semester. This forced shift from F2F teaching to online learning allows us to investigate the changes in students' performance.

Before lockdown, classes were conducted on campus. During lockdown, these live classes were moved to an online platform, Blackboard Collaborate, which could be accessed by all registered students on the university intranet (“ClickUP”). However, these live online lectures involve substantial internet data costs for students. To ensure access to course content for those students who were unable to attend the live online lectures due to poor internet connections or internet data costs, several options for accessing course content were made available. These options included prerecorded narrated slides (which required less usage of internet data), recordings of the live online lectures, PowerPoint slides with explanatory notes and standard PDF lecture slides.

At the same time, the university managed to procure and loan out laptops to a number of disadvantaged students, and negotiated with major mobile internet data providers in the country for students to have free access to study material through the university's “connect” website (also referred to as the zero‐rated website). However, this free access excluded some video content and live online lectures (see Table 1 ). The university also provided between 10 and 20 gigabytes of mobile internet data per month, depending on the network provider, sent to students' mobile phones to assist with internet data costs.

Sites available on zero‐rated website

Note : The table summarizes the sites that were available on the zero‐rated website and those that incurred data costs.

High data costs continue to be a contentious issue in Africa where average incomes are low. Gilbert ( 2019 ) reports that South Africa ranked 16th of the 45 countries researched in terms of the most expensive internet data in Africa, at US$6.81 per gigabyte, in comparison to other Southern African countries such as Mozambique (US$1.97), Zambia (US$2.70), and Lesotho (US$4.09). Internet data prices have also been called into question in South Africa after the Competition Commission published a report from its Data Services Market Inquiry calling the country's internet data pricing “excessive” (Gilbert, 2019 ).

3. EMPIRICAL APPROACH

We use a sample of 395 s‐year students taking a macroeconomics module in the Economics department to compare the effects of F2F and online learning on students' performance using a range of assessments. The module was an introduction to the application of theoretical economic concepts. The content was both theory‐based (developing economic growth models using concepts and equations) and skill‐based (application involving the collection of data from online data sources and analyzing the data using statistical software). Both individual and group assignments formed part of the assessments. Before the end of the semester, during lockdown in June 2020, we asked the students to complete a survey with questions related to the transition from F2F to online learning and the difficulties that they may have faced. For example, we asked the students: (i) how easy or difficult they found the transition from F2F to online lectures; (ii) what internet options were available to them and which they used the most to access the online prescribed work; (iii) what format of content they accessed and which they preferred the most (i.e. self‐study material in the form of PDF and PowerPoint slides with notes vs. assisted study with narrated slides and lecture recordings); (iv) what difficulties they faced accessing the live online lectures, to name a few. Figure 1 summarizes the key survey questions that we asked the students regarding their transition from F2F to online learning.

Summary of survey data

Before the lockdown, the students had already attended several F2F classes and completed three assessments. We are therefore able to create a dependent variable that is comprised of the average grades of three assignments taken before lockdown and the average grades of three assignments taken after the start of the lockdown for each student. Specifically, we use the difference between the post‐ and pre‐lockdown average grades as the dependent variable. However, the number of student observations dropped to 275 due to some students missing one or more of the assessments. The lecturer, content and format of the assessments remain similar across the module. We estimate the following equation using ordinary least squares (OLS) with robust standard errors:

where Y i is the student's performance measured by the difference between the post and pre‐lockdown average grades. B represents the vector of determinants that measure the difficulty faced by students to transition from F2F to online learning. This vector includes access to the internet, study material preferred, quality of the online live lecture sessions and pre‐lockdown class attendance. X is the vector of student demographic controls such as race, gender and an indicator if the student's perceived family income is below average. The ε i is unobserved student characteristics.

4. ANALYSIS

4.1. descriptive statistics.

Table 2 gives an overview of the sample of students. We find that among the black students, a higher proportion of students reported finding the transition to online learning more difficult. On the other hand, more white students reported finding the transition moderately easy, as did the other races. According to Coetzee ( 2014 ), the quality of schools can vary significantly between higher income and lower‐income areas, with black South Africans far more likely to live in lower‐income areas with lower quality schools than white South Africans. As such, these differences in quality of education from secondary schooling can persist at tertiary level. Furthermore, persistent income inequality between races in South Africa likely means that many poorer black students might not be able to afford wifi connections or large internet data bundles which can make the transition difficult for black students compared to their white counterparts.

Descriptive statistics

Notes : The transition difficulty variable was ordered 1: Very Easy; 2: Moderately Easy; 3: Difficult; and 4: Impossible. Since we have few responses to the extremes, we combined Very Easy and Moderately as well as Difficult and Impossible to make the table easier to read. The table with a full breakdown is available upon request.

A higher proportion of students reported that wifi access made the transition to online learning moderately easy. However, relatively more students reported that mobile internet data and accessing the zero‐rated website made the transition difficult. Surprisingly, not many students made use of the zero‐rated website which was freely available. Figure 2 shows that students who reported difficulty transitioning to online learning did not perform as well in online learning versus F2F when compared to those that found it less difficult to transition.

Transition from F2F to online learning.

Notes : This graph shows the students' responses to the question “How easy did you find the transition from face‐to‐face lectures to online lectures?” in relation to the outcome variable for performance

In Figure 3 , the kernel density shows that students who had access to wifi performed better than those who used mobile internet data or the zero‐rated data.

Access to online learning.

Notes : This graph shows the students' responses to the question “What do you currently use the most to access most of your prescribed work?” in relation to the outcome variable for performance

The regression results are reported in Table 3 . We find that the change in students' performance from F2F to online is negatively associated with the difficulty they faced in transitioning from F2F to online learning. According to student survey responses, factors contributing to difficulty in transitioning included poor internet access, high internet data costs and lack of equipment such as laptops or tablets to access the study materials on the university website. Students who had access to wifi (i.e. fixed wireless broadband, Asymmetric Digital Subscriber Line (ADSL) or optic fiber) performed significantly better, with on average 4.5 points higher grade, in relation to students that had to use mobile internet data (i.e. personal mobile internet data, wifi at home using mobile internet data, or hotspot using mobile internet data) or the zero‐rated website to access the study materials. The insignificant results for the zero‐rated website are surprising given that the website was freely available and did not incur any internet data costs. However, most students in this sample complained that the internet connection on the zero‐rated website was slow, especially in uploading assignments. They also complained about being disconnected when they were in the middle of an assessment. This may have discouraged some students from making use of the zero‐rated website.

Results: Predictors for student performance using the difference on average assessment grades between pre‐ and post‐lockdown

Coefficients reported. Robust standard errors in parentheses.

∗∗∗ p < .01.

Students who expressed a preference for self‐study approaches (i.e. reading PDF slides or PowerPoint slides with explanatory notes) did not perform as well, on average, as students who preferred assisted study (i.e. listening to recorded narrated slides or lecture recordings). This result is in line with Means et al. ( 2010 ), where student performance was better for online learning that was collaborative or instructor‐driven than in cases where online learners worked independently. Interestingly, we also observe that the performance of students who often attended in‐person classes before the lockdown decreased. Perhaps these students found the F2F lectures particularly helpful in mastering the course material. From the survey responses, we find that a significant proportion of the students (about 70%) preferred F2F to online lectures. This preference for F2F lectures may also be linked to the factors contributing to the difficulty some students faced in transitioning to online learning.

We find that the performance of low‐income students decreased post‐lockdown, which highlights another potential challenge to transitioning to online learning. The picture and sound quality of the live online lectures also contributed to lower performance. Although this result is not statistically significant, it is worth noting as the implications are linked to the quality of infrastructure currently available for students to access online learning. We find no significant effects of race on changes in students' performance, though males appeared to struggle more with the shift to online teaching than females.

For the robustness check in Table 4 , we consider the average grades of the three assignments taken after the start of the lockdown as a dependent variable (i.e. the post‐lockdown average grades for each student). We then include the pre‐lockdown average grades as an explanatory variable. The findings and overall conclusions in Table 4 are consistent with the previous results.

Robustness check: Predictors for student performance using the average assessment grades for post‐lockdown

As a further robustness check in Table 5 , we create a panel for each student across the six assignment grades so we can control for individual heterogeneity. We create a post‐lockdown binary variable that takes the value of 1 for the lockdown period and 0 otherwise. We interact the post‐lockdown dummy variable with a measure for transition difficulty and internet access. The internet access variable is an indicator variable for mobile internet data, wifi, or zero‐rated access to class materials. The variable wifi is a binary variable taking the value of 1 if the student has access to wifi and 0 otherwise. The zero‐rated variable is a binary variable taking the value of 1 if the student used the university's free portal access and 0 otherwise. We also include assignment and student fixed effects. The results in Table 5 remain consistent with our previous findings that students who had wifi access performed significantly better than their peers.

Interaction model

Notes : Coefficients reported. Robust standard errors in parentheses. The dependent variable is the assessment grades for each student on each assignment. The number of observations include the pre‐post number of assessments multiplied by the number of students.

6. CONCLUSION

The Covid‐19 pandemic left many education institutions with no option but to transition to online learning. The University of Pretoria was no exception. We examine the effect of transitioning to online learning on the academic performance of second‐year economic students. We use assessment results from F2F lectures before lockdown, and online lectures post lockdown for the same group of students, together with responses from survey questions. We find that the main contributor to lower academic performance in the online setting was poor internet access, which made transitioning to online learning more difficult. In addition, opting to self‐study (read notes instead of joining online classes and/or watching recordings) did not help the students in their performance.

The implications of the results highlight the need for improved quality of internet infrastructure with affordable internet data pricing. Despite the university's best efforts not to leave any student behind with the zero‐rated website and free monthly internet data, the inequality dynamics in the country are such that invariably some students were negatively affected by this transition, not because the student was struggling academically, but because of inaccessibility of internet (wifi). While the zero‐rated website is a good collaborative initiative between universities and network providers, the infrastructure is not sufficient to accommodate mass students accessing it simultaneously.

This study's findings may highlight some shortcomings in the academic sector that need to be addressed by both the public and private sectors. There is potential for an increase in the digital divide gap resulting from the inequitable distribution of digital infrastructure. This may lead to reinforcement of current inequalities in accessing higher education in the long term. To prepare the country for online learning, some considerations might need to be made to make internet data tariffs more affordable and internet accessible to all. We hope that this study's findings will provide a platform (or will at least start the conversation for taking remedial action) for policy engagements in this regard.

We are aware of some limitations presented by our study. The sample we have at hand makes it difficult to extrapolate our findings to either all students at the University of Pretoria or other higher education students in South Africa. Despite this limitation, our findings highlight the negative effect of the digital divide on students' educational outcomes in the country. The transition to online learning and the high internet data costs in South Africa can also have adverse learning outcomes for low‐income students. With higher education institutions, such as the University of Pretoria, integrating online teaching to overcome the effect of the Covid‐19 pandemic, access to stable internet is vital for students' academic success.

It is also important to note that the data we have at hand does not allow us to isolate wifi's causal effect on students' performance post‐lockdown due to two main reasons. First, wifi access is not randomly assigned; for instance, there is a high chance that students with better‐off family backgrounds might have better access to wifi and other supplementary infrastructure than their poor counterparts. Second, due to the university's data access policy and consent, we could not merge the data at hand with the student's previous year's performance. Therefore, future research might involve examining the importance of these elements to document the causal impact of access to wifi on students' educational outcomes in the country.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge the helpful comments received from the editor, the anonymous reviewers, and Elizabeth Asiedu.

Chisadza, C. , Clance, M. , Mthembu, T. , Nicholls, N. , & Yitbarek, E. (2021). Online and face‐to‐face learning: Evidence from students’ performance during the Covid‐19 pandemic . Afr Dev Rev , 33 , S114–S125. 10.1111/afdr.12520 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

1 https://mybroadband.co.za/news/cellular/309693-mobile-data-prices-south-africa-vs-the-world.html .

2 The 4IR is currently characterized by increased use of new technologies, such as advanced wireless technologies, artificial intelligence, cloud computing, robotics, among others. This era has also facilitated the use of different online learning platforms ( https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-fourth-industrialrevolution-and-digitization-will-transform-africa-into-a-global-powerhouse/ ).

3 Note that we control for income, but it is plausible to assume other unobservable factors such as parental preference and parenting style might also affect access to the internet of students.

- Almatra, O. , Johri, A. , Nagappan, K. , & Modanlu, A. (2015). An empirical study of face‐to‐face and distance learning sections of a core telecommunication course (Conference Proceedings Paper No. 12944). 122nd ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Seattle, Washington State.

- Anyanwu, J. C. (2013). Characteristics and macroeconomic determinants of youth employment in Africa . African Development Review , 25 ( 2 ), 107–129. [ Google Scholar ]

- Anyanwu, J. C. (2016). Accounting for gender equality in secondary school enrolment in Africa: Accounting for gender equality in secondary school enrolment . African Development Review , 28 ( 2 ), 170–191. [ Google Scholar ]

- Arbaugh, J. (2000). Virtual classroom versus physical classroom: An exploratory study of class discussion patterns and student learning in an asynchronous internet‐based MBA course . Journal of Management Education , 24 ( 2 ), 213–233. [ Google Scholar ]

- Arias, J. J. , Swinton, J. , & Anderson, K. (2018). On‐line vs. face‐to‐face: A comparison of student outcomes with random assignment . e‐Journal of Business Education and Scholarship of Teaching, , 12 ( 2 ), 1–23. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bernard, R. M. , Abrami, P. C. , Lou, Y. , Borokhovski, E. , Wade, A. , Wozney, L. , Wallet, P. A. , Fiset, M. , & Huang, B. (2004). How does distance education compare with classroom instruction? A meta‐analysis of the empirical literature . Review of Educational Research , 74 ( 3 ), 379–439. [ Google Scholar ]

- Brown, B. , & Liedholm, C. (2002). Can web courses replace the classroom in principles of microeconomics? American Economic Review , 92 ( 2 ), 444–448. [ Google Scholar ]

- Callister, R. R. , & Love, M. S. (2016). A comparison of learning outcomes in skills‐based courses: Online versus face‐to‐face formats . Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education , 14 ( 2 ), 243–256. [ Google Scholar ]

- Coates, D. , Humphreys, B. R. , Kane, J. , & Vachris, M. A. (2004). “No significant distance” between face‐to‐face and online instruction: Evidence from principles of economics . Economics of Education Review , 23 ( 5 ), 533–546. [ Google Scholar ]

- Coetzee, M. (2014). School quality and the performance of disadvantaged learners in South Africa (Working Paper No. 22). University of Stellenbosch Economics Department, Stellenbosch

- Dutton, J. , Dutton, M. , & Perry, J. (2002). How do online students differ from lecture students? Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks , 6 ( 1 ), 1–20. [ Google Scholar ]

- Emediegwu, L. (2021). Does educational investment enhance capacity development for Nigerian youths? An autoregressive distributed lag approach . African Development Review , 32 ( S1 ), S45–S53. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fallah, M. H. , & Ubell, R. (2000). Blind scores in a graduate test. Conventional compared with web‐based outcomes . ALN Magazine , 4 ( 2 ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Figlio, D. , Rush, M. , & Yin, L. (2013). Is it live or is it internet? Experimental estimates of the effects of online instruction on student learning . Journal of Labor Economics , 31 ( 4 ), 763–784. [ Google Scholar ]

- Freeman, M. A. , & Capper, J. M. (1999). Exploiting the web for education: An anonymous asynchronous role simulation . Australasian Journal of Educational Technology , 15 ( 1 ), 95–116. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gilbert, P. (2019). The most expensive data prices in Africa . Connecting Africa. https://www.connectingafrica.com/author.asp?section_id=761%26doc_id=756372

- Glick, P. , Randriamamonjy, J. , & Sahn, D. (2009). Determinants of HIV knowledge and condom use among women in Madagascar: An analysis using matched household and community data . African Development Review , 21 ( 1 ), 147–179. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gyimah‐Brempong, K. (2011). Education and economic development in Africa . African Development Review , 23 ( 2 ), 219–236. [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson, S. , Aragon, S. , Shaik, N. , & Palma‐Rivas, N. (2000). Comparative analysis of learner satisfaction and learning outcomes in online and face‐to‐face learning environments . Journal of Interactive Learning Research , 11 ( 1 ), 29–49. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lundberg, J. , Merino, D. , & Dahmani, M. (2008). Do online students perform better than face‐to‐face students? Reflections and a short review of some empirical findings . Revista de Universidad y Sociedad del Conocimiento , 5 ( 1 ), 35–44. [ Google Scholar ]

- Means, B. , Toyama, Y. , Murphy, R. , Bakia, M. , & Jones, K. (2010). Evaluation of evidence‐based practices in online learning: A meta‐analysis and review of online learning studies (Report No. ed‐04‐co‐0040 task 0006). U.S. Department of Education, Office of Planning, Evaluation, and Policy Development, Washington DC.

- Navarro, P. (2000). Economics in the cyber‐classroom . Journal of Economic Perspectives , 14 ( 2 ), 119–132. [ Google Scholar ]

- Navarro, P. , & Shoemaker, J. (2000). Performance and perceptions of distance learners in cyberspace . American Journal of Distance Education , 14 ( 2 ), 15–35. [ Google Scholar ]

- Neuhauser, C. (2002). Learning style and effectiveness of online and face‐to‐face instruction . American Journal of Distance Education , 16 ( 2 ), 99–113. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nguyen, T. (2015). The effectiveness of online learning: Beyond no significant difference and future horizons . MERLOT Journal of Online Teaching and Learning , 11 ( 2 ), 309–319. [ Google Scholar ]

- Paechter, M. , & Maier, B. (2010). Online or face‐to‐face? Students' experiences and preferences in e‐learning . Internet and Higher Education , 13 ( 4 ), 292–297. [ Google Scholar ]

- Russell, T. L. , & International Distance Education Certificate Center (IDECC) (1999). The no significant difference phenomenon: A comparative research annotated bibliography on technology for distance education: As reported in 355 research reports, summaries and papers . North Carolina State University. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shachar, M. , & Neumann, Y. (2010). Twenty years of research on the academic performance differences between traditional and distance learning: Summative meta‐analysis and trend examination . MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching , 6 ( 2 ), 318–334. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shachar, M. , & Yoram, N. (2003). Differences between traditional and distance education academic performances: A meta‐analytic approach . International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning , 4 ( 2 ), 1–20. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tchamyou, V. S. , Asongu, S. , & Odhiambo, N. (2019). The role of ICT in modulating the effect of education and lifelong learning on income inequality and economic growth in Africa . African Development Review , 31 ( 3 ), 261–274. [ Google Scholar ]

- Xu, D. , & Jaggars, S. S. (2014). Performance gaps between online and face‐to‐face courses: Differences across types of students and academic subject areas . The Journal of Higher Education , 85 ( 5 ), 633–659. [ Google Scholar ]

- Essay Samples

- College Essay

- Writing Tools

- Writing guide

Creative samples from the experts

↑ Return to Essay Samples

Argumentative Essay: Online Learning and Educational Access

Conventional learning is evolving with the help of computers and online technology. New ways of learning are now available, and improved access is one of the most important benefits available. People all around the world are experiencing improved mobility as a result of the freedom and potential that online learning provides, and as academic institutions and learning organisations adopt online learning technologies and remote-access learning, formal academic education is becoming increasingly legitimate. This essay argues the contemporary benefits of online learning, and that these benefits significantly outweigh the issues, challenges and disadvantages of online learning.

Online learning is giving people new choices and newfound flexibility with their personal learning and development. Whereas before, formal academic qualifications could only be gained by participating in a full time course on site, the internet has allowed institutions to expand their reach and offer recognized courses on a contact-partial, or totally virtual, basis. Institutions can do so with relatively few extra resources, and for paid courses this constitutes excellent value, and the student benefits with greater educational access and greater flexibility to learn and get qualified even when there lots of other personal commitments to deal with.

Flexibility is certainly one of the most important benefits, but just as important is educational access. On top of the internet’s widespread presence in developed countries, the internet is becoming increasingly available in newly developed and developing countries. Even without considering the general informational exposure that the internet delivers, online academic courses and learning initiatives are becoming more aware of the needs of people from disadvantaged backgrounds, and this means that people from such backgrounds are in a much better position to learn and progress than they used to be.

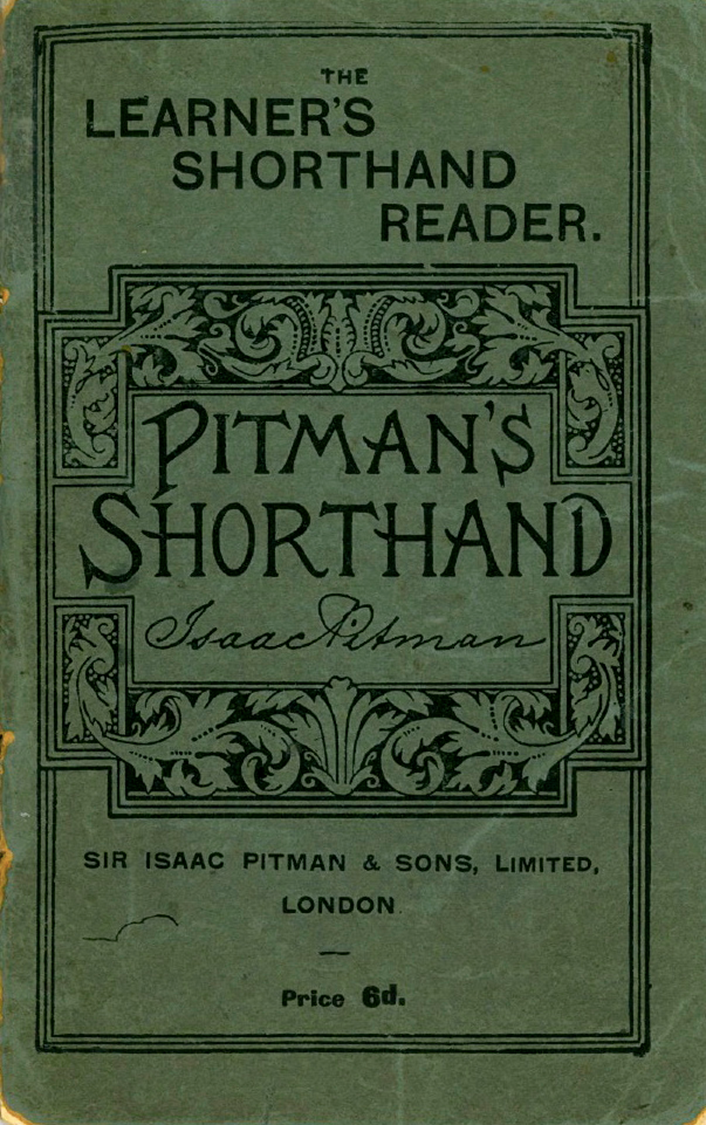

The biggest argument that raises doubt over online learning is the quality of online courses in comparison to conventional courses. Are such online courses good enough for employers to take notice? The second biggest argument is the current reality that faces many people from disadvantaged backgrounds, despite the improvements made in this area in recent years – they do not have the level of basic access needed to benefit from online learning. In fact, there are numerous sources of evidence that claim disadvantaged students are not receiving anywhere near the sort of benefits that online learning institutions and promoters are trying to instigate. Currently there are many organisations, campaigns and initiatives that are working to expand access to higher education. With such high participation, it can be argued that it is only a matter of time before the benefits are truly realised, but what about the global online infrastructure?

There is another argument that is very difficult to dispel, and that is the response of different types of students to the online learning paradigm. Evidence shows that there are certain groups of students that benefit from college distance learning much more than other groups. In essence, students must be highly motivated and highly disciplined if they are to learn effectively in their own private environment.

Follow Us on Social Media

Get more free essays

Send via email

Most useful resources for students:.

- Free Essays Download

- Writing Tools List

- Proofreading Services

- Universities Rating

Contributors Bio

Find more useful services for students

Free plagiarism check, professional editing, online tutoring, free grammar check.

How Effective Is Online Learning? What the Research Does and Doesn’t Tell Us

- Share article

Editor’s Note: This is part of a series on the practical takeaways from research.

The times have dictated school closings and the rapid expansion of online education. Can online lessons replace in-school time?

Clearly online time cannot provide many of the informal social interactions students have at school, but how will online courses do in terms of moving student learning forward? Research to date gives us some clues and also points us to what we could be doing to support students who are most likely to struggle in the online setting.

The use of virtual courses among K-12 students has grown rapidly in recent years. Florida, for example, requires all high school students to take at least one online course. Online learning can take a number of different forms. Often people think of Massive Open Online Courses, or MOOCs, where thousands of students watch a video online and fill out questionnaires or take exams based on those lectures.

In the online setting, students may have more distractions and less oversight, which can reduce their motivation.

Most online courses, however, particularly those serving K-12 students, have a format much more similar to in-person courses. The teacher helps to run virtual discussion among the students, assigns homework, and follows up with individual students. Sometimes these courses are synchronous (teachers and students all meet at the same time) and sometimes they are asynchronous (non-concurrent). In both cases, the teacher is supposed to provide opportunities for students to engage thoughtfully with subject matter, and students, in most cases, are required to interact with each other virtually.

Coronavirus and Schools

Online courses provide opportunities for students. Students in a school that doesn’t offer statistics classes may be able to learn statistics with virtual lessons. If students fail algebra, they may be able to catch up during evenings or summer using online classes, and not disrupt their math trajectory at school. So, almost certainly, online classes sometimes benefit students.

In comparisons of online and in-person classes, however, online classes aren’t as effective as in-person classes for most students. Only a little research has assessed the effects of online lessons for elementary and high school students, and even less has used the “gold standard” method of comparing the results for students assigned randomly to online or in-person courses. Jessica Heppen and colleagues at the American Institutes for Research and the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research randomly assigned students who had failed second semester Algebra I to either face-to-face or online credit recovery courses over the summer. Students’ credit-recovery success rates and algebra test scores were lower in the online setting. Students assigned to the online option also rated their class as more difficult than did their peers assigned to the face-to-face option.

Most of the research on online courses for K-12 students has used large-scale administrative data, looking at otherwise similar students in the two settings. One of these studies, by June Ahn of New York University and Andrew McEachin of the RAND Corp., examined Ohio charter schools; I did another with colleagues looking at Florida public school coursework. Both studies found evidence that online coursetaking was less effective.

About this series

This essay is the fifth in a series that aims to put the pieces of research together so that education decisionmakers can evaluate which policies and practices to implement.

The conveners of this project—Susanna Loeb, the director of Brown University’s Annenberg Institute for School Reform, and Harvard education professor Heather Hill—have received grant support from the Annenberg Institute for this series.

To suggest other topics for this series or join in the conversation, use #EdResearchtoPractice on Twitter.

Read the full series here .

It is not surprising that in-person courses are, on average, more effective. Being in person with teachers and other students creates social pressures and benefits that can help motivate students to engage. Some students do as well in online courses as in in-person courses, some may actually do better, but, on average, students do worse in the online setting, and this is particularly true for students with weaker academic backgrounds.

Students who struggle in in-person classes are likely to struggle even more online. While the research on virtual schools in K-12 education doesn’t address these differences directly, a study of college students that I worked on with Stanford colleagues found very little difference in learning for high-performing students in the online and in-person settings. On the other hand, lower performing students performed meaningfully worse in online courses than in in-person courses.

But just because students who struggle in in-person classes are even more likely to struggle online doesn’t mean that’s inevitable. Online teachers will need to consider the needs of less-engaged students and work to engage them. Online courses might be made to work for these students on average, even if they have not in the past.

Just like in brick-and-mortar classrooms, online courses need a strong curriculum and strong pedagogical practices. Teachers need to understand what students know and what they don’t know, as well as how to help them learn new material. What is different in the online setting is that students may have more distractions and less oversight, which can reduce their motivation. The teacher will need to set norms for engagement—such as requiring students to regularly ask questions and respond to their peers—that are different than the norms in the in-person setting.

Online courses are generally not as effective as in-person classes, but they are certainly better than no classes. A substantial research base developed by Karl Alexander at Johns Hopkins University and many others shows that students, especially students with fewer resources at home, learn less when they are not in school. Right now, virtual courses are allowing students to access lessons and exercises and interact with teachers in ways that would have been impossible if an epidemic had closed schools even a decade or two earlier. So we may be skeptical of online learning, but it is also time to embrace and improve it.

A version of this article appeared in the April 01, 2020 edition of Education Week as How Effective Is Online Learning?

Sign Up for EdWeek Tech Leader

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Search form

- Tools and Trends

Making Sense of Flexibility as A Defining Element of Online Learning

Sir John Daniel

Contact north | contact north research associate.

Contemporary developments in online learning have their origins in the technology of the industrial revolution, when new methods and machines were used to create better products inexpensively at scale. Now technology has also broken the hold of the 'iron triangle' that prevented earlier generations from enjoying wide access to education of quality at low cost. First correspondence education and then multi-media open and distance learning (ODL) brought flexible learning to millions. Today online technologies have brought further flexibility to post-secondary education on various dimensions. Institutions should exploit these new flexibilities purposefully, focusing on opportunities to engage students more deeply in learning leading to useful outcomes.

Introduction