The White Album

47 pages • 1 hour read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Key Figures

Symbols & Motifs

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Summary and Study Guide

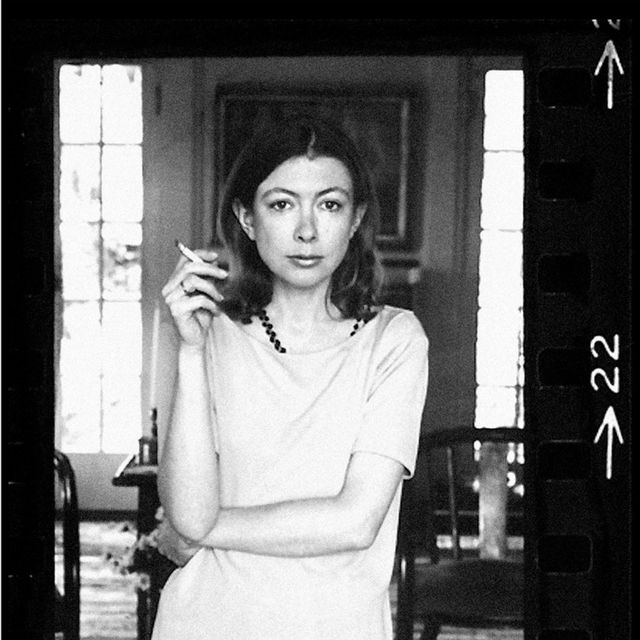

The White Album is a collection of essays by Joan Didion . The book was published in 1979, but most of the essays previously appeared independently in prominent magazines like Esquire and Life . The essays center on California life and popular culture. Didion was born in California and lived a large part of life on the West Coast, so she was acutely familiar with its nuances and narratives. As a prolific writer of multiple kinds of media—books, screenplays, and magazine articles—Didion was keenly aware of how entertainment industries and divergent cultures impact American identity and reality. The essays are an example of New Journalism—a literary movement that turns the journalist into a personality and the article into a story.

Didion was known for her chic, minimalist style , and in 2015, at 80, she starred in an ad campaign for the fashion brand Celine. Seven years later, she died. Aside from a captivating image, she left an array of acclaimed books, including the earlier essay collection Slouching Towards Bethlehem (1968), the novel Play It as It Lays (1970), and a memoir about her husband’s death, The Year of Magical Thinking (2005).

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,500+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 4,900+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

This guide uses the 2017 Open Road eBook edition of The White Album .

Content Warning : The source text contains a discussion of sexual assault .

The SuperSummary difference

- 8x more resources than SparkNotes and CliffsNotes combined

- Study Guides you won ' t find anywhere else

- 100+ new titles every month

Didion organizes the essays into five parts. The first, “The White Album,” which contains one essay of the same name (also the book’s title) alludes to the 1968 self-titled album by The Beatles, known as The White Album because the famed rock band used an all-white cover. Like the album’s discordant songs, the tone of Didion’s essay is edgy, jarring. In addition, some held that the album inspired the infamous Charles Manson and his followers to kill, and Didion’s essay describes her relationship with Manson follower Linda Kasabian, who testified against Manson in the court case about the murder of actress Sharon Tate. Didion begins with a now-famous declaration: “We tell ourselves stories in order to live” (8). She’s suspicious about stories and meanings; she favors impressions or images. She shares her observations on Kasabian, the Black Panthers, the rock group The Doors, and two murderous brothers. Additionally, she includes literary sketches of herself, describing how she rents a 28-room house in Hollywood, where she engages with celebrities and threatening strangers, and delving into her medical history and how she packs for trips.

In the second part, “California Republic,” Didion focuses on the individuals, institutions, and places that exemplify her idea of California. They include Protestant bishop James Pike, who published books, hosted a TV show, and remodeled a church using images of famous physicist Albert Einstein and the first Black Supreme Court member, Thurgood Marshall; Pentecostal preacher Elder Robert J. Theobold, who hears messages from God; and other people under various influences—bikers, people with gambling addictions, and an aspiring actress. She watches a TV man film Nancy Reagan, the wife of former California governor Ronald Reagan (who later served as a US president), and describes a Hollywood party where people view social problems as plots needing a hopeful resolution. In “Holy Water,” Didion visits the California State Water Project’s control center and shows how water moves throughout the state. In “Bureaucrats,” she examines the faulty logic behind the California Department of Transportation’s designating Diamond Lanes to encourage the use of buses and carpools on state highways. Likewise, California politics and controversies connect to essays on two controversial buildings: the governor’s residence built by Reagan and a $17 million museum to house the art and items of oil baron J. Paul Getty.

In the third set of essays, “Women,” Didion critiques the feminist movement—and prominent feminists—for arguing that women are invariably oppressed. She admits that sexist norms harm some women but notes that other women get along fine and holds that the outsized focus on oppression characterizes women as children instead of adults. Didion admires the tenacity of Doris Lessing’s fiction and how the artist Georgia O’Keeffe is unperturbed by what men think.

The fourth part, “Sojourns” details the places where Didion stays. To avoid divorce, Didion, her husband, and her daughter spend time in Honolulu. Later, she returns to Hawaii, visiting a graveyard for soldiers killed in the Vietnam War and documenting Schofield Barracks, an army base that James Jones featured in his World War II-era novel From Here to Eternity (1951). The next essay focuses on Hollywood, California: Didion examines the economics and power dynamics of the movie business. “In Bed” describes her thoughts about the migraines that regularly confine her to bed. “On the Road” spotlights the peculiar stress of a book tour with her 11-year-old daughter. She then explores shopping malls across the US. Next, Didion spends time in Bogotá, Columbia, where she finds a shopping mall, American movies, political intrigue, and an oppressive salt mine. The last essay in the section returns to the topic of water—Didion visits the Hoover Dam and contemplates its otherworldly magnetism.

In the book’s fifth part, “On the Morning After the Sixties,” Didion compares her generation’s distrust of activism and moral clarity with the revolutionary, righteous spirit of the 1960s. The concluding essay, “Quiet Days in Malibu,” begins calmly. Didion spends time with lifeguards and an orchid breeder, and she describes her communal Malibu neighborhood near a highway. However, the essay and book end dramatically, as a fire destroys the orchids and almost wipes out Didion’s former home.

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By Joan Didion

A Book of Common Prayer

Joan Didion

Blue Nights

Play It As It Lays

Slouching Towards Bethlehem

The Year of Magical Thinking

Featured Collections

Books About Art

View Collection

Books & Literature

Books on U.S. History

Journalism Reads

National Book Awards Winners & Finalists

National Book Critics Circle Award...

Politics & Government

Sexual Harassment & Violence

Trust & Doubt

Truth & Lies

Women's Studies

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

The White Album By Joan Didion

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

20 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

In collections.

Uploaded by Melograno83 on December 8, 2022

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

JOAN DIDION

The white album.

June 19, 1979

Publication Date:

FSG Classics

ABOUT THE BOOK

From a jailhouse visit to Black Panther Party cofounder Huey Newton to witnessing First Lady of California Nancy Reagan pretend to pick flowers for the benefit of news cameras, Didion captures the paranoia and absurdity of the era with her signature blend of irony and insight. She takes readers to the “giddily splendid” Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the cool mountains of Bogotá, and the Jordanian Desert, where Bishop James Pike went to walk in Jesus’s footsteps—and died not far from his rented Ford Cortina. She anatomizes the culture of shopping malls—“toy garden cities in which no one lives but everyone consumes”—and exposes the contradictions and compromises of the women’s movement. In the iconic title essay, she documents her uneasy state of mind during the years leading up to and following the Manson murders—a terrifying crime that, in her memory, surprised no one.

Written in “a voice like no other in contemporary journalism,” The White Album is a masterpiece of literary reportage and a fearless work of autobiography.

Purchase the Book

Didion manages to make the sorry stuff of troubled times (bike movies, for instance, and bishop james pike) as interesting and suggestive as the monuments that win her dazzled admiration (georgia o’keeffe, the hoover dam, the mountains around bogota)…a timely and elegant collection..

—The New Yorker

Read an Excerpt

We tell ourselves stories in order to live. The princess is caged in the consulate. The man with the candy will lead the children into the sea. The naked woman on the ledge outside the window on the sixteenth floor is a victim of accidie, or the naked woman is an exhibitionist, and it would be “interesting” to know which. We tell ourselves that it makes some difference whether the naked woman is about to commit a mortal sin or is about to register a political protest or is about to be, the Aristophanic view, snatched back to the human condition by the fireman in priest’s clothing just visible in the window behind her, the one smiling at the telephoto lens. We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the “ideas” with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.

Or at least we do for a while. I am talking here about a time when I began to doubt the premises of all the stories I had ever told myself, a common condition but one I found troubling. I suppose this period began around 1966 and continued until 1971. During those five years I appeared, on the face of it, a competent enough member of some community or another, a signer of contracts and Air Travel cards, a citizen: I wrote a couple of times a month for one magazine or another, published two books, worked on several motion pictures; participated in the paranoia of the time, in the raising of a small child, and in the entertainment of large numbers of people passing through my house; made gingham curtains for spare bedrooms, remembered to ask agents if any reduction of points would be pari passu with the financing studio, put lentils to soak on Saturday night for lentil soup on Sunday, made quarterly F.I.C.A. payments and renewed my driver’s license on time, missing on the written examination only the question about the financial responsibility of California drivers. It was a time of my life when I was frequently “named.” I was named godmother to children. I was named lecturer and panelist, colloquist and conferee. I was even named, in 1968, a Los Angeles Times “Woman of the Year,” along with Mrs. Ronald Reagan, the Olympic swimmer Debbie Meyer, and ten other California women who seemed to keep in touch and do good works. I did no good works but I tried to keep in touch. I was responsible. I recognized my name when I saw it. Once in a while I even answered letters addressed to me, not exactly upon receipt but eventually, particularly if the letters had come from strangers. “During my absence from the country these past eighteen months,” such replies would begin.

This was an adequate enough performance, as improvisations go. The only problem was that my entire education, everything I had ever been told or had told myself, insisted that the production was never meant to be improvised: I was supposed to have a script, and had mislaid it. I was supposed to hear cues, and no longer did. I was meant to know the plot, but all I knew was what I saw: flash pictures in variable sequence, images with no “meaning” beyond their temporary arrangement, not a movie but a cutting-room experience. In what would probably be the middle of my life I wanted still to believe in the narrative and in the narrative’s intelligibility, but to know that one could change the sense with every cut was to begin to perceive the experience as rather more electrical than ethical.

During this period I spent what were for me the usual proportions of time in Los Angeles and New York and Sacramento. I spent what seemed to many people I knew an eccentric amount of time in Honolulu, the particular aspect of which lent me the illusion that I could any minute order from room service a revisionist theory of my own history, garnished with a vanda orchid. I watched Robert Kennedy’s funeral on a verandah at the Royal Hawaiian Hotel in Honolulu, and also the first reports from My Lai. I reread all of George Orwell on the Royal Hawaiian Beach, and I also read, in the papers that came one day late from the mainland, the story of Betty Lansdown Fouquet, a 26-year-old woman with faded blond hair who put her five-year-old daughter out to die on the center divider of Interstate 5 some miles south of the last Bakersfield exit. The child, whose fingers had to be pried loose from the Cyclone fence when she was rescued twelve hours later by the California Highway Patrol, reported that she had run after the car carrying her mother and stepfather and brother and sister for “a long time.” Certain of these images did not fit into any narrative I knew.

BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR

joan didion books .

5 customer-loved finds for spring, including a fashion hack — starting at $7

- TODAY Plaza

- Share this —

- Watch Full Episodes

- Read With Jenna

- Inspirational

- Relationships

- TODAY Table

- Newsletters

- Start TODAY

- Shop TODAY Awards

- Citi Concert Series

- Listen All Day

Follow today

More Brands

- On The Show

Joan Didion’s best books, from essays to fiction

On Thursday, it was announced that prolific writer Joan Didion had died at the age of 87.

An executive at her publisher, Knopf, confirmed the author's death to TODAY in an email and said that Didion passed away at her home in Manhattan from Parkinson's disease.

Here, we round up seven necessary reads by the late author, who was best known for work on mourning and essays and magazine contributions that captured the American experience.

Here are the best books by Joan Didion:

'the year of magical thinking' (2005).

Probably her best known work, this gutting work of non-fiction profiles Didion's experience grieving her husband John Gregory Dunne while caring for comatose daughter Quintana Roo Dunne.

"The Year of Magical Thinking" quickly became an iconic representation of mourning, capturing the sorrow and ennui of that period. It won numerous awards, including the Pulitzer Prize and National Book Awards, and was later adapted into a play starring Vanessa Redgrave.

'Blue Nights' (2011)

A continuation of what is started in "The Year of Magical Thinking," this poignant 2011 work of non-fiction features personal and heartbreaking memories of Quintana, who passed away at the age of 39, not long after Didion's husband died.

"It is a searing inquiry into loss and a melancholy meditation on mortality and time,” wrote book critic Michiko Kakutani of the New York Times.

'Slouching Towards Bethlehem' (1968)

Didion's first collection of nonfiction writing is revered as an essential portrait of America — particularly California — in the 1960s.

It focuses on her experience growing up in the Sunshine state, icons of that time John Wayne and Howard Hughes, and the essence of Haight-Ashbury, a neighborhood in San Francisco that became the heart of the counterculture movement.

'The White Album' (1979)

A reflective collection of essays, "The White Album" explores several of the same topics Didion touched on in "Slouching Towards Bethlehem," this time focusing on the history and politics of California in the late 1960s and early '70s. Its matter-of-fact and intimate stories give the reader a feeling of what California and the atmosphere was like during that time period.

'Play it as it Lays' (1970)

Set during a time before Roe vs. Wade, this terrifying and at times disturbing novel profiles a struggling actress living in Los Angeles whose life begins to unravel after she has a back-alley abortion.

"(Didion) writes with a razor, carving her characters out of her perceptions with strokes so swift and economical that each scene ends almost before the reader is aware of it, and yet the characters go on bleeding afterward," wrote book critic John Leonard for the New York times.

'Miami' (1987)

A great example of Didion's journalistic work, "Miami" paints a portrait of life for Cuban exiles in the south Florida city.

Didion writes a stunning and passionate page-turner set against the backdrop of Miami’s decline caused by economic and political changes with the refugee immigration from Cuba after Fidel Castro’s rise to power.

Alexander Kacala is a reporter and editor at TODAY Digital and NBC OUT. He loves writing about pop culture, trending topics, LGBTQ issues, style and all things drag. His favorite celebrity profiles include Cher — who said their interview was one of the most interesting of her career — as well as Kylie Minogue, Candice Bergen, Patti Smith and RuPaul. He is based in New York City and his favorite film is “Pretty Woman.”

The White Album: Essays

About this ebook, ratings and reviews.

- Flag inappropriate

About the author

Rate this ebook, reading information, more by joan didion.

Similar ebooks

The best free cultural &

educational media on the web

- Online Courses

- Certificates

- Degrees & Mini-Degrees

- Audio Books

Read 12 Masterful Essays by Joan Didion for Free Online, Spanning Her Career From 1965 to 2013

in Literature , Writing | January 14th, 2014 3 Comments

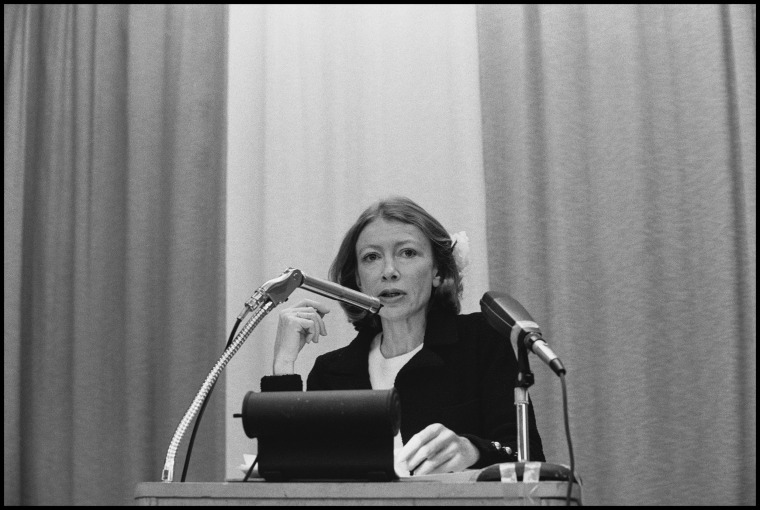

Image by David Shankbone, via Wikimedia Commons

In a classic essay of Joan Didion’s, “Goodbye to All That,” the novelist and writer breaks into her narrative—not for the first or last time—to prod her reader. She rhetorically asks and answers: “…was anyone ever so young? I am here to tell you that someone was.” The wry little moment is perfectly indicative of Didion’s unsparingly ironic critical voice. Didion is a consummate critic, from Greek kritēs , “a judge.” But she is always foremost a judge of herself. An account of Didion’s eight years in New York City, where she wrote her first novel while working for Vogue , “Goodbye to All That” frequently shifts point of view as Didion examines the truth of each statement, her prose moving seamlessly from deliberation to commentary, annotation, aside, and aphorism, like the below:

I want to explain to you, and in the process perhaps to myself, why I no longer live in New York. It is often said that New York is a city for only the very rich and the very poor. It is less often said that New York is also, at least for those of us who came there from somewhere else, a city only for the very young.

Anyone who has ever loved and left New York—or any life-altering city—will know the pangs of resignation Didion captures. These economic times and every other produce many such stories. But Didion made something entirely new of familiar sentiments. Although her essay has inspired a sub-genre , and a collection of breakup letters to New York with the same title, the unsentimental precision and compactness of Didion’s prose is all her own.

The essay appears in 1967’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem , a representative text of the literary nonfiction of the sixties alongside the work of John McPhee, Terry Southern, Tom Wolfe, and Hunter S. Thompson. In Didion’s case, the emphasis must be decidedly on the literary —her essays are as skillfully and imaginatively written as her fiction and in close conversation with their authorial forebears. “Goodbye to All That” takes its title from an earlier memoir, poet and critic Robert Graves’ 1929 account of leaving his hometown in England to fight in World War I. Didion’s appropriation of the title shows in part an ironic undercutting of the memoir as a serious piece of writing.

And yet she is perhaps best known for her work in the genre. Published almost fifty years after Slouching Towards Bethlehem , her 2005 memoir The Year of Magical Thinking is, in poet Robert Pinsky’s words , a “traveler’s faithful account” of the stunningly sudden and crushing personal calamities that claimed the lives of her husband and daughter separately. “Though the material is literally terrible,” Pinsky writes, “the writing is exhilarating and what unfolds resembles an adventure narrative: a forced expedition into those ‘cliffs of fall’ identified by Hopkins.” He refers to lines by the gifted Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins that Didion quotes in the book: “O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall / Frightful, sheer, no-man-fathomed. Hold them cheap / May who ne’er hung there.”

The nearly unimpeachably authoritative ethos of Didion’s voice convinces us that she can fearlessly traverse a wild inner landscape most of us trivialize, “hold cheap,” or cannot fathom. And yet, in a 1978 Paris Review interview , Didion—with that technical sleight of hand that is her casual mastery—called herself “a kind of apprentice plumber of fiction, a Cluny Brown at the writer’s trade.” Here she invokes a kind of archetype of literary modesty (John Locke, for example, called himself an “underlabourer” of knowledge) while also figuring herself as the winsome heroine of a 1946 Ernst Lubitsch comedy about a social climber plumber’s niece played by Jennifer Jones, a character who learns to thumb her nose at power and privilege.

A twist of fate—interviewer Linda Kuehl’s death—meant that Didion wrote her own introduction to the Paris Review interview, a very unusual occurrence that allows her to assume the role of her own interpreter, offering ironic prefatory remarks on her self-understanding. After the introduction, it’s difficult not to read the interview as a self-interrogation. Asked about her characterization of writing as a “hostile act” against readers, Didion says, “Obviously I listen to a reader, but the only reader I hear is me. I am always writing to myself. So very possibly I’m committing an aggressive and hostile act toward myself.”

It’s a curious statement. Didion’s cutting wit and fearless vulnerability take in seemingly all—the expanses of her inner world and political scandals and geopolitical intrigues of the outer, which she has dissected for the better part of half a century. Below, we have assembled a selection of Didion’s best essays online. We begin with one from Vogue :

“On Self Respect” (1961)

Didion’s 1979 essay collection The White Album brought together some of her most trenchant and searching essays about her immersion in the counterculture, and the ideological fault lines of the late sixties and seventies. The title essay begins with a gemlike sentence that became the title of a collection of her first seven volumes of nonfiction : “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” Read two essays from that collection below:

“ The Women’s Movement ” (1972)

“ Holy Water ” (1977)

Didion has maintained a vigorous presence at the New York Review of Books since the late seventies, writing primarily on politics. Below are a few of her best known pieces for them:

“ Insider Baseball ” (1988)

“ Eye on the Prize ” (1992)

“ The Teachings of Speaker Gingrich ” (1995)

“ Fixed Opinions, or the Hinge of History ” (2003)

“ Politics in the New Normal America ” (2004)

“ The Case of Theresa Schiavo ” (2005)

“ The Deferential Spirit ” (2013)

“ California Notes ” (2016)

Didion continues to write with as much style and sensitivity as she did in her first collection, her voice refined by a lifetime of experience in self-examination and piercing critical appraisal. She got her start at Vogue in the late fifties, and in 2011, she published an autobiographical essay there that returns to the theme of “yearning for a glamorous, grown up life” that she explored in “Goodbye to All That.” In “ Sable and Dark Glasses ,” Didion’s gaze is steadier, her focus this time not on the naïve young woman tempered and hardened by New York, but on herself as a child “determined to bypass childhood” and emerge as a poised, self-confident 24-year old sophisticate—the perfect New Yorker she never became.

Related Content:

Joan Didion Reads From New Memoir, Blue Nights, in Short Film Directed by Griffin Dunne

30 Free Essays & Stories by David Foster Wallace on the Web

10 Free Stories by George Saunders, Author of Tenth of December , “The Best Book You’ll Read This Year”

Read 18 Short Stories From Nobel Prize-Winning Writer Alice Munro Free Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

by Josh Jones | Permalink | Comments (3) |

Related posts:

Comments (3), 3 comments so far.

“In a classic essay of Joan Didion’s, “Goodbye to All That,” the novelist and writer breaks into her narrative—not for the first or last time,..”

Dead link to the essay

It should be “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” with the “s” on Towards.

Most of the Joan Didion Essay links have paywalls.

Add a comment

Leave a reply.

Name (required)

Email (required)

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Click here to cancel reply.

- 1,700 Free Online Courses

- 200 Online Certificate Programs

- 100+ Online Degree & Mini-Degree Programs

- 1,150 Free Movies

- 1,000 Free Audio Books

- 150+ Best Podcasts

- 800 Free eBooks

- 200 Free Textbooks

- 300 Free Language Lessons

- 150 Free Business Courses

- Free K-12 Education

- Get Our Daily Email

Free Courses

- Art & Art History

- Classics/Ancient World

- Computer Science

- Data Science

- Engineering

- Environment

- Political Science

- Writing & Journalism

- All 1500 Free Courses

- 1000+ MOOCs & Certificate Courses

Receive our Daily Email

Free updates, get our daily email.

Get the best cultural and educational resources on the web curated for you in a daily email. We never spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

FOLLOW ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Free Movies

- 1150 Free Movies Online

- Free Film Noir

- Silent Films

- Documentaries

- Martial Arts/Kung Fu

- Free Hitchcock Films

- Free Charlie Chaplin

- Free John Wayne Movies

- Free Tarkovsky Films

- Free Dziga Vertov

- Free Oscar Winners

- Free Language Lessons

- All Languages

Free eBooks

- 700 Free eBooks

- Free Philosophy eBooks

- The Harvard Classics

- Philip K. Dick Stories

- Neil Gaiman Stories

- David Foster Wallace Stories & Essays

- Hemingway Stories

- Great Gatsby & Other Fitzgerald Novels

- HP Lovecraft

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Free Alice Munro Stories

- Jennifer Egan Stories

- George Saunders Stories

- Hunter S. Thompson Essays

- Joan Didion Essays

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez Stories

- David Sedaris Stories

- Stephen King

- Golden Age Comics

- Free Books by UC Press

- Life Changing Books

Free Audio Books

- 700 Free Audio Books

- Free Audio Books: Fiction

- Free Audio Books: Poetry

- Free Audio Books: Non-Fiction

Free Textbooks

- Free Physics Textbooks

- Free Computer Science Textbooks

- Free Math Textbooks

K-12 Resources

- Free Video Lessons

- Web Resources by Subject

- Quality YouTube Channels

- Teacher Resources

- All Free Kids Resources

Free Art & Images

- All Art Images & Books

- The Rijksmuseum

- Smithsonian

- The Guggenheim

- The National Gallery

- The Whitney

- LA County Museum

- Stanford University

- British Library

- Google Art Project

- French Revolution

- Getty Images

- Guggenheim Art Books

- Met Art Books

- Getty Art Books

- New York Public Library Maps

- Museum of New Zealand

- Smarthistory

- Coloring Books

- All Bach Organ Works

- All of Bach

- 80,000 Classical Music Scores

- Free Classical Music

- Live Classical Music

- 9,000 Grateful Dead Concerts

- Alan Lomax Blues & Folk Archive

Writing Tips

- William Zinsser

- Kurt Vonnegut

- Toni Morrison

- Margaret Atwood

- David Ogilvy

- Billy Wilder

- All posts by date

Personal Finance

- Open Personal Finance

- Amazon Kindle

- Architecture

- Artificial Intelligence

- Beat & Tweets

- Comics/Cartoons

- Current Affairs

- English Language

- Entrepreneurship

- Food & Drink

- Graduation Speech

- How to Learn for Free

- Internet Archive

- Language Lessons

- Most Popular

- Neuroscience

- Photography

- Pretty Much Pop

- Productivity

- UC Berkeley

- Uncategorized

- Video - Arts & Culture

- Video - Politics/Society

- Video - Science

- Video Games

Great Lectures

- Michel Foucault

- Sun Ra at UC Berkeley

- Richard Feynman

- Joseph Campbell

- Jorge Luis Borges

- Leonard Bernstein

- Richard Dawkins

- Buckminster Fuller

- Walter Kaufmann on Existentialism

- Jacques Lacan

- Roland Barthes

- Nobel Lectures by Writers

- Bertrand Russell

- Oxford Philosophy Lectures

Receive our newsletter!

Open Culture scours the web for the best educational media. We find the free courses and audio books you need, the language lessons & educational videos you want, and plenty of enlightenment in between.

Great Recordings

- T.S. Eliot Reads Waste Land

- Sylvia Plath - Ariel

- Joyce Reads Ulysses

- Joyce - Finnegans Wake

- Patti Smith Reads Virginia Woolf

- Albert Einstein

- Charles Bukowski

- Bill Murray

- Fitzgerald Reads Shakespeare

- William Faulkner

- Flannery O'Connor

- Tolkien - The Hobbit

- Allen Ginsberg - Howl

- Dylan Thomas

- Anne Sexton

- John Cheever

- David Foster Wallace

Book Lists By

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Ernest Hemingway

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Allen Ginsberg

- Patti Smith

- Henry Miller

- Christopher Hitchens

- Joseph Brodsky

- Donald Barthelme

- David Bowie

- Samuel Beckett

- Art Garfunkel

- Marilyn Monroe

- Picks by Female Creatives

- Zadie Smith & Gary Shteyngart

- Lynda Barry

Favorite Movies

- Kurosawa's 100

- David Lynch

- Werner Herzog

- Woody Allen

- Wes Anderson

- Luis Buñuel

- Roger Ebert

- Susan Sontag

- Scorsese Foreign Films

- Philosophy Films

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

©2006-2024 Open Culture, LLC. All rights reserved.

- Advertise with Us

- Copyright Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

We earn a commission for products purchased through some links in this article.

Joan Didion: A guide to five of her most influential books

An overview of the Didion books you'll revisit for the rest of your days

Joan Didion inspired countless writers and readers to put pen to paper and write about the world as they see it. Her unique style, restrained yet honest, affecting yet never sentimental, is peerless. Famed for her incisive depictions of American life and personal journalism, she never wasted a word, nor a character. Her seminal essay for Vogue , On Self-Respect first published in 1961, was written not to a word count or a line count, but to an exact character count.

Didion's work chronicled the mood of the '60s, the highs and the lows, as well as the human experience in general - few writers have explored the subject of death and loss with as much insight, control or candour. Her skill lay not only in her style of prose, but her ability to astutely observe the behaviour of others. She saw what others missed.

Here, we celebrate five of her most influential books.

Slouching Towards Bethlehem, 1968

Although Slouching Towards Bethlehem wasn't Didion's first book ( Run, River of 1963 was), it was the one that cemented her as a prominent writer. A collection of essays about California in the '60s, her work explores the beauty and the ugliness of the decade, from the hippy community of San Francisco's Haight Ashbury to a woman accused of murdering her husband. Considered an essential portrait of American life in the '60s, Slouching Towards Bethlehem received positive attention as soon as it was published and its fandom has only grown over the decades since.

The White Album, 1979

Another collection of essays, The White Album deals with the late '60s to late '70s and the aftermath of the former. She studies the Women's Movement, shares her psychiatric report, parties with Janis Joplin and visits Linda Kasabian, who served as a lookout while members of the Manson family murdered Sharon Tate, in prison. These diverse essays see Didion capture the anxiety of the era and try to make sense of the Manson murders, the event many believe caused the '60s to end abruptly.

Where I Was From, 2003

Didion revisits the California she grew up in, specifically Sacramento County where she lived with her family, but also the state more generally. She questions the history she was taught, debunks Californian mythology and traces her ancestors and their journey moving west. She writes candidly about her upbringing, while exploring class issues with nuance. Where I Was From is one of Didion's lesser-known books, but shouldn't be.

The Year of Magical Thinking, 2005

Written in the aftermath of her husband's sudden death, The Year of Magical Thinking is an account of loss and grief - and the ways in which it can drive us to insanity. Hers was one of the first books to talk about bereavement beyond funerals, tracking the days and months that follow with her signature detachment. She writes about her own 'magical thinking' - how she can't bring herself to get rid of her husband's shoes because she thought he might need them when he returns. It sounds like pure misery, but Didion's deadpan tone impressively stops it from being so.

Blue Nights, 2011

Just a month before The Year of Magical Thinking was published, Didion's daughter, Quintana died of acute pancreatitis, aged 39. Blue Nights - a devastating account of her daughter's life and death - challenges how much tragedy one person can take. She laments over the passage of time and worries about growing older, lonelier. This is a heartbreaking tome, but solace for anyone who has ever faced the incomparable loss of losing a child.

The fashionable highlights at Milan Design Week

Sadiq Khan pledges to fight violence against women

The best female-led sustainability podcasts

Louis Vuitton teams up with artist Sun Yitian

The luxury wool bedding to buy now

How faux flowers got fashionable

Who was Clara Bow?

All the best London activity bars & restaurants

Cara Delevingne on playing Sally Bowles

What 'Baby Reindeer' teaches us about compassion

Everything we know about 'Bridgerton' season three

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Author Interviews

Remembering essayist joan didion, a keen observer of american culture.

Terry Gross

Didion, who died Dec. 23, was known her cool, unsentimental observations. Her books include Slouching Towards Bethlehem and The Year of Magical Thinking . Originally broadcast in 1987 and 2005.

DAVID BIANCULLI, HOST:

This is FRESH AIR. I'm David Bianculli, professor of television studies at Rowan University in New Jersey, in for Terry Gross. We're going to listen back to portions of two of our interviews with journalist, novelist and screenwriter Joan Didion, who died last month at the age of 87. Known for her cool, unsentimental gaze and distinctive writing, she wrote two groundbreaking collections of essays. One was called "The White Album." The other was "Slouching Towards Bethlehem," which included pieces about hippies of Haight-Ashbury and described a 5-year-old girl high on acid. She wrote 19 books in all, including the bestselling novels "Play It As It Lays" and "A Book Of Common Prayer." With her husband, novelist John Gregory Dunne, she wrote screenplays for the films "Panic In Needle Park," for the 1978 remake of "A Star Is Born," and for the film based on her novel "Play It As It Lays."

After the sudden death of her husband in 2003, Didion wrote of her grief and shock in the memoir "The Year Of Magical Thinking." It became a bestseller and was awarded the 2005 National Book Award. A year and a half later, after a period of illness, her only daughter, Quintana Roo, died at the age of 39, and Didion wrote the book "Blue Nights." Didion received the National Humanities Medal in 2012 from President Obama, who called her, quote, "one of our sharpest and most respected observers of American politics and culture," unquote. Terry Gross first spoke to Joan Didion in 1987.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

TERRY GROSS: You wrote an essay in the 1960s in which you were talking about your approach as a reporter, and you said, my only advantage as a reporter is that I am so physically small, so temperamentally unobtrusive, so neurotically inarticulate that people tend to forget that my presence runs counter to their best interests. Does that still describe you as a reporter?

JOAN DIDION: Oh, yes. I'm not a good interviewer, and I'm not very aggressive in a situation. I tend to just kind of have to hang around the edges of it and see what's going on.

GROSS: Do you think that being small and physically unobtrusive makes people more...

DIDION: Less.

GROSS: ...Less wary of you, less suspicious?

DIDION: Less wary. They think that I am not a threat to anyone.

GROSS: Do you exploit that in any way?

DIDION: No, I think - I mean, obviously I use it (laughter). I mean, since it - but I wouldn't say that I exploit it. In fact, I'm always pretty careful to - you know, as most reporters are - to go in with a notebook, to go in with a tape recorder, to go in making sure that everybody knows what you're there for.

GROSS: In another essay in your book "The White Album," you described yourself as a woman who feels radically separated from the ideas that interest other people. You wrote that you felt like a sleepwalker moving through the world, unconscious of the moment's high issues, alert only to the stuff of bad dreams, and that acquaintances would read The New York Times and try to tell you the news, but you wouldn't read the newspapers yourself. I wonder if that's changed at all, especially as you've done...

DIDION: Yeah.

GROSS: ...More reporting.

DIDION: I read the newspapers a lot, but I still - I mean, I read four or five newspapers a day, but I am still more interested in the - in what's not in the newspapers. I mean, it is kind of astonishing to me how much stuff goes on that is generally not covered.

GROSS: How would you describe what you're trying to do in comparison with daily journalism in newspapers?

DIDION: Well, what - I mean, what I do is just try to sort of go someplace and try to kind of put things together in a - just pull some threads together, rather than cover breaking events. I think it would be very hard for me to cover breaking events, and I'm not very interested in breaking events.

GROSS: Reporting brings you face to face with the world in a way that writing fiction doesn't 'cause in fiction, you encounter the world in your imagination. In journalism, you have to actually physically be there, too.

DIDION: Yeah, yeah, it's kind of a help. I mean, it's a help to me to have - to be able to go out into the world.

GROSS: Is that one of the reasons why you write journalism, to kind of...

DIDION: Yes.

GROSS: ...Get you out there?

DIDION: Yeah, it's awful to get up every morning and not - and just have to make up the world all over again. I mean, it's very - some mornings you just don't feel like it.

GROSS: You wrote in one of your essays that you had a nervous breakdown in 1968, and you even reprint some of what the doctor wrote about you. And he wrote that you had alienated yourself almost entirely from the world of human beings. I'm not sure what he meant by that. What did he mean?

DIDION: I don't know what he meant. I was astonished by it. It was - I mean, it seemed to me a very odd report. I didn't actually have a breakdown. I had a - I - well, I had a - I mean, obviously I went to a doctor, but, I mean, I wasn't hospitalized. It was - I think maybe a lot of it - of what I was - well, what he was seeing was actually - a lot of it came out of a novel I was writing at the time. I was writing "Play It As It Lays," and I think possibly that a lot of my reactions to questions asked me by a psychiatrist came out of that mood rather than my own. I mean, you are - for one thing, you are when you're writing a novel alienated from the world of other human beings.

GROSS: In the sense that you're sitting home?

DIDION: You just have these imaginary playmates who you spend the day with. And once you're deeply into it, you kind of resent it when you have to go out and go out to dinner and talk to other people when you find them an intrusion into this imaginary world. It's a peculiar hazard of writing novels.

GROSS: You wrote once that whenever you walk into a room, a sentence goes through your head. It's a sentence that Jessica Mitford's governess used to tell her, and that is, remember, you're the least important person in this room, and don't forget it.

DIDION: Exactly.

GROSS: What a really self-effacing thing to be carrying around all the time (laughter).

DIDION: It is a - it is just what I think of when I walk into a room. It's not a - it's not necessarily a bad thing.

GROSS: Well, why do you think of that?

DIDION: I think it's - I think actually that it's true. I mean, maybe all writers think that it's - or some writers think that it's so because you're focused on watching other people, rather than on their watching you.

GROSS: Were you brought up to be self-effacing...

DIDION: No, I don't...

GROSS: ...Or to think of yourself as less important than others?

DIDION: No, actually, my father was always telling me how important I was. And I - and he often has said to me that I have a deep-seated superiority complex, which may be true, but in a social situation, I tend to not be very - to be less interested in my own role in it than in everybody else, the interaction among the other people.

GROSS: You suffer from migraine headaches, which leave you incapacitated for about three to five days a month. Are they connected to writing?

DIDION: No, they're connected to not writing. They're connected to - if I could connect them to any, you know, what they're connected to is some kind of chemical flaw or vascular hereditary thing. But what actually brings them on or triggers them is always not working it, so going - doing things like losing the laundry or going to the dentist and, you know, having a lot of little confusing things that end up not doing any - end up in days that don't produce anything. I mean, the actual rhythm of working is very - is for me very, very soothing and very and makes me feel good

GROSS: Because focusing on what you're writing enables you to block out all the other chaos of life?

DIDION: Yeah. I have kind of a simple one-track mind, actually. I can't handle a whole lot of things going on on the edges. And so the simpler the day is, the better off I am.

BIANCULLI: Joan Didion speaking with Terry Gross in 1987. Joan Didion died last month at the age of 87. We'll listen back to Terry's 2005 interview with her after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

BIANCULLI: This is FRESH AIR. We're listening back to our interviews with journalist, novelist and screenwriter Joan Didion. She died last month at the age of 87. Terry spoke with her again in 2005 when her memoir, "The Year Of Magical Thinking," was published. It was about the year following the death of her husband, the writer John Gregory Dunne. He died of a heart attack as they were sitting down to dinner in 2003. Didion and Dunne had just come back from the hospital, where their daughter was in a coma, suffering from pneumonia and septic shock. After Joan Didion finished her memoir, her daughter died at age 39, about a year and a half after her husband's death. We begin this interview with Didion reading from the year of magical thinking. She and her husband were sitting down to dinner.

DIDION: We sat down. My attention was on mixing the salad. John was talking, then he wasn't. At one point in the seconds or minute before he stopped talking, he had asked me if I'd used single malt scotch for his second drink. I'd said no. I used the same scotch I had used for his first drink. Goody, he'd said, I don't know why, but I don't think you should mix them. And another point in those seconds or that minute, he had been talking about why World War I was the critical event from which the entire rest of the 20th century flowed.

I have no idea which subject we were on, the scotch or World War I, at the instant he stopped talking. I only remember looking up. His left hand was raised, and he was slumped, motionless. At first, I thought he was making a failed joke, an attempt to make the difficulty of the day seem manageable. I remember saying, don't do that. When he did not respond, my first thought was that he had started to eat and choked. I remember trying to lift him far enough from the back of a chair to give him the Heimlich.

I remember the sense of his weight as he fell forward, first against the table, then to the floor. In the kitchen by the phone, I had taped a card with the New York Presbyterian ambulance numbers. I'd not taped the numbers by the phone because I anticipated a moment like this. I'd taped the numbers by the phone in case someone in the building needed an ambulance. Someone else. I called one of the numbers. A dispatcher asked if he was breathing. I said, just come.

GROSS: That's Joan Didion reading from her new memoir, "The Year Of Magical Thinking." Joan Didion, welcome to FRESH AIR. And I just want to say at the top...

DIDION: Thank you.

GROSS: ...I'm very sorry about the loss of your husband and your daughter. This is a really beautifully written book, and I loved reading it. But I also hated reading it only in the sense that, you know, it makes me think not only of your losses, it makes me think of, you know, losses I may experience and losses - do you know? It's...

DIDION: You know, I had the sense when I was writing it that I wasn't writing it at all. It was like automatic writing, was a very different kind of process. It was simply very - everything that I - was on my mind just came out and got on the page. And that was kind of my intention to keep it kind of raw because I thought - it occurred to me when I was doing a lot of reading about death and grief that nobody told you the raw part. And every one of us is going to face it sooner or later.

GROSS: How do you think it affected your grieving to be chronicling it as it happened?

DIDION: Well, it was - it's the way I process everything is by writing it down. I don't actually process anything until I write it down, I mean, in terms of thinking, in terms of coming to terms with it. So it was kind of a necessary thing for me. I don't know that it would be for everybody.

GROSS: After you called, you know, 911, it took about five minutes for them to come. What did...

DIDION: What did I do?

GROSS: Yeah. What did you do in that five minutes?

DIDION: I kept trying to wake him up. I mean, I kept trying to lift him. I kept trying to - I don't remember. I mean, I kept - I don't remember what I did. I didn't do anything. I mean, there was nothing. I remember calling downstairs and asking the doorman to come up. But actually, the ambulance was there almost immediately.

GROSS: Your book is called "The Year Of Magical Thinking," and you realize at some point that you had been engaging in magical thinking that had to do with this genuine thought that maybe he'd come back so you shouldn't throw out his shoes in case he needs them when he comes back and...

DIDION: Right. Maybe I could - if I did the right things, he would come back. You know, it's a form of - it's the way children think. A lot of people have told me that - who have lost a husband or child that they engaged in it, too.

GROSS: Is there a point where you realized you stopped?

DIDION: There was a point where I realized that I had been doing it. And yes, then I realized - then it gradually stopped. I don't think I'm doing it now.

GROSS: You talk about how you didn't want to give away his shoes, for example, because if he came back, he'd needed them. Giving away clothes after someone dies is so hard. I mean, you have to decide with all their possessions, what are you going to keep? What are you going to give away to friends? What are you going to give to charity? What are you going to throw out? Was that a really horrible process?

DIDION: I haven't done it. I just left everything. After I discovered that I couldn't give away the shoes, I just closed that door. Now, I haven't had to move or repaint the apartment or do anything that required me to do it. I think - I presume that it would be somewhat less painful now than it was in the first few months, you know, when I initially tried it because because now I know he's dead in a way that I viscerally didn't know then. But I would just as soon let that let that door stay closed for a while until I need to open it.

GROSS: How much had you talked about death with your husband? And did you have those conversations about what to do if the other dies and what you'd want for the survivor?

DIDION: Well, he was always trying - he was always trying to have that conversation with me, and I would in many ways not have it because I thought it was - because it was - I see now it was threatening to me and I was afraid of it. But what I thought then was that it was just dwelling on things that weren't going to happen or dwelling on things that we couldn't help or, you know - and so we - I mean, I - he gave me any number of - he was always giving me - also because he was - he did have a streak of Irish morbidity, he was always talking about his funeral and giving me new lists of people who could or could not speak because he was kind of volatile in his likes and dislikes. And, of course, I had the key moment I couldn't find any of those lists. I mean, they'd been changed so often anyway that it made no - that it would have made no difference.

GROSS: I want to quote something you write in your memoir, "The Year Of Magical Thinking." You write marriage is memory. Marriage is time. Marriage is not only time. It is also paradoxically the denial of time. For 40 years, I saw myself through John's eyes. I did not age. This year, for the first time since I was 29, I saw myself through the eyes of others. This year, for the first time since I was 29, I realized that my image of myself was of someone significantly younger.

DIDION: Right.

GROSS: As writers, you both worked at home and you were with each other just about all the time. Did you have a sense of who you were outside of the marriage, who you were as a single Joan Didion, as opposed to a Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne as a unit?

DIDION: Not really, no. The family was my unit was kind of the way I - that was actually the way I wanted it. So, no, I - so it was kind of necessary to find my - you know, to refind myself. I hadn't particularly liked being single.

GROSS: When you were younger, you mean.

DIDION: When I was younger.

GROSS: Were there parts of yourself that you kind of relied on him to do? I mean - you know what I mean?

DIDION: All parts. I mean, people often said that he finished sentences for me. Well, he did, which meant that I - I mean, I just relied on him. He was between me and the world. He not only answered the telephone, he finished my sentences. He was the baffle between me and the world at large.

GROSS: So how are you negotiating the world now that there isn't that baffle?

DIDION: Well, it's like everything else. You learn to do it. I mean, I remember when I stopped smoking, it was very hard to know how to arrange me to walk around as an adult person because I had been smoking at that point since I was 15. And this is kind of like relearning all - I mean, you kind of just learn new - it's not difficult. It's just sort of lonely to - I mean, it's sort of a bleak thing to do.

GROSS: Are you comfortable being alone?

DIDION: Yeah, I've always been comfortable being alone. So that is not the problem. Basically, one thing that everybody who has been in a close marriage and who is - everyone thinks when his or her spouse dies is - it's the way in which you are struck at every moment with something you need to tell him.

GROSS: Right.

BIANCULLI: Joan Didion speaking to Terry Gross in 2005. Joan Didion died last month at age 87. After a break, we'll hear more of their conversation, and we'll also remember actress Betty White, who died last month at age 99. I'm David Bianculli, and this is FRESH AIR.

BIANCULLI: This is FRESH AIR. I'm David Bianculli in for Terry Gross. We're listening back to our interviews with Joan Didion, who died last month at the age of 87. Terry spoke with Joan Didion in 2005 after the publication of her memoir "The Year Of Magical Thinking." It was about her grieving for her husband, writer John Gregory Dunne. He had died of a heart attack at the end of 2003, just after they had visited their daughter in the hospital, where she lay in a coma, suffering from pneumonia and septic shock.

GROSS: Your husband died five days after your daughter had been hospitalized for pneumonia, and by the time he died, she had also gone into septic shock of basically...

DIDION: Right. Yeah.

GROSS: ...A blood infection. So you were dealing - you had just gotten back from the hospital visiting her when he died.

DIDION: We had been seeing her in the hospital, yet it could not be described as a visit, really, because she was unconscious.

GROSS: She was in a coma.

DIDION: But - she was in an induced coma because she was on a ventilator. And they kept her under heavy sedation so that she wouldn't tear out the ventilator, which people tend to do when they find something going down their throats.

GROSS: Your daughter got out of the hospital. She had several major setbacks. But at the end of your memoir, you think that she's on the verge of really resuming her life. In August, after you'd finished your memoir, your daughter died. And this was about a year and a half after your husband's death. She was 39.

DIDION: Right. Right.

GROSS: You had just examined your grief over your husband so thoroughly in writing about it, and then it was time to grieve again. Now, with your husband, you understood the magical thinking that you were going through, this belief - this impossible belief that somehow he was going to come back, so you shouldn't even, like, throw out his clothes because he'd need them if he came back. Having examined your grief so carefully, were there little tricks that one plays on oneself when one's grieving that you couldn't even do anymore because you'd seen through it by writing your memoir?

DIDION: Well, I didn't - you see, I haven't really started grieving yet.

GROSS: For your daughter?

DIDION: Right. I think I'm still in the shock phase. And right after John died, I had - there was a long period before I was able to grieve because I was focused entirely on getting Quintana well. And I think that was - in a way, it was very good because by the time I was able to deal with it, I was dealing with it not quite as a crazy person, which I certainly would have been at the beginning.

GROSS: You had to deal with one thing that is a very, I think, peculiar thing to have to deal with. When you're grieving for the loss of a child, you had to figure out, well, did you have to rewrite or update your book? You know, your memoir had just been sent in. Your daughter...

DIDION: It never crossed my...

GROSS: It never crossed...

DIDION: Never crossed my mind.

GROSS: ...Your mind to rewrite it?

DIDION: No.

GROSS: And why not?

DIDION: It was finished. Well, it was about a certain period of time after John died, and that period was over. I mean, if I were to do something about Quintana, which I have no thought of doing, it would be a different book. It would be a different - it would be a thing of its own. It wouldn't be about a marriage. This book is about a marriage.

GROSS: Things like deaths and other tragedies tend to test people's faith if they have it or get them to immerse themselves deeper into faith or affirm their lack of faith or have them change from one point of view to another. I don't know if you've ever had any faith and if at all the deaths of your daughter and husband affected that.

DIDION: No, the deaths of my daughter and husband did not affect it. Whether I had any faith is - I have a kind of faith, but it's not a conventional kind of faith. And as I said some place in the book, that I - basically, I believe in geology and in the Episcopal litany but as a - I believe in certain symbols, but I don't believe in them as literal truth. I believe in a poetic truth.

GROSS: Do you have any - what is death to you? I mean, when you think about death, do you think of there being some kind of afterlife or just, you know, like, a void or a soul or...

DIDION: No, I don't believe in an afterlife. Well, you know, what is death to me? Death is ashes to ashes, dust to dust. Yeah. There's a continuum, which - there's a continuum of things. But it's not - I don't believe in - I remember somebody once saying to me, the manager of a motel where I was staying - I was doing a piece in Oregon. And this motel manager had just come back from a funeral, and he said it was the most depressing thing he'd ever been to. He says, the coldest funeral I've ever been to. It was an Episcopalian funeral. Have you ever been to one? I said, yes, I have. And he said, they are so cold. And I said, how do you mean? And he said, if you can't believe you're going to heaven in your own body and on a first-name basis with everybody in your family, what's the point of dying?

And I loved this. I mean, it just - it was so far from any kind of church I knew, you know? I mean, the whole question, what's the point of dying - well, yes, what is the point? I mean, there was a kind of madness about it. I mean, that's the faith I don't have.

GROSS: Do you ever wish you did? Do you ever envy, like, that man, for instance, who has that kind of faith, that, you know, he's going to die and be reunited in heaven...

DIDION: And that - and there's a point in it?

GROSS: ...In his clothes, in his body - yeah.

DIDION: Yeah. Sure (laughter). That would be, I suppose, very comforting. But there's no possible way I could have it.

GROSS: Are you feeling overwhelmed now by the fragility of life, having lost your daughter and husband?

DIDION: Well, I certainly felt it after John died. Yes, I am a little on the wary side. When I'm with - a friend was having a sort of a minor procedure today, and I was very anxious. I found myself being far more anxious about it than I might normally have been.

GROSS: Are you any more or less worried about your own death now?

DIDION: No, I'm not worried about my own death. I think I'm less worried.

GROSS: Why?

DIDION: One of the things that worries us about dying always is we think we're - we're afraid we're leaving people behind and they won't be able to take care of themselves. We have to take care of them. But in fact, you see, I'm not leaving anybody behind. This is an area we shouldn't get into, I think.

GROSS: That's fine. That's fine. Do you want another minute before we talk more?

GROSS: Yeah.

BIANCULLI: We're listening to Terry's 2005 conversation with Joan Didion. We'll hear more after a break. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF CUONG VU AND PAT METHENY'S "SEEDS OF DOUBT")

BIANCULLI: This is FRESH AIR. Writer Joan Didion died last month at the age of 87. We're listening to Terry's 2005 interview with her after the publication of her memoir, "The Year Of Magical Thinking," about the death of her husband. When we left off, Joan Didion asked to pause the interview. Meanwhile, Terry's producer found out that the year's National Book Award nominees had just been announced.

GROSS: While you were just collecting your thoughts for a second, my producer just came in and said - and I don't know if you know this or not, but it just came across the wire that your memoir was nominated for a National Book Award.

DIDION: Really?

DIDION: Oh, well, great (laughter).

GROSS: So I guess let me be the first to congratulate you (laughter).

DIDION: Well, thank you. Thank you.

GROSS: What a weird time for you. I mean, the book, I understand, is, like, flying off the shelves. It's nominated for a national book award, and it's about the worst thing that's ever happened to you in your life.

DIDION: Yeah, it's sort of - there is a mixed feeling about it, I mean, in my mind. On the other hand, it would make John happy.

GROSS: Oh, yeah.

DIDION: I mean, I think he'd be - yeah, I think he'd be very gratified.

GROSS: I know that, among other things, your book will be read by a lot of people who have, you know, gone through their own grief. What were some of the things that you've read that you found helpful? You know, one of the things that really surprised me actually in your book is that you single out Emily Post. You went back to...

DIDION: Emily Post...

DIDION: Emily Post was fantastic on the whole subject of death and how to handle people who are grieving. I mean, she's so practical. She simply dealt with what happens to them physiologically. They're going to be cold. They're going to need - the digestion is going to stop. Everything stops. Everything in your body just stops when you're going through something like that. And so she suggested the little ways to get them back to life. Have them sit by the fire. The room should be sunny. They can be served small amounts of toast and - or something they like, but not much because they will reject it. You can sort of - if you just hand them something when they come home from the funeral, you will find that they eat it. But if you ask them, they will say, no.

Actually, I got a - now I've got a letter from her - from one of her descendants who now edits the cookbook or the etiquette book. And she pointed out that the 1922 edition, which is the edition I was reading, had been written not long after the death of Emily Post's son. And almost everybody in that period had somebody die close to them. I mean, we were dealing with the aftermath of the 1918 flu epidemic. People died of infections. I mean, death was really in every household. So it was a much more commonly acknowledged thing than it is now. I mean, now when it happens in hospitals, we tend to think of it as the province of doctors. Well, at that time, anybody - everybody knew somebody who was in mourning.

GROSS: Before we say goodbye, I'm just wondering - I felt a little uncomfortable during this interview only because I - you know, the memoir, it's such a fine book, and I think your losses are still so recent that I feel awkward talking with you about them. And I imagine it must be awkward for you to be talking about it to people you don't know like me and to our listeners. At the same time, I understand that there might be some comfort in that because one of the things you've always been as a writer is a reporter, not a reporter in the conventional sense but as a more poetic form of reporter who observes the things around you in the world and reports on that for the rest of us. Do you feel like that's what you're doing now?

DIDION: Well, I think that - I mean, I had a very definite sense of reporting when I was doing this book, and I don't mean reporting the - doing the research. There was a certain amount of research I did. I mean, I did some reading about grief. I mean, I read all the psychiatrists. But I mean a sense of reporting from a different - from a state that not everybody had yet entered. I mean, the - or that some people had but hadn't reported back so that there might be some use in reporting back, in sending a dispatch, in filing.

BIANCULLI: Joan Didion speaking to Terry Gross in 2005. The journalist, novelist and screenwriter died last month at age 87. Coming up, we remember Betty White, the popular TV actress who died last Friday at age 99. This is FRESH AIR.

(SOUNDBITE OF JIM FARMER'S "THE REAL BLONDE")

Copyright © 2022 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

American writer Joan Didion's 1979 book of essays on the history and politics of California in the late 60s and early 70s: 3 wds. - Daily Themed Crossword

Hello everyone! Thank you visiting our website, here you will be able to find all the answers for Daily Themed Crossword Game (DTC). Daily Themed Crossword is the new wonderful word game developed by PlaySimple Games, known by his best puzzle word games on the android and apple store. A fun crossword game with each day connected to a different theme. Choose from a range of topics like Movies, Sports, Technology, Games, History, Architecture and more! Access to hundreds of puzzles, right on your Android device, so play or review your crosswords when you want, wherever you want! Give your brain some exercise and solve your way through brilliant crosswords published every day! Increase your vocabulary and general knowledge. Become a master crossword solver while having tons of fun, and all for free! The answers are divided into several pages to keep it clear. This page contains answers to puzzle American writer Joan Didion's 1979 book of essays on the history and politics of California in the late 60s and early 70s: 3 wds..

American writer Joan Didion's 1979 book of essays on the history and politics of California in the late 60s and early 70s: 3 wds.

The answer to this question:

Joan Didion obituary

The writing of Joan Didion , who has died aged 87, was mantra-like, mannered, even “set in its own modulations” (that was Martin Amis’s snipe). It was also unique and remarkable. Even the shape of her books was uncommon, the sentences spaced on pages as tall and narrow as king-sized cigarette packets.

She had practised that incantatory style since her mother had presented her, aged five, with a notebook and a suggestion that she calm her anxious self by writing. Her family had long been settled in California , then chiefly an agricultural state, a location that mattered to Didion’s story, and to her story-telling.

She was born in Sacramento, the daughter of Eduene (nee Jerrett) and Frank Didion, a finance officer with the US army, poker player, and, after the second world war, a real estate dealer. Joan was an army brat on her father’s stations, and her juvenile fantasies set out in that notebook were doomy – death in the desert, suicide in the surf.

The only printed influence on her work she ever cited was Ernest Hemingway , as she had typed out his prose in order to master the keyboard and his syntax: the exact placement of words was the basis of her style as it had been of his. “Grammar is a piano I play by ear,” she claimed. Studying English literature at the University of California, Berkeley, taught her to audit meaning, dissect language and triangulate evidence, and modified her original ambition, acting, into writing as performance.

Didion won Vogue’s Prix de Paris contest in 1956, and was rewarded with a copywriter’s job, dogsbodying with proximity to glamour, in New York , rising to associate features editor over eight years at Condé Nast. She said later that she had been in love with the city’s promise, excited by meeting whoever was in town — models, millionaires, magnates — but had remained an exiled westerner not at home in New York. With a portable typewriter perched on a chair in her almost empty apartment, she wrote a novel about the Californian rivers she so missed.

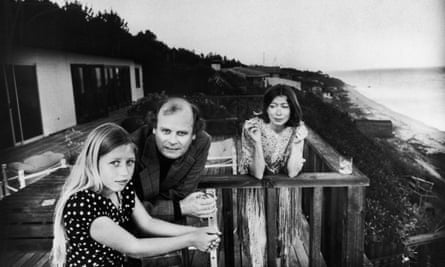

Those waterways are the real lead in her first novel, Run River (1963). John Gregory Dunne , a staffer on Time magazine and also a self-declared outsider, edited it. They married in 1964, and moved to Los Angeles temporarily, sure that his older brother, the producer Dominick Dunne , would be their entree to screenwriting. That scenario did not quite play out, and both had to turn to magazine journalism for an income.

Didion categorised some of her essays, with their first-person viewpoint and fiction-like fine detail, as “Personals”, but in fact they were about the world as seen by a social and political conservative from the last American generation to identify with adults. A tiny, unnerved and unnerving figure behind vast dark glasses, she was derisive of lax language and dismissive of unformed thought on both the left and right. She did not care to negotiate interviews with stars via their press agents.

She believed she could pass unnoticed anywhere: among the residue of the Hollywood studios and the creatives of the new music business; in arid valley towns and LA’s dustier districts; around the coagulating hippy counterculture in San Francisco. Her descriptions of her crippling social anxiety, her inability to make a phone call to get an assignment under way, did not accord with others’ memories of her taking laps of the room at swelegant parties.

Didion’s first book of collected journalism, Slouching Towards Bethlehem, published in 1968, the year in which she had a breakdown, established her reputation for cool and very slowly became a cult: as the writer Caitlin Flanagan remembered, Didion “had fans – not the way writers have fans, but the way musicians and actors have fans – and almost all of them were female”. That coolness was confirmed by her second novel, Play It As It Lays (1970), with its zomboid leading woman on Hollywood’s perimeter, so chilled a fiction that Didion’s editor, Henry Robbins, called her to ask if she was all right.

Possibly not, but she was getting by. The next year the couple had their first script onscreen, The Panic in Needle Park, and then their 1972 adaptation of Play It As It Lays flopped. Didion’s literary identity became clearer than that of her husband, with whom she shared preoccupations and phrasing, which added edge to their joint 1976 refettling of A Star Is Born to Barbra Streisand’s specifications.

Didion continued the essays, more personal yet, collected in 1979 as The White Album, and developed an idea she had had when trapped by paratyphoid in a hotel room during a Colombian film festival into A Book of Common Prayer (1977), her first fictional engagement with the role and image of the US in Central and Latin America.

At that point all the elements were in play that recurred in her fact and fiction. There was her concentration on the Americas – she had visited Europe and Israel, but disclaimed interest in them – and on the Hispanic influx into the US, which, as a Californian, she was aware of very early. Her books of reportage, El Salvador (1982) - “One morning at the breakfast table I was reading the newspaper and it just didn’t make sense,” she wrote of US press coverage of Salvador’s internal war, and immediately flew there to inspect the body dumps – and Miami (1987), were descriptions of equal and opposite cultural misunderstandings.

She felt that the US political process had become self-contained, exclusive of the electorate and, from the presidency of R onald Reagan onwards, of reality itself – as depicted in the essays anthologised in After Henry (1992) and Political Fictions (2001) and her occasional 21st century pieces. This perception also fed into her best and most successful novel, Democracy (1984), which could be read as a romance, or – as was also true of her 1996 novel The Last Thing He Wanted – as an exploration of private connections to public power. The political could not have been made more personal.