You are using an outdated browser. Upgrade your browser today or install Google Chrome Frame to better experience this site.

- IMF at a Glance

- Surveillance

- Capacity Development

- IMF Factsheets List

- IMF Members

- IMF Timeline

- Senior Officials

- Job Opportunities

- Archives of the IMF

- Climate Change

- Fiscal Policies

- Income Inequality

Flagship Publications

Other publications.

- World Economic Outlook

- Global Financial Stability Report

- Fiscal Monitor

- External Sector Report

- Staff Discussion Notes

- Working Papers

- IMF Research Perspectives

- Economic Review

- Global Housing Watch

- Commodity Prices

- Commodities Data Portal

- IMF Researchers

- Annual Research Conference

- Other IMF Events

IMF reports and publications by country

Regional offices.

- IMF Resident Representative Offices

- IMF Regional Reports

- IMF and Europe

- IMF Members' Quotas and Voting Power, and Board of Governors

- IMF Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific

- IMF Capacity Development Office in Thailand (CDOT)

- IMF Regional Office in Central America, Panama, and the Dominican Republic

- Eastern Caribbean Currency Union (ECCU)

- IMF Europe Office in Paris and Brussels

- IMF Office in the Pacific Islands

- How We Work

- IMF Training

- Digital Training Catalog

- Online Learning

- Our Partners

- Country Stories

- Technical Assistance Reports

- High-Level Summary Technical Assistance Reports

- Strategy and Policies

For Journalists

- Country Focus

- Chart of the Week

- Communiqués

- Mission Concluding Statements

- Press Releases

- Statements at Donor Meetings

- Transcripts

- Views & Commentaries

- Article IV Consultations

- Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP)

- Seminars, Conferences, & Other Events

- E-mail Notification

Press Center

The IMF Press Center is a password-protected site for working journalists.

- Login or Register

- Information of interest

- About the IMF

- Conferences

- Press briefings

- Special Features

- Middle East and Central Asia

- Economic Outlook

- Annual and spring meetings

- Most Recent

- Most Popular

- IMF Finances

- Additional Data Sources

- World Economic Outlook Databases

- Climate Change Indicators Dashboard

- IMF eLibrary-Data

- International Financial Statistics

- G20 Data Gaps Initiative

- Public Sector Debt Statistics Online Centralized Database

- Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves

- Financial Access Survey

- Government Finance Statistics

- Publications Advanced Search

- IMF eLibrary

- IMF Bookstore

- Publications Newsletter

- Essential Reading Guides

- Regional Economic Reports

- Country Reports

- Departmental Papers

- Policy Papers

- Selected Issues Papers

- All Staff Notes Series

- Analytical Notes

- Fintech Notes

- How-To Notes

- Staff Climate Notes

IMF Working Papers

Does it help information technology in banking and entrepreneurship.

Author/Editor:

Toni Ahnert ; Sebastian Doerr ; Nicola Pierri ; Yannick Timmer

Publication Date:

August 6, 2021

Electronic Access:

Free Download . Use the free Adobe Acrobat Reader to view this PDF file

Disclaimer: IMF Working Papers describe research in progress by the author(s) and are published to elicit comments and to encourage debate. The views expressed in IMF Working Papers are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.

This paper analyzes the importance of information technology (IT) in banking for entrepreneurship. To guide our empirical analysis, we build a parsimonious model of bank screening and lending that predicts that IT in banking can spur entrepreneurship by making it easier for startups to borrow against collateral. We provide empirical evidence that job creation by young firms is stronger in US counties that are more exposed to ITintensive banks. Consistent with a strengthened collateral lending channel for IT banks, entrepreneurship increases more in IT-exposed counties when house prices rise. In line with the model's implications, IT in banking increases startup activity without diminishing startup quality and it also weakens the importance of geographical distance between borrowers and lenders. These results suggest that banks' IT adoption can increase dynamism and productivity.

Working Paper No. 2021/214

Collateral Employment Financial institutions Job creation Labor Self-employment Technology

9781513591803/1018-5941

WPIEA2021214

Please address any questions about this title to [email protected]

- Previous Article

This paper analyzes the importance of information technology (IT) in banking for entrepreneurship. To guide our empirical analysis, we build a parsimonious model of bank screening and lending that predicts that IT in banking can spur entrepreneurship by making it easier for startups to borrow against collateral. We provide empirical evidence that job creation by young firms is stronger in US counties that are more exposed to ITintensive banks. Consistent with a strengthened collateral lending channel for IT banks, entrepreneurship increases more in IT-exposed counties when house prices rise. In line with the model's implications, IT in banking increases startup activity without diminishing startup quality and it also weakens the importance of geographical distance between borrowers and lenders. These results suggest that banks' IT adoption can increase dynamism and productivity.

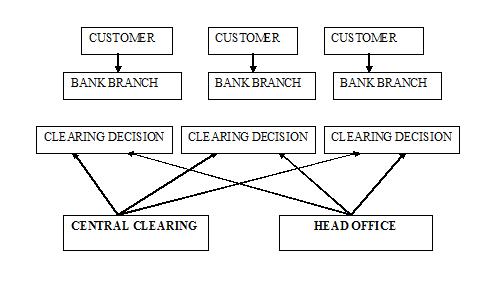

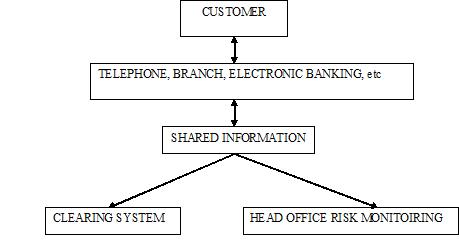

- 1 Introduction

The rise of information technology (IT) in the financial sector has dramatically changed how information is gathered, processed, and analyzed ( Liberti and Petersen, 2017 ). This development may have important implications for banks’ credit supply, as one of their key function is to screen and monitor borrowers. Financing for opaque borrowers, such as young firms that have produced limited hard information, is likely to be especially sensitive to such changes in lenders’ technology. In light of the disproportionate contribution of startups to job creation and productivity growth ( Haltiwanger, Jarmin and Miranda, 2013 ; Klenow and Li, 2020 ) and of the importance of bank credit for new firms, 1 understanding how the IT revolution in banking has affected startup access to finance is of paramount importance. Yet, direct evidence on the impact of lenders’ IT capability on firm formation is scarce.

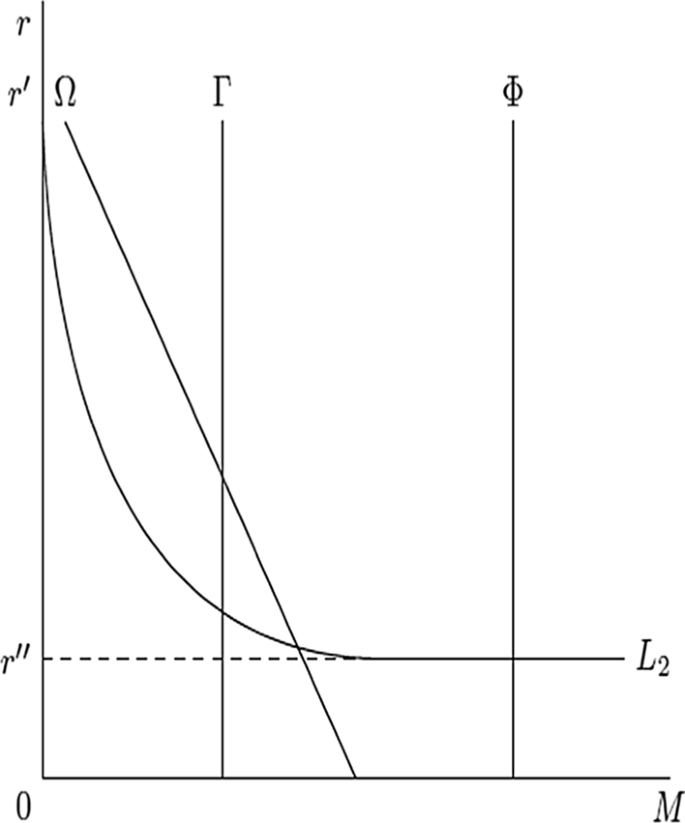

This paper analyzes how the rise of IT in the financial sector affects entrepreneurship. We first build a parsimonious model of bank screening and lending to ‘old’ and ‘young’ firms that are of heterogeneous quality and opacity. Banks can screen firms by either acquiring information about firms and their projects or by requiring collateral. Crucially, IT makes it relatively cheaper for banks to analyze hard information and in particular to use collateral in lending. Consequently, banks that have adopted IT more intensely are better equipped to lend to startups as these firms have not produced sufficient information (i.e. they are opaque ) and have to be screened through the use of collateral. The model thus predicts that IT in banking can spur entrepreneurship – and the more so when collateral value rises.

To test the model’s predictions, we use detailed data on the purchase of IT equipment of commercial banks across the United States in the years before the Great Financial Crisis (GFC). 2 Consistent with the model’s implications, we find that counties where IT-intensive banks operate experience stronger job creation by young firms, which, following previous literature, is used to measure local entrepreneurship. Moreover, the presence of IT-intensive banks strengthens the responsiveness of job creation by entrepreneurs to a rise of local real estate values. Using industry and state variation in the importance of collateral to obtain financing, we provide further evidence of a housing collateral channel for the impact of IT on entrepreneurship.

To measure IT adoption in banking, we follow seminal papers on IT adoption for non-financial firms, for example Bresnahan et al. (2002) , Brynjolfsson and Hitt (2003) , Beaudry et al. (2010) , or Bloom et al. (2012) . We use the ratio of PCs per employee within each bank as the main measure of bank-level IT adoption. This measure, while simple and based only on hardware availability, is a strong predictor of other measures of IT adoption, such as the IT budget or adoption of frontier technologies. 3 We also follow this previous literature in focusing on the overall adoption of information technology rather than specific technologies (e.g. ATMs or online banking as in Hannan and McDowell (1987) or Hernandez-Murillo et al. (2010) ) because of the multi-purpose nature of IT. Consistently, our analyses aim to shed light on the economic mechanisms behind the effects of IT adoption, rather than on the impact of specific IT applications.

We use these bank-level estimates to compute county-level exposure to banks’ IT based on banks’ historical geographic footprint. That is, a county’s exposure to banks’ IT is computed as the weighted average bank-level IT adoption of banks operating in a given county, with weights given by the historical share of local branches. Constructing local IT exposure based on banks’ historical footprint ameliorates concerns about banks’ selecting into counties based on unobservable county characteristics, such as economic dynamism or growth trajectories. Results show that county exposure is not systematically correlated with a large number of county-level characteristics, such as the unemployment rate or level of education, industry composition, or the use of IT in the non-financial sector.

We document that higher county-level IT exposure is associated with significantly higher entrepreneurial activity, measured as the employment share of new firms, following Adelino et al. (2017) . 4 Economically, our estimates imply that a one-standard-deviation higher IT exposure is associated with a 4 pp higher employment share in new firms (around 4% of the mean).

In principle, the positive relation between IT exposure and startup activity could be explained by reverse causality or omitted variable bias. Reverse causality is unlikely to be a major concern in our empirical setting: lending to startups represents only a small fraction of banks’ overall lending, which makes it unlikely that banks adopt IT solely because they expect an increase in startup activity. Yet, confounding factors could spuriously drive the association between IT and local entrepreneurship. For instance, a better-educated workforce may make it easier for banks to hire IT-savvy staff and also create more frequent business opportunities for new startups. To mitigate this concern, we start by including a wide set of county-level controls for differences in local characteristics, such as the industrial composition, education, income, and demographic structure. We document our results are unaffected by dropping the areas of the country where venture capital financing more present. We also control for IT adoption of non-financial firms, to avoid that entrepreneurship clustering in high-tech areas might drive the results. In fact, we do not find a positive correlation between IT adoption of non-financial firms and local entrepreneurship. Therefore, any confounding factors which bias our results by boosting both local entrepreneurship and IT in banking must act on banking only and not on IT adoption of other industries. This rules out many potential concerns, such as a positive correlation between entrepreneurship and local IT skills.

Additionally, when possible we include county fixed effects to control for observable and unobservable factors at the local level. Exploiting industry heterogeneity, we find that job creation by startups in counties more exposed to IT is relatively larger in industries that depend more on external financing ( Rajan and Zingales, 1998 ). This is true irrespective of whether we include county fixed effects or not – suggesting the relationship between entrepreneurship and IT is driven by better access to finance, and not unobservable county factors. Similarly, we estimate a long difference specification, in which we show that the local change in entrepreneurship over the course of our sample is positively associated with the increase in IT adoption of banks ex-ante present in the same county over the same time horizon, differencing out any potential observed and unobserved time-invariant county specific characteristics that could bias our results.

To further address the concern that exposure to IT could reflect other unobservable county characteristics, we develop an instrumental variable (IV) approach that exploits exogenous variation in banks’ market share across counties. Specifically, we instrument banks’ geographical footprint with a gravity model interacted with state-level banking deregulation, as in Doerr (2021) . That is, we first predict banks’ geographic distribution of deposits across counties with a gravity model based on the distance between banks’ headquarters and branch counties, as well as their relative market size ( Goetz et al., 2016 ). In a second step, predicted deposits are adjusted with an index of staggered interstate banking deregulation to take into account that states have restricted out-of-state banks from entering to different degrees ( Rice and Strahan, 2010 ). The cross-state and cross-time variation in branching prohibitions provides exogenous variation in the ability of banks to enter other states. Predicted deposits are thus plausibly orthogonal to unobservable county characteristics. The instrumental variable approach confirms that exposure to IT-savvy banks fosters local entrepreneurship. The estimated coefficients are not statistically different from the OLS estimates, indicating that the endogenous presence of high IT banks is not a significant concern for our empirical analysis.

Having established a robust relationship between local IT in banking and entrepreneur-ship, we investigate potential channels. Specifically, we focus on the importance of collateral, guided by our model that highlights the comparative advantage of high-IT banks to lend against collateral. While startups often do not have pre-existing internal collateral available to post against the loan, entrepreneurs often pledge their home equity as collateral. Following Mian and Sufi (2011) and Adelino et al. (2015) , we use changes in home value at the county-level to test whether higher collateral values foster startup activity, and how this relation depends on the presence of IT-intensive banks.

Consistent with the model’s predictions, we find a positive interaction between IT in banking and house price rises on entrepreneurship: the presence of IT-intensive banks spurs entrepreneurship more when collateral values rise. This interaction is strongest in industries where home equity is of high importance for startup activity measured by the industry propensity to use home equity to start and expand their business or the amount of startup capital required to start a business in an industry ( Hurst and Lusardi, 2004 ; Adelino et al., 2015 ; Doerr, 2021 ). Exploiting heterogeneity in the importance and price of collateral across regions and industries allows us to control for observed and unobserved time-variant and invariant heterogeneity at the county and industry level through granular fixed effects, further mitigating the concern that unobservable factors explain the correlation between IT in banking and entrepreneurship. Including granular fixed effects has no material effect on our estimated coefficients.

Recourse can partially substitute for the need of screening borrowers through collateral, as it may allow lenders to possess borrower assets or income, thereby diminishing the misalignment of interests between lenders and low-quality borrowers ( Ghent and Kudlyak, 2011 ). We therefore exploit that, in some states, banks are legally allowed (at least to some extent) to recourse borrowers’ income or other assets during a fore-closure, while in other states banks are prohibited from pursuing additional legal action in the event of a mortgage default (non-recourse states). Consistent with the model’s prediction, we show that the effect of IT in banking on entrepreneurship is stronger in non-recourse states due to the higher importance of collateral values. Also, the stronger elasticity of entrepreneurship to house prices in high IT counties, which we document for the whole sample, is muted in recourse states. This evidence further supports the importance of a housing collateral channel behind the stimulating role of IT in banking for entrepreneurship.

The model also predicts that IT in banking, while spurring local entrepreneurship, does not impact startup quality. The absence of a trade-off between financing more startups and lowering the quality of the marginal startup arises because more startups activity is caused by a better screening technology, while some form of screening is used for all borrowers. Empirically, we find no relation between IT exposure and job creation among young continuing firms (i.e. in the transition rates from 0 to 1 years old to 2 to 3 years old, or from 2 to 3 to 4 to 5 years old). This indicates that new firms in exposed counties are not more likely to exit in the next period. It also suggests that IT in banking can have a positive impact on business dynamism and productivity growth as the additional startups financed are of a similar quality.

In addition to county-level analyses, we use bank-county level data to shed further light on the role of the ability of IT adoption to improve the use of hard information. To this end, we focus on the importance of bank-borrower distance in lending. In fact, physical distance can increase informational frictions between borrowers and lenders, thereby increasing the importance of hard information that can be easily transmitted from local branches to the (distant) headquarters ( Petersen and Rajan, 2002 ; Liberti and Petersen, 2017 ; Vives and Ye, 2020 ). We study how distance affects bank lending in response to a local increase in business opportunities (i.e., a change in the demand for credit), measured by local growth in income per capita. We show that, first, banks’ small business lending is less sensitive to a local income shock in a county further away from banks’ headquarters – in line with the interpretation that a greater distance implies higher frictions. Consistent with the model, however, we find that banks’ IT adoption mitigates the effect of distance on the sensitivity of lending to a rise in business opportunities.

In a final step, we present additional evidence supporting the assumptions underlying the model. The model assumes that high IT banks have a relative cost advantage in lending against collateral, as they can better verify its value and transmit this information to the headquarters and also abstracts from the role of local competitions between banks. We therefore rely on loan-level data on corporate lending to show that banks with higher degree of IT adoption are more likely to request collateral for their lending, even controlling for borrower identity. This is consistent with a cost advantage of these banks with respect to other screening approaches. We finally analyze how our specifications are impacted by local market structure: we find no evidence that the relationship between IT and entrepreneurship is impacted by the local market concentration of the banking industry, indicating that the model’s simple approach to competition is appropriate for our research question (while, this interplay may be important for analyzing other issues, such as the impact on financial stability or intermediation costs ( Vives and Ye, 2020 ; De Nicolo et al., 2021 )).

The overall picture emerging from this paper is that a stronger reliance on information technology in banking decreases the consequences of informational frictions in lending markets, at least partly through making screening through the use of collateral more efficient. In turn, IT benefits opaque borrowers, such as startups, disproportionately more.

Literature and contribution. Our results relate to the literature investigating the effects of information technology in the financial sector on credit provision and small businesses. Banks’ increasing technological sophistication could enable them to more effectively screen and monitor new clients ( Hauswald and Marquez, 2003 ). On the other hand, more IT adoption could also increase banks’ reliance on hard information and growing lender-borrower distance ( Petersen and Rajan, 2002 ; Liberti and Mian, 2009 ; Liberti and Petersen, 2017 ). 5 Yet, while existing papers have often relied on proxies for banks’ use of technology or focused on specific technologies, little evidence exists on the direct impact of banks’ overall IT adoption on their lending, the role of collateral, or financing conditions of entrepreneurs.

Our work also relates to papers that analyze the importance of collateral for entrepreneurial activity ( Hurst and Lusardi, 2004 ; Adelino et al., 2015 ; Corradin and Popov, 2015 ; Schmalz et al., 2017 ). Problems of asymmetric information about the quality of new borrowers are especially acute for young firms that are costly to screen and monitor ( Degryse and Ongena, 2005 ; Agarwal and Hauswald, 2010 ). To overcome the friction, banks require hard information, often in the form of collateral, until they have better private information about borrowers ( Jimenez et al., 2006 ; Hollander and Verriest, 2016 ; Prilmeier, 2017 ; Vives and Ye, 2020 ). We contribute to the literature by providing first evidence that banks’ IT adoption increases the importance of collateral in banks’ financing of young firms. 6

Finally, we contribute to the recent literature that investigates how the rise of financial technology (FinTech) affects credit scoring and credit supply. Recent papers have focused on how FinTech has changed the way information is processed, as well as the consequences for credit allocation and performance; for instance, see Berg et al. (2019) ; Di Maggio and Yao (2018) ; Fuster et al. (2019) . However, the majority of papers examines the role of FinTech credit for consumers instead of businesses. While notable exceptions include Beaumont et al. (2199) ; Hau et al. (2018) ; Erel and Liebersohn (2020) ; Gopal and Schnabl (2020) , and Kwan et al. (2021) for the Covid-19 pandemic, the share of FinTech credit to small firms is still relatively small, compared to credit supplied by traditional providers (see Boot et al. (2021) for an overview). In this paper, we differentiate ourselves from the FinTech literature by focusing on traditional banks in the US, which are still a key provider of credit to small firms and have also invested heavily in IT. A further advantage of focusing on the banking sector is that our results are unlikely to be explained by regulatory arbitrage, which has been shown to be an important driver of the growth of FinTechs ( Buchak et al., 2018 ).

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 presents a simple model of bank screening and lending. Section 3 provides an overview over our data. Section 4 presents empirical tests for the main implications of the model. Section 5 provides additional evidence supporting the model assumptions. Section 6 concludes.

We develop a simple model to assess the implications of bank IT adoption for screening and lending. A key building block is asymmetric information, whereby firm quality is initially unobserved by banks. To mitigate the arising adverse selection problem, banks can screen by acquiring information about firms to learn their type (unsecured lending) or by requesting collateral (secured lending). We describe the effect of the IT adoption of banks on lending to young firms and derive predictions tested in the subsequent analysis.

The agents in the economy are banks and firms. There are two dates t = 0,1, no discounting, and universal risk-neutrality. There are two goods: a good for consumption or investment and collateral that can back borrowing at date 0.

Firms have a new project at date 0 that requires one unit of investment. Firms are penniless in terms of the investment good but have pledgeable collateral C at date 0. Firms are heterogeneous at date 0 along two publicly observable dimensions. First, a firm’s collateral is drawn from a continuous distribution G(C ). The market price of collateral at date 1 (in terms of consumption goods) is P. Second, firms differ in their age: firms are either old (O) or young (Y), where we refer to young firms as entrepreneurs. In total, there is mass of firms normalized to one and the share of young firms is y E (0,1). For expositional simplicity, firm age and collateral are independent.

The key friction is asymmetric information about the firm’s type, that is the quality of the project. The project yields x > 1 at date 1 if successful and 0 if unsuccessful. Good projects are more likely to be successful: the probability of success is p G for good firms and p B for bad ones, where 0 < p B < p G < 1 and only good projects have a positive NPV, p B x < 1 < p G x. Project quality (the type G or B) is privately observed by the firm but not by banks. The share of good projects at date 0 is q > 0, which is independent of bank or firm characteristics. We assume that the share of good projects is low,

so the adverse selection problem is severe enough for banks to choose to screen all bor-rowers in equilibrium. As a result, all loans granted are made to good firms.

There is a unit mass of banks endowed with one unit of the investment good at date 0 to grant a loan. An exogenous fraction h ∈ (0,1) of banks adopted IT in the past and is therefore a high-IT bank, while the remainder is a low-IT bank.

Each bank has two tools to screen borrowers. First, the bank can pay a fixed cost F to learn the type of the project (screening by information acquisition). This cost can be interpreted as the time cost of a loan officer identifying the quality of the project. We assume that this cost is lower for old firms than for young firms: 7

which captures that old firms have (i) a longer track record and thus lower uncertainty about future prospects; or (ii) larger median loan volumes, so the (fixed) time cost is relatively less relevant.

Second, the bank can screen by asking for collateral at date 0 that is repossessed and sold at date 1 if the firm defaults on the loan. In this case, the bank does not directly learn the firm’s type, but the self-selection by firms – whereby only firms with good projects choose to seek funding from banks – also reveals their type in equilibrium. We assume that the cost of screening via collateral is lower for high-IT banks than for low-IT banks: 8

which captures that it is easier or cheaper for a high-IT bank to (i) verify the existence of collateral; (ii) determine its market value; or (iii) document or convey these pieces of information to its headquarters, consistent with hard information lending. Table A3 provides evidence consistent with this assumption, showing that high-IT banks issue more secured loans in the syndicated loans market.

We assume that banks and firms are randomly matched. The lending volume maximizes joint surplus, where banks receive a fraction θ ∈ (0,1) of the surplus generated. This assumption simplifies the market structure because it implies that a startup does not make loans application with multiple banks, thus muting competitive interaction between lenders. Our approach is supported by evidence that the degree of local concentration does not impact the relationship between IT and entrepreneurship (see Table A4 ).

In what follows, we assume a ranking of screening costs relative to the expected surplus of good projects:

In equilibrium, only good firms (a fraction q of all firms) may receive credit. Moreover, young firms (a fraction y of firms) receive credit only when matched with a high-IT bank (a fraction h of banks) and when possessing enough collateral, C > C min , which applies to a fraction 1 — G(C min ) of these firms. The bound on the collateral ensures the non-participation of bad firms (i.e. firms with a bad project), making it too costly for them to pretend to be a good firm. This binding incentive compatibility constraint defines C min :

where r is the bank’s lending rate. 9 Equation 5 has an intuitive interpretation: its left-hand side is the benefit of pretending to be a good type and receiving a loan from a bank, keeping the surplus x — r whenever the project succeeds, while the right-hand side is the cost of forgoing the market value of collateral when the project fails. Since the bad firm fails fairly often (low p B ), it is fairly costly for it to pretend to be a good firm. Note that the minimum level of collateral depends on its price, C min = C min (P ). In sum, sufficient collateral, C > C min , ensures that only good firms receive loans in equilibrium.

Old firms always receive credit. When matched to a high-IT bank, lending is backed by collateral if the old firm has enough of it, otherwise the high-IT bank ensures the old firm is of good quality via information acquisition. When matched with a low-IT bank, screening via information acquisition is used. (For a relaxation, see Extension 2 below.)

Taken these results together, we can state the model’s implications about the share of expected lending to young firms s Y and how it depends on the share of high-IT firms h, the price of collateral P, and both factors simultaneously.

Proposition 1 The share of lending to young firms is s Y = y h [ 1 − G ( C min ) ] 1 − y + y h [ 1 − G ( C min ) ]

We state comparative static results in terms of the first three predictions.

Prediction 1 . A higher share of high-IT banks increases the share of lending to young firms, d s Y d h > 0 .

Prediction 2 . A higher collateral value increases the share of lending to young firms, d s Y d P > 0 (which is consistent with the evidence documented in Adelino et al. (2015) ).

Prediction 3 . A higher collateral value increases the share of lending to young firms more when the share of high-IT banks is higher, d 2 s Y d h d P > 0 .

To gain intuition for these predictions, note that a higher share of high-IT banks implies that good young firms with sufficient collateral can receive funding more often. A higher value of collateral, in turn, increases the range of young firms that have sufficient collateral, increasing expected lending on the extensive margin (lower C min ).

In equilibrium, all potential borrowers are screened and only good projects are financed, regardless of the screening choice or the bank type. Thus, the model implies that IT adoption does not affect the quality of firms who are funded by banks, as summarized in the following prediction.

Prediction 4 . Bank IT adoption does not affect the quality (default rate) of firms receiving funding in equilibrium.

We will test the model’s predictions below. Some implications are also consistent with evidence documented in other work. For instance, young firms use more collateral than old firms in equilibrium. Since firm age and size are correlated in the data, this implication is consistent with recent evidence on the greater importance of collateral for lending to small businesses ( Chodorow-Reich et al., 2021 ; Gopal, 2019 ).

Extension 1: Recourse versus non-recourse states . To tease out additional model implications, we consider the difference between recourse and non-recourse states. To do so, we assume that a fraction i ∈ (0,1) of firm owners generate an additional external income I ≥ PC min and banks may have have recourse to this income. Banks of all types (in recourse states) can obtain this income, while only high-IT banks have the comparative advantage in lending via collateral (as in the main model). In non-recourse states, no bank can lay claim to I upon the failure of the project (and loan default).

To understand the implications of recourse, note that collateral and recourse to future income are substitutes in deterring bad firms from pretending to be good ones. That is, firms with low collateral but (high) future income can obtain a loan from either bank type, while firms with high collateral and no future income can obtain a loan only from high-IT banks (as in the main model). The next prediction follows immediately.

Prediction 5 . A higher share of high-IT banks increases the share of lending to young firms by less in recourse states than in non-recourse states, d s Y d h N o n − r e c o u r s e > d s Y d h Re c o u r s e . Similarly, the impact of higher collateral value when the share of high-IT banks is higher is lower in recourse states than in non-recourse states, d 2 s Y d h d P N o n − r e c o u r s e > d 2 s Y d h d P Re c o u r s e .

Extension 2: Distance . A large literature in banking deals with the importance of distance between lenders and borrowers and the role of soft information. In our model, high-IT banks have a comparative advantage in screening based on collateral, which can be interpreted as hard information lending (and is thus unaffected by distance). Low-IT banks lend based on information acquisition. To allow for a role of distance, we assume in this extension that low-IT banks can screen some young firms, namely those that are close. Hence, we relax Assumption 4 by assuming

where the cost of information acquisition is low enough relative to the expected surplus of a good project when the firm is close to the bank.

Prediction 6 . Distance matters less for high-IT banks than low-IT banks.

In particular, the advantage of high-IT banks in hard information lending makes its lending insensitive to distance, for example in response to a shock to local economic conditions. By contrast, distance matters for the lending of low-IT banks, as they can only accommodate an additional demand for funds from young firms close to the bank.

- 3 Sample and Variable Construction

This section explains the construction of our main variables and reports summary statistics. Our main analysis focuses on the years from 1999 to 2007. While banks continued to adopt IT in more recent years, the post-crisis period saw substantial financial regulatory reform (such as the Dodd-Frank Act and regular stress tests), both of which have affected banks’ ability to lend to young and small firms. The absence of major financial regulatory changes during our sample period makes it well-suited to identify the effects of banks’ IT on entrepreneurship.

IT adoption . Data on banks’ IT adoption come from an establishment-level survey on personal computers per employee by CiTBDs Aberdeen (previously known as “Harte Hanks”) for the years 1999, 2003, 2004, and 2006. We focus on establishments in the banking sector (based on the SIC2 classification and excluding savings institutions and credit unions). We end up with 143,607 establishment-year observations.

Our main measure of bank-level IT adoption is based on the use of personal computers across establishments in the United States. To construct county-level exposure to bank IT adoption, we proceed as follows. We first hand-merge the CiTBD Aberdeen data with data on bank holding companies (BHCs) collected by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. We use the Financial Institution Reports, which provide consolidated balance sheet information and income statements for domestic BHCs. We then compute a BHC-level measure of IT adoption based on a regression of the share of personal computers on a bank (group) fixed effect controlling for the geography of the establishment and other characteristics. 10 We define this measure as I T ˜ b . The focus on BHCs rather than local branches or banks is due to the facts that (a) most of the variation in branch-level IT adoption is explained by variation at the BHC-level, (b) technology adoption at individual branches could in principle be influenced by the rate of local firm formation, (c) using a larger pool of observations reduces measurement error, and (d) this estimation procedure yields bank-level IT adoption measures that are uncorrelated with a bank’s business model (assets or funding), size, or profitability, suggesting this approach is able to purge any potential correlation between IT and management quality or other confounding factors ( Pierri and Timmer, 2020 ).

We then merge the resulting Aberdeen-BHC data set to the FDIC summary of deposits (SOD) data set that provides information on the number of branches (and deposits) of each bank in a county. To construct a measure on local exposure to IT adoption of banks, we combine I T ˜ b with the branch distribution of each bank in 1999, thus before the period of analysis. We then define the average IT adoption of all banks present in a county by:

where No.Branches b,c is the number of branches of bank b in county c in 1994 and No.Branches b,c is the total number of branches across all banks in 1994 for which we have I T ˜ b available. To ease interpretation, IT c is standardized with mean zero and standard deviation of one. Higher values indicate that banks with branches in a given county have adopted relatively more IT. 14

Our main measure of IT adoption is based on the use of personal computers across establishments in the United States, as this variable has the most comprehensive coverage during our sample period. However, for the year 2016, we also have information on the IT budget. The correlation between the IT budget of the establishment and the number of computers as a share of employees is 0.65 in 2016. The R-squared of a cross-sectional regression of PCs per Employee on the per capital IT budget is 44%. There is also a positive correlation between PCs per Employee and the probability of adoption of cloud computing. These correlations provide assurance that the number of personal computers per employee is a valid measure of IT adoption. The ratio of PCs per employee has also been used by seminal papers, for example Bresnahan et al. (2002) , Brynjolfsson and Hitt (2003) , Beaudry et al. (2010) , or Bloom et al. (2012) .

County and industry data . Data on young firms are obtained from the Quarterly Workforce Indicators (QWI). QWI provide detailed data on end-of-quarter employment at the county-two-digit NAICS industry-year level. Importantly, they provide a break-down by firm age brackets. For example, they report employment among firms of age 0–1 in manufacturing in Orange County, CA. Detailed data are available from 1999 on-ward. QWI are the only publicly available data set that provides information on county employment by firm age and industry.

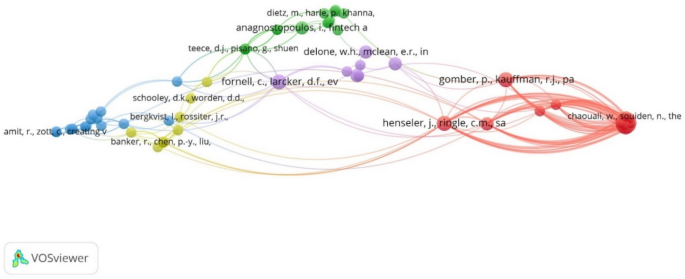

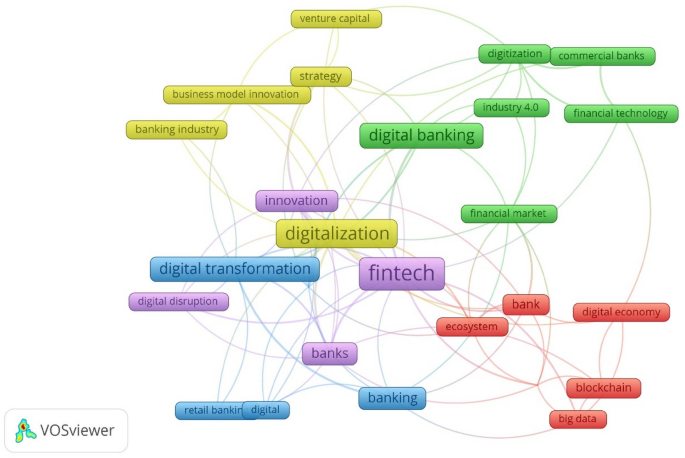

We follow the literature and define young firms or entrepreneurs as firms aged 0–1 ( Adelino et al., 2017 ; Curtis and Decker, 2018 ; Doerr, 2021 ). For each two digit industry in each county, we use 4th quarter values. Note that the employment of young firms is a flow and not a stock of employment, as it measures the number of job created by new firms in a given year. In our baseline specification, we scale the job creation of young firms by total employment in the same county-industry cell, but results are unaffected by other normalization choices. Figure 1 (panel b) plots the average creation of jobs by startup in the United States between 2000 and 2006, showing great variability both between and within states and underscoring that tech hubs, such as the Silicon Valley, are not the areas where such job creation is more prevalent. It also highlights that, while this data covers most of US surface, information is unavailable for counties in Massachusetts during the period of study.

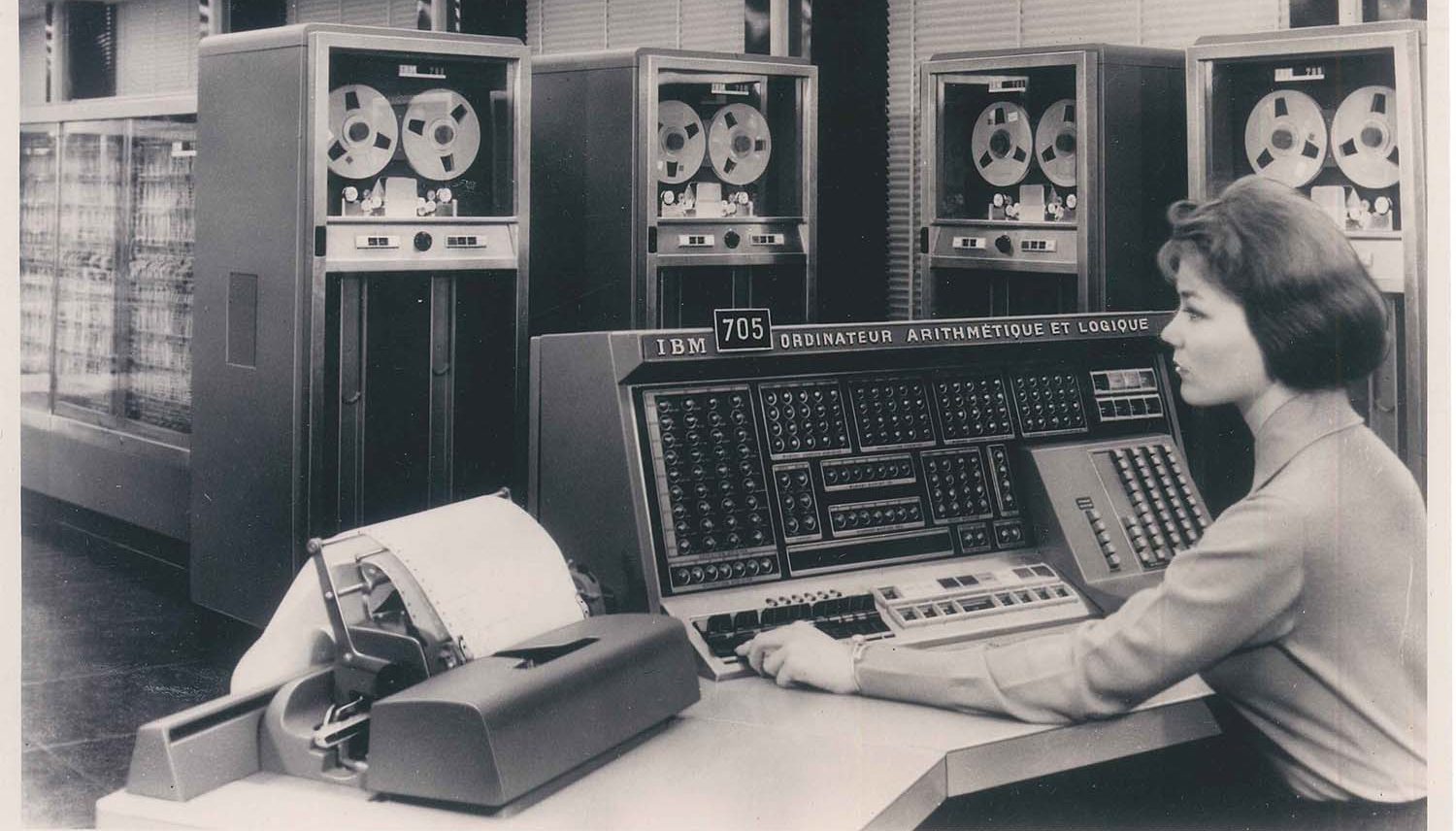

Spatial distribution of startups and IT exposure

Citation: IMF Working Papers 2021, 214; 10.5089/9781513591803.001.A001

- Download Figure

- Download figure as PowerPoint slide

The 2007 Public Use Survey of Business Owners (SBO) provides firm-level information on sources of business start-up and expansion capital, broken down by two-digit NAICS industries. For each industry i we compute the fraction of young firms that reports using home equity financing or personal assets (home equity henceforth) to start or expand their business, out of all firms ( Doerr, 2021 ). In some specifications we split industries along the median into high- and low-home equity dependent industries.

County controls include the log of the total population, the share of black population and share of population older than 65 years, the unemployment rate, house price growth, and log per capita income. The respective data sources are: Census Bureau Population Estimates, Bureau of Labor Statistics Local Area Unemployment Statistics, Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) House Price Index (HPI), and Bureau of Economic Analysis Local Area Personal Income. 12

Bank data . The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) provides detailed bank balance sheet data in its Statistics on Depository Institutions (SDI). We collect second quarter data for each year on banks’ total assets, Tier 1 capital ratio, non-interest and total income, total investment securities, overhead costs (efficiency ratio), non-performing loans, return on assets, and total deposits.

To capture the response of small business lending to changes in local house prices, we exploit Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) data on loan origination at the bank-county level, collected by the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council at the subsidiary-bank level. The CRA data contain information on loans with commitment amounts below $1 million originated by financial institutions with more than $1 billion in assets. We aggregate the data to the BHC-county level. To mitigate the effect of outliers we normalize the year-to-year change in lending volume by the mid-point of originations between the two years:

where b refers to BHC, c to county and t to year. This definition bounds growth rates to lie in [—2, 2], where —2 implies that a bank exited a county between t — 1 and t, and 2 that it entered. 13

Descriptive statistics . Table 1 reports summary statistics of our main variables at the county level; Table 2 further reports the balancedness in terms of county-level covariates, where we split the sample into counties in the bottom and top tercile of IT exposure. Except for population, we do not find significant differences across counties. Counties with high and low exposure to IT banks are similar in terms of their industry employment structure, but also in terms of the IT adoption of non-financial firms in the county. The absence of a correlation between IT exposure to banks and other county-specific variables is reassuring as it suggests that the exposure to IT in banking is also uncorrelated with other unobservable county characteristics that could bias our results. 14

Descriptive statistics

Balancedness at the county level

4 Testing the Model’s Predictions

This sections proposes a set of empirical tests for the main predictions of the model described in Section 2.

- 4.1 IT exposure and local entrepreneurship (Prediction 1)

The first prediction of the model implies a positive relation between the share of high-IT banks in a market and local entrepreneurship.

Prediction 1 . d s Y d h > 0 : a larger local presence of high-IT banks increases local lending to young firms .

To investigate this prediction, we estimate the following cross-sectional regression at the county-industry level:

The dependent variable is the employment share of firms of age 0–1 (startups) out of total employment in county (c) and 2-digit industry (i), averaged over 1999–2007. IT exposure c denotes county exposure to IT-intensive banks as of 1999, measured by the IT adoption of banks’ historical presence in the county. It is standardized to mean zero and a standard deviation of one.

To mitigate the concern that the relationship between exposure to IT in banking and local entrepreneurship is a spurious correlation driven by other local characteristics, we include a rich set of county-level controls. Controlling for county size (log of the total population) we avoid comparing small isolated counties to large urban ones. We further control for the share of population age 65 and older as younger individuals may be more likely to start companies and also have better IT knowledge. Other socio-demographic controls, such as the share of the black population, the unemployment rate, and the median household income, purge our estimates from a potential correlation between local income or investment opportunities and the variables of interests. We also control for the industrial structure of the county (proxied by employment shares in the major 2-digit industries 23, 31, 44, 62, and 72) in order to compare counties that are similar from the economic point of view, and are subject to similar shocks ( Bartik, 1991 ). We also control for the share of adults with bachelor degree or higher, as human capital may spur entrepreneurship ( Bernstein et al., 2021 ) and could also make it easier to adopt IT. Finally, we control for IT in non-financial firms (measured as the average PCs per employee in non-financial firms) to tackle the concern that startup activity may thrive in location where IT is more readily available, perhaps because many promising startups operate in the IT space or use new technology to quickly scale up. 15 All variables are measured as of 1999. Standard errors are clustered at the county level, and regressions are weighted by county size.

Abstracting from interaction terms, Prediction 1 implies that α 1 > 0. Before moving to the regression analysis, Figure 2 shows the relation between IT exposure and startup employment in a nonparametric way. It plots the share of employment among firms age 0–1 on the vertical axis against county exposure on the horizontal axis and shows a significant positive relationship, consistent with Prediction 1. We now investigate this pattern in greater detail.

Job Creation by Young Firms and Banks’ IT adoption

Table 3 shows a positive relation between county IT adoption and startup activity. Column (1) shows that counties with higher levels of IT exposure also have a significantly higher share of employment among young firms. Column (2) shows that the coefficient remains stable when we add county-level controls. Column (3) includes industry fixed effects (at the NAICS2 level) to control for unobservable confounding factors at the industry level. Including these fixed effects does not change the coefficient of interest in a statistically or economically meaningful way, despite a sizeable increase in the R-squared by 40 pp. This pattern suggests that local IT exposure is orthogonal to industry-specific characteristics ( Oster, 2019 ). The magnitude of the impact is sizeable: In column (3), a one standard deviation higher IT exposure is associated with a 0.38 pp increase in the share of young firm employment (4% of the mean of 9.3%).

County IT exposure and entrepreneurship

IT in Banking and Startup Rate – Differences

Job Creation by Young Firms, Banks’ IT adoption, House Prices, and Home Equity

In the model, banks’ IT spurs entrepreneurship through a lending channel, so we expect the positive correlation shown in columns (1)-(3) to be stronger in industries that depend more on external finance. We therefore augment the regression with an interaction term between IT adoption and industry-level dependence on external finance (which, as in Rajan and Zingales (1998) , is measured by capital expenditure minus cash flow over capital expenditure). This is, in Equation (10), we expect β 3 > 0. In column (4), the coefficient on the interaction term between IT adoption and external financial dependence is positive, and economically and statistically significant. Counties with higher IT exposure have a higher share of employment among young firms precisely in those industries that depend more on external finance, consistent with the notion that the correlation is driven by the impact of banks’ IT on startups’ financing. In terms of magnitude, a one standard deviation higher IT exposure is associated with a 1 pp increase in the share of young firm employment in industries that depend on external finance (11% of the mean).

So far, the regressions included industry fixed effects to purge the estimation from observable and unobservable confounding factors at the industry level. In column (5), we further enrich our specification with county fixed effects to control for confounding factors at the local level, for example changes in consumption of government expenditure. Results are remarkably similar to column (4): the inclusion of county fixed effects changes the estimated impact of IT exposure interacted with financial dependence by only 0.02 pp – despite the fact that the R-squared increases by 12 pp. Results from columns (2)-(3) and (4)-(5) suggest that IT exposure is uncorrelated with observable and unobservable county and industry characteristics, reducing potential concerns about self-selection and omitted variable bias ( Altonji et al., 2005 ; Oster, 2019 ).

Taken together, Figure 2 and Table 3 provide support for Prediction 1: a larger local presence of IT-intensive banks is associated with more startup activity, and especially so in sectors that depend more on external financing.

Robustness . A set of robustness tests is presented in Table A1 . Column (1) is the baseline (as column (3) of Table 3 ). In column (2) the IT exposure measure is the unweighted average of the IT adoption of banks that operate in a county, rather weighted by banks’ number of branches in that county. Column (3) uses an alternative exposure measure that use the share of local deposits from FDIC, rather than the number of branches, as a weighting variable. The results of these empirical exercises are in line with baseline and thus highlight that our findings are not driven by any specific choice of the construction of the IT adoption measure. Column (4) excludes employment in startups in the financial and education industries, showing financial companies or universities are not driving our results. Column (5) excludes Wyoming which, perhaps surprisingly, the state with the highest exposure to banks’ IT adoption (see Figure 1 , panel b). Column (6) includes state fixed effects, showing that our results are driven by within-state variation, rather than variation between different part of the county. Column (7) shows robustness of the specification by normalizing the share of employment in startups by previous year’s total employment. Column (8) reveals that our results are due to an impact on the numerator (employment of startups) rather than denominator (total employment).

Our model underscores the role of IT as a technology to facilitate the use of entrepreneurs’ real estate as collateral. However, local economic conditions could also be correlated with collateral values and this may create a correlation between local demand and use of collateral. This concern should be mitigated by the fact that we directly control for local income. Additionally, we test whether our main findings is present in industries which are less impacted by local economic conditions, that is “tradable” industries. We rely on the tradable classification of 4 digit industries by Mian and Sufi (2014) , which we aggregate at out 2 digit level: two of the 2 digit industries, that is manufacturing and mining and extraction, have most of their employment in tradable sub-industries. As illustrated by column (9) the relationship between IT and entrepreneurship is much stronger within these industries than in baseline, suggesting it is not driven by local demand. As these industries have also high dependence on external finance, this finding further suggest our main result is driven by access to finance rather than local demand.

We then consider the concern that other forms of external financing, venture capital (VC) in particular, may be correlated with IT in banking and have an impact on our results. We exploit the fact that VC funding is highly concentrated in a small fraction of the US territory. 16 We thus repeat our regressions excluding the top 20 counties (representing almost 80% of VC funding at the time) or 7 states with more VC presence, and find results similar to baseline, see columns (10) and (11).

We finally investigate the potential role of data coverage in the analysis. In fact, the IT variable is constructed from survey rather than administrative data. The high quality of the survey collected by Harte-Hanks/Aberdeen over a few decades is disciplined by market forces as the information are sold to IT supplier to direct their marketing efforts. However, it is still possible that the survey effort or success might be heterogeneous across different locations. We therefore compute a measure of local coverage, which is equal to the ratio between the establishments belonging to the banking industry surveyed by the marketing company in a county in a year and the total number of branches present according to FDIC data. We then average these across the four years (1999, 2003, 2004, 2006) to have a measure of average coverage for each county. The average value is 13.6%, with a standard deviation of 8.4%. To test how heterogeneity in local coverage might impact our results we drop the counties in the bottom quartile of coverage or, also include coverage as a control. Results are robust as reported by the last two columns.

Instrumental variable approach . The inclusion of detailed controls and the across-industries heterogeneity approach ( Rajan and Zingales, 1998 ) help mitigate the concern that local factors might impact both the presence of high IT banks and entrepreneurship. Yet, IT exposure could still be correlated with such local unobservable factors, preventing us from drawing causal implications. To this end, we follow Doerr (2021) and adopt an instrumental variable approach. In a first step, we predict banks’ geographic distribution of deposits across counties with a gravity model based on the distance between banks’ headquarters and branch counties, as well as their relative market size ( Goetz et al., 2016 ). In a second step, predicted deposits are adjusted with an index of staggered interstate banking deregulation to take into account that states have restricted out-of-state banks from entering to different degrees ( Rice and Strahan, 2010 ). The cross-state and cross-time variation in branching prohibitions provides exogenous variation in the ability of banks to enter other states. Predicted deposits are thus plausibly orthogonal to unobservable county characteristics during our sample period. We thus compute a >predicted county-level measure of exposure to IT in banking as:

We estimate a two-stage least square model considering ITc as an endogenous regressor and I T ^ c as an excluded instrument. Using I T ^ c as an instrument allows us to purge our specification from the bias introduced by unobservable factors that might attract high-IT banks and also impact local startup activity. Results are presented in Table 4 . Column (1) presents the baseline estimate on this sample of counties. Column (2) is the first stage and shows a positive correlation between exposure to IT and predicted exposure to IT. Column (3) is the reduce-form regression of the instrument on the variable of interest, showing a positive impact of predicted exposure to IT in banking on entrepreneurship. Finally, column (4) is the second stage regression: the IV estimate of the impact of IT in banking on entrepreneurship is qualitatively similar than baseline and larger in magnitude. However, we cannot reject the null hypothesis that the difference between OLS and IV estimates is zero, suggesting biases coming from unobservable factors at the local level are not significantly biasing the baseline estimates.

County IT exposure and entrepreneurship: IV approach

Increase in IT adoption over time . The period of study also is a time of robust technology adoption in the banking sector. Thus, another approach to test Prediction 1 is to analyze the relationship between increase in IT adoption and change in entrepreneurship at the county-level. To do so we compute the county exposure as

where Δ I T ˜ c is the increase of IT adoption between 1999 and 2006 of bank b.

We find that counties more exposed to the increase in IT in banking also experienced less negative decreases in startup rates, as illustrated by Figure 3 . The positive correlation between changes in IT adoption in banking and changes in startup rates is also confirmed by more formal regression analysis presented in Table A2 . These results further confirm Prediction 1 . Moreover, this first-difference approach implicitly controls any county-level (time invariant) observable and unobservable characteristics by differencing them out.

- 4.2 IT, house prices, and entrepreneurship (Predictions 2 & 3)

A large literature highlights the importance of the collateral channel for employment among small and young firms: rising real estate prices increase collateral values, thereby mitigating informational frictions and relaxing borrowing constraints ( Rampini and Viswanathan, 2010 ; Adelino et al., 2015 ; Schmalz et al., 2017 ; Bahaj et al., 2020 ). The role of collateral in our model is directly related to this literature. Predictions 2 & 3 of the model predict the following relationships between entrepreneurship, collateral values, and IT adoption:

Prediction 2 . d s Y d P > 0 : a higher collateral value increases the share of lending to young firms .

Prediction 3 . d 2 s Y d h d P > 0 : a higher collateral value increases the share of lending to young firms more when the share of high-IT banks is higher .

The predictions are tested in this section by examining how local IT adoption affects the sensitivity of entrepreneurship to house prices using a panel of county-year observations. To complement this analysis, Appendix A1 presents evidence at the bank-county-year level that high IT banks’ small business lending reacts more to an increase in local house prices.

We estimate the following regression at the county-industry-year level from 1999 to 2007:

The dependent variable is the employment share of firms of age 0–1 out of total employment in county (c) and 2-digit industry (i) in given year (t). IT exposure c denotes counties’ IT exposure as of 1999, standardized to mean zero and a standard deviation of one. ΔHPI c t is the yearly county-level growth in house prices. Controls (included when county fixed effects are not) are county size (log total population), the share of population age 65 and older, the share of black population, education, the unemployment rate, the industrial structure (measured by employment shares in the major 2-digit industries 23, 31, 44, 62, and 72), and IT adoption in non-financial firms (PCs per employee in non-financial firms), all of which lagged by one period. Standard errors are clustered at the county level.

Prediction 1 implies that γ 2 > 0. Table 5 reports the estimation results. To start, column (1) shows that higher IT exposure is associated with a higher share of young firm employment in the cross-section – in line with Table 3 . We then explicitly test Prediction 2 . Column (2) shows that a rise in house prices is associated with an increase in entrepreneurship at the local level, conditional on year fixed effects that absorb common trends. Column (3) confirms this finding when controlling for IT adoption at the county level. These findings provide support for Prediction 2 .

County IT exposure, entrepreneurship, and collateral

We then test Prediction 3 by augmenting the equation with an interaction term between changes in local house prices and county exposure to IT in banking. That is, we focus on the coefficient γ 3 in Equation 13. Based on Prediction 3, we expect γ 3 > 0. To isolate the variation of interest and controlling for any confounding factor at the local or industry level, we include county-industry fixed effects and exploit only the variation within each county-industry cell – the coefficient on IT exposure is now absorbed. As reported in column (4) of Table 5 , we find γ 3 > 0, consistent with Prediction 3 . Columns (5) and (6) add time-varying county controls, as well as industryxyear fixed effects that account for unobservable changes at the industry level. The interaction coefficient remains positive and similar in size across specifications.

Previous literature has highlighted that young firms are more responsive to changes in collateral values in industries in which average start-up capital is lower, or in industries in which a larger share of firms relies on home equity to start or expand their business ( Adelino et al., 2015 ; Doerr, 2021 ). Therefore, we exploit industry heterogeneity to provide further evidence on Prediction 3 . Focusing on differences between industries within the same county and year allows us to control for industryx year and countyx year fixed effects and thus purge our estimates from the impact of any time-varying industry or local shock. Results, presented in columns (6) and (7), reveal that the larger benefits of house prices increase due to the presence of high IT banks occur exactly in those industries whose financing should be more sensitive to changes in collateral values.

In sum, Table 5 provides evidence in line with Predictions 1 and 2: entrepreneurship increases when local collateral values increase, and do so in particular in counties with higher exposure to IT-intensive banks.

- 4.3 IT exposure and startup quality (Prediction 4)

The model predicts that a stronger presence of high IT banks increases the share of startups receiving funding without impacting its average quality. As IT helps with screening, there is no trade off between quantity of credit and marginal quality of the borrower.

Prediction 4 . Bank IT adoption does not affect the quality (default rate) of firms receiving funding in equilibrium .

In the model firm quality is disciplined by the probability of default. In the data, we use the average growth rate of employment of startups during the first few years of life, which can be proxied by the “transition rates” ( Adelino et al., 2017 ). As the QWI report the employment of firms that are 2–3 years old in a given year, we can substract the employment of startups (firms age 0 or 1 year) two years before to obtain the change in the job created by the continuing startups in that period, which equals the (weighted) average growth rate of employment among those firms. Thus, the transition rate in a county-industry cell is defined as:

We construct similar transition rates for firms transitioning from 2–3 years to 4–5 years. We then estimate a cross-sectional regression similar to Equation 10 where the dependent variable is the average of transition c,s,t between 2000 and 2006. As illustrated in columns (1)-(3) of Table 6 , there is no correlation between a county’s exposure to IT in banking and the growth rate of local startups, neither on average nor in industries that are more dependent on external finance. We find similar effects for the transition rates from 2–3 years to 4–5 years in columns (4)-(6).

County IT exposure and transition rates

The lack of a significant relationship between IT exposure and local startup quality matters, as it suggests our findings have aggregate implications. In fact, if the additional startups created thanks to IT are not of lower quality than other startups, they should be able to bring benefits to the economy, for example in terms of business dynamism and long-run employment creation and productivity growth.

- 4.4 IT and the role of recourse default (Prediction 5)

Collateral and other screening mechanisms can be partially substitute by deficiency judgment if the lender is able to possess other borrower’s assets or future income through a deficiency judgment. This makes it less appealing for potential entrepreneurs with a low quality project to pretend to be of good type and get funds, diminishing the extent of asymmetric information between lenders and borrowers. As IT spurs entrepreneurship by allowing for better screening, the model predicts that IT is less important when recourse default is possible ( Prediction 5 ). Similarly, the stronger elasticity of entrepreneurship to house prices in counties more exposed to IT in banking ( Prediction 3 ) is predicted to be more muted.

There is a significant heterogeneity across US states in terms of legal and practical considerations which makes obtaining a deficiency judgment more or less difficult for the lender. Ghent and Kudlyak (2011) relies on recourse / non-recourse classifications of states from the 21 st edition (2004) of the National Mortgage Servicer’s Reference Directory to show that recourse clauses impact borrowers’ behavior. We rely on the same classification and estimate the cross-sectional relationship between IT and entrepreneur-ship (i.e. Equation 10) for counties in recourse versus non-recourse states. Comparison between columns (1) and (2) of Table 7 highlights that the relationship is stronger within non-recourse states, as predicted by the model. Moreover, we can test for whether this difference is statistically significant by adding state fixed effects and the interaction term between exposure to IT and state recourse classification to Equation 10. Columns (3) shows that in recourse states the relationship between IT adoption and entrepreneurship is significantly weaker. Column (4) confirms the finding excluding North Carolina, as its classification presents some ambiguity. Moreover, while in the whole sample entrepreneurship responds more to house prices in counties more exposed to IT in banking, this is less the case in recourse states, see the last column of Table 5 .

- 4.5 IT and the role of distance (Prediction 6)

In the model, banks verify the value of collateral at cost v. We assume that v is lower for high-IT banks because they can better verify the existence and market value of collateral, but also because they it is cheaper for high-IT to transmit such information about borrowers’ collateral to (distant) headquarters of high-IT banks. Following a large literature that shows that informational frictions increase with lender-borrower distance ( Liberti and Petersen, 2017 ), we now investigate the importance of distance in banks’ lending decisions. The literature suggests that IT adoption by banks could reduce the importance of distance ( Petersen and Rajan, 2002 ; Vives and Ye, 2020 ), as it enables a more effective transmission of hard information. Consequently, the informational frictions associated with distance become less important. To test whether the relationship between local investment opportunities and lender-borrower distance is different for banks’ with more or less IT use, we consider the following model that relates banks’ loan growth to local investment opportunities (measured as the change in local income, proxying an increase in local demand for credit):

The dependent variable is the log difference in total CRA small business loans by bank b to borrower county c in year t along the intensive margin. 17 log(distance) measures the distance between banks’ HQ and the county of the borrower. In general, we expect that an increase in local investment opportunities, measured by the log difference of county-level income per capita, increases local lending; and the more so, the smaller the log distance between the lender and the borrower. That is, we expect β 1 > 0 and β 3 ̼ 0. As banks’ IT adoption reduces the importance of distance, the model predicts β 3 to be significantly smaller for high IT banks.

Results in Table 8 support these hypotheses. Column (1) shows that rising local incomes are indeed associated with higher local loan growth; and that distance reduces the sensitivity of banks’ CRA lending in response to local investment opportunities as the interaction terms between changes in income and distance is negative. This findings holds when we include county x year fixed effects to control for any local shock in column (2). Columns (3) and (4) show that the lower responsiveness of banks’ lending to income shocks in counties located further away is present only for low IT banks; for high IT banks, distance has no dampening effect. Interaction specifications in columns (5) and (6) confirm this finding: while distance reduces the sensitivity of lending to changes in local investment opportunities for low IT banks, among high IT banks distance matters significantly less in the decision to grant a loan in response to local shocks to investment opportunities. Results are similar when we enrich the specification with bank fixed effects.

CRA lending — distance all loans

- 5 Competition and Collateralized Lending

In this section we present additional evidence that speaks to assumptions and implications of the model. We provide evidence that high-IT banks are more likely to provide col-lateralized loans even when controlling for unobservable borrower characteristics through fixed effects, supporting the assumption that IT provides an advantage in collateralized lending. We also show that the effects of IT on startup activity and lending do not depend on local competition among banks.

IT and the use of collateral . Our model builds on the assumption that high IT banks have a relative cost advantage in screening through collateral with respect to information acquisition. We investigate the soundness of this assumption by looking at whether banks which adopt more IT are also more likely to use collateral in their lending, controlling for borrower characteristics. While we do not have loan-level information on lending to startups, as a second best we can perform such empirical test on large corporate loans data from DealScan as in Ivashina and Scharfstein (2010) , for example.

Consistent with the model’s assumption, Figure A2 shows that the share of loans that are collateralized is positively correlated with bank IT adoption. To test whether this correlation is really driven by banks’ IT rather than borrowers heterogeneity, we estimate the following linear probability model:

where b is a bank that granted a loan in year t to (large) corporate borrower i and secured b,i,t is a dummy equal to one whenever the loan is collateralized. Results are presented in Table A3 and confirm that more IT intense banks are more likely to lend through a secured loan than other banks, even when controlling for borrower fixed effects.

The role of local competition . The model assumes that local bank competition is independent of bank IT adoption. In fact, bank and potential borrowers are assumed to be matched and to share the surplus from lending – if a loan is granted. To understand how this simplified market structure might impact our results, we reestimate the main equation of interest, Equation 10, and augment it with a term for bank concentration (in terms of deposits or CRA lending) in a county, and the interaction between local IT exposure and concentration. Results are presented in Table A4 . Higher concentration is associated with more startup activities. This might be due to the fact that banks might be more prone to lend to startups when competition is low if they know they can gain larger information rent and extract more surplus as these firms grow ( Petersen and Rajan, 1995 ). However, we find no significant interaction between concentration and local IT adoption in banking. The positive impact of IT on startups does not seem to depend on the local market structure. This result mitigates the concern that the simplistic approach to market power in the model is severely harming its ability to describe the relationship between IT adoption and entrepreneurship, which is the aim of this paper.

- 6 Conclusion

Over the last decades, banks have invested in information technology at a grand scale. However, there is very little evidence on the effects of this ‘IT revolution’ in banking on lending and the real economy. In this paper we focus on startups because of their importance for business dynamics and productivity growth, and because they are opaque borrowers and thus may be sensitive to technologies that change information frictions.

We show that IT adoption in the financial sector has spurred entrepreneurship. In regions where banks that with more IT-adoption have a larger footprint, job creation by startups was relatively stronger; this relationship is particularly pronounced in industries that rely more on external finance. We show – both theoretically and empirically – that collateral plays an important role in explaining these patterns. As IT makes it easier for banks to assess the value and quality of collateral, banks with higher IT adoption are more likely to lend against increases in entrepreneurs’ collateral.

Our results have important implications for policy. Banks’ enthusiasm towards technology adoption has been very strong during the last years, 18 and the role of FinTech companies as lenders of small businesses has been increasing since the GFC ( Gopal and Schnabl, 2020 ). This has triggered a debate on the impact of IT in finance on the economy, for example through its impact on the need for collateral and firms’ access to credit ( Gambacorta et al., 2020 ). Our findings suggest that IT in lending decisions can spur job creation by young firms by making lending against collateral cheaper. From a policy perspective, this finding raises the hope that improvements in financial technology help young and dynamic firms to get financing.

Given the strong rise in house prices since the pandemic and larger reliance on IT systems due to a reduction in physical interactions, our evidence also suggests that the adoption of IT in banking can spur entrepreneurship and productivity growth in the post-pandemic world.

Adelino , Manuel , Song Ma , and David Robinson ( 2017 ) “ Firm age, investment opportunities, and job creation ”, The Journal of Finance , 72 ( 3 ), pp. 999 – 1038 .

- Search Google Scholar

- Export Citation

Adelino , Manuel , Antoinette Schoar , and Felipe Severino ( 2015 ) “ House prices, collateral, and self-employment ”, Journal of Financial Economics , 117 ( 2 ), pp. 288 – 306 .

Agarwal , Sumit and Robert Hauswald ( 2010 ) “ Distance and private information in lending ”, Review of Financial Studies , 23 ( 7 ), pp. 2758 – 2788 .

Altonji , Joseph G. , Todd E. Elder , and Christopher R. Taber ( 2005 ) “ Selection on observed and unobserved variables: Assessing the effectiveness of catholic schools ”, Journal of Political Economy , 113 ( 1 ), pp. 151 – 184 .

Bahaj , Saleem , Angus Foulis , and Gabor Pinter ( 2020 ) “ Home values and firm behaviour ”, American Economic Review , 110 ( 7 ), pp. 2225 – 2270 .

Bartik , Timothy J ( 1991 ) “ Who benefits from state and local economic development policies? ”.

Beaudry , Paul , Mark Doms , and Ethan Lewis ( 2010 ) “ Should the personal computer be considered a technological revolution? evidence from us metropolitan areas ”, Journal ofPolitical Economy , 118 ( 5 ), pp. 988 – 1036 .

Beaumont , Paul , Huan Tang , and Eric Vansteenberghe , “ The role of fintech in small business lending: Evidence from france ”.

Berg , Tobias , Valentin Burg , Ana Gombovic , and Manju Puri ( 2019 ) “ On the rise of fintechs-credit scoring using digital footprints ”, The Review of Financial Studies .

Berger , Allen N. and Gregory F. Udell ( 2002 ) “ Small Business Credit Availabil-ity and Relationship Lending: The Importance of Bank Organisational Structure ”, Economic Journal , 112 ( 477 ), pp. 31 – 53 .

Bernstein , Shai , Emanuele Colonnelli , Davide Malacrino , and Tim McQuade ( 2021 ) “ Who creates new firms when local opportunities arise? ”, Journal of Financial Economics .

Bloom , Nicholas , Raffaella Sadun , and John Van Reenen ( 2012 ) “ Americans do it better: Us multinationals and the productivity miracle ”, American Economic Review , 102 ( 1 ), pp. 167 – 201 .

Boot , Arnoud , Peter Hoffmann , Luc Laeven , and Lev Ratnovski ( 2021 ) “ Fin-tech: what’s old, what’s new? ”, Journal of Financial Stability , 53, p. 100836.

Boot , Arnoud W. A. ( 2016 ) “ Understanding the Future of Banking Scale & Scope Economies, and Fintech ”, Asli Demirguc-Kunt , Douglas D. Evanoff , and George G. Kaufman eds. The Future of Large, Internationally Active Banks , World Scientific , Chap. 25, pp. 429 – 448 .

Bresnahan , Timothy F , Erik Brynjolfsson , and Lorin M Hitt ( 2002 ) “ Informa-tion technology, workplace organization, and the demand for skilled labor: Firm-level evidence ”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics , 117 ( 1 ), pp. 339 – 376 .

Brynjolfsson , Erik and Lorin M Hitt ( 2003 ) “ Computing productivity: Firm-level evidence ”, Review ofEconomics and Statistics , 85 ( 4 ), pp. 793 – 808 .

Buchak , Greg , Gregor Matvos , Tomasz Piskorski , and Amit Seru ( 2018 ) “ Fin-tech, regulatory arbitrage, and the rise of shadow banks ”, Journal of Financial Eco-nomics , 130 ( 3 ), pp. 453 – 483 .

Chodorow-Reich , Gabriel , Olivier Darmouni , Stephan Luck , and Matthew Plosser ( 2021 ) “ Bank liquidity provision across the firm size distribution ”.

Corradin , Stefano and Alexander Popov ( 2015 ) “ House prices, home equity borrow-ing, and entrepreneurship ”, The Review ofFinancial Studies , 28 ( 8 ), pp. 2399 – 2428 .

Curtis , E Mark and Ryan Decker ( 2018 ) “ Entrepreneurship and state taxation ”.

Davis , Steven J. and John C. Haltiwanger ( 1999 ) “ Gross job flows ”, Handbook of Labor Economics , 3 ( B ), pp. 2711 – 2805 .

De Nicolo , Gianni , Andrea Presbitero , Alessandro Rebucci , and Gang Zhang ( 2021 ) “ Technology adoption, market structure, and the cost of bank intermediation ”, Market Structure, and the Cost of Bank Intermediation (March 23, 2021) .

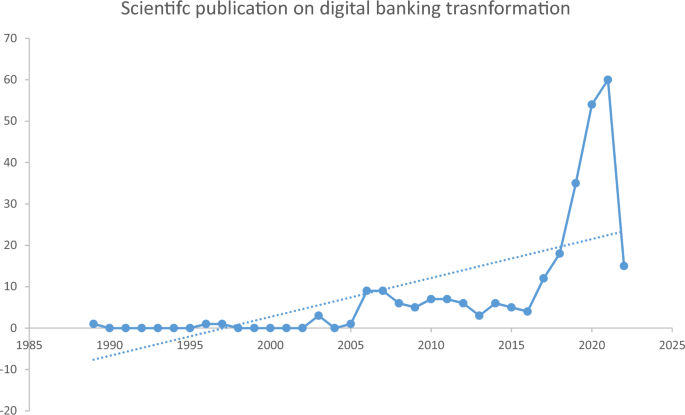

Decker , Ryan A , John Haltiwanger , Ron S Jarmin , and Javier Miranda ( 2016 ) “ Declining business dynamism: Implications for productivity ”, Brookings Institution, Hutchins Center Working Paper .